Тестирование на животных

Лабораторная крыса Wistar | |

| Описание | около 50–100 миллионов позвоночных животных. Ежегодно в экспериментах используются |

|---|---|

| Предметы | Тестирование на животных, наука, медицина, защита животных, права животных, этика |

Тестирование на животных , также известное как эксперименты на животных , исследования на животных и in vivo тестирование , представляет собой использование животных, отличных от человека , таких как модельные организмы , в экспериментах, направленных на контроль переменных, влияющих на поведение или биологическую систему изучаемое . Этот подход можно противопоставить полевым исследованиям, в ходе которых за животными наблюдают в их естественной среде или среде обитания. Экспериментальные исследования на животных обычно проводятся в университетах, медицинских школах, фармацевтических компаниях, оборонных учреждениях и коммерческих учреждениях, которые предоставляют отрасли услуги по испытаниям на животных. [1] Фокус испытаний на животных варьируется от чистых исследований , направленных на развитие фундаментальных знаний об организме, до прикладных исследований, которые могут быть сосредоточены на ответах на некоторые вопросы, имеющие большое практическое значение, например, на поиске лекарства от болезни. [2] Примеры прикладных исследований включают тестирование методов лечения заболеваний, селекцию, оборонные исследования и токсикологию , включая тестирование косметики . В сфере образования тестирование на животных иногда является компонентом курсов биологии или психологии. [3]

Research using animal models has been central to most of the achievements of modern medicine.[4][5][6] It has contributed most of the basic knowledge in fields such as human physiology and biochemistry, and has played significant roles in fields such as neuroscience and infectious disease.[7][8] The results have included the near-eradication of polio and the development of organ transplantation, and have benefited both humans and animals.[4][9] From 1910 to 1927, Thomas Hunt Morgan's work with the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster identified chromosomes as the vector of inheritance for genes,[10][11] and Eric Kandel wrote that Morgan's discoveries "helped transform biology into an experimental science".[12] Research in model organisms led to further medical advances, such as the production of the diphtheria antitoxin[13][14] and the 1922 discovery of insulin[15] and its use in treating diabetes, which had previously meant death.[16] Modern general anaesthetics such as halothane were also developed through studies on model organisms, and are necessary for modern, complex surgical operations.[17] Other 20th-century medical advances and treatments that relied on research performed in animals include organ transplant techniques,[18][19][20][21] the heart-lung machine,[22] antibiotics,[23][24] and the whooping cough vaccine.[25]

Animal testing is widely used to research human disease when human experimentation would be unfeasible or unethical.[26] This strategy is made possible by the common descent of all living organisms, and the conservation of metabolic and developmental pathways and genetic material over the course of evolution.[27] Performing experiments in model organisms allows for better understanding the disease process without the added risk of harming an actual human. The species of the model organism is usually chosen so that it reacts to disease or its treatment in a way that resembles human physiology as needed. Biological activity in a model organism does not ensure an effect in humans, and care must be taken when generalizing from one organism to another.[28][page needed] However, many drugs, treatments and cures for human diseases are developed in part with the guidance of animal models.[29][30] Treatments for animal diseases have also been developed, including for rabies,[31] anthrax,[31] glanders,[31] feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV),[32] tuberculosis,[31] Texas cattle fever,[31] classical swine fever (hog cholera),[31] heartworm, and other parasitic infections.[33] Animal experimentation continues to be required for biomedical research,[34] and is used with the aim of solving medical problems such as Alzheimer's disease,[35] AIDS,[36] multiple sclerosis,[37] spinal cord injury, many headaches,[38] and other conditions in which there is no useful in vitro model system available.

The annual use of vertebrate animals—from zebrafish to non-human primates—was estimated at 192 million as of 2015.[39] In the European Union, vertebrate species represent 93% of animals used in research,[39] and 11.5 million animals were used there in 2011.[40] The mouse (Mus musculus) is associated with many important biological discoveries of the 20th and 21st centuries,[41] and by one estimate, the number of mice and rats used in the United States alone in 2001 was 80 million.[42] In 2013, it was reported that mammals (mice and rats), fish, amphibians, and reptiles together accounted for over 85% of research animals.[43] In 2022, a law was passed in the United States that eliminated the FDA requirement that all drugs be tested on animals.[44]

Animal testing is regulated to varying degrees in different countries.[45] Animal testing is regulated differently in different countries: in some cases it is strictly controlled while others have more relaxed regulations. There are ongoing debates about the ethics and necessity of animal testing. Proponents argue that it has led to significant advancements in medicine and other fields while opponents raise concerns about cruelty towards animals and question its effectiveness.[46][47] There are efforts underway to find alternatives to animal testing such as computer simulation models, organs-on-chips technology that mimics human organs for lab tests,[48] microdosing techniques which involve administering small doses of test compounds to volunteers instead of animals for safety tests or drug screenings; positron emission tomography (PET) scans which allow scanning of the human brain without harming humans; comparative epidemiological studies among human populations; simulators and computer programs for teaching purposes; among others.[49][50][51]

Definitions

[edit]The terms animal testing, animal experimentation, animal research, in vivo testing, and vivisection have similar denotations but different connotations. Literally, "vivisection" means "live sectioning" of an animal, and historically referred only to experiments that involved the dissection of live animals. The term is occasionally used to refer pejoratively to any experiment using living animals; for example, the Encyclopædia Britannica defines "vivisection" as: "Operation on a living animal for experimental rather than healing purposes; more broadly, all experimentation on live animals",[52][53][54] although dictionaries point out that the broader definition is "used only by people who are opposed to such work".[55][56] The word has a negative connotation, implying torture, suffering, and death.[57] The word "vivisection" is preferred by those opposed to this research, whereas scientists typically use the term "animal experimentation".[58][59]

The following text excludes as much as possible practices related to in vivo veterinary surgery, which is left to the discussion of vivisection.

History

[edit]

The earliest references to animal testing are found in the writings of the Greeks in the 2nd and 4th centuries BCE. Aristotle and Erasistratus were among the first to perform experiments on living animals.[60] Galen, a 2nd-century Roman physician, performed post-mortem dissections of pigs and goats.[61] Avenzoar, a 12th-century Arabic physician in Moorish Spain introduced an experimental method of testing surgical procedures before applying them to human patients.[62][63] Discoveries in the 18th and 19th centuries included Antoine Lavoisier's use of a guinea pig in a calorimeter to prove that respiration was a form of combustion, and Louis Pasteur's demonstration of the germ theory of disease in the 1880s using anthrax in sheep.[64] Robert Koch used animal testing of mice and guinea pigs to discover the bacteria that cause anthrax and tuberculosis. In the 1890s, Ivan Pavlov famously used dogs to describe classical conditioning.[65]

Research using animal models has been central to most of the achievements of modern medicine.[4][5][6] It has contributed most of the basic knowledge in fields such as human physiology and biochemistry, and has played significant roles in fields such as neuroscience and infectious disease.[7][8] For example, the results have included the near-eradication of polio and the development of organ transplantation, and have benefited both humans and animals.[4][9] From 1910 to 1927, Thomas Hunt Morgan's work with the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster identified chromosomes as the vector of inheritance for genes.[10][11] Drosophila became one of the first, and for some time the most widely used, model organisms,[66] and Eric Kandel wrote that Morgan's discoveries "helped transform biology into an experimental science".[12] D. melanogaster remains one of the most widely used eukaryotic model organisms. During the same time period, studies on mouse genetics in the laboratory of William Ernest Castle in collaboration with Abbie Lathrop led to generation of the DBA ("dilute, brown and non-agouti") inbred mouse strain and the systematic generation of other inbred strains.[67][68] The mouse has since been used extensively as a model organism and is associated with many important biological discoveries of the 20th and 21st centuries.[41]

In the late 19th century, Emil von Behring isolated the diphtheria toxin and demonstrated its effects in guinea pigs. He went on to develop an antitoxin against diphtheria in animals and then in humans, which resulted in the modern methods of immunization and largely ended diphtheria as a threatening disease.[13] The diphtheria antitoxin is famously commemorated in the Iditarod race, which is modeled after the delivery of antitoxin in the 1925 serum run to Nome. The success of animal studies in producing the diphtheria antitoxin has also been attributed as a cause for the decline of the early 20th-century opposition to animal research in the United States.[14]

Subsequent research in model organisms led to further medical advances, such as Frederick Banting's research in dogs, which determined that the isolates of pancreatic secretion could be used to treat dogs with diabetes. This led to the 1922 discovery of insulin (with John Macleod)[15] and its use in treating diabetes, which had previously meant death.[16][69] John Cade's research in guinea pigs discovered the anticonvulsant properties of lithium salts,[70] which revolutionized the treatment of bipolar disorder, replacing the previous treatments of lobotomy or electroconvulsive therapy. Modern general anaesthetics, such as halothane and related compounds, were also developed through studies on model organisms, and are necessary for modern, complex surgical operations.[17][71]

In the 1940s, Jonas Salk used rhesus monkey studies to isolate the most virulent forms of the polio virus,[72] which led to his creation of a polio vaccine. The vaccine, which was made publicly available in 1955, reduced the incidence of polio 15-fold in the United States over the following five years.[73] Albert Sabin improved the vaccine by passing the polio virus through animal hosts, including monkeys; the Sabin vaccine was produced for mass consumption in 1963, and had virtually eradicated polio in the United States by 1965.[74] It has been estimated that developing and producing the vaccines required the use of 100,000 rhesus monkeys, with 65 doses of vaccine produced from each monkey. Sabin wrote in 1992, "Without the use of animals and human beings, it would have been impossible to acquire the important knowledge needed to prevent much suffering and premature death not only among humans, but also among animals."[75]

On 3 November 1957, a Soviet dog, Laika, became the first of many animals to orbit the Earth. In the 1970s, antibiotic treatments and vaccines for leprosy were developed using armadillos,[76] then given to humans.[77] The ability of humans to change the genetics of animals took an enormous step forward in 1974 when Rudolf Jaenisch could produce the first transgenic mammal, by integrating DNA from simians into the genome of mice.[78] This genetic research progressed rapidly and, in 1996, Dolly the sheep was born, the first mammal to be cloned from an adult cell.[79][80]

Other 20th-century medical advances and treatments that relied on research performed in animals include organ transplant techniques,[18][19][20][21] the heart-lung machine,[22] antibiotics,[23][24] and the whooping cough vaccine.[25] Treatments for animal diseases have also been developed, including for rabies,[31] anthrax,[31] glanders,[31] feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV),[32] tuberculosis,[31] Texas cattle fever,[31] classical swine fever (hog cholera),[31] heartworm, and other parasitic infections.[33] Animal experimentation continues to be required for biomedical research,[34] and is used with the aim of solving medical problems such as Alzheimer's disease,[35] AIDS,[36][81][82] multiple sclerosis,[37] spinal cord injury, many headaches,[38] and other conditions in which there is no useful in vitro model system available.

Toxicology testing became important in the 20th century. In the 19th century, laws regulating drugs were more relaxed. For example, in the US, the government could only ban a drug after they had prosecuted a company for selling products that harmed customers. However, in response to the Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster of 1937 in which the eponymous drug killed over 100 users, the US Congress passed laws that required safety testing of drugs on animals before they could be marketed. Other countries enacted similar legislation.[83] In the 1960s, in reaction to the Thalidomide tragedy, further laws were passed requiring safety testing on pregnant animals before a drug can be sold.[84]

Model organisms

[edit]Invertebrates

[edit]

Although many more invertebrates than vertebrates are used in animal testing, these studies are largely unregulated by law. The most frequently used invertebrate species are Drosophila melanogaster, a fruit fly, and Caenorhabditis elegans, a nematode worm. In the case of C. elegans, the worm's body is completely transparent and the precise lineage of all the organism's cells is known,[85] while studies in the fly D. melanogaster can use an amazing array of genetic tools.[86] These invertebrates offer some advantages over vertebrates in animal testing, including their short life cycle and the ease with which large numbers may be housed and studied. However, the lack of an adaptive immune system and their simple organs prevent worms from being used in several aspects of medical research such as vaccine development.[87] Similarly, the fruit fly immune system differs greatly from that of humans,[88] and diseases in insects can be different from diseases in vertebrates;[89] however, fruit flies and waxworms can be useful in studies to identify novel virulence factors or pharmacologically active compounds.[90][91][92]

Several invertebrate systems are considered acceptable alternatives to vertebrates in early-stage discovery screens.[93] Because of similarities between the innate immune system of insects and mammals, insects can replace mammals in some types of studies. Drosophila melanogaster and the Galleria mellonella waxworm have been particularly important for analysis of virulence traits of mammalian pathogens.[90][91] Waxworms and other insects have also proven valuable for the identification of pharmaceutical compounds with favorable bioavailability.[92] The decision to adopt such models generally involves accepting a lower degree of biological similarity with mammals for significant gains in experimental throughput.

Rodents

[edit]

In the U.S., the numbers of rats and mice used is estimated to be from 11 million[94] to between 20 and 100 million a year.[95] Other rodents commonly used are guinea pigs, hamsters, and gerbils. Mice are the most commonly used vertebrate species because of their size, low cost, ease of handling, and fast reproduction rate.[96][97] Mice are widely considered to be the best model of inherited human disease and share 95% of their genes with humans.[96] With the advent of genetic engineering technology, genetically modified mice can be generated to order and can provide models for a range of human diseases.[96] Rats are also widely used for physiology, toxicology and cancer research, but genetic manipulation is much harder in rats than in mice, which limits the use of these rodents in basic science.[98]

Dogs

[edit]

Dogs are widely used in biomedical research, testing, and education—particularly beagles, because they are gentle and easy to handle, and to allow for comparisons with historical data from beagles (a Reduction technique).[99] They are used as models for human and veterinary diseases in cardiology, endocrinology, and bone and joint studies, research that tends to be highly invasive, according to the Humane Society of the United States.[100] The most common use of dogs is in the safety assessment of new medicines[101] for human or veterinary use as a second species following testing in rodents, in accordance with the regulations set out in the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. One of the most significant advancements in medical science involves the use of dogs in developing the answers to insulin production in the body for diabetics and the role of the pancreas in this process. They found that the pancreas was responsible for producing insulin in the body and that removal of the pancreas, resulted in the development of diabetes in the dog. After re-injecting the pancreatic extract (insulin), the blood glucose levels were significantly lowered.[102] The advancements made in this research involving the use of dogs has resulted in a definite improvement in the quality of life for both humans and animals.[citation needed]

The U.S. Department of Agriculture's Animal Welfare Report shows that 60,979 dogs were used in USDA-registered facilities in 2016.[94] In the UK, according to the UK Home Office, there were 3,847 procedures on dogs in 2017.[103] Of the other large EU users of dogs, Germany conducted 3,976 procedures on dogs in 2016[104] and France conducted 4,204 procedures in 2016.[105] In both cases this represents under 0.2% of the total number of procedures conducted on animals in the respective countries.

Zebrafish

[edit]Zebrafish are commonly used for the basic study and development of various cancers. Used to explore the immune system and genetic strains. They are low in cost, small size, fast reproduction rate, and able to observe cancer cells in real time. Humans and zebrafish share neoplasm similarities which is why they are used for research. The National Library of Medicine shows many examples of the types of cancer zebrafish are used in. The use of zebrafish have allowed them to find differences between MYC-driven pre-B vs T-ALL and be exploited to discover novel pre-B ALL therapies on acute lymphocytic leukemia.[106][107]

The National Library of Medicine also explains how a neoplasm is difficult to diagnose at an early stage. Understanding the molecular mechanism of digestive tract tumorigenesis and searching for new treatments is the current research. Zebrafish and humans share similar gastric cancer cells in the gastric cancer xenotransplantation model. This allowed researchers to find that Triphala could inhibit the growth and metastasis of gastric cancer cells. Since zebrafish liver cancer genes are related with humans they have become widely used in liver cancer search, as will as many other cancers.[108]

Non-human primates

[edit]

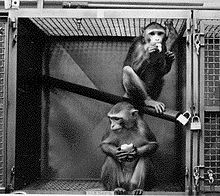

Non-human primates (NHPs) are used in toxicology tests, studies of AIDS and hepatitis, studies of neurology, behavior and cognition, reproduction, genetics, and xenotransplantation. They are caught in the wild or purpose-bred. In the United States and China, most primates are domestically purpose-bred, whereas in Europe the majority are imported purpose-bred.[109] The European Commission reported that in 2011, 6,012 monkeys were experimented on in European laboratories.[110] According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, there were 71,188 monkeys in U.S. laboratories in 2016.[94] 23,465 monkeys were imported into the U.S. in 2014 including 929 who were caught in the wild.[111] Most of the NHPs used in experiments are macaques;[112] but marmosets, spider monkeys, and squirrel monkeys are also used, and baboons and chimpanzees are used in the US. As of 2015[update], there are approximately 730 chimpanzees in U.S. laboratories.[113]

In a survey in 2003, it was found that 89% of singly-housed primates exhibited self-injurious or abnormal stereotypyical behaviors including pacing, rocking, hair pulling, and biting among others.[114]

The first transgenic primate was produced in 2001, with the development of a method that could introduce new genes into a rhesus macaque.[115] This transgenic technology is now being applied in the search for a treatment for the genetic disorder Huntington's disease.[116] Notable studies on non-human primates have been part of the polio vaccine development, and development of Deep Brain Stimulation, and their current heaviest non-toxicological use occurs in the monkey AIDS model, SIV.[117][112][118] In 2008, a proposal to ban all primates experiments in the EU has sparked a vigorous debate.[119]

Other species

[edit]Over 500,000 fish and 9,000 amphibians were used in the UK in 2016.[103] The main species used is the zebrafish, Danio rerio, which are translucent during their embryonic stage, and the African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis. Over 20,000 rabbits were used for animal testing in the UK in 2004.[120] Albino rabbits are used in eye irritancy tests (Draize test) because rabbits have less tear flow than other animals, and the lack of eye pigment in albinos make the effects easier to visualize. The numbers of rabbits used for this purpose has fallen substantially over the past two decades. In 1996, there were 3,693 procedures on rabbits for eye irritation in the UK,[121] and in 2017 this number was just 63.[103] Rabbits are also frequently used for the production of polyclonal antibodies.

Cats are most commonly used in neurological research. In 2016, 18,898 cats were used in the United States alone,[94] around a third of which were used in experiments which have the potential to cause "pain and/or distress"[122] though only 0.1% of cat experiments involved potential pain which was not relieved by anesthetics/analgesics. In the UK, just 198 procedures were carried out on cats in 2017. The number has been around 200 for most of the last decade.[103]

Care and use of animals

[edit]Regulations and laws

[edit]

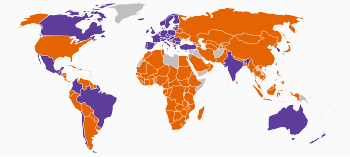

| | Nationwide ban on all cosmetic testing on animals | | Partial ban on cosmetic testing on animals1 |

| | Ban on the sale of cosmetics tested on animals | | No ban on any cosmetic testing on animals |

| | Unknown |

The regulations that apply to animals in laboratories vary across species. In the U.S., under the Animal Welfare Act and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (the Guide), published by the National Academy of Sciences, any procedure can be performed on an animal if it can be successfully argued that it is scientifically justified. Researchers are required to consult with the institution's veterinarian and its Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), which every research facility is obliged to maintain.[123] The IACUC must ensure that alternatives, including non-animal alternatives, have been considered, that the experiments are not unnecessarily duplicative, and that pain relief is given unless it would interfere with the study. The IACUCs regulate all vertebrates in testing at institutions receiving federal funds in the USA. Although the Animal Welfare Act does not include purpose-bred rodents and birds, these species are equally regulated under Public Health Service policies that govern the IACUCs.[124][125] The Public Health Service policy oversees the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC conducts infectious disease research on nonhuman primates, rabbits, mice, and other animals, while FDA requirements cover use of animals in pharmaceutical research.[126] Animal Welfare Act (AWA) regulations are enforced by the USDA, whereas Public Health Service regulations are enforced by OLAW and in many cases by AAALAC.

According to the 2014 U.S. Department of Agriculture Office of the Inspector General (OIG) report—which looked at the oversight of animal use during a three-year period—"some Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees ...did not adequately approve, monitor, or report on experimental procedures on animals". The OIG found that "as a result, animals are not always receiving basic humane care and treatment and, in some cases, pain and distress are not minimized during and after experimental procedures". According to the report, within a three-year period, nearly half of all American laboratories with regulated species were cited for AWA violations relating to improper IACUC oversight.[127] The USDA OIG made similar findings in a 2005 report.[128] With only a broad number of 120 inspectors, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) oversees more than 12,000 facilities involved in research, exhibition, breeding, or dealing of animals.[126] Others have criticized the composition of IACUCs, asserting that the committees are predominantly made up of animal researchers and university representatives who may be biased against animal welfare concerns.[129]

Larry Carbone, a laboratory animal veterinarian, writes that, in his experience, IACUCs take their work very seriously regardless of the species involved, though the use of non-human primates always raises what he calls a "red flag of special concern".[130] A study published in Science magazine in July 2001 confirmed the low reliability of IACUC reviews of animal experiments. Funded by the National Science Foundation, the three-year study found that animal-use committees that do not know the specifics of the university and personnel do not make the same approval decisions as those made by animal-use committees that do know the university and personnel. Specifically, blinded committees more often ask for more information rather than approving studies.[131]

Scientists in India are protesting a recent guideline issued by the University Grants Commission to ban the use of live animals in universities and laboratories.[132]

Numbers

[edit]Accurate global figures for animal testing are difficult to obtain; it has been estimated that 100 million vertebrates are experimented on around the world every year,[133] 10–11 million of them in the EU.[134] The Nuffield Council on Bioethics reports that global annual estimates range from 50 to 100 million animals. None of the figures include invertebrates such as shrimp and fruit flies.[135]

The USDA/APHIS has published the 2016 animal research statistics. Overall, the number of animals (covered by the Animal Welfare Act) used in research in the US rose 6.9% from 767,622 (2015) to 820,812 (2016).[136] This includes both public and private institutions. By comparing with EU data, where all vertebrate species are counted, Speaking of Research estimated that around 12 million vertebrates were used in research in the US in 2016.[94] A 2015 article published in the Journal of Medical Ethics, argued that the use of animals in the US has dramatically increased in recent years. Researchers found this increase is largely the result of an increased reliance on genetically modified mice in animal studies.[137]

In 1995, researchers at Tufts University Center for Animals and Public Policy estimated that 14–21 million animals were used in American laboratories in 1992, a reduction from a high of 50 million used in 1970.[138] In 1986, the U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment reported that estimates of the animals used in the U.S. range from 10 million to upwards of 100 million each year, and that their own best estimate was at least 17 million to 22 million.[139] In 2016, the Department of Agriculture listed 60,979 dogs, 18,898 cats, 71,188 non-human primates, 183,237 guinea pigs, 102,633 hamsters, 139,391 rabbits, 83,059 farm animals, and 161,467 other mammals, a total of 820,812, a figure that includes all mammals except purpose-bred mice and rats. The use of dogs and cats in research in the U.S. decreased from 1973 to 2016 from 195,157 to 60,979, and from 66,165 to 18,898, respectively.[94]

In the UK, Home Office figures show that 3.79 million procedures were carried out in 2017.[140] 2,960 procedures used non-human primates, down over 50% since 1988. A "procedure" refers here to an experiment that might last minutes, several months, or years. Most animals are used in only one procedure: animals are frequently euthanized after the experiment; however death is the endpoint of some procedures.[135]The procedures conducted on animals in the UK in 2017 were categorised as: 43% (1.61 million) sub-threshold, 4% (0.14 million) non-recovery, 36% (1.35 million) mild, 15% (0.55 million) moderate, and 4% (0.14 million) severe.[141] A 'severe' procedure would be, for instance, any test where death is the end-point or fatalities are expected, whereas a 'mild' procedure would be something like a blood test or an MRI scan.[140]

The Three Rs

[edit]The Three Rs (3Rs) are guiding principles for more ethical use of animals in testing. These were first described by W.M.S. Russell and R.L. Burch in 1959.[142] The 3Rs state:

- Replacement which refers to the preferred use of non-animal methods over animal methods whenever it is possible to achieve the same scientific aims. These methods include computer modeling.

- Reduction which refers to methods that enable researchers to obtain comparable levels of information from fewer animals, or to obtain more information from the same number of animals.

- Refinement which refers to methods that alleviate or minimize potential pain, suffering or distress, and enhance animal welfare for the animals used. These methods include non-invasive techniques.[143]

The 3Rs have a broader scope than simply encouraging alternatives to animal testing, but aim to improve animal welfare and scientific quality where the use of animals can not be avoided. These 3Rs are now implemented in many testing establishments worldwide and have been adopted by various pieces of legislation and regulations.[2]

Despite the widespread acceptance of the 3Rs, many countries—including Canada, Australia, Israel, South Korea, and Germany—have reported rising experimental use of animals in recent years with increased use of mice and, in some cases, fish while reporting declines in the use of cats, dogs, primates, rabbits, guinea pigs, and hamsters. Along with other countries, China has also escalated its use of GM animals, resulting in an increase in overall animal use.[144][145][146][147][148][149][excessive citations]

Sources

[edit]Animals used by laboratories are largely supplied by specialist dealers. Sources differ for vertebrate and invertebrate animals. Most laboratories breed and raise flies and worms themselves, using strains and mutants supplied from a few main stock centers.[150] For vertebrates, sources include breeders and dealers like Covance and Charles River Laboratories who supply purpose-bred and wild-caught animals; businesses that trade in wild animals such as Nafovanny; and dealers who supply animals sourced from pounds, auctions, and newspaper ads. Animal shelters also supply the laboratories directly.[151] Large centers also exist to distribute strains of genetically modified animals; the International Knockout Mouse Consortium, for example, aims to provide knockout mice for every gene in the mouse genome.[152]

In the U.S., Class A breeders are licensed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to sell animals for research purposes, while Class B dealers are licensed to buy animals from "random sources" such as auctions, pound seizure, and newspaper ads. Some Class B dealers have been accused of kidnapping pets and illegally trapping strays, a practice known as bunching.[153][154][155][156][157][158] It was in part out of public concern over the sale of pets to research facilities that the 1966 Laboratory Animal Welfare Act was ushered in—the Senate Committee on Commerce reported in 1966 that stolen pets had been retrieved from Veterans Administration facilities, the Mayo Institute, the University of Pennsylvania, Stanford University, and Harvard and Yale Medical Schools.[159] The USDA recovered at least a dozen stolen pets during a raid on a Class B dealer in Arkansas in 2003.[160]

Four states in the U.S.—Minnesota, Utah, Oklahoma, and Iowa—require their shelters to provide animals to research facilities. Fourteen states explicitly prohibit the practice, while the remainder either allow it or have no relevant legislation.[161]

In the European Union, animal sources are governed by Council Directive 86/609/EEC, which requires lab animals to be specially bred, unless the animal has been lawfully imported and is not a wild animal or a stray. The latter requirement may also be exempted by special arrangement.[162] In 2010 the Directive was revised with EU Directive 2010/63/EU.[163] In the UK, most animals used in experiments are bred for the purpose under the 1988 Animal Protection Act, but wild-caught primates may be used if exceptional and specific justification can be established.[164][165] The United States also allows the use of wild-caught primates; between 1995 and 1999, 1,580 wild baboons were imported into the U.S. Over half the primates imported between 1995 and 2000 were handled by Charles River Laboratories, or by Covance, which is the single largest importer of primates into the U.S.[166]

Pain and suffering

[edit]

The extent to which animal testing causes pain and suffering, and the capacity of animals to experience and comprehend them, is the subject of much debate.[167][168]

According to the USDA, in 2016 501,560 animals (61%) (not including rats, mice, birds, or invertebrates) were used in procedures that did not include more than momentary pain or distress. 247,882 (31%) animals were used in procedures in which pain or distress was relieved by anesthesia, while 71,370 (9%) were used in studies that would cause pain or distress that would not be relieved.[94]

The idea that animals might not feel pain as human beings feel it traces back to the 17th-century French philosopher, René Descartes, who argued that animals do not experience pain and suffering because they lack consciousness.[135][169] Bernard Rollin of Colorado State University, the principal author of two U.S. federal laws regulating pain relief for animals,[170] writes that researchers remained unsure into the 1980s as to whether animals experience pain, and that veterinarians trained in the U.S. before 1989 were simply taught to ignore animal pain.[171] In his interactions with scientists and other veterinarians, he was regularly asked to "prove" that animals are conscious, and to provide "scientifically acceptable" grounds for claiming that they feel pain.[171] Carbone writes that the view that animals feel pain differently is now a minority view. Academic reviews of the topic are more equivocal, noting that although the argument that animals have at least simple conscious thoughts and feelings has strong support,[172] some critics continue to question how reliably animal mental states can be determined.[135][173] However, some canine experts are stating that, while intelligence does differ animal to animal, dogs have the intelligence of a two to two-and-a-half-year old. This does support the idea that dogs, at the very least, have some form of consciousness.[174] The ability of invertebrates to experience pain and suffering is less clear, however, legislation in several countries (e.g. U.K., New Zealand,[175] Norway[176]) protects some invertebrate species if they are being used in animal testing.

In the U.S., the defining text on animal welfare regulation in animal testing is the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.[177] This defines the parameters that govern animal testing in the U.S. It states "The ability to experience and respond to pain is widespread in the animal kingdom...Pain is a stressor and, if not relieved, can lead to unacceptable levels of stress and distress in animals." The Guide states that the ability to recognize the symptoms of pain in different species is vital in efficiently applying pain relief and that it is essential for the people caring for and using animals to be entirely familiar with these symptoms. On the subject of analgesics used to relieve pain, the Guide states "The selection of the most appropriate analgesic or anesthetic should reflect professional judgment as to which best meets clinical and humane requirements without compromising the scientific aspects of the research protocol". Accordingly, all issues of animal pain and distress, and their potential treatment with analgesia and anesthesia, are required regulatory issues in receiving animal protocol approval.[178] Currently, traumatic methods of marking laboratory animals are being replaced with non-invasive alternatives.[179][180]

In 2019, Katrien Devolder and Matthias Eggel proposed gene editing research animals to remove the ability to feel pain. This would be an intermediate step towards eventually stopping all experimentation on animals and adopting alternatives.[181] Additionally, this would not stop research animals from experiencing psychological harm.

Euthanasia

[edit]Regulations require that scientists use as few animals as possible, especially for terminal experiments.[182] However, while policy makers consider suffering to be the central issue and see animal euthanasia as a way to reduce suffering, others, such as the RSPCA, argue that the lives of laboratory animals have intrinsic value.[183] Regulations focus on whether particular methods cause pain and suffering, not whether their death is undesirable in itself.[184] The animals are euthanized at the end of studies for sample collection or post-mortem examination; during studies if their pain or suffering falls into certain categories regarded as unacceptable, such as depression, infection that is unresponsive to treatment, or the failure of large animals to eat for five days;[185] or when they are unsuitable for breeding or unwanted for some other reason.[186]

Methods of euthanizing laboratory animals are chosen to induce rapid unconsciousness and death without pain or distress.[187] The methods that are preferred are those published by councils of veterinarians. The animal can be made to inhale a gas, such as carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide, by being placed in a chamber, or by use of a face mask, with or without prior sedation or anesthesia. Sedatives or anesthetics such as barbiturates can be given intravenously, or inhalant anesthetics may be used. Amphibians and fish may be immersed in water containing an anesthetic such as tricaine. Physical methods are also used, with or without sedation or anesthesia depending on the method. Recommended methods include decapitation (beheading) for small rodents or rabbits. Cervical dislocation (breaking the neck or spine) may be used for birds, mice, rats, and rabbits depending on the size and weight of the animal.[188] High-intensity microwave irradiation of the brain can preserve brain tissue and induce death in less than 1 second, but this is currently only used on rodents. Captive bolts may be used, typically on dogs, ruminants, horses, pigs and rabbits. It causes death by a concussion to the brain. Gunshot may be used, but only in cases where a penetrating captive bolt may not be used. Some physical methods are only acceptable after the animal is unconscious. Electrocution may be used for cattle, sheep, swine, foxes, and mink after the animals are unconscious, often by a prior electrical stun. Pithing (inserting a tool into the base of the brain) is usable on animals already unconscious. Slow or rapid freezing, or inducing air embolism are acceptable only with prior anesthesia to induce unconsciousness.[189]

Research classification

[edit]Pure research

[edit]Basic or pure research investigates how organisms behave, develop, and function. Those opposed to animal testing object that pure research may have little or no practical purpose, but researchers argue that it forms the necessary basis for the development of applied research, rendering the distinction between pure and applied research—research that has a specific practical aim—unclear.[190] Pure research uses larger numbers and a greater variety of animals than applied research. Fruit flies, nematode worms, mice and rats together account for the vast majority, though small numbers of other species are used, ranging from sea slugs through to armadillos.[191] Examples of the types of animals and experiments used in basic research include:

- Studies on embryogenesis and developmental biology. Mutants are created by adding transposons into their genomes, or specific genes are deleted by gene targeting.[192][193] By studying the changes in development these changes produce, scientists aim to understand both how organisms normally develop, and what can go wrong in this process. These studies are particularly powerful since the basic controls of development, such as the homeobox genes, have similar functions in organisms as diverse as fruit flies and man.[194][195]

- Experiments into behavior, to understand how organisms detect and interact with each other and their environment, in which fruit flies, worms, mice, and rats are all widely used.[196][197] Studies of brain function, such as memory and social behavior, often use rats and birds.[198][199] For some species, behavioral research is combined with enrichment strategies for animals in captivity because it allows them to engage in a wider range of activities.[200]

- Breeding experiments to study evolution and genetics. Laboratory mice, flies, fish, and worms are inbred through many generations to create strains with defined characteristics.[201] These provide animals of a known genetic background, an important tool for genetic analyses. Larger mammals are rarely bred specifically for such studies due to their slow rate of reproduction, though some scientists take advantage of inbred domesticated animals, such as dog or cattle breeds, for comparative purposes. Scientists studying how animals evolve use many animal species to see how variations in where and how an organism lives (their niche) produce adaptations in their physiology and morphology. As an example, sticklebacks are now being used to study how many and which types of mutations are selected to produce adaptations in animals' morphology during the evolution of new species.[202][203]

Applied research

[edit]Applied research aims to solve specific and practical problems. These may involve the use of animal models of diseases or conditions, which are often discovered or generated by pure research programmes. In turn, such applied studies may be an early stage in the drug discovery process. Examples include:

- Genetic modification of animals to study disease. Transgenic animals have specific genes inserted, modified or removed, to mimic specific conditions such as single gene disorders, such as Huntington's disease.[204] Other models mimic complex, multifactorial diseases with genetic components, such as diabetes,[205] or even transgenic mice that carry the same mutations that occur during the development of cancer.[206] These models allow investigations on how and why the disease develops, as well as providing ways to develop and test new treatments.[207] The vast majority of these transgenic models of human disease are lines of mice, the mammalian species in which genetic modification is most efficient.[96] Smaller numbers of other animals are also used, including rats, pigs, sheep, fish, birds, and amphibians.[165]

- Studies on models of naturally occurring disease and condition. Certain domestic and wild animals have a natural propensity or predisposition for certain conditions that are also found in humans. Cats are used as a model to develop immunodeficiency virus vaccines and to study leukemia because their natural predisposition to FIV and Feline leukemia virus.[208][209] Certain breeds of dog experience narcolepsy making them the major model used to study the human condition. Armadillos and humans are among only a few animal species that naturally have leprosy; as the bacteria responsible for this disease cannot yet be grown in culture, armadillos are the primary source of bacilli used in leprosy vaccines.[191]

- Studies on induced animal models of human diseases. Here, an animal is treated so that it develops pathology and symptoms that resemble a human disease. Examples include restricting blood flow to the brain to induce stroke, or giving neurotoxins that cause damage similar to that seen in Parkinson's disease.[210] Much animal research into potential treatments for humans is wasted because it is poorly conducted and not evaluated through systematic reviews.[211] For example, although such models are now widely used to study Parkinson's disease, the British anti-vivisection interest group BUAV argues that these models only superficially resemble the disease symptoms, without the same time course or cellular pathology.[212] In contrast, scientists assessing the usefulness of animal models of Parkinson's disease, as well as the medical research charity The Parkinson's Appeal, state that these models were invaluable and that they led to improved surgical treatments such as pallidotomy, new drug treatments such as levodopa, and later deep brain stimulation.[118][210][213]

- Animal testing has also included the use of placebo testing. In these cases animals are treated with a substance that produces no pharmacological effect, but is administered in order to determine any biological alterations due to the experience of a substance being administered, and the results are compared with those obtained with an active compound.

Xenotransplantation

[edit]Xenotransplantation research involves transplanting tissues or organs from one species to another, as a way to overcome the shortage of human organs for use in organ transplants.[214] Current research involves using primates as the recipients of organs from pigs that have been genetically modified to reduce the primates' immune response against the pig tissue.[215] Although transplant rejection remains a problem,[215] recent clinical trials that involved implanting pig insulin-secreting cells into diabetics did reduce these people's need for insulin.[216][217]

Documents released to the news media by the animal rights organization Uncaged Campaigns showed that, between 1994 and 2000, wild baboons imported to the UK from Africa by Imutran Ltd, a subsidiary of Novartis Pharma AG, in conjunction with Cambridge University and Huntingdon Life Sciences, to be used in experiments that involved grafting pig tissues, had serious and sometimes fatal injuries. A scandal occurred when it was revealed that the company had communicated with the British government in an attempt to avoid regulation.[218][219]

Toxicology testing

[edit]Toxicology testing, also known as safety testing, is conducted by pharmaceutical companies testing drugs, or by contract animal testing facilities, such as Huntingdon Life Sciences, on behalf of a wide variety of customers.[220] According to 2005 EU figures, around one million animals are used every year in Europe in toxicology tests; which are about 10% of all procedures.[221] According to Nature, 5,000 animals are used for each chemical being tested, with 12,000 needed to test pesticides.[222] The tests are conducted without anesthesia, because interactions between drugs can affect how animals detoxify chemicals, and may interfere with the results.[223][224]

Toxicology tests are used to examine finished products such as pesticides, medications, food additives, packing materials, and air freshener, or their chemical ingredients. Most tests involve testing ingredients rather than finished products, but according to BUAV, manufacturers believe these tests overestimate the toxic effects of substances; they therefore repeat the tests using their finished products to obtain a less toxic label.[220]

The substances are applied to the skin or dripped into the eyes; injected intravenously, intramuscularly, or subcutaneously; inhaled either by placing a mask over the animals and restraining them, or by placing them in an inhalation chamber; or administered orally, through a tube into the stomach, or simply in the animal's food. Doses may be given once, repeated regularly for many months, or for the lifespan of the animal.[225]

There are several different types of acute toxicity tests. The LD50 ("Lethal Dose 50%") test is used to evaluate the toxicity of a substance by determining the dose required to kill 50% of the test animal population. This test was removed from OECD international guidelines in 2002, replaced by methods such as the fixed dose procedure, which use fewer animals and cause less suffering.[226][227] Abbott writes that, as of 2005, "the LD50 acute toxicity test ... still accounts for one-third of all animal [toxicity] tests worldwide".[222]

Irritancy can be measured using the Draize test, where a test substance is applied to an animal's eyes or skin, usually an albino rabbit. For Draize eye testing, the test involves observing the effects of the substance at intervals and grading any damage or irritation, but the test should be halted and the animal killed if it shows "continuing signs of severe pain or distress".[228] The Humane Society of the United States writes that the procedure can cause redness, ulceration, hemorrhaging, cloudiness, or even blindness.[229] This test has also been criticized by scientists for being cruel and inaccurate, subjective, over-sensitive, and failing to reflect human exposures in the real world.[230] Although no accepted in vitro alternatives exist, a modified form of the Draize test called the low volume eye test may reduce suffering and provide more realistic results and this was adopted as the new standard in September 2009.[231][232] However, the Draize test will still be used for substances that are not severe irritants.[232]

The most stringent tests are reserved for drugs and foodstuffs. For these, a number of tests are performed, lasting less than a month (acute), one to three months (subchronic), and more than three months (chronic) to test general toxicity (damage to organs), eye and skin irritancy, mutagenicity, carcinogenicity, teratogenicity, and reproductive problems. The cost of the full complement of tests is several million dollars per substance and it may take three or four years to complete.

These toxicity tests provide, in the words of a 2006 United States National Academy of Sciences report, "critical information for assessing hazard and risk potential".[233] Animal tests may overestimate risk, with false positive results being a particular problem,[222][234] but false positives appear not to be prohibitively common.[235] Variability in results arises from using the effects of high doses of chemicals in small numbers of laboratory animals to try to predict the effects of low doses in large numbers of humans.[236] Although relationships do exist, opinion is divided on how to use data on one species to predict the exact level of risk in another.[237]

Scientists face growing pressure to move away from using traditional animal toxicity tests to determine whether manufactured chemicals are safe.[238]Among variety of approaches to toxicity evaluation the ones which have attracted increasing interests are in vitro cell-based sensing methods applying fluorescence.[239]

Cosmetics testing

[edit]

Cosmetics testing on animals is particularly controversial. Such tests, which are still conducted in the U.S., involve general toxicity, eye and skin irritancy, phototoxicity (toxicity triggered by ultraviolet light) and mutagenicity.[240]

Cosmetics testing on animals is banned in India, the United Kingdom, the European Union,[241] Israel and Norway[242][243] while legislation in the U.S. and Brazil is currently considering similar bans.[244] In 2002, after 13 years of discussion, the European Union agreed to phase in a near-total ban on the sale of animal-tested cosmetics by 2009, and to ban all cosmetics-related animal testing. France, which is home to the world's largest cosmetics company, L'Oreal, has protested the proposed ban by lodging a case at the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg, asking that the ban be quashed.[245] The ban is also opposed by the European Federation for Cosmetics Ingredients, which represents 70 companies in Switzerland, Belgium, France, Germany, and Italy.[245] In October 2014, India passed stricter laws that also ban the importation of any cosmetic products that are tested on animals.[246]

Drug testing

[edit]Before the early 20th century, laws regulating drugs were lax. Currently, all new pharmaceuticals undergo rigorous animal testing before being licensed for human use. Tests on pharmaceutical products involve:

- metabolic tests, investigating pharmacokinetics—how drugs are absorbed, metabolized and excreted by the body when introduced orally, intravenously, intraperitoneally, intramuscularly, or transdermally.

- toxicology tests, which gauge acute, sub-acute, and chronic toxicity. Acute toxicity is studied by using a rising dose until signs of toxicity become apparent. Current European legislation demands that "acute toxicity tests must be carried out in two or more mammalian species" covering "at least two different routes of administration".[247] Sub-acute toxicity is where the drug is given to the animals for four to six weeks in doses below the level at which it causes rapid poisoning, in order to discover if any toxic drug metabolites build up over time. Testing for chronic toxicity can last up to two years and, in the European Union, is required to involve two species of mammals, one of which must be non-rodent.[248]

- efficacy studies, which test whether experimental drugs work by inducing the appropriate illness in animals. The drug is then administered in a double-blind controlled trial, which allows researchers to determine the effect of the drug and the dose-response curve.

- Specific tests on reproductive function, embryonic toxicity, or carcinogenic potential can all be required by law, depending on the result of other studies and the type of drug being tested.

Education

[edit]It is estimated that 20 million animals are used annually for educational purposes in the United States including, classroom observational exercises, dissections and live-animal surgeries.[249][250] Frogs, fetal pigs, perch, cats, earthworms, grasshoppers, crayfish and starfish are commonly used in classroom dissections.[251] Alternatives to the use of animals in classroom dissections are widely used, with many U.S. States and school districts mandating students be offered the choice to not dissect.[252] Citing the wide availability of alternatives and the decimation of local frog species, India banned dissections in 2014.[253][254]

The Sonoran Arthropod Institute hosts an annual Invertebrates in Education and Conservation Conference to discuss the use of invertebrates in education.[255] There also are efforts in many countries to find alternatives to using animals in education.[256] The NORINA database, maintained by Norecopa, lists products that may be used as alternatives or supplements to animal use in education, and in the training of personnel who work with animals.[257] These include alternatives to dissection in schools. InterNICHE has a similar database and a loans system.[258]

In November 2013, the U.S.-based company Backyard Brains released for sale to the public what they call the "Roboroach", an "electronic backpack" that can be attached to cockroaches. The operator is required to amputate a cockroach's antennae, use sandpaper to wear down the shell, insert a wire into the thorax, and then glue the electrodes and circuit board onto the insect's back. A mobile phone app can then be used to control it via Bluetooth.[259] It has been suggested that the use of such a device may be a teaching aid that can promote interest in science. The makers of the "Roboroach" have been funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and state that the device is intended to encourage children to become interested in neuroscience.[259][260]

Defense

[edit]Animals are used by the military to develop weapons, vaccines, battlefield surgical techniques, and defensive clothing.[190] For example, in 2008 the United States Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency used live pigs to study the effects of improvised explosive device explosions on internal organs, especially the brain.[261]

In the US military, goats are commonly used to train combat medics. (Goats have become the main animal species used for this purpose after the Pentagon phased out using dogs for medical training in the 1980s.[262]) While modern mannequins used in medical training are quite efficient in simulating the behavior of a human body, some trainees feel that "the goat exercise provide[s] a sense of urgency that only real life trauma can provide".[263] Nevertheless, in 2014, the U.S. Coast Guard announced that it would reduce the number of animals it uses in its training exercises by half after PETA released video showing Guard members cutting off the limbs of unconscious goats with tree trimmers and inflicting other injuries with a shotgun, pistol, ax and a scalpel.[264] That same year, citing the availability of human simulators and other alternatives, the Department of Defense announced it would begin reducing the number of animals it uses in various training programs.[265] In 2013, several Navy medical centers stopped using ferrets in intubation exercises after complaints from PETA.[266]

Besides the United States, six out of 28 NATO countries, including Poland and Denmark, use live animals for combat medic training.[262]

Ethics

[edit]Most animals are euthanized after being used in an experiment.[57] Sources of laboratory animals vary between countries and species; most animals are purpose-bred, while a minority are caught in the wild or supplied by dealers who obtain them from auctions and pounds.[267][268][153] Supporters of the use of animals in experiments, such as the British Royal Society, argue that virtually every medical achievement in the 20th century relied on the use of animals in some way.[117] The Institute for Laboratory Animal Research of the United States National Academy of Sciences has argued that animal research cannot be replaced by even sophisticated computer models, which are unable to deal with the extremely complex interactions between molecules, cells, tissues, organs, organisms and the environment.[269] Animal rights organizations—such as PETA and BUAV—question the need for and legitimacy of animal testing, arguing that it is cruel and poorly regulated, that medical progress is actually held back by misleading animal models that cannot reliably predict effects in humans, that some of the tests are outdated, that the costs outweigh the benefits, or that animals have the intrinsic right not to be used or harmed in experimentation.[52][270][271][272][273][274]

Viewpoints

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Animal rights |

|---|

The moral and ethical questions raised by performing experiments on animals are subject to debate, and viewpoints have shifted significantly over the 20th century.[275] There remain disagreements about which procedures are useful for which purposes, as well as disagreements over which ethical principles apply to which species.

A 2015 Gallup poll found that 67% of Americans were "very concerned" or "somewhat concerned" about animals used in research.[276] A Pew poll taken the same year found 50% of American adults opposed the use of animals in research.[277]

Still, a wide range of viewpoints exist. The view that animals have moral rights (animal rights) is a philosophical position proposed by Tom Regan, among others, who argues that animals are beings with beliefs and desires, and as such are the "subjects of a life" with moral value and therefore moral rights.[278] Regan still sees ethical differences between killing human and non-human animals, and argues that to save the former it is permissible to kill the latter. Likewise, a "moral dilemma" view suggests that avoiding potential benefit to humans is unacceptable on similar grounds, and holds the issue to be a dilemma in balancing such harm to humans to the harm done to animals in research.[279] In contrast, an abolitionist view in animal rights holds that there is no moral justification for any harmful research on animals that is not to the benefit of the individual animal.[279] Bernard Rollin argues that benefits to human beings cannot outweigh animal suffering, and that human beings have no moral right to use an animal in ways that do not benefit that individual. Donald Watson has stated that vivisection and animal experimentation "is probably the cruelest of all Man's attack on the rest of Creation."[280] Another prominent position is that of philosopher Peter Singer, who argues that there are no grounds to include a being's species in considerations of whether their suffering is important in utilitarian moral considerations.[281] Malcolm Macleod and collaborators argue that most controlled animal studies do not employ randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding outcome assessment, and that failure to employ these features exaggerates the apparent benefit of drugs tested in animals, leading to a failure to translate much animal research for human benefit.[282][283][284][285][286]

Governments such as the Netherlands and New Zealand have responded to the public's concerns by outlawing invasive experiments on certain classes of non-human primates, particularly the great apes.[287][288] In 2015, captive chimpanzees in the U.S. were added to the Endangered Species Act adding new road blocks to those wishing to experiment on them.[289] Similarly, citing ethical considerations and the availability of alternative research methods, the U.S. NIH announced in 2013 that it would dramatically reduce and eventually phase out experiments on chimpanzees.[290]

The British government has required that the cost to animals in an experiment be weighed against the gain in knowledge.[291] Some medical schools and agencies in China, Japan, and South Korea have built cenotaphs for killed animals.[292] In Japan there are also annual memorial services (Ireisai 慰霊祭) for animals sacrificed at medical school.

Various specific cases of animal testing have drawn attention, including both instances of beneficial scientific research, and instances of alleged ethical violations by those performing the tests. The fundamental properties of muscle physiology were determined with work done using frog muscles (including the force generating mechanism of all muscle,[293] the length-tension relationship,[294] and the force-velocity curve[295]), and frogs are still the preferred model organism due to the long survival of muscles in vitro and the possibility of isolating intact single-fiber preparations (not possible in other organisms).[296] Modern physical therapy and the understanding and treatment of muscular disorders is based on this work and subsequent work in mice (often engineered to express disease states such as muscular dystrophy).[297] In February 1997 a team at the Roslin Institute in Scotland announced the birth of Dolly the sheep, the first mammal to be cloned from an adult somatic cell.[79]

Concerns have been raised over the mistreatment of primates undergoing testing. In 1985, the case of Britches, a macaque monkey at the University of California, Riverside, gained public attention. He had his eyelids sewn shut and a sonar sensor on his head as part of an experiment to test sensory substitution devices for blind people. The laboratory was raided by Animal Liberation Front in 1985, removing Britches and 466 other animals.[298] The National Institutes of Health conducted an eight-month investigation and concluded, however, that no corrective action was necessary.[299] During the 2000s other cases have made headlines, including experiments at the University of Cambridge[300] and Columbia University in 2002.[301] In 2004 and 2005, undercover footage of staff of Covance's, a contract research organization that provides animal testing services, Virginia lab was shot by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). Following release of the footage, the U.S. Department of Agriculture fined Covance $8,720 for 16 citations, three of which involved lab monkeys; the other citations involved administrative issues and equipment.[302][303]

Threats to researchers

[edit]Threats of violence to animal researchers are not uncommon.[vague][304]

In 2006, a primate researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) shut down the experiments in his lab after threats from animal rights activists. The researcher had received a grant to use 30 macaque monkeys for vision experiments; each monkey was anesthetized for a single physiological experiment lasting up to 120 hours, and then euthanized.[305] The researcher's name, phone number, and address were posted on the website of the Primate Freedom Project. Demonstrations were held in front of his home. A Molotov cocktail was placed on the porch of what was believed to be the home of another UCLA primate researcher; instead, it was accidentally left on the porch of an elderly woman unrelated to the university. The Animal Liberation Front claimed responsibility for the attack.[306] As a result of the campaign, the researcher sent an email to the Primate Freedom Project stating "you win", and "please don't bother my family anymore".[307] In another incident at UCLA in June 2007, the Animal Liberation Brigade placed a bomb under the car of a UCLA children's ophthalmologist who experiments on cats and rhesus monkeys; the bomb had a faulty fuse and did not detonate.[308]

In 1997, PETA filmed staff from Huntingdon Life Sciences, showing dogs being mistreated.[309][310] The employees responsible were dismissed,[311] with two given community service orders and ordered to pay £250 costs, the first lab technicians to have been prosecuted for animal cruelty in the UK.[312] The Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty campaign used tactics ranging from non-violent protest to the alleged firebombing of houses owned by executives associated with HLS's clients and investors. The Southern Poverty Law Center, which monitors US domestic extremism, has described SHAC's modus operandi as "frankly terroristic tactics similar to those of anti-abortion extremists", and in 2005 an official with the FBI's counter-terrorism division referred to SHAC's activities in the United States as domestic terrorist threats.[313][314] 13 members of SHAC were jailed for between 15 months and eleven years on charges of conspiracy to blackmail or harm HLS and its suppliers.[315][316]

These attacks—as well as similar incidents that caused the Southern Poverty Law Center to declare in 2002 that the animal rights movement had "clearly taken a turn toward the more extreme"—prompted the US government to pass the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act and the UK government to add the offense of "Intimidation of persons connected with animal research organisation" to the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005. Such legislation and the arrest and imprisonment of activists may have decreased the incidence of attacks.[317]

Scientific criticism

[edit]Systematic reviews have pointed out that animal testing often fails to accurately mirror outcomes in humans.[318][319] For instance, a 2013 review noted that some 100 vaccines have been shown to prevent HIV in animals, yet none of them have worked on humans.[319] Effects seen in animals may not be replicated in humans, and vice versa. Many corticosteroids cause birth defects in animals, but not in humans. Conversely, thalidomide causes serious birth defects in humans, but not in some animals such as mice (however, it does cause birth defects in rabbits).[320] A 2004 paper concluded that much animal research is wasted because systemic reviews are not used, and due to poor methodology.[321] A 2006 review found multiple studies where there were promising results for new drugs in animals, but human clinical studies did not show the same results. The researchers suggested that this might be due to researcher bias, or simply because animal models do not accurately reflect human biology.[322] Lack of meta-reviews may be partially to blame.[320] Poor methodology is an issue in many studies. A 2009 review noted that many animal experiments did not use blinded experiments, a key element of many scientific studies in which researchers are not told about the part of the study they are working on to reduce bias.[320][323] A 2021 paper found, in a sample of Open Access Alzheimer Disease studies, that if the authors omit from the title that the experiment was performed in mice, the News Headline follow suit, and that also the Twitter repercussion is higher.[324]

Activism

[edit]There are various examples of activists utilizing Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to obtain information about taxpayer funding of animal testing. For example, the White Coat Waste Project, a group of activists that hold that taxpayers should not have

to pay $20 billion every year for experiments on animals,[325] highlighted that the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases provided $400,000 in taxpayer money to fund experiments in which 28 beagles were infected by disease-causing parasites.[326] The White Coat Project found reports that said dogs taking part in the experiments were "vocalizing in pain" after being injected with foreign substances.[327] Following public outcry, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) made a call to action that all members of the National Institute of Health resign effective immediately[328] and that there is a "need to find a new NIH director to replace the outgoing Francis Collins who will shut down research that violates the dignity of nonhuman animals."[329]

Historical debate

[edit]

As the experimentation on animals increased, especially the practice of vivisection, so did criticism and controversy. In 1655, the advocate of Galenic physiology Edmund O'Meara said that "the miserable torture of vivisection places the body in an unnatural state".[332][333] O'Meara and others argued pain could affect animal physiology during vivisection, rendering results unreliable. There were also objections ethically, contending that the benefit to humans did not justify the harm to animals.[333] Early objections to animal testing also came from another angle—many people believed animals were inferior to humans and so different that results from animals could not be applied to humans.[2][333]

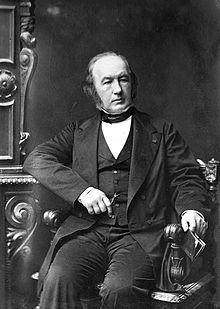

On the other side of the debate, those in favor of animal testing held that experiments on animals were necessary to advance medical and biological knowledge. Claude Bernard—who is sometimes known as the "prince of vivisectors"[330] and the father of physiology, and whose wife, Marie Françoise Martin, founded the first anti-vivisection society in France in 1883[334]—famously wrote in 1865 that "the science of life is a superb and dazzlingly lighted hall which may be reached only by passing through a long and ghastly kitchen".[335] Arguing that "experiments on animals [. . .] are entirely conclusive for the toxicology and hygiene of man [. . . T]he effects of these substances are the same on man as on animals, save for differences in degree",[331] Bernard established animal experimentation as part of the standard scientific method.[336]

In 1896, the physiologist and physician Dr. Walter B. Cannon said "The antivivisectionists are the second of the two types Theodore Roosevelt described when he said, 'Common sense without conscience may lead to crime, but conscience without common sense may lead to folly, which is the handmaiden of crime.'"[337] These divisions between pro- and anti-animal testing groups first came to public attention during the Brown Dog affair in the early 1900s, when hundreds of medical students clashed with anti-vivisectionists and police over a memorial to a vivisected dog.[338]

In 1822, the first animal protection law was enacted in the British parliament, followed by the Cruelty to Animals Act (1876), the first law specifically aimed at regulating animal testing. The legislation was promoted by Charles Darwin, who wrote to Ray Lankester in March 1871: "You ask about my opinion on vivisection. I quite agree that it is justifiable for proper investigations on physiology; but not for mere damnable and detestable curiosity. It is a subject which makes me sick with horror, so I will not say another word about it, else I shall not sleep to-night."[339][340] In response to the lobbying by anti-vivisectionists, several organizations were set up in Britain to defend animal research: The Physiological Society was formed in 1876 to give physiologists "mutual benefit and protection",[341] the Association for the Advancement of Medicine by Research was formed in 1882 and focused on policy-making, and the Research Defence Society (now Understanding Animal Research) was formed in 1908 "to make known the facts as to experiments on animals in this country; the immense importance to the welfare of mankind of such experiments and the great saving of human life and health directly attributable to them".[342]

Opposition to the use of animals in medical research first arose in the United States during the 1860s, when Henry Bergh founded the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), with America's first specifically anti-vivisection organization being the American AntiVivisection Society (AAVS), founded in 1883. Antivivisectionists of the era generally believed the spread of mercy was the great cause of civilization, and vivisection was cruel. However, in the USA the antivivisectionists' efforts were defeated in every legislature, overwhelmed by the superior organization and influence of the medical community. Overall, this movement had little legislative success until the passing of the Laboratory Animal Welfare Act, in 1966.[343]

Real progress in thinking about animal rights build on the "theory of justice" (1971) by the philosopher John Rawls and work on ethics by philosopher Peter Singer.[2]

Alternatives

[edit]Most scientists and governments state that animal testing should cause as little suffering to animals as possible, and that animal tests should only be performed where necessary. The "Three Rs" are guiding principles for the use of animals in research in most countries.[142][182] Whilst replacement of animals, i.e. alternatives to animal testing, is one of the principles, their scope is much broader.[344] Although such principles have been welcomed as a step forwards by some animal welfare groups,[345] they have also been criticized as both outdated by current research,[346] and of little practical effect in improving animal welfare.[347] The scientists and engineers at Harvard's Wyss Institute have created "organs-on-a-chip", including the "lung-on-a-chip" and "gut-on-a-chip". Researchers at cellasys in Germany developed a "skin-on-a-chip".[348] These tiny devices contain human cells in a 3-dimensional system that mimics human organs. The chips can be used instead of animals in in vitro disease research, drug testing, and toxicity testing.[349] Researchers have also begun using 3-D bioprinters to create human tissues for in vitro testing.[350]

Another non-animal research method is in silico or computer simulation and mathematical modeling which seeks to investigate and ultimately predict toxicity and drug effects on humans without using animals. This is done by investigating test compounds on a molecular level using recent advances in technological capabilities with the ultimate goal of creating treatments unique to each patient.[351][352] Microdosing is another alternative to the use of animals in experimentation. Microdosing is a process whereby volunteers are administered a small dose of a test compound allowing researchers to investigate its pharmacological affects without harming the volunteers. Microdosing can replace the use of animals in pre-clinical drug screening and can reduce the number of animals used in safety and toxicity testing.[353] Additional alternative methods include positron emission tomography (PET), which allows scanning of the human brain in vivo,[354] and comparative epidemiological studies of disease risk factors among human populations.[355] Simulators and computer programs have also replaced the use of animals in dissection, teaching and training exercises.[356][357]

Official bodies such as the European Centre for the Validation of Alternative Test Methods of the European Commission, the Interagency Coordinating Committee for the Validation of Alternative Methods in the US,[358] ZEBET in Germany,[359] and the Japanese Center for the Validation of Alternative Methods[360] (among others) also promote and disseminate the 3Rs. These bodies are mainly driven by responding to regulatory requirements, such as supporting the cosmetics testing ban in the EU by validating alternative methods. The European Partnership for Alternative Approaches to Animal Testing serves as a liaison between the European Commission and industries.[361] The European Consensus Platform for Alternatives coordinates efforts amongst EU member states.[362] Academic centers also investigate alternatives, including the Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing at the Johns Hopkins University[363] and the NC3Rs in the UK.[364]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ ""Introduction", Select Committee on Animals in Scientific Procedures Report". UK Parliament. Retrieved 13 July 2012.