Коренные народы Америки

Текущее распределение коренных народов Америки | |

| Общая численность населения | |

|---|---|

| Около 62 миллионов | |

| Регионы со значительной численностью населения | |

| 11,8 - 23,2 миллиона [1] [2] | |

| 3,7 - 9,6 миллионов [3] | |

| 6,4 миллиона [4] | |

| 5,9 миллиона [5] | |

| 4,1 миллиона [6] | |

| 2,1 миллиона [7] | |

| 1,9 миллиона [8] | |

| 1,8 миллиона [9] | |

| 1,7 миллиона [10] | |

| 1,3 миллиона [11] | |

| 1,3 миллиона [12] | |

| 724,592 [13] | |

| 698,114 [14] | |

| 601,019 [15] | |

| 443,847 [16] | |

| 140,039 [17] | |

| 104,143 [18] | |

| 78,492 [19] | |

| 76,452 [20] | |

| 50,189 [21] | |

| 36,507 [22] | |

| 20,344 [23] | |

| 19,839 [24] | |

| ~19,000 [25] | |

| 13,310 [26] | |

| 3,280 [27] | |

| 2,576 [28] | |

| 1,394 [29] | |

| 951 [30] | |

| 327 [31] | |

| 162 [32] | |

| 8 [33] | |

| Языки | |

| Многочисленные языки коренных американцев (как существующие, так и вымершие). Неродные европейские языки: Испанский , английский , португальский , французский , датский , голландский и русский (ранее на Аляске) | |

| Религия | |

| Преимущественно христианство ( католическое и протестантское ). Меньшинство: различные религии коренных американцев. | |

| Родственные этнические группы | |

| Метисы , метисы , замбос и пардос Отдаленно связан с некоторыми коренными сибирскими народами. | |

Коренные народы Америки — это группы людей, проживающих в определенном регионе, населявшие Америку до прибытия европейских поселенцев в 15 веке, и этнические группы, которые продолжают идентифицировать себя с этими народами. [34]

Коренные народы Америки разнообразны; некоторые коренные народы исторически были охотниками-собирателями , тогда как другие традиционно занимались сельским хозяйством и аквакультурой . В некоторых регионах коренные народы до контакта создали монументальную архитектуру, крупномасштабные организованные города, города-государства , вождества , государства, королевства, республики, конфедерации и империи. [35] Эти общества имели разную степень знаний в области инженерии, архитектуры, математики, астрономии, письма, физики, медицины, растениеводства и ирригации, геологии, горного дела, металлургии, скульптуры и ювелирного дела.

Многие части Америки все еще населены коренными народами ; в некоторых странах имеется значительное население, особенно в Боливии , Канаде , Чили , Колумбии , Эквадоре , Гватемале , Мексике , Перу и США . По крайней мере, на тысяче различных языков коренных народов говорят в Америке, где только в Соединенных Штатах также проживает 574 признанных на федеральном уровне племени . Некоторые из этих языков признаны официальными правительствами ряда стран, например, в Боливии, Перу, Парагвае и Гренландии . Некоторые, такие как кечуа , аравак , аймара , гуарани , майя и науатль , насчитывают миллионы носителей. Независимо от того, живут ли современные коренные народы в сельских общинах или в городах, многие из них также в разной степени сохраняют дополнительные аспекты своей культурной практики, включая религию, социальную организацию и существования методы . Как и большинство культур, с течением времени культуры, характерные для многих коренных народов, также развивались, сохраняя традиционные обычаи, но также приспосабливаясь к современным потребностям. Некоторые коренные народы до сих пор живут в относительной изоляции от Западная культура и некоторые из них до сих пор считаются неконтактными народами . [36] Коренные народы Америки также сформировали диаспоры за пределами Западного полушария, а именно в бывших колониальных центрах Европы. Ярким примером является значительная община гренландских инуитов в Дании. [37] В 20-м и 21-м веках коренные народы из Суринама и Французской Гвианы мигрировали в Нидерланды и Францию соответственно. [38] [39]

Терминология [ править ]

Применение термина « индеец » возникло у Христофора Колумба , который в поисках Индии думал, что прибыл в Ост-Индию . [40] [41] [42] [43] [44] [45]

Острова стали известны как « Вест-Индия » — это название до сих пор используется для описания островов. Это привело к появлению общего термина «Индии» и «индейцы» ( испанский : indios ; португальский : índios ; французский : indiens ; нидерландский : indianen ) для коренных жителей, что подразумевало некое этническое или культурное единство среди коренных народов Америки. Эта объединяющая концепция, закрепленная в законодательстве, религии и политике, изначально не была принята множеством групп коренных народов, но с тех пор была принята или терпима многими на протяжении последних двух столетий. [46] Термин «индейцы» обычно не включает в себя культурно и лингвистически отличающиеся коренные народы арктических регионов Америки, включая алеутов , инуитов или юпиков . Эти народы прибыли на континент в результате второй, более поздней волны миграции, несколько тысяч лет спустя, и имеют гораздо более позднее генетическое и культурное сходство с коренными народами Сибири . Однако эти группы, тем не менее, считаются «коренными народами Америки». [47]

Термин «американский индеец », производное от слова «американский индеец», был придуман в 1902 году Американской антропологической ассоциацией . Он вызывает споры с момента своего создания. Он был немедленно отвергнут некоторыми ведущими членами Ассоциации, и, хотя он был принят многими, он так и не получил всеобщего признания. [48] Хотя этот термин никогда не был популярен среди самих коренных народов, он остается предпочтительным термином среди некоторых антропологов, особенно в некоторых частях Канады и англоязычных стран Карибского бассейна . [49] [50] [51] [52]

« Коренные народы Канады » используется как собирательное название для коренных народов , инуитов и метисов . [53] [54] Термин «аборигенные народы» как собирательное существительное (также описывающий коренные народы, инуиты и метисы) представляет собой особый художественный термин, используемый в некоторых юридических документах, включая Конституционный закон 1982 года . [55] Со временем, когда общественное восприятие и отношения между правительством и коренными народами изменились, многие исторические термины изменили определения или были заменены, поскольку они вышли из моды. [56] Использование термина «индейцы» не одобряется, поскольку оно представляет собой навязывание и ограничение коренных народов и культур со стороны канадского правительства. [56] Термины «туземец» и « эскимос » обычно считаются неуважительными (в Канаде) и поэтому редко используются, если в этом нет особой необходимости. [57] Хотя предпочтительным термином является «коренные народы», многие отдельные лица или сообщества могут решить описать свою идентичность, используя другой термин. [56] [57]

Метисов Канады можно противопоставить, например, коренным европейцам метисов смешанной расы (или кабокло в Бразилии) латиноамериканской Америки , которые, с их более многочисленным населением (в большинстве стран Латинской Америки, составляют либо явное большинство, множественность или по крайней мере, крупные меньшинства), идентифицируют себя в основном как новую этническую группу, отличную как от европейцев, так и от коренных народов, но все же считающую себя частью латиноамериканского или бразильского народа европейского происхождения по культуре и этнической принадлежности ( ср. ladinos ).

В испаноязычных странах indígenas или pueblos indígenas («коренные народы») является распространенным термином, хотя nativos или pueblos nativos также можно услышать («коренные народы»). кроме того, слово aborigen используется в Аргентине («абориген») , а слово pueblos originarios распространено в Чили («коренные народы») . В Бразилии indígenas и povos originários («Коренные народы») являются общепринятыми формально звучащими обозначениями, в то время как índio («индеец») по-прежнему является наиболее часто употребляемым термином (существительное, обозначающее южноазиатскую национальность, — «индиано» ), но для последние 10 лет считались оскорбительными и уничижительными. [ нужна ссылка ] Aborígene и nativo редко используются в Бразилии в контексте, специфичном для коренных народов (например, абориген обычно понимается как этноним коренных австралийцев ). Тем не менее, испанские и португальские эквиваленты слова Indian могут использоваться для обозначения любого охотника-собирателя или чистокровного коренного населения, особенно на континентах, отличных от Европы или Африки, например, indios filipinos . [ нужна ссылка ]

Коренные народы Соединенных Штатов широко известны как коренные американцы , индейцы, а также коренные жители Аляски . [ нужны разъяснения ] Термин «индеец» до сих пор используется в некоторых общинах и используется в официальных названиях многих учреждений и предприятий в индийской стране . [58]

Споры по имени [ править ]

Различные нации, племена и группы коренных народов Америки имеют разные предпочтения в терминологии. [59] Хотя существуют региональные различия и различия между поколениями, в которых общие термины являются предпочтительными для коренных народов в целом, в целом большинство коренных народов предпочитают, чтобы их идентифицировали по названию их конкретной нации, племени или группы. [59] [60]

Ранние поселенцы часто использовали термины, которые некоторые племена использовали друг для друга, не осознавая, что это были уничижительные термины, используемые врагами. При обсуждении более широких подмножеств народов имена часто основывались на общем языке, регионе или исторических отношениях. [61] Многие английские экзонимы использовались для обозначения коренных народов Америки. Некоторые из этих названий были основаны на терминах иностранных языков, использовавшихся более ранними исследователями и колонистами, тогда как другие возникли в результате попыток колонистов перевести или транслитерировать эндонимы с родных языков. Другие термины возникли в периоды конфликтов между колонистами и коренными народами. [62]

С конца 20-го века коренные народы Америки стали более открыто заявлять о том, как к ним должны относиться, стремясь запретить использование терминов, которые многие считают устаревшими, неточными или расистскими . Во второй половине 20-го века, когда возникло движение за права индейцев , федеральное правительство Соединенных Штатов в ответ предложило использовать термин « коренной американец », чтобы признать главенство владения коренными народами в стране. [63] Как и следовало ожидать, среди людей, принадлежащих к более чем 400 различным культурам только в США, не все люди, которых предполагалось описать этим термином, согласились с его использованием или приняли его. Ни одно соглашение об именовании групп не было принято всеми коренными народами Америки. Большинство предпочитает, чтобы к ним обращались как к представителям своего племени или нации, если не говорить о коренных американцах/американских индейцах в целом. [64]

С 1970-х годов слово «коренной народ», которое применительно к людям пишется с заглавной буквы, постепенно стало излюбленным общим термином. Использование заглавных букв означает признание того, что коренные народы имеют культуру и общество, которые равны европейцам, африканцам и азиатам. [60] [65] Недавно это было признано в книге стилей AP . [66] Некоторые считают неправильным называть коренные народы «коренными американцами» или добавлять к этому термину какую-либо колониальную национальность, поскольку культуры коренных народов существовали до европейской колонизации. Группы коренных народов имеют территориальные претензии, которые отличаются от современных национальных и международных границ, и когда их называют частью страны, их традиционные земли не признаются. Некоторые из тех, кто написал руководящие принципы, считают более уместным описывать коренного населения как «живущего в» или «из» Америки, а не называть его «американцем»; или просто называть их «коренными» без добавления колониального государства. [67] [68]

История [ править ]

Заселение Америки [ править ]

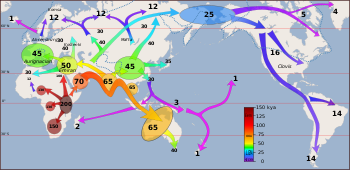

Заселение Америки началось, когда палеолитические охотники-собиратели ( палеоиндейцы ) проникли в Северную Америку из североазиатской Мамонтовой степи через Берингийский сухопутный мост , образовавшийся между северо-восточной Сибирью и западной Аляской в связи с понижением уровня моря во время последней Ледниковый максимум (26 000–19 000 лет назад). [70] Эти популяции распространились к югу от Лаврентийского ледникового щита и быстро распространились на юг, заселив как Северную, так и Южную Америку , 12–14 000 лет назад. [71] [72] [73] [74] [75] Самые ранние популяции в Америке, возникшие примерно 10 000 лет назад, известны как палеоиндейцы . Коренные народы Америки были связаны с сибирским населением лингвистическими факторами , распределением групп крови и генетическим составом , что отражено молекулярными данными, такими как ДНК . [76] [77]

Хотя существует общее мнение, что Америка была впервые заселена из Азии, характер миграции и место(а) происхождения в Евразии народов, мигрировавших в Америку, остаются неясными. [72] Традиционная теория состоит в том, что древние берингийцы переселились, когда уровень моря значительно снизился из-за четвертичного оледенения . [78] [79] преследуя стада ныне вымершей плейстоценовой мегафауны по свободным ото льда коридорам , простирающимся между ледниковыми щитами Лаврентиды и Кордильеров . [80] Другой предложенный маршрут заключается в том, что пешком или на лодках они мигрировали вдоль побережья Тихого океана в Южную Америку до Чили . [81] Любые археологические свидетельства оккупации побережья во время последнего ледникового периода теперь были бы скрыты повышением уровня моря , которое с тех пор достигло ста метров. [82]

Точная дата заселения Америки является давним открытым вопросом, и хотя достижения в археологии , плейстоцена геологии , физической антропологии и анализе ДНК постепенно проливают больше света на эту тему, важные вопросы остаются нерешенными. [83] [84] «Первая теория Хлодвига» относится к гипотезе о том, что культура Хлодвига представляет собой самое раннее присутствие человека на Америке около 13 000 лет назад. [85] Свидетельства существования культур, существовавших до Хлодвига, накопились и отодвинули возможную дату первого заселения Америки. [86] [87] [88] [89] Академики обычно полагают, что люди достигли Северной Америки к югу от ледникового щита Лаврентида где-то между 15 000 и 20 000 лет назад. [83] [86] [90] [91] [92] [93] Некоторые новые противоречивые археологические данные предполагают, что прибытие людей в Америку могло произойти до последнего ледникового максимума, более 20 000 лет назад. [86] [94] [95] [96] [97]Доколумбовая эпоха [ править ]

Хотя технически этот термин относится к эпохе, предшествовавшей путешествиям Христофора Колумба с 1492 по 1504 год, на практике этот термин обычно включает в себя историю культур коренных народов до тех пор, пока европейцы либо не завоевали их, либо не оказали на них существенного влияния. [101] «Доколумбовый период» особенно часто используется в контексте обсуждения доконтактных Мезоамерики обществ коренных народов : ольмеков ; Толтек ; Теотиуакано Сапотек ; Микстек ; цивилизации ацтеков и майя ; и сложные культуры Анд : Империя инков , культура Моче , Конфедерация Муиска и Каньяри .

Доколумбовая эпоха относится ко всем периодам в истории и предыстории Америки до появления значительных европейских и африканских влияний на американских континентах, охватывая время от первоначального прибытия в верхний палеолит до европейской колонизации в раннем Новом времени. период . [102] Цивилизация Норте-Чико (на территории современного Перу) — одна из шести определяющих первоначальных цивилизаций мира, возникшая независимо примерно в то же время, что и цивилизация Египта . [103] [104] Многие более поздние доколумбовые цивилизации достигли огромной сложности, отличительными чертами которых были постоянные или городские поселения, сельское хозяйство, инженерное дело, астрономия, торговля, гражданская и монументальная архитектура, а также сложные социальные иерархии . Некоторые из этих цивилизаций уже давно исчезли ко времени первых значительных поселений европейцев и африканцев (приблизительно конец 15 – начало 16 веков) и известны только из устной истории и благодаря археологическим исследованиям. Другие были современниками периода контактов и колонизации и были задокументированы в исторических отчетах того времени. Некоторые народы, такие как майя, ольмеки, миштеки, ацтеки и науа , имели свои письменные языки и записи. Однако европейские колонисты того времени работали над искоренением нехристианских верований и сожгли множество письменных источников доколумбовой эпохи. Лишь несколько документов остались скрытыми и сохранились, оставив современным историкам представление о древней культуре и знаниях.

Согласно отчетам и документам как коренных народов, так и европейцев, американские цивилизации до и во время встречи с европейцами достигли огромной сложности и многих достижений. [105] Например, ацтеки построили один из крупнейших городов в мире, Теночтитлан (историческое место того, что впоследствии стало Мехико ), с предполагаемым населением 200 000 человек в самом городе и около пяти миллионов человек в расширенной империи. . [106] Для сравнения, крупнейшими европейскими городами XVI века были Константинополь и Париж с населением 300 000 и 200 000 человек соответственно. [107] Население Лондона, Мадрида и Рима едва превышало 50 000 человек. В 1523 году, примерно во время испанского завоевания, все население Англии составляло чуть менее трех миллионов человек. [108] Этот факт говорит об уровне развития сельского хозяйства, государственных процедур и верховенства закона, существовавших в Теночтитлане и необходимых для управления таким большим населением. Коренные цивилизации также продемонстрировали впечатляющие достижения в астрономии и математике, включая самый точный календарь в мире. [ нужна ссылка ] Одомашнивание кукурузы или кукурузы потребовало тысяч лет селекционной селекции, а дальнейшее выращивание нескольких сортов осуществлялось путем планирования и отбора, как правило, женщинами.

инуитов, юпиков, алеутов и коренных народов Мифы о творении рассказывают о различном происхождении соответствующих народов. Некоторые были «всегда здесь» или были созданы богами или животными, некоторые мигрировали из определенной точки компаса , а другие пришли «из-за океана». [109]

Европейская колонизация [ править ]

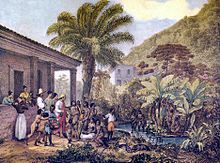

The European colonization of the Americas fundamentally changed the lives and cultures of the resident Indigenous peoples. Although the exact pre-colonization population count of the Americas is unknown, scholars estimate that Indigenous populations diminished by between 80% and 90% during the first centuries of European colonization. Most scholars estimate a pre-colonization population of around 50 million, with other scholars arguing for an estimate of 100 million. Estimates reach as high as 145 million.[110][111][112]

Epidemics ravaged the Americas with diseases, such as smallpox, measles, and cholera, which the early colonists brought from Europe. The spread of infectious diseases was slow initially, as most Europeans were not actively or visibly infected, due to inherited immunity from generations of exposure to these diseases in Europe. This changed when the Europeans began the human trafficking of massive numbers of enslaved Western and Central African people to the Americas. Like Indigenous peoples, these African people, newly exposed to European diseases, lacked any inherited resistance to the diseases of Europe. In 1520, an African who had been infected with smallpox had arrived in Yucatán. By 1558, the disease had spread throughout South America and had arrived at the Plata basin.[113] Colonist violence towards Indigenous peoples accelerated the loss of lives. European colonists perpetrated massacres on the Indigenous peoples and enslaved them.[114][115][116] According to the U.S. Bureau of the Census (1894), the North American Indian Wars of the 19th century had a known death toll of about 19,000 Europeans and 30,000 Native Americans, and an estimated total death toll of 45,000 Native Americans.[117]

The first Indigenous group encountered by Columbus, the 250,000 Taínos of Hispaniola, represented the dominant culture in the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas. Within thirty years about 70% of the Taínos had died.[118] They had no immunity to European diseases, so outbreaks of measles and smallpox ravaged their population.[119] One such outbreak occurred in a camp of enslaved Africans, where smallpox spread to the nearby Taíno population and reduced their numbers by 50%.[113] Increasing punishment of the Taínos for revolting against forced labor, despite measures put in place by the encomienda, which included religious education and protection from warring tribes,[120] eventually led to the last great Taíno rebellion (1511–1529).

Following years of mistreatment, the Taínos began to adopt suicidal behaviors, with women aborting or killing their infants and men jumping from cliffs or ingesting untreated cassava, a violent poison.[118] Eventually, a Taíno Cacique named Enriquillo managed to hold out in the Baoruco Mountain Range for thirteen years, causing serious damage to the Spanish, Carib-held plantations and their Indian auxiliaries.[121][failed verification] Hearing of the seriousness of the revolt, Emperor Charles V (also King of Spain) sent Captain Francisco Barrionuevo to negotiate a peace treaty with the ever-increasing number of rebels. Two months later, after consultation with the Audencia of Santo Domingo, Enriquillo was offered any part of the island to live in peace.

The Laws of Burgos, 1512–1513, were the first codified set of laws governing the behavior of Spanish settlers in America, particularly concerning Indigenous peoples. The laws forbade the maltreatment of them and endorsed their conversion to Catholicism.[122] The Spanish crown found it difficult to enforce these laws in distant colonies.

Epidemic disease was the overwhelming cause of the population decline of the Indigenous peoples.[123][124] After initial contact with Europeans and Africans, Old World diseases caused the deaths of 90 to 95% of the native population of the New World in the following 150 years.[125] Smallpox killed from one-third to half of the native population of Hispaniola in 1518.[126][127] By killing the Incan ruler Huayna Capac, smallpox caused the Inca Civil War of 1529–1532. Smallpox was only the first epidemic. Typhus (probably) in 1546, influenza and smallpox together in 1558, smallpox again in 1589, diphtheria in 1614, and measles in 1618—all ravaged the remains of Inca culture.

Smallpox killed millions of native inhabitants of Mexico.[128][129] Unintentionally introduced at Veracruz with the arrival of Pánfilo de Narváez on 23 April 1520, smallpox ravaged Mexico in the 1520s,[130] possibly killing over 150,000 in Tenochtitlán (the heartland of the Aztec Empire) alone, and aiding in the victory of Hernán Cortés over the Aztec Empire at Tenochtitlan (present-day Mexico City) in 1521.[citation needed][113]

There are many factors as to why Indigenous peoples suffered such immense losses from Afro-Eurasian diseases. Many European diseases, like cow pox, are acquired from domesticated animals that are not indigenous to the Americas. European populations had adapted to these diseases, and built up resistance, over many generations. Many of the European diseases that were brought over to the Americas were diseases, like yellow fever, that were relatively manageable if infected as a child, but were deadly if infected as an adult. Children could often survive the disease, resulting in immunity to the disease for the rest of their lives. But contact with adult populations without this childhood or inherited immunity would result in these diseases proving fatal.[113][131]

Colonization of the Caribbean led to the destruction of the Arawaks of the Lesser Antilles. Their culture was destroyed by 1650. Only 500 had survived by the year 1550, though the bloodlines continued through to the modern populace. In Amazonia, Indigenous societies weathered, and continue to suffer, centuries of colonization and genocide.[132]

Contact with European diseases such as smallpox and measles killed between 50 and 67 percent of the Indigenous population of North America in the first hundred years after the arrival of Europeans.[133] Some 90 percent of the native population near Massachusetts Bay Colony died of smallpox in an epidemic in 1617–1619.[134] In 1633, in Fort Orange (New Netherland), the Native Americans there were exposed to smallpox because of contact with Europeans. As it had done elsewhere, the virus wiped out entire population groups of Native Americans.[135] It reached Lake Ontario in 1636, and the lands of the Iroquois by 1679.[136][137] During the 1770s smallpox killed at least 30% of the West Coast Native Americans.[138] The 1775–82 North American smallpox epidemic and the 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic brought devastation and drastic population depletion among the Plains Indians.[139][140] In 1832 the federal government of the United States established a smallpox vaccination program for Native Americans (The Indian Vaccination Act of 1832).[141]

The Indigenous peoples in Brazil declined from a pre-Columbian high of an estimated three million[142] to some 300,000 in 1997.[dubious – discuss][failed verification][143]

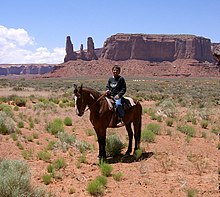

The Spanish Empire and other Europeans re-introduced horses to the Americas. Some of these animals escaped and began to breed and increase their numbers in the wild.[144] The reintroduction of the horse, extinct in the Americas for over 7500 years, had a profound impact on Indigenous cultures in the Great Plains of North America and in the Gran Chaco and Patagonia in South America. By domesticating horses, some tribes had great success: horses enabled them to expand their territories, exchange more goods with neighboring tribes, and more easily capture game, especially bison.

According to Erin McKenna and Scott L. Pratt, the Indigenous population of the Americas was 145 million in the late 15th and by the late 17th century, had been reduced to 15 million due to epidemics, wars, massacres, mass rapes, starvation, and enslavement.[112]

Indigenous historical trauma[edit]

Indigenous historical trauma (IHT) is the trauma that can accumulate across generations and develop as a result of the historical ramifications of colonization and is linked to mental and physical health hardships and population decline.[145] IHT affects many different people in a multitude of ways because the Indigenous community and their history are diverse.

Many studies (such as Whitbeck et al., 2014;[146] Brockie, 2012; Anastasio et al., 2016;[147] Clark & Winterowd, 2012;[148] Tucker et al., 2016)[149] have evaluated the impact of IHT on health outcomes of Indigenous communities from the United States and Canada. IHT is a difficult term to standardize and measure because of the vast and variable diversity of Indigenous people and their communities. Therefore, it is an arduous task to assign an operational definition and systematically collect data when studying IHT. Many of the studies that incorporate IHT measure it in different ways, making it hard to compile data and review it holistically. This is an important point that provides context for the following studies that attempt to understand the relationship between IHT and potential adverse health impacts.

Some of the methodologies to measure IHT include a "Historical Losses Scale" (HLS), "Historical Losses Associated Symptoms Scale" (HLASS), and residential school ancestry studies.[145]: 23 HLS uses a survey format that includes "12 kinds of historical losses", such as loss of language and loss of land and asks participants how often they think about those losses.[145]: 23 The HLASS includes 12 emotional reactions, and asks participants how they feel when they think about these losses.[145] Lastly, the residential school ancestry studies ask respondents if their parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, or "elders from their community" went to a residential school to understand if family or community history in residential schools is associated with negative health outcomes.[145]: 25 In a comprehensive review of the research literature, Joseph Gone and colleagues[145] compiled and compared outcomes for studies using these IHT measures relative to the health outcomes of Indigenous peoples. The study defined negative health outcomes to include such concepts as anxiety, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, polysubstance abuse, PTSD, depression, binge eating, anger, and sexual abuse.[145]

The connection between IHT and health conditions is complicated because of the difficult nature of measuring IHT, the unknown directionality of IHT and health outcomes, and because the term Indigenous people used in the various samples comprises a huge population of individuals with drastically different experiences and histories. That being said some studies such as Bombay, Matheson, and Anisman (2014),[150] Elias et al. (2012),[151] and Pearce et al. (2008)[152] found that Indigenous respondents with a connection to residential schools have more negative health outcomes (e.g., suicide ideation, suicide attempts, and depression) than those who did not have a connection to residential schools. Additionally, Indigenous respondents with higher HLS and HLASS scores had one or more negative health outcomes.[145] While there are many studies[147][153][148][154][149] that found an association between IHT and adverse health outcomes, scholars continue to suggest that it remains difficult to understand the impact of IHT. IHT needs to be systematically measured. Indigenous people also need to be understood in separate categories based on similar experiences, location, and background as opposed to being categorized as one monolithic group.[145]

Agriculture[edit]

Plants[edit]

For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples domesticated, bred, and cultivated a large array of plant species. These species now constitute between 50% and 60% of all crops in cultivation worldwide.[155] In certain cases, the Indigenous peoples developed entirely new species and strains through artificial selection, as with the domestication and breeding of maize from wild teosinte grasses in the valleys of southern Mexico. Numerous such agricultural products retain their native names in the English and Spanish lexicons.

The South American highlands became a center of early agriculture. Genetic testing of the wide variety of cultivars and wild species suggests that the potato has a single origin in the area of southern Peru,[156] from a species in the Solanum brevicaule complex. Over 99% of all modern cultivated potatoes worldwide are descendants of a subspecies Indigenous to south-central Chile,[157] Solanum tuberosum ssp. tuberosum, where it was cultivated as long as 10,000 years ago.[158][159] According to Linda Newson, "It is clear that in pre-Columbian times some groups struggled to survive and often suffered food shortages and famines, while others enjoyed a varied and substantial diet."[160]

Persistent drought around AD 850 coincided with the collapse of the Classic Maya civilization, and the famine of One Rabbit (AD 1454) was a major catastrophe in Mexico.[161]

Indigenous peoples of North America began practicing farming approximately 4,000 years ago, late in the Archaic period of North American cultures. Technology had advanced to the point where pottery had started to become common and the small-scale felling of trees had become feasible. Concurrently, the Archaic Indigenous peoples began using fire in a controlled manner. They carried out the intentional burning of vegetation to mimic the effects of natural fires that tended to clear forest understories. It made travel easier and facilitated the growth of herbs and berry-producing plants, which were important both for food and for medicines.[162]

In the Mississippi River valley, Europeans noted that Native Americans managed groves of nut and fruit trees not far from villages and towns and their gardens and agricultural fields. They would have used prescribed burning further away, in forest and prairie areas.[163]

Many crops first domesticated by Indigenous peoples are now produced and used globally, most notably maize (or "corn") arguably the most important crop in the world.[164] Other significant crops include cassava; chia; squash (pumpkins, zucchini, marrow, acorn squash, butternut squash); the pinto bean, Phaseolus beans including most common beans, tepary beans, and lima beans; tomatoes; potatoes; sweet potatoes; avocados; peanuts; cocoa beans (used to make chocolate); vanilla; strawberries; pineapples; peppers (species and varieties of Capsicum, including bell peppers, jalapeños, paprika, and chili peppers); sunflower seeds; rubber; brazilwood; chicle; tobacco; coca; blueberries, cranberries, and some species of cotton.

Studies of contemporary Indigenous environmental management—including agro-forestry practices among Itza Maya in Guatemala and hunting and fishing among the Menominee of Wisconsin—suggest that longstanding "sacred values" may represent a summary of sustainable millennial traditions.[165]

Animals[edit]

Numerous Native American dog breeds have been used by the people of the Americas, such as the Canadian Eskimo dog, the Carolina dog, and the Chihuahua. Some indigenous peoples in the Great Plains used dogs for pulling travois, while others like the Tahltan bear dog were bred to hunt larger game. Some Andean cultures also bred the Chiribaya to herd llamas. The vast majority of dog breeds in the Americas went extinct, due to being replaced by dogs of European origin.[166]

The Fuegian dog was a domesticated variation of the culpeo that was raised by several cultures in Tierra del Fuego, like the Selk'nam and the Yahgan.[167] It was exterminated by Argentine and Chilean settlers, due to supposedly posing as a threat to livestock.[168]

Several bird species, such as turkeys, Muscovy ducks, Puna ibis, and neotropic cormorants were domesticated by various peoples in Mesoamerica and South America to be used for poultry.

In the Andean region, indigenous peoples domesticated llamas and alpacas to produce fiber and meat. The llama was the only beast of burden in the Americas before European colonization.

Guinea pigs were domesticated from wild cavies to be raised for meat consumption in the Andean region. Guinea pigs are now widely raised in Western society as household pets.

Culture[edit]

Cultural practices in the Americas seem to have been shared mostly within geographical zones where distinct ethnic groups adopt shared cultural traits, similar technologies, and social organizations. An example of such a cultural area is Mesoamerica, where millennia of coexistence and shared development among the peoples of the region produced a fairly homogeneous culture with complex agricultural and social patterns. Another well-known example is the North American plains where until the 19th century several peoples shared the traits of nomadic hunter-gatherers based primarily on bison hunting.

Languages[edit]

The languages of the North American Indians have been classified into 56 groups or stock tongues, in which the spoken languages of the tribes may be said to center. In connection with speech, reference may be made to gesture language which was highly developed in parts of this area. Of equal interest is the picture writing especially well developed among the Chippewas and Delawares.[169]

Writing systems[edit]

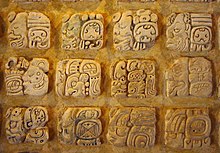

Beginning in the 1st millennium BCE, pre-Columbian cultures in Mesoamerica developed several Indigenous writing systems (independent of any influence from the writing systems that existed in other parts of the world). The Cascajal Block is perhaps the earliest-known example in the Americas of what may be an extensive written text. The Olmec hieroglyphs tablet has been indirectly dated (from ceramic shards found in the same context) to approximately 900 BCE which is around the same time that the Olmec occupation of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán began to weaken.[170]

The Maya writing system was logosyllabic (a combination of phonetic syllabic symbols and logograms). It is the only pre-Columbian writing system known to have completely represented the spoken language of its community. It has more than a thousand different glyphs, but a few are variations on the same sign or have the same meaning, many appear only rarely or in particular localities, no more than about five hundred were in use in any given time, and, of those, it seems only about two hundred (including variations) represented a particular phoneme or syllable.[171][172][173]

The Zapotec writing system, one of the earliest in the Americas,[174] was logographic and presumably syllabic.[174] There are remnants of Zapotec writing in inscriptions on some of the monumental architecture of the period, but so few inscriptions are extant that it is difficult to fully describe the writing system. The oldest example of the Zapotec script, dating from around 600 BCE, is on a monument that was discovered in San José Mogote.[175]

Aztec codices (singular codex) are books that were written by pre-Columbian and colonial-era Aztecs. These codices are some of the best primary sources for descriptions of Aztec culture. The pre-Columbian codices are largely pictorial; they do not contain symbols that represent spoken or written language.[176] By contrast, colonial-era codices contain not only Aztec pictograms, but also writing that uses the Latin alphabet in several languages: Classical Nahuatl, Spanish, and occasionally Latin.

Spanish mendicants in the sixteenth century taught Indigenous scribes in their communities to write their languages using Latin letters, and there are a large number of local-level documents in Nahuatl, Zapotec, Mixtec, and Yucatec Maya from the colonial era, many of which were part of lawsuits and other legal matters. Although Spaniards initially taught Indigenous scribes alphabetic writing, the tradition became self-perpetuating at the local level.[177] The Spanish crown gathered such documentation, and contemporary Spanish translations were made for legal cases. Scholars have translated and analyzed these documents in what is called the New Philology to write histories of Indigenous peoples from Indigenous viewpoints.[178]

The Wiigwaasabak, birch bark scrolls on which the Ojibwa (Anishinaabe) people wrote complex geometrical patterns and shapes, can also be considered a form of writing, as can Mi'kmaq hieroglyphics.

Aboriginal syllabic writing, or simply syllabics, is a family of abugidas used to write some Indigenous languages of the Algonquian, Inuit, and Athabaskan language families.

Music and art[edit]

Indigenous music can vary between cultures, however, there are significant commonalities. Traditional music often centers around drumming and singing. Rattles, clapper sticks, and rasps are also popular percussive instruments, both historically and in contemporary cultures. Flutes are made of river cane, cedar, and other woods. The Apache have a type of fiddle, and fiddles are also found many First Nations and Métis cultures.

The music of the Indigenous peoples of Central Mexico and Central America, like that of the North American cultures, tends to be spiritual ceremonies. It traditionally includes a large variety of percussion and wind instruments such as drums, flutes, sea shells (used as trumpets), and "rain" tubes. No remnants of pre-Columbian stringed instruments were found until archaeologists discovered a jar in Guatemala, attributed to the Maya of the Late Classic Era (600–900 CE); this jar was decorated with imagery depicting a stringed musical instrument which has since been reproduced. This instrument is one of the very few stringed instruments known in the Americas before the introduction of European musical instruments; when played, it produces a sound that mimics a jaguar's growl.[179]

Visual arts by Indigenous peoples of the Americas comprise a major category in the world art collection. Contributions include pottery, paintings, jewelry, weavings, sculptures, basketry, carvings, and beadwork.[180] Because too many artists were posing as Native Americans and Alaska Natives[181] to profit from the cachet of Indigenous art in the United States, the U.S. passed the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990, requiring artists to prove that they were enrolled in a state or federally recognized tribe. To support the ongoing practice of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian arts and cultures in the United States,[182] the Ford Foundation, arts advocates, and American Indian tribes created an endowment seed fund and established a national Native Arts and Cultures Foundation in 2007.[183][184]

After the entry of the Spaniards, the process of spiritual conquest was favored, among other things, by the liturgical musical service to which the natives, whose musical gifts came to surprise the missionaries, were integrated. The musical gifts of the natives were of such magnitude that they soon learned the rules of counterpoint and polyphony and even the virtuous handling of the instruments. This helped to ensure that it was not necessary to bring more musicians from Spain, which significantly annoyed the clergy.[185]

The solution that was proposed was not to employ but a certain number of indigenous people in the musical service, not to teach them counterpoint, not to allow them to play certain instruments (brass breaths, for example, in Oaxaca, Mexico) and, finally, not to import more instruments so that the indigenous people would not have access to them. The latter was not an obstacle to the musical enjoyment of the natives, who experienced the making of instruments, particularly rubbed strings (violins and double basses) or plucked (third). It is there where we can find the origin of what is now called traditional music whose instruments have their tuning and a typical Western structure.[186]

Demography[edit]

The following table provides estimates for each country in the Americas of the populations of Indigenous people and those with partial Indigenous ancestry, each expressed as a percentage of the overall population. The total percentage obtained by adding both of these categories is also given.

Note: these categories are inconsistently defined and measured differently from country to country. Some figures are based on the results of population-wide genetic surveys while others are based on self-identification or observational estimation.

| Country | Indigenous | Ref. | Part Indigenous | Ref. | Combined total | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 89% | % | 89% | [187] | |||

| 1.8% | 3.6% | 5.4% | [188] | |||

| 7% | 83% | 90% | [189] | |||

| 1.1% | 1.8% | 2.9% | [190] | |||

| % | % | % | ||||

| ~0.4% | ~0% | ~0.4% | [191] | |||

| % | % | % | [192] | |||

| % | % | % | ||||

| 0.4% | [193] | 84% | [194][195] | 84.4% | ||

| % | % | % | ||||

| % | % | % | ||||

| 2% | % | % | [196] | |||

| 0.8% | 88% | 88.8% | ||||

| 2.38% | [197] | 27% | [198][199] | 29.38% | ||

| 20% | 68% | 88% | [200] | |||

| 0.4% | 12% | 12.4% | [201] | |||

| 10.9% | % | % | [202] | |||

| 9.5% | [203] | 50.3% | [203] | 59.8% | [203] | |

| 25% | 65% | 90% | [204] | |||

| % | % | % | ||||

| 10.5% | [205] | % | % | |||

| 1.7% | 95% | 96.7% | [206] | |||

| 25.8% | 60.2% | 86% | [207] | |||

| 2% | [208] | % | % | |||

| 0% | [209] | 2.4% | [210] | 2.4% | ||

| 2.7% | 51.6% | 54.3% | [211] |

History and status by continent and country[edit]

North America[edit]

Canada[edit]

Indigenous peoples in Canada (also known as Aboriginals)[213] are the indigenous peoples within the boundaries of Canada. They comprise the First Nations,[214] Inuit,[215] and Métis.[216] Although "Indian" is a term still commonly used in legal documents, the descriptors "Indian" and "Eskimo" have fallen into disuse in Canada, and most consider them to be pejorative.[213][217][218] "Aboriginal" as a collective noun[219] is a specific term of art used in some legal documents, including the Constitution Act, 1982, though in some circles that word is also falling into disfavour.[220][221]

Old Crow Flats and Bluefish Caves are some of the earliest known sites of human habitation in Canada. The Paleo-Indian Clovis, Plano, and Pre-Dorset cultures predate the current Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Projectile point tools, spears, pottery, bangles, chisels, and scrapers mark archaeological sites, thus distinguishing cultural periods, traditions, and lithic reduction styles.

The characteristics of Indigenous culture in Canada included permanent settlements,[222] agriculture,[223] civic and ceremonial architecture,[224] complex societal hierarchies, and trading networks.[225] Métis nations of mixed ancestry originated in the mid-17th century when First Nations and Inuit people married European fur traders, primarily the French.[226] The Inuit had more limited interaction with European settlers during that early period.[227] Various laws, treaties, and legislation have been enacted between European immigrants and First Nations across Canada. The Aboriginal right to self-government provides opportunity to manage historical, cultural, political, health care and economic control aspects within first people's communities.

As of the 2021 census, the Indigenous population totalled 1,807,250 people, or 5.0% of the national population, with 1,048,405 First Nations people, 624,220 Métis, and 70,540 Inuit.[228] 7.7% of the population under the age of 14 are of Indigenous descent.[229] There are over 600 recognized First Nations governments or bands with distinctive cultures, languages, art, and music.[230][231] National Indigenous Peoples Day recognizes the cultures and contributions of Indigenous peoples to the history of Canada.[232] First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples of all backgrounds have become prominent figures and have served as role models in the Indigenous community and help to shape the Canadian cultural identity.[233]Greenland[edit]

The Greenlandic Inuit (Kalaallisut: kalaallit, Tunumiisut: tunumiit, Inuktun: inughuit) are the Indigenous and most populous ethnic group in Greenland.[234] This means that Denmark has one officially recognized Indigenous group. the Inuit – the Greenlandic Inuit of Greenland and the Greenlandic people in Denmark (Inuit residing in Denmark).

Approximately 89 percent of Greenland's population of 57,695 is Greenlandic Inuit, or 51,349 people as of 2012[update].[235][236] Ethnographically, they consist of three major groups:

- the Kalaallit of west Greenland, who speak Kalaallisut

- the Tunumiit of Tunu (east Greenland), who speak Tunumiit oraasiat ("East Greenlandic")

- the Inughuit of north Greenland, who speak Inuktun ("Polar Inuit")

Mexico[edit]

The territory of modern-day Mexico was home to numerous Indigenous civilizations before the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores: The Olmecs, who flourished from between 1200 BCE to about 400 BCE in the coastal regions of the Gulf of Mexico; the Zapotecs and the Mixtecs, who held sway in the mountains of Oaxaca and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec; the Maya in the Yucatán (and into neighboring areas of contemporary Central America); the Purépecha in present-day Michoacán and surrounding areas, and the Aztecs/Mexica, who, from their central capital at Tenochtitlan, dominated much of the center and south of the country (and the non-Aztec inhabitants of those areas) when Hernán Cortés first landed at Veracruz.

In contrast to what was the general rule in the rest of North America, the history of the colony of New Spain was one of racial intermingling (mestizaje). Mestizos, which in Mexico designate people who do not identify culturally with any Indigenous grouping, quickly came to account for a majority of the colony's population. Today, Mestizos in Mexico of mixed indigenous and European ancestry (with a minor African contribution) are still a majority of the population. Genetic studies vary over whether indigenous or European ancestry predominates in the Mexican Mestizo population.[237][238] In the 2020 INEGI census, 23.2 million people (19.4% of the Mexican population aged 3 years and older) self-identified as indigenous.[2] Somewhat contradictorily, in the same 2020 census, 11.8 million people (9.3% of the Mexican population) were determined to be indigenous by the Mexican government based on the language spoken in their households.[1] The indigenous population is distributed throughout the territory of Mexico but is especially concentrated in the Sierra Madre del Sur, the Yucatán Peninsula, and the most remote and difficult-to-access areas, such as the Sierra Madre Oriental, the Sierra Madre Occidental, and neighboring areas.[239] The CDI identifies 62 Indigenous groups in Mexico, each with a unique language.[240][241]

In the states of Chiapas and Oaxaca and the interior of the Yucatán Peninsula, a large amount of the population is of Indigenous descent with the largest ethnic group being Mayan with a population of 900,000.[242] Large Indigenous minorities, including Aztecs or Nahua, Purépechas, Mazahua, Otomi, and Mixtecs are also present in the central regions of Mexico. In the Northern and Bajio regions of Mexico, Indigenous people are a small minority.

The General Law of Linguistic Rights of the Indigenous Peoples grants all Indigenous languages spoken in Mexico, regardless of the number of speakers, the same validity as Spanish in all territories in which they are spoken, and Indigenous peoples are entitled to request some public services and documents in their native languages.[243] Along with Spanish, the law has granted them—more than 60 languages—the status of "national languages". The law includes all Indigenous languages of the Americas regardless of origin; that is, it includes the Indigenous languages of ethnic groups non-native to the territory. The National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples recognizes the language of the Kickapoo, who immigrated from the United States[244] and recognizes the languages of the Indigenous refugees from Guatemala.[245] The Mexican government has promoted and established bilingual primary and secondary education in some Indigenous rural communities. Nonetheless, of the Indigenous peoples in Mexico, 93% are either native speakers or bilingual second-language speakers of Spanish with only about 62.4% of them (or 5.4% of the country's population) speaking an Indigenous language and about a sixth do not speak Spanish (0.7% of the country's population).[246]

The Indigenous peoples in Mexico have the right of free determination under the second article of the constitution. According to this article, the Indigenous peoples are granted:[247]

- the right to decide the internal forms of social, economic, political, and cultural organization;

- the right to apply their normative systems of regulation as long as human rights and gender equality are respected;

- the right to preserve and enrich their languages and cultures;

- the right to elect representatives before the municipal council in which their territories are located;

amongst other rights.

United States[edit]

Indigenous peoples in what is now the contiguous United States, including their descendants, were commonly called American Indians, or simply Indians domestically and since the late 20th century the term Native American came into common use. In Alaska, Indigenous peoples belong to 11 cultures with 11 languages. These include the St. Lawrence Island Yupik, Iñupiat, Athabaskan, Yup'ik, Cup'ik, Unangax, Alutiiq, Eyak, Haida, Tsimshian, and Tlingit,[248] and are collectively called Alaska Natives. They include Native American peoples as well as Inuit, who are distinct but occupy areas of the region.

The United States has authority over Indigenous Polynesian people, which include Hawaiians, Marshallese (Micronesian), and Samoan; politically they are classified as Pacific Islander Americans. They are geographically, genetically, and culturally distinct from Indigenous peoples of the mainland continents of the Americas.

In the 2020 census 2.9% of the U.S. population claimed to have some degree of Native American heritage. When answering a question about racial background, 3.7 million people identified solely as "American Indian or Alaska Native", while another 5.9 million did so in combination with other races.[3] Aztecs were the largest single Native American group in the 2020 census, while Cherokee was the largest group in combination with any other race.[249] Tribes have established their criteria for membership, which are often based on blood quantum, lineal descent, or residency. A minority of Native Americans live in land units called Indian reservations.

Some California and Southwestern tribes, such as the Kumeyaay, Cocopa, Pascua Yaqui, Tohono O'odham, and Apache, span both sides of the US–Mexican border. By treaty, Haudenosaunee people have the legal right to freely cross the US–Canada border. Athabascan, Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Iñupiat, Blackfeet, Nakota, Cree, Anishinaabe, Huron, Lenape, Mi'kmaq, Penobscot, and Haudenosaunee, among others, live in both Canada and the United States, whose international border cut through their common cultural territory.

Central America[edit]

Belize[edit]

Mestizos (mixed European-Indigenous) number about 34% of the population; unmixed Maya make up another 10.6% (Kekchi, Mopan, and Yucatec). The Garifuna, who came to Belize in the 19th century from Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, have mixed African, Carib, and Arawak ancestry and make up another 6% of the population.[250]

Costa Rica[edit]

There are over 114,000 inhabitants of Native American origins, representing 2.4% of the population. Most of them live in secluded reservations, distributed among eight ethnic groups: Quitirrisí (In the Central Valley), Matambú or Chorotega (Guanacaste), Maleku (Northern Alajuela), Bribri (Southern Atlantic), Cabécar (Cordillera de Talamanca), Boruca (Southern Costa Rica) and Ngäbe (Southern Costa Rica long the Panamá border).

These native groups are characterized by their work in wood, like masks, drums, and other artistic figures, as well as fabrics made of cotton.

Their subsistence is based on agriculture, having corn, beans, and plantains as the main crops.[citation needed]

El Salvador[edit]

Estimates for El Salvador's indigenous population vary. The last time a reported census had an Indigenous ethnic option was in 2007, which estimated that 0.23% of the population identified as Indigenous.[26] Historically, estimates have claimed higher amounts. A 1930 census stated that 5.6% were Indigenous.[251] By the mid-20th century, there may have been as much as 20% (or 400,000) that would qualify as "Indigenous". Another estimate stated that by the late 1980s, 10% of the population was Indigenous, and another 89% was mestizo (or people of mixed European and Indigenous ancestry).[252]

Much of El Salvador was home to the Pipil, the Lenca, Xinca, and Kakawira. The Pipil lived in western El Salvador, spoke Nawat, and had many settlements there, most noticeably Cuzcatlan. The Pipil had no precious mineral resources, but they did have rich and fertile land that was good for farming. The Spaniards were disappointed not to find gold or jewels in El Salvador as they had in other lands like Guatemala or Mexico, but upon learning of the fertile land in El Salvador, they attempted to conquer it. Noted Meso-American Indigenous warriors to rise militarily against the Spanish included Princes Atonal and Atlacatl of the Pipil people in central El Salvador and Princess Antu Silan Ulap of the Lenca people in eastern El Salvador, who saw the Spanish not as gods but as barbaric invaders. After fierce battles, the Pipil successfully fought off the Spanish army led by Pedro de Alvarado along with their Indigenous allies (the Tlaxcalas), sending them back to Guatemala. After many other attacks with an army reinforced with Indigenous allies, the Spanish were able to conquer Cuzcatlan. After further attacks, the Spanish also conquered the Lenca people. Eventually, the Spaniards intermarried with Pipil and Lenca women, resulting in the mestizo population that would make up the vast majority of the Salvadoran people. Today many Pipil and other Indigenous populations live in the many small towns of El Salvador like Izalco, Panchimalco, Sacacoyo, and Nahuizalco.

Guatemala[edit]

Guatemala has one of the largest Indigenous populations in Central America, with approximately 43.6% of the population considering themselves Indigenous.[253] The Indigenous demographic portion of Guatemala's population consists of a majority of Mayan groups and one non-Mayan group. The Mayan language-speaking portion makes up 29.7% of the population and is distributed into 23 groups namely Q'eqchi' 8.3%, K'iche 7.8%, Mam 4.4%, Kaqchikel 3%, Q'anjob'al 1.2%, Poqomchi' 1%, and Other 4%.[253] The Non-Mayan group consists of the Xinca who are another set of Indigenous people making up 1.8% of the population.[253] Other sources indicate that between 50% and 60% of the population could be Indigenous because part of the Mestizo population is predominantly Indigenous.

The Mayan tribes cover a vast geographic area throughout Central America and expand beyond Guatemala into other countries. One could find vast groups of Mayan people in Boca Costa, in the Southern portions of Guatemala, as well as the Western Highlands living together in close communities.[254] Within these communities and outside of them, around 23 Indigenous languages (or Native American Indigenous languages) are spoken as a first language. Of these 23 languages, they only received official recognition by the Government in 2003 under the Law of National Languages.[253] The Law on National Languages recognizes 23 Indigenous languages including Xinca, enforcing that public and government institutions not only translate but also provide services in said languages.[255] It would provide services in Cakchiquel, Garifuna, Kekchi, Mam, Quiche, and Xinca.[256]

The Law of National Languages has been an effort to grant and protect Indigenous people rights not afforded to them previously. Along with the Law of National Languages passed in 2003, in 1996 the Guatemalan Constitutional Court had ratified the ILO Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples.[257] The ILO Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, is also known as Convention 169. Which is the only International Law regarding Indigenous peoples that Independent countries can adopt. The convention establishes that governments like Guatemala must consult with Indigenous groups before any projects occur on tribal lands.[258]

Honduras[edit]

About 5 percent of the population is of full-blooded Indigenous descent, but as much as 80 percent of Hondurans are mestizo or part-Indigenous with European admixture, and about 10 percent are of Indigenous or African descent.[259] The largest concentrations of Indigenous communities in Honduras are in the westernmost areas facing Guatemala and along the coast of the Caribbean Sea, as well as on the border with Nicaragua.[259] The majority of Indigenous people are Lencas, Miskitos to the east, Mayans, Pech, Sumos, and Tolupan.[259]

Nicaragua[edit]

About 5 percent of the Nicaraguan population is Indigenous. The largest Indigenous group in Nicaragua is the Miskito people. Their territory extended from Cabo Camarón, Honduras, to La Cruz de Rio Grande, Nicaragua along the Mosquito Coast. There is a native Miskito language, but large numbers speak Miskito Coast Creole, Spanish, Rama, and other languages. Their use of Creole English came about through frequent contact with the British, who colonized the area. Many Miskitos are Christians. Traditional Miskito society was highly structured, politically and otherwise. It had a king, but he did not have total power. Instead, the power was split between himself, a Miskito Governor, a Miskito General, and by the 1750s, a Miskito Admiral. Historical information on Miskito kings is often obscured by the fact that many of the kings were semi-mythical.

Another major Indigenous culture in eastern Nicaragua is the Mayangna (or Sumu) people, counting some 10,000 people.[260] A smaller Indigenous culture in southeastern Nicaragua is the Rama.

Other Indigenous groups in Nicaragua are located in the central, northern, and Pacific areas and they are self-identified as follows: Chorotega, Cacaopera (or Matagalpa), Xiu-Subtiaba, and Nicarao.[261]

Panama[edit]

Indigenous peoples of Panama, or Native Panamanians, are the native peoples of Panama. According to the 2010 census, they make up 12.3% of the overall population of 3.4 million, or just over 418,000 people. The Ngäbe and Buglé comprise half of the indigenous peoples of Panama.[262]

Many of the Indigenous Peoples live on comarca indígenas,[263] which are administrative regions for areas with substantial Indigenous populations. Three comarcas (Comarca Emberá-Wounaan, Guna Yala, Ngäbe-Buglé) exist as equivalent to a province, with two smaller comarcas (Guna de Madugandí and Guna de Wargandí) subordinate to a province and considered equivalent to a corregimiento (municipality).South America[edit]

Argentina[edit]

In 2005, the Indigenous population living in Argentina (known as pueblos originarios) numbered about 600,329 (1.6% of the total population); this figure includes 457,363 people who self-identified as belonging to an Indigenous ethnic group and 142,966 who identified themselves as first-generation descendants of an Indigenous people.[264] The ten most populous Indigenous peoples are the Mapuche (113,680 people), the Kolla (70,505), the Toba (69,452), the Guaraní (68,454), the Wichi (40,036), the Diaguita–Calchaquí (31,753), the Mocoví (15,837), the Huarpe (14,633), the Comechingón (10,863) and the Tehuelche (10,590). Minor but important peoples are the Quechua (6,739), the Charrúa (4,511), the Pilagá (4,465), the Chané (4,376), and the Chorote (2,613). The Selk'nam (Ona) people are now virtually extinct in its pure form. The languages of the Diaguita, Tehuelche, and Selk'nam nations have become extinct or virtually extinct: the Cacán language (spoken by Diaguitas) in the 18th century and the Selk'nam language in the 20th century; one Tehuelche language (Southern Tehuelche) is still spoken by a handful of elderly people.

Bolivia[edit]

This article's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (April 2012) |

In Bolivia, the 2012 National Census reported that 41% of residents over the age of 15 are of Indigenous origin. Some 3.7% report growing up with an Indigenous mother tongue but do not identify as Indigenous.[265] When both of these categories are totaled, and children under 15, some 66.4% of Bolivia's population was recorded as Indigenous in the 2001 Census.[266]

The 2021 National Census, recognizes 38 cultures, each with its language, as part of a pluri-national state. Some groups, including CONAMAQ (the National Council of Ayllus and Markas of Qullasuyu), draw ethnic boundaries within the Quechua- and Aymara-speaking population, resulting in a total of 50 Indigenous peoples native to Bolivia.

The largest Indigenous ethnic groups are Quechua, about 2.5 million people; Aymara, 2 million; Chiquitano, 181,000; Guaraní, 126,000; and Mojeño, 69,000. Some 124,000 belong to smaller Indigenous groups.[267] The Constitution of Bolivia, enacted in 2009, recognizes 36 cultures, each with its language, as part of a pluri-national state. Some groups, including CONAMAQ (the National Council of Ayllus and Markas of Qullasuyu), draw ethnic boundaries within the Quechua- and Aymara-speaking population, resulting in a total of 50 Indigenous peoples native to Bolivia.

Large numbers of Bolivian highland peasants retained Indigenous language, culture, customs, and communal organization throughout the Spanish conquest and the post-independence period. They mobilized to resist various attempts at the dissolution of communal landholdings and used legal recognition of "empowered caciques" to further communal organization. Indigenous revolts took place frequently until 1953.[268] While the National Revolutionary Movement government began in 1952 and discouraged people identifying as Indigenous (reclassifying rural people as campesinos, or peasants), renewed ethnic and class militancy re-emerged in the Katarista movement beginning in the 1970s.[269] Many lowland Indigenous peoples, mostly in the east, entered national politics through the 1990 March for Territory and Dignity organized by the CIDOB confederation. That march successfully pressured the national government to sign the ILO Convention 169 and to begin the still-ongoing process of recognizing and giving official titles to Indigenous territories. The 1994 Law of Popular Participation granted "grassroots territorial organizations;" these are recognized by the state and have certain rights to govern local areas.

Some radio and television programs are produced in the Quechua and Aymara languages. The constitutional reform in 1997 recognized Bolivia as a multi-lingual, pluri-ethnic society and introduced education reform. In 2005, for the first time in the country's history, an Indigenous Aymara, Evo Morales, was elected as president.

Morales began work on his "Indigenous autonomy" policy, which he launched in the eastern lowlands department on 3 August 2009. Bolivia was the first nation in the history of South America to affirm the right of Indigenous people to self-government.[270] Speaking in Santa Cruz Department, the President called it "a historic day for the peasant and Indigenous movement", saying that, though he might make errors, he would "never betray the fight started by our ancestors and the fight of the Bolivian people".[270] A vote on further autonomy for jurisdictions took place in December 2009, at the same time as general elections to office. The issue divided the country.[271]

At that time, Indigenous peoples voted overwhelmingly for more autonomy: five departments that had not already done so voted for it;[272][273] as did Gran Chaco Province in Taríja, for regional autonomy;[274] and 11 of 12 municipalities that had referendums on this issue.[272]

Brazil[edit]

Indigenous peoples of Brazil make up 0.4% of Brazil's population, or about 817,000 people, but millions of Brazilians are mestizo or have some Indigenous ancestry.[275] Indigenous peoples are found in the entire territory of Brazil, although in the 21st century, the majority of them live in Indigenous territories in the North and Center-Western parts of the country. On 18 January 2007, Fundação Nacional do Índio (FUNAI) reported that it had confirmed the presence of 67 different uncontacted tribes in Brazil, up from 40 in 2005. Brazil is now the nation that has the largest number of uncontacted tribes, and the island of New Guinea is second.[275]

The Washington Post reported in 2007, "As has been proved in the past when uncontacted tribes are introduced to other populations and the microbes they carry, maladies as simple as the common cold can be deadly. In the 1970s, 185 members of the Panara tribe died within two years of discovery after contracting such diseases as flu and chickenpox, leaving only 69 survivors."[276]

Chile[edit]

According to the 2012 Census, 10% of the Chilean population, including the Rapa Nui (a Polynesian people) of Easter Island, was Indigenous, although most show varying degrees of mixed heritage.[277] Many are descendants of the Mapuche and live in Santiago, Araucanía, and Los Lagos Region. The Mapuche successfully fought off defeat in the first 300–350 years of Spanish rule during the Arauco War. Relations with the new Chilean Republic were good until the Chilean state decided to occupy their lands. During the Occupation of Araucanía, the Mapuche surrendered to the country's army in the 1880s. Their land was opened to settlement by Chileans and Europeans. Conflict over Mapuche land rights continues to the present.

Other groups include the Aymara, the majority of whom live in Bolivia and Peru, with smaller numbers in the Arica-Parinacota and Tarapacá regions, and the Atacama people (Atacameños), who reside mainly in El Loa.

Colombia[edit]

A minority today within Colombia's mostly Mestizo and White Colombian population, Indigenous peoples living in Colombia, consist of around 85 distinct cultures and around 1,905,617 people, however, it is likely much higher.[278][279] A variety of collective rights for Indigenous peoples are recognized in the 1991 Constitution. One of the influences is the Muisca culture, a subset of the larger Chibcha ethnic group, famous for their use of gold, which led to the legend of El Dorado. At the time of the Spanish conquest, the Muisca were the largest Indigenous civilization geographically between the Inca and the Aztec empires.

Ecuador[edit]

Ecuador was the site of many Indigenous cultures, and civilizations of different proportions. An early sedentary culture, known as the Valdivia culture, developed in the coastal region, while the Caras and the Quitus unified to form an elaborate civilization that ended at the birth of the Capital Quito. The Cañaris near Cuenca were the most advanced, and most feared by the Inca, due to their fierce resistance to the Incan expansion. Their architectural remains were later destroyed by the Spaniards and the Incas.

Between 55% and 65% of Ecuador's population consists of Mestizos of mixed indigenous and European ancestry while indigenous people comprise about 25%.[280] Genetic analysis indicates that Ecuadorian Mestizos are of predominantly indigenous ancestry.[281] Approximately 96.4% of Ecuador's Indigenous population are Highland Quichuas living in the valleys of the Sierra region. Primarily consisting of the descendants of peoples conquered by the Incas, they are Kichwa speakers and include the Caranqui, the Otavalos, the Cayambe, the Quitu-Caras, the Panzaleo, the Chimbuelo, the Salasacan, the Tugua, the Puruhá, the Cañari, and the Saraguro. Linguistic evidence suggests that the Salascan and the Saraguro may have been the descendants of Bolivian ethnic groups transplanted to Ecuador as mitimaes.

Coastal groups, including the Awá, Chachi, and the Tsáchila, make up 0.24% percent of the Indigenous population, while the remaining 3.35 percent live in the Oriente and consist of the Oriente Kichwa (the Canelo and the Quijos), the Shuar, the Huaorani, the Siona-Secoya, the Cofán, and the Achuar.

In 1986, Indigenous peoples formed the first "truly" national political organization. The Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) has been the primary political institution of Indigenous peoples since then and is now the second-largest political party in the nation. It has been influential in national politics, contributing to the ouster of presidents Abdalá Bucaram in 1997 and Jamil Mahuad in 2000.

French Guiana[edit]

French Guiana is home to approximately 10,000 indigenous peoples, such as the Kalina and Lokono. Over time, the indigenous population has protested against various environmental issues, such as illegal gold mining, pollution, and a drastic decrease in wild game.

Guyana[edit]

During the early stages of colonization, the indigenous peoples in Guyana partook in trade relations with Dutch settlers and assisted in militia services such as hunting down escaped slaves for the British, which continued until the 19th century. Indigenous Guyanese people are responsible for the invention of the canoe as well as Guyanese pepperpot and the foundation of the Alleluia church.

Guyana's indigenous peoples have been recognized under the Constitution of 1965 and comprise 9.16% of the overall population.

Paraguay[edit]

The vast majority of indigenous peoples in Paraguay are concentrated in the Gran Chaco region in the northwest of the country, with the Guaraní making up the majority of the indigenous population in Paraguay. The Guaraní language is recognized as an official language alongside Spanish, with approximately 90% of the population speaking Guaraní. The indigenous population in Paraguay suffers from several social issues such as low literacy rates and inaccessibility to safe drinking water and electricity.

Peru[edit]

According to the 2017 Census, the Indigenous population in Peru makes up approximately 26%.[5] However, this does not include Mestizos of mixed indigenous and European descent, who make up the majority of the population. Genetic testing indicates that Peruvian Mestizos are of predominantly indigenous ancestry.[282] Indigenous traditions and customs have shaped the way Peruvians live and see themselves today. Cultural citizenship—or what Renato Rosaldo has called, "the right to be different and to belong, in a democratic, participatory sense" (1996:243)—is not yet very well developed in Peru. This is perhaps no more apparent than in the country's Amazonian regions where Indigenous societies continue to struggle against state-sponsored economic abuses, cultural discrimination, and pervasive violence.[283]

Suriname[edit]

According to the 2012 census, the indigenous population of Suriname numbers around 20,000, amounting to 3.8% of the population. The most numerous indigenous groups in Suriname primarily comprise the Lokono, Kalina, Tiriyó, and Wayana.

Uruguay[edit]

Unlike most other Spanish-speaking countries, indigenous peoples are not a significant element in Uruguay, as the entire indigenous population is virtually extinct, with a few exceptions such as the Guaraní. Approximately 2.4% of the population in Uruguay is reported to have indigenous ancestry.[210]

Venezuela[edit]

Most Venezuelans have some degree of indigenous heritage even if they may not identify as such. The 2011 census estimated that around 52% of the population identified as mestizo. But those who identify as Indigenous, from being raised in those cultures, make up only around 2% of the total population. The Indigenous peoples speak around 29 different languages and many more dialects. As some of the ethnic groups are very small, their native languages are in danger of becoming extinct in the next decades. The most important Indigenous groups are the Ye'kuana, the Wayuu, the Kali'na, the Ya̧nomamö, the Pemon, and the Warao. The most advanced Indigenous peoples to have lived within the boundaries of present-day Venezuela are thought to have been the Timoto-cuicas, who lived in the Venezuelan Andes. Historians estimate that there were between 350 thousand and 500 thousand Indigenous inhabitants at the time of Spanish colonization. The most densely populated area was the Andean region (Timoto-cuicas), thanks to their advanced agricultural techniques and ability to produce a surplus of food.

The 1999 constitution of Venezuela gives indigenous peoples special rights, although the vast majority of them still live in very critical conditions of poverty. The government provides primary education in their languages in public schools to some of the largest groups, in efforts to continue the languages.

Caribbean[edit]

The indigenous population of the Caribbean islands consisted of the Taíno of the Lucayan Archipelago, the Greater Antilles and the northern Lesser Antilles, the Kalinago of the Lesser Antilles, the Ciguayo and Macorix of parts of Hispaniola, and the Guanahatabey of western Cuba. The overall population suffered the most adverse colonial effects out of all the indigenous populations in the Americas, as the Kalinago have been reduced to a few islands in the Lesser Antilles such as Dominica and the Taíno are culturally extinct, though a large proportion of populations in Greater Antillean islands such as Puerto Rico, and Cuba to a lesser extent,[284] possesses degrees of Taíno ancestry. The Cayman Islands were the only island group in the Caribbean to have remained unsettled by indigenous peoples before the era of colonialism.[285]

Asia[edit]

Philippines[edit]

Historically, during the Spanish colonization of the Philippines, the territory was ruled as a province of the Mexico-centered Viceroyalty of New Spain and thus many Mexicans including those of indgenous Aztec and Tlaxcalan descent were sent as colonists there.[286]: Chpt. 6 According to a genetic study by the National Geographic around 2% of the Philippine population are Native American in descent.[287][288]

Rise of Indigenous movements[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Indigenous rights |

|---|

| Rights |

| Governmental organizations |

| NGOs and political groups |

| Issues |

| Legal representation |

| Countries |

| Category |

Since the late 20th century, Indigenous peoples in the Americas have become more politically active in asserting their treaty rights and expanding their influence. Some have organized to achieve some sort of self-determination and preservation of their cultures. Organizations such as the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon River Basin and the Indian Council of South America are examples of movements that are overcoming national borders to reunite Indigenous populations, for instance, those across the Amazon Basin. Similar movements for Indigenous rights can also be seen in Canada and the United States, with movements like the International Indian Treaty Council and the accession of native Indigenous groups into the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization.

There has been a recognition of Indigenous movements on an international scale. The membership of the United Nations voted to adopt the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, despite dissent from some of the stronger countries of the Americas.

In Colombia, various Indigenous groups have protested the denial of their rights. People organized a march in Cali in October 2008 to demand the government live up to promises to protect Indigenous lands, defend the Indigenous against violence, and reconsider the free trade pact with the United States.[289]

Indigenous heads of state[edit]