конечность головоногих моллюсков

Все головоногие имеют гибкие конечности, отходящие от головы и окружающие клюв . Эти придатки, выполняющие функцию мышечных гидростатов , назывались по-разному: руками, ногами или щупальцами. [А]

Описание

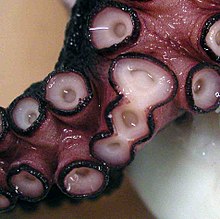

[ редактировать ]В научной литературе руку головоногих часто рассматривают отдельно от щупальца , хотя эти термины иногда используются как синонимы, причем последний часто выступает в качестве обобщающего термина для конечностей головоногих моллюсков. Обычно руки имеют присоски на большей части длины, в отличие от щупалец, у которых присоски есть только на концах. [4] За некоторыми исключениями, у осьминогов восемь рук и нет щупалец, а у кальмаров и каракатиц восемь рук (или две «ноги» и шесть «рук») и два щупальца. [5] Конечности наутилусов , которых насчитывается около 90 и у которых вообще отсутствуют присоски, называются усики. [5] [6] [7]

Считается, что щупальца Decapodiformes произошли от четвертой пары рук предкового колеоида , но термин «рукава IV» используется для обозначения последующей, вентральной пары рук у современных животных (которая в эволюционном отношении является пятой парой рук). [4]

У самцов большинства головоногих развивается специализированный рукав для доставки спермы — гектокотиль .

Анатомически конечности головоногих функционируют, используя перекрестную штриховку спиральных коллагеновых волокон, противостоящих внутреннему мышечному гидростатическому давлению . [8] [ нужен лучший источник ]

лохи

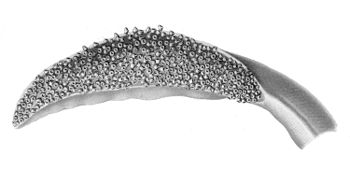

[ редактировать ]Конечности головоногих несут многочисленные присоски вдоль брюшной поверхности, как у осьминогов , кальмаров и рук каракатиц , а также скоплениями на концах щупалец (если они есть), как у кальмаров и каракатиц. [9] Каждая присоска обычно круглая, чашеобразная и состоит из двух отдельных частей: внешней неглубокой полости, называемой воронкой , и центральной полой полости, называемой вертлужной впадиной . Обе эти структуры представляют собой толстые мышцы и покрыты хитиновой кутикулой, образующей защитную поверхность. [10] Suckers are used for grasping substratum, catching prey and for locomotion. When a sucker attaches itself to an object, the infundibulum mainly provides adhesion while the central acetabulum is free. Sequential muscle contraction of the infundibulum and acetabulum causes attachment and detachment.[11][12]

Abnormalities

[edit]Many octopus arm anomalies have been recorded,[13][14] including a 6-armed octopus (nicknamed Henry the Hexapus), a 7-armed octopus,[15] a 10-armed Octopus briareus,[16] one with a forked arm tip,[17] octopuses with double or bilateral hectocotylization,[18][19] and specimens with up to 96 arm branches.[20][21][22]

Branched arms and other limb abnormalities have also been recorded in cuttlefish,[23] squid,[24] and bobtail squid.[25]

Variability

[edit]Cephalopod limbs and the suckers they bear are shaped in many distinctive ways, and vary considerably between species. Some examples are shown below.

Arms

[edit]For hectocotylized arms see hectocotylus variability.

| Shape of arm | Species | Family |

|---|---|---|

| Todarodes pacificus | Ommastrephidae |

Tentacular clubs

[edit]Suckers

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ A study has determined that the octopus has two legs and six arms, often commonly referred to as "tentacles". [1] Another study found that there is a functional difference in the way the appendages are used for task division. "These findings give evidence for limb-specialization in an animal whose 8 arms were believed to be equipotential."[2] The two rear appendages are generally used to walk on the sea floor, while the other six are used to forage for food.[3]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Thomas, David (12 August 2008). "Octopuses have two legs and six arms". The Telegraph. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

To most of us it has always seemed obvious that an octopus has eight arms. Octopuses have two legs and six arms Claire Little, a marine expert from the Weymouth Sea Life Centre in Dorset, said: 'We've found that octopuses effectively have six arms and two legs.'

- ^ Ruth A., Byrne; Kuba, Michael J.; Meisel, Daniela V.; Griebel, Ulrike; Mather, Jennifer A. (August 2006). "Does Octopus vulgaris have preferred arms?". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 120 (3): 198–204. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.120.3.198. PMID 16893257.

- ^ Lloyd, John; Mitchinson, John (2010). QI: The Second Book of General Ignorance. London: Faber and Faber. p. 3. ISBN 978-0571273751.

As result, marine biologists tend to refer to them as animals with two legs and six arms.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Young, R.E., M. Vecchione & K.M. Mangold 1999. Cephalopoda Glossary. Tree of Life web project.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Norman, M. 2000. Cephalopods: A World Guide. ConchBooks, Hackenheim. p. 15. "There is some confusion around the terms arms versus tentacles. The numerous limbs of nautiluses are called tentacles. The ring of eight limbs around the mouth in cuttlefish, squids and octopuses are called arms. Cuttlefish and squid also have a pair of specialised limbs attached between the bases of the third and fourth arm pairs [...]. These are known as feeding tentacles and are used to shoot out and grab prey."

- ^ Fukuda, Y. 1987. Histology of the long digital tentacles. In: W.B. Saunders & N.H. Landman (eds.) Nautilus: The Biology and Paleobiology of a Living Fossil. Springer Netherlands. pp. 249–256. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3299-7_17

- ^ Kier, W.M. 1987. "The functional morphology of the tentacle musculature of Nautilus pompilius" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-17. Retrieved 2010-06-11. In: W.B. Saunders & N.H. Landman (eds.) Nautilus: The Biology and Paleobiology of a Living Fossil. Springer Netherlands. pp. 257–269. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3299-7_18

- ^ [1] Inside Nature's Giants, episode 5

- ^ von Byern J, Klepal W (2005). "Adhesive mechanisms in cephalopods: a review". Biofouling. 22 (5–6): 329–38. doi:10.1080/08927010600967840. PMID 17110356.

- ^ Walla G (2007). "A study of the Comparative Morphology of Cephalopod Armature". tonmo.com. Deep Intuition, LLC. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- ^ Kier WM, Smith AM (2002). "The structure and adhesive mechanism of octopus suckers". Integr Comp Biol. 42 (6): 1146–1153. doi:10.1093/icb/42.6.1146. PMID 21680399.

- ^ Octopuses & Relatives. "Learn about octopuses & relatives: locomotion". asnailsodyssey.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-22. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- ^ Kumph H.E. (1960). "Arm abnormality in octopus". Nature. 185 (4709): 334–335. Bibcode:1960Natur.185..334K. doi:10.1038/185334a0. S2CID 4226765.

- ^ Toll R.B., Binger L.C. (1991). "Arm anomalies: cases of supernumerary development and bilateral agenesis of arm pairs in Octopoda (Mollusca, Cephalopoda)". Zoomorphology. 110 (6): 313–316. doi:10.1007/BF01668021. S2CID 34858474.

- ^ Gleadall I.G. (1989). "An octopus with only seven arms: anatomical details". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 55 (4): 479–487. doi:10.1093/mollus/55.4.479.

- ^ Minor birth defect resulting in 10-armed juvenile, all arms fully present and functional.[permanent dead link] CephBase.

- ^ Minor birth defect showing bifurcated arm tip. Both tips were fully functional.[permanent dead link] CephBase.

- ^ Robson G.C. (1929). "On a case of bilateral hectocotylization in Octopus rugosus". Journal of Zoology. 99 (1): 95–97. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1929.tb07690.x.

- ^ Palacio, F.J. 1973. "On the double hectocotylization of octopods". Melbourne, Fla., etc., American Malacologists, inc., etc. 1973. The Nautilus 87: 99–102.

- ^ Окада Ю.К. (1965). «О японских осьминогах с разветвленными руками, с особым упором на их отловы в период с 1884 по 1964 год» . Труды Японской академии . 41 (7): 618–623. дои : 10.2183/pjab1945.41.618 .

- ^ Окада Ю.К. (1965). «Правила ветвления рук у японских осьминогов с разветвленными руками» . Труды Японской академии . 41 (7): 624–629. дои : 10.2183/pjab1945.41.624 .

- ^ Осьминоги-монстры с множеством дополнительных щупалец . Розовое щупальце , 18 июля 2008 года.

- ^ Окада Ю.К. (1937). «Появление разветвленных рук у десятиногих головоногих моллюсков Sepia esculenta Hoyle». Аннотированная зоология Японии . 17 : 93–94.

- ^ Брэдбери HE, Олдрич Ф.А. (1971). «Возникновение морфологических аномалий у эгопсидного кальмара Illex illecebrosus (Lesueur, 1821)». Канадский журнал зоологии . 49 (3): 377–379. дои : 10.1139/z71-055 . ПМИД 5103494 .

- ^ Восс Г.Л. (1957). «Наблюдения за аномальным ростом рук и щупалец у кальмаров рода Россия ». Ежеквартальный журнал Академии наук Флориды . 20 (2): 129–132.