Хезболла

Исламское сопротивление в Ливане Исламское сопротивление в Ливане Аль Мукавама Аль Ислам в Лубнане | |

|---|---|

| |

| Генеральный секретарь | Сайед Хасан Насралла |

| Основатель | Субхи аль-Туфайли Сайед Аббас аль-Мусави |

| Основан | 1985 год (официально) |

| Headquarters | Beirut, Lebanon |

| Parliamentary group | Loyalty to the Resistance Bloc[1] |

| Paramilitary wing | Jihad Council Lebanese Resistance Brigades |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Syncretic[21] |

| Religion | Shia Islam |

| National affiliation | March 8 Alliance |

| International affiliation | Axis of Resistance |

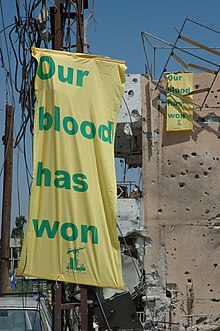

| Colours | Yellow and green |

| Slogan | فَإِنَّ حِزْبَ ٱللَّهِ هُمُ ٱلْغَالِبُونَ (Arabic) "Verily the Party of God are they that shall be triumphant" [Quran 5:56] |

| Seats in the Parliament[22] | 15 / 128 (12%) |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| www | |

| Hezbollah | |

|---|---|

| Dates of operation | 1982–present |

| Group(s) |

|

| Headquarters | Lebanon |

| Size | 100,000 (according to Hassan Nasrallah)[24][25][26] |

| Allies | State allies:

Non-state allies:

See more |

| Opponents | State opponents: Non-state opponents: |

| Battles and wars | See details |

| Designated as a terrorist group by | See here |

| Part of a series on |

| Hezbollah |

|---|

Хезболла ( / ˌ h ɛ z b ə ˈ l ɑː / , [43] / ˌ x ɛ z -/ ; Арабский : حزب الله , латинизированный : Хизбу 'ллах , букв. « Партия Аллаха » или « Партия Бога » ) [44] — ливанская шиитская исламистская политическая партия и боевая группировка, [45] [46] возглавляется с 1992 года ее генеральным секретарем Хасаном Насраллой . Хезболлы Военизированное крыло — Совет Джихада . [47] а ее политическим крылом является партия «Лояльность Блоку Сопротивления» в ливанском парламенте . Ее вооруженная сила оценивается как эквивалент армии средней численности. [48]

«Хезболла» была создана ливанскими священнослужителями прежде всего для борьбы с израильским вторжением в Ливан в 1982 году . [14] Она приняла модель, предложенную аятоллой Хомейни после иранской революции 1979 года, а основатели партии приняли название «Хезболла», выбранное Хомейни. С тех пор тесные связи . установились между Ираном и «Хезболлой» [49] Организация была создана при поддержке 1500 инструкторов Корпуса стражей исламской революции (КСИР). [50] и объединил различные ливанские шиитские группы в единую организацию для сопротивления бывшей израильской оккупации Южного Ливана . [51] [52] [14] [53] During the Lebanese Civil War, Hezbollah's 1985 manifesto listed its objectives as the expulsion of "the Americans, the French and their allies definitely from Lebanon, putting an end to any colonialist entity on our land".[54] Hezbollah also participated in the 1985–2000 South Lebanon conflict against the South Lebanon Army (SLA) and Israel Defense Forces (IDF), and fought again with the IDF in the 2006 Lebanon War. During the 1990s, Hezbollah also organised volunteers to fight for the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Bosnian War.[55][56][57][58]

Since 1990, Hezbollah has participated in Lebanese politics, in a process which is described as the Lebanonisation of Hezbollah, and it later participated in the government of Lebanon and joined political alliances. After the 2006–08 Lebanese protests[59] and clashes,[60] a national unity government was formed in 2008, with Hezbollah and its opposition allies obtaining 11 of 30 cabinet seats, enough to give them veto power.[61] In August 2008, Lebanon's new cabinet unanimously approved a draft policy statement that recognizes Hezbollah's existence as an armed organization and guarantees its right to "liberate or recover occupied lands" (such as the Shebaa Farms). Hezbollah is part of Lebanon's March 8 Alliance, in opposition to the March 14 Alliance. It maintains strong support among Lebanese Shia Muslims,[62] while Sunnis have disagreed with its agenda.[63][64] Hezbollah also has support in some Christian areas of Lebanon.[65] Since 2012, Hezbollah involvement in the Syrian civil war has seen it join the Syrian government in its fight against the Syrian opposition, which Hezbollah has described as a Zionist plot and a "Wahhabi-Zionist conspiracy" to destroy its alliance with Bashar al-Assad against Israel.[66][67] Between 2013 and 2015, the organisation deployed its militia in both Syria and Iraq to fight or train local militias to fight against the Islamic State.[68][69] In the 2018 Lebanese general election, Hezbollah held 12 seats and its alliance won the election by gaining 70 out of 128 seats in the Parliament of Lebanon.[70][71]

Hezbollah did not disarm after the Israeli withdrawal from South Lebanon, in contravention of the UN Security Council resolution 1701.[72] From 2006, the group's military strength grew significantly,[73][74] to the extent that its paramilitary wing became more powerful than the Lebanese Army.[75][76] Hezbollah has been described as a "state within a state",[77] and has grown into an organization with seats in the Lebanese government, a radio and a satellite TV station, social services and large-scale military deployment of fighters beyond Lebanon's borders.[78][79][80] The group currently receives military training, weapons, and financial support from Iran and political support from Syria,[81] although the sectarian nature of the Syrian war has damaged the group's legitimacy.[78][82][83] In 2021, Nasrallah said the group had 100,000 fighters.[84] Either the entire organization or only its military wing has been designated a terrorist organization by several countries, including by the European Union[85] and, since 2017, also by most member states of the Arab League, with two exceptions – Lebanon, where Hezbollah is one of the country's most influential political parties, and Iraq.[86] Russia does not view Hezbollah as a "terrorist organization" but as a "legitimate socio-political force".[87]

History

Foundation

In 1982, Hezbollah was conceived by Muslim clerics and funded by Iran primarily to fight the Israeli invasion of Lebanon.[14] Its leaders were followers of Ayatollah Khomeini, and its forces were trained and organized by a contingent of 1,500 Revolutionary Guards that arrived from Iran with permission from the Syrian government, which occupied Lebanon's eastern highlands, permitted their transit to a base in the Bekaa valley[50] which was in occupation of Lebanon at the time.

Scholars differ as to when Hezbollah came to be a distinct entity. Various sources list the official formation of the group as early as 1982[88][89][90] whereas Diaz and Newman maintain that Hezbollah remained an amalgamation of various violent Shi'a extremists until as late as 1985.[91] Another version states that it was formed by supporters of Sheikh Ragheb Harb, a leader of the southern Shia resistance killed by Israel in 1984.[92] Regardless of when the name came into official use, a number of Shi'a groups were slowly assimilated into the organization, such as Islamic Jihad, Organization of the Oppressed on Earth and the Revolutionary Justice Organization.[citation needed] These designations are considered to be synonymous with Hezbollah by the US,[93] Israel[94] and Canada.[95]

According to Robert Fisk[96] and Israeli General Shimon Shapira[97] the date of 8 June 1982, two days after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, when 50 Shiite militants ambushed an Israel Defense Forces armored convoy in Khalde south of Beirut, is considered by Hezbollah as the founding myth of the "Islamic Resistance in Lebanon", the group's military wing. It was in this battle, delaying the Israeli advance to Beirut for six days, that the future Hezbollah military chief Mustafa Badreddine made his name as a serious commander.[98] According to Shapira, the lightly armed Shia fighters managed to capture an Israeli armored vehicle on that day and paraded it in the Revolutionary Guards' forward operating base in Baalbek, Eastern Lebanon. Fisk writes:

Down at Khalde, a remarkable phenomenon had taken shape. The Shia militiamen were running on foot into the Israeli gunfire to launch grenades at the Israeli armour, actually moving to within 20 feet of the tanks to open fire at them. Some of the Shia fighters had torn off pieces of their shirts and wrapped them around their heads as bands of martyrdom as the Iranian revolutionary guards had begun doing a year before when they staged their first mass attacks against the Iraqis in the Gulf War a thousand miles to the east. When they set fire to one Israeli armoured vehicle, the gunmen were emboldened to advance further. None of us, I think, realised the critical importance of the events of Khalde that night. The Lebanese Shia were learning the principles of martyrdom and putting them into practice. Never before had we seen these men wear headbands like this; we thought it was another militia affectation but it was not. It was the beginning of a legend which also contained a strong element of truth. The Shia were now the Lebanese resistance, nationalist no doubt but also inspired by their religion. The party of God – in Arabic, the Hezbollah – were on the beaches of Khalde that night.[96]

1980s

Hezbollah emerged in South Lebanon during a consolidation of Shia militias as a rival to the older Amal Movement. Hezbollah played a significant role in the Lebanese civil war, opposing American forces in 1982–83 and opposing Amal and Syria during the 1985–88 War of the Camps. However, Hezbollah's early primary focus was ending Israel's occupation of southern Lebanon[14] following Israel's 1982 invasion and siege of Beirut.[99] Amal, the main Lebanese Shia political group, initiated guerrilla warfare. In 2006, former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak stated, "When we entered Lebanon … there was no Hezbollah. We were accepted with perfumed rice and flowers by the Shia in the south. It was our presence there that created Hezbollah".[100]

Hezbollah waged an asymmetric war using suicide attacks against the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and Israeli targets outside of Lebanon.[101] Hezbollah is reputed to have been among the first Islamic resistance groups in the Middle East to use the tactics of suicide bombing, assassination, and capturing foreign soldiers,[50] as well as murders[102] and hijackings.[103] Hezbollah also employed more conventional military tactics and weaponry, notably Katyusha rockets and other missiles.[102][104] At the end of the Lebanese Civil War in 1990, despite the Taif Agreement asking for the "disbanding of all Lebanese and non-Lebanese militias," Syria, which controlled Lebanon at that time, allowed Hezbollah to maintain their arsenal and control Shia areas along the border with Israel.[105]

After 1990

In the 1990s, Hezbollah transformed from a revolutionary group into a political one, in a process which is described as the Lebanonisation of Hezbollah. Unlike its uncompromising revolutionary stance in the 1980s, Hezbollah conveyed a lenient stance towards the Lebanese state.[106]

In 1992, Hezbollah decided to participate in elections, and Ali Khamenei, supreme leader of Iran, endorsed it. Former Hezbollah secretary general, Subhi al-Tufayli, contested this decision, which led to a schism in Hezbollah. Hezbollah won all twelve seats which were on its electoral list. At the end of that year, Hezbollah began to engage in dialog with Lebanese Christians. Hezbollah regards cultural, political, and religious freedoms in Lebanon as sanctified, although it does not extend these values to groups who have relations with Israel.[107]

In 1997, Hezbollah formed the multi-confessional Lebanese Brigades to Fighting the Israeli Occupation in an attempt to revive national and secular resistance against Israel, thereby marking the "Lebanonisation" of resistance.[108]

Islamic Jihad Organization (IJO)

Whether the Islamic Jihad Organization (IJO) was a nom de guerre used by Hezbollah or a separate organization, is disputed. According to certain sources, IJO was identified as merely a "telephone organization",[109][110] and whose name was "used by those involved to disguise their true identity."[111][112][113][114][115] Hezbollah reportedly also used another name, "Islamic Resistance" (al-Muqawama al-Islamiyya), for attacks against Israel.[116]

A 2003 American court decision found IJO was the name used by Hezbollah for its attacks in Lebanon, parts of the Middle East and Europe.[117] The US,[118] Israel[119] and Canada[95] consider the names "Islamic Jihad Organization", "Organization of the Oppressed on Earth" and the "Revolutionary Justice Organization" to be synonymous with Hezbollah.

Ideology

The ideology of Hezbollah has been summarized as Shi'i radicalism;[120][121][122] Hezbollah follows the Islamic Shi'a theology developed by Iranian leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.[123] Hezbollah was largely formed with the aid of the Ayatollah Khomeini's followers in the early 1980s in order to spread Islamic revolution[124] and follows a distinct version of Islamic Shi'a ideology (Wilayat al-faqih or Guardianship of the Islamic Jurists) developed by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, leader of the "Islamic Revolution" in Iran.[125][119] Although Hezbollah originally aimed to transform Lebanon into a formal Faqihi Islamic republic, this goal has been abandoned in favor of a more inclusive approach.[14]

1985 manifesto

On 16 February 1985, Sheik Ibrahim al-Amin issued Hezbollah's manifesto. The ideology presented in it was described as radical.[by whom?] Its first objective was to fight against what Hezbollah described as American and Israeli imperialism, including the Israeli occupation of Southern Lebanon and other territories. The second objective was to gather all Muslims into an "ummah", under which Lebanon would further the aims of the 1979 Revolution of Iran. It also declared it would protect all Lebanese communities, excluding those that collaborated with Israel, and support all national movements—both Muslim and non-Muslim—throughout the world.[which?] The ideology has since evolved, and today Hezbollah is a left-wing political entity focused on social injustice.[126][dubious – discuss]

Translated excerpts from Hezbollah's original 1985 manifesto read:

We are the sons of the umma (Muslim community) ...... We are an ummah linked to the Muslims of the whole world by the solid doctrinal and religious connection of Islam, whose message God wanted to be fulfilled by the Seal of the Prophets, i.e., Prophet Muhammad. ... As for our culture, it is based on the Holy Quran, the Sunna and the legal rulings of the faqih who is our source of imitation ...[54]

Attitudes, statements, and actions concerning Israel and Zionism

From the inception of Hezbollah to the present,[54][127] the elimination of the State of Israel has been one of Hezbollah's primary goals. Some translations of Hezbollah's 1985 Arabic-language manifesto state that "our struggle will end only when this entity [Israel] is obliterated".[54] According to Hezbollah's Deputy-General, Naim Qassem, the struggle against Israel is a core belief of Hezbollah and the central rationale of Hezbollah's existence.[128]

Hezbollah says that its continued hostilities against Israel are justified as reciprocal to Israeli operations against Lebanon and as retaliation for what they claim is Israel's occupation of Lebanese territory.[129][130][131] Israel withdrew from Lebanon in 2000, and their withdrawal was verified by the United Nations as being in accordance with resolution 425 of 19 March 1978, however Lebanon considers the Shebaa farms—a 26 km2 (10 sq mi) piece of land captured by Israel from Syria in the 1967 war and considered by the UN to be Syrian territory occupied by Israel—to be Lebanese territory.[132][133] Finally, Hezbollah considers Israel to be an illegitimate state. For these reasons, it justifies its actions as acts of defensive jihad.[134]

If they go from Shebaa, we won't stop fighting them. ... Our goal is to liberate the 1948 borders of Palestine, ... The Jews who survive this war of liberation can go back to Germany or wherever they came from. However, that the Jews who lived in Palestine before 1948 will be 'allowed to live as a minority and they will be cared for by the Muslim majority.'

— Hezbollah's spokesperson Hassan Ezzedin, about an Israeli withdrawal from Shebaa Farms[105]

Attitudes and actions concerning Jews and Judaism

Hezbollah officials have said, on rare occasions, that it is only "anti-Zionist" and not anti-Semitic.[19] However, according to scholars, "these words do not hold up upon closer examination". Among other actions, Hezbollah actively engages in Holocaust denial and spreads anti-Semitic conspiracy theories.[19]

Various antisemitic statements have been attributed to Hezbollah officials.[135] Amal Saad-Ghorayeb, a Lebanese political analyst, argues that although Zionism has influenced Hezbollah's anti-Judaism, "it is not contingent upon it because Hezbollah's hatred of Jews is more religiously motivated than politically motivated".[136] Robert S. Wistrich, a historian specializing in the study of anti-Semitism, described Hezbollah's ideology concerning Jews:

The anti-Semitism of Hezbollah leaders and spokesmen combines the image of seemingly invincible Jewish power ... and cunning with the contempt normally reserved for weak and cowardly enemies. Like the Hamas propaganda for holy war, that of Hezbollah has relied on the endless vilification of Jews as 'enemies of mankind,' 'conspiratorial, obstinate, and conceited' adversaries full of 'satanic plans' to enslave the Arabs. It fuses traditional Islamic anti-Judaism with Western conspiracy myths, Third Worldist anti-Zionism, and Iranian Shiite contempt for Jews as 'ritually impure' and corrupt infidels. Sheikh Fadlallah typically insists ... that Jews wish to undermine or obliterate Islam and Arab cultural identity in order to advance their economic and political domination.[137]

Conflicting reports say Al-Manar, the Hezbollah-owned and operated television station, accused either Israel or Jews of deliberately spreading HIV and other diseases to Arabs throughout the Middle East.[138][139][140] Al-Manar was criticized in the West for airing "anti-Semitic propaganda" in the form of a television drama depicting a Jewish world domination conspiracy theory.[141][142][143] The group has been accused by American analysts of engaging in Holocaust denial.[144][145][146] In addition, during its 2006 war, it apologized only for killing Israel's Arabs (i.e., non-Jews).[19]

In November 2009, Hezbollah pressured a private English-language school to drop reading excerpts from The Diary of Anne Frank, a book of the writings from the diary kept by the Jewish child Anne Frank while she was in hiding with her family during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands.[147] This was after Hezbollah's Al-Manar television channel complained, asking how long Lebanon would "remain an open arena for the Zionist invasion of education?"[148]

Organization

At the beginning, many Hezbollah leaders maintained that the movement was "not an organization, for its members carry no cards and bear no specific responsibilities,"[149] and that the movement does not have "a clearly defined organizational structure."[150] Today, as Hezbollah scholar Magnus Ranstorp reports, Hezbollah does indeed have a formal governing structure and, in keeping with the principle of Guardianship of the Islamic Jurists (velayat-e faqih), it "concentrate[s] ... all authority and powers" in its religious leaders, whose decisions then "flow from the ulama down the entire community."

The supreme decision-making bodies of the Hezbollah were divided between the Majlis al-Shura (Consultative Assembly) which was headed by 12 senior clerical members with responsibility for tactical decisions and supervision of overall Hizballah activity throughout Lebanon, and the Majlis al-Shura al-Karar (the Deciding Assembly), headed by Sheikh Muhammad Hussein Fadlallah and composed of eleven other clerics with responsibility for all strategic matters. Within the Majlis al-Shura, there existed seven specialized committees dealing with ideological, financial, military and political, judicial, informational and social affairs. In turn, the Majlis al-Shura and these seven committees were replicated in each of Hizballah's three main operational areas (the Beqaa, Beirut, and the South).[151]

Since the Supreme Leader of Iran is the ultimate clerical authority, Hezbollah's leaders have appealed to him "for guidance and directives in cases when Hezbollah's collective leadership [was] too divided over issues and fail[ed] to reach a consensus."[151] After the death of Iran's first Supreme Leader, Khomeini, Hezbollah's governing bodies developed a more "independent role" and appealed to Iran less often.[151] Since the Second Lebanon War, however, Iran has restructured Hezbollah to limit the power of Hassan Nasrallah, and invested billions of dollars "rehabilitating" Hezbollah.[152]

Structurally, Hezbollah does not distinguish between its political/social activities within Lebanon and its military/jihad activities against Israel. "Hezbollah has a single leadership," according to Naim Qassem, Hezbollah's second in command. "All political, social and jihad work is tied to the decisions of this leadership ... The same leadership that directs the parliamentary and government work also leads jihad actions in the struggle against Israel."[153]

In 2010, Iran's parliamentary speaker Ali Larijani said, "Iran takes pride in Lebanon's Islamic resistance movement for its steadfast Islamic stance. Hezbollah nurtures the original ideas of Islamic Jihad." He also instead charged the West with having accused Iran with support of terrorism and said, "The real terrorists are those who provide the Zionist regime with military equipment to bomb the people."[154]

Funding

Funding of Hezbollah comes from the Iranian government, Lebanese business groups, private persons, businessmen, the Lebanese diaspora involved in African diamond exploration, other Islamic groups and countries, and the taxes paid by the Shia Lebanese.[155] Hezbollah says that the main source of its income comes from its own investment portfolios and donations by Muslims.

Western sources maintain that Hezbollah actually receives most of its financial, training, weapons, explosives, political, diplomatic, and organizational aid from Iran and Syria.[105][118][156] Iran is said to have given $400 million between 1983 and 1989 through donation. Due to economic problems, Iran temporarily limited funds to humanitarian actions carried on by Hezbollah.[155] During the late 1980s, when there was extreme inflation due to the collapse of the Lira, it was estimated that Hezbollah was receiving $3–5 million per month from Iran.[157] According to reports released in February 2010, Hezbollah received $400 million from Iran.[158][159][160]

In 2011, Iran earmarked $7 million to Hezbollah's activities in Latin America.[161] Hezbollah has relied also on funding from the Shi'ite Lebanese Diaspora in West Africa, the United States and, most importantly, the Triple Frontier, or tri-border area, along the junction of Paraguay, Argentina, and Brazil.[162] U.S. law enforcement officials have identified an illegal multimillion-dollar cigarette-smuggling fund raising operation[163] and a drug smuggling operation.[164][165][166] Nasrallah has repeatedly denied any links between the South American drug trade and Hezbollah, calling such accusations "propaganda" and attempts "to damage the image of Hezbollah".[167][168]

As of 2018, Iranian monetary support for Hezbollah is estimated at $700 million per annum according to US estimates.[169][170]

The United States has accused members of the Venezuelan government of providing financial aid to Hezbollah.[171]

Social services

Hezbollah organizes and maintains an extensive social development program and runs hospitals, news services, educational facilities, and encouragement of Nikah mut'ah.[158][172] One of its established institutions, Jihad Al Binna's Reconstruction Campaign, is responsible for numerous economic and infrastructure development projects in Lebanon.[173] Hezbollah controls the Martyr's Institute (Al-Shahid Social Association), which pays stipends to "families of fighters who die" in battle.[160] An IRIN news report of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs noted:

Hezbollah not only has armed and political wings—it also boasts an extensive social development program. Hezbollah currently operates at least four hospitals, twelve clinics, twelve schools and two agricultural centres that provide farmers with technical assistance and training. It also has an environmental department and an extensive social assistance program. Medical care is also cheaper than in most of the country's private hospitals and free for Hezbollah members.[158]

According to CNN, "Hezbollah did everything that a government should do, from collecting the garbage to running hospitals and repairing schools."[174] In July 2006, during the war with Israel, when there was no running water in Beirut, Hezbollah was arranging supplies around the city. Lebanese Shiites "see Hezbollah as a political movement and a social service provider as much as it is a militia."[174] Hezbollah also rewards its guerrilla members who have been wounded in battle by taking them to Hezbollah-run amusement parks.[175]

Hezbollah is, therefore, deeply embedded in the Lebanese society.[50]

Political activities

|

|---|

|

Hezbollah along with Amal is one of two major political parties in Lebanon that represent Shiite Muslims.[176] Unlike Amal, whose support is predominantly in Lebanon's south, Hezbollah maintains broad-based support in all three areas of Lebanon with a majority Shia Muslim population: in the south, in Beirut and its surrounding area, and in the northern Beqaa valley and Hirmil region.[177]

Hezbollah holds 14 of the 128 seats in the Parliament of Lebanon and is a member of the Resistance and Development Bloc. According to Daniel L. Byman, it is "the most powerful single political movement in Lebanon."[178] Hezbollah, along with the Amal Movement, represents most of Lebanese Shi'a. Unlike Amal, Hezbollah has not disarmed. Hezbollah participates in the Parliament of Lebanon.

Political alliances

Hezbollah has been one of the main parties of the March 8 Alliance since March 2005. Although Hezbollah had joined the new government in 2005, it remained staunchly opposed to the March 14 Alliance.[179] On 1 December 2006, these groups began a series of political protests and sit-ins in opposition to the government of Prime Minister Fouad Siniora.[59]

In 2006, Michel Aoun and Hassan Nasrallah met in Mar Mikhayel Church, Chiyah, and signed a memorandum of understanding between Free Patriotic Movement and Hezbollah organizing their relation and discussing Hezbollah's disarmament with some conditions. The agreement also discussed the importance of having normal diplomatic relations with Syria and the request for information about the Lebanese political prisoners in Syria and the return of all political prisoners and diaspora in Israel. After this event, Aoun and his party became part of the March 8 Alliance.[180]

On 7 May 2008, Lebanon's 17-month-long political crisis spiraled out of control. The fighting was sparked by a government move to shut down Hezbollah's telecommunication network and remove Beirut Airport's security chief over alleged ties to Hezbollah. Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah said the government's decision to declare the group's military telecommunications network illegal was a "declaration of war" on the organization, and demanded that the government revoke it.[181]

Hezbollah-led opposition fighters seized control of several West Beirut neighborhoods from Future Movement militiamen loyal to the backed government, in street battles that left 11 dead and 30 wounded. The opposition-seized areas were then handed over to the Lebanese Army.[60] The army also pledged to resolve the dispute and has reversed the decisions of the government by letting Hezbollah preserve its telecoms network and re-instating the airport's security chief.[182]

At the end, rival Lebanese leaders reached consensus over Doha Agreement on 21 May 2008, to end the 18-month political feud that exploded into fighting and nearly drove the country to a new civil war.[183] On the basis of this agreement, Hezbollah and its opposition allies were effectively granted veto power in Lebanon's parliament. At the end of the conflicts, National unity government was formed by Fouad Siniora on 11 July 2008, with Hezbollah controlling one ministerial and eleven of thirty cabinet places.[61]

In 2018 Lebanese general election, Hezbollah general secretary Hassan Nasrallah presented the names of the 13 Hezbollah candidates.[184] On 22 March 2018, Nasrallah issued a statement outlining the main priorities for the parliamentary bloc of the party, Loyalty to the Resistance, in the next parliament.[185] He stated that rooting out corruption would be the foremost priority of the Loyalty to the Resistance bloc.[185] The electoral slogan of the party was 'We will construct and we will protect'.[186] Finally Hezbollah held 12 seats and its alliance won the election by gaining 70 out of 128 seats of Parliament of Lebanon.[70][71]

Media operations

Hezbollah operates a satellite television station, Al-Manar TV ("the Lighthouse"), and a radio station, al-Nour ("the Light").[187] Al-Manar broadcasts from Beirut, Lebanon.[187] Hezbollah launched the station in 1991[188] with the help of Iranian funds.[189] Al-Manar, the self-proclaimed "Station of the Resistance," (qanat al-muqawama) is a key player in what Hezbollah calls its "psychological warfare against the Zionist enemy"[189][190] and an integral part of Hezbollah's plan to spread its message to the entire Arab world.[189] Hezbollah has a weekly publication, Al Ahd, which was established in 1984.[191] It is the only media outlet which is openly affiliated with the organization.[191]

Hezbollah's television station Al-Manar airs programming designed to inspire suicide attacks in Gaza, the West Bank, and Iraq.[105][188][192] Al-Manar's transmission in France is prohibited due to its promotion of Holocaust denial, a criminal offense in France.[193] The United States lists Al-Manar television network as a terrorist organization.[194] Al-Manar was designated as a "Specially Designated Global Terrorist entity," and banned by the United States in December 2004.[195] It has also been banned by France, Spain and Germany.[196][197]

Materials aimed at instilling principles of nationalism and Islam in children are an aspect of Hezbollah's media operations.[198] The Hezbollah Central Internet Bureau released two video games – Special Force in 2003 and a sequel, Special Force 2: Tale of the Truthful Pledge, in 2007 – in which players are rewarded with points and weapons for killing Israeli soldiers.[199] In 2012, Al-Manar aired a television special praising an 8-year-old boy who raised money for Hezbollah and said: "When I grow up, I will be a communist resistance warrior with Hezbollah, fighting the United States and Israel, I will tear them to pieces and drive them out of Lebanon, the Golan and Palestine, which I love very dearly."[200]

Secret services

Hezbollah's secret services have been described as "one of the best in the world", and have even infiltrated the Israeli army. Hezbollah's secret services collaborate with the Lebanese intelligence agencies.[155]

In the summer of 1982, Hezbollah's Special Security Apparatus was created by Hussein al-Khalil, now a "top political adviser to Nasrallah";[201] while Hezbollah's counterintelligence was initially managed by Iran's Quds Force,[202]: 238 the organization continued to grow during the 1990s. By 2008, scholar Carl Anthony Wege writes, "Hizballah had obtained complete dominance over Lebanon's official state counterintelligence apparatus, which now constituted a Hizballah asset for counterintelligence purposes."[203]: 775 This close connection with Lebanese intelligence helped bolster Hezbollah's financial counterintelligence unit.[203]: 772, 775

According to Ahmad Hamzeh, Hezbollah's counterintelligence service is divided into Amn al-Muddad, responsible for "external" or "encounter" security; and Amn al-Hizb, which protects the organization's integrity and its leaders. According to Wege, Amn al-Muddad "may have received specialized intelligence training in Iran and possibly North Korea".[203]: 773–774 The organization also includes a military security component, as well as an External Security Organization (al-Amn al-Khariji or Unit 910) that operates covertly outside Lebanon.[202]: 238

Successful Hezbollah counterintelligence operations include thwarting the CIA's attempted kidnapping of foreign operations chief Hassan Ezzeddine in 1994, the 1997 manipulation of a double agent that led to the Ansariya ambush, and the 2000 kidnapping of alleged Mossad agent Elhanan Tannenbaum.[203]: 773 In 2006, Hezbollah collaborated with the Lebanese government to detect Adeeb al-Alam, a former colonel, as an Israeli spy.[203]: 774 Hezbollah recruited IDF Lieutenant Colonel Omar al-Heib, who was convicted in 2006 of conducting surveillance for Hezbollah.[203]: 776 In 2009, Hezbollah apprehended Marwan Faqih, a garage owner who installed tracking devices in Hezbollah-owned vehicles.[203]: 774

Hezbollah's counterintelligence apparatus uses electronic surveillance and intercept technologies. By 2011, Hezbollah counterintelligence began to use software to analyze cellphone data and detect espionage. Suspicious callers were then subjected to conventional surveillance. In the mid-1990s, Hezbollah was able to "download unencrypted video feeds from Israeli drones,"[203]: 777 and Israeli SIGINT efforts intensified after the 2000 withdrawal from Lebanon. With possible help from Iran and the Russian FSB, Hezbollah augmented its electronic counterintelligence capabilities, and succeeded in 2008 in detecting Israeli bugs near Mount Sannine and in the organization's fiber optic network.[203]: 774, 777–778

Armed strength

Hezbollah does not reveal its armed strength. The Dubai-based Gulf Research Centre estimated in 2006 that Hezbollah's armed wing comprises 1,000 full-time Hezbollah members, along with a further 6,000–10,000 volunteers.[204] According to the Iranian Fars News Agency, Hezbollah has up to 65,000 fighters.[205] In October 2023, Al Jazeera cited Hezbollah expert Nicholas Blanford as estimating that Hezbollah has at least 60,000 fighters, including full-time and reservists, and that it had increased its stockpile of missiles from 14,000 in 2006 to about 150,000.[43] It is often described as more militarily powerful than the Lebanese Army.[76][206][75] Israeli commander Gui Zur called Hezbollah "by far the greatest guerrilla group in the world".[207]

In 2010, Hezbollah was believed to have 45,000 rockets.[208] Israeli Defense Forces Chief of Staff Gadi Eisenkot said that Hezbollah possesses "tens of thousands" of long- and short-range rockets, drones, advanced computer encryption capabilities, as well as advanced defense capabilities like the SA-6 anti-aircraft missile system.[209]

Hezbollah possesses the Katyusha-122 rocket, which has a range of 29 km (18 mi) and carries a 15 kg (33 lb) warhead. Hezbollah possesses about 100 long-range missiles. They include the Iranian-made Fajr-3 and Fajr-5, the latter with a range of 75 km (47 mi), enabling it to strike the Israeli port of Haifa, and the Zelzal-1, with an estimated 150 km (93 mi) range, which can reach Tel Aviv. Fajr-3 missiles have a range of 40 km (25 mi) and a 45 kg (99 lb) warhead. Fajr-5 missiles, extend to 72 km (45 mi), also hold 45 kg (99 lb) warheads.[204] It was reported that Hezbollah is in possession of Scud missiles that were provided to them by Syria.[210] Syria denied the reports.[211]

According to various reports, Hezbollah is armed with anti-tank guided missiles, namely, the Russian-made AT-3 Sagger, AT-4 Spigot, AT-5 Spandrel, AT-13 Saxhorn-2 'Metis-M', АТ-14 Spriggan 'Kornet', Iranian-made Ra'ad (version of AT-3 Sagger), Towsan (version of AT-5 Spandrel), Toophan (version of BGM-71 TOW), and European-made MILAN missiles. These weapons have been used against IDF soldiers, causing many of the deaths during the 2006 Lebanon War.[212] US courts said that North Korea provided armaments to Hezbollah during the 2006 war.[213] A small number of Saeghe-2s, an Iranian-made version of the M47 Dragon, were also used in the war.[214]

For air defense, Hezbollah has anti-aircraft weapons that include the ZU-23 artillery and the man-portable, shoulder-fired SA-7 and SA-18 surface-to-air missile (SAM).[215] One of the most effective weapons deployed by Hezbollah has been the C-802 anti-ship missile.[216]

In April 2010, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates claimed that Hezbollah has far more missiles and rockets than the majority of countries, and said that Syria and Iran are providing weapons to the organization. Israel also claims that Syria is providing the organization with these weapons. Syria has denied supplying these weapons and views these claims as an Israeli excuse for an attack.[citation needed] Leaked cables from American diplomats suggest that the United States has been trying unsuccessfully to prevent Syria from "supplying arms to Hezbollah in Lebanon", and that Hezbollah has "amassed a huge stockpile (of arms) since its 2006 war with Israel"; the arms were described as "increasingly sophisticated."[217] Gates added that Hezbollah is possibly armed with chemical or biological weapons, as well as 65-mile (105 km) anti-ship missiles that could threaten U.S. ships.[218]

As of 2017[update], the Israeli government believe Hezbollah had an arsenal of nearly 150,000 rockets stationed on its border with Lebanon.[219] Some of these missiles are said to be capable of penetrating cities as far away as Eilat.[220] The IDF has accused Hezbollah of storing these rockets beneath hospitals, schools, and civilian homes.[220] Hezbollah has used drones against Israel, by penetrating air defense systems, in a report verified by Nasrallah, who added, "This is only part of our capabilities".[221]

Israeli military officials and analysts have drawn attention to the experience and weaponry Hezbollah would have gained from the involvement of thousands of its fighters in the Syrian Civil War. "This kind of experience cannot be bought," said Gabi Siboni, director of the military and strategic affairs program at the Institute for National Security Studies at Tel Aviv University. "It is an additional factor that we will have to deal with. There is no replacement for experience, and it is not to be scoffed at."[222]

On 13 July 2019, Seyyed Hassan Nasrallah, in an interview broadcast on Hezbollah's Al-Manar television, said "Our weapons have been developed in both quality and quantity, we have precision missiles and drones," he illustrated strategic military and civilian targets on the map of Israel and stated, Hezbollah is able to launch Ben Gurion Airport, arms depots, petrochemical, and water desalinization plants, and the Ashdod port, Haifa's ammonia storage which would cause "tens of thousands of casualties".[223]

Military activities

Hezbollah has a military branch known as the Jihad Council,[47] one component of which is Al-Muqawama al-Islamiyya ("The Islamic Resistance"), and is the possible sponsor of a number of lesser-known militant groups, some of which may be little more than fronts for Hezbollah itself, including the Organization of the Oppressed, the Revolutionary Justice Organization, the Organization of Right Against Wrong, and Followers of the Prophet Muhammad.[118]

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1559 called for the disarmament of militia[224] with the Taif agreement at the end of the Lebanese civil war. Hezbollah denounced, and protested against, the resolution.[225] The 2006 military conflict with Israel has increased the controversy. Failure to disarm remains a violation of the resolution and agreement as well as subsequent United Nations Security Council Resolution 1701.[226] Since then both Israel and Hezbollah have asserted that the organization has gained in military strength.[74]

A Lebanese public opinion poll taken in August 2006 shows that most of the Shia did not believe that Hezbollah should disarm after the 2006 Lebanon war, while the majority of Sunni, Druze and Christians believed that they should.[227] The Lebanese cabinet, under president Michel Suleiman and Prime Minister Fouad Siniora, guidelines state that Hezbollah enjoys the right to "liberate occupied lands."[228] In 2009, a Hezbollah commander, speaking on condition of anonymity, said, "[W]e have far more rockets and missiles [now] than we did in 2006."[229]

Lebanese Resistance Brigades

| Lebanese Resistance Brigades Saraya al-Moukawama al-Lubnaniyya | |

|---|---|

| سرايا المقاومة اللبنانية | |

| |

| Leaders | Mohammed Aknan (Beirut) Mohammad Saleh (Sidon) † |

| Dates of operation | 1998–2000 2009–present |

| Active regions | Southern Lebanon, mainly Sidon |

| Part of | Hezbollah |

| Allies | March 8 Alliance[230] |

| Opponents | SLA Fatah al-Islam Jund al-Sham |

| Battles and wars | Battle of Sidon (2013) |

The Lebanese Resistance Brigades (Arabic: سرايا المقاومة اللبنانية, romanized: Sarāyā l-Muqāwama al-Lubnāniyya), also known as the Lebanese Brigades to Resist the Israeli Occupation, were formed by Hezbollah in 1997 as a multifaith (Christian, Druze, Sunni and Shia) volunteer force to combat the Israeli occupation of Southern Lebanon. With the Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000, the organization was disbanded.[231]

In 2009, the Resistance Brigades were reactivated, mainly comprising Sunni supporters from the southern city of Sidon. Its strength was reduced in late 2013 from 500 to 200–250 due to residents' complaints about some fighters of the group exacerbating tensions with the local community.[232]

The beginning of its military activities: the South Lebanon conflict

Hezbollah has been involved in several cases of armed conflict with Israel:During the 1982–2000 South Lebanon conflict, Hezbollah waged a guerrilla campaign against Israeli forces occupying Southern Lebanon. In 1982, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was based in Southern Lebanon and was firing Katyusha rockets into northern Israel from Lebanon. Israel invaded Lebanon to evict the PLO, and Hezbollah became an armed organization to expel the Israelis.[105] Hezbollah's strength was enhanced by the dispatching of one thousand to two thousand members of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards and the financial backing of Iran.[233][234][235]

Iranian clerics, most notably Fzlollah Mahallati supervised this activity.[236] It became the main politico-military force among the Shia community in Lebanon and the main arm of what became known later as the Islamic Resistance in Lebanon. With the collapse of the SLA, and the rapid advance of Hezbollah forces, Israel withdrew on 24 May 2000 six weeks before the announced 7 July date."[103]

Hezbollah held a victory parade, and its popularity in Lebanon rose.[237] Israel withdrew in accordance with 1978's United Nations Security Council Resolution 425.[132] Hezbollah and many analysts considered this a victory for the movement, and since then its popularity has been boosted in Lebanon.[237]

Alleged suicide attacks

Between 1982 and 1986, there were 36 suicide attacks in Lebanon directed against American, French and Israeli forces by 41 individuals, killing 659.[101] Hezbollah denies involvement in some of these attacks, though it has been accused of being involved or linked to some or all of these attacks:[238][239]

- The 1982–1983 Tyre headquarters bombings

- The April 1983 U.S. Embassy bombing, by the Islamic Jihad Organization.[240]

- The 1983 Beirut barracks bombing, by the Islamic Jihad Organization, that killed 241 U.S. marines, 58 French paratroopers and 6 civilians at the US and French barracks in Beirut.[241]

- The 1983 Kuwait bombings in collaboration with the Iraqi Dawa Party.[242]

- The 1984 United States embassy annex bombing, killing 24.[243]

- A spate of attacks on IDF troops and SLA militiamen in southern Lebanon.[101]

- Hijacking of TWA Flight 847 in 1985.[241]

- The Lebanon hostage crisis from 1982 to 1992.[244]

Since 1990, terror acts and attempts of which Hezbollah has been blamed include the following bombings and attacks against civilians and diplomats:

- The 1992 Israeli Embassy attack in Buenos Aires, killing 29, in Argentina.[241] Hezbollah operatives boasted of involvement.[245]

- The 1994 AMIA bombing of a Jewish cultural centre, killing 85, in Argentina.[241] Ansar Allah, a Palestinian group closely associated with Hezbollah, claimed responsibility.[245]

- The 1994 AC Flight 901 attack, killing 21, in Panama.[246] Ansar Allah, a Palestinian group closely associated with Hezbollah, claimed responsibility.[245]

- The 1996 Khobar Towers bombing, killing 19 US servicemen.[247]

- In 2002, Singapore accused Hezbollah of recruiting Singaporeans in a failed 1990s plot to attack U.S. and Israeli ships in the Singapore Straits.[248]

- 15 January 2008, bombing of a U.S. Embassy vehicle in Beirut.[249]

- In 2009, a Hezbollah plot in Egypt was uncovered, where Egyptian authorities arrested 49 men for planning attacks against Israeli and Egyptian targets in the Sinai Peninsula.[250]

- The 2012 Burgas bus bombing, killing 6, in Bulgaria. Hezbollah denied responsibility.[251]

- Training Shia insurgents against US troops during the Iraq War.[252]

During the Bosnian War

Hezbollah provided fighters to fight on the Bosnian Muslim side during the Bosnian War, as part of the broader Iranian involvement. "The Bosnian Muslim government is a client of the Iranians," wrote Robert Baer, a CIA agent stationed in Sarajevo during the war. "If it's a choice between the CIA and the Iranians, they'll take the Iranians any day." By war's end, public opinion polls showed some 86 percent Bosnian Muslims had a positive opinion of Iran.[253] In conjunction, Hezbollah initially sent 150 fighters to fight against the Bosnian Serb Army, the Bosnian Muslims' main opponent in the war.[55] All Shia foreign advisors and fighters withdrew from Bosnia at the end of conflict.

Conflict with Israel

On 25 July 1993, following Hezbollah's killing of seven Israeli soldiers in southern Lebanon, Israel launched Operation Accountability, known in Lebanon as the Seven Day War, during which the IDF carried out their heaviest artillery and air attacks on targets in southern Lebanon since 1982. The aim of the operation was to eradicate the threat posed by Hezbollah and to force the civilian population north to Beirut so as to put pressure on the Lebanese Government to restrain Hezbollah.[254] The fighting ended when an unwritten understanding was agreed to by the warring parties. Apparently, the 1993 understanding provided that Hezbollah combatants would not fire rockets at northern Israel, while Israel would not attack civilians or civilian targets in Lebanon.[255]

In April 1996, after continued Hezbollah rocket attacks on Israeli civilians,[256] the Israeli armed forces launched Operation Grapes of Wrath, which was intended to wipe out Hezbollah's base in southern Lebanon. Over 100 Lebanese refugees were killed by the shelling of a UN base at Qana, in what the Israeli military said was a mistake.[257]

Following several days of negotiations, the two sides signed the Grapes of Wrath Understandings on 26 April 1996. A cease-fire was agreed upon between Israel and Hezbollah, which would be effective on 27 April 1996.[258] Both sides agreed that civilians should not be targeted, which meant that Hezbollah would be allowed to continue its military activities against IDF forces inside Lebanon.[258]

2000 Hezbollah cross-border raid

On 7 October 2000, three Israeli soldiers—Adi Avitan, Staff Sgt. Benyamin Avraham, and Staff Sgt. Omar Sawaidwere—were abducted by Hezbollah while patrolling the border between the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights and Lebanon.[259] The soldiers were killed either during the attack or in its immediate aftermath.[260] Israel Defense Minister Shaul Mofaz said that Hezbollah abducted the soldiers and then killed them.[261] The bodies of the slain soldiers were exchanged for Lebanese prisoners in 2004.[260]

2006 Lebanon War

The 2006 Lebanon War was a 34-day military conflict in Lebanon and northern Israel. The principal parties were Hezbollah paramilitary forces and the Israeli military. The conflict was precipitated by a cross-border raid during which Hezbollah kidnapped and killed Israeli soldiers. The conflict began on 12 July 2006 when Hezbollah militants fired rockets at Israeli border towns as a diversion for an anti-tank missile attack on two armored Humvees patrolling the Israeli side of the border fence, killing three, injuring two, and seizing two Israeli soldiers.[262][263]

Israel responded with airstrikes and artillery fire on targets in Lebanon that damaged Lebanese infrastructure, including Beirut's Rafic Hariri International Airport, which Israel said that Hezbollah used to import weapons and supplies,[264] an air and naval blockade,[265] and a ground invasion of southern Lebanon. Hezbollah then launched more rockets into northern Israel and engaged the Israel Defense Forces in guerrilla warfare from hardened positions.[266]

The war continued until 14 August 2006. Hezbollah was responsible for thousands of Katyusha rocket attacks against Israeli civilian towns and cities in northern Israel,[267] which Hezbollah said were in retaliation for Israel's killing of civilians and targeting Lebanese infrastructure.[268] The conflict is believed to have killed 1,191–1,300 Lebanese citizens including combatants[269][270][271][272][273] and 165 Israelis including soldiers.[274]

2010 gas field claims

In 2010, Hezbollah claimed that the Dalit and Tamar gas field, discovered by Noble Energy roughly 50 miles (80 km) west of Haifa in Israeli exclusive economic zone, belong to Lebanon, and warned Israel against extracting gas from them. Senior officials from Hezbollah warned that they would not hesitate to use weapons to defend Lebanon's natural resources. Figures in the March 14 Forces stated in response that Hezbollah was presenting another excuse to hold on to its arms. Lebanese MP Antoine Zahra said that the issue is another item "in the endless list of excuses" meant to justify the continued existence of Hezbollah's arsenal.[275]

2011 attack in Istanbul

In July 2011, Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera reported, based on American and Turkish sources,[276] that Hezbollah was behind a bombing in Istanbul in May 2011 that wounded eight Turkish civilians. The report said that the attack was an assassination attempt on the Israeli consul to Turkey, Moshe Kimchi. Turkish intelligence sources denied the report and said "Israel is in the habit of creating disinformation campaigns using different papers."[276]

2012 planned attack in Cyprus

In July 2012, a Lebanese man was detained by Cyprus police on possible charges relating to terrorism laws for planning attacks against Israeli tourists. According to security officials, the man was planning attacks for Hezbollah in Cyprus and admitted this after questioning. The police were alerted about the man due to an urgent message from Israeli intelligence. The Lebanese man was in possession of photographs of Israeli targets and had information on Israeli airlines flying back and forth from Cyprus, and planned to blow up a plane or tour bus.[277] Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stated that Iran assisted the Lebanese man with planning the attacks.[278]

2012 Burgas attack

Following an investigation into the 2012 Burgas bus bombing terrorist attack against Israeli citizens in Bulgaria, the Bulgarian government officially accused the Lebanese-militant movement Hezbollah of committing the attack.[279] Five Israeli citizens, the Bulgarian bus driver, and the bomber were killed. The bomb exploded as the Israeli tourists boarded a bus from the airport to their hotel.

Tsvetan Tsvetanov, Bulgaria's interior minister, reported that the two suspects responsible were members of the militant wing of Hezbollah; he said the suspected terrorists entered Bulgaria on 28 June and remained until 18 July. Israel had already previously suspected Hezbollah for the attack. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called the report "further corroboration of what we have already known, that Hezbollah and its Iranian patrons are orchestrating a worldwide campaign of terror that is spanning countries and continents."[280] Netanyahu said that the attack in Bulgaria was just one of many that Hezbollah and Iran have planned and carried out, including attacks in Thailand, Kenya, Turkey, India, Azerbaijan, Cyprus and Georgia.[279]

John Brennan, Director of the Central Intelligence Agency, has said that "Bulgaria's investigation exposes Hezbollah for what it is—a terrorist group that is willing to recklessly attack innocent men, women and children, and that poses a real and growing threat not only to Europe, but to the rest of the world."[281] The result of the Bulgarian investigation comes at a time when Israel has been petitioning the European Union to join the United States in designating Hezbollah as a terrorist organization.[281]

2015 Shebaa farms incident

In response to an attack against a military convoy comprising Hezbollah and Iranian officers on 18 January 2015 at Quneitra in south of Syria, Hezbollah launched an ambush on 28 January against an Israeli military convoy in the Israeli-occupied Shebaa Farms with anti-tank missiles against two Israeli vehicles patrolling the border,[282] killing 2 and wounding 7 Israeli soldiers and officers, as confirmed by Israeli military.

2023–present Israel–Hezbollah conflict

On 8 October 2023, Hezbollah launched guided rockets and artillery shells at Israeli-occupied positions in Shebaa Farms during the 2023 Israel–Hamas war. Israel retaliated with drone strikes and artillery fire on Hezbollah positions near the Golan Heights–Lebanon border. The attacks came after Hezbollah expressed support and praise for the Hamas attacks on Israel.[283][284] The clashes have been the largest escalation between the two countries since the 2006 Lebanon War.

Assassination of Rafic Hariri

On 14 February 2005, former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri was killed, along with 21 others, when his motorcade was struck by a roadside bomb in Beirut. He had been PM during 1992–1998 and 2000–2004. In 2009, the United Nations special tribunal investigating the murder of Hariri reportedly found evidence linking Hezbollah to the murder.[285]

In August 2010, in response to notification that the UN tribunal would indict some Hezbollah members, Hassan Nasrallah said Israel was looking for a way to assassinate Hariri as early as 1993 in order to create political chaos that would force Syria to withdraw from Lebanon, and to perpetuate an anti-Syrian atmosphere [in Lebanon] in the wake of the assassination. He went on to say that in 1996 Hezbollah apprehended an agent working for Israel by the name of Ahmed Nasrallah—no relation to Hassan Nasrallah—who allegedly contacted Hariri's security detail and told them that he had solid proof that Hezbollah was planning to take his life. Hariri then contacted Hezbollah and advised them of the situation.[286] Saad Hariri responded that the UN should investigate these claims.[287]

On 30 June 2011, the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, established to investigate the death of Hariri, issued arrest warrants against four senior members of Hezbollah, including Mustafa Badr Al Din.[288] On 3 July, Hassan Nasrallah rejected the indictment and denounced the tribunal as a plot against the party, vowing that the named persons would not be arrested under any circumstances.[289]

Involvement in the Syrian Civil War

Hezbollah has long been an ally of the Ba'ath government of Syria, led by the Al-Assad family. Hezbollah has helped the Syrian government during the Syrian civil war in its fight against the Syrian opposition, which Hezbollah has described as a Zionist plot to destroy its alliance with al-Assad against Israel.[67] Geneive Abdo opined that Hezbollah's support for al-Assad in the Syrian war has "transformed" it from a group with "support among the Sunni for defeating Israel in a battle in 2006" into a "strictly Shia paramilitary force".[290] Hezbollah also fought against the Islamic State.[291][292]

In August 2012, the United States sanctioned Hezbollah for its alleged role in the war.[293] General Secretary Nasrallah denied Hezbollah had been fighting on behalf of the Syrian government, stating in a 12 October 2012, speech that "right from the start the Syrian opposition has been telling the media that Hizbullah sent 3,000 fighters to Syria, which we have denied".[294] However, according to the Lebanese Daily Star newspaper, Nasrallah said in the same speech that Hezbollah fighters helped the Syrian government "retain control of some 23 strategically located villages [in Syria] inhabited by Shiites of Lebanese citizenship". Nasrallah said that Hezbollah fighters have died in Syria doing their "jihadist duties".[295]

In 2012, Hezbollah fighters crossed the border from Lebanon and took over eight villages in the Al-Qusayr District of Syria.[296] On 16–17 February 2013, Syrian opposition groups claimed that Hezbollah, backed by the Syrian military, attacked three neighboring Sunni villages controlled by the Free Syrian Army (FSA). An FSA spokesman said, "Hezbollah's invasion is the first of its kind in terms of organisation, planning and coordination with the Syrian regime's air force". Hezbollah said three Lebanese Shiites, "acting in self-defense", were killed in the clashes with the FSA.[296][297] Lebanese security sources said that the three were Hezbollah members.[298] In response, the FSA allegedly attacked two Hezbollah positions on 21 February; one in Syria and one in Lebanon. Five days later, it said it destroyed a convoy carrying Hezbollah fighters and Syrian officers to Lebanon, killing all the passengers.[299]

In January 2013, a weapons convoy carrying SA-17 anti-aircraft missiles to Hezbollah was destroyed allegedly by the Israeli Air Force. A nearby research center for chemical weapons was also damaged. A similar attack on weapons destined for Hezbollah occurred in May of the same year.

The leaders of the March 14 alliance and other prominent Lebanese figures called on Hezbollah to end its involvement in Syria and said it is putting Lebanon at risk.[300] Subhi al-Tufayli, Hezbollah's former leader, said "Hezbollah should not be defending the criminal regime that kills its own people and that has never fired a shot in defense of the Palestinians." He said "those Hezbollah fighters who are killing children and terrorizing people and destroying houses in Syria will go to hell".[301]

The Consultative Gathering, a group of Shia and Sunni leaders in Baalbek-Hermel, also called on Hezbollah not to "interfere" in Syria. They said, "Opening a front against the Syrian people and dragging Lebanon to war with the Syrian people is very dangerous and will have a negative impact on the relations between the two."[298] Walid Jumblatt, leader of the Progressive Socialist Party, also called on Hezbollah to end its involvement[300] and claimed that "Hezbollah is fighting inside Syria with orders from Iran."[302]

Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi condemned Hezbollah by saying, "We stand against Hezbollah in its aggression against the Syrian people. There is no space or place for Hezbollah in Syria."[303] Support for Hezbollah among the Syrian public has weakened since the involvement of Hezbollah and Iran in propping up the Assad regime during the civil war.[304][better source needed]

On 12 May 2013, Hezbollah with the Syrian army attempted to retake part of Qusayr.[305] In Lebanon, there has been "a recent increase in the funerals of Hezbollah fighters" and "Syrian rebels have shelled Hezbollah-controlled areas."[305]

On 25 May 2013, Nasrallah announced that Hezbollah is fighting in the Syrian Civil War against Islamic extremists and "pledged that his group will not allow Syrian militants to control areas that border Lebanon".[306] He confirmed that Hezbollah was fighting in the strategic Syrian town of Al-Qusayr on the same side as Assad's forces.[306] In the televised address, he said, "If Syria falls in the hands of America, Israel and the takfiris, the people of our region will go into a dark period."[306]

Involvement in Iranian-led intervention in Iraq

Beginning in July 2014, Hezbollah sent an undisclosed number of technical advisers and intelligence analysts to Baghdad in support of the Iranian intervention in Iraq (2014–present). Shortly thereafter, Hezbollah commander Ibrahim al-Hajj was reported killed in action near Mosul.[307]

Latin America operations

Hezbollah operations in South America began in the late 20th century, centered around the Arab population which had moved there following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and the 1985 Lebanese Civil War.[308] One particular form of alleged activity is money laundering.[309] The Los Angeles Times said that the group was more active in the 1990s, especially during the 1992 Israeli embassy bombing in Argentina, though its relevance grew more unclear as time progressed.[310] Vox writes that following the adoption of the Patriot Act in 2001, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) would promote the term of narcoterrorism and arrest individuals with no prior history of being involved in terrorism, suggesting skepticism towards the reports of large-scale collusion between alleged terrorist groups and cartels.[311]

In 2002, Hezbollah was reported to be openly operating in Ciudad del Este, Paraguay.[312] Beginning in 2008, the DEA began with Project Cassandra to work against reported Hezbollah activities in regards to Latin American drug trafficking.[313] The investigation by the DEA reported that Hezbollah made about a billion dollars a year and trafficked thousands of tons of cocaine into the United States.[314] Another destination for cocaine trafficking done by Hezbollah are nations within the Gulf Cooperation Council.[315] In 2013, Hezbollah was accused of infiltrating South America and having ties with Latin American drug cartels.[316]

One area of operations is in the region of the Triple Frontier, where Hezbollah has been alleged to be involved in the trafficking of cocaine; officials with the Lebanese embassy in Paraguay have worked to counter American allegations and extradition attempts.[317] In 2016, it was alleged that money gained from drug sales was used to purchase weapons in Syria.[318] In 2018, Infobae reported that Hezbollah was operating in Colombia under the name Organization of External Security.[319] That same year, Argentine police arrested individuals alleged to be connected to Hezbollah's criminal activities within the nation.[320]

The Los Angeles Times noted in 2020 that at the time, Hezbollah served as a "bogeyman of sorts" and that "[p]undits and politicians in the U.S., particularly those on the far right, have long issued periodic warnings that Hezbollah and other Islamic groups pose a serious threat in Latin America."[310] Various allegations have been made that Cuba,[321] Nicaragua[322] and Venezuela[323][324][325][326] aid Hezbollah in its operations in the region.[327] Israeli reports about the presence of Hezbollah in Latin America raised questions amongst Latin American analysts based in the United States[322] while experts say that reports of presence in Latin America are exaggerated.[310]

Southern Pulse director and analyst Samuel Logan said "Geopolitical proximity to Tehran doesn't directly translate into leniency of Hezbollah activity inside your country" in an interview with the Pulitzer Center.[322] William Neuman in his 2022 book Things Are Never So Bad That They Can't Get Worse said that claims of Hezbollah's presence in Latin America was "in reality, minimal", writing that the Venezuelan opposition raised such allegations to persuade the United States into believing that the nation faced a threat from Venezuela in an effort to promote foreign intervention.[328]

United States operations

Ali Kourani, the first Hezbollah operative to be convicted and sentenced in the United States, was under investigation since 2013 and worked to provide targeting and terrorist recruiting information to Hezbollah's Islamic Jihad Organization.[329] The organization had recruited a former resident of Minnesota and a military linguist, Mariam Tala Thompson, who disclosed "identities of at least eight clandestine human assets; at least 10 U.S. targets; and multiple tactics, techniques and procedures" before she was discovered and successfully prosecuted in a U.S. court.[330]

Other

In 2010, Ahbash and Hezbollah members were involved in a street battle which was perceived to be over parking issues, both groups later met to form a joint compensation fund for the victims of the conflict.[331]

According to Reuters, in 2024, commanders from Hezbollah and Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps were reported to be actively involved on the ground in Yemen, overseeing and directing Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping.[332]

Finances/economy

During the September 2021 fuel shortage, Hezbollah received a convoy of 80 tankers carrying oil/diesel fuel from Iran.[333][334]

Attacks on Hezbollah leaders

Hezbollah has also been the target of bomb attacks and kidnappings. These include:

- In the 1985 Beirut car bombing, Hezbollah leader Mohammad Hussein Fadlallah was targeted, but the assassination attempt failed.

- On 28 July 1989, Israeli commandos kidnapped Sheikh Abdel Karim Obeid, the leader of Hezbollah.[335] This action led to the adoption of UN Security Council resolution 638, which condemned all hostage takings by all sides.

- On 16 February 1992, Israeli helicopters attacked a motorcade in southern Lebanon, killing the Hezbollah leader Abbas al-Musawi, his wife, son, and four others.[103]

- On 31 March 1995, Rida Yasin, also known as Abu Ali, was killed by a single rocket fired from an Israeli helicopter while in a car near Derdghaya in the Israeli security zone 10 km east of Tyre. Yasin was a senior military commander in southern Lebanon. His companion in the car was also killed. An Israeli civilian was killed and fifteen wounded in the retaliatory rocket fire.[336][337]

- On 12 February 2008, Imad Mughnieh was killed by a car bomb in Damascus, Syria.[338]

- On 3 December 2013, senior military commander Hassan al-Laqis was shot outside his home, two miles (three kilometers) southwest of Beirut. He died a few hours later on 4 December.[339]

- On 18 January 2015, a group of Hezbollah fighters was targeted in Quneitra, with the Al-Nusra Front claiming responsibility. In this attack, for which Israel was also accused, Jihad Moghnieh, son of Imad Mughnieh, five other members of Hezbollah and an Iranian general of Quds Force, Mohammad Ali Allahdadi, were killed.[340][341][342]

- On 10 May 2016, an explosion near Damascus International Airport killed top military commander Mustafa Badreddine. Lebanese media sources attributed the attack to an Israeli airstrike. Hezbollah attributed the attack to Syrian opposition.[343][344][345]

Targeting policy

After the September 11, 2001 attacks, Hezbollah condemned al-Qaeda for targeting civilians in the World Trade Center,[346][347] but remained silent on the attack on The Pentagon.[50][348] Hezbollah also denounced the massacres in Algeria by Armed Islamic Group, Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya attacks on tourists in Egypt,[349] the murder of Nick Berg,[350] and ISIL attacks in Paris.[351]

Although Hezbollah has denounced certain attacks on civilians, some people accuse the organization of the bombing of an Argentine synagogue in 1994. Argentine prosecutor Alberto Nisman, Marcelo Martinez Burgos, and their "staff of some 45 people"[352] said that Hezbollah and their contacts in Iran were responsible for the 1994 bombing of a Jewish cultural center in Argentina, in which "[e]ighty-five people were killed and more than 200 others injured."[353]

In August 2012, the United States State Department's counter-terrorism coordinator Daniel Benjamin said that Hezbollah "is not constrained by concerns about collateral damage or political fallout that could result from conducting operations there [in Europe]".[354][355][356]

Foreign relations

Hezbollah has close relations with Iran.[357] It also has ties with the leadership in Syria, specifically President Hafez al-Assad, until his death in 2000, supported it.[358] It is also a close Assad ally, and its leader pledged support to the embattled Syrian leader.[359][360] Although Hezbollah and Hamas are not organizationally linked, Hezbollah provides military training as well as financial and moral support to the Sunni Palestinian group.[361] Furthermore, Hezbollah was a strong supporter of the second Intifada.[50]

American and Israeli counter-terrorism officials claim that Hezbollah has (or had) links to Al Qaeda, although Hezbollah's leaders deny these allegations.[362][363] Also, some al-Qaeda leaders, like Abu Musab al-Zarqawi[364] and Wahhabi clerics, consider Hezbollah to be apostate.[365] But United States intelligence officials speculate that there has been contact between Hezbollah and low-level al-Qaeda figures who fled Afghanistan for Lebanon.[366] However, Michel Samaha, Lebanon's former minister of information, has said that Hezbollah has been an important ally of the government in the war against terrorist groups, and described the "American attempt to link Hezbollah to al-Qaeda" to be "astonishing".[50]

Public opinion

According to Michel Samaha, Lebanon's minister of information, Hezbollah is seen as "a legitimate resistance organization that has defended its land against an Israeli occupying force and has consistently stood up to the Israeli army".[50]

According to a survey released by the "Beirut Center for Research and Information" on 26 July during the 2006 Lebanon War, 87 percent of Lebanese support Hezbollah's "retaliatory attacks on northern Israel",[367] a rise of 29 percentage points from a similar poll conducted in February. More striking, however, was the level of support for Hezbollah's resistance from non-Shiite communities. Eighty percent of Christians polled supported Hezbollah, along with 80 percent of Druze and 89 percent of Sunnis.[368]

In a poll of Lebanese adults taken in 2004, 6% of respondents gave unqualified support to the statement "Hezbollah should be disarmed". 41% reported unqualified disagreement. A poll of Gaza Strip and West Bank residents indicated that 79.6% had "a very good view" of Hezbollah, and most of the remainder had a "good view". Polls of Jordanian adults in December 2005 and June 2006 showed that 63.9% and 63.3%, respectively, considered Hezbollah to be a legitimate resistance organization. In the December 2005 poll, only 6% of Jordanian adults considered Hezbollah to be terrorist.[369]

A July 2006 USA Today/Gallup poll found that 83% of the 1,005 Americans polled blamed Hezbollah, at least in part, for the 2006 Lebanon War, compared to 66% who blamed Israel to some degree. Additionally, 76% disapproved of the military action Hezbollah took in Israel, compared to 38% who disapproved of Israel's military action in Lebanon.[370] A poll in August 2006 by ABC News and The Washington Post found that 68% of the 1,002 Americans polled blamed Hezbollah, at least in part, for the civilian casualties in Lebanon during the 2006 Lebanon War, compared to 31% who blamed Israel to some degree.[370] Another August 2006 poll by CNN showed that 69% of the 1,047 Americans polled believed that Hezbollah is unfriendly towards, or an enemy of, the United States.[370]

In 2010, a survey of Muslims in Lebanon showed that 94% of Lebanese Shia supported Hezbollah, while 84% of the Sunni Muslims held an unfavorable opinion of the group.[371]

Some public opinion has started to turn against Hezbollah for their support of Syrian President Assad's attacks on the opposition movement in Syria.[372] Crowds in Cairo shouted out against Iran and Hezbollah, at a public speech by Hamas President Ismail Haniya in February 2012, when Hamas changed its support to the Syrian opposition.[373]

View of Hezbollah

A November 2020 poll in Lebanon performed by the pro-Israel, American Washington Institute for Near East Policy declared that support for Hezbollah is declining significantly. Below is a table of the results of their polls.[374]

| Religion | Very positive view (%) | Somewhat positive view (%) | Somewhat negative view (%) | Very negative view (%) | Unsure (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian | 6% | 10% | 23% | 59% | 2% |

| Shia | 66% | 23% | 10% | 2% | 0% |

| Sunni | 2% | 6% | 32% | 60% | 0% |

Designation as a terrorist organization or resistance movement

Hezbollah's status as a legitimate political party, a terrorist group, a resistance movement, or some combination thereof is a contentious issue.[375]

As of October 2020, Hezbollah or its military wing are considered terrorist organizations by at least 26 countries, as well as by the European Union and since 2017 by most member states of the Arab League, with the exception of Iraq and Lebanon, where Hezbollah is the most powerful political party.[86]

The countries that have designated Hezbollah a terrorist organisation include: the Arab League[376] and the Gulf Cooperation Council,[377] and their members Saudi Arabia,[378] Bahrain,[379] United Arab Emirates,[378] as well as Argentina,[380] Canada,[381] Colombia,[382] Estonia,[383] Germany,[384] Honduras,[385] Israel,[386] Kosovo,[387] Lithuania,[388] Malaysia,[389] Paraguay,[390] Serbia,[383] Slovenia,[391] United Kingdom,[392] United States,[393] and Guatemala.[394]

The EU differentiates between the Hezbollah's political wing and military wing, banning only the latter, though Hezbollah itself does not recognize such a distinction.[383] Hezbollah maintains that it is a legitimate resistance movement fighting for the liberation of Lebanese territory.

There is a "wide difference" between American and Arab perception of Hezbollah.[50] Several Western countries officially classify Hezbollah or its external security wing as a terrorist organization, and some of their violent acts have been described as terrorist attacks. However, throughout most of the Arab and Muslim worlds, Hezbollah is referred to as a resistance movement, engaged in national defense.[125][395][396]

Even within Lebanon, sometimes Hezbollah's status as either a "militia" or "national resistance" has been contentious. In Lebanon, although not universally well-liked, Hezbollah is widely seen as a legitimate national resistance organization defending Lebanon, and actually described by the Lebanese information minister as an important ally in fighting terrorist groups.[50][397] In the Arab world, Hezbollah is generally seen either as a destabilizing force that functions as Iran's pawn by rentier[clarification needed] states like Egypt and Saudi Arabia, or as a popular sociopolitical guerrilla movement that exemplifies strong leadership, meaningful political action, and a commitment to social justice.

The United Nations Security Council has never listed Hezbollah as a terrorist organization under its sanctions list, although some of its members have done so individually. The United Kingdom listed Hezbollah's military wing as a terrorist organization[398] until May 2019 when the entire organisation was proscribed,[399] and the United States[400] lists the entire group as such. Russia has considered Hezbollah a legitimate sociopolitical organization,[401] and the People's Republic of China remains neutral and maintains contacts with Hezbollah.[citation needed][402]

In May 2013, France and Germany released statements that they will join other European countries in calling for an EU-blacklisting of Hezbollah as a terror group.[403] In April 2020 Germany designated the organization—including its political wing—as a terrorist organization, and banned any activity in support of Hezbollah.[404]

The following entities have listed Hezbollah as a terror group:

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [376] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [405][406] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [407][408][409] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [410] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [411] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [412] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [382][413] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [410] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [383] | |

| Hezbollah's military wing | [414][85] | |

| The military wing of Hezbollah only, France considers the political wing as a legitimate sociopolitical organization | [415] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [416][417] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [377] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [394] | |

| The entire organisation Hezbollah | [413][418][419] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [37] | |

| The military wing of Hezbollah | [420] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [421] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [422] | |

| Hezbollah's military wing Al-Muqawama al-Islamiyya, since 2010 | [423] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [424] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [425] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [391] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [378] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [399] | |

| The entire organization Hezbollah | [426] |

The following countries do not consider Hezbollah a terror organization:

| Algeria refused to designate Hezbollah as a terrorist organization | [427] | |

| The People's Republic of China remains neutral and maintains contacts with Hezbollah | [402] | |

| Hezbollah allegedly operates a base in Cuba | [428] | |

| [429] | ||