Родни, Миссисипи

Родни, Миссисипи | |

|---|---|

Бывшая первая пресвитерианская церковь | |

| Прозвище (ы): "Миниатюрная залива", "Маленькая залива" [ 1 ] | |

| Координаты: 31 ° 51′40,6 ″ с.ш. 91 ° 11′59,4 ″ ш / 31,861278 ° с.ш. 91,199833 ° С | |

| Страна | Соединенные Штаты |

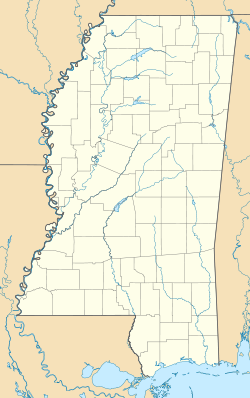

| Состояние | Миссисипи |

| Графство | Джефферсон |

| Основан | 1828 |

| Возвышение | 82 фута (25 м) |

| Часовой пояс | UTC-6 ( Central (CST) ) |

| • Лето ( DST ) | UTC-5 ( CDT ) |

| GNIS Идентификатор функции | 676809 [ 1 ] |

Родни - город -призрак в округе Джефферсон, штат Миссисипи , США. [ 1 ] Большинство зданий исчезли, а остальные структуры находятся в различных состояниях разрушения. Город регулярно наводняет, и здания имеют большой ущерб от наводнения. Общество истории и сохранения Родни восстанавливает пресвитерианскую церковь Родни . Ущерб фасаду церкви от американской гражданской войны сохранялся в рамках исторической консервации, в том числе реплика, встроенный над окнами балкона. Исторический район Центра Родни находится в Национальном реестре исторических мест . [ 2 ]

Город находится примерно в 32 милях (51 км) к северо -востоку от Натчез . В настоящее время он находится на расстоянии около двух миль от реки Миссисипи. Между городом и Миссисипи находятся водно -болотные угодья, в том числе озеро, которое примерно следует за бывшим курсом реки. На вершине Лесесса Блефов за Родни находятся его кладбище и конфедеративные земляные работы из гражданской войны.

Родни был культурным центром региона в начале 1800 -х годов. В 1817 году это было три голоса от того, чтобы стать столицей Миссисипи. [ 3 ] Важный гибридный штамм хлопка под названием Petit Gulf Chotch и инновации в хлопковом джине был разработан в Родни из Rush Nutt . Родни был включен в 1828 году и стал основным портом для окрестностей, с населением в тысячах. К 1860 году город был домом для различных предприятий, нескольких газет и Оклендского колледжа . Во время гражданской войны кавалерия армии Конфедеративных Штатов захватила экипаж армейского корабля Союза , который присутствовал на службе в Пресвитерианской церкви Родни , в результате чего обстрел города. После войны река Миссисипи изменила курс, железная дорога обошла область, и почти все здания сгорели. Население сократилось до тех пор, пока город не будет отказан в 1930 году. [ 4 ] К 2010 году сообщалось, что только «рука, полная людей», жила в Родни. [ 5 ]

История

[ редактировать ]

Посадочная площадка Родни была ключевой путевой точкой на маршрутах коренных американцев вокруг региона Дельты Миссисипи . [ 8 ] Артефакты коренных американцев были обнаружены между Natchez Trace Overland Route и Rodney. [ 8 ] Люди Натчез, вероятно, использовали этот район в качестве портажа между рекой Миссисипи и Белой яблочной деревней . [ 8 ]

В январе 1763 года этот район был претендент на « миниатюрное залив » в отличие от Гранд -Персидского залива, Миссисипи, UPRIVER. [ 9 ] Название упоминается в входе или узкий изгиб в реке, вниз по течению от Байу Пьера . [ 10 ] После французской и индийской войны регион был устужден Великобритании. [ 11 ] Самый ранний известный грант на землю был для мистера Кэмпбелла в 1772 году. [ 12 ] Испания взяла под свой контроль в 1781 году и предоставила множество земельных грантов в Западной Флориде англо -иммигрантам . [ 13 ] Американские поселенцы, в том числе семьи Nutt и Calvit, переехали в район, который станет Родни. [ 14 ] Испания потеряла контроль над области в 1798 году, [ 15 ] [ 16 ] и 2 апреля 1799 года территория Миссисипи была организована в рамках Соединенных Штатов . [ 17 ] Три года спустя мировой судья из Делавэра Томас Родни был отправлен в округ Джефферсон в качестве территориального судьи. [ 18 ] [ 19 ]

In 1807, Secretary of the Mississippi Territory Cowles Mead assembled a militia to capture Aaron Burr at Coles Creek, just south of Rodney.[20] Burr was held at Thomas Calvit's home while under investigation for treason.[21] Thomas Rodney presided over the Aaron Burr conspiracy trial and became Chief Justice of the Mississippi Territory.[22][23] The town was renamed after him in 1814.[24] Rodney was more significant to the region than Vicksburg or Natchez in the early 1800s.[9] In 1817, the Mississippi Territory was being admitted as a state, and Rodney came three votes short of becoming the capital.[25]

Growth

[edit]

Rodney emerged as a thriving river port. The town was right on the water with the river running parallel to its major streets.[26][27] It was the primary shipping location for a broad swath of Mississippi, especially for cotton.[28] According to historian Keri Watson, enslaved dockworkers loaded "millions of pounds of cotton" onto steamboats bound for New Orleans.[24] Due to a shortage of legal tender, cotton receipts became de facto currency.[29] During this period, many of the coins that were available were Spanish picayunes and bits.[12] According to a Jefferson County native who had a store in Rodney in the 1830s and 1840s, "The northwest or Rodney district [of Jefferson County] was the home of McGill, Hubbard, Hopkins, Mackey, Turnbull, Rabb, Bradshaw, Sisson, Porter, Johnson and Caleb Potter, the last three of whom were Revolutionary soldiers, for whom I drew pensions. They were in the battle of Monmouth, and when Lafayette visited Natchez in 1825, we dressed up the old fellows and sent them down. The General embraced and kissed them, and they all cried like school boys."[30]

Rodney became a cultural center and incorporated in 1828.[9] Rodney resident Rush Nutt demonstrated effective methods to power cotton gins with steam engines in 1830.[31] The importation of different types of cotton seeds resulted in the breeding of a disease-resistant and easy-to-harvest hybrid that became known as Petit Gulf cotton.[31] The "seed business" in Rodney served customers as far away as the North Carolina Piedmont.[32] The development of Petit Gulf cotton and the Indian Removal Act of 1830 spurred a westward land rush.[24] Many early settlers of Texas crossed through Rodney. Their wagons were poled across the water on flatboat ferries to St. Joseph, Louisiana.[25] From 1820 to 1830, Rodney was the primary Mississippi River crossing for Americans migrating to the Southwest.[12]

Several historical structures were built during this time including Rodney Presbyterian Church, U.S. president Zachary Taylor's plantation, and portions of Alcorn University, originally a Presbyterian college.[33][23] The initial building that had been used for church services in town doubled as a tavern, serving alcohol outside of Sunday.[34] In 1829, the first steps were taken to erect the red-brick Presbyterian church.[34] One year later, the Presbyterian Oakland College was chartered.[35] The college was built on 250 acres (100 ha) near the town.[36] In its first few years, the college operated from six cottages north of Rodney.[27] Construction began on the college's main building, the Greek-revival Oakland Memorial Chapel in 1838.[37] Zachary Taylor's Cypress Grove Plantation, Nutt's Laurel Hill, and other plantation homes were built around Rodney during this period.[24] Before the Civil War, the town had two major newspapers, The Southern Telegraph and Rodney Gazette.[38][39] In 1836, the tagline of The Southern Telegraph was "He that will not reason, is a bigot; he that cannot, is a fool; and he that dare not, is a slave."[40]

However, growth was already slowing by the 1840s when a Mississippi guidebook stated, "Its progress, some years ago, was very rapid, and much improvement was made, but it has been reputed to be very unhealthy, and, of late years, it has improved but very little." Still, it had several stores and "commission houses," a grist mill, a saw mill, and a church.[41]

Civil War

[edit]

During the Civil War, a group of Union Army soldiers were captured at Rodney's Presbyterian Church.[42] Part of the Union's strategy during the Civil War was their plan to advance down the Mississippi River, dividing the Confederacy in half.[43] The Union's USS Rattler was a side-wheel steamboat, retrofitted into a lightly armored warship.[44] After the Union captured the fortress city of Vicksburg, they took control of river traffic on the Mississippi. Rattler was one of many ships tasked with maintaining this control by preventing Confederate crossings. Rattler was anchored in the river near Rodney's landing in September 1863.[45] Much of the town, including the surviving red-brick church, was directly visible from the water at that time.[3]

When Reverend Baker from the Red Lick Presbyterian Church traveled to Rodney via steamboat, he invited Rattler's crew to come ashore and attend services in what was still Confederate territory.[45] On Sunday, September 13, 1863, seventeen men departed from Rattler to attend the 11 am service.[45] Only a single crewmember brought a firearm to the service.[45] Confederate cavalry surrounded the building when the volume of the music was loud enough to cover their approach.[45][12] The troops entered the building and quickly captured the Northern soldiers with some assistance from members of the congregation.[45]

When reports reached the ship, Rattler began to fire upon the town; a cannonball lodged into the church above the balcony window. The shelling ceased when Confederate soldiers threatened to execute their Union prisoners.[3] Lt. Commander James A. Greer aboard the USS Benton anchored upstream near Natchez, admonished Rattler's captain for acting as a civilian during a time of war. He issued orders to arrest any officer found "leaving his vessel to go on shore under any circumstances".[45]

Decline

[edit]

Rodney gradually went from a major port to a ghost town after the river changed course.[9] In 1860, Rodney was home to banks, newspapers, schools, a lecture hall, Mississippi's first opera house, a hotel, and over 35 stores.[46][47] At its peak, thousands of people resided in the town.[3]

During the time of the Civil War, the Mississippi River began to change course.[45] A sand bar developed upstream and pushed the river west.[2] Rodney's former shipping channel transformed into a swamp.[45] The Rodney Landing was relocated several miles away from the town itself.[48] Many male residents who left the town during the war never returned, and many businesses that closed, never reopened.[12] In 1869, a fire consumed most of the buildings in town; the Presbyterian church survived.[45] In 1880, German and Irish immigrants arrived and opened new businesses.[49] The town endured multiple yellow fever outbreaks.[24] The railroad bypassed the town. The rail line ran through Jefferson County's seat of government, Fayette, and Rodney's landing was abandoned.[45] There are no records of any boats using the landing after 1900.[50]

Still, some residents remained in the vicinity, including an African-American man named Bob Smith, who had been marshal of Rodney "during Reconstruction days." According to the WPA history of Jefferson County published in 1938, "For ten years the old dinner bell that was rung three times daily by old black BOB SMITH has been silent. In the now deserted-looking village of Rodney, on Main Street; Bob operated a hotel in just a modest frame structure, but the delicious meals served in the crude dining room were the wonder of all the traveling men and others who happened to be in Rodney. The fried chicken, hot cakes, fish, figs, etc. in season, were the topic of conversation whenever fellow travelers chanced to meet."[10] One newspaperman wrote in 1939, "They say Rodney was once a fine place to get a filling meal in decades gone—one negro caterer, there famous for his cookery and bountiful supply was also noted for the great stacks of savory froglegs he never failed to serve his white patrons."[51]

In 1930, Governor Theodore G. Bilbo disincorporated Rodney.[9] By 1938, Mississippi: A Guide to the Magnolia State described Rodney as "a ghost river town" that had died when the railroad passed it by.[9]

It was in this state of decline that novelist Eudora Welty found the town.[9] Rodney became a setting in Welty's works including the novella The Robber Bridegroom.[24] Welty wrote, "The river had gone, three miles away, beyond sight and smell, beyond the dense trees. It came back only in flood."[24] Photographer Marion Post Wolcott documented Rodney for the Farm Security Administration circa 1940 and described it as a "fantastic deserted town".[52][53]

Extant structures

[edit]

A ruined cemetery, several stores, a couple of churches, and few houses remain, in various states of disrepair. The red-brick Rodney Presbyterian Church, built in 1832,[3] is a federal-style church and the oldest remaining building in Rodney.[3][54] The Presbyterian church has fanlights above the doors similar to federal-style homes in Mississippi, like Rosalie Mansion.[54] The church's interior was lit with oil lamps and heated with a pair of stoves. A slave gallery in the rear can be accessed by a side door leading into a narrow, winding staircase.[51] It was built on on ground high enough to escape the town's regular flooding and has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1972.[55] The Rodney History and Preservation Society purchased the church to conduct repairs.[55] When the church was being restored, the hole created by Union cannonfire during the Civil War was retained and a replica cannonball was placed in the exterior wall.[45] Atop the hill adjacent to the church is a cemetery with graves dating back over a century.[56] It contains the graves of many early settlers from across the river in Louisiana who brought their dead to be buried on high ground above the floodplain.[12]

Mt. Zion Baptist Church was built in 1851.[55] It uses a combination of architectural styles.[2] The pointed arches are Greek Revival, the pedimented gable is Gothic Revival, and the domed cupola is federal-style.[54] Mt. Zion Baptist originally had a white congregation, became a predominantly African American church after the white population began to abandon the town, and is now completely abandoned.[3] Changes in the course of the Mississippi River have resulted in repeated flooding.[55] The structure shows clear signs of flood damage including water lines and rotted floors.[55] The road sign pointing towards the church becomes visible in autumn when the leaves fall away from the vines overgrowing the signpost.[55] Surviving members of the church formed the Greater Mount Zion church several miles away and outside of the flood zone.[3]

Alston's Grocery, built circa 1840, is south of the Presbyterian Church at what was once the intersection of Commerce Street and Rodney Road.[55] The Sacred Heart Catholic Church, was built in Rodney circa 1868, and the entire building was relocated to Grand Gulf Military State Park in 1983.[57][3] The gable-front Masonic lodge was built circa 1890.[55] Only a small handful of people still live in the area, and most of the remaining buildings are abandoned.[3]

Geography

[edit]

Rodney is located near the southern end of the Natchez Trace, a forest trail that stretches for hundreds of miles across North America. The Trace was started by animal migration along a geologic ridge line.[58][59] The town is approximately 32 miles (51 km) northeast of Natchez, south of Bayou Pierre (Mississippi), and about 2 miles inland from the east bank of the Mississippi River.[9][1][60] It is situated on loess bluffs that are within the Mississippi River watershed and that were once adjacent to the river.[2] Wetlands including a lake that roughly follows the river's old course are immediately west of the town.[61] The town is at a relatively low elevation, and prone to seasonal flooding. When the river ran past Rodney, its position on the lower bluffs above steep river banks created an ideal position for a river landing. Civil War–era earthworks are still present atop the bluffs that rise above the town.[2]

Notable people

[edit]- James Cessor, member of the Mississippi House of Representatives from 1871 to 1877[62]

- Thomas Hinds Duggan, former member of the Texas Senate[63]

- Bill Foster, member of the Baseball Hall of Fame[64]

- Charles Pasquale Greco, Bishop of Alexandria in Louisiana from 1946 to 1973 and Supreme Chaplain of the Knights of Columbus from 1961 to 1987[65]

- Reuben C. Weddington, former member of the Arkansas House of Representatives[66]

- Zachary Taylor, the 12th president of the United States built his Buena Vista plantation just south of Rodney.[24]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c d U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Rodney. Retrieved March 4, 2024. Archived from the original.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Rodney Center Historic District". National Park Service. Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Ghost Town on the Mississippi. The Steeple. PBS. January 11, 2013. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ Logan, Mary T. (1980). Mississippi–Louisiana Border Country (Revised 2nd ed.). Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Claitor's. LCCN 70-137737.

- ^ Grayson, Walt (August 26, 2010). "Rodney Presbyterian Church". WLBT3. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016.

- ^ D'Addario (December 19, 2019). "Review: Landscape art at NOMA entwines history, geography to show Louisiana as a world apart". NOLA. Retrieved June 29, 2024.

- ^ Carter, Kate (October 24, 2016). "Robert Brammer". 64 Parishes. Retrieved June 29, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Logan 1980, p. 4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h McHaney, Pearl Amelia (Spring 2015). "Eudora Welty's Mississippi River: A View from the Shore". The Southern Quarterly. 52 (3): 66–68. ISSN 2377-2050.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Powell, Susie V., ed. (1938). Jefferson County (PDF). Source Material for Mississippi History, Volume XXXII, Part I. WPA Statewide Historical Research Project. pp. 12–14, 308–309 – via mlc.lib.ms.us.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f McIntire, Carl (June 20, 1965). "Old, Once Rich, Busy, Rodney Fading Away". Clarion-Ledger. Jackson, Mississippi. p. 57 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 12.

- ^ Rowland, Dunbar, ed. (1925). History of Mississippi, the Heart of the South. Vol. 2. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company. p. 750 – via Google Books.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 16.

- ^ Haynes, Robert (2010). "Prologue". The Mississippi Territory and the Southwest Frontier, 1795-1817. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 1–5.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 17.

- ^ Haynes 2010, pp. 132–133

- ^ Logan 1980, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Haynes 2010, p. 157

- ^ Logan 1980, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 19.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Roland, Dunbar, ed. (1907). "Mississippi". Atlanta: Southern Historical Publishing Association. pp. 573–574. Archived from the original on March 4, 2024. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Watson, Keri (Spring 2023). ""You Know Who I Am? I'm Mr. John Paul's Boy"". Southern Cultures. 29 (1). ISSN 1068-8218. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Logan 1980, p. 49.

- ^ Logan 1980, pp. 45–50.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Reminiscences of Historic Rodney and Oakland College". Tensas gazette. Saint Joseph, Louisiana. Fayette Chronicle. October 15, 1926. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 58.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 22.

- ^ Watkins, W. H., ed. (n.d.). Some Interesting Facts of the Early History of Jefferson County, Mississippi. No publisher or publication date stated; includes a biography of John A. Watkins by R. S. Albert, two previously published articles by John A. Watkins, and one previously published article by V. N. Russell. p. 15. OCLC 17887012. F347.J42 W3 – via University of Mississippi Libraries Special Collections, Oxford, Mississippi.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moore, John Hebron (1986). "Two Cotton Kingdoms". Agricultural History. 60 (4): 8, 11. ISSN 0002-1482. JSTOR 3743249. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ James, D. Clayton (1993) [1968]. Antebellum Natchez. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-8071-1860-3. LCCN 68028496. OCLC 28281641.

- ^ "Limerick (J. A.) manuscripts". Mississippi Department of Archives and History, ID: Z/1140.000/F. Manuscript Collections.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Logan 1980, p. 56.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 57.

- ^ "Oakland College". Mississippi Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on March 4, 2024. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ "Oakland Chapel". Mississippi Department of Archives & History. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Southern Telegraph (Rodney, Miss.) 1834-1838". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Mississippi: Embracing an Authentic and Comprehensive Account of the Chief Events in the History of the State and a Record of the Lives of Many of the Most Worthy and Illustrious Families and Individuals. Vol. 2. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing. 1891. p. 212.

- ^ "Mar 17, 1836, page 1 - The Rodney Telegraph at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Conclin's new river guide, or, A gazetteer of all the towns on the western waters : containing sketches of the cities, towns, and countries bordering on the ..." HathiTrust. 1848. p. 102. hdl:2027/uiuo.ark:/13960/t6542sg0x. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ "History of Rodney Mississippi". Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ Wolfe, Brendan. "Anaconda Plan". Encyclopedia Virginia. Archived from the original on March 4, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ "USS Rattler". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Central Arkansas Library System. October 14, 2020. Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l "Stanley Nelson: The Rattler, the Tensas & Rodney". Concordia Sentinel. September 4, 2019. ISSN 0746-7478. Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ "Little remains from the once prosperous city of Rodney". The Natchez Democrat. May 13, 2009. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ Logan 1980, pp. 58–67, 72, 334.

- ^ Logan 1980 , p. 99

- ^ Logan 1980 , p. 98

- ^ Макинтир, Карл (20 июня 1965 г.). "Родни" . Кларион-Леджер . Джексон, Миссисипи. п. 64 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный "Vicksburesque от VBR" . Виксбургский пост . Виксбург, Миссисипи. 10 мая 1939 г. с. 4 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Хендриксон, Пол (1992). Ищу свет: скрытая жизнь и искусство Марион Пост Волкотт . Кнопф. п. 178. ISBN 978-0-394-57729-6 .

- ^ «Родни, Миссисипи, август 1940 года» . NYPL Digital Collections . Архивировано из оригинала 26 марта 2024 года . Получено 26 марта 2024 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Пейс, Шерри (2007). Исторические церкви Миссисипи . Оксфорд, Миссисипи: Университетская пресса Миссисипи. С. XI, 137–138. ISBN 9781617034091 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 5 марта 2024 года . Получено 5 марта 2024 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час «Сохранение города -призрачного города Миссисипи» . Кларион-Леджер . 31 октября 2019 года. ISSN 0744-9526 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2024 года . Получено 2 марта 2024 года .

- ^ "Церковь" . Гранд -военный парк . Штат Миссисипи. Архивировано из оригинала 10 декабря 2023 года . Получено 3 марта 2024 года .

- ^ Тернер-Нил, Крис (29 августа 2016 г.). «История Миссисипи вдоль трассировки Натчез» . Журнал Country Roads . Архивировано из оригинала 3 марта 2024 года . Получено 3 марта 2024 года .

- ^ «Натчез трассировки» . Миссисипи энциклопедия . Архивировано из оригинала 26 сентября 2023 года . Получено 3 марта 2024 года .

- ^ Logan 1980 , p. 3

- ^ Logan 1980 , с. 110–111.

- ^ «Джеймс Д. Сессор (округ Джефферсон)» . Несмотря на все шансы: первые черные законодатели в Миссисипи . Архивировано из оригинала 17 октября 2021 года . Получено 17 октября 2021 года .

- ^ «Дагган, Томас Хиндс (1815–1865)» . Справочник Техаса . Архивировано из оригинала 17 октября 2021 года . Получено 17 октября 2021 года .

- ^ «Билл Фостер» . Зал славы спорта Миссисипи . Архивировано с оригинала 3 января 2015 года . Получено 2 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Епископ Чарльз П. Греко, 6 -й епископ Александрии» . Епархия Александрия . Архивировано из оригинала 17 октября 2021 года . Получено 17 октября 2021 года .

- ^ «AHQ: Черные законодатели в Арканзасе, 231» . Южный Арканзасский университет - Магнолия . Архивировано из оригинала 17 октября 2021 года . Получено 17 октября 2021 года .

Дальнейшее чтение

[ редактировать ]- Брукхарт, Мэри Хьюз; Маррс, Сюзанна (1986). «Больше заметок о речной стране» . Миссисипи ежеквартально . 39 (4): 507–519. ISSN 0026-637X . JSTOR 26475367 .

- Митчам, Говард (октябрь 1953 г.). «Старый Родни, город -призрак Миссисипи». Журнал истории Миссисипи . 15 (4). Джексон, Миссисипи: Историческое общество Миссисипи в сотрудничестве с Департаментом архивов и истории Миссисипи: 242–251. ISSN 0022-2771 . OCLC 1782329 .

Внешние ссылки

[ редактировать ]![]() СМИ, связанные с Родни, штат Миссисипи, в Wikimedia Commons

СМИ, связанные с Родни, штат Миссисипи, в Wikimedia Commons

- «Призрак города Родни» . Гид для путешествий Southpoint. Архивировано из оригинала 29 мая 2008 года . Получено 8 июля 2008 года .

- «Исторические маркеры в Родни, Миссисипи» .

- «Джозеф Кальвит и его семья в Миссисипи» .

- «Черч -холм округа Джефферсон № 26 & #27 из WPA Records» . Архивировано из оригинала 21 марта 2019 года.

- 1828 заведения в Миссисипи

- 1930 DISESTABLASTIONS в Миссисипи

- Федеральная архитектура в Миссисипи

- Бывшие населенные места в округе Джефферсон, штат Миссисипи

- Города призраков в Миссисипи

- Архитектура готического возрождения в Миссисипи

- Заселенные места Миссисипи на реке Миссисипи

- Заселенные места, установленные в 1828 году

- Заселенные места, зарегистрированные в 1930 году.