Copia (museum)

| |

| Established | November 18, 2001 |

|---|---|

| Dissolved | December 2008 |

| Location | 500 First Street, Napa, California 94559 |

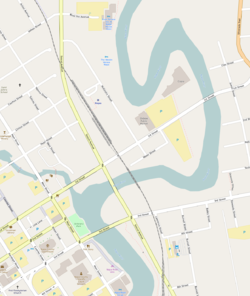

| Coordinates | 38°18′10″N 122°16′49″W / 38.302800°N 122.280314°W |

| Type | Specialized |

| Director | Peggy Loar (1997-2005) Arthur Jacobus (2005-2008) Garry McGuire Jr. (2008) |

| Website | www.copia.org at the Wayback Machine (archive index) |

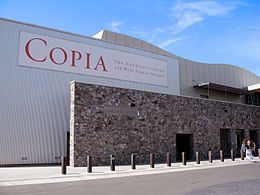

Copia: The American Center for Wine, Food & the Arts[a] was a non-profit museum and educational center in downtown Napa, California, dedicated to wine, food and the arts of American culture. The center, planned and largely funded by vintners Robert and Margrit Mondavi, was open from 2001 to 2008. The 78,632-square-foot (7,305.2 m2) museum had galleries, two theaters, classrooms, a demonstration kitchen, a restaurant, a rare book library, and a 3.5-acre (1.4 ha) vegetable and herb garden; there it hosted wine and food tasting programs, exhibitions, films, and concerts. The main and permanent exhibition of the museum, "Forks in the Road", explained the origins of cooking through to modern advances. The museum's establishment benefited the city of Napa and the development and gentrification of its downtown.

Copia hosted its opening celebration on November 18, 2001. Among other notable people, Julia Child helped fund the venture, which established a restaurant named Julia's Kitchen. Copia struggled to achieve its anticipated admissions, and had difficulty in repaying its debts. Proceeds from ticket sales, membership and donations attempted to support Copia's payoff of debt, educational programs and exhibitions, but eventually were not sufficient. After numerous changes to the museum to increase revenue, Copia closed on November 21, 2008. Its library was donated to Napa Valley College and its Julia Child cookware was sent to the National Museum of American History. The 12-acre (4.9 ha) property had been for sale since its closure; the Culinary Institute of America purchased the northern portion of the property in October 2015. The college opened its campus, the Culinary Institute of America at Copia, which houses the CIA's new Food Business School.

History

[edit]

Name

[edit]The original name for the museum was simply the American Center for Wine, Food and the Arts,[1] though before opening it was additionally named after Copia, the Roman goddess of wealth and plenty.[2] According to Joseph Spence in Polymetis (1755),[3] Copia is a name used to describe the goddess Abundantia in poetry, and was referred to as Bona Copia in Ovid's Metamorphoses.[4]

Background

[edit]The city of Napa has historically not received as many wine country tourists as the cities north of it. A $300 million flood management project around the turn of the 21st century to widen the Napa River and raise bridges prompted building developments. In the early 2000s, a large development was completed in the downtown area, as well as several hotels. Copia and the nearby Oxbow Public Market were two large developments also constructed around that time to increase tourist and media focus on the city of Napa.[5]

The museum opened in 2001, two months after the September 11 attacks. The museum's visitor attendance was much lower than what was projected; the museum partially attributed that to the depressed tourist economy stemming from the attacks.[6]

Conception and construction

[edit]

Site

[edit]From the late 1800s to around the 1990s, the Rossi-Massa-Vallerga Garden stood at Copia's site. At the time the site was constructed, it was part of Rancho Entre Napa, a large land grant given while California was a Mexican province. The site consisted of an Italian building complex and garden. The complex consisted of about eight structures—houses, wagon sheds, and a barn—arranged around a central space without any dominant building. The oldest of these dated to around 1880.[1]

The layout was unique within the city of Napa, and may have been unique within California. The site differentiated from most agricultural sites by facing away from the road, with no distinct difference between middle-class and workers' houses, in size, finishing, or location. Many of the buildings shared walls or were built abutting each other, and two of the houses were built over a single basement.[1]

Between 1872 and 1880, Giovanni and Antonio Rossi, cousins born in Italy, began operating a vegetable garden on the property.[1] Italian immigrant Giuseppe Vallerga later purchased the property and farmed it to supply his produce stand and delivery service.[7] Vegetable production ceased in 1957 upon his death.[1] His son, Joe Vallerga, later built a grocery store on part of the site,[7] and the Vallerga family continued to own the property until the 1990s.[1][b][8]

In 1996, the city of Napa's Cultural Heritage Commission published a staff report which described the site as being eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. The commission described the site as an "important part of the Italian presence and heritage in Napa County" and recognized the garden as an authentic representation of Italian landscape organization, a distinctive feature of the city's cultural landscape, and an influence on the city's agricultural development in the late 1800s and early 1900s.[1]

Redevelopment

[edit]In 1988, vintner Robert Mondavi, his wife Margrit Mondavi, and other members of the wine industry began to look into establishing an institution in Napa County to educate, promote, and celebrate American excellence and achievements in the culinary arts, visual arts, and winemaking. Three organizations supported the museum: the University of California at Davis, the Cornell University School of Hotel Administration, and the American Institute of Wine & Food. In 1993, Robert Mondavi bought and donated the land for Copia for $1.2 million ($2.53 million today[9]),[10] followed by a lead gift of $20 million ($42.2 million today[9]).[11] Mondavi chose the downtown Napa location with urging from his wife, who raised her children there.[12] James Polshek was hired by the foundation as the architect for the building in October 1994. Subsequently, the "Founding Seventy", supporters from Napa Valley and the surrounding Bay Area, made substantial donations. Initial financing for Copia was $55 million ($86 million today[9]), along with a $78 million ($134 million today[9]) bond prior to opening in 2001.[13]

When the organization purchased the property, it was an empty lot next to a tire store. Construction of the facility triggered the development of hotels, restaurants, and the food hall Oxbow Public Market in downtown Napa and its Oxbow District.[14][15] The museum began construction in 1999[16] and hosted opening celebrations on November 18, 2001.[2] In 2005, Copia sold 3.5 acres (1.4 ha) to Intrawest for construction of a Westin hotel.[5]

Decline and bankruptcy

[edit]Although the facility did attract visitors, local residents' support failed to reach the numbers expected by the founders.[17] Original projections of 300,000 admissions per year[18] were never met.[19] In October 2006, the museum announced plans to turn galleries into conference rooms, remove most of the museum's focus on art, and lay off 28 of its 85 employees (most of whom were security guards for the art gallery[20]). At the time, Copia had $68 million ($96.2 million today[9]) in debt. That year the museum also lowered its original adult admission fee of $12.50 to $5.[21] For three months in 2006, the museum admitted guests free of charge, and attendance and revenue increased. The museum also began hosting weddings and renting its space more frequently in order to raise revenue.[6] In 2007, the museum altered its theme significantly by removing its focus on food and art, and instead focusing solely on wine. It replaced some of its gardens with vineyards, changed its displays to focus more on the history and aspects of wine and viticulture, and decreased the restaurant's and programs' focus on food.[22]

In September 2008, Garry McGuire announced that 24 of 80 employees were being laid off and the days of operation would be reduced from 7 to 3 per week.[23] Attendance figures had never reached either original or updated projections, causing the facility to operate annually in the red since its opening. In November, he announced that the property would be sold due to unsustainable debt.[24] The museum closed on Friday, November 21, 2008.[25][26] The closure was without warning; visitors who had arrived for scheduled events found a paper notice at the entrance that the center was temporarily closed. The next days' events involving chef Andrew Carmellini and singer Joni Morris were also abruptly cancelled;[27] the museum later stated that it would reopen on December 1.[26] On that day, the organization (with $80 million ($113 million today[9]) in debt) filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. The federal bankruptcy court blocked a $2 million ($2.83 million today[9]) emergency loan with priority in security, leaving Copia with no funds to resume operations.[25]

Writing about the failure of the project, The New York Times and other newspapers suggested that Copia had failed to clearly define its focus. Potential tourists were left feeling unsure whether they were visiting a museum, a cooking school, or a promotional center for wine.[28][29]

Aftermath

[edit]Following the 2008 closing of Copia, a group of investors, developers, advocates, and vintners named the Coalition to Preserve Copia was formed to explore a plan to preserve the building and grounds.[30] Part of the group's plan included forming a Mello-Roos district with participation of local hotel properties to finance bonds to purchase the property, but their effort failed.[31][32] In May 2009 local developer George Altamura spoke about his interest in purchasing the property.[33] Other developers including the Culinary Institute of America also expressed an interest in acquiring the property. Copia's bond holder, ACA Financial Guaranty Corporation, listed the property for sale in October 2009.[32] Napa Valley College's upper valley campus became the home of the center's library of around 1,000 cookbooks. By late 2010, local chefs had revived the center's garden and the parking lot had become the location of a weekly farmer's market.[34] In 2011, the museum was reported to still maintain its original furnishings, with the gift store fully stocked and the restaurant still furnished.[35] In an April 2012 auction, most of the center's fixtures, furniture, equipment, wine collection (around 3,500 bottles), dinnerware, displays, artistic items, and antiquities were sold.[36]

After Copia's closure, the building had been used for a few meetings and events, including the Napa Valley Film Festival and BottleRock Napa Valley.[37][38] Triad Development arranged to buy the entire site in 2015 and planned mixed use with housing and retail.[39] The company planned to build up to 187 housing units, 30,000 square feet of retail space, and underground parking for 500 cars. The plan had later altered to only include purchase of the southern portion of the property.[40] In 2015, the Culinary Institute of America (CIA) put in motion plans to acquire a separate portion of Copia. The college opened a campus, the Culinary Institute of America at Copia, which houses the CIA's new Food Business School.[41] The school, which was outgrowing its St. Helena campus, acquired the northern portion of the property for $12.5 million in October 2015 (it was assessed for $21.3 million around 2013).[40] Among the CIA's first events there was 2016's Flavor! Napa Valley, a food and wine festival sponsored by local organizations.[42] The campus opened in late 2016, with its Chuck Williams Culinary Arts Museum opening in 2017. The museum will house about 4,000 items of Chuck Williams, including cookbooks, cookware, and appliances.[43]

Facilities

[edit]

Copia is located on First Street in downtown Napa, adjacent to the Oxbow Public Market.[40] The 12-acre (4.9 ha) property is surrounded by an oxbow of the Napa River.[2] The two-story building is 78,632 square feet (7,305.2 m2) in size,[44] and is primarily built from polished concrete, metal, and glass.[16] The city's farmers' market has been located in Copia's parking lot since 2004.[16]

It had a 13,000-square-foot (1,200 m2) gallery for art, history, and science exhibits. It also had a 280-seat indoor theater, a 500-seat outdoor theater, classrooms, an 80-seat demonstration kitchen, a rare book library, a wine-tasting area, a café (named American Market Cafe[45]), gift shop (named Cornucopia[35]), and 3.5 acres (1.4 ha) of landscaped edible gardens. The building's architect was Polshek Partnership Architects.[46] Julia's Kitchen was a restaurant inside the Copia building that focused on seasonal dishes and was named for honorary trustee Julia Child, who loaned part of her kitchen to the restaurant,[2][25] a wall of 49 pans, pots, fish molds, and other tools and objects. Within a year of the center's closing, the items were sent to the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History, where they are included in the Julia Child's kitchen exhibit, which up until that point was only missing that portion.[47] The restaurant had a 1,700-square-foot (160 m2) dining room (for 180 seats), an outdoor seating area (4,300 square feet (400 m2)) and a 2,500-square-foot (230 m2) kitchen.[48] The gardens had fruit orchards, a pavilion with a kitchen and large dining table, and a small vineyard with 60 vines and 30 different grape varieties.[2] The restaurant and café were both operated by local caterer Seasoned Elements,[12][49] and later Patina Restaurant Group.[45]

The main and permanent exhibition of the museum, called "Forks in the Road: Food, Wine and the American Table",[50] had displays explaining the origins of cooking through to modern advances, and included a significant portion about the history of American winemaking. The museum's opening art exhibition was called "Active Ingredients", and had new works related to food by eight notable artists.[2] Copia also had an annual exhibit and event called "Canstruction", which began in 2005. The event involved teams of architects, students, and designers creating sculptures from cans of food, which would later be donated to the Napa Valley Food Bank. The first year's donation consisted of 42,000 pounds of canned food.[16][51]

Employees and visitor admissions

[edit]The founding director, Peggy Loar, left Copia in March 2005, and was replaced by Arthur Jacobus that July;[16][52] in 2008 Jacobus was replaced by Chairman Garry McGuire Jr., who resigned on December 5, 2008.[25] The wine curator, Peter Marks, left around 2008 and was replaced with dean of wine studies Andrea Robinson.[53] Around 2008, McGuire hired celebrity chef Tyler Florence as dean of culinary studies. Florence oversaw the museum's food programs and Julia's Kitchen.[10]

Museum attendance was initially forecast at 300,000; to compare, the county had 4.5 million tourists in 2001.[54] 205,000 visitors attended in 2001,[16] 220,000 visitors attended in 2002, and 160,000 attended in 2003.[52] 150,000 visitors attended in 2007.[23]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Staff Report. City of Napa Cultural Heritage Commission. October 21, 1996 – via Napa County Historical Society.

- ^ a b c d e f Severson, Kim (November 15, 2001). "The table is Set / Napa's ambitious Copia, celebrating food, wine and the visual arts, opens this weekend". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco, California: Hearst Corporation. p. D-1. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Spence, Joseph (1755). Polymetis (2nd ed.). London, England: Robert and James Dodsley. p. 160. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ Publius Ovidius Naso (2012). The Metamorphoses. Simply Latin Books. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-4710-1561-8. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Shevory, Kristina (August 5, 2007). "The City of Napa, No Longer Willing to Be Left Behind". The New York Times. New York, New York. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ a b Courtney, Kevin (April 11, 2006). "Copia's new recipe for success". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ a b c Huffman, Jennifer (August 3, 2012). "Joe Vallerga, founder of local grocery stores, dies". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ a b Huffman, Jennifer (March 1, 2018). "Vallerga's Market closing after a 71-year-run in Napa". Napa Valley Register. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Franson, Paul (October 16, 2008). "Copia Struggles for Relevance". Wines & Vines. Wine Communications Group, Inc. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ Courtney, Kevin (November 12, 2001). "On the Napa Oxbow". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ a b Brown, Patricia Leigh (December 12, 2001). "A Temple Where Wine and Food Are the Deities". The New York Times. New York, New York. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- ^ Moskin, Julia (December 1, 2008). "Copia Files for Chapter 11". The New York Times. New York, New York. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ Yune, Howard (June 10, 2012). "Copia's children: Doomed wine center spurred high-end tourism in downtown Napa". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Hallock, Betty (July 8, 2009). "Writing a new chapter in Napa's rebirth". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Coit, Michael (October 20, 2006). "Napa food, wine center laying off 25 workers, selling 5 acres, turning art space into conference areas". The Press Democrat. Santa Rosa, California. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ Huffman, Jennifer (November 7, 2010). "Copia employees look back". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Fish, Tim (November 19, 2001). "Copia Opens Its Bounty to the Public". Wine Spectator. New York, New York. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ Dorgan, Marsha (May 9, 2012). "Commercial Business Offices Proposed for Copia". Napa Valley Patch. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ Heimoff, Steve (October 2006). "Copia Makes Cuts to Alleviate Debt". Wine Enthusiast Magazine. Mount Kisco, New York: Wine Enthusiast Companies. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ Courtney, Kevin (October 19, 2006). "Copia to sell land, cut jobs, refinance $68 million debt". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ Brown, Corie (May 30, 2007). "Changing the blend at Copia". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ a b Huffman, Jennifer (September 27, 2008). "Copia Lays Off Staff, Cutting Days Open". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Courtney, Kevin (November 14, 2008). "Copia looks to sell, but stay". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Moskin, Julia (December 23, 2008). "Napa Culinary Center, in Debt, Forced to Close". The New York Times. New York, New York. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ a b Huffman, Jennifer (November 25, 2008). "Copia closes through Thanksgiving, maybe longer". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ Carson, L. Pierce; Pailsen, Sasha (November 23, 2008). "Copia closes without warning". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ Price, Catherine (December 2, 2008). "Copia, a Food and Wine Center, Files for Bankruptcy". The New York Times. New York, New York. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ Fish, Tim (October 18, 2006). "Copia Undergoing Another Overhaul". Wine Spectator. New York, New York. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ Huffman, Jennifer (April 25, 2009). "Salmon, Price explore the revitalization of wine center site". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Huffman, Jennifer (June 7, 2009). "Hotel users may be key to revival of Copia". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ a b Huffman, Jennifer (October 3, 2009). "Copia officially up for sale". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Huffman, Jennifer (May 30, 2009). "Altamura interested in Copia". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Huffman, Jennifer (November 7, 2010). "Copia two years later". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ a b Huffman, Jennifer (November 8, 2011). "Copia's interior sits frozen in time". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ Davis, Kip (April 22, 2012). "Curtain closes on Copia liquidation auction". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Huffman, Jennifer (September 5, 2011). "Copia to reopen for film festival". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ Huffman, Jennifer (July 30, 2013). "Copia reuse plan in jeopardy, developer warns". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Woodard, Richard (March 19, 2015). "Napa: Copia wine centre sold to development firm". Decanter. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c Huffman, Jennifer (October 30, 2015). "CIA buys long-vacant Copia for food offerings". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ Huffman, Jennifer (July 2, 2015). "Culinary Institute offers new life to vacant Copia building". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Paulsen, Sasha (March 21, 2016). "Taste of the Valley: Flavor!, Beefsteak and the CIA in Napa". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ Fritsche, Sarah (January 11, 2016). "Museum honoring Williams-Sonoma founder heading to CIA at Copia". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco, California: Hearst Corporation. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ Paolo (October 2, 2009). "Now on the Market: Copia and Julia's Kitchen". Eater. Washington, D.C.: Vox Media. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ a b "Duo reunites in Wine Country". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco, California: Hearst Corporation. October 25, 2006. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ Polshek Partnership Architects. New York, New York: Princeton Architectural Press. 2005. p. 194. ISBN 1-56898-428-6. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- ^ Marchetti, Domenica (August 13, 2009). "Revisiting Julia Child's Kitchen at the National Museum of American History". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C.: Nash Holdings. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ Lucchesi, Paolo (August 16, 2012). "On the future of Copia and Julia's Kitchen". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco, California: Hearst Corporation. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ Virbila, S. Irene (February 10, 2002). "Julia's Kitchen-In Name Only". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- ^ Fullwood, Janet (November 11, 2001). "Celebrating the senses -- Copia: The American Center for Wine, Food & the Arts makes a smashing debut in Napa". The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, California. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- ^ Paulsen, Sasha (October 15, 2006). "Art cans hunger". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Ryan, David (March 17, 2005). "Peggy Loar resigns as president of Copia". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ "Copia's New Chief Emphasizes Content Creation". Wine Business Insider. Wine Communications Group. March 31, 2008. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Leibowitz, Elissa (November 17, 2002). "Napa Vs. Sonoma". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C.: Nash Holdings. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

External links

[edit]- Copia: The American Center for Wine, Food & the Arts at the Wayback Machine (archived February 3, 2008)

- Buildings and structures in Napa County, California

- Companies based in Napa County, California

- Companies that filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2008

- Defunct companies based in California

- Defunct museums in California

- Food museums in the United States

- The Culinary Institute of America

- Wine industry organizations