Nabi Samwil

an-Nabi Samwil | |

|---|---|

| Arabic transcription(s) | |

| • Arabic | النبي صموئيل |

| • Latin | an-Nebi Samwil (official) an-Nabi Samuil (unofficial) |

Aerial view | |

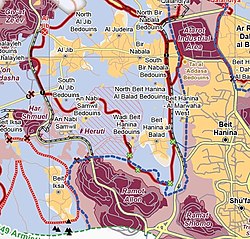

Nabi Samwil shown within the Area C "National Park" (hashed area) | |

Location of an-Nabi Samwil within Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 31°49′58″N 35°10′49″E / 31.83278°N 35.18028°E | |

| Palestine grid | 167/137 |

| State | State of Palestine |

| Governorate | Jerusalem |

| Government | |

| • Type | Local Development Committee |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,592 dunams (1.6 km2 or 0.6 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 908 m (2,979 ft) |

| Population (2017)[1] | |

| • Total | 234 |

| • Density | 150/km2 (380/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | "the prophet Samuel"[2] |

An-Nabi Samwil, also called al-Nabi Samuil (Arabic: النبي صموئيل an-Nabi Samu'il, translit: "the prophet Samuel"), is a Palestinian village in the Quds Governorate of the State of Palestine, located in the West Bank (Area C), four kilometers north of Jerusalem. The village is built up around the Mosque of Nabi Samwil, containing the Tomb of Samuel; the village's Palestinian population has since been removed by the Israeli authorities from the village houses to a new location slightly down the hill. The village had a population of 234 in 2017.[1]

A tradition dating back to the Byzantine period places here the tomb of Prophet Samuel. In the 6th century, a monastery was built at the site in honor of Samuel, and during the early Arab period the place was known as Dir Samwil (the Samuel Monastery).[3] In the 12th century, during the Crusader period, a fortress was built on the area.[3] In the 14th century, during the Mameluk period, a mosque was built over the ruins of the Crusader fortress.[3] The purported tomb itself is in an underground chamber of the mosque, which has been repurposed after 1967 as a synagogue, today with separate prayer areas for Jewish men and women.

Geography

Nabi Samwil is situated atop of a mountain, 890 meters above sea level, in the Seam Zone, four kilometers north of the Jerusalem neighborhood of Shuafat and southwest of Ramallah.[4] Nearby localities include Beit Iksa to the south, al Jib to the north, Beit Hanina to the east and Biddu to the west.[5]

The village consisted of 1,592 dunams of which only 5 dunams were built-up.[6]

Tomb of Samuel tradition

A 6th-century Christian author identified the site as Samuel's burial place, and it has been traditionally been associated as such by Jews, Christians and Muslims. According to the Hebrew Bible, the prophet was buried at his hometown, Ramah (1 Samuel 25:1, 28:3), which is located near Geba, while this site is identified as Mizpah in Benjamin.[7] As Judas Machabeus, preparing for war with the Syrians, gathered his men "to Maspha, over against Jerusalem: for in Maspha was a place of prayer heretofore in Israel".[8]

The 12th-century Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela visited the site in 1173. According to him, the Christian Crusaders had found the bones of Samuel "close to a Jewish synagogue" in Ramla on the coastal plain (which he misidentified as biblical Ramah), and reburied them at present-day Nabi Samwil. He wrote that a large church dedicated to St. Samuel had been built over the reburied remains.[9]

History: shrine and village

An old tradition holds that the village contains the tomb of the prophet Samuel, whose Arabic name is Nabi Samwil,[4][10] hence the name of the Arab village.

Byzantine period

A monastery was built by the Byzantines at Nabi Samwil, serving as a hostel for Christian pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem. The monastery was restored and enlarged during the reign of Justinian I in the mid-6th-century CE.[11] Since then, the site has been a place of pilgrimage for Jews, Christians and Muslims alike.[4]

Early Muslim period

The tomb continued to be in use throughout the Early Muslim period in Palestine from the 7th to the 10th century.[11]

Jerusalem-born geographer al-Muqaddasi recounted in 985 CE, a story which he had heard from his uncle concerning the place: A certain sultan wanted to take possession of Dayr Shamwil, which he describes as a village about a farsakh from Jerusalem. The Sultan asked the owner to describe the village, at which the owner enumerated the ills of the place ("hard is the labour,/the profit is low./Weeds are all over,/almonds are bitter,/one bushel you sow,/one bushel you reap.") After hearing this the ruler exclaimed "Begone! We have no need for your village!"[12] 13th-century Syrian geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi, describes "Mar Samwil" or "Maran Samwil" as "a small town in the neighbourhood of Jerusalem. Mar in Syriac signifies al-Kass, 'the priest', and Samwil is the name of the Doctors of Law."[13] During Islamic times, Nabi Samwil became a centre for pottery production,[14] supplying nearby Jerusalem, as well as Ramla and Caesarea.[15]

Crusader/Ayyubid period

In 1099, the Crusaders conquered Palestine from the Arab Fatimids and received their first view of Jerusalem from the mountain upon which Nabi Samwil is built, thus naming it Mont Joie ("Mountain of Joy"). They soon constructed a fortress there to fend off Muslim raiding of Jerusalem's northern approaches as well as to shelter pilgrim convoys.[11]

In 1157, the Crusaders constructed a church at Samuel's tomb.[4] King Baldwin II of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem entrusted Nabi Samwil to Cistercians religious order, who built a monastery there and then handed it over to the Premonstratensians in the 1120s.[14] The 12th-century Jewish traveller, Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela, visited the site when he travelled the land in 1173, noting that the Crusaders had found the bones of Samuel in a Jewish cemetery in Ramla on the coastal plain and reburied them here, overlooking the Holy City. He wrote that a church dedicated to St. Samuel of Shiloh had been built on the hill.[16] This may refer to the abbey church of St. Samuel built by Premonstratensian canons and inhabited from 1141 to 1244.[17]

After the Ayyubids under Saladin conquered much of interior Palestine in 1187, the church and monastery were turned into a mosque and since then remained in Muslim hands. in 1192, Richard the Lionheart reached Nabi Samwil, but did not take it.[18] Jewish pilgrimage, which favoured visits in April and May each year, resumed after the Ayyubids conquered the area, and it became an important center for Muslim-Jewish interaction.[19]

Mamluk period

During the Mamluk period, Christian pilgrims continued to visit the site, including the traveller known as John Mandeville, and Margery Kempe.[20]

In the 15th-century, Jews built a synagogue adjacent to the mosque and resumed pilgrimages to the site after losing that privilege during the Crusader period. Though they occasionally encountered difficulties with local notables, the Jews' right to visit the shrine was reaffirmed twice by the Ottomans, and the sultan asked the qadi of Jerusalem to punish anyone who might obstruct their right and the long tradition of Jewish pilgrimage. Mujir ad-Din referring to Jerusalem's size writes "From the north it reaches the village wherein is the tomb of the prophet Shamwil, may Allah bless him and give him peace."[21]

Ottoman period

In 1517, Palestine incorporated into the Ottoman Empire after it was captured from the Mamluks, and by 1596, Nabi Samwil appeared in the Ottoman tax registers as being in the nahiya of Quds in the liwa of Al-Quds. It had a population of 5 households, all Muslim. The villagers paid a fixed tax rate of 25% on various agricultural products, including wheat, barley, olive trees, vineyards, fruit trees, occasional revenues, goats and/or beehives; a total of 2,200 akçe.[22]

The Crusader church was incorporated into the village mosque,[4] built in 1730 under the Ottoman Empire.[11]

In 1838 Edward Robinson noted en-Neby Samwil as a Muslim village, part of the El-Kuds district.[23] He further noted that the "mosk is here the principal object; and is regarded by Jews, Christians, and Muhammedans, as covering the tomb of the prophet Samuel."[24]

An Ottoman village list of about 1870 showed that Nabi Samwil had 6 houses and a population of 20, though the population count included only men.[25][26]

In 1883, the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) described it as small hamlet of adobe huts, perched on top of the ridge, amid the remains of the Crusader ruins. There was a spring to the north.[27]

In 1896 the population of Nebi Samwil was estimated to be about 81 persons.[28]

World War and British Mandate period

Nabi Samwil was heavily damaged by Turkish shells in 1917 while fighting British forces, but the village was rebuilt and resettled in 1921.[29] The Ottoman mosque, destroyed in war, was restored by the Supreme Muslim Council during the British Mandate period.[10][11]

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Nabi Shemweil had a population 121, all Muslims.[30] increasing slightly in the 1931 census to 138, one Christian and the rest Muslim, occupying a total of 117 houses.[31]

In the 1945 statistics Nabi Samwil had a population of 200, all Muslims,[32] with 2,150 dunams of land, according to an official land and population survey.[33] Of this, 293 dunams were plantations and irrigable land, 986 used for cereals,[34] while 3 dunams were built-up land.[35]

1948 war and Jordanian period

On April 23, 1948, during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, a Palmach division attacked Nabi Samwil with the intention of capturing the village for Israel. The operation failed, since its local defenders had been notified that nearby Beit Iksa was attacked and thus prepared for a Jewish assault. Over 40 Palmach troops were killed in the battle with minimal Arab casualties.[36]

From 1948 to 1967, Nabi Samwil was used by the Arab Legion of Jordan as a military post guarding access to Jerusalem.[4]

In 1961, the population of Nabi Samwil was 168.[37]

1967, aftermath

Since the 1967 Six-Day War, Nabi Samwil has been under Israeli occupation.[4]

After Israel's victory and occupation in the war, during which most of the village's 1,000 inhabitants[38][39] had fled, the shrine became predominantly Jewish, and settlers attempted to wrest control of the area.[40][19] Throughout the 1970s, the Israeli authorities demolished the historic village built around the shrine, forcing its inhabitants into ramshackle buildings further down the hill.[41][40] Nabi Samwil was drawn in good part within Jerusalem's municipal boundaries, while the inhabitants themselves were excluded, and its inhabitants were defined in their identity cards as West Bankers, and are prohibited by the Israeli military administration from leaving the village in any direction without authorisation.[41] Since the mid-2000s, Nabi Samwil, excluding the shrine, became part of an area known as the "Seam Zone", which denotes the land between the separation barrier erected during the Second Intifada, and the borders of Jerusalem municipality.[42] The only exit from the village is to nearby Bir Nabala via an Israeli checkpoint.[41][dead link]

The village, which is not recognized as such by Israel, was designated as a national park in the 1990s and the remains of former homes adjacent to the mosque form part of an archaeological site in the park. The mosque has been cordoned off and the section containing Samuel's tomb has been converted into a synagogue. Partly due to Israeli military restrictions, Palestinian construction in the village is banned. Economic activity is also significantly restricted and residents live in poverty, with many young residents leaving for jobs in nearby Ramallah. Israel states its policies are intended to preserve the site of Nabi Samwil.[42]

Demographics

In 1922, Nabi Samwil had 121 inhabitants,[30] rising to 138 in 1931.[31] In Sami Hadawi's land and population survey in 1945, 200 people resided there.[33] By 1981 the number dropped to 66 inhabitants but was up to 136 within five years.[6] According to the 2007 census by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Nabi Samwil had a population of 258 inhabitants in 2007.[43] About 20 Muslim families live there. A group of 90 Bedouins living in al Jib who had been evicted from Nabi Samwil were refused permission to move back because the village lies in Area C and it would be difficult for them to acquire building permits.[44]

References

- ^ a b Preliminary Results of the Population, Housing and Establishments Census, 2017 (PDF). Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) (Report). State of Palestine. February 2018. pp. 64–82. Retrieved 2023-10-24.

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 324

- ^ a b c "Nebi Samuel Park – Israel Nature and Parks Authority". en.parks.org.il. Archived from the original on 2022-03-12. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jacobs, Daniel. (1998). Israel and the Palestinian territories. Rough Guides, p.429.

- ^ Satellite View of al-Nabi Samwil

- ^ a b Welcome to al-Nabi Samwil Palestine Remembered.

- ^ Gleichen (1925), p. 8

- ^ I Mach., iii, 46, cited in Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Adler, Nathan Marcus (1907). The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela: Critical Text, Translation and Commentary. Vol. See "St. Samuel of Shiloh" and footnote 87. New York: Phillip Feldheim, Inc. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2020 – via washington.edu.

- ^ a b Nabi Samuel - Jerusalem Archived 2008-01-25 at the Wayback Machine Jerusalem Media and Communications Centre.

- ^ a b c d e Nebi Samwil - Site of a Biblical Town and a Crusader Fortress Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2001-09-01.

- ^ Al-Muqaddasi (Basil Anthony Collins (Translator)): The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the Regions. Ahasan al-Taqasim Fi Ma'rifat al-Aqalim. Garnet Publishing, Reading, 1994, ISBN 1-873938-14-4, p. 171, (orig. p.188). Older translation is given in Le Strange, 1890, p. 433

- ^ Le Strange, 1890, p. 433 (orig. Yak., iv. 391; Mar., iii.29)

- ^ a b Sharon, 2004, p. 118

- ^ Sharon, 2004, pp. 122 -123

- ^ "Travelling to Jerusalem--Benjamin of Tudela". depts.washington.edu.

- ^ "Summary Page: Palestine/Israel (Kingdom of Jerusalem)-St. Samuel". Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2010-02-14.

- ^ Sharon, 2004, p. 119

- ^ a b Mahmoud Yazbak, 'Holy shrines (maqamat) in modern Palestine/Israel and the politics of memory,' in Marshall J. Breger, Yitzhak Reiter, Leonard Hammer (eds.), Holy Places in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Confrontation and Co-existence, Routledge 2010 pp. 231-246 p.237.

- ^ "Mount Joy: the view from Palestine". January 21, 2014.

- ^ Sharon, 2004, pp. 119 -120.

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 113

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, Appendix 2, p. 121

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 2, pp. 139 -145

- ^ Socin, 1879, p. 158

- ^ Hartmann, 1883, p. 127, also noted 6 houses

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 12

- ^ Schick, 1896, p. 125

- ^ Jerusalem Won at Bayonet's Point New York Times. 1917-12-17.

- ^ a b Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jerusalem, p. 14

- ^ a b Mills, 1932, p. 41

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 25

- ^ a b Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 57

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 103

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 153

- ^ Tal, 2003, p. 118

- ^ Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics, 1964, p. 24

- ^ Abraham, Yuval (August 30, 2022). "Israel destroyed Palestinian village for luxury settlement that was never built". +972 Magazine.

- ^ "Nabi Samwil – A Village Trapped in a National Park". September 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Yitzhak Reiter (2017). Contested Holy Places in Israel-Palestine; Sharing and Conflict Resolution. Routledge. p. 272.

- ^ a b c 'Palestinian village imprisoned in holy shrine of Nabi Samuel,' Ma'an News Agency12 February 2015.

- ^ a b Tourist sites in the West Bank: Wish you were here?. The Economist. 2014-01-06.

- ^ Population, Housing and Establishment Census 2007 Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. 2008. Retrieved on 2012-02-29.

- ^ Protection of Civilians Weekly Report United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, p.7. January 2008.

Bibliography

- Adler, Marcus Nathan; of Tudela, Benjamin (1907). The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela, Critical Text, Translation And Commentary. London: Oxford University Press. p. 26

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. (pp. 149, 150)

- Dauphin, C. (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). Vol. III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4. (p. 893)

- Gleichen, E., ed. (1925). First List of Names in Palestine - Published for the Permanent Committee on Geographical Names by the Royal Geographical Society. London: Royal Geographical Society. OCLC 69392644.

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics (1964). First Census of Population and Housing. Volume I: Final Tables; General Characteristics of the Population (PDF).

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1868). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale. (pp. 362- 384)

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 3. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale. (pp. 4-5)

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Pringle, D. (1993). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: Volume I A-K (excluding Acre and Jerusalem). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39036-2. ( p. 283 )

- Pringle, D. (1998). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: Volume II L-Z (excluding Tyre). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39037-0. (p. 85 -)

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Sharon, M. (2004). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, D-F. Vol. 3. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-13197-3. (pp. 114 -134)

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Tal, D. (15 March 2003). War in Palestine, 1948: Strategy and diplomacy. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-5275-7.

- Tyrwhitt Drake, C.F (1872). "Mr Tyrwhitt Drake´s reports". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 4: 174–193. (p. 174, quoted in SWP)

External links

- Welcome To al-Nabi Samwil

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- An Nabi Samwil Village (Fact Sheet), Applied Research Institute–Jerusalem (ARIJ)

- An Nabi Samwil Village Profile, ARIJ

- An Nabi Samwil Aerial photo, ARIJ

- Locality Development Priorities and Needs in An Nabi Samwil, ARIJ

- Israel severs a-Nabi Samwil Village from rest of the West Bank, B'Tselem

- Battle of Nebi Samwil