Signum manus

Signum manus (transl. sign of the hand, sometimes also known as Chrismon) refers to the medieval European practice of signing a document or charter with a special type of monogram or royal cypher. The practice is documented from at least the Merovingian period (ca. 5th century) until the 14th century in the Frankish Empire and its successors.

History

[edit]The term Chrismon was introduced in Neo-Latin specifically as a term for the Chi Rho monogram. As this symbol was used in Merovingian documents at the starting point of what would diversify into the tradition of "cross-signatures", German scholarship of the 18th century extended use of the term Chrismon to the entire field.[1] In medievalist paleography and Diplomatik (ars diplomaticae, i.e. the study of documents or charters), the study of these signatures or sigils was known as Chrismologia or Chrismenlehre, while the study of cross variants was known as Staurologia.[2]

Chrismon in this context may refer to the Merovingian period abbreviation I. C. N. for in Christi nomine, later (in the Carolingian period) also I. C. for in Christo, and still later (in the high medieval period) just C. for Christus.[3]

A cross symbol was often drawn as an invocation at the beginning of documents in the early medieval West. At the end of documents, commissioners or witnesses would sign with a signum manus, often also in the form of a simple cross. This practice is widespread in Merovingian documents of the 7th and 8th centuries.[4] A related development is the widespread use of the cross symbol on the obverse side of early medieval coins, interpreted as the signum manus of the moneyer.[5]

The tradition of minting coins with the monogram of the ruling monarch on the obverse side originates in the 5th century, both in Byzantium and in Rome. This tradition was continued in the 6th century by Germanic kings, including the Merovingians. These early designs were box monograms. The first cruciform monogram was used by Justinian I in the 560s. Tiberius III used a cruciform monogram with the letters R, M for Rome and T, B for Tiberius; Pope Gregory III used the letters G, R, E, O.[6]

The earliest surviving Merovingian royal charters, dating to the 7th century, have the box monograms of Chlothar II and Clovis II.[7] Later in the 7th century, the use of royal monograms was abandoned entirely by the Merovingian kings; instead, royal wax seals were first attached to the documents, and the kings would sign their name in full.

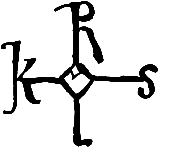

The signum manus in the form of a modified cross symbol first appears in charters of both Frankish Gaul and Anglo-Saxon England in the late 7th and early 8th century. Charlemagne first used his cruciform monogram, likely inspired by the earlier papal monograms, in 769, and he would continue to use it for the rest of his reign. The monogram spells KAROLVS, with the consonants K, R, L, S at the ends of the cross-arms, and the vowels A, O, V displayed in ligature at the center.[8] Louis the Pious abandoned the cross monogram, using again a H-type or box monogram.[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Chrismon in Meyers Konversations-Lexikon 4th ed. (1888/9).

- ^ from stauros "stake, cross"; the same term Staurologia in a different context may also refer to the field of Theology of the Cross.

- ^ Gatterer (1798), p. 64f.

- ^ Garipzanov (2008:161f)

- ^ Garipzanov (2008:163f)

- ^ Garipzanov (2008:173)

- ^ Garipzanov (2008:167)

- ^ Garipzanov (2008:172)

- ^ Garipzanov (2008:182)

- Ildar H. Garipzanov, Chapter 4 in The Symbolic Language of Royal Authority in the Carolingian World (c.751-877) (2008), 157–202.

- Ersch et al., Volume 1, Issue 29 of Allgemeine Encyklopädie der Wissenschaften und Künste, 1837, 303–307.

- Johann Christoph Gatterer, Elementa artis diplomaticae universalis (1765), 145–149 ( Abriß der Diplomatik 1798, 64–67).

- Karl Friedrich Stumpf-Brentano, Die Wirzburger Immunitaet-Urkunden des X und XI Jahrhunderts vol. 1 (1874), 13–17.