Эдвард Крейц

Эдвард Крейц | |

|---|---|

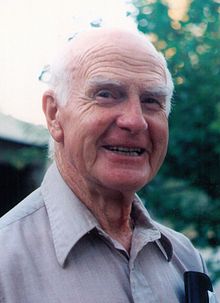

Крейц в дальнейшей жизни | |

| Рожденный | 23 января 1913 г. |

| Умер | 27 июня 2009 г. (96 лет) |

| Гражданство | Американский |

| Альма-матер | Университет Висконсина-Мэдисона (BS 1936, доктор философии 1939) |

| Научная карьера | |

| Поля | Ядерная физика |

| Учреждения | Металлургическая лаборатория Лос-Аламосская лаборатория Технологический институт Карнеги Дженерал Атомикс |

| Диссертация | Резонансное рассеяние протонов литием (1939 г.) |

| Докторантура | Грегори Броуд |

Эдвард Крейц (23 января 1913 — 27 июня 2009) — американский физик, работавший над Манхэттенским проектом в Металлургической лаборатории и Лос-Аламосской лаборатории во время Второй мировой войны . После войны он стал профессором физики в Технологическом институте Карнеги . Он был вице-президентом по исследованиям в General Atomics с 1955 по 1970 год. Он опубликовал более 65 статей по ботанике , физике , математике , металлургии и научной политике, а также получил 18 патентов, касающихся ядерной энергии .

Выпускник Университета Висконсин-Мэдисон , Крейц помог Принстонскому университету построить свой первый циклотрон . Во время Второй мировой войны он работал над ядерного реактора проектированием под руководством Юджина Вигнера в Металлургической лаборатории, разрабатывая систему охлаждения для первых реакторов с водяным охлаждением. Он возглавлял группу, изучавшую металлургию урана и других элементов, используемых в конструкциях реакторов. В октябре 1944 года он переехал в Лос-Аламосскую лабораторию, где стал руководителем группы.

После окончания войны Крейц принял предложение переехать в Технологический институт Карнеги, где в 1948 году он стал главой физического факультета и центра ядерных исследований. В 1955 году он вернулся в Лос-Аламос, чтобы оценить программу термоядерного синтеза для будущего. Комиссия по атомной энергии . Там он принял предложение стать вице-президентом по исследованиям и разработкам и директором Лаборатории чистой и прикладной науки Джона Джея Хопкинса в General Atomics. Под его руководством General Atomics разработала TRIGA — ядерный реактор для университетов и лабораторий.

Крейц работал помощником директора Национального научного фонда с 1970 по 1977 год, а затем директором Музея епископа Бернис Пауахи в Гонолулу , где он проявил особый интерес к подготовке музея «Руководства по цветущим растениям Гавайев» .

Ранний период жизни

[ редактировать ]Крейц родился 23 января 1913 года в Бивер-Дэм, штат Висконсин , в семье Лестера Крейца, учителя истории средней школы, и Грейс Смит Крейц, учительницы общих естественных наук. У него было два старших брата, Джон и Джим, и младшая сестра Эдит. [1] Семья переехала в О-Клер, штат Висконсин , в 1916 году, в Монро, штат Висконсин , в 1920 году и в Джейнсвилл, штат Висконсин , в 1927 году. [2] Он играл на многих музыкальных инструментах, включая мандолину , гавайскую гитару и тромбон . [1] Он играл в школьных оркестрах средней школы Джейнсвилля и средней школы Монро . В Джейнсвилле он играл на тенор-банджо в танцевальном оркестре Rosie's Ragadors и на литаврах в школьном оркестре Монро. Он также играл левого защитника в командах по американскому футболу в Джейнсвилле и Монро. Он проявил интерес к химии, биологии, геологии и фотографии. [2]

После окончания средней школы Джейнсвилля в 1929 году он устроился на работу бухгалтером в местный банк. В 1932 году его брат Джон, окончивший Университет Висконсин-Мэдисон по специальности инженер-электрик, убедил его тоже поступить в колледж. Джон предложил: «Если вы не уверены, какая часть науки вам нужна, выберите физику, потому что она является основой для всех». [3] Позже Крейц вспоминал, что это был лучший совет, который он когда-либо получал. [3] Он поступил в Университет Висконсина и изучал математику и физику. [1] Денег было мало во время Великой депрессии , особенно после того, как его отец умер в 1935 году. Чтобы оплатить свои счета, Крейц работал посудомойкой и поваром быстрого приготовления, а также устроился на работу по уходу за оборудованием физической лаборатории. В 1936 году, на последнем курсе , он преподавал лабораторные занятия по физике. [2]

Крейц встретился с несколькими преподавателями Университета Висконсина, включая Джулиана Мака, Рагнара Роллефсона, Раймонда Херба , Юджина Вигнера и Грегори Брейта . Мак поручил Крейцу выполнить исследовательский проект на первом курсе . [1] Крейц остался в Висконсине в качестве аспиранта после получения степени бакалавра наук (BS) в 1936 году, работая на Херба над модернизацией ведомственного генератора Ван де Граафа с 300 до 600 кэВ . высокоэнергетических гамма-лучей Когда это было сделано, встал вопрос, что с этим делать, и Брейт предположил, что ранее наблюдалось образование , когда литий бомбардировали протонами с энергией 440 кэВ. [1] Поэтому Крейц в 1939 году написал свою докторскую диссертацию (Ph.D.) по резонансному рассеянию протонов литием . [4] [5] под руководством Брейта. [2] 13 сентября 1937 года Крейц женился на Леле Роллефсон, студентке-математике из Висконсина и сестре Рагнара Роллефсона. У пары было трое детей, два сына, Майкл и Карл, и дочь Энн Джо. [1]

Вигнер переехал в Принстонский университет в 1938 году, и вскоре после этого Кройц тоже получил предложение. подарил Принстону 36-дюймовый (910 мм) магнит Калифорнийский университет , который использовался для создания циклотрона на 8 МэВ . Они хотели, чтобы Кройц помог ввести его в эксплуатацию. [1] Позже он вспоминал:

На третий день моего пребывания в Принстоне меня пригласили сделать краткий отчет о моей дипломной работе. На собраниях «Журнального клуба» обычно выступало два или три докладчика. На этот раз спикерами были Нильс Бор , Альберт Эйнштейн и Эд Крейц. Быть в одной программе с этими двумя гигантами научных достижений было захватывающим дух. Незадолго до начала встречи мой спонсор Дельсассо спросил меня: «Скажи, Крейц, ты уже встречался с Эйнштейном?» Я этого не сделал. Дельсассо отвел меня туда, где сидел Эйнштейн в толстовке и теннисных туфлях, и сказал: «Профессор Эйнштейн, это Крейц, который пришел работать над нашим циклотроном». Великий человек протянул руку, большую, как тарелка, и сказал с акцентом: «Я рад познакомиться с вами, доктор Крейц». Мне удалось прохрипеть: «Я тоже рад познакомиться с вами, доктор Эйнштейн». [2]

Но именно Бор взволновал публику своими новостями из Европы об открытии Лизой Мейтнер и Отто Фришем ядерного деления . [1] Физики поспешили подтвердить результаты. Крейц построил ионизационную камеру и линейный усилитель из радиовакуумных ламп , банок из-под кофе и мотоциклетных аккумуляторов, и с помощью этого аппарата физики из Принстона смогли подтвердить результаты. [2]

Вторая мировая война

[ редактировать ]В первые годы Второй мировой войны, с 1939 по 1941 год, Вигнер руководил группой из Принстона в серии экспериментов с использованием урана и двух тонн графита в качестве замедлителя нейтронов . [2] В начале 1942 года Артур Комптон сосредоточил Манхэттенского проекта различные группы , работавшие над проектированием плутония и ядерного реактора , включая команду Вигнера из Принстона, в Металлургической лаборатории университета Чикагского . [6] Это имя было кодовым; Крейц был первым, кто провел настоящие исследования в области металлургии , и он нанял для работы с ним первого металлурга. [3]

Wigner led the Theoretical Group that included Creutz, Leo Ohlinger, Alvin M. Weinberg, Katharine Way and Gale Young. The group's task was to design the reactors that would convert uranium into plutonium. At the time, reactors existed only on paper, and no reactor had yet gone critical. In July 1942, Wigner chose a conservative 100 MW design, with a graphite neutron moderator and water cooling.[7] The choice of water as a coolant was controversial at the time because water was known to absorb neutrons, thereby reducing the efficiency of the reactor; but Wigner was confident that his group's calculations were correct and that water would work, while the technical difficulties involved in using helium or liquid metal as a coolant would delay the project.[8] Working seven days a week, the group designed the reactors between September 1942 and January 1943.[9] Creutz studied the corrosion of metals in a water-cooled system,[1] and designed the cooling system.[9] In 1959 a patent for the reactor design would be issued in the name of Creutz, Ohlinger, Weinberg, Wigner, and Young.[1]

As a group leader at the Metallurgical Laboratory, Creutz conducted studies of uranium and how it could be extruded into rods. His group looked into the process of corrosion in metals in contact with fast-flowing liquids, the processes for fabricating aluminium and jacketing uranium with it. It also investigated the forging of beryllium, and the preparation of thorium.[1][10] Frederick Seitz and Alvin Weinberg later reckoned that the activities of Creutz and his group may have reduced the time taken to produce plutonium by up to two years.[1]

The discovery of spontaneous fission in reactor-bred plutonium due to contamination by plutonium-240 led Wigner to propose switching to breeding uranium-233 from thorium, but the challenge was met by the Los Alamos Laboratory developing an implosion-type nuclear weapon design.[11] In October 1944, Creutz moved to Los Alamos,[10] where he became a group leader responsible for explosive lens design verification and preliminary testing.[1] Difficulties encountered in testing the lenses led to the construction of a special test area in Pajarito Canyon, and Creutz became responsible for testing there.[12] As part of the preparation for the Trinity nuclear test, Creutz conducted a test detonation at Pajarito Canyon without nuclear material.[13] This test brought bad news; it seemed to indicate that the Trinity test would fail. Hans Bethe worked through the night to assess the results, and was able to report that the results were consistent with a perfect explosion.[14]

Later life

[edit]

After the war ended in 1945, Creutz accepted an offer from Seitz to come to the Carnegie Institute of Technology as an associate professor, and help create a nuclear physics group there.[2] Creutz in turn recruited a number of young physicists who had worked with him at Princeton and on the Manhattan Project in Chicago and Los Alamos, including Martyn Foss, Jack Fox, Roger Sutton and Sergio DeBenedetti. Together, with funding from the Office of Naval Research they built a 450 MeV synchrotron at the Nuclear Research Center near Saxonburg, Pennsylvania.[1] For a time, This put them at the forefront of research into nuclear physics, allowing physicists there to study the recently discovered pi meson and mu meson.[3] A visiting scholar, Gilberto Bernardini, created the first photographic emulsion of a meson.[1]

Creutz became a professor, the head of the physics department, and the head of the nuclear research center at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in 1948. He was also a member of the executive board at the Argonne National Laboratory from 1946 to 1958, and a consultant at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory from 1946 to 1958.[15] In addition to his work on nuclear physics, he cultivated flowers and orchids at his home. He published eight papers on floral species, and named three varieties of violets after his children. One 1966 paper, published in the New York Botanical Garden Journal was on Apetahia raiateensis, a rare flower found only on the island of Raiatea in French Polynesia.[1] He travelled to Polynesia many times, and translated Grammar of the Tahitian language from French into English.[1] His family served as hosts for a time to two young people from Tahiti and Samoa.[2]

In 1955 and 1956, Creutz spent a year at Los Alamos evaluating its thermonuclear fusion program for the Atomic Energy Commission. While there he was approached by Frederic de Hoffmann, who recruited him to join the General Atomics division of General Dynamics. He moved to La Jolla, California, as its vice president for research and development,[1][2] and was concurrently the director of its John Jay Hopkins Laboratory for Pure and Applied Science from 1955 to 1967. He was also a member of the Advisory Panel on General Science at the Department of Defense from 1959 to 1963.[15]

Under his leadership, General Atomics developed TRIGA, a small reactor for universities and laboratories. TRIGA used uranium zirconium hydride (UZrH) fuel, which has a large, prompt negative fuel temperature coefficient of reactivity. As the temperature of the core increases, the reactivity rapidly decreases. It is thus highly unlikely, though not completely impossible, for a nuclear meltdown to occur. Due to its safety and reliability, which allows it to be installed in densely populated areas, and its ability to still generate high energy for brief periods, which is particularly useful for research, it became the world's most popular research reactor, and General Atomics sold 66 TRIGAs in 24 countries.[16] The high-temperature gas-cooled reactor (HTGR) was less successful, and only two HTGR power reactors were built, both in the United States. A 40 MW demonstration unit at the Peach Bottom Nuclear Generating Station in Pennsylvania operated successfully, but a larger 300 MW unit at the Fort St. Vrain Generating Station in Colorado encountered technical problems.[1] General Atomics also conducted research into thermonuclear energy, including means of magnetically confining plasma. Between 1962 and 1974 Creutz published six papers on the subject.[1]

In 1970 President Richard Nixon appointed Creutz as assistant director for research of the National Science Foundation. He became assistant director for mathematical and physicals sciences in 1975, and was acting deputy director from 1976 to 1977. The 1970s energy crisis raised the national profile of energy issues, and Creutz served on a panel that produced a study called The Nation's Energy Future.[1] His wife Lela died of cancer in 1972. In 1974 he married Elisabeth Cordle, who worked for the National Science Board. The two of them enjoyed locating and photographing rare orchids.[2][17]

His appointment at the National Science Foundation ended in 1977, and Creutz became director of the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum in Honolulu. He took particular interest in the museum's work preparing a two-volume Manual of the Flowering Plants of Hawaii, which was published in 1999. He expanded programs for education and outreach, and secured funding for two new buildings.[1] He retired in 1987 and returned to his home in Rancho Santa Fe, California,[2] and died there on June 27, 2009.[1][17]

Media appearances

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Hinman, George; Rose, David (2010). Edward Chester Creutz 1913–2009 (PDF). Biographical Memoirs. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Creutz, Edward (January 23, 1996). "Obituary" (PDF). Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Oral History Transcript — Dr. Edward Creutz". American Institute of Physics. January 9, 2006. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ^ Creutz, Edward (May 1939). "Resonance Scattering of Protons by Lithium". Physical Review. 55 (9): 819–824. Bibcode:1939PhRv...55..819C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.55.819.

- ^ Raman & Panarella 2009, p. 353.

- ^ Weinberg 1994, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Szanton 1992, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Weinberg 1994, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Alvin M. Weinberg's Interview". Manhattan Project Voices. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 471.

- ^ Weinberg 1994, pp. 36–38.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 273.

- ^ Rhodes 1986, p. 657.

- ^ Rhodes 1986, pp. 661–663.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Edward Creutz". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ^ "TRIGA® Nuclear Reactors". General Atomics. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gonzalez, Blanca (July 13, 2009). "Edward Creutz; worked on Manhattan Project". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- ^ https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1039992 [user-generated source]

References

[edit]- Creutz, Edward (July–August 1966). "The Tiare Apetahi of Raiatea". The Garden Journal. 16 (4): 142. ISSN 0016-4585. OCLC 1570422.

- Hoddeson, Lillian; Henriksen, Paul W.; Meade, Roger A.; Westfall, Catherine L. (1993). Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943–1945. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44132-3. OCLC 26764320.

- Raman, Roger; Panarella, E. (2009). Current Trends in International Fusion Research: Proceedings of the Sixth Symposium. Ottawa: NRC Research Press. ISBN 978-0-660-19890-3.

- Rhodes, Richard (1986). The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-44133-7. OCLC 13793436.

- Szanton, Andrew (1992). The Recollections of Eugene P. Wigner. Plenum. ISBN 0-306-44326-0.

- Weinberg, Alvin (1994). The First Nuclear Era: The Life and Times of a Technological Fixer. New York: AIP Press. ISBN 1-56396-358-2.

Внешние ссылки

[ редактировать ]- Стенограмма устного исторического интервью с Эдвардом Крейцем 9 января 2006 г., Американский институт физики, Библиотека и архив Нильса Бора - Сессия I

- Стенограмма устного исторического интервью с Эдвардом Крейцем 10 января 2006 г., Американский институт физики, Библиотека и архив Нильса Бора - Сессия II

- 1913 рождений

- смертей в 2009 г.

- Люди из Монро, Висконсин

- Люди из Джейнсвилля, Висконсин

- Люди из Бивер-Дэм, штат Висконсин

- Американские физики XX века

- Выпускники Университета Висконсин-Мэдисон

- Преподаватели Университета Карнеги-Меллон

- Люди Манхэттенского проекта

- Члены Американского физического общества

- Выпускники средней школы Джозефа А. Крейга