KREUTZ Sungrazer

Sungrazers Kreutz ( / ˈ k r ɔɪ t s / Кройтс ) - это семья солнцезащитных комет , характеризующихся орбитами, которые заставляют их очень близко к солнцу в перигелионе . В крайнем случае их орбит, афелион , Sungrazers Kreutz могут находиться в сто раз дальше от солнца, чем земля, в то время как их расстояние ближайшего подхода может быть менее чем в два раза больше радиуса солнца. Считается, что они являются фрагментами одной большой кометы , которая рассталась несколько веков назад и названа в честь немецкого астронома Генриха Кройца , который впервые продемонстрировал, что они были связаны. [ 1 ] Эти солнцезащитные сечения пробираются от далекой внешней солнечной системы к внутренней солнечной системе, до их перигеляционной точки возле солнца, а затем оставляют внутреннюю солнечную систему в их обратной поездке в их афелион.

Несколько членов семьи Кройц стали великими кометами , иногда видимыми возле солнца в дневном небе. Самым последним из них была Комета Икия -Секи в 1965 году, которая, возможно, была одной из самых ярких комет в последнем тысячелетии . Было высказано предположение, что еще один кластер ярких системных комет KREUTZ может начать прибывать во внутреннюю солнечную систему в ближайшие несколько десятилетий.

Более 4000 меньших членов семьи, некоторые из них всего в нескольких метрах поперечных, были обнаружены с момента запуска спутника Soho в 1995 году. Ни одна из этих небольших комет не пережила его перигелия. Большие солнцезащитные сечения, такие как великая комета 1843 года и C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy), пережили свой перигелия. Астрономы -любители добились успеха в обнаружении кометов Кройца в данных, доступных в режиме реального времени через Интернет.

Открытие и исторические наблюдения

[ редактировать ]

Первая комета, у которой, как было обнаружено, было очень близко к солнцу, была великая комета 1680 года . Было обнаружено, что эта комета проходила всего 200 000 километров (120 000 миль) (0,0013 а.е. ) над поверхностью солнца, эквивалентной около седьмого диаметра солнца, или примерно вдвое расстояние между землей и луной . [ 2 ]

В то время астрономы, в том числе Эдмонд Хэлли , предположили, что эта комета была возвращением яркой кометы, увиденной близко к солнцу в небе в 1106 году. [ 2 ] 163 года спустя появилась великая комета 1843 года и также прошла очень близко к Солнцу. Несмотря на орбитальные расчеты, показывающие, что в нем было период несколько веков, некоторые астрономы задавались вопросом, было ли это возвращением Кометы 1680 года. [ 2 ] Было обнаружено, что яркая комета, видимая в 1880 году, путешествует на почти идентичной орбите на орбите 1843 года, как и последующая великая комета 1882 года . Некоторые астрономы предположили, что, возможно, все они были одной кометой, орбитальный период которой был каким -то образом резко сокращен на каждом перигеелионном проходе, возможно, задержкой каким -то плотным материалом, окружающим Солнце. [ 2 ]

Альтернативным предположением было то, что все кометы были фрагментами более ранней солнечной кометы. [ 1 ] Эта идея была впервые предложена в 1880 году, и ее правдоподобие была достаточно продемонстрирована, когда великая комета 1882 года распалась на несколько фрагментов после его перигелия. [ 3 ] В 1888 году Генрих Кройц опубликовал статью, показывающую, что кометы 1843 года (C/1843 D1, Великая Мартовская комета), 1880 (C/1880 C1, великая южная комета) и 1882 (C/1882 R1, великая сентябрьская комета ), вероятно, были фрагменты гигантской кометы, которая разбила несколько орбит раньше. [ 1 ] Комета 1680 года оказалась не связанной с этой семьей комет. [ 4 ]

После того, как еще один Sungrazer был замечен в 1887 году (C/1887 B1, великая южная комета 1887 года ), следующая не появилась до 1945 года. [ 5 ] Два еще солнца появились в 1960 -х годах, Комета Перейра в 1963 году и Комета Икия -Секи , которая стала чрезвычайно яркой в 1965 году и разбилась на три части после его перигелия. [ 6 ] Это, вероятно, самый известный среди Sungrazers Kreutz. [ 7 ] Появление двух Sungrazers Kreutz в быстрой последовательности вдохновило на дальнейшее изучение динамики группы. [ 5 ] Первоначально название «Sungrazer» было применено исключительно к группе Kreutz. [ 4 ]

Физические черты

[ редактировать ]Большинство солнечных комет являются частью семьи Кройц. [ 8 ] Группа, как правило, имеет эксцентричность, приближающуюся к 1, [ 9 ] Орбитальный наклон 139–144 ° (исключая тесные встречи с планетами), [ 10 ] Перигеляционное расстояние менее 0,01 АС (меньше диаметра солнца [ 11 ] ), афелион расстояние около 100 ат [ 12 ] и орбитальный период около 500–1000 лет. [ 4 ] Эрозия комет солнечной энергией во время близких отрывков приводит к прогрессивным изменениям в их орбитах. [ 13 ]

Большинство Sungrazers Kreutz имеют радиусы менее 100 метров (330 футов), но самые яркие радиусы достигают 1–10 километров (0,62–6,21 миль). [ 14 ] Сами тела имеют нерегулярные формы [ 15 ] и появления, которые были описаны как диффузные, звездные или хвостовые. [ 16 ] Материал, который составляет их комеревые ядра, имеет низкую прочность на растяжение . [ 17 ] У них есть только низкие концентрации летучих веществ и, таким образом, становятся активными только близко к солнцу, [ 18 ] так как они потеряли большую часть своих летучих веществ во время более ранних транзитов. [ 19 ] Их яркость может питься незадолго до перигелия при 10–15 солнечных радиусах, [ 20 ] после чего они становятся диммером. Это может быть связано с испарением минералов, таких как оливин и пироксен . [ 15 ] Другие исследования находят более хаотический рисунок осветления и затемнения. [ 19 ] Вода и органические материалы кометы испаряются в первую очередь, обнажая пушистые агрегации оливинов, которые образуют пылевые хвосты. [ 21 ] Пыль из этих комет остается в солнечной короне , где она взаимодействует с солнечным магнитным полем . [ 22 ]

Примечательные члены

[ редактировать ]Самые яркие члены Sungrazers Kreutz были впечатляющими, легко видимыми в дневном небе. Три наиболее впечатляющими были великая комета 1843 года , великая комета 1882 года и X/1106 C1 . Предшественник всех Sungrazers Kreutz, наблюдаемых на сегодняшний день, может быть великой кометой 371 г. до н.э. , [ 23 ] или кометы, видимые в 214 г. до н.э., 423 г. н.э. или 467 г. н.э. [ 6 ] Другим известным Sungrazer Kreutz была комета Eclipse 1882 года . [ 1 ] Другими кандидатами Кройц Сангрзазеры являются кометами, наблюдаемыми в 582 году нашей эры в Китае и Европе, [ 24 ] X/1381 V1, который был замечен из Японии, Кореи, России и Египта, [ 25 ] Две кометы, увиденные в 1668 и 1695 годах, [ 26 ] C/1880 C1, Великая южная комета 1887 года , [ 27 ] C/1945 x1 (крыша), [ 28 ] C/1970 K1 [ 27 ] и C/2005 S1, один из лучших солнечных солнечных ресурсов Kreutz. [ 29 ]

Великая комета 371 г. до н.э.

[ редактировать ]Великая комета, увиденная зимой 372–371 г. до н.э., была чрезвычайно яркой кометой, которая, как считается, является предшественником всей семьи Кройц Сангр. Это было отмечено Аристотелем и Эфором в период, когда он был виден невооруженным глазом. Сообщалось, что у него был чрезвычайно длинный, чрезвычайно яркий, выдающийся хвост с красноватым цветом, а также ядро ярче, чем любая звезда в ночном небе. [ 23 ]

Великая комета 1106 г.

[ редактировать ]Великая комета 1106 года объявлений была гигантской кометой, замеченной наблюдателями со всего мира. 2 февраля 1106 г. н.э. Похоже, что после этого яркости он уменьшился в яркости, с довольно слабым, ничем не примечательным ядром после перигелия, но его хвост значительно вырос, а 7 февраля японские наблюдатели сказали, что чрезвычайно ярко -белый хвост простирался примерно на 100 градусов по всему ночному небу, который также был Сообщается, что он разветвлялся в несколько хвостов. 9 февраля он немного погрузился, но его хвост все еще был чрезвычайно ярким, составлял 60 градусов в длину и 3 градуса в поперечнике. Вся продолжительность обнаженной глаз гигантской кометы была зарегистрирована как где-то от 15 до 70 дней в европейских текстах. Недавние оценки, а также наблюдения за расщеплением кометы на несколько частей после перигелиона предположили, что эта комета была прародителем целой подгруппы солнечных средств Kreutz, включая чрезвычайно яркие солнцезащитные сечения 1882, 1843 и 1965 годы. Наблюдения также предполагают, что Большой фрагмент великой кометы 371 г. до н.э. позже вернулся в качестве великой кометы 1106 г. н.э. [ 30 ]

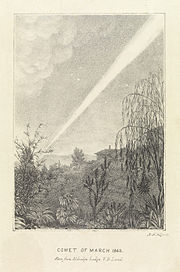

Великая комета 1843 года

[ редактировать ]The Great Comet of 1843 was first noticed in early February of that year, just over three weeks before its perihelion passage when it passed about 830,000 kilometres (520,000 mi) from the surface of the Sun.[31] By February 27 it was easily visible in the daytime sky,[32] and observers described seeing a tail 2–3° long stretching away from the Sun before being lost in the glare of the sky. After its perihelion passage, it reappeared in the morning sky,[32] and developed an extremely long tail. It extended about 45° across the sky on March 11 and was more than 2° wide;[33] the tail was calculated to be more than 300 million kilometers (2 AU) long. This held the record for the longest measured cometary tail until 2000, when Comet Hyakutake's tail was found to stretch to some 550 million kilometers in length. The maximum apparent magnitude attained by this comet was −10. (The Earth–Sun distance—1 AU—is only 150 million kilometers.)[34][35]

The comet was very prominent throughout early March, before fading away to almost below naked eye visibility by the beginning of April.[33] It was last detected on April 20. This comet apparently made a substantial impression on the public, inspiring in some a fear that judgement day was imminent.[32]

Eclipse Comet of 1882

[edit]A party of observers gathered in Egypt to watch a solar eclipse in May 1882 also observed a bright streak near the Sun once totality began. The streak was the perihelion passage of a Kreutz comet, and its sighting during the eclipse was the only observation of it. Photographs of the eclipse revealed that the comet had moved noticeably during the 1m50s eclipse, as would be expected for a comet racing past the Sun at almost 500 km/s. The comet is sometimes referred to as Tewfik, after Tewfik Pasha, the Khedive of Egypt at the time.[2]

Great Comet of 1882

[edit]

The Great Comet of 1882 was discovered independently by many observers, as it was already easily visible to the naked eye when it appeared in early September 1882, just a few days before perihelion, at which it reached an apparent magnitude estimated to have been −17, by far the brightest recorded for any comet and exceeding the brightness of the full moon by a factor of 57.[35] It grew rapidly brighter and was eventually so bright it was visible in the daytime for two days (16–17 September), even through light cloud.[36]

After its perihelion passage, the comet remained bright for several weeks. During October, its nucleus was seen to fragment into first two and then four pieces. Some observers also reported seeing diffuse patches of light several degrees away from the nucleus. The rate of separation of the fragments of the nucleus was such that they will return about a century apart, between 670 and 960 years after the break-up.[6]

Comet Ikeya–Seki

[edit]Comet Ikeya–Seki is the most recent very bright Kreutz sungrazer. It was discovered independently by two Japanese amateur astronomers on September 18, 1965, within 15 minutes of each other, and quickly recognised as a Kreutz sungrazer.[2] It brightened rapidly over the following four weeks as it approached the Sun, and reached apparent magnitude 2 by October 15. Its perihelion passage occurred on October 21, and observers across the world easily saw it in the daytime sky.[2] A few hours before perihelion passage on October 21 it had a visible magnitude from −10 to −11, comparable to the first quarter of the Moon and brighter than any other comet seen since 1882. A day after perihelion its magnitude decreased to just −4.[37]

Japanese astronomers used a coronagraph to observe how the comet broke into three pieces 30 minutes before perihelion. When the comet reappeared in the morning sky in early November, two of these nuclei were definitely detected with the third suspected. The comet developed a very prominent tail, about 25° in length, before fading throughout November. It was last detected in January 1966.[38]

Dynamical history and evolution

[edit]

A study by Brian G. Marsden in 1967 was the first attempt to trace back the orbital history of the group to identify the progenitor comet.[2][5] All known members of the group up until 1965 had almost identical orbital inclinations at about 144°, as well as very similar values for the longitude of perihelion at 280–282°, with a couple of outlying points probably due to uncertain orbital calculations. A greater range of values existed for the argument of perihelion and longitude of the ascending node.[5]

Marsden found that the Kreutz sungrazers could be split into two groups, with slightly different orbital elements, implying that the family resulted from fragmentations at more than one perihelion.[2] Tracing back the orbits of Ikeya–Seki and the Great Comet of 1882, Marsden found that at their previous perihelion passage, the difference between their orbital elements was of the same order of magnitude as the difference between the elements of the fragments of Ikeya–Seki after it broke up.[39] This meant it was realistic to presume that they were two parts of the same comet which had broken up one orbit ago. The best candidate for the progenitor comet was the Great Comet of 1106: Ikeya–Seki's derived orbital period indicated that its previous perihelion matched that of 1106, and while the Great Comet of 1882's derived orbit implied a previous perihelion a few decades later, it would only require a small change in the orbital elements to bring it into agreement.[2]

The Sun-grazing comets of 1668, 1689, 1702 and 1945 seem to be closely related to those of 1882 and 1965,[2] although their orbits are not well enough determined to establish whether they broke off from the parent comet in 1106, or the previous perihelion passage before that, some time in the 3–5th centuries AD.[6] This subgroup of comets is known as Subgroup II.[40][1] Comet White–Ortiz–Bolelli, which was seen in 1970,[41] is more closely related to this group than Subgroup I, but appears to have broken off during the previous orbit to the other fragments.[1]

The Sun-grazing comets observed in 1843 (Great Comet of 1843) and 1963 (Comet Pereyra) seem to be closely related and belong to the subgroup I,[40] although when their orbits are traced back to one previous perihelion, the differences between the orbital elements are still rather large, probably implying that they broke apart from each other one revolution before that.[39] They may not be related to the comet of 1106, but rather a comet that returned about 50 years before that.[1] Subgroup I also includes comets seen in 1695, 1880 (Great Southern Comet of 1880) and in 1887 (Great Southern Comet of 1887), as well as the vast majority of comets detected by the SOHO mission (see below).[1]

The distinction between the two sub-groups is thought to imply that they result from two separate parent comets, which themselves were once part of a 'grandparent' comet which fragmented several orbits previously.[1] One possible candidate for the grandparent is a comet observed by Aristotle and Ephorus in 371 BC. Ephorus claimed to have seen this comet break into two. However modern astronomers are skeptical of the claims of Ephorus, because they were not confirmed by other sources.[6] Instead comets that arrived between 3rd and 5th centuries AD (comets of 214, 426 and 467) are considered as possible progenitors of the Kreutz family.[6] The original comet must certainly have been very large indeed, perhaps as large as 100 km across[1] although a size of only a few tens of kilometres, akin to Comet Hale–Bopp, is also possible.[42] One study suggests that the progenitor's orbit changed in a two-step process beginning in the Oort cloud: first, being perturbed into an ellipse whose semimajor axis was about 100 AU, and second, evolving into a sungrazing orbit via the Kozai mechanism.[43]

Although its orbit is rather different from those of the main two groups, it is possible that the comet of 1680 is also related to the Kreutz sungrazers via a fragmentation many orbits ago.[6]

The Kreutz sungrazers are probably not a unique phenomenon. Other families of sungrazing comets that formed from the breakup of a parent body are the Meyer sungrazers, the Marsden sunskirters and the Kracht sunskirters.[9][44] These form the 'non-Kreutz' or 'sporadic' sungrazers.[45] The Kreutz, Marsden and Kracht families and the comet 96P/Machholz may in turn form a larger family, the Machholz interplanetary complex, that may have formed through the breakup of a parent body before 950 CE.[46] The ultimate origin of the Kreutz sungrazers is probably the Oort cloud, with unknown physical processes reducing the semi-major axis until a sungrazing comet resulted. This process may occur a few times every million years, which may either be an underestimate or may indicate that humanity is lucky that such a Kreutz sungrazer family exists just now.[47] Studies have shown that for comets with high orbital inclinations and perihelion distances of less than about 2 AU, the cumulative effect of gravitational perturbations tends to result in sungrazing orbits.[48] One study has estimated that Comet Hale–Bopp has about a 15% chance of eventually becoming a Sun-grazing comet.[49] Comet families resembling the Kreutz group have been detected around the star Beta Pictoris.[50]

Recent observations

[edit]Until recently, a very bright member of the Kreutz sungrazers could pass through the inner Solar System unnoticed if its perihelion had occurred between about May and August.[1] At this time of year, as seen from Earth, the comet would approach and recede almost directly behind the Sun and could only become visible extremely close to the Sun if it became very bright. Only a remarkable coincidence between the perihelion passage of the Eclipse Comet of 1882 and a total solar eclipse allowed its discovery.[1]

During the 1980s, two Sun-observing satellites serendipitously discovered several new members of the Kreutz family. Since the launch of the SOHO Sun-observing satellite in 1995, it has been possible to observe comets very close to the Sun at any time of year.[6] The satellite provides a constant view of the immediate solar vicinity, and SOHO has now discovered hundreds of new Sun-grazing comets, some just a few metres across. About 83% of the sungrazers found by SOHO are members of the Kreutz group, with the others including the Meyer, Marsden, and Kracht1&2 families.[45] New Kreutz sungrazers are discovered roughly once every three days,[51] while many are likely going unobserved.[52] Their frequency increased from 1997–2002 to 2003–2008.[53] They probably have radii of only a few dozens of metres.[54] Apart from Comet Lovejoy, none of the sungrazers seen by SOHO has survived its perihelion passage; some may have plunged into the Sun itself, but most are likely to have simply evaporated away completely.[40][6] Centrifugal breakup is another important process that destroys smaller Kreutz sungrazers,[55] and may explain the delayed breakup of some Kreutz comets long after they passed through perihelion and are moving away from the Sun.[56]

The 1,000th known Kreutz sungrazer was observed by SOHO on 10 August 2006, and is named C/2006 P7 (SOHO).[57] As of June 2020[update], 85% or about 3,400 of the 4,000 comets that have been identified using SOHO data, mostly by amateur astronomers analysing SOHO's observations via the Internet, were Kreutz sungrazers.[58] As of February 2024[update], NASA's JPL Small-Body Database lists about 1,300 Kreutz sungrazers.[59]

Sungrazers frequently arrive in pairs or triplets[44] separated by a few hours. These pairs are too frequent to occur by chance, and cannot be due to break-ups on the previous orbit, because the fragments would have separated by a much greater distance.[6] Instead, it is thought that the pairs result from fragmentations far away from the perihelion. Many comets have been observed to fragment far from perihelion, and it seems that in the case of the Kreutz sungrazers, an initial fragmentation near perihelion can be followed by an ongoing 'cascade' of break-ups throughout the rest of the orbit.[6][48]

There are minor differences between Subgroup I and Subgroup II Kreutz sungrazers; the former come slightly closer to the Sun and the ascending nodes differ by about 20°.[40] The number of Subgroup I Kreutz comets discovered is about nine[60] to four times the number of Subgroup II members. This suggests that the 'grandparent' comet split into parent comets of unequal size.[6]

Future

[edit]Dynamically, the Kreutz sungrazers might continue to be recognised as a distinct family for many thousands of years. Eventually, their orbits will be dispersed by gravitational perturbations, although depending on the rate of fragmentation of the constituent parts, the group might be completely destroyed before it is gravitationally dispersed.[48] During 2002–2017, the occurrence of Kreutz sungrazers remained largely constant.[61]

It is not possible to estimate the chances of another very bright Kreutz comet arriving in the near future, but given that at least 10 have reached naked-eye visibility over the last 200 years, another great comet from the Kreutz family seems almost certain to arrive at some point.[41] Comet White–Ortiz–Bolelli in 1970 reached an apparent magnitude of 1.[62] In December 2011, Kreutz sungrazer C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy) survived its perihelion passage for some time[63] and had an apparent magnitude of −3.[64] This comet is probably not the herald of another arrival of bright Kreutz sungrazers.[65]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Sekanina, Zdeněk; Chodas, Paul W. (2004). "Fragmentation hierarchy of bright sungrazing comets and the birth and orbital evolution of the kreutz system. I. Two-superfragment model" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 607 (1): 620–639. Bibcode:2004ApJ...607..620S. doi:10.1086/383466. hdl:2014/39288. S2CID 53313156. Archived from the original on 2021-10-19. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Marsden, Brian G. (1967). "The sungrazing comet group". The Astronomical Journal. 72 (9): 1170–1183. Bibcode:1967AJ.....72.1170M. doi:10.1086/110396.

- ^ Kreutz, Heinrich Carl Friedrich (1888). "Untersuchungen über das cometensystem 1843 I, 1880 I und 1882 II". Kiel. Kiel, Druck von C. Schaidt, C. F. Mohr nachfl., 1888–91. Bibcode:1888uudc.book.....K.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Knight, Matthew M.; Walsh, Kevin J. (2013-09-24). "Will Comet Ison (C/2012 S1) Survive Perihelion?". The Astrophysical Journal. 776 (1): 2. arXiv:1309.2288. Bibcode:2013ApJ...776L...5K. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/776/1/L5. ISSN 2041-8205.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Sekanina, Zdeněk (2001). "Kreutz sungrazers: the ultimate case of cometary fragmentation and disintegration?" (PS). Publications of the Astronomical Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. 89 (89): 78–93. Bibcode:2001PAICz..89...78S. Archived from the original on 2011-05-26. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Sekanina, Zdeněk; Chodas, Paul W. (2007). "Fragmentation Hierarchy of Bright Sungrazing Comets and the Birth and Orbital Evolution of the Kreutz System. II. The Case for Cascading Fragmentation". The Astrophysical Journal. 663 (1): 657–676. Bibcode:2007ApJ...663..657S. doi:10.1086/517490. hdl:2014/40925. S2CID 56347169.

- ^ Thomas 2020, p. 437.

- ^ Królikowska, Małgorzata; Dybczyński, Piotr A (2019-04-11). "Discovery statistics and 1/ a distribution of long-period comets detected during 1801–2017". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 484 (3): 3464. arXiv:1901.01722. doi:10.1093/mnras/stz025. ISSN 0035-8711. Archived from the original on 2023-11-08. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Battams et al. 2017, p. 5.

- ^ Weissman, Paul; Morbidelli, Alessandro; Davidsson, Björn; Blum, Jürgen (February 2020). "Origin and Evolution of Cometary Nuclei". Space Science Reviews. 216 (1): 22. Bibcode:2020SSRv..216....6W. doi:10.1007/s11214-019-0625-7. ISSN 0038-6308. S2CID 255062842.

- ^ Kalinicheva, Olga V. (2018-11-01). "Comets of the Marsden and Kracht groups". Open Astronomy. 27 (1): 304. Bibcode:2018OAst...27..303K. doi:10.1515/astro-2018-0032. ISSN 2543-6376.

- ^ Dones, Luke; Brasser, Ramon; Kaib, Nathan; Rickman, Hans (December 2015). "Origin and Evolution of the Cometary Reservoirs". Space Science Reviews. 197 (1–4): 202. Bibcode:2015SSRv..197..191D. doi:10.1007/s11214-015-0223-2. ISSN 0038-6308. S2CID 123931232.

- ^ Barbieri, Cesare; Bertini, Ivano (2017-08-01). "Comets". La Rivista del Nuovo Cimento. 40 (8): 355. Bibcode:2017NCimR..40..335B. doi:10.1393/ncr/i2017-10138-4.

- ^ Fernández et al. 2021, p. 790.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thomas 2020, p. 432.

- ^ Battams et al. 2017, p. 8.

- ^ Jones et al. 2018, p. 34.

- ^ Raymond, J. C.; Downs, Cooper; Knight, Matthew M.; Battams, Karl; Giordano, Silvio; Rosati, Richard (2018-04-27). "Comet C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy) between 2 and 10 Solar Radii: Physical Parameters of the Comet and the Corona". The Astrophysical Journal. 858 (1): 12. Bibcode:2018ApJ...858...19R. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aabade. ISSN 1538-4357.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jones et al. 2018, p. 30.

- ^ Battams et al. 2017, p. 7.

- ^ Thompson, W.T. (November 2015). "Linear polarization measurements of Comet C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy) from STEREO". Icarus. 261: 130. Bibcode:2015Icar..261..122T. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.08.018. Archived from the original on 2024-03-09. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ Pesnell, W. D.; Bryans, P. (March 2014). "The Time-Dependent Chemistry of Cometary Debris in the Solar Corona". The Astrophysical Journal. 785 (1): 50. Bibcode:2014ApJ...785...50P. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/785/1/50. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Jump up to: a b England, K. J. (2002). "Early Sungrazer Comets". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 112: 13. Bibcode:2002JBAA..112...13E. Archived from the original on 2020-06-30. Retrieved 2020-06-30.

- ^ Osservatorio Astronomico Sormano (Italy); Sicoli, Piero; Gorelli, Roberto; A.R.A., Osservatorio Astronomico Virginio Cesarini; Martínez Uso, María José; Universitat Politècnica de Valencia; Marco Castillo, Francisco José; Universitat Jaume I (2023-10-16). Medieval comets: European and Middle Eastern Perspective (1 ed.). Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València. p. 83. doi:10.4995/sccie.2023.666301. ISBN 978-84-1396-153-8. Archived from the original on 2023-11-08. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ Bekli, Mohamed Reda; Chadou, Ilhem; Aissani, Djamil (March 2019). "THÉORIE DES COMÈTES ET OBSERVATIONS INÉDITES EN OCCIDENT MUSULMAN". Arabic Sciences and Philosophy. 29 (1): 100. doi:10.1017/S0957423918000103. ISSN 0957-4239. S2CID 171583671.

- ^ El-Bizri, Nader; Orthmann, Eva, eds. (2018). The Occult Sciences in Pre-modern Islamic Cultures. Ergon Verlag. p. 127. doi:10.5771/9783956503757. ISBN 978-3-95650-375-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jones et al. 2018, p. 6.

- ^ Battams et al. 2017, p. 6.

- ^ Jewitt, David (2021-06-01). "Systematics and Consequences of Comet Nucleus Outgassing Torques". The Astronomical Journal. 161 (6): 8. arXiv:2103.10577. Bibcode:2021AJ....161..261J. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/abf09c. ISSN 0004-6256.

- ^ "X/1106 C1". Archived from the original on 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2020-06-30.

- ^ Cottam, Stella; Orchiston, Wayne (2015). Eclipses, Transits, and Comets of the Nineteenth Century: How America's Perception of the Skies Changed. Astrophysics and Space Science Library. Vol. 406. Cham: Springer International Publishing. p. 23. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-08341-4. ISBN 978-3-319-08340-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hubbard, J.S. (1849). "On the orbit of Great comet of 1843". The Astronomical Journal. 1 (2): 10–13. Bibcode:1849AJ......1...10H. doi:10.1086/100004.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Observations of the great comet of 1843". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 6 (2): 3–6. 1843. Bibcode:1843MNRAS...6....3.. doi:10.1093/mnras/6.1.2.

- ^ Jones, Geraint H.; Balogh, André; Horbury, Timothy S. (2000). "Identification of comet Hyakutake's extremely long ion tail from magnetic field signatures". Nature. 404 (6778): 574–576. Bibcode:2000Natur.404..574J. doi:10.1038/35007011. PMID 10766233. S2CID 4418311.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stoyan, Ronald (8 January 2015). Atlas of Great Comets. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107093492. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "The comets of 1882". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 43 (2): 203–209. 1883. Bibcode:1883MNRAS..43R.203.. doi:10.1093/mnras/43.4.203.

- ^ Opik, EJ (1966). «Солнцезащитные кометы и приливные нарушения». Ирландский астрономический журнал . 7 (5): 141–161. Bibcode : 19666Iraj .... 7..141o .

- ^ Hirayama, T.; Морияма, Ф. (1965). «Наблюдения за Кометой Икией -Ски (1965f)». Публикации Астрономического общества Японии . 17 : 433–436. Bibcode : 1965pasj ... 17..433h .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Марсден, Б.Г. (1989). "Sungrazing Comet Group. II". Астрономический журнал . 98 (6): 2306–2321. Bibcode : 1989aj ..... 98.2306M . doi : 10.1086/115301 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Seargent 2017 , с. 103

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Секаина, Зденакк; Чодас, Пол В. (2002). «Фрагментация крупных солнечных комет C/1970 K1, C/1880 C1 и C/1843 D1» . Астрофизический журнал . 581 (2): 1389–1398. Bibcode : 2002Apj ... 581.1389S . doi : 10.1086/344261 .

- ^ Jones et al. 2018 , с. 24

- ^ Fernández et al. 2021 , с. 789–802.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Абедин, Абедин; Вигерт, Пол; Pokorný, Petr; Браун, Питер (январь 2017 г.). «Возраст и вероятное родительское тело дневного метеорного душа» . ИКАРС . 281 : 418. Bibcode : 2017icar..281..417a . doi : 10.1016/j.icarus.2016.08.017 . Архивировано из оригинала 2023-11-17 . Получено 2023-11-08 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Полный список соу и стереометов» . Британская астрономическая ассоциация и общество популярной астрономии. Октябрь 2008 года. Архивировано с оригинала 2011-08-05 . Получено 2008-11-07 .

- ^ Абедин, Абедин; Вигерт, Пол; Джанки, Диего; Pokorný, Petr; Браун, Питер; Hormaechea, Хосе Луис (январь 2018 г.). «Формирование и прошлая эволюция ливня комплекса 96p/macholz» . ИКАРС . 300 : 360. Bibcode : 2018icar..300..360a . doi : 10.1016/j.icarus.2017.07.015 .

- ^ Fernández et al. 2021 , с. 801.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Бейли, я; Chambers, Je; Хан, Г. (1992). «Происхождение солнечных людей-частые комеретические конечные состояния ». Астрономия и астрофизика . 257 : 315–322. Bibcode : 1992a & A ... 257..315b .

- ^ Бейли, я; Emel'annko, VV; Hahn, G.; тр. (1996). –1 Хейл Ежемесячные уведомления Королевского астрономического общества . 281 (3): 916–9 Bibcode : 1996mnra . Citeserx 10.1.29.6010 doi : 10.1093/mnras/281.3.3.916 .

- ^ Кифер, Ф.; Des Etangs, A. Lecavelier; Boissier, J.; Vidal-Madjar, A.; Бест, ч.; Лагранж, А.-М.; Hébrard, G.; Ферлет, Р. (октябрь 2014 г.). «Два семейства экзокометов в системе β -pictoris» . Природа . 514 (7523): 462–464. Bibcode : 2014natur.514..462K . doi : 10.1038/nature13849 . ISSN 0028-0836 . PMID 25341784 . S2CID 4451780 . Архивировано из оригинала 2023-11-08 . Получено 2023-11-08 .

- ^ «Космический корабль обнаруживает тысячи обреченных комет - наука НАСА» . Science.nasa.gov . Архивировано из оригинала 2015-10-28 . Получено 2015-10-26 .

- ^ Battams et al. 2017 , с. 9

- ^ Рыцарь, Мэтью М.; A'Hearn, Michael F.; Бизекер, Дуглас А.; Фари, Гийом; Гамильтон, Дуглас П.; Лами, Филипп; Llebaria, Antoine (2010-03-01). «Фотометрическое исследование кометов Кройца, наблюдаемое Сохо с 1996 по 2005 год» . Астрономический журнал . 139 (3): 948. Bibcode : 2010aj .... 139..926K . doi : 10.1088/0004-6256/139/3/926 . ISSN 0004-6256 .

- ^ Scholz, Mathias (2016). Астробиология (на немецком языке). Берлин, Гейдельберг: Спрингер Берлин Гейдельберг. п. 206. Bibcode : 2016asbi.book ..... s . doi : 10.1007/978-3-662-47037-4 . ISBN 978-3-662-47036-7 .

- ^ ДВИТТ, ДЭВИД (2021-06-01). «Систематика и последствия ядра кометы, раздачающихся крутящими моментами» . Астрономический журнал . 161 (6): 9. Arxiv : 2103.10577 . Bibcode : 2021aj .... 161..261J . doi : 10.3847/1538-3881/abf09c . ISSN 0004-6256 .

- ^ Jones et al. 2018 , с. 43

- ^ Милоне, Юджин Ф.; Уилсон, Уильям Дж.Ф. (2014). Солнечная система астрофизика: планетарная атмосфера и внешняя солнечная система . Библиотека астрономии и астрофизики. Нью -Йорк, Нью -Йорк: Springer New York. п. 604. Bibcode : 2014ssa..book ..... m . doi : 10.1007/978-1-4614-9090-6 . ISBN 978-1-4614-9089-0 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 2024-03-16 . Получено 2023-11-08 .

- ^ Фрейзер, Сара (2020-06-16). «4000 -я комета, обнаруженная Солнечной обсерваторией ESA & NASA» . НАСА . Архивировано из оригинала 2020-06-17 . Получено 2020-07-14 .

- ^ «Ретроградный объект возле орбиты Юпитера» . База данных малого тела . НАСА JPL. 29 февраля 2024 года. Отфильтрован с ограничением с помощью объекта Вид/Группа: Кометы и пользовательские ограничения орбиты/объекта: 120 ≤ I ≤ 150, Q <0,1, E> 0,9. Архивировано из оригинала 27 сентября 2021 года . Получено 29 февраля 2024 года .

- ^ Рыцарь, Мэтью М.; A'Hearn, Michael F.; Бизекер, Дуглас А.; Фари, Гийом; Гамильтон, Дуглас П.; Лами, Филипп; Llebaria, Antoine (2010-03-01). «Фотометрическое исследование кометов Кройца, наблюдаемое Сохо с 1996 по 2005 год» . Астрономический журнал . 139 (3): 927. Bibcode : 2010aj .... 139..926k . doi : 10.1088/0004-6256/139/3/926 . ISSN 0004-6256 .

- ^ Battams et al. 2017 , с. 15

- ^ Kronk, Gary W. "C/1970 K1 (белый Ortiz-Bolelli)" . Кометография Гэри У. Клка . Архивировано с оригинала 19 марта 2016 года . Получено 18 октября 2023 года .

- ^ Секанина, Зденек; Чодас, Пол В. (11 сентября 2012 г.). «Комета C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy): определение орбиты, вспышки, распад ядра, морфология пылевого хвоста и связь с новым кластером ярких солнечных солнечных средств» . Астрофизический журнал . 757 (2): 127. Arxiv : 1205.5839 . Bibcode : 2012Apj ... 757..127S . doi : 10.1088/0004-637X/757/2/127 . ISSN 0004-637X .

- ^ Филлипс, Тони (15 декабря 2011 г.). «Что случилось в космосе» . Spaceweather.com . Архивировано из оригинала 21 января 2012 года . Получено 28 декабря 2011 года .

- ^ Seargent 2017 , с. 106

- Battams, Карл; Найт, Мэтью М. (2017-07-13). «Soho Comets: 20 лет и 3000 объектов позже» . Философские транзакции Королевского общества A: математические, физические и инженерные науки . 375 (2097) 20160257. Arxiv : 1611.02279 . BIBCODE : 2017RSPTA.37560257B . doi : 10.1098/rsta.2016.0257 . ISSN 1364-503X . PMC 5454226 . PMID 28554977 .

- Фернандес, Юлий А; Лемос, Павел; Галлардо, Табаре (2021-09-28). Полем Ежемесячные уведомления Королевского астрономического общества . 508 (1): 789–8 doi : 10.1093/ mnras/ stab2 ISSN 0035-8711 .

- Джонс, Герайн Х.; Рыцарь, Мэтью М.; Battams, Карл; Бойс, Даниэль С.; Браун, Джон; Гиордано, Сильвио; Рэймонд, Джон; Снодграсс, Колин; Steckloff, Jordan K.; Вайсман, Пол; Фитцсиммонс, Алан; Лисс, Кэри; Opitom, Cyrielle; Биркетт, Кимберли с.; Bzowski, Maciej (февраль 2018 г.). «Наука солнечных, солнечных комет и других близких комет» . Обзоры космических наук . 214 (1) 20: 20. Bibcode : 2018ssrv..214 ... 20J . doi : 10.1007/s11214-017-0446-5 . HDL : 10037/13638 . ISSN 0038-6308 .

- Seargent, David AJ (2017). Странные кометы и астероиды . Вселенная астрономов. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi : 10.1007/978-3-319-56558-3 . ISBN 978-3-319-56557-6 .

- Томас, Николас (2020). Введение в кометы: пост-розетта перспективы . Библиотека астрономии и астрофизики. Cham: Springer International Publishing. Bibcode : 202020icpr.book ..... t . doi : 10.1007/978-3-030-50574-5 . ISBN 978-3-030-50573-8 Полем S2CID 242251125 .

Дальнейшее чтение

[ редактировать ]- Marsden BG (1989), Sungrazing Comets Revisited , Asteroids, Comets, Meteors III, Труды собрания (AMC 89), Uppsala: Universitet, 1990, Eds CI Lagerkvist, H. Rickman, Ba Lindblad., P. 393

- Ли, Сугюн; Yi, yu; Ким, Юн Ха; Брандт, Джон С. (2007). «Распределение перигелии для солнечных комет Soho и проспективных групп» . Журнал астрономии и космических наук . 24 (3): 227–234. Bibcode : 2007jass ... 24..227L . doi : 10.5140/jass.2007.24.3.227 .

Внешние ссылки

[ редактировать ]- Сайт Sungrazer Project Archived 2015-05-25 в The Wayback Machine

- Страница группы SEDS KREUTZ

- Cometography Sungrazers Page Archived 2005-03-08 в The Wayback Machine

- Пресс -релиз НАСА о двух солнцезащитах, увиденных Сохо

- Полный список комет Soho

- Данные SOHO в реальном времени