млекопитающее

| Млекопитающие Временной диапазон: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Amniota |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Mammaliaformes |

| Class: | Mammalia Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Living subgroups | |

Млекопитающее mamma (от латинского « грудь») [1] — позвоночное животное класса млекопитающих ( / m ə ˈ m eɪ l i . ə / ) . Млекопитающие характеризуются наличием молоко вырабатывающих молочных желез, для кормления детенышей, неокортексной области мозга, шерсти или волос и трех косточек среднего уха . Эти характеристики отличают их от рептилий и птиц , от которых их предки отделились в каменноугольном периоде более 300 миллионов лет назад. около 6400 современных видов Описано млекопитающих, разделенных на 29 отрядов .

Крупнейшими отрядами млекопитающих по числу видов являются грызуны , летучие мыши и эвлипотифлы (в том числе ежи , кроты и землеройки ). Следующие три — приматы (включая людей , обезьян и лемуров ), парнокопытные (включая свиней , верблюдов и китов ) и хищные животные (включая кошек , собак и тюленей ).

Млекопитающие — единственные живые члены Synapsida ; эта клада вместе с Sauropsida (рептилиями и птицами) составляет более крупную кладу Amniota . Ранние синапсиды называются « пеликозаврами ». Более продвинутые терапсиды стали доминировать в средней перми . Млекопитающие произошли от цинодонтов , развитой группы терапсидов, в период от позднего триаса до ранней юры . Млекопитающие достигли своего современного разнообразия в палеогеновом и неогеновом периодах кайнозойской эры, после вымирания нептичьих динозавров , и были доминирующей группой наземных животных с 66 миллионов лет назад до настоящего времени.

Основной тип тела млекопитающих — четвероногий , и большинство млекопитающих используют свои четыре конечности для передвижения по земле ; но у некоторых конечности приспособлены к жизни на море , в воздухе , на деревьях , под землей или на двух ногах . Размер млекопитающих варьируется от шмелиной летучей мыши длиной 30 м (98 футов) размером 30–40 мм (1,2–1,6 дюйма) до синего кита — возможно, самого крупного животного, когда-либо жившего на свете. Максимальная продолжительность жизни варьируется от двух лет у землеройки до 211 лет у гренландского кита . Все современные млекопитающие рождают живых детенышей, за исключением пяти видов однопроходных , которые являются яйцекладущими млекопитающими. Самая богатая видами группа млекопитающих, инфракласс , называемый плацентами , имеет плаценту , которая обеспечивает питание плода во время беременности .

Most mammals are intelligent, with some possessing large brains, self-awareness, and tool use. Mammals can communicate and vocalize in several ways, including the production of ultrasound, scent-marking, alarm signals, singing, echolocation; and, in the case of humans, complex language. Mammals can organize themselves into fission–fusion societies, harems, and hierarchies—but can also be solitary and territorial. Most mammals are polygynous, but some can be monogamous or polyandrous.

Domestication of many types of mammals by humans played a major role in the Neolithic Revolution, and resulted in farming replacing hunting and gathering as the primary source of food for humans. This led to a major restructuring of human societies from nomadic to sedentary, with more co-operation among larger and larger groups, and ultimately the development of the first civilizations. Domesticated mammals provided, and continue to provide, power for transport and agriculture, as well as food (meat and dairy products), fur, and leather. Mammals are also hunted and raced for sport, kept as pets and working animals of various types, and are used as model organisms in science. Mammals have been depicted in art since Paleolithic times, and appear in literature, film, mythology, and religion. Decline in numbers and extinction of many mammals is primarily driven by human poaching and habitat destruction, primarily deforestation.

Classification

Mammal classification has been through several revisions since Carl Linnaeus initially defined the class, and at present, no classification system is universally accepted. McKenna & Bell (1997) and Wilson & Reeder (2005) provide useful recent compendiums.[2] Simpson (1945)[3] provides systematics of mammal origins and relationships that had been taught universally until the end of the 20th century.However, since 1945, a large amount of new and more detailed information has gradually been found: The paleontological record has been recalibrated, and the intervening years have seen much debate and progress concerning the theoretical underpinnings of systematization itself, partly through the new concept of cladistics. Though fieldwork and lab work progressively outdated Simpson's classification, it remains the closest thing to an official classification of mammals, despite its known issues.[4]

Most mammals, including the six most species-rich orders, belong to the placental group. The three largest orders in numbers of species are Rodentia: mice, rats, porcupines, beavers, capybaras, and other gnawing mammals; Chiroptera: bats; and Soricomorpha: shrews, moles, and solenodons. The next three biggest orders, depending on the biological classification scheme used, are the primates: apes, monkeys, and lemurs; the Cetartiodactyla: whales and even-toed ungulates; and the Carnivora which includes cats, dogs, weasels, bears, seals, and allies.[5] According to Mammal Species of the World, 5,416 species were identified in 2006. These were grouped into 1,229 genera, 153 families and 29 orders.[5] In 2008, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) completed a five-year Global Mammal Assessment for its IUCN Red List, which counted 5,488 species.[6] According to research published in the Journal of Mammalogy in 2018, the number of recognized mammal species is 6,495, including 96 recently extinct.[7]

Definitions

The word "mammal" is modern, from the scientific name Mammalia coined by Carl Linnaeus in 1758, derived from the Latin mamma ("teat, pap"). In an influential 1988 paper, Timothy Rowe defined Mammalia phylogenetically as the crown group of mammals, the clade consisting of the most recent common ancestor of living monotremes (echidnas and platypuses) and Therian mammals (marsupials and placentals) and all descendants of that ancestor.[8] Since this ancestor lived in the Jurassic period, Rowe's definition excludes all animals from the earlier Triassic, despite the fact that Triassic fossils in the Haramiyida have been referred to the Mammalia since the mid-19th century.[9] If Mammalia is considered as the crown group, its origin can be roughly dated as the first known appearance of animals more closely related to some extant mammals than to others. Ambondro is more closely related to monotremes than to therian mammals while Amphilestes and Amphitherium are more closely related to the therians; as fossils of all three genera are dated about 167 million years ago in the Middle Jurassic, this is a reasonable estimate for the appearance of the crown group.[10]

T. S. Kemp has provided a more traditional definition: "Synapsids that possess a dentary–squamosal jaw articulation and occlusion between upper and lower molars with a transverse component to the movement" or, equivalently in Kemp's view, the clade originating with the last common ancestor of Sinoconodon and living mammals.[11] The earliest-known synapsid satisfying Kemp's definitions is Tikitherium, dated 225 Ma, so the appearance of mammals in this broader sense can be given this Late Triassic date.[12][13]However, this animal may have actually evolved during the Neogene.[14]

McKenna/Bell classification

In 1997, the mammals were comprehensively revised by Malcolm C. McKenna and Susan K. Bell, which has resulted in the McKenna/Bell classification. The authors worked together as paleontologists at the American Museum of Natural History. McKenna inherited the project from Simpson and, with Bell, constructed a completely updated hierarchical system, covering living and extinct taxa, that reflects the historical genealogy of Mammalia.[4] Their 1997 book, Classification of Mammals above the Species Level,[15] is a comprehensive work on the systematics, relationships and occurrences of all mammal taxa, living and extinct, down through the rank of genus, though molecular genetic data challenge several of the groupings.

In the following list, extinct groups are labelled with a dagger (†).

Class Mammalia

- Subclass Prototheria: monotremes: echidnas and the platypus

- Subclass Theriiformes: live-bearing mammals and their prehistoric relatives

- Infraclass †Allotheria: multituberculates

- Infraclass †Eutriconodonta: eutriconodonts

- Infraclass Holotheria: modern live-bearing mammals and their prehistoric relatives

- Superlegion †Kuehneotheria

- Supercohort Theria: live-bearing mammals

- Cohort Marsupialia: marsupials

- Magnorder Australidelphia: Australian marsupials and the monito del monte

- Magnorder Ameridelphia: New World marsupials. Now considered paraphyletic, with shrew opossums being closer to australidelphians.[16]

- Cohort Placentalia: placentals

- Magnorder Xenarthra: xenarthrans

- Magnorder Epitheria: epitheres

- Superorder †Leptictida

- Superorder Preptotheria

- Grandorder Anagalida: lagomorphs, rodents and elephant shrews

- Grandorder Ferae: carnivorans, pangolins, †creodonts and relatives

- Grandorder Lipotyphla: insectivorans

- Grandorder Archonta: bats, primates, colugos and treeshrews (now considered paraphyletic, with bats being closer to other groups)

- Grandorder Euungulata: ungulates

- Order Tubulidentata incertae sedis: aardvark

- Mirorder Eparctocyona: †condylarths, whales and artiodactyls (even-toed ungulates)

- Mirorder †Meridiungulata: South American ungulates

- Mirorder Altungulata: perissodactyls (odd-toed ungulates), elephants, manatees and hyraxes

- Cohort Marsupialia: marsupials

Molecular classification of placentals

As of the early 21st century, molecular studies based on DNA analysis have suggested new relationships among mammal families. Most of these findings have been independently validated by retrotransposon presence/absence data.[18] Classification systems based on molecular studies reveal three major groups or lineages of placental mammals—Afrotheria, Xenarthra and Boreoeutheria—which diverged in the Cretaceous. The relationships between these three lineages is contentious, and all three possible hypotheses have been proposed with respect to which group is basal. These hypotheses are Atlantogenata (basal Boreoeutheria), Epitheria (basal Xenarthra) and Exafroplacentalia (basal Afrotheria).[19] Boreoeutheria in turn contains two major lineages—Euarchontoglires and Laurasiatheria.

Estimates for the divergence times between these three placental groups range from 105 to 120 million years ago, depending on the type of DNA used (such as nuclear or mitochondrial)[20] and varying interpretations of paleogeographic data.[19]

| Tarver et al. 2016[21] | Sandra Álvarez-Carretero et al. 2022[22][23] |

|---|---|

Evolution

Origins

Synapsida, a clade that contains mammals and their extinct relatives, originated during the Pennsylvanian subperiod (~323 million to ~300 million years ago), when they split from the reptile lineage. Crown group mammals evolved from earlier mammaliaforms during the Early Jurassic. The cladogram takes Mammalia to be the crown group.[24]

| Mammaliaformes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Evolution from older amniotes

The first fully terrestrial vertebrates were amniotes. Like their amphibious early tetrapod predecessors, they had lungs and limbs. Amniotic eggs, however, have internal membranes that allow the developing embryo to breathe but keep water in. Hence, amniotes can lay eggs on dry land, while amphibians generally need to lay their eggs in water.

The first amniotes apparently arose in the Pennsylvanian subperiod of the Carboniferous. They descended from earlier reptiliomorph amphibious tetrapods,[25] which lived on land that was already inhabited by insects and other invertebrates as well as ferns, mosses and other plants. Within a few million years, two important amniote lineages became distinct: the synapsids, which would later include the common ancestor of the mammals; and the sauropsids, which now include turtles, lizards, snakes, crocodilians and dinosaurs (including birds).[26] Synapsids have a single hole (temporal fenestra) low on each side of the skull. Primitive synapsids included the largest and fiercest animals of the early Permian such as Dimetrodon.[27] Nonmammalian synapsids were traditionally—and incorrectly—called "mammal-like reptiles" or pelycosaurs; we now know they were neither reptiles nor part of reptile lineage.[28][29]

Therapsids, a group of synapsids, evolved in the Middle Permian, about 265 million years ago, and became the dominant land vertebrates.[28] They differ from basal eupelycosaurs in several features of the skull and jaws, including: larger skulls and incisors which are equal in size in therapsids, but not for eupelycosaurs.[28] The therapsid lineage leading to mammals went through a series of stages, beginning with animals that were very similar to their early synapsid ancestors and ending with probainognathian cynodonts, some of which could easily be mistaken for mammals. Those stages were characterized by:[30]

- The gradual development of a bony secondary palate.

- Abrupt acquisition of endothermy among Mammaliamorpha, thus prior to the origin of mammals by 30–50 millions of years [31].

- Progression towards an erect limb posture, which would increase the animals' stamina by avoiding Carrier's constraint. But this process was slow and erratic: for example, all herbivorous nonmammaliaform therapsids retained sprawling limbs (some late forms may have had semierect hind limbs); Permian carnivorous therapsids had sprawling forelimbs, and some late Permian ones also had semisprawling hindlimbs. In fact, modern monotremes still have semisprawling limbs.

- The dentary gradually became the main bone of the lower jaw which, by the Triassic, progressed towards the fully mammalian jaw (the lower consisting only of the dentary) and middle ear (which is constructed by the bones that were previously used to construct the jaws of reptiles).

First mammals

The Permian–Triassic extinction event about 252 million years ago, which was a prolonged event due to the accumulation of several extinction pulses, ended the dominance of carnivorous therapsids.[32] In the early Triassic, most medium to large land carnivore niches were taken over by archosaurs[33] which, over an extended period (35 million years), came to include the crocodylomorphs,[34] the pterosaurs and the dinosaurs;[35] however, large cynodonts like Trucidocynodon and traversodontids still occupied large sized carnivorous and herbivorous niches respectively. By the Jurassic, the dinosaurs had come to dominate the large terrestrial herbivore niches as well.[36]

The first mammals (in Kemp's sense) appeared in the Late Triassic epoch (about 225 million years ago), 40 million years after the first therapsids. They expanded out of their nocturnal insectivore niche from the mid-Jurassic onwards;[37] the Jurassic Castorocauda, for example, was a close relative of true mammals that had adaptations for swimming, digging and catching fish.[38] Most, if not all, are thought to have remained nocturnal (the nocturnal bottleneck), accounting for much of the typical mammalian traits.[39] The majority of the mammal species that existed in the Mesozoic Era were multituberculates, eutriconodonts and spalacotheriids.[40] The earliest-known metatherian is Sinodelphys, found in 125-million-year-old Early Cretaceous shale in China's northeastern Liaoning Province. The fossil is nearly complete and includes tufts of fur and imprints of soft tissues.[41]

The oldest-known fossil among the Eutheria ("true beasts") is the small shrewlike Juramaia sinensis, or "Jurassic mother from China", dated to 160 million years ago in the late Jurassic.[42] A later eutherian relative, Eomaia, dated to 125 million years ago in the early Cretaceous, possessed some features in common with the marsupials but not with the placentals, evidence that these features were present in the last common ancestor of the two groups but were later lost in the placental lineage.[43] In particular, the epipubic bones extend forwards from the pelvis. These are not found in any modern placental, but they are found in marsupials, monotremes, other nontherian mammals and Ukhaatherium, an early Cretaceous animal in the eutherian order Asioryctitheria. This also applies to the multituberculates.[44] They are apparently an ancestral feature, which subsequently disappeared in the placental lineage. These epipubic bones seem to function by stiffening the muscles during locomotion, reducing the amount of space being presented, which placentals require to contain their fetus during gestation periods. A narrow pelvic outlet indicates that the young were very small at birth and therefore pregnancy was short, as in modern marsupials. This suggests that the placenta was a later development.[45]

One of the earliest-known monotremes was Teinolophos, which lived about 120 million years ago in Australia.[46] Monotremes have some features which may be inherited from the original amniotes such as the same orifice to urinate, defecate and reproduce (cloaca)—as lizards and birds also do—[47] and they lay eggs which are leathery and uncalcified.[48]

Earliest appearances of features

Hadrocodium, whose fossils date from approximately 195 million years ago, in the early Jurassic, provides the first clear evidence of a jaw joint formed solely by the squamosal and dentary bones; there is no space in the jaw for the articular, a bone involved in the jaws of all early synapsids.[49]

The earliest clear evidence of hair or fur is in fossils of Castorocauda and Megaconus, from 164 million years ago in the mid-Jurassic. In the 1950s, it was suggested that the foramina (passages) in the maxillae and premaxillae (bones in the front of the upper jaw) of cynodonts were channels which supplied blood vessels and nerves to vibrissae (whiskers) and so were evidence of hair or fur;[50][51] it was soon pointed out, however, that foramina do not necessarily show that an animal had vibrissae, as the modern lizard Tupinambis has foramina that are almost identical to those found in the nonmammalian cynodont Thrinaxodon.[29][52] Popular sources, nevertheless, continue to attribute whiskers to Thrinaxodon.[53] Studies on Permian coprolites suggest that non-mammalian synapsids of the epoch already had fur, setting the evolution of hairs possibly as far back as dicynodonts.[54]

When endothermy first appeared in the evolution of mammals is uncertain, though it is generally agreed to have first evolved in non-mammalian therapsids.[54][55] Modern monotremes have lower body temperatures and more variable metabolic rates than marsupials and placentals,[56] but there is evidence that some of their ancestors, perhaps including ancestors of the therians, may have had body temperatures like those of modern therians.[57] Likewise, some modern therians like afrotheres and xenarthrans have secondarily developed lower body temperatures.[58]

The evolution of erect limbs in mammals is incomplete—living and fossil monotremes have sprawling limbs. The parasagittal (nonsprawling) limb posture appeared sometime in the late Jurassic or early Cretaceous; it is found in the eutherian Eomaia and the metatherian Sinodelphys, both dated to 125 million years ago.[59] Epipubic bones, a feature that strongly influenced the reproduction of most mammal clades, are first found in Tritylodontidae, suggesting that it is a synapomorphy between them and mammaliaformes. They are omnipresent in non-placental mammaliaformes, though Megazostrodon and Erythrotherium appear to have lacked them.[60]

It has been suggested that the original function of lactation (milk production) was to keep eggs moist. Much of the argument is based on monotremes, the egg-laying mammals.[61][62] In human females, mammary glands become fully developed during puberty, regardless of pregnancy.[63]

Rise of the mammals

Therian mammals took over the medium- to large-sized ecological niches in the Cenozoic, after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event approximately 66 million years ago emptied ecological space once filled by non-avian dinosaurs and other groups of reptiles, as well as various other mammal groups,[65] and underwent an exponential increase in body size (megafauna).[66] Then mammals diversified very quickly; both birds and mammals show an exponential rise in diversity.[65] For example, the earliest-known bat dates from about 50 million years ago, only 16 million years after the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs.[67]

Molecular phylogenetic studies initially suggested that most placental orders diverged about 100 to 85 million years ago and that modern families appeared in the period from the late Eocene through the Miocene.[68] However, no placental fossils have been found from before the end of the Cretaceous.[69] The earliest undisputed fossils of placentals come from the early Paleocene, after the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs.[69] (Scientists identified an early Paleocene animal named Protungulatum donnae as one of the first placental mammals,[70] but it has since been reclassified as a non-placental eutherian.)[71] Recalibrations of genetic and morphological diversity rates have suggested a Late Cretaceous origin for placentals, and a Paleocene origin for most modern clades.[72]

The earliest-known ancestor of primates is Archicebus achilles[73] from around 55 million years ago.[73] This tiny primate weighed 20–30 grams (0.7–1.1 ounce) and could fit within a human palm.[73]

Anatomy

Distinguishing features

Living mammal species can be identified by the presence of sweat glands, including those that are specialized to produce milk to nourish their young.[74] In classifying fossils, however, other features must be used, since soft tissue glands and many other features are not visible in fossils.[75]

Many traits shared by all living mammals appeared among the earliest members of the group:

- Jaw joint – The dentary (the lower jaw bone, which carries the teeth) and the squamosal (a small cranial bone) meet to form the joint. In most gnathostomes, including early therapsids, the joint consists of the articular (a small bone at the back of the lower jaw) and quadrate (a small bone at the back of the upper jaw).[49]

- Middle ear – In crown-group mammals, sound is carried from the eardrum by a chain of three bones, the malleus, the incus and the stapes. Ancestrally, the malleus and the incus are derived from the articular and the quadrate bones that constituted the jaw joint of early therapsids.[76]

- Tooth replacement – Teeth can be replaced once (diphyodonty) or (as in toothed whales and murid rodents) not at all (monophyodonty).[77] Elephants, manatees, and kangaroos continually grow new teeth throughout their life (polyphyodonty).[78]

- Prismatic enamel – The enamel coating on the surface of a tooth consists of prisms, solid, rod-like structures extending from the dentin to the tooth's surface.[79]

- Occipital condyles – Two knobs at the base of the skull fit into the topmost neck vertebra; most other tetrapods, in contrast, have only one such knob.[80]

For the most part, these characteristics were not present in the Triassic ancestors of the mammals.[81] Nearly all mammaliaforms possess an epipubic bone, the exception being modern placentals.[82]

Sexual dimorphism

On average, male mammals are larger than females, with males being at least 10% larger than females in over 45% of investigated species. Most mammalian orders also exhibit male-biased sexual dimorphism, although some orders do not show any bias or are significantly female-biased (Lagomorpha). Sexual size dimorphism increases with body size across mammals (Rensch's rule), suggesting that there are parallel selection pressures on both male and female size. Male-biased dimorphism relates to sexual selection on males through male–male competition for females, as there is a positive correlation between the degree of sexual selection, as indicated by mating systems, and the degree of male-biased size dimorphism. The degree of sexual selection is also positively correlated with male and female size across mammals. Further, parallel selection pressure on female mass is identified in that age at weaning is significantly higher in more polygynous species, even when correcting for body mass. Also, the reproductive rate is lower for larger females, indicating that fecundity selection selects for smaller females in mammals. Although these patterns hold across mammals as a whole, there is considerable variation across orders.[83]

Biological systems

The majority of mammals have seven cervical vertebrae (bones in the neck). The exceptions are the manatee and the two-toed sloth, which have six, and the three-toed sloth which has nine.[84] All mammalian brains possess a neocortex, a brain region unique to mammals.[85] Placental brains have a corpus callosum, unlike monotremes and marsupials.[86]

Circulatory systems

The mammalian heart has four chambers, two upper atria, the receiving chambers, and two lower ventricles, the discharging chambers.[87] The heart has four valves, which separate its chambers and ensures blood flows in the correct direction through the heart (preventing backflow). After gas exchange in the pulmonary capillaries (blood vessels in the lungs), oxygen-rich blood returns to the left atrium via one of the four pulmonary veins. Blood flows nearly continuously back into the atrium, which acts as the receiving chamber, and from here through an opening into the left ventricle. Most blood flows passively into the heart while both the atria and ventricles are relaxed, but toward the end of the ventricular relaxation period, the left atrium will contract, pumping blood into the ventricle. The heart also requires nutrients and oxygen found in blood like other muscles, and is supplied via coronary arteries.[88]

Respiratory systems

The lungs of mammals are spongy and honeycombed. Breathing is mainly achieved with the diaphragm, which divides the thorax from the abdominal cavity, forming a dome convex to the thorax. Contraction of the diaphragm flattens the dome, increasing the volume of the lung cavity. Air enters through the oral and nasal cavities, and travels through the larynx, trachea and bronchi, and expands the alveoli. Relaxing the diaphragm has the opposite effect, decreasing the volume of the lung cavity, causing air to be pushed out of the lungs. During exercise, the abdominal wall contracts, increasing pressure on the diaphragm, which forces air out quicker and more forcefully. The rib cage is able to expand and contract the chest cavity through the action of other respiratory muscles. Consequently, air is sucked into or expelled out of the lungs, always moving down its pressure gradient.[89][90] This type of lung is known as a bellows lung due to its resemblance to blacksmith bellows.[90]

Integumentary systems

The integumentary system (skin) is made up of three layers: the outermost epidermis, the dermis and the hypodermis. The epidermis is typically 10 to 30 cells thick; its main function is to provide a waterproof layer. Its outermost cells are constantly lost; its bottommost cells are constantly dividing and pushing upward. The middle layer, the dermis, is 15 to 40 times thicker than the epidermis. The dermis is made up of many components, such as bony structures and blood vessels. The hypodermis is made up of adipose tissue, which stores lipids and provides cushioning and insulation. The thickness of this layer varies widely from species to species;[91]: 97 marine mammals require a thick hypodermis (blubber) for insulation, and right whales have the thickest blubber at 20 inches (51 cm).[92] Although other animals have features such as whiskers, feathers, setae, or cilia that superficially resemble it, no animals other than mammals have hair. It is a definitive characteristic of the class, though some mammals have very little.[91]: 61

Digestive systems

Herbivores have developed a diverse range of physical structures to facilitate the consumption of plant material. To break up intact plant tissues, mammals have developed teeth structures that reflect their feeding preferences. For instance, frugivores (animals that feed primarily on fruit) and herbivores that feed on soft foliage have low-crowned teeth specialized for grinding foliage and seeds. Grazing animals that tend to eat hard, silica-rich grasses, have high-crowned teeth, which are capable of grinding tough plant tissues and do not wear down as quickly as low-crowned teeth.[93] Most carnivorous mammals have carnassialiforme teeth (of varying length depending on diet), long canines and similar tooth replacement patterns.[94]

The stomach of even-toed ungulates (Artiodactyla) is divided into four sections: the rumen, the reticulum, the omasum and the abomasum (only ruminants have a rumen). After the plant material is consumed, it is mixed with saliva in the rumen and reticulum and separates into solid and liquid material. The solids lump together to form a bolus (or cud), and is regurgitated. When the bolus enters the mouth, the fluid is squeezed out with the tongue and swallowed again. Ingested food passes to the rumen and reticulum where cellulolytic microbes (bacteria, protozoa and fungi) produce cellulase, which is needed to break down the cellulose in plants.[95] Perissodactyls, in contrast to the ruminants, store digested food that has left the stomach in an enlarged cecum, where it is fermented by bacteria.[96] Carnivora have a simple stomach adapted to digest primarily meat, as compared to the elaborate digestive systems of herbivorous animals, which are necessary to break down tough, complex plant fibers. The caecum is either absent or short and simple, and the large intestine is not sacculated or much wider than the small intestine.[97]

Excretory and genitourinary systems

The mammalian excretory system involves many components. Like most other land animals, mammals are ureotelic, and convert ammonia into urea, which is done by the liver as part of the urea cycle.[98] Bilirubin, a waste product derived from blood cells, is passed through bile and urine with the help of enzymes excreted by the liver.[99] The passing of bilirubin via bile through the intestinal tract gives mammalian feces a distinctive brown coloration.[100] Distinctive features of the mammalian kidney include the presence of the renal pelvis and renal pyramids, and of a clearly distinguishable cortex and medulla, which is due to the presence of elongated loops of Henle. Only the mammalian kidney has a bean shape, although there are some exceptions, such as the multilobed reniculate kidneys of pinnipeds, cetaceans and bears.[101][102] Most adult placental mammals have no remaining trace of the cloaca. In the embryo, the embryonic cloaca divides into a posterior region that becomes part of the anus, and an anterior region that has different fates depending on the sex of the individual: in females, it develops into the vestibule or urogenital sinus that receives the urethra and vagina, while in males it forms the entirety of the penile urethra.[102][103] However, the tenrecs, golden moles, and some shrews retain a cloaca as adults.[104] In marsupials, the genital tract is separate from the anus, but a trace of the original cloaca does remain externally.[102] Monotremes, which translates from Greek into "single hole", have a true cloaca.[105] Urine flows from the ureters into the cloaca in monotremes and into the bladder in placental mammals.[102]

Sound production

As in all other tetrapods, mammals have a larynx that can quickly open and close to produce sounds, and a supralaryngeal vocal tract which filters this sound. The lungs and surrounding musculature provide the air stream and pressure required to phonate. The larynx controls the pitch and volume of sound, but the strength the lungs exert to exhale also contributes to volume. More primitive mammals, such as the echidna, can only hiss, as sound is achieved solely through exhaling through a partially closed larynx. Other mammals phonate using vocal folds. The movement or tenseness of the vocal folds can result in many sounds such as purring and screaming. Mammals can change the position of the larynx, allowing them to breathe through the nose while swallowing through the mouth, and to form both oral and nasal sounds; nasal sounds, such as a dog whine, are generally soft sounds, and oral sounds, such as a dog bark, are generally loud.[106]

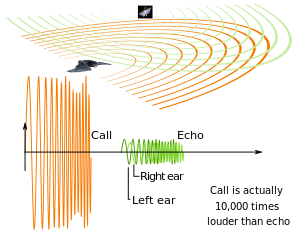

Some mammals have a large larynx and thus a low-pitched voice, namely the hammer-headed bat (Hypsignathus monstrosus) where the larynx can take up the entirety of the thoracic cavity while pushing the lungs, heart, and trachea into the abdomen.[107] Large vocal pads can also lower the pitch, as in the low-pitched roars of big cats.[108] The production of infrasound is possible in some mammals such as the African elephant (Loxodonta spp.) and baleen whales.[109][110] Small mammals with small larynxes have the ability to produce ultrasound, which can be detected by modifications to the middle ear and cochlea. Ultrasound is inaudible to birds and reptiles, which might have been important during the Mesozoic, when birds and reptiles were the dominant predators. This private channel is used by some rodents in, for example, mother-to-pup communication, and by bats when echolocating. Toothed whales also use echolocation, but, as opposed to the vocal membrane that extends upward from the vocal folds, they have a melon to manipulate sounds. Some mammals, namely the primates, have air sacs attached to the larynx, which may function to lower the resonances or increase the volume of sound.[106]

The vocal production system is controlled by the cranial nerve nuclei in the brain, and supplied by the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the superior laryngeal nerve, branches of the vagus nerve. The vocal tract is supplied by the hypoglossal nerve and facial nerves. Electrical stimulation of the periaqueductal gray (PEG) region of the mammalian midbrain elicit vocalizations. The ability to learn new vocalizations is only exemplified in humans, seals, cetaceans, elephants and possibly bats; in humans, this is the result of a direct connection between the motor cortex, which controls movement, and the motor neurons in the spinal cord.[106]

Fur

The primary function of the fur of mammals is thermoregulation. Others include protection, sensory purposes, waterproofing, and camouflage.[111] Different types of fur serve different purposes:[91]: 99

- Definitive – which may be shed after reaching a certain length

- Vibrissae – sensory hairs, most commonly whiskers

- Pelage – guard hairs, under-fur, and awn hair

- Spines – stiff guard hair used for defense (such as in porcupines)

- Bristles – long hairs usually used in visual signals. (such as a lion's mane)

- Velli – often called "down fur" which insulates newborn mammals

- Wool – long, soft and often curly

Thermoregulation

Hair length is not a factor in thermoregulation: for example, some tropical mammals such as sloths have the same length of fur length as some arctic mammals but with less insulation; and, conversely, other tropical mammals with short hair have the same insulating value as arctic mammals. The denseness of fur can increase an animal's insulation value, and arctic mammals especially have dense fur; for example, the musk ox has guard hairs measuring 30 cm (12 in) as well as a dense underfur, which forms an airtight coat, allowing them to survive in temperatures of −40 °C (−40 °F).[91]: 162–163 Some desert mammals, such as camels, use dense fur to prevent solar heat from reaching their skin, allowing the animal to stay cool; a camel's fur may reach 70 °C (158 °F) in the summer, but the skin stays at 40 °C (104 °F).[91]: 188 Aquatic mammals, conversely, trap air in their fur to conserve heat by keeping the skin dry.[91]: 162–163

Coloration

Mammalian coats are colored for a variety of reasons, the major selective pressures including camouflage, sexual selection, communication, and thermoregulation. Coloration in both the hair and skin of mammals is mainly determined by the type and amount of melanin; eumelanins for brown and black colors and pheomelanin for a range of yellowish to reddish colors, giving mammals an earth tone.[112][113] Some mammals have more vibrant colors; certain monkeys such mandrills and vervet monkeys, and opossums such as the Mexican mouse opossums and Derby's woolly opossums, have blue skin due to light diffraction in collagen fibers.[114] Many sloths appear green because their fur hosts green algae; this may be a symbiotic relation that affords camouflage to the sloths.[115]

Camouflage is a powerful influence in a large number of mammals, as it helps to conceal individuals from predators or prey.[116] In arctic and subarctic mammals such as the arctic fox (Alopex lagopus), collared lemming (Dicrostonyx groenlandicus), stoat (Mustela erminea), and snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus), seasonal color change between brown in summer and white in winter is driven largely by camouflage.[117] Some arboreal mammals, notably primates and marsupials, have shades of violet, green, or blue skin on parts of their bodies, indicating some distinct advantage in their largely arboreal habitat due to convergent evolution.[114]

Aposematism, warning off possible predators, is the most likely explanation of the black-and-white pelage of many mammals which are able to defend themselves, such as in the foul-smelling skunk and the powerful and aggressive honey badger.[118] Coat color is sometimes sexually dimorphic, as in many primate species.[119] Differences in female and male coat color may indicate nutrition and hormone levels, important in mate selection.[120] Coat color may influence the ability to retain heat, depending on how much light is reflected. Mammals with a darker colored coat can absorb more heat from solar radiation, and stay warmer, and some smaller mammals, such as voles, have darker fur in the winter. The white, pigmentless fur of arctic mammals, such as the polar bear, may reflect more solar radiation directly onto the skin.[91]: 166–167 [111] The dazzling black-and-white striping of zebras appear to provide some protection from biting flies.[121]

Reproductive system

Mammals are solely gonochoric (an animal is born with either male or female genitalia, as opposed to hermaphrodites where there is no such schism).[122] The penis is used both for urination and copulation in male placentals[123] and marsupials.[124] Depending on the species, an erection may be fueled by blood flow into vascular, spongy tissue or by muscular action. A penis may be contained in a prepuce when not erect, and some placentals also have a penis bone (baculum).[125] Marsupials typically have forked penises,[126] while the echidna penis generally has four heads with only two functioning.[127] The testicles of most mammals descend into the scrotum which is typically posterior to the penis but is often anterior in marsupials. Female mammals generally have a vulva (clitoris and labia) on the outside, while the internal system contains paired oviducts, 1–2 uteri, 1–2 cervices and a vagina.[128][129] Marsupials have two lateral vaginas and a medial vagina. The "vagina" of monotremes is better understood as a "urogenital sinus". The uterine systems of placental mammals can vary between a duplex, where there are two uteri and cervices which open into the vagina, a bipartite, where two uterine horns have a single cervix that connects to the vagina, a bicornuate, which consists where two uterine horns that are connected distally but separate medially creating a Y-shape, and a simplex, which has a single uterus.[130][131][91]: 220–221, 247

The ancestral condition for mammal reproduction is the birthing of relatively undeveloped young, either through direct vivipary or a short period as soft-shelled eggs. This is likely due to the fact that the torso could not expand due to the presence of epipubic bones. The oldest demonstration of this reproductive style is with Kayentatherium, which produced undeveloped perinates, but at much higher litter sizes than any modern mammal, 38 specimens.[132] Most modern mammals are viviparous, giving birth to live young. However, the five species of monotreme, the platypus and the four species of echidna, lay eggs. The monotremes have a sex-determination system different from that of most other mammals.[133] In particular, the sex chromosomes of a platypus are more like those of a chicken than those of a therian mammal.[134]

Viviparous mammals are in the subclass Theria; those living today are in the marsupial and placental infraclasses. Marsupials have a short gestation period, typically shorter than its estrous cycle and generally giving birth to a number of undeveloped newborns that then undergo further development; in many species, this takes place within a pouch-like sac, the marsupium, located in the front of the mother's abdomen. This is the plesiomorphic condition among viviparous mammals; the presence of epipubic bones in all non-placental mammals prevents the expansion of the torso needed for full pregnancy.[82] Even non-placental eutherians probably reproduced this way.[44] The placentals give birth to relatively complete and developed young, usually after long gestation periods.[135] They get their name from the placenta, which connects the developing fetus to the uterine wall to allow nutrient uptake.[136] In placental mammals, the epipubic is either completely lost or converted into the baculum; allowing the torso to be able to expand and thus birth developed offspring.[132]

The mammary glands of mammals are specialized to produce milk, the primary source of nutrition for newborns. The monotremes branched early from other mammals and do not have the teats seen in most mammals, but they do have mammary glands. The young lick the milk from a mammary patch on the mother's belly.[137] Compared to placental mammals, the milk of marsupials changes greatly in both production rate and in nutrient composition, due to the underdeveloped young. In addition, the mammary glands have more autonomy allowing them to supply separate milks to young at different development stages.[138] Lactose is the main sugar in placental mammal milk while monotreme and marsupial milk is dominated by oligosaccharides.[139] Weaning is the process in which a mammal becomes less dependent on their mother's milk and more on solid food.[140]

Endothermy

Nearly all mammals are endothermic ("warm-blooded"). Most mammals also have hair to help keep them warm. Like birds, mammals can forage or hunt in weather and climates too cold for ectothermic ("cold-blooded") reptiles and insects. Endothermy requires plenty of food energy, so mammals eat more food per unit of body weight than most reptiles.[141] Small insectivorous mammals eat prodigious amounts for their size. A rare exception, the naked mole-rat produces little metabolic heat, so it is considered an operational poikilotherm.[142] Birds are also endothermic, so endothermy is not unique to mammals.[143]

Species lifespan

Among mammals, species maximum lifespan varies significantly (for example the shrew has a lifespan of two years, whereas the oldest bowhead whale is recorded to be 211 years).[144] Although the underlying basis for these lifespan differences is still uncertain, numerous studies indicate that the ability to repair DNA damage is an important determinant of mammalian lifespan. In a 1974 study by Hart and Setlow,[145] it was found that DNA excision repair capability increased systematically with species lifespan among seven mammalian species. Species lifespan was observed to be robustly correlated with the capacity to recognize DNA double-strand breaks as well as the level of the DNA repair protein Ku80.[144] In a study of the cells from sixteen mammalian species, genes employed in DNA repair were found to be up-regulated in the longer-lived species.[146] The cellular level of the DNA repair enzyme poly ADP ribose polymerase was found to correlate with species lifespan in a study of 13 mammalian species.[147] Three additional studies of a variety of mammalian species also reported a correlation between species lifespan and DNA repair capability.[148][149][150]

Locomotion

Terrestrial

Most vertebrates—the amphibians, the reptiles and some mammals such as humans and bears—are plantigrade, walking on the whole of the underside of the foot. Many mammals, such as cats and dogs, are digitigrade, walking on their toes, the greater stride length allowing more speed. Some animals such as horses are unguligrade, walking on the tips of their toes. This even further increases their stride length and thus their speed.[151] A few mammals, namely the great apes, are also known to walk on their knuckles, at least for their front legs. Giant anteaters[152] and platypuses[153] are also knuckle-walkers. Some mammals are bipeds, using only two limbs for locomotion, which can be seen in, for example, humans and the great apes. Bipedal species have a larger field of vision than quadrupeds, conserve more energy and have the ability to manipulate objects with their hands, which aids in foraging. Instead of walking, some bipeds hop, such as kangaroos and kangaroo rats.[154][155]

Animals will use different gaits for different speeds, terrain and situations. For example, horses show four natural gaits, the slowest horse gait is the walk, then there are three faster gaits which, from slowest to fastest, are the trot, the canter and the gallop. Animals may also have unusual gaits that are used occasionally, such as for moving sideways or backwards. For example, the main human gaits are bipedal walking and running, but they employ many other gaits occasionally, including a four-legged crawl in tight spaces.[156] Mammals show a vast range of gaits, the order that they place and lift their appendages in locomotion. Gaits can be grouped into categories according to their patterns of support sequence. For quadrupeds, there are three main categories: walking gaits, running gaits and leaping gaits.[157] Walking is the most common gait, where some feet are on the ground at any given time, and found in almost all legged animals. Running is considered to occur when at some points in the stride all feet are off the ground in a moment of suspension.[156]

Arboreal

Arboreal animals frequently have elongated limbs that help them cross gaps, reach fruit or other resources, test the firmness of support ahead and, in some cases, to brachiate (swing between trees).[158] Many arboreal species, such as tree porcupines, silky anteaters, spider monkeys, and possums, use prehensile tails to grasp branches. In the spider monkey, the tip of the tail has either a bare patch or adhesive pad, which provides increased friction. Claws can be used to interact with rough substrates and reorient the direction of forces the animal applies. This is what allows squirrels to climb tree trunks that are so large to be essentially flat from the perspective of such a small animal. However, claws can interfere with an animal's ability to grasp very small branches, as they may wrap too far around and prick the animal's own paw. Frictional gripping is used by primates, relying upon hairless fingertips. Squeezing the branch between the fingertips generates frictional force that holds the animal's hand to the branch. However, this type of grip depends upon the angle of the frictional force, thus upon the diameter of the branch, with larger branches resulting in reduced gripping ability. To control descent, especially down large diameter branches, some arboreal animals such as squirrels have evolved highly mobile ankle joints that permit rotating the foot into a 'reversed' posture. This allows the claws to hook into the rough surface of the bark, opposing the force of gravity. Small size provides many advantages to arboreal species: such as increasing the relative size of branches to the animal, lower center of mass, increased stability, lower mass (allowing movement on smaller branches) and the ability to move through more cluttered habitat.[158] Size relating to weight affects gliding animals such as the sugar glider.[159] Some species of primate, bat and all species of sloth achieve passive stability by hanging beneath the branch. Both pitching and tipping become irrelevant, as the only method of failure would be losing their grip.[158]

Aerial

Bats are the only mammals that can truly fly. They fly through the air at a constant speed by moving their wings up and down (usually with some fore-aft movement as well). Because the animal is in motion, there is some airflow relative to its body which, combined with the velocity of the wings, generates a faster airflow moving over the wing. This generates a lift force vector pointing forwards and upwards, and a drag force vector pointing rearwards and upwards. The upwards components of these counteract gravity, keeping the body in the air, while the forward component provides thrust to counteract both the drag from the wing and from the body as a whole.[160]

The wings of bats are much thinner and consist of more bones than those of birds, allowing bats to maneuver more accurately and fly with more lift and less drag.[161][162] By folding the wings inwards towards their body on the upstroke, they use 35% less energy during flight than birds.[163] The membranes are delicate, ripping easily; however, the tissue of the bat's membrane is able to regrow, such that small tears can heal quickly.[164] The surface of their wings is equipped with touch-sensitive receptors on small bumps called Merkel cells, also found on human fingertips. These sensitive areas are different in bats, as each bump has a tiny hair in the center, making it even more sensitive and allowing the bat to detect and collect information about the air flowing over its wings, and to fly more efficiently by changing the shape of its wings in response.[165]

Fossorial and subterranean

A fossorial (from Latin fossor, meaning "digger") is an animal adapted to digging which lives primarily, but not solely, underground. Some examples are badgers, and naked mole-rats. Many rodent species are also considered fossorial because they live in burrows for most but not all of the day. Species that live exclusively underground are subterranean, and those with limited adaptations to a fossorial lifestyle sub-fossorial. Some organisms are fossorial to aid in temperature regulation while others use the underground habitat for protection from predators or for food storage.[166]

Fossorial mammals have a fusiform body, thickest at the shoulders and tapering off at the tail and nose. Unable to see in the dark burrows, most have degenerated eyes, but degeneration varies between species; pocket gophers, for example, are only semi-fossorial and have very small yet functional eyes, in the fully fossorial marsupial mole the eyes are degenerated and useless, talpa moles have vestigial eyes and the cape golden mole has a layer of skin covering the eyes. External ears flaps are also very small or absent. Truly fossorial mammals have short, stout legs as strength is more important than speed to a burrowing mammal, but semi-fossorial mammals have cursorial legs. The front paws are broad and have strong claws to help in loosening dirt while excavating burrows, and the back paws have webbing, as well as claws, which aids in throwing loosened dirt backwards. Most have large incisors to prevent dirt from flying into their mouth.[167]

Many fossorial mammals such as shrews, hedgehogs, and moles were classified under the now obsolete order Insectivora.[168]

Aquatic

Fully aquatic mammals, the cetaceans and sirenians, have lost their legs and have a tail fin to propel themselves through the water. Flipper movement is continuous. Whales swim by moving their tail fin and lower body up and down, propelling themselves through vertical movement, while their flippers are mainly used for steering. Their skeletal anatomy allows them to be fast swimmers. Most species have a dorsal fin to prevent themselves from turning upside-down in the water.[169][170] The flukes of sirenians are raised up and down in long strokes to move the animal forward, and can be twisted to turn. The forelimbs are paddle-like flippers which aid in turning and slowing.[171]

Semi-aquatic mammals, like pinnipeds, have two pairs of flippers on the front and back, the fore-flippers and hind-flippers. The elbows and ankles are enclosed within the body.[172][173] Pinnipeds have several adaptions for reducing drag. In addition to their streamlined bodies, they have smooth networks of muscle bundles in their skin that may increase laminar flow and make it easier for them to slip through water. They also lack arrector pili, so their fur can be streamlined as they swim.[174] They rely on their fore-flippers for locomotion in a wing-like manner similar to penguins and sea turtles.[175] Fore-flipper movement is not continuous, and the animal glides between each stroke.[173] Compared to terrestrial carnivorans, the fore-limbs are reduced in length, which gives the locomotor muscles at the shoulder and elbow joints greater mechanical advantage;[172] the hind-flippers serve as stabilizers.[174] Other semi-aquatic mammals include beavers, hippopotamuses, otters and platypuses.[176] Hippos are very large semi-aquatic mammals, and their barrel-shaped bodies have graviportal skeletal structures,[177] adapted to carrying their enormous weight, and their specific gravity allows them to sink and move along the bottom of a river.[178]

Behavior

Communication and vocalization

Many mammals communicate by vocalizing. Vocal communication serves many purposes, including in mating rituals, as warning calls,[180] to indicate food sources, and for social purposes. Males often call during mating rituals to ward off other males and to attract females, as in the roaring of lions and red deer.[181] The songs of the humpback whale may be signals to females;[182] they have different dialects in different regions of the ocean.[183] Social vocalizations include the territorial calls of gibbons, and the use of frequency in greater spear-nosed bats to distinguish between groups.[184] The vervet monkey gives a distinct alarm call for each of at least four different predators, and the reactions of other monkeys vary according to the call. For example, if an alarm call signals a python, the monkeys climb into the trees, whereas the eagle alarm causes monkeys to seek a hiding place on the ground.[179] Prairie dogs similarly have complex calls that signal the type, size, and speed of an approaching predator.[185] Elephants communicate socially with a variety of sounds including snorting, screaming, trumpeting, roaring and rumbling. Some of the rumbling calls are infrasonic, below the hearing range of humans, and can be heard by other elephants up to 6 miles (9.7 km) away at still times near sunrise and sunset.[186]

Mammals signal by a variety of means. Many give visual anti-predator signals, as when deer and gazelle stot, honestly indicating their fit condition and their ability to escape,[187][188] or when white-tailed deer and other prey mammals flag with conspicuous tail markings when alarmed, informing the predator that it has been detected.[189] Many mammals make use of scent-marking, sometimes possibly to help defend territory, but probably with a range of functions both within and between species.[190][191][192] Microbats and toothed whales including oceanic dolphins vocalize both socially and in echolocation.[193][194][195]

Feeding

To maintain a high constant body temperature is energy expensive—mammals therefore need a nutritious and plentiful diet. While the earliest mammals were probably predators, different species have since adapted to meet their dietary requirements in a variety of ways. Some eat other animals—this is a carnivorous diet (and includes insectivorous diets). Other mammals, called herbivores, eat plants, which contain complex carbohydrates such as cellulose. An herbivorous diet includes subtypes such as granivory (seed eating), folivory (leaf eating), frugivory (fruit eating), nectarivory (nectar eating), gummivory (gum eating) and mycophagy (fungus eating). The digestive tract of an herbivore is host to bacteria that ferment these complex substances, and make them available for digestion, which are either housed in the multichambered stomach or in a large cecum.[95] Some mammals are coprophagous, consuming feces to absorb the nutrients not digested when the food was first ingested.[91]: 131–137 An omnivore eats both prey and plants. Carnivorous mammals have a simple digestive tract because the proteins, lipids and minerals found in meat require little in the way of specialized digestion. Exceptions to this include baleen whales who also house gut flora in a multi-chambered stomach, like terrestrial herbivores.[196]

The size of an animal is also a factor in determining diet type (Allen's rule). Since small mammals have a high ratio of heat-losing surface area to heat-generating volume, they tend to have high energy requirements and a high metabolic rate. Mammals that weigh less than about 18 ounces (510 g; 1.1 lb) are mostly insectivorous because they cannot tolerate the slow, complex digestive process of an herbivore. Larger animals, on the other hand, generate more heat and less of this heat is lost. They can therefore tolerate either a slower collection process (carnivores that feed on larger vertebrates) or a slower digestive process (herbivores).[197] Furthermore, mammals that weigh more than 18 ounces (510 g; 1.1 lb) usually cannot collect enough insects during their waking hours to sustain themselves. The only large insectivorous mammals are those that feed on huge colonies of insects (ants or termites).[198]

Some mammals are omnivores and display varying degrees of carnivory and herbivory, generally leaning in favor of one more than the other. Since plants and meat are digested differently, there is a preference for one over the other, as in bears where some species may be mostly carnivorous and others mostly herbivorous.[200] They are grouped into three categories: mesocarnivory (50–70% meat), hypercarnivory (70% and greater of meat), and hypocarnivory (50% or less of meat). The dentition of hypocarnivores consists of dull, triangular carnassial teeth meant for grinding food. Hypercarnivores, however, have conical teeth and sharp carnassials meant for slashing, and in some cases strong jaws for bone-crushing, as in the case of hyenas, allowing them to consume bones; some extinct groups, notably the Machairodontinae, had saber-shaped canines.[199]

Some physiological carnivores consume plant matter and some physiological herbivores consume meat. From a behavioral aspect, this would make them omnivores, but from the physiological standpoint, this may be due to zoopharmacognosy. Physiologically, animals must be able to obtain both energy and nutrients from plant and animal materials to be considered omnivorous. Thus, such animals are still able to be classified as carnivores and herbivores when they are just obtaining nutrients from materials originating from sources that do not seemingly complement their classification.[201] For example, it is well documented that some ungulates such as giraffes, camels, and cattle, will gnaw on bones to consume particular minerals and nutrients.[202] Also, cats, which are generally regarded as obligate carnivores, occasionally eat grass to regurgitate indigestible material (such as hairballs), aid with hemoglobin production, and as a laxative.[203]

Many mammals, in the absence of sufficient food requirements in an environment, suppress their metabolism and conserve energy in a process known as hibernation.[204] In the period preceding hibernation, larger mammals, such as bears, become polyphagic to increase fat stores, whereas smaller mammals prefer to collect and stash food.[205] The slowing of the metabolism is accompanied by a decreased heart and respiratory rate, as well as a drop in internal temperatures, which can be around ambient temperature in some cases. For example, the internal temperatures of hibernating arctic ground squirrels can drop to −2.9 °C (26.8 °F); however, the head and neck always stay above 0 °C (32 °F).[206] A few mammals in hot environments aestivate in times of drought or extreme heat, for example the fat-tailed dwarf lemur (Cheirogaleus medius).[207]

Drinking

By necessity, terrestrial animals in captivity become accustomed to drinking water, but most free-roaming animals stay hydrated through the fluids and moisture in fresh food,[208] and learn to actively seek foods with high fluid content.[209] When conditions impel them to drink from bodies of water, the methods and motions differ greatly among species.[210]

Cats, canines, and ruminants all lower the neck and lap in water with their powerful tongues.[210] Cats and canines lap up water with the tongue in a spoon-like shape.[211] Canines lap water by scooping it into their mouth with a tongue which has taken the shape of a ladle. However, with cats, only the tip of their tongue (which is smooth) touches the water, and then the cat quickly pulls its tongue back into its mouth which soon closes; this results in a column of liquid being pulled into the cat's mouth, which is then secured by its mouth closing.[212] Ruminants and most other herbivores partially submerge the tip of the mouth in order to draw in water by means of a plunging action with the tongue held straight.[213] Cats drink at a significantly slower pace than ruminants, who face greater natural predation hazards.[210]

Many desert animals do not drink even if water becomes available, but rely on eating succulent plants.[210] In cold and frozen environments, some animals like hares, tree squirrels, and bighorn sheep resort to consuming snow and icicles.[214] In savannas, the drinking method of giraffes has been a source of speculation for its apparent defiance of gravity; the most recent theory contemplates the animal's long neck functions like a plunger pump.[215] Uniquely, elephants draw water into their trunks and squirt it into their mouths.[210]Intelligence

In intelligent mammals, such as primates, the cerebrum is larger relative to the rest of the brain. Intelligence itself is not easy to define, but indications of intelligence include the ability to learn, matched with behavioral flexibility. Rats, for example, are considered to be highly intelligent, as they can learn and perform new tasks, an ability that may be important when they first colonize a fresh habitat. In some mammals, food gathering appears to be related to intelligence: a deer feeding on plants has a brain smaller than a cat, which must think to outwit its prey.[198]

Tool use by animals may indicate different levels of learning and cognition. The sea otter uses rocks as essential and regular parts of its foraging behaviour (smashing abalone from rocks or breaking open shells), with some populations spending 21% of their time making tools.[216] Other tool use, such as chimpanzees using twigs to "fish" for termites, may be developed by watching others use tools and may even be a true example of animal teaching.[217] Tools may even be used in solving puzzles in which the animal appears to experience a "Eureka moment".[218] Other mammals that do not use tools, such as dogs, can also experience a Eureka moment.[219]

Brain size was previously considered a major indicator of the intelligence of an animal. Since most of the brain is used for maintaining bodily functions, greater ratios of brain to body mass may increase the amount of brain mass available for more complex cognitive tasks. Allometric analysis indicates that mammalian brain size scales at approximately the 2⁄3 or 3⁄4 exponent of the body mass. Comparison of a particular animal's brain size with the expected brain size based on such allometric analysis provides an encephalisation quotient that can be used as another indication of animal intelligence.[220] Sperm whales have the largest brain mass of any animal on earth, averaging 8,000 cubic centimetres (490 cu in) and 7.8 kilograms (17 lb) in mature males.[221]

Self-awareness appears to be a sign of abstract thinking. Self-awareness, although not well-defined, is believed to be a precursor to more advanced processes such as metacognitive reasoning. The traditional method for measuring this is the mirror test, which determines if an animal possesses the ability of self-recognition.[222] Mammals that have passed the mirror test include Asian elephants (some pass, some do not);[223] chimpanzees;[224] bonobos;[225] orangutans;[226] humans, from 18 months (mirror stage);[227] common bottlenose dolphins;[a][228] orcas;[229] and false killer whales.[229]

Social structure

Eusociality is the highest level of social organization. These societies have an overlap of adult generations, the division of reproductive labor and cooperative caring of young. Usually insects, such as bees, ants and termites, have eusocial behavior, but it is demonstrated in two rodent species: the naked mole-rat[230] and the Damaraland mole-rat.[231]

Presociality is when animals exhibit more than just sexual interactions with members of the same species, but fall short of qualifying as eusocial. That is, presocial animals can display communal living, cooperative care of young, or primitive division of reproductive labor, but they do not display all of the three essential traits of eusocial animals. Humans and some species of Callitrichidae (marmosets and tamarins) are unique among primates in their degree of cooperative care of young.[232] Harry Harlow set up an experiment with rhesus monkeys, presocial primates, in 1958; the results from this study showed that social encounters are necessary in order for the young monkeys to develop both mentally and sexually.[233]

A fission–fusion society is a society that changes frequently in its size and composition, making up a permanent social group called the "parent group". Permanent social networks consist of all individual members of a community and often varies to track changes in their environment. In a fission–fusion society, the main parent group can fracture (fission) into smaller stable subgroups or individuals to adapt to environmental or social circumstances. For example, a number of males may break off from the main group in order to hunt or forage for food during the day, but at night they may return to join (fusion) the primary group to share food and partake in other activities. Many mammals exhibit this, such as primates (for example orangutans and spider monkeys),[234] elephants,[235] spotted hyenas,[236] lions,[237] and dolphins.[238]

Solitary animals defend a territory and avoid social interactions with the members of its species, except during breeding season. This is to avoid resource competition, as two individuals of the same species would occupy the same niche, and to prevent depletion of food.[239] A solitary animal, while foraging, can also be less conspicuous to predators or prey.[240]

In a hierarchy, individuals are either dominant or submissive. A despotic hierarchy is where one individual is dominant while the others are submissive, as in wolves and lemurs,[241] and a pecking order is a linear ranking of individuals where there is a top individual and a bottom individual. Pecking orders may also be ranked by sex, where the lowest individual of a sex has a higher ranking than the top individual of the other sex, as in hyenas.[242] Dominant individuals, or alphas, have a high chance of reproductive success, especially in harems where one or a few males (resident males) have exclusive breeding rights to females in a group.[243] Non-resident males can also be accepted in harems, but some species, such as the common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus), may be more strict.[244]

Some mammals are perfectly monogamous, meaning that they mate for life and take no other partners (even after the original mate's death), as with wolves, Eurasian beavers, and otters.[245][246] There are three types of polygamy: either one or multiple dominant males have breeding rights (polygyny), multiple males that females mate with (polyandry), or multiple males have exclusive relations with multiple females (polygynandry). It is much more common for polygynous mating to happen, which, excluding leks, are estimated to occur in up to 90% of mammals.[247] Lek mating occurs when males congregate around females and try to attract them with various courtship displays and vocalizations, as in harbor seals.[248]

All higher mammals (excluding monotremes) share two major adaptations for care of the young: live birth and lactation. These imply a group-wide choice of a degree of parental care. They may build nests and dig burrows to raise their young in, or feed and guard them often for a prolonged period of time. Many mammals are K-selected, and invest more time and energy into their young than do r-selected animals. When two animals mate, they both share an interest in the success of the offspring, though often to different extremes. Mammalian females exhibit some degree of maternal aggression, another example of parental care, which may be targeted against other females of the species or the young of other females; however, some mammals may "aunt" the infants of other females, and care for them. Mammalian males may play a role in child rearing, as with tenrecs, however this varies species to species, even within the same genus. For example, the males of the southern pig-tailed macaque (Macaca nemestrina) do not participate in child care, whereas the males of the Japanese macaque (M. fuscata) do.[249]

Humans and other mammals

В человеческой культуре

Нечеловеческие млекопитающие играют самые разнообразные роли в человеческой культуре. Они являются самыми популярными домашними животными : десятки миллионов собак, кошек и других животных, включая кроликов и мышей, содержатся семьями по всему миру. [250] [251] [252] Млекопитающие, такие как мамонты , лошади и олени, являются одними из самых ранних предметов искусства, их можно найти в верхнего палеолита, наскальных рисунках таких как в Ласко . [253] Крупные художники, такие как Альбрехт Дюрер , Джордж Стаббс и Эдвин Ландсир, известны своими портретами млекопитающих. [254] На многие виды млекопитающих охотились ради развлечения и ради еды; Олени и кабаны особенно популярны в качестве охотничьих животных . [255] [256] [257] Млекопитающие, такие как лошади и собаки, широко участвуют в спортивных гонках, часто в сочетании со ставками на результат . [258] [259] Существует противоречие между ролью животных как товарищей по отношению к человеку и их существованием как личностей с собственными правами . [260] Млекопитающие также играют самые разнообразные роли в литературе. [261] [262] [263] фильм, [264] мифология и религия. [265] [266] [267]

Использование и важность

Одомашнивание млекопитающих сыграло важную роль в развитии сельского хозяйства и цивилизации в эпоху неолита , заставив фермеров заменить охотников-собирателей по всему миру. [б] [269] Этот переход от охоты и собирательства к выпасу стад и выращиванию сельскохозяйственных культур стал важным шагом в истории человечества. Новая сельскохозяйственная экономика, основанная на одомашненных млекопитающих, вызвала «радикальную реструктуризацию человеческого общества, глобальные изменения в биоразнообразии и значительные изменения в формах рельефа Земли и ее атмосфере... важные результаты». [270]

Домашние млекопитающие составляют большую часть поголовья скота , выращиваемого на мясо во всем мире. В их число входят (2009 г.) около 1,4 миллиарда крупного рогатого скота , 1 миллиард овец , 1 миллиард домашних свиней , [271] [272] и (1985) более 700 миллионов кроликов. [273] Рабочие домашние животные, включая крупный рогатый скот и лошадей, использовались для работы и транспорта с самого начала сельского хозяйства, их численность сокращается с появлением механизированного транспорта и сельскохозяйственных машин . В 2004 году они по-прежнему обеспечивали около 80% электроэнергии преимущественно мелких ферм в странах третьего мира и около 20% мирового транспорта, опять же в основном в сельских районах. В горных районах, непригодных для колесного транспорта, вьючные животные . грузы продолжают перевозить [274] Из шкур млекопитающих делают кожу для обуви , одежды и обивки . Шерсть млекопитающих, включая овец, коз и альпак, веками использовалась для изготовления одежды. [275] [276]

Млекопитающие играют важную роль в науке в качестве экспериментальных животных , как в фундаментальных биологических исследованиях, таких как генетика, так и в области генетики. [278] и в разработке новых лекарств, которые должны быть тщательно протестированы, чтобы продемонстрировать их безопасность . [279] используются миллионы млекопитающих, особенно мышей и крыс. в экспериментах Ежегодно [280] — Нокаутная мышь это генетически модифицированная мышь с инактивированным геном , замененным или разрушенным искусственным участком ДНК. Они позволяют изучать секвенированные гены, функции которых неизвестны. [281] Небольшой процент млекопитающих — это приматы, не относящиеся к человеку, которые используются в исследованиях из-за их сходства с людьми. [282] [283] [284]

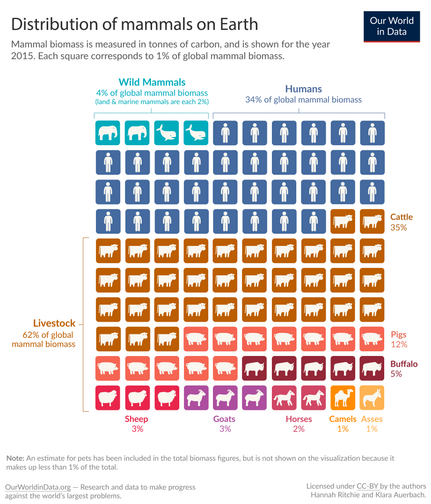

Несмотря на пользу, которую одомашненные млекопитающие принесли для развития человечества, люди оказывают все более пагубное воздействие на диких млекопитающих во всем мире. Подсчитано, что масса всех диких млекопитающих сократилась до 4% от всех млекопитающих, при этом 96% млекопитающих сейчас составляют люди и их домашний скот (см. рисунок). Фактически наземные дикие млекопитающие составляют лишь 2% всех млекопитающих. [285] [286]

Гибриды

Гибриды — это потомство, полученное в результате скрещивания двух генетически различных особей, что обычно приводит к высокой степени гетерозиготности, хотя гибрид и гетерозигота не являются синонимами. Преднамеренная или случайная гибридизация двух или более видов близкородственных животных посредством разведения в неволе — это человеческая деятельность, которая существует на протяжении тысячелетий и развивается в экономических целях. [287] Гибриды между различными подвидами внутри вида (например, между бенгальским тигром и сибирским тигром ) известны как внутривидовые гибриды. Гибриды между разными видами внутри одного рода (например, между львами и тиграми) известны как межвидовые гибриды или скрещивания. Гибриды между разными родами (например, между овцами и козами) известны как межродовые гибриды. [288] Естественные гибриды будут возникать в гибридных зонах , где две популяции видов одного и того же рода или виды, живущие в одних и тех же или соседних областях, будут скрещиваться друг с другом. Некоторые гибриды были признаны видами, например красный волк (хотя это спорный вопрос). [289]

Искусственный отбор , преднамеренное селекционное разведение домашних животных, используется для восстановления недавно вымерших животных в попытке создать породу животных с фенотипом , напоминающим вымершего предка дикого типа . Размножающийся (внутривидовой) гибрид может быть очень похож на вымерший дикий тип по внешнему виду, экологической нише и в некоторой степени генетике, но исходный генофонд этого дикого типа навсегда утрачен с его исчезновением . В результате выведенные породы являются в лучшем случае расплывчатыми двойниками вымерших диких типов, так же как крупный рогатый скот Хека имеет сходство с зубром . [290]

Чистокровные дикие виды, эволюционировавшие в соответствии с определенной экологией, могут оказаться под угрозой исчезновения [291] посредством процесса генетического загрязнения , неконтролируемой гибридизации, интрогрессии генетического затопления, что приводит к гомогенизации или вытеснению гибридных видов из гетерозисных конкуренции . [292] Когда новые популяции завозятся или селективно разводятся людьми, или когда изменение среды обитания приводит к контакту ранее изолированных видов, возможно исчезновение некоторых видов, особенно редких разновидностей. [293] Скрещивание может поглотить более редкий генофонд и создать гибриды, истощая чистокровный генофонд. Например, находящийся под угрозой исчезновения дикий водяной буйвол находится под наибольшей угрозой исчезновения из-за генетического загрязнения домашним водяным буйволом . Такие вымирания не всегда очевидны с морфологической точки зрения. Некоторая степень потока генов является нормальным эволюционным процессом, тем не менее, гибридизация ставит под угрозу существование редких видов. [294] [295]

Угрозы

Утрата видов из экологических сообществ, дефаунация , в первую очередь обусловлена деятельностью человека. [296] Это привело к опустошению лесов , экологическим сообществам, лишенным крупных позвоночных. [297] [298] Во время четвертичного вымирания массовое вымирание представителей мегафауны совпало с появлением людей, что свидетельствует о человеческом влиянии. Одна из гипотез заключается в том, что люди охотились на крупных млекопитающих, таких как шерстистый мамонт , и привели к их исчезновению. [299] [300] 2019 год о глобальной оценке биоразнообразия и экосистемных услуг за В докладе IPBES говорится, что общая биомасса диких млекопитающих сократилась на 82 процента с момента зарождения человеческой цивилизации. [301] [302] Дикие животные составляют всего 4% биомассы млекопитающих на Земле, тогда как люди и их одомашненные животные составляют 96%. [286]