Сумматор

| Обыкновенный европейский adder | |

|---|---|

| |

| Научная классификация | |

| Домен: | Эукариота |

| Королевство: | Животное |

| Филум: | Chordata |

| Сорт: | Рептилия |

| Заказ: | Шкалы |

| Подотряд: | Змея |

| Семья: | Viperidae |

| Род: | Гадюка |

| Разновидность: | V. berus

|

| Биномиальное название | |

| Viper щетки | |

| |

| Синонимы [ 2 ] | |

|

Виды синонимия | |

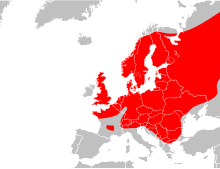

Vipera Berus , также известная как обычная европейская adder [ 3 ] и обычная европейская гадюка , [ 4 ] является видом ядовитой змеи в семействе Viperidae . Этот вид чрезвычайно распространен и может быть найден на протяжении большей части Европы , а также в Восточной Азии . [ 2 ] Есть три признанных подвида .

Известный рядом с множеством общих имен, включая обыкновенного Adder и Common Viper , Adder был предметом большого фольклора в Великобритании и других европейских странах. [ 5 ] Это не считается особенно опасным; [ 3 ] [ страница необходима ] Змея не агрессивна и обычно кусает только тогда, когда действительно провоцируется, наступит или поднимается. Укусы могут быть очень болезненными, но редко смертельны. [ 6 ] , Конкретное имя Berus , является нео-латином и когда-то использовалось для обозначения змеи, возможно, травяной змеи, Natrix Natrix . [ 7 ]

Обыкновенный доклад встречается в разных местах, а сложность среды обитания необходима для различных аспектов его поведения. Он питается небольшими млекопитающими , птицами , ящерицами и амфибиями , а в некоторых случаях на пауках , червях и насекомых . Обыкновенный доклад, как и большинство других гадюков, является ововивипарно . Женщины размножаются один раз каждые два или три года, причем пометы обычно рождаются в конце лета до ранней осени в северном полушарии. Размер пометов варьируется от трех до 20, а молодые остаются со своими матерями в течение нескольких дней. Взрослые растут до общей длины (включая хвост) от 60 до 90 см (от 24 до 35 дюймов) и массой от 50 до 180 г (от 1,8 до 6,3 унции) [ Цитация необходима ] Полем три подвида Признаны , включая назначенные здесь подвид , описанный здесь Vipera Berus Berus . [ 8 ] Считается, что змея не угрожает, хотя она защищена в некоторых странах.

Таксономия

[ редактировать ]Существует три подвида V. Berus , которые признаны действительными, включая номинальные подвиды .

| Подвид [ 8 ] | Автор таксона [ 8 ] | Общее название | Географический диапазон |

|---|---|---|---|

| V. b. berus | ( Linnaeus , 1758 ) | Обыкновенный европейский adder [ 3 ] [ страница необходима ] | Norway , Sweden , Finland , Latvia , Estonia , Lithuania , France , Denmark , Germany , Austria , Switzerland , Northern Italy , Belgium , Netherlands , Great Britain , Poland , Croatia , Czech Republic , Slovakia , Slovenia , Hungary , Romania , Russia , Ukraine , Монголия , Северо -Западный Китай (Северный Синьцзян ) |

| V. b. bosniensis | Boettger , 1889 | Балканский кросс -аддер [ 9 ] | Балканский полуостров |

| V. b. sachalinensis | Zarevskij , 1917 | Сахалинский остров Аддер [ 10 ] | Русский Дальний Восток ( Амур -Албаст , Преморский Край , Хабаровский Край , остров Сахалин ), Северная Корея , Северо -Восточный Китай ( Джилин ) |

Подвид В. б. Bosniensis и V. b. Sachalinensis считались полными видами в некоторых недавних публикациях. [ 3 ] [ страница необходима ]

Название «adder» происходит от Nædre , старого английского слова, которое имело общее значение змея в более старых формах многих германских языков. Он обычно использовался в старой английской версии христианских писаний для дьявола и змея в книге Бытия . [ 5 ] [ 11 ] В 14 -м веке «Nadder» в среднеанглийском был ребракетирован на «Adder» (так же, как «наперрон» стал «фартуком», а « nompere » превратился в «судью»).

В соответствии с его широким распределением и знакомством на протяжении веков, у Vipera Berus есть большое количество общих имен на английском языке, которые включают в себя:

- Обыкновенный европейский аддер , [ 3 ] [ страница необходима ] обычная европейская гадюка , [ 4 ] Европейская гадюка , [ 12 ] северная гадюка , [ 13 ] Adder , Common Adder , пересеканный Viper , European Adder , [ 10 ] Общая гадюка , европейская общая гадяка , Cross Adder , [ 9 ] или общий кросс -аддер . [ 14 ]

В Дании, Норвегии и Швеции змея известна как Hugorm , Hoggorm и Huggorm , примерно перевод как «поразительная змея». В Финляндии он известен как Kyykäärme или просто Kyy , в Эстонии он известен как Rästik , в то время как в Литве он известен как ангис . В Польше змея называется żmija Zygzakowata, что переводится как «зигзаговый гадюк» из -за рисунка на спине.

Описание

[ редактировать ]Относительно толстого тела, взрослые обычно растут до 60 см (24 дюйма) в общей длине (включая хвост), в среднем 55 см (22 дюйма). [ 3 ] [ страница необходима ] Максимальный размер варьируется в зависимости от региона. Самые большие, более 90 см (35 дюймов), встречаются в Скандинавии; Образцы 104 см (41 дюйм) наблюдались там дважды. Во Франции и Великобритании максимальный размер составляет 80–87 см (31–34 дюйма). [ 3 ] [ страница необходима ] Масса диапазона от 50 г (1,8 унции) до 180 граммов (6,3 унции). [ 15 ] [ 16 ]

Голова довольно большая и отчетливая, а ее стороны почти плоские и вертикальны. Край морды обычно поднимается в низкий гребень. Сверху вид, ростральная шкала не видна или только справедливо. Сразу за ростралом есть две (редко) небольшие масштабы.

Dorsally, there are usually five large plates: a squarish frontal (longer than wide, sometimes rectangular), two parietals (sometimes with a tiny scale between the frontal and the parietals), and two long and narrow supraoculars. The latter are large and distinct, each separated from the frontal by one to four small scales. The nostril is situated in a shallow depression within a large nasal scale.

The eye is relatively large—equal in size or slightly larger than the nasal scale—but often smaller in females. Below the supraoculars are six to 13 (usually eight to 10) small circumorbital scales. The temporal scales are smooth (rarely weakly keeled). There are 10–12 sublabials and six to 10 (usually eight or 9) supralabials. Of the latter, the numbers 3 and 4 are the largest, while 4 and 5 (rarely 3 and 4) are separated from the eye by a single row of small scales (sometimes two rows in alpine specimens).[3]

Midbody there are 21 dorsal scales rows (rarely 19, 20, 22, or 23). These are strongly keeled scales, except for those bordering the ventral scales. These scales seem loosely attached to the skin and lower rows become increasingly wide; those closest to the ventral scales are twice as wide as the ones along the midline. The ventral scales number 132–150 in males and 132–158 in females. The anal plate is single. The subcaudals are paired, numbering 32–46 in males and 23–38 in females.[3][page needed]

The colour pattern varies, ranging from very light-coloured specimens with small, incomplete, dark dorsal crossbars to entirely brown ones with faint or clear, darker brown markings, and on to melanistic individuals that are entirely dark and lack any apparent dorsal pattern. However, most have some kind of zigzag dorsal pattern down the entire length of their bodies and tails. The head usually has a distinctive dark V or X on the back. A dark streak runs from the eye to the neck and continues as a longitudinal series of spots along the flanks.[3][page needed]

Unusually for snakes, it is often possible to distinguish the sexes by their colour. Females are usually brownish in hue with dark-brown markings, the males are pure grey with black markings. The basal colour of males will often be slightly lighter than that of the females, making the black zigzag pattern stand out. The melanistic individuals are often females.

Distribution and habitat

[edit]

Vipera berus has a wide range. It can be found across the Eurasian land-mass; from northwestern Europe (Great Britain, Belgium, Netherlands, Scandinavia, Germany, France) across southern Europe (Italy, Serbia, Albania, Croatia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Bulgaria, and northern Greece) and eastern Europe to north of the Arctic Circle, and Russia to the Pacific Ocean, Sakhalin Island, North Korea, northern Mongolia and northern China. It is found farther north than any other snake species.[citation needed] The type locality was originally listed as 'Europa'. Mertens and Müller (1940) proposed restricting the type locality to Uppsala, Sweden[2] and it was eventually restricted to Berthåga, Uppsala by designation of a neotype by Krecsák & Wahlgren (2008).[17]

In several European countries, it is notable as being the only native venomous snake. It is one of only three snake species native to Britain. The other two, the barred grass snake and the smooth snake, are non-venomous.[18]

Sufficient habitat complexity is a crucial requirement for the presence of this species, in order to support its various behaviours—basking, foraging, and hibernation—as well as to offer some protection from predators and human harassment.[3][page needed] It is found in a variety of habitats, including: chalky downs, rocky hillsides, moors, sandy heaths, meadows, rough commons, edges of woods, sunny glades and clearings, bushy slopes and hedgerows, dumps, coastal dunes, and stone quarries. It will venture into wetlands if dry ground is available nearby and thus may be found on the banks of streams, lakes, and ponds.[19]

In much of southern Europe, such as southern France and northern Italy, it is found in either low lying wetlands or at high altitudes. In the Swiss Alps, it may ascend to about 3,000 m (9,800 ft). In Hungary and Russia, it avoids open steppeland; a habitat in which V. ursinii is more likely to occur. In Russia, however, it does occur in the forest steppe zone.[19]

Conservation status

[edit]

In Great Britain, it is illegal to kill, injure, harm or sell adders under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981.[20] The same situation applies to Norway under the Viltloven (The Wildlife Act 1981)[21] and Denmark (1981).[22] In Finland (Nature Conservation Act 9/2023) killing an adder is legal if it's not possible to capture and transfer it to another location[23] and the same provision also applies in Sweden.[24] The common viper is categorised as 'endangered' in Switzerland,[25] and is also protected in some other countries in its range. It is also found in many protected areas.[1]

This species is listed as protected (Appendix III) under the Berne Convention.[26]

The International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species describes the conservation status as of 'least concern' in view of its wide distribution, presumed large population, broad range of habitats, and likely slow rate of decline though it acknowledges the population to be decreasing.[27] Reduction in habitat for a variety of reasons, fragmentation of populations in Europe due to intense agriculture practices, and collection for the pet trade or for venom extraction have been recorded as major contributing factors for its decline.[1] A citizen science based survey in the UK found evidence of extensive population declines in the UK, especially affecting smaller populations.[28] A combination of public pressure and disturbance, habitat fragmentation and poor habitat management were considered the most likely causes of the decline. The release of 47 million non-native pheasants and 10 million partridges each year by countryside estates has also been suggested to have a significant impact on adder populations across the UK, with the possibility the reptile could be extinct by 2032.[29]

Behaviour

[edit]

This species is mainly diurnal, especially in the north of its range. Further south it is said[30] to be active in the evening, and it may even be active at night during the summer months. It is predominantly a terrestrial species, although it has been known to climb up banks and into low bushes in order to bask or search for prey.[19]

Adders are not usually aggressive, tending to be rather timid and biting only when cornered or alarmed. People are generally bitten only after stepping on them or attempting to pick them up. They will usually disappear into the undergrowth at a hint of any danger, but will return once all is quiet, often to the same spot. Occasionally, individual snakes will reveal their presence with a loud and sustained hissing, presumably to warn off potential aggressors. Often, these turn out to be pregnant females. When the adder is threatened, the front part of the body is drawn into an S-shape to prepare for a strike.[19]

The species is cold-adapted and hibernates in the winter. In Great Britain, males and females hibernate for about 150 and 180 days, respectively. In northern Sweden hibernation lasts 8–9 months. On mild winter days, they may emerge to bask where the snow has melted and will often travel across snow. About 15% of adults and 30–40% of juveniles die during hibernation.[3][page needed]

Feeding

[edit]

Their diet consists mainly of small mammals, such as mice, rats, voles, and shrews, as well as lizards. Sometimes, slow worms are taken, and even weasels and moles. Adders also feed on amphibians, such as frogs, newts, and salamanders. Birds are also reported[31] to be consumed, especially nestlings and even eggs, for which they will climb into shrubbery and bushes. Generally, diet varies depending on locality.[19]

Juveniles will eat nestling mammals, small lizards and frogs as well as worms and spiders. One important dietary source for young adders is the alpine salamander (salamadra atra).[32] Because both species live at higher altitudes, S. atra could be a prevalent food source for adders, since there may be few other animals.[32] One study suggests that alpine salamanders could consist of almost half of the adders' diets in some locations.[32] They have been witnessed swallowing these salamanders in the early morning hours.[32] Once they reach about 30 cm (0.98 ft) in length, their diet begins to resemble that of the adults.[3][page needed]

Reproduction

[edit]In Hungary, mating takes place in the last week of April, whilst in the north it happens later (in the second week of May). Mating has also been observed in June and even early October, but it is not known if this autumn mating results in any offspring.[3][page needed] Females often breed once every two years,[19] or even once every three years if the seasons are short and the climate is not conducive.[3][page needed]

Males find females by following their scent trails, sometimes tracking them for hundreds of metres a day. If a female is found and then flees, the male follows. Courtship involves side-by-side parallel 'flowing' behaviour, tongue flicking along the back and excited lashing of the tail. Pairs stay together for one or two days after mating. Males chase away their rivals and engage in combat. Often, this also starts with the aforementioned flowing behaviour before culminating in the dramatic 'adder dance'.[3][page needed] In this act, the males confront each other, raise up the front part of the body vertically, make swaying movements and attempt to push each other to the ground. This is repeated until one of the two becomes exhausted and crawls off to find another mate. Appleby (1971) notes that he has never seen an intruder win one of these contests, as if the frustrated defender is so aroused by courtship that he refuses to lose his chance to mate.[33] There is no record of any biting taking place during these bouts.[19]

Females usually give birth in August or September, but sometimes as early as July, or as late as early October. Litters range in size from 3 to 20. The young are usually born encased in a transparent sac from which they must free themselves. Sometimes, they succeed in freeing themselves from this membrane while still inside the female.

Neonates measure 14 to 23 cm (5.5 to 9.1 in) in total length (including tail), with an average total length of 17 cm (6.7 in). They are born with a fully functional venom apparatus and a reserve supply of yolk within their bodies. They shed their skins for the first time within a day or two. Females do not appear to take much interest in their offspring, but the young have been observed to remain near their mothers for several days after birth.[19]

Venom

[edit]Because of the rapid rate of human expansion throughout the range of this species, bites are relatively common. Domestic animals and livestock are frequent victims. In Great Britain, most instances occur in March–October. In Sweden, there are about 1,300 bites a year, with an estimated 12% that require hospitalisation.[3][page needed] At least eight different antivenoms are available against bites from this species.[34]

Mallow et al. (2003) describe the venom toxicity as being relatively low compared to other viper species. They cite Minton (1974) who reported the LD50 values for mice to be 0.55 mg/kg IV, 0.80 mg/kg IP and 6.45 mg/kg SC. As a comparison, in one test the minimum lethal dose of venom for a guinea pig was 40–67 mg, but only 1.7 mg was necessary when Daboia russelii venom was used.[3][page needed] Brown (1973) gives a higher subcutaneous LD50 range of 1.0–4.0 mg/kg.[14] All agree that the venom yield is low: Minton (1974) mentions 10–18 mg for specimens 48–62 cm (19–24.5 in) in length,[3][page needed] while Brown (1973) lists only 6 mg.[14] Relatively speaking, bites from this species are not highly dangerous.[3][page needed] In Britain there were only 14 known fatalities between 1876 and 2005—the last a 5-year-old child in 1975[6]—and one nearly fatal bite of a 39-year-old woman in Essex in 1998.[6] An 82-year-old woman died following a bite in Germany in 2004, although it is not clear whether her death was due to the effect of the venom.[35] A 44-year-old British man was left seriously ill after he was bitten by an adder in the Dalby Forest, Yorkshire, in 2014.[36] Even so, professional medical help should always be sought as soon as possible after any bite.[37] Very occasionally bites can be life-threatening, particularly in small children, while adults may experience discomfort and disability long after the bite.[6] The length of recovery varies, but may take up to a year.[3][page needed] [38]

Local symptoms include immediate and intense pain, followed after a few minutes (but perhaps by as much as 30 minutes) by swelling and a tingling sensation. Blisters containing blood are not common. The pain may spread within a few hours, along with tenderness and inflammation. Reddish lymphangitic lines and bruising may appear, and the whole limb can become swollen and bruised within 24 hours. Swelling may also spread to the trunk, and with children, throughout the entire body. Necrosis and intracompartmental syndromes are very rare.[6]

Systemic symptoms resulting from anaphylaxis can be dramatic. These may appear within 5 minutes post bite, or can be delayed for many hours. Such symptoms include nausea, retching and vomiting, abdominal colic and diarrhoea, incontinence of urine and faeces, sweating, fever, vasoconstriction, tachycardia, lightheadedness, loss of consciousness, blindness,[citation needed] shock, angioedema of the face, lips, gums, tongue, throat and epiglottis, urticaria and bronchospasm. If left untreated, these symptoms may persist or fluctuate for up to 48 hours.[6] In severe cases, cardiovascular failure may occur.[3][page needed]

Folklore

[edit]Adders were believed to be deaf, which is mentioned in Psalm 58 (v. 4), but snake oil made from them was used as a cure for deafness and earache. Females were thought to swallow their young when threatened and regurgitate them unharmed later. It was believed that they did not die until sunset.[39] Remedies for adder "stings" included killing the snake responsible and rubbing the corpse or its fat on the wound, also holding a pigeon or chicken on the bite, or jumping over water. Adders were thought to be attracted to hazel trees and repelled by ash trees.[5]

Druids believed that large frenzied gatherings of adders occurred in spring, at the centre of which could be found a polished rock called an adder stone or Glain Neidr in the Welsh language. These stones were said to have held supernatural powers.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c Munkhbayar, K.; Rustamov, A; Orlov, N.L.; Jelić, D.; Meyer, A.; Borczyk, B.; Joger, U.; Tomović, L.; Cheylan, M.; Corti, C.; Crnobrnja-Isailović, J.; Vogrin, M.; Sá-Sousa, P.; Pleguezuelos, J.; Sterijovski, B.; Westerström, A.; Schmidt, B.; Sindaco, R.; Borkin, L.; Milto, K. & Nuridjanov, D. (2021). "Vipera berus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T47756146A743903. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T47756146A743903.en. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c McDiarmid RW, Campbell JA, Touré TA (1999). Snake Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, Volume 1. Washington, District of Columbia: Herpetologists' League. ISBN 1-893777-00-6 (series). ISBN 1-893777-01-4 (volume).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Mallow D, Ludwig D, Nilson G (2003). True Vipers: Natural History and Toxinology of Old World Vipers. Malabar, Florida: Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 0-89464-877-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stidworthy J (1974). Snakes of the World. New York: Grosset & Dunlap Inc. 160 pp. ISBN 0-448-11856-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Everyday Adders – the Adder in Folklore". The Herpetological Conservation Trust. Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Warrell, David A. (2005). "Treatment of bites by adders and exotic venomous snakes". British Medical Journal. 331 (7527): 1244–1247. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7527.1244. PMC 1289323. PMID 16308385.

- ^ Gotch, Arthur Frederick (1986). Reptiles: Their Latin Names Explained. Poole, UK: Blandford Press. 176 pp. ISBN 0-7137-1704-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Vipera berus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 15 August 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Steward JW (1971). The Snakes of Europe. Cranbury, New Jersey: Associated University Press (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press). 238 pp. LCCCN 77-163307. ISBN 0-8386-1023-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mehrtens JM (1987). Living Snakes of the World in Color. New York: Sterling Publishers. 480 pp. ISBN 0-8069-6460-X.

- ^ "adder". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ U.S. Navy (1991). Poisonous Snakes of the World. New York: United States Government / Dover Publications Inc. 232 pp. ISBN 0-486-26629-X.

- ^ Vipera berus at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 21 November 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Brown, John H. (1973). Toxicology and Pharmacology of Venoms from Poisonous Snakes. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas. 184 pp. LCCCN 73-229. ISBN 0-398-02808-7.

- ^ Olsson, M.; Madsen, T.; Shine, R. (1997). "Is sperm really so cheap? Costs of reproduction in male adders,Vipera berus". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 264 (1380): 455–459. doi:10.1098/rspb.1997.0065. JSTOR 50437. PMC 1688262. (includes chart showing range of male mass in one population)

- ^ Strugariu, Alexandru; Zamfirescu, Ştefan R.; Gherghel, Iulian (2009). "First record of the adder (Vipera berus berus) in Argeș County (Southern Romania)". Biharean Biologist. 3 (2): 164. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2013. (gives example masses of females).

- ^ Krecsák, László; Wahlgren, Richard (2008). "A survey of the Linnaean type material of Coluber berus, Coluber chersea and Coluber prester (Serpentes, Viperidae)". Journal of Natural History. 42 (35–36): 2343–2377. Bibcode:2008JNatH..42.2343K. doi:10.1080/00222930802126888. S2CID 83947746.

- ^ "Adder (Vipera berus)". ARKive. Archived from the original on 7 November 2008. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Street, Donald (1979). The Reptiles of Northern and Central Europe. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd. 272 pp. ISBN 0-7134-1374-3.

- ^ "Adder (Vipera berus) - facts and status". ARKive. Archived from the original on 11 July 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2010. This ref cites Beebee T, & Griffiths R. (2000) Amphibians and Reptiles: a Natural History of the British Herpetofauna. London: Harper Collins Publishers Ltd. as the source.

- ^ "Hoggorm". WWF Norway (in Norwegian).

- ^ "Hugorm". Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark. Miljø- og Fødevareministeriet. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ "9/2023 English - Translation of Finnish acts". Ympäristöministeriö (Ministry of the Environment). Chapter 8 Section 70. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ «Специальное регулирование защиты (2007: 845)» . Министерство климата и бизнеса. § 10 . Получено 12 июня 2024 года .

- ^ Monney JC, Meyer A (2005). Красный список исчезающих рептилий в Швейцарии . Под редакцией Федерального офиса для окружающей среды, леса и ландшафта Бувала, Берна и Координационного центра амфибий и защиты рептилий Швейцарии, Берн. Серия Бувала.

- ^ «Конвенция о сохранении европейской дикой природы и естественной среды обитания, Приложение III» . Совет Европы . 19 сентября 1979 года . Получено 6 сентября 2021 года .

- ^ «IV: категории». 2001 Категории и критерии IUCN Red List, версия 3.1 (PDF) (2 -е изд.). Международный союз сохранения природы. 2012. ISBN 978-2-8317-1435-6 Полем Получено 14 февраля 2010 года .

- ^ Гарднер, Эмма; Джулиан, Анжела; Монах, Крис; Бейкер, Джон (2019). «Сделайте подсчет щедрости: тенденции населения от гражданского научного обследования британских добавок» (PDF) . Герпетологический журнал . 29 : 57–70. doi : 10.33256/hj29.1.5770 . S2CID 92204234 .

- ^ Милтон, Николас (1 октября 2020 г.). «Game Birds» могут уничтожить добавок в большинстве Британии в течение 12 лет » . Хранитель . ISSN 0261-3077 . Получено 1 октября 2020 года .

- ^ Boulenger, GA (1913). Змеи Европы . Лондон: Methuen & Co. с. XI + 269 ( Vipera Berus , с. 230–239, рис. 35).

- ^ Лейтон, Джеральд Р. (1901). Жизненная история британских змей и их местное распространение на Британских островах . Эдинбург и Лондон: Блэквуд и сыновья. п. 84. ISBN 1-4446-3091-1 Полем Получено 8 февраля 2010 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Анибальди, Клаудио; Луизелли, Лука ; Капула, Массимо (1995). «Диета ювенильной ассарс, Виперра Берус, в альпийской среде обитания». Амфибийская рептилия . 16 (4): 404–407. Doi : 10.1163/156853895x00488 . ISSN 0173-5373 .

- ^ Appleby, Leonard G. (1971). Британские змеи . Лондон: Дж. Бейкер. 150 стр. ISBN 0-212-98393-8 .

- ^ « Виперра -берус антиомы» . Мюнхенский антител индекс (Mavin) . Архивировано с оригинала 17 апреля 2019 года . Получено 15 сентября 2006 года .

- ^ « Тенические змеи: смерть от Креузоттербисса » ? Совместный информационный центр ядов Эрфурт (на немецком языке). 4 мая 2004 года. Архивировано из оригинала 21 июля 2011 года . Получено 6 сентября 2021 года .

- ^ «Не собирайте змей предупреждают чиновников после того, как человек укушен в Йоркширском лесу» . Йоркширский пост . 7 августа 2014 года . Получено 6 сентября 2021 года .

- ^ МакКиллоп, Энн (апрель 2021 г.). «Совет по укусам adder» . Обучение первой помощи .

- ^ « Записываемое количество кусочков Hogworm » [рекордное количество укусов от гадюков]. Aftenposten (на норвежском). 9 июля 2018 года . Получено 11 июня 2021 года .

- ^ Симпсон, Жаклин; Руд, Стивен (2000). "Вход для" Adder " . Словарь английского фольклора . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0192100191 .

Дальнейшее чтение

[ редактировать ]- Ananjeva NB , Borkin LJ , Darevsky IS , Orlov NL (1998). [ Амфибии и рептилии. Энциклопедия природы России ]. Москва: ABF. (на русском языке).

- Арнольд Эн , Бертон Дж.А. (1978). Полевое руководство по рептилиям и амфибиям Британии и Европы . Лондон: Коллинз. 272 стр. ISBN 0-00-219318-3 . ( Vipere Berus , стр. 217-218 + табличка 39 + карта 122).

- Boulenger GA (1896). Каталог змей в Британском музее (естественная история). Том III, содержащий ... Viperidæ. Лондон: попечители Британского музея (естественная история). (Тейлор и Фрэнсис, принтеры). XIV + 727 стр. + Пластин I.- XXV. ( Vipera Berus , с. 476–481).

- Goin CJ , Goin OB , Zug GR (1978). Введение в герпетологию: третье издание . Сан -Франциско: WH Freeman. XI + 378 стр. ISBN 0-7167-0020-4 . ( Vipera Berrus , с. 122, 188, 334).

- Ян Г , Сорделли Ф. (1874). Офидийская общая иконография: сорок пятая доставка. Париж: Байлььер. Индекс + платформы I.- VI. ( Vipera Berus 1; вар. Пресс 2-4; вар. Концепция , пластинка II, Рисунки , пластинка II, рис . , пластинка II, рис.

- Joger U , Lenk P , Baraan I , Böhme W , Zegler T , Hedrich P , Wink M (1997). «Филогенетическое положение Виперра Барани и Виперы Николски с комплексом Виперры Берус » Aretologica Bonnsis 185-1

- Linnaeus 100 (1758). Системная природа трех королевств, в соответствии с классами, порядками, родами, видами, с персонажами, различиями, синонимичными местами. Том I. Десятый, реформатор. Стокгольм: Л. Сальвиус. 824 стр. ( Coluber Berus , стр. 217).

- Минтон С.А. Младший (1974). Болезнь яда . Спрингфилд, Иллинойс: CC Thomas Publ. 256 стр. ISBN 978-0-398-03051-3 .

- Моррис Па (1948). Книга змей мальчика: как узнать и понять их . Том гуманизирующей науки серии, под редакцией Жака Кэттелла . Нью -Йорк: Рональд Пресс. VIII + 185 стр. (Общая гадюка, Vipera Berus , с. 154–155, 182).

- Вустер, Вольфганг ; Аллум, Кристофер Се; Bjargardóttir, I. Birta; Бейли, Кимберли Л.; Доусон, Карен Дж.; Guenioui, Jamel; Льюис, Джон; МакГурк, Джо; Мур, Аликс Г.; Нисканен, Марти; Поллард, Кристофер П. (2004). «Требуются ли апосематизм и мимика Бейтсян яркие цвета? Тест, используя европейские маркировки гадюки» . Труды Королевского общества Лондона. Серия B: Биологические науки . 271 (1556): 2495–2499. doi : 10.1098/rspb.2004.2894 . PMC 1691880 . PMID 15590601 .

Внешние ссылки

[ редактировать ]Wikimedia Commons имеет средства массовой информации, связанные с Vipera Berus |

Wikispecies имеет информацию, связанную с Vipera Berus . |