Закон

| Часть серии о |

| Закон |

|---|

|

| Основы и философия |

| Правовая теория |

| Методологическая основа |

| Юридические дебаты |

Закон – это набор правил, которые создаются и применяются социальными или государственными институтами для регулирования поведения. [ 1 ] его точное определение является предметом давних дискуссий. [ 2 ] [ 3 ] [ 4 ] Ее по-разному описывали как науку. [ 5 ] [ 6 ] и как искусство правосудия. [ 7 ] [ 8 ] [ 9 ] Законы, исполняемые государством, могут приниматься групповым законодательным органом или одним законодателем, что приводит к принятию статутов ; исполнительной властью посредством указов и постановлений ; или установлены судьями на основании прецедента , обычно в общего права юрисдикциях . Частные лица могут заключать юридически обязательные контракты , в том числе арбитражные соглашения, которые предусматривают способы разрешения споров, альтернативные стандартному судебному разбирательству. На создание самих законов может влиять конституция , писаная или подразумеваемая, а также заложенные в ней права . Закон по-разному формирует политику , экономику , историю и общество , а также служит посредником в отношениях между людьми.

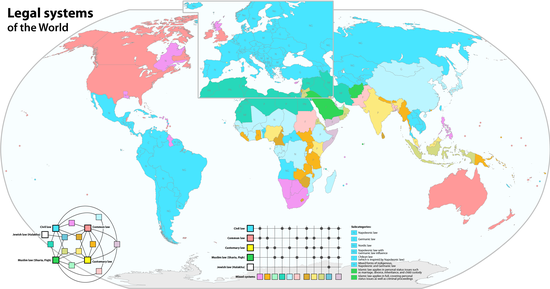

Legal systems vary between jurisdictions, with their differences analysed in comparative law. In civil law jurisdictions, a legislature or other central body codifies and consolidates the law. In common law systems, judges may make binding case law through precedent,[10] although on occasion this may be overturned by a higher court or the legislature.[11] Historically, religious law has influenced secular matters and is, as of the 21st century, still in use in some religious communities.[12][13][14] Sharia law based on Islamic principles is used as the primary legal system in several countries, including Iran and Saudi Arabia.[15][16]

The scope of law can be divided into two domains: public law concerns government and society, including constitutional law, administrative law, and criminal law; while private law deals with legal disputes between parties in areas such as contracts, property, torts, delicts and commercial law.[17] This distinction is stronger in civil law countries, particularly those with a separate system of administrative courts;[18][19] by contrast, the public-private law divide is less pronounced in common law jurisdictions.[20][21]

Law provides a source of scholarly inquiry into legal history,[22] philosophy,[23] economic analysis[24] and sociology.[25] Law also raises important and complex issues concerning equality, fairness, and justice.[26][27]

Etymology

The word law, attested in Old English as lagu, comes from the Old Norse word lǫg. The singular form lag meant 'something laid or fixed' while its plural meant 'law'.[28]

Philosophy of law

But what, after all, is a law? [...] When I say that the object of laws is always general, I mean that law considers subjects en masse and actions in the abstract, and never a particular person or action. [...] On this view, we at once see that it can no longer be asked whose business it is to make laws, since they are acts of the general will; nor whether the prince is above the law, since he is a member of the State; nor whether the law can be unjust, since no one is unjust to himself; nor how we can be both free and subject to the laws, since they are but registers of our wills.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract, II, 6.[29]

The philosophy of law is commonly known as jurisprudence. Normative jurisprudence asks "what should law be?", while analytic jurisprudence asks "what is law?"

Analytical jurisprudence

There have been several attempts to produce "a universally acceptable definition of law". In 1972, Baron Hampstead suggested that no such definition could be produced.[30] McCoubrey and White said that the question "what is law?" has no simple answer.[31] Glanville Williams said that the meaning of the word "law" depends on the context in which that word is used. He said that, for example, "early customary law" and "municipal law" were contexts where the word "law" had two different and irreconcilable meanings.[32] Thurman Arnold said that it is obvious that it is impossible to define the word "law" and that it is also equally obvious that the struggle to define that word should not ever be abandoned.[33] It is possible to take the view that there is no need to define the word "law" (e.g. "let's forget about generalities and get down to cases").[34]

One definition is that law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social institutions to govern behaviour.[1] In The Concept of Law, H. L. A. Hart argued that law is a "system of rules";[35] John Austin said law was "the command of a sovereign, backed by the threat of a sanction";[36] Ronald Dworkin describes law as an "interpretive concept" to achieve justice in his text titled Law's Empire;[37] and Joseph Raz argues law is an "authority" to mediate people's interests.[38] Oliver Wendell Holmes defined law as "the prophecies of what the courts will do in fact, and nothing more pretentious."[39] In his Treatise on Law, Thomas Aquinas argues that law is a rational ordering of things, which concern the common good, that is promulgated by whoever is charged with the care of the community.[40] This definition has both positivist and naturalist elements.[41]

Connection to morality and justice

Definitions of law often raise the question of the extent to which law incorporates morality.[42] John Austin's utilitarian answer was that law is "commands, backed by threat of sanctions, from a sovereign, to whom people have a habit of obedience".[36] Natural lawyers, on the other hand, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, argue that law reflects essentially moral and unchangeable laws of nature. The concept of "natural law" emerged in ancient Greek philosophy concurrently and in connection with the notion of justice, and re-entered the mainstream of Western culture through the writings of Thomas Aquinas, notably his Treatise on Law.

Hugo Grotius, the founder of a purely rationalistic system of natural law, argued that law arises from both a social impulse—as Aristotle had indicated—and reason.[43] Immanuel Kant believed a moral imperative requires laws "be chosen as though they should hold as universal laws of nature".[44] Jeremy Bentham and his student Austin, following David Hume, believed that this conflated the "is" and what "ought to be" problem. Bentham and Austin argued for law's positivism; that real law is entirely separate from "morality".[45] Kant was also criticised by Friedrich Nietzsche, who rejected the principle of equality, and believed that law emanates from the will to power, and cannot be labeled as "moral" or "immoral".[46][47][48]

In 1934, the Austrian philosopher Hans Kelsen continued the positivist tradition in his book the Pure Theory of Law.[49] Kelsen believed that although law is separate from morality, it is endowed with "normativity", meaning we ought to obey it. While laws are positive "is" statements (e.g. the fine for reversing on a highway is €500); law tells us what we "should" do. Thus, each legal system can be hypothesised to have a 'basic norm' (German: Grundnorm) instructing us to obey. Kelsen's major opponent, Carl Schmitt, rejected both positivism and the idea of the rule of law because he did not accept the primacy of abstract normative principles over concrete political positions and decisions.[50] Therefore, Schmitt advocated a jurisprudence of the exception (state of emergency), which denied that legal norms could encompass all of the political experience.[51]

Later in the 20th century, H. L. A. Hart attacked Austin for his simplifications and Kelsen for his fictions in The Concept of Law.[52] Hart argued law is a system of rules, divided into primary (rules of conduct) and secondary ones (rules addressed to officials to administer primary rules). Secondary rules are further divided into rules of adjudication (to resolve legal disputes), rules of change (allowing laws to be varied) and the rule of recognition (allowing laws to be identified as valid). Two of Hart's students continued the debate: In his book Law's Empire, Ronald Dworkin attacked Hart and the positivists for their refusal to treat law as a moral issue. Dworkin argues that law is an "interpretive concept"[37] that requires judges to find the best fitting and most just solution to a legal dispute, given their Anglo-American constitutional traditions. Joseph Raz, on the other hand, defended the positivist outlook and criticised Hart's "soft social thesis" approach in The Authority of Law.[38] Raz argues that law is authority, identifiable purely through social sources and without reference to moral reasoning. In his view, any categorisation of rules beyond their role as authoritative instruments in mediation are best left to sociology, rather than jurisprudence.[53]

History

The history of law links closely to the development of civilization. Ancient Egyptian law, dating as far back as 3000 BC, was based on the concept of Ma'at and characterised by tradition, rhetorical speech, social equality and impartiality.[54][55][56] By the 22nd century BC, the ancient Sumerian ruler Ur-Nammu had formulated the first law code, which consisted of casuistic statements ("if … then ..."). Around 1760 BC, King Hammurabi further developed Babylonian law, by codifying and inscribing it in stone. Hammurabi placed several copies of his law code throughout the kingdom of Babylon as stelae, for the entire public to see; this became known as the Codex Hammurabi. The most intact copy of these stelae was discovered in the 19th century by British Assyriologists, and has since been fully transliterated and translated into various languages, including English, Italian, German, and French.[57]

The Old Testament dates back to 1280 BC and takes the form of moral imperatives as recommendations for a good society. The small Greek city-state, ancient Athens, from about the 8th century BC was the first society to be based on broad inclusion of its citizenry, excluding women and enslaved people. However, Athens had no legal science or single word for "law",[58] relying instead on the three-way distinction between divine law (thémis), human decree (nomos) and custom (díkē).[59] Yet Ancient Greek law contained major constitutional innovations in the development of democracy.[60]

Roman law was heavily influenced by Greek philosophy, but its detailed rules were developed by professional jurists and were highly sophisticated.[61][62] Over the centuries between the rise and decline of the Roman Empire, law was adapted to cope with the changing social situations and underwent major codification under Theodosius II and Justinian I.[a] Although codes were replaced by custom and case law during the Early Middle Ages, Roman law was rediscovered around the 11th century when medieval legal scholars began to research Roman codes and adapt their concepts to the canon law, giving birth to the jus commune. Latin legal maxims (called brocards) were compiled for guidance. In medieval England, royal courts developed a body of precedent which later became the common law. A Europe-wide Law Merchant was formed so that merchants could trade with common standards of practice rather than with the many splintered facets of local laws. The Law Merchant, a precursor to modern commercial law, emphasised the freedom to contract and alienability of property.[63] As nationalism grew in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Law Merchant was incorporated into countries' local law under new civil codes. The Napoleonic and German Codes became the most influential. In contrast to English common law, which consists of enormous tomes of case law, codes in small books are easy to export and easy for judges to apply. However, today there are signs that civil and common law are converging.[64] EU law is codified in treaties, but develops through de facto precedent laid down by the European Court of Justice.[65]

Ancient India and China represent distinct traditions of law, and have historically had independent schools of legal theory and practice. The Arthashastra, probably compiled around 100 AD (although it contains older material), and the Manusmriti (c. 100–300 AD) were foundational treatises in India, and comprise texts considered authoritative legal guidance.[66] Manu's central philosophy was tolerance and pluralism, and was cited across Southeast Asia.[67] During the Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent, sharia was established by the Muslim sultanates and empires, most notably Mughal Empire's Fatawa-e-Alamgiri, compiled by emperor Aurangzeb and various scholars of Islam.[68][69] In India, the Hindu legal tradition, along with Islamic law, were both supplanted by common law when India became part of the British Empire.[70] Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore and Hong Kong also adopted the common law system. The eastern Asia legal tradition reflects a unique blend of secular and religious influences.[71] Japan was the first country to begin modernising its legal system along western lines, by importing parts of the French, but mostly the German Civil Code.[72] This partly reflected Germany's status as a rising power in the late 19th century.

Similarly, traditional Chinese law gave way to westernisation towards the final years of the Qing Dynasty in the form of six private law codes based mainly on the Japanese model of German law.[73] Today Taiwanese law retains the closest affinity to the codifications from that period, because of the split between Chiang Kai-shek's nationalists, who fled there, and Mao Zedong's communists who won control of the mainland in 1949. The current legal infrastructure in the People's Republic of China was heavily influenced by Soviet Socialist law, which essentially prioritises administrative law at the expense of private law rights.[74] Due to rapid industrialisation, today China is undergoing a process of reform, at least in terms of economic, if not social and political, rights. A new contract code in 1999 represented a move away from administrative domination.[75] Furthermore, after negotiations lasting fifteen years, in 2001 China joined the World Trade Organization.[76]

Legal systems

In general, legal systems can be split between civil law and common law systems.[77] Modern scholars argue that the significance of this distinction has progressively declined. The numerous legal transplants, typical of modern law, result in the sharing of many features traditionally considered typical of either common law or civil law.[64][78] The third type of legal system is religious law, based on scriptures. The specific system that a country is ruled by is often determined by its history, connections with other countries, or its adherence to international standards. The sources that jurisdictions adopt as authoritatively binding are the defining features of any legal system.

Civil law

Civil law is the legal system used in most countries around the world today. In civil law the sources recognised as authoritative are, primarily, legislation—especially codifications in constitutions or statutes passed by government—and custom.[b] Codifications date back millennia, with one early example being the Babylonian Codex Hammurabi. Modern civil law systems essentially derive from legal codes issued by Byzantine Emperor Justinian I in the 6th century, which were rediscovered by 11th century Italy.[80] Roman law in the days of the Roman Republic and Empire was heavily procedural, and lacked a professional legal class.[81] Instead a lay magistrate, iudex, was chosen to adjudicate. Decisions were not published in any systematic way, so any case law that developed was disguised and almost unrecognised.[82] Each case was to be decided afresh from the laws of the State, which mirrors the (theoretical) unimportance of judges' decisions for future cases in civil law systems today. From 529 to 534 AD the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I codified and consolidated Roman law up until that point, so that what remained was one-twentieth of the mass of legal texts from before.[83] This became known as the Corpus Juris Civilis. As one legal historian wrote, "Justinian consciously looked back to the golden age of Roman law and aimed to restore it to the peak it had reached three centuries before."[84] The Justinian Code remained in force in the East until the fall of the Byzantine Empire. Western Europe, meanwhile, relied on a mix of the Theodosian Code and Germanic customary law until the Justinian Code was rediscovered in the 11th century, which scholars at the University of Bologna used to interpret their own laws.[85] Civil law codifications based closely on Roman law, alongside some influences from religious laws such as canon law, continued to spread throughout Europe until the Enlightenment. Then, in the 19th century, both France, with the Code Civil, and Germany, with the Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, modernised their legal codes. Both these codes heavily influenced not only the law systems of the countries in continental Europe, but also the Japanese and Korean legal traditions.[86][87] Today, countries that have civil law systems range from Russia and Turkey to most of Central and Latin America.[88]

Anarchist and socialist law

Anarchist law primarily deals with how anarchism is implemented upon a society, the framework based on decentralized organizations and mutual aid, with representation through a form of direct democracy. Laws being based upon their need.[89] A large portion of anarchist ideologies such as anarcho-syndicalism and anarcho-communism primarily focuses on decentralized worker unions, cooperatives and syndicates as the main instrument of society.[90]

Socialist law is the legal systems in communist states such as the former Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China.[91] Academic opinion is divided on whether it is a separate system from civil law, given major deviations based on Marxist–Leninist ideology, such as subordinating the judiciary to the executive ruling party.[91][92][93]

Common law and equity

In common law legal systems, decisions by courts are explicitly acknowledged as "law" on equal footing with legislative statutes and executive regulations. The "doctrine of precedent", or stare decisis (Latin for "to stand by decisions") means that decisions by higher courts bind lower courts to assure that similar cases reach similar results. In contrast, in civil law systems, legislative statutes are typically more detailed, and judicial decisions are shorter and less detailed, because the adjudicator is only writing to decide the single case, rather than to set out reasoning that will guide future courts.

Common law originated from England and has been inherited by almost every country once tied to the British Empire (except Malta, Scotland, the U.S. state of Louisiana, and the Canadian province of Quebec). In medieval England during the Norman conquest, the law varied shire-to-shire based on disparate tribal customs. The concept of a "common law" developed during the reign of Henry II during the late 12th century, when Henry appointed judges that had authority to create an institutionalised and unified system of law common to the country. The next major step in the evolution of the common law came when King John was forced by his barons to sign a document limiting his authority to pass laws. This "great charter" or Magna Carta of 1215 also required that the King's entourage of judges hold their courts and judgments at "a certain place" rather than dispensing autocratic justice in unpredictable places about the country.[94] A concentrated and elite group of judges acquired a dominant role in law-making under this system, and compared to its European counterparts the English judiciary became highly centralised. In 1297, for instance, while the highest court in France had fifty-one judges, the English Court of Common Pleas had five.[95] This powerful and tight-knit judiciary gave rise to a systematised process of developing common law.[96]

As time went on, many felt that the common law was overly systematised and inflexible, and increasing numbers of citizens petitioned the King to override the common law. On the King's behalf, the Lord Chancellor started giving judgments to do what was equitable in a case. From the time of Sir Thomas More, the first lawyer to be appointed as Lord Chancellor, a systematic body of equity grew up alongside the rigid common law, and developed its own Court of Chancery. At first, equity was often criticised as erratic.[97] Over time, courts of equity developed solid principles, especially under Lord Eldon.[98] In the 19th century in England, and in 1937 in the U.S., the two systems were merged.

In developing the common law, academic writings have always played an important part, both to collect overarching principles from dispersed case law, and to argue for change. William Blackstone, from around 1760, was the first scholar to collect, describe, and teach the common law.[99] But merely in describing, scholars who sought explanations and underlying structures slowly changed the way the law actually worked.[100]

Religious law

Religious law is explicitly based on religious precepts. Examples include the Jewish Halakha and Islamic Sharia—both of which translate as the "path to follow". Christian canon law also survives in some church communities. Often the implication of religion for law is unalterability, because the word of God cannot be amended or legislated against by judges or governments.[101] Nonetheless, most religious jurisdictions rely on further human elaboration to provide for thorough and detailed legal systems. For instance, the Quran has some law, and it acts as a source of further law through interpretation, Qiyas (reasoning by analogy), Ijma (consensus) and precedent.[102] This is mainly contained in a body of law and jurisprudence known as Sharia and Fiqh respectively. Another example is the Torah or Old Testament, in the Pentateuch or Five Books of Moses. This contains the basic code of Jewish law, which some Israeli communities choose to use. The Halakha is a code of Jewish law that summarizes some of the Talmud's interpretations.

A number of countries are sharia jurisdictions. Israeli law allows litigants to use religious laws only if they choose. Canon law is only in use by members of the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Anglican Communion.

Canon law

Canon law (Ancient Greek: κανών, romanized: kanon, lit. 'a straight measuring rod; a ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority, for the government of a Christian organisation or church and its members. It is the internal ecclesiastical law governing the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, and the individual national churches within the Anglican Communion.[103] The way that such church law is legislated, interpreted and at times adjudicated varies widely among these three bodies of churches. In all three traditions, a canon was originally[104] a rule adopted by a church council; these canons formed the foundation of canon law.

The Catholic Church has the oldest continuously functioning legal system in the western world,[105][106] predating the evolution of modern European civil law and common law systems. The 1983 Code of Canon Law governs the Latin Church sui juris. The Eastern Catholic Churches, which developed different disciplines and practices, are governed by the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches.[107] The canon law of the Catholic Church influenced the common law during the medieval period through its preservation of Roman law doctrine such as the presumption of innocence.[108][c]

Sharia law

Until the 18th century, Sharia law was practiced throughout the Muslim world in a non-codified form, with the Ottoman Empire's Mecelle code in the 19th century being a first attempt at codifying elements of Sharia law. Since the mid-1940s, efforts have been made, in country after country, to bring Sharia law more into line with modern conditions and conceptions.[110][111] In modern times, the legal systems of many Muslim countries draw upon both civil and common law traditions as well as Islamic law and custom. The constitutions of certain Muslim states, such as Egypt and Afghanistan, recognise Islam as the religion of the state, obliging legislature to adhere to Sharia.[112] Saudi Arabia recognises the Quran as its constitution, and is governed on the basis of Islamic law.[113] Iran has also witnessed a reiteration of Islamic law into its legal system after 1979.[114] During the last few decades, one of the fundamental features of the movement of Islamic resurgence has been the call to restore the Sharia, which has generated a vast amount of literature and affected world politics.[115]

Legal methods

There are distinguished methods of legal reasoning (applying the law) and methods of interpreting (construing) the law. The former are legal syllogism, which holds sway in civil law legal systems, analogy, which is present in common law legal systems, especially in the US, and argumentative theories that occur in both systems. The latter are different rules (directives) of legal interpretation such as directives of linguistic interpretation, teleological interpretation or systemic interpretation as well as more specific rules, for instance, golden rule or mischief rule. There are also many other arguments and cannons of interpretation which altogether make statutory interpretation possible.

Law professor and former United States Attorney General Edward H. Levi noted that the "basic pattern of legal reasoning is reasoning by example"—that is, reasoning by comparing outcomes in cases resolving similar legal questions.[116] In a U.S. Supreme Court case regarding procedural efforts taken by a debt collection company to avoid errors, Justice Sotomayor cautioned that "legal reasoning is not a mechanical or strictly linear process".[117]

Jurimetrics is the formal application of quantitative methods, especially probability and statistics, to legal questions. The use of statistical methods in court cases and law review articles has grown massively in importance in the last few decades.[118][119]

Legal institutions

It is a real unity of them all in one and the same person, made by covenant of every man with every man, in such manner as if every man should say to every man: I authorise and give up my right of governing myself to this man, or to this assembly of men, on this condition; that thou givest up, thy right to him, and authorise all his actions in like manner.

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, XVII

The main institutions of law in industrialised countries are independent courts, representative parliaments, an accountable executive, the military and police, bureaucratic organisation, the legal profession and civil society itself. John Locke, in his Two Treatises of Government, and Baron de Montesquieu in The Spirit of the Laws, advocated for a separation of powers between the political, legislature and executive bodies.[120] Their principle was that no person should be able to usurp all powers of the state, in contrast to the absolutist theory of Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan.[121] Sun Yat-sen's Five Power Constitution for the Republic of China took the separation of powers further by having two additional branches of government—a Control Yuan for auditing oversight and an Examination Yuan to manage the employment of public officials.[122]

Max Weber and others reshaped thinking on the extension of state. Modern military, policing and bureaucratic power over ordinary citizens' daily lives pose special problems for accountability that earlier writers such as Locke or Montesquieu could not have foreseen. The custom and practice of the legal profession is an important part of people's access to justice, whilst civil society is a term used to refer to the social institutions, communities and partnerships that form law's political basis.

Judiciary

A judiciary is a number of judges mediating disputes to determine outcome. Most countries have systems of appeal courts, with an apex court as the ultimate judicial authority. In the United States, this authority is the Supreme Court;[123] in Australia, the High Court; in India, the Supreme Court of India; in the UK, the Supreme Court;[124] in Germany, the Bundesverfassungsgericht; and in France, the Cour de Cassation.[125][126] For most European countries the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg can overrule national law, when EU law is relevant. The European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg allows citizens of the Council of Europe member states to bring cases relating to human rights issues before it.[127]

Some countries allow their highest judicial authority to overrule legislation they determine to be unconstitutional. For example, in Brown v. Board of Education, the United States Supreme Court nullified many state statutes that had established racially segregated schools, finding such statutes to be incompatible with the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[128]

A judiciary is theoretically bound by the constitution, just as all other government bodies are. In most countries judges may only interpret the constitution and all other laws. But in common law countries, where matters are not constitutional, the judiciary may also create law under the doctrine of precedent. The UK, Finland and New Zealand assert the ideal of parliamentary sovereignty, whereby the unelected judiciary may not overturn law passed by a democratic legislature.[129]

In communist states, such as China, the courts are often regarded as parts of the executive, or subservient to the legislature; governmental institutions and actors exert thus various forms of influence on the judiciary.[d] In Muslim countries, courts often examine whether state laws adhere to the Sharia: the Supreme Constitutional Court of Egypt may invalidate such laws,[130] and in Iran the Guardian Council ensures the compatibility of the legislation with the "criteria of Islam".[130][131]

Legislature

Prominent examples of legislatures are the Houses of Parliament in London, the Congress in Washington, D.C., the Bundestag in Berlin, the Duma in Moscow, the Parlamento Italiano in Rome and the Assemblée nationale in Paris. By the principle of representative government people vote for politicians to carry out their wishes. Although countries like Israel, Greece, Sweden and China are unicameral, most countries are bicameral, meaning they have two separately appointed legislative houses.[132]

In the 'lower house' politicians are elected to represent smaller constituencies. The 'upper house' is usually elected to represent states in a federal system (as in Australia, Germany or the United States) or different voting configuration in a unitary system (as in France). In the UK the upper house is appointed by the government as a house of review. One criticism of bicameral systems with two elected chambers is that the upper and lower houses may simply mirror one another. The traditional justification of bicameralism is that an upper chamber acts as a house of review. This can minimise arbitrariness and injustice in governmental action.[132]

To pass legislation, a majority of the members of a legislature must vote for a bill (proposed law) in each house. Normally there will be several readings and amendments proposed by the different political factions. If a country has an entrenched constitution, a special majority for changes to the constitution may be required, making changes to the law more difficult. A government usually leads the process, which can be formed from Members of Parliament (e.g. the UK or Germany). However, in a presidential system, the government is usually formed by an executive and his or her appointed cabinet officials (e.g. the United States or Brazil).[e]

Executive

The executive in a legal system serves as the centre of political authority of the State. In a parliamentary system, as with Britain, Italy, Germany, India, and Japan, the executive is known as the cabinet, and composed of members of the legislature. The executive is led by the head of government, whose office holds power under the confidence of the legislature. Because popular elections appoint political parties to govern, the leader of a party can change in between elections.[133]

The head of state is apart from the executive, and symbolically enacts laws and acts as representative of the nation. Examples include the President of Germany (appointed by members of federal and state legislatures), the Queen of the United Kingdom (an hereditary office), and the President of Austria (elected by popular vote). The other important model is the presidential system, found in the United States and in Brazil. In presidential systems, the executive acts as both head of state and head of government, and has power to appoint an unelected cabinet. Under a presidential system, the executive branch is separate from the legislature to which it is not accountable.[133][134]

Although the role of the executive varies from country to country, usually it will propose the majority of legislation, and propose government agenda. In presidential systems, the executive often has the power to veto legislation. Most executives in both systems are responsible for foreign relations, the military and police, and the bureaucracy. Ministers or other officials head a country's public offices, such as a foreign ministry or defence ministry. The election of a different executive is therefore capable of revolutionising an entire country's approach to government.

Military and police

While military organisations have existed as long as government itself, the idea of a standing police force is a relatively modern concept. For example, Medieval England's system of travelling criminal courts, or assizes, used show trials and public executions to instill communities with fear to maintain control.[135] The first modern police were probably those in 17th-century Paris, in the court of Louis XIV,[136] although the Paris Prefecture of Police claim they were the world's first uniformed policemen.[137]

Max Weber famously argued that the state is that which controls the monopoly on the legitimate use of force.[138][139] The military and police carry out enforcement at the request of the government or the courts. The term failed state refers to states that cannot implement or enforce policies; their police and military no longer control security and order and society moves into anarchy, the absence of government.[f]

Bureaucracy

The etymology of bureaucracy derives from the French word for office (bureau) and the Ancient Greek for word power (kratos).[140][better source needed] Like the military and police, a legal system's government servants and bodies that make up its bureaucracy carry out the directives of the executive. One of the earliest references to the concept was made by Baron de Grimm, a German author who lived in France. In 1765, he wrote:

The real spirit of the laws in France is that bureaucracy of which the late Monsieur de Gournay used to complain so greatly; here the offices, clerks, secretaries, inspectors and intendants are not appointed to benefit the public interest, indeed the public interest appears to have been established so that offices might exist.[141]

Cynicism over "officialdom" is still common, and the workings of public servants is typically contrasted to private enterprise motivated by profit.[142] In fact private companies, especially large ones, also have bureaucracies.[143] Negative perceptions of "red tape" aside, public services such as schooling, health care, policing or public transport are considered a crucial state function making public bureaucratic action the locus of government power.[143]

Writing in the early 20th century, Max Weber believed that a definitive feature of a developed state had come to be its bureaucratic support.[144] Weber wrote that the typical characteristics of modern bureaucracy are that officials define its mission, the scope of work is bound by rules, and management is composed of career experts who manage top down, communicating through writing and binding public servants' discretion with rules.[145]

Legal profession

A corollary of the rule of law is the existence of a legal profession sufficiently autonomous to invoke the authority of the independent judiciary; the right to assistance of a barrister in a court proceeding emanates from this corollary—in England the function of barrister or advocate is distinguished from legal counselor.[146] As the European Court of Human Rights has stated, the law should be adequately accessible to everyone and people should be able to foresee how the law affects them.[147]

In order to maintain professionalism, the practice of law is typically overseen by either a government or independent regulating body such as a bar association, bar council or law society. Modern lawyers achieve distinct professional identity through specified legal procedures (e.g. successfully passing a qualifying examination), are required by law to have a special qualification (a legal education earning the student a Bachelor of Laws, a Bachelor of Civil Law, or a Juris Doctor degree. Higher academic degrees may also be pursued. Examples include a Master of Laws, a Master of Legal Studies, a Bar Professional Training Course or a Doctor of Laws.), and are constituted in office by legal forms of appointment (being admitted to the bar). There are few titles of respect to signify famous lawyers, such as Esquire, to indicate barristers of greater dignity,[148][149] and Doctor of law, to indicate a person who obtained a PhD in Law.

Many Muslim countries have developed similar rules about legal education and the legal profession, but some still allow lawyers with training in traditional Islamic law to practice law before personal status law courts.[150] In China and other developing countries there are not sufficient professionally trained people to staff the existing judicial systems, and, accordingly, formal standards are more relaxed.[151]

Once accredited, a lawyer will often work in a law firm, in a chambers as a sole practitioner, in a government post or in a private corporation as an internal counsel. In addition a lawyer may become a legal researcher who provides on-demand legal research through a library, a commercial service or freelance work. Many people trained in law put their skills to use outside the legal field entirely.[152]

Significant to the practice of law in the common law tradition is the legal research to determine the current state of the law. This usually entails exploring case-law reports, legal periodicals and legislation. Law practice also involves drafting documents such as court pleadings, persuasive briefs, contracts, or wills and trusts. Negotiation and dispute resolution skills (including ADR techniques) are also important to legal practice, depending on the field.[152]

Civil society

The Classical republican concept of "civil society" dates back to Hobbes and Locke.[153] Locke saw civil society as people who have "a common established law and judicature to appeal to, with authority to decide controversies between them."[154] German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel distinguished the "state" from "civil society" (German: bürgerliche Gesellschaft) in Elements of the Philosophy of Right.[155][156]

Hegel believed that civil society and the state were polar opposites, within the scheme of his dialectic theory of history. The modern dipole state–civil society was reproduced in the theories of Alexis de Tocqueville and Karl Marx.[157][158] In post-modern theory, civil society is necessarily a source of law, by being the basis from which people form opinions and lobby for what they believe law should be. As Australian barrister and author Geoffrey Robertson QC wrote of international law, "one of its primary modern sources is found in the responses of ordinary men and women, and of the non-governmental organizations which many of them support, to the human rights abuses they see on the television screen in their living rooms."[159]

Freedom of speech, freedom of association and many other individual rights allow people to gather, discuss, criticise and hold to account their governments, from which the basis of a deliberative democracy is formed. The more people are involved with, concerned by and capable of changing how political power is exercised over their lives, the more acceptable and legitimate the law becomes to the people. The most familiar institutions of civil society include economic markets, profit-oriented firms, families, trade unions, hospitals, universities, schools, charities, debating clubs, non-governmental organisations, neighbourhoods, churches, and religious associations. There is no clear legal definition of the civil society, and of the institutions it includes. Most of the institutions and bodies who try to give a list of institutions (such as the European Economic and Social Committee) exclude the political parties.[160][161][162]

Areas of law

All legal systems deal with the same basic issues, but jurisdictions categorise and identify their legal topics in different ways. A common distinction is that between "public law" (a term related closely to the state, and including constitutional, administrative and criminal law), and "private law" (which covers contract, tort and property).[g] In civil law systems, contract and tort fall under a general law of obligations, while trusts law is dealt with under statutory regimes or international conventions. International, constitutional and administrative law, criminal law, contract, tort, property law and trusts are regarded as the "traditional core subjects",[h] although there are many further disciplines.

International law

International law can refer to three things: public international law, private international law or conflict of laws and the law of supranational organisations.

- Public international law concerns relationships between sovereign nations. The sources for public international law development are custom, practice and treaties between sovereign nations, such as the Geneva Conventions. Public international law can be formed by international organisations, such as the United Nations (which was established after the failure of the League of Nations to prevent World War II),[i] the International Labour Organisation, the World Trade Organisation (WTO), or the International Monetary Fund. Public international law has a special status as law because there is no international police force, and courts (e.g. the International Court of Justice as the primary UN judicial organ) lack the capacity to penalise disobedience. The prevailing manner of enforcing international law is still essentially "self help"; that is the reaction by states to alleged breaches of international obligations by other states.[164][1][165] However, a few bodies, such as the WTO, have effective systems of binding arbitration and dispute resolution backed up by trade sanctions.[166]

- Conflict of laws, or private international law in civil law countries, concerns which jurisdiction a legal dispute between private parties should be heard in and which jurisdiction's law should be applied. Today, businesses are increasingly capable of shifting capital and labour supply chains across borders, as well as trading with overseas businesses, making the question of which country has jurisdiction even more pressing. Increasing numbers of businesses opt for commercial arbitration under the New York Convention 1958.[167]

- European Union law is the first and so far the only example of a supranational law, i.e. an internationally accepted legal system, other than the United Nations and the World Trade Organization. Given the trend of increasing global economic integration, many regional agreements—especially the African Union—seek to follow a similar model.[168][169] In the EU, sovereign nations have gathered their authority in a system of courts and the European Parliament. These institutions are allowed the ability to enforce legal norms both against or for member states and citizens in a manner which is not possible through public international law.[170] As the European Court of Justice noted in its 1963 Van Gend en Loos decision, European Union law constitutes "a new legal order of international law" for the mutual social and economic benefit of the member states.[171][172][173]

Constitutional and administrative law

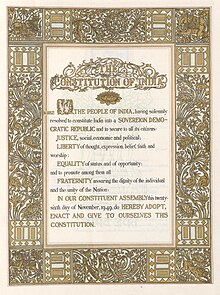

Constitutional and administrative law govern the affairs of the state. Constitutional law concerns both the relationships between the executive, legislature and judiciary and the human rights or civil liberties of individuals against the state. Most jurisdictions, like the United States and France, have a single codified constitution with a bill of rights. A few, like the United Kingdom, have no such document. A "constitution" is simply those laws which constitute the body politic, from statute, case law and convention.

The fundamental constitutional principle, inspired by John Locke, holds that the individual can do anything except that which is forbidden by law, and the state may do nothing except that which is authorised by law.[174][175] Administrative law is the chief method for people to hold state bodies to account. People (wheresoever allowed) may potentially have prerogative to legally challenge (or sue) an agency, local council, public service, or government ministry for judicial review of the offending edict (law, ordinance, policy order). Such challenge vets the ability of actionable authority under the law, and that the government entity observed required procedure. The first specialist administrative court was the Conseil d'État set up in 1799, as Napoleon assumed power in France.[176]

A sub-discipline of constitutional law is election law. It along with Elections commissions, councils, or committees deal with policy and procedures facilitating elections. These rules settle disputes or enable the translation of the will of the people into functioning democracies. Election law addresses issues who is entitled to vote, voter registration, ballot access, campaign finance and party funding, redistricting, apportionment, electronic voting and voting machines, accessibility of elections, election systems and formulas, vote counting, election disputes, referendums, and issues such as electoral fraud and electoral silence.

Criminal law

Criminal law, also known as penal law, pertains to crimes and punishment.[177] It thus regulates the definition of and penalties for offences found to have a sufficiently deleterious social impact but, in itself, makes no moral judgment on an offender nor imposes restrictions on society that physically prevent people from committing a crime in the first place.[178][179] Investigating, apprehending, charging, and trying suspected offenders is regulated by the law of criminal procedure.[180] The paradigm case of a crime lies in the proof, beyond reasonable doubt, that a person is guilty of two things. First, the accused must commit an act which is deemed by society to be criminal, or actus reus (guilty act).[181] Second, the accused must have the requisite malicious intent to do a criminal act, or mens rea (guilty mind). However, for so called "strict liability" crimes, an actus reus is enough.[182] Criminal systems of the civil law tradition distinguish between intention in the broad sense (dolus directus and dolus eventualis), and negligence. Negligence does not carry criminal responsibility unless a particular crime provides for its punishment.[183][184]

Examples of crimes include murder, assault, fraud and theft. In exceptional circumstances defences can apply to specific acts, such as killing in self defence, or pleading insanity. Another example is in the 19th-century English case of R v Dudley and Stephens, which tested a defence of "necessity".[185]

Criminal law offences are viewed as offences against not just individual victims, but the community as well.[178][179] The state, usually with the help of police, takes the lead in prosecution, which is why in common law countries cases are cited as "The People v ..." or "R (for Rex or Regina) v ...". Also, lay juries are often used to determine the guilt of defendants on points of fact: juries cannot change legal rules. Some developed countries still condone capital punishment for criminal activity, but the normal punishment for a crime will be imprisonment, fines, state supervision (such as probation), or community service. Modern criminal law has been affected considerably by the social sciences, especially with respect to sentencing, legal research, legislation, and rehabilitation.[186] On the international field, 111 countries are members of the International Criminal Court, which was established to try people for crimes against humanity.[187]

Contract law

Contract law concerns enforceable promises, and can be summed up in the Latin phrase pacta sunt servanda (agreements must be kept).[188] In common law jurisdictions, three key elements to the creation of a contract are necessary: offer and acceptance, consideration and the intention to create legal relations.

Consideration indicates the fact that all parties to a contract have exchanged something of value. Some common law systems, including Australia, are moving away from the idea of consideration as a requirement. The idea of estoppel or culpa in contrahendo, can be used to create obligations during pre-contractual negotiations.[189]

Civil law jurisdictions treat contracts differently in a number of respects, with a more interventionist role for the state in both the formation and enforcement of contracts.[190] Compared to common law jurisdictions, civil law systems incorporate more mandatory terms into contracts, allow greater latitude for courts to interpret and revise contract terms and impose a stronger duty of good faith, but are also more likely to enforce penalty clauses and specific performance of contracts.[190] They also do not require consideration for a contract to be binding.[191] In France, an ordinary contract is said to form simply on the basis of a "meeting of the minds" or a "concurrence of wills". Germany has a special approach to contracts, which ties into property law. Their 'abstraction principle' (Abstraktionsprinzip) means that the personal obligation of contract forms separately from the title of property being conferred. When contracts are invalidated for some reason (e.g. a car buyer is so drunk that he lacks legal capacity to contract)[192] the contractual obligation to pay can be invalidated separately from the proprietary title of the car. Unjust enrichment law, rather than contract law, is then used to restore title to the rightful owner.[193]

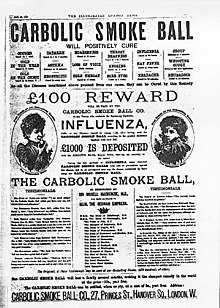

Torts and delicts

Certain civil wrongs are grouped together as torts under common law systems and delicts under civil law systems.[194] To have acted tortiously, one must have breached a duty to another person, or infringed some pre-existing legal right. A simple example might be unintentionally hitting someone with a ball.[195] Under the law of negligence, the most common form of tort, the injured party could potentially claim compensation for their injuries from the party responsible. The principles of negligence are illustrated by Donoghue v Stevenson.[j] A friend of Donoghue ordered an opaque bottle of ginger beer (intended for the consumption of Donoghue) in a café in Paisley. Having consumed half of it, Donoghue poured the remainder into a tumbler. The decomposing remains of a snail floated out. She claimed to have suffered from shock, fell ill with gastroenteritis and sued the manufacturer for carelessly allowing the drink to be contaminated. The House of Lords decided that the manufacturer was liable for Mrs Donoghue's illness. Lord Atkin took a distinctly moral approach and said:

The liability for negligence [...] is no doubt based upon a general public sentiment of moral wrongdoing for which the offender must pay. [...] The rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law, you must not injure your neighbour; and the lawyer's question, Who is my neighbour? receives a restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour.[196]

This became the basis for the four principles of negligence, namely that:

- Stevenson owed Donoghue a duty of care to provide safe drinks;

- he breached his duty of care;

- the harm would not have occurred but for his breach; and

- his act was the proximate cause of her harm.[j]

Another example of tort might be a neighbour making excessively loud noises with machinery on his property.[197] Under a nuisance claim the noise could be stopped. Torts can also involve intentional acts such as assault, battery or trespass. A better known tort is defamation, which occurs, for example, when a newspaper makes unsupportable allegations that damage a politician's reputation.[198] More infamous are economic torts, which form the basis of labour law in some countries by making trade unions liable for strikes,[199] when statute does not provide immunity.[k]

Property law

Property law governs ownership and possession. Real property, sometimes called 'real estate', refers to ownership of land and things attached to it.[201] Personal property, refers to everything else; movable objects, such as computers, cars, jewelry or intangible rights, such as stocks and shares. A right in rem is a right to a specific piece of property, contrasting to a right in personam which allows compensation for a loss, but not a particular thing back. Land law forms the basis for most kinds of property law, and is the most complex. It concerns mortgages, rental agreements, licences, covenants, easements and the statutory systems for land registration. Regulations on the use of personal property fall under intellectual property, company law, trusts and commercial law. An example of a basic case of most property law is Armory v Delamirie [1722].[202] A chimney sweep's boy found a jewel encrusted with precious stones. He took it to a goldsmith to have it valued. The goldsmith's apprentice looked at it, sneakily removed the stones, told the boy it was worth three halfpence and that he would buy it. The boy said he would prefer the jewel back, so the apprentice gave it to him, but without the stones. The boy sued the goldsmith for his apprentice's attempt to cheat him. Lord Chief Justice Pratt ruled that even though the boy could not be said to own the jewel, he should be considered the rightful keeper ("finders keepers") until the original owner is found. In fact the apprentice and the boy both had a right of possession in the jewel (a technical concept, meaning evidence that something could belong to someone), but the boy's possessory interest was considered better, because it could be shown to be first in time. Possession may be nine-tenths of the law, but not all.

This case is used to support the view of property in common law jurisdictions, that the person who can show the best claim to a piece of property, against any contesting party, is the owner.[203] By contrast, the classic civil law approach to property, propounded by Friedrich Carl von Savigny, is that it is a right good against the world. Obligations, like contracts and torts, are conceptualised as rights good between individuals.[204] The idea of property raises many further philosophical and political issues. Locke argued that our "lives, liberties and estates" are our property because we own our bodies and mix our labour with our surroundings.[205]

Equity and trusts

Equity is a body of rules that developed in England separately from the "common law". The common law was administered by judges and barristers. The Lord Chancellor on the other hand, as the King's keeper of conscience, could overrule the judge-made law if he thought it equitable to do so.[206] This meant equity came to operate more through principles than rigid rules. Whereas neither the common law nor civil law systems allow people to split the ownership from the control of one piece of property, equity allows this through an arrangement known as a trust. Trustees control property whereas the beneficial, or equitable, ownership of trust property is held by people known as beneficiaries. Trustees owe duties to their beneficiaries to take good care of the entrusted property.[207] Another example of a trustee's duty might be to invest property wisely or sell it.[208] This is especially the case for pension funds, the most important form of trust, where investors are trustees for people's savings until retirement. But trusts can also be set up for charitable purposes.

Further disciplines

- Law and society

- Labour law is the study of a tripartite industrial relationship between worker, employer and trade union. This involves collective bargaining regulation, and the right to strike. Individual employment law refers to workplace rights, such as job security, health and safety or a minimum wage.

- Human rights, civil rights and human rights law. These are laid down in codes such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights (which founded the European Court of Human Rights) and the U.S. Bill of Rights. The Treaty of Lisbon makes the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union legally binding in all member states except Poland and the United Kingdom.[209]

- Civil procedure and criminal procedure concern the rules that courts must follow as a trial and appeals proceed. Both concern a citizen's right to a fair trial or hearing.

- Evidence law involves which materials are admissible in courts for a case to be built.

- Immigration law and nationality law concern the rights of foreigners to live and work in a nation-state that is not their own and to acquire or lose citizenship. Both also involve the right of asylum and the problem of stateless individuals.

- Family law covers marriage and divorce proceedings, the rights of children and rights to property and money in the event of separation.

- Transactional law is the practice of law concerning business and money.

- Biolaw focuses on the intersection of law and the biosciences.

- Law and commerce

- Company law sprang from the law of trusts, on the principle of separating ownership of property and control.[210] The law of the modern company began with the Joint Stock Companies Act 1856, passed in the United Kingdom, which provided investors with a simple registration procedure to gain limited liability under the separate legal personality of the corporation.

- Commercial law covers complex contract and property law. The law of agency, insurance law, bills of exchange, insolvency and bankruptcy law and sales law trace back to the medieval Law Merchant. The UK Sale of Goods Act 1979 and the US Uniform Commercial Code are examples of codified common law commercial principles.

- Admiralty law and the sea law lay a basic framework for free trade and commerce across the world's oceans and seas, where outside of a country's zone of control. Shipping companies operate through ordinary principles of commercial law, generalised for a global market. Admiralty law also encompasses specialised issues such as salvage, maritime liens, and injuries to passengers.

- Intellectual property law aims at safeguarding creators and other producers of intellectual goods and services. These are legal rights (copyrights, trademarks, patents, and related rights) which result from intellectual activity in the industrial, literary and artistic fields.[211]

- Space law is a relatively new field dealing with aspects of international law regarding human activities in Earth orbit and outer space. While at first addressing space relations of countries via treaties, increasingly it is addressing areas such as space commercialisation, property, liability, and other issues.

- Закон и регулирование

- Налоговое законодательство включает положения, касающиеся налога на добавленную стоимость , корпоративного налога и подоходного налога .

- Банковское законодательство и финансовое регулирование устанавливают минимальные стандарты размеров капитала, которые должны иметь банки, а также правила наилучшей практики инвестирования. Это сделано для того, чтобы застраховаться от риска экономических кризисов, таких как крах Уолл-стрит в 1929 году .

- Регулирование касается предоставления государственных услуг и коммунальных услуг. Водное право является одним из примеров. Особенно после того, как приватизация стала популярной и вывела управление услугами из сферы публичного права, частные компании, выполняющие работу, ранее контролируемую государством, были связаны различной степенью социальной ответственности. Энергетика , газ , телекоммуникации и водоснабжение являются регулируемыми отраслями в большинстве стран ОЭСР .

- Законодательство о конкуренции , известное в Соединенных Штатах как антимонопольное право, представляет собой развивающуюся область, которая восходит к римским указам против фиксирования цен и английской доктрине ограничения торговой торговли . Современное законодательство о конкуренции основано на антикартельных и антимонопольных законах США ( Закон Шермана и Закон Клейтона ) начала 20-го века. Он используется для контроля над предприятиями, которые пытаются использовать свое экономическое влияние для искажения рыночных цен в ущерб благосостоянию потребителей .

- Закон о защите прав потребителей может включать в себя что угодно: от положений о несправедливых договорных условиях и положений до директив по страхованию багажа авиакомпаний.

- Экологическое право приобретает все большее значение, особенно в свете Киотского протокола и потенциальной опасности изменения климата . Защита окружающей среды также служит для наказания виновников загрязнения в рамках национальных правовых систем.

- Авиационное право регулирует все правила и технические стандарты, применимые к безопасной эксплуатации воздушных судов, и является важной частью как подготовки пилотов, так и их работы. Он основан на национальных законах (или законах) о гражданской авиации, которые сами по себе в основном соответствуют рекомендациям или обязательным стандартам Международной организации гражданской авиации или ИКАО.

Пересечение с другими полями

Экономика

В 18 веке Адам Смит представил философскую основу для объяснения взаимосвязи между правом и экономикой. [ л ] Эта дисциплина возникла частично из-за критики профсоюзов и антимонопольного законодательства США. Наиболее влиятельные сторонники, такие как Ричард Познер и Оливер Уильямсон , а также так называемая Чикагская школа экономистов и юристов, включая Милтона Фридмана и Гэри Беккера , обычно выступают за дерегулирование и приватизацию и враждебно относятся к государственному регулированию или к тому, что они считают ограничениями. о работе свободных рынков . [ 213 ]

Самым выдающимся экономическим аналитиком права является Нобелевской премии лауреат 1991 года Рональд Коуз , чья первая крупная статья «Природа фирмы» (1937) утверждала, что причиной существования фирм (компаний, товариществ и т. д.) является существование транзакционные издержки . [ 214 ] Рациональные люди торгуют посредством двусторонних контрактов на открытых рынках до тех пор, пока издержки транзакций не означают, что использование корпораций для производства вещей становится более рентабельным. В его второй крупной статье « Проблема социальных издержек» (1960) утверждалось, что если бы мы жили в мире без трансакционных издержек, люди торговались бы друг с другом, чтобы добиться одинакового распределения ресурсов, независимо от того, какое решение может принять суд в вопросах собственности. споры. [ 215 ] Коуз привел пример неприятного дела под названием «Стерджес против Бриджмена» , где шумный кондитер и тихий врач были соседями и обратились в суд, чтобы решить, кому следует переехать. [ 197 ] Коуз сказал, что независимо от того, постановит ли судья, что производитель сладостей должен прекратить использовать свое оборудование или что доктор должен с этим смириться, они могут заключить взаимовыгодную сделку о том, кто будет действовать, чтобы достичь того же результата в распределении ресурсов. Только существование трансакционных издержек может предотвратить это. [ 216 ] Таким образом, закон должен предвидеть то, что произойдет , и руководствоваться наиболее эффективным решением. Идея состоит в том, что законы и регулирование не так важны и эффективны для помощи людям, как полагают юристы и специалисты по государственному планированию. [ 217 ] Коуз и другие, подобные ему, хотели изменить подход, чтобы возложить бремя доказывания положительного воздействия на правительство, которое вмешивалось в рынок, путем анализа стоимости действий. [ 218 ]

Социология

Социология права исследует взаимодействие права с обществом и пересекается с юриспруденцией, философией права, социальной теорией и более специализированными предметами, такими как криминология . [ 219 ] [ 220 ] Это трансдисциплинарное и междисциплинарное исследование, ориентированное на теоретизацию и эмпирическое изучение юридической практики и опыта как социальных явлений. Институты социального строительства , социальные нормы , разрешение споров и правовая культура являются ключевыми областями для исследований в этой области знаний. В Соединенных Штатах эту область обычно называют исследованием права и общества; в Европе ее чаще называют социально-правовыми исследованиями. Поначалу юристы и философы права с подозрением относились к социологии права. Кельзен напал на одного из ее основателей, Ойгена Эрлиха , который стремился прояснить различия и связи между позитивным правом, которое юристы изучают и применяют, и другими формами «права» или социальными нормами, которые регулируют повседневную жизнь, в целом предотвращая дохождение конфликтов до юристов. и суды. [ 221 ] Современные исследования в области социологии права касаются того, как право развивается за пределами отдельных государственных юрисдикций, вырабатывается посредством социального взаимодействия на социальных аренах и приобретает разнообразие источников власти в национальных и транснациональных общинных сетях. [ 222 ]

Около 1900 года Макс Вебер определил свой «научный» подход к праву, определив «правовую рациональную форму» как тип доминирования, приписываемый не личному авторитету, а авторитету абстрактных норм. [ 223 ] Формальная юридическая рациональность была его термином для обозначения ключевой характеристики последовательного и исчисляемого закона, который был предпосылкой современного политического развития и современного бюрократического государства. Вебер считал, что этот закон развивался параллельно с ростом капитализма. [ 219 ] [ 220 ] Другой ведущий социолог, Эмиль Дюркгейм писал , в своей классической работе «Разделение труда в обществе» , что по мере того, как общество становится более сложным, корпус гражданского права, занимающегося прежде всего реституцией и компенсацией, увеличивается за счет уголовных законов и уголовных санкций. [ 224 ] [ 225 ] Среди других известных ранних социологов-юристов были Хьюго Синцхаймер , Теодор Гейгер , Жорж Гурвич и Леон Петражицкий в Европе, а также Уильям Грэм Самнер в США. [ 226 ] [ 227 ]

См. также

- Постановление

- Справедливость

- Юридический словарь

- Юридические исследования в США

- Юридический трактат

- Краткое содержание закона

- Политология

- Псевдозакон

- Закон об общественных интересах

- Социальное право

- Источники права

- Перевод слова «закон» на другие европейские языки

Примечания

- ^ Как правовая система римское право повлияло на развитие права во всем мире. Оно также составляет основу сводов законов большинства стран континентальной Европы и сыграло важную роль в создании идеи общеевропейской культуры (Штайн, Римское право в европейской истории , 2, 104–107).

- ^ Юрисдикции гражданского права признают обычай «еще одним источником права»; следовательно, ученые склонны делить гражданское право на широкие категории «писаного закона» ( ius scriptum ) или законодательства и «неписаного закона» ( ius non-scriptum ) или обычая. Тем не менее, они склонны игнорировать обычаи, считая их не столь важными по сравнению с законодательством (Георгиадис, Общие принципы гражданского права , 19; Вашофски, Принимая прецедент серьезно , 7).

- ^ «В одной из своих тщательно продуманных речей в Сенате США г-н Чарльз Самнер говорил о «щедрой презумпции общего права в пользу невиновности обвиняемого»; однако следует признать, что такую презумпцию нельзя найти в англосаксонском праве, где иногда кажется, что презумпция была противоположной. А в совсем недавнем деле Верховного суда США, деле Coffin, 156 US 432, указывается, что эта презумпция была полностью установлена в римском праве и сохранена в каноническом праве». [ 109 ]

- ^ Например, председатель суда является политическим назначенцем (Йенсен-Хеллер, Введение , 11–12). О понятии «независимости судебной власти» в Китае см. Findlay, Judiciary in the PRC , 282–284.

- ^ О «подотчетности кабинета министров» как в президентской, так и в парламентской системах см. Шугарт – Хаггард, Президентские системы , 67 и т. д.

- ^ В этих случаях суверенитет подрывается, и часто полевые командиры приобретают чрезмерные полномочия (Фукуяма, Государственное строительство , 166–167).

- ^ Хотя многие ученые утверждают, что «границы между публичным и частным правом становятся размытыми» и что это различие стало просто «фольклором» (Бергкамп, Ответственность и окружающая среда , 1–2).

- ^ Например, в Англии эти семь предметов, где международное право заменено законодательством ЕС, составляют «квалификационную юридическую степень». Критику см. в резких комментариях Питера Биркса к предыдущей версии « Уведомления для юридических школ», заархивированного 20 июня 2009 года в Wayback Machine .

- ↑ Уинстон Черчилль ( «Петля судьбы» , 719) комментирует провал Лиги Наций: «Было неправильно говорить, что Лига потерпела неудачу. Скорее, это были государства-члены, которые подвели Лигу». [ 163 ]

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Донохью против Стивенсона ( [1932] AC 532, 1932 SC (HL) 31, [1932] All ER Rep 1 ). Оригинальный текст дела см. в UK Law Online, архивировано 16 февраля 2007 г. на Wayback Machine .

- ^ В Великобритании Закон о профсоюзах и трудовых отношениях (консолидация) 1992 года ; см. в США Закон о национальных трудовых отношениях.

- ^ По словам Маллоя, Смит основал «классическую либеральную философию, которая сделала людей ключевым референтным знаком, признавая при этом, что мы живем не одни, а в сообществе с другими» ( «Право и экономика» , 114) .

Ссылки

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Робертсон 2006 , с. 90.

- ^ Уиллис 1926 .

- ^ Гиббс, Джек П. (1968). «Определения права и эмпирические вопросы». Обзор права и общества . 2 (3): 429–446. дои : 10.2307/3052897 . ISSN 0023-9216 . JSTOR 3052897 .

- ^ Акерс, Рональд Л. (1965). «К сравнительному определению права» . Журнал уголовного права и криминологии . 56 (3): 301–306. дои : 10.2307/1141239 . ISSN 0022-0205 . JSTOR 1141239 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 июля 2018 года . Проверено 3 января 2020 г.

- ^ Спунер, Лизандер (1882). Естественный закон; или «Наука справедливости: трактат о естественном праве, естественной справедливости, естественных правах, естественной свободе и естественном обществе»; Показывая, что любое законодательство, какое бы оно ни было, является абсурдом, узурпацией и преступлением. Часть первая . A. Williams & Co. Архивировано из оригинала 31 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 31 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ Нуньес Вакеро, Альваро (10 июня 2013 г.). «Пять моделей юридической науки» . Ревус. Журнал конституционной теории и философии права / Revija za ustavno gerarijo in filozofijo prava (19): 53–81. дои : 10.4000/revus.2449 . ISSN 1581-7652 . Архивировано из оригинала 31 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 31 декабря 2019 года .

- ^ Коэн 1992 .

- ^ Рубин, Баша (13 января 2015 г.). «Право – искусство или наука?: И то, и другое» . Форбс . Архивировано из оригинала 3 ноября 2018 года.

- ^ Бергер 1953 , с. 525.

- ^ Мейсон, Энтони (1996). «Судья как законодатель» (PDF) . Лекция Мэйо в Университете Джеймса Кука . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 31 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 31 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ Девинс, Нил (2008). «Реакция Конгресса на судебные решения» . Энциклопедия Верховного суда . Гейл Макмиллан. стр. 400–403. Архивировано из оригинала 31 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 31 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ Берман, Гарольд Дж. (1983). «Религиозные основы права на Западе: историческая перспектива». Журнал права и религии . 1 (1). Издательство Кембриджского университета: 3–43. дои : 10.2307/1051071 . JSTOR 1051071 . S2CID 146933872 .

- ^ Фокс, Джонатан; Сандлер, Шмуэль (1 апреля 2005 г.). «Разделение религии и государства в XXI веке: сравнение Ближнего Востока и западных демократий». Сравнительная политика . 37 (3): 317. дои : 10.2307/20072892 . JSTOR 20072892 .

- ^ Кокс, Ноэль (2001). «Церковная юрисдикция в церкви провинции Аотеароа, Новой Зеландии и Полинезии» . Обзор закона Дикина . 6 (2): 262. Архивировано из оригинала 31 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 31 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ Отто, Ян Михель, изд. (2010). Включенный шариат: сравнительный обзор правовых систем двенадцати мусульманских стран в прошлом и настоящем . Издательство Лейденского университета. ISBN 9789087280574 .

- ^ Райш, Мэрилин Джонсон. «Религиозно-правовые системы в сравнительном правоведении: Руководство к вводному исследованию – ГлобаЛекс» . Программа глобальной юридической школы Хаузера . Юридический факультет Нью-Йоркского университета. Архивировано из оригинала 31 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 31 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ Хорвиц, Мортон Дж. (1 июня 1982 г.). «История различия между общественным и частным» . Обзор права Пенсильванского университета . 130 (6): 1423–1428. дои : 10.2307/3311976 . JSTOR 3311976 . S2CID 51854776 . Проверено 3 января 2020 г. [ мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Мерриман, Джон Генри (1968). «Различие публичного и частного права в европейском и американском праве» . Журнал публичного права . 17 :3. Архивировано из оригинала 12 февраля 2020 года . Проверено 3 января 2020 г.

- ^ Сайман, Хаим Н. (6 июля 2008 г.). «Публичное право, частное право и юриспруденция» . Американский журнал сравнительного права . 56 (961). Сеть исследований социальных наук: 691–702. дои : 10.5131/ajcl.2007.0023 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 апреля 2020 года . Проверено 3 января 2020 г.

- ^ Харлоу, Кэрол (1 мая 1980 г.). « Публичное» и «частное» право: определение без различия» . Обзор современного права . 43 (3): 241–265. дои : 10.1111/j.1468-2230.1980.tb01592.x . ISSN 1468-2230 .

- ^ Сэмюэл, Джеффри (1 сентября 1983 г.). «Публичное и частное право: ответ частного юриста» . Обзор современного права . 46 (5): 558–583. дои : 10.1111/j.1468-2230.1983.tb02534.x . ISSN 1468-2230 .

- ^ Гордли, Джеймс (16 ноября 2006 г.). Рейманн, Матиас; Циммерманн, Рейнхард (ред.). «Сравнительное правоведение и история права» . Оксфордский справочник сравнительного правоведения : 752–774. doi : 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199296064.013.0024 . ISBN 9780199296064 . Архивировано из оригинала 31 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 31 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ Бор, Фредрик Л. (1974). «Связь между философией и правом». Журнал юридического образования . 26 (4): 539–543. ISSN 0022-2208 . JSTOR 42896964 .

- ^ Рубин, Пол Х. «Право и экономика» . Библиотека экономики и свободы . Liberty Fund, Inc. Архивировано из оригинала 2 июля 2019 года . Проверено 31 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ Банакар, Реза (2003). Слияние права и социологии: за пределами дихотомии в социально-правовых исследованиях . Берлин/Висконсин: Издательство Galda and Wilch Publishing. ISBN 1-931255-13-Х .

- ^ Паунд, Роско (1914). «Конец закона, развитый в правовых нормах и доктринах». Гарвардский обзор права . 27 (3): 195–234. дои : 10.2307/1325958 . ISSN 0017-811X . JSTOR 1325958 .

- ^ Сарат, Остин; Кернс, Томас, ред. (1996). Справедливость и несправедливость в праве и теории права . Издательство Мичиганского университета. стр. 18–19. дои : 10.3998/mpub.10283 . ISBN 9780472096251 . JSTOR 10.3998/mpub.10283 .

- ^ "лужайка." . Оксфордский словарь английского языка (онлайн-изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета . дои : 10.1093/OED/4864419306 . (Требуется подписка или членство участвующей организации .)

- ^ Руссо, Общественный договор , Книга II: Глава 6 (Закон)

- ^ Деннис Ллойд, барон Ллойд Хэмпстед . Введение в юриспруденцию . Третье издание. Стивенс и сыновья. Лондон. 1972. Второе впечатление. 1975. с. 39.

- ^ Мак Кубри, Хилэр и Уайт, Найджел Д. Учебник по юриспруденции . Второе издание. Блэкстоун Пресс Лимитед . 1996. ISBN 1-85431-582-X . п. 2.

- ^ Уильямс, Гланвилл. Международное право и споры относительно значения слова «право». Пересмотренная версия опубликована в журнале Laslett (редактор), Philosophy, Politics and Society (1956), стр. 134 и далее. Оригинал был опубликован в (1945 г.) 22 BYBIL 146.

- ^ Арнольд 1935 , с. 36.

- ^ Барон Ллойд Хэмпстед . Введение в юриспруденцию . Третье издание. Стивенс и сыновья. Лондон. 1972. Второе впечатление. 1975.

- ^ Кэмпбелл 1993 , с. 184.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бикс 2022 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дворкин 1986 , с. 410.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Однажды 1979 , с. 3–36.

- ^ Холмс, Оливер Венделл. «Путь права» (1897) 10 Harvard Law Review 457 на 461.

- ^ Фома Аквинский, Святой Фома. Сумма теологии 1а2ае, 90,4. Перевод Дж. Г. Доусона. Эд д'Энтрев. (Бэзил Блэквелл). Латинское: «нет ничего иного, как приказ того же разума для общего блага, обнародованный им ци, имеющий заботу об обществе».

- ^ МакКубри, Хилэр и Уайт, Найджел Д. Учебник по юриспруденции . Второе издание. Блэкстоун Пресс Лимитед. 1996. ISBN 1-85431-582-X . п. 73.

- ^ Тейлор, Т.В. (январь 1896 г.). «Понятие морали в юриспруденции». Философское обозрение . 5 (1): 36–50. дои : 10.2307/2176104 . JSTOR 2176104 .

- ^ Фриц Берольцхаймер , Мировая философия права , 115–116.

- ^ Кант, Иммануил , Основы метафизики морали , 42 (пар. 434)

- ^ Грин, Лесли. «Юридический позитивизм» . Стэнфордская энциклопедия философии . Архивировано из оригинала 9 июня 2007 года . Проверено 10 декабря 2006 г.

- ^ Ницше, О генеалогии морали , Второе эссе, 11.

- ^ Казандзакис, Фридрих Ницше и философия права , 97–98.

- ^ Линарелли, Ницше в соборе Закона , 23–26.