Madvillainy

| Madvillainy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | March 23, 2004 | |||

| Recorded | 2002–2004 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 46:08 | |||

| Label | Stones Throw | |||

| Producer | ||||

| Madvillain chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Madlib chronology | ||||

| ||||

| MF Doom chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Instrumental release | ||||

Madvillainy Instrumentals | ||||

| Singles from Madvillainy | ||||

| ||||

Madvillainy is the only studio album by American hip hop duo Madvillain, consisting of British-American rapper MF Doom and American record producer Madlib. It was released on March 23, 2004, on Stones Throw Records.

The album was recorded between 2002 and 2004. Madlib created most of the instrumentals during a trip to Brazil in his hotel room using minimal amounts of equipment: a Boss SP-303 sampler, a turntable, and a tape deck.[1] Fourteen months before the album was released, an unfinished demo version was stolen and leaked onto the internet. Frustrated, the duo stopped working on the album and returned to it only after they had released other solo projects.

While Madvillainy achieved only moderate commercial success, it became one of the best-selling Stones Throw albums. It peaked at number 179 on the US Billboard 200, and attracted attention from media outlets not usually covering hip hop music, including The New Yorker. Madvillainy received widespread critical acclaim for Madlib's production and MF Doom's lyricism, and is regarded as Doom's magnum opus.[2] It has since been widely regarded as one of the greatest hip hop albums of all time, as well as one of the greatest albums of all time in general, being ranked in various publications' lists of all-time greatest albums, including at 411 on NME's list of The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time,[3] at 365 on Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time,[4] and at 18 on Rolling Stone's 200 Greatest Hip-Hop Albums of All Time.[5]

Background

[edit]In 1997, after the death of his brother DJ Subroc and the rejection of KMD's album Black Bastards by Elektra Records four years previously, rapper Daniel Dumile (formerly known as Zev Love X) returned to music as the masked rapper MF Doom.[6] In 1999, Doom released his debut solo album Operation: Doomsday on Fondle 'Em Records.[7] According to Nathan Rabin of The A.V. Club, the album "has attained mythic status; its legend has grown in proportion to its relative unavailability".[8] Soon after release of the album, in an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Madlib stated that he wanted to collaborate with two artists: J Dilla and Doom.[9]

In 2001, after Fondle 'Em closed, Doom disappeared. During that time, he lived between Long Island, New York, and Kennesaw, a suburb of Atlanta, Georgia. Coincidentally, Eothen "Egon" Alapatt, who was the manager of Madlib's label Stones Throw Records, had a friend in Kennesaw. He asked the friend to give Doom (who did not know about Madlib and Stones Throw at the time) some instrumentals from Madlib. Three weeks later, the friend called back, telling him that Doom loved the instrumentals and wanted to work with Madlib. Soon, one of Doom's "quasi-managers" made an offer, asking for plane tickets to Los Angeles and $1,500. Despite the fact that the label didn't have enough money after buying the tickets, they immediately agreed. According to Egon, soon after arrival, the manager went to him demanding money, while Doom visited Madlib:[9]

The first thing his manager did was get me in my bedroom, which was also the office, and corner me about the 1,500 bucks. I realized that if she was in here, then Doom was with [Madlib], and the longer I kept up this charade with her, the longer they'll vibe and maybe it all might work out.

Egon's plan was successful, and Doom and Madlib began working together. Soon after, Stones Throw Records managed to collect the money necessary to pay Doom and a contract to the label was signed, which was written on a paper plate.[9]

Recording

[edit]Doom and Madlib started working on Madvillainy in 2002. Madlib created one hundred beats in a matter of weeks, some of which were used on Madvillainy, some were used on his collaboration album with J Dilla Champion Sound, while others were used for M.E.D.'s and Dudley Perkins' albums. Even though Stones Throw booked Doom a hotel room, he spent most of the time in Madlib's studio, based in an old bomb shelter in Mount Washington, Los Angeles. When the duo was not working on the album, they were spending free time together, drinking beer, eating Thai food, smoking marijuana,[9] and taking psychedelic mushrooms.[10] "Figaro" and "Meat Grinder" were among the songs recorded during this time.[11]

In November 2002, Madlib went to Brazil to participate in a Red Bull Music Academy lecture,[12] where he debuted the first music from the album by playing an unfinished version of "America's Most Blunted".[13] Madlib also went crate digging during his time in Brazil, searching for obscure vinyl records he could sample later, with fellow producers Cut Chemist, DJ Babu, and J.Rocc.[14][15] According to Madlib himself, he bought multiple crates full of vinyl records, two of which he later lost.[14] He used some of these records to produce beats for Madvillainy. Most of the album,[14] including beats for "Strange Ways", "Raid", and "Rhinestone Cowboy", was produced in his hotel room in São Paulo, using a portable turntable, a cassette deck, and a Boss SP-303 sampler.[9] While Madlib was working on the album in Brazil, the unfinished demo was stolen and leaked on the internet, 14 months before its official release. Jeff Jank, Stones Throw's art director, remembers the leak in the interview with Pitchfork:[9]

Those were the early days of internet leaks, and we thought it would completely ruin sales. People were approaching Doom and Madlib at shows to tell them how much they liked the album, so they were like, 'Fuck it, I'm done.' Madlib started on other stuff, and Doom, well, you never know what he's doing.

Doom and Madlib decided to work on different projects. Madlib released Champion Sound with J Dilla, while Doom released two solo albums: Take Me to Your Leader, as King Geedorah, and Vaudeville Villain, as Viktor Vaughn. Nevertheless, after the release of these albums, they decided to return to Madvillainy. For the final version of the album, Doom altered his voice, described by Peanut Butter Wolf as going from "really hyper, more enthusiastic" to "a more mellow, relaxed, confident, less abrasive", and changed some lyrics to coincide with this change. Madlib was also asked by the label to change some instrumentals, but told them that he forgot the samples he used, in order to allow for them to remain on the album. Additionally, the label also requested the duo make a proper ending for the album, forcing them to rent a studio for the recording of "Rhinestone Cowboy".[9] The beat used, however, was produced in Brazil.[16]

Production

[edit]

Madvillainy was produced almost entirely by Madlib, except the first track, which he produced in collaboration with Doom.[17] On the album, Madlib incorporates his distinctive production style, based on using samples,[18] mostly obscure, from albums recorded in different countries.[19] Aside from sampling records by American artists,[20] namely from jazz[21] and soul,[22] Madlib also used Indian (for example, "Shadows of Tomorrow" samples "Hindu Hoon Main Na Musalman Hoon" by R. D. Burman) and Brazilian records ("Curls" samples "Airport Love Theme" by Waldir Calmon) for Madvillainy.[13] In regards to Madlib's production on the album, he stated in an interview:

I did most of the Madvillain album in Brazil. Cuts like "Raid" I did in my hotel room in Brazil on a portable turntable, my 303, and a little tape deck. I recorded it on tape, came back here, put it on CD, and Doom made a song out of it.[1]

The album consists of 22 songs,[17] most of which are under 3 minutes and contain no hooks or choruses.[13][22] Sam Samuelson of AllMusic compared the album to a comic book, "sometimes segued with vignettes sampled from 1940s movies and broadcasts or left-field [marijuana]-toting skits". He also noted that some instrumentals on the album "[seem] to be so out of time or step with a traditional hip-hop direction".[23] The A.V. Club compared the album to a buffet, where "Madlib and Doom are interested in throwing out ideas as fast as they have them, giving them as much attention as they need, and moving on to the next thing".[13] Tim O'Neil of PopMatters praised Madlib's instrumentals and said that they "make the album a sonic feast".[21]

Lyrics

[edit]Doom's lyrics on Madvillainy are free-associative.[25] According to Stereogum, the album "is about using sound to craft semi-indecipherable vignettes that are situated somewhere between the real and the mythical".[22] Despite originally featuring a more enthusiastic, excited delivery, the leak prompted Doom to go with a slower and more relaxed flow on the final version of the album. This move has been praised by various publications, including Pitchfork, which said that it was "ultimately better-suited" than the original.[12]

Throughout the album, Doom uses a number of literary devices, including multisyllabic rhymes, internal rhymes, alliteration,[26] assonance,[27] and holorimes.[28] Music critics also noted extensive use of wordplay[13] and double entendres.[29] PopMatters wrote, "You can spend hours poring over the lyric sheet and attempting to grok Doom's infinitely dense verbiage. If language is arbitrary, then many of Doom's verses exploit the essence of words stripped of meaning, random conglomerations of syllables assembled in an order that only makes sense from a rhythmical standpoint", the critic added.[21] The Observer stated that "the densely telegraphic lyrics almost always reward closer inspection" and that Doom's "rhymes miss beats, drop into the middle of the next line, work their way through whole verses" allowing for a smooth listen.[30]

Artwork

[edit]The album cover art was created by Stones Throw's art director Jeff Jank, based on a grayscale photo of Doom in his metal mask. In an interview with Ego Trip, Jank said:[31]

Back then, 2003, Doom didn't really have public image. Hip hop heads knew he wore a mask, that he'd been in KMD a decade earlier, but he really was a mystery. So, I really wanted to get a shot of him on the cover, just to make a definitive 'Doom cover'. Specifically, I was thinking of a picture of this man, who happened to wear a mask for some reason, as opposed to 'a picture of a mask'. I don't know if the distinction would occur to anyone else, but to me it was a big deal. I mean, who the hell goes around with a metal mask, what's his story?

The photo was created by photographer Eric Coleman at Stones Throw's house in Los Angeles, and edited by Jank. While working on the Madvillainy album cover, Jank drew inspiration from King Crimson's In the Court of the Crimson King artwork. However, following its completion, he noticed the artwork eerily resembled Madonna's Madonna artwork. Despite this, Jank stuck with the original artwork, labeling it as the "rap version of Beauty and the Beast". A small orange square was added to the final version of Madvillainy, due to Jank's thinking that the artwork "needed something distinctive", comparing it to the orange "O" on the Madonna cover.[31]

Release and promotion

[edit]Two singles from Madvillainy were released before the album release: "Money Folder" bundled with "America's Most Blunted",[32] and "All Caps" bundled with "Curls".[33] The first single peaked at number 66 on the Billboard Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart.[34] Madvillainy was released on March 23, 2004.[35] Despite Stones Throw Records being a relatively small label, the album achieved moderate commercial success, which was big for the label. According to Pitchfork, "after two years of hectoring Stones Throw for making unsalable records, distributor EMI couldn't keep Madvillainy in stock."[9] The album peaked at number 179 on Billboard 200[36] and sold approximately 150,000 copies,[9] making it one of the label's best-selling albums.[37] Its success allowed Stones Throw to open an office in Highland Park, Los Angeles.[9]

Four official videos were created for the album upon its initial release : "All Caps" (directed by James Reitano), "Rhinestone Cowboy" and "Accordion" (both directed by Andrew Gura),[17] and "Shadows of Tomorrow" (directed by System D-128). "All Caps" and "Rhinestone Cowboy" appear on the DVD Stones Throw 101[38] along with a hidden easter egg video for "Shadows Of Tomorrow" as a special bonus feature. An impromptu video for "Accordion" was filmed in 2004 but was not released until 2008's In Living the True Gods DVD.[39]

An instrumental version of the album was released in 2004 only in vinyl format and digitally through various online stores, with the tracks "The Illest Villains", "Bistro", "Sickfit", "Do Not Fire!", and "Supervillain Theme" being omitted. It was re-released in 2012 on vinyl with picture sleeve.[40]

In 2014, in honor of the 10th anniversary of Madvillainy, Stones Throw released a special edition of the album on vinyl.[41] The album re-entered Billboard 200 chart, peaking at number 117,[42] higher than it did originally. The same year Madvillainy was also released on Compact Cassettes, as part of the Cassette Store Day.[43]

Remixes

[edit]Several remixes of the album were released.[17] Two remix EPs of Madvillainy were released on Stones Throw in 2005.[44] The remixes were done by Four Tet and Koushik.[17] Madvillainy 2: The Madlib Remix was released on Stones Throw in 2008, containing a complete remix of the album by Madlib as a part of a Madvillain box set.[45] According to Stereogum, it was Madlib's "attempt to get Doom excited enough to work on a true follow-up",[22] recorded after he got tired of waiting for Doom to record the official sequel.[46]

Critical reception

[edit]| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 93/100[47] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Alternative Press | 5/5[48] |

| Entertainment Weekly | B[49] |

| Mojo | |

| The Observer | |

| Pitchfork | 9.4/10[12] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Slant Magazine | |

| The Village Voice | A−[54] |

Madvillainy was met with widespread critical acclaim from music critics and became one of the most critically acclaimed projects of both artists.[55] At Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, the album received an average score of 93, based on 20 reviews; it was the year's best-reviewed rap album and third highest reviewed album overall, according to the website. It also was the second most acclaimed rap album at the time of its release, behind Outkast's Stankonia.[47] Sam Samuelson of AllMusic wrote that album's strength "lies in its mix between seemingly obtuse beats, samples, MCing, and some straight-up hip-hop bumping" and that "MF Doom's unpredictable lyrical style fits quite nicely within Madlib's unconventional beat orchestrations".[23] Will Hermes of Entertainment Weekly called it "indie rap blowing session by two guys near the top of their game".[49] Alternative Press praised Madvillainy as "all invention and no indulgence",[48] while HipHopDX dubbed it an "experimental, eclectic, raw, spontaneous" classic.[24] Mojo praised the album, calling it "a symphony of such densely constructed chaos" and noting that "Madvillainy's very opacity is part of its brilliance".[50]

Pitchfork called Madvillainy "inexhaustibly brilliant, with layer-upon-layer of carefully considered yet immediate hip-hop, forward-thinking but always close to its roots", noting that "the samples are smart and never played-out, and the production and rhymes reveal a determined sense of cooperation, as MF Doom spouts off his most brilliant lyrical change-ups and production-conscious playoffs".[12] Q called Madlib "the most innovative beatsman since Prince Paul", who created "an oddball, cartoon-heavy backdrop for MF Doom's mellifluous wordplay".[51] Rolling Stone described Madlib's tracks as, "fuzzy and crackling with dust", and praised MF Doom, whose flow was commended as "a particularly elegant slur, with syllables spreading over a beat, not crisply adhering to it".[52] Eric Henderson of Slant Magazine called it "a chameleonic masterpiece that alone validates the artistry of sampler culture".[53] Robert Christgau, writing for The Village Voice, praised the album as "a glorious phantasmagoria of flow".[54] Blender's Jody Rosen called it a "torrid album that marries old-school rap aesthetics to punk-rock concision."[56]

Madvillainy also attracted positive reviews from several publications with infrequent coverage of hip hop music.[57] David Segal of The Washington Post called the album "hysterical, [...] perplexing, arresting, thought-provoking or just plain silly".[58] Kelefa Sanneh of The New York Times called it "a delirious collaboration" and hailed MF Doom as a rapper who "understands the deformative power of rhyme" and "delivers long, free-associative verses full of sideways leaps and unexpected twists".[59] Sasha Frere-Jones of The New Yorker praised the album, noting that "the point of Madvillainy is largely poetic—celebrating the language of music and the music of language" and that while the album's beats are based on samples of records, it's "hard to say which ones, even in a general way".[26]

Accolades

[edit]Several publications included Madvillainy in their lists of the best albums of the year. Pitchfork ranked it number six on their list of the 50 best albums of 2004, stating that "the collaboration brings out the best in both men, without copying anything in their catalogs".[60] Prefix ranked the album first on its list of the 60 best albums of 2004, stating that "when Doom and Madlib combine, they form like Voltron".[61] PopMatters positioned it at number nine on their list of the 100 best albums of 2004, commending MF Doom's "royal, pop culture-laden flow" and Madlib's "beat-mining expertise".[62] Spin ranked it number 17 on their list of the 40 best albums of 2004, praising Madlib's production, "thick, woozy slabs of beatnik bass", that "keeps things hotter than an underground volcano lair".[63] Washington City Paper ranked Madvillainy number one on their list of the top 20 albums of 2004. Stylus Magazine named it the second best album of 2004.[64] In The Village Voice's annual poll Pazz & Jop, which combined votes from 793 critics, Madvillainy was ranked number 11 on the list of the best albums of 2004.[65] The Wire[66] and AllMusic[67] also included the album in their unordered lists of the best albums of the year.

Numerous publications included Madvillainy in various lists of the best albums. Clash positioned it at number 47 in their list of top 100 albums of Clash's lifetime, calling it "slapdash and dilapidated, wholly unconcerned with making sense", "defined by its flippancy and attitude to professionalism".[68] The magazine also listed it on their list of ten best hip hop albums ever, calling it "one of this decade's finest hip-hop albums" that "elevated the profile of both [artists] to whole new levels".[69] Complex placed the album in their list of 100 best albums available on Spotify, calling it "dusty, weeded up, 22-song masterpiece that stood alone and brought us all into its own little world" and stating that "Madlib and MF Doom's classic wasn't meant for the radio, but it was too good to be kept to the underground".[70] The magazine also listed it among 25 albums of the decade that deserve classic status, describing it as "a classic record that had a goofy cartoony unpredictability, balanced with moments of oddball sincerity" and 71st on the list "The 100 Best Albums of the Complex Decade".[71][72] HipHopGoldenAge ranked it first in their list of the Top 150 Hip Hop Albums of the Decade, calling it "a perfect example of what can happen if two left-field geniuses combine powers."[73]The A.V. Club featured the album on the list "The Best Music of the Decade", referring to the album as "an instant masterpiece".[74] Fact ranked it number 14 at their list of 100 best albums of the 2000s and praised it as "a perfect synergy between raw beats and incredible rhymes".[75] The magazine also named it the second best album on their list of 100 best indie hip hop records ever made, stating that it was "arguably the signature moment from the signature rapper and signature producer of the entire movement".[76] Heavy.com ranked the album number 9 on their list "The Top 10 Hip-Hop Albums of the Decade", stating that "MF Doom has never sounded better than he did when he teamed up with Madlib for this little ditty of WTF hip hop".[77] Slant Magazine placed the album at number 39 on the list "The 100 Best Albums of the Aughts", calling it the "undisputed pinnacle of aughts underground rap".[78] Stylus Magazine ranked the album number 13 on its list "The Top 50 Albums: 2000-2004".[79] Fact ranked the album 14th on its "The 100 Best Albums of the 2000s" list, praising it as "a perfect synergy between raw beats and incredible rhymes that in the minds and hearts of many, neither party has yet to surpass".[80] The Guardian included the album in their list of 1000 albums to hear before you die, describing it as "a colourful window into Dumile's world", while praising its "busy unpredictability and stoned comic-book mythos".[81] HipHopDX included the album in two lists: top 10 albums of 2000s[82] and the 30 best underground hip hop albums since 2000, describing it as "the super rap album, reaching unforeseen creative heights" that "elevated [Doom and Madlib] into Gods for many core Hip Hop heads".[83] Rolling Stone featured it on their list of 40 one album wonders,[84] and in 2020, ranked the album at number 365 in their revised list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[85]

NME ranked the album number 411 on their list of the 500 greatest albums of all time, describing it as "stoner humour and mind-bending beats from a hip-hop dream team" and stating that "MF Doom and Madlib might not have invented underground rap, but they damn well perfected it".[86] Pitchfork ranked the album at number 13 in their list of the top 100 albums of 2000–2004, commenting, "While Madlib's special power played tricks on your ears – a sample you were sure was the sound of cars rolling by on the street might sound like the hiss of a record on a different day ("Rainbows") – MF Doom unfurled his clever lyrics like a roll of sod on earth... and the album curved in on itself like a two-way mirror."[87]Pitchfork also ranked Madvillainy as the 25th best album of the 2000s, describing it as "a preternaturally perfect pairing of like-minded talents" who "have each been responsible for tons of great, grimy underground hip-hop".[88] Tiny Mix Tapes considered the album the fourth best of the 2000s.[89] Rhapsody ranked the album 1st on its "Hip-Hop's Best Albums of the Decade" list.[90] PopMatters positioned it at number 49 on their list of the 100 best albums of the 2000s and praised MF Doom, who "free-associates culture high and low, from Hemingway to Robh Ruppel, across tongue-tied internal rhymes", and Madlib's "fusion breaks, psych soul, and Steve Reich", and called the album "the best chemistry of either's career, and one of the best of hip-hop, period".[91] In 2016 Q listed Madvillainy among the albums that didn't appear in their list of the best albums of last 30 years, stating that "underground hip-hop's cracked geniuses, Madlib and MF Doom, unite on a labyrinth of weed-stained vignettes that combine invention and accessibility".[92] Spin ranked it number 123 on their list of the 300 best albums of the past 30 years (1985–2014), calling it "a genius cross-pollination of seemingly divergent styles".[93] The magazine also positioned the album at number eight on the list of the 50 best hip hop debut albums since Reasonable Doubt.[94] Stylus Magazine ranked the album number 13 on their list of the top 50 albums of 2000–2005, praising Madlib's production, based on "an endless supply of funk, soul, and jazz samples", and stating that the album was "displaying the future of hip-hop".[95]

Legacy and influence

[edit]

Madvillainy influenced a generation of artists.[96][97] Among some of them are rappers Joey Badass, the late Capital Steez, Bishop Nehru, Tyler, The Creator, Earl Sweatshirt,[9] Danny Brown,[98] Kirk Knight,[99] producer and rapper Flying Lotus,[100] producer and DJ Cashmere Cat,[101] neo soul collective Jungle,[102] indie rock band Cults,[103] and Radiohead singer Thom Yorke.[9][104] The singer Bilal names it among his 25 favorite albums.[105] According to Earl Sweatshirt, Madvillainy influenced his generation the same way Wu-Tang Clan influenced the rappers of the 1990s with their album Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers).[106] In 2009 a video of Mos Def working on his album The Ecstatic in a studio was released. In the video he praised Doom, saying that "he rhymes as weird as I feel", and recited some of Doom's lines, including the ones from Madvillainy.[107] He added:[9]

Dude, I swear to God, when I saw that Madvillain record, I bought it on vinyl. I ain't have a record player. I bought it on vinyl just to stare at the album. I stared at it and I just kept going, 'I understand you'.

In 2015, in honor of the release of All-New, All-Different Marvel comics line and to pay homage to classic and contemporary hip hop albums, Marvel released variant covers inspired by influential albums.[108][109] One of them was variant cover of The Mighty Thor comics, based on Madvillainy cover. It used grayscale image of Jane Foster's face behind the metal mask, with a picture of Mjolnir in a small orange square on top right corner and "THE MIGHTY THOR" text in pixelated font on top left.[110]

Track listing

[edit]All tracks written by Daniel Dumile and Otis Jackson Jr., except where noted; all tracks produced by Madlib, except "The Illest Villains", produced by Madlib and MF Doom, and voice skits produced by Doom.[111]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Illest Villains" | 1:55 | |

| 2. | "Accordion" |

| 1:58 |

| 3. | "Meat Grinder" | 2:11 | |

| 4. | "Bistro" | 1:07 | |

| 5. | "Raid" (featuring M.E.D. aka Medaphoar) |

| 2:30 |

| 6. | "America's Most Blunted" (featuring Quasimoto) | 3:54 | |

| 7. | "Sickfit" (Instrumental) | Jackson | 1:21 |

| 8. | "Rainbows" | 2:51 | |

| 9. | "Curls" | 1:35 | |

| 10. | "Do Not Fire!" (Instrumental) | Jackson | 0:52 |

| 11. | "Money Folder" | 3:02 | |

| 12. | "Shadows of Tomorrow" (featuring Quas) | 2:36 | |

| 13. | "Operation Lifesaver AKA Mint Test" | 1:30 | |

| 14. | "Figaro" | 2:25 | |

| 15. | "Hardcore Hustle" (featuring Wildchild) |

| 1:21 |

| 16. | "Strange Ways" | 1:51 | |

| 17. | "Fancy Clown" (featuring Viktor Vaughn) | 1:55 | |

| 18. | "Eye" (featuring Stacy Epps) | 1:57 | |

| 19. | "Supervillain Theme" (Instrumental) | Jackson | 0:52 |

| 20. | "All Caps" | 2:10 | |

| 21. | "Great Day" |

| 2:16 |

| 22. | "Rhinestone Cowboy" | 3:59 | |

| Total length: | 46:22 | ||

Personnel

[edit]Credits are adapted from the album's liner notes.[111]

Madvillain

Additional personnel

- Peanut Butter Wolf – executive producer

- Allah's Reflection – additional vocals (track 17)

- Dave Cooley – mixing, mastering, recording

- James Reitano – illustration

- Egon – project coordination

- Miranda Jane – project consultant

- Eric Coleman – photography

- Jeff Jank – design

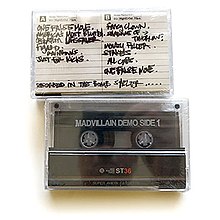

Madvillainy Demo Tape

[edit]| Madvillainy Demo Tape | |

|---|---|

| |

| Demo album by | |

| Released | September 15, 2008 September 7, 2013 |

| Recorded | 2002 |

| Studio | The Bomb Shelter (Glendale, California) |

| Genre | |

| Length | 32:37 |

| Label | Stones Throw |

| Producer | |

On July 23, 2008 Stones Throw announced the release of Madvillainy 2: The Box, a box set containing, among other things, a cassette of the leaked Madvillainy demo tape.[112] The box was later released on September 15 of that year, marking the first official release of the Madvillainy demo. The demo was given a standalone release on September 7, 2013, in celebration of the first annual Cassette Store Day.[113]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "One False Move" ("Great Day" demo) | 2:40 |

| 2. | "America's Most Blunted" | 3:28 |

| 3. | "Operation Lifesaver" ("Operation Lifesaver AKA Mint Test" instrumental demo) | 1:24 |

| 4. | "Figaro" | 2:42 |

| 5. | "Rainbows" | 2:59 |

| 6. | "Just for Kicks" ("Meat Grinder" demo) | 2:17 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Fancy Clown" | 3:57 |

| 2. | "Shadows of Tomorrow" | 3:00 |

| 3. | "Money Folder" | 4:16 |

| 4. | "Stakes" ("Supervillain Theme" demo) | 1:29 |

| 5. | "All Caps" | 2:12 |

| 6. | "One False Move" (Instrumental) ("Great Day" instrumental demo) | 2:13 |

| Total length: | 32:37 | |

Charts

[edit]Album

[edit]Original release

| Chart (2004) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Billboard 200[36] | 179 |

| US Billboard Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums[114] | 80 |

| US Billboard Top Independent Albums[115] | 10 |

| US Billboard Top Heatseekers Albums[116] | 9 |

2014 re-release

| Chart (2014) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Billboard 200[117] | 117 |

| US Billboard Top Catalog Albums[118] | 17 |

Later entries

| Chart (2019–2022) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Belgian Albums (Ultratop Flanders)[119] | 67 |

| Canadian Albums (Billboard)[120] | 64 |

| French Albums (SNEP)[121] | 116 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[122] | 58 |

| UK R&B Albums (OCC)[123] | 3 |

| US Billboard 200[124] | 73 |

Singles

[edit]| Song | Chart (2003) | Peak position |

|---|---|---|

| "Money Folder" | US Billboard Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs[34] | 66 |

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[125] | Gold | 100,000‡ |

| United States (RIAA)[126] | Gold | 500,000‡ |

|

‡ Sales+streaming figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Mad Skills: Madlib In Scratch Magazine | Stones Throw Records". www.stonesthrow.com.

- ^ Strauss, Matthew (December 31, 2020). "MF DOOM Dead at 49". Pitchfork. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums Of All Time: 500-401". NME. October 21, 2013.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. September 22, 2020.

- ^ "The 200 Greatest Hip-Hop Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. June 7, 2022.

- ^ Hultkrans, Andrew (April 19, 2011). "MF Doom, 'Operation: Doomsday' (Metal Face)". Spin. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Fields, Kiah (April 20, 2016). "Today In Hip Hop History: MF Doom Releases Debut 'Operation: Doomsday' 17 Years Ago". The Source. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Rabin, Nathan (April 26, 2011). "MF Doom: Operation Doomsday: Lunchbox". The A.V. Club. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Weiss, Jeff (August 12, 2014). "Searching for Tomorrow: The Story of Madlib and Doom's Madvillainy". Pitchfork. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Jackson, Otis (2016). "Madlib Lecture". Red Bull Music Academy (Interview). Interviewed by Jeff "Chairman" Mao. New York City. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Madvillain - Madvillainy 2LP". Stones Throw. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Pemberton, Rollie; Sylvester, Nick (March 25, 2004). "Madvillain: Madvillainy". Pitchfork. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Thurm, Eric (March 11, 2014). "A decade on, Madvillainy is still a masterpiece from hip-hop's illest duo". The A.V. Club. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c Mason, Andrew (May 8, 2005). "Mad Skills". Scratch. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ George, Lynell (July 16, 2007). "Hot on the beat's trail". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ "The 100 Best Albums of the 2000s". Complex. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Balfour, Jay (March 23, 2014). "Madvillain "Madvillainy" In Review: 10-Year Anniversary". HipHopDX. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Today in Hip-Hop: MF DOOM and Madlib Drop 'Madvillainy'". XXL. March 23, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Garrett, Charles Hiroshi, ed. (2013). The Grove Dictionary of American Music (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195314281.

He is best known for his unique approach to beatmaking and remixing which includes aggregating diverse material together from far-flung musical traditions.

- ^ Oliver, Matt (February 21, 2014). "Shadows Of Today: Ten Years Of 'Madvillainy'". Clash. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ a b c d O'Neil, Tim. "Madvillain: Madvillainy". PopMatters. Archived from the original on December 4, 2004. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Behrens, Sam (March 24, 2014). "Madvillainy Turns 10". Stereogum. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ a b c Samuelson, Sam. "Madvillainy – Madvillain". AllMusic. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ a b J-23 (March 16, 2004). "Madvillain - Madvillainy". HipHopDX. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Breihan, Tom (October 27, 2009). "New Madvillain Album in the Works". Pitchfork. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ a b Frere-Jones, Sasha (April 12, 2004). "Doom's Day". The New Yorker. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Edwards, Paul (2009). How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC. Chicago Review Press. p. 84. ISBN 9781556528163.

- ^ Dart, Chris (May 20, 2016). "Deconstructing the greatest rap songs of all time, syllable by syllable". The A.V. Club. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Downing, Andy (December 14, 2005). "Doom doesn't live up to often brilliant recordings". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ a b Guest, Tim (May 23, 2004). "Madvillain: Madvillainy". The Observer. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ^ a b "UNCOVERED: The Story Behind Madvillain's "Madvillainy" (2004) with art director Jeff Jank". Ego Trip. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Madvillain Update". Stones Throw. Archived from the original on December 12, 2003. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ "Madvillain - Curls & All Caps". Stones Throw. Archived from the original on April 3, 2004. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Singles Sales". Billboard. December 27, 2003. p. 49.

- ^ Kangas, Chaz (March 21, 2014). "March 23, 2004: The Most Important Day in Indie Rap History?". Village Voice. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ a b "Top 200 Albums, the week of April 10, 2004". Billboard. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Ferguson, Jordan (April 24, 2014). J Dilla's Donuts. 33⅓. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781623563608.

[...] Their album Madvillainy quickly became one of Stones Throw's highest-selling albums and most critically acclaimed.

- ^ "Stones Throw | Stones Throw 101". Stones Throw Records. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Stones Throw | Stones Throw 102: In Living the True Gods". Stones Throw Records. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Stones Throw to release Madvillainy Instrumentals with full picture sleeve". Fact. January 23, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "MADVILLAIN - MADVILLAINY". Stones Throw Records. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith. "Billboard 200 Chart Moves: 'Frozen' Exits Top 10 After 39 Weeks". Billboard. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Kaye, Ben (August 24, 2014). "Cassette Store Day to return in 2014, with releases from Julian Casablancas, Karen O, and Foxygen". Consequence of Sound. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "MF Doom Discography". Stones Throw Records. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ^ "Madvillainy 2: The Box". Stones Throw Records. July 23, 2008. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Patrin, Nate. "Madvillain: Madvillainy 2 Album Review". Pitchfork. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ a b "Reviews for Madvillainy by Madvillain". Metacritic. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ^ a b "Madvillain: Madvillainy". Alternative Press (191): 110. June 2004.

- ^ a b Hermes, Will (March 19, 2004). "Madvillainy". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

- ^ a b "Madvillain: Madvillainy". Mojo (127): 114. June 2004.

- ^ a b "Madvillain: Madvillainy". Q (216): 116. July 2004.

- ^ a b Caramanica, Jon (May 13, 2004). "Madvillain: Madvillainy". Rolling Stone. No. 948. p. 74.

- ^ a b Henderson, Eric (December 17, 2004). "Madvillain: Madvillainy". Slant Magazine. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (August 24, 2004). "Consumer Guide: Looking Past Differences". The Village Voice. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

- ^ Clarke, Khari (April 12, 2014). "Is It True?: Doom Says Madvillainy Sequel is 'Just About Done'". The Source. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Rosen, Jody (May 2004). "Madvillain: Madvillainy". Blender (26): 127. Archived from the original on August 18, 2004. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ^ Fields, Kiah (March 23, 2016). "Today in Hip Hop History: Madvillain Drops Madvillainy 12 Years Ago". The Source. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Segal, David (June 13, 2004). "HERE &". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Sanneh, Kelefa (April 7, 2004). "HIP-HOP REVIEW; That Man in a Mask, With Labyrinthine Rhymes to Cast". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 28, 2015. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "Top 50 Albums of 2004". Pitchfork. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "A look back at the best albums of the year". Prefixmag. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Umile, Dominic. "Best Music of 2004". PopMatters. Archived from the original on January 9, 2005. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Patrin, Nate (January 2005). "40 Best Albums of the Year". Spin. p. 66. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Pemberton, Rollie. "The Top 40 Albums of 2004". Stylus Magazine. Archived from the original on January 16, 2005. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "Pazz & Jop 2004". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on February 10, 2005. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "2004 Rewind". The Wire. No. 251. January 2005. p. 74. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "Editors' Choice". AllMusic. Archived from the original on February 14, 2005. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Oliver, Matt (December 10, 2014). "The Top 100 Albums Of Clash's Lifetime: 50-41". Clash. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ Diver, Mike (April 6, 2009). "Top Ten - Hip-Hop Albums". Clash. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ "The 100 Best Albums Streaming On Spotify Right Now". Complex. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ "The 100 Best Albums of The Complex Decade: 71. Madvillain, Madvillainy (2004)". Complex. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ^ Ahmed, Insanul; Martin, Andrew; Isenberg, Daniel; Drake, David; Baker, Ernest; Moore, Jacob; Nostro, Lauren. "25 Rap Albums From the Past Decade That Deserve Classic Status". Complex. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ "Top 150 Hip Hop Albums Of The 2000s". Hip Hop Golden Age. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ "The best music of the decade". November 19, 2009. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Beatnick, Mr. (December 2010). "The 100 Best Albums of the 2000s". Fact. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ Piyevsky, Alex; Twells, John; Raw, Son; Rascobeamer, Jeff; Geng (February 25, 2015). "The 100 best indie hip-hop records of all time". Fact. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ Hughes, Terrance (December 22, 2009). "Top 10 Hip-Hop Albums Of The Decade". Heavy.com. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ^ "The 100 Best Albums of the Aughts | Feature | Slant Magazine". Slant Magazine. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "The Top 50 Albums: 2000-2005 - Article - Stylus Magazine". www.stylusmagazine.com. Archived from the original on December 22, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ "The 100 Best Albums of the 2000s". FACT Magazine: Music News, New Music. December 2010. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "1000 albums to hear before you die". The Guardian. November 20, 2007. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ "HipHopDX's Top 10 Albums Of The '00s". HipHopDX. December 18, 2009. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ "The 30 Best Underground Hip Hop Albums Since 2000". HipHopDX. August 26, 2015. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ "40 Greatest One-Album Wonders". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time - Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. September 22, 2020. Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". NME. October 26, 2013. p. 51. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ "Staff Lists: The Top 100 Albums of 2000-04". Pitchfork. February 7, 2005. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ "Staff Lists: The Top 200 Albums of the 2000s: 50-21 | Features". Pitchfork. October 1, 2009. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ "Favorite 100 Albums of 2000-2009: 20-01". Tiny Mix Tapes. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ^ "Hip-Hop's Best Albums of the Decade - Rhapsody: The Mix". September 24, 2012. Archived from the original on September 24, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ Aspray, Benjamin. "The 100 Best Albums of the 2000s: 60-41". PopMatters. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ "A Q Celebration... 476 Modern Classics". Q. No. 361. June 2016. p. 67.

- ^ Jenkins, Craig (May 11, 2015). "The 300 Best Albums Of The Past 30 Years (1985-2014)". Spin. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ Unterberger, Andrew (July 1, 2016). "The 50 Best Hip-Hop Debut Albums Since 'Reasonable Doubt'". Spin. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ Cober-Lake, Justin. "The Top 50 Albums: 2000-2005". Stylus Magazine. Archived from the original on March 6, 2005. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ Bassil, Ryan (February 18, 2016). "Ten Shit Hot Albums by Artists Who Only Ever Made One". Noisey. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Steiner, B.J. (October 24, 2013). "Happy Birthday, Madlib!". XXL. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Nostro, Lauren. "Danny Brown's 25 Favorite Albums". Complex. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Josephs, Brian (October 7, 2015). "Kirk Knight Is Ready to Captain This Starship". Noisey. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ "The 50 Best Albums of 2012". Complex. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Phili, Stelios (March 11, 2015). "Cashmere Cat on 10 Songs That Blow His Mind". GQ. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Anderson, Errol (May 30, 2014). "The Really Wild Show: Jungle Interviewed". Clash. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Grisham, Tyler (July 27, 2011). "Cults". Pitchfork. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Colothan, Scott. "Thom Yorke Lists His Favourite New Sounds". Gigwise. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Simmons, Ted (February 26, 2013). "Bilal's 25 Favorite Albums". Complex. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ Weiss, Jeff (November 7, 2012). "Earl Sweatshirt, Captain Murphy and the Enduring Influence of the Madvillain". Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Ortiz, Edwin (March 27, 2009). "Mos Def Praises MF Doom, Compares Against Lil Wayne". HipHopDX. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Towers, Andrea. "See the newest additions to Marvel's hip-hop variant covers". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Minsker, Evan (July 14, 2015). "Marvel Comics Pay Homage to Hip-Hop Albums With Variant Covers". Pitchfork. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Lynch, Joe. "Marvel Debuts Lil B, MF DOOM & GZA Inspired Comic Covers: Exclusive". Billboard. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ a b Madvillain (2004). Madvillainy (liner notes). Los Angeles, California: Stones Throw Records. STH2065.

- ^ "Madvillainy 2: The Box". Stones Throw. July 23, 2008. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ "Madvillainy Demo Tape". Stones Throw. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ "Madvillain - Chart history". Billboard. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ "Independent Albums, the week of April 10, 2004". Billboard. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ "Heatseekers Albums, the week of April 10, 2004". Billboard. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ "Top 200 Albums, the week of September 27, 2014". Billboard. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ "Top Catalog Albums, the week of September 27, 2014". Billboard. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Madvillain – Madvillainy" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ^ "Madvillain Chart History (Canadian Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – Madvillain – Madvillainy". Hung Medien. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ^ "Official R&B Albums Chart Top 40". Official Charts Company. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ "Madvillain Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ "British album certifications – Madvillain – Madvillainy". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- ^ "American album certifications – Madvillain – Madvillainy". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved March 25, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Madvillainy at Discogs (list of releases)

- Madvillainy on Stones Throw's official channel playlist on YouTube