Fitjar

Fitjar Municipality

Fitjar kommune | |

|---|---|

| Fitje herred (historic name) | |

View of the village of Fitjar | |

|

| |

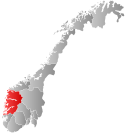

Vestland within Norway | |

Fitjar within Vestland | |

| Coordinates: 59°55′08″N 05°22′17″E / 59.91889°N 5.37139°E | |

| Country | Norway |

| County | Vestland |

| District | Sunnhordland |

| Established | 1 Jan 1863 |

| • Preceded by | Stord Municipality |

| Administrative centre | Fitjar |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2023) | Wenche Tislevoll (H) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 142.47 km2 (55.01 sq mi) |

| • Land | 134.50 km2 (51.93 sq mi) |

| • Water | 7.97 km2 (3.08 sq mi) 5.6% |

| • Rank | #317 in Norway |

| Population (2023) | |

| • Total | 3,181 |

| • Rank | #224 in Norway |

| • Density | 23.7/km2 (61/sq mi) |

| • Change (10 years) | |

| Demonym | Fitjabu[1] |

| Official language | |

| • Norwegian form | Nynorsk |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | NO-4615[3] |

| Website | Official website |

Fitjar (Norwegian pronunciation: [ˈfɪ̂tːjɑr] ) is a municipality in Vestland county, Norway. The municipality is located in the traditional district of Sunnhordland. Fitjar municipality includes the northern part of the island of Stord and the hundreds of surrounding islands, mostly to the northwest of the main island. The administrative centre of the municipality is the village of Fitjar.[4]

The 142-square-kilometre (55 sq mi) municipality is the 317th largest by area out of the 356 municipalities in Norway. Fitjar is the 224th most populous municipality in Norway with a population of 3,181. The municipality's population density is 23.7 inhabitants per square kilometre (61/sq mi) and its population has increased by 6.7% over the previous 10-year period.[5][6]

General information

[edit]

The parish of Fitje was established as a municipality on 1 January 1863 when it was separated from the large Stord Municipality. Initially, the population of Fitje was 2,313. On 1 January 1868, a small area in the municipality of Finnaas (population: 10) was transferred to Fitje. In 1900, the name was changed to Fitjar. The original municipality included all of the land surrounding the Selbjørnsfjorden.[7]

During the 1960s, there were many municipal mergers across Norway due to the work of the Schei Committee. On 1 January 1964, the area of Fitjar located north of the Selbjørnsfjorden on the islands of Huftarøy and Selbjørn (population: 696) was transferred to the neighboring Austevoll Municipality. On 1 January 1995, the islands of Aga, Agasystra, Gisøya, Vikøya, Selsøy, Risøya, and many smaller surrounding islands (population: 225) were transferred from Fitjar to the neighboring Bømlo Municipality. These islands had recently been connected to Bømlo by road bridges which precipitated the municipal transfer.[7]

Name

[edit]The municipality (originally the parish) is named after the old Fitjar farm (Old Norse: Fitjar) since the first Fitjar Church was built there. The name is the plural form of fit which means "meadow along the water" or "lush meadow". Before 1900, the name was written "Fitje".[8]

Coat of arms

[edit]The coat of arms was adopted during the late 1940s, but they have never been formally granted since they did not meet the formal government design requirements. In 2018, the municipal council of Fitjar formally approved the arms after a change to a national law. The blazon is "Azure, a Viking helmet Or within a orle argent". This means the arms have a blue field (background) and the charge is a Viking helmet with a thin border around the edge of the shield. The charge has a tincture of Or which means it is commonly colored yellow, but if it is made out of metal, then gold is used. The arms often have a mural crown depicted above the escutcheon. The helmet and the color are derived from the belief that King Haakon the Good wore a golden helmet at the Battle of Fitjar in 961, which was fought in this municipality. King Haakon died from his wounds. His death and reception in Valhalla are described in the skaldic poem Hákonarmál, composed by the Eyvindr skáldaspillir. The arms were designed by Magnus Hardeland. The municipal flag is orange with a depiction of coat of arms in the centre along with the name of the municipality below the arms.[9][10][11]

Churches

[edit]The Church of Norway has one parish (sokn) within the municipality of Fitjar. It is part of the Sunnhordland prosti (deanery) in the Diocese of Bjørgvin.

| Parish (sokn) | Church name | Location of the church | Year built |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fitjar | Fitjar Church | Fitjar | 1867 |

History

[edit]King Haakon I of Norway (Haakon the Good) maintained his residence at Fitjar. The Battle of Fitjar (Slaget ved Fitjar på Stord) took place in Fitjar on the island of Stord in the year 961 between the forces of King Haakon I and the sons of his half-brother, Eric Bloodaxe. Traditionally, important shipping routes have passed through the area, and the municipality contains several trading posts dating as far back as 1648. Fitjar was separated from Stord in 1863. There have been discussions about a possible reunion of the two municipalities, but no decision has been made.

Population

[edit]

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Note: The municipal borders were changed in 1964 and 1995, causing a significant change in the population. Source: Statistics Norway[5][12] and Norwegian Historical Data Centre[13] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Geography

[edit]The island municipality of Fitjar lies south of the Selbjørnsfjorden, west of the Langenuen strait, east of the island of Bømlo. The municipality includes over 350 islands, although most are uninhabited. The majority of the residents live on the island of Stord, the northern portion of which is in Fitjar. The southern portion of the island is part of the municipality of Stord. The island municipality of Austevoll lies to the north, across the fjord and the island municipality of Tysnes lies across the Langenuen strait to the east, and the island municipality of Bømlo lies to the west.[4]

Government

[edit]Fitjar Municipality is responsible for primary education (through 10th grade), outpatient health services, senior citizen services, welfare and other social services, zoning, economic development, and municipal roads and utilities. The municipality is governed by a municipal council of directly elected representatives. The mayor is indirectly elected by a vote of the municipal council.[14] The municipality is under the jurisdiction of the Haugaland og Sunnhordland District Court and the Gulating Court of Appeal.

Municipal council

[edit]The municipal council (Kommunestyre) of Fitjar is made up of 17 representatives that are elected to four year terms. The tables below show the current and historical composition of the council by political party.

| Party name (in Nynorsk) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeidarpartiet) | 2 | |

| Progress Party (Framstegspartiet) | 3 | |

| Conservative Party (Høgre) | 5 | |

| Industry and Business Party (Industri‑ og Næringspartiet) | 1 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristeleg Folkeparti) | 5 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 1 | |

| Total number of members: | 17 | |

Mayors

[edit]The mayors (Nynorsk: ordførar) of Fitjar:

- 1864–1865: Johannes Sørfonden

- 1866–1871: Østen Hageberg

- 1872–1875: Mikkel Sjursen Eide

- 1876–1895: Østen Hageberg (H)[34]

- 1896–1904: Anders Aarbø (H)[35]

- 1905–1913: Mikal Hageberg (H)[35]

- 1913–1913: Tharald Vestbøstad (H)[35]

- 1914–1919: Lars Rydland

- 1920–1925: Peder Rygg

- 1926–1928: Lars Rydland

- 1929–1951: Berje Aarbø (Bp)[36]

- 1952–1955: Harald Henriksen (V)[37]

- 1956–1967: Peder Nilsen Aga (V)[37]

- 1968–1971: Knut L. Rydland (H)

- 1972–1975: Ole Havn (KrF)

- 1976–1977: Knut L. Rydland (H)

- 1978–1979: Finn Havnerås (Ap)[38]

- 1980–1981: Ingebrigt Sørfonn (KrF)

- 1982–1983: Alf Gjøsæter (H)[39]

- 1984–1985: Torvald Ingebrigtsen (Ap)[40]

- 1986–1987: Ingebrigt Sørfonn (KrF)

- 1988–1991: Kjell Nesbø (Ap)

- 1992–1995: Johannes Koløen (H)

- 1995–1998: Per-Gunnar Bukkholm (KrF)

- 1998–1999: Odd Bondevik (Sp)[41]

- 1999–2007: Agnar Aarskog (Ap)

- 2007–2011: Harald Rydland (KrF)

- 2011–2019: Wenche Tislevoll (H)

- 2019–2023: Harald Rydland (KrF)

- 2023–present: Wenche Tislevoll (H)[42]

Attractions

[edit]

Fitjar Church was built in 1867 over the site of the old medieval stone church which had been demolished. Stone blocks taken from the old stone church were used as foundations for the present-day church as well as for the walling enclosing the churchyard. Opposite Fitjar Church is Haakon's Park (Håkonarparken), the location of a sculpture of Haakon the Good sculpted by Anne Grimdalen. The statue was erected in 1961 at the one thousand year commemoration of the Battle of Fitjar.[43]

Notable people

[edit]- Andreas Fleischer (1878–1957), a theologian, missionary to China, Lutheran Bishop, and priest in Fitjar Church from 1912-1917

- Otto Hageberg (1936–2014), a literary historian and academic

References

[edit]- ^ "Navn på steder og personer: Innbyggjarnamn" (in Norwegian). Språkrådet.

- ^ "Forskrift om målvedtak i kommunar og fylkeskommunar" (in Norwegian). Lovdata.no.

- ^ Bolstad, Erik; Thorsnæs, Geir, eds. (26 January 2023). "Kommunenummer". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Kunnskapsforlaget.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Store norske leksikon. "Fitjar" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Statistisk sentralbyrå. "Table: 06913: Population 1 January and population changes during the calendar year (M)" (in Norwegian).

- ^ Statistisk sentralbyrå. "09280: Area of land and fresh water (km²) (M)" (in Norwegian).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jukvam, Dag (1999). Historisk oversikt over endringer i kommune- og fylkesinndelingen (PDF) (in Norwegian). Statistisk sentralbyrå. ISBN 9788253746845.

- ^ Rygh, Oluf (1910). Norske gaardnavne: Søndre Bergenhus amt (in Norwegian) (11 ed.). Kristiania, Norge: W. C. Fabritius & sønners bogtrikkeri. p. 156.

- ^ "Civic heraldry of Norway - Norske Kommunevåpen". Heraldry of the World. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ "Fitjar kommune". Digitalarkivet (in Norwegian). Arkivverket. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ "Fitjar kommune, våpen". Digitalarkivet (in Norwegian). Arkivverket. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ Statistisk sentralbyrå. "Folketellingen 1960" (PDF) (in Norwegian).

- ^ Universitetet i Tromsø – Norges arktiske universitet. "Censuses in the Norwegian Historical Data Archive (NHDC)".

- ^ Hansen, Tore; Vabo, Signy Irene, eds. (20 September 2022). "kommunestyre". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalg 2023 - Vestland". Valgdirektoratet. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalg 2019 – Vestland". Valgdirektoratet. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Table: 04813: Members of the local councils, by party/electoral list at the Municipal Council election (M)" (in Norwegian). Statistics Norway.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalg 2011 – Hordaland". Valgdirektoratet. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalget 1995" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1996. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalget 1991" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1993. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalget 1987" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1988. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalget 1983" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1984. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalget 1979" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1979. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene 1975" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1977. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene 1972" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1973. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene 1967" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1967. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene 1963" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1964. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1959" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1960. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1955" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1957. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1951" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1952. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1947" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1948. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1945" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1947. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1937" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1938. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ Utheim, John (1892). Oversigt over Valgmands- og Storthingsvalgene 1891. Kristiania: Steenske bogtrykkeri. p. 35.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Utheim, John (1901). Oversigt over valgtingene og valgmandstingene 1900. Kristiania: Steenske bogtrykkeri. pp. 57–58.

- ^ Andersen, Thor M. (1931). Norges ordførere 1929–1931. Kristiania: A.M. Hanches Forlag. p. 159.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Norske kommunalpolitikere: Norges styresmenn. Vol. 2. Oslo: Bokdepotet forlag. 1956. pp. 323–325.

- ^ Rimmereid, Ingolv (14 November 2000). "Jubilant". Bergens Tidende. p. 24.

- ^ "Ordførar frå Høgre i Fitjar". Bergens Tidende. 16 December 1981. p. 58.

- ^ "T. Ingebrigtsen Fitjar-ordførar". Bergens Tidende. 17 November 1983. p. 10.

- ^ Olderkjær, Ove (2 April 1998). "Bondevik styrer Fitjar". Bergens Tidende. p. 7.

- ^ "Wenche Tislevoll blir ordfører i Fitjar". NRK (in Norwegian). 21 September 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ "Carwalk Fitjar". VisitNorway.com. Archived from the original on 17 September 2012.

External links

[edit]- Municipal fact sheet from Statistics Norway (in Norwegian)

Hordaland travel guide from Wikivoyage

Hordaland travel guide from Wikivoyage Media related to Fitjar at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fitjar at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of Fitjar at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Fitjar at Wiktionary