Самнитские войны

| Самнитские войны | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Римская экспансия в Италии с 500 до н.э. до 218 г. до н.э. через латинскую войну (светло -красный), Самнитские войны (розовый/оранжевый), пиррическая война (бежевая) и первая и вторая Пуническая война (желтая и зеленая). Цизальпийская Галлия (238-146 гг. До н.э.) и альпийские долины (16-7 до н.э.) были добавлены позже. Римская Республика в 500 г. до н.э. отмечена темно -красным | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Roman Republic Latin allies Campanians |

Samnites Aequi some Hernici Etruscans Umbrians Senone Gauls some northern Apulian towns | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Quintus Fabius Maximus Rullianus Quintus Aulius Cerretanus | Gellius Egnatius † | ||||||

Первые вторые , третьи и Самнитские войны (343–341 гг. До н.э., 326–304 г. до н.э. и 298–290 г. до н.э.), сражались между Римской Республикой и Самнитами , которые жили на участке Апеннинских гор к югу от Рима и севера Луканского племени .

- этих войн была результатом вмешательства Рима в спасение кампании Капуа Первая из от атаки Самнита.

- Второй был результатом вмешательства Рима в политику города Неаполь и превратился в соревнование по контролю над Центральной и южной Италией .

- Точно так же третья война также включала борьбу за контроль над этой частью Италии.

The wars extended over half a century, and also drew in the peoples to the east, north, and west of Samnium (land of the Samnites) as well as those of central Italy north of Rome (the Etruscans, Umbri, and Picentes) and the Senone Gauls, but at different times and levels of involvement.

Background

[edit]By the time of the First Samnite War (343 BC), the southward expansion of Rome's territory had reached the River Liris (see Liri), which was the boundary between Latium (land of the Latins) and Campania. This river is now called Garigliano and it is the boundary between the modern regions of Lazio and Campania. In those days the name Campania referred to the plain between the coast and the Apennine Mountains which stretched from the River Liris down to the bays of Naples and Salerno. The northern part of this area was inhabited by the Sidicini, the Aurunci, and the Ausoni (a subgroup of the Aurunci). The central and southern part was inhabited by the Campanians, who were people who had migrated from Samnium (land of the Samnites) and were closely related to the Samnites, but had developed a distinctive identity. The Samnites were a confederation of four tribes who lived in the mountains to the east of Campania and were the most powerful people in the area. The Samnites, Campanians, and Sidicini spoke Oscan languages. Their languages were part of the Osco-Umbrian linguistic family, which also included Umbrian and the Sabellian languages to the north of Samnium. The Lucanians who lived to the south were also Oscan speakers.

Diodorus Siculus and Livy report that in 354 BC Rome and the Samnites concluded a treaty,[1][2] but neither lists the terms agreed upon. Modern historians have proposed that the treaty established the river Liris as the boundary between their spheres of influence, with Rome's lying to its north and the Samnites' to its south. This arrangement broke down when the Romans intervened south of the Liris to rescue the Campanian city of Capua (just north of Naples) from an attack by the Samnites.

First Samnite War (343 to 341 BC)

[edit]Livy is the only preserved source to give a continuous account of the war which has become known in modern historiography as the First Samnite War. In addition, the Fasti Triumphales records two Roman triumphs dating to this war and some of the events described by Livy are also mentioned by other ancient writers.

Outbreak

[edit]Livy's account

[edit]According to Livy, the First Samnite War started not because of any enmity between Rome and the Samnites, but due to outside events.[3] The spark came when the Samnites without provocation attacked the Sidicini,[4] a tribe living north of Campania with their chief settlement at Teanum Sidicinum.[5] Unable to stand against the Samnites, the Sidicini sought help from the Campanians.[4] However, Livy continues, the Samnites defeated the Campanians in a battle in Sidicine territory and then turned their attention toward Campania. First they seized the Tifata hills overlooking Capua (the main Campanian city) and, having left a strong force to hold them, marched into the plain between the hills and Capua.[6] There they defeated the Campanians in a second battle and drove them within their walls. This compelled the Campanians to ask Rome for help.[7]

In Rome, the Campanian ambassadors were admitted to an audience with the Senate. In a speech, they proposed an alliance between Rome and the Campanians, noting how the Campanians with their famous wealth could be of aid to the Romans, and that they could help to subdue the Volsci, who were enemies of Rome. They pointed out that nothing in Rome's treaty with the Samnites prevented them from also making a treaty with the Campanians, and warning that if they did not, the Samnites would conquer Campania and its strength would be added to the Samnites' instead of the Romans'.[8] After discussing this proposal, the Senate concluded that while there was much to be gained from a treaty with the Campanians, and that this fertile area could become Rome's granary, Rome could not ally with them and still be considered loyal to their existing treaty with the Samnites: for this reason they had to refuse the proposal.[9] After being informed of Rome's refusal, the Campanian embassy, in accordance with their instructions, surrendered the people of Campania and the city of Capua unconditionally into the power of Rome.[10] Moved by this surrender, the Senators resolved that Rome's honour now required that the Campanians and Capua, who by their surrender had become the possession of Rome, be protected from Samnite attacks.[11]

Envoys were sent to the Samnites with the instructions to request that they, in view of their mutual friendship with Rome, spare territory which had become the possession of Rome and to warn them to keep their hands off the city of Capua and the territory of Campania.[12] The envoys delivered their message as instructed to the Samnites' national assembly. However, they were met with a defiant response, "not only did the Samnites declare their intention of waging war against Capua, but their magistrates left the council chamber, and in tones loud enough for the envoys to hear, ordered [their armies] to march out at once into Campanian territory and ravage it."[13] When this news reached Rome, the fetials were sent to demand redress, and when this was refused Rome declared war against the Samnites.[14]

Modern views

[edit]The historical accuracy of Livy's account is disputed among modern historians. They are willing to accept that while Livy might have simplified the way in which the Sidicini, Campani and Samnites came to be at war, his narrative here, at least in outline, is historical.[15][16][17][18] The Sidicini's stronghold at Teanum controlled an important regional crossroads, which would have provided the Samnites with a motive for conquest.[19][5][18] The First Samnite War might have started quite by accident, as Livy claimed. The Sidicini were located on the Samnite side of the river Liris, and while the Roman-Samnite treaty might only have dealt with the middle Liris, not the lower, Rome does not appear to have been overly concerned for the fate of the Sidicini. The Samnites could therefore go to war with Sidicini without fear of Roman involvement. It was only the unforeseen involvement of the Campani that brought in the Romans.[15]

Many historians have however had difficulty accepting the historicity of the Campanian embassy to Rome, in particular whether Livy was correct in describing the Campani as surrendering themselves unconditionally into Roman possession.[20][16][17] That Capua and Rome were allied in 343 is less controversial, as such a relationship underpins the whole First Samnite War.[21]

Historians have noted the similarities between the events leading to the First Samnite War and events, which according to Thucydides, caused the Peloponnesian War,[22] but there are differences as well.[23] It is clear that Livy, or his sources, has consciously modelled the Campanian embassy after the "Corcyrean debate" in Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War.[17][24] There are many parallels between the speech given by the Campanian ambassador to the Roman senate in Livy and the speech of the Corcyrean ambassador to the Athenian assembly in Thucydides. But while Thucydides' Athenians debate the Corcyreans' proposal in pragmatic terms, Livy's senators decide to reject the Campanian alliance based on moral arguments.[17][24] Livy might have intended his literary educated readers to pick up this contrast.[17] The exaggerated misery of the surrendering Campani contrast with the Campanian arrogance, a stock motif in ancient Roman literature.[25] It is also unlikely that Livy's description of the Samnite national assembly is based on any authentic sources.[26] However, it does not necessarily follow that because the speeches are invented, a standard feature for ancient historians, the Campanian surrender must be invented as well.[21]

The chief difficulty lies in how, in 343, rich Capua could have been reduced to such dire straits by the Samnites that the Campani were willing to surrender everything to Rome.[21] During the Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC), Capua famously sided with Carthage, but after a lengthy siege by Rome, she had to surrender unconditionally in 211 BC, after which the Capuans were harshly punished by the Romans. Salmon (1967, p. 197) therefore held that the Campanian surrender in 343 is a retrojection by later Roman historians. This invention would serve the double purpose of exonerating Rome from treaty-breaking in 343 BC and justifying the punishment handed out in 211 BC. What Rome agreed to in 343 was an alliance on terms similar to the treaties she had with the Latins and the Hernici. Cornell (1995, p. 347) accepts the surrender as historical. Studies have shown that voluntary submission was a common feature in the diplomacy of this period. Likewise Oakley (1998, pp. 286–289) does not believe the surrender of 343 BC to be a retrojection, not finding many similarities between the events of 343 and 211. The ancient historians record many later instances, whose historicity are not doubted, where a state appealed to Rome for assistance in war against a stronger enemy. The historical evidence shows the Romans considering such supplicants to have technically the same status as surrendered enemies, but in practice, Rome would not want to abuse would-be allies. Forsythe (2005, p. 287), like Salmon, argues that the surrender in 343 is a retrojection of that of 211, invented to better justify Roman actions and for good measure shift the guilt for the First Samnite War onto the manipulative Campani.

Livy portrays the Romans selflessly assuming the burden of defending the Campani, but this is a common theme in Roman republican histories, whose authors wished to show that Rome's wars had been just. Military success was the chief road to prestige and glory among the highly competitive Roman aristocracy. Evidence from later, better documented, time periods shows the Roman Senate quite capable of manipulating diplomatic circumstances so as to provide just causes for expansionary wars. There is no reason to believe this was not also the case in the second half of the 4th century BC.[27] There are also recorded examples of Rome rejecting appeals for help, implying that the Romans in 343 BC had the choice of rejecting the Campani.[5]

Three Roman victories

[edit]

According to Livy, the two Roman consuls for 343 BC, Marcus Valerius Corvus and Aulus Cornelius Cossus, both marched against the Samnites. Valerius led his army into Campania, while Cornelius, into Samnium where he camped at Saticula.[28] Livy then goes on to narrate how Rome won three different battles against the Samnites. After a day of hard fighting, Valerius won the first battle, fought at Mount Gaurus near Cumae, only after a last desperate charge in fading daylight.[29] The second battle almost ended in disaster for the Romans when the Samnites attempted to trap the other consul, Cornelius Cossus, and his army in a mountain pass. Fortunately for them, one of Cornelius' military tribunes, Publius Decius Mus with a small detachment, seized a hilltop, distracting the Samnites and allowing the Roman army to escape the trap. Decius and his men slipped away to safety during the night; the morning after the unprepared Samnites were attacked and defeated.[30] Still determined to seize victory, the Samnites collected their forces and laid siege to Suessula at the eastern edge of Campania. Leaving his baggage behind, Marcus Valerius took his army on forced marches to Suessula. Low on supplies, and underestimating the size of the Roman force, the Samnites scattered their army to forage for food. This gave Valerius the opportunity to win a third Roman victory when he first captured the Samnites' lightly defended camp and then scattered their foragers.[31] These Roman successes against the Samnites convinced Falerii to convert her forty year's truce with Rome into a permanent peace treaty, and the Latins to abandon their planned war against Rome and instead campaign against the Paeligni. The friendly city-state of Carthage sent a congratulatory embassy to Rome with a twenty-five pound crown for the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. Both consuls then celebrated triumphs over the Samnites.[32] The Fasti Triumphales records that Valerius and Cornelius celebrated their triumphs over the Samnites on 21 September and 22 September respectively.[33]

Modern historians have doubted the historical accuracy of Livy's description of these three battles. Livy's battle-scenes for this time period are mostly free reconstructions by him and his sources, and there are no reasons why these should be different.[34] The number of Samnites killed and the amounts of spoils taken by the Romans have clearly been exaggerated.[35] Historians have noted the many similarities between the story of Publius Decius Mus, and an event said to have taken place in Sicily in 258 when the Romans were fighting the First Punic War against Carthage. According to the ancient sources, a Roman army was in danger of being trapped in a defile when a military tribune led a detachment of 300 men to seize a hilltop in the middle of the enemy. The Roman army escaped, but of the 300 only the tribune survived. It is unlikely that this latter, in ancient times more famous, episode has not influenced the descriptions of the former.[36]

Salmon (1967) also found several other similarities between the campaigns of 343 and later events which he considered to be doublets. Both the First and the Second Samnite Wars start with an invasion of Samnium by a Cornelius, the way in which a Roman army was led into a trap resembles the famous disaster at the Caudine Forks in 321 BC, and there are similarities to the campaigns of Publius Cornelius Arvina in 306 BC and Publius Decius Mus (the son of the hero of Saticula) in 297 BC. He also thought Valerius Corvus' two Campanian victories could be doublets of Roman operations against Hannibal in the same area in 215[37] On the other hand, the entries in the Fasti Triumphales supports some measure of Roman success. In Salmon's reconstruction, therefore, there was only one battle in 343 BC, perhaps fought on the outskirts of Capua near the shrine of Juno Gaura, and ending with a narrow Roman victory.[38]

Oakley (1998) dismisses these claims of doublets and inclines towards believing there were three battles. The Samnites would have gained significant ground in Campania by the time the Romans arrived and Valerius' two victories could be the outcome of twin Samnite attacks on Capua and Cumae. And while Samnite ambushes are somewhat of a stock motif in Livy's narrative of the Samnite wars, this might simply reflect the mountainous terrain in which these wars were fought.[39] The story of Decius, as preserved, has been patterned after that of the military tribune of 258, but Decius could still have performed some heroic act in 343, the memory of which became the origin of the later embellished tale.[40]

Forsythe (2005) considers the episode with Cornelius Cossus and Decius Mus to have been invented, in part to foreshadow Decius' sacrifice in 340 BC. P. Decius might have performed some heroic act which then enabled him to become the first of his family to reach the consulship in 340, but if so, no detail of the historical event survives. Instead, later annalists have combined the disaster at the Caudine Forks with the tale of the military tribune of 258 BC to produce the entirely fictitious story recorded by Livy; the difference being that while in the originals the Romans suffered defeat and death, here none of Decius' men are killed and the Romans win a great victory.[41]

End of the war

[edit]No fighting is reported for 342. Instead the sources focus on a mutiny by part of the soldiery. According to the most common variant, following the Roman victories of 343 the Campani asked Rome for winter garrisons to protect them against the Samnites. Subverted by the luxurious lifestyle of the Campani, the garrison soldiers started plotting to seize control and set themselves up as masters of Campania. However the conspiracy was discovered by the consuls of 342 before the coup could be carried out. Afraid of being punished, the plotters mutinied, formed a rebel army and marched against Rome. Marcus Valerius Corvus was nominated dictator to deal with the crisis; he managed to convince the mutineers to lay down their arms without bloodshed and a series of economic, military and political reforms were passed to deal with their grievances.[42] The history of this mutiny is however disputed among modern historians and it is possible that the whole narrative has been invented to provide a background for the important reforms passed that year.[43] These reforms included the Leges Genuciae which stated that no one could be reelected to the same office within less than ten years, and it is clear from the list of consuls that, except in years of great crises, this law was enforced. It also became a firm rule that one of the consuls had to be a plebeian.[44]

Livy writes that in 341 BC one of the Roman consuls, Lucius Aemilius Mamercus, entered Samnite territory but found no army to oppose him. He was ravaging their territory when Samnite envoys came to ask for peace. When presenting their case to the Roman Senate, the Samnite envoys stressed their former treaty with the Romans, which unlike the Campani, they had formed in times of peace, and that the Samnites now intended to go to war against the Sidicini who were no friends of Rome. The Roman praetor, Ti. Aemilius, delivered the reply of the Senate: Rome was willing to renew her former treaty with the Samnites; moreover, Rome would not involve herself in the Samnites' decision to make war or peace with the Sidicini. Once peace had been concluded the Roman army withdrew from Samnium.[45]

The impact of Aemilius' invasion of Samnium may have been exaggerated;[46] it could even have been entirely invented by a later writer to bring the war to an end with Rome in a suitably triumphant fashion.[47] The sparse mentions of praetors in the sources for the 4th century BC are generally thought to be historical; it is possible therefore that as praetor Ti. Aemilius really was involved in the peace negotiations with the Samnites.[46] The First Samnite War ended in a negotiated peace rather than one state dominating the other. The Romans had to accept that the Sidicini belonged to the Samnite sphere, but their alliance with the Campani was a far greater prize. Campania's wealth and manpower were a major addition to Rome's strength.[48]

Historicity of the war

[edit]The many problems with Livy's account and Diodorus' failure to mention it has even caused some historians to reject the entire war as unhistorical. More recent historians have however accepted the basic historicity of the war.[49][16] No Roman historian would have invented a series of events so unflattering to Rome. Livy was clearly embarrassed at the way Rome had turned from being an ally to an enemy of the Samnites.[49][16] It is also unlikely that the Romans could have established such a dominating position in Campania as they had after 341 without Samnite resistance.[50] Finally Diodorus ignores many other events in early Roman history such as all the early years of the Second Samnite War; his omission of the First Samnite War can therefore not be taken as proof of its unhistoricity.[50]

Second (or Great) Samnite War (326 to 304 BC)

[edit]

Outbreak

[edit]The Second Samnite War resulted from tensions which arose from Roman interventions in Campania. The immediate precipitants were the foundation of a Roman colony (settlement) at Fregellae in 328 BC and actions taken by the inhabitants of Paleopolis. Fregellae had been a Volscian town on the eastern branch of the River Liris, at the junction with the River Tresus (today's Sacco) – viz., in Campania and in an area which was to be under Samnite control. It had been taken from the Volsci and destroyed by the Samnites. Paleopolis ("old city") was the older settlement of what is now Naples (which was a Greek city) and was very close to the newer and larger settlement of Neapolis ("new city"). Livy said that it attacked Romans who lived in Campania. Rome asked for redress, but they were rebuffed and war was declared. In 327 BC the two consular armies headed for Campania. The consul Quintus Publilius Philo took on Naples. His colleague Lucius Cornelius Lentulus positioned himself inland to check the movements of the Samnites because of reports that there had been a levy in Samnium that intended to intervene, in anticipation of a rebellion in Campania. Lentulus set up a permanent camp. The nearby Campanian city of Nola sent 2000 troops to Paleopolis/Neapolis and the Samnites sent 4000. In Rome there was also a report that the Samnites were encouraging rebellions in the towns of Privernum Fundi, and Formiae (Volscian towns south of the River Liris). Rome sent envoys to Samnium. The Samnites denied that they were preparing for war, that they had not interfered in Formiae and Fundi, and said that the Samnite men were not sent to Paleopolis by their government. They also complained about the founding of Fregellae, which they thought was as an act of aggression against them, as they had recently overrun that area. They called for war in Campania.[51]

There had been tensions prior to these events. In 337 BC a war broke out between the Aurunci and the Sidicini. The Romans decided to help the Aurunci because they had not fought Rome during the First Samnite War. Meanwhile, the ancient city of Aurunca was destroyed, and so they fled to Suessa Aurunca, which they fortified. In 336 BC the Ausoni joined the Sidicini. The Romans defeated the forces of these two peoples in a minor battle. In 335 BC one of the two Roman consuls besieged, seized and garrisoned Cales, the main town of the Ausoni. The army was then sent to march on the Sidicini so that the other consul could share the glory. In 334 BC, 2500 civilians were sent to Cales to set up a Roman colony there. The Romans ravaged the territory of the Sidicini and there were reports that in Samnium there had been calls for war with Rome for two years. Therefore, the Roman troops were kept in Sidicini territory. There were also tensions north of the River Liris, in the Volscian territory. In 330 BC the Volscian towns of Fabrateria and Luca offered Rome overlordship over them in exchange for protection from the Samnites and the senate sent a warning to the Samnites not to attack their territories. The Samnites agreed. According to Livy this was because they were not ready for war. In the same year the Volscian towns of Privernum and Fundi rebelled and ravaged the territories of another Volscian town and two Roman colonies in the area. When the Romans sent an army Fundi quickly pledged its loyalty. In 329 BC, Privernum either fell or surrendered (this is unclear). Its ringleaders were sent to Rome, its walls were pulled down and a garrison was stationed there.[52]

In Livy's account there is a sense that the peace with the Samnites had been on a thin edge for years. It has also to be noted that Cales was in an important strategic position not only for the route from Rome to Capua but also for some of the routes which gave access to the mountains of Samnium. Yet the Samnites had not responded militarily to Roman interventions in Campania. One factor might have been the conflict between the Lucanians (the Samnites’ southerly neighbours) and the Greek city of Taras (Tarentum in Latin, modern Taranto) on the Ionian Sea. The Tarentines called for the help of the Greek king Alexander of Epirus, who crossed over to Italy in 334 BC. In 332 BC Alexander landed at Paestum, which was close to Samnium and Campania. The Samnites joined the Lucanians and the two were defeated by Alexander, who then established friendly relations with Rome. However, Alexander was killed in battle in 331 or 330 BC.[53][54] The grievance of the Samnites about Fregellae might have been an addition to aggravations caused by Roman policy in Campania in the previous eight years.

From 327 BC to 322 BC

[edit]Quintus Publilius Philo positioned his army between Paleopolis and Neapolis to isolate them from each other. Meanwhile, the Romans introduced an institutional novelty: Publilius Philo and Cornelius Lentulus should have gone back to Rome at the end of their term (to make way for the consuls elected for the next year, who would continue the military operations), instead, their military command (but not their authority as civilian heads of the Republic) was extended until the termination of the campaigns with the title of proconsuls. In 326 BC two leading men of Naples, who were dissatisfied with the misbehaviour of the Samnite soldiers in the city, arranged a plot, which enabled the Romans to take the city, and called for renewed friendship with Rome. In Samnium the towns of Allifae, Callifae, and Rufrium were taken by the Romans. The Lucanians and the Apulians (from the toe of Italy) allied with Rome.[55]

News of an alliance between the Samnites and the Vestini (Sabellians who lived by the Adriatic coast, to the north-east of Samnium) reached Rome. In 325 BC the consul Decimus Junius Brutus Scaeva ravaged their territory, forced them into a pitched battle and took the towns of Cutina and Cingilia.[56] The dictator Lucius Papirius Cursor, who had taken over the command of the other consul, who had fallen ill, inflicted a crushing defeat on the Samnites in an unspecified location in 324 BC. The Samnites sued for peace and the dictator withdrew from Samnium. However, the Samnites rejected Rome's peace terms and agreed only a one-year truce, which they broke when they heard that Papirius intended to continue the fight. Livy also said that in that year the Apulians became enemies of Rome. Unfortunately, this information is very vague as the region of Apulia was populated by three separate ethnic groups, the Messapii in the south, the Iapyges in the centre and the Dauni in the north. We know that only Daunia (Land of the Dauni) was caught up in this war. However, this was a collection of independent city-states. Therefore, we do not know who in this area became enemies of Rome. The consuls for 323 BC fought on the two fronts, with C. Sulpicius Longus going to Samnium and Quintus Aemilius Cerretanus to Apulia. There were no battles, but areas were laid waste on both fronts.[57] In 322 BC there were rumours that the Samnites had hired mercenaries and Aulus Cornelius Cossus Arvina was appointed as Dictator. The Samnites attacked his camp in Samnium, which he had to leave. A fierce battle followed and eventually the Samnites were routed. The Samnites offered to surrender, but this was rejected by Rome.[58]

From the Caudine Forks to 316 BC

[edit]

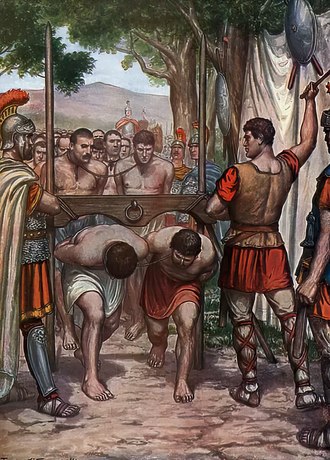

In 321 BC the consuls Titus Veturius Calvinus and Spurius Postumius Albinus were encamped in Calatia (a Campanian town 10 km southeast of Capua). Gaius Pontius, the commander of the Samnites, placed his army at the Caudine Forks and sent some soldiers disguised as shepherds grazing their flock towards Calatia. Their mission was to spread the misinformation that the Samnites were about to attack the city of Lucera in Apulia, which was an ally of Rome. The consuls decided to march to the aid of this city and to take the quicker (but less safe) route through the Caudine Forks. These were two narrow and wooded defiles on the Apennine Mountains with a plain between them. The passage from the first to the second defile was a narrow and difficult ravine. The Samnites blocked this with felled trees and boulders. When the Romans passed through, they also barraged the rear entry to the defile. The Romans were stuck and surrounded by the enemy and set up a fortified camp. Gaius Pontius sent a messenger to his father Herennius, a retired statesman, to ask for advice. His council was to free the Romans immediately. Gaius rejected this and Herenius’ second message was to kill them all. With these contradictory responses Gaius thought that his father had gone senile, but summoned him to the Forks. Herennius said that the first option would lead to peace and friendship with Rome and that with the second one, the loss of two armies would neutralise the Romans for a long time. When asked about a middle course of letting them go and imposing terms on Rome, he said that this "neither wins men friends nor rids them of their enemies." Shaming the Romans would lead them to seek revenge. Gaius decided to demand the Romans to surrender, "evacuate the Samnite territory and withdraw their colonies." The consuls had no choice but to surrender. The Roman soldiers came out of their camp unarmed, underwent the humiliation of passing under the yoke and suffered the mockery of the enemy.[59] The yoke was a symbol of subjugation in which the defeated soldiers had to bow and pass under a yoke used for oxen in disgrace. According to Appian, Pontius used spears as a yoke: "Pontius opened a passage from the defile, and having fixed two spears in the ground and laid another across the top, caused the Romans to go under it as they passed out, one by one."[60]

Livy and other ancient sources maintain that Rome rejected the truce offered by the Samnites and avenged the humiliation with victories. Livy said that there was a two-year truce following victories in 320–319 BC.[61] However, Salmon thinks that, instead, the truce was the result of the agreement which was made at the Caudine Forks.[62] Whatever the case, there was a truce which ended in 316 BC. For a discussion on this debate, see Frederiksen.[63]

This section will continue to follow Livy's account.

Livy wrote that regarding the demands of the Samnites (which in Rome they called the Caudine peace), the consuls said that they were in no position to agree a treaty because this had to be authorised by the vote of the people of Rome and ratified by the fetials (priest-ambassadors) following the proper religious rites. Therefore, instead of a treaty there was a guarantee, the guarantors being the consuls, the officers of the two armies and the quaestors. Six hundred equites (equestrians) were handed over as hostages "whose lives were to be forfeit if the Romans should fail to keep the terms."[64] The dejected Roman soldiers left and were too ashamed to enter Capua, whose inhabitants gave them supplies in commiseration. In Rome people went into mourning, shops were closed and all activities at the Forum were suspended. There was anger towards the soldiers and suggestions to bar them. However, when they arrived people took pity on them. They locked themselves in their homes.[65] Spurius Postumius said to the senate that Rome was not bound to the guarantee at the Caudine Forks because it was given without the authorisation of the people, that there was no impediment to resuming the war and all that Rome owed to the Samnites were the persons and the lives of the guarantors. An army, the fetials and the guarantors to be surrendered were sent to Samnium. Once there, Postumius jostled the knee of a fetial and claimed that he was a Samnite who had violated diplomatic rules. Gaius Pontius denounced Roman duplicity and declared that he deemed the Roman guarantors not to be surrendered. The peace he had hoped for did not materialise. Meanwhile, Satricum (a town in Latium) defected to the Samnites and the Samnites took Fregellae.[66]

In 320 BC the consul Quintus Publilius Philo and Lucius Papirius Cursor marched to Apulia. This move threw the Samnites off. Publilius headed for Luceria, where the Roman hostages were held. He routed a Samnite contingent. However, the Samnites regrouped and besieged the Romans outside Luceria. The army of Papirius advanced along the coast as far as Arpi. The people of that area were well disposed towards the Romans because they were fed up with years of Samnite raids. They supplied the besieged Romans with grain. This forced the Samnites to engage Papirius. There was an indecisive battle and Papirius besieged the Samnites who then surrendered and passed under the yoke. Luceria was taken and the Roman hostages were freed.[67]

In 319 BC the consul Quintus Aemilius Barbula seized Ferentium and Quintus Publilius subdued Satricum, which had rebelled and had hosted a Samnite garrison. In 318 BC envoys from Samnite cities went to Rome to "seek a renewal of the treaty." This was turned down, but a two-year truce was granted. The Apulian cities of Teanum and Canusium submitted to Rome and Apulia was now subdued. In 317 BC Quintus Aemilius Barbula took Nerulum in Lucania.[61]

Presumed resumption of hostilities

[edit]316–313 BC – Operations at Saticula, Sora, and Bovianum

[edit]In 316 BC the dictator Lucius Aemilius besieged Saticula, a Samnite city near the border with Campania. A large Samnite army encamped near the Romans and the Saticulans made a sortie. Aemilius was in a position which was difficult to attack, drove the Saticulans back into the town and then confronted the Samnites, who fled to their camp and left at night. The Samnites then besieged the nearby Plistica, which was an ally of Rome.[68]

In 315 BC the dictator Quintus Fabius Maximus Rullianus took over the operations at Saticula. The Samnites had raised fresh troops, encamped near the city and were trying to force a battle to divert the Romans from the siege. Quintus Fabius concentrated on the city and the Samnites harassed the Roman rampart. The Roman master of the horse Quintus Aulius Cerretanus attacked the Samnites who were harassing the Roman Camp. He killed the Samnite commander and was killed himself. The Samnites left and went on to seize Plistica. The Romans transferred their troops in Apulia and Samnium to deal with Sora, a Roman colony in Latium near the border with Samnium, which had defected to the Samnites and killed the Roman colonists. The Roman army headed for there, but heard that the Samnites were also moving and that they were getting close. The Romans took a diversion and engaged the Samnites at the battle of Lautulae, where they were defeated and their master of the horse, Quintus Aulius, died. He was replaced by Gaius Fabius, who brought a new army and was told to conceal it. Quintus Fabius ordered battle without telling his troops about the new army and simulated a burning of their camp to strengthen their resolve. The soldiers threw the enemy into disarray and Quintus Aulius joined the attack.[69]

In 314 BC the new consuls, Marcus Poetelius and Gaius Sulpicius, took new troops to Sora. The city was in a difficult position to take, but a deserter offered to betray it. He told the Romans to move their camp close to the city and the next night he took ten men on an almost impassable and steep path up to the citadel. He then shouted that the Romans had taken it. The inhabitants panicked and opened the city gates. The conspirators were taken to Rome and executed and a garrison was stationed at Sora. After the Samnite victory at Lautulae three Ausoni cities, Ausona, Minturnae (Ausonia and Minturno) both in Latium, just north of and on the north bank of the river Liris respectively, and Vescia (across the river, in Campania) had sided with the Samnites. Some young nobles from the three cities betrayed them and three Roman detachments were sent. Livy said that "because the leaders were not present when the attack was made, there was no limit to the slaughter, and the Ausonian nation was wiped out." In the same year, Luceria betrayed its Roman garrison to the Samnites. A Roman army which was not far away seized the city. In Rome it was proposed to send 2500 colonists to Luceria. Many voted to destroy the city because of the treachery and, because it was so distant, that many believed that sending colonists there was like sending people into exile, and in hostile territory to boot. However, the colonization proposal was carried. A conspiracy was discovered in Capua and the Samnites decided to try to seize the city. They were confronted by both consuls, Marcus Poetelius Libo and Gaius Sulpicius Longus. The right wing of Poetelius routed its Samnite counterpart. However, Sulpicius, overconfident about a Roman victory, had left his left wing with a contingent to join Poetelius and without him his troops came close to defeat. When he re-joined them, his men prevailed. The Samnites fled to Maleventum, in Samnium.[70]

The two consuls went on to besiege Bovianum, the capital of the Pentri, the largest of the four Samnite tribes, and wintered there. In 313 BC they were replaced by the dictator Gaius Poetelius Libo Visolus. The Samnites took Fregellae and Poetelius moved to retake it, but the Samnites had left at night. He placed a garrison and then marched on Nola (near Naples) to retake it. He set fire to the buildings near the city walls and took the city. Colonies were established at the Volscian island of Pontiae, the Volscian town of Interamna Sucasina and at Suessa Aurunca.

312–308 BC – The Etruscans intervene

[edit]In 312 BC, while the war in Samnium seemed to be winding down, there were rumours of a mobilisation of the Etruscans, who were more feared than the Samnites. While the consul M. Valerius Maximus Corvus was in Samnium, his colleague Publius Decius Mus, who was sick, appointed Gaius Sulpicius Longus as dictator, who made preparations for war.[71]

In 311 BC the consuls Gaius Junius Bubulcus and Quintus Aemilius Barbula divided their command. Junius took on Samnium and Aemilius took on Etruria. The Samnites took the Roman garrison of Cluviae (location unknown) and scourged its prisoners. Junius retook it and then moved on Bovianum and sacked it. The Samnites sought to ambush the Romans. Misinformation that there was a large flock of sheep in an inaccessible mountain meadow was planted. Junius headed for it and was ambushed. While the Romans mounted the slope there was little fighting and when they reached level ground at the top and lined up the Samnites panicked and fled. The woods blocked their escape and most were killed. Meanwhile, the Etruscans besieged Sutrium, an ally which the Romans saw as their key to Etruria. Aemilius came to help and the next day the Etruscans offered battle. It was a long and bloody fight. The Romans were starting to gain the upper hand, but darkness stopped the battle. There was no further fighting that year as the Etruscans had lost their first line and only had their reservists left and the Romans had suffered many casualties.[72]

In 310 BC the consul Quintus Fabius Maximus Rullianus went to Sutrium with reinforcements and was met by a superior force of Etruscans who were lined up for battle. He went up the hills and faced the enemy. The Etruscans charged in haste, throwing away their javelins. The Romans pelted them with javelins and stones. This unsettled the Etruscans and their line wavered. The Romans charged, the Etruscans fled and, as they were cut off by the Roman cavalry, they headed for the mountains instead of their camp. From there they went to the impassable Ciminian Forest, which the Romans were so scared of that none of them had ever crossed it. Marcus Fabius, one of the brothers of the consul, who had been educated by family friends in Caere in Etruria and spoke Etruscan, offered to explore the forest, pretending to be an Etruscan shepherd. He went as far as Camerinum in Umbria, where the locals offered supplies and soldiers to the Romans. Quintus Fabius crossed the forest and ravaged the area around the Cimian Mountains. This enraged the Etruscans, who gathered the largest army they had ever raised and marched on Sutrium. They advanced to the Roman rampart, but the Romans refused to engage, so they waited there. To encourage his outnumbered soldiers Quintus Fabius told them that he had a secret weapon and hinted that the Etruscans were being betrayed. At dawn the Romans exited their camp and attacked the sleeping Etruscans, who were routed. Some fled to their camp, but most made for the hills and the forest. The Etruscan cities of Perusia and Cortona and Arretium sued for peace and obtained a thirty-year truce.[73]

Meanwhile, the other consul, Gaius Marcius Rutilus, captured Allifae (in Campania) from the Samnites and destroyed or seized many forts and villages. The Roman fleet was sent to Pompeii in Campania and from there they pillaged the territory of Nuceria. Greedy for booty, the sailors ventured too far inland and on their way back the country folk killed many of them. The Samnites received a report that the Romans had been besieged by the Etruscans and had decided to confront Gaius Marcius. The report also indicated that, if Gaius Marcius avoided battle, the Samnites would march to Etruria via the lands of the Marsi and the Sabines. Gaius Marcius confronted them and a bloody but indecisive battle was fought where the Romans lost several officers and the consul was wounded. The senate appointed Lucius Papirius Cursor as dictator. However, Quintus Fabius had a grudge against Lucius Papirius. A delegation of former consuls was sent to him to persuade him to accept the Senate's decision, and Fabius reluctantly appointed Papirius. Lucius Papirius relieved Gaius Marcius at Longula, a Volscian town near the Samnite border. He marched out to offer battle. The two armies lined up in front of each other until night and there was no fighting. Meanwhile, a fierce battle was fought in Etruria by an unspecified Etruscan army levied (presumably by Etruscans who had not signed the mentioned treaty) by using the lex sacrata (an arrangement with religious connotations whereby the soldiers had to fight to the death). It confronted the Romans at the Battle of Lake Vadimo. The battle was long-drawn-out affair and with many casualties and the reserves were called in. It was finally resolved by the Roman cavalry which dismounted and fought like a fresh line of infantry and managed to break the exhausted ranks of the enemy. Livy said that this battle broke the might of the Etruscans for the first time as the battle cut off their strength.[74]

In 309 BC Lucius Papirius Cursor won a massive[clarification needed] battle against the Samnites and celebrated the finest triumph there had been thanks to the spoils. The Etruscan cities broke the truce and Quintus Fabius easily defeated the remnants of their troops near Perusia and would have taken the city had it not surrendered. In 308 BC, Quintus Fabius was elected consul again. His colleague was Publius Decius Mus. Quintus Fabius took on Samnium. He refused peace offers by Nuceria Alfaterna and besieged it into surrender. He also fought an unspecified battle where the Marsi joined the Samnites. The Paeligni, who also sided with the Samnites, were defeated next. In Etruria Decius obtained a forty-year truce and grain supplies from Tarquinii, seized some strongholds of Volsinii and ravaged wide areas. All Etruscans sued for a treaty, but he conceded only a one-year truce and required them to give each Roman soldier one year's pay and two tunics. There was a revolt by Umbrians who, backed by Etruscan men, gathered a large army and said that they would ignore Decius and march on Rome. Decius undertook forced marches, encamped near Pupinia, to the north-east of Rome, and called on Fabius to lead his army to Umbria. Fabius marched to Mevania, near Assisi, where the Umbrian troops were. The Umbrians were surprised as they thought he was in Samnium. Some of them fell back to their cities and some pulled out of the war. Others attacked Fabius while he was entrenching his camp, but they were defeated. The leaders of the revolt surrendered and the rest of Umbria capitulated within days.[75]

307–304 BC – Final campaigns in Apulia and Samnium

[edit]In 307 BC the consul Lucius Volumnius Flamma Violens was assigned a campaign against the Salentini of southern Apulia, where he seized several hostile towns. Quintus Fabius was elected as proconsul to conduct the campaign in Samnium. He defeated the Samnites in a pitched battle near Allifae and besieged their camp. The Samnites surrendered, passed under the yoke and their allies were sold into slavery. There were some Hernici among the troops and they were sent to Rome where an inquiry was held to determine whether they were conscripts or volunteers. All of the Hernici, except the peoples of the cities of Aletrium, Ferentium and Verulae, declared war on Rome. Quintus Fabius left Samnium, and the Samnites seized Calatia and Sora with their Roman garrisons. In 306 BC the consul Publius Cornelius Arvina headed for Samnium and his colleague Quintus Marcius Tremulus took on the Hernici. The enemies took all the strategic points between the camps and isolated the two consuls. In Rome two armies were enlisted. However, the Hernici did not engage the Romans, lost three camps, sued for a thirty-year truce and then surrendered unconditionally. Meanwhile, the Samnites were harassing Publius Cornelius and blocking his supply routes. Quintus Marcius came to his aid and was attacked. He advanced through the enemy lines and took their camp, which was empty, and burned it. On seeing the fire Publius Cornelius joined in and blocked the escape of the Samnites, who were slaughtered when the two consuls joined their forces. Some Samnite relief troops also attacked, but they were routed and pursued and begged for peace. In 305 BC the Samnites made forays in Campania.[76]

В 305 г. до н.э. консулы были отправлены в Самниум. Люциус постмиус Мегеллус пошел на Тифернум и Титус Минусия Аугуринус на Бовиануме . В Tifernum была битва, где некоторые из источников Ливия говорят, что постмиус потерпел поражение, в то время как другие говорят, что битва была ровной, и он ушел в горы ночью. Самниты последовали за ним и расположились рядом с ним. Ливи сказал, что он, казалось, хотел получить позицию, где он мог получить обильные запасы. Затем постмиус оставил гарнизон в этом лагере и пошел к своему коллеге, который также расположился лагерем лицом к врагу. Он спровоцировал Тита Минусия вступить в битву, которая затянулась до позднего вечера. Затем присоединился постмиус, и самниты были убиты. На следующий день консулы начали осаду Bovianum, которая быстро упала. В 304 г. до н.э. Самниты отправили посланников в Рим для договоров мира. Подозрительные римляне отправили консул Publius Sempronius Sophus Sompronius Samnium с армией, чтобы исследовать истинные намерения Самнитов. Он путешествовал по всему Самниуму, и везде он нашел мирных людей, которые давали ему припасы. Ливи сказал, что древний договор с Самнитами был восстановлен. Он не указал, какими были термины. [ 77 ]

Последствия

[ редактировать ]После поражения грыжи в 306 г. до н.э. римское гражданство без права голоса было наложено на этот народ, что фактически аннексировало их территорию. В 304 г. до н.э., после мирного договора, Рим послал февраля, чтобы просить о возмещении от Аекси гор Латиума, который неоднократно присоединялся к грыжам, помогая самнитам и после поражения первого, они переходили к врагу Полем Аекси утверждал, что Рим пытается навязать им римское гражданство. Они сказали римским собраниям, что на них наставление римского гражданства составило потерю независимости и является наказанием. Это привело к тому, что римский народ проголосовал за войну на Акей. Оба консула были поручены этой войной. Аекси взимал милицию, но у этого не было четкого командира. Было разногласия по поводу того, предложить ли битва или защитить их лагерь. Опасения по поводу уничтожения ферм и плохого укрепления городов привели к решению рассеять, чтобы защитить города. Римляне обнаружили, что лагерь Акки покинул. Затем они взяли города Акки штурмом, и большинство из них были сожжены. Ливи писал, что «Акейское имя было почти раздирается». [ 78 ] Тем не менее, в 304 г. до н.э. сабеллианские народы современного северного Абруццо , Марси и Маручини (на Адриатическом побережье), а также соседи Оскана последнего, Паэлиньи и Френтани (Осканы, которые жили на южном побережье Абрини и Прибрежная часть современной молизы), предусмотренные договоры с Римом. [ 79 ]

В 303 году до нашей эры в городе Сабин Трефула Суфренас ( Цилиано ) и в Вольтсе -городе Арпиния ( Арпино ) на юге латиума было дано гражданство без права голоса (Civitas Sine Saffragio). Фрусино ( Фрозинон ), также в вольско -городе на юге Латиума, был лишен двух третей своей земли, потому что он сговорился с грыжей, и его заглаживатели были казнены. Колонии были созданы в Альбах Фуценс на земле Аекси и Соры , на территории Вольльжей, которая была взята Самнитами, с 6000 поселенцами, отправленными первым и 4000 к последнему. В 302 г. до н.э. Акей атаковал Альбу Фуценс, но были побеждены колонистами. Gaius Junius Bubulcus был назначен диктатором. Он уменьшил их до подчинения в одной битве. В том же году Вестини (Осканс, который жил на Адриатическом побережье современного Абруццо) создал альянс с Римом. В 301 г. до н.э. земля, сопротивляющаяся Марси, конфискована для создания колонии Карсоли (или Карсеоли, современный Карсоли) с 4000 колонистами, даже через нее находилась на территории Акей. Маркус Валериус Корвус Каленус был назначен диктатором. Он победил Марси, захватил Милюю, Петину и Фесилию и возобновил с ними договор. В 300 г. до н.э. два римских племена (административные районы) были добавлены Aniensis и Terentina. В 299 г. до н.э. римляне осадили и захватили Некин в Умбрии и основали колонию Нарнии. [ 80 ]

Аннексия Trebula Suffenas обеспечила степень контроля над сабинами , которые жили недалеко от Рима. С аннексией арпиниума и большей части земли Фрусино и основанием колонии в Соре, римляне консолидировал контроль над южным латиумом и VOLSCI. Контроль над участком горов Апеннина рядом с латиумом был консолидирован с аннексией грыжи, разрушением городов Айоков, основанием двух колоний на их территории (Альба Фуценс и Казели) и создание римля Племя на земле, взято с Акей. Контроль над Кампанией был консолидирован с обновлением дружбы с Неаполем, с разрушением Авсони и созданием римского племени теретина на земле, которое было аннексировано от Аурунси в 314 году до нашей эры. [ 81 ]

Альянсы с Марси, Маруччини, Палингини, Френтани (в 304 г. до н.э.) и Вестини (в 302 г. до н.э.), которые жили на севере и северо-востоке Самниума, не только дал Рим контроль над этой существенной областью вокруг Самния, но и Это также укрепило свою военную позицию. Альянсы были военными, и союзники снабжали солдат, которые поддерживали римских легионов за свой счет, тем самым увеличивая группу военной рабочей силы, доступной для Рима. В обмене союзников разделяли добычу войны (что может быть значительным) и были защищены Римом.

Однако доминирование Рима над Центральной Италией и частью южной Италии еще не было полностью установлено. Этрурия и Умбрия не были совсем умиротворены. В Умбрии было две экспедиции; Были войны с этрусками в 301 году до нашей эры и в 298 г. до н.э. Последний был годом, когда началась третья Самнитская война. [ 82 ] Вторая война ускорила процесс римской экспансии, а Третья война установила доминирование Рима в соответствующих областях.

Третья Самнитская война (298 до 290 г. до н.э.)

[ редактировать ]

Вспышка

[ редактировать ]В 299 г. до н.э. этруски, возможно, из-за римской колонии, расположенной в Нарнии в ближайшей Дверной Умбрии, подготовленных к войне против Рима. Тем не менее, галлы вторглись в свою территорию, поэтому этруски предложили им деньги для формирования альянса. Галлы согласились, но затем возражали против борьбы с Римом, утверждая, что соглашение было только о них, а не разрушительной этрусской территории. Таким образом, вместо этого этрусцы заплатили галлов и уволили их. Этот инцидент привел римлян к союзнику с Пикентами (которые жили на Адриатическом побережье, на юге современного марша), которые были обеспокоены своими соседями, Сеноне Галлы на севере и предварительным на юге. Последний был союзником с Самнитами. Римляне отправили армию в Этрурию во главе с консулом Титом Манлиусом Торкватом , который погиб в результате несчастного случая. Этруски видели это как предзнаменование для войны. Тем не менее, римляне избрали Маркуса Валериуса Корвуса Каленуса в качестве консула Санфекта (офис, который длился до конца срока срока умершего или удаленного консула), и его отправили в Этрурию. Это привело к тому, что этруссцы остались в своих укреплениях, отказавшись от битвы, хотя римляне разрушили свою землю. Тем временем Picentes предупредил римлян, что самниты готовятся к войне, и что они обратились к ним о помощи. [ 83 ]

В начале 298 г. до н.э. Лукановская делегация отправилась в Рим, чтобы попросить римлян взять их под их защиту, поскольку самниты, не смогли привести их в альянс, вторглись в их территорию. Рим согласился на альянс. Феоли были отправлены в Самнию, чтобы заказать самниты покинуть Луканию . Самниты угрожали их безопасности, а Рим объявил войну. [ 84 ] [ 85 ] Дионисий из Галикарнасса считал, что причиной войны не было римского сострадания к обиде, а страх перед силой, которую самниты получат, если они подавят Луканцев. [ 86 ] Окли предполагает, что Рим вполне мог бы намеренно искать новую войну с Самниумом, союзнив со своими врагами. [ 87 ]

Война

[ редактировать ]298 г. до н.э.: конфликтующие счета

[ редактировать ]Согласно Ливии, консулу Люциуса Корнелиуса Сципиона Барбатуса было назначено Этрурии, а его коллегу Гнаи Фулвиус Максимус Центумалус получил самниты. Барбатус участвовал в битве возле Волтерра (в северной этрурии), которая была прервана закатом. Этруски отступили ночью. Барбатус прошел в районе Фалисканского района и уложил территорию этрусской, к северу от Тибра . Gnaeus Fulvius выиграл в Самниуме и захватил Bovianum и Aufidena . Тем не менее, эпитафия на саркофаге Корнелиуса Сципиона говорит, что он был консулом, цензором и aedile ... [и] ... он захватил Тауразию и Цисауну в Самнии; Он покорил всю Луканию и вернул заложники. Корнелл говорит, что первоначальная надпись была стерта и заменена на все, вероятно, около 200 до н.э., и отмечает, что это «был период, когда были написаны первые истории Рима, что не является случайностью». [ 88 ]

В дополнение к тому, что он требовал, чтобы на надпись записывает его как принятие Тауразии (вероятно, в Беневенто современной провинции ) и сон (неизвестное место), а не Bovianum и Aufidena. [ 89 ] Существует усложнение Furher от Triumphales Fasti (запись римских триумфальных празднований), записавших триумф Гнаэуса Фулвиуса как против Самнеев, так и этрусцев. [ 90 ] Форсайт отмечает, что консультант является единственным государственным офисом Барбатус, который упоминается как удерживаемая, которая дала ему командование легионом. [ 91 ] Современные историки предложили различные альтернативные сценарии, в которых один или оба консулов проводили кампанию как против Самнитов, так и против этрусцев, но без удовлетворительных выводов. [ 92 ] Корнелл говорит, что такое предположение могло бы согласовать источники, но «если это так, ни Ливия, ни надпись не появятся с большим кредитом. Еще раз доказательства, кажется, показывают, что в традиции было большой путаница в традиции о распределении консульства. Команды в Самнитских войнах, и что многие разные версии распространялись в поздней республике ». Его вывод заключается в том, что «невозможно удовлетворительного разрешения этой головоломки». [ 93 ]

Что касается подчинения Лукании и возвращения заложников, Ливи сказала, что Лукановцы готовы дать заложникам как добросовестное обещание. [ 84 ] Корнелл отмечает, что «[t] он намек на то, что представление Лукановцев было результатом военных действий, является хорошим примером того, как события можно улучшить в рассказе». Форсайт отмечает, что Ливи отметила, что в 296 году до нашей эры римляне подавили плебеианские беспорядки в Лукании по поручению Луканийской аристократии. Он утверждает, что это предполагает дивизии в Лукании по альянсу с Римом и что, если бы это было также в 298 г. до н. Соберите согласованные заложники. Форсайт также отмечает, что кампания Барбатуса в Этрурии может быть объяснена тремя способами: 1) она может быть вымышленной; 2) Барбатус мог проводить кампанию как в Самниуме, так и в Этрурии; 3) Барбатус участвовал в кампаниях, связанных с фронтом, которая привела к битве при Страменте в 295 г. до н.э., и что это, возможно, включало операции в Этрурии в этом году, но это могло быть приписано более поздним историкам его консульсии в 298 г. до н.э. Полем Что касается утверждения о том, что Барбатус покорил всю Луканию, Форсайт предполагает, что это «возможно, отчасти правда и частично римское аристократическое преувеличение». [ 94 ]

Оукли также указывает на еще две проблемы с источниками. На отчете Ливи, Бовианум, столица Пентри, крупнейший из четырех самнитских племен, был захвачен в первый год войны, что кажется маловероятным. Frontinus записывает три Stratagems, используемые одним из «Fulvius Nobilior», борясь с Самнитами в Лукании. [ 95 ] Cognomen Nobilior иначе не регистрируется до 255 г. до н.э., через сорок пять лет после окончания Самнитских войн. Поэтому правдоподобным объяснением является то, что Nobilior является ошибкой, и разломы должны быть связаны с консулом 298 г. до н.э. [ 96 ]

297 г. до н.э.: Рим поворачивается к Самниуму

[ редактировать ]Выборы консулов на 297 г. до н.э. произошли на фоне слухов о том, что этруски и самниты поднимали огромные армии. Римляне обратились к Quintus Fabius Maximus Rullianus , самым опытным военному командиру Рима, который не был кандидатом на выборы и отказался от этого предложения. Затем он смягчился на условие, что Publius Decius Mus , который был консул с ним в 308 году до нашей эры, будет избран его коллегой. [ 97 ] Невозможно установить, имел ли у Ливи какие -либо доказательства существования этих слухов, или они просто предполагают его или его источники. [ 98 ]

Ливия является единственным источником событий 297 г. до н.э. Он писал, что посланники из Сутрия , Непет (Римлянские колонии) и Фалерие в южной части Этрурии прибыли в Рим с новостями о том, что этрусские городские государства обсуждали судить за мир. Это освободило оба консулса, которые прошли по Самниуму, Квинтусу Фабиусу через Сору и Публий Дезий через землю Сидичини . Самнитская армия готовилась противостоять им в долине недалеко от Тифернума , но она была побеждена Квиттом Фабиусом. Между тем, Publius Decius разбил лагерь в Maleventum , где апульсская армия присоединилась бы к самнитам в битве против Квинтуса Фабиуса, не победил бы его. Затем два консула провели четыре месяца, разрушив Самнию. Фабий также захватил симетру (место неизвестно). [ 99 ] Нет серьезных проблем с учетной записью Ливи, но нет параллельных источников, чтобы подтвердить это. Маршрут Фабиуса через Сору к Тифернум является запутанным, но не непреодолимым. Появление апулийской армии в Maleventum удивительно, так как ничто не известно о враждебности Апулии к Риму с момента заключения мира в 312 году до нашей эры. Однако апулианцы могли быть разделены на их союз с Римом или были спровоцированы на войну кампанией Барбатуса в предыдущем году. Кампания Publius Decius вписывается в более широкую схему римской войны в юго-восточной Италии; Он мог даже зимовать в Апулии. Никаких триумфов не зарегистрировано ни в этом году ни в одном из консулов, следовательно, они вряд ли имели какие -либо победы, имеющие большое значение или оказали какие -либо глубокие вторжения в Самнию. [ 100 ]

296 г. до н.э.: этруссское вмешательство

[ редактировать ]Консулами для 296 до н г. . Предыдущие консулы получили шестимесячное расширение своего командования в качестве проконсолов для ведения войны в Самниуме. Publius Decius разрушил Самнию, пока не поехал в армию Самнитов за пределами своей территории. Эта армия отправилась в Этрурию, чтобы поддержать предыдущие призывы к альянсу, который был отказан, с запугиванием и настаивал на том, чтобы созван этрусский совет. Самниты отметили, что они не могут победить Рима сами по себе, но армия всех этрусцев, самой богатой нации в Италии, поддержанной армией Самнитов. Тем временем Publius Decius решил переключиться от разрушения сельской местности на атакующие города, когда самнитская армия отсутствовала. Он захватил Мурганцию, сильный город и Ромулею. После этого он отправился в Ферентиум , который находился в южной этрурии. Ливи указал некоторые расхождения между его источниками, отметив, что некоторые анналисты заявили, что Ромулея и Ферентиум были взяты Квиттом Фабиусом, и что Публий Дезиус взял только Мурганцию, в то время как другие сказали, что города были взяты консулами года, а другие все еще давали Вся заслуга Люциуса Волмна, который, по их словам, имел единственное командование в Самниуме. [ 101 ]

Между тем, в Этрурии Геллиус Эгнатиус , командир Самнита, организовала кампанию против Рима. Почти все этрусские городские государства проголосовали за войну, присоединились к ближайшим Умбрийским племенам, и были попытки нанять галлов в качестве вспомогательных. Новости об этом достигли Рима, и Аппиус Клавдий отправился в Этрурию с двумя легионами и 15 000 союзных войск. Люциус Волмм уже ушел в Самнию с двумя легионами и 12 000 союзников. [ 102 ] Это первый раз, когда Ливи дает подробную информацию о римских силах и фигурах для союзных войск для Самнитских войн. Это также первый раз, когда мы слышим о консулах, командующих по двум легионам каждый. Включая силы Проконсулов, в этом году римляне, должно быть, мобилизовали шесть легионов.

Аппиус Клавдий потерпел несколько неудач и потерял доверие своих войск. Люциус Волмм, который принял три укрепления в Самниуме, послал Quintus fabius для подавления беспорядков со стороны плебей в Лукании, оставил разрушение сельского самниума в издатель и отправился в Этрурию. Ливи отмечает, что некоторые анналисты сказали, что Аппиус Клавдий написал ему письмо, чтобы вызвать его из Самниума и что это стало предметом спора между двумя консулами, причем первый отрицал его, а последний настаивал на том, что он был вызван первым. Ливи подумал, что Аппиус Клавдий не написал письмо, но сказал, что хочет отправить своего коллеги обратно в Самнию и почувствовал, что он неблагоприятно отрицал свою потребность в помощи. Однако солдаты умоляли его остаться. Наступил спор между двумя мужчинами, но солдаты настаивали на том, что оба консула сражаются в Этрурии. Этруски столкнулись с Люциусом Волмнмом, а Самниты продвинулись на Аппиус Клавдиус. Ливи сказал, что «враг не мог противостоять силе намного больше, чем они привыкли встретиться». Они были направлены; 7 900 были убиты и 2010 были захвачены. [ 103 ]

Люциус Волмм поспешил обратно в Самниум, потому что истекали залога Квинта Фабиуса и Публия. Тем временем самниты подняли новые войска и совершили набег на римские территории и союзники в Кампании вокруг Капуа и Фалеерства. Люциус Волмм направился в Кампанию и был проинформирован о том, что Самниты вернулись в Самнию, чтобы взять их добычу. Он догнал их лагерь и победил силу, которая была непригодной для борьбы с бременем их добычи. Самнитский командир, Стай Минатий, подвергся нападению заключенных самнитов и доставлен в консул. Сенат решил установить колонии Минтерн, на устье реки Лирис и Синуесса дальше вглубь страны, на бывшей территории Осони . [ 104 ]

295 до н.

[ редактировать ]Самнитские набеги в Кампании создали большую тревогу в Риме. В дополнение к этому, было известно о том, что после вывода армии Люциуса Волмна из Этрурии, этруски вооружили себя, пригласили Самнита Геллиуса Эгнатиуса и Умбрийцев присоединиться к ним в восстании и предложили большие суммы денег Галлы. Затем были сообщения о реальной коалиции между этими четырьмя народами и о том, что была «огромная армия галлов». [ 105 ] Это был первый раз, когда Рим пришлось противостоять коалиции из четырех людей. Там произойдет самая большая война, когда -либо сталкиваемая Рим, и два лучших военных командира, Квинт Фабиус Максимус Руллиан и Publius Decius Mus, были снова избраны в качестве консулов (на 295 г. до н.э.). Команда Люциуса Волмна была продлена в течение года. Квинтус Фабиус отправился в Этрурию с одним легионом, чтобы заменить Аппиуса Клавдиуса, а также покинул этот легион в Клюзие . Затем он отправился в Рим, где обсуждалась война. Было решено, что два консула сражаются в Этрурии. Они отправились с четырьмя легионами, большой кавалерией и 1000 лампанский солдат. Союзники выставили еще большую армию. Люциус Волмм отправился в Самнию с двумя легионами. То, что он пошел с такой большой силой, должно было быть частью диверсионной стратегии, чтобы заставить Самниты реагировать на римские рейды в Самние и ограничить развертывание их войск в Этрурии. Два резервных контингента, возглавляемых простициями, были размещены в районе Фалисканского района и недалеко от Ватиканского холма, соответственно, для защиты Рима. [ 106 ]

Ливи сообщила о двух традициях о событиях в Этрурии в начале 295 г. до н.э. Согласно одному, до того, как консулы отправились в Этрурию, большая сила сенонов отправилась в Клузий, чтобы напасть на римский легион, расположенный там, и разгромствовал его. Не было выживших, чтобы предупредить консулов, которые не знали о катастрофе, пока они не наткнулись на галлических всадников. Согласно другому, Умбрианцы напали на римскую пейзаж, которая была освобождена от помощи из римского лагеря. [ 107 ]

Этруски, Самниты и Умбрицы пересекли горы Апеннин и продвинулись около Стража (в регионе Марче, недалеко от современного сассоферрато). Их план заключался в том, чтобы самниты и Сенонс привлекла римлян и этрусков и умбрийцев, чтобы взять римский лагерь во время битвы. Дезертиры из Clusium сообщили Quintus fabius об этом плане. Консуль приказал легионам в Фалерие и Ватикане, чтобы пройти к Clusium и разрушить свою территорию для другой диверсионной стратегии. Это вытащило этруссцев от Сентиниума, чтобы защитить свою землю. В битве при Стране галлы стояли на правом крыле, а самниты слева. Квинтус Фабиус стоял справа и публично Дециус слева. Ливи сказал, что эти две силы были настолько равномерно соответствуют, что если бы присутствовали этруски и умбрийцы, это было бы катастрофой для римлян. [ 108 ]

Квинтус Фабиус в обороне боролся, чтобы продлить битву в испытание выносливости и ждать, пока враг сможет пометить. Publius Decius сражался более агрессивно и приказал кавалерийскому атаку, которая дважды отодвинула кавалерию Senone. Во второй раз они достигли вражеской пехоты, но перенесли атаку колесницы и были разбросаны и свергнуты. Линия пехоты Дезика была сломана колесницами, а нога Senone атаковала. Publius Decius решил посвятить себя. Этот термин упоминал о военном командире, который молитва богов и запускает себя в линии противника, фактически жертвуя Себя, когда его войска были в ужасных проливах. Этот акт оказал оцелие левое римлян, к которому также присоединились два резервных контингента, которые Квинтус Фабиус призвал помочь. Справа Quintus Fabius сказал кавалерии обойти крыло Самнита и атаковать его на фланге и приказал своей пехоте продвигаться вперед. Затем он позвонил в другие резервы. Самниты бежали мимо линии Сеноне. Сенонс сформировал Формирование Testudo (черепаха) - где мужчины выровняли свои щиты в компактной форме, покрытой щитами спереди и верхней части. Квинтус Фабиус приказал 500 кампанийских урагателей атаковать их сзади. Это должно было быть объединено с толчком по средней линии одного из легионов и атакой кавалерии. Тем временем, Квинт Фабиус взял лагерь Самнита штурмом и отрезал сенам сзади. Senone Gauls потерпели поражение. Римляне потеряли 8700 человек и их врага 20 000. [ 109 ]

Ливи отметила, что некоторые писатели (чьи работы потеряны) преувеличили размер битвы, заявив, что умбрийцы также приняли участие и дали врагу пехоту 60 000 за кавалерию 40 000 и 1000 колесниц и утверждая, что Люциус Волмм и его два легиона также также сражался в битве. Ливи сказал, что Люциус Волмм, вместо этого держал фронт в Самниуме и разгромил силу Самнита возле горы Тиферн. После битвы 5000 самнитов вернулись домой из Стража через землю Паэлиньи. Местные жители напали на них и убили 1000 человек. В Etruria пропатрон Gnaeus Fulvius победил этрусцев. Perusia и Clusium потеряли до 3000 человек. Квинтус Фабиус оставил армию публично -дезиуса, чтобы охранять Этрурию и отправился в Рим, чтобы отпраздновать триумф. В Этрурии Перусия продолжила войну. Аппиус Клавдий был отправлен в главную роль в Армии Дициста в качестве пропатрона, а Квинт Фабий столкнулся и победил Перусини. Самниты напали на районы вокруг реки Лирис (в Формии и Весия), и на реку Вольтурс. Их преследовали Аппиус Клавдий и Люциус Волмм, которые объединили свои силы и победили Самнитов в окрестностях Каатиции, недалеко от Капуа. [ 110 ]

294 г. до н.э.: набеги Самнита

[ редактировать ]В 294 г. до н.э. Самниты совершили набег на три римские армии (одна должна была вернуться в Этрурию, одну, чтобы защитить границу, а третья - на рейд Кампании). Консул Маркус Атилиус Регулус был отправлен на фронт и встретил самнитов в положении, где ни одна из сил не могла совершить набег на территорию врага. Самниты напали на римский лагерь под прикрытием тумана, участвовая в лагере и убив многих мужчин и нескольких офицеров. Римлянам удалось отразить их, но не преследовали их из -за тумана. Другой консул, Люциус Постюмиус Мегеллус , который выздоравливал от болезни, собрал армию союзников в Соре, где самниты были отодвинуты римские фуражиры, и самниты отступили. Люциус Постюмиус продолжил принимать Милиюю и Феритрум, два неопознанных Самнитских города. [ 111 ]

Маркус Атилиус пошел по Лучирии (в Апулии), который осаждался и был побежден. На следующий день была еще одна битва. Римская пехота начала бежать, но была вынуждена вернуться в битву своей кавалерией. Самниты не давали их преимущества, а затем были побеждены. На обратном пути Маркус Атилиус победил Самнитскую Силу, которая пыталась захватить Interamna, римскую колонию на реке Лирис. Другой консул, Люциус Постимиус, перешел из Самнии в Этрурию, не консультируясь с Сенатом. Он разрушил территорию Volsinii и победил горожан, которые вышли из города, чтобы защитить его. Volsinii , Perusia и Arretium подали в суд на мир и получили сорок лет. Ливи упомянул, что были источники с разными историями. В одном, именно Маркус Атилиус отправился в Этрурию и получил триумф. Вместо этого Люциус Постимиус захватил несколько городов в Самниуме, а затем был побежден и ранен в Апулии и укрылся в Люциории. В другом, оба консула сражались в Самниуме и в Лучирии, с обеими сторонами потерпели большие потери. [ 112 ]

293 до н.э.-290 до н.э. поражение Самниума

[ редактировать ]В 293 г. до н.э. свежие войска были взимались по всему Самниуму. Сорок тысяч человек встретились в Аквилонии . Консул Спир Карвилиус Максимус взял ветеранских легионов, которые Маркус Атилиус оставил в Interamna Lirenas в средней долине Лирис и продолжал захватывать Amiternum в Самниуме (не путать с Amiternum в Сабине). Другой консул, Люциус Папирий курсор (сын Люциуса Папирия второй Самнитской войны), взимал новую армию и взял Дуронию штурмом. Затем два консула пошли туда, где были размещены основные силы Самнита. Спериус Карвилиус отправился в Комин и занимался стычками. Люциус Папирий осадил Аквилонию. Оба города были в северо-западном самниуме. Консулы решили атаковать оба одновременно. Люциус Папирий был проинформирован дезертиром, что двадцать контингентов из 400 человек каждая из элитных сил Самнита, которые, в отчаянии Полем Он сообщил своему коллеге, а затем решил перехватить их частью его сил, победив их. Тем временем другая часть его сил напала на Аквилонию. Люциус Париус вновь приступил к ним, и город был взят. Между тем, в Коминиуме, когда Спирюс Карвилиус услышал о двадцати элитных контингентах Самнита (не зная о их поражении со стороны его коллеги), он послал легион и несколько вспомогательных организаций, чтобы держать их в страхе и пошел вперед со своей запланированной атакой на город, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который, который в конце концов сдался. [ 113 ] Форсайт пишет, что битва при Аквилонии «была последней великой битвой войны, и она запечатала судьбу Самнитов». [ 114 ]

С уничтожением Самнитских армий консулы решили штурмовать города. Спериус Карвилиус взял Velia, Palumbinum и Herculaneum (места неизвестны). Люциус Папирий взял Saepinum (Modern Altilia), один из главных городов Самниума. Между тем, этруски атаковали римских союзников, а фалисканцы перешли на этрусцев. С зимним обстановкой и падением снега римляне вышли из Самниума. Люциус Папирий отправился в Рим на его триумф, а затем отправился в Весчи (в Кампании) к зиме и защитил местных жителей от набережений самнитов. Спериус Карвилиус отправился в Этрурию. Он захватил Троилума (место неизвестно) и взял пять крепостей штурмом. Фалисканцы подали в суд на мир и были оштрафованы и дали годовой перемирие. [ 115 ]

Повествование Ливи о третьей войне Самнита заканчивается здесь, с окончанием книги 10. Книги 11–20 были потеряны. Для книги 11 у нас есть только краткое изложение, которое является частью Periochae, краткое изложение его 142 книг (за исключением 136 и 137). Есть упоминание о том, что консул Квинтус Фабиус Максимус Гурджес был побежден в Самниуме и избавлено от армии и унижения благодаря вмешательству его отца, Квинтуса Фабиуса Максимуса Руллиана, который пообещал помочь ему в качестве заместителя. Двое мужчин победили Самнитов и захватили Гай Понтий, командир Самнита, который был напоказ в триумфе и обезглавлен. Гурджес вышел против Каудини, и, по словам Эутропия, его армия была почти уничтожена и потеряла 3000 человек. [ 116 ] Лосось думает, что эта неудача была, вероятно, преувеличением, потому что в следующем году Гурдж был назначен Проконсул, и он снова был консулом в 276 г. до н.э., во время пиррической войны. Он считает, что его последующая победа также была увеличена и является фиктивным ожиданием партнерства отца и сына между Квиттом Фабиусом Максимусом и его сыном во время Второй Пунической войны. [ 117 ]

В 291 г. до н.э. Консул Люциус Постмиус Мегеллус, работающий из Апулии, атаковал племя Хирпини Самнитов и захватил их большой город Венезию. Поскольку его местоположение предлагало контроль над Луканией и Апулией, а также Самниумом, римляне основали самую большую колонию, которую они когда -либо создавали. Дионисий из Галикарнасса дал фигуру из 20 000 колонистов, что невероятно высокое. [ 118 ] Подробности для 290 г. до н.э. скудны, но небольшая сохранившаяся информация предполагает, что консулы Мания Кюриуса Дентатус и Publius Cornelius Rufinus провели кампанию, чтобы вытащить последние карманы сопротивления по всему Самниуму, и, по словам Эутропия, это включало в себя некоторые крупные боевые действия. [ 116 ] [ 119 ]

Последствия

[ редактировать ]Когда Самнитская война закончилась, римляне переехали, чтобы раздавить сабинс, которые жили на горах к востоку от Рима. Мания Кюриуса Дентатус протолкнулся глубоко в территорию Сабин между реками Нар (сегодняшняя Нера , главный приток реки Тибер) и Анио ( Аниеном , еще одним притоком Тибера) и источником реки Авенс ( Велино ). Спериус Карвилиус конфисковал большие участки земли на равнине вокруг Реатра (сегодняшний rieti) и Амитернум (11 км от L 'Aquila), которые он распространял римским поселенцам. [ 120 ] Флорс не дал причины этой кампании. Лосось предполагает, что «это могло быть из -за той роли, которую они сыграли или не смог сыграть в событиях 296/295 [BC]». [ 121 ] Они позволяют самнитам пересечь свою территорию, чтобы отправиться в Этрурию. Форсайт также предположил, что это могло быть наказанием за это. [ 122 ] Ливи упомянула, что Дентат подавил мятежных сабинс. [ 123 ] Сабине получили гражданство без права голоса (Civitas Sine Saffragio), что означало, что их территория была эффективно аннексирована к Римской Республике. Reate и Amiternum получили полное римское гражданство (Civitas Optimo Iure) в 268 г. до н.э.

Корнелл отмечает, что Рим также покорил Praetutii. [ 124 ] Они жили к востоку от Сабинса, на Адриатическом побережье и были в противоречии с Пикентами, которые были римскими союзниками. С этими двумя завоеваниями римская территория простиралась в район Апеннины рядом с ней, и полоса ее протянулась до Адриатического моря. Это в сочетании с упомянутыми альянсами, пораженными после второй Самнитской войны с Марси, Маррацини и Паэлиньи (304 г. до н.э.) и Вестини (302 г. до н.э.), дало Рим контроль над этой частью Центральной Италии. Самниты были вынуждены стать союзниками Рима, которые должны были быть на неравных условиях. Рим предложил договор о дружбе (Foedus amicitiae) тем, кто добровольно сочетается с ней, но не тем, кто стал союзниками в результате поражения. Римляне также создали колонию в Венсии, важную стратегическую точку на юго-востоке Самниума. Лукановцы сохранили свой союз с Римом. Результатом Самнитских войн стало то, что Рим стал великой силой Италии и контролировал большую часть этого.