Otitis media

| Otitis media | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Otitis media with effusion: serous otitis media, secretory otitis media |

| |

| A bulging tympanic membrane which is typical in a case of acute otitis media | |

| Specialty | Otorhinolaryngology |

| Symptoms | Ear pain, fever, hearing loss[1][2] |

| Types | Acute otitis media, otitis media with effusion, chronic suppurative otitis media[3][4] |

| Causes | Viral, bacterial[4] |

| Risk factors | Smoke exposure, daycare[4] |

| Prevention | Vaccination, breastfeeding[1] |

| Medication | Paracetamol (acetaminophen), ibuprofen, benzocaine ear drops[1] |

| Frequency | 471 million (2015)[5] |

| Deaths | 3,200 (2015)[6] |

Otitis media is a group of inflammatory diseases of the middle ear.[2] One of the two main types is acute otitis media (AOM),[3] an infection of rapid onset that usually presents with ear pain.[1] In young children this may result in pulling at the ear, increased crying, and poor sleep.[1] Decreased eating and a fever may also be present.[1] The other main type is otitis media with effusion (OME), typically not associated with symptoms,[1] although occasionally a feeling of fullness is described;[4] it is defined as the presence of non-infectious fluid in the middle ear which may persist for weeks or months often after an episode of acute otitis media.[4] Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) is middle ear inflammation that results in a perforated tympanic membrane with discharge from the ear for more than six weeks.[7] It may be a complication of acute otitis media.[4] Pain is rarely present.[4] All three types of otitis media may be associated with hearing loss.[2][3] If children with hearing loss due to OME do not learn sign language, it may affect their ability to learn.[8]

The cause of AOM is related to childhood anatomy and immune function.[4] Either bacteria or viruses may be involved.[4] Risk factors include exposure to smoke, use of pacifiers, and attending daycare.[4] It occurs more commonly among indigenous Australians and those who have cleft lip and palate or Down syndrome.[4][9] OME frequently occurs following AOM and may be related to viral upper respiratory infections, irritants such as smoke, or allergies.[3][4] Looking at the eardrum is important for making the correct diagnosis.[10] Signs of AOM include bulging or a lack of movement of the tympanic membrane from a puff of air.[1][11] New discharge not related to otitis externa also indicates the diagnosis.[1]

A number of measures decrease the risk of otitis media including pneumococcal and influenza vaccination, breastfeeding, and avoiding tobacco smoke.[1] The use of pain medications for AOM is important.[1] This may include paracetamol (acetaminophen), ibuprofen, benzocaine ear drops, or opioids.[1] In AOM, antibiotics may speed recovery but may result in side effects.[12] Antibiotics are often recommended in those with severe disease or under two years old.[11] In those with less severe disease they may only be recommended in those who do not improve after two or three days.[11] The initial antibiotic of choice is typically amoxicillin.[1] In those with frequent infections tympanostomy tubes may decrease recurrence.[1] In children with otitis media with effusion antibiotics may increase resolution of symptoms, but may cause diarrhoea, vomiting and skin rash.[13]

Worldwide AOM affects about 11% of people a year (about 325 to 710 million cases).[14][15] Half the cases involve children less than five years of age and it is more common among males.[4][14] Of those affected about 4.8% or 31 million develop chronic suppurative otitis media.[14] The total number of people with CSOM is estimated at 65–330 million people.[16] Before the age of ten OME affects about 80% of children at some point.[4] Otitis media resulted in 3,200 deaths in 2015 – down from 4,900 deaths in 1990.[6][17]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

The primary symptom of acute otitis media is ear pain; other possible symptoms include fever, reduced hearing during periods of illness, tenderness on touch of the skin above the ear, purulent discharge from the ears, irritability, ear blocking sensation and diarrhea (in infants).[18] Since an episode of otitis media is usually precipitated by an upper respiratory tract infection (URTI), there are often accompanying symptoms like a cough and nasal discharge.[1] One might also experience a feeling of fullness in the ear.[19]

Discharge from the ear can be caused by acute otitis media with perforation of the eardrum, chronic suppurative otitis media, tympanostomy tube otorrhea, or acute otitis externa.[20] Trauma, such as a basilar skull fracture, can also lead to cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea (discharge of CSF from the ear) due to cerebral spinal drainage from the brain and its covering (meninges).[citation needed]

Causes

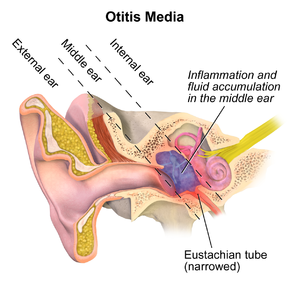

[edit]The common cause of all forms of otitis media is dysfunction of the Eustachian tube.[21] This is usually due to inflammation of the mucous membranes in the nasopharynx, which can be caused by a viral upper respiratory tract infection (URTI), strep throat, or possibly by allergies.[22]

By reflux or aspiration of unwanted secretions from the nasopharynx into the normally sterile middle-ear space, the fluid may then become infected – usually with bacteria. The virus that caused the initial upper respiratory infection can itself be identified as the pathogen causing the infection.[22]

Diagnosis

[edit]

As its typical symptoms overlap with other conditions, such as acute external otitis, symptoms alone are not sufficient to predict whether acute otitis media is present; it has to be complemented by visualization of the tympanic membrane.[23][24] Examiners may use a pneumatic otoscope with a rubber bulb attached to assess the mobility of the tympanic membrane. Other methods to diagnose otitis media is with a tympanometry, reflectometry, or hearing test.

In more severe cases, such as those with associated hearing loss or high fever, audiometry, tympanogram, temporal bone CT and MRI can be used to assess for associated complications, such as mastoid effusion, subperiosteal abscess formation, bony destruction, venous thrombosis or meningitis.[25]

Acute otitis media in children with moderate to severe bulging of the tympanic membrane or new onset of otorrhea (drainage) is not due to external otitis.[26] Also, the diagnosis may be made in children who have mild bulging of the ear drum and recent onset of ear pain (less than 48 hours) or intense erythema (redness) of the ear drum.[27][28][29] To confirm the diagnosis, middle-ear effusion and inflammation of the eardrum (called myringitis or tympanitis) have to be identified; signs of these are fullness, bulging, cloudiness and redness of the eardrum.[1] It is important to attempt to differentiate between acute otitis media and otitis media with effusion (OME), as antibiotics are not recommended for OME.[1] It has been suggested that bulging of the tympanic membrane is the best sign to differentiate AOM from OME, with a bulging of the membrane suggesting AOM rather than OME.[30]

Viral otitis may result in blisters on the external side of the tympanic membrane, which is called bullous myringitis (myringa being Latin for "eardrum").[31] However, sometimes even examination of the eardrum may not be able to confirm the diagnosis, especially if the canal is small.[32] If wax in the ear canal obscures a clear view of the eardrum it should be removed using a blunt cerumen curette or a wire loop. Also, an upset young child's crying can cause the eardrum to look inflamed due to distension of the small blood vessels on it, mimicking the redness associated with otitis media.

Acute otitis media

[edit]The most common bacteria isolated from the middle ear in AOM are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis,[1] and Staphylococcus aureus.[33]

Otitis media with effusion

[edit]Otitis media with effusion (OME), also known as serous otitis media (SOM) or secretory otitis media (SOM), and colloquially referred to as 'glue ear,'[34] is fluid accumulation that can occur in the middle ear and mastoid air cells due to negative pressure produced by dysfunction of the Eustachian tube. This can be associated with a viral upper respiratory infection (URI) or bacterial infection such as otitis media.[35] An effusion can cause conductive hearing loss if it interferes with the transmission of vibrations of middle ear bones to the vestibulocochlear nerve complex that are created by sound waves.[36]

Early-onset OME is associated with feeding of infants while lying down, early entry into group child care, parental smoking, lack or too short a period of breastfeeding, and greater amounts of time spent in group child care, particularly those with a large number of children. These risk factors increase the incidence and duration of OME during the first two years of life.[37]

Chronic suppurative otitis media

[edit]Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) is a long-term middle ear inflammation causing persistent ear discharge due to a perforated eardrum. It often follows an unresolved upper respiratory infection leading to acute otitis media. Prolonged inflammation leads to middle ear swelling, ulceration, perforation, and attempts at repair with granulation tissue and polyps. This can worsen discharge and inflammation, potentially developing into CSOM, often associated with cholesteatoma. Symptoms may include ear discharge or pus seen only on examination. Hearing loss is common. Risk factors include poor eustachian tube function, recurrent ear infections, crowded living, daycare attendance, and certain craniofacial malformations.[citation needed]

Worldwide approximately 11% of the human population is affected by AOM every year, or 709 million cases.[14][15] About 4.4% of the population develop CSOM.[15]

According to the World Health Organization, CSOM is a primary cause of hearing loss in children.[38] Adults with recurrent episodes of CSOM have a higher risk of developing permanent conductive and sensorineural hearing loss.

In Britain, 0.9% of children and 0.5% of adults have CSOM, with no difference between the sexes.[38] The incidence of CSOM across the world varies dramatically where high income countries have a relatively low prevalence while in low income countries the prevalence may be up to three times as great.[14] Each year 21,000 people worldwide die due to complications of CSOM.[38]

Adhesive otitis media

[edit]Adhesive otitis media occurs when a thin retracted ear drum becomes sucked into the middle-ear space and stuck (i.e., adherent) to the ossicles and other bones of the middle ear.

Prevention

[edit]AOM is far less common in breastfed infants than in formula-fed infants,[39] and the greatest protection is associated with exclusive breastfeeding (no formula use) for the first six months of life.[1] A longer duration of breastfeeding is correlated with a longer protective effect.[39]

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) in early infancy decrease the risk of acute otitis media in healthy infants.[40] PCV is recommended for all children, and, if implemented broadly, PCV would have a significant public health benefit.[1] Influenza vaccination in children appears to reduce rates of AOM by 4% and the use of antibiotics by 11% over 6 months.[41] However, the vaccine resulted in increased adverse-effects such as fever and runny nose.[41] The small reduction in AOM may not justify the side effects and inconvenience of influenza vaccination every year for this purpose alone.[41] PCV does not appear to decrease the risk of otitis media when given to high-risk infants or for older children who have previously experienced otitis media.[40]

Risk factors such as season, allergy predisposition and presence of older siblings are known to be determinants of recurrent otitis media and persistent middle-ear effusions (MEE).[42] History of recurrence, environmental exposure to tobacco smoke, use of daycare, and lack of breastfeeding have all been associated with increased risk of development, recurrence, and persistent MEE.[43][44] Pacifier use has been associated with more frequent episodes of AOM.[45]

Long-term antibiotics, while they decrease rates of infection during treatment, have an unknown effect on long-term outcomes such as hearing loss.[46] This method of prevention has been associated with emergence of undesirable antibiotic-resistant otitic bacteria.[1]

There is moderate evidence that the sugar substitute xylitol may reduce infection rates in healthy children who go to daycare.[47]

Evidence does not support zinc supplementation as an effort to reduce otitis rates except maybe in those with severe malnutrition such as marasmus.[48]

Probiotics do not show evidence of preventing acute otitis media in children.[49]

Management

[edit]Oral and topical pain killers are the mainstay for the treatment of pain caused by otitis media. Oral agents include ibuprofen, paracetamol (acetaminophen), and opiates. A 2023 review found evidence for the effectiveness of single or combinations of oral pain relief in acute otitis media is lacking.[50] Topical agents shown to be effective include antipyrine and benzocaine ear drops.[51] Decongestants and antihistamines, either nasal or oral, are not recommended due to the lack of benefit and concerns regarding side effects.[52] Half of cases of ear pain in children resolve without treatment in three days and 90% resolve in seven or eight days.[53] The use of steroids is not supported by the evidence for acute otitis media.[54][55]

Antibiotics

[edit]Use of antibiotics for acute otitis media has benefits and harms. As over 82% of acute episodes settle without treatment, about 20 children must be treated to prevent one case of ear pain, 33 children to prevent one perforation, and 11 children to prevent one opposite-side ear infection. For every 14 children treated with antibiotics, one child has an episode of vomiting, diarrhea or a rash.[56] Analgesics may relieve pain, if present. For people requiring surgery to treat otitis media with effusion, preventative antibiotics may not help reduce the risk of post-surgical complications.[57]

For bilateral acute otitis media in infants younger than 24 months, there is evidence that the benefits of antibiotics outweigh the harms.[12] A 2015 Cochrane review concluded that watchful waiting is the preferred approach for children over six months with non severe acute otitis media.[12]

| Summary[12] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Findings in words | Findings in numbers | Quality of evidence |

| Pain | |||

| Pain at 24 hours | Antibiotics causes little or no reduction to the chance of experiencing the outcome when compared with placebo for acute otitis media in children. Data are based on high quality evidence. | RR 0.89 (0.78 to 1.01) | High |

| Pain at 2 to 3 days | Antibiotics slightly reduces the chance of experiencing the outcome when compared with placebo for acute otitis media in children. Data are based on high quality evidence. | RR 0.70 (0.57 to 0.86) | High |

| Pain at 4 to 7 days | Antibiotics slightly reduces the chance of experiencing the outcome when compared with placebo for acute otitis media in children. Data are based on high quality evidence. | RR 0.76 (0.63 to 0.91) | High |

| Pain at 10 to 12 days | Antibiotics probably reduces the chance of experiencing the outcome when compared with placebo for acute otitis media in children. Data are based on moderate quality evidence. | RR 0.33 (0.17 to 0.66) | Moderate |

| Abnormal tympanometry | |||

| 2 to 4 weeks | Antibiotics slightly reduces the chance of experiencing the outcome when compared with placebo for acute otitis media in children. Data are based on high quality evidence. | RR 0.82 (0.74 to 0.90) | High |

| 3 months | Antibiotics causes little or no reduction to the chance of experiencing the outcome when compared with placebo for acute otitis media in children. Data are based on high quality evidence. | RR 0.97 (0.76 to 1.24) | High |

| Vomiting | |||

| Diarrhoea or rash | Antibiotics slightly increases the chance of experiencing the outcome when compared with placebo for acute otitis media in children. Data are based on high quality evidence. | RR 1.38 (1.19 to 1.59) | High |

Most children older than 6 months of age who have acute otitis media do not benefit from treatment with antibiotics. If antibiotics are used, a narrow-spectrum antibiotic like amoxicillin is generally recommended, as broad-spectrum antibiotics may be associated with more adverse events.[1][58] If there is resistance or use of amoxicillin in the last 30 days then amoxicillin-clavulanate or another penicillin derivative plus beta lactamase inhibitor is recommended.[1] Taking amoxicillin once a day may be as effective as twice[59] or three times a day. While less than 7 days of antibiotics have fewer side effects, more than seven days appear to be more effective.[60] If there is no improvement after 2–3 days of treatment a change in therapy may be considered.[1] Azithromycin appears to have less side effects than either high dose amoxicillin or amoxicillin/clavulanate.[61]

Tympanostomy tube

[edit]Tympanostomy tubes (also called "grommets") are recommended with three or more episodes of acute otitis media in 6 months or four or more in a year, with at least one episode or more attacks in the preceding 6 months.[1] There is tentative evidence that children with recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) who receive tubes have a modest improvement in the number of further AOM episodes (around one fewer episode at six months and less of an improvement at 12 months following the tubes being inserted).[62][63] Evidence does not support an effect on long-term hearing or language development.[63][64] A common complication of having a tympanostomy tube is otorrhea, which is a discharge from the ear.[65] The risk of persistent tympanic membrane perforation after children have grommets inserted may be low.[62] It is still uncertain whether or not grommets are more effective than a course of antibiotics.[62]

Oral antibiotics should not be used to treat uncomplicated acute tympanostomy tube otorrhea.[65] They are not sufficient for the bacteria that cause this condition and have side effects including increased risk of opportunistic infection.[65] In contrast, topical antibiotic eardrops are useful.[65]

Otitis media with effusion

[edit]The decision to treat is usually made after a combination of physical exam and laboratory diagnosis, with additional testing including audiometry, tympanogram, temporal bone CT and MRI.[66][67][68] Decongestants,[69] glucocorticoids,[70] and topical antibiotics are generally not effective as treatment for non-infectious, or serous, causes of mastoid effusion.[66] Moreover, it is recommended against using antihistamines and decongestants in children with OME.[69] In less severe cases or those without significant hearing impairment, the effusion can resolve spontaneously or with more conservative measures such as autoinflation.[71][72] In more severe cases, tympanostomy tubes can be inserted,[64] possibly with adjuvant adenoidectomy[66] as it shows a significant benefit as far as the resolution of middle ear effusion in children with OME is concerned.[73]

Chronic suppurative otitis media

[edit]Topical antibiotics are of uncertain benefit as of 2020.[74] Some evidence suggests that topical antibiotics may be useful either alone or with antibiotics by mouth.[74] Antiseptics are of unclear effect.[75] Topical antibiotics (quinolones) are probably better at resolving ear discharge than antiseptics.[76]

Alternative medicine

[edit]Complementary and alternative medicine is not recommended for otitis media with effusion because there is no evidence of benefit.[35] Homeopathic treatments have not been proven to be effective for acute otitis media in a study with children.[77] An osteopathic manipulation technique called the Galbreath technique[78] was evaluated in one randomized controlled clinical trial; one reviewer concluded that it was promising, but a 2010 evidence report found the evidence inconclusive.[79]

Outcomes

[edit]

| no data < 10 10–14 14–18 18–22 22–26 26–30 | 30–34 34–38 38–42 42–46 46–50 > 50 |

Complications of acute otitis media consists of perforation of the ear drum, infection of the mastoid space behind the ear (mastoiditis), and more rarely intracranial complications can occur, such as bacterial meningitis, brain abscess, or dural sinus thrombosis.[80] It is estimated that each year 21,000 people die due to complications of otitis media.[14]

Membrane rupture

[edit]In severe or untreated cases, the tympanic membrane may perforate, allowing the pus in the middle-ear space to drain into the ear canal. If there is enough, this drainage may be obvious. Even though the perforation of the tympanic membrane suggests a highly painful and traumatic process, it is almost always associated with a dramatic relief of pressure and pain. In a simple case of acute otitis media in an otherwise healthy person, the body's defenses are likely to resolve the infection and the ear drum nearly always heals. An option for severe acute otitis media in which analgesics are not controlling ear pain is to perform a tympanocentesis, i.e., needle aspiration through the tympanic membrane to relieve the ear pain and to identify the causative organism(s).

Hearing loss

[edit]Children with recurrent episodes of acute otitis media and those with otitis media with effusion or chronic suppurative otitis media have higher risks of developing conductive and sensorineural hearing loss. Globally approximately 141 million people have mild hearing loss due to otitis media (2.1% of the population).[81] This is more common in males (2.3%) than females (1.8%).[81]

This hearing loss is mainly due to fluid in the middle ear or rupture of the tympanic membrane. Prolonged duration of otitis media is associated with ossicular complications and, together with persistent tympanic membrane perforation, contributes to the severity of the disease and hearing loss. When a cholesteatoma or granulation tissue is present in the middle ear, the degree of hearing loss and ossicular destruction is even greater.[82]

Periods of conductive hearing loss from otitis media may have a detrimental effect on speech development in children.[83][84][85] Some studies have linked otitis media to learning problems, attention disorders, and problems with social adaptation.[86] Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that individuals with otitis media have more depression/anxiety-related disorders compared to individuals with normal hearing.[87] Once the infections resolve and hearing thresholds return to normal, childhood otitis media may still cause minor and irreversible damage to the middle ear and cochlea.[88] More research on the importance of screening all children under 4 years old for otitis media with effusion needs to be performed.[84]

Epidemiology

[edit]Acute otitis media is very common in childhood. It is the most common condition for which medical care is provided in children under five years of age in the US.[22] Acute otitis media affects 11% of people each year (709 million cases) with half occurring in those below five years.[14] Chronic suppurative otitis media affects about 5% or 31 million of these cases with 22.6% of cases occurring annually under the age of five years.[14] Otitis media resulted in 2,400 deaths in 2013 – down from 4,900 deaths in 1990.[17]

Australian Aboriginals experience a high level of conductive hearing loss largely due to the massive incidence of middle ear disease among the young in Aboriginal communities. Aboriginal children experience middle ear disease for two and a half years on average during childhood compared with three months for non indigenous children. If untreated it can leave a permanent legacy of hearing loss.[89] The higher incidence of deafness in turn contributes to poor social, educational and emotional outcomes for the children concerned. Such children as they grow into adults are also more likely to experience employment difficulties and find themselves caught up in the criminal justice system. Research in 2012 revealed that nine out of ten Aboriginal prison inmates in the Northern Territory suffer from significant hearing loss.[90] Andrew Butcher speculates that the lack of fricatives and the unusual segmental inventories of Australian languages may be due to the very high presence of otitis media ear infections and resulting hearing loss in their populations. People with hearing loss often have trouble distinguishing different vowels and hearing fricatives and voicing contrasts. Australian Aboriginal languages thus seem to show similarities to the speech of people with hearing loss, and avoid those sounds and distinctions which are difficult for people with early childhood hearing loss to perceive. At the same time, Australian languages make full use of those distinctions, namely place of articulation distinctions, which people with otitis media-caused hearing loss can perceive more easily.[91] This hypothesis has been challenged on historical, comparative, statistical, and medical grounds.[92]

Etymology

[edit]The term otitis media is composed of otitis, Ancient Greek for "inflammation of the ear", and media, Latin for "middle".

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, Ganiats TG, Hoberman A, Jackson MA, et al. (March 2013). "The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media". Pediatrics. 131 (3): e964–999. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3488. PMID 23439909.

- ^ a b c Qureishi A, Lee Y, Belfield K, Birchall JP, Daniel M (January 2014). "Update on otitis media – prevention and treatment". Infection and Drug Resistance. 7: 15–24. doi:10.2147/IDR.S39637. PMC 3894142. PMID 24453496.

- ^ a b c d "Ear Infections". cdc.gov. September 30, 2013. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Minovi A, Dazert S (2014). "Diseases of the middle ear in childhood". GMS Current Topics in Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. 13: Doc11. doi:10.3205/cto000114. PMC 4273172. PMID 25587371.

- ^ Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ a b Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ Emmett SD, Kokesh J, Kaylie D (November 2018). "Chronic Ear Disease". The Medical Clinics of North America. 102 (6): 1063–1079. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2018.06.008. PMID 30342609. S2CID 53045631.

- ^ Ruben RJ, Schwartz R (February 1999). "Necessity versus sufficiency: the role of input in language acquisition". International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 47 (2): 137–140. doi:10.1016/S0165-5876(98)00132-3. PMID 10206361. Archived from the original on 2018-06-14. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ^ "Ear disease in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children" (PDF). AIHW. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- ^ Coker TR, Chan LS, Newberry SJ, Limbos MA, Suttorp MJ, Shekelle PG, et al. (November 2010). "Diagnosis, microbial epidemiology, and antibiotic treatment of acute otitis media in children: a systematic review". JAMA. 304 (19): 2161–2169. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1651. PMID 21081729.

- ^ a b c "Otitis Media: Physician Information Sheet (Pediatrics)". cdc.gov. November 4, 2013. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d Venekamp RP, Sanders SL, Glasziou PP, Rovers MM (2023-11-15). "Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11 (11): CD000219. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000219.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 10646935. PMID 37965923.

- ^ Venekamp RP, Burton MJ, van Dongen TM, van der Heijden GJ, van Zon A, Schilder AG (June 2016). "Antibiotics for otitis media with effusion in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (6): CD009163. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009163.pub3. PMC 7117560. PMID 27290722.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Monasta L, Ronfani L, Marchetti F, Montico M, Vecchi Brumatti L, Bavcar A, et al. (2012). "Burden of disease caused by otitis media: systematic review and global estimates". PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e36226. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...736226M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036226. PMC 3340347. PMID 22558393.

- ^ a b c Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, Bertozzi-Villa A, Biryukov S, Bolliger I, et al. (Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators) (August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMC 4561509. PMID 26063472.

- ^ Erasmus T (2012-09-17). "Chronic suppurative otitis media". Continuing Medical Education. 30 (9): 335–336–336. ISSN 2078-5143. Archived from the original on 2020-10-20. Retrieved 2019-08-07.

- ^ a b GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–171. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

{{cite journal}}:|author1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ CPNP Kristine M. Ruggiero, PhD, MSN, RN, PA-C Michael Ruggiero, MHS (2020-09-14). Fast Facts Handbook for Pediatric Primary Care: A Guide for Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants. Springer Publishing Company. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8261-5184-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hart KM (2023-07-04). Ear Health 101: The Complete Guide to Understanding Ear Infections. Xspurts.com. ISBN 978-1-77684-782-2.

- ^ Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, III JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE (2011-06-10). Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics E-Book: Expert Consult Premium Edition - Enhanced Online Features and Print. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1-4377-3589-5.

- ^ Bluestone CD (2005). Eustachian tube: structure, function, role in otitis media. Hamilton, London: BC Decker. pp. 1–219. ISBN 978-1-55009-066-6.

- ^ a b c Donaldson JD. "Acute Otitis Media". Medscape. Archived from the original on 28 March 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Laine MK, Tähtinen PA, Ruuskanen O, Huovinen P, Ruohola A (May 2010). "Symptoms or symptom-based scores cannot predict acute otitis media at otitis-prone age". Pediatrics. 125 (5): e1154–61. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2689. PMID 20368317. S2CID 709374.

- ^ Shaikh N, Hoberman A, Kaleida PH, Ploof DL, Paradise JL (May 2010). "Videos in clinical medicine. Diagnosing otitis media – otoscopy and cerumen removal". The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (20): e62. doi:10.1056/NEJMvcm0904397. PMID 20484393.

- ^ Patel MM, Eisenberg L, Witsell D, Schulz KA (October 2008). "Assessment of acute otitis externa and otitis media with effusion performance measures in otolaryngology practices". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 139 (4): 490–494. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2008.07.030. PMID 18922333. S2CID 24036039.

- ^ Jamal A, Alsabea A, Tarakmeh M, Safar A (2022). "Etiology, Diagnosis, Complications, and Management of Acute Otitis Media in Children". Cureus. 14 (8): e28019. doi:10.7759/cureus.28019. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 9471510. PMID 36134092.

- ^ Schilder AG, Chonmaitree T, Cripps AW, Rosenfeld RM, Casselbrant ML, Haggard MP, et al. (2016). "Otitis media". Nature Reviews. Disease Primers. 2 (1): 16063. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.63. ISSN 2056-676X. PMC 7097351. PMID 27604644.

- ^ "PGS.TS.TTƯT Lê Lương Đống". Viêm tai giữa - Tất cả những điều cần biết. Retrieved 2024-07-15.

- ^ BPharm YS (2010-04-27). "Otitis Media Diagnosis". News-Medical. Retrieved 2024-07-15.

- ^ Shaikh N, Hoberman A, Rockette HE, Kurs-Lasky M (March 28, 2012). "Development of an algorithm for the diagnosis of otitis media" (PDF). Academic Pediatrics (Submitted manuscript). 12 (3): 214–218. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2012.01.007. PMID 22459064. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ Roberts DB (April 1980). "The etiology of bullous myringitis and the role of mycoplasmas in ear disease: a review". Pediatrics. 65 (4): 761–766. doi:10.1542/peds.65.4.761. PMID 7367083. S2CID 31536385.

- ^ Kline MW, Blaney SM, Giardino AP, Orange JS, Penny DJ, Schutze GE, et al. (2018-08-21). Rudolph's Pediatrics, 23rd Edition. McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 978-1-259-58860-0.

- ^ Benninger MS (March 2008). "Acute bacterial rhinosinusitis and otitis media: changes in pathogenicity following widespread use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 138 (3): 274–278. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2007.11.011. PMID 18312870. S2CID 207300175.

- ^ "Glue Ear". NHS Choices. Department of Health. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ a b Rosenfeld RM, Culpepper L, Yawn B, Mahoney MC (June 2004). "Otitis media with effusion clinical practice guideline". American Family Physician. 69 (12): 2776, 2778–2779. PMID 15222643.

- ^ "Otitis media with effusion: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ Owen MJ, Baldwin CD, Swank PR, Pannu AK, Johnson DL, Howie VM (November 1993). "Relation of infant feeding practices, cigarette smoke exposure, and group child care to the onset and duration of otitis media with effusion in the first two years of life". The Journal of Pediatrics. 123 (5): 702–711. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(05)80843-1. PMID 8229477.

- ^ a b c Acuin J, WHO Dept. of Child and Adolescent Health and Development, WHO Programme for the Prevention of Blindness and Deafness (2004). Chronic suppurative otitis media : burden of illness and management options. Geneve: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/42941. ISBN 978-92-4-159158-4.

- ^ a b Lawrence R (2016). Breastfeeding : a guide for the medical profession, 8th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. pp. 216–217. ISBN 978-0-323-35776-0.

- ^ a b Fortanier AC, Venekamp RP, Boonacker CW, Hak E, Schilder AG, Sanders EA, et al. (28 May 2019). "Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines for preventing acute otitis media in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5): CD001480. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001480.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6537667. PMID 31135969.

- ^ a b c Norhayati MN, Ho JJ, Azman MY (October 2017). "Influenza vaccines for preventing acute otitis media in infants and children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (10): CD010089. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010089.pub3. PMC 6485791. PMID 29039160.

- ^ Rovers MM, Schilder AG, Zielhuis GA, Rosenfeld RM (February 2004). "Otitis media". Lancet. 363 (9407): 465–473. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15495-0. PMID 14962529. S2CID 30439271.

- ^ Pukander J, Luotonen J, Timonen M, Karma P (1985). "Risk factors affecting the occurrence of acute otitis media among 2–3-year-old urban children". Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 100 (3–4): 260–265. doi:10.3109/00016488509104788. PMID 4061076.

- ^ Etzel RA (February 1987). "Smoke and ear effusions". Pediatrics. 79 (2): 309–311. doi:10.1542/peds.79.2.309a. PMID 3808812. S2CID 1350590.

- ^ Rovers MM, Numans ME, Langenbach E, Grobbee DE, Verheij TJ, Schilder AG (August 2008). "Is pacifier use a risk factor for acute otitis media? A dynamic cohort study". Family Practice. 25 (4): 233–236. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmn030. PMID 18562333.

- ^ Leach AJ, Morris PS (October 2006). Leach AJ (ed.). "Antibiotics for the prevention of acute and chronic suppurative otitis media in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (4): CD004401. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004401.pub2. PMC 11324013. PMID 17054203.

- ^ Azarpazhooh A, Lawrence HP, Shah PS (August 2016). "Xylitol for preventing acute otitis media in children up to 12 years of age". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (8): CD007095. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007095.pub3. PMC 8485974. PMID 27486835.

- ^ Gulani A, Sachdev HS (June 2014). "Zinc supplements for preventing otitis media". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (6): CD006639. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006639.pub4. PMC 9392835. PMID 24974096.

- ^ Scott AM, Clark J, Julien B, Islam F, Roos K, Grimwood K, et al. (18 June 2019). "Probiotics for preventing acute otitis media in children". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (6): CD012941. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012941.pub2. PMC 6580359. PMID 31210358.

- ^ de Sévaux J, Damoiseaux RA, van de Pol AC, Lutje V, Hay AD, Little P, et al. (18 August 2023). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, alone or combined, for pain relief in acute otitis media in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (8): CD011534. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011534.pub3. PMC 10436353. PMID 37594020.

- ^ Sattout A (February 2008). "Best evidence topic reports. Bet 1. The role of topical analgesia in acute otitis media". Emergency Medicine Journal. 25 (2): 103–4. doi:10.1136/emj.2007.056648. PMID 18212148. S2CID 34753900.

- ^ Coleman C, Moore M (July 2008). Coleman C (ed.). "Decongestants and antihistamines for acute otitis media in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD001727. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001727.pub4. PMID 18646076. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001727.pub5, PMID 21412874, Retraction Watch)

- ^ Thompson M, Vodicka TA, Blair PS, Buckley DI, Heneghan C, Hay AD (December 2013). "Duration of symptoms of respiratory tract infections in children: systematic review". BMJ. 347 (dec11 1): f7027. doi:10.1136/bmj.f7027. PMC 3898587. PMID 24335668.

- ^ Principi N, Bianchini S, Baggi E, Esposito S (February 2013). "No evidence for the effectiveness of systemic corticosteroids in acute pharyngitis, community-acquired pneumonia and acute otitis media". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 32 (2): 151–60. doi:10.1007/s10096-012-1747-y. PMC 7087613. PMID 22993127.

- ^ Ranakusuma RW, Pitoyo Y, Safitri ED, Thorning S, Beller EM, Sastroasmoro S, et al. (March 2018). "Systemic corticosteroids for acute otitis media in children" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (3): CD012289. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012289.pub2. PMC 6492450. PMID 29543327. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-30. Retrieved 2019-12-16.

- ^ Venekamp RP, Sanders SL, Glasziou PP, Rovers MM (2023-11-15). "Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11 (11): CD000219. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000219.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 10646935. PMID 37965923.

- ^ Verschuur HP, de Wever WW, van Benthem PP (2004). "Antibiotic prophylaxis in clean and clean-contaminated ear surgery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (3): CD003996. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003996.pub2. PMC 9037065. PMID 15266512.

- ^ Coon ER, Quinonez RA, Morgan DJ, Dhruva SS, Ho T, Money N, et al. (April 2019). "2018 Update on Pediatric Medical Overuse: A Review". JAMA Pediatrics. 173 (4): 379–384. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5550. PMID 30776069. S2CID 73495617.

- ^ Thanaviratananich S, Laopaiboon M, Vatanasapt P (December 2013). "Once or twice daily versus three times daily amoxicillin with or without clavulanate for the treatment of acute otitis media". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD004975. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004975.pub3. PMC 10960641. PMID 24338106.

- ^ Kozyrskyj A, Klassen TP, Moffatt M, Harvey K (September 2010). "Short-course antibiotics for acute otitis media". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (9): CD001095. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001095.pub2. PMC 7052812. PMID 20824827.

- ^ Hum SW, Shaikh KJ, Musa SS, Shaikh N (December 2019). "Adverse Events of Antibiotics Used to Treat Acute Otitis Media in Children: A Systematic Meta-Analysis". The Journal of Pediatrics. 215: 139–143.e7. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.08.043. PMID 31561959. S2CID 203580952.

- ^ a b c Venekamp RP, Mick P, Schilder AG, Nunez DA (May 2018). "Grommets (ventilation tubes) for recurrent acute otitis media in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (6): CD012017. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012017.pub2. PMC 6494623. PMID 29741289.

- ^ a b Steele DW, Adam GP, Di M, Halladay CH, Balk EM, Trikalinos TA (June 2017). "Effectiveness of Tympanostomy Tubes for Otitis Media: A Meta-analysis". Pediatrics. 139 (6): e20170125. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-0125. PMID 28562283.

- ^ a b Browning GG, Rovers MM, Williamson I, Lous J, Burton MJ (October 2010). "Grommets (ventilation tubes) for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD001801. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001801.pub3. PMID 20927726. S2CID 43568574.

- ^ a b c d American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF), Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, archived (PDF) from the original on May 13, 2015, retrieved August 1, 2013, which cites

- Rosenfeld RM, Schwartz SR, Pynnonen MA, Tunkel DE, Hussey HM, Fichera JS, et al. (July 2013). "Clinical practice guideline: Tympanostomy tubes in children". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 149 (1 Suppl): S1–35. doi:10.1177/0194599813487302. PMID 23818543.

- ^ a b c Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, Coggins R, Gagnon L, Hackell JM, et al. (February 2016). "Clinical Practice Guideline: Otitis Media with Effusion (Update)". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 154 (1 Suppl): S1–S41. doi:10.1177/0194599815623467. PMID 26832942. S2CID 33459167. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

- ^ Wallace IF, Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Harrison MF, Kimple AJ, Steiner MJ (February 2014). "Surgical treatments for otitis media with effusion: a systematic review". Pediatrics. 133 (2): 296–311. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3228. PMID 24394689. S2CID 2355197.

- ^ Rosenfeld RM, Schwartz SR, Pynnonen MA, Tunkel DE, Hussey HM, Fichera JS, et al. (July 2013). "Clinical practice guideline: Tympanostomy tubes in children". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 149 (1 Suppl): S1-35. doi:10.1177/0194599813487302. PMID 23818543.

- ^ a b Griffin G, Flynn CA (September 2011). "Antihistamines and/or decongestants for otitis media with effusion (OME) in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (9): CD003423. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003423.pub3. PMC 7170417. PMID 21901683.

- ^ Simpson SA, Lewis R, van der Voort J, Butler CC (May 2011). "Oral or topical nasal steroids for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (5): CD001935. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001935.pub3. PMC 9829244. PMID 21563132.

- ^ Blanshard JD, Maw AR, Bawden R (June 1993). "Conservative treatment of otitis media with effusion by autoinflation of the middle ear". Clinical Otolaryngology and Allied Sciences. 18 (3): 188–92. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2273.1993.tb00827.x. PMID 8365006.

- ^ Perera R, Glasziou PP, Heneghan CJ, McLellan J, Williamson I (May 2013). "Autoinflation for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD006285. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006285.pub2. PMID 23728660.

- ^ van den Aardweg MT, Schilder AG, Herkert E, Boonacker CW, Rovers MM (January 2010). "Adenoidectomy for otitis media in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD007810. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007810.pub2. PMID 20091650.

- ^ a b Brennan-Jones CG, Head K, Chong LY, Burton MJ, Schilder AG, Bhutta MF, et al. (Cochrane ENT Group) (January 2020). "Topical antibiotics for chronic suppurative otitis media". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD013051. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013051.pub2. PMC 6956124. PMID 31896168.

- ^ Head K, Chong LY, Bhutta MF, Morris PS, Vijayasekaran S, Burton MJ, et al. (January 2020). Cochrane ENT Group (ed.). "Topical antiseptics for chronic suppurative otitis media". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD013055. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013055.pub2. PMC 6956662. PMID 31902140.

- ^ Head K, Chong LY, Bhutta MF, Morris PS, Vijayasekaran S, Burton MJ, et al. (Cochrane ENT Group) (January 2020). "Antibiotics versus topical antiseptics for chronic suppurative otitis media". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (11): CD013056. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013056.pub2. PMC 6956626. PMID 31902139.

- ^ Jacobs J, Springer DA, Crothers D (February 2001). "Homeopathic treatment of acute otitis media in children: a preliminary randomized placebo-controlled trial". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 20 (2): 177–183. doi:10.1097/00006454-200102000-00012. PMID 11224838.

- ^ Pratt-Harrington D (October 2000). "Galbreath technique: a manipulative treatment for otitis media revisited". The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 100 (10): 635–9. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2000.100.10.635 (inactive 2024-03-21). PMID 11105452. S2CID 245177279. Archived from the original on 2023-05-24. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of March 2024 (link) - ^ Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans R, Leininger B, Triano J (February 2010). "Effectiveness of manual therapies: the UK evidence report". Chiropractic & Osteopathy. 18 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/1746-1340-18-3. PMC 2841070. PMID 20184717.

- ^ Jung TT, Alper CM, Hellstrom SO, Hunter LL, Casselbrant ML, Groth A, et al. (April 2013). "Panel 8: Complications and sequelae". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 148 (4 Suppl): E122–143. doi:10.1177/0194599812467425. PMID 23536529. S2CID 206466859.

- ^ a b Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. (December 2012). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMC 6350784. PMID 23245607.

- ^ da Costa SS, Rosito LP, Dornelles C (February 2009). "Sensorineural hearing loss in patients with chronic otitis media". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 266 (2): 221–4. doi:10.1007/s00405-008-0739-0. hdl:10183/125807. PMID 18629531. S2CID 2932807.

- ^ Roberts K (June 1997). "A preliminary account of the effect of otitis media on 15-month-olds' categorization and some implications for early language learning". Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 40 (3): 508–18. doi:10.1044/jslhr.4003.508. PMID 9210110.

- ^ a b Simpson SA, Thomas CL, van der Linden MK, Macmillan H, van der Wouden JC, Butler C (January 2007). "Identification of children in the first four years of life for early treatment for otitis media with effusion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (1): CD004163. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004163.pub2. PMC 8765114. PMID 17253499.

- ^ Macfadyen CA, Acuin JM, Gamble C (2005-10-19). "Topical antibiotics without steroids for chronically discharging ears with underlying eardrum perforations". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005 (4): CD004618. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004618.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6669264. PMID 16235370.

- ^ Bidadi S, Nejadkazem M, Naderpour M (November 2008). "The relationship between chronic otitis media-induced hearing loss and the acquisition of social skills". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 139 (5): 665–70. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2008.08.004. PMID 18984261. S2CID 37667672.

- ^ Gouma P, Mallis A, Daniilidis V, Gouveris H, Armenakis N, Naxakis S (January 2011). "Behavioral trends in young children with conductive hearing loss: a case-control study". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 268 (1): 63–6. doi:10.1007/s00405-010-1346-4. PMID 20665042. S2CID 24611204.

- ^ Yilmaz S, Karasalihoglu AR, Tas A, Yagiz R, Tas M (February 2006). "Otoacoustic emissions in young adults with a history of otitis media". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 120 (2): 103–7. doi:10.1017/S0022215105004871. PMID 16359151. S2CID 23668097.

- ^ "Damien Howard & Dianne Hampton, "Ear disease and Aboriginal families," Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal, July-August 2006, 30 (4) p.9". Archived from the original on 2023-10-16. Retrieved 2023-09-06.

- ^ "Farah Farouque, "Hearing loss hits NT indigenous inmates," The Age, 5 March 2012". 4 March 2012. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ Butcher 2018.

- ^ Fergus A (2019). Lend Me Your Ears: Otitis Media and Aboriginal Australian languages (PDF) (BA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-10-10. Retrieved 2023-09-06.

- Butcher AR (2018). "The special nature of Australian phonologies: Why auditory constraints on human language sound systems are not universal". Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics. 176th Meeting of Acoustical Society of America. 177th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America. Vol. 35. Acoustical Society of America. p. 060004. doi:10.1121/2.0001004.

External links

[edit]- Neff MJ (June 2004). "AAP, AAFP, AAO-HNS release guideline on diagnosis and management of otitis media with effusion". American Family Physician. 69 (12): 2929–2931. PMID 15222658.