Valley of the Fallen

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Spanish. (January 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

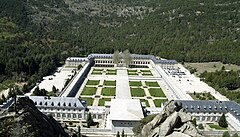

The Valley of Cuelgamuros (Spanish: Valle de Cuelgamuros), formerly known as the Valley of the Fallen (Spanish: Valle de los Caídos), is a monument in the Sierra de Guadarrama, near Madrid. The valley contains a Catholic basilica and a monumental memorial in the municipality of San Lorenzo de El Escorial.[1][2] Dictator Francisco Franco ordered the construction of the monumental site in 1940; it was built from 1940 to 1958, and opened in 1959.[3] Franco said that the monument was intended as a "national act of atonement" and reconciliation.[4]

The site served as Franco's burial place from his death in November 1975—although it was not originally intended that he be buried there—until his exhumation on 24 October 2019 following a long and controversial legal process, due to moves to remove all public honoration of his dictatorship.

The monument, considered a landmark of 20th-century Spanish architecture, was designed by Pedro Muguruza and Diego Méndez on a scale to equal, according to Franco, "the grandeur of the monuments of old, which defy time and memory." Together with the Universidad Laboral de Gijón, it is the most prominent example of the original Spanish Neo-Herrerian style, which was intended to form part of a revival of Juan de Herrera's architecture, exemplified by the nearby royal residence El Escorial. This uniquely Spanish architecture was widely used in public buildings of post-war Spain and is rooted in international fascist classicism as exemplified by Albert Speer or Mussolini's Esposizione Universale Roma.

The monument precinct covers over 13.6 square kilometres (3,360 acres) of Mediterranean woodlands and granite boulders on the Sierra de Guadarrama hills, more than 900 metres (3,000 ft) above sea level and includes a basilica, a Benedictine abbey, a guest house, the Valley, and the Juanelos—four cylindrical monoliths dating from the 16th century. The most prominent feature of the monument is the towering 150-metre-high (500 ft) Christian cross, the tallest such cross in the world, erected over a granite outcrop 150 metres over the basilica esplanade and visible from over 30 kilometres (20 mi) away. Work started in 1940 and took over eighteen years to complete, with the monument being officially inaugurated on 1 April 1959. According to the official ledger, the cost of the construction totalled 1,159 million pesetas, funded through national lottery draws and donations. Some of the labourers were prisoners who traded their labour for a reduction in time served.

The complex is owned and operated by the Patrimonio Nacional, the Spanish governmental heritage agency, and ranked as the third most visited monument of the Patrimonio Nacional in 2009. The Spanish social democrat government closed the complex to visitors at the end of 2009, citing safety reasons connected to restoration on the façade. The decision was controversial, as the closure was attributed by some people to the Historical Memory Law enacted during José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero's premiership,[5] and there were claims that the Benedictine community was being persecuted.[6] The works[clarification needed] include the Pietà sculpture prominently featured at the entrance of the crypt, using hammers and heavy machinery.[7][8]

Basilica, cross and abbey

[edit]

One of the world's largest basilicas rises above the valley along with the tallest memorial cross in the world. The Basílica de la Santa Cruz del Valle de los Caídos (Basilica of the Holy Cross of the Valley of the Fallen) is hewn out of a granite ridge. The 150-metre-high (500 feet) cross is constructed of stone.[citation needed]

In 1960, Pope John XXIII declared the underground crypt a basilica. The dimensions of this underground basilica, as excavated, are larger than those of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. To avoid competition with the apostle's grave church on the Vatican Hill, a partitioning wall was built near the inside of the entrance and a sizeable entryway was left unconsecrated.[citation needed]

The memorial sculptures to the fallen at the basilica are works by Spanish sculptor Luis Sanguino.[9][10]

The monumental sculptures over the main gate and the base of the cross culminated the career of Juan de Ávalos. The monument consists of a wide explanada (esplanade) with views of the valley and the outskirts of Madrid in the distance. A long vaulted crypt was tunnelled out of solid granite, piercing the mountain to the massive transept, which lies exactly below the cross.[citation needed]

On the wrought-iron gates, Franco's neo-Habsburg double-headed eagle is prominently displayed. On entering the basilica, visitors are flanked by two large metal statues of art deco angels holding swords.[citation needed]

There is a funicular that connects the basilica with the base of the cross. There is a spiral staircase and a lift inside the cross, connecting the top of the basilica dome to a trapdoor on top of the cross,[11] but their use is restricted to maintenance staff.

The Benedictine Abbey of the Holy Cross of the Valley of the Fallen (Spanish: Abadía Benedictina de la Santa Cruz del Valle de los Caídos), on the other side of the mountain, houses priests who say perpetual Masses for the repose of the fallen of the Spanish Civil War and later wars and peacekeeping missions fought by the Spanish Army. The abbey ranks as a Royal Monastery.[citation needed]

Valley of the Fallen

[edit]The valley that contains the monument, preserved as a national park, is located 10 km northeast of the royal site of El Escorial, northwest of Madrid. Beneath the valley floor lie the remains of 40,000 people, whose names are accounted for in the monument's register. The valley contains both Nationalist and Republican graves, but the dedication written in stone reads Caídos por Dios y por España (Fallen for God and for Spain, which is criticized because it was the Francoist Spain motto) and numerous symbols of the Francoist regime.

Moroever, Republicans were interred here mostly without the consent or even the knowledge of their families; some estimates claim that there are 33,800 victims of Francoism interred — and their families have legal problems in recovering the remains of their family member.[12] Franco was exhumed and removed from the church in 2019 as an effort to discourage public veneration of the site.

Franco's tomb (1975–2019)

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Francoism |

|---|

Eagle of Saint John |

After the dictator's death, the interim Government led by Prince Juan Carlos and Prime Minister Carlos Arias Navarro designated the site in 1975 as his burial place. Franco's family, when asked if they had any opinion on where he should be buried, said they had none. According to a friend and colleague of Arias, the decision to bury Franco in the Valley was not made by Franco or his family, but probably by the king.[13] The family agreed to the interim Government's request to bury him in the Valley, and has stood by the decision.[citation needed]

Before his death, nobody had expected that Franco would be buried in the Valley. Moreover, the grave had to be excavated and prepared within two days, forcing last minute changes in the plumbing system of the Basilica. Unlike the fallen of the Civil War who were laid to rest in tombs behind the chapels on the sides of the basilica, Franco was buried behind the main altar, in the central nave. His grave is marked by a tombstone engraved with just his given name and first surname, on the choir side of the main high altar (between the altar and the apse of the Church; behind the altar, from the perspective of a person standing at the main door). [citation needed]

Franco is the only person interred in the Valley who did not die in the Civil War. The argument given by the defenders of his tomb is that in the Catholic Church the developer of a church can be buried in the church that he has promoted. Therefore, Franco would be in the Valley as the promoter of the basilica's construction.[13]

Franco was the second person interred in the Santa Cruz basilica. Franco had earlier interred José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the founder of the Falange movement, who was executed by the Republican government in 1936 and was buried by the Francoist government under a modest gravestone on the nave side of the altar. Primo de Rivera died on 20 November 1936, exactly 39 years before Franco. His grave is in the corresponding position on the other side of the altar. Accordingly, 20 November is annually commemorated by large crowds of Franco supporters and various Falange successor movements and individuals, flocking to the Requiem Masses held for the repose of the souls of their political leaders.[citation needed]

Exhumation and removal of Franco's remains

[edit]On 29 November 2011 the Expert Commission for the Future of the Valley of the Fallen, formed by the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero on 27 May 2011 under the Historical Memory Law and charged to give advice for converting the Valley to a "memory centre that dignifies and rehabilitates the victims of the Civil War and the subsequent Franco regime,"[14] rendered a report[15] recommending as its principal proposal for the commission's stated end the removal of the remains of Franco from the Valley for reburial at a location to be chosen by his family, but only after first obtaining a broad parliamentary consensus for such action. The Commission based its decision upon Franco having not died in the Civil War and the aim of the Commission that the Valley be exclusively for those on both sides who had died in the Civil War. In regard to Primo de Rivera the Commission recommended, since a victim of the Civil War, his remains should stay at the Valley but relocated within the Basilica mausoleum on equal footing with those remains of others who died in the conflict. The Commission further conditioned its recommendation for the removal of the remains of Franco from the Valley and the relocation of the remains of Primo de Rivera within the Basilica mausoleum upon the consent of the Catholic Church since "any action inside of the Basilica requires the permission of the Church." Three members of the twelve person commission gave a joint dissenting opinion opposing the recommendation for the removal of the remains of Franco from the Valley claiming such action would only further "divide and stress Spanish society."[16] The Commission additionally proposed for its report creating a "meditation centre" in the Valley for those not of the Catholic faith, the names shown on the esplanade that leads into the Basilica mausoleum of all Civil War victims buried at the Valley who can be identified and an "interpretive centre" be built to explain how and why the Valley exists. The total cost of the proposed changes to the Valley was estimated by the Commission at €13 million.[17] On 20 November, nine days before the issuance of the report of the commission and ironically on the 36th anniversary of the death of Franco, the conservative Popular Party (PP) won for the 2011 General Election absolute majorities in both Spain's lower house, the Congress of Deputies and Senate.[18]

On 15 March 2019 the government of Pedro Sanchez announced that Franco would be exhumed and reburied at Mingorrubio Cemetery in El Pardo with his wife Carmen Polo, and that the exhumation would take place on 10 June 2019, assuming the Supreme Court did not issue a precautionary order preventing the exhumation until a decision for those appeals of the Franco family and Benedictine Community presently before it.[19][20]

On 19 March 2019 the Francisco Franco National Foundation filed an appeal with the Supreme Court contending the February agreement of the Council of Ministers for the exhumation is "null and void" for violating "openly" not only the Constitution, but as well the royal decree that modifies the law of Historical Memory and "all the regulations that make up the legal regime" of the B, in addition to European laws and regulations. The Franco Foundation further prayed the Supreme Court stay any action to remove the remains of Franco during the pendency of its appeal.[21] On 4 June 2019 the five magistrates of the Fourth Administrative Contentious Division of the Supreme Court unanimously suspended the exhumation pending a final decision for those appeals in opposition to the exhumation filed by the Franco Family, the Benedictine Community, the Franco Foundation and the Association for the Defense of the Valley of the Fallen.[22][23][24]

On 24 September 2019 the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favour of exhumation and rejected the arguments put forward by Franco's family. It was reported that the exhumation could take place before 10 November 2019 Spanish election and would inter Franco's remains in the El Pardo Cemetery.[25]

On 24 October 2019, in the presence of Franco's relatives and Dolores Delgado, Spain's Minister of Justice, the coffin containing Franco's remains was exhumed from the basilica in the Valley of the Fallen. The coffin was carried out into the plaza by members of the dictator's family, who exclaimed: ′¡Viva España! ¡Viva Franco!′ (′Long live Spain! Long live Franco!′) as they lowered it into a hearse. It was then secured in a waiting helicopter, which transported it to the Mingorrubio-El Pardo municipal cemetery, where Franco was reburied alongside his wife, Carmen Polo. The Franco family chose Ramón Tejero, an Andalucían parish priest, and son of the Guardia Civil lieutenant colonel Antonio Tejero, who violently stormed the Spanish Parliament during the unsuccessful military coup on 23 February 1981, to say mass at the reinterment ceremony.[26]

Controversy

[edit]Presenting the monument in a politically neutral way poses a number of problems, not least of which is the strength of opposing opinions on the issue. The Times quoted Jaume Bosch, a Catalan politician and former MP seeking to change the monument,[clarification needed] as saying: "I want what was in reality something like a Nazi concentration camp to stop being a nostalgic place of pilgrimage for Francoists. Inevitably, whether we like it or not, it's part of our history. We don't want to pull it down, but the Government has agreed to study our plan."[27]

The charge that the monument site was "like a Nazi concentration camp" refers to the use of convict labour, including Republican prisoners, who traded their labour for a reduction in time served. Although Spanish law prohibited the use of slave labour at the time, it did provide for convicts to choose voluntary work on the basis of redeeming two days of conviction for each day worked. This law remained in force until 1995. This benefit was increased to six days when labour was carried out at the basilica with a salary of 7 pesetas per day, a regular worker's salary at the time, with the possibility that the family of the convict would benefit from the housing and Catholic children's schools that were built in the valley for them by the other workers. Only convicts with a record of good behaviour would qualify for this redemption scheme, because the work site was considered to be a low security environment. The motto used by the Nationalist government was "el trabajo ennoblece" ("work ennobles").[citation needed]

It is claimed that by 1943, the number of prisoners who were working at the site reached close to six hundred.[28] It is also claimed that up to 20,000 prisoners were used for the overall construction of the monument and that forced labour was used.[29]

According to the official programme records, 2,643 workers directly participated in the construction, and some of them were highly skilled, as was required by the complexity of the work. 243 of these were convicts. During the eighteen-year construction period, the official tally of workers who died as a result of accidents totalled fourteen.[30]

The socialist Spanish government of 2004–2011 instituted a statewide policy of removal of Francoist symbols from public buildings and spaces, leading to an uneasy relationship with a monument that is the most conspicuous legacy of Franco's rule.

Political rallies in celebration of Franco are now banned by the Historical Memory Law, voted on by the Congress of Deputies on 16 October 2007. This law dictated that "the management organisation of the Valley of the Fallen should aim to honour the memory of all of those who died during the civil war and who suffered repression".[31] It has been suggested that the Valley of the Fallen be re-designated as a "monument to Democracy" or as a memorial to all Spaniards killed in conflict "for Democracy".[32] Some organisations, among them centrist Catholic groups, question the purpose of these plans, on the basis that the monument is already dedicated to all of the dead, civilian and military of both Nationalist and Republican sides.[citation needed]

The Democratic Memory Law of October 2022 envisaged the future of the Valley of the Fallen as a civil cemetery. As Primo de Rivera had required a Catholic burial, his family arranged for his body be exhumed from the Valley in April 2023 and reburied in Saint Isidore Cemetery in Madrid.[33]

Closure and reopening of the monument

[edit]In November 2009, Patrimonio Nacional controversially ordered the closure of the basilica for an indefinite period of time, alleging preservation issues also affecting the Cross and some sculptures.[5] These allegations were contested by some experts and by the Benedictine Order religious community that lives at the complex, and were seen by some conservative opinion groups as a policy of harassment against the monument.[34] In 2010, the Pietà sculpture group started to be "dismantled" with hammers and heavy machinery, which the Juan de Ávalos trust feared could cause irreparable damage to the sculpture. As a result, thereof, the trust filed several lawsuits against the Spanish government.[35] At the time, several parallels were made by conservative and liberal groups between the dismantling of the Pietà under the PSOE government and the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamyan by the Taliban.[36][37]

Following the 2011 Spanish general election, on 1 June 2012 the conservative PP government of Mariano Rajoy reopened the monument to the public with the exception only of the base of the cross, in the past accessible by cable car or on foot, which will remain closed to ascent while the sculptures of the four apostles and the cardinal virtues forming part of the base of the cross are presently under engineering review and restoration for cracks and other deterioration.[38] Before the official reopening on 1 June 2012, access for the public to the basilic was already possible in 2011. Beginning on 1 June 2012 the charge for entry to the monument had been 5 euros. The 5 euro entry fee was anticipated to generate around 2 million euros a year if the Valley of the Fallen once again attracted 500,000 visitors annually, the approximate number of annual visitors before closure of the monument in 2009 by the PSOE government.[39][40] Starting on 2 May 2013, and over the strong objection of the Association for the Defense of the Valley of the Fallen, the entry fee for the monument was increased from 5 to 9 euros.[41][42][43] Prior to its closure in 2009, the Valley of the Fallen was the third most visited site of the Patrimonio Nacional after only the Royal Palace of Madrid and El Escorial.[44] For the accommodation of visitors a cafeteria restaurant located in the cable car building of the monument has been re-opened.[45] The Valley of the Fallen attracted 254,059 visitors in 2015, 262,860 visitors in 2016 and 283,263 visitors in 2017.[46][47] There were 378,875 visitors in 2018 to the Valley of the Fallen[48] and 318,248 visitors in 2019.[49]

In popular culture

[edit]

The Valle de los Caídos appears in Richard Morgan's 2002 novel Altered Carbon, where it is being used as a base of operations for one of the major antagonists, Reileen Kawahara.[50]

It also appears in the 2010 Spanish dark comedy film The Last Circus (Spanish: Balada triste de trompeta), as a visual homage to the climactic Mount Rushmore scene in the Hitchcock classic North by Northwest.[51][52]

Graham Greene's 1982 novel Monsignor Quixote uses a visit to the Valle to illustrate the competing political and social attitudes to Franco's reign and the status of his tomb in modern Spain.

There is also a large reference to this monument and the labourers who built it in Victoria Hislop's book The Return.

In 2013, Spain saw the release of the film All'Ombra Della Croce (Spanish: A la Sombra de la Cruz, "In the Shadow of the Cross") directed by the Italian filmmaker Alessandro Pugno.[53] The film tells the secret story of the children of the chorus who sing every day in the mass.[54] They live in a boarding school inside the monument and receive a traditional education.[55] The film was awarded with the first prize for the best documentary at Festival de Málaga de Cine Español.[citation needed]

In the 2016 film The Queen of Spain, actor Antonio Resines plays Blas Fontiverosa, a film director who returns to Spain after fleeing following the Civil War and is captured and forced to work on the construction of the Valley.

In 2016, Mayor of Madrid Manuela Carmena, proposed to change the site's name from "El Valle de los Caídos" to "El Valle de la Paz" (The Valley of Peace).[56]

The monument’s construction and significance is paralleled with that of El Escorial in Carlos Fuentes’s 1975 novel Terra Nostra.

The monument's name is the title of a 1978 novel[57] by the Spanish author Carlos Rojas Vila. Part of the novel's plot is set in the late days of the Francoist Spain.

The monument appears in Dan Brown's novel Origin.

The monument is referenced in Ruta Sepetys' 2019 novel Fountains of Silence.

The monument appears in Edwin Torres's 1975 novel Carlito's Way in a scene where the protagonist, Carlito Brigante, is setting up an informant for a hit.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Rainsford, Sarah (19 July 2011). "Fate of Franco's Valley of Fallen reopens Spain wounds". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Franco, Francisco (2 April 1940). "Decreto de 1 de abril de 1940 disponiendo se alcen Basílica, Monasterio y Cuartel de Juventudes, en la finca situada en las vertientes de la Sierra del Guadarrama (El Escorial), conocida por Cuelga-muros, para perpetuar la memoria de los caídos en nuestra Gloriosa Cruzada" (PDF). Boletín Oficial del Estado (in Spanish) (93): 2240. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "El Valle de los Caídos en cifras y fechas" [The Valley of the Fallen in numbers and dates]. El Mundo (in Spanish). 24 August 2018.

- ^ Moreno Garrido, Belen (2 July 2010). "EL VALLE DE LOS CAÍDOS: UNA NUEVA APROXIMACIÓN". Revista de Historia Actual (in Spanish). 8 (8): 32. ISSN 1697-3305.

- ^ a b "Una decisión que traerá polémica: Ordenan el cierre del Valle de los Caídos por tiempo indefinido" [A controversial decision: The indefinite closure of the Valley of the Fallen is ordered]. Diario de la Sierra (in Spanish). 10 February 2010. Archived from the original on 16 February 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ Quesada, Juan Diego (15 November 2010). "El prior del Valle de los Caídos: "Nos persiguen como en 1934"" [The Prior of the Valley of the Fallen: "We are being persecuted like in 1934"]. El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ Europa Press (23 April 2010). "El desmontaje de 'La Piedad' del Valle de los Caídos, a 'mazazo limpio'". El Mundo (in Spanish). Unidad Editorial Internet, S.L. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ "El Tribunal Superior de Justicia de Madrid acepta a trámite el Recurso Contencioso Administrativo interpuesto por la Asociación para la Defensa del Valle, contra el cierre de todo el recinto del Valle de los Caídos". Association for the Protection of the Valley of the Fallen. Archived from the original on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

Images that show how the sculpture is being destroyed

- ^ "Luis Antonio Sanguino de Pascual – Alerta Digital". www.alertadigital.com. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ "Castillo de Sanguino - Luis Sanguino". web.archive.org. 24 August 2014. Archived from the original on 24 August 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ "The Monumental Cross" (in Spanish). Team VKi2. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ Els que volen treure els republicans del Valle de los Caídos: "Continuen allà indignament", Corporació Catalana de Mitjans Audiovisuals,25/10/2019, https://www.ccma.cat/324/republicans-que-volen-sortir-del-valle-de-los-caidos-continuen-alla-indignament/noticia/2958390/

- ^ a b Fraguas, Rafael (16 October 2010). "Una sepultura para Franco en Mingorrubio" [A tomb for Franco in Mingorrubio]. El País (in Spanish).

- ^ "Expert Commission on the Future of the Valley of the Fallen" (in Spanish). Memoria Histórica. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Expert Commission on the Future of the Valley of the Fallen" (PDF) (in Spanish). Ministro de la Presidencia. 29 November 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "The Valley of the Fallen Commission proposes that Franco's remains are moved" (in Spanish). El Mundo. 29 November 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "The Valley of the Fallen Commission recommends that Franco's remains are moved" (in Spanish). ABC. 30 November 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Spanish General Election Results". News from Spain. 21 November 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ Cué, Carlos E. (15 March 2019). "El Gobierno aprueba la exhumación de Franco el 10 de junio y su traslado al cementerio de El Pardo". El País – via elpais.com.

- ^ Junquera, Natalia (4 June 2019). "El Supremo paraliza la exhumación de Franco". elpais.com (in Spanish). Madrid: Prisa. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ "La Fundación Francisco Franco pide al Supremo la suspensión de la exhumación". 20 March 2019.

- ^ "El Supremo suspende por unanimidad la exhumación de Franco". ABC (in Spanish). 4 June 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "El Tribunal Supremo suspende la exhumación de los restos de Franco". ELMUNDO (in Spanish). 3 June 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "El Supremo paraliza la exhumación de Franco del Valle de los Caídos". La Razón (in Spanish). 4 June 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "Franco exhumation: Spain's Supreme Court backs move to cemetery". BBC News. 24 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Jones, Sam (24 October 2019). "'Spain is fulfilling its duty to itself': Franco's remains exhumed". The Guardian. Madrid: Guardian News & Media Limited. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ "Spain reclaims Franco's shrine". Times Online (subscription only). Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ Vidal, César (22 October 2000). "How the Cross of the Fallen was constructed". Libertad Digital (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Spain's 'monstrosity' remembering Franco era". European Jewish Press. 17 November 2005. Archived from the original on 24 January 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Ródenas, Virginia (15 September 2008). "La Fundación Francisco Franco no convocará más funerales el 20-N en el Valle de los Caídos". ABC (in Spanish). Madrid: Vocento. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Informe de la ponencia. Por la que se reconocen y amplían derechos y se establecen medidas en favor de quienes padecieron persecución o violencia durante la Guerra Civil y la Dictadura" (PDF). Boletín Oficial de las Cortes Generales (in Spanish). Congreso de los Diputados. 16 October 2007. pp. 172–184. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "Unknown Title". Times Online (subscription only). Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Jones, Sam (23 April 2023). "Body of Spain's fascist party founder to be removed from basilica". The Guardian.

- ^ Pío Moa (14 February 2010). "The Valley of the Fallen and the Taliban" (in Spanish). Libertad Digital. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Juan de Ávalos's son complains to National Heritage about the dismantling of the Pietà" (in Spanish). Libertad Digital. 14 May 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "The controversial removal of 'La Pietà' Valley of the Fallen begins" (in Spanish). Público. 26 April 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Taliban Socialists decapitate Ávalos' Pietà in the Valley of the Fallen" (in Spanish). Aragón Liberal. 6 November 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "National Heritage calls for a report about the restoration of the Valley of the Fallen" (in Spanish). El Mundo. 5 August 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "El Gobierno acelera el pleno funcionamiento del Valle de los Caídos desde el día 1" (in Spanish). elConfidencial.com. 12 June 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "The State will earn two million Euros by charging for entry to the Valley of the Fallen" (in Spanish). El Mundo. 29 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Patrimonio Nacional sube un 80% las entradas al Valle de Los Caídos" (in Spanish). Intereconomía. 5 April 2013. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "The PP government wants to close the Valley of the Fallen" (in Spanish). El Confidencial Digital. 26 April 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "The Association for the Protection of the Valley of the Fallen is collecting signatures against rising prices at the Monument" (in Spanish). Europa Press. 4 May 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "National Heritage calls for a report on the restoration of the Valley of the Fallen" (in Spanish). La Información. 5 August 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Cafetería del Funicular del Valle de los Caídos" [Cableway Café at the Valley of the Fallen] (in Spanish). Asociación Para La Defensa Del Valle De Los Caídos. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ "Los dos mundos del Valle de los Caídos". 15 May 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ "El Valle de los Caídos: un monumento que sobrevive entre la dejadez y las sombras". 29 April 2018. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ "El Valle de los Caídos aumentó un 33% las visitas en 2018 en plena polémica por la exhumación de Franco". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 3 January 2019.

- ^ "Las visitas al Valle de los Caídos descendieron un 16% en 2019, año de la exhumación de Franco". 5 January 2020.

- ^ Morgan, Ricahard K. (2002). Altered Carbon. Del Rey Books. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-345-45768-4.

- ^ "The Last Circus — Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. 14 October 2010.

- ^ ""Balada Triste de Trompeta", triste es poco – Extracine".[permanent dead link]

- ^ Fernández-Santos, Elsa (20 March 2013). "Franco's choirboys". El País (in Spanish). Madrid: Prisa. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ Kassam, Ashifa (25 May 2013). "The school that Franco built". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ Pugno, Alessandro; Alonso, Oscar (17 June 2014). "Synopsis All'ombra della croce". Punto de Vista. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Manuela Carmena propone cambiar el nombre del "Valle de los Caídos" por el "Valle de la Paz"". El Mundo (in Spanish). Unidad Editorial. 31 March 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ^ Rojas Vila, Carlos (1978). El Valle de los Caídos. Ediciones Destino. ISBN 8423309592.

Further reading

[edit]- Costa, Alex W. Palmer,Matías. "The Battle Over the Memory of the Spanish Civil War". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Stockey, Gareth. Valley of the Fallen: The (N)ever Changing Face of General Franco's Monument (CCC Press, 2013). ISBN 9781905510429

External links

[edit]- WAIS Forum on Spain, 2003: "Spain: the Valley of the Fallen": includes quote from Franco's decree, 1 April 1940

- Abadía de la Santa Cruz del Valle de los Caídos: Official Website (in Spanish).

- El Valle de los Caídos: (in Spanish)

- Fundación Francisco Franco, Valle de los Caídos: from Franco's Memorial Trust (in Spanish)

- Valley of the Fallen: visitor information and photos

- Cruz de los Caídos drawings and plans from the architectural website skyscraperpage.com

- The Valley of the Fallen: History and Photos.

- "Manifesto for historians regarding the Valley of the Fallen" by Pío Moa, leading Spanish historian about the construction of the monument and the alleged government policy of harassment (in Spanish)

- Basilica churches in Spain

- Mausoleums in Spain

- Monuments and memorials in the Community of Madrid

- Spanish Civil War

- Benedictine monasteries in Spain

- Monasteries in the community of Madrid

- Buildings and structures in the Community of Madrid

- Tourist attractions in the Community of Madrid

- Monumental crosses

- Francisco Franco

- Francoist monuments and memorials in Spain

- Victory monuments