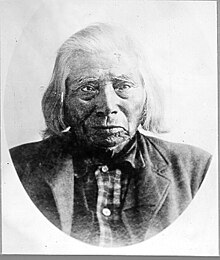

Spokane Garry

Spokane Garry | |

|---|---|

Chief Spokane Garry | |

| Born | 1811 Junction of the Spokane and the Little Spokane Rivers |

| Died | 1892 (aged 80–81) |

| Other names | Chief Garry Spokan Garry Chief Spokane Garry |

Spokane Garry (sometimes spelled Spokan Garry, Spokane: Slough-Keetcha) (c. 1811[1] – 1892) was a Native American leader of the Middle Spokane tribe. He also acted as a liaison between white settlers and American Indian tribes in the area which is now eastern Washington state.

Early life and education

[edit]Slough-Keetcha was born at the junction of the Spokane and the Little Spokane Rivers in or around 1811.[2] He was the son of the tribal chief of the Middle Spokanes, whose name is given by various sources as Illum-Spokanee, Illim-Spokanee[3] and Ileeum Spokanee.[4]

When white settlers arrived in the area in 1825, the boy was one of two chosen by the Hudson's Bay Company[5] to be taught at an Anglican mission school at Fort Garry, Rupert's Land (now Winnipeg, Manitoba), which was run by the Missionary Society of the Church of England. Before he left for Manitoba, he was renamed "Spokane Garry" in honor of his tribe and the deputy governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, Nicholas Garry.[6] His baptism on June 24, 1827 is said to be the first Protestant baptism of a non-white person west of the Rocky Mountains.[7] He was accompanied by another boy known as Kootenais Pelly, who became Garry's closest friend at the school.[3]

The students learned English at Fort Garry and were also taught new forms of survival skills. Garry enjoyed learning, but found adjusting to the new life difficult. One story relates that he was once disciplined for disobedience by being whipped with a switch while an older white student held him. Garry became afraid and clenched his teeth only to realize afterwards that he had bitten into the ear of the student holding him. The student waved off the inadvertent attack, leading Garry to realize for the first time that white settlers could be well-intentioned, but also that resistance to authority would likely be futile.[4]

Chief Illim-Spokanee died in late 1828. When spring arrived, Garry and Pelly left the mission school and began the arduous trek back to the Spokane River so that Garry could assume the position of chief of his tribe.

Return to Spokane

[edit]Upon their return to Spokane in the fall of 1829,[7] Garry passed on what he had learned at Fort Garry to both his people and to the neighboring peoples of the Columbia Plateau.[8] They returned to the mission the next spring, bringing five other students with them. In 1831 Garry was sent back to the West to notify the Kootenais of Pelly's death, which had taken place at Easter;[3] instead of returning to the Red River afterwards as expected, however, he travelled on to Spokane and never returned.[9]

Garry spent much of the next few years preaching his simple Anglican faith in the Columbia Plateau and teaching his people methods of agriculture which he had picked up at the Red River settlement.[10] He found that his new position within the tribal hierarchy created a stronger sense of duty to his people and a need to ensure their peaceful co-existence with white settlers. At this time he married a woman who he renamed Lucy.

In the 1840s the Spokanes were visited by a number of missionaries. Rev. Samuel Parker of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions was impressed by the piety of the peoples of the region, but other Protestant missionaries thought less highly of the Indians' typical activities, while Catholic missionaries were hostile to both. None were successful in converting the Spokanes to their denominations of Christianity.[3] However, the missionaries' denunciation of Spokane Garry's simple but "primitive"[3] faith was said to have lessened his reputation among the Christians and possibly among his people. His decision to take a second wife was also viewed negatively.

Later years

[edit]

In the mid-1840s Garry joined the first Walla Walla expedition. While there, the party found themselves short of trading goods and went into the mountains to hunt for hides. A white man named Grove Cook killed a young Christian member of the party named Toayahnu, who was the son of Piupiumaksmaks the chief of the Walla Wallas. The apparent unwillingness of the Indian agent at Walla Walla, Elijah White, to prosecute the crime enraged the Indians; tensions worsened after the Whitman Massacre of 1847. Garry, a wealthy man by the standards of his tribe, attempted to keep the peace between the two groups.[3]

On October 17, 1853, Garry met with Isaac Stevens, the newly appointed Governor of Washington Territory. Stevens later professed himself surprised that Garry could speak both English and French fluently, but also wrote that he found himself frustrated by Garry's unwillingness to speak frankly.

Two years later, Stevens summoned the Walla Walla, Nez Perce, Cayuse and Yakama tribes to negotiate a treaty, as well as asking Garry to attend as an observer. The chiefs agreed on a treaty and it seemed there would be peace, but soon the Yakama decided against allowing the whites to take their land and began to prepare for war against the United States. They recruited younger members of the Spokanes, but Garry was able to prevent his men from joining the impending battle. He could not stop the war, though, which began on September 23 with the deaths of several miners on the Yakima River and of A.J. Bolton, the special agent to the Yakamas.

When Stevens heard that war had broken out, he went immediately to the Spokane village and demanded to speak to Garry. The chiefs of the Coeur d'Alenes, the Spokanes, and Colvilles, as well as the leaders of the local French Canadian community were also in attendance. Stevens promised friendship, but asked the Spokanes to decide immediately between signing a treaty that would hand most of their land over to the whites or declaring war against the United States. He said in part:

I think it is best for you to sell a portion of your lands, and live on Reservations, as the Nez Perces and Yakimas agreed to do. I would advise you as a friend to do that... If you think my advice good, and we should agree, it is well. If you say, "We do not wish to sell," it is also good, because it is for you to say...

Garry made an impassioned speech itemizing all the grievances the Indians had and their unwillingness to give up their ancestral lands for the benefit of the whites. Stevens, finding himself unable to win the argument, retreated, and the Spokanes kept their lands.

In the following years Garry worked to keep the peace between the Spokanes and white settlers. His attempts to negotiate a new treaty with the territorial government were ignored; Stevens instead encouraged the Spokanes to abandon their traditional lands and take up individual ownership under the Indian Homestead Act of 1862. The Spokanes did not receive a reservation under the terms of the treaty they finally signed in 1887.

The final decade of Garry’s life was a sad one. Since 1863 Garry had occupied and farmed a 12–15-acre plot of land just east of the current Hillyard neighborhood in Spokane where he grew a variety of crops and raised his horses. In 1883 Garry's claim was jumped by German Settler Joseph Morscher, who threw poisoned meat over the fence, killing Garry's dogs and chasing away Garry's family. In 1886, Morscher sold the claim to Schuyler D. Doak, who had worked for Garry as a boy. When the claim became disputed in 1889, Doak quickly sold the claim (without clear title) to F. Lewis Clark, the wealthiest man in the region at the time. The illegal purchase of Garry's land (which Garry contested to many people) caught the attention of the Department of Interior, who sent a special investigator in late October 1891 to probe the issue. Special Investigator John W. Skiles determined that Schuyler Doak had committed fraud against Garry to rob him of his land. The investigator's report was sent to the Chief of the Indian Division, who then cherry-picked the report passing his conclusion that Doak should get the land along to the Assistant Attorney General George Shields and a final decision was rendered December 30, 1891; Garry lost!

While the first biographer of Garry[11] had claimed that the government records in the case had been destroyed- a claim echoed by all subsequent biographers of Garry since- these documents uncovered by anthropologist David K. Beine in 2018,[12] reveal many new details of the case as noted above. Further, the Skiles report uncovered by Beine reveals collusion in this fraud by Spokane’s founding father James Glover and several other leading citizens of the day. There was subsequent complicity in the fraud on the part of the Department of Interior’s Chief of the Indian Division J.C. Hill, who cherry-picked the investigator’s report, concluding in his commentary on the matter delivered to the Secretary of Interior, that Doak should be issued the patent to the land. Hill even twisted the evidence of notable founding citizen Reverend Henry T. Cowley, to make it appear that Cowley supported Doak when he actually defended Garry’s occupation of the land in his sworn testimony. Further complicity in the fraud and collusion in the case against Garry was then committed by the Assistant Attorney General of the United States, George W. Shields, who supplied the final decision on the matter. Shields, citing the seventh proviso in the Forest Reserve Act of 1891, concluded that since Doak had made a preemtive payment for the land and since within two years of the payment no valid protest contesting the entry had been brought forward, that by law Doak should be issued the patent to the land. While the Forest Reserve Act does contain this language, Shields conveniently omitted a single sentence that connects these two elements of the proviso. That missing single sentence reads, “…unless, upon an investigation by a Government Agent, fraud on the part of the purchaser has been found…” George Shields had John Skiles’ report in the documents forwarded to him, but conveniently chose to ignore the report of fraud filed by the US Special Investigator. The decision of the Assistant Attorney General of the United States was the final decision on the matter. The overall result? Garry lost his land and this once influential man, so significant to the founding the town of Spokane and the greater Pacific Northwest region, died soon afterward, a homeless and penniless pauper on January 13, 1892.

Legacy

[edit]In 1961 Dudley C. Carter created a carving of Garry on the site of St. Dunstan's Church of the Highlands in Shoreline, Washington in honor of a biography of Garry written by the then vicar of the congregation.

References

[edit]- ^ Drury (1936), p. 77

- ^ "S u l u s t u: Slough-Keetcha". 5 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Treaty Trail, Context for Treatymaking: Biography of Spokan Garry". Washington State Historical Society.

- ^ a b "One Prophecy." Spokane Outdoors.

- ^ Drury, p. 70

- ^ Beck Kehoe, p. 361

- ^ a b Drury (1976), p. 70

- ^ Josephy, p. 86

- ^ Drury (2005), p. 103

- ^ Drury (2005), p. 104

- ^ Lewis, William S. (1917). "The Case of Spokane Garry" (PDF).

- ^ Beine, David K. (2021). The Continuing Case of Spokane Garry. I Street Press. ISBN 9781952337512.

Sources

[edit]- Beck Kehoe, Alice (1981). North American Indians: A Comprehensive Account, Prentice-Hall, ISBN 0-13-623652-9.

- Beine, David K. (2021). Whodunnit? The Continuing Case of Spokane Garry. I Street Press, ISBN 9781952337512

- Drury, Clifford Merrill (1936). Henry Harmon Spalding, Caxton Printers, Ltd.

- Drury, Clifford Merrill; Walker, Elkanah (1976). Nine Years with the Spokane Indians: The Diary, 1838-1848, of Elkanah Walker, A. H. Clark Co., ISBN 0-87062-117-3.

- Drury, Clifford Merrill (2005). A Tepee in His Front Yard: A Biography of H. T. Cowley, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 1-4179-8380-9.

- Josephy, Alvin M.; Josephy, Alvin M. Jr. (1997). The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest, Houghton Mifflin Books, ISBN 0-395-85011-8.