E. D. Nixon

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2018) |

E. D. Nixon | |

|---|---|

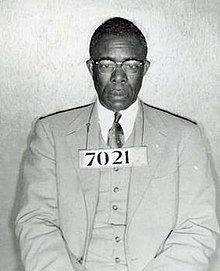

1955 bus boycott arrest photo of Nixon | |

| Born | Edgar Daniel Nixon July 12, 1899 Montgomery, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | February 25, 1987 (aged 87) Montgomery, Alabama, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Union organizer, civil rights leader |

| Spouses |

Alease Curry

(m. 1927; died 1934)Arlet Campbell (m. 1934) |

| Children | 1 |

Edgar Daniel Nixon (July 12, 1899 – February 25, 1987), known as E. D. Nixon, was an American civil rights leader and union organizer in Alabama who played a crucial role in organizing the landmark Montgomery bus boycott there in 1955. The boycott highlighted the issues of segregation in the South, was upheld for more than a year by black residents, and nearly brought the city-owned bus system to bankruptcy. It ended in December 1956, after the United States Supreme Court ruled in the related case, Browder v. Gayle (1956), that the local and state laws were unconstitutional, and ordered the state to end bus segregation.

A longtime organizer and activist, Nixon was president of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Montgomery Welfare League, and the Montgomery Voters League. At the time, Nixon already led the Montgomery branch of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters union, known as the Pullman Porters Union, which he had helped organize.

Martin Luther King Jr. described Nixon as "one of the chief voices of the Negro community in the area of civil rights," and "a symbol of the hopes and aspirations of the long oppressed people of the State of Alabama."[1]

Early life and education

[edit]Edgar D. Nixon was born on July 12, 1899, in rural, majority-black Lowndes County, Alabama to Wesley M. Nixon and Sue Ann Chappell Nixon.[2] As a child, Nixon received 16 months of formal education, as black students were ill-served in the segregated public school system. His mother died when he was young, and he and his seven siblings were reared among extended family in Montgomery.[1][2] His father was a Baptist minister.[1]

After working in a train station baggage room, Nixon rose to become a Pullman car porter, which was a well-respected position with good pay. He was able to travel around the country and worked steadily. He worked with them until 1964. In 1928, he joined the new union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, helping organize its branch in Montgomery. He also served as its president for many years.[1]

Marriage and family

[edit]Nixon married Alease Curry on August 21, 1927 in Montgomery, Alabama.[3] She died in 1934. They had a son, Edgar Daniel Nixon Jr. (1928–2011), who became an actor known by the stage name of Nick LaTour. Nixon later remarried, to Arlet Campbell, in Florida. She was with him during many of the civil rights events.[2]

Civil rights activism

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

Years before the Montgomery bus boycott, Nixon had worked for voting rights and civil rights for African Americans in Montgomery. Like other blacks in the state, they had been essentially disenfranchised since the start of the 20th century by changes in the Alabama state constitution and electoral laws. He also served as an unelected advocate for the African-American community, helping individuals negotiate with white officeholders, policemen, and civil servants.

In 1943, Nixon and lawyer Arthur Madison founded the Alabama Voters League to encourage African Americans to apply for voter registration, at a time when African Americans were generally excluded from voting in the South using highly subjective rules.[4] Nixon organized an event on June 12, 1944, in which up to 750 African Americans marched to the Montgomery County courthouse and attempted to register to vote, to protest Madison's disbarment over the voter registration campaign he conducted as part of this organization. Nixon himself gained voter registration in 1945.[4][5]

Nixon was a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), becoming president of the Montgomery chapter in 1945 and, in 1947, president of the state organization.[2]

In 1954, he was the first black to run for a seat on the county Democratic Executive Committee.[2] The next year, he questioned the Democratic candidates for the Montgomery City Commission on their positions on civil rights issues.

Challenging bus segregation

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

In the early 1950s, Nixon and Jo Ann Robinson, president of the Women's Political Council, decided to mount a court challenge to the discriminatory seating practices on Montgomery's municipal buses, along with a boycott of the bus company. A Montgomery ordinance reserved the front seats on these buses for white passengers only, forcing African-American riders to sit in the back. The middle section was available to blacks unless the bus became so crowded that white passengers were standing; in that case, blacks were supposed to give up their seats and stand if necessary. Blacks constituted the majority of riders on the city-owned bus system.

Before the activists could mount the court challenge, they needed someone to voluntarily violate the bus seating law and be arrested for it. Nixon carefully searched for a suitable plaintiff. At the same time, some women mounted their own individual challenges. For instance, 15-year-old student Claudette Colvin was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger in March 1955, nine months before Parks' action.

Nixon rejected Colvin because she became an unwed mother, another woman who was arrested because he did not believe she had the fortitude to see the case through, and a third woman, Mary Louise Smith, because her father was allegedly an alcoholic. (In 1956, Colvin and Smith were among five originally included in the successful case, Browder v. Gayle, filed on behalf of them specifically and representing black riders who had been treated unjustly on the city buses.[6] See below.)

The final choice was Rosa Parks, the elected secretary of the Montgomery NAACP. Nixon had been her boss, although he said, "Women don't need to be nowhere but in the kitchen."[7] When she asked, "Well, what about me?", he replied, "I need a secretary and you are a good one."[7]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

On December 1, 1955, Parks entered a Montgomery bus, refused to give up her seat for a white passenger, and was arrested. After being called about Parks' arrest, Nixon went to bail her out of jail. He arranged for Parks' friend, Clifford Durr, a sympathetic white lawyer, to represent her. After years of working with Parks, Nixon was certain that she was the ideal candidate to challenge the discriminatory seating policy. Even so, Nixon had to persuade Parks to lead the fight. After consulting with her mother and husband, Parks accepted the challenge.

Organizing the boycott

[edit]After Parks' arrest, Nixon called a number of local ministers to organize support for the boycott; the third man he called was Martin Luther King Jr., a young minister who was newly arrived from Atlanta, Georgia. King said he would think about it and call back. When King responded, he said that he would participate in the boycott and had already arranged a meeting of his church congregation on the issue. Nixon could not attend because of an out-of-town business trip; he took precautions to see that no one was elected to lead the boycott campaign until he returned.

When Nixon returned to Montgomery, he met with Rev. Ralph Abernathy and Rev. E.N. French to plan the program for the next boycott meeting. They came up with a list of demands for the bus company, named the new organization the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), and discussed candidates for president of the association. Nixon recommended King to Abernathy and French because Nixon believed that King had not been compromised by dealing with the local white power structure.

After a successful one-day bus boycott on December 5, 1955, Nixon met with a group of ministers to plan the larger boycott.[1] But, the meeting did not proceed as he had envisioned. The ministers wanted to organize a low-key boycott that would not upset the white power structure in Montgomery. This was completely opposite of what Nixon and the other activists hoped to achieve. An exasperated Nixon threatened to publicly denounce the ministers as cowards.[1] King stood and said that he was no coward. By the end of the meeting, he had accepted the MIA presidency and Nixon had become the treasurer. That evening, King delivered a keynote address to the full meeting at Holt Street Baptist Church.[8]

Nixon shared his labor and civil rights contacts with the MIA, organizing financial and other resources to help manage and support the boycott. These were critical to its success.[1]

Successful boycott

[edit]What was expected to be a short boycott lasted 381 days, more than one year. Despite fierce political opposition, police coercion, personal threats, and their own sacrifices, the blacks of Montgomery held the boycott. They walked to work; the people with cars gave others rides. They gave up some trips. Bus ridership plummeted, as blacks were the majority riders in the system, and the bus company was on the verge of financial ruin. In late January a bomb was set off near the home of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.,[6] and on February 1, 1956, a bomb exploded in front of Nixon's home.

Attorneys Fred Gray and Charles Langford filed the petition in federal district court for it to review the state and city laws on bus segregation in the case that became known as Browder v. Gayle (1956). They filed on behalf of the five Montgomery women who originally refused to give up their seats on city buses: Claudette Colvin, Aurelia S. Browder, Susie McDonald, Mary Louise Smith, and Jeanatte Reese. (Reese withdrew from the case in February.)[6]

On June 5, 1956, a three-judge panel of the US District Court ruled on Browder v. Gayle and determined that Montgomery's segregation law was unconstitutional, violating the Fourteenth Amendment of the US Constitution.[6] On November 13, 1956, the US Supreme Court upheld the lower court's ruling. On December 17, 1956, the Supreme Court rejected appeals by the city and state to reconsider its decision.[6]

Three days later, the Supreme Court issued its order for Montgomery to desegregate its buses.[6] With that legal victory, the MIA organizers ended the boycott. At a later rally at New York City's Madison Square Garden, Nixon talked about the symbolism of the boycott to an audience of supporters:

I'm from Montgomery, Alabama, a city that's known as the Cradle of the Confederacy, that had stood still for more than ninety-three years until Rosa L. Parks was arrested and thrown in jail like a common criminal.... Fifty thousand people rose up and caught hold to the Cradle of the Confederacy and began to rock it till the Jim Crow rockers began to reel and the segregated slats began to fall out.[9]

After the boycott

[edit]Nixon's relationship with the MIA was contentious. He frequently had sharp disagreements with others in the group and competed for leadership. He expressed resentment that King and Abernathy had received most of the credit for the boycott, as opposed to the local activists who had already spent years organizing against racism. However, King admired Nixon, describing him as "one of the chief voices of the Negro community in the area of civil rights," and "a symbol of the hopes and aspirations of the long oppressed people of the State of Alabama."[1]

Nixon resigned his post as MIA treasurer in 1957, writing a bitter letter to King complaining that he had been treated as a child and a "newcomer."[1] Nixon continued to feud with Montgomery's Black middle class community for the next decade.

By the late 1960s, through a series of political defeats, his leadership role in the MIA was eliminated. After retiring from the railroad, Nixon worked as the recreation director of a public housing project. He continued to work for civil rights, especially to improve housing and education for blacks in Montgomery.

Nixon died at the age of 87 in Montgomery on February 25, 1987.[10]

Awards and honors

[edit]- In 1985, Nixon received the Walter White Award from the NAACP.[1]

- In 1986, a year before his death, Nixon's house in Montgomery was placed on the Alabama Register of Landmarks and Heritage, in recognition of his leadership in the state.[1]

- Edgar D. Nixon Elementary School, on Edgar D. Nixon Avenue in Montgomery, is named after him.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Nixon, Edgar Daniel (1899–1987), King Encyclopedia Online, accessed 3 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Nixon, Edgar Daniel", Encyclopedia of Alabama. Accessed October 29, 2023.

- ^ Alabama County Marriages, 1809–1950," database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QKMY-GT1Y : 15 November 2020), Edgar D Nixon and Alleas [sic] Curry, 21 Aug 1927; citing Montgomery, Alabama, United States, County Probate Courts, Alabama; FHL microfilm 1,535,180.

- ^ a b Thornton, J. Mills (2002). Dividing Lines: Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma. University of Alabama Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 0-8173-1170-X.

- ^ Lyman, Brian (February 25, 2021). "The believer: In 1944, Arthur Madison launched a voter registration in Montgomery". Montgomery Advertiser. Retrieved October 29, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Browder v. Gayle, 352 U.S. 903 (1956)", Martin Luther King, Jr. Encyclopedia. Accessed December 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Olson, Lynne (2001). Freedom's Daughters: The Unsung Heroines of the Civil Rights Movement from 1830 to 1970. Simon and Schuster. pp. 97–. ISBN 978-0-684-85012-2. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Montgomery Bus Boycott speech, at Holt Street Baptist Church (5 December 1955)

- ^ Raines, Howell (1983) [1977]. My Soul Is Rested: Movement Days in the Deep South Remembered. New York: Penguin Books. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-14-006753-8.

- ^ "E. D. Nixon, Leader in Civil Rights, Dies". The New York Times. 27 February 1987. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Howell Raines, My Soul Is Rested, The Story Of The Civil Rights Movement In The Deep South, ISBN 0-14-006753-1

- Taylor Branch, Parting The Waters; America In The King Years 1954–63, ISBN 0-671-46097-8

- Stride Toward Freedom, by Martin Luther King Jr., ISBN 0-06-250490-8

- The Origins Of The Civil Rights Movement, Black Communities Organizing For Change, by Aldon D. Morris, ISBN 0-02-922130-7

External links

[edit]- "E.D. Nixon: organizer of Montgomery bus boycott" The Militant, 2005

- "Rosa Parks: a working-class militant", The Militant, 2005