3D computer graphics

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2017) |

| Three-dimensional (3D) computer graphics |

|---|

|

| Fundamentals |

| Primary uses |

| Related topics |

3D computer graphics, sometimes called CGI, 3-D-CGI or three-dimensional computer graphics, are graphics that use a three-dimensional representation of geometric data (often Cartesian) that is stored in the computer for the purposes of performing calculations and rendering digital images, usually 2D images but sometimes 3D images. The resulting images may be stored for viewing later (possibly as an animation) or displayed in real time.

3-D computer graphics, contrary to what the name suggests, are most often displayed on two-dimensional displays. Unlike 3-D film and similar techniques, the result is two-dimensional, without visual depth. More often, 3-D graphics are being displayed on 3-D displays, like in virtual reality systems.

3-D graphics stand in contrast to 2-D computer graphics which typically use completely different methods and formats for creation and rendering.

3-D computer graphics rely on many of the same algorithms as 2-D computer vector graphics in the wire-frame model and 2-D computer raster graphics in the final rendered display. In computer graphics software, 2-D applications may use 3-D techniques to achieve effects such as lighting, and similarly, 3-D may use some 2-D rendering techniques.

The objects in 3-D computer graphics are often referred to as 3-D models. Unlike the rendered image, a model's data is contained within a graphical data file. A 3-D model is a mathematical representation of any three-dimensional object; a model is not technically a graphic until it is displayed. A model can be displayed visually as a two-dimensional image through a process called 3-D rendering, or it can be used in non-graphical computer simulations and calculations. With 3-D printing, models are rendered into an actual 3-D physical representation of themselves, with some limitations as to how accurately the physical model can match the virtual model.[1]

History[edit]

William Fetter was credited with coining the term computer graphics in 1961[2][3] to describe his work at Boeing. An early example of interactive 3-D computer graphics was explored in 1963 by the Sketchpad program at Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Lincoln Laboratory.[4] One of the first displays of computer animation was Futureworld (1976), which included an animation of a human face and a hand that had originally appeared in the 1971 experimental short A Computer Animated Hand, created by University of Utah students Edwin Catmull and Fred Parke.[5]

3-D computer graphics software began appearing for home computers in the late 1970s. The earliest known example is 3D Art Graphics, a set of 3-D computer graphics effects, written by Kazumasa Mitazawa and released in June 1978 for the Apple II.[6][7]

Overview[edit]

3-D computer graphics production workflow falls into three basic phases:

- 3-D modeling – the process of forming a computer model of an object's shape

- Layout and CGI animation – the placement and movement of objects (models, lights etc.) within a scene

- 3-D rendering – the computer calculations that, based on light placement, surface types, and other qualities, generate (rasterize the scene into) an image

Modeling[edit]

The model describes the process of forming the shape of an object. The two most common sources of 3-D models are those that an artist or engineer originates on the computer with some kind of 3D modeling tool, and models scanned into a computer from real-world objects (Polygonal Modeling, Patch Modeling and NURBS Modeling are some popular tools used in 3-D modeling). Models can also be produced procedurally or via physical simulation. Basically, a 3-D model is formed from points called vertices that define the shape and form polygons. A polygon is an area formed from at least three vertices (a triangle). A polygon of n points is an n-gon.[8] The overall integrity of the model and its suitability to use in animation depend on the structure of the polygons.

Layout and animation[edit]

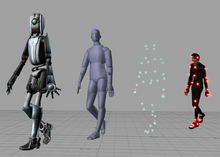

Before rendering into an image, objects must be laid out in a 3D scene. This defines spatial relationships between objects, including location and size. Animation refers to the temporal description of an object (i.e., how it moves and deforms over time. Popular methods include keyframing, inverse kinematics, and motion-capture). These techniques are often used in combination. As with animation, physical simulation also specifies motion.

Materials and textures[edit]

Materials and textures are properties that the render engine uses to render the model. One can give the model materials to tell the render engine how to treat light when it hits the surface. Textures are used to give the material color using a color or albedo map, or give the surface features using a bump map or normal map. It can be also used to deform the model itself using a displacement map.

Rendering[edit]

Rendering converts a model into an image either by simulating light transport to get photo-realistic images, or by applying an art style as in non-photorealistic rendering. The two basic operations in realistic rendering are transport (how much light gets from one place to another) and scattering (how surfaces interact with light). This step is usually performed using 3-D computer graphics software or a 3-D graphics API. Altering the scene into a suitable form for rendering also involves 3-D projection, which displays a three-dimensional image in two dimensions. Although 3-D modeling and CAD software may perform 3-D rendering as well (e.g., Autodesk 3ds Max or Blender), exclusive 3-D rendering software also exists (e.g., OTOY's Octane Rendering Engine, Maxon's Redshift)

- Examples of 3-D rendering

-

A 3-D model of a Dunkerque-class battleship rendered with flat shading

-

During the 3-D rendering step, the number of reflections "light rays" can take, as well as various other attributes, can be tailored to achieve a desired visual effect. Rendered with Cobalt.

-

A 3-D rendering of a penthouse

Software[edit]

3-D computer graphics software produces computer-generated imagery (CGI) through 3-D modeling and 3-D rendering or produces 3-D models for analytic, scientific and industrial purposes.

File formats[edit]

There are many varieties of files supporting 3-D graphics, for example, Wavefront .obj files and .x DirectX files. Each file type generally tends to have its own unique data structure.

Each file format can be accessed through their respective applications, such as DirectX files, and Quake. Alternatively, files can be accessed through third-party standalone programs, or via manual decompilation.

Modeling[edit]

3-D modeling software is a class of 3-D computer graphics software used to produce 3-D models. Individual programs of this class are called modeling applications or modelers.

3-D modeling starts by describing 3 display models : Drawing Points, Drawing Lines and Drawing triangles and other Polygonal patches.[9]

3-D modelers allow users to create and alter models via their 3-D mesh. Users can add, subtract, stretch and otherwise change the mesh to their desire. Models can be viewed from a variety of angles, usually simultaneously. Models can be rotated and the view can be zoomed in and out.

3-D modelers can export their models to files, which can then be imported into other applications as long as the metadata are compatible. Many modelers allow importers and exporters to be plugged-in, so they can read and write data in the native formats of other applications.

Most 3-D modelers contain a number of related features, such as ray tracers and other rendering alternatives and texture mapping facilities. Some also contain features that support or allow animation of models. Some may be able to generate full-motion video of a series of rendered scenes (i.e. animation).

Computer-aided design (CAD)[edit]

Computer aided design software may employ the same fundamental 3-D modeling techniques that 3-D modeling software use but their goal differs. They are used in computer-aided engineering, computer-aided manufacturing, Finite element analysis, product lifecycle management, 3D printing and computer-aided architectural design.

Complementary tools[edit]

After producing a video, studios then edit or composite the video using programs such as Adobe Premiere Pro or Final Cut Pro at the mid-level, or Autodesk Combustion, Digital Fusion, Shake at the high-end. Match moving software is commonly used to match live video with computer-generated video, keeping the two in sync as the camera moves.

Use of real-time computer graphics engines to create a cinematic production is called machinima.[10]

Other types of 3D appearance[edit]

Photorealistic 2D graphics[edit]

Not all computer graphics that appear 3D are based on a wireframe model. 2D computer graphics with 3D photorealistic effects are often achieved without wireframe modeling and are sometimes indistinguishable in the final form. Some graphic art software includes filters that can be applied to 2D vector graphics or 2D raster graphics on transparent layers. Visual artists may also copy or visualize 3D effects and manually render photorealistic effects without the use of filters.

2.5D[edit]

Some video games use 2.5D graphics, involving restricted projections of three-dimensional environments, such as isometric graphics or virtual cameras with fixed angles, either as a way to improve performance of the game engine or for stylistic and gameplay concerns. By contrast, games using 3D computer graphics without such restrictions are said[by whom?] to use true 3D.

See also[edit]

- Glossary of computer graphics

- Comparison of 3D computer graphics software

- Graphics processing unit (GPU)

- Graphical output devices

- List of 3D computer graphics software

- List of 3D modeling software

- List of 3D rendering software

- Real-time computer graphics

- Reflection (computer graphics)

- Rendering (computer graphics)

Fields of use

- 3D data acquisition and object reconstruction

- 3D motion controller

- 3D projection on 2D planes

- 3D reconstruction

- 3D reconstruction from multiple images

- Anaglyph 3D

- Cel shading

- Computer animation

- Computer vision

- Digital geometry

- Digital image processing

- Game development tool

- Game engine

- Geometry pipelines

- Geometry processing

- Graphics

- Isometric graphics in video games and pixel art

- Level editor

- List of stereoscopic video games

- Medical animation

- Render farm

- SIGGRAPH

- Stereoscopy

- Timeline of computer animation in film and television

- Video game graphics

References[edit]

- ^ "3D computer graphics". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2019-01-19.

- ^ "An Historical Timeline of Computer Graphics and Animation". Archived from the original on 2008-03-10. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- ^ "Computer Graphics". Learning Computer History. 5 December 2004.

- ^ Ivan Sutherland Sketchpad Demo 1963, retrieved 2023-04-25

- ^ "Pixar founder's Utah-made Hand added to National Film Registry". The Salt Lake Tribune. December 28, 2011. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- ^ "Brutal Deluxe Software". www.brutaldeluxe.fr.

- ^ "Retrieving Japanese Apple II programs". Projects and Articles. neoncluster.com. Archived from the original on 2016-10-05.

- ^ Simmons, Bruce. "n-gon". MathWords. Archived from the original on 2018-12-15. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- ^ Buss, Samuel R. (2003-05-19). 3D Computer Graphics: A Mathematical Introduction with OpenGL. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-44038-7.

- ^ "Machinima". Internet Archive. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

External links[edit]

- A Critical History of Computer Graphics and Animation (Wayback Machine copy)

- How Stuff Works - 3D Graphics

- History of Computer Graphics series of articles (Wayback Machine copy)

- How 3D Works - Explains 3D modeling for an illuminated manuscript