Эквадор

Республика Эквадор | |

|---|---|

| Девиз: | |

| Гимн: Salve, Oh Patria (испанский) (английский: «Славься, отечество!» ) | |

Location of Ecuador (dark green) | |

| Capital | Quito[1] 00°13′12″S 78°30′43″W / 0.22000°S 78.51194°W |

| Largest city | Guayaquil[contradictory] |

| Official languages | Spanish[2] |

| Recognized regional languages | Kichwa (Quechua), Shuar and others "are in official use for indigenous peoples"[3] |

| Ethnic groups (2022[4]) |

|

| Religion (2020)[5] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Ecuadorian |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

| Daniel Noboa | |

| Verónica Abad Rojas | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence | |

• Declared | 10 August 1809 |

• from Spain | 24 May 1822 |

• from Gran Colombia | 13 May 1830 |

• Recognized by Spain | 16 February 1840[6] |

| 5 June 1895 | |

| 28 September 2008 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 283,561 km2 (109,484 sq mi)[7] (73rd) |

• Excluding the Galapagos Islands | 256,370 km2 (98,990 sq mi)[8][9] |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 17,483,326[10] |

• 2022 census | 16,938,986[11] (73rd) |

• Density | 69/km2 (178.7/sq mi) (148th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2022) | medium |

| HDI (2022) | high (83rd) |

| Currency | United States dollara (USD) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 / −6 (ECT / GALT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +593 |

| ISO 3166 code | EC |

| Internet TLD | .ec |

| |

Эквадор , [а] официально Республика Эквадор , [б] — страна на северо-западе Южной Америки , граничащая с Колумбией на севере, Перу на востоке и юге и с Тихим океаном на западе. Эквадор также включает Галапагосские острова в Тихом океане, примерно в 1000 километрах (621 миль) к западу от материка. страны Столица — Кито , а крупнейший город — Гуаякиль . [ противоречивый ]

Территории современного Эквадора когда-то были домом для множества коренных народов , которые постепенно были включены в состав Империи инков в 15 веке. Эта территория была колонизирована Испанской империей в 16 веке, получив независимость в 1820 году как часть Великой Колумбии , из которой она стала суверенным государством в 1830 году. Наследие обеих империй отражено в этнически разнообразном населении Эквадора, большая часть которого 17,8 миллиона человек являются метисами , за ними следуют значительные меньшинства европейцев , коренных американцев , африканцев и азиатов . Испанский является официальным языком, на котором говорит большинство населения, хотя также признаются 13 родных языков, включая кечуа и шуар .

Ecuador is a representative democratic presidential republic and a developing country[19] whose economy is highly dependent on exports of commodities, primarily petroleum and agricultural products. The country is a founding member of the United Nations, Organization of American States, Mercosur, PROSUR, and the Non-Aligned Movement. According to the Center for Economic and Policy Research, between 2006 and 2016, poverty decreased from 36.7% to 22.5% and annual per capita GDP growth was 1.5 percent (as compared to 0.6 percent over the prior two decades). At the same time, the country's Gini index of economic inequality improved from 0.55 to 0.47.[20]

One of 17 megadiverse countries in the world,[21][22] Ecuador hosts many endemic plants and animals, such as those of the Galápagos Islands. In recognition of its unique ecological heritage, the new constitution of 2008 is the first in the world to recognize legally enforceable rights of nature.[23]

Etymology[edit]

The country's name means "Equator" in Spanish, truncated from the Spanish official name, República del Ecuador (lit. "Republic of the Equator"), derived from the former Ecuador Department of Gran Colombia established in 1824 as a division of the former territory of the Royal Audience of Quito. Quito, which remained the capital of the department and republic, is located only about 40 kilometers (25 mi), 1⁄4 of a degree, south of the equator.

History[edit]

Pre-Inca era[edit]

Various peoples had settled in the area of future Ecuador before the arrival of the Incas. The archeological evidence suggests that the Paleo-Indians' first dispersal into the Americas occurred near the end of the last glacial period, around 16,500–13,000 years ago. The first people who reached Ecuador may have journeyed by land from North and Central America or by boat down the Pacific Ocean coastline.

Even though their languages were unrelated, these groups developed similar groups of cultures, each based in different environments. The people of the coast combined agriculture with fishing, hunting, and gathering; the people of the highland Andes developed a sedentary agricultural way of life; and peoples of the Amazon basin relied on hunting and gathering, in some cases combined with agriculture and arboriculture.

Many civilizations[25] arose in Ecuador, such as the Valdivia Culture and Machalilla Culture on the coast,[26][27] the Quitus (near present-day Quito),[28] and the Cañari (near present-day Cuenca).[29]

In the highland Andes mountains, where life was more sedentary, groups of tribes cooperated and formed villages; thus the first nations based on agricultural resources and the domestication of animals formed. Eventually, through wars and marriage alliances of their leaders, groups of nations formed confederations.

When the Incas arrived, they found that these confederations were so developed that it took the Incas two generations of rulers—Topa Inca Yupanqui and Huayna Capac—to absorb them into the Inca Empire. People belonging to the confederations that gave them the most problems were deported to distant areas of Peru, Bolivia, and north Argentina. Similarly, a number of loyal Inca subjects from Peru and Bolivia were brought to Ecuador to prevent rebellion. Thus, the region of highland Ecuador became part of the Inca Empire in 1463 sharing the same language.[30]

In contrast, when the Incas made incursions into coastal Ecuador and the eastern Amazon jungles of Ecuador, they found both the environment and indigenous people more hostile. Moreover, when the Incas tried to subdue them, these indigenous people withdrew to the interior and resorted to guerrilla tactics. As a result, Inca expansion into the Amazon Basin and the Pacific coast of Ecuador was hampered. The indigenous people of the Amazon jungle and coastal Ecuador remained relatively autonomous until the Spanish soldiers and missionaries arrived in force. The Amazonian people and the Cayapas of Coastal Ecuador were the only groups to resist both Inca and Spanish domination, maintaining their languages and cultures well into the 21st century.[31]

Before the arrival of the Spaniards, the Inca Empire was involved in a civil war. The untimely death of both the heir Ninan Cuyochi and the Emperor Huayna Capac, from a European disease that spread into Ecuador, created a power vacuum between two factions and led to a civil war.[32] The army stationed north[33][34] headed by Atahualpa marched south to Cuzco and massacred the royal family associated with his brother. In 1532, a small band of Spaniards headed by Francisco Pizarro reached Cajamarca and lured Atahualpa into a trap (battle of Cajamarca). Pizarro promised to release Atahualpa if he made good his promise of filling a room full of gold. But, after a mock trial, the Spaniards executed Atahualpa by strangulation.[35]

Spanish colonization[edit]

New infectious diseases such as smallpox, endemic to the Europeans, caused high fatalities among the Amerindian population during the first decades of Spanish rule, as they had no immunity. At the same time, the natives were forced into the encomienda labor system for the Spanish. In 1563, Quito became the seat of a real audiencia (administrative district) of Spain and part of the Viceroyalty of Peru and later the Viceroyalty of New Granada.

The 1797 Riobamba earthquake, which caused up to 40,000 casualties, was studied by Alexander von Humboldt, when he visited the area in 1801–1802.[36]

After nearly 300 years of Spanish rule, Quito still remained small with a population of 10,000 people. On 10 August 1809, the city's criollos called for independence from Spain (first among the peoples of Latin America). They were led by Juan Pío Montúfar, Quiroga, Salinas, and Bishop Cuero y Caicedo. Quito's nickname, "Luz de América" ("Light of America"), is based on its leading role in trying to secure an independent, local government. Although the new government lasted no more than two months, it had important repercussions and was an inspiration for the independence movement of the rest of Spanish America. Today, 10 August is celebrated as Independence Day, a national holiday.[37]

Independence[edit]

On 9 October 1820, the Department of Guayaquil became the first territory in Ecuador to gain its independence from Spain, and it spawned most of the Ecuadorian coastal provinces, establishing itself as an independent state. Its inhabitants celebrated what is now Ecuador's official Independence Day on 24 May 1822. The rest of Ecuador gained its independence after Antonio José de Sucre defeated the Spanish Royalist forces at the Battle of Pichincha, near Quito. Following the battle, Ecuador joined Simón Bolívar's Republic of Gran Colombia, also including modern-day Colombia, Venezuela, and Panama. In 1830, Ecuador separated from Gran Colombia and became an independent republic. Two years later, it annexed the Galapagos Islands.[38]

The 19th century was marked by instability for Ecuador with a rapid succession of rulers. The first president of Ecuador was the Venezuelan-born Juan José Flores, who was ultimately deposed. Leaders who followed him included Vicente Rocafuerte; José Joaquín de Olmedo; José María Urbina; Diego Noboa; Pedro José de Arteta; Manuel de Ascásubi; and Flores's own son, Antonio Flores Jijón, among others. The conservative Gabriel García Moreno unified the country in the 1860s with the support of the Roman Catholic Church. In the late 19th century, world demand for cocoa tied the economy to commodity exports and led to migrations from the highlands to the agricultural frontier on the coast.

Ecuador abolished slavery in 1851.[39] The descendants of enslaved Ecuadorians are among today's Afro-Ecuadorian population.

Liberal Revolution[edit]

The Liberal Revolution of 1895 under Eloy Alfaro reduced the power of the clergy and the conservative land owners. This liberal wing retained power until the military "Julian Revolution" of 1925. The 1930s and 1940s were marked by instability and emergence of populist politicians, such as five-time President José María Velasco Ibarra.

Loss of claimed territories since 1830[edit]

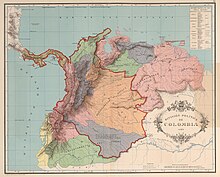

After Ecuador's separation from Colombia on 13 May 1830, its first President, General Juan José Flores, laid claim to the territory that had belonged to the Real Audiencia of Quito, also referred to as the Presidencia of Quito. He supported his claims with Spanish Royal decrees, or real cedulas, that delineated the borders of Spain's former overseas colonies. In the case of Ecuador, Flores based Ecuador's de jure claims on the Real Cedulas of 1563, 1739, and 1740; with modifications in the Amazon Basin and Andes Mountains that were introduced through the Treaty of Guayaquil (1829) which Peru reluctantly signed, after the overwhelmingly outnumbered Gran Colombian force led by Antonio José de Sucre defeated President and General La Mar's Peruvian invasion force in the Battle of Tarqui. In addition, Ecuador's eastern border with the Portuguese colony of Brazil in the Amazon Basin was modified before the Wars of Independence by the First Treaty of San Ildefonso (1777) between the Spanish Empire and the Portuguese Empire. Moreover, to add legitimacy to his claims, on 16 February 1840, Flores signed a treaty with Spain, whereby Flores convinced Spain to officially recognize Ecuadorian independence and its sole rights to colonial titles over Spain's former colonial territory known anciently to Spain as the Kingdom and Presidency of Quito.

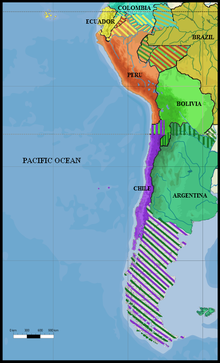

Ecuador during its long and turbulent history has lost most of its contested territories to each of its more powerful neighbors, such as Colombia in 1832 and 1916, Brazil in 1904 through a series of peaceful treaties, and Peru after a short war in which the Protocol of Rio de Janeiro was signed in 1942.

Struggle for independence[edit]

During the struggle for independence, before Peru or Ecuador became independent, areas of the former Vice Royalty of New Granada declared themselves independent from Spain. A few months later, a part of the Peruvian liberation army of San Martín decided to occupy the independent cities of Tumbez and Jaén, with the intention of using them as springboards to occupy the independent city of Guayaquil and then liberate the rest of the Audiencia de Quito (Ecuador). It was common knowledge among officers of the liberation army from the south that their leader San Martín wished to liberate present-day Ecuador and add it to the future republic of Peru, since it had been part of the Inca Empire before the Spaniards conquered it. However, Bolívar's intention was to form a new republic known as the Gran Colombia, out of the liberated Spanish territory of New Granada which consisted of Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador. San Martín's plans were thwarted when Bolívar, descended from the Andes mountains and occupied Guayaquil; they also annexed the newly liberated Audiencia de Quito to the Republic of Gran Colombia.

In the south, Ecuador had claims to a small piece of land beside the Pacific Ocean known as Tumbes. In Ecuador's southern Andes Mountain region where the Marañon cuts across, Ecuador had claims to an area it called Jaén de Bracamoros. These areas were included as part of the territory of Gran Colombia by Bolivar on 17 December 1819, during the Congress of Angostura when the Republic of Gran Colombia was created. Tumbes declared itself independent from Spain on 17 January 1821, and Jaén de Bracamoros on 17 June 1821, without any outside help from revolutionary armies. However, that same year, Peruvian forces participating in the Trujillo revolution occupied both Jaén and Tumbes. Peruvian generals, without any legal titles backing them up and with Ecuador still federated with the Gran Colombia, had the desire to annex Ecuador to the Republic of Peru at the expense of the Gran Colombia, feeling that Ecuador was once part of the Inca Empire.

On 28 July 1821, Peruvian independence was proclaimed in Lima by San Martín, and Tumbes and Jaén, which were included as part of the revolution of Trujillo by the Peruvian occupying force, had the whole region swear allegiance to the new Peruvian flag and incorporated itself into Peru. Gran Colombia had always protested Peru for the return of Jaén and Tumbes for almost a decade, then finally Bolivar after long and futile discussion over the return of Jaén, Tumbes, and part of Mainas, declared war. President and General José de La Mar, who was born in Ecuador, believing his opportunity had come to annex the District of Ecuador to Peru, personally, with a Peruvian force, invaded and occupied Guayaquil and a few cities in the Loja region of southern Ecuador on 28 November 1828.

The war ended when an outnumbered southern Gran Colombian army at Battle of Tarqui on 27 February 1829, led by Antonio José de Sucre, defeated the Peruvian invasion force led by President La Mar. This defeat led to the signing of the Treaty of Guayaquil in September 1829, whereby Peru and its Congress recognized Gran Colombian rights over Tumbes, Jaén, and Maynas. Through meetings between Peru and Gran Colombia, the border was set as Tumbes river in the west, and in the east, the Maranon and Amazon rivers were to be followed toward Brazil as the most natural borders between them. According to the peace negotiations Peru agreed to return Guayaquil, Tumbez, and Jaén; despite this, Peru returned Guayaquil, but failed to return Tumbes and Jaén, alleging that it was not obligated to follow the agreements, since the Gran Colombia ceased to exist when it divided itself into three different nations – Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela.

The Central District of the Gran Colombia, known as Cundinamarca or New Granada (modern Colombia) with its capital in Bogota, did not recognize the separation of the Southern District of the Gran Colombia, with its capital in Quito, from the Gran Colombian federation on 13 May 1830. After Ecuador's separation, the Department of Cauca voluntarily decided to unite itself with Ecuador due to instability in the central government of Bogota. The Venezuelan born President of Ecuador, the general Juan José Flores, with the approval of the Ecuadorian congress annexed the Department of Cauca on 20 December 1830, since the government of Cauca had called for union with the District of the South as far back as April 1830. Moreover, the Cauca region, throughout its long history, had very strong economic and cultural ties with the people of Ecuador. Also, the Cauca region, which included such cities as Pasto, Popayán, and Buenaventura, had always been dependent on the Presidencia or Audiencia of Quito.

Fruitless negotiations continued between the governments of Bogotá and Quito, where the government of Bogotá did not recognize the separation of Ecuador or that of Cauca from the Gran Colombia until war broke out in May 1832. In five months, New Granada defeated Ecuador due to the fact that the majority of the Ecuadorian Armed Forces were composed of rebellious angry unpaid veterans from Venezuela and Colombia that did not want to fight against their fellow countrymen. Seeing that his officers were rebelling, mutinying, and changing sides, President Flores had no option but to reluctantly make peace with New Granada. The Treaty of Pasto of 1832 was signed by which the Department of Cauca was turned over to New Granada (modern Colombia), the government of Bogotá recognized Ecuador as an independent country and the border was to follow the Ley de División Territorial de la República de Colombia (Law of the Division of Territory of the Gran Colombia) passed on 25 June 1824. This law set the border at the river Carchi and the eastern border that stretched to Brazil at the Caquetá river. Later, Ecuador contended that the Republic of Colombia, while reorganizing its government, unlawfully made its eastern border provisional and that Colombia extended its claims south to the Napo River because it said that the Government of Popayán extended its control all the way to the Napo River.

Struggle for possession of the Amazon Basin[edit]

When Ecuador seceded from the Gran Colombia, Peru contested Ecuador's claims with the newly discovered Real Cedula of 1802, by which Peru claims the King of Spain had transferred these lands from the Viceroyalty of New Granada to the Viceroyalty of Peru. During colonial times this was to halt the ever-expanding Portuguese settlements into Spanish domains, which were left vacant and in disorder after the expulsion of Jesuit missionaries from their bases along the Amazon Basin. Ecuador countered by labeling the Cedula of 1802 an ecclesiastical instrument, which had nothing to do with political borders. Peru began its de facto occupation of disputed Amazonian territories, after it signed a secret 1851 peace treaty in favor of Brazil. This treaty disregarded Spanish rights that were confirmed during colonial times by a Spanish-Portuguese treaty over the Amazon regarding territories held by illegal Portuguese settlers.

Peru began occupying the missionary villages in the Mainas or Maynas region, which it began calling Loreto, with its capital in Iquitos. During its negotiations with Brazil, Peru claimed Amazonian Basin territories up to Caqueta River in the north and toward the Andes Mountain range. Colombia protested stating that its claims extended south toward the Napo and Amazon Rivers. Ecuador protested that it claimed the Amazon Basin between the Caqueta river and the Marañon-Amazon river. Peru ignored these protests and created the Department of Loreto in 1853 with its capital in Iquitos. Peru briefly occupied Guayaquil again in 1860, since Peru thought that Ecuador was selling some of the disputed land for development to British bond holders, but returned Guayaquil after a few months. The border dispute was then submitted to Spain for arbitration from 1880 to 1910, but to no avail.[40]

In the early part of the 20th century, Ecuador made an effort to peacefully define its eastern Amazonian borders with its neighbours through negotiation. On 6 May 1904, Ecuador signed the Tobar-Rio Branco Treaty recognizing Brazil's claims to the Amazon in recognition of Ecuador's claim to be an Amazonian country to counter Peru's earlier Treaty with Brazil back on 23 October 1851. Then after a few meetings with the Colombian government's representatives an agreement was reached and the Muñoz Vernaza-Suarez Treaty was signed 15 July 1916, in which Colombian rights to the Putumayo river were recognized as well as Ecuador's rights to the Napo river and the new border was a line that ran midpoint between those two rivers. In this way, Ecuador gave up the claims it had to the Amazonian territories between the Caquetá River and Napo River to Colombia, thus cutting itself off from Brazil. Later, a brief war erupted between Colombia and Peru, over Peru's claims to the Caquetá region, which ended with Peru reluctantly signing the Salomon-Lozano Treaty on 24 March 1922. Ecuador protested this secret treaty, since Colombia gave away Ecuadorian claimed land to Peru that Ecuador had given to Colombia in 1916.

On 21 July 1924, the Ponce-Castro Oyanguren Protocol was signed between Ecuador and Peru where both agreed to hold direct negotiations and to resolve the dispute in an equitable manner and to submit the differing points of the dispute to the United States for arbitration. Negotiations between the Ecuadorian and Peruvian representatives began in Washington on 30 September 1935. The negotiations turned into arguments during the next 7 months and finally on 29 September 1937, the Peruvian representatives decided to break off the negotiations.[citation needed]

In 1941, amid fast-growing tensions within disputed territories around the Zarumilla River, war broke out with Peru. Peru claimed that Ecuador's military presence in Peruvian-claimed territory was an invasion; Ecuador, for its part, claimed that Peru had recently invaded Ecuador around the Zarumilla River and that Peru since Ecuador's independence from Spain has systematically occupied Tumbez, Jaén, and most of the disputed territories in the Amazonian Basin between the Putomayo and Marañon Rivers. In July 1941, troops were mobilized in both countries. Peru had an army of 11,681 troops who faced a poorly supplied and inadequately armed Ecuadorian force of 2,300, of which only 1,300 were deployed in the southern provinces. Hostilities erupted on 5 July 1941, when Peruvian forces crossed the Zarumilla river at several locations, testing the strength and resolve of the Ecuadorian border troops. Finally, on 23 July 1941, the Peruvians launched a major invasion, crossing the Zarumilla river in force and advancing into the Ecuadorian province of El Oro.

During the course of the Ecuadorian–Peruvian War, Peru gained control over part of the disputed territory and some parts of the province of El Oro, and some parts of the province of Loja, demanding that the Ecuadorian government give up its territorial claims. The Peruvian Navy blocked the port of Guayaquil, almost cutting all supplies to the Ecuadorian troops. After a few weeks of war and under pressure by the United States and several Latin American nations, all fighting came to a stop. Ecuador and Peru came to an accord formalized in the Rio Protocol, signed on 29 January 1942, in favor of hemispheric unity against the Axis Powers in World War II favoring Peru with the territory they occupied at the time the war came to an end.

The 1944 Glorious May Revolution followed a military-civilian rebellion and a subsequent civic strike which successfully removed Carlos Arroyo del Río as a dictator from Ecuador's government. However, a post-Second World War recession and popular unrest led to a return to populist politics and domestic military interventions in the 1960s, while foreign companies developed oil resources in the Ecuadorian Amazon. In 1972, construction of the Andean pipeline was completed. The pipeline brought oil from the east side of the Andes to the coast, making Ecuador South America's second largest oil exporter.

In 1978, the city of Quito and the Galápagos Islands were inscribed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, making the first two properties in the world to become listed sites.

The Rio Protocol failed to precisely resolve the border along a little river in the remote Cordillera del Cóndor region in southern Ecuador. This caused a long-simmering dispute between Ecuador and Peru, which ultimately led to fighting between the two countries; first a border skirmish in January–February 1981 known as the Paquisha Incident, and ultimately full-scale warfare in January 1995 where the Ecuadorian military shot down Peruvian aircraft and helicopters and Peruvian infantry marched into southern Ecuador. Each country blamed the other for the onset of hostilities, known as the Cenepa War. Sixto Durán Ballén, the Ecuadorian president, famously declared that he would not give up a single centimeter of Ecuador. Popular sentiment in Ecuador became strongly nationalistic against Peru: graffiti could be seen on the walls of Quito referring to Peru as the "Cain de Latinoamérica", a reference to the murder of Abel by his brother Cain in the Book of Genesis.[41]

Ecuador and Peru signed the Brasilia Presidential Act peace agreement on 26 October 1998, which ended hostilities, and effectively put an end to the Western Hemisphere's longest running territorial dispute.[42] The Guarantors of the Rio Protocol (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and the United States of America) ruled that the border of the undelineated zone was to be set at the line of the Cordillera del Cóndor. While Ecuador had to give up its decades-old territorial claims to the eastern slopes of the Cordillera, as well as to the entire western area of Cenepa headwaters, Peru was compelled to give to Ecuador, in perpetual lease but without sovereignty, 1 km2 (0.39 sq mi) of its territory, in the area where the Ecuadorian base of Tiwinza – focal point of the war – had been located within Peruvian soil and which the Ecuadorian Army held during the conflict. The final border demarcation came into effect on 13 May 1999, and the multi-national MOMEP (Military Observer Mission for Ecuador and Peru) troop deployment withdrew on 17 June 1999.[42]

Military governments (1972–79)[edit]

In 1972, a "revolutionary and nationalist" military junta overthrew the government of Velasco Ibarra. The coup d'état was led by General Guillermo Rodríguez and executed by navy commander Jorge Queirolo G. The new president exiled José María Velasco to Argentina. He remained in power until 1976, when he was removed by another military government. That military junta was led by Admiral Alfredo Poveda, who was declared chairman of the Supreme Council. The Supreme Council included two other members: General Guillermo Durán Arcentales and General Luis Pintado. The civil society more and more insistently called for democratic elections. Colonel Richelieu Levoyer, Government Minister, proposed and implemented a Plan to return to the constitutional system through universal elections. This plan enabled the new democratically elected president to assume the duties of the executive office.

Return to democracy (1979–present)[edit]

Elections were held on 29 April 1979, under a new constitution. Jaime Roldós Aguilera was elected president, garnering over one million votes, the most in Ecuadorian history. He took office on 10 August as the first constitutionally elected president, after nearly a decade of civilian and military dictatorships. In 1980, he founded the Partido Pueblo, Cambio y Democracia (People, Change, and Democracy Party) after withdrawing from the Concentración de Fuerzas Populares (Popular Forces Concentration). He governed until 24 May 1981, when he died, along with his wife and the minister of defense Marco Subia Martinez, when his Air Force plane crashed in heavy rain near the Peruvian border. Many people believe that he was assassinated by the CIA,[43] given the multiple death threats against him because of his reformist agenda, the deaths in automobile crashes of two key witnesses before they could testify during the investigation, and the sometimes contradictory accounts of the incident. Roldos was immediately succeeded by Vice President Osvaldo Hurtado.

In 1984 León Febres Cordero from the Social Christian Party was elected president. Rodrigo Borja Cevallos of the Democratic Left (Izquierda Democrática, or ID) party won the presidency in 1988, winning the runoff election against Abdalá Bucaram (brother in law of Jaime Roldos and founder of the Ecuadorian Roldosist Party). His government was committed to improving human rights protection and carried out some reforms, notably an opening of Ecuador to foreign trade. The Borja government negotiated the disbanding of the small terrorist group, "¡Alfaro Vive, Carajo!" ("Alfaro Lives, Dammit!"), named after Eloy Alfaro. However, continuing economic problems undermined the popularity of the ID party, and opposition parties gained control of Congress in 1999.

A notable event was the Cenepa War fought between Ecuador and Peru in 1995.

Ecuador adopted the United States dollar on 13 April 2000 as its national currency and on 11 September, the country eliminated the Ecuadorian sucre, in order to stabilize the country's economy.[44] The US Dollar has been the only official currency of Ecuador since then.[45]

The emergence of the Amerindian population as an active constituency has added to the democratic volatility of the country in recent years. The population has been motivated by government failures to deliver on promises of land reform, lower unemployment and provision of social services, and the historical exploitation by the land-holding elite. Their movement, along with the continuing destabilizing efforts by both the elite and leftist movements, has led to a deterioration of the executive office. The populace and the other branches of government give the president very little political capital, as illustrated by the most recent removal of President Lucio Gutiérrez from office by Congress in April 2005.[46] Vice President Alfredo Palacio took his place[47]

In the election of 2006, Rafael Correa gained the presidency.[48] In January 2007, several left-wing political leaders of Latin America, his future allies, attended his swearing-in ceremony.[49] Endorsed in a 2008 referendum, a new constitution implemented leftist reforms.[50] In December 2008, Correa declared Ecuador's national debt illegitimate, based on the argument that it was odious debt contracted by prior corrupt and despotic regimes. He announced that the country would default on over $3 billion worth of bonds, and he succeeded in reducing the price of outstanding bonds by more than 60% by fighting creditors in international courts.[51] He brought Ecuador into the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas in June 2009. Correa's administration reduced the high levels of poverty and unemployment in Ecuador.[52][53][54][55][56]

Correa's three consecutive terms (from 2007 to 2017) were followed by his former Vice President Lenín Moreno's four years as president (2017–21). After being elected in 2017, President Moreno's government adopted economically liberal policies, such as reduction of public spending, trade liberalization, and flexibility of the labour code. Ecuador also left the left-wing Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (Alba) in August 2018.[57] The Productive Development Act introduced an austerity policy, and reduced the previous development and redistribution policies. Regarding taxes, the authorities aimed to "encourage the return of investors" by granting amnesty to fraudsters and proposing measures to reduce tax rates for large companies. In addition, the government waived the right to tax increases in raw material prices and foreign exchange repatriations.[58] In October 2018, Moreno cut diplomatic relations with the Maduro administration of Venezuela, a close ally of Correa.[59] The relations with the United States improved significantly under Moreno. In June 2019, Ecuador agreed to allow US military planes to operate from an airport on the Galapagos Islands.[60] In February 2020, his visit to Washington was the first meeting between an Ecuadorian and U.S. president in 17 years.[61]

A series of protests began on 3 October 2019 against the end of fuel subsidies and austerity measures adopted by Moreno. On 10 October, protesters overran Quito, the capital, causing the Government of Ecuador to relocate temporarily to Guayaquil.[62] The government eventually returned to Quito in 2019.[63] On 14 October 2019, the government restored fuel subsidies and withdrew an austerity package, which ended nearly two weeks of protests.[64]

In the 11 April 2021 election, conservative former banker Guillermo Lasso took 52.4% of the vote, compared to 47.6% for left-wing economist Andrés Aráuz, who was supported by exiled former president Correa. Lasso had finished second in the 2013 and 2017 presidential elections.[65] On 24 May 2021, Lasso was sworn in, becoming the country's first right-wing leader in 14 years.[66] Lasso's party CREO Movement, and its ally the Social Christian Party (PSC) won only 31 parliamentary seats out of 137, while Aráuz's Union for Hope (UNES) won 49 seats, which meant Lasso needed support from the Izquierda Democrática and the indigenist Pachakutik parties to push through his legislative agenda.[67]

In October 2021, Lasso declared a 60-day state of emergency to combat crime and drug-related violence,[68] including the numerous bloody clashes between rival groups in the state prisons.[69] Lasso proposed a series of constitutional changes to enhance his government's ability to respond to crime. In a referendum in February 2023, voters overwhelmingly rejected his proposed changes, which weakened Lasso's political standing.[70]

On 15 October 2023, centrist candidate Daniel Noboa won the premature presidential election with 52.3% of the vote against leftist candidate Luisa González.[71] On 23 November 2023, Noboa was sworn in.[72]

In January 2024, Noboa declared an "internal armed conflict" against organised crime, in response to the escape of imprisoned leader of the Los Choneros cartel, José Adolfo Macías Villamar (also known as "Fito"), and an armed attack at a public television channel.[73][74]

Government and politics[edit]

The Ecuadorian State consists of five branches of government: the Executive Branch, the Legislative Branch, the Judicial Branch, the Electoral Branch, and Transparency and Social Control.

Ecuador is governed by a democratically elected president for a four-year term. The president of Ecuador exercises his power from the presidential Palacio de Carondelet in Quito. The current constitution was written by the Ecuadorian Constituent Assembly elected in 2007, and was approved by referendum in 2008. Since 1936, voting is compulsory for all literate persons aged 18–65, optional for all other citizens over the age of 16.[75][76]

The executive branch includes 23 ministries. Provincial governors and councilors (mayors, aldermen, and parish boards) are directly elected. The National Assembly of Ecuador meets throughout the year except for recesses in July and December. There are thirteen permanent committees. Members of the National Court of Justice are appointed by the National Judicial Council for nine-year terms.

Executive branch[edit]

The executive branch is led by the president. The president is accompanied by the vice-president, elected for four years (with the ability to be re-elected only once). As head of state and chief government official, he is responsible for public administration including the appointing of national coordinators, ministers, ministers of State and public servants. The executive branch defines foreign policy, appoints the Chancellor of the Republic, as well as ambassadors and consuls, being the ultimate authority over the Armed Forces of Ecuador, National Police of Ecuador, and appointing authorities. The acting president's wife receives the title of First Lady of Ecuador.

Legislative branch[edit]

The legislative branch is embodied by the National Assembly, which is headquartered in the city of Quito in the Legislative Palace, and consists of 137 assemblymen, divided into ten committees and elected for a four-year term. Fifteen national constituency elected assembly, two Assembly members elected from each province and one for every 100,000 inhabitants or fraction exceeding 150,000, according to the latest national population census. In addition, statute determines the election of assembly of regions and metropolitan districts.

Judicial branch[edit]

Ecuador's judiciary has as its main body the Judicial Council, and also includes the National Court of Justice, provincial courts, and lower courts. Legal representation is made by the Judicial Council.The National Court of Justice is composed of 21 judges elected for a term of nine years. Judges are renewed by thirds every three years pursuant to the Judicial Code. These are elected by the Judicial Council on the basis of opposition proceedings and merits.The justice system is buttressed by the independent offices of public prosecutor and the public defender. Auxiliary organs are as follows: notaries, court auctioneers, and court receivers. Also there is a special legal regime for Amerindians.

Electoral branch[edit]

The electoral system functions by authorities which enter only every four years or when elections or referendums occur. Its main functions are to organize, control elections, and punish the infringement of electoral rules. Its main body is the National Electoral Council, which is based in the city of Quito, and consists of seven members of the political parties most voted, enjoying complete financial and administrative autonomy. This body, along with the electoral court, forms the Electoral Branch which is one of Ecuador's five branches of government.

Transparency and social control branch[edit]

The Transparency and Social Control consists of the Council for Citizen Participation and Social Control, an ombudsman, the Comptroller General of the State, and the superintendents. Branch members hold office for five years. This branch is responsible for promoting transparency and control plans publicly, as well as plans to design mechanisms to combat corruption, as also designate certain authorities, and be the regulatory mechanism of accountability in the country.

Foreign affairs[edit]

Ecuador joined the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1973 and suspended its membership in 1992. Under President Rafael Correa, the country returned to OPEC before leaving again in 2020 under the instruction of President Moreno, citing its desire to increase crude oil exportation to gain more revenue.[77][78]

Ecuador has maintained a research station in Antarctica for peaceful scientific study as a member nation of the Antarctica Treaty. Ecuador has often placed great emphasis on multilateral approaches to international issues. Ecuador is a member of the United Nations (and most of its specialized agencies) and a member of many regional groups, including the Rio Group, the Latin American Economic System, the Latin American Energy Organization, the Latin American Integration Association, the Andean Community of Nations, and the Bank of the South (Spanish: Banco del Sur or BancoSur).

In 2017, the Ecuadorian parliament adopted a law on human mobility.[79]

The International Organization for Migration lauded Ecuador as the first state to have established the promotion of the concept of universal citizenship in its constitution, aiming to promote the universal recognition and protection of the human rights of migrants.[80] In March 2019, Ecuador withdrew from the Union of South American Nations.[81]

Human rights[edit]

A 2003 Amnesty International report was critical that there were scarce few prosecutions for human rights violations committed by security forces, and those only in police courts, which are not considered impartial or independent. There are allegations that the security forces routinely torture prisoners. There are reports of prisoners having died while in police custody. Sometimes the legal process can be delayed until the suspect can be released after the time limit for detention without trial is exceeded. Prisons are overcrowded and conditions in detention centers are "abominable".[82]

UN's Human Rights Council's (HRC) Universal Periodic Review (UPR) has treated the restrictions on freedom of expression and efforts to control NGOs and recommended that Ecuador should stop the criminal sanctions for the expression of opinions, and delay in implementing judicial reforms. Ecuador rejected the recommendation on decriminalization of libel.[83]

According to Human Rights Watch (HRW) former president Correa intimidated journalists and subjected them to "public denunciation and retaliatory litigation". The sentences to journalists were years of imprisonment and millions of dollars of compensation, even though defendants had been pardoned.[83] Correa stated he was only seeking a retraction for slanderous statements.[84]

According to HRW, Correa's government weakened the freedom of press and independence of the judicial system. In Ecuador's current judicial system, judges are selected in a contest of merits, rather than government appointments. However, the process of selection has been criticized as biased and subjective. In particular, the final interview is said to be given "excessive weighing". Judges and prosecutors that made decisions in favor of Correa in his lawsuits had received permanent posts, while others with better assessment grades had been rejected.[83][85]

The laws also forbid articles and media messages that could favor or disfavor some political message or candidate. In the first half of 2012, twenty private TV or radio stations were closed down.[83] People engaging in public protests against environmental and other issues are prosecuted for "terrorism and sabotage", which may lead to an eight-year prison sentence.[83]

According to Freedom House, restrictions on the media and civil society have decreased since 2017.[86] In October 2022, the United Nations expressed concerns about the dire situation in various detention centers and prisons, and the human rights of those deprived of liberty in Ecuador.[87]

Administrative divisions[edit]

Ecuador is divided into 24 provinces (Spanish: provincias), each with its own administrative capital:

Regions and planning areas[edit]

Regionalization, or zoning, is the union of two or more adjoining provinces in order to decentralize the administrative functions of the capital, Quito.In Ecuador, there are seven regions, or zones, each shaped by the following provinces:

- Region 1 (42,126 km2, or 16,265 mi2): Esmeraldas, Carchi, Imbabura, and Sucumbios. Administrative city: Ibarra

- Region 2 (43,498 km2, or 16,795 mi2): Pichincha, Napo, and Orellana. Administrative city: Tena

- Region 3 (44,710 km2, or 17,263 mi2): Chimborazo, Tungurahua, Pastaza, and Cotopaxi. Administrative city: Riobamba

- Region 4 (22,257 km2, or 8,594 mi2): Manabí and Santo Domingo de los Tsachilas. Administrative city: Ciudad Alfaro

- Region 5 (38,420 km2, or 14,834 mi2): Santa Elena, Guayas, Los Ríos, Galápagos, and Bolívar. Administrative city: Milagro

- Region 6 (38,237 km2, or 14,763 mi2): Cañar, Azuay, and Morona Santiago. Administrative city: Cuenca

- Region 7 (27,571 km2, or 10,645 mi2): El Oro, Loja, and Zamora Chinchipe. Administrative city: Loja

Quito and Guayaquil are Metropolitan Districts. Galápagos, despite being included within Region 5,[88] is also under a special unit.[89]

Military[edit]

The Ecuadorian Armed Forces (Fuerzas Armadas de la Republica de Ecuador), consists of the Army, Air Force, and Navy and have the stated responsibility for the preservation of the integrity and national sovereignty of the national territory.

Due to the continuous border disputes with Peru, finally settled in the early 2000s, and due to the ongoing problem with the Colombian guerrilla insurgency infiltrating Amazonian provinces, the Ecuadorian Armed Forces has gone through a series of changes. In 2009, the new administration at the Defense Ministry launched a deep restructuring within the forces, increasing spending budget to $1,691,776,803, an increase of 25%.[90]

The Military Academy General Eloy Alfaro (c. 1838) located in Quito is in charge of graduating army officers.[91] The Ecuadorian Navy Academy (c. 1837), located in Salinas graduates navy officers.[92] The Air Academy "Cosme Rennella (c. 1920), also located in Salinas, graduates air force officers.[93]

Geography[edit]

According to the CIA, Ecuador has a total area of 283,571 km2 (109,487 sq mi), including the Galápagos Islands. Of this, 276,841 km2 (106,889 sq mi) is land and 6,720 km2 (2,595 sq mi) water.[2] The total area, according to the Ecuadorian government's foreign ministry, is 256,370 km2 (98,985 sq mi).[94] The Galápagos Islands are sometimes considered part of Oceania,[95][96][97][98][99][100][101] which would thus make Ecuador a transcontinental country under certain definitions. Ecuador is bigger than Uruguay, Suriname, Guyana and French Guiana in South America.

Ecuador lies between latitudes 2°N and 5°S,bounded on the west by the Pacific Ocean, and has 2,337 km (1,452 mi) of coastline. It has 2,010 km (1,250 mi) of land boundaries, with Colombia in the north (with a 590 km (367 mi) border) and Peru in the east and south (with a 1,420 km (882 mi) border). It is the westernmost country that lies on the equator.[102]

The country has four main geographic regions:

- La Costa, or "the coast": The coastal region consists of the provinces to the west of the Andean range – Esmeraldas, Guayas, Los Ríos, Manabí, El Oro, Santo Domingo de los Tsachilas and Santa Elena. It is the country's most fertile and productive land, and is the seat of the large banana exportation plantations of the companies Dole and Chiquita. This region is also where most of Ecuador's rice crop is grown. The truly coastal provinces have active fisheries. The largest coastal city is Guayaquil.

- La Sierra, or "the highlands": The sierra consists of the Andean and Interandean highland provinces – Azuay, Cañar, Carchi, Chimborazo, Imbabura, Loja, Pichincha, Bolívar, Cotopaxi and Tungurahua. This land contains most of Ecuador's volcanoes and all of its snow-capped peaks. Agriculture is focused on the traditional crops of potato, maize, and quinua and the population is predominantly Amerindian Kichua. The largest Sierran city is Quito.

- La Amazonía, also known as El Oriente, or "the east": The oriente consists of the Amazon jungle provinces – Morona Santiago, Napo, Orellana, Pastaza, Sucumbíos, and Zamora-Chinchipe. This region is primarily made up of the huge Amazon national parks and Amerindian untouchable zones, which are vast stretches of land set aside for the Amazon Amerindian tribes to continue living traditionally. It is also the area with the largest reserves of petroleum in Ecuador, and parts of the upper Amazon here have been extensively exploited by petroleum companies. The population is primarily mixed Amerindian Shuar, Huaorani and Kichua, although there are numerous tribes in the deep jungle which are little-contacted. The largest city in the Oriente Lago Agrio in Sucumbíos.

- La Región Insular is the region comprising the Galápagos Islands, some 1,000 kilometers (620 mi) west of the mainland in the Pacific Ocean.

Ecuador's capital and second largest city[contradictory] is Quito,[103] which is in the province of Pichincha in the Sierra region. It is the second-highest capital city with an elevation of 2,850 meters. Ecuador's largest city[contradictory] is Guayaquil,[104] in the Guayas Province. Cotopaxi, just south of Quito, is one of the world's highest active volcanoes. The top of Mount Chimborazo (6,268 m, or 20,560 ft, above sea level), Ecuador's tallest mountain, is the most distant point from the center of the Earth on the Earth's surface because of the ellipsoid shape of the planet.[2]The Andes is the watershed divisor between the Amazon watershed, which runs to the east, and the Pacific, including the north–south rivers Mataje, Santiago, Esmeraldas, Chone, Guayas, Jubones, and Puyango-Tumbes.

Climate[edit]

There is great variety in the climate, largely determined by altitude. It is mild year-round in the mountain valleys, with a humid subtropical climate in coastal areas and rainforest in lowlands. The Pacific coastal area has a tropical climate with a severe rainy season. The climate in the Andean highlands is temperate and relatively dry, and the Amazon basin on the eastern side of the mountains shares the climate of other rainforest zones.

Because of its location at the equator, Ecuador experiences little variation in daylight hours during the course of a year. Both sunrise and sunset occur each day at the two six o'clock hours.[2]

The country has seen its seven glaciers lose 54.4% of their surface in forty years. Research predicts their disappearance by 2100. The cause is climate change, which threatens both the fauna and flora and the population.[105]

Biodiversity[edit]

Ecuador is one of seventeen megadiverse countries in the world according to Conservation International,[21] and it has the most biodiversity per square kilometer of any nation.[106][107]

Ecuador has 1,600 bird species (15% of the world's known bird species) in the continental area and 38 more endemic in the Galápagos. In addition to more than 16,000 species of plants, the country has 106 endemic reptiles, 138 endemic amphibians, and 6,000 species of butterfly. The Galápagos Islands are well known as a region of distinct fauna, as the famous place of birth to Darwin's Theory of Evolution, and as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[108]

Ecuador has the first constitution to recognize the rights of nature.[109] The protection of the nation's biodiversity is an explicit national priority as stated in the National Plan of "Buen Vivir", or good living, Objective 4, "Guarantee the rights of nature", Policy 1: "Sustainably conserve and manage the natural heritage, including its land and marine biodiversity, which is considered a strategic sector".[106]

As of the writing of the plan in 2008, 19% of Ecuador's land area was in a protected area; however, the plan also states that 32% of the land must be protected in order to truly preserve the nation's biodiversity.[106] Current protected areas include 11 national parks, 10 wildlife refuges, 9 ecological reserves, and other areas.[110] A program begun in 2008, Sociobosque, is preserving another 2.3% of total land area (6,295 km2, or 629,500 ha) by paying private landowners or community landowners (such as Amerindian tribes) incentives to maintain their land as native ecosystems such as native forests or grasslands. Eligibility and subsidy rates for this program are determined based on the poverty in the region, the number of hectares that will be protected, and the type of ecosystem of the land to be protected, among other factors.[111] Ecuador had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.66/10, ranking it 35th globally out of 172 countries.[112]

Despite being on the UNESCO list, the Galápagos are endangered by a range of negative environmental effects, threatening the existence of this exotic ecosystem.[113] Additionally, oil exploitation of the Amazon rainforest has led to the release of billions of gallons of untreated wastes, gas, and crude oil into the environment,[114] contaminating ecosystems and causing detrimental health effects to Amerindian peoples.[115][116] One of the best known examples is the Texaco-Chevron case.[117] This American oil company operated in the Ecuadorian Amazon region between 1964 and 1992. During this period, Texaco drilled 339 wells in 15 petroleum fields and abandoned 627 toxic wastewater pits. It is now known that these highly polluting and now obsolete technologies were used as a way to reduce expenses.[118]

In 2022 the supreme court of Ecuador decided that "under no circumstances can a project be carried out that generates excessive sacrifices to the collective rights of communities and nature." It also required the government to respect the opinion of Indigenous peoples about different industrial projects on their land.[119]

Economy[edit]

Ecuador has a developing economy that is highly dependent on commodities, namely petroleum and agricultural products. The country is classified as an upper-middle-income country. Ecuador's economy is the eighth largest in Latin America and experienced an average growth of 4.6% between 2000 and 2006.[120][failed verification] From 2007 to 2012, Ecuador's GDP grew at an annual average of 4.3 percent, above the average for Latin America and the Caribbean, which was 3.5%, according to the United Nations' Economic Commission for Latin American and the Caribbean (ECLAC).[121] Ecuador was able to maintain relatively superior growth during the crisis. In January 2009, the Central Bank of Ecuador (BCE) put the 2010 growth forecast at 6.88%.[122] In 2011, its GDP grew at 8% and ranked third highest in Latin America, behind Argentina (2nd) and Panama (1st).[123] Between 1999 and 2007, GDP doubled, reaching $65,490 million according to BCE.[124]The inflation rate until January 2008, was about 1.14%, the highest in the past year, according to the government.[125][126] The monthly unemployment rate remained at about 6 and 8 percent from December 2007 until September 2008; however, it went up to about 9 percent in October and dropped again in November 2008 to 8 percent.[127] Unemployment mean annual rate for 2009 in Ecuador was 8.5% because the global economic crisis continued to affect the Latin American economies. From this point, unemployment rates started a downward trend: 7.6% in 2010, 6.0% in 2011, and 4.8% in 2012.[128]

The extreme poverty rate declined significantly between 1999 and 2010.[129] In 2001, it was estimated at 40% of the population, while by 2011 the figure dropped to 17.4% of the total population.[130] This is explained to an extent by emigration and the economic stability achieved after adopting the U.S. dollar as official means of transaction (before 2000, the Ecuadorian sucre was prone to rampant inflation). However, starting in 2008, with the bad economic performance of the nations where most Ecuadorian emigrants work, the reduction of poverty has been realized through social spending, mainly in education and health.[131]

Oil accounts for 40% of exports and contributes to maintaining a positive trade balance.[132] Since the late 1960s, the exploitation of oil increased production, and proven reserves are estimated at 6.51 billion barrels as of 2011[update].[133] In late 2021, Ecuador had to declare a Force majeure for oil exports due to erosion near key pipelines (privately owned OCP pipeline and state-owned SOTE pipeline) in the Amazon.[134] It lasted about three weeks, totalling just over $500 million economic losses, before their production returned to its normal level of 435,000 barrels per day (69,200 m3/d) in early 2022.[135]

The overall trade balance for August 2012 was a surplus of almost $390 million for the first six months of 2012, a huge figure compared with that of 2007, which reached only $5.7 million; the surplus had risen by about $425 million compared to 2006.[130] The oil trade balance positive had revenues of $3.295 million in 2008, while non-oil was negative, amounting to $2.842 million. The trade balance with the United States, Chile, the European Union, Bolivia, Peru, Brazil, and Mexico is positive. The trade balance with Argentina, Colombia, and Asia is negative.[136]

In the agricultural sector, Ecuador is a major exporter of bananas (first place worldwide in export[137]), flowers, and the seventh largest producer of cocoa.[138] Ecuador also produces coffee, rice, potatoes, cassava (manioc, tapioca), plantains and sugarcane; cattle, sheep, pigs, beef, pork and dairy products; fish, and shrimp; and balsa wood.[139] The country's vast resources include large amounts of timber across the country, like eucalyptus and mangroves.[140] Pines and cedars are planted in the region of La Sierra and walnuts, rosemary, and balsa wood in the Guayas River Basin.[141]The industry is concentrated mainly in Guayaquil, the largest industrial center, and in Quito, where in recent years the industry has grown considerably. This city is also the largest business center of the country.[142] Industrial production is directed primarily to the domestic market.[citation needed] Despite this, there is limited export of products produced or processed industrially.[citation needed] These include canned foods, liquor, jewelry, furniture, and more.[citation needed] A minor industrial activity is also concentrated in Cuenca.[143] Incomes from tourism has been increasing during the last few years due to promotion programs from Government, highlighting the variety of climates and the biodiversity of Ecuador.

Ecuador has negotiated bilateral treaties with other countries, besides belonging to the Andean Community of Nations,[144] and an associate member of Mercosur.[145] It also serves on the World Trade Organization (WTO), in addition to the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF), CAF – Development Bank of Latin America and the Caribbean and other multilateral agencies.[146][147][148] In April 2007, Ecuador paid off its debt to the IMF.[149]The public finance of Ecuador consists of the Central Bank of Ecuador (BCE), the National Development Bank (BNF), the State Bank.

Sciences and research[edit]

Ecuador was placed in 96th position of innovation in technology in a 2013 World Economic Forum study.[150] Ecuador was ranked 104th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[151][152] The most notable icons in Ecuadorian sciences are the mathematician and cartographer Pedro Vicente Maldonado, born in Riobamba in 1707, and the printer, independence precursor, and medical pioneer Eugenio Espejo, born in 1747 in Quito. Among other notable Ecuadorian scientists and engineers are Lieutenant Jose Rodriguez Labandera,[153] a pioneer who built the first submarine in Latin America in 1837; Reinaldo Espinosa Aguilar, a botanist and biologist of Andean flora; and José Aurelio Dueñas, a chemist and inventor of a method of textile serigraphy.

The major areas of scientific research in Ecuador have been in the medical fields, tropical and infectious diseases treatments, agricultural engineering, pharmaceutical research, and bioengineering. Being a small country and a consumer of foreign technology, Ecuador has favored research supported by entrepreneurship in information technology. The antivirus program Checkprogram, banking protection system MdLock, and Core Banking Software Cobis are products of Ecuadorian development.[154]

Tourism[edit]

Ecuador is a country with vast natural wealth. The diversity of its four regions has given rise to thousands of species of flora and fauna. It has approximately 1640 kinds of birds. The species of butterflies border 4,500, the reptiles 345, the amphibians 358, and the mammals 258, among others. Ecuador is considered one of the 17 countries where the planet's highest biodiversity is concentrated, being also the largest country with diversity per km2 in the world. Most of its fauna and flora live in 26 protected areas by the state.

The country has two cities with UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Quito and Cuenca, as well as two natural UNESCO World Heritage Sites: the Galapagos Islands and Sangay National Park, in addition to one World Biosphere Reserve, such as the Cajas Massif. Culturally, the Toquilla straw hat and the culture of the Zapara indigenous people are recognized. The most popular sites for national and foreign tourists have different nuances due to the various tourist activities offered by the country.

Among the main tourist destinations are:

- Nature attractions: Galápagos Islands, Yasuni National Park, El Cajas National Park, Sangay National Park, Podocarpus National Park, Vilcabamba, Baños de Agua Santa.

- Cultural attractions: Historic center of Quito, Ciudad Mitad del Mundo, Ingapirca, Historic center of Cuenca, Latacunga and its Mama Negra festival.

- Snowy mountains: Antisana volcano, Cayambe volcano, Chimborazo volcano, Cotopaxi volcano, Illinizas volcanoes.

- Beaches: Atacames, Bahía de Caráquez, Crucita, Esmeraldas, Manta, Montañita, Playas, Salinas

Transport[edit]

The rehabilitation and reopening of the Ecuadorian railroad and use of it as a tourist attraction is one of the recent developments in transportation matters.[155]

The roads of Ecuador in recent years have undergone important improvement. The major routes are Pan American (under enhancement from four to six lanes from Rumichaca to Ambato, the conclusion of four lanes on the entire stretch of Ambato and Riobamba and running via Riobamba to Loja). In the absence of the section between Loja and the border with Peru, there are the Route Espondilus or Ruta del Sol (oriented to travel along the Ecuadorian coastline) and the Amazon backbone (which crosses from north to south along the Ecuadorian Amazon, linking most and more major cities of it).

Another major project is developing the road Manta – Tena, the highway Guayaquil – Salinas Highway Aloag Santo Domingo, Riobamba – Macas (which crosses Sangay National Park). Other new developments include the National Unity bridge complex in Guayaquil, the bridge over the Napo river in Francisco de Orellana, the Esmeraldas River Bridge in the city of the same name, and, perhaps the most remarkable of all, the Bahia – San Vincente Bridge, being the largest on the Latin American Pacific coast.

Cuenca's tramway is the largest public transport system in the city and the first modern tramway in Ecuador. It was inaugurated on 8 March 2019. It has 20.4 kilometers (12.7 mi) and 27 stations. It will transport 120,000 passagers daily. Its route starts in the south of Cuenca and ends in the north at the Parque Industrial neighbourhood.

The Mariscal Sucre International Airport in Quito and the José Joaquín de Olmedo International Airport in Guayaquil have experienced a high increase in demand and have required modernization. In the case of Guayaquil it involved a new air terminal, once considered the best in South America and the best in Latin America[156] and in Quito where an entire new airport has been built in Tababela and was inaugurated in February 2013, with Canadian assistance. However, the main road leading from Quito city center to the new airport will only be finished in late 2014, making current travelling from the airport to downtown Quito as long as two hours during rush hour.[157] Quito's old city-center airport is being turned into parkland, with some light industrial use.

Demographics[edit]

Ecuador's population is ethnically diverse and the 2021 estimates put Ecuador's population at 17,797,737.[158][159] The largest ethnic group (as of 2010[update]) is the Mestizos, who are mixed race people of Amerindian and European descent, typically from Spanish colonists, in some cases this term can also include Amerindians that are culturally more Spanish influenced, and constitute about 71% of the population (although including the Montubio, a term used for coastal Mestizo population, brings this up to about 79%).

The White Ecuadorians are a minority accounting for 6.1% of the population of Ecuador and can be found throughout all of Ecuador, primarily around the urban areas. Even though Ecuador's white population during its colonial era were mainly descendants from Spain, today Ecuador's white population is a result of a mixture of European immigrants, predominantly from Spain with people from Italy, Germany, France, and Switzerland who have settled in the early 20th century. In addition, there is a small European Jewish (Ecuadorian Jews) population, which is based mainly in Quito and to a lesser extent in Guayaquil.[160] 5,000 Romani people live in Ecuador.[161]

Ecuador also has a small population of Asian origins, mainly those from West Asia, like the economically well off descendants of Lebanese and Palestinian immigrants, who are either Christian or Muslim (see Islam in Ecuador), and an East Asian community mainly consisting of those of Japanese and Chinese descent, whose ancestors arrived as miners, farmhands and fishermen in the late 19th century.[2]

Amerindians account for 7% of the current population. The mostly rural Montubio population of the coastal provinces of Ecuador, who might be classified as Pardo account for 7.4% of the population.

The Afro-Ecuadorians are a minority population (7%) in Ecuador, that includes the Mulattos and zambos, and are largely based in the Esmeraldas province and to a lesser degree in the predominantly Mestizo provinces of Coastal Ecuador – Guayas and Manabi. In the Highland Andes where a predominantly Mestizo, white and Amerindian population exist, the African presence is almost non-existent except for a small community in the province of Imbabura called Chota Valley.

Language[edit]

Spanish is the official language in Ecuador. It is spoken as a first (93%) or second language (6%) by the vast majority of its population. In 1991 Northern Kichwa (Quechua) and other pre-colonial American languages were spoken by 2,500,000. Ethnologues estimate that the country has about 24 living indigenous languages. Among the 24 are Awapit (spoken by the Awá), A'ingae (spoken by the Cofan), Shuar Chicham (spoken by the Shuar), Achuar-Shiwiar (spoken by the Achuar and the Shiwiar), Cha'palaachi (spoken by the Chachi), Tsa'fiki (spoken by the Tsáchila), Paicoca (spoken by the Siona and Secoya), and Wao Tededeo (spoken by the Waorani). Use of these Amerindian languages is gradually diminishing and being replaced by Spanish.

Most Ecuadorians speak Spanish as their first language, with its ubiquity permeating and dominating most of the country. Despite its small size the country has a marked diversity in Spanish accents that vary widely among regions. Ecuadorian Spanish idiosyncrasies reflect the ethnic and racial populations that originated and settled the distinct areas of the country.

The three main regional variants are:

Religion[edit]

According to the Ecuadorian National Institute of Statistics and Census, 91.95% of the country's population have a religion, 7.94% are atheists and 0.11% are agnostics. Among the people who have a religion, 80.44% are Catholic, 11.30% are Evangelical Protestants, 1.29% are Jehovah's Witnesses and 6.97% other (mainly Jewish, Buddhists and Latter-day Saints).[164][165]

In the rural parts of Ecuador, Amerindian beliefs and Catholicism are sometimes syncretized into a local form of folk Catholicism. Most festivals and annual parades are based on religious celebrations, many incorporating a mixture of rites and icons.[166]

There is a small number of Eastern Orthodox Christians, Amerindian religions, Muslims (see Islam in Ecuador), Buddhists and Baháʼí. According to their estimates, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints accounts for about 1.4% of the population, or 211,165 members at the end of 2012.[167] According to their sources, in 2017 there were 92,752 Jehovah's Witnesses in the country.[168]

The History of the Jews in Ecuador goes back to the 16th and 17th centuries. Until the 20th century the mayority were Sephardic with many Anusim (Crypto-Jews) among them. Ashkenazi Jews arrived mostly as refugees after the ascendance of National Socialism in Germany in 1933, with 3000 Jews in Ecuador in 1940. At its peak, in 1950, the Jewish population of Ecuador was estimated at 4,000, but then diminished to some 290 around 2020,[169][170] forming one of the smallest Jewish communities in South America. Nevertheless, this number is declining because young people leave the country for the United States or Israel. Today the Jewish Community of Ecuador (Comunidad Judía del Ecuador) has its seat in Quito. There are very small communities in Cuenca. The "Comunidad de Culto Israelita" reunites the Jews of Guayaquil. This community works independently from the "Jewish Community of Ecuador" and is composed of only 30 people.[171]

Health[edit]

The current structure of the Ecuadorian public health care system dates back to 1967.[172][173] The Ministry of the Public Health (Ministerio de Salud Pública del Ecuador) is the responsible entity of the regulation and creation of the public health policies and health care plans. The Minister of Public Health is appointed directly by the President of the Republic.

The philosophy of the Ministry of Public Health is the social support and service to the most vulnerable population,[174] and its main plan of action lies around communitarian health and preventive medicine.[174] Many American medical groups often conduct medical missions away from the big cities to provide medical health to poor communities.

The public healthcare system allows patients to be treated without an appointment in public general hospitals by general practitioners and specialists in the outpatient clinic (Consulta Externa) at no cost. This is done in the four basic specialties of pediatric, gynecology, clinic medicine, and surgery.[175] There are also public hospitals specialized to treat chronic diseases, target a particular group of the population, or provide better treatment in some medical specialties.

Although well-equipped general hospitals are found in the major cities or capitals of provinces, there are basic hospitals in the smaller towns and canton cities for family care consultation and treatments in pediatrics, gynecology, clinical medicine, and surgery.[175]

Community health care centers (Centros de Salud) are found inside metropolitan areas of cities and in rural areas. These are day hospitals that provide treatment to patients whose hospitalization is under 24 hours.[175]The doctors assigned to rural communities, where the Amerindian population can be substantial, have small clinics under their responsibility for the treatment of patients in the same fashion as the day hospitals in the major cities. The treatment in this case respects the culture of the community.[175]

The public healthcare system should not be confused with the Ecuadorian Social Security healthcare service, which is dedicated to individuals with formal employment and who are affiliated obligatorily through their employers. Citizens with no formal employment may still contribute to the social security system voluntarily and have access to the medical services rendered by the social security system. The Ecuadorian Institute of Social Security (IESS) has several major hospitals and medical sub-centers under its administration across the nation.[176]

Ecuador currently ranks 20, in most efficient health care countries, compared to 111 back in the year 2000.[177] Ecuadorians have a life expectancy of 77.1 years.[178] The infant mortality rate is 13 per 1,000 live births,[179] a major improvement from approximately 76 in the early 1980s and 140 in 1950.[180] 23% of children under five are chronically malnourished.[179] Population in some rural areas have no access to potable water, and its supply is provided by mean of water tankers. There are 686 malaria cases per 100,000 people.[181] Basic health care, including doctor's visits, basic surgeries, and basic medications, has been provided free since 2008.[179] However, some public hospitals are in poor condition and often lack necessary supplies to attend the high demand of patients. Private hospitals and clinics are well equipped but still expensive for the majority of the population.

Between 2008 and 2016, new public hospitals have been built. In 2008, the government introduced universal and compulsory social security coverage. In 2015, corruption remains a problem. Overbilling is recorded in 20% of public establishments and in 80% of private establishments.[182]

Education[edit]

The Ecuadorian Constitution requires that all children attend school until they achieve a "basic level of education", which is estimated at nine school years.[183] In 1996, the net primary enrollment rate was 96.9%, and 71.8% of children stayed in school until the fifth grade / age 10.[183] The cost of primary and secondary education is borne by the government, but families often face significant additional expenses such as fees and transportation costs.[183]

Provision of public schools falls far below the levels needed, and class sizes are often very large, and families of limited means often find it necessary to pay for education.[184] In rural areas, only 10% of the children go on to high school.[185] In a 2015 report, The Ministry of Education states that in 2014 the mean number of school years completed in rural areas is 7.39 as compared to 10.86 in urban areas.[186]

Largest cities[edit]

The five largest cities in the country are Quito (2.78 million inhabitants), Guayaquil (2.72 million inhabitants), Cuenca (636,996 inhabitants), Santo Domingo (458,580 inhabitants), and Ambato (387,309 inhabitants). The most populated metropolitan areas of the country are those of Guayaquil, Quito, Cuenca, Manabí Centro (Portoviejo-Manta) and Ambato.[187]

| Rank | Name | Province | Municipal pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Municipal pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Quito  Guayaquil | 1 | Quito | Pichincha | 2,781,641 | 11 | Riobamba | Chimborazo | 264,048 |  Cuenca  Santo Domingo |

| 2 | Guayaquil | Guayas | 2,723,665 | 12 | Ibarra | Imbabura | 221,149 | ||

| 3 | Cuenca | Azuay | 636,996 | 13 | Esmeraldas | Esmeraldas | 218,727 | ||

| 4 | Santo Domingo | Santo Domingo | 458,580 | 14 | Quevedo | Los Ríos | 213,842 | ||

| 5 | Ambato | Tungurahua | 387,309 | 15 | Latacunga | Cotopaxi | 205,624 | ||

| 6 | Portoviejo | Manabí | 321,800 | 16 | Milagro | Guayas | 199,835 | ||

| 7 | Durán | Guayas | 315,724 | 17 | Santa Elena | Santa Elena | 188,821 | ||

| 8 | Machala | El Oro | 289,141 | 18 | Babahoyo | Los Ríos | 175,281 | ||

| 9 | Loja | Loja | 274,112 | 19 | Daule | Guayas | 173,684 | ||

| 10 | Manta | Manabí | 264,281 | 20 | Quinindé | Esmeraldas | 145,879 | ||

Immigration and emigration[edit]

Ecuador houses a small East Asian community mainly consisting of those of Japanese and Chinese descent, whose ancestors arrived as miners, farmhands and fishermen in the late 19th century.[2]

In the early years of World War II, Ecuador still admitted a certain number of immigrants, and in 1939, when several South American countries refused to accept 165 Jewish refugees from Germany aboard the ship Koenigstein, Ecuador granted them entry permits.[188]

Migration from Lebanon to Ecuador started as early as 1875.[189] Early impoverished migrants tended to work as independent sidewalk vendors, rather than as wage workers in agriculture or others' businesses.[190] Though they emigrated to escape Ottoman Turkish religious oppression, they were called "Turks" by Ecuadorians because they carried Ottoman passports.[191] There were further waves of immigration in the first half of the 20th century; by 1930, there were 577 Lebanese immigrants and 489 of their descendants residing in the country. A 1986 estimate from Lebanon's Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated 100,000 Lebanese descendants.[192] They reside mostly in Quito and Guayaquil. They are predominantly Roman Catholics.

В начале 1900-х годов наблюдалась иммиграция итальянцев , немцев , португальцев , французов , британцев , ирландцев и греков . Город Анкон испытал волну иммиграции из Великобритании, начиная с 1911 года, когда правительство Эквадора уступило британской нефтяной компании Anglo Ecuadorian Oilfields 98 шахт, занимающих площадь 38 842 га. Сегодня Anglo American Oilfields или Anglo American plc является крупнейшим в мире производителем платины, на долю которого приходится около 40% мирового производства, а также крупным производителем алмазов, меди, никеля, железной руды и сталелитейного угля. Альберто Спенсер – знаменитый британец, родом из Анкона. Город теперь стал достопримечательностью благодаря строгим британским домам в «Эль-Баррио-Инглес», расположенным в контрастном тропическом окружении. [193] [194]

В 1950-е годы итальянцы были третьей по численности национальной группой иммигрантов. Можно отметить, что после Первой мировой войны выходцы из Лигурии по-прежнему составляли большую часть потока, хотя тогда они представляли лишь одну треть от общего числа иммигрантов в Эквадоре. Такая ситуация возникла из-за улучшения экономической ситуации в Лигурии. Классическая парадигма современного итальянского иммигранта не была парадигмой мелкого торговца из Лигурии, как это было раньше; в Эквадор эмигрировали профессионалы и техники, служащие и религиозные люди из южно-центральной Италии. Следует помнить, что многие иммигранты, среди которых значительное число итальянцев, переехали в эквадорский порт из Перу, спасаясь от перуанской войны с Чили. Итальянское правительство стало больше интересоваться феноменом эмиграции в Эквадоре из-за необходимости найти выход для большого количества иммигрантов, которые традиционно уезжали в Соединенные Штаты. но которые больше не могли въезжать в эту страну из-за Закона о чрезвычайных квотах 1921 года, который ограничивал иммиграцию жителей Южной и Восточной Европы, а также других «нежелательных лиц».

Большинство этих общин и их потомков расположены в регионе Гуаяс страны. [195]