Tupan Patera

Tupan Patera is an active volcano on Jupiter's moon Io. It is located on Io's anti-Jupiter hemisphere at 18°44′S 141°08′W / 18.73°S 141.13°W[1]. Tupan consists of a volcanic crater, known as a patera, 79 kilometers across and 900 meters deep.[2] The volcano was first seen in low-resolution observations by the two Voyager spacecraft in 1979, but volcanic activity was not seen at this volcano until June 1996 during the Galileo spacecraft's first orbit.[3] Following this first detection of near-infrared thermal emission and subsequent detections by Galileo during the next few orbits, this volcano was formally named Tupan Patera, after the thunder god of the Tupí-Guaraní indigenous peoples in Brazil, by the International Astronomical Union in 1997.[1]

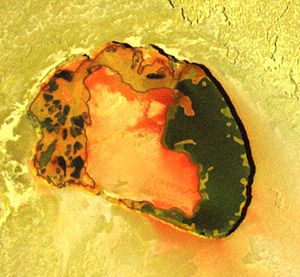

Additional observations by Galileo's Near-Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (NIMS) between 1996 and 2001 revealed Tupan to be a persistently active volcano, visible during most NIMS observations of Io's anti-Jupiter hemisphere.[4][5] Galileo acquired high-resolution color images and near-infrared spectra of Tupan Patera during an encounter on October 16, 2001. This data revealed warm, dark silicate lava on the eastern and western sides of the patera floor with an "island" of bright, cool material in the middle.[2][5] Reddish material was observed along the margins of the bright island as well as on the bright plains to the southeast of the volcano. This is indicative of short-chain sulfur being emitted from vents on the patera floor by recent volcanic activity.[2] The island as well as a shelf of material at the base of the patera wall is outlined by a "strand" of dark material. This strand line may result from lava filling the patera floor, then deflating due to either degassing of the cooling lava or drainage back into the magma chamber. Alternatively, the strand line may have been created from limited volcanic activity along the edge of the patera floor. The mix of red-orange and dark material on the volcano's western side possibly resulted from sulfur melting from the central island and the patera wall and covering the dark material in this area.[2] This theory is supported by the cooler temperatures seen on the western side of Tupan, cool enough perhaps to support the melting and solidification of sulfur, compared to the much darker eastern side.[5] The morphology of Tupan Patera may also be consistent with a sill that is still exhuming itself.[6]

After the last Galileo flyby of Io in January 2002, Tupan remained active with observations of a thermal emission from the volcano by ground-based observers using the Keck Telescope and by the New Horizons spacecraft.[7] A large eruption at Tupan was observed by astronomers using the 10-meter adaptive optics at the Keck Observatory on March 8, 2003.[8] Other than this major eruption, activity at Tupan through the Galileo mission and afterward has been persistent, with variations in power output from the patera floor being episodic, similar to, but at lower energy levels, Loki Patera.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Tupan Patera". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Research Program.

- ^ a b c d Turtle, E. P.; et al. (2004). "The final Galileo SSI observations of Io: orbits G28-I33". Icarus. 169 (1): 3–28. Bibcode:2004Icar..169....3T. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2003.10.014.

- ^ Lopes-Gautier, Rosaly; et al. (1997). "Hot spots on Io: Initial results from Galileo's near-infrared mapping spectrometer" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 24 (20): 2, 439–2, 442. Bibcode:1997GeoRL..24.2439G. doi:10.1029/97GL02662.

- ^ Lopes-Gautier, Rosaly; et al. (1999). "Active Volcanism on Io: Global Distribution and Variations in Activity". Icarus. 140 (2): 243–264. Bibcode:1999Icar..140..243L. doi:10.1006/icar.1999.6129.

- ^ a b c d Lopes, R. M. C.; et al. (2004). "Lava lakes on Io: Observations of Io's volcanic activity from Galileo NIMS during the 2001 fly-bys". Icarus. 169 (1): 140–174. Bibcode:2004Icar..169..140L. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2003.11.013.

- ^ Keszthelyi, L.; et al. (2004). "A Post-Galileo view of Io's Interior". Icarus. 169 (1): 271–286. Bibcode:2004Icar..169..271K. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.01.005.

- ^ Spencer, J. R.; et al. (2007). "Io Volcanism Seen by New Horizons: A Major Eruption of the Tvashtar Volcano". Science. 318 (5848): 240–43. Bibcode:2007Sci...318..240S. doi:10.1126/science.1147621. PMID 17932290. S2CID 36446567.

- ^ Marchis, F.; et al. (2004). "Volcanic Activity of Io Monitored with Keck-10m AO in 2003-2004". American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting. San Francisco, California. Bibcode:2004AGUFM.V33C1483M. #V33C-1483.