Рак

Эта статья включает список литературы , связанную литературу или внешние ссылки , но ее источники остаются неясными, поскольку в ней отсутствуют встроенные цитаты . ( Март 2024 г. ) |

| Рак | |

|---|---|

| Другие имена | Злокачественная опухоль , злокачественное новообразование |

| |

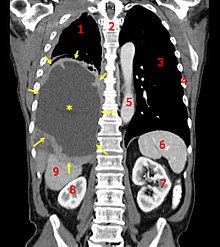

| A coronal CT scan showing a malignant mesothelioma Условные обозначения: → опухоль ←, ✱ центральный плевральный выпот , 1 и 3 легкие , 2 позвоночника , 4 ребра , 5 аорта , 6 селезенка , 7 и 8 почки , 9 печень | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

| Symptoms | Lump, abnormal bleeding, prolonged cough, unexplained weight loss, change in bowel movements[1] |

| Risk factors | Exposure to carcinogens, tobacco, obesity, poor diet, lack of physical activity, excessive alcohol, certain infections[2][3] |

| Treatment | Radiation therapy, surgery, chemotherapy, targeted therapy[2][4] |

| Prognosis | Average five-year survival 66% (USA)[5] |

| Frequency | 24 million annually (2019)[6] |

| Deaths | 10 million annually (2019)[6] |

Рак — это группа заболеваний, сопровождающихся аномальным ростом клеток с возможностью проникновения или распространения на другие части тела. [2] [7] Они контрастируют с доброкачественными опухолями , которые не распространяются. [7] Возможные признаки и симптомы включают шишку, аномальное кровотечение, продолжительный кашель, необъяснимую потерю веса и изменение стула . [1] Хотя эти симптомы могут указывать на рак, они также могут иметь и другие причины. [1] У человека более 100 видов рака. [7]

Употребление табака является причиной около 22% случаев смерти от рака. [2] Еще 10% связаны с ожирением , неправильным питанием , недостатком физической активности или чрезмерным употреблением алкоголя . [2] [8] [9] Другие факторы включают определенные инфекции, воздействие ионизирующей радиации и загрязнителей окружающей среды. [3] Инфекция специфическими вирусами, бактериями и паразитами является фактором окружающей среды, вызывающим примерно 16-18% случаев рака во всем мире. [10] Эти инфекционные агенты включают Helicobacter pylori , гепатит B , гепатит C , папилломавирусную инфекцию человека , вирус Эпштейна-Барра , Т-лимфотропный вирус человека 1 , герпесвирус, ассоциированный с саркомой Капоши, и полиомавирус клеток Меркеля . Вирус иммунодефицита человека (ВИЧ) не вызывает непосредственно рак, но вызывает иммунодефицит, который может увеличить риск, связанный с другими инфекциями, иногда в несколько тысяч раз (в случае саркомы Капоши ). Важно отметить, что вакцинация против гепатита В и вируса папилломы человека практически устраняет риск развития рака, вызываемого этими вирусами, у лиц, успешно вакцинированных до заражения.

These environmental factors act, at least partly, by changing the genes of a cell.[11] Typically, many genetic changes are required before cancer develops.[11] Approximately 5–10% of cancers are due to inherited genetic defects.[12] Cancer can be detected by certain signs and symptoms or screening tests.[2] It is then typically further investigated by medical imaging and confirmed by biopsy.[13]

The risk of developing certain cancers can be reduced by not smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, limiting alcohol intake, eating plenty of vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, vaccination against certain infectious diseases, limiting consumption of processed meat and red meat, and limiting exposure to direct sunlight.[14][15] Early detection through screening is useful for cervical and colorectal cancer.[16] The benefits of screening for breast cancer are controversial.[16][17] Cancer is often treated with some combination of radiation therapy, surgery, chemotherapy and targeted therapy.[2][4] Pain and symptom management are an important part of care.[2] Palliative care is particularly important in people with advanced disease.[2] The chance of survival depends on the type of cancer and extent of disease at the start of treatment.[11] In children under 15 at diagnosis, the five-year survival rate in the developed world is on average 80%.[18] For cancer in the United States, the average five-year survival rate is 66% for all ages.[5]

In 2015, about 90.5 million people worldwide had cancer.[19] In 2019, annual cancer cases grew by 23.6 million people, and there were 10 million deaths worldwide, representing over the previous decade increases of 26% and 21%, respectively.[6][20]

The most common types of cancer in males are lung cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, and stomach cancer.[21][22] In females, the most common types are breast cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer, and cervical cancer.[11][22] If skin cancer other than melanoma were included in total new cancer cases each year, it would account for around 40% of cases.[23][24] In children, acute lymphoblastic leukemia and brain tumors are most common, except in Africa, where non-Hodgkin lymphoma occurs more often.[18] In 2012, about 165,000 children under 15 years of age were diagnosed with cancer.[21] The risk of cancer increases significantly with age, and many cancers occur more commonly in developed countries.[11] Rates are increasing as more people live to an old age and as lifestyle changes occur in the developing world.[25] The global total economic costs of cancer were estimated at US$1.16 trillion (equivalent to $1.62 trillion in 2023) per year as of 2010[update].[26]

Etymology and definitions

The word comes from the ancient Greek καρκίνος, meaning 'crab' and 'tumor'. Greek physicians Hippocrates and Galen, among others, noted the similarity of crabs to some tumors with swollen veins. The word was introduced in English in the modern medical sense around 1600.[27]

Cancers comprise a large family of diseases that involve abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body.[2][7] They form a subset of neoplasms. A neoplasm or tumor is a group of cells that have undergone unregulated growth and will often form a mass or lump, but may be distributed diffusely.[28][29]

All tumor cells show the six hallmarks of cancer. These characteristics are required to produce a malignant tumor. They include:[30]

- Cell growth and division absent the proper signals

- Continuous growth and division even given contrary signals

- Avoidance of programmed cell death

- Limitless number of cell divisions

- Promoting blood vessel construction

- Invasion of tissue and formation of metastases[30]

The progression from normal cells to cells that can form a detectable mass to cancer involves multiple steps known as malignant progression.[30][31]

Signs and symptoms

When cancer begins, it produces no symptoms. Signs and symptoms appear as the mass grows or ulcerates. The findings that result depend on cancer's type and location. Few symptoms are specific. Many frequently occur in individuals who have other conditions. Cancer can be difficult to diagnose and can be considered a "great imitator".[32]

People may become anxious or depressed post-diagnosis. The risk of suicide in people with cancer is approximately double.[33]

Local symptoms

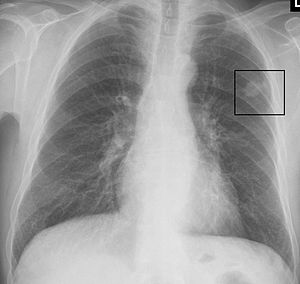

Local symptoms may occur due to the mass of the tumor or its ulceration. For example, mass effects from lung cancer can block the bronchus resulting in cough or pneumonia; esophageal cancer can cause narrowing of the esophagus, making it difficult or painful to swallow; and colorectal cancer may lead to narrowing or blockages in the bowel, affecting bowel habits. Masses in breasts or testicles may produce observable lumps. Ulceration can cause bleeding that can lead to symptoms such as coughing up blood (lung cancer), anemia or rectal bleeding (colon cancer), blood in the urine (bladder cancer), or abnormal vaginal bleeding (endometrial or cervical cancer). Although localized pain may occur in advanced cancer, the initial tumor is usually painless. Some cancers can cause a buildup of fluid within the chest or abdomen.[32]

Systemic symptoms

Systemic symptoms may occur due to the body's response to the cancer. This may include fatigue, unintentional weight loss, or skin changes.[34] Some cancers can cause a systemic inflammatory state that leads to ongoing muscle loss and weakness, known as cachexia.[35]

Some cancers, such as Hodgkin's disease, leukemias, and liver or kidney cancers, can cause a persistent fever.[32]

Shortness of breath, called dyspnea, is a common symptom of cancer and its treatment. The causes of cancer-related dyspnea can include tumors in or around the lung, blocked airways, fluid in the lungs, pneumonia, or treatment reactions including an allergic response.[36] Treatment for dyspnea in patients with advanced cancer can include fans, bilevel ventilation, acupressure/reflexology and multicomponent nonpharmacological interventions.[37]

Some systemic symptoms of cancer are caused by hormones or other molecules produced by the tumor, known as paraneoplastic syndromes. Common paraneoplastic syndromes include hypercalcemia, which can cause altered mental state, constipation and dehydration, or hyponatremia, which can also cause altered mental status, vomiting, headaches, or seizures.[38]

Metastasis

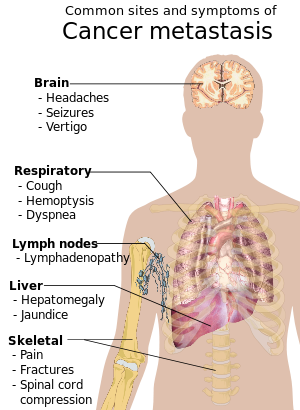

Metastasis is the spread of cancer to other locations in the body. The dispersed tumors are called metastatic tumors, while the original is called the primary tumor. Almost all cancers can metastasize.[39] Most cancer deaths are due to cancer that has metastasized.[40]

Metastasis is common in the late stages of cancer and it can occur via the blood or the lymphatic system or both. The typical steps in metastasis are local invasion, intravasation into the blood or lymph, circulation through the body, extravasation into the new tissue, proliferation and angiogenesis. Different types of cancers tend to metastasize to particular organs, but overall the most common places for metastases to occur are the lungs, liver, brain, and the bones.[39]

While some cancers can be cured if detected early, metastatic cancer is more difficult to treat and control. Nevertheless, some recent treatments are demonstrating encouraging results.[41]

Causes

The majority of cancers, some 90–95% of cases, are due to genetic mutations from environmental and lifestyle factors.[3] The remaining 5–10% are due to inherited genetics.[3] Environmental refers to any cause that is not inherited, such as lifestyle, economic, and behavioral factors and not merely pollution.[43] Common environmental factors that contribute to cancer death include tobacco use (25–30%), diet and obesity (30–35%), infections (15–20%), radiation (both ionizing and non-ionizing, up to 10%), lack of physical activity, and pollution.[3][44] Psychological stress does not appear to be a risk factor for the onset of cancer,[45][46] though it may worsen outcomes in those who already have cancer.[45]

Environmental or lifestyle factors that caused cancer to develop in an individual can be identified by analyzing mutational signatures from genomic sequencing of tumor DNA. For example, this can reveal if lung cancer was caused by tobacco smoke, if skin cancer was caused by UV radiation, or if secondary cancers were caused by previous chemotherapy treatment.[47]

Cancer is generally not a transmissible disease.[48] Exceptions include rare transmissions that occur with pregnancies and occasional organ donors. However, transmissible infectious diseases such as hepatitis B, Epstein-Barr virus, Human Papilloma Virus and HIV, can contribute to the development of cancer.[citation needed]

Chemicals

Exposure to particular substances have been linked to specific types of cancer. These substances are called carcinogens.

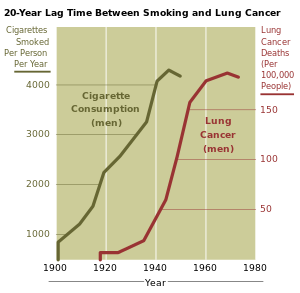

Tobacco smoke, for example, causes 90% of lung cancer.[49] Tobacco use can cause cancer throughout the body including in the mouth and throat, larynx, esophagus, stomach, bladder, kidney, cervix, colon/rectum, liver and pancreas.[50][51] Tobacco smoke contains over fifty known carcinogens, including nitrosamines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.[52]

Tobacco is responsible for about one in five cancer deaths worldwide[52] and about one in three in the developed world.[53] Lung cancer death rates in the United States have mirrored smoking patterns, with increases in smoking followed by dramatic increases in lung cancer death rates and, more recently, decreases in smoking rates since the 1950s followed by decreases in lung cancer death rates in men since 1990.[54][55]

In Western Europe, 10% of cancers in males and 3% of cancers in females are attributed to alcohol exposure, especially liver and digestive tract cancers.[56] Cancer from work-related substance exposures may cause between 2 and 20% of cases,[57] causing at least 200,000 deaths.[58] Cancers such as lung cancer and mesothelioma can come from inhaling tobacco smoke or asbestos fibers, or leukemia from exposure to benzene.[58]

Exposure to perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), which is predominantly used in the production of Teflon, is known to cause two kinds of cancer.[59][60]

Chemotherapy drugs such as platinum-based compounds are carcinogens that increase the risk of secondary cancers[47]

Azathioprine, an immunosuppressive medication, is a carcinogen that can cause primary tumors to develop.[47]

Diet and exercise

Diet, physical inactivity, and obesity are related to up to 30–35% of cancer deaths.[3][61] In the United States, excess body weight is associated with the development of many types of cancer and is a factor in 14–20% of cancer deaths.[61] A UK study including data on over 5 million people showed higher body mass index to be related to at least 10 types of cancer and responsible for around 12,000 cases each year in that country.[62] Physical inactivity is believed to contribute to cancer risk, not only through its effect on body weight but also through negative effects on the immune system and endocrine system.[61] More than half of the effect from the diet is due to overnutrition (eating too much), rather than from eating too few vegetables or other healthful foods.[citation needed]

Some specific foods are linked to specific cancers. A high-salt diet is linked to gastric cancer.[63] Aflatoxin B1, a frequent food contaminant, causes liver cancer.[63] Betel nut chewing can cause oral cancer.[63] National differences in dietary practices may partly explain differences in cancer incidence. For example, gastric cancer is more common in Japan due to its high-salt diet[64] while colon cancer is more common in the United States. Immigrant cancer profiles mirror those of their new country, often within one generation.[65]

Infection

Worldwide, approximately 18% of cancer deaths are related to infectious diseases.[3] This proportion ranges from a high of 25% in Africa to less than 10% in the developed world.[3] Viruses[66] are the usual infectious agents that cause cancer but bacteria and parasites may also play a role. Oncoviruses (viruses that can cause human cancer) include:

- Human papillomavirus (cervical cancer),

- Epstein–Barr virus (B-cell lymphoproliferative disease and nasopharyngeal carcinoma),

- Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus (Kaposi's sarcoma and primary effusion lymphomas),

- Hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses (hepatocellular carcinoma)

- Human T-cell leukemia virus-1 (T-cell leukemias).

- Merkel cell polyomavirus (Merkel cell carcinoma)

Bacterial infection may also increase the risk of cancer, as seen in

- Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric carcinoma.[67][68]

- Colibactin, a genotoxin associated with Escherichia coli infection (colorectal cancer)[47]

Parasitic infections associated with cancer include:

- Schistosoma haematobium (squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder)

- The liver flukes, Opisthorchis viverrini and Clonorchis sinensis (cholangiocarcinoma).[69]

Radiation

Radiation exposure such as ultraviolet radiation and radioactive material is a risk factor for cancer.[70][71][72] Many non-melanoma skin cancers are due to ultraviolet radiation, mostly from sunlight.[71] Sources of ionizing radiation include medical imaging and radon gas.[71]

Ionizing radiation is not a particularly strong mutagen.[73] Residential exposure to radon gas, for example, has similar cancer risks as passive smoking.[73] Radiation is a more potent source of cancer when combined with other cancer-causing agents, such as radon plus tobacco smoke.[73] Radiation can cause cancer in most parts of the body, in all animals and at any age. Children are twice as likely to develop radiation-induced leukemia as adults; radiation exposure before birth has ten times the effect.[73]

Medical use of ionizing radiation is a small but growing source of radiation-induced cancers. Ionizing radiation may be used to treat other cancers, but this may, in some cases, induce a second form of cancer.[73] It is also used in some kinds of medical imaging.[74]

Prolonged exposure to ultraviolet radiation from the sun can lead to melanoma and other skin malignancies.[75] Clear evidence establishes ultraviolet radiation, especially the non-ionizing medium wave UVB, as the cause of most non-melanoma skin cancers, which are the most common forms of cancer in the world.[75]

Non-ionizing radio frequency radiation from mobile phones, electric power transmission and other similar sources has been described as a possible carcinogen by the World Health Organization's International Agency for Research on Cancer.[76] Evidence, however, has not supported a concern.[77][70] This includes that studies have not found a consistent link between mobile phone radiation and cancer risk.[78]

Heredity

The vast majority of cancers are non-hereditary (sporadic). Hereditary cancers are primarily caused by an inherited genetic defect. Less than 0.3% of the population are carriers of a genetic mutation that has a large effect on cancer risk and these cause less than 3–10% of cancer.[79] Some of these syndromes include: certain inherited mutations in the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 with a more than 75% risk of breast cancer and ovarian cancer,[79] and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC or Lynch syndrome), which is present in about 3% of people with colorectal cancer,[80] among others.

Statistically for cancers causing most mortality, the relative risk of developing colorectal cancer when a first-degree relative (parent, sibling or child) has been diagnosed with it is about 2.[81] The corresponding relative risk is 1.5 for lung cancer,[82] and 1.9 for prostate cancer.[83] For breast cancer, the relative risk is 1.8 with a first-degree relative having developed it at 50 years of age or older, and 3.3 when the relative developed it when being younger than 50 years of age.[84]

Taller people have an increased risk of cancer because they have more cells than shorter people. Since height is genetically determined to a large extent, taller people have a heritable increase of cancer risk.[85]

Physical agents

Some substances cause cancer primarily through their physical, rather than chemical, effects.[86] A prominent example of this is prolonged exposure to asbestos, naturally occurring mineral fibers that are a major cause of mesothelioma (cancer of the serous membrane) usually the serous membrane surrounding the lungs.[86] Other substances in this category, including both naturally occurring and synthetic asbestos-like fibers, such as wollastonite, attapulgite, glass wool and rock wool, are believed to have similar effects.[86] Non-fibrous particulate materials that cause cancer include powdered metallic cobalt and nickel and crystalline silica (quartz, cristobalite and tridymite).[86] Usually, physical carcinogens must get inside the body (such as through inhalation) and require years of exposure to produce cancer.[86]

Physical trauma resulting in cancer is relatively rare.[87] Claims that breaking bones resulted in bone cancer, for example, have not been proven.[87] Similarly, physical trauma is not accepted as a cause for cervical cancer, breast cancer or brain cancer.[87] One accepted source is frequent, long-term application of hot objects to the body. It is possible that repeated burns on the same part of the body, such as those produced by kanger and kairo heaters (charcoal hand warmers), may produce skin cancer, especially if carcinogenic chemicals are also present.[87] Frequent consumption of scalding hot tea may produce esophageal cancer.[87] Generally, it is believed that cancer arises, or a pre-existing cancer is encouraged, during the process of healing, rather than directly by the trauma.[87] However, repeated injuries to the same tissues might promote excessive cell proliferation, which could then increase the odds of a cancerous mutation.[citation needed]

Chronic inflammation has been hypothesized to directly cause mutation.[87][88] Inflammation can contribute to proliferation, survival, angiogenesis and migration of cancer cells by influencing the tumor microenvironment.[89][90] Oncogenes build up an inflammatory pro-tumorigenic microenvironment.[91]

Hormones

Hormones also play a role in the development of cancer by promoting cell proliferation.[92] Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins play a key role in cancer cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis, suggesting possible involvement in carcinogenesis.[93]

Hormones are important agents in sex-related cancers, such as cancer of the breast, endometrium, prostate, ovary and testis and also of thyroid cancer and bone cancer.[92] For example, the daughters of women who have breast cancer have significantly higher levels of estrogen and progesterone than the daughters of women without breast cancer. These higher hormone levels may explain their higher risk of breast cancer, even in the absence of a breast-cancer gene.[92] Similarly, men of African ancestry have significantly higher levels of testosterone than men of European ancestry and have a correspondingly higher level of prostate cancer.[92] Men of Asian ancestry, with the lowest levels of testosterone-activating androstanediol glucuronide, have the lowest levels of prostate cancer.[92]

Other factors are relevant: obese people have higher levels of some hormones associated with cancer and a higher rate of those cancers.[92] Women who take hormone replacement therapy have a higher risk of developing cancers associated with those hormones.[92] On the other hand, people who exercise far more than average have lower levels of these hormones and lower risk of cancer.[92] Osteosarcoma may be promoted by growth hormones.[92] Some treatments and prevention approaches leverage this cause by artificially reducing hormone levels and thus discouraging hormone-sensitive cancers.[92]

Autoimmune diseases

There is an association between celiac disease and an increased risk of all cancers. People with untreated celiac disease have a higher risk, but this risk decreases with time after diagnosis and strict treatment. This may be due to the adoption of a gluten-free diet, which seems to have a protective role against development of malignancy in people with celiac disease. However, the delay in diagnosis and initiation of a gluten-free diet seems to increase the risk of malignancies.[94] Rates of gastrointestinal cancers are increased in people with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, due to chronic inflammation. Immunomodulators and biologic agents used to treat these diseases may promote developing extra-intestinal malignancies.[95]

Pathophysiology

Genetics

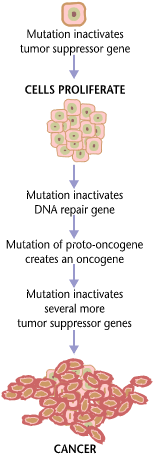

Cancer is fundamentally a disease of tissue growth regulation. For a normal cell to transform into a cancer cell, the genes that regulate cell growth and differentiation must be altered.[96]

The affected genes are divided into two broad categories. Oncogenes are genes that promote cell growth and reproduction. Tumor suppressor genes are genes that inhibit cell division and survival. Malignant transformation can occur through the formation of novel oncogenes, the inappropriate over-expression of normal oncogenes, or by the under-expression or disabling of tumor suppressor genes. Typically, changes in multiple genes are required to transform a normal cell into a cancer cell.[97]

Genetic changes can occur at different levels and by different mechanisms. The gain or loss of an entire chromosome can occur through errors in mitosis. More common are mutations, which are changes in the nucleotide sequence of genomic DNA.

Large-scale mutations involve the deletion or gain of a portion of a chromosome. Genomic amplification occurs when a cell gains copies (often 20 or more) of a small chromosomal locus, usually containing one or more oncogenes and adjacent genetic material. Translocation occurs when two separate chromosomal regions become abnormally fused, often at a characteristic location. A well-known example of this is the Philadelphia chromosome, or translocation of chromosomes 9 and 22, which occurs in chronic myelogenous leukemia and results in production of the BCR-abl fusion protein, an oncogenic tyrosine kinase.

Small-scale mutations include point mutations, deletions, and insertions, which may occur in the promoter region of a gene and affect its expression, or may occur in the gene's coding sequence and alter the function or stability of its protein product. Disruption of a single gene may also result from integration of genomic material from a DNA virus or retrovirus, leading to the expression of viral oncogenes in the affected cell and its descendants.

Replication of the data contained within the DNA of living cells will probabilistically result in some errors (mutations). Complex error correction and prevention are built into the process and safeguard the cell against cancer. If a significant error occurs, the damaged cell can self-destruct through programmed cell death, termed apoptosis. If the error control processes fail, then the mutations will survive and be passed along to daughter cells.

Some environments make errors more likely to arise and propagate. Such environments can include the presence of disruptive substances called carcinogens, repeated physical injury, heat, ionising radiation, or hypoxia.[98]

The errors that cause cancer are self-amplifying and compounding, for example:

- A mutation in the error-correcting machinery of a cell might cause that cell and its children to accumulate errors more rapidly.

- A further mutation in an oncogene might cause the cell to reproduce more rapidly and more frequently than its normal counterparts.

- A further mutation may cause loss of a tumor suppressor gene, disrupting the apoptosis signaling pathway and immortalizing the cell.

- A further mutation in the signaling machinery of the cell might send error-causing signals to nearby cells.

The transformation of a normal cell into cancer is akin to a chain reaction caused by initial errors, which compound into more severe errors, each progressively allowing the cell to escape more controls that limit normal tissue growth. This rebellion-like scenario is an undesirable survival of the fittest, where the driving forces of evolution work against the body's design and enforcement of order. Once cancer has begun to develop, this ongoing process, termed clonal evolution, drives progression towards more invasive stages.[99] Clonal evolution leads to intra-tumour heterogeneity (cancer cells with heterogeneous mutations) that complicates designing effective treatment strategies and requires an evolutionary approach to designing treatment.

Characteristic abilities developed by cancers are divided into categories, specifically evasion of apoptosis, self-sufficiency in growth signals, insensitivity to anti-growth signals, sustained angiogenesis, limitless replicative potential, metastasis, reprogramming of energy metabolism and evasion of immune destruction.[30][31]

Epigenetics

The classical view of cancer is a set of diseases driven by progressive genetic abnormalities that include mutations in tumor-suppressor genes and oncogenes, and in chromosomal abnormalities. A role for epigenetic alterations was identified in the early 21st century.[100]

Epigenetic alterations are functionally relevant modifications to the genome that do not change the nucleotide sequence. Examples of such modifications are changes in DNA methylation (hypermethylation and hypomethylation), histone modification[101] and changes in chromosomal architecture (caused by inappropriate expression of proteins such as HMGA2 or HMGA1).[102] Each of these alterations regulates gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These changes may remain through cell divisions, endure for multiple generations, and can be considered as equivalent to mutations.

Epigenetic alterations occur frequently in cancers. As an example, one study listed protein coding genes that were frequently altered in their methylation in association with colon cancer. These included 147 hypermethylated and 27 hypomethylated genes. Of the hypermethylated genes, 10 were hypermethylated in 100% of colon cancers and many others were hypermethylated in more than 50% of colon cancers.[103]

While epigenetic alterations are found in cancers, the epigenetic alterations in DNA repair genes, causing reduced expression of DNA repair proteins, may be of particular importance. Such alterations may occur early in progression to cancer and are a possible cause of the genetic instability characteristic of cancers.[104][105][106]

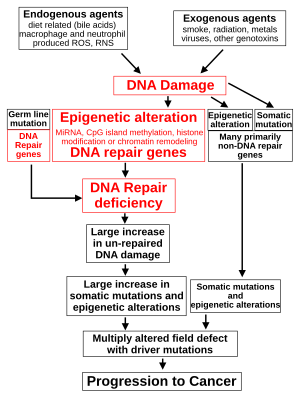

Reduced expression of DNA repair genes disrupts DNA repair. This is shown in the figure at the 4th level from the top. (In the figure, red wording indicates the central role of DNA damage and defects in DNA repair in progression to cancer.) When DNA repair is deficient DNA damage remains in cells at a higher than usual level (5th level) and causes increased frequencies of mutation and/or epimutation (6th level). Mutation rates increase substantially in cells defective in DNA mismatch repair[107][108] or in homologous recombinational repair (HRR).[109] Chromosomal rearrangements and aneuploidy also increase in HRR defective cells.[110]

Higher levels of DNA damage cause increased mutation (right side of figure) and increased epimutation. During repair of DNA double strand breaks, or repair of other DNA damage, incompletely cleared repair sites can cause epigenetic gene silencing.[111][112]

Deficient expression of DNA repair proteins due to an inherited mutation can increase cancer risks. Individuals with an inherited impairment in any of 34 DNA repair genes (see article DNA repair-deficiency disorder) have increased cancer risk, with some defects ensuring a 100% lifetime chance of cancer (e.g. p53 mutations).[113] Germ line DNA repair mutations are noted on the figure's left side. However, such germline mutations (which cause highly penetrant cancer syndromes) are the cause of only about 1 percent of cancers.[114]

In sporadic cancers, deficiencies in DNA repair are occasionally caused by a mutation in a DNA repair gene but are much more frequently caused by epigenetic alterations that reduce or silence expression of DNA repair genes. This is indicated in the figure at the 3rd level. Many studies of heavy metal-induced carcinogenesis show that such heavy metals cause a reduction in expression of DNA repair enzymes, some through epigenetic mechanisms. DNA repair inhibition is proposed to be a predominant mechanism in heavy metal-induced carcinogenicity. In addition, frequent epigenetic alterations of the DNA sequences code for small RNAs called microRNAs (or miRNAs). miRNAs do not code for proteins, but can "target" protein-coding genes and reduce their expression.

Cancers usually arise from an assemblage of mutations and epimutations that confer a selective advantage leading to clonal expansion (see Field defects in progression to cancer). Mutations, however, may not be as frequent in cancers as epigenetic alterations. An average cancer of the breast or colon can have about 60 to 70 protein-altering mutations, of which about three or four may be "driver" mutations and the remaining ones may be "passenger" mutations.[115]

Metastasis

Metastasis is the spread of cancer to other locations in the body. The dispersed tumors are called metastatic tumors, while the original is called the primary tumor. Almost all cancers can metastasize.[39] Most cancer deaths are due to cancer that has metastasized.[40]

Metastasis is common in the late stages of cancer and it can occur via the blood or the lymphatic system or both. The typical steps in metastasis are local invasion, intravasation into the blood or lymph, circulation through the body, extravasation into the new tissue, proliferation and angiogenesis. Different types of cancers tend to metastasize to particular organs, but overall the most common places for metastases to occur are the lungs, liver, brain and the bones.[39]

Metabolism

Normal cells typically generate only about 30% of energy from glycolysis,[116] whereas most cancers rely on glycolysis for energy production (Warburg effect).[117][118] But a minority of cancer types rely on oxidative phosphorylation as the primary energy source, including lymphoma, leukemia, and endometrial cancer.[119] Even in these cases, however, the use of glycolysis as an energy source rarely exceeds 60%.[116] A few cancers use glutamine as the major energy source, partly because it provides nitrogen required for nucleotide (DNA, RNA) synthesis.[120] Cancer stem cells often use oxidative phosphorylation or glutamine as a primary energy source.[121]

Diagnosis

Most cancers are initially recognized either because of the appearance of signs or symptoms or through screening.[122] Neither of these leads to a definitive diagnosis, which requires the examination of a tissue sample by a pathologist.[123] People with suspected cancer are investigated with medical tests. These commonly include blood tests, X-rays, (contrast) CT scans and endoscopy.

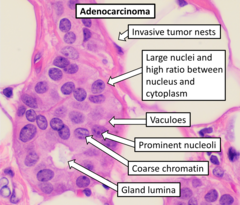

The tissue diagnosis from the biopsy indicates the type of cell that is proliferating, its histological grade, genetic abnormalities and other features. Together, this information is useful to evaluate the prognosis and to choose the best treatment.

Cytogenetics and immunohistochemistry are other types of tissue tests. These tests provide information about molecular changes (such as mutations, fusion genes and numerical chromosome changes) and may thus also indicate the prognosis and best treatment.

Cancer diagnosis can cause psychological distress and psychosocial interventions, such as talking therapy, may help people with this.[124] Some people choose to disclose the diagnosis widely; others prefer to keep the information private, especially shortly after the diagnosis, or to disclose it only partially or to selected people.[125]

Classification

Cancers are classified by the type of cell that the tumor cells resemble and is therefore presumed to be the origin of the tumor. These types include:

- Carcinoma: Cancers derived from epithelial cells. This group includes many of the most common cancers and include nearly all those in the breast, prostate, lung, pancreas and colon. Most of these are of the adenocarcinoma type, which means that the cancer has gland-like differentiation.

- Sarcoma: Cancers arising from connective tissue (i.e. bone, cartilage, fat, nerve), each of which develops from cells originating in mesenchymal cells outside the bone marrow.

- Lymphoma and leukemia: These two classes arise from hematopoietic (blood-forming) cells that leave the marrow and tend to mature in the lymph nodes and blood, respectively.[126]

- Germ cell tumor: Cancers derived from pluripotent cells, most often presenting in the testicle or the ovary (seminoma and dysgerminoma, respectively).

- Blastoma: Cancers derived from immature "precursor" cells or embryonic tissue.

Cancers are usually named using -carcinoma, -sarcoma or -blastoma as a suffix, with the Latin or Greek word for the organ or tissue of origin as the root. For example, cancers of the liver parenchyma arising from malignant epithelial cells is called hepatocarcinoma, while a malignancy arising from primitive liver precursor cells is called a hepatoblastoma and a cancer arising from fat cells is called a liposarcoma. For some common cancers, the English organ name is used. For example, the most common type of breast cancer is called ductal carcinoma of the breast. Here, the adjective ductal refers to the appearance of cancer under the microscope, which suggests that it has originated in the milk ducts.

Benign tumors (which are not cancers) are named using -oma as a suffix with the organ name as the root. For example, a benign tumor of smooth muscle cells is called a leiomyoma (the common name of this frequently occurring benign tumor in the uterus is fibroid). Confusingly, some types of cancer use the -noma suffix, examples including melanoma and seminoma.

Some types of cancer are named for the size and shape of the cells under a microscope, such as giant cell carcinoma, spindle cell carcinoma and small-cell carcinoma.

- An invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast (pale area at the center) surrounded by spikes of whitish scar tissue and yellow fatty tissue

- An invasive colorectal carcinoma (top center) in a colectomy specimen

- A squamous-cell carcinoma (the whitish tumor) near the bronchi in a lung specimen

- A large invasive ductal carcinoma in a mastectomy specimen

- Squamous cell carcinoma with typical histopathology features.

- Histopathology of small-cell carcinoma, with typical findings.[127]

Prevention

Cancer prevention is defined as active measures to decrease cancer risk.[129] The vast majority of cancer cases are due to environmental risk factors. Many of these environmental factors are controllable lifestyle choices. Thus, cancer is generally preventable.[130] Between 70% and 90% of common cancers are due to environmental factors and therefore potentially preventable.[131]

Greater than 30% of cancer deaths could be prevented by avoiding risk factors including: tobacco, excess weight/obesity, poor diet, physical inactivity, alcohol, sexually transmitted infections and air pollution.[132] Further, poverty could be considered as an indirect risk factor in human cancers.[133] Not all environmental causes are controllable, such as naturally occurring background radiation and cancers caused through hereditary genetic disorders and thus are not preventable via personal behavior.

In 2019, ~44% of all cancer deaths – or ~4.5 M deaths or ~105 million lost disability-adjusted life years – were due to known clearly preventable risk factors, led by smoking, alcohol use and high BMI, according to a GBD systematic analysis.[128]

Dietary

While many dietary recommendations have been proposed to reduce cancer risks, the evidence to support them is not definitive.[14][134] The primary dietary factors that increase risk are obesity and alcohol consumption. Diets low in fruits and vegetables and high in red meat have been implicated but reviews and meta-analyses do not come to a consistent conclusion.[135][136] A 2014 meta-analysis found no relationship between fruits and vegetables and cancer.[137] Coffee is associated with a reduced risk of liver cancer.[138] Studies have linked excessive consumption of red or processed meat to an increased risk of breast cancer, colon cancer and pancreatic cancer, a phenomenon that could be due to the presence of carcinogens in meats cooked at high temperatures.[139][140] In 2015 the IARC reported that eating processed meat (e.g., bacon, ham, hot dogs, sausages) and, to a lesser degree, red meat was linked to some cancers.[141][142]

Dietary recommendations for cancer prevention typically include an emphasis on vegetables, fruit, whole grains and fish and an avoidance of processed and red meat (beef, pork, lamb), animal fats, pickled foods and refined carbohydrates.[14][134]

Medication

Medications can be used to prevent cancer in a few circumstances.[143] In the general population, NSAIDs reduce the risk of colorectal cancer; however, due to cardiovascular and gastrointestinal side effects, they cause overall harm when used for prevention.[144] Aspirin has been found to reduce the risk of death from cancer by about 7%.[145] COX-2 inhibitors may decrease the rate of polyp formation in people with familial adenomatous polyposis; however, it is associated with the same adverse effects as NSAIDs.[146] Daily use of tamoxifen or raloxifene reduce the risk of breast cancer in high-risk women.[147] The benefit versus harm for 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor such as finasteride is not clear.[148]

Vitamin supplementation does not appear to be effective at preventing cancer.[149] While low blood levels of vitamin D are correlated with increased cancer risk,[150][151][152] whether this relationship is causal and vitamin D supplementation is protective is not determined.[153][154] One 2014 review found that supplements had no significant effect on cancer risk.[154] Another 2014 review concluded that vitamin D3 may decrease the risk of death from cancer (one fewer death in 150 people treated over 5 years), but concerns with the quality of the data were noted.[155]

Beta-Carotene supplementation increases lung cancer rates in those who are high risk.[156] Folic acid supplementation is not effective in preventing colon cancer and may increase colon polyps.[157] Selenium supplementation has not been shown to reduce the risk of cancer.[158]

Vaccination

Vaccines have been developed that prevent infection by some carcinogenic viruses.[159] Human papillomavirus vaccine (Gardasil and Cervarix) decrease the risk of developing cervical cancer.[159] The hepatitis B vaccine prevents infection with hepatitis B virus and thus decreases the risk of liver cancer.[159] The administration of human papillomavirus and hepatitis B vaccinations is recommended where resources allow.[160]

Screening

Unlike diagnostic efforts prompted by symptoms and medical signs, cancer screening involves efforts to detect cancer after it has formed, but before any noticeable symptoms appear.[161] This may involve physical examination, blood or urine tests or medical imaging.[161]

Cancer screening is not available for many types of cancers. Even when tests are available, they may not be recommended for everyone. Universal screening or mass screening involves screening everyone.[162] Selective screening identifies people who are at higher risk, such as people with a family history.[162] Several factors are considered to determine whether the benefits of screening outweigh the risks and the costs of screening.[161] These factors include:

- Possible harms from the screening test: for example, X-ray images involve exposure to potentially harmful ionizing radiation

- The likelihood of the test correctly identifying cancer

- The likelihood that cancer is present: Screening is not normally useful for rare cancers.

- Possible harms from follow-up procedures

- Whether suitable treatment is available

- Whether early detection improves treatment outcomes

- Whether cancer will ever need treatment

- Whether the test is acceptable to the people: If a screening test is too burdensome (for example, extremely painful), then people will refuse to participate.[162]

- Cost

Recommendations

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issues recommendations for various cancers:

- Strongly recommends cervical cancer screening in women who are sexually active and have a cervix at least until the age of 65.[163]

- Recommend that Americans be screened for colorectal cancer via fecal occult blood testing, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy starting at age 50 until age 75.[164]

- Evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against screening for skin cancer,[165] oral cancer,[166] lung cancer,[167] or prostate cancer in men under 75.[168]

- Routine screening is not recommended for bladder cancer,[169] testicular cancer,[170] ovarian cancer,[171] pancreatic cancer,[172] or prostate cancer.[173]

- Recommends mammography for breast cancer screening every two years from ages 50–74, but does not recommend either breast self-examination or clinical breast examination.[174] A 2013 Cochrane review concluded that breast cancer screening by mammography had no effect in reducing mortality because of overdiagnosis and overtreatment.[175]

Japan

Screens for gastric cancer using photofluorography due to the high incidence there.[25]

Genetic testing

| Gene | Cancer types |

|---|---|

| BRCA1, BRCA2 | Breast, ovarian, pancreatic |

| HNPCC, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS1, PMS2 | Colon, uterine, small bowel, stomach, urinary tract |

Genetic testing for individuals at high-risk of certain cancers is recommended by unofficial groups.[160][176] Carriers of these mutations may then undergo enhanced surveillance, chemoprevention, or preventative surgery to reduce their subsequent risk.[176]

Management

Many treatment options for cancer exist. The primary ones include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, hormonal therapy, targeted therapy and palliative care. Which treatments are used depends on the type, location and grade of the cancer as well as the patient's health and preferences. The treatment intent may or may not be curative.[citation needed]

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the treatment of cancer with one or more cytotoxic anti-neoplastic drugs (chemotherapeutic agents) as part of a standardized regimen. The term encompasses a variety of drugs, which are divided into broad categories such as alkylating agents and antimetabolites.[177] Traditional chemotherapeutic agents act by killing cells that divide rapidly, a critical property of most cancer cells.

It was found that providing combined cytotoxic drugs is better than a single drug, a process called the combination therapy, which has an advantage in the statistics of survival and response to the tumor and in the progress of the disease.[178] A Cochrane review concluded that combined therapy was more effective to treat metastasized breast cancer. However, generally it is not certain whether combination chemotherapy leads to better health outcomes, when both survival and toxicity are considered.[179]

Targeted therapy is a form of chemotherapy that targets specific molecular differences between cancer and normal cells. The first targeted therapies blocked the estrogen receptor molecule, inhibiting the growth of breast cancer. Another common example is the class of Bcr-Abl inhibitors, which are used to treat chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).[4] Currently, targeted therapies exist for many of the most common cancer types, including bladder cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, kidney cancer, leukemia, liver cancer, lung cancer, lymphoma, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, skin cancer, and thyroid cancer as well as other cancer types.[180]

The efficacy of chemotherapy depends on the type of cancer and the stage. In combination with surgery, chemotherapy has proven useful in cancer types including breast cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, osteogenic sarcoma, testicular cancer, ovarian cancer and certain lung cancers.[181] Chemotherapy is curative for some cancers, such as some leukemias,[182][183] ineffective in some brain tumors,[184] and needless in others, such as most non-melanoma skin cancers.[185] The effectiveness of chemotherapy is often limited by its toxicity to other tissues in the body. Even when chemotherapy does not provide a permanent cure, it may be useful to reduce symptoms such as pain or to reduce the size of an inoperable tumor in the hope that surgery will become possible in the future.

Radiation

Radiation therapy involves the use of ionizing radiation in an attempt to either cure or improve symptoms. It works by damaging the DNA of cancerous tissue, causing mitotic catastrophe resulting in the death of the cancer cells.[186] To spare normal tissues (such as skin or organs, which radiation must pass through to treat the tumor), shaped radiation beams are aimed from multiple exposure angles to intersect at the tumor, providing a much larger dose there than in the surrounding, healthy tissue. As with chemotherapy, cancers vary in their response to radiation therapy.[187][188][189]

Radiation therapy is used in about half of cases. The radiation can be either from internal sources (brachytherapy) or external sources. The radiation is most commonly low energy X-rays for treating skin cancers, while higher energy X-rays are used for cancers within the body.[190] Radiation is typically used in addition to surgery and or chemotherapy. For certain types of cancer, such as early head and neck cancer, it may be used alone.[191] Radiation therapy after surgery for brain metastases has been shown to not improve overall survival in patients compared to surgery alone.[192] For painful bone metastasis, radiation therapy has been found to be effective in about 70% of patients.[191]

Surgery

Surgery is the primary method of treatment for most isolated, solid cancers and may play a role in palliation and prolongation of survival. It is typically an important part of definitive diagnosis and staging of tumors, as biopsies are usually required. In localized cancer, surgery typically attempts to remove the entire mass along with, in certain cases, the lymph nodes in the area. For some types of cancer this is sufficient to eliminate the cancer.[181]

Palliative care

Palliative care is treatment that attempts to help the patient feel better and may be combined with an attempt to treat the cancer. Palliative care includes action to reduce physical, emotional, spiritual and psycho-social distress. Unlike treatment that is aimed at directly killing cancer cells, the primary goal of palliative care is to improve quality of life.

People at all stages of cancer treatment typically receive some kind of palliative care. In some cases, medical specialty professional organizations recommend that patients and physicians respond to cancer only with palliative care.[193] This applies to patients who:[194]

- display low performance status, implying limited ability to care for themselves[193]

- received no benefit from prior evidence-based treatments[193]

- are not eligible to participate in any appropriate clinical trial[193]

- no strong evidence implies that treatment would be effective[193]

Palliative care may be confused with hospice and therefore only indicated when people approach end of life. Like hospice care, palliative care attempts to help the patient cope with their immediate needs and to increase comfort. Unlike hospice care, palliative care does not require people to stop treatment aimed at the cancer.

Multiple national medical guidelines recommend early palliative care for patients whose cancer has produced distressing symptoms or who need help coping with their illness. In patients first diagnosed with metastatic disease, palliative care may be immediately indicated. Palliative care is indicated for patients with a prognosis of less than 12 months of life even given aggressive treatment.[195][196][197]

Immunotherapy

A variety of therapies using immunotherapy, stimulating or helping the immune system to fight cancer, have come into use since 1997. Approaches include antibodies, checkpoint therapy, and adoptive cell transfer.[198]

Laser therapy

Laser therapy uses high-intensity light to treat cancer by shrinking or destroying tumors or precancerous growths. Lasers are most commonly used to treat superficial cancers that are on the surface of the body or the lining of internal organs. It is used to treat basal cell skin cancer and the very early stages of others like cervical, penile, vaginal, vulvar, and non-small cell lung cancer. It is often combined with other treatments, such as surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy. Laser-induced interstitial thermotherapy (LITT), or interstitial laser photocoagulation, uses lasers to treat some cancers using hyperthermia, which uses heat to shrink tumors by damaging or killing cancer cells. Laser are more precise than surgery and cause less damage, pain, bleeding, swelling, and scarring. A disadvantage is surgeons must have specialized training. It may be more expensive than other treatments.[199]

Alternative medicine

Complementary and alternative cancer treatments are a diverse group of therapies, practices and products that are not part of conventional medicine.[200] "Complementary medicine" refers to methods and substances used along with conventional medicine, while "alternative medicine" refers to compounds used instead of conventional medicine.[201] Most complementary and alternative medicines for cancer have not been studied or tested using conventional techniques such as clinical trials. Some alternative treatments have been investigated and shown to be ineffective but still continue to be marketed and promoted. Cancer researcher Andrew J. Vickers stated, "The label 'unproven' is inappropriate for such therapies; it is time to assert that many alternative cancer therapies have been 'disproven'."[202]

Prognosis

Survival rates vary by cancer type and by the stage at which it is diagnosed, ranging from majority survival to complete mortality five years after diagnosis. Once a cancer has metastasized, prognosis normally becomes much worse. About half of patients receiving treatment for invasive cancer (excluding carcinoma in situ and non-melanoma skin cancers) die from that cancer or its treatment.[25] A majority of cancer deaths are due to metastases of the primary tumor.[204]

Survival is worse in the developing world,[25] partly because the types of cancer that are most common there are harder to treat than those associated with developed countries.[205]

Those who survive cancer develop a second primary cancer at about twice the rate of those never diagnosed.[206] The increased risk is believed to be due to the random chance of developing any cancer, the likelihood of surviving the first cancer, the same risk factors that produced the first cancer, unwanted side effects of treating the first cancer (particularly radiation therapy), and better compliance with screening.[206]

Predicting short- or long-term survival depends on many factors. The most important are the cancer type and the patient's age and overall health. Those who are frail with other health problems have lower survival rates than otherwise healthy people. Centenarians are unlikely to survive for five years even if treatment is successful. People who report a higher quality of life tend to survive longer.[207] People with lower quality of life may be affected by depression and other complications and/or disease progression that both impairs quality and quantity of life. Additionally, patients with worse prognoses may be depressed or report poorer quality of life because they perceive that their condition is likely to be fatal.

People with cancer have an increased risk of blood clots in their veins which can be life-threatening.[208] The use of blood thinners such as heparin decrease the risk of blood clots but have not been shown to increase survival in people with cancer.[208] People who take blood thinners also have an increased risk of bleeding.[208]

Although extremely rare, some forms of cancer, even from an advanced stage, can heal spontaneously. This phenomenon is known as the spontaneous remission.[209]

Epidemiology

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Estimates are that in 2018, 18.1 million new cases of cancer and 9.6 million deaths occur globally.[211] About 20% of males and 17% of females will get cancer at some point in time while 13% of males and 9% of females will die from it.[211]

In 2008, approximately 12.7 million cancers were diagnosed (excluding non-melanoma skin cancers and other non-invasive cancers)[25] and in 2010 nearly 7.98 million people died.[212] Cancers account for approximately 16% of deaths. The most common as of 2018[update] are lung cancer (1.76 million deaths), colorectal cancer (860,000) stomach cancer (780,000), liver cancer (780,000), and breast cancer (620,000).[2] This makes invasive cancer the leading cause of death in the developed world and the second leading in the developing world.[25] Over half of cases occur in the developing world.[25]

Deaths from cancer were 5.8 million in 1990.[212] Deaths have been increasing primarily due to longer lifespans and lifestyle changes in the developing world.[25] The most significant risk factor for developing cancer is age.[213] Although it is possible for cancer to strike at any age, most patients with invasive cancer are over 65.[213] According to cancer researcher Robert A. Weinberg, "If we lived long enough, sooner or later we all would get cancer."[214] Some of the association between aging and cancer is attributed to immunosenescence,[215] errors accumulated in DNA over a lifetime[216] and age-related changes in the endocrine system.[217] Aging's effect on cancer is complicated by factors such as DNA damage and inflammation promoting it and factors such as vascular aging and endocrine changes inhibiting it.[218]

Some slow-growing cancers are particularly common, but often are not fatal. Autopsy studies in Europe and Asia showed that up to 36% of people have undiagnosed and apparently harmless thyroid cancer at the time of their deaths and that 80% of men develop prostate cancer by age 80.[219][220] As these cancers do not cause the patient's death, identifying them would have represented overdiagnosis rather than useful medical care.

The three most common childhood cancers are leukemia (34%), brain tumors (23%) and lymphomas (12%).[221] In the United States cancer affects about 1 in 285 children.[222] Rates of childhood cancer increased by 0.6% per year between 1975 and 2002 in the United States[223] and by 1.1% per year between 1978 and 1997 in Europe.[221] Death from childhood cancer decreased by half between 1975 and 2010 in the United States.[222]

History

Cancer has existed for all of human history.[224] The earliest written record regarding cancer is from c. 1600 BC in the Egyptian Edwin Smith Papyrus and describes breast cancer.[224] Hippocrates (c. 460 BC – c. 370 BC) described several kinds of cancer, referring to them with the Greek word καρκίνος karkinos (crab or crayfish).[224] This name comes from the appearance of the cut surface of a solid malignant tumor, with "the veins stretched on all sides as the animal the crab has its feet, whence it derives its name".[225] Galen stated that "cancer of the breast is so called because of the fancied resemblance to a crab given by the lateral prolongations of the tumor and the adjacent distended veins".[226]: 738 Celsus (c. 25 BC – 50 AD) translated karkinos into the Latin cancer, also meaning crab and recommended surgery as treatment.[224] Galen (2nd century AD) disagreed with the use of surgery and recommended purgatives instead.[224] These recommendations largely stood for 1000 years.[224]

In the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries, it became acceptable for doctors to dissect bodies to discover the cause of death.[227] The German professor Wilhelm Fabry believed that breast cancer was caused by a milk clot in a mammary duct. The Dutch professor Francois de la Boe Sylvius, a follower of Descartes, believed that all disease was the outcome of chemical processes and that acidic lymph fluid was the cause of cancer. His contemporary Nicolaes Tulp believed that cancer was a poison that slowly spreads and concluded that it was contagious.[228]

The physician John Hill described tobacco sniffing as the cause of nose cancer in 1761.[227] This was followed by the report in 1775 by British surgeon Percivall Pott that chimney sweeps' carcinoma, a cancer of the scrotum, was a common disease among chimney sweeps.[229] With the widespread use of the microscope in the 18th century, it was discovered that the 'cancer poison' spread from the primary tumor through the lymph nodes to other sites ("metastasis"). This view of the disease was first formulated by the English surgeon Campbell De Morgan between 1871 and 1874.[230]

Society and culture

Although many diseases (such as heart failure) may have a worse prognosis than most cases of cancer, cancer is the subject of widespread fear and taboos. The euphemism of "a long illness" to describe cancers leading to death is still commonly used in obituaries, rather than naming the disease explicitly, reflecting an apparent stigma.[231] Cancer is also euphemised as "the C-word";[232][233][234] Macmillan Cancer Support uses the term to try to lessen the fear around the disease.[235] In Nigeria, one local name for cancer translates into English as "the disease that cannot be cured".[236] This deep belief that cancer is necessarily a difficult and usually deadly disease is reflected in the systems chosen by society to compile cancer statistics: the most common form of cancer—non-melanoma skin cancers, accounting for about one-third of cancer cases worldwide, but very few deaths[237][238]—are excluded from cancer statistics specifically because they are easily treated and almost always cured, often in a single, short, outpatient procedure.[239]

Western conceptions of patients' rights for people with cancer include a duty to fully disclose the medical situation to the person, and the right to engage in shared decision-making in a way that respects the person's own values. In other cultures, other rights and values are preferred. For example, most African cultures value whole families rather than individualism. In parts of Africa, a diagnosis is commonly made so late that cure is not possible, and treatment, if available at all, would quickly bankrupt the family. As a result of these factors, African healthcare providers tend to let family members decide whether, when and how to disclose the diagnosis, and they tend to do so slowly and circuitously, as the person shows interest and an ability to cope with the grim news.[236] People from Asian and South American countries also tend to prefer a slower, less candid approach to disclosure than is idealized in the United States and Western Europe, and they believe that sometimes it would be preferable not to be told about a cancer diagnosis.[236] In general, disclosure of the diagnosis is more common than it was in the 20th century, but full disclosure of the prognosis is not offered to many patients around the world.[236]

In the United States and some other cultures, cancer is regarded as a disease that must be "fought" to end the "civil insurrection"; a War on Cancer was declared in the US. Military metaphors are particularly common in descriptions of cancer's human effects, and they emphasize both the state of the patient's health and the need to take immediate, decisive actions himself rather than to delay, to ignore or to rely entirely on others. The military metaphors also help rationalize radical, destructive treatments.[240][241] In the 1970s, a relatively popular alternative cancer treatment in the US was a specialized form of talk therapy, based on the idea that cancer was caused by a bad attitude.[242] People with a "cancer personality"—depressed, repressed, self-loathing and afraid to express their emotions—were believed to have manifested cancer through subconscious desire. Some psychotherapists claimed that treatment to change the patient's outlook on life would cure the cancer.[242] Among other effects, this belief allowed society to blame the victim for having caused the cancer (by "wanting" it) or having prevented its cure (by not becoming a sufficiently happy, fearless and loving person).[243] It also increased patients' anxiety, as they incorrectly believed that natural emotions of sadness, anger or fear shorten their lives.[243] The idea was ridiculed by Susan Sontag, who published Illness as Metaphor while recovering from treatment for breast cancer in 1978.[242] Although the original idea is now generally regarded as nonsense, the idea partly persists in a reduced form with a widespread, but incorrect, belief that deliberately cultivating a habit of positive thinking will increase survival.[243] This notion is particularly strong in breast cancer culture.[243]

One idea about why people with cancer are blamed or stigmatized, called the just-world hypothesis, is that blaming cancer on the patient's actions or attitudes allows the blamers to regain a sense of control. This is based upon the blamers' belief that the world is fundamentally just and so any dangerous illness, like cancer, must be a type of punishment for bad choices, because in a just world, bad things would not happen to good people.[244]

Economic effect

The total health care expenditure on cancer in the US was estimated to be $80.2 billion in 2015.[245] Even though cancer-related health care expenditure have increased in absolute terms during recent decades, the share of health expenditure devoted to cancer treatment has remained close to 5% between the 1960s and 2004.[246][247] A similar pattern has been observed in Europe where about 6% of all health care expenditure are spent on cancer treatment.[248][249] In addition to health care expenditure and financial toxicity, cancer causes indirect costs in the form of productivity losses due to sick days, permanent incapacity and disability as well as premature death during working age. Cancer causes also costs for informal care. Indirect costs and informal care costs are typically estimated to exceed or equal the health care costs of cancer.[250][249]

Workplace

In the United States, cancer is included as a protected condition by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), mainly due to the potential for cancer having discriminating effects on workers.[251] Discrimination in the workplace could occur if an employer holds a false belief that a person with cancer is not capable of doing a job properly, and may ask for more sick leave than other employees. Employers may also make hiring or firing decisions based on misconceptions about cancer disabilities, if present. The EEOC provides interview guidelines for employers, as well as lists of possible solutions for assessing and accommodating employees with cancer.[251]

Divorce gender disparity

Women are six times more likely to be separated or divorced soon after a diagnosis of cancer or multiple sclerosis than men. Doctors in neuro-oncology practices noticed that divorce occurred almost exclusively when the wife was the patient.[252][253]

Research

Because cancer is a class of diseases,[254][255] it is unlikely that there will ever be a single "cure for cancer" any more than there will be a single treatment for all infectious diseases.[256] Angiogenesis inhibitors were once incorrectly thought to have potential as a "silver bullet" treatment applicable to many types of cancer.[257] Angiogenesis inhibitors and other cancer therapeutics are used in combination to reduce cancer morbidity and mortality.[258]

Experimental cancer treatments are studied in clinical trials to compare the proposed treatment to the best existing treatment. Treatments that succeeded in one cancer type can be tested against other types.[259] Diagnostic tests are under development to better target the right therapies to the right patients, based on their individual biology.[260]

Cancer research focuses on the following issues:

- Agents (e.g. viruses) and events (e.g. mutations) that cause or facilitate genetic changes in cells destined to become cancer.

- The precise nature of the genetic damage and the genes that are affected by it.

- The consequences of those genetic changes on the biology of the cell, both in generating the defining properties of a cancer cell and in facilitating additional genetic events that lead to further progression of the cancer.

The improved understanding of molecular biology and cellular biology due to cancer research has led to new treatments for cancer since US President Richard Nixon declared the "War on Cancer" in 1971. Since then, the country has spent over $200 billion on cancer research, including resources from public and private sectors.[261] The cancer death rate (adjusting for size and age of the population) declined by five percent between 1950 and 2005.[262]

Competition for financial resources appears to have suppressed the creativity, cooperation, risk-taking and original thinking required to make fundamental discoveries, unduly favoring low-risk research into small incremental advancements over riskier, more innovative research. Other consequences of competition appear to be many studies with dramatic claims whose results cannot be replicated and perverse incentives that encourage grantee institutions to grow without making sufficient investments in their own faculty and facilities.[263][262][264][265]

Virotherapy, which uses convert viruses, is being studied.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a worry that cancer research and treatment are slowing down.[266][267]

On 2 December 2023 Nano Today published a groundbreaking discovery involving "NK cell-engaging nanodrones" for targeted cancer treatment. The development of "NK cell-engaging nanodrones" represents a significant leap forward in cancer treatment, showcasing how cutting-edge nanotechnology and immunotherapy can be combined to target and eliminate cancer cells with unprecedented precision. These nanodrones are designed to harness the power of natural killer (NK) cells, which play a crucial role in the body's immune response against tumors. By directing these NK cells specifically to the sites of tumors, the nanodrones can effectively concentrate the immune system's attack on the cancer cells, potentially leading to better outcomes for patients.[268]

The key innovation here lies in the use of protein cage nanoparticle-based systems. These systems are engineered to carry signals that attract NK cells directly to the tumor, overcoming one of the major challenges in cancer immunotherapy: ensuring that the immune cells find and attack only the cancer cells without harming healthy tissue. This targeted approach not only increases the efficacy of the treatment but also minimizes side effects, a common concern with broader-acting cancer therapies.[268]

Pregnancy

Cancer affects approximately 1 in 1,000 pregnant women. The most common cancers found during pregnancy are the same as the most common cancers found in non-pregnant women during childbearing ages: breast cancer, cervical cancer, leukemia, lymphoma, melanoma, ovarian cancer and colorectal cancer.[269]

Diagnosing a new cancer in a pregnant woman is difficult, in part because any symptoms are commonly assumed to be a normal discomfort associated with pregnancy. As a result, cancer is typically discovered at a somewhat later stage than average. Some imaging procedures, such as MRIs (magnetic resonance imaging), CT scans, ultrasounds and mammograms with fetal shielding are considered safe during pregnancy; some others, such as PET scans, are not.[269]

Treatment is generally the same as for non-pregnant women. However, radiation and radioactive drugs are normally avoided during pregnancy, especially if the fetal dose might exceed 100 cGy. In some cases, some or all treatments are postponed until after birth if the cancer is diagnosed late in the pregnancy. Early deliveries are often used to advance the start of treatment. Surgery is generally safe, but pelvic surgeries during the first trimester may cause miscarriage. Some treatments, especially certain chemotherapy drugs given during the first trimester, increase the risk of birth defects and pregnancy loss (spontaneous abortions and stillbirths).[269]

Elective abortions are not required and, for the most common forms and stages of cancer, do not improve the mother's survival. In a few instances, such as advanced uterine cancer, the pregnancy cannot be continued and in others, the patient may end the pregnancy so that she can begin aggressive chemotherapy.[269]

Some treatments can interfere with the mother's ability to give birth vaginally or to breastfeed.[269] Cervical cancer may require birth by Caesarean section. Radiation to the breast reduces the ability of that breast to produce milk and increases the risk of mastitis. Also, when chemotherapy is given after birth, many of the drugs appear in breast milk, which could harm the baby.[269]

Other animals

Veterinary oncology, concentrating mainly on cats and dogs, is a growing specialty in wealthy countries and the major forms of human treatment such as surgery and radiotherapy may be offered. The most common types of cancer differ, but the cancer burden seems at least as high in pets as in humans. Animals, typically rodents, are often used in cancer research and studies of natural cancers in larger animals may benefit research into human cancer.[270]

Across wild animals, there is still limited data on cancer. Nonetheless, a study published in 2022, explored cancer risk in (non-domesticated) zoo mammals, belonging to 191 species, 110,148 individual, demonstrated that cancer is a ubiquitous disease of mammals and it can emerge anywhere along the mammalian phylogeny.[271] This research also highlighted that cancer risk is not uniformly distributed along mammals. For instance, species in the order Carnivora are particularly prone to be affected by cancer (e.g. over 25% of clouded leopards, bat-eared foxes and red wolves die of cancer), while ungulates (especially even-toed ungulates) appear to face consistently low cancer risks.

In non-humans, a few types of transmissible cancer have also been described, wherein the cancer spreads between animals by transmission of the tumor cells themselves. This phenomenon is seen in dogs with Sticker's sarcoma (also known as canine transmissible venereal tumor), and in Tasmanian devils with devil facial tumour disease (DFTD).[272]

References

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c "Cancer – Signs and symptoms". NHS Choices. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k "Cancer". World Health Organization. 12 September 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Sundaram C, Harikumar KB, Tharakan ST, Lai OS, Sung B, Aggarwal BB (September 2008). "Cancer is a preventable disease that requires major lifestyle changes". Pharmaceutical Research. 25 (9): 2097–116. doi:10.1007/s11095-008-9661-9. PMC 2515569. PMID 18626751.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c "Targeted Cancer Therapies". cancer.gov. National Cancer Institute. 26 February 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b "SEER Stat Fact Sheets: All Cancer Sites". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c Kocarnik, JM; others (2022). "Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for 29 Cancer Groups From 2010 to 2019. A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019". JAMA Oncology. 8 (3): 420–444. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.6987. PMC 8719276. PMID 34967848.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c d "Defining Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 17 September 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ "Obesity and Cancer Risk". National Cancer Institute. 3 January 2012. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ Джаясекара Х., Макиннис Р.Дж., Комната R, Английский DR (май 2016 г.). «Длительное употребление алкоголя и риск рака молочной железы, верхних отделов пищеварительного тракта и колоректального рака: систематический обзор и метаанализ» . Алкоголь и алкоголизм . 51 (3): 315–30. дои : 10.1093/alcalc/agv110 . ПМИД 26400678 .

- ^ «Глобальное бремя рака, связанное с инфекциями, в 2018 году: анализ заболеваемости во всем мире — The Lancet Global Health» .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и Всемирный доклад о раке, 2014 год . Всемирная организация здравоохранения. 2014. стр. Глава 1.1. ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9 . Архивировано из оригинала 12 июля 2017 года.

- ^ «Наследственность и рак» . Американское онкологическое общество . Архивировано из оригинала 2 августа 2013 года . Проверено 22 июля 2013 г.

- ^ «Как диагностируется рак?» . Американское онкологическое общество . 29 января 2013 года. Архивировано из оригинала 14 июля 2014 года . Проверено 10 июня 2014 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Куши Л.Х., Дойл С., Маккалоу М., Рок К.Л., Демарк-Ваннефрид В., Бандера Е.В., Гапстур С., Патель А.В., Эндрюс К., Ганслер Т. (2012). «Руководство Американского онкологического общества по питанию и физической активности для профилактики рака: снижение риска развития рака с помощью здорового питания и физической активности» . CA: Журнал рака для врачей . 62 (1): 30–67. дои : 10.3322/caac.20140 . ПМИД 22237782 . S2CID 2067308 .

- ^ Паркин Д.М., Бойд Л., Уокер Л.С. (декабрь 2011 г.). «16. Доля рака, обусловленная образом жизни и факторами окружающей среды в Великобритании в 2010 году» . Британский журнал рака . 105 (Приложение 2): S77–81. дои : 10.1038/bjc.2011.489 . ПМК 3252065 . ПМИД 22158327 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Всемирный доклад о раке, 2014 год . Всемирная организация здравоохранения. 2014. С. Глава 4.7. ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9 . Архивировано из оригинала 12 июля 2017 года.

- ^ Гётше ПК, Йоргенсен К.Дж. (июнь 2013 г.). «Скрининг рака молочной железы с помощью маммографии» . Кокрановская база данных систематических обзоров . 2013 (6): CD001877. дои : 10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub5 . ПМК 6464778 . ПМИД 23737396 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Всемирный доклад о раке, 2014 год . Всемирная организация здравоохранения. 2014. С. Глава 1.3. ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9 . Архивировано из оригинала 12 июля 2017 года.

- ^ ГБД ; и др. (Соавторы по вопросам заболеваемости и травматизма и распространенности) (8 октября 2016 г.). «Глобальная, региональная и национальная заболеваемость, распространенность и количество лет жизни с инвалидностью по 310 заболеваниям и травмам, 1990–2015 гг.: систематический анализ для исследования глобального бремени болезней 2015 г.» . Ланцет . 388 (10053): 1545–1602. дои : 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6 . ПМК 5055577 . ПМИД 27733282 .