Герман архидиакон

Герман Архидиакон (также Герман Архидиакон [ 2 ] и Герман из Бери , [ 3 ] Родился до 1040 года, умер в конце 1090 -х годов) был членом семьи Херста , епископа Восточной Англии , в 1070 -х и 1080 -х годах. После этого он был монахом аббатства Бери Святого Эдмундса в Саффолке до конца своей жизни.

Герман, вероятно, родился в Германии . епископа Около 1070 года он вошел в дом Херста, и, согласно более позднему источнику, он стал архидиаконом , который в то время стал важной секретарской позицией. Он помог Хериста в его неудачной кампании по перемещению своего епископства в Аббатство Святого Эдмундса против противостояния его настоятеля, и помог вызвать временное примирение между двумя людьми. Он оставался с епископом до своей смерти в 1084 году, но позже он сожалел о поддержке своей кампании по переводу епископства, а сам переехал в аббатство к 1092 году.

Герман был красочным персонажем и театральным проповедником, но в основном он известен как способный ученый, который написал чудеса Святого Эдмунда , агиографический отчет о чудесах, который, как считается, исполнял Эдмунд , король Восточной Англии после его смерти в руках Датской армии викингов в 869 году. Отчет Германа также освещал историю одноименного аббатства. После его смерти были написаны две пересмотренные версии его чудеса , укороченная анонимная работа, которая вырезала историческую информацию, а другая - Госкалином , который был враждебен Герману.

Жизнь

[ редактировать ]Герман описывается историком Томом лицензией как «красочную фигуру». [ 4 ] Его происхождение неизвестно, но, скорее всего, он был немецким . Сходство между его работами и работ Сигеберта из Гемблоу писателя Альперта Мец , оба из которых были в аббатстве Св. Винсента , предполагают , что он был там монахом на период между 1050 и 1070 . Герман, вероятно, родился до 1040 года, так как около 1070 и 1084 года он занимал важный секретарский пост в семье Херста , епископа Восточной Англии , и Герман был бы слишком молод для поса, если бы он родился позже. [ 5 ] По данным архивариуса в четырнадцатом веке и предыдущей аббатства Берри-Сент-Эдмундс Херста , Генри де Киркенде, Герман был архидиаконом , пост, который был административным в ближайшем периоде после заключения. [ 6 ]

Вскоре после его назначения епископа в 1070 году Херста вступил в конфликт с Болдуином , аббатом Аббатства Бери Святого Эдмундса, из -за своей попытки, с секретарской помощью Германа, перенести свой епископство в аббатство. [ 7 ] Херста Свиде была расположена в Северном Элмхэме, когда он был назначен, и в 1072 году он перенес его в Тетфорд , но у обоих минстеров был доход, который был крайне неадекватен для имущества епископа, и Бери обеспечит гораздо лучшую базу операций. [8] Lanfranc, the Archbishop of Canterbury, sent an angry letter to Herfast, demanding that he submit the dispute to Lanfranc's archiepiscopal court and concluding by requiring that Herfast "banish the monk Herman, whose life is notorious for its many faults, from your society and your household completely. It is my wish that he live according to a rule in an observant monastery, or – if he refuses to do this – that he depart from the kingdom of England." Lanfranc's informant was a clerk of Baldwin, who may have had a grudge against Herfast.[9] In spite of Lanfranc's demand for his expulsion, Herman remained with Herfast. In 1071, Baldwin went to Rome and secured a papal immunity for the abbey from episcopal control and from conversion into a bishop's see.[7] Baldwin was a physician to Edward the Confessor and William the Conqueror, and when Herfast almost lost his sight in a riding accident, Herman persuaded him to seek Baldwin's medical help and end their dispute, but Herfast later renewed his campaign, finally losing by a judgement of the king's court in 1081.[10]

Herman later regretted supporting Herfast in the dispute, and looking back on it he wrote:

- Nor will I omit to mention – now that the blush of shame is wiped away – that I frequently gave ear to the bishop in this matter; that, when he sent across the sea to the king already mentioned [William the Conqueror], seeking to establish his see at the abbey, I drafted the letters and wrote up those that were drafted. I also read the responses that he received.[11]

Herman stayed with Herfast until his death in 1084, but it is not clear whether he served the succeeding bishop, William de Beaufeu, and by 1092 he was a monk at Bury St Edmunds Abbey. He occupied senior roles there, probably precentor, and perhaps from about 1095 the position of prior or sub-prior.[12] The abbey's most important relics were the bloodstained undergarments of the saint it was named after, Edmund the Martyr, and Herman was an enthusiastic preacher who enjoyed displaying the relics to the common people. According to an account by a writer who was hostile to him, his disrespectful treatment of the undergarments on one occasion, in taking them out of their box and allowing people to kiss them for two pence, was punished by his death soon afterwards.[13] He probably died in June 1097 or 1098.[14]

Miracles of St Edmund

[edit]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records the defeat of the Kingdom of East Anglia and killing of King Edmund (the Martyr) by a Viking army in 869, but almost nothing survives giving information about his life and reign apart from some coins in his name. Between about 890 and 910 the Danish rulers of East Anglia, who had recently converted to Christianity, issued a coinage commemorating Edmund as a saint, and in the early tenth century his remains were translated to what was to become Bury St Edmunds Abbey.[15] The first known hagiography of Edmund was Abbo of Fleury's Life of St Edmund in the late tenth century and the second was by Herman.[16][a] Edmund was a patron saint of the English people and kings, and a popular saint in the Middle Ages.[18]

Herman's historical significance in the view of historians lies in the Miracles of St Edmund (Latin: De Miraculis Sancti Edmundi), his hagiography of King Edmund.[19] His ultimate aim in this work, according to Licence, "was to validate belief in the power of God and St Edmund",[20] but it was also a work of history, using the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to provide a basic structure and covering not only Edmund's miracles but also the history of the abbey and good deeds of kings and bishops.[21] The Miracles was intended for an erudite audience with an advanced knowledge of Latin.[22] Like other writers of his time, he collected rare words, but his choice of vocabulary was unique. Licence comments that he employed "a convoluted style and recherché vocabulary, which included Grecisms, archaisms and neologisms ... Herman's penchant for odd vernacular proverbs, dark humour and comically paradoxical metaphors such as 'the anchor of disbelief', 'the knot of slackness', 'the burden of laziness', and 'trusting to injustice' is evident throughout his work."[23] His style was "mannerist", in the sense of "that tendency or approach in which the author says things 'not normally, but abnormally', to surprise, astonish, and dazzle the audience".[24] His writing was influenced by Christian and classical sources and he could translate a vernacular text into accurate and poetic Latin: Licence observes that "his inner Ciceronian was at peace with his inner Christian".[25] Summarising the Miracles, Licence says:

Herman's work was exceptional for its day in its historical vision and breadth. The product of a writer schooled at an abbey with an unusually strong interest in historical writing, it was no mere saint's Life or miracle collection ... Nor were its horizons limited like those of local institutional histories ... Although closer to their genre of composition, Herman's piece was developing into something bigger. The catalyst in this experiment was his desire to reinterpret St Edmund as the deputy of God interested in English affairs ... Herman's achievement was to create a seamless narrative of English history without annalistic entries, a feat that neither Byrhtferth of Ramsey at the turn of the eleventh century nor John of Worcester early in the twelfth undertook. Bede had accomplished it, and so would William of Malmesbury on a far more impressive scale in the 1120s.[26]

Herman may have written the first half, covering the period up to the Conquest, around 1070, but it is more likely that the whole work was written in the reign of King William II (1087–1100).[27] Herman's original text in his own hand does not survive, but a shorter version[b] forms part of a book which covers the official biography of the abbey's patron saint. As Herman clearly intended, the book is composed of Abbo's Life followed by the Miracles. It is a luxury product dating to around 1100.[29] This version has some blank spaces and the final miracle stops in the middle of a sentence, indicating that the copying ceased abruptly. A manuscript dating to 1377 includes seven miracles assigned by the scribe to Herman which are not in the Miracles, and they are probably the stories which were intended for the blank spaces.[30][c] Two copies survive of a version produced shortly after Herman's death which leaves out the historical sections and only includes the miracles.[32][d]

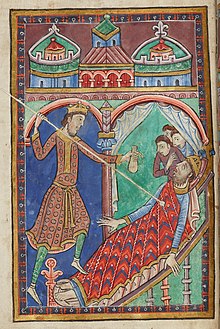

Another revised version of the Miracles (illustrated above) was written around 1100 and survives in a manuscript dating to the 1120s or 1130s.[34][e] It is attributed by Licence to the hagiographer and musician Goscelin, who is not recorded after 1106.[35] Herbert de Losinga, who was Bishop of East Anglia from 1091 to 1119, renewed Herfast's campaign to bring St Edmunds under episcopal control, against the opposition of Baldwin and his supporters, including Herman. The dispute continued after the deaths of Baldwin and Herman in the late 1090s, but like Herfast, Herbert was ultimately unsuccessful. Baldwin's death was followed by a battle over the appointment of a new abbot. Goscelin's text attacks Herbert's enemies, including Herman, and emphasises the role of bishops in Bury's history. The version was probably commissioned by Herbert.[36]

Herbert had bought the bishopric of East Anglia for himself, and the abbacy of New Minster, Winchester, for his father, from William II, and the father and son were attacked in an anonymous satire in fifty hexameters, On the Heresy Simony. Licence argues that Herman, who compared Herbert to Satan in the Miracles, was the author of the satire.[37]

The three versions of the Miracles, together with the additional seven miracles and On the Heresy Simony, are printed and translated by Licence.[38]

Controversy over authorship

[edit]The historian Antonia Gransden described the writer of the Miracles as "a conscientious historian, highly educated, and a gifted Latinist",[39] but she questioned Herman's authorship in a journal article in 1995 and her Oxford Dictionary of National Biography article about Herman in 2004.[40] She stated that the earliest attribution of authorship to Herman is by Henry de Kirkestede in about 1370, and that there is no record of an archdeacon called Herman in the records of Norwich Cathedral, nor can the hagiographer be identified as a monk at St Edmunds Abbey. She thought that the author was probably a hagiographer praised by Goscelin called Bertrann, and de Kirkestede may have misread Bertrann for Hermann (her spelling).[39] Gransden's arguments are dismissed by Licence, who points out that the author of the Miracles confirmed his name by describing a monk called Herman of Binham as his namesake.[41]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Herman claimed to have found another early account of St Edmund's miracles, but he may have just have been following a standard practice of hagiographers of giving their works the authority of tradition by claiming to be following an ancient text.[17]

- ^ London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius B. ii, fos. 20r–85v[28]

- ^ Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley, 240, fos. 623–677[31]

- ^ Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Latin 2621, fos. 84r–92v and Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Digby 39, fos. 24r–39v.[32] In Licence's view, both this version and the one in the official biography must derive from a lost intermediate text, because they have illiterate errors in common which would not have been made by Herman himself.[33]

- ^ New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS M. 736, fos. 23r–76r[33]

References

[edit]- ^ Life and Miracles, Morgan Library, MS M.736 fol. 21v; Licence 2014, p. 153.

- ^ Gransden 1995, p. 1.

- ^ Williams 2004.

- ^ Licence 2009, p. 516.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. xxxii, xxxv–xliv.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. xlvii–xlix.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Licence 2014, p. xxxiii.

- ^ Gransden 1995, p. 14; Licence 2014, pp. xv n. 9, xxxiii.

- ^ Licence 2009, p. 520; Licence 2014, p. xxxvi.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. xxxi–xxxiv, xlvi–xlvii.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. xxxvi.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. xlix–li.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. li–liv, 289, 295.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. cx.

- ^ Mostert 2014, p. 165.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. liv–lv; Winterbottom 1972.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. lv.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. xxxv; Farmer 2011, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. lxiii–lxiv; Hunt 1891, p. 249.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. lx–lxi.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. lxi–lxii, lxix.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. lxi.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. lxviii.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. lxxxiii.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. lxxix–lxxxi.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. lxiii–lxiv.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. liv–lix.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. xci.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. lxi, xci.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. 337–349.

- ^ Licence 2014, p. 337.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Licence 2014, p. xcii.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Licence 2014, p. xciv.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. cix, cxiv.

- ^ Licence 2014, pp. cxiv–cxxix.

- ^ Лицензия 2014 , стр. 102, 111-114; Harper-Bill 2004 .

- ^ Лицензия 2014 , с. XCVI - CIX, 115, 351–355; Harper-Bill 2004 .

- ^ Лицензия 2014 , с. 1–355.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Грансден 2004 .

- ^ Грансден 1995 ; Грансден 2004 .

- ^ Лицензия 2009 , с. 517–518; Лицензия 2014 , с. 99

Библиография

[ редактировать ]- Фермер, Дэвид (2011). Оксфордский словарь святых (5 -е пересмотренное изд.). Оксфорд, Великобритания: издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-959660-7 .

- Грансден, Антония (1995). «Композиция и авторство De Miraculis Sancti Edmundi : приписывается Герману архидиакону». Журнал средневековой латыни . 5 : 1–52. doi : 10.1484/j.jml.2.304037 . ISSN 0778-9750 .

- Грансден, Антония (2004). «Германн (фл. 1070–1100)» . Оксфордский словарь национальной биографии . Издательство Оксфордского университета. doi : 10.1093/ref: ODNB/13083 . ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 1 мая 2022 года . Получено 28 апреля 2022 года . ( требуется членство в публичной библиотеке в Великобритании )

- Харпер-Билл, Кристофер (2004). «Потеря, Герберт де (ум. 1119)» . Оксфордский словарь национальной биографии . Издательство Оксфордского университета. doi : 10.1093/ref: ODNB/17025 . ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8 Полем ( требуется членство в публичной библиотеке в Великобритании )

- Охота, Уильям (1891). «Германн (фл. 1070)» . Словарь национальной биографии . Тол. 26. Оксфорд, Великобритания: издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 249. OCLC 13955143 .

- Лицензия, Том (июнь 2009 г.). «История и агиография в конце одиннадцатого века: жизнь и работа Германа Архидиакона, монаха Бери Сент -Эдмундс». Английский исторический обзор . 124 (508): 516–544. doi : 10.1093/ehr/cep145 . ISSN 0013-8266 .

- Лицензия, Том, изд. (2014). Герман Архидиакон и Госелин из Сен-Бертина: чудеса Святого Эдмунда (на латинском и английском языке). Оксфорд, Великобритания: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968919-4 .

- «Жизнь и чудеса Святого Эдмунда» . Нью -Йорк: Библиотека и музей Моргана. 22 апреля 2016 года. 21В Архивировано из оригинала 11 декабря 2021 года . Получено 1 мая 2022 года .

- Мостерт, Марко (2014). «Эдмунд, Сент, король Восточной Англии». В Лапидже, Майкл; Блэр, Джон; Кейнс, Саймон; Скрагг, Дональд (ред.). Энциклопедия Wiley Blackwell Англосаксонской Англии (2-е изд.). Чичестер, Западный Суссекс: Уайли Блэквелл. С. 165–166. ISBN 978-0-470-65632-7 .

- Уильямс, Энн (2004). «Идред [Эдред] (ум. 955)» . Оксфордский словарь национальной биографии . Издательство Оксфордского университета. doi : 10.1093/ref: ODNB/8510 . ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 8 сентября 2021 года . Получено 8 сентября 2021 года . ( требуется членство в публичной библиотеке в Великобритании )

- Winterbottom, Michael , ed. (1972). «Аббо: жизнь Святого Эдмунда». Три жизни английских святых (на латыни). Торонто, Канада: Папский институт средневековых исследований Центра средневековых исследований. С. 65–89. ISBN 978-0-88844-450-9 .