Вырубка лесов

Вырубка леса или вырубка леса – это удаление и уничтожение леса или древостоев с земель, которые затем переводятся в нелесные виды использования. [1] Вырубка лесов может включать в себя преобразование лесных угодий под фермы , ранчо или в городское пользование. В настоящее время около 31% поверхности суши Земли покрыто лесами . [2] Это на одну треть меньше, чем лесной покров до развития сельского хозяйства, причем половина этих потерь произошла в прошлом столетии. [3] от 15 до 18 миллионов гектаров леса (площадь размером с Бангладеш Ежегодно уничтожается ). В среднем каждую минуту вырубается 2400 деревьев. [4] Оценки масштабов вырубки лесов в тропиках сильно различаются . [5] [6] В 2019 году почти треть общей потери древесного покрова, или 3,8 миллиона гектаров, произошла во влажных тропических девственных лесах . Это участки зрелых тропических лесов , которые особенно важны для биоразнообразия и хранения углерода . [7] [8]

Прямой причиной большей части вырубки лесов является сельское хозяйство. [9] В 2018 году более 80% вырубки лесов пришлось на сельское хозяйство. [10] Леса превращаются в плантации для производства кофе , пальмового масла , каучука и других популярных продуктов. [11] скота Выпас также способствует вырубке лесов. Дальнейшими движущими силами являются деревообрабатывающая промышленность ( заготовка леса ), урбанизация и горнодобывающая промышленность . Последствия изменения климата являются еще одной причиной повышенного риска лесных пожаров (см. Вырубка лесов и изменение климата ).

Deforestation results in habitat destruction which in turn leads to biodiversity loss. Deforestation also leads to extinction of animals and plants, changes to the local climate, and displacement of indigenous people who live in forests. Deforested regions often also suffer from other environmental problems such as desertification and soil erosion.

Another problem is that deforestation reduces the uptake of carbon dioxide (carbon sequestration) from the atmosphere. This reduces the potential of forests to assist with climate change mitigation. The role of forests in capturing and storing carbon and mitigating climate change is also important for the agricultural sector.[12] The reason for this linkage is because the effects of climate change on agriculture pose new risks to global food systems.[12]

Since 1990, it is estimated that some 420 million hectares of forest have been lost through conversion to other land uses, although the rate of deforestation has decreased over the past three decades. Between 2015 and 2020, the rate of deforestation was estimated at 10 million hectares per year, down from 16 million hectares per year in the 1990s. The area of primary forest worldwide has decreased by over 80 million hectares since 1990. More than 100 million hectares of forests are adversely affected by forest fires, pests, diseases, invasive species, drought and adverse weather events.[13]

Definition

Deforestation is defined as the conversion of forest to other land uses (regardless of whether it is human-induced).[14]

Deforestation and forest area net change are not the same: the latter is the sum of all forest losses (deforestation) and all forest gains (forest expansion) in a given period. Net change, therefore, can be positive or negative, depending on whether gains exceed losses, or vice versa.[14]

Current status

The FAO estimates that the global forest carbon stock has decreased 0.9%, and tree cover 4.2% between 1990 and 2020.[15]: 16, 52

| Region | 1990 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Europe (including Russia) | 158.7 | 172.4 |

| North America | 136.6 | 140.0 |

| Africa | 94.3 | 80.9 |

| South and Southeast Asia combined | 45.8 | 41.5 |

| Oceania | 33.4 | 33.1 |

| Central America | 5.0 | 4.1 |

| South America | 161.8 | 144.8 |

As of 2019 there is still disagreement about whether the global forest is shrinking or not: "While above-ground biomass carbon stocks are estimated to be declining in the tropics, they are increasing globally due to increasing stocks in temperate and boreal forest.[16]: 385

Deforestation in many countries—both naturally occurring[17] and human-induced—is an ongoing issue.[18] Between 2000 and 2012, 2.3 million square kilometres (890,000 square miles) of forests around the world were cut down.[19] Deforestation and forest degradation continue to take place at alarming rates, which contributes significantly to the ongoing loss of biodiversity.[12]

Deforestation is more extreme in tropical and subtropical forests in emerging economies. More than half of all plant and land animal species in the world live in tropical forests.[21] As a result of deforestation, only 6.2 million square kilometres (2.4 million square miles) remain of the original 16 million square kilometres (6 million square miles) of tropical rainforest that formerly covered the Earth.[19] More than 3.6 million hectares of virgin tropical forest was lost in 2018.[22]

The global annual net loss of trees is estimated to be approximately 10 billion.[23][24] According to the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020 the global average annual deforested land in the 2015–2020 demi-decade was 10 million hectares and the average annual forest area net loss in the 2000–2010 decade was 4.7 million hectares.[14] The world has lost 178 million ha of forest since 1990, which is an area about the size of Libya.[14]

An analysis of global deforestation patterns in 2021 showed that patterns of trade, production, and consumption drive deforestation rates in complex ways. While the location of deforestation can be mapped, it does not always match where the commodity is consumed. For example, consumption patterns in G7 countries are estimated to cause an average loss of 3.9 trees per person per year. In other words, deforestation can be directly related to imports—for example, coffee.[25][26]

In 2023, the Global Forest Watch reported a 9% decline in tropical primary forest loss compared to the previous year, with significant regional reductions in Brazil and Colombia overshadowed by increases elsewhere, leading to a 3.2% rise in global deforestation. Massive wildfires in Canada, exacerbated by climate change, contributed to a 24% increase in global tree cover loss, highlighting the ongoing threats to forests essential for carbon storage and biodiversity. Despite some progress, the overall trends in forest destruction and climate impacts remain off track.[27]

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report stated in 2022: “Over 420 million ha of forest were lost to deforestation from 1990 to 2020; more than 90% of that loss took place in tropical areas (high confidence), threatening biodiversity, environmental services, livelihoods of forest communities and resilience to climate shocks (high confidence).”[28]

Rates of deforestation

Global deforestation[31] sharply accelerated around 1852.[32][33] As of 1947, the planet had 15 to 16 million km2 (5.8 to 6.2 million sq mi) of mature tropical forests,[34] but by 2015, it was estimated that about half of these had been destroyed.[35][21][36] Total land coverage by tropical rainforests decreased from 14% to 6%. Much of this loss happened between 1960 and 1990, when 20% of all tropical rainforests were destroyed. At this rate, extinction of such forests is projected to occur by the mid-21st century.[citation needed]

In the early 2000s, some scientists predicted that unless significant measures (such as seeking out and protecting old growth forests that have not been disturbed)[34] are taken on a worldwide basis, by 2030 there will only be 10% remaining,[32][36] with another 10% in a degraded condition.[32] 80% will have been lost, and with them hundreds of thousands of irreplaceable species.[32]

Estimates vary widely as to the extent of deforestation in the tropics.[5][6] In 2019, the world lost nearly 12 million hectares of tree cover. Nearly a third of that loss, 3.8 million hectares, occurred within humid tropical primary forests, areas of mature rainforest that are especially important for biodiversity and carbon storage. This is equivalent to losing an area of primary forest the size of a football pitch every six seconds.[7][8]

Rates of change

A 2002 analysis of satellite imagery suggested that the rate of deforestation in the humid tropics (approximately 5.8 million hectares per year) was roughly 23% lower than the most commonly quoted rates.[40] A 2005 report by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated that although the Earth's total forest area continued to decrease at about 13 million hectares per year, the global rate of deforestation had been slowing.[41][42] On the other hand, a 2005 analysis of satellite images reveals that deforestation of the Amazon rainforest is twice as fast as scientists previously estimated.[43][44]

From 2010 to 2015, worldwide forest area decreased by 3.3 million ha per year, according to FAO. During this five-year period, the biggest forest area loss occurred in the tropics, particularly in South America and Africa. Per capita forest area decline was also greatest in the tropics and subtropics but is occurring in every climatic domain (except in the temperate) as populations increase.[45]

An estimated 420 million ha of forest has been lost worldwide through deforestation since 1990, but the rate of forest loss has declined substantially. In the most recent five-year period (2015–2020), the annual rate of deforestation was estimated at 10 million ha, down from 12 million ha in 2010–2015.[14]

Africa had the largest annual rate of net forest loss in 2010–2020, at 3.9 million ha, followed by South America, at 2.6 million ha. The rate of net forest loss has increased in Africa in each of the three decades since 1990. It has declined substantially in South America, however, to about half the rate in 2010–2020 compared with 2000–2010. Asia had the highest net gain of forest area in 2010–2020, followed by Oceania and Europe. Nevertheless, both Europe and Asia recorded substantially lower rates of net gain in 2010–2020 than in 2000–2010. Oceania experienced net losses of forest area in the decades 1990–2000 and 2000–2010.[14]

Some claim that rainforests are being destroyed at an ever-quickening pace.[47] The London-based Rainforest Foundation notes that "the UN figure is based on a definition of forest as being an area with as little as 10% actual tree cover, which would therefore include areas that are actually savanna-like ecosystems and badly damaged forests".[48] Other critics of the FAO data point out that they do not distinguish between forest types,[49] and that they are based largely on reporting from forestry departments of individual countries,[50] which do not take into account unofficial activities like illegal logging.[51] Despite these uncertainties, there is agreement that destruction of rainforests remains a significant environmental problem.

The rate of net forest loss declined from 7.8 million ha per year in the decade 1990–2000 to 5.2 million ha per year in 2000–2010 and 4.7 million ha per year in 2010–2020. The rate of decline of net forest loss slowed in the most recent decade due to a reduction in the rate of forest expansion.[14]

Reforestation and afforestation

In many parts of the world, especially in East Asian countries, reforestation and afforestation are increasing the area of forested lands.[52] The amount of forest has increased in 22 of the world's 50 most forested nations. Asia as a whole gained 1 million hectares of forest between 2000 and 2005. Tropical forest in El Salvador expanded more than 20% between 1992 and 2001. Based on these trends, one study projects that global forestation will increase by 10%—an area the size of India—by 2050.[53] 36% of globally planted forest area is in East Asia – around 950,000 square kilometers. From those 87% are in China.[54]

Status by region

Rates of deforestation vary around the world. Up to 90% of West Africa's coastal rainforests have disappeared since 1900.[55] Madagascar has lost 90% of its eastern rainforests.[56][57] In South Asia, about 88% of the rainforests have been lost.[58]

Mexico, India, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Burma, Malaysia, Bangladesh, China, Sri Lanka, Laos, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, Guinea, Ghana and the Ivory Coast, have lost large areas of their rainforest.[59][60]

Much of what remains of the world's rainforests is in the Amazon basin, where the Amazon Rainforest covers approximately 4 million square kilometres.[61] Some 80% of the deforestation of the Amazon can be attributed to cattle ranching,[62] as Brazil is the largest exporter of beef in the world.[63] The Amazon region has become one of the largest cattle ranching territories in the world.[64] The regions with the highest tropical deforestation rate between 2000 and 2005 were Central America—which lost 1.3% of its forests each year—and tropical Asia.[48] In Central America, two-thirds of lowland tropical forests have been turned into pasture since 1950 and 40% of all the rainforests have been lost in the last 40 years.[65] Brazil has lost 90–95% of its Mata Atlântica forest.[66] Deforestation in Brazil increased by 88% for the month of June 2019, as compared with the previous year.[67] However, Brazil still destroyed 1.3 million hectares in 2019.[7] Brazil is one of several countries that have declared their deforestation a national emergency.[68][69]Paraguay was losing its natural semi-humid forests in the country's western regions at a rate of 15,000 hectares at a randomly studied 2-month period in 2010.[70] In 2009, Paraguay's parliament refused to pass a law that would have stopped cutting of natural forests altogether.[71]

As of 2007, less than 50% of Haiti's forests remained.[72]

From 2015 to 2019, the rate of deforestation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo doubled.[73] In 2021, deforestation of the Congolese rainforest increased by 5%.[74]

The World Wildlife Fund's ecoregion project catalogues habitat types throughout the world, including habitat loss such as deforestation, showing for example that even in the rich forests of parts of Canada such as the Mid-Continental Canadian forests of the prairie provinces half of the forest cover has been lost or altered.

In 2011, Conservation International listed the top 10 most endangered forests, characterized by having all lost 90% or more of their original habitat, and each harboring at least 1500 endemic plant species (species found nowhere else in the world).[75]

As of 2015[update], it is estimated that 70% of the world's forests are within one kilometer of a forest edge, where they are most prone to human interference and destruction.[76][77]

Top 10 Most Endangered Forests in 2011[75] Endangered forest Region Remaining habitat Predominate vegetation type Notes Indo-Burma Asia-Pacific 5% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Rivers, floodplain wetlands, mangrove forests. Burma, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, India.[78] New Caledonia Asia-Pacific 5% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests See note for region covered.[79] Sundaland Asia-Pacific 7% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Western half of the Indo-Malayan archipelago including southern Borneo and Sumatra.[80] Philippines Asia-Pacific 7% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Forests over the entire country including 7,100 islands.[81] Atlantic Forest South America 8% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Forests along Brazil's Atlantic coast, extends to parts of Paraguay, Argentina and Uruguay.[82] Mountains of Southwest China Asia-Pacific 8% Temperate coniferous forest See note for region covered.[83] California Floristic Province North America 10% Tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests See note for region covered.[84] Coastal Forests of Eastern Africa Africa 10% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Mozambique, Tanzania, Kenya, Somalia.[85] Madagascar & Indian Ocean Islands Africa 10% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Madagascar, Mauritius, Reunion, Seychelles, Comoros.[86] Eastern Afromontane Africa 11% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests

Montane grasslands and shrublandsForests scattered along the eastern edge of Africa, from Saudi Arabia in the north to Zimbabwe in the south.[87]

By country

Deforestation in particular countries:

Causes

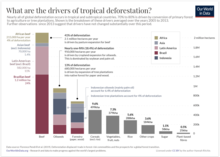

Agricultural expansion continues to be the main driver of deforestation and forest fragmentation and the associated loss of forest biodiversity.[12] Large-scale commercial agriculture (primarily cattle ranching and cultivation of soya bean and oil palm) accounted for 40 percent of tropical deforestation between 2000 and 2010, and local subsistence agriculture for another 33 percent.[12] Trees are cut down for use as building material, timber or sold as fuel (sometimes in the form of charcoal or timber), while cleared land is used as pasture for livestock and agricultural crops.

The vast majority of agricultural activity resulting in deforestation is subsidized by government tax revenue.[88] Disregard of ascribed value, lax forest management, and deficient environmental laws are some of the factors that lead to large-scale deforestation.

The types of drivers vary greatly depending on the region in which they take place. The regions with the greatest amount of deforestation for livestock and row crop agriculture are Central and South America, while commodity crop deforestation was found mainly in Southeast Asia. The region with the greatest forest loss due to shifting agriculture was sub-Saharan Africa.[89]

Agriculture

The overwhelming direct cause of deforestation is agriculture.[9] Subsistence farming is responsible for 48% of deforestation; commercial agriculture is responsible for 32%; logging is responsible for 14%, and fuel wood removals make up 5%.[9]

More than 80% of deforestation was attributed to agriculture in 2018.[10] Forests are being converted to plantations for coffee, tea, palm oil, rice, rubber, and various other popular products.[11] The rising demand for certain products and global trade arrangements causes forest conversions, which ultimately leads to soil erosion.[90] The top soil oftentimes erodes after forests are cleared which leads to sediment increase in rivers and streams.

Most deforestation also occurs in tropical regions. The estimated amount of total land mass used by agriculture is around 38%.[91]

Since 1960, roughly 15% of the Amazon has been removed with the intention of replacing the land with agricultural practices.[92] It is no coincidence that Brazil has recently become the world's largest beef exporter at the same time that the Amazon rainforest is being clear cut.[93]

Another prevalent method of agricultural deforestation is slash-and-burn agriculture, which was primarily used by subsistence farmers in tropical regions but has now become increasingly less sustainable. The method does not leave land for continuous agricultural production but instead cuts and burns small plots of forest land which are then converted into agricultural zones. The farmers then exploit the nutrients in the ashes of the burned plants.[94][95] As well as, intentionally set fires can possibly lead to devastating measures when unintentionally spreading fire to more land, which can result in the destruction of the protective canopy.[96]

The repeated cycle of low yields and shortened fallow periods eventually results in less vegetation being able to grow on once burned lands and a decrease in average soil biomass.[97] In small local plots sustainability is not an issue because of longer fallow periods and lesser overall deforestation. The relatively small size of the plots allowed for no net input of CO2 to be released.[98]

Livestock ranching

Consumption and production of beef is the primary driver of deforestation in the Amazon, with around 80% of all converted land being used to rear cattle.[99][100] 91% of Amazon land deforested since 1970 has been converted to cattle ranching.[101][102]

Livestock ranching requires large portions of land to raise herds of animals and livestock crops for consumer needs. According to the World Wildlife Fund, "Extensive cattle ranching is the number one culprit of deforestation in virtually every Amazon country, and it accounts for 80% of current deforestation."[103]

The cattle industry is responsible for a significant amount of methane emissions since 60% of all mammals on earth are livestock cows.[104][105] Replacing forest land with pastures creates a loss of forest stock, which leads to the implication of increased greenhouse gas emissions by burning agriculture methodologies and land-use change.[106]

Wood industry

A large contributing factor to deforestation is the lumber industry. A total of almost 4 million hectares (9.9 million acres) of timber,[107] or about 1.3% of all forest land, is harvested each year. In addition, the increasing demand for low-cost timber products only supports the lumber company to continue logging.[108]

Experts do not agree on whether industrial logging is an important contributor to global deforestation.[109][110] Some argue that poor people are more likely to clear forest because they have no alternatives, others that the poor lack the ability to pay for the materials and labour needed to clear forest.[109]

Economic development

Other causes of contemporary deforestation may include corruption of government institutions,[111][112][113] the inequitable distribution of wealth and power,[114] population growth[115] and overpopulation,[116][117] and urbanization.[118][119] The impact of population growth on deforestation has been contested. One study found that population increases due to high fertility rates were a primary driver of tropical deforestation in only 8% of cases.[120] In 2000 the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) found that "the role of population dynamics in a local setting may vary from decisive to negligible", and that deforestation can result from "a combination of population pressure and stagnating economic, social and technological conditions".[115]

Globalization is often viewed as another root cause of deforestation,[121][122] though there are cases in which the impacts of globalization (new flows of labor, capital, commodities, and ideas) have promoted localized forest recovery.[123]

The degradation of forest ecosystems has also been traced to economic incentives that make forest conversion appear more profitable than forest conservation.[124] Many important forest functions have no markets, and hence, no economic value that is readily apparent to the forests' owners or the communities that rely on forests for their well-being.[124]

Some commentators have noted a shift in the drivers of deforestation over the past 30 years.[125] Whereas deforestation was primarily driven by subsistence activities and government-sponsored development projects like transmigration in countries like Indonesia and colonization in Latin America, India, Java, and so on, during the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, by the 1990s the majority of deforestation was caused by industrial factors, including extractive industries, large-scale cattle ranching, and extensive agriculture.[126] Since 2001, commodity-driven deforestation, which is more likely to be permanent, has accounted for about a quarter of all forest disturbance, and this loss has been concentrated in South America and Southeast Asia.[127]

As the human population grows, new homes, communities, and expansions of cities will occur, leading to an increase in roads to connect these communities. Rural roads promote economic development but also facilitate deforestation.[128] About 90% of the deforestation has occurred within 100 km of roads in most parts of the Amazon.[129]

Mining

The importance of mining as a cause of deforestation increased quickly in the beginning the 21st century, among other because of increased demand for minerals. The direct impact of mining is relatively small, but the indirect impacts are much more significant. More than a third of the earth's forests are possibly impacted, at some level and in the years 2001–2021, "755,861 km2... ...had been deforested by causes indirectly related to mining activities alongside other deforestation drivers (based on data from WWF)"[130]

Climate change

Another cause of deforestation is due to the effects of climate change: More wildfires,[132] insect outbreaks, invasive species, and more frequent extreme weather events (such as storms) are factors that increase deforestation.[133]

A study suggests that "tropical, arid and temperate forests are experiencing a significant decline in resilience, probably related to increased water limitations and climate variability" which may shift ecosystems towards critical transitions and ecosystem collapses.[131] By contrast, "boreal forests show divergent local patterns with an average increasing trend in resilience, probably benefiting from warming and CO2 fertilization, which may outweigh the adverse effects of climate change".[131] It has been proposed that a loss of resilience in forests "can be detected from the increased temporal autocorrelation (TAC) in the state of the system, reflecting a decline in recovery rates due to the critical slowing down (CSD) of system processes that occur at thresholds".[131]

23% of tree cover losses result from wildfires and climate change increase their frequency and power.[134] The rising temperatures cause massive wildfires especially in the Boreal forests. One possible effect is the change of the forest composition.[135] Deforestation can also cause forests to become more fire prone through mechanisms such as logging.[136]

Military causes

Operations in war can also cause deforestation. For example, in the 1945 Battle of Okinawa, bombardment and other combat operations reduced a lush tropical landscape into "a vast field of mud, lead, decay and maggots".[137]

Deforestation can also result from the intentional tactics of military forces. Clearing forests became an element in the Russian Empire's successful conquest of the Caucasus in the mid-19th century.[138]The British (during the Malayan Emergency) and the United States (in the Korean War[139] and in the Vietnam War) used defoliants (like Agent Orange or others).[140][141][142][need quotation to verify] The destruction of forests in Vietnam War is one of the most commonly used examples of ecocide, including by Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme, lawyers, historians and other academics.[143][144][145]

Impacts

On atmosphere and climate

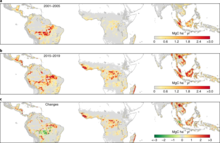

Deforestation is a major contributor to climate change.[148][149][150] It is often cited as one of the major causes of the enhanced greenhouse effect. Recent calculations suggest that CO2 emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (excluding peatland emissions) contribute about 12% of total anthropogenic CO2 emissions, with a range from 6% to 17%.[151] A 2022 study shows annual carbon emissions from tropical deforestation have doubled during the last two decades and continue to increase: by 0.97 ± 0.16 PgC (petagrams of carbon, i.e. billions of tons) per year in 2001–2005 to 1.99 ± 0.13 PgC per year in 2015–2019.[152][147]

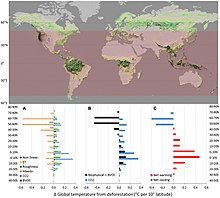

According to a review, north of 50°N, large scale deforestation leads to an overall net global cooling; but deforestation in the tropics leads to substantial warming: not just due to CO2 impacts, but also due to other biophysical mechanisms (making carbon-centric metrics inadequate). Moreover, it suggests that standing tropical forests help cool the average global temperature by more than 1 °C.[153][146] According to a later study, deforestation in northern latitudes can also increase warming, while the conclusion about cooling from deforestation in these areas made by previous studies results from the failure of models to properly capture the effects of evapotranspiration.[154]

The incineration and burning of forest plants to clear land releases large amounts of CO2, which contributes to global warming.[155] Scientists also state that tropical deforestation releases 1.5 billion tons of carbon each year into the atmosphere.[156]

Carbon sink or source

A study suggests logged and structurally degraded tropical forests are carbon sources for at least a decade – even when recovering[clarification needed] – due to larger carbon losses from soil organic matter and deadwood, indicating that the tropical forest carbon sink (at least in South Asia) "may be much smaller than previously estimated", contradicting that "recovering logged and degraded tropical forests are net carbon sinks".[157]

Forests are an important part of the global carbon cycle because trees and plants absorb carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. Therefore, they play an important role in climate change mitigation.[159]: 37 By removing the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide from the air, forests function as terrestrial carbon sinks, meaning they store large amounts of carbon in the form of biomass, encompassing roots, stems, branches, and leaves. Throughout their lifespan, trees continue to sequester carbon, storing atmospheric CO2 long-term.[160] Sustainable forest management, afforestation, reforestation are therefore important contributions to climate change mitigation.

An important consideration in such efforts is that forests can turn from sinks to carbon sources.[161][162][163] In 2019 forests took up a third less carbon than they did in the 1990s, due to higher temperatures, droughts and deforestation. The typical tropical forest may become a carbon source by the 2060s.[164]

Researchers have found that, in terms of environmental services, it is better to avoid deforestation than to allow for deforestation to subsequently reforest, as the former leads to irreversible effects in terms of biodiversity loss and soil degradation.[165] Furthermore, the probability that legacy carbon will be released from soil is higher in younger boreal forest.[166] Global greenhouse gas emissions caused by damage to tropical rainforests may have been substantially underestimated until around 2019.[167] Additionally, the effects of af- or reforestation will be farther in the future than keeping existing forests intact.[168] It takes much longer − several decades − for the benefits for global warming to manifest to the same carbon sequestration benefits from mature trees in tropical forests and hence from limiting deforestation.[169] Therefore, scientists consider "the protection and recovery of carbon-rich and long-lived ecosystems, especially natural forests" to be "the major climate solution".[170]

The planting of trees on marginal crop and pasture lands helps to incorporate carbon from atmospheric CO

2 into biomass.[171][172] For this carbon sequestration process to succeed the carbon must not return to the atmosphere from biomass burning or rotting when the trees die.[173] To this end, land allotted to the trees must not be converted to other uses. Alternatively, the wood from them must itself be sequestered, e.g., via biochar, bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, landfill or stored by use in construction.

Earth offers enough room to plant an additional 1.2 trillion trees.[174] Planting and protecting them would offset some 10 years of CO2 emissions and sequester 205 billion tons of carbon.[175] This approach is supported by the Trillion Tree Campaign. Restoring all degraded forests world-wide would capture about 205 billion tons of carbon in total, which is[when?] about two-thirds of all carbon emissions.[176][177]

Life expectancy of forests varies throughout the world, influenced by tree species, site conditions, and natural disturbance patterns. In some forests, carbon may be stored for centuries, while in other forests, carbon is released with frequent stand replacing fires. Forests that are harvested prior to stand replacing events allow for the retention of carbon in manufactured forest products such as lumber.[178] However, only a portion of the carbon removed from logged forests ends up as durable goods and buildings. The remainder ends up as sawmill by-products such as pulp, paper, and pallets.[179] If all new construction globally utilized 90% wood products, largely via adoption of mass timber in low rise construction, this could sequester 700 million net tons of carbon per year.[180][181] This is in addition to the elimination of carbon emissions from the displaced construction material such as steel or concrete, which are carbon-intense to produce.

A meta-analysis found that mixed species plantations would increase carbon storage alongside other benefits of diversifying planted forests.[182]

Although a bamboo forest stores less total carbon than a mature forest of trees, a bamboo plantation sequesters carbon at a much faster rate than a mature forest or a tree plantation. Therefore, the farming of bamboo timber may have significant carbon sequestration potential.[183]

The Food and Agriculure Organization (FAO) reported that: "The total carbon stock in forests decreased from 668 gigatonnes in 1990 to 662 gigatonnes in 2020".[158]: 11 In Canada's boreal forests as much as 80% of the total carbon is stored in the soils as dead organic matter.[184]

Carbon offset programs are planting millions of fast-growing trees per year to reforest tropical lands.[citation needed] Over their typical 40-year lifetime, one million of these trees can sequester up to one million tons of carbon dioxide.[185][186]

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report says: "Secondary forest regrowth and restoration of degraded forests and non-forest ecosystems can play a large role in carbon sequestration (high confidence) with high resilience to disturbances and additional benefits such as enhanced biodiversity."[187][188]

At the beginning of the 21st century, interest in reforestation grew over its potential to mitigate climate change. Even without displacing agriculture and cities, earth can[clarification needed] sustain almost one billion hectares of new forests. This would remove 25% of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and reduce its concentration to levels that existed in the early 20th century. A temperature rise of 1.5 degrees would reduce the area suitable for forests by 20% by the year 2050 because some tropical areas will become too hot.[189] The countries that have the most forest-ready land are: Russia, Canada, Brazil, Australia, the United States and China.[190]

Impacts on temperature are affected by the location of the forest. For example, reforestation in boreal or subarctic regions has less impact on climate. This is because it substitutes a high-albedo, snow-dominated region with a lower-albedo forest canopy. By contrast, tropical reforestation projects lead to a positive change such as the formation of clouds. These clouds then reflect the sunlight, lowering temperatures.[191]: 1457

Planting trees in tropical climates with wet seasons has another advantage. In such a setting, trees grow more quickly (fixing more carbon) because they can grow year-round. Trees in tropical climates have, on average, larger, brighter, and more abundant leaves than non-tropical climates. A study of the girth of 70,000 trees across Africa has shown that tropical forests fix more carbon dioxide pollution than previously realized. The research suggested almost one-fifth of fossil fuel emissions are absorbed by forests across Africa, Amazonia and Asia. Simon Lewis stated, "Tropical forest trees are absorbing about 18% of the carbon dioxide added to the atmosphere each year from burning fossil fuels, substantially buffering the rate of change."[192]

A 2019 study of the global potential for tree restoration showed that there is space for at least 9 million km2 of new forests worldwide, which is a 25% increase from current conditions.[193] This forested area could store up to 205 gigatons of carbon or 25% of the atmosphere's current carbon pool by reducing CO2 in the atmosphere.[193]On the environment

According to a 2020 study, if deforestation continues at current rates it can trigger a total or almost total extinction of humanity in the next 20 to 40 years. They conclude that "from a statistical point of view... the probability that our civilisation survives itself is less than 10% in the most optimistic scenario." To avoid this collapse, humanity should pass from a civilization dominated by the economy to "cultural society" that "privileges the interest of the ecosystem above the individual interest of its components, but eventually in accordance with the overall communal interest."[194][195]

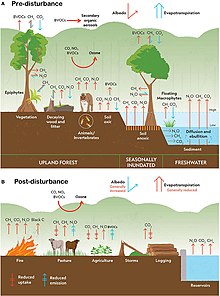

Changes to the water cycle

The water cycle is also affected by deforestation. Trees extract groundwater through their roots and release it into the atmosphere. When part of a forest is removed, the trees no longer transpire this water, resulting in a much drier climate. Deforestation reduces the content of water in the soil and groundwater as well as atmospheric moisture. The dry soil leads to lower water intake for the trees to extract.[196] Deforestation reduces soil cohesion, so that erosion, flooding and landslides ensue.[197][198]

Shrinking forest cover lessens the landscape's capacity to intercept, retain and transpire precipitation. Instead of trapping precipitation, which then percolates to groundwater systems, deforested areas become sources of surface water runoff, which moves much faster than subsurface flows. Forests return most of the water that falls as precipitation to the atmosphere by transpiration. In contrast, when an area is deforested, almost all precipitation is lost as run-off.[199] That quicker transport of surface water can translate into flash flooding and more localized floods than would occur with the forest cover. Deforestation also contributes to decreased evapotranspiration, which lessens atmospheric moisture which in some cases affects precipitation levels downwind from the deforested area, as water is not recycled to downwind forests, but is lost in runoff and returns directly to the oceans. According to one study, in deforested north and northwest China, the average annual precipitation decreased by one third between the 1950s and the 1980s.[200]

Trees, and plants in general, affect the water cycle significantly:[201]

- their canopies intercept a proportion of precipitation, which is then evaporated back to the atmosphere (canopy interception);

- their litter, stems and trunks slow down surface runoff;

- their roots create macropores – large conduits – in the soil that increase infiltration of water;

- they contribute to terrestrial evaporation and reduce soil moisture via transpiration;

- their litter and other organic residue change soil properties that affect the capacity of soil to store water.

- their leaves control the humidity of the atmosphere by transpiring. 99% of the water absorbed by the roots moves up to the leaves and is transpired.[202]

As a result, the presence or absence of trees can change the quantity of water on the surface, in the soil or groundwater, or in the atmosphere. This in turn changes erosion rates and the availability of water for either ecosystem functions or human services. Deforestation on lowland plains moves cloud formation and rainfall to higher elevations.[203]

The forest may have little impact on flooding in the case of large rainfall events, which overwhelm the storage capacity of forest soil if the soils are at or close to saturation.

Tropical rainforests produce about 30% of Earth's fresh water.[204]

Deforestation disrupts normal weather patterns creating hotter and drier weather thus increasing drought, desertification, crop failures, melting of the polar ice caps, coastal flooding and displacement of major vegetation regimes.[205]

Soil erosion

Due to surface plant litter, forests that are undisturbed have a minimal rate of erosion. The rate of erosion occurs from deforestation, because it decreases the amount of litter cover, which provides protection from surface runoff.[206] The rate of erosion is around 2 metric tons per square kilometre.[207][self-published source?] This can be an advantage in excessively leached tropical rain forest soils. Forestry operations themselves also increase erosion through the development of (forest) roads and the use of mechanized equipment.[76]

Deforestation in China's Loess Plateau many years ago has led to soil erosion; this erosion has led to valleys opening up. The increase of soil in the runoff causes the Yellow River to flood and makes it yellow-colored.[207]

Greater erosion is not always a consequence of deforestation, as observed in the southwestern regions of the US. In these areas, the loss of grass due to the presence of trees and other shrubbery leads to more erosion than when trees are removed.[207]

Soils are reinforced by the presence of trees, which secure the soil by binding their roots to soil bedrock. Due to deforestation, the removal of trees causes sloped lands to be more susceptible to landslides.[201]

Other changes to the soil

Clearing forests changes the environment of the microbial communities within the soil, and causes a loss of biodiversity in regards to the microbes since biodiversity is actually highly dependent on soil texture.[208] Although the effect of deforestation has much more profound consequences on sandier soils compared to clay-like soils, the disruptions caused by deforestation ultimately reduces properties of soil such as hydraulic conductivity and water storage, thus reducing the efficiency of water and heat absorption.[208][209] In a simulation of the deforestation process in the Amazon, researchers found that surface and soil temperatures increased by 1 to 3 degrees Celsius demonstrating the loss of the soil's ability to absorb radiation and moisture.[209] Furthermore, soils that are rich in organic decay matter are more susceptible to fire, especially during long droughts.[208]

Changes in soil properties could turn the soil itself into a carbon source rather than a carbon sink.[210]

Biodiversity loss

Deforestation on a human scale results in decline in biodiversity,[211] and on a natural global scale is known to cause the extinction of many species.[212][213] The removal or destruction of areas of forest cover has resulted in a degraded environment with reduced biodiversity.[117] Forests support biodiversity, providing habitat for wildlife;[214] moreover, forests foster medicinal conservation.[215] With forest biotopes being irreplaceable source of new drugs (such as taxol), deforestation can destroy genetic variations (such as crop resistance) irretrievably.[216]

Since the tropical rainforests are the most diverse ecosystems on Earth[217][218] and about 80% of the world's known biodiversity can be found in tropical rainforests,[219][220] removal or destruction of significant areas of forest cover has resulted in a degraded[221] environment with reduced biodiversity.[212][222] Road construction and development of adjacent land, which greatly reduces the area of intact wilderness and causes soil erosion, is a major contributing factor to the loss of biodiversity in tropical regions.[76] A study in Rondônia, Brazil, has shown that deforestation also removes the microbial community which is involved in the recycling of nutrients, the production of clean water and the removal of pollutants.[223]

It has been estimated that 137 plant, animal and insect species go extinct every day due to rainforest deforestation, which equates to 50,000 species a year.[224] Others state that tropical rainforest deforestation is contributing to the ongoing Holocene mass extinction.[225][226] The known extinction rates from deforestation rates are very low, approximately one species per year from mammals and birds, which extrapolates to approximately 23,000 species per year for all species. Predictions have been made that more than 40% of the animal and plant species in Southeast Asia could be wiped out in the 21st century.[227] Such predictions were called into question by 1995 data that show that within regions of Southeast Asia much of the original forest has been converted to monospecific plantations, but that potentially endangered species are few and tree flora remains widespread and stable.[228]

Scientific understanding of the process of extinction is insufficient to accurately make predictions about the impact of deforestation on biodiversity.[229] Most predictions of forestry related biodiversity loss are based on species-area models, with an underlying assumption that as the forest declines species diversity will decline similarly.[230] However, many such models have been proven to be wrong and loss of habitat does not necessarily lead to large scale loss of species.[230] Species-area models are known to overpredict the number of species known to be threatened in areas where actual deforestation is ongoing, and greatly overpredict the number of threatened species that are widespread.[228]

In 2012, a study of the Brazilian Amazon predicts that despite a lack of extinctions thus far, up to 90 percent of predicted extinctions will finally occur in the next 40 years.[231]

Oxygen-supply misconception

Rainforests are widely believed by lay persons to contribute a significant amount of the world's oxygen,[204] although it is now accepted by scientists that rainforests contribute little net oxygen to the atmosphere and deforestation has only a minor effect on atmospheric oxygen levels.[232][233] In fact about 50 percent of oxygen on Earth is produced by algae.[234]

On human health

Deforestation reduces safe working hours for millions of people in the tropics, especially for those performing heavy labour outdoors. Continued global heating and forest loss is expected to amplify these impacts, reducing work hours for vulnerable groups even more.[235] A study conducted from 2002 to 2018 also determined that the increase in temperature as a result of climate change, and the lack of shade due to deforestation, has increased the mortality rate of workers in Indonesia.[236]

Infectious diseases

Deforestation eliminates a great number of species of plants and animals which also often results in exposure of people to zoonotic diseases.[12][237][238] Forest-associated diseases include malaria, Chagas disease (also known as American trypanosomiasis), African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), leishmaniasis, Lyme disease, HIV and Ebola.[12] The majority of new infectious diseases affecting humans, including the SARS-CoV-2 virus that caused the COVID-19 pandemic, are zoonotic and their emergence may be linked to habitat loss due to forest area change and the expansion of human populations into forest areas, which both increase human exposure to wildlife.[12]

Deforestation has been coupled with an increase in the occurrence of disease outbreaks. In Malaysia, thousands of acres of forest have been cleared for pig farms. This has resulted in an increase in the spread of the Nipah virus.[239][240] In Kenya, deforestation has led to an increase in malaria cases which is now the leading cause of morbidity and mortality the country.[241][242] A 2017 study found that deforestation substantially increased the incidence of malaria in Nigeria.[243]

Another pathway through which deforestation affects disease is the relocation and dispersion of disease-carrying hosts. This disease emergence pathway can be called "range expansion", whereby the host's range (and thereby the range of pathogens) expands to new geographic areas.[244] Through deforestation, hosts and reservoir species are forced into neighboring habitats. Accompanying the reservoir species are pathogens that have the ability to find new hosts in previously unexposed regions. As these pathogens and species come into closer contact with humans, they are infected both directly and indirectly. Another example of range expansion due to deforestation and other anthropogenic habitat impacts includes the Capybara rodent in Paraguay.[245]

According to the World Economic Forum, 31% of emerging diseases are linked to deforestation.[246] A publication by the United Nations Environment Programme in 2016 found that deforestation, climate change, and livestock agriculture are among the main causes that increase the risk of zoonotic diseases, that is diseases that pass from animals to humans.[247]

COVID-19 pandemic

Scientists have linked the Coronavirus pandemic to the destruction of nature, especially to deforestation, habitat loss in general and wildlife trade.[248] According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) the Coronavirus disease 2019 is zoonotic, e.g., the virus passed from animals to humans. UNEP concludes that: "The most fundamental way to protect ourselves from zoonotic diseases is to prevent destruction of nature. Where ecosystems are healthy and biodiverse, they are resilient, adaptable and help to regulate diseases.[249]

On the economy and agriculture

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: cites are very old. (June 2020) |

Economic losses due to deforestation in Brazil could reach around 317 billion dollars per year, approximately 7 times higher in comparison to the cost of all commodities produced through deforestation.[250]

The forest products industry is a large part of the economy in both developed and developing countries. Short-term economic gains made by conversion of forest to agriculture, or over-exploitation of wood products, typically leads to a loss of long-term income and long-term biological productivity. West Africa, Madagascar, Southeast Asia and many other regions have experienced lower revenue because of declining timber harvests. Illegal logging causes billions of dollars of losses to national economies annually.[251]

The resilience of human food systems and their capacity to adapt to future change is linked to biodiversity – including dryland-adapted shrub and tree species that help combat desertification, forest-dwelling insects, bats and bird species that pollinate crops, trees with extensive root systems in mountain ecosystems that prevent soil erosion, and mangrove species that provide resilience against flooding in coastal areas.[12] With climate change exacerbating the risks to food systems, the role of forests in capturing and storing carbon and mitigating climate change is important for the agricultural sector.[12]

Monitoring

There are multiple methods that are appropriate and reliable for reducing and monitoring deforestation. One method is the "visual interpretation of aerial photos or satellite imagery that is labor-intensive but does not require high-level training in computer image processing or extensive computational resources".[129] Another method includes hot-spot analysis (that is, locations of rapid change) using expert opinion or coarse resolution satellite data to identify locations for detailed digital analysis with high resolution satellite images.[129] Deforestation is typically assessed by quantifying the amount of area deforested, measured at the present time.From an environmental point of view, quantifying the damage and its possible consequences is a more important task, while conservation efforts are more focused on forested land protection and development of land-use alternatives to avoid continued deforestation.[129] Deforestation rate and total area deforested have been widely used for monitoring deforestation in many regions, including the Brazilian Amazon deforestation monitoring by INPE.[156] A global satellite view is available, an example of land change science monitoring of land cover over time.[252][253]

Satellite imaging has become crucial in obtaining data on levels of deforestation and reforestation. Landsat satellite data, for example, has been used to map tropical deforestation as part of NASA's Landsat Pathfinder Humid Tropical Deforestation Project. The project yielded deforestation maps for the Amazon Basin, Central Africa, and Southeast Asia for three periods in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s.[254]

Greenpeace has mapped out the forests that are still intact[255] and published this information on the internet.[256] World Resources Institute in turn has made a simpler thematic map[257] showing the amount of forests present just before the age of man (8000 years ago) and the current (reduced) levels of forest.[258]

Control

International, national and subnational policies

Policies for forest protection include information and education programs, economic measures to increase revenue returns from authorized activities and measures to increase effectiveness of "forest technicians and forest managers".[259] Poverty and agricultural rent were found to be principal factors leading to deforestation.[260] Contemporary domestic and foreign political decision-makers could possibly create and implement policies whose outcomes ensure that economic activities in critical forests are consistent with their scientifically ascribed value for ecosystem services, climate change mitigation and other purposes.

Such policies may use and organize the development of complementary technical and economic means – including for lower levels of beef production, sales and consumption (which would also have major benefits for climate change mitigation),[261][262] higher levels of specified other economic activities in such areas (such as reforestation, forest protection, sustainable agriculture for specific classes of food products and quaternary work in general), product information requirements, practice- and product-certifications and eco-tariffs, along with the required monitoring and traceability. Inducing the creation and enforcement of such policies could, for instance, achieve a global phase-out of deforestation-associated beef.[263][264][265][additional citation(s) needed] With complex polycentric governance measures, goals like sufficient climate change mitigation as decided with e.g. the Paris Agreement and a stoppage of deforestation by 2030 as decided at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference could be achieved.[266] A study has suggested higher income nations need to reduce imports of tropical forest-related products and help with theoretically forest-related socioeconomic development. Proactive government policies and international forest policies "revisit[ing] and redesign[ing] global forest trade" are needed as well.[267][268]

In 2022 the European parliament approved a bill aiming to stop the import linked with deforestation. This EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), may cause to Brazil, for example, to stop deforestation for agricultural production and begun to "increase productivity on existing agricultural land".[269] The legislation was adopted with some changes by the European Council in May 2023 and is expected to enter into force several weeks after. The bill requires companies who want to import certain types of products to the European Union to prove the production of those commodities is not linked to areas deforested after 31 of December 2020. It prohibits also import of products linked with Human rights abuse. The list of products includes: palm oil, cattle, wood, coffee, cocoa, rubber and soy. Some derivatives of those products are also included: chocolate, furniture, printed paper and several palm oil based derivates.[270][271]

But unfortunately, as the report Bankrolling ecosystem destruction shows,[272] this regulation of product imports is not enough. The European financial sector is investing billions of euros in the destruction of nature. Banks do not respond positively to requests to stop this, which is why the report calls for European regulation in this area to be tightened and for banks to be banned from continuing to finance deforestation.[273]

International pledges

In 2014, about 40 countries signed the New York Declaration on Forests, a voluntary pledge to halve deforestation by 2020 and end it by 2030. The agreement was not legally binding, however, and some key countries, such as Brazil, China, and Russia, did not sign onto it. As a result, the effort failed, and deforestation increased from 2014 to 2020.[274][275]

In November 2021, 141 countries (with around 85% of the world's primary tropical forests and 90% of global tree cover) agreed at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow to the Glasgow Leaders' Declaration on Forests and Land Use, a pledge to end and reverse deforestation by 2030.[275][276][277] The agreement was accompanied by about $19.2 billion in associated funding commitments.[276]

The 2021 Glasgow agreement improved on the New York Declaration by now including Brazil and many other countries that did not sign the 2014 agreement.[275][276] Some key nations with high rates of deforestation (including Malaysia, Cambodia, Laos, Paraguay, and Myanmar) have not signed the Glasgow Declaration.[276] Like the earlier agreement, the Glasgow Leaders' Declaration was entered into outside the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and is thus not legally binding.[276]

In November 2021, the EU executive outlined a draft law requiring companies to prove that the agricultural commodities beef, wood, palm oil, soy, coffee and cocoa destined for the EU's 450 million consumers were not linked to deforestation.[278] In September 2022, the EU Parliament supported and strengthened the plan from the EU's executive with 453 votes to 57.[279]

In 2018 the biggest palm oil trader, Wilmar, decided to control its suppliers to avoid deforestation[280][additional citation(s) needed]

In 2021, over 100 world leaders, representing countries containing more than 85% of the world's forests, committed to halt and reverse deforestation and land degradation by 2030.[281]

Land rights

Indigenous communities have long been the frontline of resistance against deforestation.[282] Transferring rights over land from public domain to its indigenous inhabitants is argued to be a cost-effective strategy to conserve forests.[283] This includes the protection of such rights entitled in existing laws, such as India's Forest Rights Act.[283] The transferring of such rights in China, perhaps the largest land reform in modern times, has been argued to have increased forest cover.[284] In Brazil, forested areas given tenure to indigenous groups have even lower rates of clearing than national parks.[284]

Community concessions in the Congolian rainforests have significantly less deforestation as communities are incentivized to manage the land sustainably, even reducing poverty.[285]

Forest management

Efforts to stop or slow deforestation have been attempted for many centuries because it has long been known that deforestation can cause environmental damage sufficient in some cases to cause societies to collapse. In Tonga, paramount rulers developed policies designed to prevent conflicts between short-term gains from converting forest to farmland and long-term problems forest loss would cause,[286] while during the 17th and 18th centuries in Tokugawa, Japan,[287] the shōguns developed a highly sophisticated system of long-term planning to stop and even reverse deforestation of the preceding centuries through substituting timber by other products and more efficient use of land that had been farmed for many centuries. In 16th-century Germany, landowners also developed silviculture to deal with the problem of deforestation. However, these policies tend to be limited to environments with good rainfall, no dry season and very young soils (through volcanism or glaciation). This is because on older and less fertile soils trees grow too slowly for silviculture to be economic, whilst in areas with a strong dry season there is always a risk of forest fires destroying a tree crop before it matures.

In the areas where "slash-and-burn" is practiced, switching to "slash-and-char" would prevent the rapid deforestation and subsequent degradation of soils. The biochar thus created, given back to the soil, is not only a durable carbon sequestration method, but it also is an extremely beneficial amendment to the soil. Mixed with biomass it brings the creation of terra preta, one of the richest soils on the planet and the only one known to regenerate itself.

Sustainable forest management

Certification, as provided by global certification systems such as Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification and Forest Stewardship Council, contributes to tackling deforestation by creating market demand for timber from sustainably managed forests. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), "A major condition for the adoption of sustainable forest management is a demand for products that are produced sustainably and consumer willingness to pay for the higher costs entailed. [...] By promoting the positive attributes of forest products from sustainably managed forests, certification focuses on the demand side of environmental conservation."[289]

Financial compensations for reducing emissions from deforestation

Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD) in developing countries has emerged as a new potential to complement ongoing climate policies. The idea consists in providing financial compensations for the reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from deforestation and forest degradation".[290] REDD can be seen as an alternative to the emissions trading system as in the latter, polluters must pay for permits for the right to emit certain pollutants (i.e. CO2).

Main international organizations including the United Nations and the World Bank, have begun to develop programs aimed at curbing deforestation. The blanket term Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) describes these sorts of programs, which use direct monetary or other incentives to encourage developing countries to limit and/or roll back deforestation. Funding has been an issue, but at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of the Parties-15 (COP-15) in Copenhagen in December 2009, an accord was reached with a collective commitment by developed countries for new and additional resources, including forestry and investments through international institutions, that will approach US$30 billion for the period 2010–2012.[291]

Significant work is underway on tools for use in monitoring developing countries' adherence to their agreed REDD targets. These tools, which rely on remote forest monitoring using satellite imagery and other data sources, include the Center for Global Development's FORMA (Forest Monitoring for Action) initiative[292] and the Group on Earth Observations' Forest Carbon Tracking Portal.[293] Methodological guidance for forest monitoring was also emphasized at COP-15.[294] The environmental organization Avoided Deforestation Partners leads the campaign for development of REDD through funding from the U.S. government.[295]

History

Prehistory

The Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse[212] was an event that occurred 300 million years ago. Climate change devastated tropical rainforests causing the extinction of many plant and animal species. The change was abrupt, specifically, at this time climate became cooler and drier, conditions that are not favorable to the growth of rainforests and much of the biodiversity within them. Rainforests were fragmented forming shrinking 'islands' further and further apart. Populations such as the sub class Lissamphibia were devastated, whereas Reptilia survived the collapse. The surviving organisms were better adapted to the drier environment left behind and served as legacies in succession after the collapse.[citation needed]

Rainforests once covered 14% of the earth's land surface; now they cover a mere 6% and experts estimate that the last remaining rainforests could be consumed in less than 40 years.[296]Small scale deforestation was practiced by some societies for tens of thousands of years before the beginnings of civilization.[297] The first evidence of deforestation appears in the Mesolithic period.[298] It was probably used to convert closed forests into more open ecosystems favourable to game animals.[297] With the advent of agriculture, larger areas began to be deforested, and fire became the prime tool to clear land for crops. In Europe there is little solid evidence before 7000 BC. Mesolithic foragers used fire to create openings for red deer and wild boar. In Great Britain, shade-tolerant species such as oak and ash are replaced in the pollen record by hazels, brambles, grasses and nettles. Removal of the forests led to decreased transpiration, resulting in the formation of upland peat bogs. Widespread decrease in elm pollen across Europe between 8400 and 8300 BC and 7200–7000 BC, starting in southern Europe and gradually moving north to Great Britain, may represent land clearing by fire at the onset of Neolithic agriculture.

The Neolithic period saw extensive deforestation for farming land.[299][300] Stone axes were being made from about 3000 BC not just from flint, but from a wide variety of hard rocks from across Britain and North America as well. They include the noted Langdale axe industry in the English Lake District, quarries developed at Penmaenmawr in North Wales and numerous other locations. Rough-outs were made locally near the quarries, and some were polished locally to give a fine finish. This step not only increased the mechanical strength of the axe, but also made penetration of wood easier. Flint was still used from sources such as Grimes Graves but from many other mines across Europe.

Evidence of deforestation has been found in Minoan Crete; for example the environs of the Palace of Knossos were severely deforested in the Bronze Age.[301]

Pre-industrial history

Just as archaeologists have shown that prehistoric farming societies had to cut or burn forests before planting, documents and artifacts from early civilizations often reveal histories of deforestation. Some of the most dramatic are eighth century BCE Assyrian reliefs depicting logs being floated downstream from conquered areas to the less forested capital region as spoils of war. Ancient Chinese texts make clear that some areas of the Yellow River valley had already destroyed many of their forests over 2000 years ago and had to plant trees as crops or import them from long distances.[302] In South China much of the land came to be privately owned and used for the commercial growing of timber.[303]

Three regional studies of historic erosion and alluviation in ancient Greece found that, wherever adequate evidence exists, a major phase of erosion follows the introduction of farming in the various regions of Greece by about 500–1,000 years, ranging from the later Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age.[304] The thousand years following the mid-first millennium BC saw serious, intermittent pulses of soil erosion in numerous places. The historic silting of ports along the southern coasts of Asia Minor (e.g. Clarus, and the examples of Ephesus, Priene and Miletus, where harbors had to be abandoned because of the silt deposited by the Meander) and in coastal Syria during the last centuries BC.[305][306]

Easter Island has suffered from heavy soil erosion in recent centuries, aggravated by agriculture and deforestation.[307] The disappearance of the island's trees seems to coincide with a decline of its civilization around the 17th and 18th century. Scholars have attributed the collapse to deforestation and over-exploitation of all resources.[308][309]

The famous silting up of the harbor for Bruges, which moved port commerce to Antwerp, also followed a period of increased settlement growth (and apparently of deforestation) in the upper river basins. In early medieval Riez in upper Provence, alluvial silt from two small rivers raised the riverbeds and widened the floodplain, which slowly buried the Roman settlement in alluvium and gradually moved new construction to higher ground; concurrently the headwater valleys above Riez were being opened to pasturage.[310]

A typical progress trap was that cities were often built in a forested area, which would provide wood for some industry (for example, construction, shipbuilding, pottery). When deforestation occurs without proper replanting, however; local wood supplies become difficult to obtain near enough to remain competitive, leading to the city's abandonment, as happened repeatedly in Ancient Asia Minor. Because of fuel needs, mining and metallurgy often led to deforestation and city abandonment.[311]

With most of the population remaining active in (or indirectly dependent on) the agricultural sector, the main pressure in most areas remained land clearing for crop and cattle farming. Enough wild green was usually left standing (and partially used, for example, to collect firewood, timber and fruits, or to graze pigs) for wildlife to remain viable. The elite's (nobility and higher clergy) protection of their own hunting privileges and game often protected significant woodland.[citation needed]

Major parts in the spread (and thus more durable growth) of the population were played by monastical 'pioneering' (especially by the Benedictine and Commercial orders) and some feudal lords' recruiting farmers to settle (and become tax payers) by offering relatively good legal and fiscal conditions. Even when speculators sought to encourage towns, settlers needed an agricultural belt around or sometimes within defensive walls. When populations were quickly decreased by causes such as the Black Death, the colonization of the Americas,[312] or devastating warfare (for example, Genghis Khan's Mongol hordes in eastern and central Europe, Thirty Years' War in Germany), this could lead to settlements being abandoned. The land was reclaimed by nature, but the secondary forests usually lacked the original biodiversity. The Mongol invasions and conquests alone resulted in the reduction of 700 million tons of carbon from the atmosphere by enabling the re-growth of carbon-absorbing forests on depopulated lands over a significant period of time.[313][314]

From 1100 to 1500 AD, significant deforestation took place in Western Europe as a result of the expanding human population.[315] The large-scale building of wooden sailing ships by European (coastal) naval owners since the 15th century for exploration, colonisation, slave trade, and other trade on the high seas, consumed many forest resources and became responsible for the introduction of numerous bubonic plague outbreaks in the 14th century. Piracy also contributed to the over harvesting of forests, as in Spain. This led to a weakening of the domestic economy after Columbus' discovery of America, as the economy became dependent on colonial activities (plundering, mining, cattle, plantations, trade, etc.)[citation needed]

The massive use of charcoal on an industrial scale in Early Modern Europe was a new type of consumption of western forests.[316] Each of Nelson's Royal Navy war ships at Trafalgar (1805) required 6,000 mature oaks for its construction.[citation needed] In France, Colbert planted oak forests to supply the French navy in the future. When the oak plantations matured in the mid-19th century, the masts were no longer required because shipping had changed.[citation needed]

19th and 20th centuries

Steamboats

In the 19th century, introduction of steamboats in the United States was the cause of deforestation of banks of major rivers, such as the Mississippi River, with increased and more severe flooding one of the environmental results. The steamboat crews cut wood every day from the riverbanks to fuel the steam engines. Between St. Louis and the confluence with the Ohio River to the south, the Mississippi became more wide and shallow, and changed its channel laterally. Attempts to improve navigation by the use of snag pullers often resulted in crews' clearing large trees 100 to 200 feet (61 m) back from the banks. Several French colonial towns of the Illinois Country, such as Kaskaskia, Cahokia and St. Philippe, Illinois, were flooded and abandoned in the late 19th century, with a loss to the cultural record of their archeology.[317]

The impact of deforestation on biogeochemical cycles

Definitions

Deforestation refers to the deliberate clearing and significant modification of forested lands, encompassing activities such as extensive tree cutting, forest thinning, and the use of fire to clear land.[citation needed] This process results in the conversion of forest areas into permanently altered non-forested uses, including agriculture, urban development, or pastureland, fundamentally disrupting the original forest structure and ecosystem.[318]

Biogeochemical cycles describe the pathways by which essential elements and compounds move through Earth's atmosphere, lithosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere.[319] These cycles involve the circulation of nutrients such as carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and water, which are vital for sustaining life by building and maintaining organisms, regulating climate, and supporting ecosystem functions. The balance and flow of these elements enable the production and decomposition of organic material, influence the Earth's climate system, and impact the overall health of global ecosystems.[320] Disruptions in these cycles can lead to significant environmental and ecological changes, underscoring the importance of understanding and managing human impacts on these fundamental natural processes.

Understanding the specific impacts of human actions on biogeochemical cycles is essential for developing effective strategies to mitigate the most disruptive disturbances. By clarifying how activities like deforestation alter these vital cycles, it becomes possible to suggest targeted approaches for reducing environmental and ecological damage, ultimately promoting a more sustainable interaction between human endeavors and the natural world.[321]

Impact on the Carbon Cycle

The carbon stocks remaining in wet tropical forests face significant risks not only from human-driven deforestation but also from potential releases caused by climate change. Despite uncertainties surrounding the exact rates of deforestation, it is likely that substantial carbon losses will occur.[322] Land use carbon fluxes represent significant uncertainties in the global carbon cycle due to unresolved variables such as carbon stocks, the extent of deforestation, degradation, and biomass growth. This is particularly true in the densely populated savannas that are prevalent in the tropics, where precise data are lacking.[321] Combining estimates for additional carbon emissions over the 21st century from various climate change and deforestation scenarios, the projected range is between 101 and 367 gigaton of carbon.[322] This would result in increases in CO2 levels above pre-existing conditions by approximately 29 to 129 parts per million.[322] Given these factors, it is clear that ongoing tropical deforestation will have a major impact on future greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere.

Recent estimates indicate that tropical deforestation releases between 0.4 and 2.5 petagrams (1 petagram = 10^15 grams) of carbon into the atmosphere each year.[323] However, due to various uncertainties, this range could actually be between 1.1 and 3.6 petagrams of carbon per year.[323] Three main factors contribute to this expanded range: the rate at which forests are being cleared, whether the cleared land is used temporarily or permanently, and the initial amount of carbon stored in these forests, including reductions due to human activities like forest thinning or degradation.[323]

The impact of deforestation on the carbon cycle is both profound and far-reaching, significantly contributing to global carbon emissions. By disrupting the natural storage of carbon in forest biomass and soils, deforestation not only releases large quantities of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere but also diminishes the forests' capacity to act as carbon sinks.[324] This exacerbates the greenhouse effect, leading to an increase in global warming and contributing to broader climate change phenomena. Addressing deforestation is critical in the global effort to manage carbon levels and mitigate the adverse effects of climate change, underscoring the need for effective conservation and sustainable land management practices.[325]

Impact on the Nitrogen Cycle

Deforestation significantly impacts soil nitrogen availability, a key factor for soil fertility.[326] In regions converted from forest to cropland, there is a notable decrease in soil nitrogen stocks compared to areas maintained as natural forest or used for agroforestry.[327] A study conducted in White Nile Basin, Ethiopia involved collecting soil samples from different land uses, including natural forests, agroforestry systems, and croplands, across various depths and altitudes.[327] Results showed that both topsoil and subsoil in the forests and agroforestry systems contained higher levels of total nitrogen than those in croplands.[327] This reduction in nitrogen availability following deforestation underscores the challenge of maintaining soil health and fertility in areas subjected to agricultural expansion. Sustaining forested areas or integrating agroforestry practices is crucial for preserving soil nitrogen levels and supporting broader ecological balance.

Impact on the Water Cycle

Deforestation significantly impacts the hydrological cycle in tropical regions, leading to an increased risk of floods and droughts. When forests are cleared, the loss of tree cover disrupts the natural process of evapotranspiration, where water is absorbed by trees and released back into the atmosphere. This disruption results in reduced moisture availability in the atmosphere, which can diminish rainfall and increase the likelihood of drought conditions.[328] Additionally, without the root systems of trees to anchor the soil, deforested areas become highly susceptible to flooding during heavy rains.[328] The absence of vegetation leads to faster runoff of rainwater, preventing it from being absorbed into the ground, exacerbating soil erosion, and increasing the severity of floods.[318]

This alteration of natural water regulatory mechanisms by deforestation not only affects local climate patterns but also poses serious implications for biodiversity, agriculture, and human settlements in these regions. The increased frequency and intensity of droughts and floods can lead to crop failures, water shortages, and increased vulnerability of communities to natural disasters.[329]