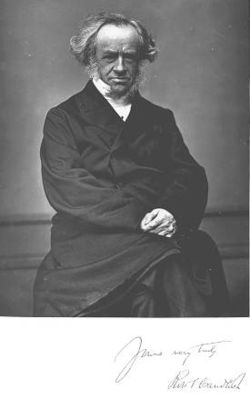

Robert Smith Candlish

Robert Smith Candlish (23 March 1806 – 19 October 1873) was a Scottish minister who was a leading figure in the Disruption of 1843.[1] He served for many years in both St. George's Church and St George's Free Church on Charlotte Square in Edinburgh's New Town.

Life

[edit]He was born at 11 West Richmond Street[2] in Edinburgh, the son of James Candlish (originally McCandlish, 1759-1806),[3] a lecturer in medicine and friend of Robert Burns. James died soon after Robert was born. He and his siblings were raised by his mother, Jane Smith (1768–1854).[4] She moved to Glasgow soon after her husband's death and survived by running a boarding house at 49 Virginia Street.[5]

In 1820, he began studying divinity at Glasgow University, where he graduated in 1823. During the years 1823–1826 he went through the prescribed course at the divinity hall, then presided over by Rev Dr Stevenson McGill.[6] On leaving, he accompanied a pupil as private tutor to Eton College, where he stayed two years.[7][8]

In 1829, Candlish entered upon his life's work, having been licensed to preach during the summer vacation of the previous year. After short assistant pastorates at St Andrew's Church, Glasgow, and then the parish church of Bonhill in Dunbartonshire, he became assistant minister to Rev James Martin of St George's, Edinburgh.[9] He attracted the attention of his audience by his intellectual keenness, emotional fervour, spiritual insight and power of dramatic representation of character and life. His theology was that of the Scottish Calvinistic school, and he gathered round him one of the largest congregations in the city.[8]

In 1840, he was living at 9 Randolph Crescent in Edinburgh's West End, a huge terraced townhouse.[10]

Candlish took an interest in ecclesiastical questions, and he soon became involved in the struggle which was then agitating the Church of Scotland. His first Assembly speech, delivered in 1839, placed him among the leaders of the party that afterwards formed the Free Church, and his influence in bringing about the Disruption of 1843 was inferior only to that of Thomas Chalmers. He took his stand on two principles: the right of the people to choose their ministers, and the independence of the church in things spiritual. On his advice, Hugh Miller was appointed editor of the Witness[8] and Miller wrote much of the weekly copy.[11]

Following the Disruption, Candlish was one of the Free Churchmen who spoke in England, explaining the reason why so many had left the Established Church.[12] He was actively engaged at one time or other in nearly all the various schemes of the church, but particularly the education committee, of which he was convener from 1846 to 1863, and in the unsuccessful negotiations for union among the non-established Presbyterian denominations of Scotland, which were carried on during the years 1863–1873.[8][13] Candlish was the Free Church Moderator at the Assembly of 1867. He was succeeded in 1868 by Rev William Nixon.[14]

In 1841, the government nominated Candlish to the newly founded chair of Biblical criticism in the University of Edinburgh.[15] However, owing to the opposition of Lord Aberdeen,[16][17] the presentation was cancelled. In 1847 Candlish, who had received the degree of D.D. from Princeton, New Jersey, in 1841, was chosen by the Assembly of the Free Church to succeed Chalmers in the chair of divinity in the New College, Edinburgh. After partially fulfilling the duties of the office for one session, he was led to resume the charge of St George's, the clergyman who had been chosen by the congregation as his successor having died before entering on his work.[8]

In 1851, he established a Gaelic Church on Cambridge Street.[18] In 1862 he succeeded William Cunningham as principal of New College with the understanding that he should still retain his position as minister of St George's.[8]

Death

[edit]

Candlish died at home, 52 Melville Street[19] in Edinburgh in 1873.

As the Free Church lost the right to burial in the traditional parish burial grounds, Candlish is buried in the non-denominational Old Calton Burial Ground. He lies in the southern extension, just south-east of the Martyr's Monument.

Family

[edit]He married 6 January 1835, Jessie (died 16 September 1894), daughter of Walter Brock and Janet Crawford, and had issue —

- James Smith Candlish, D.D., minister at Logie-Almond and Aberdeen, Professor in Free Church College, Glasgow, 1872–97, born 14 December 1835, died 7 March 1897

- Jessie, born 14 January 1837, died 29 January 1893 (married 1865, William Anderson of Glentarkie)

- Jane Smith, born 14 June 1838, died 30 March 1840

- Walter, born 10 August 1839, died 20 February 1840

- Elizabeth Smith, born 28 December 1840 (married 1863, Archibald Henderson, D.D., United Free Church min. at Crieff)

- Agnes, born 3 August 1842, died 24 April 1845

- Robert Smith, marine engineer, born 21 April 1844, died 20 May 1887

- Margaret Charlotte, born 28 January 1846, died 16 April 1899

- John Bogle, insurance agent, Australia, born 2 November 1847

- Mary Ross, born 9 June 1851, died 30 September 1866.[20]

Several of their children died in childhood.[21]

Works

[edit]Candlish made a number of contributions to theological literature. In 1842 he published the first volume of his Contributions towards the Exposition of the Book of Genesis, a work which was completed in three volumes several years later. In 1854 he delivered, in Exeter Hall, London, a lecture on the Theological Essays of the Rev. F. D. Maurice, which he afterwards published, along with a fuller examination of the doctrine of the essays. In this he defended the forensic aspect of the gospel. A treatise entitled The Atonement; its Reality, Completeness and Extent (1861) was based upon a smaller work which first appeared in 1845. In 1864 he delivered the first series of Cunningham lectures, taking for his subject The Fatherhood of God. Published immediately afterwards, the lectures excited considerable discussion on account of the peculiar views they represented. Further illustrations of these views were given in two works published about the same time as the lectures, one a treatise On the Sonship and Brotherhood of Believers, and the other an exposition of the first epistle of St John.[8]

- Eleven single Sermons (Edinburgh, 1834, et seq.)

- Contributions towards the Exposition of the Book of Genesis, 3 vols. (Edinburgh, 1842–52)

- The Word of God the Instrument of the Propagation of the Gospel (1843)

- Scripture Characters and Miscellanies (Edinburgh, 1850)

- Reason and Revelation (Edinburgh, 1854)

- Man's Right to the Sabbath (Edinburgh, 1856)

- Life in a Risen Saviour (Edinburgh, 1858)

- The Atonement (Edinburgh, 1860)

- Two Great Commandments (Edinburgh, 1860)

- The Fatherhood of God (Edinburgh, 1865)

- Sermons, memoir (Edinburgh, 1874)

- Discourses on the Ephesians (Edinburgh, 1875)

- numerous pamphlets, etc.[20]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Wylie 1881.

- ^ Edinburgh Post Office Directory 1805/6

- ^ Lindsay, Maurice (2002) [1959]. "Candlish, James (1759–1806)". The Burns Encyclopedia (3rd (online) ed.). Retrieved 5 September 2023 – via RobertBurns.org.

- ^ Inscription on grave of Rev Robert Candlish

- ^ Glasgow Post Office Directory 1816

- ^ Wilson 1880.

- ^ Bayne 1893, p. 146.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Walker, Norman L (1895). Chapters from the history of the Free church of Scotland. Edinburgh; London: Oliphant, Anderson & Ferrier. p. 21. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Edinburgh and Leith Post Office Directory 1840-41

- ^ Bayne 1893, p. 136.

- ^ Brown, Thomas (1883). Annals of the disruption. Edinburgh: Macniven & Wallace. pp. 525–526. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ Walker, Norman L (1895). Chapters from the history of the Free church of Scotland. Edinburgh; London: Oliphant, Anderson & Ferrier. pp. 226–270. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Ewing, William Annals of the Free Church

- ^ Walker, Norman L (1895). Chapters from the history of the Free church of Scotland. Edinburgh; London: Oliphant, Anderson & Ferrier. pp. 101–102. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Hansard, House of Lords 22 March 1841.

- ^ Hansard, House of Lords 29 April 1841.

- ^ By The Three Great Roads, ISBN 0-08-036587-6

- ^ Edinburgh Post Office Directory 1873

- ^ a b Scott 1915.

- ^ Inscription on grave of Robert Candlish

Sources

[edit]- Bayne, Peter (1893). The Free Church of Scotland : her origin, founders and testimony. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. pp. 127 et sequim.

- Beith, Alexander (1874). A Highland tour with Dr. Candlish (2 ed.). Edinburgh: A. and C. Black. p. 9-10.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Blaikie, William Garden (1886). "Candlish, Robert Smith". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 8. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Brown, Thomas (1883). Annals of the disruption. Edinburgh: Macniven & Wallace. p. 787 et passim.

- Buchanan, Robert (1854a). The ten years' conflict : being the history of the disruption of the Church of Scotland. Vol. 1. Glasgow ; Edinburgh ; London ; New York: Blackie and Son.

- Buchanan, Robert (1854b). The ten years' conflict : being the history of the disruption of the Church of Scotland. Vol. 2. Glasgow ; Edinburgh ; London ; New York: Blackie and Son.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Candlish, Robert Smith". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 180.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Gordon, Robert; Buchan, George; Candlish, Robert Smith (1839). Report of the speeches of ... Dr. Gordon, Mr. Buchan of Kelloe, and Rev. R. S. Candlish, in the Commission of the General Assembly, ... August 14, 1839, on the Auchterarder case. Revised by the Speakers. Edinburgh: John Johnstone.

- McMullen, Michael D. (2004). "Candlish, Robert Smith". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4547. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Scott, Hew (1915). Fasti ecclesiae scoticanae; the succession of ministers in the Church of Scotland from the reformation. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. p. 106.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Scott, Hew (1920). Fasti ecclesiae scoticanae; the succession of ministers in the Church of Scotland from the reformation. Vol. 3. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. p. 332.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Smith, John (1853). Our Scottish clergy : fifty-two sketches, biographical, theological, & critical, including clergymen of all denominations. Edinburgh : Oliver & Boyd ; London : Simpkin, Marshall ; Glasgow : A. Smith. pp. 113-119.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Wilson, William, minister of St. Paul's Free Church, Dundee (1880). Memorials of Robert Smith Candlish, D.D. : minister of St. George's Free Church, and principal of the New College, Edinburgh with a chapter on his position as a theologian by Robert Rainy. Edinburgh: A. and C. Black. pp. 11–12.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wylie, James Aitken, ed. (1881). Disruption worthies : a memorial of 1843, with an historical sketch of the free church of Scotland from 1843 down to the present time. Edinburgh: T. C. Jack. pp. 139–145.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

External links

[edit]- Robert Smith Candlish This site includes a biography of Candlish, several literature works by Candlish and some letters written by Candlish. It is one of several sites in the related Scottish Preachers' Hall of Fame.

- [1] various photographs from the National Portrait Gallery

- Works by Robert Smith Candlish at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by or about Robert Smith Candlish at the Internet Archive

- 1806 births

- 1873 deaths

- Clergy from Edinburgh

- Scottish Calvinist and Reformed theologians

- 19th-century Ministers of the Free Church of Scotland

- 19th-century Scottish Presbyterian ministers

- Burials at Old Calton Burial Ground

- 19th-century Calvinist and Reformed theologians

- Alumni of the University of Glasgow

- Academics of the University of Edinburgh