Guardia Piemontese

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Occitan. (January 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions. |

Guardia Piemontese | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Guardia Piemontese | |

Location of Guardia Piemontese | |

| Coordinates: 39°28′N 16°0′E / 39.467°N 16.000°E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Calabria |

| Province | Cosenza (CS) |

| Frazioni | Marina, Terme Luigiane |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Vincenzo Rocchetti[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 21.46 km2 (8.29 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 515 m (1,690 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,917 |

| • Density | 89/km2 (230/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Guardiota(i) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 87020 |

| Dialing code | 0982 |

| Website | Official website |

Guardia Piemontese (Occitan: La Gàrdia) is a town and comune in the province of Cosenza and the region of Calabria in southern Italy.

Location and language

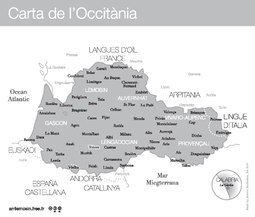

[edit]Guardia Piemontese is located about 55 km northwest of Cosenza on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea. Its neighbouring municipalities are Acquappesa, Cetraro, Fuscaldo and Mongrassano. Guardia is an Occitan linguistic and ethnic enclave.[5]

History

[edit]The date of Guardia's foundation is unknown, and the name of the place has changed several times in history. "Guardia" means watch or lookout, and this name is probably related to a lookout tower built in the 11th century. Such lookout towers (Italian: torri costiere) were built to warn against Arab pirates, then called Saracens, ravaging the coast. Guardia used to be called Guardia Fiscaldi, after the powerful local feudal lords Fiscaldo/Fuscaldo, originating from Fuscaldo. After the settlement of Waldensian refugees who spoke the Occitan language, the place gained the name of Guardia dei Valdi. After their suppression, the name became Guardia Lombarda, which was changed to Guardia Piemontese in 1863.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, Waldensians arrived in Calabria from the Kingdom of Arles and Dauphiné, which had part of his territories also in the most western valleys of Piedmont. By 1315, they had settled in Montalto Uffugo, later also in San Sosti dei Valdesi, Vacarizzo and San Vincenzo. The local feudal lords, the Spinelli, being lords of Fuscaldo, granted them refuge.[6] By 1375, they had also settled on the hill rising to 500 metres above sea level on which the upper town of Guardia now stands.[6] For a long period, the Waldensians pretended to live as Roman Catholics, attending the Holy Mass and having their children baptised in Catholic churches. However, privately they stuck to their beliefs and received travelling Waldensian preachers for few days in intervals of about two years.[6]

With the successes of the Reformation, many secret Waldensians decided not to hide their true religious beliefs any longer.[7] In 1532, they decided at their Synod of Chanforan (in Piedmont) to confess their beliefs openly. Thereupon, Calabrian Waldensians sent Marco Uscegli as an envoy to Geneva, with the request for preachers to be dispatched. In this way the preacher Gian Luigi Pascale came to Calabria, and he established Waldensian churches in Guardia Piemontese and San Sosti.[8] The Waldensians in their traditional areas in Piedmont did the same, and in 1560 the locally powerful Bishop of Mondovì, Cardinal Michele Ghislieri (later to become Pope Pius V), initiated a crusade against the Waldensians.[9]

The Calabrian Roman Catholic Abbot Giovan Antonio Anania informed Ghislieri that the Waldensians in Calabria had meanwhile also adopted preachers of their own,[8] so Ghislieri ordered the abbot to eradicate the Waldensian heresy, in coordination with his local Archbishop of Cosenza, Taddeo Gaddi.[8] First, Anania tried to coerce the Waldensians into converting by way of threats, but they refused. With a sense of foreboding, many Waldensians from neighbouring places fled to Guardia, which was fortified.[8] Guardia's lord Salvatore Spinelli (c. 1506–1565) tried to make the Waldensians relent and advised Pascale and Uscegli to flee, but in vain.

Spinelli, who did not wish to be accused of favouring heretics, finally resorted to a trick.[8] In June 1561, he requested entry to the town for himself and fifty of his men, claiming that they would come unarmed. Loyal to their lord, the men of Guardia let them in. In the night of 4 to 5 June, Spinelli and his henchmen took out their hidden weapons and took the town by force. In doing so, and by further pogroms in the following two weeks, Spinelli and his henchmen murdered about 2,000 Waldensians in Guardia Piemontese and other places.[8] This bloodshed is commemorated by the name of the town's main gate, the Porta del Sangue, or Gate of Blood, because it was said that the blood of the murdered flowed all the way down to it.[8] Next to the town gate there is now the Centro di Cultura Giovan Luigi Pascale which contains a permanent exhibition on the history of the Waldensians of Guardia.[8]

The survivors of the massacre had to convert to Roman Catholicism, and marriages between a man and a woman both of Waldensian descent were forbidden.[8] Spioncini, spyholes to be opened from the outside, were to be built into the town's front doors, in order to allow inquisitors to spy into the houses and check whether the compulsory converts really abstain from Waldensian traditions.[10] Some spioncini can still be found in frontdoors. The Waldensian church was demolished. On its site, today's Piazza Chiesa Valdese, a piece of rock from Piedmont was put in 1975, donated by Guardia's twin city Torre Pellice in memory of the descent of many Guardioti from the Piedmontese rocky Alps.[11] The names of 118 known victims of the 1561 massacre are listed in a plaque at the rock.

In memory of the eradication of the Waldensian heresy, Salvatore Spinelli donated the Dominican church Chiesa del SS. Rosario in Guardia.[10] In April 1565 he was created Marchese of Fuscaldo in honour of his deed.[12]

Twin towns

[edit] Torre Pellice, Italy

Torre Pellice, Italy

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ 2011 Election Official Results Archived 21 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Italian National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Data from Istat

- ^ All demographics and other statistics: Italian statistical institute Istat.

- ^ Cf. Hans Peter Kunert, "Quale grafia per l’occitano di Guardia Piemontese?", in: Quaderni del Dipartimento di Linguistica 10, Univ. della Calabria, Serie Linguistica 4, 1993, 27–36; Kunert, "L’occitan en Calàbria", in: Estudis Occitans 16, 1994, 3–14; Kunert, "L’occitan en Calabre", in: RLR XCVIII, 1994, 477–489.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ilona Witten, Kalabrien, 2nd, updated ed., Cologne: DuMont, 22001, p. 58. ISBN 3-7701-5288-3.

- ^ Ilona Witten, Kalabrien, 2nd, updated ed., Cologne: DuMont, 22001, pp. 58seq. ISBN 3-7701-5288-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Ilona Witten, Kalabrien, 2nd, updated ed., Cologne: DuMont, 22001, p. 59. ISBN 3-7701-5288-3.

- ^ Anacleto Verrecchia, Giordano Bruno: la falena dello spirito, (Rome: Editore Donzelli, 2002, ISBN 88-7989-676-8), p. 43

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ilona Witten, Kalabrien, 2nd, updated ed., Cologne: DuMont, 22001, p. 61. ISBN 3-7701-5288-3.

- ^ Ilona Witten, Kalabrien, 2nd, updated ed., Cologne: DuMont, 22001, pp. 60seq. ISBN 3-7701-5288-3.

- ^ Salvatore Spinelli 1° Marchese di Fuscaldo Archived 13 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on 8 April 2011.