исламизм

| Часть серии о исламизм |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

Исламизм (также часто называемый политическим исламом ) — религиозно-политическая идеология. Сторонники исламизма, также известные как «аль-Исламийюн», стремятся реализовать свою идеологическую интерпретацию ислама в контексте государства или общества. Большинство из них связаны с исламскими институтами или движениями социальной мобилизации, часто называемыми «аль-харакат аль-исламия». [1] Исламисты подчеркивают соблюдение шариата , [2] панисламское политическое единство, [2] создание исламских государств , [3] (в конечном итоге объединенные) и отказ от немусульманского влияния, особенно западного или универсального экономического, военного, политического, социального или культурного.

В своей первоначальной формулировке исламизм описывал идеологию, стремящуюся возродить ислам к его былой напористости и славе. [4] очистка его от иностранных элементов, восстановление его роли в «социальной и политической, а также личной жизни»; [5] и в частности «переустройство правительства и общества в соответствии с законами, предписанными исламом» (т.е. шариатом). [6] [7] [8] [9] According to at least one observer (author Robin Wright), Islamist movements have "arguably altered the Middle East more than any trend since the modern states gained independence", redefining "politics and even borders".[10]

Central and prominent figures in 20th-century Islamism include Sayyid Rashid Riḍā,[11] Hassan al-Banna (founder of the Muslim Brotherhood), Sayyid Qutb, Abul A'la Maududi,[12] Ruhollah Khomeini (founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran), Hassan Al-Turabi.[13] Syrian Sunni cleric Muhammad Rashid Riḍā, a fervent opponent of Westernization, Zionism and nationalism, advocated Sunni internationalism through revolutionary restoration of a pan-Islamic Caliphate to politically unite the Muslim world.[14][15] Riḍā was a strong exponent of Islamic vanguardism, the belief that Muslim community should be guided by clerical elites (ulema) who steered the efforts for religious education and Islamic revival.[16] Riḍā's Salafi-Arabist synthesis and Islamist ideals greatly influenced his disciples like Hasan al-Banna,[17][18] an Egyptian schoolteacher who founded the Muslim Brotherhood movement, and Hajji Amin al-Husayni, the anti-Zionist Grand Mufti of Jerusalem.[19]

Al-Banna and Maududi called for a "reformist" strategy to re-Islamizing society through grassroots social and political activism.[20][21] Other Islamists (Al-Turabi) are proponents of a "revolutionary" strategy of Islamizing society through exercise of state power,[20] or (Sayyid Qutb) for combining grassroots Islamization with armed revolution. The term has been applied to non-state reform movements, political parties, militias and revolutionary groups.[22]

At least one author (Graham E. Fuller) has argued for a broader notion of Islamism as a form of identity politics, involving "support for [Muslim] identity, authenticity, broader regionalism, revivalism, [and] revitalization of the community."[23] Islamists themselves prefer terms such as "Islamic movement",[24] or "Islamic activism" to "Islamism", objecting to the insinuation that Islamism is anything other than Islam renewed and revived.[25] In public and academic contexts,[26] the term "Islamism" has been criticized as having been given connotations of violence, extremism, and violations of human rights, by the Western mass media, leading to Islamophobia and stereotyping.[27]

Following the Arab Spring, many post-Islamist currents became heavily involved in democratic politics,[10][28] while others spawned "the most aggressive and ambitious Islamist militia" to date, such as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).[10]

Terminology[edit]

Originally the term Islamism was simply used to mean the religion of Islam, not an ideology or movement. It first appeared in the English language as Islamismus in 1696, and as Islamism in 1712.[29] The term appears in the U.S. Supreme Court decision in In Re Ross (1891). By the turn of the twentieth century the shorter and purely Arabic term "Islam" had begun to displace it, and by 1938, when Orientalist scholars completed The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Islamism seems to have virtually disappeared from English usage.[citation needed] The term remained "practically absent from the vocabulary" of scholars, writers or journalists until the Iranian Islamic Revolution of 1978–79, which brought Ayatollah Khomeini's concept of "Islamic government" to Iran.[30]

This new usage appeared without taking into consideration how the term Islamist (m. sing.: Islami, pl. nom/acc: Islamiyyun, gen. Islamiyyin; f. sing/pl: Islamiyyah) was already being used in traditional Arabic scholarship in a theological sense as in relating to the religion of Islam, not a political ideology. In heresiographical, theological and historical works, such as al-Ash'ari's well-known encyclopaedia Maqālāt al-Islāmiyyīn (The Opinions of The Islamists), an Islamist refers to any person who attributes himself to Islam without affirming nor negating that attribution. If used consistently, it is for impartiality, but if used in reference to a certain person or group in particular without others, it implies that the author is either unsure whether to affirm or negate their attribution to Islam, or trying to insinuate his disapproval of the attribution without controversy.[31][32][33][34][35] In contrast, referring to a person as a Muslim or a Kafir implies an explicit affirmation or a negation of that person's attribution to Islam. To evade the problem resulting from the confusion between the Western and Arabic usage of the term Islamist, Arab journalists invented the term Islamawi (Islamian) instead of Islami (Islamist) in reference to the politicists, which is nonetheless sometimes criticized as being ungrammatical.[36]

Definitions[edit]

Islamism has been defined as:

- "the belief that Islam should guide social and political as well as personal life" (Sheri Berman);[5]

- the belief that Islam should influence political systems (Cambridge English Dictionary);[37]

- "the [Islamic] ideology that guides society as a whole and that [teaches] law must be in conformity with the Islamic sharia", (W. E. Shepard);[7]

- a combination of two pre-existing trends

- movements to revive the faith, weakened by "foreign influence, political opportunism, moral laxity, and the forgetting of sacred texts";[38]

- the more recent movement against imperialism/colonialism, morphed into a more simple anti-Westernism; formerly embraced by leftists and nationalists but whose supporters have turned to Islam.[38]

- a form of "religionized politics" and an instance of religious fundamentalism that imagines an Islamic community claiming global hegemony for its values (Bassam Tibi);[39]

- "political movement that favors reordering government and society in accordance with laws prescribed by Islam" (Associated Press stylebook);[6][40]

- a political ideology which seeks to enforce Islamic precepts and norms as generally applicable rules for people's conduct; and whose adherents seek a state based on Islamic values and laws (sharia) and rejecting Western guiding principles, such as freedom of opinion, freedom of the press, artistic freedom and freedom of religion (Thomas Volk);[41]

- a broad set of political ideologies that use and draw inspiration from Islamic symbols and traditions in pursuit of a sociopolitical objective—also called "political Islam" (Britannica);[42]

- "[... has become shorthand for] 'Muslims we don't like.'" (Council on American–Islamic Relations—in complaint about AP's earlier definition of Islamist);[40]

- In "Western popular discourse generally uses 'Islamism' when discussing the negative or 'that-which-is-bad' in Muslim communities. The signifier, 'Islam,' on the other hand, is reserved for the positive or neutral." (David Belt).[43]

- a movement so broad and flexible it reaches out to "everything to everyone" in Islam, making it "unsustainable" (Tarek Osman);[44]

- an alternative social provider to the poor masses;

- an angry platform for the disillusioned young;

- a loud trumpet-call announcing "a return to the pure religion" to those seeking an identity;

- a "progressive, moderate religious platform" for the affluent and liberal;

- ... and at the extremes, a violent vehicle for rejectionists and radicals.[44]

- an Islamic "movement that seeks cultural differentiation from the West and reconnection with the pre-colonial symbolic universe", (François Burgat);[4]

- "the active assertion and promotion of beliefs, prescriptions, laws or policies that are held to be Islamic in character," (International Crisis Group);[25]

- a movement of "Muslims who draw upon the belief, symbols, and language of Islam to inspire, shape, and animate political activity;" which may contain moderate, tolerant, peaceful activists or those who "preach intolerance and espouse violence", (Robert H. Pelletreau);[45]

- "All who seek to Islamize their environment, whether in relation to their lives in society, their family circumstances, or the workplace ...", (Olivier Roy).[46]

Relationship between Islam and Islamism[edit]

Islamists simply believe that their movement is either a corrected version or a revival of Islam, but others believe that Islamism is a modern deviation from Islam which should either be denounced or dismissed.

A writer for the International Crisis Group maintains that "the conception of 'political Islam'" is a creation of Americans to explain the Iranian Islamic Revolution, ignoring the fact that (according to the writer) Islam is by definition political. In fact it is quietist/non-political Islam, not Islamism, that requires explanation, which the author gives—calling it an historical fluke of the "short-lived era of the heyday of secular Arab nationalism between 1945 and 1970".[47]

Hayri Abaza argues that the failure to distinguish Islam from Islamism leads many in the West to equate the two; they think that by supporting illiberal Islamic (Islamist) regimes, they are being respectful of Islam, to the detriment of those who seek to separate religion from politics.[48]

Another source distinguishes Islamist from Islamic by emphasizing the fact that Islam "refers to a religion and culture in existence over a millennium", whereas Islamism "is a political/religious phenomenon linked to the great events of the 20th century". Islamists have, at least at times, defined themselves as "Islamiyyoun/Islamists" to differentiate themselves from "Muslimun/Muslims".[49] Daniel Pipes describes Islamism as a modern ideology that owes more to European utopian political ideologies and "isms" than to the traditional Islamic religion.[50]

According to Salman Sayyid, "Islamism is not a replacement of Islam akin to the way it could be argued that communism and fascism are secularized substitutes for Christianity." Rather, it is "a constellation of political projects that seek to position Islam in the centre of any social order".[51]

Ideology[edit]

Islamic revival[edit]

The modern revival of Islamic devotion and the attraction to things Islamic can be traced to several events.

By the end of World War I, most Muslim states were seen to be dominated by the Christian-leaning Western states. Explanations offered were: that the claims of Islam were false and the Christian or post-Christian West had finally come up with another system that was superior; or Islam had failed through not being true to itself. The second explanation being preferred by Muslims, a redoubling of faith and devotion by the faithful was called for to reverse this tide.[52]

The connection between the lack of an Islamic spirit and the lack of victory was underscored by the disastrous defeat of Arab nationalist-led armies fighting Israel under the slogan "Land, Sea and Air" in the 1967 Six-Day War, compared to the (perceived) near-victory of the Yom Kippur War six years later. In that war the military's slogan was "God is Great".[53]

Along with the Yom Kippur War came the Arab oil embargo where the (Muslim) Persian Gulf oil-producing states' dramatic decision to cut back on production and quadruple the price of oil, made the terms oil, Arabs and Islam synonymous with power throughout the world, and especially in the Muslim world's public imagination.[54] Many Muslims believe as Saudi Prince Saud al Faisal did that the hundreds of billions of dollars in wealth obtained from the Persian Gulf's huge oil deposits were nothing less than a gift from God to the Islamic faithful.[55]

As the Islamic revival gained momentum, governments such as Egypt's, which had previously repressed (and was still continuing to repress) Islamists, joined the bandwagon. They banned alcohol and flooded the airwaves with religious programming,[56] giving the movement even more exposure.

Restoration of the Caliphate[edit]

The abolition of the Ottoman Sultanate by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey on 1 November 1922 ended the Ottoman Empire, which had lasted since 1299. On 11 November 1922, at the Conference of Lausanne, the sovereignty of the Grand National Assembly exercised by the Government in Angora (now Ankara) over Turkey was recognized. The last sultan, Mehmed VI, departed the Ottoman capital, Constantinople (now Istanbul), on 17 November 1922. The legal position was solidified with the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne on 24 July 1923. In March 1924, the Caliphate was abolished legally by the Turkish National Assembly, marking the end of Ottoman influence. This shocked the Sunni clerical world, and many felt the need to present Islam not as a traditional religion but as an innovative socio-political ideology of a modern nation-state.[57]

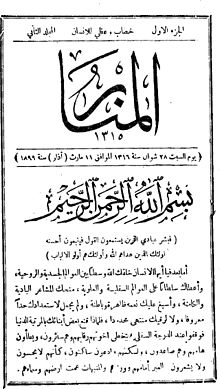

The reaction to new realities of the modern world gave birth to Islamist ideologues like Rashid Rida and Abul A'la Maududi and organizations such as Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and Majlis-e-Ahrar-ul-Islam in India. Rashid Rida, a prominent Syrian-born Salafi theologian based in Egypt, was known as a revivalist of Hadith studies in Sunni seminaries and a pioneering theoretician of Islamism in the modern age.[58] During 1922–1923, Rida published a series of articles in seminal Al-Manar magazine titled "The Caliphate or the Supreme Imamate". In this highly influential treatise, Rida advocates for the restoration of Caliphate guided by Islamic jurists and proposes gradualist measures of education, reformation and purification through the efforts of Salafiyya reform movements across the globe.[59]

Sayyid Rashid Rida had visited India in 1912 and was impressed by the Deoband and Nadwatul Ulama seminaries.[60] These seminaries carried the legacy of Sayyid Ahmad Shahid and his pre-modern Islamic emirate.[61] In British India, the Khilafat movement (1919–24) following World War I led by Shaukat Ali, Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar, Hakim Ajmal Khan and Abul Kalam Azad came to exemplify South Asian Muslims' aspirations for Caliphate.

Anti-Westernization[edit]

Muslim alienation from Western ways, including its political ways.[62]

- The memory in Muslim societies of the many centuries of "cultural and institutional success" of Islamic civilization that have created an "intense resistance to an alternative 'civilizational order'", such as Western civilization.[63]

- The proximity of the core of the Muslim world to Europe and Christendom where it first conquered and then was conquered. Iberia in the eighth century, the Crusades which began in the eleventh century, then for centuries the Ottoman Empire, were all fields of war between Europe and Islam.[64]

- In the words of Bernard Lewis:

For almost a thousand years, from the first Moorish landing in Spain to the second Turkish siege of Vienna, Europe was under constant threat from Islam. In the early centuries it was a double threat—not only of invasion and conquest, but also of conversion and assimilation. All but the easternmost provinces of the Islamic realm had been taken from Christian rulers, and the vast majority of the first Muslims west of Iran and Arabia were converts from Christianity ... Their loss was sorely felt and it heightened the fear that a similar fate was in store for Europe.[65]

- The Islamic world felt its own anger and resentment at the much more recent technological superiority of westerners who,

are the perpetual teachers; we, the perpetual students. Generation after generation, this asymmetry has generated an inferiority complex, forever exacerbated by the fact that their innovations progress at a faster pace than we can absorb them. ... The best tool to reverse the inferiority complex to a superiority complex ... Islam would give the whole culture a sense of dignity.[66]

- For Islamists, the primary threat of the West is cultural rather than political or economic. Cultural dependency robs one of faith and identity and thus destroys Islam and the Islamic community (ummah) far more effectively than political rule.[67]

- Whatever unity religious Muslims and the capitalist west felt in the face of a common atheist Communist enemy disappeared with the end of the Cold War and the end of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.[68]

Strength of identity politics[edit]

Islamism is described by Graham E. Fuller as part of identity politics, specifically the religiously oriented nationalism that emerged in the Third World in the 1970s: "resurgent Hinduism in India, Religious Zionism in Israel, militant Buddhism in Sri Lanka, resurgent Sikh nationalism in the Punjab, 'Liberation Theology' of Catholicism in Latin America, and Islamism in the Muslim world."[69]

Silencing and weakening of leftist opponents[edit]

By the late 1960s, non-Soviet Muslim-majority countries had won their independence and they tended to fall into one of the two cold-war blocs – with "Nasser's Egypt, Baathist Syria and Iraq, Muammar el-Qaddafi's Libya, Algeria under Ahmed Ben Bella and Houari Boumedienne, Southern Yemen, and Sukarno's Indonesia" aligned with Moscow.[70] Aware of the close attachment of the population with Islam, "school books of the 1960s in these countries "went out of their way to impress upon children that socialism was simply Islam properly understood."[71]Olivier Roy writes that the "failure of the 'Arab socialist' model ... left room for new protest ideologies to emerge in deconstructed societies ..."[72] Gilles Kepel notes that when a collapse in oil prices led to widespread violent and destructive rioting by the urban poor in Algeria in 1988, what might have appeared to be a natural opening for the left, was instead the beginning of major victories for the Islamist Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) party. The reason being the corruption and economic malfunction of the policies of the Third World socialist ruling party (FNL) had "largely discredited" the "vocabulary of socialism".[73]In the post-colonial era, many Muslim-majority states such as Indonesia, Egypt, Syria, and Iraq, were ruled by authoritarian regimes which were often continuously dominated by the same individuals or their cadres for decades. Simultaneously, the military played a significant part in the government decisions in many of these states (the outsized role played by the military could be seen also in democratic Turkey).[74]

The authoritarian regimes, backed by military support, took extra measures to silence leftist opposition forces, often with the help of foreign powers. Silencing of leftist opposition deprived the masses a channel to express their economic grievances and frustration toward the lack of democratic processes.[74] As a result, in the post-Cold War era, civil society-based Islamist movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood were the only organizations capable to provide avenues of protest.[74]

The dynamic was repeated after the states had gone through a democratic transition. In Indonesia, some secular political parties have contributed to the enactment of religious bylaws to counter the popularity of Islamist oppositions.[75] In Egypt, during the short period of the democratic experiment, Muslim Brotherhood seized the momentum by being the most cohesive political movement among the opposition.[76]

Influence[edit]

Few observers contest the immense influence of Islamism within the Muslim world.[77][78][79] Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, political movements based on the liberal ideology of free expression and democratic rule have led the opposition in other parts of the world such as Latin America, Eastern Europe and many parts of Asia; however "the simple fact is that political Islam currently reigns [circa 2002-3] as the most powerful ideological force across the Muslim world today".[80][81]

The strength of Islamism also draws from the strength of religiosity in general in the Muslim world. Compared to other societies around the globe, "[w]hat is striking about the Islamic world is that ... it seems to have been the least penetrated by irreligion".[82] Where other peoples may look to the physical or social sciences for answers in areas which their ancestors regarded as best left to scripture, in the Muslim world, religion has become more encompassing, not less, as "in the last few decades, it has been the fundamentalists who have increasingly represented the cutting edge" of Muslim culture.[82]

Writing in 2009, German journalist Sonja Zekri described Islamists in Egypt and other Muslim countries as "extremely influential. ... They determine how one dresses, what one eats. In these areas, they are incredibly successful. ... Even if the Islamists never come to power, they have transformed their countries."[83] Political Islamists were described as "competing in the democratic public square in places like Turkey, Tunisia, Malaysia and Indonesia".[84]

Types[edit]

Islamism is not a united movement and takes different forms and spans a wide range of strategies and tactics towards the powers in place—"destruction, opposition, collaboration, indifference"[20]—not because (or not just because) of differences of opinions, but because it varies as circumstances change.[85][86]p. 54

Moderate and reformist Islamists who accept and work within the democratic process include parties like the Tunisian Ennahda Movement. Jamaat-e-Islami of Pakistan is basically a socio-political and "vanguard party" working with in Pakistan's Democratic political process, but has also gained political influence through military coup d'états in the past.[20] Other Islamist groups like Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in Palestine participate in the democratic and political process as well as armed attacks by their powerful paramilitary wings. Jihadist organizations like al-Qaeda and the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, and groups such as the Taliban, entirely reject democracy, seeing it as a form of kufr (disbelief) calling for offensive jihad on a religious basis.

Another major division within Islamism is between what Graham E. Fuller has described as the conservative "guardians of the tradition" (Salafis, such as those in the Wahhabi movement) and the revolutionary "vanguard of change and Islamic reform" centered around the Muslim Brotherhood.[87] Olivier Roy argues that "Sunni pan-Islamism underwent a remarkable shift in the second half of the 20th century" when the Muslim Brotherhood movement and its focus on Islamisation of pan-Arabism was eclipsed by the Salafi movement with its emphasis on "sharia rather than the building of Islamic institutions".[88] Following the Arab Spring (starting in 2011), Roy has described Islamism as "increasingly interdependent" with democracy in much of the Arab Muslim world, such that "neither can now survive without the other." While Islamist political culture itself may not be democratic, Islamists need democratic elections to maintain their legitimacy. At the same time, their popularity is such that no government can call itself democratic that excludes mainstream Islamist groups.[28]

Arguing distinctions between "radical/moderate" or "violent/peaceful" Islamism were "simplistic", circa 2017, scholar Morten Valbjørn put forth these "much more sophisticated typologies" of Islamism:[86]

- resistance/revolutionary/reformist Islamism,[89]

- Islahi-Ikhwani/Jihadi-Ikhwani/Islah-salafi/Jihadi-salafi Islamism,[90]

- reformist/revolutionary/societal/spiritual Islamism,[91]

- Third Worldist/Neo-Third Worldist Islamism,[92]

- Statist/Non-Statist Islamism,[93]

- Salafist Jihadi/Ikhwani Islamism,[94] or

- mainstream/irredentist jihadi/doctrinaire jihadi Islamism.[95]

Moderate and reformist Islamism[edit]

Throughout the 80s and 90s, major moderate Islamist movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood and the Ennahda were excluded from democratic political participation. At least in part for that reason, Islamists attempted to overthrow the government in the Algerian Civil War (1991–2002) and waged a terror campaign in Egypt in the 90s. These attempts were crushed and in the 21st century, Islamists turned increasingly to non-violent methods,[96] and "moderate Islamists" now make up the majority of the contemporary Islamist movements.[21][87][97]

Among some Islamists, Democracy has been harmonized with Islam by means of Shura (consultation). The tradition of consultation by the ruler being considered Sunnah of the prophet Muhammad,[97][98][99] (Majlis-ash-Shura being a common name for legislative bodies in Islamic countries).

Among the varying goals, strategies, and outcomes of "moderate Islamist movements" are a formal abandonment of their original vision of implementing sharia (also termed Post-Islamism) – done by the Ennahda Movement of Tunisia,[100] and Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) of Indonesia.[101] Others, such as the National Congress of Sudan, have implemented the sharia with support from wealthy, conservative states (primarily Saudi Arabia).[102][103]

According to one theory – "inclusion-moderation"—the interdependence of political outcome with strategy means that the more moderate the Islamists become, the more likely they are to be politically included (or unsuppressed); and the more accommodating the government is, the less "extreme" Islamists become.[104] A prototype of harmonizing Islamist principles within the modern state framework was the "Turkish model", based on the apparent success of the rule of the Turkish Justice and Development Party (AKP) led by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.[105] Turkish model, however, came "unstuck" after a purge and violations of democratic principles by the Erdoğan regime.[106][107] Critics of the concept – which include both Islamists who reject democracy and anti-Islamists – hold that Islamist aspirations are fundamentally incompatible with the democratic principles.

Salafi movement[edit]

| Part of a series on: Salafi movement |

|---|

|

The contemporary Salafi movement is sometimes described as a variety of Islamism and sometimes as a different school of Islam,[108] such as a "phase between fundamentalism and Islamism".[109]Originally a reformist movement of Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, Muhammad Abdul, and Rashid Rida, that rejected maraboutism (Sufism), the established schools of fiqh, and demanded individual interpretation (ijtihad) of the Quran and Sunnah;[110] it evolved into a movement embracing the conservative doctrines of the medieval Hanbali theologian Ibn Taymiyyah. While all salafi believe Islam covers every aspect of life, that sharia law must be implemented completely and that the Caliphate must be recreated to rule the Muslim world, they differ in strategies and priorities, which generally fall into three groups:

- The "quietist" school advocates Islamization through preaching, educating the masses on sharia and "purification" of religious practices and ignoring government.

- Activist (or haraki) Salafi activism encourages political participation—opposing government loans with interest or normalization of relations with Israel, etc. As of 2013, this school makes up the majority of Salafism.[111] Salafist political parties in the Muslim world include Hizb al-Nour in Egypt, the Al Islah Party of Yemen and Al Asalah of Bahrain.

- Salafi jihadism, (see below) is inspired by the ideology of Sayyid Qutb (Qutbism, see below), and sees secular institutions as an enemy of Islam, advocating revolution to pave the way for the establishment of a new Caliphate.[112]

Wahhabism[edit]

One of the antecedents of the contemporary Salafi movement is Wahhabism, an 18th-century reform movement from the Arabia founded by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. Ibn Abd al-Wahhab, gave his bay'ah (pledge of allegiance to a ruler/commander),[113] to the House of Saud, the rulers of Saudi Arabia, and so have almost all Wahhabi since, (small numbers have become Salafi Jihadist or other dissidents).[114][115] Obedience to a ruler precluding any political activism (short of an advisor whispering advice to the ruler), there are few Wahhabi Islamists, at least in Saudi Arabia.[114][116]

Wahhabism and Salafism more or less merged by the 1960s in Saudi Arabia,[117][118][119][120] and together they benefited from $100s of billions in state-sponsored worldwide propagation of conservative Islam financed by Saudi petroleum exports,[121] (a phenomenon often dubbed as Petro-Islam).[122] (This financing has contributed indirectly to the upsurge of Salafi Jihadism.)[122]

Militant Islamism/Jihadism[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Jihadism |

|---|

Qutbism[edit]

Qutbism refers to the Jihadist ideology formulated by Sayyid Qutb, (an influential figure of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt during the 50s and 60s). Qutbism argued that not only was sharia essential for Islam, but that since it was not in force, Islam did not really exist in the Muslim world, which was in Jahiliyya (the state of pre-Islamic ignorance). To remedy this situation he urged a two-pronged attack of 1) preaching to convert, and 2) jihad to forcibly eliminate the "structures" of Jahiliyya.[123] Defensive jihad against Jahiliyya Muslim governments would not be enough. "Truth and falsehood cannot coexist on this earth", so offensive Jihad was needed to eliminate Jahiliyya not only from the Islamic homeland but from the face of the Earth.[124] In addition, vigilance against Western and Jewish conspiracies against Islam would-be needed.[125][126]

Although Qutb was executed before he could fully spell out his ideology,[127] his ideas were disseminated and expanded on by the later generations, among them Abdullah Yusuf Azzam and Ayman Al-Zawahiri, who was a student of Qutb's brother Muhammad Qutb and later became a mentor of Osama bin Laden.[128][129] Al-Zawahiri helped to pass on stories of "the purity of Qutb's character" and persecution he suffered, and played an extensive role in the normalization of offensive Jihad among followers of Qutb.[130]

Salafi Jihadism[edit]

Salafi Jihadism or revolutionary Salafism[131] emerged prominent during the 80s when Osama bin Laden and thousands of other militant Muslims came from around the Muslim world to help fight the Soviet Union after it invaded Afghanistan.[132][133][134][135] Local Afghan Muslims had declared jihad against the Soviets (mujahideen) and were aided with financial, logistical and military support by Saudi Arabia and the United States, but after Soviet forces left Afghanistan, this funding and interest by America and Saudi ceased. The international volunteers, (originally organized by Abdullah Azzam), were triumphant in victory, away from the moderating influence of home and family, among the radicalized influence of other militants.[136] Wanting to capitalize on financial, logistical and military network that had been developed[132] they sought to continue waging jihad elsewhere.[137] Their new targets, however, included the United States—funder of the mujahideen but "perceived as the greatest enemy of the faith"; and governments of majority-Muslims countries—perceived of as apostates from Islam.[138][136]

Salafist-jihadist ideology combined the literal and traditional interpretations of scripture of Salafists, with the promotion and fighting of jihad against military and civilian targets in the pursuit of the establishment of an Islamic state and eventually a new Caliphate.[136][133][126][139][note 1]

Other characteristics of the movement include the formal process of taking bay'ah (oath of allegiance) to the leader (amir), which is inspired by Hadiths and early Muslim practice and included in Wahhabi teaching;[141] and the concepts of "near enemy" (governments of majority-Muslims countries) and "far enemy" (United States and other Western countries). (The term "near enemy" was coined by Mohammed Abdul-Salam Farag who led the assassination of Anwar al-Sadat with Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ) in 1981.)[142] The "far enemy" was introduced and formally declared under attack by al-Qaeda in 1996.[142][143]

The ideology saw its rise during the 90s when the Muslim world experienced numerous geopolitical crisis,[132] notably the Algerian Civil War (1991–2002), Bosnian War (1992–1995), and the First Chechen War (1994–1996). Within these conflicts, political Islam often acted as a mobilizing factor for the local belligerents, who demanded financial, logistical and military support from al-Qaeda, in the exchange for active proliferation of the ideology.[132] After the 1998 bombings of US embassies, September 11 attacks (2001), the US-led invasion of Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003), Salafi Jihadism lost its momentum, being devastated by the US counterterrorism operations, culminating in bin Laden's death in 2011.[132] After the Arab Spring (2011) and subsequent Syrian Civil War (2011–present), the remnants of al-Qaeda franchise in Iraq restored their capacity, rapidly developing into the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, spreading its influence throughout the conflict zones of MENA region and the globe. Salafi Jihadism makes up a minority of the contemporary Islamist movements.[144]

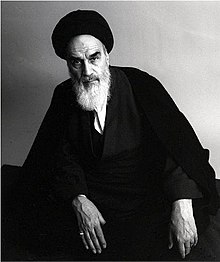

Shi'i Islamism[edit]

Although most of the research and reporting about Islamism or political Islam has been focused on Sunni Islamist movements,[note 2]Islamism exists in Twelver Shia Islam (the second largest branch of Islam that makes up approximately 10% of all Muslims.[note 3]). Islamist Shi'ism, also known as Shi'i Islamism, is primarily but not exclusively[note 4] associated with the thought of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, with the Islamist Revolution he led, Islamic Republic of Iran that he founded, and the religious-political activities and resources of the republic.

Compared to the "Types" of Islamism mentioned above, Khomeinism differs from Wahhabism (which does not consider Shi'ism truly Islamic), Salafism (both orthodox or Jihadi—Shi'a do not consider some of the most prominent salaf worthy of emulation), reformist Islamism (the Islamic Republic executed more than 3,400 political dissidents between June 1981 and March 1982 in the process of consolidating power).[145][146]

Khomeini and his followers helped translate the works of Maududi and Qutb into Persian and were influenced by them, but their views differed from them and other Sunni Islamists in being "more leftist and more clerical":[147]

- more leftist in the propaganda campaign leading up to the revolution, emphasizing exploitation of the poor by the rich and of Muslims by imperialism;[148][note 5]

- more clerical in the new post-revolutionary state, where clerics were in control of the levers of power (the Supreme Leader, Guardian Council, etc., under the concept of Velayat-e Faqih.[note 6]).

Khomeini was a "radical" Islamist,[153] like Qutb and unlike Maudidi. He believed that foreigners, Jews and their agents were conspiring "to keep us backward, to keep us in our present miserable state".[154] Those who call themselves Muslims but were secular and Westernizing, were not just corrupt or misguided, but "agents" of the Western governments, helping to "plunder" Muslim lands as part of a long-term conspiracy against Islam.[155] Only the rule of an Islamic jurist, administering Sharia law, stood between this abomination and justice, and could not wait for peaceful, gradual transition. It is the duty of Muslims to "destroy" "all traces" of any other sort of government other than true Islamic governance because these are "systems of unbelief".[156] "Troublesome" groups that cause "corruption in Muslim society," and damage "Islam and the Islamic state" are to be eliminated just as the Prophet Muhammad eliminated the Jews of Bani Qurayza.[157] Islamic revolution to install "the form of government willed by Islam" will not end with one Islamic state in Iran. Once this government comes "into being, none of the governments now existing in the world" will "be able to resist it;" they will "all capitulate".[158]

Ruling Islamic Jurist[edit]

Khomeini's form of Islamism was particularly unique in the world because it completely swept the old regime away, created a new regime with a new constitution, new institutions and a new concept of governance (the Velayat-e Faqih). A historical event, it changed militant Islam from a topic of limited impact and interest to a topic that few either inside or outside the Muslim world were unaware of.[159] As he originally described it in lectures to his students, the system of "Islamic Government" was one where the leading Islamic jurist would enforce sharia law—law which "has absolute authority over all individuals and the Islamic government".[160] The jurist would not be elected, and no legislature would be needed since divine law called for rule by jurist and "there is not a single topic in human life for which Islam has not provided instruction and established a norm".[161] Without this system, injustice, corruption, waste, exploitation and sin would reign, and Islam would decay. This plan was disclosed to his students and the religious community but not widely publicized.[162] The constitution of the Islamic Republic written after the revolution did include a legislature and president, but supervising the entire government was a "Supreme Leader"/guardian jurist.

Islamist Shi'ism has been crucial to the development of worldwide Islamism, because the Iranian regime attempted to export its revolution.[163] Although, the Islamist ideology was originally imported from Muslim Brotherhood, Iranian relations between the Muslim Brotherhood and Islamic Republic of Iran deteriorated due to its involvement in the Syrian civil war.[164] However, the majority Usuli Shi'ism rejects the idea of an Islamist State in the period of Occultation of the Hidden Imam.[165]

Shi'ism and Iran[edit]

Twelver Shia Muslim live mainly in a half dozen or so countries scattered around the Middle East and South Asia.[note 7]The Islamic Republic of Iran has become "the de facto leader"[168] of the Shi'i world by virtue of being the largest Shia-majority state, having a long history of national cohesion and Shia-rule, being the site of the first and "only true"[169] Islamist revolution (see History section below), and having the financial resources of a major petroleum exporter. Iran's influence has spread into a cultural-geographic area of "Irano-Arab Shiism", establishing Iranian regional power,[note 8] supporting "Shia militias and parties beyond its borders",[167][note 9] intertwining assistance to fellow Shi'a with "Iranization" of them.[169]

Shi'i Islamism in Iran has been influenced by the Sunni Islamists and their organizations,[171][172] particularly Sayyid Rashid Rida,[11] Hassan al-Banna (founder of the Muslim Brotherhood organization),[172] Sayyid Qutb,[173] Abul A'la Maududi,[12] but has also been described as "distinct" from Sunni Muslim Brotherhood Islamism, "more leftist and more clerical",[147] with its own historical influencers:

Historical figures[edit]

- Sheikh Fazlullah Nouri,[174] a cleric of the Qajar dynasty court and the leader of the anti-constitutionalists during the Persian Constitutional Revolution of 1905–1911,[175] who declared the new constitution contrary to sharia law.[176]

- Navvab Safavi, a religious student who founded the Fada'iyan-e Islam, seeking to purify Islam in Iran by killing off 'corrupting individuals', i.e. certain leading intellectual and political figures (including both a former and current prime minister).[177] After the group was crushed by the government, surviving members reportedly chose Ayatollah Khomeini as a new spiritual leader.[178][179]

- Ali Shariati, a non-cleric "socialist Shi'i" who absorbed Marxist ideas in France and had considerable influence on young Iranians through his preaching that Imam Hussein was not just a holy figure but the original oppressed one (muzloun), and his killer, the Sunni Umayyad Caliphate, the "analog" of the modern Iranian people's "oppression by the shah".[180]

- Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr, a Shi'i Islamic scholar in Iraq who critiqued Marxism, socialism and capitalism and helped lead Shi'i opposition to Saddam Hussein's Baath regime before being executed by them.

- Mahmoud Taleghani, an ayatollah and contemporary of Khomeini, was more leftist, more tolerant and more sympathetic to democracy, but less influential, though he still had a substantial following. Was deposed from revolutionary leadership[181] after warning of a "return to despotism" by the revolutionary leadership.[182]

Explanations for the growth and popularity of Islamism[edit]

Sociological, economic and political[edit]

Some Western political scientists see the unchanging socio-economic condition in the Muslim world as a major factor. Olivier Roy believes "the socioeconomic realities that sustained the Islamist wave are still here and are not going to change: poverty, uprootedness, crises in values and identities, the decay of the educational systems, the North-South opposition, and the problem of immigrant integration into the host societies".[183]

Charitable work[edit]

Islamist movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood, "are well known for providing shelters, educational assistance, free or low cost medical clinics, housing assistance to students from out of town, student advisory groups, facilitation of inexpensive mass marriage ceremonies to avoid prohibitively costly dowry demands, legal assistance, sports facilities, and women's groups." All this compares very favourably against incompetent, inefficient, or neglectful governments whose commitment to social justice is limited to rhetoric.[184]

Economic stagnation[edit]

The Arab world—the original heart of the Muslim world—has been afflicted with economic stagnation. For example, it has been estimated that in the mid-1990s the exports of Finland, a country of five million, exceeded those of the entire Arab world of 260 million, excluding oil revenue.[185]

Sociology of rural migration[edit]

Demographic transition (caused by the gap in time between the lowering of death rates from medical advances and the lowering of fertility rates), leads to population growth beyond the ability of housing, employment, public transit, sewer and water to provide. Combined with economic stagnation, urban agglomerations have been created in Cairo, Istanbul, Tehran, Karachi, Dhaka, and Jakarta, each with well over 12 million citizens, millions of them young and unemployed or underemployed.[186] Such a demographic, alienated from the westernized ways of the urban elite, but uprooted from the comforts and more passive traditions of the villages they came from, is understandably favourably disposed to an Islamic system promising a better world[187]—an ideology providing an "emotionally familiar basis for group identity, solidarity, and exclusion; an acceptable basis for legitimacy and authority; an immediately intelligible formulation of principles for both a critique of the present and a program for the future."[188] One American anthropologist in Iran in the early 1970s (before the revolution), when comparing a "stable village with a new urban slum", discovered that where "the villagers took religion with a grain of salt and even ridiculed visiting preachers", the slum dwellers—all recently dispossessed peasants – "used religion as a substitute for their lost communities, oriented social life around the mosque, and accepted with zeal the teachings of the local mullah".[189]

Gilles Kepel also notes that Islamist uprisings in Iran and Algeria, though a decade apart, coincided with the large numbers of youth who were "the first generation taught en masse to read and write and had been separated from their own rural, illiterate progenitors by a cultural gulf that radical Islamist ideology could exploit". Their "rural, illiterate" parents were too settled in tradition to be interested in Islamism and their children "more likely to call into question the utopian dreams of the 1970s generation", but they embraced revolutionary political Islam.[190] Olivier Roy also asserts "it is not by chance that the Iranian Revolution took place the very year the proportion of city-dweller in Iran passed the 50% mark".[191] and offers statistics in support for other countries (in 1990 Algeria, housing was so crowded that there was an average of eight inhabitants to a room, and 80% of youth aged 16 to 29 still lived with their parents). "The old clan or ethnic solidarities, the clout of the elders, and family control are fading little by little in the face of changes in the social structure ..."[192]This theory implies that a decline in illiteracy and rural emigration will mean a decline in Islamism.

Geopolitics[edit]

State-sponsorship[edit]

Saudi Arabia[edit]

Starting in the mid-1970s the Islamic resurgence was funded by an abundance of money from Saudi Arabian oil exports.[193] The tens of billions of dollars in "petro-Islam" largesse obtained from the recently heightened price of oil funded an estimated "90% of the expenses of the entire faith."[194]

Throughout the Muslim world, religious institutions for people both young and old, from children's madrassas to high-level scholarships received Saudi funding,[195]"books, scholarships, fellowships, and mosques" (for example, "more than 1500 mosques were built and paid for with money obtained from public Saudi funds over the last 50 years"),[196] along with training in the Kingdom for the preachers and teachers who went on to teach and work at these universities, schools, mosques, etc.[197]

The funding was also used to reward journalists and academics who followed the Saudis' strict interpretation of Islam; and satellite campuses were built around Egypt for Al-Azhar University, the world's oldest and most influential Islamic university.[198]

The interpretation of Islam promoted by this funding was the strict, conservative Saudi-based Wahhabism or Salafism. In its harshest form it preached that Muslims should not only "always oppose" infidels "in every way," but "hate them for their religion ... for Allah's sake," that democracy "is responsible for all the horrible wars of the 20th century," that Shia and other non-Wahhabi Muslims were infidels, etc.[199] While this effort has by no means converted all, or even most Muslims to the Wahhabist interpretation of Islam, it has done much to overwhelm more moderate local interpretations, and has set the Saudi-interpretation of Islam as the "gold standard" of religion in minds of some or many Muslims.[200]

Qatar[edit]

Though the much smaller Qatar could not provide the same level of funding as Saudi Arabia, it was also a petroleum exporter and also sponsored Islamist groups. Qatar backed the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt even after the 2013 overthrow of the MB regime of Mohamed Morsi, with Qatar ruler Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani denouncing the coup.[201] In June 2016, Mohamed Morsi was sentenced to life for passing state secrets to Qatar.[202][203]

Qatar has also backed Islamist factions in Libya, Syria and Yemen.In Libya, Qatar supported Islamists with tens of millions of dollars in aid, military training and "more than 20,000 tons of weapons", both before and after the 2011 fall of Muammar Gaddafi.[204][205][206]

Hamas, in Palestine, has received considerable financial support as well as diplomatic help.[207][206][208][209]

Western support of Islamism during the Cold War[edit]

During the Cold War, particularly during the 1950s, during the 1960s, and during most of the 1970s, the U.S. and other countries in the Western Bloc occasionally attempted to take advantage of the rise of Islamic religiousity by directing it against secular leftist/communist/nationalist insurgents/adversaries, particularly against the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc states, whose ideology was not just secular but anti-religious.

In 1957, U.S. President Eisenhower and senior U.S. foreign policy officials, agreed on a policy of using the communists' lack of religion against them: "We should do everything possible to stress the 'holy war' aspect" that has currency in the Middle East.[210]

During the 1970s and sometimes later, this aid sometimes went to fledgling Islamists and Islamist groups that later came to be seen as dangerous enemies.[211] The US spent billions of dollars to aid the mujahideen Muslim Afghanistan enemies of the Soviet Union, and non-Afghan veterans of the war (such as Osama bin Laden) returned home with their prestige, "experience, ideology, and weapons", and had considerable impact.[212]

Although it is a strong opponent of Israel's existence, Hamas, officially founded in 1987, traces its origins back to institutions and clerics which were supported by Israel in the 1970s and 1980s. Israel tolerated and supported Islamist movements in Gaza, with figures like Ahmed Yassin, as Israel perceived them preferable to the secular and then more powerful al-Fatah with the PLO.[213][214]

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat – whose policies included opening Egypt to Western investment (infitah); transferring Egypt's allegiance from the Soviet Union to the United States; and making peace with Israel—released Islamists from prison and welcomed home exiles in tacit exchange for political support in his struggle against leftists. His "encouraging of the emergence of the Islamist movement" was said to have been "imitated by many other Muslim leaders in the years that followed."[215][216] This "gentlemen's agreement" between Sadat and Islamists broke down in 1975 but not before Islamists came to completely dominate university student unions. Sadat was later assassinated and a formidable insurgency was formed in Egypt in the 1990s. The French government has also been reported to have promoted Islamist preachers "in the hope of channeling Muslim energies into zones of piety and charity."[211]

History[edit]

Olivier Roy dates the beginning of the Islamism movement "more or less in 1940",[217] and its development proceeding "over half a century".[217]

Preceding movements[edit]

Some Islamic revivalist movements and leaders which pre-date Islamism but share some characteristics with it include:

- Ahmad Sirhindi (~1564–1624) was largely responsible for the purification, reassertion and revival of conservative orthodox Sunni Islam in India during Islam's second millennium.[218][219][220]

- Ibn Taymiyyah, a Syrian Islamic jurist during the 13th and 14th centuries argued against the practices such as the celebration of Muhammad's birthday, and seeking assistance at the grave of the Prophet.[221]

- Muhammad ibn Abd-al-Wahhab, the founder of Wahhabism, advocated doing away with the later religious accretions like worship at graves.

- Shah Waliullah of India was a forerunner of reformist Islamists like Muhammad Abduh, Muhammad Iqbal and Muhammad Asad in his belief that there was "a constant need for new ijtihad as the Muslim community progressed.[222]

- Sayyid Ahmad Barelvi was a disciple and successor of Shah Waliullah's son who led a jihadist movement and attempted to create an Islamic state based on the enforcement of Islamic law.[223][224]

- the Deobandi movement, founded after the defeat of the Indian Rebellion, around 1867, led to the establishment of thousands of conservative Islamic schools or madrasahs throughout modern-day India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.[225]

Early history[edit]

The end of the 19th century saw the dismemberment of most of the Muslim Ottoman Empire by non-Muslim European colonial powers,[226] despite the empire's spending massive sums on Western civilian and military technology to try to modernize and compete with the encroaching European powers. In the process the Ottomans went deep into debt to these powers.

Preaching Islamic alternatives to this humiliating decline were Jamal ad-din al-Afghani (1837–97), Muhammad Abduh (1849–1905) and Rashid Rida (1865–1935).[227][228][229][230][231] Abduh's student Rida is widely regarded as one of the "ideological forefathers" of contemporary Islamist movement,[232] and along with early Salafiyya Hassan al-Banna,and Mustafa al-Siba’i, preached that a truly Islamic society would follow sharia law, reject taqlid, (the blind imitation of earlier authorities),[233] restore the Caliphate.[234]

Sayyid Rashid Rida[edit]

Syrian-Egyptian Islamic cleric Muhammad Rashid Rida was one of the earliest 20th-century Sunni scholars to articulate the modern concept of an Islamic state, influencing the Muslim Brotherhood and other Sunni Islamist movements. In his influential book al-Khilafa aw al-Imama al-'Uzma ("The Caliphate or the Grand Imamate"); Rida explained that that societies that properly obeyed Sharia would be successful alternatives to the disorder and injustice of both capitalism and socialism.[235]

This society would be ruled by a Caliphate; the ruling Caliph (Khalifa) governing through shura (consultation), and applying Sharia (Islamic laws) in partnership with Islamic juristic clergy, who would use Ijtihad to update fiqh by evaluating scripture.[236] With the Khilafa providing true Islamic governance, Islamic civilization would be revitalised, the political and legal independence of the Muslim umma (community of Muslim believers) would be restored, and the heretical influences of Sufism would be cleansed from Islam.[237] This doctrine would become the blueprint of future Islamist movements.[238]

Muhammad Iqbal[edit]

Muhammad Iqbal was a philosopher, poet and politician[239] in British India,[239][240] widely regarded as having inspired the Islamic Nationalism and Pakistan Movement in British India.[239][241][242]

Iqbal expressed fears of secularism and secular nationalism weakening the spiritual foundations of Islam and Muslim society, and of India's Hindu-majority population crowding out Muslim heritage, culture and political influence. In 1930, Iqbal outlined a vision of an independent state for Muslim-majority provinces in northwestern India which inspired the Pakistan movement.

He also promoted pan-Islamic unity in his travels to Egypt, Afghanistan, Palestine and Syria.

His ideas later influenced many reformist Islamists, e.g., Muhammad Asad, Sayyid Abul Ala Maududi and Ali Shariati.

Sayyid Abul Ala Maududi[edit]

Sayyid Abul Ala Maududi[243][244] was an important early twentieth-century figure in the Islamic revival in India, and then after independence from Britain, in Pakistan. Maududi was an Islamist ideologue and Hanafi Sunni scholar active in Hyderabad Deccan and later in Pakistan. Maududi was born to a clerical family and got his early education at home. At the age of eleven, he was admitted to a public school in Aurangabad. In 1919, he joined the Khilafat Movement and got closer to the scholars of Deoband.[245] He commenced the Dars-i Nizami education under supervision of Deobandi seminary at the Fatihpuri mosque in Delhi.[57] Trained as a lawyer he worked as a journalist, and gained a wide audience with his books (translated into many languages) which placed Islam in a modern context. His writings had a profound impact on Sayyid Qutb. Maududi also founded the Jamaat-e-Islami party in 1941 and remained its leader until 1972.[246]

In 1925, he wrote a book on Jihad, al-Jihad fil-Islam (Arabic: الجهاد في الاسلام), that can be regarded as his first contribution to Islamism.[247] Maududi believed that Muslim society could not be Islamic without Sharia (influencing Qutb and Khomeini), and the establishment of an Islamic state to enforce it.[248] The state would be based on the principles of: tawhid (unity of God), risala (prophethood) and khilafa (caliphate).[249][250][251][252] Maududi was uninterested in violent revolution or populist policies such as those of the Iranian Revolution, but sought gradual change in the hearts and minds of individuals from the top of society downward through an educational process or da'wah.[253][254] Maududi believed that Islam was all-encompassing: "Everything in the universe is 'Muslim' for it obeys God by submission to His laws."[255] "The man who denies God is called Kafir (concealer) because he conceals by his disbelief what is inherent in his nature and embalmed in his own soul."[256][257]

Muslim Brotherhood[edit]

Roughly contemporaneous with Maududi was the founding of the Muslim Brotherhood in Ismailiyah, Egypt in 1928 by Hassan al Banna. His was arguably the first, largest and most influential modern Islamic political/religious organization. Under the motto "the Qur'an is our constitution",[258]it sought Islamic revival through preaching and also by providing basic community services including schools, mosques, and workshops. Like Maududi, Al Banna believed in the necessity of government rule based on Shariah law implemented gradually and by persuasion, and of eliminating all Western imperialist influence in the Muslim world.[259]

Some elements of the Brotherhood did engage in violence, assassinating Egypt's premier Mahmoud Fahmy El Nokrashy in 1948. MB founder Al-Banna was assassinated in retaliation three months later.[260] The Brotherhood has suffered periodic repression in Egypt and has been banned several times, in 1948 and several years later following confrontations with Egyptian president Gamal Abdul Nasser, who jailed thousands of members for several years.

The Brotherhood expanded to many other countries, particularly in the Arab world. In Egypt, despite periodic repression—for many years it wasdescribed as "semi-legal"[261]—it was the only opposition group in Egypt able to field candidates during elections.[262] In the 2011–12 Egyptian parliamentary election, the political parties identified as "Islamist" (the Brotherhood's Freedom and Justice Party, Salafi Al-Nour Party and liberal Islamist Al-Wasat Party) won 75% of the total seats.[263] Mohamed Morsi, the candidate of the Muslim Brotherhood's party, was the first democratically elected president of Egypt. However, he was deposed during the 2013 Egyptian coup d'état, after mass protests against what were perceived as undemocratic moves by him. Today, the Muslim Brotherhood is designated as a terrorist organization by Bahrain, Russia, Syria, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Sayyid Qutb (1906–1966)[edit]

Qutb, a leading member of the Muslim Brotherhood movement, is considered by some (Fawaz A. Gerges) to be "the founding father and leading theoretician" of modern jihadists, such as Osama bin Laden.[264][265][266] He was executed for allegedly participating in a presidential assassination plot in 1966.

Maududi's political ideas influenced Sayyid Qutb. Like Maududi, he believed Sharia was crucial to Islam, so the restoration of its full enforcement was vital to the world. Since Sharia had not been fully enforced for centuries, Islam had "been extinct for a few centuries".[267] Qutb preached that Muslims must engage in a two-pronged attack of converting individuals through preaching Islam peacefully but also using "physical power and jihad".[268] Force was necessary because "those who have usurped the authority of God" would not give up their power through friendly persuasion.[269]Like Khomeini, whom he influenced he believed the West was engaged in a vicious centuries long war against Islam.[270]

Six-Day War (1967)[edit]

The quick and decisive defeat of the armies of several Arab states by one small non-Muslim country during the Six-Day War constituted a pivotal event in the Arab Muslim world. The defeat along with economic stagnation in the defeated countries, was blamed on the secular Arab nationalism of the ruling regimes. A steep and steady decline in the popularity and credibility of secular, socialist and nationalist politics ensued. Ba'athism, Arab socialism, and Arab nationalism suffered, and different democratic and anti-democratic Islamist movements inspired by Maududi and Sayyid Qutb gained ground.[271]

Iranian Revolution (1978–1979)[edit]

The first modern "Islamist state" (with the possible exception of Zia's Pakistan)[272] was established among the Shia of Iran. In a major shock to the rest of the world, Muslim and non-Muslim, a revolution led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini overthrew the secular, oil-rich, well-armed, pro-American monarchy of Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi. The revolution was an "indisputable sea change";[273] Islamism had been a topic of limited impact and interest before 1979, but after the revolution, "nobody within the Muslim world or outside it" remained unaware of militant Islam.[159]

Enthusiasm for the Iranian revolution in the Muslim world could be intense;[note 10] and there were many reasons for optimism among Islamists outside Iran. Khomeini was implementing Islamic law.[275] He was interested in Pan-Islamic (and pan-Islamist) unity and made efforts to "bridge the gap" between Shiites and Sunnis, declaring "it permissible for Shiites to pray behind Sunni imams",[276] and forbidding Shiites from "criticizing the Caliphs who preceded Ali" (revered by Sunnis but not Shia).[277] The Islamic Republic also downplayed Shia rituals (such as the Day of Ashura), and shrines [note 11] Before the Revolution, Khomeini acolytes (such as today's Supreme Leader of Iran, Ali Khamenei), translated and championed the works of the Muslim Brotherhood jihadist theorist, Sayyid Qutb,[172] and other Sunni Islamists/revivalists.[172]

This campaign did not survive his death however. As previously submissive Shia (usually minorities) became more assertive, Sunnis saw mostly "Shia mischief" and a challenge to Sunni dominance.[280] "What followed was a Sunni-versus-Shia contest for dominance, and it grew intense."[281] Animosity between the two sects in Iran and its neighbors is systemic as of 2014,[282] with thousands killed from sectarian fighting in Iraq and Pakistan.[283] Also tarnishing the revolution's image have been "purges, executions, and atrocities",[284] and periodic and increasingly widespread domestic unrest and protest by young Iranians.

Among the "most important by-products of the Iranian revolution" (according to Mehrzad Boroujerdi as of 2014) include "the emergence of Hezbollah in Lebanon, the moral boost provided to Shia forces in Iraq, the regional cold war against Saudi Arabia and Israel, lending an Islamic flavour to the anti-imperialist, anti-American sentiment in the Middle East, and inadvertently widening the Sunni-Shia cleavage".[273] The Islamic Republic has also maintained its hold on power in Iran in spite of US economic sanctions, and has created or assisted like-minded Shia terrorist groups in Iraq (SCIRI)[285][286] and Lebanon (Hezbollah)[287] (two Muslim countries that also have a large percentage of Shiites).

The campaign to overthrow the shah led by Khomeini had had a strong class flavor (Khomeini preached that the shah was widening the gap between rich and poor; condemning the working class to a life of poverty, misery, and drudgery, etc.);[148] and the "pro-rural and pro-poor"[288] approach has led to almost universal access to electricity and clean water,[289] but critics of the regime complain of promises made and not kept: the “sons of the revolution’s leaders and the business class that decides to work within the rules of the regime ... flaunt their wealth, driving luxury sportscars around Tehran, posting Instagram pictures of their ski trips and beach trips around the world, all while the poor and the middle class are struggling to survive or maintain the appearance of a dignified life” (according to Shadi Mokhtari).[290] One commitment made (to his followers if not the Iranian public) that has been kept is Guardianship by the Islamic jurist. But Rather than strengthening Islam and eliminating secular values and practices, the "regime has ruined the Iranian people’s belief in religion" ("anonymous expert").[290]

Grand Mosque seizure (1979)[edit]

The strength of the Islamist movement was manifest in an event which might have seemed sure to turn Muslim public opinion against fundamentalism, but did just the opposite. In 1979 the Grand Mosque in Mecca Saudi Arabia was seized by an armed fundamentalist group and held for over a week. Scores were killed, including many pilgrim bystanders[291] in a gross violation of one of the most holy sites in Islam (and one where arms and violence are strictly forbidden).[292][293]

Instead of prompting a backlash against the movement that inspired the attackers, however, Saudi Arabia, already very conservative, responded by shoring up its fundamentalist credentials with even more Islamic restrictions. Crackdowns followed on everything from shopkeepers who did not close for prayer and newspapers that published pictures of women, to the selling of dolls, teddy bears (images of animate objects are considered haraam), and dog food (dogs are considered unclean).[294]

In other Muslim countries, blame for and wrath against the seizure was directed not against fundamentalists, but against Islamic fundamentalism's foremost geopolitical enemy—the United States. Ayatollah Khomeini sparked attacks on American embassies when he announced: "It is not beyond guessing that this is the work of criminal American imperialism and international Zionism", despite the fact that the object of the fundamentalists' revolt was the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, America's major ally in the region. Anti-American demonstrations followed in the Philippines, Turkey, Bangladesh, India, the UAE, Pakistan, and Kuwait. The US Embassy in Libya was burned by protesters chanting pro-Khomeini slogans and the embassy in Islamabad, Pakistan was burned to the ground.[295]

Soviet invasion of Afghanistan (1979–1989)[edit]

In 1979, the Soviet Union deployed its 40th Army into Afghanistan, attempting to suppress an Islamic rebellion against an allied Marxist regime in the Afghan Civil War. The conflict, pitting indigenous impoverished Muslims (mujahideen) against an anti-religious superpower, galvanized thousands of Muslims around the world to send aid and sometimes to go themselves to fight for their faith. Leading this pan-Islamic effort was Palestinian 'alim Abdullah Yusuf Azzam. While the military effectiveness of these "Afghan Arabs" was marginal, an estimated 16,000[296] to 35,000 Muslim volunteers[297] came from around the world to fight in Afghanistan.[297][298]

When the Soviet Union abandoned the Marxist Najibullah regime and withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989 (the regime finally fell in 1992), the victory was seen by many Muslims as the triumph of Islamic faith over superior military power and technology that could be duplicated elsewhere.

The jihadists gained legitimacy and prestige from their triumph both within the militant community and among ordinary Muslims, as well as the confidence to carry their jihad to other countries where they believed Muslims required assistance.[299]

The collapse of the Soviet Union itself, in 1991, was seen by many Islamists, including Bin Laden, as the defeat of a superpower at the hands of Islam. Concerning the $6 billion in aid given by the US and Pakistan's military training and intelligence support to the mujahideen,[300] bin Laden wrote: "[T]he US has no mentionable role" in "the collapse of the Soviet Union... rather the credit goes to God and the mujahidin" of Afghanistan.[301]

Persian Gulf War (1990–1991)[edit]

Another factor in the early 1990s that worked to radicalize the Islamist movement was the Gulf War, which brought several hundred thousand US and allied non-Muslim military personnel to Saudi Arabian soil to put an end to Saddam Hussein's occupation of Kuwait. Prior to 1990 Saudi Arabia played an important role in restraining the many Islamist groups that received its aid. But when Saddam, secularist and Ba'athist dictator of neighboring Iraq, attacked Kuwait (his enemy in the war), western troops came to protect the Saudi monarchy. Islamists accused the Saudi regime of being a puppet of the west.

These attacks resonated with conservative Muslims and the problem did not go away with Saddam's defeat either, since American troops remained stationed in the kingdom, and a de facto cooperation with the Palestinian-Israeli peace process developed. Saudi Arabia attempted to compensate for its loss of prestige among these groups by repressing those domestic Islamists who attacked it (bin Laden being a prime example), and increasing aid to Islamic groups (Islamist madrassas around the world and even aiding some violent Islamist groups) that did not, but its pre-war influence on behalf of moderation was greatly reduced.[302] One result of this was a campaign of attacks on government officials and tourists in Egypt, a bloody civil war in Algeria and Osama bin Laden's terror attacks climaxing in the 9/11 attack.[303]

Social and cultural triumph in the 2000s[edit]

By the beginning of the twenty first century, "the word secular, a label proudly worn" in the 1960s and 70s was "shunned" and "used to besmirch" political foes in Egypt and the rest of the Muslim world.[79] Islamists surpassed the small secular opposition parties in terms of "doggedness, courage," "risk-taking" or "organizational skills".[77] As of 2002,

In the Middle East and Pakistan, religious discourse dominates societies, the airwaves, and thinking about the world. Radical mosques have proliferated throughout Egypt. Book stores are dominated by works with religious themes ... The demand for sharia, the belief that their governments are unfaithful to Islam and that Islam is the answer to all problems, and the certainty that the West has declared war on Islam; these are the themes that dominate public discussion. Islamists may not control parliaments or government palaces, but they have occupied the popular imagination.[304]

Opinion polls in a variety of Islamic countries showed that significant majorities opposed groups like ISIS, but also wanted religion to play a greater role in public life.[305]

"Post-Islamism"[edit]

By 2020, approximately 40 years after the Islamic overthrow of the Shah of Iran and the seizure of the Grand Mosque by extremists, a number of observers (Olivier Roy, Mustafa Akyol, Nader Hashemi) detected a decline in the vigor and popularity of Islamism. Islamism had been an idealized/utopian concept to compare with the grim reality of the status quo, but in more than four decades it had failed to establish a "concrete and viable blueprint for society" despite repeated efforts (Olivier Roy);[306] and instead had left a less than inspiring track record of its impact on the world (Nader Hashemi).[307] Consequently,in addition to the trend towards moderation by Islamist or formerly Islamist parties (such as PKS of Indonesia, AKP of Turkey, and PAS of Malaysia) mentioned above, there has been a social/religious and sometimes political backlash against Islamist rule in countries like Turkey, Iran, and Sudan (Mustafa Akyol).[308]

Writing in 2020, Mustafa Akyol argues there has been a strong reaction by many Muslims against political Islam, including a weakening of religious faith—the very thing Islamism was intended to strengthen. He suggests this backlash against Islamism among Muslim youth has come from all the "terrible things" that have happened in the Arab world in the twenty first century "in the name of Islam"—such as the "sectarian civil wars in Syria, Iraq and Yemen".[308]

Polls taken by Arab Barometer in six Arab countries – Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia, Jordan, Iraq and Libya – found "Arabs are losing faith in religious parties and leaders." In 2018–19, in all six countries, fewer than 20% of those asked whether they trusted Islamist parties answered in the affirmative. That percentage had fallen (in all six countries) from when the same question was asked in 2012–14. Mosque attendance also declined more than 10 points on average, and the share of those Arabs describing themselves as "not religious" went from 8% in 2013 to 13% in 2018–19.[309][308] In Syria, Sham al-Ali reports "Rising apostasy among Syrian youths".[310][308]

Writing in 2021, Nader Hashemi notes that in Iraq, Sudan, Tunisia, Egypt, Gaza, Jordan and other places were Islamist parties have come to power or campaigned to, "one general theme stands. The popular prestige of political Islam has been tarnished by its experience with state power."[311][307]In Iran, hardline Ayatollah Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah Yazdi has complained, "Iranians are evading religious teachings and turning to secularism."[312]Even Islamist terrorism was in decline and tended "to be local" rather than pan-Islamic. As of 2021, Al-Qaeda consisted of "a bunch of militias" with no effective central command (Fareed Zakaria).[311]

Rise of Islamism by country[edit]

Response[edit]

Criticism[edit]

Islamism, or elements of Islamism, have been criticized on numerous grounds, including repression of free expression and individual rights, rigidity, hypocrisy, anti-semitism,[313] misinterpreting the Quran and Sunnah, lack of true understanding of and innovations to Islam (bid'ah) – notwithstanding proclaimed opposition to any such innovation by Islamists.

Counter-response[edit]

Правительство США предпринимает усилия по противодействию воинствующему исламизму ( джихадизму ) с 2001 года. Эти усилия были сосредоточены в США вокруг программ общественной дипломатии, проводимых Государственным департаментом. Раздавались призывы создать в США независимое агентство с конкретной миссией по подрыву джихадизма. Кристиан Уитон, чиновник администрации Джорджа Буша-младшего , призвал к созданию нового агентства, занимающегося ненасильственной практикой «политической войны», направленной на подрыв идеологии. [314] U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates called for establishing something similar to the defunct U.S. Information Agency, which was charged with undermining the communist ideology during the Cold War.[315]

Партии и организации [ править ]

См. также [ править ]

Ссылки [ править ]

Примечания [ править ]

- ^ Таким образом, салафитский джихадизм предусматривает исламистские цели, сродни целям салафизма, а не традиционный исламизм, примером которого являются Братья-мусульмане середины 20-го века, которые салафитские джихадисты считают чрезмерно умеренными и лишенными буквального толкования Священных Писаний. [140]

- ^ «Изучение исламистских движений часто неявно подразумевало изучение суннитских исламистских движений. ... большинство исследований [исламизма] касаются различных форм суннитского исламизма, тогда как «Другие исламисты» - различные виды шиитских исламистских групп - получили гораздо меньше внимания...». [86]

- ^ 85% мусульман-шиитов, которые составляют 10–15% мусульман.

- ^ Шиитские исламистские группы существуют вне идеологии Исламской Республики - , Мухаммад Бакир ас-Садр и Исламская партия Дава на иракском языке). например [86]

- ^ Радикализм возник в результате попыток интегрировать социализм / марксизм в исламизм - со стороны Али Шариати и партизан Народных моджахедов ; или поддерживающие Хомейни клерикальные радикалы (такие как Али Акбар Мохташами-Пур ); [149] или от попыток Хомейни противостоять привлекательности социализма/марксизма для молодежи с помощью исламской версии радикальной популистской риторики и образов классовой борьбы. [150] [151] Ранняя радикальная политика правительства позже была отменена Исламской Республикой.

- ^ Официальные истории и пропаганда отмечаютсясвященнослужители (а не светские деятели, такие как Мохаммад Мосаддык ) как защитники ислама и Ирана от империализма и королевского деспотизма. [152]

- ^ образуя большинство в странах Ирана, Ирака, Бахрейна, Азербайджана, [166] и значительные меньшинства в Афганистане, Индии, Кувейте, Ливане, Пакистане, Катаре, Сирии, Саудовской Аравии и Объединенных Арабских Эмиратах. [167]

- ^ «... революционное шиитское движение, единственное, которое пришло к власти посредством настоящей исламской революции; поэтому оно стало отождествляться с иранским государством, которое использовало его как инструмент в своей стратегии завоевания региональной власти. , хотя многочисленность шиитских группировок отражает местные особенности (в Ливане, Афганистане или Ираке) в такой же степени, как и фракционную борьбу в Тегеране». [147]

- ^ По словам Джона Армаджани, книги Джона Армаджани, выступающей за Исламскую республику: «Правительство Ирана пыталось присоединиться к мусульманам-шиитам в различных странах, таких как Ирак и Ливан, [оно] ... пыталось религиозно питать и политически мобилизовать этих Шииты в принципе не только из-за желания иранского правительства защитить Иран от внешних угроз». [170]

- ↑ Даже после эскалации враждебности между суннитами и шиитами иранские лидеры часто «прямо шли на такие вещи, которые делают их очень непопулярными на Западе и очень популярными на арабских улицах. Поэтому президент Ирана [Махмуд] Ахмадинежад начал нападать на Израиль и ставить под сомнение Холокост». [274]

- ^ Хомейни никогда не руководил шиитскими святынями и не посещал их. [278] (думается, потому что он считал, что ислам должен быть связан с исламским правом , [278] и его революция (которую он считал) имела «равную значимость» с битвой при Кербеле , где принял мученическую смерть имам Хусейн ). [279]

Цитаты [ править ]

- ^ «Исламизм» . Оксфордский справочник . Архивировано из оригинала 25 августа 2023 года . Проверено 25 августа 2023 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Эйкмайер, Дейл (2007). «Кутбизм: идеология исламского фашизма» . Ежеквартальный журнал военного колледжа армии США: параметры . 37 (1): 85–97. дои : 10.55540/0031-1723.2340 .

- ^ Соаге, Ана Белен. «Введение в политический ислам». Религиозный компас 3.5 (2009): 887–96.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Бургат, Франсуа, «Исламское движение в Северной Африке», Техасский университет, 1997, стр. 39–41, 67–71, 309.