Education in Morocco

The education system in Morocco comprises pre-school, primary, secondary and tertiary levels. School education is supervised by the Ministry of National Education, with considerable devolution to the regional level. Higher education falls under the Ministry of Higher Education and Executive Training.

School attendance is compulsory up to the age of 13. About 56% of young people are enrolled in secondary education, and 11% are in higher education. The government has launched several policy reviews to improve quality and access to education, and in particular to tackle a continuing problem of illiteracy. Support has been obtained from a number of international organisation such as USAID, UNICEF and the World Bank. A recent report after the new government being formed in 2017 has made Arabic as well as French Compulsory in Public School.

History[edit]

Islamic[edit]

In the year 859, Fatima al-Fihri established Al-Qarawiyiin mosque in Fes, and its associated madrasa is considered by some institutions such as UNESCO and Guinness World Records to be the oldest existing, continually operating higher educational institution in the world.[1][2] The Moroccan historian Mohamed Jabroun wrote that schools in Morocco were first built under the Almohad Caliphate (1121–1269).[3] For centuries, public education in Morocco took place primarily in madrasas and kuttabs (كُتَّاب)—or as they were called in Morocco, msids (مسيد).[4] Education at the msid was Islamic and delivered in Arabic.[4] In addition to teaching Quranic exegesis (tafseer) and Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh), Islamic schools often taught a wide variety of subjects, including literature, science and history.[5] The Marinids founded a number of these schools,[6] including those in Fes, Meknes, and Salé, while the Saadis expanded the Ben Youssef Madrasa in Marrakesh.

Jewish[edit]

In the aftermath of the sacking of the mellah of Tetuan in the Hispano-Moroccan War, the Alliance Israélite Universelle, a French organization working to empower Jews around the world through a French education, founded its first school in Tetuan in 1862, followed by schools in Tangier (1864), Essaouira (1866), and Asfi (1867), eventually reaching a total of 83 schools—more than all of the AIU's schools in the rest of the world.[7][8][9]

Before the French Protectorate, Jewish girls' schools were teaching reading and writing, as well as vocational workplace training through skills such as tailoring and laundering, and later reading, writing, and shorthand.[8] In 1913, the French authorities replicated this system for Muslim girls in Salé and later other cities.[8]

French Protectorate[edit]

Following the Treaty of Fes of 1912 and the establishment of the French Protectorate, France established public schools in which education was delivered in French.[4]

Protectorate officials were hesitant about education for general public, afraid that an educated populace would become a source of opposition to the colonial regime.[10] Resident General Hubert Lyautey's elitism shaped the educational system under the French Protectorate, and access to a modern education depended on a student's ethnicity and class, with separate educational opportunities for Europeans, Jews, and Muslims.[10] Only a percentage of the children attending school were Muslim, and of these, most attended the traditional Quranic schools, or msids, which were beyond the purview of the Protectorate.[10] Most Muslim students studying within the Protectorate's educational system received a vocational education to work in various manual trades.[10]

Five schools for the "sons of notables" were established after 1916 for boys from elite Moroccan families.[10] There were also two collèges founded in Fes (1914) and Rabat (1916).[10] These boarding schools, which Susan Gilson Miller likens to Eton College, served to create Lyautey's vision for a class of bicultural Moroccan "gentlemen"—imbued with traditional ideals yet efficient in navigating modern bureaucratic systems—to fill roles in the country's administration.[10]

In 1920, Lyautey founded the Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines, located within the Bibliothèque Générale next to the colonial headquarters in Rabat, for colonial administrators who wanted to learn more about Moroccan history and society.[10]

After 1920, French instituteurs, who were rigorously prepared in an Amazigh dialect and trained as teachers and intelligence gatherers, were assigned to schools in rural areas for speakers of Amazigh languages.[10] The Collège d'Azrou, one of these schools that was developed into a collège, was one of the instruments for the implementation of a Berber Dhahīr[10] and to "help form an Amazigh elite that would help France implement its divide and rule policies."[11] It trained its Amazigh students for high roles in the colonial administration, as well as forming "a Berber elite steeped in French culture, in an environment where Arabic influences were rigorously excluded."[10][12] This hierarchical educational system was designed to "guarantee an indigenous elite loyal to France and ready to enter its service," though its permeability in practice made it a "vehicle of social mobility."[10]

The inadequacies of traditional education at the msid became apparent, and private Moroccan citizens, particularly of the bourgeois merchant class, started to found what would later become known as "free schools"—with modernized curricula and instruction in Arabic—independently of each other.[4] The teaching quality at these free schools varied greatly, from "uninspiring fqîhs, scarcely removed from their msîds" to "the country's most distinguished and imaginative 'ulamâ."[4] Many of the young teachers in Fes were simultaneously taking classes at al-Qarawiyyin University, and several would go on to lead the Moroccan Nationalist Movement.[4]

Independence[edit]

In the 44-year period of the French Protectorate, a total of only 1415 Moroccans had earned baccalaureate diplomas, 640 of whom were Muslims and 775 of whom were Jews.[10] Additionally, under the Protectorate, only 15% of school-age children were in school.[10] It was necessary to develop the educational system and a university network out of the limited resources left by the French in order to face the challenges awaiting the newly independent nation-state, such as "creating and consolidating state institutions, building a national economy, organizing civil society and the nascent political parties, [and] establishing social protections for a needy population."[10]

Arabization became an imperative. Ahmed Boukmakh published Iqra' (اِقْرَأ, "Read"), the first series of Arabic textbooks in Morocco, in 1956, 1957, and 1958.[13][14] In 1957, Muhammad al-Fasi attempted to Arabize first grade, but this attempt was not successful.[15] The Institute for Studies and Research on Arabization was established in 1960 and the first Congress of Arabization was held in Rabat in 1961.[15][16]

The Cultural Agreement of 1957, signed by the Moroccan and French governments, allowed for the continuation of French education in Morocco administered by a body known as the Mission universitaire et culturelle française au Maroc (which was replaced by AEFE in 1990).[17][18]

In 1958, Muhammad al-Fasi's successor, Abdelkarim Ben Jelloun, established a blueprint for education reform in four goals:

- unify the traditional and modern systems

- Arabize all subjects

- generalize literacy

- Moroccanize, i.e. train nationals to replace foreign teachers[15]

It was in 1963 that education was made compulsory for all Moroccan children between the ages of 6 through 13[19] and during this time all subjects were Arabized in the first and second grades, while French was maintained as the language of instruction of maths and science in both primary and secondary levels.

In 1965, demanding the right to public higher education for Moroccans, the National Union of Moroccan Students (الاتحاد الوطني لطلبة المغرب, UNEM) organized a march starting from Muhammad V Secondary School in Casablanca, which devolved the following day into the 1965 Moroccan riots.[20] King Hassan II blamed the events on teachers and parents, and declared: "Allow me to tell you that there is no greater danger to the State than a pseudo-intellectual, and you are pseudo-intellectuals. It would have been better if you were all illiterate.”[21][22] In the aftermath, teachers were persecuted.[23]

Under Hassan II, the Institute of Sociology (معهد السوسيولوجيا) run by Abdelkebir Khatibi was dissolved in 1970.[24] In 1973, the humanities at government-controlled universities were Arabized, in which the Istiqlal leader Allal al-Fassi played a major role,[25] and curricula were substantially changed. Arabization was instrumentalized to suppress critical thought,[24] a move which Dr. Susan Gilson Miller described as a "crude and obvious attempt to foster a more conservative atmosphere within academia and to dampen enthusiasm for the radicalizing influences filtering in from Europe."[26] The Minister of Education Azzeddine Laraki, following a report conducted by a committee of four Egyptians including two from al-Azhar University, replaced sociology with Islamic thought in 1983.[24]

To meet the rising demand for secondary education in the 1970s, Morocco imported French speaking teachers from countries such as France, Romania, and Bulgaria to teach maths and sciences, and Arab teachers to teach humanities and social studies.

A 1973 article in Lamalif described Moroccan society as broken and fragmented, with misdirected energy from a discouraged and ashamed elite contributing to low standards of education.[27]

By 1989, Arabization of all subjects across all grades in both primary and secondary public education was accomplished. However, French remained the medium of instruction for scientific subjects in technical and professional secondary schools, technical institutes and universities.[28]

The government has undertaken several reforms to improve the access of education and reduce regional differences in the provision of education. In 1999, King Mohammed VI announced the National Charter for Education and Training (الميثاق الوطني للتربية و التكوين).[29][30] In the same year, a committee for education was established with the goal of reforming the educational system in Morocco.[31] On July 15, 2002, decree number 2.02.382 established the Ministry of National Education, Early Education, and Athletics.[31]

The King announced the period between 1999 and 2009 as the "Education Decade." During this time the government's reform initiative focused on five main themes to facilitate the role of knowledge in economic development; the key themes were education, governance, private sector development, e-commerce and access. The World Bank and other multilateral agencies have helped Morocco to improve the basic education system.

Under Said Amzazi, Morocco passed the framework-law 51.17 summer 2019.[32]

French schools[edit]

To this day, French schools—which are colloquially referred to as "la mission," whether they're actually related to the Mission Laïque Française or not—still have a major presence in Morocco. In these schools, French is the language of instruction, and Arabic is only taught as a second language if at all.[33]

The schools are certified by the Agency for French Education Abroad, and administered by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the student body is typically composed of the children of Morocco's elite and well-to-do classes.[33] These schools, such as Lycée Lyautey in Casablanca, are typically located in big cities such as Casablanca, Rabat, Fes, Marrakesh, Meknes, and Oujda.[34]

France is the number 1 destination for Moroccan students leaving the country to study abroad, receiving 57.7% of all Moroccans studying outside of Morocco. Moroccan students also represent the largest group of foreign students in France, at 11.7% of all international students at universities in France, according to a 2015 UNESCO study.[35]

Structure of the education system[edit]

The education system in Morocco comprises pre-school, primary, secondary and tertiary levels. Government efforts to increase the availability of education services have led to increased access at all levels of education. Morocco's education system consists of 6 years of primary, 3 years of lower-middle / intermediate school, 3 years of upper secondary, and tertiary education.

The education system is under the purview of the Ministry of National Education (MNE) and Ministry of Higher Education and Executive Training. The Ministry of National Education decentralized its functions to regional levels created in 1999 when 72 provinces were subsumed into 12 regional administrative units. Then the responsibility of the provision of education services has been slowly devolving to the regional level. This decentralization process will ensure that education programs are responsive to regional needs and the budget is administered locally. Each region has a Regional Academy for Education and Training and a regional director who is senior to provincial delegates within the region. The regional academies will also be responsible for developing 30 percent of the curriculum so that it is locally relevant. The central level of the MNE continues to manage the other 70 percent.[36] Also the delegations are charged with providing services for education in their regions.[37]

Pre-school[edit]

According to the National Charter, preprimary education is compulsory and available to all children under the age of 6. This level is open to children of ages 4–6 years old. There are two types of pre-primary schools in Morocco: kindergarten and Quranic schools. The kindergarten is a private school that provides education mainly in cities and towns; the Quranic schools prepare children for primary education by helping them develop basic literacy and numeracy skills. Quranic schools have the potential to become a major force in the fight against illiteracy. (timss)with approximately 80 percent of all children attending some form of Quranic school for some portion of their school years.[36] In 2007 the gross enrollment rate of pre-primary students in Morocco was about 60 percent, with the GER of males being 69.4 percent and that for females 49.6 percent. The GER for females have been increasing since the past few years and for the males it has been about 69 percent since 2003.[38]

Primary[edit]

The primary education consists of 6 years for children of ages 6–12 years old. Students are required to pass Certificat d'etudes primaires to be eligible for admission in lower secondary schools.[37]

The gross enrollment rates (GER) at the primary level have been consistently rising in the 2000s. In 2007 the total GER at the primary level was 107.4 percent, with 112 percent for males and 101 percent for females. But the Gender Parity Index for GER was 0.89, which shows that the issue of gender inequality persists at the primary level. The repetition rate at the primary level is 11.8 percent; the repetition rate for males at the primary level is 13.7 percent and for females it is 9.7 percent and the rates are declining for the past few years for both genders. The dropout rate at the primary level in 2006 was 22 percent, and is slightly higher for girls than boys, at 22 and 21 percent respectively.[38] The dropout rates have been falling since 2003, but is still very high compared to other Arab countries, such as Algeria, Oman, Egypt and Tunisia.[39]

Secondary[edit]

There are three years of lower-middle school. This type of education is provided through what is referred to as the Collège. After 9 years of basic education, students begin upper secondary school and take a one-year common core curriculum, which is either in arts or science. First year students take arts and or science, mathematics or original education. Second year students take earth and life sciences, physics, agricultural science, technical studies or are in A or B mathematics track.

The gross enrollment rate (GER) at the secondary level in 2007 was 55.8 percent. But in secondary education the grade repetition and drop-out rates especially remain high.[40] The gender parity index for GER at secondary level was 0.86 in 2007; it is not better than other Arab countries and reflects considerable disparity between genders in enrollment at the secondary level.

Tertiary[edit]

Source:[41]

The higher education system consists of both private and public institutes. The country has fourteen major public universities,[37] including Mohammed V University in Rabat and Al-Karaouine University, Fes,[42] along with specialist schools, such as the music conservatories of Morocco supported by the Ministry of Culture. The Karaouine University at Fes has been teaching since 859, making it the world's oldest continuously operating university.[43] However, there are dozens of national and international universities like SIST British University that work along with the public universities to improve the higher education in Morocco. In addition, there are a large number of private universities. The total number of graduates at the tertiary level in 2007 was 88,137: the gross enrollment rate at the tertiary level is 11 percent and it has not fluctuated significantly in the past few years.[39] Admission to public universities requires only a baccalauréat, whereas admission to other higher public education, such as engineering school, require competitive special tests and special training before the exams.

Another growing field apart from engineering and medicine is business management. According to the Ministry of Education the enrollment in Business Management increased by 3.1 percent in the year 2003-04 when compared to preceding year 2002–2003. Generally, an undergraduate business degree requires three years and an average of two years for master's degree.[44]

Universities in Morocco have also started to incorporate the use of information and communication technology. A number of universities have started providing software and hardware engineering courses as well; annually the academic sector produces 2,000 graduates in the field of information and communication technologies.[45]

Moroccan institutions have established partnerships with institutes in Europe and Canada and offer joint degree programs in various fields from well-known universities.[44]

To increase public accountability, the Moroccan universities have been evaluated since 2000, with the intention of making the results public to all stakeholders, including parents and students.[28]

Results in the education sector[edit]

Private higher education institutes[edit]

Despite having a number of private institutes the enrollment in private higher education institutes is still low, less than 3.5 percent of total university population. Private institutes also suffer from less qualified or inadequate staff. This is primarily due to inhibiting tuition costs. Curriculum of especially the business schools is outdated and needs to be revised according to the changing demands of the labor market. Private sector companies also do not make sufficient contribution in providing working knowledge to professional institutes of the current business environment.[44]

Access to school education[edit]

Internal efficiency is also low with high dropout and repetition rates. There is also an unmet need of rising demand of middle schools after achieving high access rates in primary education.[46] The problem is more acute in the rural schools due to inadequate supply and quality of instructional materials. The poor quality of education becomes an even greater problem due to Arabic-Berber language issues: most of the children from Berber families hardly know any Arabic, which is the medium of instruction in schools, when they enter primary level.[36]

Literacy[edit]

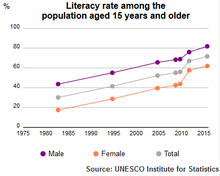

The Maghreb region has high rates of literacy. In Morocco, the adult literacy rate is still high at around 74 percent in 2018, thanks to concerted efforts being made since independence in 1956 to reduce the rate of illiteracy which at that time was 32 percent. Morocco is the 16 most literate in the Arab countries.

Immigration[edit]

There has also been a high immigration rate of skilled workers, that is, the proportion of highly skilled emigrants among educated people is high. In this way Morocco is losing a substantial proportion of its skilled work force to foreign countries, forming the largest migrant population among North Africans in Europe.[28]

Reform efforts[edit]

Literacy[edit]

Since the late 1980s the Maghreb countries’ governments have been partnering with civil society organizations to fight illiteracy. The NGO Programme launched in 1988 delivers literacy to 54% of all learners enrolled in adult literacy programmes. Ministerial and General Programme also focus on various ministries and community to deliver literacy programmes. In-Company programmes cater to the needs of the working population focused on continuous in-company training.[47] Morocco and other Maghreb countries are now fully committed to eradicate illiteracy. Morocco officially adopted its National Literacy and Non-formal Education Strategy in 2004. An integrated vision of literacy, development and poverty reduction was promoted by National Initiative for Human Development (INDH), launched by the King Mohammed VI in May 2005.[47]

Government reviews[edit]

Improving the quality of outcomes in the education sector has become a key priority for Morocco's government. A comprehensive renovation of the education and training system was developed in a participatory manner in 1998–99, which led to the vision for long-term expansion of this sector in response to the country's social and economic development requirements.[48] The outcome was the promulgation of the 1999 National Education and Training Charter (CNEF). The CNEF, with strong national consensus, declared 2000-2009 the decade for education and training, and established education and training as a national priority, second only to territorial integrity. The reform program, as laid out by the CNEF, also received strong support from the donor community. Nevertheless, during the course of implementation, the reform program encountered delays.

In 2005 the Moroccan government adopted a strategy with the objective of making ICT accessible in all public schools to improve the quality of teaching; infrastructure, teacher training and the development of pedagogical content was also part of this national programme.[45] In August 2019, the government passed a law to commence reforms on education including teaching science subjects in French language.[49] In 2021, many series of campaign were done by the Moroccans to remove the French language and to replace it with the English language as a secondary language.[50][51][52][53] Which later was announced no change would be made regarding the French language.[54]

External bodies[edit]

A number of donors including USAID and UNICEF are implementing programs to improve the quality of education at the basic level and to provide training to teachers. The World Bank also provides assistance in infrastructure upgrades for all levels of education and offer skill development trainings and integrated employment creation strategies to various stakeholders.[36] At the request of the Government's highest authorities, a bold Education Emergency Plan (EEP) was drawn up to catch up on this reform process. The EEP, spanning the period 2009–12, draws on the lessons learned during the last decade. In this context, the Government requested five major donors (European Union (EU), European Investment Bank (EIB), Agence française de développement (AFD), African Development Bank (AfDB) and the World Bank) to assist the implementation of the EEP reform agenda.[55]

References[edit]

- ^ Oldest University

- ^ "Medina of Fez". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ "تاريخ المغرب الأقصى، من الفتح الإسلامي إلى الاحتلال". www.goodreads.com. Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Damis, J. (1975). "The origins and signifiance of the free school movement in Morocco, 1919-1931". Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée. 19 (1): 75–99. doi:10.3406/remmm.1975.1314.

- ^ "IBN YUSUF MADRASA in Marrakesh, Morocco". www.ne.jp. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ^ Meri, Josef W. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-96690-0.

- ^ Rodrigue, Aron (2003). Jews and Muslims: Images of Sephardi and Eastern Jewries in Modern Times. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98314-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Miller, Susan Gilson (2013). A History of Modern Morocco. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 45. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139045834. ISBN 978-1-139-04583-4.

- ^ Emily Gottreich, The Mellah of Marrakesh: Jewish and Muslim Space in Morocco's Red City, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007, 9

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-62469-5. OCLC 855022840.

- ^ Gottreich, Emily (2020). Jewish Morocco. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78076-849-6.

- ^ Young, Crawford (1979). The Politics of Cultural Pluralism. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-06744-1.

- ^ Yabiladi.com. "Ahmed Boukmakh, the teacher behind Morocco's first Arabic-language textbooks". en.yabiladi.com. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- ^ "أحمد بوكماخ .. من المسرح والسياسة إلى تأليف سلسلة "اقرأ"". Hespress (in Arabic). Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Alalou, Ali (2006). "Language and Ideology in the Maghreb: Francophonie and Other Languages". The French Review. 80 (2): 408–421. ISSN 0016-111X. JSTOR 25480661.

- ^ UNESCO (2019-12-31). بناء مجتمعات المعرفة في المنطقة العربية (in Arabic). UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-600090-9.

- ^ "Mission universitaire et culturelle française au Maroc". data.bnf.fr. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- ^ Castagnos, Jean-Claude (1973). "Aspects socio-économiques de la coopération culturelle française au Maroc". Revue française de pédagogie. 22 (1): 36–41. doi:10.3406/rfp.1973.1825.

- ^ Diyen, Hayat 2004,"reform of secondary education in Morocco: Challenges and Prospects." Prospects, vol XXXIV.no.2,pp212

- ^ Miller, A History of Modern Morocco (2013), pp. 162–168–169.

- ^ "لماذا كان الحسن الثاني لا يحب المثقفين؟". مغرس (in Arabic). Retrieved 2020-04-20.

أقول لكم انه لا خطر على أي دولة من الشبيه بالمثقف ، وأنتم أشباه المثقفين ..وليتكم كنتمْ جُهّالا

- ^ Susan Ossman, Picturing Casablanca: Portraits of Power in a Modern City; University of California Press, 1994; p. 37.

- ^ "مقالات . .انتفاضة 23 مارس 1965". مغرس. Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "هكذا قضى الحسن الثاني على الفلسفة". تيل كيل عربي (in Arabic). Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- ^ "تاريخ.. عندما وجه علال الفاسي نداءا من أجل التعريب عام 1973" (in Arabic). Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- ^ Miller, Susan Gilson, A History of Modern Morocco, Cambridge University Press, p. 170, ISBN 978-1-139-04583-4

- ^ "Le dossier de l'arabisation". Lamalif. 58: 14. April 1973.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "MENA Flagship Report. "The Road Not Traveled: Education Reforms in MENA."". World Bank, Washington, DC. 2008.

- ^ "الميثاق الوطني للتربية و التكوين". www.men.gov.ma. Retrieved 2022-08-10.

- ^ "Charte Nationale d'Education et de Formation". www.men.gov.ma. Retrieved 2022-08-10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "تقديم حول هيكلة الوزارة". www.men.gov.ma. Retrieved 2022-08-10.

- ^ "Enseignement : La loi-cadre adoptée à la chambre des représentants". Telquel.ma (in French). Retrieved 2022-08-10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ennaji, Moha (2005-01-20). Multilingualism, Cultural Identity, and Education in Morocco. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 37. ISBN 9780387239798.

- ^ Ennaji, Moha (2005-01-20). Multilingualism, Cultural Identity, and Education in Morocco. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 106. ISBN 9780387239798.

- ^ "Campus France Chiffres Cles August 2018" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-09-17. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Strengthening Education in the Muslim World: Country Profile and Analysis (pp18)" (PDF). USAID. 2004.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c TIMSS encyclopedia 2007

- ^ Jump up to: a b UNESCO Institute of Statistics, 2008

- ^ Jump up to: a b "World Bank 2009.Edstats".

- ^ Morocco: challenges to tradition and modernity - Page 58 James N. Sater - 2009 "In addition to high drop-out rates at Morocco's public universities, this indicates that a growing proportion of Morocco's young population received religious education, but was unable to work in the religious sector. ..."

- ^ "Morocco Academia | moroccodemia English, Arabic and French". moroccodemia. Retrieved 2018-10-02.

- ^ Morocco Country Study Guide - Page 23 IBP USA - 2006 "Morocco is home to 14 public universities. Mohammed V University in Rabat is one of the country's most famous schools, with faculties of law, sciences, liberal arts, and medicine. Karaouine University, in Fes, is a longstanding center ...

- ^ The Report: Morocco 2009 - Page 252 Oxford Business Group "... yet for many Morocco's cultural, artistic and spiritual capital remains Fez. The best-preserved ... School has been in session at Karaouine University since 859, making it the world's oldest continuously operating university. ..."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Driouchi, Ahmed (2006), A Global Guide to Management Education

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hamdy, Amr (June 2007). "Survey of ICT and Education in Africa: Egypt Country Report. ICT in Education in Morocco".

- ^ "World Bank 2005. "Basic Education Reform Support Program." Project Appraisal Document. World Bank, Washington, DC" (PDF).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Literacy Policies and Strategies in the Maghreb: Comparative Perspectives from Algeria, Mauritania and Morocco. Research paper prepared for the UNESCO Regional Conferences in Support of Global Literacy, United Nations, 2007

- ^ "Kingdom of Morocco Policy Notes, Conditions for Higher and Inclusive Growth (pp215), Ch 11" (PDF). World Bank, Washington, DC. 2008.

- ^ "Moroccan parliament passes law on education reform". The North Africa Post. 2019-07-23. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

- ^ Staff writer. "Moroccans demand English replace French as country's first foreign language". the new Arab. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ CMS, ES. "Is Morocco Ready to Get Rid of French Cultural Colonization?". Al-Estiklal Newspaper. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ "Morocco campaign to adopt English instead of French". Middle East Monitor. 2021-09-21. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ "Moroccans want English to replace French as country's first official foreign language". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ Anouar, Souad. "Morocco Refutes Rumors about Replacing French in Education". Morocco world news. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "EEP". Ministry of National Education. Archived from the original on 2010-02-17. Retrieved 2010-02-25.