Redding, Connecticut

Redding, Connecticut | |

|---|---|

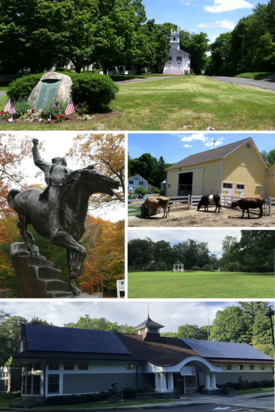

Clockwise from top: Town Center; New Pond Farm; Redding Green; Mark Twain Library; Equestrian statue of Israel Putnam at Putnam Memorial State Park | |

| Coordinates: 41°18′16″N 73°23′34″W / 41.30444°N 73.39278°W | |

| Country | |

| U.S. state | |

| County | Fairfield |

| Region | Western CT |

| Incorporated | 1767 |

| Villages/Sections | Redding Center Diamond Hill Five Points Georgetown (part) Redding Ridge Sanfordtown Topstone West Redding |

| Government | |

| • Type | Selectman-town meeting |

| • First selectman | Julia Pemberton (D) |

| • Selectman | Michael Thompson (R) |

| • Selectman | Peg O'Donnell (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 32.1 sq mi (83.1 km2) |

| • Land | 31.5 sq mi (81.6 km2) |

| • Water | 0.6 sq mi (1.4 km2) |

| Elevation | 472 ft (144 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 8,765 |

| • Density | 278.3/sq mi (107.5/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Code | 06896 |

| Area code(s) | 203/475 |

| FIPS code | 09-63480 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0213495 |

| Website | www |

Redding is a town in Fairfield County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 8,765 at the 2020 census.[1] The town is part of the Western Connecticut Planning Region.

History[edit]

Early settlement and establishment[edit]

At the time colonials began receiving grants for land within the boundaries of present-day Redding, Native American trails crossed through portions of the area, including the Berkshire Path running north–south.[2]

In 1639, Roger Ludlow (also referenced as Roger Ludlowe in many accounts) purchased land from local Native Americans to establish Fairfield,[3] and in 1668 Fairfield purchased another tract of land then called Northfield, which comprised land that is now part of Redding.[4]

For settlement purposes, Fairfield authorities divided the newly available land into parcels dubbed "long lots" at the time, which north–south measured no more than a third of a mile wide but extended east–west as long as 15 miles.[5] Immediately north of the long lots was a similar-sized parcel of land known as The Oblong.[6]

There are varying accounts as to the first colonial landholder in the Redding area; multiple citations suggest a Fairfield man named Richard Osborn obtained land there in 1671, while differing on how many acres he secured.[4] Nathan Gold, a Fairfield man who would serve as deputy governor of Connecticut from 1708 to 1723, received a land grant for 800 acres in 1681.[7]

The first colonials to settle in the area of present-day Redding lived near a Native American village led by Chickens Warrups (also referenced as Chicken Warrups or Sam Mohawk in some accounts), whose name is included on multiple land deeds secured by settlers throughout the area.[7]

According to Fairfield County and state records from the time Redding was formed, the original name of the town was Reading, after the town in Berkshire, England. Probably more accurately, however, town history attributes the name to John Read,[8] an early major landholder who was a prominent lawyer in Boston as well as a former Congregationalist preacher who converted to Anglicanism. Read helped in demarcating the boundaries of the town and in getting it recognized as a parish of Fairfield[9] in 1729. In 1767, soon after incorporation, the name was changed to its current spelling of Redding to better reflect its pronunciation.

In 1809, Congress granted Redding its first U.S. Post Office,[10] which made official in 1844 the spelling of the town's name.[11]

Revolutionary War and Continental Army encampment[edit]

In the years preceding the Declaration of Independence, tensions escalated in Redding between Tory loyalists and larger numbers of those supporting the resolutions of the Continental Congress, with some Tories fleeing to escape retribution.[5] Some 100 Redding men volunteered to serve under Captain Zalmon Read in a company of the new 5th Connecticut Regiment, which participated in the siege of Quebec's Fort Saint-Jean during the autumn of 1775 before the volunteers' terms of service expired in late November.[5]

In 1777, the Continental Congress created a new Continental Army with enlistments lasting three years. The 5th Connecticut Regiment was reformed, enlisting some men from Redding, and assigned to guard military stores in Danbury, Connecticut.[5] Getting word of the depot, the British dispatched a force of some 2,000 soldiers to destroy the stores, landing April 26 at present-day Westport and undertaking a 23-mile march north. The column halted on Redding Ridge for a two-hour respite, with many residents having fled to a wooded, rocky area dubbed the Devil's Den. The British column resumed its march to Danbury where soldiers destroyed the supplies, then skirmished Continental Army and militia forces in Ridgefield while on the return march south.[12]

For the winter of 1778–1779, General George Washington decided to split the Continental Army into three divisions encircling New York City, where British General Sir Henry Clinton had taken up winter quarters.[13] Major General Israel Putnam chose Redding as the winter encampment quarters for some 3,000 regulars and militia under his command, at the site of the present-day Putnam Memorial State Park and nearby areas. The Redding encampment allowed Putnam's soldiers to guard the replenished supply depot in Danbury and support any operations along Long Island Sound and the Hudson River Valley.[14] Some of the men were veterans of the winter encampment at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania the previous winter. Soldiers at the Redding camp endured supply shortages, cold temperatures and significant snow, with some historians dubbing the encampment "Connecticut's Valley Forge."[15]

Establishment of rail service[edit]

Construction began in 1850 on the Danbury and Norwalk Railroad, which linked those two cities following a 23-mile route along the Norwalk River valley that passed through Redding. Regular steam-engine service commenced March 1, 1852;[16] Leading to the establishment of the Redding station in West Redding, the Sanford station in Topstone, and the Georgetown station, which was originally built in Wilton, But later rebuilt in Redding.

Mining[edit]

In 1876, after A.N. Fillow began extracting mica in the Branchville section of Redding, two Yale University mineralogists noted the presence of previously undiscovered minerals lodged in pegmatite there and furnished funds to expand the operation. Historians say the mine produced between seven[17] and nine minerals until then unknown, including one that was named reddingite. Over time, the mine would produce quantities of quartz, feldspar, mica, beryl, spodumene and columbite.[18]

Another unique geological feature is the bedrock close to the train station. It is composed of nearly pure and massive garnet.[19]

Gilbert & Bennett factory[edit]

In 1834, Gilbert & Bennett Co. purchased the site of a former comb mill alongside the Norwalk River in the Georgetown section of Redding, and began producing wire mesh cloth for varying uses, in time to include sieves and window screens. In 1863, Gilbert & Bennett built a facility at the site for drawing metal wire. During World War I, the U.S. military adapted the company's products for camouflage netting, gas masks and trench liners; and during World War II, for signal corps uses.

A private equity group purchased the company in 1985, and began relocating operations elsewhere. In 1987, the Gilbert & Bennett site was included as part of the Georgetown Historic District listing on the National Register of Historic Places.[20]

In a 1987 nomination document for the National Register of Historic Places, proponents cited Gilbert & Bennett as an "anachronism" in the history of U.S. industry and labor.

"Peaceful, tree-lined residential streets converge on a functioning industrial complex; well-preserved historic houses stand cheek-by-jowl with modern factories; the deteriorated slum neighborhoods associated with modern industry do not exist," the nomination states. "The elite of Georgetown, almost exclusively people associated with Gilbert and Bennett, lived in the midst of their workers. The predictable ethnic neighborhoods did exist in Georgetown, outside the district for the most part, but their employees were apparently encouraged to occupy, or build houses next to the mansions of the managers and officers."[21]

In 1999, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency designated the factory pond and surrounding land a federal Superfund site to spur the remediation of pollution there.[22] Multiple developers have since attempted to finance the construction of a village development at the Gilbert & Bennett site, to include a mix of residential and commercial buildings.[23]

On the National Register of Historic Places[edit]

- Aaron Barlow House

- Daniel and Esther Bartlett House

- Georgetown Historic District

- Putnam Memorial State Park

- Redding Center Historic District

- Umpawaug District School

On the Connecticut Historic Resource Inventory[edit]

The Connecticut Historic Resource Inventory lists 230 structures in Redding, the oldest built in 1710 by early settler Moses Knapp.[24] The Town of Redding lists another 285 structures that are believed to have been built before 1901 that are not listed in the Connecticut Historic Resource Inventory, the oldest built in 1711 by John Read.[25]

Disasters[edit]

Redding has experienced several disasters, including the 2020 pandemic of the COVID-19 strain of coronavirus, with Connecticut declaring on March 10, 2020, a public health emergency and federal agencies subsequently approving Connecticut for disaster assistance. Through June 30, the state of Connecticut listed 69 Redding residents as having contracted COVID-19 or probably so,[26] with eight town residents having died of complications from coronavirus.[27] Statewide, schools closed and businesses furloughed workers after the closure of work sites deemed "non-essential" with the state allowing a phased resumption of business activities starting May 20. More than 700 Redding residents filed initial claims for unemployment compensation between March 15 and June 29, with unemployment peaking in mid-April when 434 residents were receiving benefits.[28]

Most other disasters were the result of severe weather events including Hurricane Sandy with tropical storm-force winds when it reached Connecticut October 29, 2012, toppling trees throughout the town and cutting power to 98 percent of homes and businesses.[29]

Sandy was the third storm to cause extensive electrical outages and property damage in Redding and Connecticut within the space of just over 14 months, along with Hurricane Irene in August 2011 and the so-called "Halloween nor'easter" in late October that year. The nor'easter dropped extensive snow onto trees that still had foliage, resulting in an increased number of snapped branches and trunks that damaged property and power lines, with some areas not seeing electricity restored for 11 days.[30]

In 1995, police arrested[31] and a jury subsequently convicted[32] Geoffrey K. Ferguson on charges he shot and killed tenants Scott D. Auerbach and David J. Froehlich, as well as three other men named David A. Gartrell, Sean E. Hiltunen, and Jason M. Trusewicz, at a house in Georgetown.

Beginning October 15, 1955, heavy rains caused flooding along the Norwalk River and other Connecticut waterways.[33] The flood of 1955 resulted in a dam failing at the Gilbert and Bennett factory and the inundation of the Georgetown neighborhood, amid other damage to property and infrastructure.[34]

A 1938 hurricane known as "the Long Island Express" destroyed crops in Redding,[35] but western Connecticut was spared the brunt of the storm that was the most destructive in New England recorded history.[36]

The Great Blizzard of 1888 (also known as the Great White Hurricane of 1888) buried Redding under significant snow in March that year, with one resident recollecting horses and cows "stood to their middles" in snow.[37]

Geography[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, Redding has a total area of 32.1 square miles (83 km2), of which 31.5 square miles (82 km2) is land and 0.6 square miles (1.6 km2), or 1.75%, is water.[38] Redding borders Bethel, Danbury, Easton, Newtown, Ridgefield, Wilton and Weston.

Redding has nine primary sections: Redding Center, Redding Ridge, Poverty Hollow, Sunset Hill, Lonetown, West Redding, Branchville, West Redding River Delta, and Georgetown, the last of which is situated at the junction of Redding, Ridgefield, Weston and Wilton. Many of these sections have various subdistricts, such as Little Boston in Branchville, Redding Glen in Redding Ridge, and Umpawaug in West Redding.

Climate[edit]

The town is in a humid continental climate zone (Köppen climate classification: Dfa), with cold, snowy winters and hot, humid summers and four distinct seasons.[39] The United States Department of Agriculture places Redding in plant hardiness zone 6b.[40] Summer high temperatures average in the lower 80s Fahrenheit (upper 20s Celsius), with lows averaging in the lower 60s F (upper 10s C).[41]

Topography[edit]

Redding's topography is dominated by three ridges, running north to south, with intervening valleys featuring steep slopes and rocky ledges in some sections. The highest elevation is about 830 feet above sea level, on Sunset Hill in the northeast part of the town;[42] and the low elevation is about 290 feet above sea level at the Saugatuck Reservoir along the southern border.

Four streams flow south through Redding toward Long Island Sound: the Aspetuck River, the Little River, the Norwalk River and the Saugatuck River.[43]

The Saugatuck River flows through the Saugatuck Reservoir, Redding's largest body of water which stretches south into Weston. The reservoir was created in 1938 through the flooding of a portion of the Saugatuck River Valley.[44]

Demographics[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 1,503 | — | |

| 1800 | 1,632 | 8.6% | |

| 1810 | 1,717 | 5.2% | |

| 1820 | 1,678 | −2.3% | |

| 1830 | 1,686 | 0.5% | |

| 1840 | 1,674 | −0.7% | |

| 1850 | 1,754 | 4.8% | |

| 1860 | 1,652 | −5.8% | |

| 1870 | 1,624 | −1.7% | |

| 1880 | 1,540 | −5.2% | |

| 1890 | 1,546 | 0.4% | |

| 1900 | 1,426 | −7.8% | |

| 1910 | 1,617 | 13.4% | |

| 1920 | 1,315 | −18.7% | |

| 1930 | 1,599 | 21.6% | |

| 1940 | 1,758 | 9.9% | |

| 1950 | 2,037 | 15.9% | |

| 1960 | 3,359 | 64.9% | |

| 1970 | 5,590 | 66.4% | |

| 1980 | 7,272 | 30.1% | |

| 1990 | 7,927 | 9.0% | |

| 2000 | 8,270 | 4.3% | |

| 2010 | 9,158 | 10.7% | |

| 2020 | 8,765 | −4.3% | |

| Population 1774–2000[45] | |||

As of the census of 2010,[46] there were 9,158 people, 3,470 households, and 2,593 families residing in the town. Redding has the third lowest population density in Fairfield County[47] at 285.3 people per square mile (110.2/km2). Between 2000 and 2010, Redding's population increased 10.7%.[48]

There were 3,811 housing units as of 2010, up 23.5% from a decade earlier, for an average density of 118.7 units per square mile (45.8/km2).[49]

The racial makeup of the town as of 2010 was 94.90% White, 0.70% African American, 0.10% Native American, 2.20% Asian, 2.10% from other races or from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.60% of the population.

Of 3,470 households, 35.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 66.1% were married couples living together, 6.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 25.3% were non-families. Individuals comprised 21.3% of all households, and 12.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.63 and the average family size was 3.07.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 26.0% under the age of 18, 3.2% from 18 to 24, 16.3% from 25 to 44, 36.2% from 45 to 64, and 16.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 46.4 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.4 males.

The median income for a household in 2000 was $104,137, and the median income for a family was $109,250. In 2009, the median family income rose to $141,609.[50] Males had a median income of $77,882 versus $52,250 for females. The per capita income for the town was $50,687. About 1.2% of families and 1.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 2.1% of those under age 18 and 3.5% of those age 65 or over.

Attractions and landmarks[edit]

- Collis P. Huntington State Park with trails for hiking, biking and horseback riding

- Devil's Den Preserve, with trails and views of the Saugatuck Reservoir

- Highstead, an arboretum that cultivates plants in their natural setting, rather than for display

- Ives Trail, hiking trail that traverses part of Redding

- Lonetown Farm Museum, headquarters of the Redding Historical Society

- New Pond Farm, a working farm founded by actress Carmen Mathews that offers camps for children, including disadvantaged youth

- Mark Twain Library, endowed by Redding's most famous resident of 1908–1910

- Putnam Memorial State Park, site of "Connecticut's Valley Forge" during the American Revolutionary War

- John Cambria Homestead, one of the many historical houses built around the time of the American Revolutionary War

Culture[edit]

Literature[edit]

Mark Twain: A Biography was authored by West Redding resident Albert Bigelow Paine after interviews with Samuel Clemens at his Stormfield residence, along with subsequent books on Clemens' life.[51]

My Brother Sam Is Dead, authored by James Lincoln Collier and Christopher Collier and named a Newbery Honor Book in 1975, was set in Redding during the Revolutionary War.[52]

Secrets of Redding Glen, a children's book written and illustrated by Jo Polseno, chronicles the natural cycle of wildlife along a section of the Saugatuck River.[53]

Movies filmed at least in part in Redding[edit]

- A Georgetown Story (2005–2008) – filmed in Georgetown.[54]

- The Last House on the Left (1972) – directorial debut of Wes Craven[55]

- Old Dogs (2007–2008) – filmed in Redding Community Center, Putnam Park[56]

- Other People's Money (1991) – filmed in Georgetown[57]

- Rachel, Rachel (1968) – filmed in Georgetown, directorial debut of Paul Newman[58]

- Reckless (1995) – filmed in Georgetown[57]

- Revolutionary Road[56]

- The Stepford Wives (1975)[59]

- Valley of the Dolls (1967) – filmed in Redding Center[60]

Visual arts[edit]

Multiple works by the sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington are on display in Redding, including "Mother Bear and Cubs" and "Sculpture of Wolves" at the entrance to Collis P. Huntington State Park; "General Israel Putnam" at the entrance to Putnam Memorial State Park; "Fighting Stallions" at Redding Elementary School; "A Tribute to the Workhorse" at John Read Middle School; and a smaller version of "The Torch Bearers" at the Mark Twain Library, the original on display in Madrid, Spain.

In its collections, catalogs and archives, the Smithsonian Institution lists at least eight artistic works depicting Redding or located there: Huntington's "Fighting Stallions," "Israel Putnam," "Mother Bear and Cubs" and "Sculpture of Wolves"; the paintings "Landscape, Redding Centre" and "Redding Centre, Conn." by Oronzio Maldarelli; the painting "Rainstorm - Cider Mill at Redding, Connecticut" by George Harvey; and the photo print "Burlingame Garden", photographer not listed.[61]

Redding Ridge artist Dennis Luzak designed a block of commemorative stamps titled "International Youth Year" and issued October 7, 1985, by the U.S. Postal Service.[62] West Redding artist Fred Otnes designed five stamps issued April 22, 2008, depicting journalists.[63]

Mark Twain Library holds an annual art show as a fundraiser, which draws artists from throughout the Northeast to exhibit works, and displays varying works of art and historic objects throughout the year.[64] In 2008, the library received on loan the Gary Lee Price sculpture "Ever the Twain Shall Meet," depicting Twain in the company of Tom Sawyer and Becky Thatcher, two fictional characters he created.[65]

Performing arts[edit]

The composer Charles Ives titled the second movement of his "Three Places in New England (Orchestral Set No. 1)" as "Putnam's Camp, Redding Connecticut." The composition is renowned for Ives attempt to produce an auditory experience akin to that experienced by a child at a parade, borrowing elements of several patriotic songs including "Yankee Doodle Dandy" and employing orchestral techniques to approximate the parade experience, for instance the sound of a band approaching while playing a song even as another recedes into the distance playing a different tune.[66]

Composer Paul Avgerinos won the 2016 Grammy Award for best new age artist for his album "Grace".[67]

Redding sponsors free "Concerts on the Green" Sundays from June to August, which draw varied music acts from throughout the area.

Economy[edit]

Redding Lifecare, which in 2001 opened a retirement community called Meadow Ridge, was Redding's largest private-sector employer as of 2013 with 325 workers;[68] and the largest property holder as ranked by property taxes paid, according to data published by the Connecticut Economic Resource Center (CERC). As of 2013, the town's next largest organizational taxpayers were Northeast Utilities subsidiary Connecticut Light & Power, which in 2015 became known as Eversource Energy; the Redding Country Club; and Aquarion Water Co.

In 2013, 260 organizations in Redding employed 1,678 people, according to the most recent data posted by CERC.[69] Retail sales tax revenue totaled $75.3 million from 433 entities that reported receipts, according to the Connecticut Department of Revenue Services.[70]

Education[edit]

Public schools[edit]

Joel Barlow High School, opened in 1959 and expanded in 1971,[71] serves both Redding and Easton and is designated Regional School District 09[72] by the state of Connecticut. John Read Middle School, opened in 1966 and expanded in 1999, educates Redding students from fifth through eighth grade and was named a National Blue Ribbon School in 2012, among 269 schools nationally that year to receive the designation.[73] Redding Elementary School, opened in 1948 and expanded in 1957, educates students from pre-kindergarten to fourth grade.

Mark Twain Library[edit]

Samuel Clemens (known by his pen name Mark Twain), who lived in Redding from 1908 until his death in 1910, contributed the first books for what would become the Mark Twain Library. The Mark Twain Library Association has retained some 200 of the original 3,000 volumes Clemens donated, along with other artifacts he owned.[74]

Government[edit]

| Year | Democratic | Republican | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 64.14% 3,829 | 34.37% 2,052 | 1.49% 89 |

| 2016 | 56.99% 3,127 | 38.05% 2,088 | 4.96% 272 |

| 2012 | 52.08% 2,787 | 46.78% 2,503 | 1.14% 61 |

| 2008 | 57.80% 3,245 | 41.31% 2,319 | 0.89% 50 |

| 2004 | 51.18% 2,797 | 47.37% 2,589 | 1.45% 79 |

| 2000 | 45.90% 2,151 | 48.14% 2,256 | 5.95% 279 |

| 1996 | 42.38% 1,850 | 48.41% 2,113 | 9.21% 402 |

| 1992 | 36.33% 1,789 | 42.45% 2,090 | 21.22% 1,045 |

| 1988 | 34.64% 1,534 | 64.59% 2,860 | 0.77% 34 |

| 1984 | 29.26% 1,225 | 70.55% 2,953 | 0.19% 8 |

| 1980 | 25.15% 985 | 60.73% 2,378 | 14.12% 553 |

| 1976 | 35.52% 1,220 | 63.78% 2,191 | 0.70% 24 |

| 1972 | 32.87% 1,009 | 65.21% 2,002 | 1.92% 59 |

| 1968 | 33.66% 820 | 60.22% 1,467 | 6.12% 149 |

| 1964 | 50.88% 1,011 | 49.12% 976 | 0.00% 0 |

| 1960 | 30.92% 569 | 69.08% 1,271 | 0.00% 0 |

| 1956 | 24.61% 392 | 75.39% 1,201 | 0.00% 0 |

Redding has an open town meeting form of government. A three-person, popularly elected board of selectmen performs day-to-day administration of the town, with executive authority vested in the first selectman. Legislative authority is vested in the Town Meeting. All town residents aged 18 and over who own property worth at least $1,000 can participate in the Town Meeting, which is held on an as needed basis.

Municipal elections are held every odd-numbered year. In addition to the board of selectmen, other elected town positions include the town clerk, treasurer, tax collector, constables, and members of various boards. In 2013, Democrat Julia Pemberton was elected first selectman, replacing Republican Natalie Ketcham who did not run for reelection after holding the position since 1999.[76]

Redding is part of Connecticut's 4th congressional district and is currently represented by Democratic U.S. Representative Jim Himes.

The town is included in Connecticut's 26th Senatorial District, held by State Senator Will Haskell, a Democrat. Portions of Redding are in Connecticut's 135th Assembly District, held by State Representative Anne Hughes, a Democrat; and Connecticut's 2nd Assembly District, held by State Representative Raghib Allie-Brennan, a Democrat.

Federally, Redding is the only town in Fairfield County to have voted against Republican George W. Bush in 2004 after voting for him in 2000.[77][78]

| Voter registration and party enrollment as of October 26, 2021[79] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Active voters | Inactive voters | Total voters | Percentage | |

| Democratic | 2,520 | 308 | 2,828 | 36.59% | |

| Republican | 1,654 | 276 | 1,930 | 24.97% | |

| Unaffiliated | 2,278 | 533 | 2,811 | 36.37% | |

| Minor parties | 137 | 22 | 159 | 2.07% | |

| Total | 6,589 | 1,139 | 7,728 | 100% | |

Notable people[edit]

In part due to its relative proximity to New York City,[80] many famous people have lived in Redding.

Actors and directors who have resided in Redding include Hope Lange,[81] Barry Levinson,[82] Jessica Tandy and her spouse Hume Cronyn,[81] and Christopher Walken.

Artists who have lived in Redding include Dan Beard, whose illustrations appeared in books authored by Mark Twain;[81] Anna Hyatt Huntington, who lived on the property that today is Collis P. Huntington State Park;[83] and photographer Edward Steichen, who purchased a farm that he called Umpawaug.[84] living there until his death in 1973.[85] Steichen's property became Topstone Park,[86] open seasonally to this day.[87]

Athletes who have lived in Redding include Charlie Morton,[88] a pitcher for the Atlanta Braves; and Brooklee Han, a figure skater who represented Australia in the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia.

Authors who have lived in Redding include Joel Barlow,[89] a poet and diplomat, born in town; Samuel Clemens, who in 1908 moved into a mansion dubbed Stormfield that was built on land located on present-day Mark Twain Lane and lived there until his death in 1910; Howard Fast;[81] Lawrence Kudlow, author and host of the "Kudlow and Company" television program;[90] Dick Morris, political consultant and author; Flannery O'Connor (who wrote her novel Wise Blood while a boarder at the home of fellow writer Robert Fitzgerald);,[91] futurist Alvin Toffler[92] and economist Stuart Chase, who lived in Redding from 1930 and served on the town's planning commission from 1956 until his death in 1985.[93]

Businesspeople who have lived in Redding include Alfred Winslow Jones, credited by some as "the father" of the hedge fund industry.[81]

Composers, musicians and singers who have lived in Redding include Leonard Bernstein,[94] Daryl Hall,[81] Jascha Heifetz,[81] Charles Ives,[81] Meat Loaf, Andy Powell and Mary Travers.[95]

Transportation[edit]

Metro-North Railroad's Danbury Branch has a station at West Redding.[96] The Danbury Branch provides commuter rail service between Danbury, to South Norwalk, Stamford, and Grand Central Terminal in New York City. Housatonic Area Regional Transit provides local bus service.

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Redding town, Fairfield County, Connecticut". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ "Indian Trails in and around Redding". History of Redding, Connecticut (CT) Past & Present. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "English Settlement at Uncoway". Town of Fairfield, Connecticut. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NRHP/92001253_text "National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet, Redding Center Historic District," U.S. Department of the Interior, October 1, 1992. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Grumman, William Edgar (1904). The revolutionary soldiers of Redding, Connecticut, and the record of their services. Hartford press: The Case, Lockwood & Brainard company. hdl:2027/yale.39002007175780.

- ^ Google (August 14, 2019). "Redding, CT's Oblong" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Early Settlement of Redding". History of Redding, Connecticut (CT) Past & Present. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ The Connecticut Magazine: An Illustrated Monthly. Connecticut Magazine Company. 1903. p. 334.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form Umpawaug District School". NPGallery Digital Asset Management System. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ "Post Offices". Town of Redding, Connecticut Official Website. August 1, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Redding". Connecticut History. September 13, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Prince, Cathryn J. (July 11, 2013). "Taking to Devil's Den". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Poirier, David A. (1976). "Camp Reading: Logistics of a Revolutionary War Winter Encampment". Northeast Historical Archaeology. 5 (1): 40–52. doi:10.22191/neha/vol5/iss1/5. ISSN 0048-0738.

- ^ "Park History". Putnam Memorial State Park. March 20, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Johnson, James M.; Pryslopski, Christopher; Villani, Andrew (August 1, 2013). Key to the Northern Country: The Hudson River Valley in the American Revolution. SUNY Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-4384-4814-5.

- ^ Bailey, James Montgomery (1896). History of Danbury, Conn., 1684-1896. Burr Print. House.

- ^ Pawlowski, John A Sr. (2010). "The Industrial Might of Connecticut Pegmatite". Connecticut History. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Shainin, Vincent E. (August 1, 1946). "The Branchville, Connecticut, Pegmatite". American Mineralogist. 31 (7–8): 329–345. ISSN 0003-004X.

- ^ Agar, W. M.; Krieger, P. (1932). "Garnet rock near West Redding, Connecticut". American Journal of Science. s5-24 (139): 68–80. Bibcode:1932AmJS...24...68A. doi:10.2475/ajs.s5-24.139.68. ISSN 0002-9599.

- ^ "History of Gilbert & Bennett in Georgetown, Connecticut". History of Redding, Connecticut (CT) Past & Present. December 15, 1947. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NRHP/87000343_text "National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, Georgetown Historic District, Georgetown, Connecticut," U.S. Department of the Interior, March 9, 1987. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ "G & B LAGOON". yosemite.epa.gov. April 26, 2014. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Gilbert & Bennett Wire Mill Renovation & Redevelopment News in Georgetown, Connecticut". History of Redding, Connecticut (CT) Past & Present. February 20, 2010. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Houses in Redding - Listed in State of Connecticut Historic Resource Inventory" (PDF). Town of Redding, Connecticut Official Website. January 21, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 2, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Houses in Redding - Houses 1900 and Earlier, NOT LISTED on State of Connecticut Historic Resource Inventory" (PDF). Town of Redding, Connecticut Official Website. January 21, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 2, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "COVID-19 Update June 30, 2020" (PDF). The State of Connecticut Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). June 30, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". CT.gov. June 30, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Statewide Claims Profile - State of Connecticut". Connecticut Department of Labor. June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Residents help clean up after Hurricane Sandy". The Redding Pilot. November 3, 2012. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Report on Transmission Facility Outages during Northeast Snowstorm of October 29-30, 2011: Causes and Recommendations" (PDF). Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Springer, John; Williams, Thomas D. (April 30, 1995). "Suspect in Killing of 5 'No Different' than Others". courant.com. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Springer, John (April 25, 1998). "Landlord Guilty in Murders". courant.com. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Jones, Mark (July 12, 2014). "The Connecticut Floods of 1955". cslib.org. Archived from the original on July 12, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Cruson, Daniel (August 19, 1955). "The Flood of 1955 Pictures". History of Redding, Connecticut (CT) Past & Present. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Our Katrina: Looking back on the Hurricane of 1938". NewsTimes. September 21, 2008. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Helman, Christopher (October 29, 2012). "Where Will Sandy Rank Among These Worst U.S. Storms Of All Time?". Forbes. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Henderson-Shifflett, Jeannine (March 14, 2017). "Blizzard of 1888 Devastates State". Connecticut History. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2013". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L.; McMahon, T. A. "World Map of Köppen-Geiger climate classification". The University of Melbourne. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ United States Department of Agriculture. "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". United States National Arboretum. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ "Redding, CT Monthly Weather". The Weather Channel. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ "Newtown". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ "History of Land Use in Redding, CT". Housatonic Valley Council of Elected Officials. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ "Valley Forge Forever Gone". Aspetuck Land Trust. 2009. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ "Connecticut State Register Manual". Connecticut's Official State Website. September 21, 2013. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Redding town, Fairfield County, Connecticut". Census Bureau QuickFacts. December 21, 2010. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Population, Land Area and Density by Location". Connecticut Department of Economic and Community Development. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ "Connecticut: 2010 Population and Housing Unit Counts" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. June 2012. p. 20. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- ^ Connecticut: 2010 Population and Housing Unit Counts.

- ^ "6-Figure Towns". CNN. July 21, 2009.

- ^ "Albert B. Paine, 76, Biographer, Dead." The New York Times April 10, 1937: 19.

- ^ "historyofredding.com". ww38.historyofredding.com.

- ^ "Redding Land Trust, Inc :: Redding, Connecticut". Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2014. "In Tribute," Redding Land Trust. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ^ Bruen, Melissa (June 4, 2009). "Georgetown, seen through the eyes of history". Danbury NewsTimes. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Last House on the Left". Courant.com. July 13, 2014. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Jump up to: a b Cedrone, Sarajane (March 1, 2017). "Connecticut's Star Turn in Film". Connecticut Explored. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Gilbert & Bennett Wire Mill, Georgetown". cultureandtourism.org. November 10, 2005. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Monush, Barry (2009). Everybody's Talkin': The Top Films of 1965-1969. Applause Theatre & Cinema Books. p. 254. ISBN 978-1-55783-618-2.

- ^ "The Stepford Wives". Courant.com. May 2, 2014. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Valley Of The Dolls". Courant.com. May 2, 2014. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Search results for: redding, connecticut". Collections Search Center, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved August 14, 2019..

- ^ "International Youth Year Issue". Arago. October 7, 1985. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "American Journalists Issue". Arago. April 22, 2008. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Art Show". Mark Twain Library. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "'Ever the Twain Shall Meet': Sculpture on loan to Redding library". NewsTimes. August 12, 2008. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Iverson, Jennifer (2011). "Creating Space" (PDF). Music Theory Online. 17 (2). doi:10.30535/mto.17.2.3. ISSN 1067-3040.

- ^ "2016 Grammy Awards: Complete list of winners and nominees". Los Angeles Times. February 16, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Major Employers 2013 in Greater Danbury, CT with Employment Estimated at 75+" (PDF). Housatonic Valley Council of Elected Officials. March 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 30, 2013. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Redding" (PDF). CERC Town Profile. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 8, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "2013 Retail Sales By Town ALL NAICS | Connecticut Data". data.ct.gov. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "History". Town of Redding, Connecticut Official Website. February 25, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Joel Barlow High School in Redding, CT". GreatSchools.org. March 5, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "John Read Middle School is named a 2012 National Blue Ribbon School". The Redding Pilot. September 7, 2012. Archived from the original on April 24, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Samuel Clemens and the Mark Twain Library :: Redding, Connecticut". Archived from the original on September 4, 2011. Retrieved September 15, 2011. "Samuel Clemens and the Mark Twain Library," Mark Twain Library. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ "General Elections Statement of Vote 1922". CT.gov - Connecticut's Official State Website.

- ^ Pirro, John (November 6, 2013). "Pemberton wins in Redding". Danbury NewsTimes. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ https://authoring.ct.gov/-/media/SOTS/ElectionServices/StatementOfVote_PDFs/2000SOVpdf.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ https://authoring.ct.gov/-/media/SOTS/ElectionServices/StatementOfVote_PDFs/2004SOVpdf.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Registration and Party Enrollment Statistics as of October 26, 2021" (PDF). Connecticut Secretary of State. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Lefkowitz, Melanie (April 14, 2014). "Redding, Twain's Last Home, Is Proud of Privacy". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "An Impressive List of Individuals Who Have Called Redding Home". History of Redding, Connecticut (CT) Past & Present. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Barry Levinson". IMDb. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Cullen-DuPont, Kathryn (May 14, 2014). Encyclopedia of Women's History in America. Infobase Publishing. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-4381-1033-2.

- ^ Niven, Penelope (1997). Steichen: A Biography. New York: Clarkson Potter. ISBN 0-517-59373-4, p. 530

- ^ Niven (1997), p. 698

- ^ Prevost, Lisa, the New York Times, "An Upscale Town With Upcountry Style," January 3, 1999

- ^ "Topstone Park". townofreddingct.org. June 28, 2011. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Barlow Hall of Fame inducts 19". The Redding Pilot. November 30, 2015. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Mulford, Carla J. (June 16, 2017). Barlow, Joel (1754-1812), businessman, diplomat, and poet. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1600077. ISBN 978-0-19-860669-7. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Larry Kudlow to speak at annual breakfast - The Redding Pilot". thereddingpilot.com. October 25, 2014. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "When Flannery O'Connor didn't live here". The Ridgefield Press. April 30, 2014. Archived from the original on April 30, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Happy Birthday To Redding's Alvin Toffler!". Westport Daily Voice. Weston, Connecticut. October 4, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- ^ http://stevenlewis.info/gs/Stuart_Chase_bio.htm | Stuart Chase -- A Biography | accessed March 15, 2020

- ^ Gottlieb, Jack (2010). Working with Bernstein: A Memoir. Amadeus Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-57467-186-5.

- ^ Grimes, William (September 16, 2009). "Mary Travers, Singer of Protest Anthems, Dies at 72". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ http://as0.mta.info/mnr/stations/station_detail.cfm?key=276 "Metro North Railroad Home > Stations Redding," MTA.com. Retrieved May 4, 2014.

Further reading[edit]

- Grumman, William Edgar (1904). The revolutionary soldiers of Redding, Connecticut, and the record of their services;. Hartford press: The Case, Lockwood & Brainard company.

- Todd, Charles Burr (1906). The history of Redding, Connecticut : from its first settlement to the present time. New York: Grafton Press.

External links[edit]

- Town of Redding official website

- History of Redding

- Easton Redding Region 9 school district

- Mark Twain Library, the town public library