Коран

| Коран | |

|---|---|

| арабский : Коран , латинизированный : аль-Коран. | |

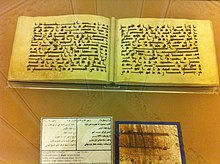

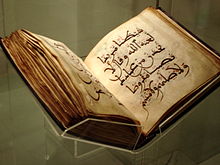

Два листа рукописи Бирмингемского Корана , ранней рукописи , написанной письмом хиджази, вероятно, датируемой при ок жизни Мухаммеда между . 568–645 | |

| Информация | |

| Религия | ислам |

| Язык | Классический арабский |

| Период | 610–632 гг. н. э. |

| Главы | 114 ( список ) См . Суру |

| Verses | 6,348 (including the basmala) 6,236 (excluding the basmala) See Āyah |

| Full text | |

Коран , [с] также латинизированный Коран или Коран , [д] — центральный религиозный текст ислама откровением , который мусульмане считают непосредственно от Алл Бога ( - х ). Он состоит из 114 глав ( сура , мн. сувер ), которые состоят из отдельных стихов ( аятов ). Помимо своего религиозного значения, оно широко считается лучшим произведением арабской литературы . [11] [12] [13] и оказал значительное влияние на арабский язык . Это также объект современной области академических исследований, известной как коранические исследования .

Мусульмане верят, что Коран был устно ниспослан Богом последнему исламскому пророку Мухаммеду через ангела Гавриила постепенно в течение примерно 23 лет, начиная с Ночи Могущества , когда Мухаммеду было 40 лет, и заканчивая 632 годом, годом его смерти. . Мухаммеда Мусульмане считают Коран самым важным чудом , доказательством его пророчества и кульминацией серии божественных посланий, начиная с тех, которые были открыты первому исламскому пророку , включая исламские священные книги Торы Адаму , Псалмов и Евангелия .

The Quran is believed by Muslims to be God's own divine speech providing a complete code of conduct across all facets of life. This has led Muslim theologians to fiercely debate whether the Quran was "created or uncreated." According to tradition, several of Muhammad's companions served as scribes, recording the revelations. Shortly after Muhammad's death, the Quran was compiled on the order of the first caliph Abu Bakr (r. 632–634) by the companions, who had written down or memorized parts of it. Caliph Uthman (r. 644–656) established a standard version, now known as the Uthmanic codex, which is generally considered the archetype of the Quran known today. There are, however, variant readings, with mostly minor differences in meaning.

The Quran assumes the reader's familiarity with major narratives recounted in the Biblical and apocryphal texts. It summarizes some, dwells at length on others and, in some cases, presents alternative accounts and interpretations of events. The Quran describes itself as a book of guidance for humankind (2:185). It sometimes offers detailed accounts of specific historical events, and it often emphasizes the moral significance of an event over its narrative sequence.

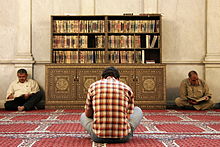

Supplementing the Quran with explanations for some cryptic Quranic narratives, and rulings that also provide the basis for Islamic law in most denominations of Islam, are hadiths—oral and written traditions believed to describe words and actions of Muhammad. During prayers, the Quran is recited only in Arabic. Someone who has memorized the entire Quran is called a hafiz. Ideally, verses are recited with a special kind of prosody reserved for this purpose called tajwid. During the month of Ramadan, Muslims typically complete the recitation of the whole Quran during tarawih prayers. In order to extrapolate the meaning of a particular Quranic verse, Muslims rely on exegesis, or commentary rather than a direct translation of the text.

| Quran |

|---|

Etymology and meaning

The word qur'ān appears about 70 times in the Quran itself,[14] assuming various meanings. It is a verbal noun (maṣdar) of the Arabic verb qara'a (قرأ) meaning 'he read' or 'he recited'. The Syriac equivalent is qeryānā (ܩܪܝܢܐ), which refers to 'scripture reading' or 'lesson'.[15] While some Western scholars consider the word to be derived from the Syriac, the majority of Muslim authorities hold the origin of the word is qara'a itself.[16] Regardless, it had become an Arabic term by Muhammad's lifetime.[16] An important meaning of the word is the 'act of reciting', as reflected in an early Quranic passage: "It is for Us to collect it and to recite it (qur'ānahu)."[17]

In other verses, the word refers to 'an individual passage recited [by Muhammad]'. Its liturgical context is seen in a number of passages, for example: "So when al-qur'ān is recited, listen to it and keep silent."[18] The word may also assume the meaning of a codified scripture when mentioned with other scriptures such as the Torah and Gospel.[19]

The term also has closely related synonyms that are employed throughout the Quran. Each synonym possesses its own distinct meaning, but its use may converge with that of qur'ān in certain contexts. Such terms include kitāb ('book'), āyah ('sign'), and sūrah ('scripture'); the latter two terms also denote units of revelation. In the large majority of contexts, usually with a definite article (al-), the word is referred to as the waḥy ('revelation'), that which has been "sent down" (tanzīl) at intervals.[20][21] Other related words include: dhikr ('remembrance'), used to refer to the Quran in the sense of a reminder and warning; and ḥikmah ('wisdom'), sometimes referring to the revelation or part of it.[16][e]

The Quran describes itself as 'the discernment' (al-furqān), 'the mother book' (umm al-kitāb), 'the guide' (huda), 'the wisdom' (hikmah), 'the remembrance' (dhikr), and 'the revelation' (tanzīl; 'something sent down', signifying the descent of an object from a higher place to lower place).[22] Another term is al-kitāb ('The Book'), though it is also used in the Arabic language for other scriptures, such as the Torah and the Gospels. The term mus'haf ('written work') is often used to refer to particular Quranic manuscripts but is also used in the Quran to identify earlier revealed books.[16]

History

Prophetic era

Islamic tradition relates that Muhammad received his first revelation in 610 CE in the Cave of Hira on the Night of Power[23] during one of his isolated retreats to the mountains. Thereafter, he received revelations over a period of 23 years. According to hadith (traditions ascribed to Muhammad)[f][24] and Muslim history, after Muhammad and his followers immigrated to Medina and formed an independent Muslim community, he ordered many of his companions to recite the Quran and to learn and teach the laws, which were revealed daily. It is related that some of the Quraysh who were taken prisoners at the Battle of Badr regained their freedom after they had taught some of the Muslims the simple writing of the time. Thus a group of Muslims gradually became literate. As it was initially spoken, the Quran was recorded on tablets, bones, and the wide, flat ends of date palm fronds. Most suras were in use amongst early Muslims since they are mentioned in numerous sayings by both Sunni and Shia sources, relating Muhammad's use of the Quran as a call to Islam, the making of prayer and the manner of recitation. However, the Quran did not exist in book form at the time of Muhammad's death in 632 at age 61–62.[16][25][26][27][28][29] There is agreement among scholars that Muhammad himself did not write down the revelation.[30]

Sahih al-Bukhari narrates Muhammad describing the revelations as, "Sometimes it is (revealed) like the ringing of a bell" and A'isha reported, "I saw the Prophet being inspired Divinely on a very cold day and noticed the sweat dropping from his forehead (as the Inspiration was over)."[g] Muhammad's first revelation, according to the Quran, was accompanied with a vision. The agent of revelation is mentioned as the "one mighty in power,"[32] the one who "grew clear to view when he was on the uppermost horizon. Then he drew nigh and came down till he was (distant) two bows' length or even nearer."[28][33] The Islamic studies scholar Welch states in the Encyclopaedia of Islam that he believes the graphic descriptions of Muhammad's condition at these moments may be regarded as genuine, because he was severely disturbed after these revelations. According to Welch, these seizures would have been seen by those around him as convincing evidence for the superhuman origin of Muhammad's inspirations. However, Muhammad's critics accused him of being a possessed man, a soothsayer, or a magician since his experiences were similar to those claimed by such figures well known in ancient Arabia. Welch additionally states that it remains uncertain whether these experiences occurred before or after Muhammad's initial claim of prophethood.[34]

The Quran describes Muhammad as "ummi",[35] which is traditionally interpreted as 'illiterate', but the meaning is rather more complex. Medieval commentators such as al-Tabari (d. 923) maintained that the term induced two meanings: first, the inability to read or write in general; second, the inexperience or ignorance of the previous books or scriptures (but they gave priority to the first meaning). Muhammad's illiteracy was taken as a sign of the genuineness of his prophethood. For example, according to Fakhr al-Din al-Razi, if Muhammad had mastered writing and reading he possibly would have been suspected of having studied the books of the ancestors. Some scholars such as W. Montgomery Watt prefer the second meaning of ummi—they take it to indicate unfamiliarity with earlier sacred texts.[28][36]

The final verse of the Quran was revealed on the 18th of the Islamic month of Dhu al-Hijjah in the year 10 A.H., a date that roughly corresponds to February or March 632. The verse was revealed after the Prophet finished delivering his sermon at Ghadir Khumm.

Compilation and preservation

Following Muhammad's death in 632, a number of his companions who memorized the Quran were killed in the Battle of al-Yamama by Musaylima. The first caliph, Abu Bakr (r. 632–634), subsequently decided to collect the book in one volume so that it could be preserved.[37] Zayd ibn Thabit (d. 655) was the person to collect the Quran since "he used to write the Divine Inspiration for Allah's Apostle".[38] Thus, a group of scribes, most importantly Zayd, collected the verses and produced a hand-written manuscript of the complete book. The manuscript according to Zayd remained with Abu Bakr until he died. Zayd's reaction to the task and the difficulties in collecting the Quranic material from parchments, palm-leaf stalks, thin stones (collectively known as suhuf, any written work containing divine teachings)[39] and from men who knew it by heart is recorded in earlier narratives. In 644, Muhammad's widow Hafsa bint Umar was entrusted with the manuscript until the third caliph, Uthman (r. 644–656),[38] requested the standard copy from her.[40] According to historian Michael Cook, early Muslim narratives about the collection and compilation of the Quran sometimes contradict themselves: "Most ... make Uthman little more than an editor, but there are some in which he appears very much a collector, appealing to people to bring him any bit of the Quran they happen to possess." Some accounts also "suggest that in fact the material" Abu Bakr worked with "had already been assembled", which since he was the first caliph, would mean they were collected when Muhammad was still alive.[41]

In about 650, Uthman began noticing slight differences in pronunciation of the Quran as Islam expanded beyond the Arabian Peninsula into Persia, the Levant, and North Africa. In order to preserve the sanctity of the text, he ordered a committee headed by Zayd to use Abu Bakr's copy and prepare a standard text of the Quran.[42][43] Thus, within 20 years of Muhammad's death in 632,[44] the complete Quran was committed to written form as the Uthmanic codex. That text became the model from which copies were made and promulgated throughout the urban centers of the Muslim world, and other versions are believed to have been destroyed.[42][45][46][47] The present form of the Quran text is accepted by Muslim scholars to be the original version compiled by Abu Bakr.[28][29][h][i]

This preservation of the Quran is considered one of the miracles of the Quran among the Islamic faithful.[j]

Shias recite the Quran according to the qira'at of Hafs on authority of ‘Asim, which is the prevalent qira’at in the Islamic world[53] and believe that the Quran was gathered and compiled by Muhammad during his lifetime.[54][55] It is claimed that the Shia had more than 1,000 hadiths ascribed to the Shia Imams which indicate the distortion of the Quran[56] and according to Etan Kohlberg, this belief about Quran was common among Shiites in the early centuries of Islam.[57] In his view, Ibn Babawayh was the first major Twelver author "to adopt a position identical to that of the Sunnis" and the change was a result of the "rise to power of the Sunni 'Abbasid caliphate," whence belief in the corruption of the Quran became untenable vis-a-vis the position of Sunni “orthodoxy”.[58] Alleged distortions to have been carried out to remove any references to the rights of Ali, the Imams and their supporters and the disapproval of enemies, such as Umayyads and Abbasids.[59]

Other personal copies of the Quran might have existed including Ibn Mas'ud's and Ubay ibn Ka'b's codex, none of which exist today.[16][42][60]

Academic research

Since Muslims could regard criticism of the Qur'an as a crime of apostasy punishable by death under sharia, it seemed impossible to conduct studies on the Qur'an that went beyond textual criticism.[61][62] Until the early 1970s,[63] non-Muslim scholars of Islam —while not accepting traditional explanations for divine intervention— accepted the above-mentioned traditional origin story in most details.[37]

Rasm: "ٮسم الله الرحمں الرحىم"

University of Chicago professor Fred Donner states that:[64]

[T]here was a very early attempt to establish a uniform consonantal text of the Qurʾān from what was probably a wider and more varied group of related texts in early transmission.… After the creation of this standardized canonical text, earlier authoritative texts were suppressed, and all extant manuscripts—despite their numerous variants—seem to date to a time after this standard consonantal text was established.

Although most variant readings of the text of the Quran have ceased to be transmitted, some still are.[65][66] There has been no critical text produced on which a scholarly reconstruction of the Quranic text could be based.[k]

In 1972, in a mosque in the city of Sana'a, Yemen, manuscripts "consisting of 12,000 pieces" were discovered that were later proven to be the oldest Quranic text known to exist at the time. The Sana'a manuscripts contain palimpsests, manuscript pages from which the text has been washed off to make the parchment reusable again—a practice which was common in ancient times due to the scarcity of writing material. However, the faint washed-off underlying text (scriptio inferior) is still barely visible.[68] Studies using radiocarbon dating indicate that the parchments are dated to the period before 671 CE with a 99 percent probability.[69][70] The German scholar Gerd R. Puin has been investigating these Quran fragments for years. His research team made 35,000 microfilm photographs of the manuscripts, which he dated to the early part of the 8th century. Puin has noted unconventional verse orderings, minor textual variations, and rare styles of orthography, and suggested that some of the parchments were palimpsests which had been reused. Puin believed that this implied an evolving text as opposed to a fixed one.[71]

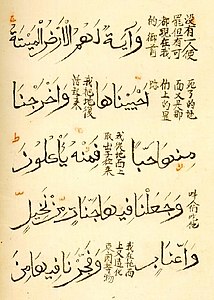

In 2015, a single folio of a very early Quran, dating back to 1370 years earlier, was discovered in the library of the University of Birmingham, England. According to the tests carried out by the Oxford University Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, "with a probability of more than 95%, the parchment was from between 568 and 645". The manuscript is written in Hijazi script, an early form of written Arabic.[72] This possibly was one of the earliest extant exemplars of the Quran, but as the tests allow a range of possible dates, it cannot be said with certainty which of the existing versions is the oldest.[72] Saudi scholar Saud al-Sarhan has expressed doubt over the age of the fragments as they contain dots and chapter separators that are believed to have originated later.[73] The Birmingham manuscript holds significance amongst scholarship because of its early dating and potential overlap with the dominant tradition over the lifetime of Muhammad c. 570 to 632 CE[74] and used as evidence to support conventional wisdom and to refute the revisionists' views on the history of the writing of the Quran.[75]

Contents

The Quranic content is concerned with basic Islamic beliefs including the existence of God and the resurrection. Narratives of the early prophets, ethical and legal subjects, historical events of Muhammad's time, charity and prayer also appear in the Quran. The Quranic verses contain general exhortations regarding right and wrong and historical events are related to outline general moral lessons. Verses pertaining to natural phenomena have been interpreted by Muslims as an indication of the authenticity of the Quranic message.[76] The style of the Quran has been called "allusive", with commentaries needed to explain what is being referred to—"events are referred to, but not narrated; disagreements are debated without being explained; people and places are mentioned, but rarely named."[77]

Persian miniature (c. 1595), tinted drawing on paper

Many places, subjects and mythological figures in the culture of Arabs and many nations in their historical neighbourhoods, especially Judeo-Christian stories,[78] are included in the Quran with small allusions, references or sometimes small narratives such as firdaws, Seven sleepers, Queen of Sheba etc. However, some philosophers and scholars such as Mohammed Arkoun, who emphasize the mythological character of the language and content of the Quran, are met with rejectionist attitudes in Islamic circles.[79]

The stories of Yusuf and Zulaikha, Moses, Family of Amram (parents of Mary according to Quran) and mysterious hero[80][81][82][83] Dhul-Qarnayn ("the man with two horns") who built a barrier against Gog and Magog that will remain until the end of time are more detailed and longer stories. Apart from semi-historical events and characters such as King Solomon and David, about Jewish history as well as the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt, tales of the hebrew prophets accepted in Islam, such as Creation, the Flood, struggle of Abraham with Nimrod, sacrifice of his son occupy a wide place in the Quran.

The Quran assumes the reader's familiarity with major narratives recounted in the Biblical and apocryphal scriptures. It summarizes some, dwells at length on others and, in some cases, presents alternative accounts and interpretations of events.[84][85] The Quran describes itself as a book of guidance for humankind (2:185). It sometimes offers detailed accounts of specific historical events, and it often emphasizes the moral significance of an event over its narrative sequence.[86] Supplementing the Quran with explanations for some cryptic Quranic narratives, and rulings that also provide the basis for Islamic law in most denominations of Islam,[24][l]

Creation and God

The Quran uses cosmological and contingency arguments in various verses without referring to the terms to prove the existence of God. Therefore, the universe is originated and needs an originator, and whatever exists must have a sufficient cause for its existence. Besides, the design of the universe is frequently referred to as a point of contemplation: "It is He who has created seven heavens in harmony. You cannot see any fault in God's creation; then look again: Can you see any flaw?"[87][88]

The central theme of the Quran is monotheism. God is depicted as living, eternal, omniscient and omnipotent (see, e.g., Quran 2:20, 2:29, 2:255). God's omnipotence appears above all in his power to create. He is the creator of everything, of the heavens and the earth and what is between them (see, e.g., Quran 13:16, 2:253, 50:38, etc.). All human beings are equal in their utter dependence upon God, and their well-being depends upon their acknowledging that fact and living accordingly.[28][76]

Even though Muslims do not doubt about the existence and unity of God, they may have adopted different attitudes that have changed and developed throughout history regarding his nature (attributes), names and relationship with creation.

Prophets

In Islam, God speaks to people called prophets through a kind of revelation called wahy or through angels.(42:51) Although poetry (Shu'ara: 224) and prophecy (claiming to know the unseen or the future) are seen as despicable behavior in Islam, (7:188, 27:65) nubuwwah (Arabic: نبوة "prophethood") is seen as a duty imposed by God on individuals who have some characteristics such as intelligence, honesty, fortitude and justice. (See:Ismah) "Nothing is said to you that was not said to the messengers before you, that your lord has at his Command forgiveness as well as a most Grievous Penalty."[89]

Islam regards Abraham as a link in the chain of prophets that begins with Adam and culminates in Muhammad via Ishmael[90] and mentioned in 35 chapters of the Quran, more often than any other biblical personage apart from Moses.[91] Muslims regard him as an idol smasher, hanif,[92] an archetype of the perfect Muslim, and revered prophet and builder of the Kaaba in Mecca.[93] The Quran consistently refers to Islam as "the Religion of Abraham" (millat Ibrahim).[94] Besides Ishaq and Yaqub, Abraham is among the most honorable, excellent role model father for Muslims.[95][96][97]

In Islam, Eid-al-Adha is celebrated to commemorate Abraham's attempt to sacrifice his son by surrendering in line with his dream,(As-Saaffat; 100–107) which he accepted as the will of GOD.[98] In Judaism the story is perceived as a narrative designed to replace child sacrifice with animal sacrifice in general[99] or as a metaphor describing "sacrific[ing one's] animalistic nature",[100][101] Orthodox Islamic understanding considers animal sacrifice as a mandatory or strong sunnah for Muslims who meet certain conditions, on a certain date determined by the Hijri calendar every year.

Mūsā is a prominent prophet and messenger of God and is the most frequently mentioned individual in the Quran, with his name being mentioned 136 times and his life being narrated and recounted more than that of any other prophet.[102][103]

Ethico-religious concepts

Faith is a fundamental aspect of morality in the Quran, and scholars have tried to determine the semantic contents of "belief" and "believer" in the Quran.[104] The ethico-legal concepts and exhortations dealing with righteous conduct are linked to a profound awareness of God, thereby emphasizing the importance of faith, accountability, and the belief in each human's ultimate encounter with God. People are invited to perform acts of charity, especially for the needy. Believers who "spend of their wealth by night and by day, in secret and in public" are promised that they "shall have their reward with their Lord; on them shall be no fear, nor shall they grieve."[105]

It also affirms family life by legislating on matters of marriage, divorce, and inheritance. A number of practices, such as usury and gambling, are prohibited. The Quran is one of the fundamental sources of Islamic law (sharia). Some formal religious practices receive significant attention in the Quran including the salat and fasting in the month of Ramadan. As for the manner in which the prayer is to be conducted, the Quran refers to prostration.[37][106] The term chosen for charity, zakat, literally means purification implies that it is a self-purification.[107][108] In fiqh, the term fard is used for clear imperative provisions based on the Quran. However, it is not possible to say that the relevant verses are understood in the same way by all segments of Islamic commentators; For example, Hanafis accept 5 daily prayers as fard. However, some religious groups such as Quranists and Shiites, who do not doubt that the Quran existing today is a religious source, infer from the same verses that it is clearly ordered to pray 2 or 3 times,[109][110][111][112] not 5 times.

Although it is believed in Islam that the pre-Islamic prophets provided general guidance and that some books were sent down to them, their stories such as Lot and story with his daughters in the Bible conveyed from any source are called Israʼiliyyat and are met with suspicion.[113] The provisions that might arise from them, (such as the consumption of wine) could only be "abrogated provisions" (naskh).[114] The guidance of the Quran and Muhammad is considered absolute, universal and will continue until the end of time. However, today, this understanding is questioned in certain circles, it is claimed that the provisions and contents in sources such as the Quran and hadith, apart from general purposes,[115] are contents that reflect the general understanding and practices of that period,[116] and it is brought up to replace the sharia practices that pose problems in terms of today's ethic values[117][118] with new interpretations.

Eschatology

The doctrine of the last day and eschatology (the final fate of the universe) may be considered the second great doctrine of the Quran.[28] It is estimated that approximately one-third of the Quran is eschatological, dealing with the afterlife in the next world and with the day of judgment at the end of time.[119] The Quran does not assert a natural immortality of the human soul, since man's existence is dependent on the will of God: when he wills, he causes man to die; and when he wills, he raises him to life again in a bodily resurrection.[106]

In the Quran belief in the afterlife is often referred in conjunction with belief in God: "Believe in God and the last day"[120] emphasizing what is considered impossible is easy in the sight of God. A number of suras such as 44, 56, 75, 78, 81 and 101 are directly related to the afterlife and warn people to be prepared for the "imminent" day referred to in various ways. It is 'the Day of Judgment,' 'the Last Day,' 'the Day of Resurrection,' or simply 'the Hour.' Less frequently it is 'the Day of Distinction', 'the Day of the Gathering' or 'the Day of the Meeting'.[28]

"Signs of the hour" in the Quran are a "Beast of the Earth" will arise (27:82); the nations Gog and Magog will break through their ancient barrier wall and sweep down to scourge the earth (21:96-97); and Jesus is "a sign of the hour." Despite the uncertainty of the time is emphasized with the statement that it is only in the presence of God,(43:61) there is a rich eschatological literature in the Islamic world and doomsday prophecies in the Islamic world are heavily associated with "round" numbers.[121] Said Nursi interpreted the expressions in the Quran and hadiths as metaphorical or allegorical symbolizations[122] and benefited from numerological methods applied to some ayah/hadith fragments in his own prophecies.[123]

In the apocalyptic scenes, clues are included regarding the nature, structure and dimensions of the celestial bodies as perceived in the Quran: While the stars are lamps illuminating the sky in ordinary cases, turns into stones (Al-Mulk 1-5) or (shahap; meteor, burning fire) (al-Jinn 9) thrown at demons that illegally ascend to the sky; When the time of judgment comes, they spill onto the earth, but this does not mean that life on earth ends; People run left and right in fear.(At-Takwir 1-7) Then a square is set up and the king or lord of the day;(māliki yawmi-d-dīn)[i] comes and shows his shin;[127][128] looks are fearful, are invited to prostration; but those invited in the past but stayed away, cannot do this.(Al-Qalam 42-43)

Some researchers have no hesitation that many doomsday concepts, some of which are also used in the Quran, such as firdaws, kawthar, jahannam, maalik have come from foreign cultures through historical evolution.[129]

Science and the Quran

According to M. Shamsher Ali, there are around 750 verses in the Quran dealing with natural phenomena and many verses of the Quran ask mankind to study nature, and this has been interpreted to mean an encouragement for scientific inquiry,[130] and of the truth. Some include, “Travel throughout the earth and see how He brings life into being” (Q29:20), “Behold in the creation of the heavens and the earth, and the alternation of night and day, there are indeed signs for men of understanding ...” (Q3:190) The astrophysicist Nidhal Guessoum writes: "The Qur'an draws attention to the danger of conjecturing without evidence (And follow not that of which you have not the knowledge of... 17:36) and in several different verses asks Muslims to require proofs (Say: Bring your proof if you are truthful 2:111)." He associates some scientific contradictions that can be seen in the Quran with a superficial reading of the Quran.[131]

Ismail al-Faruqi and Taha Jabir Alalwani are of the view that any reawakening of the Muslim civilization must start with the Quran; however, the biggest obstacle on this route is the "centuries old heritage of tafseer and other disciplines which inhibit a "universal conception" of the Quran's message.[132] Author Rodney Stark argues that Islam's lag behind the West in scientific advancement after (roughly) 1500 AD was due to opposition by traditional ulema to efforts to formulate systematic explanation of natural phenomenon with "natural laws." He claims that they believed such laws were blasphemous because they limit "God's freedom to act" as He wishes.[133]

Taner Edis wrote many Muslims appreciate technology and respect the role that science plays in its creation. As a result, he says there is a great deal of Islamic pseudoscience attempting to reconcile this respect with religious beliefs.[134] This is because, according to Edis, true criticism of the Quran is almost non-existent in the Muslim world. While Christianity is less prone to see its Holy Book as the direct word of God, fewer Muslims will compromise on this idea – causing them to believe that scientific truths must appear in the Quran.[134]

Starting in the 1970s and 80s, the idea of presence of scientific evidence in the Quran became popularized as ijaz (miracle) literature, also called "Bucailleism", and began to be distributed through Muslim bookstores and websites.[135][136] The movement contends that the Quran abounds with "scientific facts" that appeared centuries before their discovery and promotes Islamic creationism. According to author Ziauddin Sardar, the ijaz movement has created a "global craze in Muslim societies", and has developed into an industry that is "widespread and well-funded".[135][136][137] Individuals connected with the movement include Abdul Majeed al-Zindani, who established the Commission on Scientific Signs in the Quran and Sunnah; Zakir Naik, the Indian televangelist; and Adnan Oktar, the Turkish creationist.[135]

Enthusiasts of the movement argue that among the miracles found in the Quran are "everything, from relativity, quantum mechanics, Big Bang theory, black holes and pulsars, genetics, embryology, modern geology, thermodynamics, even the laser and hydrogen fuel cells".[135] Zafar Ishaq Ansari terms the modern trend of claiming the identification of "scientific truths" in the Quran as the "scientific exegesis" of the holy book.[138] In 1983, Keith L. Moore, had a special edition published of his widely used textbook on Embryology (The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology), co-authored by Abdul Majeed al-Zindani with Islamic Additions,[139] interspersed pages of "embryology-related Quranic verse and hadith" by al-Zindani into Moore's original work.[140] Ali A. Rizvi studying the textbook of Moore and al-Zindani found himself "confused" by "why Moore was so 'astonished by'" the Quranic references, which Rizvi found "vague", and insofar as they were specific, preceded by the observations of Aristotle and the Ayr-veda,[141] or easily explained by "common sense".[140][142]

Critics argue, verses that proponents say explain modern scientific facts, about subjects such as biology, the origin and history of the Earth, and the evolution of human life, contain fallacies and are unscientific.[136][143] As of 2008, both Muslims and non-Muslims have disputed whether there actually are "scientific miracles" in the Quran. Muslim critics of the movement include Indian Islamic theologian Maulana Ashraf ‘Ali Thanvi, Muslim historian Syed Nomanul Haq, Muzaffar Iqbal, president of Center for Islam and Science in Alberta, Canada, and Egyptian Muslim scholar Khaled Montaser.[144]

Text and arrangement

The Quran consists of 114 chapters of varying lengths, known as a sūrah. Chapters are classified as Meccan or Medinan, depending on whether the verses were revealed before or after the migration of Muhammad to the city of Medina. However, a sūrah classified as Medinan may contain Meccan verses in it and vice versa. Sūrah names are derived from a name or quality discussed in the text, or from the first letters or words of the sūrah. Chapters are not arranged in chronological order, rather the chapters appear to be arranged roughly in order of decreasing size. Some scholars argue the sūrahs are arranged according to a certain pattern.[145] Each sūrah except the ninth starts with the Bismillah (بِسْمِ ٱللَّٰهِ ٱلرَّحْمَٰنِ ٱلرَّحِيمِ), an Arabic phrase meaning 'In the name of God.' There are, however, still 114 occurrences of the Bismillah in the Quran, due to its presence in Quran 27:30 as the opening of Solomon's letter to the Queen of Sheba.[146][147]

Each sūrah consists of verses, known as āyāt, which originally means a 'sign' or 'evidence' sent by God. The number of verses differs from sūrah to sūrah. An individual verse may be just a few letters or several lines. The total number of verses in the most popular Hafs Quran is 6,236;[m] however, the number varies if the bismillahs are counted separately.

In addition of the division into chapters, there are various ways of dividing Quran into parts of approximately equal length for convenience in reading. The 30 juz' (plural ajzāʼ) can be used to read through the entire Quran in a month. A juz' is sometimes further divided into two ḥizb (plural aḥzāb), and each hizb subdivided into four rubʻ al-ahzab. The Quran is also divided into seven approximately equal parts, manzil (plural manāzil), for it to be recited in a week.[16]

A different structure is provided by semantic units resembling paragraphs and comprising roughly ten āyāt each. Such a section is called a ruku.

The Muqattaʿat (Arabic: حروف مقطعات ḥurūf muqaṭṭaʿāt, 'disjoined letters, disconnected letters';[149] also 'mysterious letters')[150] are combinations of between one and five Arabic letters figuring at the beginning of 29 out of the 114 chapters of the Quran just after the basmala.[150] The letters are also known as fawātih (فواتح), or 'openers', as they form the opening verse of their respective suras. Four surahs are named for their muqatta'at: Ṭāʾ-Hāʾ, Yāʾ-Sīn, Ṣād, and Qāf. The original significance of the letters is unknown. Tafsir (exegesis)[151] has interpreted them as abbreviations for either names or qualities of God or for the names or content of the respective surahs. According to Rashad Khalifa, those letters are Quranic initials for a hypothetical mathematical code in the Quran, namely the Quran code[152] but this has been criticized by Bilal Philips as a hoax based on falsified data, misinterpretations of the Quran's text.[153]

According to one estimate the Quran consists of 77,430 words, 18,994 unique words, 12,183 stems, 3,382 lemmas and 1,685 roots.[154]

Literary style

The Quran's message is conveyed with various literary structures and devices. In the original Arabic, the suras and verses employ phonetic and thematic structures that assist the audience's efforts to recall the message of the text. Muslims[who?] assert (according to the Quran itself) that the Quranic content and style is inimitable.[155]

The language of the Quran has been described as "rhymed prose" as it partakes of both poetry and prose; however, this description runs the risk of failing to convey the rhythmic quality of Quranic language, which is more poetic in some parts and more prose-like in others. Rhyme, while found throughout the Quran, is conspicuous in many of the earlier Meccan suras, in which relatively short verses throw the rhyming words into prominence. The effectiveness of such a form is evident for instance in Sura 81, and there can be no doubt that these passages impressed the conscience of the hearers. Frequently a change of rhyme from one set of verses to another signals a change in the subject of discussion. Later sections also preserve this form but the style is more expository.[156][157]

The Quranic text seems to have no beginning, middle, or end, its nonlinear structure being akin to a web or net.[16] The textual arrangement is sometimes considered to exhibit lack of continuity, absence of any chronological or thematic order and repetitiousness.[n][o] Michael Sells, citing the work of the critic Norman O. Brown, acknowledges Brown's observation that the seeming disorganization of Quranic literary expression—its scattered or fragmented mode of composition in Sells's phrase—is in fact a literary device capable of delivering profound effects as if the intensity of the prophetic message were shattering the vehicle of human language in which it was being communicated.[160][161] Sells also addresses the much-discussed repetitiveness of the Quran, seeing this, too, as a literary device.

A text is self-referential when it speaks about itself and makes reference to itself. According to Stefan Wild, the Quran demonstrates this metatextuality by explaining, classifying, interpreting and justifying the words to be transmitted. Self-referentiality is evident in those passages where the Quran refers to itself as revelation (tanzil), remembrance (dhikr), news (naba'), criterion (furqan) in a self-designating manner (explicitly asserting its Divinity, "And this is a blessed Remembrance that We have sent down; so are you now denying it?"),[162] or in the frequent appearance of the "Say" tags, when Muhammad is commanded to speak (e.g., "Say: 'God's guidance is the true guidance'", "Say: 'Would you then dispute with us concerning God?'"). According to Wild the Quran is highly self-referential. The feature is more evident in early Meccan suras.[163]

Significance in Islam

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

Quran says, "We have sent down the Quran in truth, and with the truth it has come down"[164] and frequently asserts in its text that it is divinely ordained.[165] The Quran speaks of a written pre-text that records God's speech before it is sent down, the "preserved tablet" that is the basis of the belief in fate also, and Muslims believe that the Quran was sent down or started to be sent down on the Laylat al-Qadr.[107][166]

Revered by pious Muslims as "the holy of holies",[167] whose sound moves some to "tears and ecstasy",[168] it is the physical symbol of the faith, the text often used as a charm on occasions of birth, death, marriage. Traditionally, before starting to read the Quran, ablution is performed, one seeks refuge in Allah from the accursed Satan, and the reading begins by mentioning the names of Allah, Rahman and Rahim together known as basmala. Consequently,

It must never rest beneath other books, but always on top of them, one must never drink or smoke when it is being read aloud, and it must be listened to in silence. It is a talisman against disease and disaster.[167][169]

According to Islam, the Quran is the word of God (Kalām Allāh). Its nature and whether it was created became a matter of fierce debate among religious scholars;[170][171] and with the involvement of the political authority in the discussions, some Muslim religious scholars who stood against the political stance faced religious persecution during the caliph al-Ma'mun period and the following years.

Muslims believe that the present Quranic text corresponds to that revealed to Muhammad, and according to their interpretation of Quran 15:9, it is protected from corruption ("Indeed, it is We who sent down the Quran and indeed, We will be its guardians").[172] Muslims consider the Quran to be a sign of the prophethood of Muhammad and the truth of the religion. For this reason, in traditional Islamic societies, great importance was given to children memorizing the Quran, and those who memorized the entire Quran were honored with the title of hafiz. Even today, millions of Muslims frequently refer to the Quran to justify their actions and desires",[p] and see it as the source of scientific knowledge,[174] though some refer to it as weird or pseudoscience.[175]

Muslims believe the Quran to be God's literal words,[16] a complete code of life,[176] the final revelation to humanity, a work of divine guidance revealed to Muhammad through the angel Gabriel.[25][177][178][179] On the other hand it is believed in Muslim community that full understanding of it can only be possible with the depths obtained in the basic and religious sciences that the ulema (imams in shia[180]) might access, as "heirs of the prophets".[181] For this reason, direct reading of the Quran or applications based on its literal translations are considered problematic except for some groups such as Quranists thinking that the Quran is a complete and clear book;[182] and tafsir / fiqh are brought fore to correct understandings in it. With a classical approach, scholars will discuss verses of the Qur'an in context called asbab al-nuzul in islamic literature, as well as language and linguistics; will pass it through filters such as muhkam and mutashabih, nasıkh and abrogated; will open the closed expressions and try to guide the believers. There is no standardization in Qur'an translations,[183] and interpretations range from traditional scholastic, to literalist-salafist understandings to esoteric-sufist, to modern and secular exegesis according to the personal scientific depth and tendencies of scholars.[184]

Inimitability

In Islam, ’i‘jāz (Arabic: اَلْإِعْجَازُ), "inimitability challenge" of the Qur'an in sense of feṣāḥa and belagha (both eloquence and rhetoric) is the doctrine which holds that the Qur’ān has a miraculous quality, both in content and in form, that no human speech can match.[185] According to this, the Qur'an is a miracle and its inimitability is the proof granted to Muhammad in authentication of his prophetic status.[186] The literary quality of the Qur'an has been praised by Muslim scholars and by many non-Muslim scholars.[187] The doctrine of the miraculousness of the Quran is further emphasized by Muhammad's illiteracy since the unlettered prophet could not have been suspected of composing the Quran.[188]

The Quran is widely regarded as the finest work in Arabic literature.[189][190][191] The emergence of the Qur’ān was an oral and aural poetic[192] experience; the aesthetic experience of reciting and hearing the Qur’ān is often regarded as one of the main reasons behind conversion to Islam in the early days.[193] In pre-Islamic Arabs, poetry was an element of challenge, propaganda and warfare,[194] and those who incapacitated their opponents from doing the same in feṣāḥa and belagha socially honored, as could be seen on Mu'allaqat poets. The etymology of the word “shā'ir; (poet)” connotes the meaning of a man of inspirational knowledge, of unseen powers. `To the early Arabs poetry was ṣihr ḥalāl and the poet was a genius who had supernatural communications with the jinn or spirits, the muses who inspired him.’[193] Although pre-Islamic Arabs gave poets status associated with suprahuman beings, soothsayers and prophecies were seen as persons of lower status. Contrary to later hurufic and recent scientific prophecy claims, traditional miracle statements about the Quran hadn't focused on prophecies, with a few exceptions like the Byzantine victory over the Persians[195] in wars that continued for hundreds of years with mutual victories and defeats.

The first works about the ’i‘jāz of the Quran began to appear in the 9th century in the Mu'tazila circles, which emphasized only its literary aspect, and were adopted by other religious groups.[196] According to grammarian Ar-Rummani the eloquence contained in the Quran consisted of tashbīh, istiʿāra, taǧānus, mubālaġa, concision, clarity of speech (bayān), and talāʾum. He also added other features developed by himself; the free variation of themes (taṣrīf al-maʿānī), the implication content (taḍmīn) of the expressions and the rhyming closures (fawāṣil).[197] The most famous works on the doctrine of inimitability are two medieval books by the grammarian Al Jurjani (d. 1078 CE), Dala’il al-i'jaz ('the Arguments of Inimitability') and Asraral-balagha ('the Secrets of Eloquence').[198] Al Jurjani believed that Qur'an's eloquence must be a certain special quality in the manner of its stylistic arrangement and composition or a certain special way of joining words.[188] Angelika Neuwirth lists the factors that led to the emergence of the doctrine of ’i‘jāz: The necessity of explaining some challenging verses in the Quran;[199] In the context of the emergence of the theory of "proofs of prophecy" (dâ'il an-nubuwwa) in Islamic theology, proving that the Quran is a work worthy of the emphasized superior place of Muhammad in the history of the prophets, thus gaining polemical superiority over Jews and Christians; Preservation of Arab national pride in the face of confrontation with the Iranian Shu'ubiyya movement, etc.[200]

In a different line; The miracle claim that the Quran was encrypted using the number 19 was put forward by Rashad Khalifa; The claim attracted criticism because it included claims against the integrity of the text, which is mostly accepted by Muslims,[201][q] and the Khalifa was killed by his own student in an assassination[202] possibly organized by a Sunni radical group.[203]

In worship

Surah Al-Fatiha, the first chapter of the Quran, is recited in full in every rakat of salah and on other occasions. This surah, which consists of seven verses, is the most often recited surah of the Quran:[16]

بِسْمِ ٱللَّهِ ٱلرَّحْمَٰنِ ٱلرَّحِيمِ | In the Name of Allah the Entirely Merciful, the Especially Merciful. |

| —Quran 1:1-7 | —Sahih International English translation |

Other sections of the Quran of choice are also read in daily prayers. Surah Al-Ikhlāṣ is second in frequency of Qur'an recitation, for according to many early authorities, Muhammad said that Ikhlāṣ is equivalent to one-third of the whole Quran.[204]

قُلۡ هُوَ ٱللَّهُ أَحَدٌ | Say, ˹O Prophet,˺ “He is God—One ˹and Indivisible˺; |

| —Surah Al-Ikhlāṣ 112:1-4 | —The Clear Quran English translation |

Respect for the written text of the Quran is an important element of religious faith by many Muslims, and the Quran is treated with reverence. Based on tradition and a literal interpretation of Quran 56:79 ("none shall touch but those who are clean"), some Muslims believe that they must perform a ritual cleansing with water (wudu or ghusl) before touching a copy of the Quran, although this view is not universal.[16] Worn-out copies of the Quran are wrapped in a cloth and stored indefinitely in a safe place, buried in a mosque or a Muslim cemetery, or burned and the ashes buried or scattered over water.[205] While praying, the Quran is only recited in Arabic.[206]

In Islam, most intellectual disciplines, including Islamic theology, philosophy, mysticism and jurisprudence, have been concerned with the Quran or have their foundation in its teachings.[16] Muslims believe that the preaching or reading of the Quran is rewarded with divine rewards variously called ajr, thawab, or hasanat.[207]

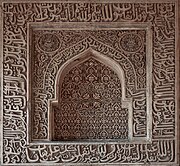

In Islamic art

The Quran also inspired Islamic arts and specifically the so-called Quranic arts of calligraphy and illumination.[16] The Quran is never decorated with figurative images, but many Qurans have been highly decorated with decorative patterns in the margins of the page, or between the lines or at the start of suras. Islamic verses appear in many other media, on buildings and on objects of all sizes, such as mosque lamps, metal work, pottery and single pages of calligraphy for muraqqas or albums.

- Calligraphy, 18th century, Brooklyn Museum

- Quranic inscriptions, Bara Gumbad mosque, Delhi, India

- Quran page decoration art, Ottoman period

- Quranic verses, Shahizinda mausoleum, Samarkand, Uzbekistan

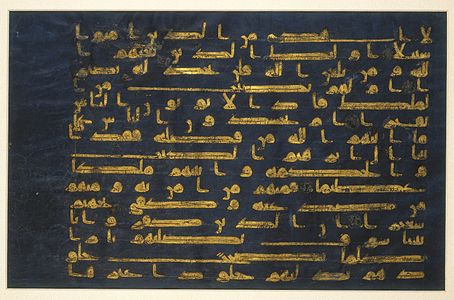

- The leaves from Quran written in gold and contoured with brown ink with a horizontal format suited to classical Kufic calligraphy, which became common under the early Abbasid caliphs.

Interpretation

The Quran has sparked much commentary and explication (tafsir), aimed at explaining the "meanings of the Quranic verses, clarifying their import and finding out their significance."[208]

Tafsir is one of the earliest academic activities of Muslims. According to the Quran, Muhammad was the first person who described the meanings of verses for early Muslims.[209] Other early exegetes included the first four caliphs Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Ali along with a number of Muhammad's companions including Abd Allah ibn al-Abbas, Abd Allah ibn Mas'ud, Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr, Abu Musa al-Ash'ari, Ubayy ibn Ka'b and Zayd ibn Thabit.[210] Exegesis in those days was confined to the explanation of literary aspects of the verse, the background of its revelation and, occasionally, interpretation of one verse with the help of the other. If the verse was about a historical event, then sometimes a few traditions (hadith) of Muhammad were narrated to make its meaning clear.[208]

Because the Quran is spoken in classical Arabic, many of the later converts to Islam (mostly non-Arabs) did not always understand the Quranic Arabic, they did not catch allusions that were clear to early Muslims fluent in Arabic and they were concerned with reconciling apparent conflict of themes in the Quran. Commentators erudite in Arabic explained the allusions, and perhaps most importantly, explained which Quranic verses had been revealed early in Muhammad's prophetic career, as being appropriate to the very earliest Muslim community, and which had been revealed later, canceling out or "abrogating" (nāsikh) the earlier text (mansūkh).[211][212] Other scholars, however, maintain that no abrogation has taken place in the Quran.[213]

There have been several commentaries of the Quran by scholars of all denominations, popular ones include Tafsir Ibn Kathir, Tafsir al-Jalalayn, Tafsir Al Kabir, Tafsir al-Tabari. More modern works of Tafsir include Ma'ariful Qur'an written by Mufti Muhammad Shafi and Risale-i Nur by Bediüzzaman Said Nursi.

Esoteric interpretation

Esoteric or Sufi interpretation attempts to unveil the inner meanings of the Quran. Sufism moves beyond the apparent (zahir) point of the verses and instead relates Quranic verses to the inner or esoteric (batin) and metaphysical dimensions of consciousness and existence.[214] According to Sands, esoteric interpretations are more suggestive than declarative, they are allusions (isharat) rather than explanations (tafsir). They indicate possibilities as much as they demonstrate the insights of each writer.[215]

Sufi interpretation, according to Annabel Keeler, also exemplifies the use of the theme of love, as for instance can be seen in Qushayri's interpretation of the Quran:

When Moses came at the appointed time and his Lord spoke to him, he asked, "My Lord! Reveal Yourself to me so I may see You." Allah answered, "You cannot see Me! But look at the mountain. If it remains firm in its place, only then will you see Me." When his Lord appeared to the mountain, He levelled it to dust and Moses collapsed unconscious. When he recovered, he cried, "Glory be to You! I turn to You in repentance and I am the first of the believers."

— Quran 7:143

Moses, in 7:143, comes the way of those who are in love, he asks for a vision but his desire is denied, he is made to suffer by being commanded to look at other than the Beloved while the mountain is able to see God. The mountain crumbles and Moses faints at the sight of God's manifestation upon the mountain. In Qushayri's words, Moses came like thousands of men who traveled great distances, and there was nothing left to Moses of Moses. In that state of annihilation from himself, Moses was granted the unveiling of the realities. From the Sufi point of view, God is the always the beloved and the wayfarer's longing and suffering lead to realization of the truths.[216]

Muhammad Husayn Tabataba'i says that according to the popular explanation among the later exegetes, ta'wil indicates the particular meaning a verse is directed towards. The meaning of revelation (tanzil), as opposed to ta'wil, is clear in its accordance to the obvious meaning of the words as they were revealed. But this explanation has become so widespread that, at present, it has become the primary meaning of ta'wil, which originally meant 'to return' or 'the returning place'. In Tabatabaei's view, what has been rightly called ta'wil, or hermeneutic interpretation of the Quran, is not concerned simply with the denotation of words. Rather, it is concerned with certain truths and realities that transcend the comprehension of the common run of men; yet it is from these truths and realities that the principles of doctrine and the practical injunctions of the Quran issue forth. Interpretation is not the meaning of the verse—rather it transpires through that meaning, in a special sort of transpiration. There is a spiritual reality—which is the main objective of ordaining a law, or the basic aim in describing a divine attribute—and then there is an actual significance that a Quranic story refers to.[217][218]

According to Shia beliefs, those who are firmly rooted in knowledge like Muhammad and the imams know the secrets of the Quran. According to Tabatabaei, the statement "none knows its interpretation except God" remains valid, without any opposing or qualifying clause.[219] Therefore, so far as this verse is concerned, the knowledge of the Quran's interpretation is reserved for God. But Tabatabaei uses other verses and concludes that those who are purified by God know the interpretation of the Quran to a certain extent.[218]

According to Tabatabaei, there are acceptable and unacceptable esoteric interpretations. Acceptable ta'wil refers to the meaning of a verse beyond its literal meaning; rather the implicit meaning, which ultimately is known only to God and can not be comprehended directly through human thought alone. The verses in question here refer to the human qualities of coming, going, sitting, satisfaction, anger and sorrow, which are apparently attributed to God. Unacceptable ta'wil is where one "transfers" the apparent meaning of a verse to a different meaning by means of a proof; this method is not without obvious inconsistencies. Although this unacceptable ta'wil has gained considerable acceptance, it is incorrect and cannot be applied to the Quranic verses. The correct interpretation is that reality a verse refers to. It is found in all verses, the decisive and the ambiguous alike; it is not a sort of a meaning of the word; it is a fact that is too sublime for words. God has dressed them with words to bring them a bit nearer to our minds; in this respect they are like proverbs that are used to create a picture in the mind, and thus help the hearer to clearly grasp the intended idea.[218][220]

History of Sufi commentaries

One of the notable authors of esoteric interpretation prior to the 12th century is Sulami (d. 1021) without whose work the majority of very early Sufi commentaries would not have been preserved. Sulami's major commentary is a book named Haqaiq al-Tafsir ('Truths of Exegesis') which is a compilation of commentaries of earlier Sufis. From the 11th century onwards several other works appear, including commentaries by Qushayri (d. 1074), Daylami (d. 1193), Shirazi (d. 1209) and Suhrawardi (d. 1234). These works include material from Sulami's books plus the author's contributions. Many works are written in Persian such as the works of Maybudi (d. 1135) kashf al-asrar ('the unveiling of the secrets').[214] Rumi (d. 1273) wrote a vast amount of mystical poetry in his book Mathnawi. Rumi makes heavy use of the Quran in his poetry, a feature that is sometimes omitted in translations of Rumi's work. A large number of Quranic passages can be found in Mathnawi, which some consider a kind of Sufi interpretation of the Quran. Rumi's book is not exceptional for containing citations from and elaboration on the Quran, however, Rumi does mention Quran more frequently.[221] Simnani (d. 1336) wrote two influential works of esoteric exegesis on the Quran. He reconciled notions of God's manifestation through and in the physical world with the sentiments of Sunni Islam.[222] Comprehensive Sufi commentaries appear in the 18th century such as the work of Ismail Hakki Bursevi (d. 1725). His work ruh al-Bayan ('the Spirit of Elucidation') is a voluminous exegesis. Written in Arabic, it combines the author's own ideas with those of his predecessors (notably Ibn Arabi and Ghazali).[222]

Levels of meaning

Unlike the Salafis, Shias and Sunnis as well as some other Muslim philosophers believe the meaning of the Quran is not restricted to the literal aspect.[223]: 7 For them, it is an essential idea that the Quran also has inward aspects. Henry Corbin narrates a hadith that goes back to Muhammad:

The Quran possesses an external appearance and a hidden depth, an exoteric meaning and an esoteric meaning. This esoteric meaning in turn conceals an esoteric meaning (this depth possesses a depth, after the image of the celestial Spheres, which are enclosed within each other). So it goes on for seven esoteric meanings (seven depths of hidden depth).[223]: 7

According to this view, it has also become evident that the inner meaning of the Quran does not eradicate or invalidate its outward meaning. Rather, it is like the soul, which gives life to the body.[224] Corbin considers the Quran to play a part in Islamic philosophy, because gnosiology itself goes hand in hand with prophetology.[223]: 13

Commentaries dealing with the zahir ('outward aspects') of the text are called tafsir, and hermeneutic and esoteric commentaries dealing with the batin are called ta'wil ('interpretation' or 'explanation'), which involves taking the text back to its beginning. Commentators with an esoteric slant believe that the ultimate meaning of the Quran is known only to God.[16] In contrast, Quranic literalism, followed by Salafis and Zahiris, is the belief that the Quran should only be taken at its apparent meaning.[225][226]

Reappropriation

Reappropriation is the name of the hermeneutical style of some ex-Muslims who have converted to Christianity. Their style or reinterpretation can sometimes be geared towards apologetics, with less reference to the Islamic scholarly tradition that contextualizes and systematizes the reading (e.g., by identifying some verses as abrogated). This tradition of interpretation draws on the following practices: grammatical renegotiation, renegotiation of textual preference, retrieval, and concession.[227]

Translations

Translating the Quran has always been problematic and difficult. Many argue that the Quranic text cannot be reproduced in another language or form.[228] Furthermore, an Arabic word may have a range of meanings depending on the context, making an accurate translation even more difficult.[229]

Nevertheless, the Quran has been translated into most African, Asian, and European languages.[60] The first translator of the Quran was Salman the Persian, who translated surat al-Fatiha into Persian during the seventh century.[230] Another translation of the Quran was completed in 884 in Alwar (Sindh, India, now Pakistan) by the orders of Abdullah bin Umar bin Abdul Aziz on the request of the Hindu Raja Mehruk.[231]

The first fully attested complete translations of the Quran were done between the 10th and 12th centuries in Persian. The Samanid king, Mansur I (961–976), ordered a group of scholars from Khorasan to translate the Tafsir al-Tabari, originally in Arabic, into Persian. Later in the 11th century, one of the students of Abu Mansur Abdullah al-Ansari wrote a complete tafsir of the Quran in Persian. In the 12th century, Najm al-Din Abu Hafs al-Nasafi translated the Quran into Persian.[232] The manuscripts of all three books have survived and have been published several times.[citation needed]

Islamic tradition also holds that translations were made for Emperor Negus of Abyssinia and Byzantine Emperor Heraclius, as both received letters by Muhammad containing verses from the Quran.[229] In early centuries, the permissibility of translations was not an issue, but whether one could use translations in prayer.[citation needed]

In 1936, translations in 102 languages were known.[229] In 2010, the Hürriyet Daily News and Economic Review reported that the Quran was presented in 112 languages at the 18th International Quran Exhibition in Tehran.[233]

Robert of Ketton's 1143 translation of the Quran for Peter the Venerable, Lex Mahumet pseudoprophete, was the first into a Western language (Latin).[234]Alexander Ross offered the first English version in 1649, from the French translation of L'Alcoran de Mahomet (1647) by Andre du Ryer. In 1734, George Sale produced the first scholarly translation of the Quran into English; another was produced by Richard Bell in 1937, and yet another by Arthur John Arberry in 1955. All these translators were non-Muslims. There have been numerous translations by Muslims. Popular modern English translations by Muslims include The Oxford World Classic's translation by Muhammad Abdel Haleem, The Clear Quran by Mustafa Khattab, Sahih International's translation, among various others.

As with translations of the Bible, the English translators have sometimes favored archaic English words and constructions over their more modern or conventional equivalents; for example, two widely read translators, Abdullah Yusuf Ali and Marmaduke Pickthall, use the plural and singular ye and thou instead of the more common you.[235]

The oldest Gurmukhi translation of the Quran Sharif has been found in village Lande of Moga district of Punjab which was printed in 1911.[236]

- 1091 Quranic text in bold script with Persian translation and commentary in a lighter script[237]

- Arabic Quran with interlinear Persian translation from the Ilkhanid Era

- The first printed Quran in a European vernacular language: L'Alcoran de Mahomet, André du Ryer, 1647

- Title page of the first German translation (1772) of the Quran

- Verses 33 and 34 of surat Yā Sīn in this Chinese translation of the Quran

Recitation

Rules of recitation

The proper recitation of the Quran is the subject of a separate discipline named tajwid which determines in detail how the Quran should be recited, how each individual syllable is to be pronounced, the need to pay attention to the places where there should be a pause, to elisions, where the pronunciation should be long or short, where letters should be sounded together and where they should be kept separate, etc. It may be said that this discipline studies the laws and methods of the proper recitation of the Quran and covers three main areas: the proper pronunciation of consonants and vowels (the articulation of the Quranic phonemes), the rules of pause in recitation and of resumption of recitation, and the musical and melodious features of recitation.[238]

In order to avoid incorrect pronunciation, reciters follow a program of training with a qualified teacher. The two most popular texts used as references for tajwid rules are Matn al-Jazariyyah by Ibn al-Jazari[239] and Tuhfat al-Atfal by Sulayman al-Jamzuri.

The recitations of a few Egyptian reciters, like El Minshawy, Al-Hussary, Abdul Basit, Mustafa Ismail, were highly influential in the development of current styles of recitation.[240][241][242]: 83 Southeast Asia is well known for world-class recitation, evidenced in the popularity of the woman reciters such as Maria Ulfah of Jakarta.[238] Today, crowds fill auditoriums for public Quran recitation competitions.[243][191]

There are two types of recitation:

- Murattal is at a slower pace, used for study and practice.

- Mujawwad refers to a slow recitation that deploys heightened technical artistry and melodic modulation, as in public performances by trained experts. It is directed to and dependent upon an audience for the mujawwad reciter seeks to involve the listeners.[244]

Variant readings

Vocalization markers indicating specific vowel sounds (tashkeel) were introduced into the text of the Qur'an during the lifetimes of the last Sahabah.[245] The first Quranic manuscripts lacked these marks, enabling multiple possible recitations to be conveyed by the same written text. The 10th-century Muslim scholar from Baghdad, Ibn Mujāhid, is famous for establishing seven acceptable textual readings of the Quran. He studied various readings and their trustworthiness and chose seven 8th-century readers from the cities of Mecca, Medina, Kufa, Basra and Damascus. Ibn Mujahid did not explain why he chose seven readers, rather than six or ten, but this may be related to a prophetic tradition (Muhammad's saying) reporting that the Quran had been revealed in seven ahruf (meaning seven letters or modes). Today, the most popular readings are those transmitted by Ḥafṣ (d. 796) and Warsh (d. 812) which are according to two of Ibn Mujahid's reciters, Aasim ibn Abi al-Najud (Kufa, d. 745) and Nafi' al-Madani (Medina, d. 785), respectively. The influential standard Quran of Cairo uses an elaborate system of modified vowel-signs and a set of additional symbols for minute details and is based on ʻAsim's recitation, the 8th-century recitation of Kufa. This edition has become the standard for modern printings of the Quran.[45][65]

The variant readings of the Quran are one type of textual variant.[246][247] According to Melchert (2008), the majority of disagreements have to do with vowels to supply, most of them in turn not conceivably reflecting dialectal differences and about one in eight disagreements has to do with whether to place dots above or below the line.[248]

Nasser categorizes variant readings into various subtypes, including internal vowels, long vowels, gemination (shaddah), assimilation and alternation.[249]

Occasionally, an early Quran shows compatibility with a particular reading. A Syrian manuscript from the 8th century is shown to have been written according to the reading of Ibn Amir ad-Dimashqi.[250] Another study suggests that this manuscript bears the vocalization of himsi region.[251]

Writing and printing

Writing

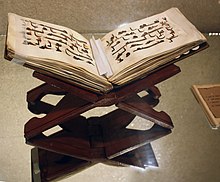

Before printing was widely adopted in the 19th century, the Quran was transmitted in manuscripts made by calligraphers and copyists. The earliest manuscripts were written in Ḥijāzī-typescript. The Hijazi style manuscripts nevertheless confirm that transmission of the Quran in writing began at an early stage. Probably in the ninth century, scripts began to feature thicker strokes, which are traditionally known as Kufic scripts. Toward the end of the ninth century, new scripts began to appear in copies of the Quran and replace earlier scripts. The reason for discontinuation in the use of the earlier style was that it took too long to produce and the demand for copies was increasing. Copyists would therefore choose simpler writing styles. Beginning in the 11th century, the styles of writing employed were primarily the naskh, muhaqqaq, rayḥānī and, on rarer occasions, the thuluth script. Naskh was in very widespread use. In North Africa and Iberia, the Maghribī style was popular. More distinct is the Bihari script which was used solely in the north of India. Nastaʻlīq style was also rarely used in Persian world.[252][253]

In the beginning, the Quran was not written with dots or tashkeel. These features were added to the text during the lifetimes of the last of the Sahabah.[245] Since it would have been too costly for most Muslims to purchase a manuscript, copies of the Quran were held in mosques in order to make them accessible to people. These copies frequently took the form of a series of 30 parts or juzʼ. In terms of productivity, the Ottoman copyists provide the best example. This was in response to widespread demand, unpopularity of printing methods and for aesthetic reasons.[254][255]

Whilst the majority of Islamic scribes were men, some women also worked as scholars and copyists; one such woman who made a copy of this text was the Moroccan jurist, Amina, bint al-Hajj ʿAbd al-Latif.[256]

- Folio from the "Blue" Quran at the Brooklyn Museum

- Kufic script, eighth or ninth century

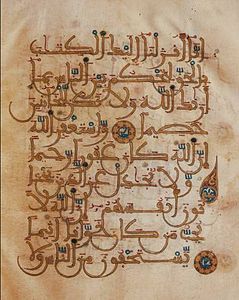

- Maghribi script, 13th–14th centuries

- Muhaqqaq script, 14th–15th centuries

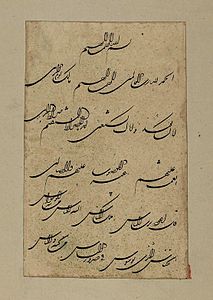

- Shikasta nastaliq script, 18th–19th centuries

Printing

Wood-block printing of extracts from the Quran is on record as early as the 10th century.[257]

Arabic movable type printing was ordered by Pope Julius II (r. 1503–1512) for distribution among Middle Eastern Christians.[258] The first complete Quran printed with movable type was produced in Venice in 1537–1538 for the Ottoman market by Paganino Paganini and Alessandro Paganini.[259][260] But this Quran was not used as it contained a large number of errors.[261] Two more editions include the Hinckelmann edition published by the pastor Abraham Hinckelmann in Hamburg in 1694,[262] and the edition by the Italian priest Ludovico Maracci in Padua in 1698 with Latin translation and commentary.[263]

Printed copies of the Quran during this period met with strong opposition from Muslim legal scholars: printing anything in Arabic was prohibited in the Ottoman empire between 1483 and 1726—initially, even on penalty of death.[264][255][265] The Ottoman ban on printing in Arabic script was lifted in 1726 for non-religious texts only upon the request of Ibrahim Muteferrika, who printed his first book in 1729. Except for books in Hebrew and European languages, which were unrestricted, very few books, and no religious texts, were printed in the Ottoman Empire for another century.[r]

In 1786, Catherine the Great of Russia, sponsored a printing press for "Tatar and Turkish orthography" in Saint Petersburg, with one Mullah Osman Ismail responsible for producing the Arabic types. A Quran was printed with this press in 1787, reprinted in 1790 and 1793 in Saint Petersburg, and in 1803 in Kazan.[s] The first edition printed in Iran appeared in Tehran (1828), a translation in Turkish was printed in Cairo in 1842, and the first officially sanctioned Ottoman edition was finally printed in Constantinople between 1875 and 1877 as a two-volume set, during the First Constitutional Era.[268][269]

Gustav Flügel published an edition of the Quran in 1834 in Leipzig, which remained authoritative in Europe for close to a century, until Cairo's Al-Azhar University published an edition of the Quran in 1924. This edition was the result of a long preparation, as it standardized Quranic orthography, and it remains the basis of later editions.[252]

Criticism

Regarding the claim of divine origin, critics refer to preexisting sources, not only taken from the Bible, supposed to be older revelations of God, but also from heretic, apocryphic and talmudic sources, such as the Syriac Infancy Gospel and Gospel of James. The Quran acknowledges that accusations of borrowing popular ancient fables were being made against Muhammad.[270] Due to its rejection of the Crucifixion of Jesus, some scholars also suspect influences by Manichaeaism, a dualistic religion believing in two eternal forces, on the Quran.

The Chinese government has banned Quran mobile apps.[271]

Relationship with other literature

Historical region: Uzbekistan

Some non-Muslim groups such as the Baháʼí Faith and Druze view the Quran as holy. In the Baháʼí Faith, the Quran is accepted as authentic revelation from God along with the revelations of the other world religions, Islam being a stage within the divine process of progressive revelation. Bahá'u'lláh, the Prophet-Founder of the Baháʼí Faith, testified to the validity of the Quran, writing, say: "Perused ye not the Qur'án? Read it, that haply ye may find the Truth, for this Book is verily the Straight Path. This is the Way of God unto all who are in the heavens and all who are on the earth."[272] Unitarian Universalists may also seek inspiration from the Quran. It has been suggested that the Quran has some narrative similarities to the Diatessaron, Protoevangelium of James, Infancy Gospel of Thomas, Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew and the Arabic Infancy Gospel.[273][274] One scholar has suggested that the Diatessaron, as a gospel harmony, may have led to the conception that the Christian Gospel is one text.[275]

The Bible

He has revealed to you ˹O Prophet˺ the Book in truth, confirming what came before it, as He revealed the Torah and the Gospel previously, as a guide for people, and ˹also˺ revealed the Standard ˹to distinguish between right and wrong˺.[276]

— 3:3-4

The Quran attributes its relationship with former books (the Torah and the Gospels) to their unique origin, saying all of them have been revealed by the one God.[277]

According to Christoph Luxenberg (in The Syro-Aramaic Reading of the Koran) the Quran's language was similar to the Syriac language.[278] The Quran recounts stories of many of the people and events recounted in Jewish and Christian sacred books (Tanakh, Bible) and devotional literature (Apocrypha, Midrash), although it differs in many details. Adam, Enoch, Noah, Eber, Shelah, Abraham, Lot, Ishmael, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Job, Jethro, David, Solomon, Elijah, Elisha, Jonah, Aaron, Moses, Zechariah, John the Baptist and Jesus are mentioned in the Quran as prophets of God (see Prophets of Islam). In fact, Moses is mentioned more in the Quran than any other individual.[103] Jesus is mentioned more often in the Quran than Muhammad (by name—Muhammad is often alluded to as "The Prophet" or "The Apostle"), while Mary is mentioned in the Quran more than in the New Testament.[279]

Arab writing

After the Quran, and the general rise of Islam, the Arabic alphabet developed rapidly into an art form.[60] The Arabic grammarian Sibawayh wrote one of the earliest books on Arabic grammar, referred to as "Al-Kitab", which relied heavily on the language in the Quran. Wadad Kadi, Professor of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at University of Chicago, and Mustansir Mir, Professor of Islamic studies at Youngstown State University, state that the Quran exerted a particular influence on Arabic literature's diction, themes, metaphors, motifs and symbols and added new expressions and new meanings to old, pre-Islamic words that would become ubiquitous.[280]

See also

- Criticism of the Quran

- Historical reliability of the Quran

- List of chapters in the Quran

- List of translations of the Quran

- Quran and miracles

- Violence in the Quran

- Women in the Quran

- Quran code

- Digital Quran

- Hadith al-Thaqalayn

- Islamic schools and branches

- Quran translations

- Schools of Islamic theology

- The True Furqan

References

Notes

- ^ The English pronunciation varies: /kəˈrɑːn/, /-ˈræn/, /kɔː-/, /koʊ-/;[1] especially with the spelling quran /kʊrˈɑːn/, /-ˈræn/;[2] especially in British English /kɒrˈɑːn/.[3][4]

- ^ The Arabic pronunciation can be transcribed phonemically as /al.qurˈʔaːn/. The actual pronunciation in Literary Arabic varies regionally. The first vowel varies from [o] to [ʊ], while the second vowel varies from [æ] to [a] to [ɑ]. For example, the pronunciation in Egypt is [qorˈʔɑːn] and in Central East Arabia [qʊrˈʔæːn].

- ^ /kʊrˈɑːn/, kuurr-AHN;[a] vocalized Arabic: ٱلْقُرْآن, Quranic Arabic: ٱلۡقُرۡءَان, al-Qurʾān [alqurˈʔaːn],[b] lit. 'the recitation' or 'the lecture'

- ^ (English spelling) The form Alcoran (and its variants) was usual before the 19th century when it became obsolete.[5][6] The form Koran was most predominant from the second half of the 18th century till the 1980s, when it has been superseded by either Qur'an or Quran.[6][7][8][9] Other transliterations include al-Coran, Coran, Kuran and al-Qur'an. The adjectives vary as well and include Koranic, Quranic and Qur'anic (sometimes in lowercase).[10]

- ^ According to Welch in the Encyclopedia of Islam, the verses pertaining to the usage of the word hikma should probably be interpreted in the light of IV, 105, where it is said that "Muhammad is to judge (tahkum) mankind on the basis of the Book sent down to him."

- ^ Hadith are primarily from Muhammad but some are from those closest to him. Muslim scholars have worked carefully to authenticate them; see Hadith studies#Evaluating authenticity.

- ^ "God's Apostle replied, 'Sometimes it is (revealed) like the ringing of a bell, this form of Inspiration is the hardest of all and then this state passes off after I have grasped what is inspired. Sometimes the Angel comes in the form of a man and talks to me and I grasp whatever he says.' ʻAisha added: Verily I saw the Prophet being inspired Divinely on a very cold day and noticed the Sweat dropping from his forehead (as the Inspiration was over)."[31]

- ^ "Few have failed to be convinced that … the Quran is … the words of Muhammad, perhaps even dictated by him after their recitation."[48]

- ^ There is some disagreement among early Muslim sources disagree over who was the first to collect the narrations. At least one source credits Salim, the freed slave of Abu Hudhaifah with collecting the Qur'an into a mushaf: "It is reported... from Ibn Buraidah who said:

Первым из тех, кто собрал Коран в мусхаф ( кодекс ), был Салим, освобожденный раб Абу Хузайфы . [49]

- ^ Например:

- «Мы, несомненно, ниспослали Послание, и Мы несомненно сохраним его (от искажения)» (15:9)

- Среди вещей, которые делают Коран «чудом и дополняют идею или веру в то, что ислам является истинной религией. Эта уникальная особенность Корана — его защищенный характер, где не было ни единого изменения в слоге, в котором он был ниспослан. В строках ниже обсуждается, как защищенный характер Корана является доказательством того, что ислам является истинной божественной верой.