Твердотельный накопитель

2,5-дюймовый Serial ATA. твердотельный накопитель | |

| Использование флэш-памяти | |

|---|---|

| Представлено: | СанДиск |

| Дата введения: | 1991 год |

| Емкость: | 20 МБ (форм-фактор 2,5 дюйма) |

| Оригинальная концепция | |

| К: | Корпорация технологий хранения данных |

| Conceived: | 1978 |

| Capacity: | 45 MB |

| As of 2024[update] | |

| Capacity: | Up to 200 TB[citation needed] |

( Твердотельный накопитель SSD ) — это твердотельное запоминающее устройство. Он обеспечивает постоянное хранение данных без использования движущихся частей. Его иногда называют полупроводниковым запоминающим устройством или твердотельным устройством . Его также называют твердотельным диском , поскольку он часто подключается к хост-системе так же, как жесткий диск (HDD). [1] [2]

SSD часто используется в качестве вторичного хранилища для обеспечения относительно быстрого, постоянного и прямого подключения к компьютеру . [3]

Атрибуты

[ редактировать ]SSD имеет богатый внутренний параллелизм для обработки данных. [4]

In comparison to HDDs and similar electromechanical magnetic storage which have moving parts, SSDs are typically silent, resistant to physical shock, and (in large part due to lower latency) have higher input/output rates.[5]

An SSD stores data in semiconductor cells, and an SSD's properties vary according to the number of bits stored in each cell which varies between 1 and 4. Single-bit cells ("Single Level Cells" or "SLC") are generally the most reliable, durable, fast, and expensive type, compared with 2- and 3-bit cells ("Multi-Level Cells/MLC" and "Triple-Level Cells/TLC"), and finally, quad-bit cells ("QLC") being used for consumer devices that do not require such extreme properties and are the cheapest per storage unit. In addition, 3D XPoint memory (sold by Intel under the Optane brand) stores data by changing the electrical resistance of cells instead of storing electrical charges in cells, and SSDs made from RAM can be used for high speed, when data persistence after power loss is not required, or may use battery power to retain data when its usual power source is unavailable.[6] Hybrid drives or solid-state hybrid drives (SSHDs), such as Intel's Hystor[7] and Apple's Fusion Drive, combine features of SSDs and HDDs in the same unit using both flash memory and spinning magnetic disks in order to improve the performance of frequently-accessed data.[8][9][10] Bcache achieves a similar effect purely in software, using combinations of dedicated regular SSDs and HDDs.

SSDs based on NAND flash slowly leak charge when not powered. Heavily used consumer drives (that have exceeded their endurance rating) may start losing data typically after one year (if stored at 30 °C) to two years (at 25 °C) in storage; for new drives it may take longer. Enterprise drives may see data loss as early as 3 months of no power stored at 40 °C.[11] Therefore, SSDs are not suitable for archival storage.

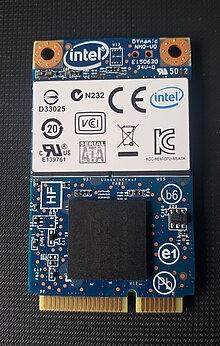

SSDs can use traditional HDD interfaces and form factors, or newer interfaces and form factors that exploit specific advantages of the flash memory in SSDs. Traditional interfaces (e.g. SATA and SAS) and standard HDD form factors allow such SSDs to be used as drop-in replacements for HDDs in computers and other devices. Newer form factors such as mSATA, M.2, U.2, NF1/M.3/NGSFF,[12][13] XFM Express (Crossover Flash Memory, form factor XT2)[14] and EDSFF (formerly known as Ruler SSD)[15][16] and higher speed interfaces such as NVM Express (NVMe) over PCI Express (PCIe) can further increase performance over HDD performance.[6] SSDs have a limited lifetime number of writes, and also slow down as they reach their full storage capacity.

Development and history

[edit]

Early SSDs using RAM and similar technology

[edit]An early—if not the first—semiconductor storage device compatible with a hard drive interface (e.g. an SSD as defined) was the 1978 StorageTek STC 4305, a plug-compatible replacement for the IBM 2305 fixed hard disk drive. It initially used charge-coupled devices (CCDs) for storage (later switched to DRAM), and consequently was reported to be seven times faster than the IBM product at about half the price ($400,000 for 45 MB capacity).[17] Before the StorageTek SSD there were many DRAM and core (e.g. DATARAM BULK Core, 1976)[18] products sold as alternatives to HDDs but they typically had memory interfaces and were not SSDs as defined.

In the late 1980s, Zitel offered a family of DRAM-based SSD products under the trade name "RAMDisk", for use on systems by UNIVAC and Perkin-Elmer, among others.

SSDs using Flash

[edit]| Parameter | Started with | Developed to | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity | 20 MB (Sandisk, 1991) | 100 TB (Enterprise Nimbus Data DC100, 2018) (As of 2024, up to 16 TB available for consumers)[19] | 5-million-to-one[20] (800,000-to-one[20]) |

| Sequential read speed | 49.3 MB/s (Samsung MCAQE32G5APP-0XA, 2007)[21] | 15 GB/s (Gigabyte demonstration, 2019) (As of June 2024[update] up to 14.5 GB/s available for consumers)[22] | 304.25-to-one[23] (294-to-one)[24] |

| Sequential write speed | 80 MB/s (Samsung enterprise SSD, 2008)[25][26] | 15.200 GB/s (Gigabyte demonstration, 2019) (As of June 2024[update] up to 12.7 GB/s available for consumers)[22] | 190-to-one[27] (159-to-one)[28] |

| IOPS | 79 (Samsung MCAQE32G5APP-0XA, 2007)[21] | 2,500,000 (Enterprise Micron X100, 2019) (As of June 2024[update] up to 1,550,000 read IOPS and 1,800,000 write IOPS available for consumers)[22] | 31,645.56-to-one[29] (Consumer: read IOPS: 19,620-to-one,[30] write IOPS: 22785-to-one)[31] |

| Access time (in milliseconds, ms) | 0.5 (Samsung MCAQE32G5APP-0XA, 2007)[21] | 0.045 read, 0.013 write (lowest values, WD Black SN850 1 TB, 2020)[32] | Read:11-to-one,[33] Write: 38-to-one[34] |

| Price | US$50,000 per gigabyte (Sandisk, 1991)[35] | US$0.05 per gigabyte (Silicon Power A60, July 2020)[36] | 10,000,000-to-one[37] |

The basis for flash-based SSDs, flash memory, was invented by Fujio Masuoka at Toshiba in 1980[38] and commercialized by Toshiba in 1987.[39][40] SanDisk Corporation (then SunDisk) founders Eli Harari and Sanjay Mehrotra, along with Robert D. Norman, saw the potential of flash memory as an alternative to existing hard drives, and filed a patent for a flash-based SSD in 1989.[41] The first commercial flash-based SSD was shipped by SanDisk in 1991.[38] It was a 20 MB SSD in a PCMCIA configuration, and sold OEM for around $1,000 and was used by IBM in a ThinkPad laptop.[42] In 1998, SanDisk introduced SSDs in 2.5-inch and 3.5-inch form factors with PATA interfaces.[43]

In 1995, STEC, Inc. entered the flash memory business for consumer electronic devices.[44]

In 1995, M-Systems introduced flash-based solid-state drives[45] as HDD replacements for the military and aerospace industries, as well as for other mission-critical applications. These applications require an SSD to withstand extreme shock, vibration, and temperature ranges.[46]

In 1999, BiTMICRO made a number of introductions and announcements about flash-based SSDs, including an 18 GB[47] 3.5-inch SSD.[48] In 2007, Fusion-io announced a PCIe-based Solid state drive with 100,000 input/output operations per second (IOPS) of performance in a single card, with capacities up to 320 GB.[49]

At Cebit 2009, OCZ Technology demonstrated a 1 TB[50] flash SSD using a PCI Express ×8 interface. It achieved a maximum write speed of 0.654 gigabytes per second (GB/s) and maximum read speed of 0.712 GB/s.[51] In December 2009, Micron Technology announced an SSD using a 6 gigabits per second (Gbit/s) SATA interface.[52]

In 2016, Seagate demonstrated 10 GB/s sequential read and write speeds from a 16-lane PCIe 3.0 SSD, and a 60 TB SSD in a 3.5-inch form factor. Samsung also launched to market a 15.36 TB SSD with a price tag of US$10,000 using a SAS interface, using a 2.5-inch form factor but with the thickness of 3.5-inch drives. This was the first time a commercially available SSD had more capacity than the largest currently available HDD.[53][54][55][56][57]

In 2018, both Samsung and Toshiba launched 30.72 TB SSDs using the same 2.5-inch form factor but with 3.5-inch drive thickness using a SAS interface. Nimbus Data announced and reportedly shipped 100 TB drives using a SATA interface, a capacity HDDs are not expected to reach until 2025. Samsung introduced an M.2 NVMe SSD with read speeds of 3.5 GB/s and write speeds of 3.3 GB/s.[58][59][60][61][62][63][64] A new version of the 100 TB SSD was launched in 2020 at a price of US$40,000, with the 50 TB version costing US$12,500.[65][66]

In 2019, Gigabyte Technology demonstrated an 8 TB 16-lane PCIe 4.0 SSD with 15.0 GB/s sequential read and 15.2 GB/s sequential write speeds at Computex 2019. It included a fan, as new, high-speed SSDs run at high temperatures. [67] Also in 2019, NVMe M.2 SSDs using the PCIe 4.0 interface were launched. These SSDs have read speeds of up to 5.0 GB/s and write speeds of up to 4.4 GB/s. Due to their high-speed operation, these SSDs use large heatsinks and, without sufficient cooling airflow, will typically thermally throttle down after roughly 15 minutes of continuous operation at full speed.[68] Samsung also introduced SSDs capable of 8 GB/s sequential read and write speeds and 1.5 million IOPS, capable of moving data from damaged chips to undamaged chips, to allow the SSD to continue working normally, albeit at a lower capacity.[69][70][71]

in 2021, NVMe 2.0 was announced, with Zoned Namespaces (ZNS) which allows data to be mapped directly to its physical location in memory to directly access it on an SSD without a flash translation layer.[72]

In 2024, Samsung announced what it called the world's first SSD with a hybrid PCIe interface, the Samsung 990 EVO. The hybrid interface runs in either the x4 PCIe 4.0 or x2 PCIe 5.0 modes, a first for an M.2 SSD.[73]

Enterprise flash drives

[edit]Enterprise flash drives (EFDs) are designed for applications requiring high I/O performance (IOPS), reliability, energy efficiency and, more recently, consistent performance. In most cases, an EFD is an SSD with a higher set of specifications compared to SSDs that would typically be used in notebook computers. The term was first used by EMC in January 2008 to identify SSD manufacturers who would provide products meeting these higher standards.[74] There are no standards bodies who control the definition of EFDs, so any SSD manufacturer may claim to produce EFDs when in fact the product may not meet any particular requirements.[75]

An example is the Intel DC S3700 series of drives introduced in the fourth quarter of 2012, which focuses on achieving consistent performance, an area that had not received much attention but which Intel claimed was important for the enterprise market; In particular, Intel claims that, at a steady state, the S3700 drives would not vary their IOPS by more than 10–15%, and that 99.9% of all 4 KB random I/Os are serviced in less than 500 μs.[76]

Another example is the Toshiba PX02SS enterprise SSD series announced in 2016, optimized for use in server and storage platforms requiring high endurance from write-intensive applications such as write caching, I/O acceleration, and online transaction processing (OLTP). The PX02SS series uses 12 Gbit/s SAS interface, featuring MLC NAND flash memory and achieving random write speeds of up to 42,000 IOPS, random read speeds of up to 130,000 IOPS, and endurance rating of 30 drive writes per day (DWPD).[77]

Drives using other persistent memory technologies

[edit]In 2017, the first products with 3D XPoint memory were released under Intel's Optane brand; 3D Xpoint is entirely different from NAND flash and stores data using different principles. SSDs based on 3D XPoint have higher IOPS (up to 2.5 million) but lower sequential read/write speeds than their NAND-flash counterparts.[78][79]

Architecture and function

[edit]The key components of an SSD are the controller and the memory to store the data. The primary memory component in an SSD was traditionally DRAM volatile memory, but since 2009, it is more commonly NAND flash non-volatile memory.[80][6]

Controller

[edit]Every SSD includes a controller that incorporates the electronics that bridge the NAND memory components to the host computer. The controller is an embedded processor that executes firmware-level code and is one of the most important factors of SSD performance.[81] Some of the functions performed by the controller include:[82][83]

- Bad block mapping

- Read and write caching

- Encryption

- Crypto-shredding

- Error detection and correction via error-correcting code (ECC) such as BCH code[84]

- Garbage collection

- Read scrubbing and read disturb management

- Wear leveling

The performance of an SSD can scale with the number of parallel NAND flash chips used in the device. A single NAND chip may be relatively slow due to its narrow asynchronous I/O interface (typical for SLC NAND, 8/16 bit asynchronous I/O interface), and additional high latency of basic I/O operations (typical for SLC NAND, ~25 μs to fetch a 4 KiB page from the array to the I/O buffer on a read, ~250 μs to commit a 4 KiB page from the IO buffer to the array on a write, ~2 ms to erase a 256 KiB block). When multiple NAND chips operate in parallel inside an SSD, the bandwidth and endurance scales, and the high latencies can be decreased, as long as enough outstanding operations are pending and the load is evenly distributed between devices.[85]

Micron and Intel initially made faster SSDs by implementing data striping (similar to RAID 0) and interleaving in their architecture. This enabled the creation of SSDs with 250 MB/s effective read/write speeds with the SATA 3 Gbit/s interface in 2009.[86] Two years later, SandForce continued to leverage this parallel flash connectivity, releasing consumer-grade SATA 6 Gbit/s SSD controllers which supported 500 MB/s read/write speeds.[87] SandForce controllers compress the data before sending it to the flash memory. This process may result in less writing and higher logical throughput, depending on the compressibility of the data.[88]

Wear leveling

[edit]If a particular block is programmed and erased repeatedly without writing to any other blocks, that block will wear out before all the other blocks—thereby prematurely ending the life of the SSD. For this reason, SSD controllers use a technique called wear leveling to distribute writes as evenly as possible across all the flash blocks in the SSD. In a perfect scenario, this would enable every block to be written to its maximum life so they all fail at the same time.

The process to evenly distribute writes requires data previously written and not changing (cold data) to be moved, so that data that is changing more frequently (hot data) can be written into those blocks.[89][90] Relocating data increases write amplification and adds to the wear of flash memory so a balance must be struck between these performance considerations and wear leveling effectiveness.

Memory

[edit]Flash memory

[edit]| Comparison characteristics | MLC : SLC | NAND : NOR |

|---|---|---|

| Persistence ratio | 1 : 10 | 1 : 10 |

| Sequential write ratio | 1 : 3 | 1 : 4 |

| Sequential read ratio | 1 : 1 | 1 : 5 |

| Price ratio | 1 : 1.3 | 1 : 0.7 |

Most SSD manufacturers use non-volatile NAND flash memory in the construction of their SSDs because of the lower cost compared with DRAM and the ability to retain the data without a constant power supply, ensuring data persistence through sudden power outages.[92] Flash memory SSDs were initially slower than DRAM solutions, and some early designs were even slower than HDDs after continued use. This problem was resolved by controllers that came out in 2009 and later.[93]

Flash-based SSDs store data in metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) integrated circuit chips which contain non-volatile floating-gate memory cells.[94] Flash memory-based solutions are typically packaged in standard disk drive form factors (1.8-, 2.5-, and 3.5-inch), but also in smaller more compact form factors, such as the M.2 form factor, made possible by the small size of flash memory.

Lower-priced drives usually use quad-level cell (QLC), triple-level cell (TLC) or more rarely, multi-level cell (MLC) flash memory, which is slower and less reliable than single-level cell (SLC) flash memory.[95][96] This can be mitigated or even reversed by the internal design structure of the SSD, such as interleaving, changes to writing algorithms,[96] and higher over-provisioning (more excess capacity) with which the wear-leveling algorithms can work.[97][98][99]

Solid-state drives that rely on V-NAND technology, in which layers of cells are stacked vertically, have been introduced.[100]

DRAM

[edit]SSDs based on volatile memory such as DRAM are characterized by very fast data access, generally less than 10 microseconds, and are used primarily to accelerate applications that would otherwise be held back by the latency of flash SSDs or traditional HDDs.

DRAM-based SSDs usually incorporate either an internal battery or an external AC/DC adapter and backup storage systems to ensure data persistence while no power is being supplied to the drive from external sources. If power is lost, the battery provides power while all information is copied from random access memory (RAM) to back-up storage. When the power is restored, the information is copied back to the RAM from the back-up storage, and the SSD resumes normal operation (similar to the hibernate function used in modern operating systems).[101][102]

SSDs of this type are usually fitted with DRAM modules of the same type used in regular PCs and servers, which can be swapped out and replaced by larger modules.[103]Such as i-RAM, HyperOs HyperDrive, DDRdrive X1, etc.Some manufacturers of DRAM SSDs solder the DRAM chips directly to the drive, and do not intend the chips to be swapped out—such as ZeusRAM, Aeon Drive, etc.[104]

A remote, indirect memory-access disk (RIndMA Disk) uses a secondary computer with a fast network or (direct) Infiniband connection to act like a RAM-based SSD, but the new, faster, flash-memory based, SSDs already available in 2009 are making this option not as cost effective.[105]

While the price of DRAM continues to fall, the price of Flash memory falls even faster.The "Flash becomes cheaper than DRAM" crossover point occurred approximately 2004.[106][107]

3D XPoint

[edit]In 2015, Intel and Micron announced 3D XPoint as a new non-volatile memory technology.[108] Intel released the first 3D XPoint-based drive (branded as Intel Optane SSD) in March 2017 starting with a data center product, Intel Optane SSD DC P4800X Series, and following with the client version, Intel Optane SSD 900P Series, in October 2017. Both products operate faster and with higher endurance than NAND-based SSDs, while the areal density is comparable at 128 gigabits per chip.[109][110][111][112] For the price per bit, 3D XPoint is more expensive than NAND, but cheaper than DRAM.[113][114]

Other

[edit]This section's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (December 2018) |

Some SSDs, called NVDIMM or Hyper DIMM devices, use both DRAM and flash memory. When the power goes down, the SSD copies all the data from its DRAM to flash; when the power comes back up, the SSD copies all the data from its flash to its DRAM.[115] In a somewhat similar way, some SSDs use form factors and buses actually designed for DIMM modules, while using only flash memory and making it appear as if it were DRAM. Such SSDs are usually known as ULLtraDIMM devices.[116]

Drives known as hybrid drives or solid-state hybrid drives (SSHDs) use a hybrid of spinning disks and flash memory.[117][118] Some SSDs use magnetoresistive random-access memory (MRAM) for storing data.[119][120]

Cache or buffer

[edit]A flash-based SSD may use a small amount of DRAM as a volatile cache, similar to the buffers in hard disk drives. A directory of block placement and wear leveling data is also kept in the cache while the drive is operating.[85] One SSD controller manufacturer, SandForce, does not use an external DRAM cache on their designs but still achieves high performance. Such an elimination of the external DRAM reduces the power consumption and enables further size reduction of SSDs.[121] On MLC SSDs, the SLC cache mechanism may be used. On NVMe SSDs, the Host Memory Buffer mechanism may be used.

Battery or supercapacitor

[edit]Another component in higher-performing SSDs is a capacitor or some form of battery, which are necessary to maintain data integrity so the data in the cache can be flushed to the drive when power is lost; some may even hold power long enough to maintain data in the cache until power is resumed.[121][122] In the case of MLC flash memory, a problem called lower page corruption can occur when MLC flash memory loses power while programming an upper page. The result is that data written previously and presumed safe can be corrupted if the memory is not supported by a supercapacitor in the event of a sudden power loss. This problem does not exist with SLC flash memory.[83]

Many consumer-class SSDs have built-in capacitors to save at least the FTL mapping table on unexpected power loss;[123] among the examples are the Crucial M500 and MX100 series,[124] the Intel 320 series,[125] and the more expensive Intel 710 and 730 series.[126] Enterprise-class SSDs, such as the Intel DC S3700 series,[127][128] usually have built-in batteries or supercapacitors.

Host interface

[edit]

The host interface is physically a connector with the signalling managed by the SSD's controller. It is most often one of the interfaces found in HDDs. They include:

- Serial attached SCSI (SAS-3, 12.0 Gbit/s) – generally found on servers[130]

- Serial ATA and mSATA variant (SATA 3.0, 6.0 Gbit/s)[131]

- PCI Express (PCIe 3.0 ×4, 31.5 Gbit/s)[132]

- M.2 (6.0 Gbit/s for SATA 3.0 logical device interface, 31.5 Gbit/s for PCIe 3.0 ×4)

- U.2 (PCIe 3.0 ×4)

- Fibre Channel (128 Gbit/s) – almost exclusively found on servers

- USB (10 Gbit/s)[133]

- Parallel ATA (UDMA, 1064 Mbit/s) – mostly replaced by SATA[134][135]

- (Parallel) SCSI ( 40 Mbit/s- 2560 Mbit/s) – generally found on servers, mostly replaced by SAS; last SCSI-based SSD was introduced in 2004[136]

SSDs support various logical device interfaces, such as Advanced Host Controller Interface (AHCI) and NVMe. Logical device interfaces define the command sets used by operating systems to communicate with SSDs and host bus adapters (HBAs).

Configurations

[edit]The size and shape of any device are largely driven by the size and shape of the components used to make that device. Traditional HDDs and optical drives are designed around the rotating platter(s) or optical disc along with the spindle motor inside. Since an SSD is made up of various interconnected integrated circuits (ICs) and an interface connector, its shape is no longer limited to the shape of rotating media drives. Some solid-state storage solutions come in a larger chassis that may even be a rack-mount form factor with numerous SSDs inside. They would all connect to a common bus inside the chassis and connect outside the box with a single connector.[6]

For general computer use, the 2.5-inch form factor (typically found in laptops and used for most SATA ssds) is the most popular. For desktop computers with 3.5-inch hard disk drive slots, a simple adapter plate can be used to make such a drive fit. Other types of form factors are more common in enterprise applications. An SSD can also be completely integrated in the other circuitry of the device, as in the Apple MacBook Air (starting with the fall 2010 model).[137] As of 2014[update], mSATA and M.2 form factors also gained popularity, primarily in laptops.

Standard HDD form factors

[edit]

The benefit of using a current HDD form factor would be to take advantage of the extensive infrastructure already in place to mount and connect the drives to the host system.[6][138] These traditional form factors are known by the size of the rotating media (i.e., 5.25-inch, 3.5-inch, 2.5-inch or 1.8-inch) and not the dimensions of the drive casing.

Standard card form factors

[edit]For applications where space is at a premium, like for ultrabooks or tablet computers, a few compact form factors were standardized for flash-based SSDs.

There is the mSATA form factor, which uses the PCI Express Mini Card physical layout. It remains electrically compatible with the PCI Express Mini Card interface specification while requiring an additional connection to the SATA host controller through the same connector.

M.2 form factor, formerly known as the Next Generation Form Factor (NGFF), is a natural transition from the mSATA and physical layout it used, to a more usable and more advanced form factor. While mSATA took advantage of an existing form factor and connector, M.2 has been designed to maximize usage of the card space, while minimizing the footprint. The M.2 standard allows both SATA and PCI Express SSDs to be fitted onto M.2 modules.[139]

Some high performance, high capacity drives uses standard PCI Express add-in card form factor to house additional memory chips, permit the use of higher power levels, and allow the use of a large heat sink. There are also adapter boards that converts other form factors, especially M.2 drives with PCIe interface, into regular add-in cards.

Disk-on-a-module form factors

[edit]

A disk-on-a-module (DOM) is a flash drive with either 40/44-pin Parallel ATA (PATA) or SATA interface, intended to be plugged directly into the motherboard and used as a computer hard disk drive (HDD). DOM devices emulate a traditional hard disk drive, resulting in no need for special drivers or other specific operating system support. DOMs are usually used in embedded systems, which are often deployed in harsh environments where mechanical HDDs would simply fail, or in thin clients because of small size, low power consumption, and silent operation.

As of 2016,[update] storage capacities range from 4 MB to 128 GB with different variations in physical layouts, including vertical or horizontal orientation.[citation needed]

Box form factors

[edit]Many of the DRAM-based solutions use a box that is often designed to fit in a rack-mount system. The number of DRAM components required to get sufficient capacity to store the data along with the backup power supplies requires a larger space than traditional HDD form factors.[140]

Bare-board form factors

[edit]- Viking Technology SATA Cube and AMP SATA Bridge multi-layer SSDs

- Viking Technology SATADIMM based SSD

- MO-297 SATA drive-on-a-module (DOM) SSD form factor

- A custom-connector SATA SSD

Form factors which were more common to memory modules are now being used by SSDs to take advantage of their flexibility in laying out the components. Some of these include PCIe, mini PCIe, mini-DIMM, MO-297, and many more.[141] The SATADIMM from Viking Technology uses an empty DDR3 DIMM slot on the motherboard to provide power to the SSD with a separate SATA connector to provide the data connection back to the computer. The result is an easy-to-install SSD with a capacity equal to drives that typically take a full 2.5-inch drive bay.[142] At least one manufacturer, Innodisk, has produced a drive that sits directly on the SATA connector (SATADOM) on the motherboard without any need for a power cable.[143] Some SSDs are based on the PCIe form factor and connect both the data interface and power through the PCIe connector to the host. These drives can use either direct PCIe flash controllers[144] or a PCIe-to-SATA bridge device which then connects to SATA flash controllers.[145]

There are also SSDs that are in the form of PCIe cards, these are sometimes called HHHL (Half Height Half Length), or AIC (Add in Card) SSDs.[146][147][148]

Ball grid array form factors

[edit]In the early 2000s, a few companies introduced SSDs in Ball Grid Array (BGA) form factors, such as M-Systems' (now SanDisk) DiskOnChip[149] and Silicon Storage Technology's NANDrive[150][151] (now produced by Greenliant Systems), and Memoright's M1000[152] for use in embedded systems. The main benefits of BGA SSDs are their low power consumption, small chip package size to fit into compact subsystems, and that they can be soldered directly onto a system motherboard to reduce adverse effects from vibration and shock.[153]

Such embedded drives often adhere to the eMMC and eUFS standards.

Comparison with other technologies

[edit]Hard disk drives

[edit]

Making a comparison between SSDs and ordinary (spinning) HDDs is difficult. Traditional HDD benchmarks tend to focus on the performance characteristics that are poor with HDDs, such as rotational latency and seek time. As SSDs do not need to spin or seek to locate data, they may prove vastly superior to HDDs in such tests. However, SSDs have challenges with mixed reads and writes, and their performance may degrade over time. SSD testing must start from the (in use) full drive, as the new and empty (fresh, out-of-the-box) drive may have much better write performance than it would show after only weeks of use.[154]

Most of the advantages of solid-state drives over traditional hard drives are due to their ability to access data completely electronically instead of electromechanically, resulting in superior transfer speeds and mechanical ruggedness.[155] On the other hand, hard disk drives offer significantly higher capacity for their price.[5][156]

Some field failure rates indicate that SSDs are significantly more reliable than HDDs[157][158] but others do not. However, SSDs are uniquely sensitive to sudden power interruption, resulting in aborted writes or even cases of the complete loss of the drive.[159] The reliability of both HDDs and SSDs varies greatly among models.[160]

As with HDDs, there is a tradeoff between cost and performance of different SSDs. Single-level cell (SLC) SSDs, while significantly more expensive than multi-level (MLC) SSDs, offer a significant speed advantage. At the same time, DRAM-based solid-state storage is currently considered the fastest and most costly, with average response times of 10 microseconds instead of the average 100 microseconds of other SSDs. Enterprise flash devices (EFDs) are designed to handle the demands of tier-1 application with performance and response times similar to less-expensive SSDs.[161]

In traditional HDDs, a rewritten file will generally occupy the same location on the disk surface as the original file, whereas in SSDs the new copy will often be written to different NAND cells for the purpose of wear leveling. The wear-leveling algorithms are complex and difficult to test exhaustively; as a result, one major cause of data loss in SSDs is firmware bugs.[162][163]

The following table shows a detailed overview of the advantages and disadvantages of both technologies. Comparisons reflect typical characteristics, and may not hold for a specific device.

| Attribute or characteristic | Solid-state drive | Hard disk drive |

|---|---|---|

| Price per capacity | SSDs generally are more expensive than HDDs and expected to remain so into the 2020s.[needs update][164] SSD price as of first quarter 2018[update] is around 30 cents (US) per gigabyte based on 4 TB models.[165] Prices have generally declined annually and as of 2018[update] are expected to continue to do so. | HDD price as of first quarter 2018[update] is around 2 to 3 cents (US) per gigabyte based on 1 TB models.[165] Prices have generally declined annually and as of 2018[update] are expected to continue to do so. |

| Storage capacity | In 2018, SSDs were available in sizes up to 100 TB,[166] but less costly, 120 to 512 GB models were more common. | In 2023, HDDs of up to 30 TB[167] were available. |

| Reliability – data retention | If left without power, worn out SSDs may start to lose data as soon as three months in storage, depending on temperature and type of SSD.[11] New drives may retain data for substantially longer depending upon usage prior to power off.[168] SSDs may not suited for archival use.[169] | If kept in a dry environment at low temperatures, HDDs can retain their data for a very long period of time even without power. However, the mechanical parts tend to become clotted over time and the drive fails to spin up after a few years in storage. |

| Reliability – longevity | SSDs have no moving parts to fail mechanically so in theory, should be more reliable than HDDs. However, in practice this is unclear.[170] Each block of a flash-based SSD can be erased (and therefore written) only a limited number of times before it fails. The controllers manage this limitation so that drives can last for many years under normal use.[171][172][173][174][175] SSDs based on DRAM do not have a limited number of writes. However the failure of a controller can make an SSD unusable. Reliability varies significantly across different SSD manufacturers and models with return rates reaching 40% for specific drives.[158] Many SSDs critically fail on power outages; a December 2013 survey of many SSDs found that only some of them are able to survive multiple power outages.[176][needs update?]A Facebook study found that sparse data layout across an SSD's physical address space (e.g., non-contiguously allocated data), dense data layout (e.g., contiguous data) and higher operating temperature (which correlates with the power used to transmit data) each lead to increased failure rates among SSDs.[177] However, SSDs have undergone many revisions that have made them more reliable and long lasting. As of 2018[update], SSDs in the market use power loss protection circuits, wear leveling techniques and thermal throttling to ensure longevity.[178][179] | HDDs have moving parts, and are subject to potential mechanical failures from the resulting wear and tear so in theory, should be less reliable than SSDs. However, in practice this is unclear.[170] The storage medium itself (magnetic platter) does not essentially degrade from reading and write operations. According to a study performed by Carnegie Mellon University for both consumer and enterprise-grade HDDs, their average failure rate is 6 years, and life expectancy is 9–11 years.[180] However the risk of a sudden, catastrophic data loss can be lower for HDDs.[181] When stored offline (unpowered on the shelf) in long term, the magnetic medium of HDD retains data significantly longer than flash memory used in SSDs. |

| Start-up time | Almost instantaneous; no mechanical components to prepare. May need a few milliseconds to come out of an automatic power-saving mode. | Drive spin-up may take several seconds. A system with many drives may need to stagger spin-up to limit peak power drawn, which is briefly high when an HDD is first started.[182] |

| Sequential-access performance | In consumer products the maximum transfer rate typically ranges from about 200 MB/s to 3500 MB/s,[183][184][185] depending on the drive. Enterprise SSDs can have multi-gigabyte per second throughput. | Once the head is positioned, when reading or writing a continuous track, a modern HDD can transfer data at about 200 MB/s. Data transfer rate depends also upon rotational speed, which can range from 3,600 to 15,000 rpm[186] and also upon the track (reading from the outer tracks is faster). Data transfer speed can be up to 480 MB/s (experimental).[187] |

| Random-access performance[188] | Random access time typically under 0.1 ms.[189][190] As data can be retrieved directly from various locations of the flash memory, access time is usually not a big performance bottleneck. Read performance does not change based on where data is stored. In applications, where hard disk drive seeks are the limiting factor, this results in faster boot and application launch times (see Amdahl's law).[191][182] SSD technology can deliver rather consistent read/write speed, but when many individual smaller blocks are accessed, performance is reduced.Flash memory must be erased before it can be rewritten to. This requires an excess number of write operations over and above that intended (a phenomenon known as write amplification), which negatively impacts performance.[192]SSDs typically exhibit a small, steady reduction in write performance over their lifetime, although the average write speed of some drives can improve with age.[193] | Read latency time is much higher than SSDs.[194] Random access time ranges from 2.9 (high end server drive) to 12 ms (laptop HDD) due to the need to move the heads and wait for the data to rotate under the magnetic head.[195] Read time is different for every different seek, since the location of the data and the location of the head are likely different. If data from different areas of the platter must be accessed, as with fragmented files, response times will be increased by the need to seek each fragment.[196] |

| Impact of file system fragmentation | There is limited benefit to reading data sequentially (beyond typical FS block sizes, say 4 KiB), making fragmentation negligible for SSDs. Defragmentation would cause wear by making additional writes of the NAND flash cells, which have a limited cycle life.[197][198] However, even with SSDs there is a practical limit on how much fragmentation certain file systems can sustain; once that limit is reached, subsequent file allocations fail.[199] Consequently, defragmentation may still be necessary, although to a lesser degree.[199] | Some file systems, like NTFS, become fragmented over time if frequently written; periodic defragmentation is required to maintain optimum performance.[200] This is usually not an issue in modern file systems like ext4, as they implement techniques such as allocate-on-flush to reduce file fragmentation as long as sufficient disk space is left free.[201][202] |

| Acoustic noise[203] | SSDs have no moving parts and therefore are silent, although, on some SSDs, high pitch noise from the high voltage generator (for erasing blocks) may occur. | HDDs have moving parts (heads, actuator, and spindle motor) and make characteristic sounds of whirring and clicking; noise levels vary depending on the RPM, but can be significant (while often much lower than the sound from the cooling fans). Laptop hard drives are relatively quiet. |

| Temperature control[204] | A Facebook study found that at operating temperatures above 40 °C (104 °F), the failure rate among SSDs increases with temperature. However, this was not the case with newer drives that employ thermal throttling, albeit at a potential cost to performance.[177] In practice, SSDs usually do not require special cooling and can tolerate higher temperatures than HDDs. Some SSDs, including high-end enterprise models installed as add-on cards or 2.5-inch bay devices, and high-end desktop NVMe models, may ship with heat sinks to dissipate generated heat, requiring certain volumes of airflow to operate.[205] | Ambient temperatures above 35 °C (95 °F) can shorten the life of a hard disk, and reliability will be compromised at drive temperatures above 55 °C (131 °F). Fan cooling may be required if temperatures would otherwise exceed these values.[206] In practice, modern HDDs may be used with no special arrangements for cooling. |

| Lowest operating temperature[207] | SSDs can operate at −55 °C (−67 °F). | Most modern HDDs can operate at 0 °C (32 °F). |

| Highest altitude when operating[208] | SSDs have no issues on this.[209] | HDDs can operate safely at an altitude of at most 3,000 meters (10,000 ft). HDDs will fail to operate at altitudes above 12,000 meters (40,000 ft).[210] With the introduction of helium-filled[211][212] (sealed) HDDs, this is expected to be less of an issue. |

| Moving from a cold environment to a warmer environment | SSDs have no issues with this. Due to the thermal throttling mechanism SSDs are kept secure and prevented from the temperature imbalance. | A certain amount of acclimation time may be needed when moving some HDDs from a cold environment to a warmer environment before operating them; depending upon humidity, condensation could occur on heads and/or disks and operating it immediately will result in damage to such components.[213] Modern helium HDDs are sealed and do not have such a problem. |

| Breather hole | SSDs do not require a breather hole. | Most modern HDDs require a breather hole in order to function properly.[210] Helium-filled devices are sealed and do not have a hole. |

| Susceptibility to environmental factors[191][214][215] | No moving parts, very resistant to shock, vibration, movement, and contamination. | Heads flying above rapidly rotating platters are susceptible to shock, vibration, movement, and contamination which could damage the medium. |

| Installation and mounting | Not sensitive to orientation, vibration, or shock. Usually no exposed circuitry. Circuitry may be exposed in a card form device and it must not be short-circuited by conductive materials. | Circuitry may be exposed, and it must not be short-circuited by conductive materials (such as the metal chassis of a computer). Should be mounted to protect against vibration and shock. Some HDDs should not be installed in a tilted position.[216] |

| Susceptibility to magnetic fields | Low impact on flash memory, but an electromagnetic pulse will damage any electrical system, especially integrated circuits. | In general, magnets or magnetic surges may result in data corruption or mechanical damage to the drive internals. Drive's metal case provides a low level of shielding to the magnetic platters.[217][218][219] |

| Weight and size[214] | SSDs, essentially semiconductor memory devices mounted on a circuit board, are small and lightweight. They often follow the same form factors as HDDs (2.5-inch or 1.8-inch) or are bare PCBs (M.2 and mSATA). The enclosures on most mainstream models, if any, are made mostly of plastic or lightweight metal. High performance models often have heatsinks attached to the device, or have bulky cases that serves as its heatsink, increasing its weight. | HDDs are generally heavier than SSDs, as the enclosures are made mostly of metal, and they contain heavy objects such as motors and large magnets. 3.5-inch drives typically weigh around 700 grams (1.5 lb). |

| Secure writing limitations | NAND flash memory cannot be overwritten, but has to be rewritten to previously erased blocks. If a software encryption program encrypts data already on the SSD, the overwritten data is still unsecured, unencrypted, and accessible (drive-based hardware encryption does not have this problem). Also data cannot be securely erased by overwriting the original file without special "Secure Erase" procedures built into the drive.[220] | HDDs can overwrite data directly on the drive in any particular sector. However, the drive's firmware may exchange damaged blocks with spare areas, so bits and pieces may still be present. Some manufacturers' HDDs fill the entire drive with zeroes, including relocated sectors, on ATA Secure Erase Enhanced Erase command.[221] |

| Read/write performance symmetry | Less expensive SSDs typically have write speeds significantly lower than their read speeds. Higher performing SSDs have similar read and write speeds. | HDDs generally have slightly longer (worse) seek times for writing than for reading.[222] |

| Free block availability and TRIM | SSD write performance is significantly impacted by the availability of free, programmable blocks. Previously written data blocks no longer in use can be reclaimed by TRIM; however, even with TRIM, fewer free blocks cause slower performance.[85][223][224] | HDDs are not affected by free blocks and may not benefit from TRIM. |

| Power consumption | High performance flash-based SSDs generally require half to a third of the power of HDDs. High-performance DRAM SSDs generally require as much power as HDDs, and must be connected to power even when the rest of the system is shut down.[225][226] Emerging technologies like DevSlp can minimize power requirements of idle drives. | The lowest-power HDDs (1.8-inch size) can use as little as 0.35 watts when idle.[227] 2.5-inch drives typically use 2 to 5 watts. The highest-performance 3.5-inch drives can use up to about 20 watts. |

| Maximum areal storage density (Terabits per square inch) | 2.8[228] | 1.2[228] |

Memory cards

[edit]

While both memory cards and most SSDs use flash memory, they serve very different markets and purposes. Each has a number of different attributes which are optimized and adjusted to best meet the needs of particular users. Some of these characteristics include power consumption, performance, size, and reliability.[229]

SSDs were originally designed for use in a computer system. The first units were intended to replace or augment hard disk drives, so the operating system recognized them as a hard drive. Originally, solid state drives were even shaped and mounted in the computer like hard drives. Later SSDs became smaller and more compact, eventually developing their own unique form factors such as the M.2 form factor. The SSD was designed to be installed permanently inside a computer.[229]

In contrast, memory cards (such as Secure Digital (SD), CompactFlash (CF), and many others) were originally designed for digital cameras and later found their way into cell phones, gaming devices, GPS units, etc. Most memory cards are physically smaller than SSDs, and designed to be inserted and removed repeatedly.[229]

SSD failure

[edit]SSDs have very different failure modes from traditional magnetic hard drives. Because solid-state drives contain no moving parts, they are generally not subject to mechanical failures. Instead, other kinds of failure are possible (for example, incomplete or failed writes due to sudden power failure can be more of a problem than with HDDs, and if a chip fails then all the data on it is lost, a scenario not applicable to magnetic drives). On the whole, however, studies have shown that SSDs are generally highly reliable, and often continue working far beyond the expected lifetime as stated by their manufacturer.[230]

The endurance of an SSD should be provided on its datasheet in one of two forms:

- either n DW/D (n drive writes per day)

- or m TBW (max terabytes written), short TBW.[231]

So for example a Samsung 970 EVO NVMe M.2 SSD (2018) with 1 TB has an endurance of 600 TBW.[232]

SSD reliability and failure modes

[edit]An early investigation by Techreport.com that ran from 2013 to 2015 involved a number of flash-based SSDs being tested to destruction to identify how and at what point they failed. The website found that all of the drives "surpassed their official endurance specifications by writing hundreds of terabytes without issue"—volumes of that order being in excess of typical consumer needs.[233] The first SSD to fail was TLC-based, with the drive succeeding in writing over 800 TB. Three SSDs in the test wrote three times that amount (almost 2.5 PB) before they too failed.[233] The test demonstrated the remarkable reliability of even consumer-market SSDs.

A 2016 field study based on data collected over six years in Google's data centres and spanning "millions" of drive days found that the proportion of flash-based SSDs requiring replacement in their first four years of use ranged from 4% to 10% depending on the model. The authors concluded that SSDs fail at a significantly lower rate than hard disk drives.[230] (In contrast, a 2016 evaluation of 71,940 HDDs found failure rates comparable to those of Google's SSDs: the HDDs had on average an annualized failure rate of 1.95%.)[234] The study also showed, on the down-side, that SSDs experience significantly higher rates of uncorrectable errors (which cause data loss) than do HDDs. It also led to some unexpected results and implications:

- In the real world, MLC-based designs – believed less reliable than SLC designs – are often as reliable as SLC. (The findings state that "SLC [is] not generally more reliable than MLC".) But generally it is said, that the write endurance is the following:

- SLC NAND: 100,000 erases per block

- MLC NAND: 5,000 to 10,000 erases per block for medium-capacity applications, and 1,000 to 3,000 for high-capacity applications

- TLC NAND: 1,000 erases per block

- Device age, measured by days in use, is the main factor in SSD reliability and not amount of data read or written, which are measured by terabytes written or drive writes per day. This suggests that other aging mechanisms, such as "silicon aging", are at play. The correlation is significant (around 0.2–0.4).

- Raw bit error rates (RBER) grow slowly with wear-out—and not exponentially as is often assumed. RBER is not a good predictor of other errors or SSD failure.

- The uncorrectable bit error rate (UBER) is widely used but is not a good predictor of failure either. However SSD UBER rates are higher than those for HDDs, so although they do not predict failure, they can lead to data loss due to unreadable blocks being more common on SSDs than HDDs. The conclusion states that although more reliable overall, the rate of uncorrectable errors able to impact a user is larger.

- "Bad blocks in new SSDs are common, and drives with a large number of bad blocks are much more likely to lose hundreds of other blocks, most likely due to Flash die or chip failure. 30–80% of SSDs develop at least one bad block and 2–7% develop at least one bad chip in the first four years of deployment."

- There is no sharp increase in errors after the expected lifetime is reached.

- Most SSDs develop no more than a few bad blocks, perhaps 2–4. SSDs that develop many bad blocks often go on to develop far more (perhaps hundreds), and may be prone to failure. However most drives (99%+) are shipped with bad blocks from manufacture. The finding overall was that bad blocks are common and 30–80% of drives will develop at least one in use, but even a few bad blocks (2–4) is a predictor of up to hundreds of bad blocks at a later time. The bad block count at manufacture correlates with later development of further bad blocks. The report conclusion added that SSDs tended to either have "less than a handful" of bad blocks or "a large number", and suggested that this might be a basis for predicting eventual failure.

- Around 2–7% of SSDs will develop bad chips in their first four years of use. Over two thirds of these chips will have breached their manufacturers' tolerances and specifications, which typically guarantee that no more than 2% of blocks on a chip will fail within its expected write lifetime.

- 96% of those SSDs that need repair (warranty servicing), need repair only once in their life. Days between repair vary from "a couple of thousand days" to "nearly 15,000 days" depending on the model.

Data recovery and secure deletion

[edit]Solid-state drives have set new challenges for data recovery companies, as the method of storing data is non-linear and much more complex than that of hard disk drives. The strategy by which the drive operates internally can vary largely between manufacturers, and the TRIM command zeroes the whole range of a deleted file. Wear leveling also means that the physical address of the data and the address exposed to the operating system are different.

As for secure deletion of data, ATA Secure Erase command could be used. A program such as hdparm can be used for this purpose.

Reliability metrics

[edit]The JEDEC Solid State Technology Association (JEDEC) has published standards for reliability metrics:[235]

- Unrecoverable Bit Error Ratio (UBER)

- Terabytes Written (TBW) – the number of terabytes that can be written to a drive within its warranty service

- Drive Writes Per Day (DWPD) – the number of times the total capacity of the drive may be written to per day within its warranty service

Applications

[edit]As of 2009, the cost of HDD storage was so much less that SSD was generally only used for applications where storage speed was mission critical. At that time, researchers predicted that cost would fall and adoption would increase. [6] More recently, due to the falling price of flash memory, SSD is more cost-effective.

In the distributed computing environment, SSDs can be used as a distributed cache layer that temporarily absorbs the large volume of user requests to the slower HDD based backend storage system. This layer provides much higher bandwidth and lower latency than the storage system, and can be managed in a number of forms, such as distributed key-value database and distributed file system. On supercomputers, this layer is typically referred to as burst buffer. With this fast layer, users often experience shorter system response time.

Flash-based solid-state drives can be used to create network appliances from general-purpose personal computer hardware. A write protected flash drive containing the operating system and application software can substitute for larger, less reliable disk drives or CD-ROMs. Appliances built this way can provide an inexpensive alternative to expensive router and firewall hardware.[citation needed]

SSDs based on an SD card with a live SD operating system are easily write-locked[broken anchor]. Combined with a cloud computing environment or other writable medium, to maintain persistence, an OS booted from a write-locked SD card is robust, rugged, reliable, and impervious to permanent corruption. If the running OS degrades, simply turning the machine off and then on returns it back to its initial uncorrupted state and thus is particularly solid. The SD card installed OS does not require removal of corrupted components since it was write-locked though any written media may need to be restored.

Hard-drive cache

[edit]In 2011, Intel introduced a caching mechanism for their Z68 chipset (and mobile derivatives) called Smart Response Technology, which allows a SATA SSD to be used as a cache (configurable as write-through or write-back) for a conventional, magnetic hard disk drive.[236] A similar technology is available on HighPoint's RocketHybrid PCIe card.[237]

Solid-state hybrid drives (SSHDs) are based on the same principle, but integrate some amount of flash memory on board of a conventional drive instead of using a separate SSD. The flash layer in these drives can be accessed independently from the magnetic storage by the host using ATA-8 commands, allowing the operating system to manage it. For example, Microsoft's ReadyDrive technology explicitly stores portions of the hibernation file in the cache of these drives when the system hibernates, making the subsequent resume faster.[238]

Dual-drive hybrid systems are combining the usage of separate SSD and HDD devices installed in the same computer, with overall performance optimization managed by the computer user, or by the computer's operating system software. Examples of this type of system are bcache and dm-cache on Linux,[239] and Apple's Fusion Drive.

File-system support for SSDs

[edit]Typically the same file systems used on hard disk drives can also be used on solid state drives. It is usually expected for the file system to support the TRIM command which helps the SSD to recycle discarded data (support for TRIM arrived some years after SSDs themselves but is now nearly universal). This means that the file system does not need to manage wear leveling or other flash memory characteristics, as they are handled internally by the SSD. Some log-structured file systems (e.g. F2FS, JFFS2) help to reduce write amplification on SSDs, especially in situations where only very small amounts of data are changed, such as when updating file-system metadata.

While not a native feature of file systems, operating systems should also aim to align partitions correctly, which avoids excessive read-modify-write cycles. A typical practice for personal computers is to have each partition aligned to start at a 1 MiB (= 1,048,576 bytes) mark, which covers all common SSD page and block size scenarios, as it is divisible by all commonly used sizes – 1 MiB, 512 KiB, 128 KiB, 4 KiB, and 512 B. Modern operating system installation software and disk tools handle this automatically.

Linux

[edit]Initial support for the TRIM command has been added to version 2.6.28 of the Linux kernel mainline.

The ext4, Btrfs, XFS, JFS, and F2FS file systems include support for the discard (TRIM or UNMAP) function.

Kernel support for the TRIM operation was introduced in version 2.6.33 of the Linux kernel mainline, released on 24 February 2010.[240] To make use of it, a file system must be mounted using the discard parameter. Linux swap partitions are by default performing discard operations when the underlying drive supports TRIM, with the possibility to turn them off, or to select between one-time or continuous discard operations.[241][242][243] Support for queued TRIM, which is a SATA 3.1 feature that results in TRIM commands not disrupting the command queues, was introduced in Linux kernel 3.12, released on November 2, 2013.[244]

An alternative to the kernel-level TRIM operation is to use a user-space utility called fstrim that goes through all of the unused blocks in a filesystem and dispatches TRIM commands for those areas. fstrim utility is usually run by cron as a scheduled task. As of November 2013[update], it is used by the Ubuntu Linux distribution, in which it is enabled only for Intel and Samsung solid-state drives for reliability reasons; vendor check can be disabled by editing file /etc/cron.weekly/fstrim using instructions contained within the file itself.[245]

Since 2010, standard Linux drive utilities have taken care of appropriate partition alignment by default.[246]

Linux performance considerations

[edit]

During installation, Linux distributions usually do not configure the installed system to use TRIM and thus the /etc/fstab file requires manual modifications.[247] This is because of the notion that the current Linux TRIM command implementation might not be optimal.[248] It has been proven to cause a performance degradation instead of a performance increase under certain circumstances.[249][250] As of January 2014,[update] Linux sends an individual TRIM command to each sector, instead of a vectorized list defining a TRIM range as recommended by the TRIM specification.[251]

For performance reasons, it is recommended to switch the I/O scheduler from the default CFQ (Completely Fair Queuing) to NOOP or Deadline. CFQ was designed for traditional magnetic media and seek optimization, thus many of those I/O scheduling efforts are wasted when used with SSDs. As part of their designs, SSDs offer much bigger levels of parallelism for I/O operations, so it is preferable to leave scheduling decisions to their internal logic – especially for high-end SSDs.[252][253]

A scalable block layer for high-performance SSD storage, known as blk-multiqueue or blk-mq and developed primarily by Fusion-io engineers, was merged into the Linux kernel mainline in kernel version 3.13, released on 19 January 2014. This leverages the performance offered by SSDs and NVMe, by allowing much higher I/O submission rates. With this new design of the Linux kernel block layer, internal queues are split into two levels (per-CPU and hardware-submission queues), thus removing bottlenecks and allowing much higher levels of I/O parallelization. As of version 4.0 of the Linux kernel, released on 12 April 2015, VirtIO block driver, the SCSI layer (which is used by Serial ATA drivers), device mapper framework, loop device driver, unsorted block images (UBI) driver (which implements erase block management layer for flash memory devices) and RBD driver (which exports Ceph RADOS objects as block devices) have been modified to actually use this new interface; other drivers will be ported in the following releases.[254][255][256][257][258]

macOS

[edit]Versions since Mac OS X 10.6.8 (Snow Leopard) support TRIM but only when used with an Apple-purchased SSD.[259] TRIM is not automatically enabled for third-party drives, although it can be enabled by using third-party utilities such as Trim Enabler. The status of TRIM can be checked in the System Information application or in the system_profiler command-line tool.

Versions since OS X 10.10.4 (Yosemite) include sudo trimforce enable as a Terminal command that enables TRIM on non-Apple SSDs.[260] There is also a technique to enable TRIM in versions earlier than Mac OS X 10.6.8, although it remains uncertain whether TRIM is actually utilized properly in those cases.[261]

Microsoft Windows

[edit]Prior to version 7, Microsoft Windows did not take any specific measures to support solid state drives. From Windows 7, the standard NTFS file system provides support for the TRIM command. (Other file systems on Windows 7 do not support TRIM.)[262]

By default, Windows 7 and newer versions execute TRIM commands automatically if the device is detected to be a solid-state drive. However, because TRIM irreversibly resets all freed space, it may be desirable to disable support where enabling data recovery is preferred over wear leveling.[263] To change the behavior, in the Registry key HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\FileSystem the value DisableDeleteNotification can be set to 1. This prevents the mass storage driver issuing the TRIM command.

Windows implements TRIM command for more than just file-delete operations. The TRIM operation is fully integrated with partition- and volume-level commands such as format and delete, with file-system commands relating to truncate and compression, and with the System Restore (also known as Volume Snapshot) feature.[264]

Windows Vista

[edit]Windows Vista generally expects hard disk drives rather than SSDs.[265][266] Windows Vista includes ReadyBoost to exploit characteristics of USB-connected flash devices, but for SSDs it only improves the default partition alignment to prevent read-modify-write operations that reduce the speed of SSDs. Most SSDs are typically split into 4 KiB sectors, while earlier systems may be based on 512 byte sectors with their default partition setups unaligned to the 4 KiB boundaries.[267]

Defragmentation

[edit]Defragmentation should be disabled on solid-state drives because the location of the file components on an SSD does not significantly impact its performance, but moving the files to make them contiguous using the Windows Defrag routine will cause unnecessary write wear on the limited number of write cycles on the SSD. The SuperFetch feature will not materially improve performance and causes additional overhead in the system and SSD.[268] Windows Vista does not send the TRIM command to solid-state drives, but some third-party utilities such as SSD Doctor will periodically scan the drive and TRIM the appropriate entries.[269]

Windows 7

[edit]Windows 7 and later versions have native support for SSDs.[264][270] The operating system detects the presence of an SSD and optimizes operation accordingly. For SSD devices, Windows 7 disables ReadyBoost and automatic defragmentation.[271] Despite the initial statement by Steven Sinofsky before the release of Windows 7,[264] however, defragmentation is not disabled, even though its behavior on SSDs differs.[199] One reason is the low performance of Volume Shadow Copy Service on fragmented SSDs.[199] The second reason is to avoid reaching the practical maximum number of file fragments that a volume can handle. If this maximum is reached, subsequent attempts to write to the drive will fail with an error message.[199]

Windows 7 also includes support for the TRIM command to reduce garbage collection for data that the operating system has already determined is no longer valid. Without support for TRIM, the SSD would be unaware of this data being invalid and would unnecessarily continue to rewrite it during garbage collection causing further wear on the SSD. It is beneficial to make some changes that prevent SSDs from being treated more like HDDs, for example cancelling defragmentation, not filling them to more than about 75% of capacity, not storing frequently written-to files such as log and temporary files on them if a hard drive is available, and enabling the TRIM process.[272][273]

Windows 8.1 and later

[edit]Windows 8.1 and later Windows systems also support automatic TRIM for PCI Express SSDs based on NVMe. For Windows 7, the KB2990941 update is required for this functionality and needs to be integrated into Windows Setup using DISM if Windows 7 has to be installed on the NVMe SSD. Windows 8/8.1 also support the SCSI unmap command for USB-attached SSDs or SATA-to-USB enclosures. SCSI Unmap is a full analog of the SATA TRIM command. It is also supported over USB Attached SCSI Protocol (UASP).

The graphical Windows Disk Defragmenter in Windows 8.1 also recognizes SSDs distinctly from hard disk drives in a separate Media Type column. While Windows 7 supported automatic TRIM for internal SATA SSDs, Windows 8.1 and Windows 10 support manual TRIM (via an "Optimize" function in Disk Defragmenter) as well as automatic TRIM for SATA, NVMe and USB-attached SSDs. Disk Defragmenter in Windows 10 and 11 may execute TRIM to optimize an SSD.[274]

ZFS

[edit]Solaris as of version 10 Update 6 (released in October 2008), and recent[when?] versions of OpenSolaris, Solaris Express Community Edition, Illumos, Linux with ZFS on Linux, and FreeBSD all can use SSDs as a performance booster for ZFS. A low-latency SSD can be used for the ZFS Intent Log (ZIL), where it is named the SLOG. This is used every time a synchronous write to the drive occurs. An SSD (not necessarily with a low-latency) may also be used for the level 2 Adaptive Replacement Cache (L2ARC), which is used to cache data for reading. When used either alone or in combination, large increases in performance are generally seen.[275]

FreeBSD

[edit]ZFS for FreeBSD introduced support for TRIM on September 23, 2012.[276] The code builds a map of regions of data that were freed; on every write the code consults the map and eventually removes ranges that were freed before, but are now overwritten. There is a low-priority thread that TRIMs ranges when the time comes.

Also the Unix File System (UFS) supports the TRIM command.[277]

Swap partitions

[edit]- According to Microsoft's former Windows division president Steven Sinofsky, "there are few files better than the pagefile to place on an SSD".[278] According to collected telemetry data, Microsoft had found the pagefile.sys to be an ideal match for SSD storage.[278] However, enable pagefile on SSD may increase the write amplification of SSD.

- Linux swap partitions are by default performing TRIM operations when the underlying block device supports TRIM, with the possibility to turn them off, or to select between one-time or continuous TRIM operations.[241][242][243]

- If an operating system does not support using TRIM on discrete swap partitions, it might be possible to use swap files inside an ordinary file system instead. For example, OS X does not support swap partitions; it only swaps to files within a file system, so it can use TRIM when, for example, swap files are deleted.[citation needed]

- DragonFly BSD allows SSD-configured swap to also be used as file-system cache.[279] This can be used to boost performance on both desktop and server workloads. The bcache, dm-cache, and Flashcache projects provide a similar concept for the Linux kernel.[280]

Standardization organizations

[edit]The following are noted standardization organizations and bodies that work to create standards for solid-state drives (and other computer storage devices). The table below also includes organizations which promote the use of solid-state drives. This is not necessarily an exhaustive list.

| Organization or committee | Subcommittee of: | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| INCITS | — | Coordinates technical standards activity between ANSI in the US and joint ISO/IEC committees worldwide |

| T10 | INCITS | SCSI |

| T11 | INCITS | FC |

| T13 | INCITS | ATA |

| JEDEC | — | Develops open standards and publications for the microelectronics industry |

| JC-64.8 | JEDEC | Focuses on solid-state drive standards and publications |

| NVMHCI | — | Предоставляет стандартные программные и аппаратные интерфейсы программирования для подсистем энергонезависимой памяти. |

| САТА-ИО | — | Предоставляет отрасли рекомендации и поддержку по внедрению спецификации SATA. |

| Комитет СФФ | — | Работает над стандартами отрасли хранения данных, требующими внимания, когда они не рассматриваются другими комитетами по стандартизации. |

| СНИА | — | Разрабатывает и продвигает стандарты, технологии и образовательные услуги в области управления информацией. |

| УОНИ | СНИА | Способствует росту и успеху твердотельных накопителей |

Коммерциализация

[ редактировать ]Доступность

[ редактировать ]Технология твердотельных приводов продается на военных и нишевых промышленных рынках с середины 1990-х годов. [281]

Наряду с развивающимся корпоративным рынком твердотельные накопители стали появляться в ультрамобильных ПК и некоторых легких ноутбуках, что значительно увеличило цену ноутбука в зависимости от емкости, форм-фактора и скорости передачи данных. Для недорогих приложений USB-накопитель можно приобрести примерно за 10–100 долларов США, в зависимости от емкости и скорости; в качестве альтернативы карта CompactFlash может быть соединена с преобразователем CF-IDE или CF-SATA по аналогичной цене. Любой из этих способов требует решения проблем с выносливостью цикла записи, либо воздерживаясь от хранения часто записываемых файлов на диске, либо используя флэш-файловую систему . Стандартные карты CompactFlash обычно имеют скорость записи от 7 до 15 МБ/с, в то время как более дорогие карты высокого класса требуют скорости до 60 МБ/с.

Первым доступным ПК на базе твердотельного накопителя с флэш-памятью стал Sony Vaio UX90, предварительный заказ которого был объявлен 27 июня 2006 года, а поставки в Японию начались 3 июля 2006 года с жестким диском с флэш-памятью емкостью 16 ГБ. [282] В конце сентября 2006 года Sony увеличила объем SSD в Vaio UX90 до 32 ГБ. [283]

Одним из первых массовых выпусков SSD стал ноутбук XO , созданный в рамках проекта One Laptop Per Child . Массовое производство этих компьютеров, созданных для детей в развивающихся странах, началось в декабре 2007 года. В этих машинах используется флэш-память SLC NAND емкостью 1024 МБ в качестве основного хранилища, которое считается более подходящим для более суровых, чем обычные, условий, в которых они будут использоваться. Dell начала поставки ультрапортативных ноутбуков с твердотельными накопителями SanDisk 26 апреля 2007 года. [284] компания Asus выпустила Eee PC с 2, 4 или 8 гигабайтами флэш-памяти. нетбук 16 октября 2007 года [285] В 2008 году два производителя выпустили ультратонкие ноутбуки с вариантами SSD вместо необычного 1,8-дюймового жесткого диска : это был MacBook Air , выпущенный Apple 31 января, с дополнительным твердотельным накопителем емкостью 64 ГБ (стоимость этого варианта в Apple Store была на 999 долларов дороже). по сравнению с жестким диском емкостью 80 ГБ и скоростью 4200 об/мин ), [286] И Lenovo ThinkPad X300 с аналогичным SSD на 64 гигабайта, анонсированный в феврале 2008 года. [287] и был обновлен до варианта SSD емкостью 128 ГБ 26 августа 2008 г. с выпуском модели ThinkPad X301 (обновление, которое добавило примерно 200 долларов США). [288]

бюджетного класса с твердотельными нетбуки В 2008 году появились накопителями. В 2009 году SSD-накопители начали появляться в ноутбуках. [284] [286]

14 января 2008 г. корпорация EMC (EMC) стала первым поставщиком корпоративных систем хранения данных, включившим твердотельные накопители на базе флэш-памяти в свой портфель продуктов, объявив, что выбрала твердотельные накопители Zeus-IOPS компании STEC, Inc. для своих систем Symmetrix DMX. [289] В 2008 году компания Sun выпустила унифицированные системы хранения данных Sun Storage 7000 (под кодовым названием Amber Road), в которых используются как твердотельные накопители, так и обычные жесткие диски, чтобы воспользоваться преимуществами скорости, предлагаемой твердотельными накопителями, а также экономичностью и емкостью, обеспечиваемыми обычными жесткими дисками. [290]

В январе 2009 года Dell начала предлагать дополнительные твердотельные накопители емкостью 256 ГБ для некоторых моделей ноутбуков. [291] [292] В мае 2009 года Toshiba выпустила ноутбук с твердотельным накопителем емкостью 512 ГБ. [293] [294]

С октября 2010 года в линейке Apple MacBook Air в стандартной комплектации используется твердотельный накопитель. [295] В декабре 2010 года твердотельный накопитель OCZ RevoDrive X2 PCIe был доступен емкостью от 100 до 960 ГБ, обеспечивая скорость последовательной передачи более 740 МБ/с и скорость случайной записи небольших файлов до 120 000 операций ввода-вывода в секунду. [296] В ноябре 2010 года Fusion-io выпустила свой самый производительный SSD-накопитель под названием ioDrive Octal, использующий интерфейс PCI-Express x16 Gen 2.0, объем памяти 5,12 ТБ, скорость чтения 6,0 ГБ/с, скорость записи 4,4 ГБ/с и низкую задержку. 30 микросекунд. Он имеет 1,19 млн операций ввода-вывода в секунду при чтении 512 байт и 1,18 млн операций ввода-вывода в секунду при записи 512 байт. [297]

В 2011 году стали доступны компьютеры на базе спецификаций Intel Ultrabook . Эти спецификации диктуют, что в ультрабуках используется SSD. Это устройства потребительского уровня (в отличие от многих предыдущих предложений флэш-памяти, предназначенных для корпоративных пользователей) и представляют собой первые широко доступные потребительские компьютеры, использующие твердотельные накопители, помимо MacBook Air. [298] На выставке CES 2012 компания OCZ Technology продемонстрировала твердотельные накопители R4 CloudServ PCIe, способные достигать скорости передачи данных 6,5 ГБ/с и 1,4 миллиона операций ввода-вывода в секунду. [299] Также был анонсирован Z-Drive R5, доступный емкостью до 12 ТБ, способный достигать скорости передачи данных 7,2 ГБ/с и 2,52 миллиона операций ввода-вывода в секунду с использованием PCI Express x16 Gen 3.0. [300]

В декабре 2013 года компания Samsung представила и выпустила первый в отрасли твердотельный накопитель mSATA емкостью 1 ТБ . [301] В августе 2015 года Samsung анонсировала твердотельный накопитель емкостью 16 ТБ, который на тот момент был самым емким устройством хранения данных в мире любого типа. [302]

Хотя ряд компаний предлагают SSD-устройства по состоянию на 2018 год. [update] только пять компаний, предлагающих их, на самом деле производят флэш-устройства NAND. [303] это элемент хранения данных в твердотельных накопителях.

Качество и производительность

[ редактировать ]В общем, производительность любого конкретного устройства может существенно различаться в разных условиях эксплуатации. Например, количество параллельных потоков, обращающихся к устройству хранения, размер блока ввода-вывода и количество оставшегося свободного пространства — все это может существенно изменить производительность (т. е. скорость передачи данных) устройства. [304]

Технология SSD быстро развивается. Большинство измерений производительности, используемых на дисках с вращающимися носителями, также используются и на твердотельных накопителях. Производительность твердотельных накопителей на базе флэш-памяти сложно оценить из-за широкого диапазона возможных условий. В тесте, проведенном в 2010 году компанией Xssist с использованием IOmeter , 4 КБ случайным образом, 70% чтения/30% записи, глубина очереди 4, IOPS, обеспечиваемый Intel X25-E 64 ГБ G1, начинался с 10 000 IOPS и резко падал через 8 минут. до 4000 IOPS и продолжал постепенно снижаться в течение следующих 42 минут. Число операций ввода-вывода в секунду варьируется от 3000 до 4000 примерно в течение 50 минут и до конца 8-часового тестового запуска. [305]

Разработчики флэш-накопителей корпоративного уровня пытаются продлить срок службы за счет увеличения избыточного выделения ресурсов и использования выравнивания износа . [306]

Продажи

[ редактировать ]Этот раздел необходимо обновить . ( апрель 2018 г. ) |

В 2009 году поставки твердотельных накопителей составили 11 миллионов единиц. [307] 17,3 миллиона единиц в 2011 году [308] на общую сумму 5 миллиардов долларов США, [309] 39 миллионов единиц в 2012 году и, как ожидается, вырастет до 83 миллионов единиц в 2013 году. [310] до 201,4 млн единиц в 2016 году [308] и до 227 миллионов единиц в 2017 году. [311]

Доходы рынка твердотельных накопителей (включая недорогие решения для ПК) во всем мире составили 585 миллионов долларов США в 2008 году, увеличившись более чем на 100% с 259 миллионов долларов США в 2007 году. [312]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Плата твердотельного накопителя

- Список производителей твердотельных накопителей

- Список производителей контроллеров флэш-памяти

- Жесткий диск

- Рейд

- Модуль флэш-ядра

- RAM-накопитель

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Уиттакер, Зак. «Цены на твердотельные диски падают, но они все еще дороже, чем жесткие диски» . Между строк . ЗДНет. Архивировано из оригинала 2 декабря 2012 года . Проверено 14 декабря 2012 г.

- ^ «Энергосбережение твердотельных накопителей приводит к значительному снижению совокупной стоимости владения» (PDF) . СТЭК . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 4 июля 2010 г. Проверено 25 октября 2010 г.

- ^ Фэн Чен, Дэвид А. Куфати и Сяодун Чжан (2009). «Понимание внутренних характеристик и системных последствий твердотельных накопителей на основе флэш-памяти». . Обзор оценки производительности ACM Sigmetrics. стр. 181–192. дои : 10.1145/2492101.1555371 .

- ^ Фэн Чен, Рубао Ли и Сяодун Чжан (2011). «Основная роль использования внутреннего параллелизма твердотельных накопителей на основе флэш-памяти в высокоскоростной обработке данных» . 2011 17-й Международный симпозиум IEEE по высокопроизводительной компьютерной архитектуре. стр. 266–277.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Касавайхала, Вамси (май 2011 г.). «Исследование цены и производительности твердотельных накопителей и жестких дисков, технический документ Dell» (PDF) . Технический маркетинг Dell PowerVault. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 12 мая 2012 года . Проверено 15 июня 2012 г.