Завтра солнце

| Завтра солнце | |

|---|---|

| |

| Самая высокая точка | |

| Координаты | 22 ° 25′35 ″ S 67 ° 45′35 ″ W / 22,42639 ° S 67,75972 ° W [ 1 ] |

| География | |

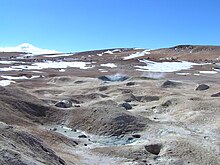

Sol de Mañana - это область с геотермальными проявлениями в южной Боливии, включая фумаролы , горячие источники и грязные бассейны. Он находится на высоте около 4900 метров (16 100 футов), к югу от Лагуна Колорада и к востоку от Эль -Татио геотермального поля . Поле расположено в Национальном заповеднике Фауны Эдуардо Авароа Андес и является важной туристической достопримечательностью на дороге между Уюни и Антофагаста . Эта область была проведена в качестве возможного места производства геотермальной энергетики, с исследованиями, начиная с 1970 -х годов и после того, как в 2010 году решает пауза. Разработка продолжается с 2023 года. [update].

Описание

[ редактировать ]Завтра солнце лежит в муниципалитете Сан -Пабло де Лапец ( провинция Sud Lipez ), [ 2 ] в отдаленном и необитаемом регионе Боливии. [ 3 ] В площади 10 квадратных километров (3,9 кв. Миль) [ 4 ] Есть паровые вентиляционные отверстия, грязевые бассейны , горячие источники , гейзеры и фумароли . [ 5 ] [ 4 ] Помимо самого Сол-де Мьяна, есть дополнительные геотермальные проявления, рассеянные несколько километров юго-юго-запад [6] at Apacheta[7] and 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) from Sol de Mañana;[4] north-northwest at Huayllajara;[7] The first two feature hydrothermally altered rocks[6] and sometimes they are considered to be separate geothermal fields.[8]

Steam/water emissions can under exceptional circumstances reach heights of 200 metres (660 ft). Gas vents release sulfur-containing gases.[9] The temperatures of the springs reach 30 °C (86 °F) and the fumaroles 70 °C (158 °F),[1] hot enough to be visible from space in ASTER images. Seismic swarms and earthquakes have been recorded in the field.[10] Sol de Mañana lies at about 4,900 metres (16,100 ft) elevation,[11] making it among the highest geothermal fields in the world.[12]

The nearest major communities are Quetena Grande and Quetena Chico in Bolivia, 75 kilometres (47 mi) northeast from Sol de Mañana,[13] and the field can be accessed through unpaved roads from Uyuni,[14] 340 kilometres (210 mi) away.[15] 30 kilometres (19 mi)[16] across the frontier, in Chile, lies El Tatio, the best-known geothermal manifestation in the Central Andes.[17] There are numerous volcanoes in the area, including Tocorpuri west-southwest and Putana and Escalante southwest of Sol de Mañana,[7] and the Pastos Grandes and Cerro Guacha caldera systems.[4] The field lies 40 kilometres (25 mi)[18]-20 kilometres (12 mi) south of Laguna Colorada,[19] which can be reached from Sol de Mañana.[19] There are mines at Cerro Aguita Blanca, a few kilometres south of Sol de Mañana, and at Cerro Apacheta about five kilometres west-southwest;[6] the latter can be reached through another road from Sol de Mañana.[20]

Geology

[edit]Off the western coast of South America, the Nazca Plate subducts beneath the South American Plate.[21] The subduction is responsible for the volcanism of the Andes.[19] The growth of the Altiplano high plateau commenced 25 million years ago before shifting eastward 12-6 million years ago.[6]

The Andean Central Volcanic Zone is one of four belts of volcanoes in the Andes.[21] Volcanic activity began 23 million years ago and involved the emplacement of a series of ignimbrites, which form one of the largest ignimbrite plateaus of the world. Numerous younger stratovolcanoes grew on top of the ignimbrites; there are about 150 separate volcanic centres. The Altiplano volcanoes form the Altiplano-Puna volcanic complex, which is underpinned by the Altiplano-Puna Magma Body[a].[6] The dry climate leads to an exceptional preservation of the volcanic landforms.[21] About 50 volcanoes in the Central Andes (Bolivia, northern Chile, northern Argentina) were active during the Holocene.[22]

Local

[edit]

Sol de Mañana is part of the Laguna Colorada geothermal area[9]/caldera complex[23] (the names are sometimes used interchangeably).[11] The area features Miocene-Pleistocene volcanic rocks (dacite forming ignimbrites[b], lavas and tuffs) emplaced on top of Cenozoic marine sediments. Alluvial deposits and moraines occur in the area. There are various north-south and northwest–southeast trending tectonic lineaments in the region,[6] associated with rock deformation.[25] At Sol de Mañana there are a number of faults,[6] including normal faults active during the Holocene,[7] which constitute pathways for the ascent of hot water.[25] The most important faults at the field trend north-northwest-south-southeast.[20] Glacial erosion has taken place in the area during the past,[26] which has left moraines east and north-northwest of Sol de Mañana.[20]

Drill cores have identified several rock units under Sol de Mañana, including several layers of dacitic ignimbrites with ages of about 5-1.2 million years and andesitic lavas. Hydrothermal alteration has taken place throughout the layers, forming from top to bottom layers rich clays, silica and epidote; each of these layers is several hundred metres thick. Basement rocks were not encountered. This stratigraphy is similar to that at El Tatio, across the border in Chile.[27] The geothermal heat reservoir appears to be located within the ignimbrites and andesites.[28]

The heat may originate either in the Altiplano-Puna Magma Body or in the volcanic arc.[29] It is transported upward through convection, forming two heat reservoirs underground that are capped by a clay layer.[30] Precipitation water reaches the reservoirs through deep faults, which also allow heat circulation.[31] Drilling has shown that the reservoirs have temperatures of about 250–260 °C (482–500 °F).[19] The Sol de Mañana geothermal system may be physically connected to El Tatio,[32] with Sol de Mañana being closer to the heat source and Tatio an outflow at lower elevation.[33]

Climate and ecosystem

[edit]There is a weather station on Sol de Mañana.[34] Mean annual precipitation is about 75 millimetres (3.0 in) and mean temperatures are about 8.9 °C (48.0 °F).[13] The geothermal field is part of the Eduardo Avaroa Andean Fauna National Reserve[18] and one of the main tourism attractions on the Uyuni-Antofagasta road.[14]

Geothermal power generation

[edit]The 1973 oil crisis created the impetus for increased investigation of Bolivia's geothermal power resources, focusing on the Altiplano and the surrounding Andean ranges. Prospecting by the National Electricity Company and the state agency for geology identified Sajama, Salar de Empexa and Laguna Colorada as the most suitable areas for geothermal power generation.[9] A geothermal project began in 1978 and numerous drilling operations were undertaken in the following years; however development ceased in 1993 as the legal and political circumstances were unfavourable. A renewed effort began in 2010, spearheaded by the Japan International Cooperation Agency, during which additional cores were drilled, but as of 2023[update] is still at its early stages[35] and as of 2016[update] is only used as process heat for the San Cristobal mine.[14] An electrical power potential of about 50–100 megawatts (67,000–134,000 hp) has been estimated.[19]

Laguna Colorada/Sol de Mañana are the main focus of geothermal power prospecting in Bolivia; other sites have drawn scarce interest.[3] As of 2016[update] Bolivia did not have any legislation specific for geothermal power generation.[36] Geothermal power development is also hindered by the remote location, which would require building large power transmission networks, and the low price of electricity in the country.[14]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Altiplano-Puna Magmatic Body is an accumulation of magma in the crust of the Altiplano.[6]

- ^ Including the Tara Ignimbrite from a supereruption of Cerro Guacha.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b USGS 1992, p. 267.

- ^ Communication Ministry 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bona & Coviello 2016, p. 35.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d De Silva & Francis 1991, p. 170.

- ^ Damir 2014, p. 156.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d De Silva & Francis 1991, p. 171.

- ^ Sullcani 2015, p. 668.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 1.

- ^ Pritchard et al. 2014, p. 98.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 2.

- ^ Müller et al. 2022, p. 3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Suaznabar, Quiroga & Villarreal 2019, p. 2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Bona & Coviello 2016, p. 38.

- ^ Delgadillo & Puente 1998, p. 257.

- ^ Fernandez-Turiel et al. 2005, p. 127.

- ^ Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ministry of Hydrocarbons and Energies 2022, p. 183.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Sullcani 2015, p. 666.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Sullcani 2015, p. 667.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 3.

- ^ Pritchard et al. 2014, p. 90.

- ^ Fernandez-Turiel et al. 2005, p. 128.

- ^ Ort 2009, p. 1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 5.

- ^ Delgadillo & Puente 1998, p. 258.

- ^ Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 19.

- ^ Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 15.

- ^ Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 17.

- ^ Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 18.

- ^ Cortecci et al. 2005, p. 568.

- ^ De Silva & Francis 1991, p. 172.

- ^ Lagos et al. 2023, p. 5.

- ^ Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Bona & Coviello 2016, p. 36.

Sources

[edit]- Bona, Paolo; Coviello, Manlio (April 2016). Valoración y gobernanza de los proyectos geotérmicos en América del Sur: una propuesta metodológica (PDF) (in Spanish). CEPAL.

- Communication Ministry (25 July 2020). "Diputados aprueba financiamiento para construcción de Planta Geotérmica Laguna Colorada" (in Spanish).

- Cortecci, Gianni; Boschetti, Tiziano; Mussi, Mario; Lameli, Christian Herrera; Mucchino, Claudio; Barbieri, Maurizio (2005). "New chemical and original isotopic data on waters from El Tatio geothermal field, northern Chile". Geochemical Journal. 39 (6): 547–571. Bibcode:2005GeocJ..39..547C. doi:10.2343/geochemj.39.547.

- De Silva, Shanaka L.; Francis, Peter (1991). Volcanoes of the central Andes. Vol. 220. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Delgadillo, T. Z.; Puente, Héctor G. (1998). The Laguna Colorada (Bolivia) Project: A Reservoir Engineering Assessment (Report). Transactions-Geothermal Resources Council. pp. 257–262.

- Fernandez-Turiel, J.L.; Garcia-Valles, M.; Gimeno-Torrente, D.; Saavedra-Alonso, J.; Martinez-Manent, S. (October 2005). "The hot spring and geyser sinters of El Tatio, Northern Chile". Sedimentary Geology. 180 (3–4): 125–147. Bibcode:2005SedG..180..125F. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2005.07.005.

- Damir, Galaz-Mandakovic Fernández (2014). "Uyuni, capital turística de Bolivia. Aproximaciones antropológicas a un fenómeno visual posmoderno desbordante". Teoría y Praxis (in Spanish). 16: 147–173.

- Lagos, Magdalena Sofía; Muñoz, José Francisco; Suárez, Francisco Ignacio; Fuenzalida, María José; Yáñez-Morroni, Gonzalo; Sanzana, Pedro (29 June 2023). "Investigating the effects of channelization in the Silala River: A review of the implementation of a coupled MIKE -11 and MIKE-SHE modeling system". WIREs Water. 11. doi:10.1002/wat2.1673.

- Министерство углеводородов и энергий (апрель 2022 г.). Первоначальный отчет об общественной ответственности 2022 (PDF) (отчет) (на испанском).

- Мюллер, Даниэль; Уолтер, Томас Р.; Циммер, Мартин; Гонсалес, Габриэль (1 декабря 2022 года). «Распределение, структурный и гидрологический контроль горячих источников и гейзеров El Tatio, Чили, выявленная с помощью оптического и теплового инфракрасного съемки дронов» . Журнал вулканологии и геотермальных исследований . 432 : 107696. Bibcode : 2022jvgr..43207696M . doi : 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2022.107696 . ISSN 0377-0273 . S2CID 253033476 .

- Орт, Майкл Х. (октябрь 2009 г.). Два новых суперперивации в вулканическом комплексе Альтиплано-Пуна в центральных Андах . 2009 г. Портленд GSA Ежегодное собрание.

- Pereyra Quiroga, Bruno; Meneses Riosose, Эрнесто; матч, Герхард; Брасс, Генрих (1 сентября 2023 г.). «Трехмерная магнитокеллическая инверсия для характеристики высокогорного геотермального поля Sol de Mañana, Боливия » Геотермики 113 : 102748. Биббод : 2023geoth.11302748p . Doi : 10.1016/j.geothermics.2023.102748 . ISSN 0375-6 S2CID 259617984

- Причард, я; Хендерсон, ул.; Джей, JA; Soler, v.; Krzesni, da; Кнопка, NE; Уэлч, доктор медицины; Semple, Ag; Стекло, б.; Sunagua, M.; Minaya, E.; Амиго, А.; Клаверо, Дж. (1 июня 2014 г.). «Исследования разведывания землетрясения в девяти вулканических районах центральных Анд с совпадающими спутниковыми термическими и инсарными наблюдениями» . Журнал вулканологии и геотермальных исследований . 280 : 90–103. Bibcode : 2014jvgr..280 ... 90p . doi : 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2014.05.004 . ISSN 0377-0273 .

- Суэзнабар, Паола Адриана Кока; Бирога, Бруно Перейра; Вильярреал, Хосе Рамон Перес (2019). «Хорошо бурение в геотермальном поле Сол де Маньана - Геотермальный проект Лагуна Колада» (PDF) . GRC Transactions . 43

- Sullcani, Pedro Rómulo Ramos (2015). Анализ данных скважины и объемная оценка геотермального поля Sol de Mañana, Боливия (PDF) . Национальное энергетическое управление (Исландия) (отчет). Университет Организации Объединенных Наций .

- USGS (1992). Геология и минеральные ресурсы Altiplano и Cordillera occidental, Боливия (отчет). doi : 10.3133/b1975 .