Рухолла Хомейни

Рухолла Хомейни | |

|---|---|

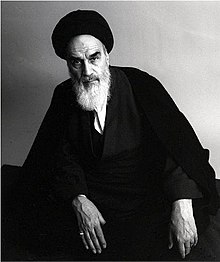

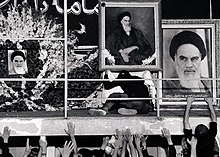

| Рухолла Хомейни | |

Official portrait, 1981 | |

| 1st Supreme Leader of Iran | |

| In office 3 December 1979 – 3 June 1989 | |

| President |

|

| Prime Minister | |

| Deputy | Hussein-Ali Montazeri (1985–1989) |

| Preceded by | Position established (Mohammad Reza Pahlavi as Shah of Iran) |

| Succeeded by | Ali Khamenei |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ruhollah Mostafavi Musavi 17 May 1900 or 24 September 1902[a] Khomeyn, Sublime State of Persia |

| Died | 3 June 1989 (aged 86 or 89) Tehran, Iran |

| Resting place | Mausoleum of Ruhollah Khomeini |

| Spouse | |

| Relations | Khomeini family |

| Children | 7, including Mostafa, Zahra, Farideh, and Ahmad |

| Education | Qom Seminary |

| Signature |  |

| Website | imam-khomeini |

| Personal | |

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Twelver Shiʿa[1][2][3] |

| Creed | Usuli |

| Notable idea(s) | New advance of Guardianship |

| Notable work(s) | |

| Muslim leader | |

| Teacher | Seyyed Hossein Borujerdi |

| Styles of Ruhollah Khomeini | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | Eminent marji' al-taqlid, Ayatullah al-Uzma Imam Khumayni[4] |

| Spoken style | Imam Khomeini[5] |

| Religious style | Ayatullah al-Uzma Ruhollah Khomeini[5] |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Republicanism |

|---|

Аятолла Рухолла Мусави Хомейни [б] (17 мая 1900 г. или 24 сентября 1902 г. [а] — 3 июня 1989) — иранский исламский революционер, политик и религиозный лидер, занимавший пост первого верховного лидера Ирана с 1979 года до своей смерти в 1989 году . Он был основателем Исламской Республики Иран и главным лидером иранской революции , которая свергла Мохаммада Резу Пехлеви и положила конец иранской монархии .

Его отец родился в Хомейне , на территории нынешней иранской провинции Маркази , и был убит в 1903 году, когда Хомейни было два года. Он начал изучать Коран и арабский язык с юных лет, и в изучении религии ему помогали родственники, в том числе двоюродный брат и старший брат его матери. Хомейни был высокопоставленным священнослужителем двунадесятного шиизма , аятоллой , марджой («источником подражания»), муджтахидом или факихом (знатоком шариата ) и автором более 40 книг. Его сопротивление Белой революции привело к его в 1964 году , спонсируемой государством высылке в Бурсу . Почти год спустя он переехал в Наджаф , где речи, которые он произнес, излагая свою религиозно-политическую теорию «Опека над юристами», были объединены в исламское правительство .

He was Time magazine's Man of the Year in 1979 for his international influence, and Khomeini has been described as the "virtual face of Shia Islam in Western popular culture", where he was known for his support of the hostage takers during the Iran hostage crisis, his fatwa calling for the murder of British Indian novelist Salman Rushdie, and for referring to the United States as the "Great Satan" and the Soviet Union as the "Lesser Satan". Following the revolution, Khomeini became the country's first supreme leader, a position created in the constitution of the Islamic Republic as the highest-ranking political and religious authority of the nation, which he held until his death. Most of his period in power was taken up by the Iran–Iraq War of 1980–1988. He was succeeded by Ali Khamenei on 4 June 1989.

The subject of a pervasive cult of personality, Khomeini is officially known as Imam Khomeini inside Iran and by his supporters internationally. His funeral was attended by up to 10 million people, or 1/6 of Iran's population, the largest funeral at the time and one of the largest human gatherings in history. In Iran, his gold-domed tomb in Tehran's Behesht-e Zahrāʾ cemetery has become a shrine for his adherents, and he is legally considered "inviolable", with Iranians regularly punished for insulting him. His supporters view him as a champion of Islamic revival, anti-racism and anti-imperialism. Critics accuse him of human rights violations (including his ordering of attacks against demonstrators, and execution of thousands of political prisoners, war criminals and prisoners of the Iran–Iraq War), as well as for using child soldiers extensively during the Iran–Iraq War for human wave attacks—estimates are as high as 100,000 for the number of children killed.

Early years

Background

Ruhollah Khomeini came from a lineage of small land owners, clerics, and merchants.[6] His ancestors migrated towards the end of the 18th century from their original home in Nishapur, Khorasan province in northeastern Iran for a short stay to the Kingdom of Awadh, a region in the modern state of Uttar Pradesh, India, whose rulers were Twelver Shia Muslims of Persian origin.[7][8][9] During their rule they extensively invited, and received, a steady stream of Persian scholars, poets, jurists, architects, and painters.[10] The family eventually settled in the small town of Kintoor, near Lucknow, the capital of Awadh.[11][12][13][14] Ayatollah Khomeini's paternal grandfather, Seyyed Ahmad Musavi Hindi, was born in Kintoor.[12][14] He left Lucknow in 1830, on a pilgrimage to the tomb of Ali in Najaf, Ottoman Iraq (now Iraq) and never returned.[11][14] According to Moin, this migration was to escape from the spread of British power in India.[15] In 1834 Seyyed Ahmad Musavi Hindi visited Persia, and in 1839 he settled in Khomein.[12] Although he stayed and settled in Iran, he continued to be known as Hindi, indicating his stay in India, and Ruhollah Khomeini even used Hindi as a pen name in some of his ghazals.[11] Khomeini's grandfather, Mirza Ahmad Mojtahed-e Khonsari was the cleric issuing a fatwa to forbid usage of tobacco during the Tobacco Protest.[16][17]

Childhood

According to his birth certificate, Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini, whose first name means "spirit of Allah", was born on 17 May 1900 in Khomeyn, Markazi Province although his brother Mortaza (later known as Ayatollah Pasandideh) gives his birth date of 24 September 1902, the birth anniversary of Muhammad's daughter, Fatima.[18][19] He was raised by his mother, Agha Khanum, and his aunt, Sahebeth, following the murder of his father, Mustafa Musawi, over two years after his birth in 1903.[20]

Ruhollah began to study the Qur'an and elementary Persian at the age of six.[21] The following year, he began to attend a local school, where he learned religion, noheh khani (lamentation recital), and other traditional subjects.[15] Throughout his childhood, he continued his religious education with the assistance of his relatives, including his mother's cousin, Ja'far,[15] and his elder brother, Morteza Pasandideh.[22]

Education and lecturing

After the First World War, arrangements were made for him to study at the Islamic seminary in Isfahan, but he was attracted instead to the seminary in Arak. He was placed under the leadership of Ayatollah Abdolkarim Haeri Yazdi.[23] In 1920, Khomeini moved to Arak and commenced his studies.[24] The following year, Ayatollah Haeri Yazdi transferred to the Islamic seminary in the holy city of Qom, southwest of Tehran, and invited his students to follow. Khomeini accepted the invitation, moved,[22] and took up residence at the Dar al-Shafa school in Qom.[25] Khomeini's studies included Islamic law (sharia) and jurisprudence (fiqh),[21] but by that time, Khomeini had also acquired an interest in poetry and philosophy (irfan). So, upon arriving in Qom, Khomeini sought the guidance of Mirza Ali Akbar Yazdi, a scholar of philosophy and mysticism. Yazdi died in 1924, but Khomeini continued to pursue his interest in philosophy with two other teachers, Javad Aqa Maleki Tabrizi and Rafi'i Qazvini.[26][27] However, perhaps Khomeini's biggest influences were another teacher, Mirza Muhammad 'Ali Shahabadi,[28] and a variety of historic Sufi mystics, including Mulla Sadra and Ibn Arabi.[27]

Khomeini studied ancient Greek philosophy and was influenced by both the philosophy of Aristotle, whom he regarded as the founder of logic,[29] and Plato, whose views "in the field of divinity" he regarded as "grave and solid".[30] Among Islamic philosophers, Khomeini was mainly influenced by Avicenna and Mulla Sadra.[29]

Apart from philosophy, Khomeini was interested in literature and poetry. His poetry collection was released after his death. Beginning in his adolescent years, Khomeini composed mystic, political and social poetry. His poetry works were published in three collections: The Confidant, The Decanter of Love and Turning Point, and Divan.[31] His knowledge of poetry is further attested by the modern poet Nader Naderpour (1929–2000), who "had spent many hours exchanging poems with Khomeini in the early 1960s". Naderpour remembered: "For four hours we recited poetry. Every single line I recited from any poet, he recited the next."[32]

Ruhollah Khomeini was a lecturer at Najaf and Qom seminaries for decades before he was known on the political scene. He soon became a leading scholar of Shia Islam.[33] He taught political philosophy,[34] Islamic history and ethics. Several of his students – for example, Morteza Motahhari – later became leading Islamic philosophers and also marja'. As a scholar and teacher, Khomeini produced numerous writings on Islamic philosophy, law, and ethics.[35] He showed an exceptional interest in subjects like philosophy and mysticism that not only were usually absent from the curriculum of seminaries but were often an object of hostility and suspicion.[36]

Inaugurating his teaching career at the age of 27 by giving private lessons on irfan and Mulla Sadra to a private circle, around the same time, in 1928, he also released his first publication, Sharh Du'a al-Sahar (Commentary on the Du'a al-Baha), "a detailed commentary, in Arabic, on the prayer recited before dawn during Ramadan by Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq", followed, some years later, by Sirr al-Salat (Secret of the Prayer), where "the symbolic dimensions and inner meaning of every part of the prayer, from the ablution that precedes it to the salam that concludes it, are expounded in a rich, complex, and eloquent language that owes much to the concepts and terminology of Ibn 'Arabi. As Sayyid Fihri, the editor and translator of Sirr al-Salat, has remarked, the work is addressed only to the foremost among the spiritual elite (akhass-i khavass) and establishes its author as one of their number."[37] The second book has been translated by Sayyid Amjad Hussain Shah Naqavi and released by Brill in 2015, under the title "The Mystery of Prayer: The Ascension of the Wayfarers and the Prayer of the Gnostics Archived 6 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine".

Political aspects

His seminary teaching often focused on the importance of religion to practical social and political issues of the day, and he worked against secularism in the 1940s. His first political book, Kashf al-Asrar (Uncovering of Secrets)[38][39] published in 1942, was a point-by-point refutation of Asrar-e Hezar Sale (Secrets of a Thousand Years), a tract written by a disciple of Iran's leading anti-clerical historian, Ahmad Kasravi,[40] as well as a condemnation of innovations such as international time zones,[c][non-primary source needed] and the banning of hijab by Reza Shah. In addition, he went from Qom to Tehran to listen to Ayatullah Hasan Mudarris, the leader of the opposition majority in Iran's parliament during the 1920s. Khomeini became a marja' in 1963, following the death of Grand Ayatollah Seyyed Husayn Borujerdi.

Khomeini also valued the ideals of Islamists such as Sheikh Fazlollah Noori and Abol-Ghasem Kashani. Khomeini saw Fazlollah Nuri as a "heroic figure", and his own objections to constitutionalism and a secular government derived from Nuri's objections to the 1907 constitution.[41][42][43]

Early political activity

Background

In the late 19th century, the clergy had shown themselves to be a powerful political force in Iran initiating the Tobacco Protest against a concession to a foreign (British) interest.[44]

At the age of 61, Khomeini found the arena of leadership open following the deaths of Ayatollah Sayyed Husayn Borujerdi (1961), the leading, although quiescent, Shi'ah religious leader; and Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kashani (1962), an activist cleric. The clerical class had been on the defensive ever since the 1920s when the secular, anti-clerical modernizer Reza Shah Pahlavi rose to power. Reza's son Mohammad Reza Shah instituted the White Revolution, which was a further challenge to the Ulama.[45]

Opposition to the White Revolution

In January 1963, the Shah announced the White Revolution, a six-point programme of reform calling for land reform, nationalization of the forests, the sale of state-owned enterprises to private interests, electoral changes to enfranchise women and allow non-Muslims to hold office, profit-sharing in industry, and a literacy campaign in the nation's schools. Some of these initiatives were regarded as dangerous, especially by the powerful and privileged Shi'a ulama (religious scholars), and as Westernizing trends by traditionalists. Khomeini viewed them as "an attack on Islam".[46] Ayatollah Khomeini summoned a meeting of the other senior marjas of Qom and persuaded them to decree a boycott of the referendum on the White Revolution. On 22 January 1963, Khomeini issued a strongly worded declaration denouncing both the Shah and his reform plan. Two days later, the Shah took an armored column to Qom, and delivered a speech harshly attacking the ulama as a class.

Khomeini continued his denunciation of the Shah's programmes, issuing a manifesto that bore the signatures of eight other senior Shia religious scholars. Khomeini's manifesto argued that the Shah had violated the constitution in various ways, he condemned the spread of moral corruption in the country, and accused the Shah of submission to the United States and Israel. He also decreed that the Nowruz celebrations for the Iranian year 1342 (which fell on 21 March 1963) be canceled as a sign of protest against government policies.

On the afternoon of 'Ashura (3 June 1963), Khomeini delivered a speech at the Feyziyeh madrasah drawing parallels between the Caliph Yazid, who is perceived as a 'tyrant' by Shias, and the Shah, denouncing the Shah as a "wretched, miserable man," and warning him that if he did not change his ways the day would come when the people would offer up thanks for his departure from the country.

On 5 June 1963 (15 of Khordad) at 3:00 am, two days after this public denunciation of the Shah, Khomeini was detained in Qom and transferred to Tehran.[47] Following this action, there were three days of major riots throughout Iran and the deaths of some 400 people. That event is now referred to as the Movement of 15 Khordad.[48] Khomeini remained under house arrest until August.[49][50]

Opposition to capitulation

On 26 October 1964, Khomeini denounced both the Shah and the United States. This time it was in response to the "capitulations" or diplomatic immunity granted by the Shah to American military personnel in Iran.[51][52] What Khomeini labeled a capitulation law, was in fact a "status-of-forces agreement", stipulating that U.S. servicemen facing criminal charges stemming from a deployment in Iran, were to be tried before a U.S. court martial, not an Iranian court. Khomeini was arrested in November 1964 and held for half a year. Upon his release, Khomeini was brought before Prime Minister Hassan Ali Mansur, who tried to convince him to apologize for his harsh rhetoric and going forward, cease his opposition to the Shah and his government. When Khomeini refused, Mansur slapped him in the face in a fit of rage. Two months later, Mansur was assassinated on his way to parliament. Four members of the Fadayan-e Islam, a Shia militia sympathetic to Khomeini, were later executed for the murder.[53]

Life in exile

Khomeini spent more than 14 years in exile, mostly in the holy Iraqi city of Najaf. Initially, he was sent to Turkey on 4 November 1964 where he stayed in Bursa in the home of Colonel Ali Cetiner of the Turkish Military Intelligence.[54] In October 1965, after less than a year, he was allowed to move to Najaf, Iraq, where he stayed until 1978, when he was expelled[55] by then-Vice President Saddam Hussein. By this time discontent with the Shah was becoming intense and Khomeini visited Neauphle-le-Château, a suburb of Paris, France, on a tourist visa on 6 October 1978.[35][56][57]

By the late 1960s, Khomeini was a marja-e taqlid (model for imitation) for "hundreds of thousands" of Shia, one of six or so models in the Shia world.[58] While in the 1940s Khomeini accepted the idea of a limited monarchy under the Persian Constitution of 1906 – as evidenced by his book Kashf al-Asrar – by the 1970s he had rejected the idea. In early 1970, Khomeini gave a series of lectures in Najaf on Islamic government, later published as a book titled variously Islamic Government or Islamic Government: Governance of the Jurist (Hokumat-e Islami: Velayat-e faqih). This principle, though not known to the wider public before the revolution,[59][60] was appended to the new Iranian constitution after the revolution.[61][62]

- Velayat-e faqih

This was his best known and most influential work, and laid out his ideas on governance (at that time):

- That the laws of society should be made up only of the laws of God (Sharia), which are sufficient because they cover "all human affairs" and "provide instruction and establish norms" for every "topic" in "human life."[63]

- Since Shariah, or Islamic law, is the proper law, those holding government posts should have knowledge of Sharia. Since Islamic jurists or faqih have studied and are the most knowledgeable in Sharia, the country's ruler should be a faqih who "surpasses all others in knowledge" of Islamic law and justice,[64] (known as a marja'), as well as having intelligence and administrative ability. Rule by monarchs and/or assemblies of "those claiming to be representatives of the majority of the people" (i.e. elected parliaments and legislatures) has been proclaimed "wrong" by Islam.[65]

- This system of clerical rule is necessary to prevent injustice, corruption, oppression by the powerful over the poor and weak, innovation and deviation of Islam and Sharia law; and also to destroy anti-Islamic influence and conspiracies by non-Muslim foreign powers.[66]

Pre-revolutionary political activity

A modified form of this wilayat al-faqih system was adopted after Khomeini and his followers took power, and Khomeini was the Islamic Republic's first "Guardian" or "Supreme Leader". In the meantime, however, Khomeini talked only about "Islamic Government", never spelling out what exactly that meant.[67] His network may have been learning about the necessity of rule by Jurists, but "in his interview, speeches, messages and fatvas during this period, there is not a single reference to velayat-e faqih."[67] Khomenei was careful not to publicize his ideas for clerical rule outside of his Islamic network of opposition to the Shah and so not frighten away the secular middle class from his movement.[68] His movement emphasized populism, talking about fighting for the mustazafin, a Quranic term for the oppressed or deprived, that in this context came to mean "just about everyone in Iran except the shah and the imperial court".[68]

In Iran, a number of missteps by the Shah including his repression of opponents began to build opposition to his regime.

Cassette copies of his lectures fiercely denouncing the Shah as (for example) "the Jewish agent, the American serpent whose head must be smashed with a stone",[69] became common items in the markets of Iran,[70] helping to demythologize the power and dignity of the Shah and his reign. As Iran became more polarized and opposition more radical, Khomeini "was able to mobilize the entire network of mosques in Iran", along with their pious faithful, regular gatherings, hitherto skeptical Mullah leaders, and supported by "over 20,000 properties and buildings throughout Iran"—a political resource the secular middle class and Shiite socialists could not hope to compete with.[68] Aware of the importance of broadening his base, Khomeini reached out to Islamic reformist and secular enemies of the Shah, groups that were suppressed after he took and consolidated power.

After the 1977 death of Ali Shariati (an Islamic reformist and political revolutionary author/academic/philosopher who greatly assisted the Islamic revival among young educated Iranians), Khomeini became the most influential leader of the opposition to the Shah. Adding to his mystique was the circulation among Iranians in the 1970s of an old Shia saying attributed to the Imam Musa al-Kadhem. Prior to his death in 799, al-Kadhem was said to have prophesied that "A man will come out from Qom and he will summon people to the right path".[71] In late 1978, a rumour swept the country that Khomeini's face could be seen in the full moon. Millions of people were said to have seen it and the event was celebrated in thousands of mosques.[72][73] The phenomenon was thought to demonstrate that by late 1978 he was increasingly regarded as a messianic figure in Iran, and perceived by many as the spiritual as well as political leader of the revolt.[74]

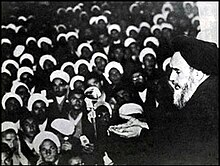

As protests grew, so did his profile and importance. Although several thousand kilometers away from Iran in Paris, Khomeini set the course of the revolution, urging Iranians not to compromise and ordering work stoppages against the regime.[75] During the last few months of his exile, Khomeini received a constant stream of reporters, supporters, and notables, eager to hear the spiritual leader of the revolution.[76]

While in exile, Khomeini developed what historian Ervand Abrahamian described as a "populist clerical version of Shii Islam". Khomeini modified previous Shii interpretations of Islam in a number of ways that included aggressive approaches to espousing the general interests of the mostazafin, forcefully arguing that the clergy's sacred duty was to take over the state so that it could implement shari'a, and exhorting followers to protest.[77]

Despite their ideological differences, Khomeini also allied with the People's Mujahedin of Iran during the early 1970s and started funding their armed operations against the Shah.[78]

Khomeini's contact with the US

According to the BBC, Khomeini's contact with the US "is part of a trove of newly declassified US government documents—diplomatic cables, policy memos, meeting records". The documents suggest that the Carter administration helped Khomeini return to Iran by preventing the Iranian army from launching a military coup, and that Khomeini told an American in France to convey a message to Washington that "There should be no fear about oil. It is not true that we wouldn't sell to the US."[79] The Guardian wrote that it "did not have access to the newly declassified documents and was not able to independently verify them," however it did confirm Khomeini's contact with the Kennedy administration and claims of support for US interest in Iran particularly oil through a CIA analysis report titled "Islam in Iran".[80]

According to a 1980 CIA study, "in November 1963 Ayatollah Khomeini sent a message to the United States Government through [Tehran University professor] Haj Mirza Khalil Kamarei", where he expressed "that he was not opposed to American interests in Iran", "on the contrary, he thought the American presence was necessary as a counterbalance to Soviet and possibly British influence".

According to the BBC, "these document show that in his long quest for power, he [Khomeini] was tactically flexible; he played the moderate even pro-American card to take control but once change had come he put in place an anti-America legacy that would last for decades."[81]

Supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei denied the report, and described the documents as "fabricated". Other Iranian politicians including Ebrahim Yazdi (Khomeini's spokesman and adviser at the time of the revolution) have denounced the documents and the BBC's report.[80]

Supreme Leader of Iran

Return to Iran

On 16 January 1979, the Shah left the country for medical treatment (ostensibly "on vacation"), never to return.[82] Two weeks later, on Thursday, 1 February 1979, Khomeini returned in triumph to Iran, welcomed by a joyous crowd reported to be of up to five million people.[82] On his chartered Air France flight back to Tehran, he was accompanied by 120 journalists,[83][84] including three women.[84] One of the journalists, Peter Jennings, asked: "Ayatollah, would you be so kind as to tell us how you feel about being back in Iran?"[85] Khomeini answered via his aide Sadegh Ghotbzadeh: "Hichi" (Nothing).[85] This statement—much discussed at the time[86] and since[87]—was considered by some reflective of his mystical beliefs and non-attachment to ego.[88] Others considered it a warning to Iranians who hoped he would be a "mainstream nationalist leader" that they were in for disappointment.[89] To others, it was a reflection of Khomeini's disinterest in the desires, beliefs, or the needs of the Iranian populace.[87] He was Time magazine's Man of the Year in 1979 for his international influence.[90]

Revolution

Khomeini adamantly opposed the provisional government of Shapour Bakhtiar, promising "I shall kick their teeth in. I appoint the government."[91][92] On 11 February (Bahman 22), Khomeini appointed his own competing interim prime minister, Mehdi Bazargan, demanding, "since I have appointed him, he must be obeyed." It was "God's government," he warned, disobedience against him or Bazargan was considered a "revolt against God,"[93] and "revolt against God is Blasphemy".[94]

As Khomeini's movement gained momentum, soldiers began to defect to his side and Khomeini declared ill fortune on troops who did not surrender.[95] On 11 February, as revolt spread and armories were taken over, the military declared neutrality and the Bakhtiar regime collapsed.[96] On 30 and 31 March 1979, a referendum to replace the monarchy with an Islamic Republic—with the question: "should the monarchy be abolished in favour of an Islamic Government?"—passed with 98% voting in favour of the replacement.[97]

Beginning of the consolidation of power

While in Paris, Khomeini had "promised a democratic political system" for Iran, but once in power, he advocated for the creation of theocracy[98] based on the Velayat-e faqih. Thus began the process of suppression of groups inside his broad coalition but outside his network, that had placed their hopes in Khomeini but whose support was no longer needed.[99] This led to the purge or replacement of many secular politicians in Iran, with Khomeini and his close associates taking the following steps: Establishing Islamic Revolutionary courts; replacing the previous military and police force; placing Iran's top theologians and Islamic intellectuals in charge of writing a theocratic constitutions, with a central role for Velayat-e faqih; creating the Islamic Republic Party (IRP) through Khomeini's Motjaheds with the aim of establishing a theocratic government and tearing down any secular opposition; replacing all secular laws with Islamic laws; neutralising or punishing top theologians ("Khomeini's competitors in the religious hierarchy"), whose ideas conflicted with Khomeini's, including Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari, Hassan Tabatabaei Qomi, and Hossein Ali Montazeri.[100] Some newspapers were closed, and those protesting the closings were attacked.[101] Opposition groups such as the National Democratic Front and Muslim People's Republican Party were attacked and finally banned.[102]

Islamic constitution

As part of the pivot from guide of a broad political movement to strict clerical ruler, Khomeini's first expressed approval of the provisional constitution for the Islamic Republic that had no post of supreme Islamic clerical ruler.[103] But after his supporters gained an overwhelming majority of the seats in the body making final changes in the draft (the Assembly of Experts),[104] they rewrote the proposed constitution to include an Islamic jurist Supreme Leader of the country, and a more powerful Council of Guardians to veto un-Islamic legislation and screen candidates for office, disqualifying those found un-Islamic.

The Supreme Leader followed closely but not completely Khomeini ideas in his 1970 book Hokumat-e Islami: Velayat-e faqih (Islamic Government: Governance of the Jurist) (mentioned above), that had been distributed to his supporters and kept from the public.

Becoming Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic

In November 1979, the new constitution of the Islamic Republic was adopted by national referendum.[105][106] Khomeini himself became instituted as the Supreme Leader, and officially became known as the "Leader of the Revolution." On 4 February 1980, Abolhassan Banisadr was elected as the first president of Iran. Critics complained that Khomeini had gone back on his word to advise, rather than rule the country.[107][108]

Hostage crisis

Before the constitution was approved, on 22 October 1979, the United States admitted the exiled and ailing Shah into the country for cancer treatment. In Iran, there was an immediate outcry, with both Khomeini and leftist groups demanding the Shah's return to Iran for trial and execution.

On 4 November, a group of Iranian college students calling themselves the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line took control of the American Embassy in Tehran, holding 52 embassy staff hostage for 444 days – an event known as the Iran hostage crisis.[109] In the United States, the hostage-taking was seen as a flagrant violation of international law and aroused intense anger and anti-Iranian sentiment.[110][111]

In Iran, the takeover was immensely popular and earned the support of Khomeini under the slogan "America can't do a damn thing against us."[112] The seizure of the embassy of a country he called the "Great Satan"[113] helped to advance the cause of theocratic government and outflank politicians and groups who emphasized stability and normalized relations with other countries. Khomeini is reported to have told his president: "This action has many benefits ... this has united our people. Our opponents do not dare act against us. We can put the constitution to the people's vote without difficulty, and carry out presidential and parliamentary elections."[114] The new constitution was successfully passed by referendum a month after the hostage crisis began.

The crisis had the effect of splitting of the opposition into two groups – radicals supporting the hostage taking, and the moderates opposing it.[114][115] On 23 February 1980, Khomeini proclaimed Iran's Majlis would decide the fate of the American embassy hostages, and demanded that the United States hand over the Shah for trial in Iran for crimes against the nation. Although the Shah died a few months later, during the summer, the crisis continued. In Iran, supporters of Khomeini named the embassy a "Den of Espionage", publicizing details regarding armaments, espionage equipment and many volumes of official and classified documents which they found there.

Relationship with Islamic and non-aligned countries

Khomeini believed in Muslim unity and solidarity and the export of his revolution throughout the world. He believed Shia and (the significantly more numerous) Sunni Muslims should be "united and stand firmly against Western and arrogant powers."[116] "Establishing the Islamic state world-wide belong to the great goals of the revolution."[117] He declared the birth week of Muhammad (the week between 12th to 17th of Rabi' al-awwal) as the Unity week. Then he declared the last Friday of Ramadan as Quds Day in 1981.[118]

Iran–Iraq War

Shortly after assuming power, Khomeini began calling for Islamic revolutions across the Muslim world, including Iran's Arab neighbor Iraq,[119] the one large state besides Iran with a Shia majority population. At the same time Saddam Hussein, Iraq's secular Arab nationalist Ba'athist leader, was eager to take advantage of Iran's weakened military and (what he assumed was) revolutionary chaos, and in particular to occupy Iran's adjacent oil-rich province of Khuzestan, and to undermine Iranian Islamic revolutionary attempts to incite the Shi'a majority of his country.

In September 1980, Iraq launched a full-scale invasion of Iran, beginning the Iran–Iraq War (September 1980 – August 1988). A combination of fierce resistance by Iranians and military incompetence by Iraqi forces soon stalled the Iraqi advance and, despite Saddam's internationally condemned use of poison gas, Iran had by early 1982 regained almost all of the territory lost to the invasion. The invasion rallied Iranians behind the new regime, enhancing Khomeini's stature and allowing him to consolidate and stabilize his leadership. After this reversal, Khomeini refused an Iraqi offer of a truce, instead demanding reparations and the toppling of Saddam Hussein from power.[120][121] In 1982, there was an attempted military coup against Khomeini.[122]

Although Iran's population and economy were three times the size of Iraq's, the latter was aided by neighboring Persian Gulf Arab states, as well as the Soviet Bloc and Western countries. The Persian Gulf Arabs and the West wanted to be sure the Islamic revolution did not spread across the Persian Gulf, while the Soviet Union was concerned about the potential threat posed to its rule in central Asia to the north. However, Iran had large amounts of ammunition provided by the United States of America during the Shah's era and the United States illegally smuggled arms to Iran during the 1980s despite Khomeini's anti-Western policy (see Iran–Contra affair).

During war Iranians used human wave attacks (people walking to certain death including child soldiers)[123][124] on Iraq, with his promise that they would automatically go to paradise—al Janna— if they died in battle,[124] and his pursuit of victory in the Iran–Iraq War that ultimately proved futile.[125][126] By March 1984, two million of Iran's most educated citizens had left the country.[127]

In July 1988, Khomeini, in his words, "drank the cup of poison" and accepted a truce mediated by the United Nations. Despite the high cost of the war – 450,000 to 950,000 Iranian casualties and US$300 billion[128] – Khomeini insisted that extending the war into Iraq in an attempt to overthrow Saddam had not been a mistake. In a "Letter to Clergy" he wrote: "... we do not repent, nor are we sorry for even a single moment for our performance during the war. Have we forgotten that we fought to fulfill our religious duty and that the result is a marginal issue?"[129]

Fatwa against chemical weapons

In an interview with Gareth Porter, Mohsen Rafighdoost, the eight-year war time minister of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, disclosed how Khomeini had opposed his proposal for beginning work on both nuclear and chemical weapons by a fatwa which had never been made public in details of when and how it was issued.[130]

Rushdie fatwa

I would like to inform all the intrepid Muslims in the world that the author of the book entitled The Satanic Verses, which has been compiled, printed and published in opposition to Islam, the Prophet and the Qur'an, as well as those publishers who were aware of its contents, have been declared madhur el dam [those whose blood must be shed]. I call on all zealous Muslims to execute them quickly, wherever they find them, so that no-one will dare to insult Islam again. Whoever is killed in this path will be regarded as a martyr.[131]

In early 1989, Khomeini issued a fatwa calling for the assassination of Salman Rushdie, an India-born British author.[90][132] Rushdie's book, The Satanic Verses, published in 1988, was alleged to commit blasphemy against Islam and Khomeini's juristic ruling (fatwā) prescribed Rushdie's assassination by any Muslim. The fatwā required not only Rushdie's execution, but also the execution of "all those involved in the publication" of the book.[133]

Khomeini's fatwā was condemned across the Western world by governments on the grounds that it violated the universal human rights of free speech and freedom of religion. The fatwā has also been attacked for violating the rules of fiqh by not allowing the accused an opportunity to defend himself, and because "even the most rigorous and extreme of the classical jurist only require a Muslim to kill anyone who insults the Prophet in his hearing and in his presence."[134]

Though Rushdie publicly regretted "the distress that publication has occasioned to sincere followers of Islam",[135] the fatwa was not revoked.

The fatwa was followed by a number of deaths, including the lethal stabbing of Hitoshi Igarashi, the Japanese translator of the book, in 1991. Rushdie himself and two other translators of the book survived murder attempts, the last – in Rushdie's case – in August 2022. The controversy, and subsequent unrest associated with the fatwa has been linked to surges in sales for Rushdie's work.[136][137]

Life under Khomeini

In a speech on 1 February 1979 delivered to a huge crowd after returning to Iran from exile, Khomeini made a variety of promises to Iranians for his coming Islamic regime: a popularly elected government that would represent the people of Iran and with which the clergy would not interfere. He promised that "no one should remain homeless in this country," and that Iranians would have free telephone, heating, electricity, bus services and free oil at their doorstep.[138]

Under Khomeini's rule, sharia (Islamic law) was introduced, with the Islamic dress code enforced for both men and women by Islamic Revolutionary Guards and other Islamic groups.[139] Women were required to cover their hair, and men were forbidden to wear shorts. Alcoholic drinks, most Western movies, and the practice of men and women swimming or sunbathing together were banned.[140] The Iranian educational curriculum was Islamized at all levels with the Islamic Cultural Revolution; the "Committee for Islamization of Universities"[141] carried this out thoroughly. The broadcasting of any music other than martial or religious on Iranian radio and television was banned by Khomeini in July 1979.[140] The ban lasted 10 years (approximately the rest of his life).[142]

According to Janet Afari, "the newly established regime of Ayatollah Khomeini moved quickly to repress feminists, ethnic and religious minorities, liberals, and leftists – all in the name of Islam."[143]

Women and child rights

Khomeini took on extensive and proactive support of the female populace during the ousting of the Shah and his subsequent homecoming, advocating for mainstreaming of women into all spheres of life and even hypothesizing about a woman head of state.[144] However, once he returned, his stances on women's rights exhibited drastic changes.[144] Khomeini revoked Iran's 1967 divorce law, considering any divorce granted under this law to be invalid.[144] Nevertheless, Khomeini supported women's right to divorce as allowed by Islamic law.[145] Khomeini reaffirmed the traditional position of rape in Islamic law in which rape by a spouse was not equivalent to rape or zina, declaring "Issue 2412- A woman who has entered into a permanent marriage should not go out of the house without her husband's permission, and she should surrender herself to whatever pleasure he wants and not prevent him from getting close to her without a legitimate excuse. If she obeys the husband in these matters, it is obligatory on the husband to provide her food, clothes, house and other items mentioned in the books, and if he does not provide, he is indebted to the wife, whether he has the ability or not. Issue 2413- If a woman does not obey her husband in the matters mentioned in the previous issue, she is a sinner and has no right to food, clothing, housing, and co-sleeping, but her dowry is not lost. Issue 2414- A man has no right to force his wife to serve the house.".[146][147][148][149]

A mere three weeks after assuming power, under the pretext of reversing the Shah's affinity for westernization and backed by a vocal conservative section of Iranian society, he revoked the divorce law.[144] Under Khomeini the minimum age of marriage was lowered to 15 for boys and 13 for girls;[150] nevertheless, the average age of women at marriage continued to increase.[150]

Laws were passed that encouraged polygamy, made it impossible for women to divorce men, and treated adultery as the highest form of criminal offense.[151][150] Women were compelled to wear veils and the image of Western women was carefully reconstructed as a symbol of impiety.[144] Morality and modesty were perceived as fundamental womanly traits that needed state protection, and concepts of individual gender rights were relegated to women's social rights as ordained in Islam.[144] Fatima was widely presented as the ideal emulatable woman.[144]

At the same time, amidst the religious orthodoxy, there was an active effort to rehabilitate women into employment. Female participation in healthcare, education and the workforce increased drastically during his regime.[144]

Reception among women of his regime has been mixed. Whilst a section were dismayed at the increasing Islamisation and concurrent degradation of women's rights, others did notice more opportunities and mainstreaming of relatively religiously conservative women.[144]

LGBTQ persecution

Shortly after his accession as supreme leader in February 1979, Khomeini imposed capital punishment on homosexuals. Between February and March, sixteen Iranians were executed due to offenses related to sexual violations.[152] Khomeini also created the "Revolutionary Tribunals". According to historian Ervand Abrahamian, Khomeini encouraged the clerical courts to continue implementing their version of the Shari'a. As part of the campaign to "cleanse" the society,[153] these courts executed over 100 drug addicts, prostitutes, homosexuals, rapists, and adulterers on the charge of "sowing corruption on earth."[154] According to author Arno Schmitt, "Khomeini asserted that 'homosexuals' had to be exterminated because they were parasites and corruptors of the nation by spreading the 'stain of wickedness.'"[155] In 1979, he had declared that the execution of homosexuals (as well as prostitutes and adulterers) was reasonable in a moral civilization in the same sense as cutting off decayed skin.[156]

Being transgender, however, was designated by Khomeini as a sickness that was able to be cured through gender-affirming surgery.[157] Since the mid-1980s, the Iranian government has legalized the practice of sex reassignment surgery (under medical approval) and the modification of pertinent legal documents to reflect the reassigned gender. In 1983, Khomeini passed a fatwa allowing gender reassignment operations as a cure for "diagnosed transsexuals", allowing for the basis of this practice becoming legal.[158][159]

Emigration and economy

Khomeini is said to have stressed "the spiritual over the material".[160][161] Six months after his first speech he expressed exasperation with complaints about the sharp drop in Iran's standard of living, saying that: "I cannot believe that the purpose of all these sacrifices was to have less expensive melons."[162] On another occasion emphasizing the importance of martyrdom over material prosperity, he said: "Could anyone wish his child to be martyred to obtain a good house? This is not the issue. The issue is another world."[163] He also reportedly answered a question about his economic policies by declaring that 'economics is for donkeys'.[d] This disinterest in economic policy is said to be "one factor explaining the inchoate performance of the Iranian economy since the revolution."[160] Other factors include the long war with Iraq, the cost of which led to government debt and inflation, eroding personal incomes, and unprecedented unemployment,[165] ideological disagreement over the economy, and "international pressure and isolation" such as US sanctions following the hostage crisis.[166]

Due to the Iran–Iraq War, poverty is said to have risen by nearly 45% during the first 6 years of Khomeini's rule.[167] Emigration from Iran also developed, reportedly for the first time in the country's history.[168] Since the revolution and war with Iraq, an estimated "two to four million entrepreneurs, professionals, technicians, and skilled craftspeople (and their capital)" have emigrated to other countries.[169][170]

Suppression of opposition

In a talk at the Fayzieah School in Qom on 30 August 1979, Khomeini warned pro-imperialist opponents: "Those who are trying to bring corruption and destruction to our country in the name of democracy will be oppressed. They are worse than Bani-Ghorizeh Jews, and they must be hanged. We will oppress them by God's order and God's call to prayer."[171][unreliable source?]

However, in 1983, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) helped him by providing a list of Soviet KGB agents and collaborators operating in Iran to Khomeini, who then executed up to 200 suspects and closed down the Communist Tudeh Party of Iran.[172][173]

The Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and his family left Iran and escaped harm, but hundreds of former members of the overthrown monarchy and military were executed by firing squads, with exiled critics complaining of "secrecy, vagueness of the charges, the absence of defense lawyers or juries", or the opportunity of the accused "to defend themselves."[174] In later years these were followed in larger numbers by the erstwhile revolutionary allies of Khomeini's movement—Marxists and socialists, mostly university students—who opposed the theocratic regime. From 1980 to 1981, the People's Mojahedin Organization of Iran and other opposition groups (including leftist and moderate groups) rallied against the takeover of the Islamic Republic Party through large demonstrations. Acting on the orders of Khomeini, the Islamic Republic responded by shooting demonstrators, including children.[175][176] The 1981 Hafte Tir bombing escalated the conflict, leading to increasing arrests, torture, and executions of thousands of Iranians. Targets also included "innocent, non political civilians, such as members of the Baha'i religious minority, and others deemed problematic by the IRP."[177][178][175] The number of those executed between 1981 and 1985's "reign of terror" is reported to be between 8,000 and 10,000.[176][179]

In the 1988 executions of Iranian political prisoners,[180][181][182] following the People's Mujahedin of Iran unsuccessful operation Forough-e Javidan against the Islamic Republic, Khomeini issued an order to judicial officials to judge every Iranian political prisoner (mostly but not all Mujahedin)[183] and kill those judged to be apostates from Islam (mortad) or "waging war on God" (moharebeh). Almost all of those interrogated were killed, 1,000 to 30,000 of them.[184][185][186] Because of the large number, prisoners were loaded into forklift trucks in groups of six and hanged from cranes in half-hour intervals.[187]

Minority religions

Zoroastrians, Jews, and Christians are officially recognized and protected by the government. Shortly after Khomeini's return from exile in 1979, he issued a fatwa ordering that Jews and other minorities (except those of the Baháʼí Faith) be treated well.[188][189] In power, Khomeini distinguished between Zionism as a secular political party that employs Jewish symbols and ideals and Judaism as the religion of Moses.[190]

Senior government posts were reserved for Muslims. Schools set up by Jews, Christians and Zoroastrians had to be run by Muslim principals.[191] Conversion to Islam was encouraged by entitling converts to inherit the entire share of their parents (or even uncle's) estate if their siblings (or cousins) remain non-Muslim.[192] Iran's non-Muslim population has decreased. For example, the Jewish population in Iran dropped from 80,000 to 30,000.[193] The Zoroastrian population has also decreased, due to suffering from renewed persecution and the revived legal contrasts between a Muslim and Zoroastrian, which mirrors the laws that Zoroastrians experienced under earlier Islamic regimes.[194] The view that Zoroastrians are najis ("unclean") has also been renewed.[194]

Four of the 270 seats in parliament were reserved for each three non-Muslim minority religions, under the Islamic constitution that Khomeini oversaw. Khomeini also called for unity between Sunni and Shi'a Muslims. Sunni Muslims make up 9% of the entire Muslim population in Iran.[195]

One non-Muslim group treated differently were the 300,000 members of the Baháʼí Faith. Starting in late 1979 the new government systematically targeted the leadership of the Baháʼí community by focusing on the Baháʼí National Spiritual Assembly (NSA) and Local Spiritual Assemblies (LSAs); prominent members of NSAs and LSAs were often detained and even executed.[196] "Some 200 of whom have been executed and the rest forced to convert or subjected to the most horrendous disabilities."[197]

Like most conservative Muslims, Khomeini believed Baháʼí to be apostates.[e] He claimed they were a political rather than a religious movement,[198][199] declaring:

the Baháʼís are not a sect but a party, which was previously supported by Britain and now the United States. The Baháʼís are also spies just like the Tudeh [Communist Party].[200]

Ethnic minorities

After the Shah left Iran in 1979, a Kurdish delegation traveled to Qom to present the Kurds' demands to Khomeini. Their demands included language rights and the provision for a degree of political autonomy. Khomeini responded that such demands were unacceptable since it involved the division of the Iranian nation.[201] In a speech during the same year, Khomeini hinted that the new government's attitudes were to curb contrasts instead of accepting them. Khomeini is quoted saying: "Sometimes the word minorities is used to refer to people such as Kurds, Lurs, Turks, Persians, Baluchis, and such. These people should not be called minorities because this term assumes there is a difference between these brothers."[202] The following months saw numerous clashes between Kurdish militia groups and the Revolutionary Guards.[201] The referendum on the Islamic Republic was massively boycotted in Kurdistan, where it was thought 85 to 90% of voters abstained. Khomeini ordered additional attacks later on in the year, and by September most of Iranian Kurdistan was under direct martial law.

Death and funeral

Khomeini's health declined several years prior to his death. After spending eleven days in Jamaran hospital, he died on 3 June 1989 after suffering five heart attacks in ten days.[203] He was succeeded as Supreme Leader by Ali Khamenei. Large numbers of Iranians took to the streets to publicly mourn his death and in the scorching summer heat, fire trucks sprayed water on the crowds to cool them.[204] At least 10 mourners were trampled to death, more than 400 were badly hurt and several thousand more were treated for injuries sustained in the ensuing pandemonium.[205][206]

According to Iran's official estimates, 10.2 million people lined the 32-kilometre (20 mi) route to Tehran's Behesht-e Zahra cemetery on 11 June 1989, for the funeral of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.[207][208][209] Western agencies estimated that 2 million paid their respects as the body lay in state.[210]

Figures about Khomeini's initial funeral attendance which took place on 4 June range around 2.5–3.5 million people.[211][212] Early the following day, Khomeini's corpse was flown in by helicopter for burial at the Behesht-e Zahra. Iranian officials postponed Khomeini's first funeral after a huge mob stormed the funeral procession, destroying Khomeini's wooden coffin in order to get a last glimpse of his body or touch of his coffin. In some cases, armed soldiers were compelled to fire warning shots in the air to restrain the crowds.[213] At one point, Khomeini's body fell to the ground, as the crowd ripped off pieces of the death shroud, trying to keep them as if they were holy relics. According to journalist James Buchan:

Yet even here, the crowd surged past the makeshift barriers. John Kifner wrote in The New York Times that the "body of the Ayatollah, wrapped in a white burial shroud, fell out of the flimsy wooden coffin, and in a mad scene people in the crowd reached to touch the shroud". A frail white leg was uncovered. The shroud was torn to pieces for relics and Khomeini's son Ahmad was knocked from his feet. Men jumped into the grave. At one point, the guards lost hold of the body. Firing in the air, the soldiers drove the crowd back, retrieved the body and brought it to the helicopter, but mourners clung on to the landing gear before they could be shaken off. The body was taken back to North Tehran to go through the ritual of preparation a second time.[214]

The second funeral was held under much tighter security five hours later. This time, Khomeini's casket was made of steel, and in accordance with Islamic tradition, the casket was only to carry the body to the burial site. In 1995, his son Ahmad was buried next to him. Khomeini's grave is now housed within a larger mausoleum complex.

Succession

Grand Ayatollah Hussein-Ali Montazeri, a former student of Khomeini and a major figure of the Revolution, was chosen by Khomeini to be his successor as Supreme Leader and approved as such by the Assembly of Experts in November 1985.[215] The principle of velayat-e faqih and the Islamic constitution called for the Supreme Leader to be a marja (a grand ayatollah),[216] and of the dozen or so grand ayatollahs living in 1981 only Montazeri qualified as a potential Leader (this was either because only he accepted totally Khomeini's concept of rule by Islamic jurists,[217][218][unreliable source?] or, as at least one other source stated, because only Montazeri had the "political credentials" Khomeini found suitable for his successor).[219] The execution of Mehdi Hashemi in September 1987 on charges of counterrevolutionary activities was a blow to Ayatollah Montazeri, who knew Hashemi since their childhood.[220] In 1989 Montazeri began to call for liberalization, freedom for political parties. Following the execution of thousands of political prisoners by the Islamic government, Montazeri told Khomeini: "Your prisons are far worse than those of the Shah and his SAVAK."[221] After a letter of his complaints was leaked to Europe and broadcast on the BBC, a furious Khomeini ousted him in March 1989 from his position as official successor.[222] His portraits were removed from offices and mosques.[223]

To deal with the disqualification of the only suitable marja, Khomeini called for an 'Assembly for Revising the Constitution' to be convened. An amendment was made to Iran's constitution removing the requirement that the Supreme Leader be a Marja[217] and this allowed Ali Khamenei, the new favoured jurist who had suitable revolutionary credentials but lacked scholarly ones and who was not a Grand Ayatollah, to be designated as successor.[224][225] Ayatollah Khamenei was elected Supreme Leader by the Assembly of Experts on 4 June 1989. Grand Ayatollah Hossein Montazeri continued his criticism of the regime and in 1997 was put under house arrest for questioning what he regarded to be an unaccountable rule exercised by the supreme leader.[226][227]

Anniversary

The anniversary of Khomeini's death is a public holiday.[228][229][230] To commemorate Khomeini, people visit his mausoleum placed on Behesht-e Zahra to hear sermons and practice prayers on his death day.[231][126][232][233]

Reception, political thought and legacy

According to at least one scholar, politics in the Islamic Republic of Iran "are largely defined by attempts to claim Khomeini's legacy" and that "staying faithful to his ideology has been the litmus test for all political activity" there.[234] Throughout his many writings and speeches, Khomeini's views on governance evolved. Originally declaring rule by monarchs or others permissible so long as sharia law was followed[235] Khomeini later adamantly opposed monarchy, arguing that only rule by a leading Islamic jurist (a marja') would ensure Sharia was properly followed (velâyat-e faqih),[236] before finally insisting the ruling jurist need not be a leading one and Sharia rule could be overruled by that jurist if necessary to serve the interests of Islam and the "divine government" of the Islamic state.[237]Khomeini's concept of Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist (ولایت فقیه, velayat-e faqih) as Islamic government did not win the support of the leading Iranian Shi'i clergy of the time.[238] Towards the 1979 Revolution, many clerics gradually became disillusioned with the rule of the Shah, although none came around to supporting Khomeini's vision of a theocratic Islamic Republic.[238] Khomeini has been described as the "virtual face of Shia Islam in Western popular culture".[239]

There is much debate to as whether Khomeini's ideas are or are not compatible with democracy and whether he intended the Islamic Republic to be a democratic republic. According to the state-run Aftab News,[240] both ultraconservative supporters (Mohammad Taghi Mesbah Yazdi) and reformist opponents of the regime (Akbar Ganji and Abdolkarim Soroush) believe he did not, while regime officials and supporters like Ali Khamenei,[241] Mohammad Khatami and Mortaza Motahhari[242] maintain the Islamic republic is democratic as Khomeini intended it to be.[243] Khomeini himself also made statements at different times indicating both support and opposition to democracy.[244]One scholar, Shaul Bakhash, explains this contradiction as coming from Khomeini's belief that the huge turnout of Iranians in anti-Shah demonstrations during the revolution constituted a 'referendum' in favor of an Islamic republic, more important than any elections.[245] Khomeini also wrote that since Muslims must support a government based on Islamic law, Sharia-based government will always have more popular support in Muslim countries than any government based on elected representatives.[246]

Khomeini offered himself as a "champion of Islamic revival" and unity, emphasizing issues Muslims agreed upon – the fight against Zionism and imperialism – and downplaying Shia issues that would divide Shia from Sunni.[247] (The Egyptian Jihadist ideologue Sayyid Qutb was an important source of influence to Khomeini and the 1979 Iranian Revolution. The Islamic Republic of Iran under Khomeini honoured Qutb's "martyrdom" by issuing an iconic postage stamp in 1984, and before the revolution prominent figures in the Khomeini network translated Qutb's works into Persian.)[248][249] While he publicly spoke of Islamic unity and minimized differences with Sunni Muslims, he is accused by some of privately rebuking Sunni Islam as heretical and covertly promoted an anti-Sunni foreign policy in the region.[250][251]

Khomeini has also been lauded as politically astute, a "charismatic leader of immense popularity",[252] a "champion of Islamic revival" by Shia scholars,[239] and a major innovator in political theory and religious-oriented populist political strategy.[253][254]

Khomeini strongly opposed close relations with either Eastern or Western Bloc nations, believing the Islamic world should be its own bloc, or rather converge into a single unified power.[255] He viewed Western culture as being inherently decadent and a corrupting influence upon the youth. The Islamic Republic banned or discouraged popular Western fashions, music, cinema, and literature.[256] In the Western world it is said "his glowering visage became the virtual face of Islam in Western popular culture" and "inculcated fear and distrust towards Islam,"[257] making the word 'Ayatollah' "a synonym for a dangerous madman ... in popular parlance."[258] This has particularly been the case in the United States where some Iranians complained that even at universities they felt the need to hide their Iranian identity for fear of physical attack.[110] There Khomeini and the Islamic Republic are remembered for the American embassy hostage taking and accused of sponsoring hostage-taking and terrorist attacks,[259][260] and which continues to apply economic sanctions against Iran.

Before taking power Khomeini expressed support for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. "We would like to act according to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. We would like to be free. We would like independence."[261] However once in power Khomeini took a firm line against dissent, warning opponents of theocracy for example: "I repeat for the last time: abstain from holding meetings, from blathering, from publishing protests. Otherwise I will break your teeth."[262]

Many of Khomeini's political and religious ideas were considered to be progressive and reformist by leftist intellectuals and activists prior to the Revolution. However, once in power his ideas often clashed with those of modernist or secular Iranian intellectuals. This conflict came to a head during the writing of the Islamic constitution when many newspapers were closed by the government. Khomeini angrily told the intellectuals:

Yes, we are reactionaries, and you are enlightened intellectuals: You intellectuals do not want us to go back 1400 years. You, who want freedom, freedom for everything, the freedom of parties, you who want all the freedoms, you intellectuals: freedom that will corrupt our youth, freedom that will pave the way for the oppressor, freedom that will drag our nation to the bottom.[263]

In contrast to his alienation from Iranian intellectuals, and "in an utter departure from all other Islamist movements," Khomeini embraced international revolution and Third World solidarity, giving it "precedence over Muslim fraternity." From the time Khomeini's supporters gained control of the media until his death, the Iranian media "devoted extensive coverage to non-Muslim revolutionary movements (from the Sandinistas to the African National Congress and the Irish Republican Army) and downplayed the role of the Islamic movements considered conservative, such as the Afghan mujahidin."[264] Khomeini's supporters and pro-government media in Iran also claim that he was a fighter against racism.[265] Khomeini was a staunch critic of the Apartheid regime in South Africa.[266] After the 1979 Iranian Revolution, anti-Apartheid activist and African National Congress president Oliver Tambo sent a letter to congratulate Khomeini for the success of the revolution.[267] Former South African President Nelson Mandela claimed several times that Khomeini served as an inspiration for the anti-apartheid movement.[268][269] During the 1979 Iran hostage crisis, Khomeini ordered the release of all female and African-American staff working there.[270]

Khomeini's legacy to the economy of the Islamic Republic has been expressions of concern for the mustazafin (a Quranic term for the oppressed or deprived), but not always results that aided them. During the 1990s the mustazafin and disabled war veterans rioted on several occasions, protesting the demolition of their shantytowns and rising food prices, etc.[271] Khomeini's disdain for the science of economics is said to have been "mirrored" by the populist redistribution policies of former president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who allegedly wears "his contempt for economic orthodoxy as a badge of honour", and has overseen sluggish growth and rising inflation and unemployment.[272]

In 1963, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini wrote a book in which he stated that there is no religious restriction on corrective surgery for transgender individuals. At the time Khomeini was an anti-Shah revolutionary and his fatwas did not carry any weight with the Imperial government, which did not have any specific policies regarding transsexual individuals.[273]However, after 1979, his fatwa "formed the basis for a national policy" and perhaps in part because of a penal code that "allows for the execution of homosexuals", as of 2005 Iran "permits and partly finances seven times as many gender reassignment operations as the entire European Union".[274][275]

Appearance and habits

Khomeini was described as "slim", but athletic and "heavily boned".[276]

He was known for his punctuality:

He's so punctual that if he doesn't turn up for lunch at exactly ten past everyone will get worried, because his work is regulated in such a way that he turned up for lunch at exactly that time every day. He goes to bed exactly on time. He eats exactly on time. And he wakes up exactly on time. He changes his cloak every time he comes back from the mosque.[277]

Khomeini was also known for his aloofness and austere demeanor. He is said to have had "variously inspired admiration, awe, and fear from those around him."[278] His practice of moving "through the halls of the madresehs never smiling at anybody or anything; his practice of ignoring his audience while he taught, contributed to his charisma."[279]

Khomeini adhered to traditional beliefs of Islamic hygienical jurisprudence holding that things like urine, excrement, blood, wine, and also non-Muslims were some of the eleven ritualistically "impure" things that physical contact with which while wet required ritual washing or Ghusl before prayer or salat.[280][281] He is reported to have refused to eat or drink in a restaurant unless he knew for sure the waiter was a Muslim.[282]

Mystique

According to Baqer Moin, with the success of the revolution, not only had a personality cult developed around Khomeini, but he "had been transformed into a semi-divine figure. He was no longer a grand ayatollah and deputy of the Imam, one who represents the Hidden Imam, but simply 'The Imam'."[283] Khomeini's cult of personality fills a central position in foreign- and domestically targeted Iranian publications.[284][285][286][287] The methods used to create his personality cult have been compared to those used by such figures as Joseph Stalin, Mao Zedong and Fidel Castro.[288][289][290]

An eight-century Hadith attributed to the Imam Musa al-Kazim that said "A man will come out from Qom and he will summon people to the right path. There will rally to him people resembling pieces of iron, not to be shaken by violent winds, unsparing and relying on God" was repeated in Iran as a tribute to Khomeini. (In Lebanon, however, this saying was also attributed to Musa al-Sadr.)[291]

Khomeini was the first and only Iranian cleric to be addressed as "Imam",[5][292][293] a title hitherto reserved in Iran for the twelve infallible leaders of the early Shi'a.[294] He was also associated with the Mahdi or 12th Imam of Shia belief in a number of ways. One of his titles was Na'eb-e Imam (Deputy to the Twelfth Imam). His enemies were often attacked as taghut and Mofsed-e-filarz, religious terms used for enemies of the Twelfth Imam. Many of the officials of the overthrown Shah's government executed by Revolutionary Courts were convicted of "fighting against the Twelfth Imam". When a deputy in the majlis asked Khomeini directly if he was the 'promised Mahdi', Khomeini did not answer, "astutely" neither confirming nor denying the title.[295]

As the revolution gained momentum, even some non-supporters exhibited awe towards Khomeini, called him "magnificently clear-minded, single-minded and unswerving."[296] His image was as "absolute, wise, and indispensable leader of the nation":[297]

The Imam, it was generally believed, had shown by his uncanny sweep to power, that he knew how to act in ways which others could not begin to understand. His timing was extraordinary, and his insight into the motivation of others, those around him as well as his enemies, could not be explained as ordinary knowledge. This emergent belief in Khomeini as a divinely guided figure was carefully fostered by the clerics who supported him and spoke up for him in front of the people.[298]

Even many secularists who firmly disapproved of his policies were said to feel the power of his "messianic" appeal.[299] Comparing him to a father figure who retains the enduring loyalty even of children he disapproves of, journalist Afshin Molavi writes that defenses of Khomeini are "heard in the most unlikely settings":

A whiskey-drinking professor told an American journalist that Khomeini brought pride back to Iranians. A women's rights activist told me that Khomeini was not the problem; it was his conservative allies who had directed him wrongly. A nationalist war veteran, who held Iran's ruling clerics in contempt, carried with him a picture of 'the Imam'.[300]

Another journalist tells the story of listening to bitter criticism of the regime by an Iranian who tells her of his wish for his son to leave the country and who "repeatedly" makes the point "that life had been better" under the Shah. When his complaint is interrupted by news that "the Imam" – over 85 years old at the time and known to be ailing – might be dying, the critic becomes "ashen faced" and speechless, pronouncing the news to be "terrible for my country."[301]

Non-Iranians were not immune from the effect. In 1982, after listening to a half-hour-long speech on the Quran by him, a Muslim scholar from South Africa, Sheikh Ahmad Deedat gushed:

... the electric effect he had on everybody, his charisma, was amazing. You just look at the man and tears come down your cheek. You just look at him and you get tears. I never saw a more handsome old man in my life, no picture, no video, no TV could do justice to this man, the handsomest old man I ever saw in my life was this man.[302]

Family and descendants

In 1929[303][304] (or possibly 1931),[305] Khomeini married Khadijeh Saqafi,[306] the daughter of a cleric in Tehran. Some sources claim that Khomeini married Saqafi when she was ten years old,[307][308][309] while others claim she was fifteen years old.[310] By all accounts their marriage was harmonious and happy.[306] She died on 21 March 2009, at the age of 93.[305][311] They had seven children, though only five survived infancy. His daughters all married into either merchant or clerical families, and both his sons entered into religious life. Mostafa, the elder son, died in 1977 while in exile in Najaf, Iraq with his father and was rumored by supporters of his father to have been murdered by SAVAK.[312] Ahmad Khomeini, who died in 1995 at the age of 50, was also rumoured to be a victim of foul play, but at the hands of the regime.[313] Perhaps his "most prominent daughter",[314] Zahra Mostafavi, is a professor at the University of Tehran, and still alive.

Khomeini's fifteen grandchildren include:

- Zahra Eshraghi, granddaughter, married to Mohammad Reza Khatami, head of the Islamic Iran Participation Front, the main reformist party in the country, and is considered a pro-reform character herself.

- Hassan Khomeini, Khomeini's elder grandson Sayid Hasan Khomeini, son of the Seyyed Ahmad Khomeini, is a cleric and the trustee of the Mausoleum of Khomeini and also has shown support for the reform movement in Iran,[315] and Mir-Hossein Mousavi's call to cancel the 2009 election results.[314]

- Husain Khomeini (Sayid Husain Khomeini), Khomeini's other grandson, son of Sayid Mustafa Khomeini, is a mid-level cleric who is strongly against the system of the Islamic republic. In 2003, he was quoted as saying: "Iranians need freedom now, and if they can only achieve it with American interference I think they would welcome it. As an Iranian, I would welcome it."[316] In that same year Husain Khomeini visited the United States, where he met figures such as Reza Pahlavi, the son of the last Shah and the pretender to the Sun Throne. Later that year, Husain returned to Iran after receiving an urgent message from his grandmother. According to Michael Ledeen, quoting "family sources", he was blackmailed into returning.[317] In 2006, he called for an American invasion and overthrow of the Islamic Republic, telling Al-Arabiyah television station viewers, "If you were a prisoner, what would you do? I want someone to break the prison [doors open].[318]

- Another of Khomeini's grandchildren, Ali Eshraghi, was disqualified from the 2008 parliamentary elections on grounds of being insufficiently loyal to the principles of the Islamic revolution, but later reinstated.[319]

Bibliography

Khomeini was a writer and speaker (200 of his books are online)[320] who authored commentaries on the Qur'an, on Islamic jurisprudence, the roots of Islamic law, and Islamic traditions. He also released books about philosophy, gnosticism, poetry, literature, government and politics.[321][better source needed]

His books include:

- Hokumat-e Islami: Velayat-e faqih (Islamic Government: Governance of the Jurist)

- The Little Green Book: A sort of manifesto of Khomeini's political thought

- Forty Hadith[322] (Forty Traditions)

- Adab as Salat[323] (The Disciplines of Prayers)

- Jihade Akbar[324] (The Greater Struggle)

- Tahrir al-Wasilah

- Kashf al-Asrar

See also

- 1979 Iranian Revolution conspiracy theory

- Abdallah Mazandarani

- Execution of Imam Khomeini's Order

- Exiles of Imam Khomeini

- Fazlullah Nouri

- Идеократия

- Исламский фундаментализм в Иране

- Исламское правительство (книга Хомейни)

- хомейнизм

- Список культов личности

- Мирза Али Ака Тебризи

- Мирза Хусейн Тегерани

- Мирза Сайед Мохаммад Табатабай

- Мухаммад Бакир аль-Хаким

- Мухаммад Бакир ас-Садр

- Мухаммад Казим Хурасани

- Политическая мысль и наследие Рухоллы Хомейни

- Письмо Рухоллы Хомейни Михаилу Горбачеву

- Резиденция Рухоллы Хомейни (Джамаран)

- Сейед Абдолла Бехбахани

Примечания

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б См. § Детство .

- ^

- Великобритания : / x ɒ ˈ m eɪ n i / Come- AY -nee , США : / x oʊ -/ хом-

- Персидский : Рухолла Хомейни , латинизированный : Рухолла Хомейни , произносится [ɾuːholˈlɒːhe xomejˈniː]

- ↑ В «Предупреждении нации», опубликованном в 1941 году, Хомейни писал: «Нам нечего сказать тем… [кто] настолько полностью уступил свои способности иностранцам, что они даже подражают им в вопросах времени; что остается ли нам сказать им? Как вы все знаете, в Тегеране теперь официально отсчитывают полдень за двадцать минут до того, как солнце достигнет меридиана, в подражание Европе. До сих пор никто не встал и не спросил: «Что это за кошмар». это то, во что нас погружают?»

До введения системы международных часовых поясов в каждом населенном пункте было свое собственное время: 12 часов дня соответствовало моменту в этом городе, когда солнце находилось в самой высокой точке неба. Это было естественно для эпохи, когда путешествия были относительно медленными и редкими, но нанесли бы ущерб расписаниям поездов и современной междугородной связи. В течение десятилетий после 1880 года правительства по всему миру заменили местное время 24 международными часовыми поясами, каждый из которых охватывает 15 градусов земной долготы (за некоторыми исключениями для политических границ). Хомейни, Рухолла (1981). Ислам и революция: сочинения и заявления имама Хомейни . Перевод и аннотации Хамида Алгара. Беркли, Калифорния: Mizan Press. п. 172 . [ нужен неосновной источник ] - ^ Источник: [164] Оригинальную цитату из речи, произнесенной в 1979 году, можно найти здесь :

Я не могу себе представить, да и ни один мудрый человек не может предположить, что мы экономили свою кровь, чтобы арбуз стал дешевле. Ни один мудрый человек не станет жертвовать своим молодым потомством ради, скажем, доступного жилья. Люди [наоборот] хотят всего для своего молодого потомства. Человек хочет экономии для себя самого; поэтому с его стороны было бы неразумно жалеть свою жизнь ради улучшения экономики [...] Те, кто продолжает поднимать экономику и находит экономику инфраструктурой всего, - не зная, что означает человечность, - думают о человеке как о животное, которое определяется посредством еды и одежды [...] Те, кто считает экономику инфраструктурой всего, считают людей животными. Животные тоже жертвуют всем ради своей экономики, а экономика — это единственная инфраструктура. Осел тоже считает экономику своей единственной инфраструктурой . Эти люди не осознавали, что такое человек [на самом деле].

- ^ Например, он издал фетву, в которой говорилось:

Из Подушного налога, 8. Условия дани, (13), Тахрир аль-Василе , том 2, стр. 497–507, цитируется в «Разъяснении вопросов: полный перевод Ресалех Таузих аль-Масаэль» аятоллы Сайеда Рухоллы Мусави Хомейни, Westview Press / Боулдер и Лондон, c1984, стр.432.Недопустимо, чтобы данник [немусульманин, который платит дань] менял свою религию на другую религию, не признанную последователями предыдущей религии. Например, от евреев, ставших бахаи, не принимается ничего, кроме ислама или казни.

Ссылки

Цитаты

- ^ Бауэринг, Герхард; Кроун, Патрисия; Кади, Вадад; Стюарт, Девин Дж.; Заман, Мухаммад Касим; Мирза, Махан, ред. (2012). Принстонская энциклопедия исламской политической мысли . Издательство Принстонского университета. п. 518. ИСБН 978-1-4008-3855-4 .

- ^ Мализ Рутвен (2004). Фундаментализм: поиск смысла (переиздание). Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 29. ISBN 978-0-19-151738-9 .

- ^ Джебнун, Нуреддин; Киа, Мехрдад; Кирк, Мими, ред. (2013). Современный ближневосточный авторитаризм: корни, разветвления и кризис . Рутледж. п. 168. ИСБН 978-1-135-00731-7 .

- ^ «Конституция Исламской Республики Иран, Глава 1, Статья 1» . Конституция Исламской Республики Иран .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Мойн, Хомейни (2001), с. 201

- ^ Абрамян, Ерванд (1989). Радикальный ислам: иранские моджахеды . ИБ Таурис. п. 20. ISBN 1-85043-077-2 .

- ^ Алгар, Хамид (2010). «Краткая биография». В Койе, Абдар Рахман (ред.). Имам Хомейни: жизнь, мысли и наследие . Исламский книжный фонд. п. 19. ISBN 978-9675062254 .

- ^ Священное пространство и священная война: политика, культура и история шиитского ислама Хуана Рикардо Коула

- ^ Искусство и культура: попытки интерпретации Ахсана Джана Кайсара, Сом Пракаша Вермы, Мохаммеда Хабиба

- ↑ Энциклопедия Ираника , «Авад». Архивировано 17 мая 2017 года в Wayback Machine , Э. Яршатер.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Краткая биография Рухоллы Хомейни, написанная Хамидом Алгаром

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Из Хомейна, Биография аятоллы , 14 июня 1999 г., The Иранский