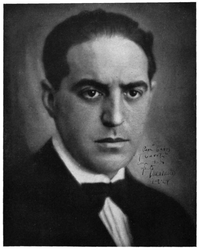

Грегорио Мараньон

Эта статья требует дополнительных цитат для проверки . ( июль 2022 г. ) |

Грегорио Мараньон | |

|---|---|

| |

| Рожденный | 19 мая 1887 года Мадрид , Испания. |

| Умер | 27 марта 1960 г. (72 года) Мадрид, Испания. |

| Национальность | испанский |

| Гражданство | испанский |

| Супруг | Dolores Moya |

| Научная карьера | |

| Поля | Эндокринология Психология Историческое эссе |

| Место k настоящей академии Española | |

| В офисе 8 апреля 1934 - 27 марта 1960 г. | |

| Предшествует | Хуан Армада и Лосада |

| Преуспевает | Сэмюэль Гили Гая |

Gregorio Marsilón y Posadillo , Owl ( [ ɡkaeˈ˫ɬuff ; 19 мая 1887 - 26 марта Женат на Долорес, 1911 год, был 1911 год,

Жизнь и работа

[ редактировать ]Странный, гуманистический и либеральный человек, он считается одним из самых блестящих испанских интеллектуалов 20 -го века. Помимо его эрудиции, он также выделяется своим элегантным литературным стилем. Как и многие другие мыслители своего времени, он участвовал в социальном и политическом плане: он был республиканцем и сражался с диктатурой Мигеля Прима де Риверы (он был осужден в тюрьму на месяц) и проявил свои разногласия с испанским коммунизмом. Более того, он поддержал вторую испанскую республику в его начале, но позже раскритиковал ее из -за отсутствия сплоченности среди испанского народа.

Вероятно, после того, как уйти из Мадрида (около января 1937 года), и когда его спросили его мнение о республиканской Испании, Маранон говорил на собрании французских интеллектуалов следующим образом: « Вам не нужно очень стараться, друзья мои; послушайте это: Восемьдесят восьми процентов учителей из Мадрида, Валенсии и Барселоны (три университета, которые вместе с Мурсией остались на республиканской стороне) были вынуждены изгнать за границу. Красные (коммунисты в Испании), несмотря на то, что многие из угрожаемых интеллектуалов считались левыми людьми ».

В статье «Либерализм и коммунизм», опубликованная в Revue de Paris 15 декабря 1937 года, он ясно выразил свое изменение мнения во второй республике:

[...] В истории есть одна абсолютно запрещенная вещь: судить, что могло произойти, если то, что случилось, не произошло. Но не обсуждается то, что пророчества из крайних правых или монархических сторон, которые против Республики были полностью исполнены: непрерывный хаос, удары без мотивации, сжигания церквей, религиозное обвинение, забрав власть от власти от Либералы, которые спонсировали движение и не попали в политику классов; Отказ признать в нормальности правым людям, которые добросовестно подчинялись режиму, хотя они логически не были зажжены республиканским экстремизмом. Либерал услышал эти пророчества с презрением к самоубийству. Сегодня было бы возмутительная ложь, чтобы сказать иначе. Много веков успеха в управлении народом (некоторые еще не погасли, как английские и американские демократии) дали личному лицу чрезмерную, иногда тщеславную уверенность в его превосходстве. Почти все статуи, которые на улицах Америки и Европы сеят людей, дань уважения великим людям, написали на своих плинтусах имя либерала. Каким бы ни было политическое будущее Испании, нет никаких сомнений в том, что на этой стадии своей истории это был реакционный, а не либерал, который понял это правильно.

С декабря 1936 года до осени 1942 года Маранон жил за границей, в де -факто изгнании. Вернувшись в Испанию снова, диктатура (как это было с другими интеллектуалами) использовал свою фигуру для улучшения своего внешнего изображения. В целом, франкоистское государство уважало его. [ Цитация необходима ] Мигель Артола в 1987 году заявил, что самый большой политический вклад Мараньяна явно поднял флаг свободы в то время, когда никто или только немногие не могли сделать это, понимая либерализм как противоположный определенной политической позиции. В этом смысле он заявил бы:

"Being liberal is, precisely, these two things: first, being open to understanding with those who think differently, and second, never admitting that the end justifies the means, but the other way around, the means justify the end. [...] Therefore, liberalism is a behaviour, and so, it is much more than politics".

— Prologue of his book Liberal Essays, 1946

His experience as a kind of insider served his knowledge about the Spanish state. After the student riots at the University of Madrid in 1956, he led, along with Menéndez Pidal, protests denouncing the dire political situation under Francoist rule, asking for the return of those exiled.

His early contribution to Medicine was focused on endocrinology, in fact him being one of its forefathers. During his first year of graduate school (1909) he published seven works in the Clinical Magazine of Madrid, of which only one was related to endocrinology, about the autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome. In 1910, he published five works, two of them related to endocrinology, about the Addison disease. In following years, his attraction to endocrinology only grew larger. In 1930 he published Endocrinology (printed in Madrid by Espasa-Calpe) and thirty more works in scientific journals on that speciality, of which half were works as the only author, which is remarkable taking into account the political-historical context in which Marañón was directly or indirectly involved. He wrote the first treatise of internal medicine in Spain, along with Doctor Hernando, and his book Manual of Etiologic Diagnostic (1946) was one of the most widespread medicine books in the world, because of its new focus on the study of diseases and its copious and unprecedented[citation needed] clinical contributions.

Beyond his intense dedication to medicine, he wrote about other topics, such as history, art, travels, cooking, clothing, hairstyle, or shoes. In his works he analysed, creating the unique and unprecedented genre of "biological essays", the great human passions through historical characters, and their psychic and physiopathologic features: shyness in his book Amiel, resentment in Tiberio, power in The Count-Duke of Olivares, intrigue and treason in politics in Antonio Pérez (one of the makers of the Spanish "black legend"), the "donjuanism" in Don Juan, etc.[citation needed] He was inducted and collaborated in five of the eight Spanish Real Academies.

The blueprint of Marañón is, in the opinion of Ramón Menéndez Pidal, "indelible", on both the science domain and the relationships he built with his peers.[citation needed] Pedro Laín Entralgo recognised as far as five different personalities in this great doctor from Madrid: the doctor Marañón; the writer Marañón; the historian Marañón, that greatly contributed to his "universality"; the moralist Marañón; and the Spanish Marañón. What makes his work even more singular is the "human" perspective that summarizes the multiplicity of domains that he is involved in, partaking in the scientific, ethical, moral, religious, cultural, and historic.

He was a doctor for the Royal House, and for plenty of well-known people from the social life in Spain, but above it all he was a "beneficence doctor" (or of attention to the poorest people) at the Hospital Provincial de Madrid, nowadays called Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, where in 1911 was appointed at his own request in the unit of infectious diseases. Along with this hospital, the biggest in Madrid, his name stands today on several streets and educational institutions all over Spain.

Foundation

[edit]The Gregorio Marañón Foundation was established on 11 November 1988, with the aim of "perpetuate the thinking and work of Doctor Marañón, spread the high magistrature of Medicine he worked in and promote research in the fields of Medicine and Bioethics". Furthermore, "it is a cornerstone of the Foundation the localization and recuperation of all the biographic and bibliographic documents to constitute a Documentary Fund available to all the learners who want to analyse and go deeper into the signification and validity of the thinking and work of Gregorio Marañón". A Marañón Week is annually held since 1990. The Marañón Week of 1999 was devoted to the topic of emotion, in 2000, held in Oviedo, was devoted to Benito Jerónimo Feijoo, in 2001, to the figure of don Juan, in 2002, held in the University Hospital Complex of Albacete, to the "Medical Work of Marañón", in 2006, held in Valencia, to "Luis Vives: Spanish humanist in Europe" and in 2009, to the "liberal tradition". On 9 July 2010 the José Ortega y Gasset Foundation and the Gregorio Marañón Foundation fused, creating a sole organization: the José Ortega y Gasset-Gregorio Marañón Foundation, also known as the Ortega-Marañón Foundation. However, the website of the new foundation, which still stands as http://www.ortegaygasset.edu, barely reveals any activity or interest related to Marañón.

Ateneo of Madrid

[edit]It could be taken into consideration that it was not the Foundation, but the Ateneo of Madrid, who celebrated the 50th anniversary of the death of Marañón, on 19 October 2010. In 1924 Marañón "had been promoted to president of the Ateneo by acclamation of his partners, that viewed him as his true president, but his presidency was de facto because the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera did not allow the electoral session. After the factious assembly , not recognised by the associates, Marañón was appointed as president of the Ateneo in March of 1930."

Legacy

[edit]Marañón’s sign is named after him, a clinical sign that increases the suspicion of a substernal goiter in patients.[1]

Books

[edit]- Tiberius: A Study in Resentment (1956) – translated from Tiberio: Historia de un resentimiento (1939)

References

[edit]- (in Spanish) biography at the Wayback Machine (archived 27 October 2009)

- ^ Schafranski, Marcelo Derbli; Cavalheiro, Patrícia Rechetello; Stival, Rebecca (2011). " PICTURES IN CLINICAL MEDICINE Marañón's Sign". Intern Med. 50 (15): 1619. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.50.5512. PMID 21804293.

External links

[edit]- 1887 births

- 1960 deaths

- Academics from Madrid

- Members of the Congress of Deputies of the Second Spanish Republic

- Spanish eugenicists

- Spanish male writers

- 20th-century Spanish philosophers

- 20th-century Spanish physicians

- Members of the Royal Spanish Academy

- Complutense University of Madrid alumni

- Exiles of the Spanish Civil War in Argentina

- Exiles of the Spanish Civil War in Uruguay

- Exiles of the Spanish Civil War in France

- 20th-century male writers

- Hispanic eugenics