Nazi euthanasia and the Catholic Church

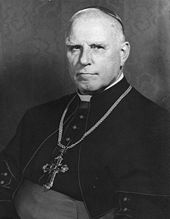

During the Second World War, the Roman Catholic Church protested against Aktion T4, the Nazi involuntary euthanasia programme under which 300,000 disabled people were murdered. The protests formed one of the most significant public acts of Catholic resistance to Nazism undertaken within Germany. The "euthanasia" programme began in 1939, and ultimately resulted in the murder of more than 70,000 people who were deemed senile, mentally handicapped, mentally ill, epileptics, cripples, children with Down's Syndrome, or people with similar afflictions. The murders involved interference in Church welfare institutions, and awareness of the murderous programme became widespread. Church leaders who opposed it – chiefly the Catholic Bishop Clemens August von Galen of Münster and Protestant Bishop Theophil Wurm – were therefore able to rouse widespread public opposition.

Catholic protests began in the summer of 1940. The Holy See declared on 2 December 1940 that the policy was contrary to natural and positive Divine law, and that: "The direct killing of an innocent person because of mental or physical defects is not allowed." In the summer of 1941, protests were led in Germany by Bishop von Galen, whose intervention, according to Richard J. Evans, led to "the strongest, most explicit and most widespread protest movement against any policy since the beginning of the Third Reich."[2] In 1943, Pope Pius XII issued the Mystici corporis Christi encyclical, in which he condemned the practice of killing the disabled. The Encyclical was followed, on 26 September 1943, by an open condemnation from the German Bishops which denounced the killing of innocent and defenceless people, whether mentally or physically handicapped, incurably infirm, fatally wounded, innocent hostages, disarmed prisoners of war, criminal offenders, or belonging to a different race.

Aktion T4

[edit]While the Nazi "Final Solution" murder of the Jews took place primarily on German-occupied Polish territory, the murder of people deemed invalids took place on German soil and involved interference in Catholic (and Protestant) welfare institutions. Awareness of the murderous programme therefore became widespread, and the Church leaders who opposed it – chiefly the Catholic Bishop of Münster, Clemens August von Galen, and Dr Theophil Wurm, the Protestant Bishop of Württemberg – were therefore able to rouse widespread public opposition.[3] The intervention has been said to be "the strongest, most explicit and most widespread protest movement against any policy since the beginning of the Third Reich."[2]

From 1939, the regime began its programme of euthanasia, under which those deemed "racially unfit" or "life unworthy of life" were to be euthanized.[4] Those deemed by the Nazis to be senile, mentally handicapped and mentally ill, epileptics, cripples, children with Down's Syndrome and people with similar afflictions were all to be killed.[5] The programme ultimately involved the systematic murder of more than 70,000 people.[4] Among those murdered was a cousin of the young Joseph Ratzinger, future Pope Benedict XVI.[6]

By the time the Nazis commenced their programme of killing invalids, the Catholic Church in Germany had been subject to prolonged persecution from the state, and had suffered confiscation of property, arrest of clergy, and closure of lay organisations. The Church hierarchy was therefore wary of challenging the regime, for fear of further consequences for the Church. However, on certain matters of doctrine they remained unwilling to compromise.[7]

Catholic protest

[edit]The Papacy and German bishops had already protested against the Nazi sterilization of the "racially unfit". Catholic protests against the escalation of this policy into "euthanasia" began in the summer of 1940. Despite Nazi efforts to transfer hospitals to state control, large numbers of disabled people were still under the care of the Churches. Caritas was the chief organisation running such care services for the Catholic Church. After Protestant welfare activists took a stand at the Bethel Hospital in August von Galen's diocese, Galen wrote to Germany's senior cleric, Cardinal Adolf Bertram, in July 1940 urging the Church to take the moral position. Bertram urged caution. Archbishop Conrad Groeber of Freiburg wrote to the head of the Reich Chancellery, and offered to pay all costs being incurred by the state for the "care of mentally ill people intended for death." Caritas directors sought urgent direction from the bishops, and the Fulda Bishops Conference sent a protest letter to the Reich Chancellery on 11 August, then sent Bishop Heinrich Wienken of Caritas to discuss the matter. Wienken cited the commandment "thous shalt not kill" to officials and warned them to halt the program or face public protest from the Church. Wienken subsequently wavered, fearing a firm line might jeopardise his efforts to have Catholic priests released from Dachau, but was urged to stand firm by Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber. The government refused to give a written undertaking to halt the program, and the Vatican declared on 2 December that the policy was contrary to natural and positive Divine law.[8]

Bishop von Galen had the decree printed in his newspaper on 9 March 1941. Subsequent arrests of priests and seizure of Jesuit properties by the Gestapo in his home city of Munster, convinced Galen that the caution advised by his superior had become pointless. On 6, 13 and 20 July 1941, Galen spoke against the seizure of properties and the expulsions of nuns, monks, and the religious, and criticised the "euthanasia" programme. In an attempt to cow Galen, the police raided his sister's convent, and detained her in the cellar. She escaped the confinement and Galen, who had also received news of the imminent removal of further patients, launched his most audacious challenge on the regime in a 3 August sermon. He declared the murders to be illegal and said that he had formally accused those responsible for murders in his diocese in a letter to the public prosecutor. The policy opened the way to the murder of all "unproductive people", like old horses or cows, including disabled war veterans. He asked "Who can trust his doctor anymore?" He declared, wrote Evans, that Catholics must "avoid those who blasphemed, attacked their religion, or brought about the death of innocent men and women. Otherwise they would become involved in their guilt."[9] Galen said that it was the duty of Christians to resist the taking of human life, even if it meant losing their own lives.[10]

In 1941, with the Wehrmacht still marching on Moscow, Galen, despite his long-time nationalist sympathies, denounced the lawlessness of the Gestapo, the confiscations of church properties, and the Nazi "euthanasia" programme.[4] He attacked the Gestapo for converting church properties to their own purposes – including use as cinemas and brothels.[5] He protested against the mistreatment of Catholics in Germany: the arrests and imprisonment without legal process, the suppression of monasteries, and the expulsion of religious orders. But his sermons went further than defending the church, he spoke of a moral danger to Germany from the regime's violations of basic human rights: "the right to life, to inviolability, and to freedom is an indispensable part of any moral social order", he said – and any government that punishes without court proceedings "undermines its own authority and respect for its sovereignty within the conscience of its citizens".[11] Galen said that it was the duty of Christians to resist the taking of human life, even if it meant losing their own lives.[12]

Reaction

[edit]"The sensation created by the sermons", wrote Evans, "was enormous".[2] Kershaw characterised Von Galen's 1941 "open attack" on the government's "euthanasia" program as a "vigorous denunciation of Nazi inhumanity and barbarism."[13] According to Gill, "Galen used his condemnation of this appalling policy to draw wider conclusions about the nature of the Nazi state.[5] He spoke of a moral danger to Germany from the regime's violations of basic human rights.[11] Galen had the sermons read in parish churches. The British broadcast excerpts over the BBC German service, dropped leaflets over Germany, and distributed the sermons in occupied countries.[2] Following the war, Pope Pius XII proclaimed von Galen a hero and promoted him to Cardinal.[14]

There were demonstrations across Catholic Germany.[6] Hitler himself faced angry demonstrators at Hof, near Nuremberg, where he stepped out of his train at a local station while another train loaded mentally disabled patients to be taken away and a crowd that had gathered openly jeered at Hitler;[15][16] this was the only time he was directly and openly confronted with such resistance by ordinary Germans.[17][6] The regime did not halt the murders, but took the program underground.[18] Bishop Antonius Hilfrich of Limburg wrote to the Justice Minister, denouncing the murders. Bishop Albert Stohr of Mainz from the pulpit condemned the taking of life. Some of the priests who distributed the sermons were among those arrested and sent to the concentration camps amid the public reaction to the sermons.[2] Bishop von Preysing's Cathedral Administrator, Bernhard Lichtenberg, met his demise for protesting directly to Dr Conti, the Nazi State Medical Director. On 28 August 1941, he endorsed Galen's sermons in a letter to Conti, pointing to the German constitution which defined euthanasia as an act of murder. He was arrested soon after and later died en route to Dachau.[19]

Hitler wanted to have Galen removed, but Goebbels told him this would result in the loss of the loyalty of Westphalia.[5] The regional Nazi leader and Hitler's deputy Martin Bormann called for Galen to be hanged, but Hitler and Goebbels urged a delay in retribution till war's end.[20] In a 1942 Table Talk Hitler reportedly said: "The fact that I remain silent in public over Church affairs is not in the least misunderstood by the sly foxes of the Catholic Church, and I am quite sure that a man like Bishop von Galen knows full well that after the war I shall extract retribution to the last farthing."[21]

With the programme now public knowledge, nurses and staff (particularly in Catholics institutions) increasingly sought to obstruct implementation of the policy.[22] Under pressure from growing protests, Hitler halted the T4 programme on 24 August 1941, though less systematic murder of disabled people continued.[23] The techniques learnt from Aktion T4 were later transferred for use in the Holocaust.[24]

1942 Pastoral Letter

[edit]In the United States, the National Catholic Welfare Conference reported that the German Catholic bishops jointly expressed their "horror" at the policy in their 1942 Pastoral Letter:[25]

Every man has the natural right to life and the goods essential for living. The living God, the Creator of all life, is sole master over life and death. With deep horror Christian Germans have learned that, by order of the State authorities, numerous insane persons, entrusted to asylums and institutions, were destroyed as so-called "unproductive citizens." At present a large-scale campaign is being made for the killing of incurables through a film recommended by the authorities and designed to calm the conscience through appeals to pity. We German Bishops shall not cease to protest against the killing of innocent persons. Nobody's life is safe unless the Commandment "Thou shalt not kill" is observed.

Mystici corporis Christi

[edit]In 1943, Pope Pius XII issued the encyclical Mystici corporis Christi, in which he condemned the practice of killing the disabled. He stated his "profound grief" at the murder of the deformed, the insane, and those suffering from hereditary disease... as though they were a useless burden to Society," in condemnation of the ongoing Nazi "euthanasia" program. The Encyclical was followed, on 26 September 1943, by an open condemnation from the German Bishops which, from every German pulpit, denounced the killing of "innocent and defenceless mentally handicapped, incurably infirm and fatally wounded, innocent hostages, and disarmed prisoners of war and criminal offenders, people of a foreign race or descent."[26] Paragraph 94 of Mystici corporis Christi reads:[27]

For as the Apostle with good reason admonishes us: "Those that seem the more feeble members of the Body are more necessary; and those that we think the less honorable members of the Body, we surround with more abundant honour." Conscious of the obligations of Our high office We deem it necessary to reiterate this grave statement today, when to Our profound grief We see at times the deformed, the insane, and those suffering from hereditary disease deprived of their lives, as though they were a useless burden to Society; and this procedure is hailed by some as a manifestation of human progress, and as something that is entirely in accordance with the common good. Yet who that is possessed of sound judgment does not recognize that this not only violates the natural and the divine law written in the heart of every man, but that it outrages the noblest instincts of humanity? The blood of these unfortunate victims who are all the dearer to our Redeemer because they are deserving of greater pity, "cries to God from the earth."

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gill, Anton (1994). An Honourable Defeat; A History of the German Resistance to Hitler. London: Heinemann. p. 265.

- ^ a b c d e Evans, Richard J. (2009). The Third Reich at War. New York City: Penguin Press. p. 98.

- ^ Peter Hoffmann; The History of the German Resistance 1933-1945; 3rd Edn (First English Edn); McDonald & Jane's; London; 1977; p.24

- ^ a b c "Blessed Clemens August, Graf von Galen". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2015.

- ^ a b c d Gill (1994), p. 60

- ^ a b c Schnitker, Harry (3 October 2011). "The Church and Nazi Germany: Opposition, Acquiescence and Collaboration II". Catholic News Agency. Inside the Church during WWII. Denver, Colorado, United States: EWTN.

- ^ Evans (2009), p. 95.

- ^ Evans (2009), pp. 95–7.

- ^ Evans (2009), pp. 97–8.

- ^ Michael Berenbaum (2008). "T4 Program". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ a b Hamerow, Theodore S. (1997). On the Road to the Wolf's Lair: German Resistance to Hitler. Belknap Press (Harvard University Press). p. 289-90. ISBN 0-674-63680-5.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica's Reflections on the Holocaust

- ^ Ian Kershaw; The Nazi Dictatorship: Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation; 4th Edn; Oxford University Press; New York; 2000"; pp. 210–11

- ^ AFP (18 November 2004). "Pope to Beatify German Anti-Nazi Bishop". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ Sereny, Gitta (2011) [1974]. "Part III". Into That Darkness: An Examination of Conscience (3rd ed.). New York City, New York, United States: Random House. p. 70. ISBN 9780307761064 – via Google Books.

- ^ Lifton, Robert Jay (1986). "3. Resistance to Direct Medical Killing". The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide. New York City, New York, United States: Basic Books. p. 95. ISBN 9780465049042. OCLC 13334966.

- ^ Sweeney, Kevin P. Gilbert, Tommy; Florio, Emma; Johnson, Hannah (eds.). "We Will Never Speak of It: Evidence of Hitler's Direct Responsibility for the Premeditation and Implementation of the Nazi Final Solution" (PDF). Constructing the Past. 13 (1). Bloomington, Illinois, United States: Illinois Wesleyan University: Article 7 – via Digital Commons @ IWU.

- ^ Phayer, Michael. The Response of the German Catholic Church to National Socialism (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Gill (1994), p. 61.

- ^ Evans (2009), p. 99.

- ^ Hitler's Table Talk 1941–1944, Cameron & Stevens, Enigma Books pp. 90, 555.

- ^ Evans (2009), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Fulbrook, Mary (1991). The Fontana History of Germany: 1918-1990 The Divided Nation. Fontana Press. pp. 104–5. ISBN 9780006861119.

- ^ Fulbrook (1991), p. 108.

- ^ The Nazi War Against the Catholic Church. Washington D.C.: National Catholic Welfare Conference. 1942. p. 74-80.

- ^ Evans (2009), pp. 529–30.

- ^ Pope Pius XII (1943). Encyclical Mystici corporis Christi. Libreria Editrice Vaticana.