Shina language

| Shina | |

|---|---|

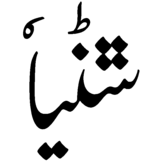

| ݜݨیاٗ زبان / ݜݨیاٗ گلیتوࣿ زبان Ṣiṇyaá | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [ʂiɳjá] |

| Native to | Pakistan, India |

| Region | Gilgit-Baltistan, Kohistan, Drass, Gurez |

| Ethnicity | Shina |

Native speakers | 720,200 Shina (2018)[1] and Shina, Kohistani 458,000 (2018)[2] |

| Arabic script (Nastaʿlīq)[3] | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:scl – Standard Shinaplk – Kohistani Shina |

| Glottolog | shin1264 Shinakohi1248 Kohistani Shina |

Distribution of Shina language in Dark Orange | |

Shina (ݜݨیاٗ,شِْنْیٛا Ṣiṇyaá, IPA: [ʂiɳjá]) is a Dardic language of Indo-Aryan language family spoken by the Shina people.[4][5] In Pakistan, Shina is the major language in Gilgit-Baltistan spoken by an estimated 1,146,000 people living mainly in Gilgit-Baltistan and Kohistan.[4][6] A small community of Shina speakers is also found in India, in the Guraiz valley of Jammu and Kashmir and in Dras valley of Ladakh.[4] Outliers of Shina language such as Brokskat are found in Ladakh, Kundal Shahi in Azad Kashmir, Palula and Sawi in Chitral, Ushojo in the Swat Valley and Kalkoti in Dir.[4]

Until recently, there was no writing system for the language. A number of schemes have been proposed, and there is no single writing system used by speakers of Shina language.[7] Shina is mostly a spoken language and not a written language. Most Shina speakers do not write their language.

Due to effects of dominant languages in Pakistani media like Urdu, Standard Punjabi and English and religious impact of Arabic and Persian, Shina like other languages of Pakistan are continuously expanding its vocabulary base with loan words.[8] It has close relationship with other Indo-Aryan languages, especially Standard Punjabi, Western Punjabi, Sindhi, and the dialects of Western Pahari.[9]

Distribution

[edit]In Pakistan

[edit]There are an estimated 1,146,000 speakers of both Shina and Kohistani Shina in Pakistan according to Ethnologue (2018), a majority of them in the province of Khyber-Pakhtunkwa and Gilgit-Baltistan. A small community of Shina speakers is also settled in Neelam valley of Azad Jammu and Kashmir.[10][11]

In India

[edit]A small community of Shina speakers is also settled in India in the far north of Kargil district bordering Gilgit-Baltistan. Their population is estimated to be around 32,200 according to 2011 census.[10]

Phonology

[edit]The following is a description of the phonology of the Drasi, Sheena variety spoken in India and the Kohistani variety in Pakistan.

Vowels

[edit]The Shina principal vowel sounds:[12]

| Front | Mid | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrd. | rnd. | |||

| High | i | u | ||

| High-mid | e | o | ||

| Low-mid | ɛ | ə | ʌ | ɔ |

| Low | (æ) | a | ||

All vowels but /ɔ/ can be either long or nasalized, though no minimal pairs with the contrast are found.[12] /æ/ is heard from loanwords.[13]

Diphthongs

[edit]In Shina there are the following diphthongs:[14]

- falling: ae̯, ao̯, eə̯, ɛi̯, ɛːi̯, ue̯, ui̯, oi̯, oə̯;

- falling nasalized: ãi̯, ẽi̯, ũi̯, ĩũ̯, ʌĩ̯;

- raising: u̯i, u̯e, a̯a, u̯u.

Consonants

[edit]In India, the dialects of the Shina language have preserved both initial and final OIA consonant clusters, while the Shina dialects spoken in Pakistan have not.[15]

| Labial | Coronal | Retroflex | Post-alv./ Palatal |

Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | Voiceless | p | t | ʈ | k | q[a] | ||

| Aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | ʈʰ | kʰ | ||||

| Voiced | b | d | ɖ | ɡ | ||||

| Breathy[a] | bʱ | dʱ | ɖʱ | ɡʱ | ||||

| Affricate | Voiceless | t͡s | ʈ͡ʂ | t͡ʃ | ||||

| Aspirated | t͡sʰ | ʈ͡ʂʰ | t͡ʃʰ | |||||

| Voiced | d͡z[b] | d͡ʒ[b] | ||||||

| Breathy | d͡ʒʱ[a] | |||||||

| Fricative | Voiceless | (f) | s | ʂ | ʃ | x[b] | h | |

| Voiced | z | ʐ | ʒ[b] | ɣ[b] | ɦ[b] | |||

| Nasal | m (mʱ)[a] | n | ɳ | ŋ | ||||

| Lateral | l (lʱ)[a] | |||||||

| Rhotic | r | ɽ[c] | ||||||

| Semivowel | ʋ~w | j | ||||||

Tone

[edit]Shina words are often distinguished by three contrasting tones: level, rising, and falling tones. Here is an example that shows the three tones:

"The" (تھےࣿ) has a level tone and means the imperative "Do!"

When the stress falls on the first mora of a long vowel, the tone is falling. Thée (تھےٰ) means "Will you do?"

When the stress falls on the second mora of a long vowel, the tone is rising. Theé (تھےٗ) means "after having done".

Orthography

[edit]| Shina alphabet |

|---|

| ا ب پ ت ٹ ث ج چ ح خ څ ځ ڇ د ڈ ذ ر ڑ ز ژ ڙ س ش ݜ ص ض ط ظ ع غ ڠ ف ق ک گ ل م ن ݨ ں و ہ (ھ) ء ی ے |

|

Extended Perso-Arabic script |

Shina is one of the few Dardic languages with a written tradition.[16] However, it was an unwritten language until a few decades ago.[17] Only in the late 2010s has Shina orthography been standardized and primers as well as dictionaries endorsed by the territorial government of Gilgit-Baltistan have been published. [18][19]

Since the first attempts at accurately representing Shina's phonology in the 1960s there have been several proposed orthographies for the different varieties of the language, with debates centering on how to write several retroflex sound not present in Urdu and whether vowel length and tone should be represented.[20]

There are two main orthographic conventions now, one in Pakistani-controlled areas of Gilgit-Baltistan and in Kohistan, and the other in Indian-controlled area of Dras, Ladakh.

Below alphabet has been standardized, documented, and popularized thanks to efforts of literaturists such as Professor Muhammad Amin Ziya, Shakeel Ahmad Shakeel, and Razwal Kohistani, and it has been developed for all Shina language dialects, including Gilgit dialect and Kohistani dialect, which [18][19][21] There are minor differences, such as the existence of the letter ڦ in Kohistani dialect of Shina. Furthermore, variations and personal preferences can be observed across Shina documents. For example, it is common to see someone use سً instead of ݜ for [ʂ], or use sukun ◌ْ (U+0652) instead of small sideway noon ◌ࣿ (U+08FF) to indicate short vowels. However, these variations are no longer an issue. Another issue is that of how to write loanwords that use letters not found in Shina language, for example letters "س / ث / ص", which all sound like [s] in Shina. Some documents preserve the original spelling, despite the letters being homophones and not having any independent sound of their own, similar to orthographic conventions of Persian and Urdu. Whereas other documents prefer to rewrite all loanwords in a single Shina letter, and thus simplify the writing, similar to orthographic conventions of Kurdish and Uyghur.

Shina vowels are distinguished by length, by whether or not they're nasalized, and by tone. Nasalization is represented like other Perso-Arabic alphabets in Pakistan, with Nun Ghunna (ن٘ـ / ـن٘ـ / ں). In Shina, tone variation only occur when there is a long vowel. There are conventions unique to Shina to show the three tones. In Shina conventions, specific diacritics are shown in conjunction with the letters alif, waw, buṛi ye, and ye (ا، و، یـ، ی، ے), as these letters are written down to represent long vowels. The diacritics inverted damma ◌ٗ (U+0657) and superscript alef ◌ٰ (U+0670) represent a rising tone and a falling tone respectively. Another diacritic, a small sideway noon ◌ࣿ (U+08FF) is used to represent short vowels when need be.[22]

Consonants

[edit]Below table shows Shina consonants.[18][19]

| Name | Forms | IPA | Transliteration[23] | Unicode | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shina | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial | ||||

| الف alif |

ا | ـا | ـا | ا / آ | [ʌ], [∅], silent | – / aa | U+0622 U+0627 |

At the beginning of a word it can either come with diacritic, or it can come in form of alif-madda (آ), or it can be stand-alone and silent, succeeded by a vowel letter. Diacritics اَ اِ، اُ can be omitted in writing. |

| بےࣿ be |

ب | ـب | ـبـ | بـ | [b] | b | U+0628 | |

| پےࣿ pe |

پ | ـپ | ـپـ | پـ | [p] | p | U+067E | |

| تےࣿ te |

ت | ـت | ـتـ | تـ | [t̪] | t | U+062A | |

| ٹےࣿ te |

ٹ | ـٹ | ـٹـ | ٹـ | [ʈ] | ṭ | U+0679 | |

| ثےࣿ se |

ث | ـث | ـثـ | ثـ | [s] | s | U+062B | Only used in loanwords of Arabic origin. Can be replaced with letter siin س.[18] |

| جوࣿم ǰom |

ج | ـج | ـجـ | جـ | [d͡ʒ] | ǰ | U+062C | |

| چےࣿ če |

چ | ـچ | ـچـ | چـ | [t͡ʃ] | č | U+0686 | |

| څےࣿ tse |

څ | ـڅ | ـڅـ | څـ | [t͡s] | ts | U+0685 | Letter borrowed from Pashto alphabet. In the official Shina orthography in Indian-Controlled Kashmir, the letter ژ is used.[24] |

| ڇےࣿ c̣e |

ڇ | ـڇ | ـڇـ | ڇـ | [ʈ͡ʂ] | c̣ | U+0687 | Unique letter for Shina language. Some Shina literatures and documents use two horizontal lines instead of four dots, use حٍـ instead of ڇـ. In the official Shina orthography in Indian-Controlled Kashmir, the letter چْ is used.[24] |

| حےࣿ he |

ح | ـح | ـحـ | حـ | [h] | h | U+062D | Only used in loanwords of Arabic origin. Can be replaced with letter hay ہ.[18] |

| خےࣿ khe |

خ | ـخ | ـخـ | خـ | [x]~[kʰ] | kh | U+062D | Only used in loanwords of Arabic origin. Can be replaced with digraph letter khe کھ.[18] |

| دال daal |

د | ـد | - | - | [d̪] | d | U+062F | |

| ڈال ḍaal |

ڈ | ـڈ | - | - | [ɖ] | ḍ | U+0688 | |

| ذال zaal |

ذ | ـذ | - | - | [z] | z | U+0688 | Only used in loanwords of Arabic origin. Can be replaced with letter ze ز.[18] |

| رےࣿ re |

ر | ـر | - | - | [r] | r | U+0631 | |

| ڑےࣿ ṛe |

ڑ | ـڑ | - | - | [ɽ] | ṛ | U+0691 | |

| زےࣿ ze |

ز | ـز | - | - | [z] | z | U+0632 | |

| ژےࣿ že / ǰe |

ژ | ـژ | - | - | [ʒ]~[d͡ʒ] | ž / ǰ | U+0632 | Only used in loanwords of Persian and European origin. Can be replaced with letter jom ج.[18] |

| ڙےࣿ ẓe |

ڙ | ـڙ | - | - | [ʐ] | ẓ | U+0699 | Unique letter for Shina language. Some Shina literatures and documents use two horizontal lines instead of four dots, use رً instead of ڙ. In the official Shina orthography in Indian-Controlled Kashmir, the letter جْ is used.[24] |

| سِین siin |

س | ـس | ـسـ | سـ | [s] | s | U+0633 | |

| شِین šiin |

ش | ـش | ـشـ | شـ | [ʃ] | š | U+0634 | |

| ݜِین ṣiin |

ݜ | ـݜ | ـݜـ | ݜـ | [ʂ] | ṣ | U+0687 | Unique letter for Shina language. Some Shina literatures and documents use two horizontal lines instead of four dots, use سً instead of ݜ. In the official Shina orthography in Indian-Controlled Kashmir, the letter شْ is used.[24] |

| صواد swaad |

ص | ـص | ـصـ | صـ | [s] | s | U+0635 | Only used in loanwords of Arabic origin. Can be replaced with letter siin س.[18] |

| ضواد zwaad |

ض | ـض | ـضـ | ضـ | [z] | z | U+0636 | Only used in loanwords of Arabic origin. Can be replaced with letter ze ز.[18] |

| طوے tooy |

ط | ـط | ـطـ | طـ | [t̪] | t | U+0637 | Only used in loanwords of Arabic origin. Can be replaced with letter te ت.[18] |

| ظوے zooy |

ظ | ـظ | ـظـ | ظـ | [z] | z | U+0638 | Only used in loanwords of Arabic origin. Can be replaced with letter ze ز.[18] |

| عَین ayn |

ع | ـع | ـعـ | عـ | [ʔ], silent | - | U+0639 | Only used in loanwords of Arabic origin. Can be replaced with letter alif ا.[18] |

| غَین gayn |

غ | ـغ | ـغـ | غـ | [ɣ]~[ɡ] | g | U+0639 | Only used in loanwords of Arabic and Turkic origin. Can be replaced with letter gaaf گ.[18] |

| فےࣿ fe / phe |

ف | ـف | ـفـ | فـ | [f]~[pʰ] | f / ph | U+0641 | Only used in loanwords. Can be replaced with digraph letter phe پھ.[18] |

| قاف qaaf / kaaf |

ق | ـق | ـقـ | قـ | [q]~[k] | q / k | U+0642 | Only used in loanwords of Arabic and Turkic origin. Can be replaced with letter kaaf ک.[18] |

| کاف kaaf |

ک | ـک | ـکـ | کـ | [k] | k | U+0643 | |

| گاف gaaf |

گ | ـگ | ـگـ | گـ | [ɡ] | g | U+06AF | |

| لام laam |

ل | ـل | ـلـ | لـ | [l] | l | U+0644 | |

| مِیم miim |

م | ـم | ـمـ | مـ | [m] | m | U+0645 | |

| نُون nuun |

ن | ـن | ـنـ | نـ | [n] | n | U+0646 | |

| نُوݨ nuuṇ |

ݨ | ـݨ | ـݨـ | ݨـ | [ɳ] | ṇ | U+0768 | In the official Shina orthography in Indian-Controlled Kashmir, the letter نْ is used.[24] |

| نُوں / نُون گُنَہ nū̃ / nūn gunna |

ں / ن٘ | ـں | ـن٘ـ | ن٘ـ | /◌̃/ | ◌̃ | For middle of word: U+0646 plus U+0658 For end of word: U+06BA |

|

| نُون٘گ nuung |

ن٘گ | ـن٘گ | ـن٘گـ | ن٘گـ | /ŋ/ | ng | U+0646 plus U+0658 and U+06AF |

A digraph, counted as a letter.[18] |

| واؤ waaw |

و / او | ـو | - | - | [oː] / [w] | w / ō | U+0648 | The letter waaw can either represent consonant ([w/v]) or vowel ([oo]). It can also act as a carrier of vowel diacritics, representing several other vowels. At the beginning of a word, when representing a consonant, the letter waaw will appear as a standalone character, followed by the appropriate vowel. If representing a vowel at the beginning of a word, the letter waaw needs to be preceded by an alif ا. When the letter waaw comes at the end of the word representing a consonant sound [w], a hamza is used ؤ to label it as such and avoid mispronunciation as a vowel.[22] |

| ہَے hai |

ہ | ـہ | ـہـ | ہـ | [h] | h | U+0646 | This letter differs from do-ac̣hi'ii hay (ھ) and they are not interchangeable. Similar to Urdu,do-chashmi hē (ھ) is exclusively used as a second part of digraphs for representing aspirated consonants. In initial and medial position, the letter hē always represents the consonant [h]. In final position, The letter hē can either represent consonant ([h]) or it can demonstrate that the word ends with short vowels a ◌َہ / ـَہ, i ◌ِہ / ـِہ, u ◌ُہ / ـُہ.[22] |

| ہَمزَہ hamza |

ء | - | - | - | [ʔ], silent | ’ | U+0621 | Used mid-word to indicate separation between a syllable and another that starts with a vowel. hamza on top of letters waaw and ye at end of a word serves a function too. When the letter waaw or ye come at the end of the word representing a consonant sound [w] or [y], a hamza is used ؤ / ئ / ـئ to label it as such and avoid mispronunciation as a vowel.[18][22] |

| یےࣿ / لیکھی یےࣿ ye / leekhii ye |

ی | ـی | ـیـ | یـ | [j] / [e] / [i] | y / e / i | U+06CC | The letter ye can either represent consonant ([j]) or vowels ([e]/[i]). It can also act as a carrier of vowel diacritics, representing several other vowels. At the beginning of a word, when representing a consonant, the letter ye will appear as a standalone character, followed by the appropriate vowel. If representing a vowel at the beginning of a word, the letter ye needs to be preceded by an alif ا. When the letter ye comes at the end of the word representing a consonant sound [j], a hamza is used ئ to label it as such and avoid mispronunciation as a vowel. When representing a vowel at the end of a word, it can only be [i]. For vowel [e], the letter buṛi ye ے is used. |

| بُڑیࣿ یےࣿ buṛi ye |

ے | ـے | - | - | [e] / [j] | e / y | U+06D2 | The letter buṛi ye only occurs in final position. The letter buṛi ye represents the vowel "ē" [eː] or the consonant "y" [j]. |

| بھےࣿ bhe |

بھ | ـبھ | ـبھـ | بھـ | [bʱ] | bh | U+0628 and U+06BE |

A digraph, counted as a letter.[18] |

| پھےࣿ phe |

پھ | ـپھ | ـپھـ | پھـ | [pʰ] | ph | U+067E and U+06BE |

A digraph, counted as a letter.[18] |

| تھےࣿ the |

تھ | ـتھ | ـتھـ | تھـ | [t̪ʰ] | th | U+062A and U+06BE |

A digraph, counted as a letter.[18] |

| ٹھےࣿ ṭhe |

ٹھ | ـٹھ | ـٹھـ | ٹھـ | [ʈʰ] | ṭh | U+0679 and U+06BE |

A digraph, counted as a letter.[18] |

| جھوࣿم ǰhom |

جھ | ـجھ | ـجھـ | جھـ | [d͡ʒʱ] | ǰh | U+062C and U+06BE |

A digraph, counted as a letter.[18] |

| چھےࣿ čhe |

چھ | ـچھ | ـچھـ | چھـ | [t͡ʃʰ] | čh | U+0686 and U+06BE |

A digraph, counted as a letter.[18] |

| څھےࣿ tshe |

څھ | ـڅھ | ـڅھـ | څھـ | [t͡sʰ] | tsh | U+0685 and U+06BE |

A digraph, counted as a letter.[18] In the official Shina orthography in Indian-Controlled Kashmir, the letter ژھ is used.[24] |

| ڇھےࣿ c̣he |

ڇھ | ـڇھ | ـڇھـ | ڇھـ | [ʈ͡ʂʰ] | c̣h | U+0687 and U+06BE |

A digraph, counted as a letter.[18] In the official Shina orthography in Indian-Controlled Kashmir, the letter چْھ is used.[24] |

| کھےࣿ khe |

کھ | ـکھ | ـکھـ | کھـ | [kʰ] | kh | U+0643 and U+06BE |

A digraph, counted as a letter.[18] |

| گھےࣿ ghe |

گھ | ـگھ | ـگھـ | گھـ | [ɡʱ] | gh | U+06AF and U+06BE |

A digraph, counted as a letter.[18] |

Vowels

[edit]There are five vowels in Shina language. Each of the five vowels in Shina have a short version and a long version. Shina is also a tonal language. Short vowels in Shina have a short high level tone ˥. Long vowels can either have "no tone", i.e. a long flat tone ˧, a long rising tone [˨˦], or a long falling tone (/˥˩/.

All five vowels have a defined way of presentation in Shina orthographic conventions, including letters and diacritics. Although diacritics can and are occasionally dropped in writing. Short vowels [a], [i], and [u] are solely written with diacritics. Short vowels [e] and [o] are written with letters waw and buṛi ye. A unique diacritic, a small sideway noon ◌ࣿ (U+08FF) is used on top of these letters to indicate a short vowel.[22] Long vowels are written with a combination of diacritics and letters alif, waaw or ye.

Below table shows short vowels at the beginning, middle, and end of a word.[22][23]

| Vowel at the beginning of the word | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | e | i | o | u |

| اَ | ایࣿـ / اےࣿ | اِ | اوࣿ | اُ |

| Vowel at the middle of the word | ||||

| ـَ | یࣿـ / ـیࣿـ | ـِ | وࣿ / ـوࣿ | ـُ |

| Vowel at the end of the word | ||||

| ◌َہ / ـَہ | ےࣿ / ـےࣿ | ◌ِہ / ـِہ | وࣿ / ـوࣿ | ◌ُہ / ـُہ |

Below table shows long vowels at the beginning, middle, and end of a word, with "no tone", i.e. a long flat tone ˧.[22][23]

| Vowel at the beginning of the word | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aa | ee | ii | oo | uu |

| آ | ایـ / اے | اِیـ / اِی | او | اُو |

| Vowel at the middle of the word | ||||

| ا / ـا | یـ / ـیـ | ◌ِیـ / ـِیـ | و / ـو | ◌ُو / ـُو |

| Vowel at the end of the word | ||||

| ا / ـا | ے / ـے | ◌ِی / ـِی | و / ـو | ◌ُو / ـُو |

Below table shows long vowels at the beginning, middle, and end of a word, with a long rising tone [˨˦].[22][23]

| Vowel at the beginning of the word | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aá | eé | ií | oó | uú |

| آٗ | ایٗـ / اےٗ | اِیٗـ / اِیٗ | اوٗ | اُوٗ |

| Vowel at the middle of the word | ||||

| اٗ / ـاٗ | یٗـ / ـیٗـ | ◌ِیٗـ / ـِیٗـ | وٗ / ـوٗ | ◌ُوٗ / ـُوٗ |

| Vowel at the end of the word | ||||

| اٗ / ـاٗ | ےٗ / ـےٗ | ◌ِیٗ / ـِی | وٗ / ـوٗ | ◌ُوٗ / ـُوٗ |

Below table shows long vowels at the beginning, middle, and end of a word, with a long falling tone (/˥˩/.[22][23]

| Vowel at the beginning of the word | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| áa | ée | íi | óo | úu |

| آٰ | ایٰـ / اےٰ | اِیٰـ / اِیٰ | اوٰ | اُوٰ |

| Vowel at the middle of the word | ||||

| اٰ / ـاٰ | یٰـ / ـیٰـ | ◌ِیٰـ / ـِیٰـ | وٰ / ـوٰ | ◌ُوٰ / ـُوٰ |

| Vowel at the end of the word | ||||

| اٰ / ـاٰ | ےٰ / ـےٰ | ◌ِیٰ / ـِیٰ | وٰ / ـوٰ | ◌ُوٰ / ـُوٰ |

Text sample

[edit]Below is a short passage of sample phrases.[25]

| Shina Arabic alphabet (orthography of Gilgit-Baltistan and Kohistan) | اَساٰ ایࣿک سَنِیٰلو گوٰݜ پَشیٰس. اَساٰ دَہِیٰلو گوٰݜ پَشیٰس. گوٰݜ جیٰجِہ دَہِیٰلوࣿ لیٰل بِیٰنوࣿ. گوٰݜ وَزِیٗ نَہ دِتوباٰلو. |

|---|---|

| Latin Transliteration | Asáa ek saníilo góoṣ pašées. Asáa dahíilo góoṣ pašées. Góoṣ jéeji dahíilo léel bíino. Góoṣ wazií na ditobáalo. |

| Translation | We saw a completely constructed house. We saw the house burnt down. The house appears burnt by someone. The house could not collapse completely. |

See also

[edit]- Brokskat language

- Kundal Shahi language

- Ushoji language

- Kalkoti language

- Palula language

- Savi language

References

[edit]- ^ "Shina". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 2019-06-06. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ "Shina, Kohistani". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 2019-06-05. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ "Ethnologue report for Shina". Ethnologue.

- ^ a b c d Saxena, Anju; Borin, Lars (2008-08-22). Lesser-Known Languages of South Asia: Status and Policies, Case Studies and Applications of Information Technology. Walter de Gruyter. p. 137. ISBN 978-3-11-019778-5.

Shina is an Indo-Aryan language of the Dardic group, spoken in the Karakorams and the western Himalayas: Gilgit, Hunza, the Astor Valley, the Tangir-Darel valleys, Chilas and Indus Kohistan, as well as in the upper Neelam Valley and Dras. Outliers of Shina are found in Ladakh (Brokskat), Chitral (Palula and Sawi), Swat (Ushojo; Bashir 2003: 878) and Dir (Kalkoti).

- ^ Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (2007-07-26). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. p. 1018. ISBN 978-1-135-79710-2.

- ^ "Shina". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 2019-06-06. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ Braj B. Kachru; Yamuna Kachru; S. N. Sridhar (2008). Language in South Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 144. ISBN 9781139465502.

- ^ Shams, Shammim Ara (2020). "The Impact of Dominant Languages on Regional Languages: A Case Study of English, Urdu and Shina". Pakistan Social Sciences Review. 4 (III): 1092–1106. doi:10.35484/pssr.2020(4-III)79.

- ^ M. Oranskij, “Indo-Iranica IV. Tadjik (Régional) Buruǰ ‘Bouleau,’” in Mélanges linguistiques offerts à Émile Benveniste, Paris, 1975, pp. 435–40.

- ^ a b "Shina". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2022-05-22.

- ^ "Shina, Kohistani". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2022-05-22.

- ^ a b Rajapurohit 2012, p. 28–31.

- ^ Schmidt & Kohistani 2008, p. 16.

- ^ Rajapurohit 2012, p. 32–33.

- ^ Itagi, N. H. (1994). Spatial aspects of language. Central Institute of Indian Languages. p. 73. ISBN 9788173420092. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

The Shina dialects of India have retained both initial and final OIA consonant clusters. The Shina dialects of Pakistan have lost this distinction.

- ^ Bashir 2003, p. 823. "Of the languages discussed here, Shina (Pakistan) and Khowar have developed a written tradition and a significant body of written material exists."

- ^ Schmidt 2003–2004, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Ziya, Muhammad Amin, Prof. (2010, October). Gilti Shina Urdu Dictionary / ݜِناٗ - اُردو لغت. Publisher: Zia Publications, Gilgit. ضیاء پبلیکبشنز، گلیٗتISBN 978-969-942-00-8 https://archive.org/details/MuhammadAmeenZiaGiltiShinaUrduDictionary/page/n5/mode/1up

- ^ a b c Razwal Kohistani. (Latest Edition: 2020)(First published: 1996) Kohistani Shina Primer, ݜݨیاٗ کستِین٘و قاعده. Publisher: Indus Kohistan Publications. https://archive.org/details/complete-shina-kohistani-qaida-by-razwal-kohistani_202009/page/n1/mode/1up

- ^ Bashir 2016, p. 806.

- ^ Pamir Times (September 5, 2008), "Shina language gets a major boost with Shakeel Ahmad Shakeel's efforts" https://pamirtimes.net/2008/09/05/shina-language-gets-a-major-boost-with-shakeel-ahmad-shakeels-efforts/

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Shakeel Ahmad Shakeel. (2008). Sheena language An overview of the teaching and learning system / شینا زبان نظام پڑھائی لکھائی کا جائزہ. https://z-lib.io/book/14214726

- ^ a b c d e Radloff, Carla F. with Shakil Ahmad Shakil.1998. Folktales in the Shina of Gilgit. Islamabad: The National Institute of Pakistan Studies and Summer Institute of Linguistics. [1]

- ^ a b c d e f g Samoon, M. (2016). Shina Language Proverbs (Urdu: شینا محاورے اور مثالیں)(Shina: شْنْا مَحاوَرآے گےٚ مِثالےٚ). Rabita Publications. [2]

- ^ Schmidt, R. L., & Kohistani, R. (2008). A grammar of the Shina language of Indus kohistan. Harrassowitz.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bashir, Elena L. (2003). "Dardic". In George Cardona; Dhanesh Jain (eds.). The Indo-Aryan languages. Routledge language family series. Y. London: Routledge. pp. 818–94. ISBN 978-0-7007-1130-7.

- Bashir, Elena L. (2016). "Perso-Arabic adaptions for South Asian languages". In Hock, Hans Henrich; Bashir, Elena (eds.). The languages and linguistics of South Asia: a comprehensive guide. World of Linguistics. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 803–9. ISBN 978-3-11-042715-8.

- Rajapurohit, B. B. (1975). "The problems involved in the preparation of language teaching material in a spoken language with special reference to Shina". Teaching of Indian languages: seminar papers. University publication / Department of Linguistics, University of Kerala. V. I. Subramoniam, Nunnagoppula Sivarama Murty (eds.). Trivandrum: Dept. of Linguistics, University of Kerala.

- Rajapurohit, B. B. (1983). Shina phonetic reader. CIIL Phonetic Reader Series. Mysore: Central Institute of Indian Languages.

- Rajapurohit, B. B. (2012). Grammar of Shina Language and Vocabulary : (Based on the dialect spoken around Dras) (PDF).

- Schmidt, Ruth Laila (2003–2004). "The oral history of the Daṛmá lineage of Indus Kohistan" (PDF). European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (25/26): 61–79. ISSN 0943-8254.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Schmidt, Ruth Laila; Kohistani, Razwal (2008). A grammar of the Shina language of Indus Kohistan. Beiträge zur Kenntnis südasiatischer Sprachen und Literaturen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-05676-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Buddruss, Georg (1983). "Neue Schriftsprachen im Norden Pakistans. Einige Beobachtungen". In Assmann, Aleida; Assmann, Jan; Hardmeier, Christof (eds.). Schrift und Gedächtnis: Beiträge zur Archäologie der literarischen Kommunikation. W. Fink. pp. 231–44. ISBN 978-3-7705-2132-6. A history of the development of writing in Shina

- Degener, Almuth; Zia, Mohammad Amin (2008). Shina-Texte aus Gilgit (Nord-Pakistan): Sprichwörter und Materialien zum Volksglauben, gesammelt von Mohammad Amin Zia. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05648-9. Contains a Shina grammar, German-Shina and Shina-German dictionaries, and over 700 Shina proverbs and short texts.

- Radloff, Carla F. (1992). Backstrom, Peter C.; Radloff, Carla F. (eds.). Languages of northern areas. Sociolinguistic survey of Northern Pakistan. Vol. 2. Islamabad, Pakistan: National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University.

- Rensch, Calvin R.; Decker, Sandra J.; Hallberg, Daniel G. (1992). Languages of Kohistan. Sociolinguistic survey of Northern Pakistan. Islamabad, Pakistan: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i- Azam University.

- Zia, Mohammad Amin (1986). Ṣinā qāida aur grāimar (in Urdu). Gilgit: Zia Publishers.

- Zia, Mohammad Amin. Shina Lughat (Shina Dictionary). Contains 15000 words plus material on the phonetics of Shina.

External links

[edit]- Sasken Shina, contains materials in and about the language

- 1992 Sociolinguistic Survey of Shina

- Shina Language Textbook for Class5

- Shina Language Textbook for Class6