Движение MeToo

Было предложено эффект Вайнштейна объединить в эту статью. ( Обсудить ) Предлагается с марта 2024 г. |

#Я тоже [а] — это общественное движение и информационная кампания против сексуального насилия , сексуальных домогательств и культуры изнасилования , в ходе которой люди рассказывают о своем опыте сексуального насилия или сексуальных домогательств. [1] [2] [3] Фраза «Me Too» первоначально была использована в этом контексте в социальных сетях в 2006 году на Myspace активисткой сексуального насилия и жертвой Тараной Берк . [4] Хэштег использовался начиная с 2017 года как #MeToo способ привлечь внимание к масштабам проблемы. «Me Too» расширяет возможности тех, кто подвергся сексуальному насилию, посредством сочувствия, солидарности и силы, наглядно демонстрируя, как многие из них подверглись сексуальному насилию и домогательствам, особенно на рабочем месте. [4] [5] [6]

После разоблачения многочисленных обвинений в сексуальном насилии против кинопродюсера Харви Вайнштейна в октябре 2017 года [7] [8] движение начало вирусно распространяться в виде хэштега в социальных сетях. [6] [9] [10] 15 октября 2017 года американская актриса Алисса Милано написала в Твиттере : «Если бы все женщины, подвергшиеся сексуальным домогательствам или насилию, написали бы в статусе «Я тоже», мы могли бы дать людям представление о масштабах проблемы», — заявила она. что ей пришла идея от друга. [11][12][13][14] A number of high-profile posts and responses from American celebrities Gwyneth Paltrow,[15] Ashley Judd,[16] Jennifer Lawrence,[17] and Uma Thurman,[18] among others, soon followed. Widespread media coverage and discussion of sexual harassment, particularly in Hollywood, led to high-profile terminations from positions held, as well as criticism and backlash.[19][20][21]

After millions of people started using the phrase and hashtag in this manner in English, the expression began to spread to dozens of other languages. The scope has become somewhat broader with this expansion, however, and Burke has more recently referred to it as an international movement for justice for marginalized people.[22] After the hashtag #MeToo went viral in late 2017, Facebook reported that almost half of its American users were friends with someone who said they had been sexually assaulted or harassed.[23]

Purpose[edit]

The original purpose of "Me Too" as used by Tarana Burke in 2006 was to empower women through empathy, especially young and vulnerable women. In October 2017, Alyssa Milano encouraged using the phrase as a hashtag to help reveal the extent of problems with sexual harassment and assault by showing how many people have experienced these events themselves. It therefore encourages women to speak up about their abuses, knowing that they are not alone.[4][5]

After millions of people started using the phrase, and it spread to dozens of other languages, the purpose changed and expanded, and as a result, it has come to mean different things to different people. Tarana Burke accepts the title of "leader" of the movement, but has stated that she considers herself more of a "worker". Burke has stated that this movement has grown to include both men and women of all colors and ages, as it continues to support marginalized people in marginalized communities.[19][22] There have also been movements by men aimed at changing the culture through personal reflection and future action, including #IDidThat, #IHave, and #IWill.[24]

Awareness and empathy[edit]

Analyses of the movement often point to the prevalence of sexual violence, which has been estimated by the World Health Organization to affect one-third of all women worldwide. A 2017 poll by ABC News and The Washington Post also found that 54% of American women report receiving "unwanted and inappropriate" sexual advances with 95% saying that such behavior usually goes unpunished. Others state that #MeToo underscores the need for men to intervene when they witness demeaning behavior.[25][26][27]

Burke said that #MeToo declares sexual violence sufferers are not alone and should not be ashamed.[28] Burke says sexual violence is usually caused by someone the woman knows, so people should be educated from a young age that they have the right to say no to sexual contact from any person, even after repeated solicitations from an authority or spouse, and to report predatory behavior.[29] Burke advises men to talk to each other about consent, call out demeaning behavior when they see it and try to listen to victims when they tell their stories.[29]

Alyssa Milano said that #MeToo has helped society understand the "magnitude of the problem" and that "it's a standing in solidarity to all those who have been hurt."[30][31] She stated that the success of #MeToo will require men to take a stand against behavior that objectifies women.[32]

Policies and laws[edit]

Burke has stated the current purpose of the movement is to give people the resources to have access to healing, and to advocate for changes to laws and policies. Burke has highlighted goals such as processing all untested rape kits, re-examining local school policies, improving the vetting of teachers, and updating sexual harassment policies.[33] She has called for all professionals who work with children to be fingerprinted and subjected to a background check before being cleared to start work. She advocates for sex education that teaches kids to report predatory behavior immediately.[29] Burke supports the #MeToo bill in the US Congress, which would remove the requirement that staffers of the federal government go through months of "cooling off" before being allowed to file a complaint against a Congressperson.[33]

Milano stated in 2017 that a priority for #MeToo is changing the laws surrounding sexual harassment and assault, for example instituting protocols that allow sufferers in all industries to file complaints without retaliation. She supported legislation making it difficult for publicly traded companies to hide cover-up payments from their stockholders and would like to make it illegal for employers to require new workers to sign non-disclosure agreements as a condition of employment.[32] Gender analysts such as Anna North have stated that #MeToo should be addressed as a labor issue due to the economic disadvantages to reporting harassment. North suggested combating underlying power imbalances in some workplaces, for example by raising the tipped minimum wage, and embracing innovations like the "portable panic buttons" mandated for hotel employees in Seattle.[34]

In Hong Kong, the ruling in the case of C v. Hau Kar Kit [2023] HKDC 974 sent a strong reminder to employers that there should be zero tolerance to sexual harassment in the workplace. It turned out that the employer was also held liable under the Sex Discrimination Ordinance for unlawful act committed by any of their employees during the course of their employment, regardless of whether the employers have knowledge of the unlawful act.[35]

Others have suggested that barriers to employment must be removed, such as the job requirement by some employers to sign non-disclosure agreements or other agreements that prevent an employee from talking about their employment publicly, or taking disputes (including sexual harassment claims) to arbitration rather than to legal proceedings. It's been suggested that legislation should be passed that bans these types of mandatory pre-employment agreements.[1]

Some policy-based changes that have been suggested include increasing managerial oversight; creating clear internal reporting mechanisms; more effective and proactive disciplinary measures; creating a culture that encourages employees to be open about serious problems;[1] imposing financial penalties for companies that allow workers to remain in their position when they have repeatedly sexually harassed others; and forcing companies to pay huge fines or lose tax breaks if they decide to retain workers who are sexual harassers.[36]

Media coverage[edit]

In the coverage of #MeToo, there has been widespread discussion about the best ways to stop sexual harassment and abuse - for those currently being victimized at work, as well as those who are seeking justice for past abuse and trying to find ways to end what they see as a widespread culture of abuse. There is general agreement that a lack of effective reporting options is a major factor that drives unchecked sexual misconduct in the workplace.[37]

False reports of sexual assault are very rare,[38] but when they happen, they are put in the spotlight for the public to see. This can give the false impression that most reported sexual assaults are false. However, false reports of sexual assault account for only 2% to 10% of all reports.[39][40] These figures do not take into account that the majority of victims do not report when they are assaulted or harassed. Misconceptions about false reports are one of the reasons why women are scared to report their experiences with sexual assault - because they are afraid that no one will believe them, that in the process they will have embarrassed and humiliated themselves, in addition to opening themselves up to retribution from the assailants.[41][42]

In France, a person who makes a sexual harassment complaint at work is reprimanded or fired 40% of the time, while the accused person is typically not investigated or punished.[43] In the United States, a 2016 report from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission states that although 25–85% of women say they experience sexual harassment at work, few ever report the incidents, most commonly due to fear of reprisal.[37] There is evidence that in Japan, as few as 4% of rape victims report the crime, and the charges are dropped about half the time.[44][45]

There is a discussion on the best ways to handle whisper networks, or private lists of "people to avoid" that are shared unofficially in nearly every major institution or industry where sexual harassment is common due to power imbalances, including government, media, news, and academia. These lists have the stated purpose of warning other workers in the industry and are shared from person-to-person, on forums, in private social media groups, and via spreadsheets. However, it has been argued that these lists can become "weaponized" and be used to spread unsubstantiated gossip — an opinion which has been discussed widely in the media.[46]

Defenders say the lists provide a way to warn other vulnerable people in the industry if worried about serious retribution from the abusers, especially if complaints have already been ignored. They say the lists help victims identify each other so they can speak out together and find safety in numbers.[46][47] Sometimes these lists are kept for other reasons. For example, a spreadsheet from the United Kingdom called "High Libido MPs" and dubbed "the spreadsheet of shame" was created by a group of male and female Parliamentary researchers, and contained a list of allegations against nearly 40 Conservative MPs in the British Parliament. It is also rumored that party whips (who are in charge of getting members of Parliament to commit to votes) maintain a "black book" that contains allegations against several lawmakers that can be used for blackmail.[48][49][50] When it is claimed a well-known person's sexual misconduct was an "open secret", these lists are often the source.[46] In the wake of #MeToo, several private whisper network lists have been leaked to the public.[46][47]

In India, a student gave her friends a list containing names of professors and academics in the Indian university system to be avoided, which later went viral after it was posted on social media.[51] In response to criticism in the media, the authors defended themselves by saying they were only trying to warn their friends, had confirmed every case, and several victims from the list were poor students who had already been punished or ignored when trying to come forward.[52][53] Moira Donegan, a New York City-based journalist, privately shared a crowd-sourced list of "Shitty Media Men" to avoid in publishing and journalism. When it was shared outside her private network, Donegan lost her job. She stated it was unfair so few people had access to the list before it went public; for example, very few women of color received access (and therefore protection) from it. She pointed to her "whiteness, health, education, and class" that allowed her to take the risk of sharing the list and getting fired.[47]

The main problem with trying to protect more potential victims by publishing whisper networks is determining the best mechanism to verify allegations in a way that is fair to all parties.[54][55] Some suggestions have included strengthening labor unions in vulnerable industries so workers can report harassment directly to the union instead of to an employer. Another suggestion is to maintain industry hotlines which have the power to trigger third-party investigations.[54] Several apps have been developed which offer various ways to report sexual misconduct, and some can connect victims who have reported the same person.[56]

In a 2021 study about the #MeToo movement on YouTube and understanding the different perspectives, there are responses and reactions by people to videos based on the #MeToo movement.[57]

Issues with social norms[edit]

In the wake of #MeToo, many countries, such as the U.S.,[58] India,[59] France,[60] China,[61] Japan,[62] Italy,[63] and Israel,[64] have seen discussion in the media on whether cultural norms need to be changed for sexual harassment to be eradicated. John Launer of Health Education England stated leaders must be made aware of common "mismatches of perceptions" at work to reduce incidents where one person thinks they are flirting while the other person feels like they are being demeaned or harassed.[65] Reporter Anna North from Vox states one way to address #MeToo is to teach children the basics of sex. North states the cultural notion that women do not enjoy sex leads men "to believe that a lukewarm yes is all they're ever going to get", referring to a 2017 study which found that men who believe women enjoy being forced into sex are "more likely to perceive women as consenting".[66]

Alyssa Rosenberg of The Washington Post called for society to be careful of overreaching by "being clear about what behavior is criminal, what behavior is legal but intolerable in a workplace, and what private intimate behavior is worthy of condemnation" but not part of the workplace discussion. She says "preserving the nuances" is more inclusive and realistic.[67] Professor Daniel Drezner stated that #MeToo laid the groundwork for two major cultural shifts. One is the acceptance that sexual harassment (not just sexual assault) is unacceptable in the workplace. The other is that when a powerful person is accused of sexual harassment, the reaction should be a presumption that the less powerful accuser is "likely telling the truth, because the risks of going public are great". However, he states society is struggling with the speed at which change is being demanded.[68]

Reform and implementation[edit]

Although #MeToo initially focused on adults, the message spread to students in K–12 schools where sexual abuse is common both in person and online.[69] MeTooK12 is a spin-off of #MeToo created in January 2018 by the group Stop Sexual Assault in Schools, founded by Joel Levin and Esther Warkov, aimed at stopping sexual abuse in education from kindergarten to high school.[70][71] #MeTooK12 was inspired in part by the removal of certain federal Title IX sexual misconduct guidelines.[72] There is evidence that sexual misconduct in K–12 education is dramatically underreported by both schools and students, because nearly 80% of public schools never report any incidents of harassment. A 2011 survey found 40% of boys and 56% of girls in grades 7–12 reported had experienced negative sexual comments or sexual harassment in their lives.[70][72] Approximately 5% of K–12 sexual misconduct reports involved 5 or 6-year-old students. #MeTooK12 is meant to demonstrate the widespread prevalence of sexual misconduct towards children in school, and the need for increased training on Title IX policies, as only 18 states require people in education to receive training about what to do when a student or teacher is sexually abused.[71]

Role of men[edit]

There has been discussion about what possible roles men may have in the #MeToo movement.[73][74][75] It has been noted that 1 in 6 men have experienced sexual abuse of some sort during their lives and often feel unable to talk about it.[76] Creator Tarana Burke and others have asked men to call out bad behavior when they see it,[74][75] or just spend time quietly listening.[19][77] Some men have expressed the desire to keep a greater distance from women since #MeToo went viral because they do not fully understand what actions might be considered inappropriate.[78][79] For the first few months after #MeToo started trending, many men expressed difficulty in participating in the conversation due to fear of negative consequences, citing examples of men who have been treated negatively after sharing their thoughts about #MeToo.[80]

Author and former pick-up artist Michael Ellsberg encourages men to reflect on past behavior and examples of questionable sexual behavior, such as the viral story Cat Person, written from the perspective of a twenty-year-old woman who goes on a date with a much older man and ends up having an unpleasant sexual experience that was consensual but unwanted. Ellsberg has asked men to pledge to ensure women are mutually interested in initiating a sexual encounter and to slow down if there is ever doubt a woman wants to continue.[81][82] Relationship instructor Kasia Urbaniak said the movement is creating its own crisis around masculinity. "There's a reflective questioning about whether they're going to be next and if they've ever hurt a woman. There's a level of anger and frustration. If you've been doing something wrong but haven't been told, there's an incredible sense of betrayal and it'll provoke a backlash. I think silence on both sides is incredibly dangerous." Urbaniak says she would like women to be allies of men and to be curious about their experience. "In that alliance there's a lot more power and possibility than there is in men stepping aside and starting to stew."[83]

In August 2018, The New York Times detailed allegations that leading #MeToo figure Asia Argento sexually assaulted actor Jimmy Bennett.[84] The sexual assault allegedly took place in a California hotel room in 2013 when he was only two months past his 17th birthday and she was 37; the age of consent in that state is 18.[84] Bennett said when Argento came out against Harvey Weinstein, it stirred memories of his own experience. He imparted he had sought to resolve the matter privately, and had not spoken out sooner, "because I was ashamed and afraid to be part of the public narrative."[85] In a statement provided to The Times, he said: "I was underage when the event took place, and I tried to seek justice in a way that made sense to me at the time because I was not ready to deal with the ramifications of my story becoming public. At the time I believed there was still a stigma to being in the situation as a male in our society. I didn't think that people would understand the event that took place from the eyes of a teenage boy." Bennett said he would like to "move past this event in my life," adding, "today I choose to move forward, no longer in silence."[85] Argento, who quietly arranged a $380,000 nondisclosure settlement with Bennett in the months following her revelations regarding Weinstein, has denied the allegations.[86] Rose McGowan initially expressed support for Argento and implored others to show restraint, tweeting, "None of us know the truth of the situation and I'm sure more will be revealed. Be gentle." As a vocal advocate of the Me Too movement, McGowan faced criticism on social media for her comments, which conflicted with the movement's message of believing survivors.[87] MeToo founder Tarana Burke responded to the Asia Argento report, stating "I've said repeatedly that the #metooMVMT is for all of us, including these brave young men who are now coming forward. Sexual violence is about power and privilege. That doesn't change if the perpetrator is your favorite actress, activist or professor of any gender."[3]

Timeline[edit]

2006, Tarana Burke[edit]

Tarana Burke, a social activist and community organizer, began using the phrase "Me Too" in 2006, on the Myspace social network[4] to promote "empowerment through empathy" among women of color who have been sexually abused.[14][88][89] She was born in Bronx, NY on September 12, 1973. Growing up, she lived in poverty in a low-income family. She was raped and sexually assaulted, both as a child and a teenager. Her mother encouraged her to help others who had been through what she been through. She moved to Selma, Alabama, where she gave birth to her daughter, Kaia Burke, and raised her as a single parent. Burke, who is creating a documentary titled Me Too, has said she was inspired to use the phrase after being unable to respond to a 13-year-old girl who confided to her that she had been sexually assaulted. Burke said she later wished she had simply told the girl: "Me too".[4][28]

2015, Ambra Gutierrez[edit]

In 2015, The New York Times reported that Weinstein was questioned by police "after a 22-year-old woman accused him of touching her inappropriately."[90] The woman, Italian model Ambra Gutierrez, cooperated with the New York City Police Department (NYPD) to obtain an audio recording where Weinstein admitted to having inappropriately touched her.[91] As the police investigation progressed and became public, tabloids published negative stories about Gutierrez that portrayed her as an opportunist.[92] American Media, publisher of the National Enquirer, allegedly agreed to help suppress the allegations by Gutierrez and Rose McGowan. Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. decided not to file charges against Weinstein, citing insufficient evidence of criminal intent, against the advice of local police who considered the evidence sufficient.[93] The New York district attorney's office and the NYPD blamed each other for failing to bring charges.[93]

2017, Alyssa Milano[edit]

Following widespread exposure of accusations of predatory behavior by Harvey Weinstein, and her own blog post on the subject, on October 15, 2017, actress Alyssa Milano wrote: "If you've been sexually harassed or assaulted write 'me too' as a reply to this tweet.", and reposted the following phrase suggested by Charlotte Clymer:[94] "If all the women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote 'Me too.' as a status, we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem."[12][11] She encouraged spreading the phrase "Me Too" to attempt to draw attention to sexual assault and harassment.[5][14] The next day, October 16, 2017, Milano wrote: "I was just made aware of an earlier #MeToo movement, and the origin story is equal parts heartbreaking and inspiring", providing the link to site of Ms. Burke.[4][28][95] Milano credits her identification with the Me Too movement to experiencing sexual harassment during a concert when she was 19.[96]

Several hashtags related to sharing stories of workplace sexual harassment were used before #MeToo, including #MyHarveyWeinstein, #WhatWereYouWearing,[97] #SurvivorPrivilege,[98] and #YouOkSis.[99][100]

2022, Johnny Depp and Amber Heard[edit]

After filing for divorce from Johnny Depp in May 2016, actress Amber Heard alleged that Depp had abused her physically during their relationship.[101] Depp filed a defamation lawsuit in the UK against The Sun's publishers over a 2018 article that alleged he was a "wife beater".[102] In December 2018, Heard published an op-ed in The Washington Post, stating that she had spoken up against sexual violence and become a public figure representing domestic abuse.[103] Although she did not explicitly name Depp in the op-ed,[104] he filed a defamation lawsuit against her in Virginia. Depp lost his lawsuit in London's High Court of Justice, after a judge determined that 12 of the 14 alleged incidents of domestic violence had occurred and that Heard's allegations of abuse were "substantially true".[105] In the Virginia trial, Depp's lawyers sought to disprove Heard's allegations before a jury, claiming that she, and not her ex-husband, had been the abuser in the relationship.[106]

The Virginia trial was livestreamed, generating enormous public interest. Social media platforms featured substantial support for Depp and criticism of Heard, with videos carrying the hashtag #JusticeForJohnnyDepp attaining over 18 billion views on TikTok by the trial's conclusion.[107] A consensus view emerged online that Heard was lying, and her testimony was widely ridiculed.[108] Ruling that her op-ed had defamed Depp with actual malice, the jury awarded him $10 million in compensatory damages and $5 million in punitive damages (the latter reduced to $350,000 under Virginia state law) while awarding Heard $2 million in compensatory damages for a counterclaim that Depp's former lawyer had defamed her.[109] During and after the trial, Depp received support from a large number of female celebrities, including Jennifer Aniston, Emma Roberts, Rita Ora, Cat Power, Patti Smith, Paris Hilton, Zoe Saldana, Kelly Osbourne, Vanessa Hudgens, Naomi Campbell, Liv Tyler, Juliette Lewis, and Ashley Benson. His former partners Winona Ryder, Kate Moss, and Vanessa Paradis provided testimony or statements during legal proceedings that Depp had never been violent or abusive to them.[110][111]

In a statement on the verdict, Heard stated: "It sets back the clock to a time when a woman who spoke up and spoke out could be publicly shamed and humiliated. It sets back the idea that violence against women is to be taken seriously."[112] Some domestic violence experts suggested that the extensive online ridicule Heard had experienced during the trial would deter women from reporting abuse.[108] Various opinion pieces from major news outlets were written either in support of Heard or against her, as well as on the trial's implications for the future of the #MeToo movement, some even declaring it the end of the movement.[113][114][115][116][117][118][119][120][121]

Impact[edit]

The New York Times found that, out of 201 prominent men who had lost their jobs after public allegations of sexual harassment, nearly half of their replacements were women.[122] Following the #MeToo movement, many men who were heads of companies were fired and many public figures began to be held accountable.[123] In addition to Hollywood, "Me Too" declarations elicited discussion of sexual harassment and abuse in the music industry,[124] sciences,[125] academia,[126] and politics.[127]

In August 2021, The Washington Post analyzed the impact of #MeToo on changing behavior. The article states there was a surge of reports of sexual assault in the twelve months preceding October 2018, but that many of the claims related to people coming forward regarding past incidents. The article shows a mixed picture regarding changing behavior with a significantly smaller percentage of women having experienced sexual coercion or unwanted sexual attention at the office in 2018 in comparison to 2016, but with a sharp rise in subtler forms of behaviors that do not rise to the level of illegal sexual harassment, such as jokes about what is still allowed or telling inappropriate stories, which may have come as a backlash to the #MeToo movement. The article notes that in response to the #MeToo movement, 19 states have enacted new sexual harassment protections for victims and more than 200 bills were introduced in state legislatures to deter harassment.[128]

Feminist author Gloria Feldt stated in Time that many employers are being forced to make changes in response to #MeToo, for example examining gender-based pay differences and improving sexual harassment policies.[129]

Astronomy[edit]

The #astroSH Twitter tag was used to discuss sexual harassment in the field of Astronomy, and several scientists and professors resigned or were fired.[130][131][132][133]

Animal advocacy[edit]

The #MeToo movement has had an impact on the field of animal advocacy. For instance, on January 30, 2018, Politico published an article titled, "Female Employees Allege Culture of Sexual Harassment at Humane Society: Two senior officials, including the CEO, have been investigated for incidents dating back over a decade."[134] The article concerned allegations against then-Humane Society of the United States CEO Wayne Pacelle and animal protection activist Paul Shapiro.[134] Mr. Pacelle soon resigned.[135] Mr. Shapiro also soon left the Humane Society of the United States.[136] Both men have nonetheless continued to hold leadership positions either in, or adjacent to, the animal protection movement.[137][138]

Churches[edit]

In November 2017, the hashtag #ChurchToo was started by Emily Joy and Hannah Paasch on Twitter and began trending in response to #MeToo as a way to try to highlight and stop sexual abuse that happens in a church.[139][140] In early January 2018, about a hundred evangelical women also launched #SilenceIsNotSpiritual to call for changes to how sexual misconduct is dealt within the church.[141][142] #ChurchToo started spreading again virally later in January 2018 in response to a live-streamed video admission by Pastor Andy Savage to his church that he sexually assaulted a 17-year-old girl twenty years before as a youth pastor while driving her home, but then received applause by his church for admitting to the incident and asking for forgiveness. Pastor Andy Savage then resigned from his staff position at Highpoint Church and stepped away from ministry.[143][144][145]

Education[edit]

The University of California has had substantial accusations of sexual harassment reported yearly in the hundreds at all nine UC campuses, notably UC Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, and San Diego.[146] However, a landmark event at the University of California, Irvine spearheaded the removal and reprimand of several campus officials and professors accused of sexual harassment and discrimination. In early July 2018, UC Irvine removed millionaire benefactor Francisco J. Ayala's name from its biology school, central science library, graduate fellowships, scholar programs, and endowed chairs after an internal investigation substantiated a number of sexual harassment claims. The results from the investigation were compiled in a 97-page report, which included testimony from victims enduring Ayala's harassment for 15 years.[147][148][149][150][151][152][153] His removal promptly sparked the removal of Professor Ron Carlson in August 2018, who had led the creative writing program at UC Irvine. He resigned after substantiated reports of sexual misconduct with an underage student were unearthed.[154] UC Irvine upon learning about the report accepted Professor Carlson's immediate resignation.[155] Several claims were also reviewed against Thomas A. Parham, former vice chancellor at UC Irvine and former president of the Association of Black Psychologists.[156]

To address harassment within scientific settings, BethAnn McLaughlin started the #MeTooSTEM movement and hashtag.[157] She called for the National Institutes of Health to cut funding to anyone who has been found guilty of harassment charges.[157][158] McLaughlin shared the MIT Media Lab Disobedience Award with Tarana Burke and Sherry Marts for her work on Me Too in STEM.[159][160]

Finance[edit]

There has been pressure on companies, specifically in the financial industry, to disclose diversity statistics.[161] It has been noted that, although the financial industry is known to have a wide prevalence of sexual harassment,[162] as of January 2018, there were no high-profile financial executives stepping down as the result of #MeToo allegations.[163] The first widely covered example of concrete consequences in finance was when two reporters, including Madison Marriage of the Financial Times, went undercover at a men-only Presidents Club event meant to raise money for children. Because women were not allowed to attend except as "hostesses" in tight, short black dresses with black underwear, Financial Times reporter Madison Marriage and another reporter got jobs as hostesses and documented widespread sexual misconduct. As a result, The Presidents Club was shut down.[163]

In March 2018, Morgan Stanley broker, Douglas E. Greenberg, was put on administrative leave after a New York Times story outlined harassment allegations by four women, including multiple arrests for the violation of restraining orders, and a threat to burn down an ex-girlfriend's house. It has been called the #MeToo moment of Portland's financial service industry.[164]

The authors of a December 2018 Bloomberg News article on this topic interviewed more than thirty senior Wall Street executives and found that many are now more cautious about mentoring up and coming female executives because of the perceived risks involved. One said, "If men avoid working or traveling with women alone, or stop mentoring women for fear of being accused of sexual harassment, those men are going to back out of a sexual harassment complaint and right into a sex discrimination complaint."[165]

Hollywood[edit]

The phrase "Me too" was tweeted by Milano on October 15, 2017, and had been used more than 200,000 times by the end of the day.[166] It was also tweeted more than 500,000 times by October 16 and the hashtag was used by more than 4.7 million people in 12 million posts during the first 24 hours on Facebook.[167][28] The platform reported 45% of users in the United States had a friend who had posted using the term.[168] Tens of thousands of people, including hundreds of celebrities, replied with #MeToo stories.[169] Some men, such as actors Terry Crews[170] and James Van Der Beek,[171] have responded to the hashtag with their own experiences of harassment and abuse. Others have responded by acknowledging past behaviors against women, spawning the hashtag #HowIWillChange.[172]

Filmmaker, feminist activist, and member of the Directors Guild of America, Maria Giese realized that the "virtual absence of women directors in Hollywood was tantamount to the censoring and silencing of female voices in US media—America's most influential global export."[173] She took her findings to the ACLU of Southern California, which prompted an official investigation into Hollywood's job discrimination.[174] Shortly after, the New York Times published its 2017 article "that triggered the MeToo movement", exposing Harvey Weinstein of sexual harassment and assault. "'It was explosive,' says Giese, 'and suddenly our industry was throwing millions of dollars into the creation of new inside-industry enforcement organinzations like Time's Up, The Hollywood Commission, ReFrame, and many others.'"[175]

In February 2019 actress Emma Thompson wrote a letter to the American production company Skydance Media, to explain that she had pulled out of the production of the animated feature film Luck the month prior because of the company's decision to hire Disney Chief Creative Officer, John Lasseter,[176] who had been accused of harassing women while at Disney. His behavior resulted in his decision to take a six-month leave of absence from the company, as he indicated in a memo in which he acknowledged "painful" conversations and unspecified "missteps".[177] Among others, Thompson stated: "If a man has been touching women inappropriately for decades, why would a woman want to work for him if the only reason he's not touching them inappropriately now is that it says in his contract that he must behave 'professionally'?"[176]

The 2019 rerelease of Toy Story 2 had a blooper scene during the credits removed due to sexual misconduct concerns.[178] Story board artists and animators at Nickelodeon and Cartoon Brew also went public with sexual harassment stories, resulting in the firing of Chris Savino. Savino was also kicked out of the The Animation Guild, IATSE Local 839.[179]

Politics and government[edit]

Statehouses in California, Illinois, Oregon, and Rhode Island responded to allegations of sexual harassment surfaced by the campaign,[180] and several women in politics spoke out about their experiences of sexual harassment, including United States Senators Heidi Heitkamp, Mazie Hirono, Claire McCaskill and Elizabeth Warren.[127] Congresswoman Jackie Speier has introduced a bill aimed at making sexual harassment complaints easier to report on Capitol Hill.[181] The accusations in the world of Spanish politics have also been published in the media,[182] and a series of allegations and research on MPs and political figures of (all major British political parties) regarding sexual impropriety became a nationwide scandal in 2017; this research was undertaken in the aftermath of the Weinstein scandal and the Me Too movement.[183][184][185]

Detective Leslie Branch-Wise of the Denver Police Department spoke publicly for the first time in 2018 about experiencing sexual harassment by Denver Mayor Michael B. Hancock. The detective provided sexually suggestive text messages from Hancock sent to her while working for Hancock's security detail in 2012. After six years of keeping the secret, Detective Branch-Wise credited the Me Too movement as an inspiration to share her experience.[186]

Congressman John Conyers was the first sitting United States politician to resign in the wake of #MeToo.[187][188][189] Later in 2019, Katie Hill resigned from Congress,[190] due to an affair with a staffer after the House Ethics Committee opened an investigation into her conduct, stemming from these new rules.[191]

In October 2020, the Lord Mayor of Copenhagen, Frank Jensen, resigned after admitting that he had been harassing women for about 30 years.[192] The Danish Foreign Minister, Jeppe Kofod, was reported to police because he had intercourse with a 15-year-old girl.[193] He has admitted the affair, but it is not clear whether it was criminal.

The Me Too movement still struggles with getting laws passed in certain areas of the United States. The US government has not passed any laws for sexual harassment and abuse because Congress is holding out on it. Because no laws are not being passed, the movement stands up and continues to fight for social change. As they keep fighting, they get some changes across the US.[194] In some states, there has been banning of nondisclosure agreements because of the situation with Harvey Weinstein. He kept his assistant from speaking out for 20 years because of the nondisclosure agreement that Weinstein made him sign. So this banning has been enforced in states such as California, New Jersey, and New York. There have been cases where the victims have been paid for their traumas. An example would be the case with Larry Nassar, who used to be the doctor for the USA Gymnastics team. Nassar was sent to jail for 40 and 175 years for sexually assaulting more than 100 gymnasts on the team.

A 2021 study in the American Journal of Political Science found that supporters of the Me Too movement were far more even-handed when evaluating accusations of sexual misconduct in U.S. politics. Whereas partisans tended to be more likely to view accused out-party members as guilty of sexual misconduct than members of their party, Me Too supporters did not show similar degrees of favoritism towards their co-partisans.[195]

On November 2, 2021, professional tennis player Peng Shuai accused Zhang Gaoli of sexual assault. Gaoli is a former Vice Premier of the People's Republic of China and a retired Chinese Communist Party official.[196]

ME TOO bill in U.S. Congress[edit]

Jackie Speier proposed the Member and Employee Training and Oversight on Congress Act (ME TOO Congress Act) on November 15, 2017.[197] The full language of the bipartisan bill was revealed by the House on January 18, 2018, as an amendment to the Congressional Accountability Act of 1995.[198] The purpose of the bill is to change how the legislative branch of the U.S. federal government treats sexual harassment complaints. Under the old system, complaints regarding the legislative branch were channeled through the Office of Compliance, which required complete confidentially through the process and took months of counseling and mediation before a complaint could be filed. Any settlement payments were paid using federal taxes, and it was reported that within a decade, $15 million of tax money had been spent settling harassment and discrimination complaints. The bill would ensure future complaints could only take up to 180 days to be filed. The bill would also allow the staffers to transfer to a different department or otherwise work away from the presence of the alleged harasser without losing their jobs if they requested it. The bill would require Representatives and Senators to pay for their harassment settlements. The Office of Compliance would no longer be allowed to keep settlements secret and would be required to publicly publish the settlement amounts and the associated employing offices. For the first time, the same protections would also apply to unpaid workers, including pages, fellows, and interns.[199][200][201]

On Thursday, February 10, 2022, the United States Congress gave final approval to legislation that ensures that anyone who is sexually harassed at work can seek legal redress.[202]

Silicon Valley and tech[edit]

In the months preceding The New York Times story on Harvey Weinstein, Travis Kalanick (CEO of Uber at the time) came under fire for enabling a misogynistic culture at the company, and having extensive knowledge of sexual harassment complaints at the company, while failing to do anything about them.[203] After an initial blog post by a former Uber Engineer detailed her experiences at the company, more employees came out with their own stories, as documented in a follow-up article by the NY Times in late February 2017. In it, they detail how they had notified senior management including Kalanick about incidents of sexual harassment, and that their complaints had gone ignored.[204] A few months later, in June 2017, Kalanick himself came under allegations of sexual harassment, as it was reported that he visited an escort bar in Seoul, bringing fellow female employees of the company along with him.[205] One of the female employees filed a complaint to Human Resources about how she felt forced to be there, and was very uncomfortable in that environment, where women were made to wear tags with numbers on them, as if in an auction.[206] Fresh allegations of sexual harassment at the company surfaced one year later, implicating Uber's Corporate Development Executive Cameron Poetzscher. The allegations made it clear that Uber was not taking this issue seriously enough.[207]

On October 25, 2018, The New York Times released a report on the prior accussations of Andy Rubin at Google. The allegations cite that Google knew of a sexual misconduct claim against Rubin, and yet still decided to pay him a $90 million separation package at his departure from the company.[208]

In August 2021, security engineer Cher Scarlett at Apple Inc. began gathering and sharing employee stories using the hashtag #AppleToo,[209][210] though the first anonymous reports of sexual harassment, rape jokes, and discrimination were in 2016.[211] The movement continued into 2022,[212] and resulted in changes to employment contracts with regards to NDAs and laws in Washington and California.[213][214] A lawsuit was filed seeking class status in California for discrimination and sexual harassment in 2024.[215] Other corporate-based #MeToo movements followed, including #GeToo at General Electric.[216]

Sports[edit]

Soon after #MeToo started spreading in late 2017, several allegations from a 2016 Indianapolis Star article resurfaced in the gymnastic industry against former U.S. Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar of Michigan State University. Nassar was called out via #MeToo for sexually assaulting gymnasts as young as 6 years old during "treatments".[217] Rachael Denhollander was the first to call him out.[218] Though nothing was done after the initial allegations came out in 2016, after more than 150 women came forward, Nassar was effectively sentenced to life in prison. The president of Michigan State University, Lou Anna Simon, resigned in the wake of the scandal.[217] At around the same time, WNBA star Breanna Stewart publicly revealed that she had been a victim of child sexual abuse from age 9 to 11.[219] In late November 2017, Lui Lai Yiu, a hurdler from Hong Kong, recounted in a Facebook post instances of having been sexually assaulted by her male coach when she was 14, sparking off mass controversy in Hong Kong.[220] Her coach was arrested in late January 2018,[221] but acquitted in mid-November 2018.[222]

Medicine[edit]

MeToo has encouraged discussion about sexual harassment in the medical field.[65][223][224] Research had indicated that among U.S. academic medical faculty members, about 30% of women and 4% of men have reported experiencing sexual harassment, and it has been noted that medical staff who complain often receive negative consequences to their careers.[75][224] Other evidence has indicated 60% of medical trainees and students experienced harassment or discrimination during training, though most do not report the incidents.[65]

Music[edit]

Several prominent musicians have expressed support for the Me Too movement and have shared their own experiences of sexual assault and harassment. Before the Me Too Movement, in 2017, Jessie Reyez released the song "Gatekeeper" about her experience of harassment by a famous producer, Detail, describing the conversations men in power have with young women working in the music industry.[225] This song inspired female artists in the music industry to speak up against sexual harassment, contributing to the start of the Me Too movement.[226]

Actress Alyssa Milano's activism for the Me Too movement began because she was harassed at the age of 19 during a concert.[96] On October 15, 2017, she started a viral Twitter thread by tweeting "If you've been sexually harassed or assaulted write 'me too' as a reply to this tweet." Musicians such as Sheryl Crow, Christina Perri and Lady Gaga responded and contributed their own personal experiences.[227]

Amanda Palmer and songwriter Jasmine Power composed "Mr. Weinstein Will See You Now", a song that takes listeners through a story of a woman invited to the office of a man in power.[228] A music video with an all-woman crew, cast and production team was released on the anniversary of the New York Times's reporting on sexual abuse allegations against Harvey Weinstein, with profits donated to #TimesUp, a movement against sexual harassment.[229]

The band Veruca Salt used the #MeToo hashtag to air allegations of sexual harassment against James Toback,[230] and singer-songwriter Alice Glass used the hashtag to share a history of alleged sexual assault and other abuses by former Crystal Castles bandmate Ethan Kath.[231][232]

Singer-songwriter Halsey wrote a poem, "A Story Like Mine", which she delivered at a 2018 Women's March in New York City. The poem describes incidents of sexual assault and violence throughout her life, including accompanying her best friend to Planned Parenthood after she had been raped and her personal experiences of sexual assault by neighbors and boyfriends.[233]

Former Red House Painters frontman and Sun Kil Moon frontman, Mark Kozelek was accused of sexual misconduct by several women that was reported by Pitchfork in 2020 and 2021, respectively.[234][235]

Allegations against figures in the music industry[edit]

In January 2019, the Lifetime documentary Surviving R. Kelly aired, describing several women's accusations of sexual, emotional, mental, and physical abuse by singer R. Kelly. The documentary questioned the "ecosystem" that "supports and enables" powerful individuals in the music industry.[236] In February 2019, Kelly was arrested for ten alleged counts of sexual abuse against four women, three of whom were minors at the time of the incidents.[237] His former wife Andrea Kelly has also accused him of domestic violence and filed a restraining order against him in 2005.[238]

Singer Kesha has accused her former producer Dr. Luke of sexually, physically, and emotionally abusing her since the beginning of her music career.[239] Dr. Luke denied the allegations and a judge refused her request to be released from a contract with Sony Music due to the alleged abuse.[240] Kesha described her response to this experience in the song "Praying", which she performed at the 2018 Grammys. The song was seen as offering encouragement to sexual assault survivors that the world can improve.[241]

A documentary was also instrumental in publicizing accusations against the late singer Michael Jackson. Child sexual abuse allegations against Jackson were renewed after the airing of the documentary Leaving Neverland in 2019. The documentary focuses on Wade Robson and James Safechuck and their interactions with Jackson, especially the sexual interactions they say they endured for years during their childhood.[242] Both had previously testified in Jackson's defense—Safechuck as a child during the 1993 investigation, Robson both as a child in 1993 and as a young adult in 2005.[243][244] In 2015, Robson's case against Jackson's estate was dismissed because it was filed too late.[245][246][247] The documentary resulted in a backlash against Jackson and a reassessment of his legacy in some quarters, while other viewers dismissed it as one-sided, questioned its veracity and viewed it as unconvincing due to factual conflicts between the film and the 1993 and 2005 allegations against Jackson, and his acquittal at trial.[248]

In 2020, it was revealed that rape allegations were made against former Recording Academy President, Neil Portnow.[249]

The MeToo movement has led to a re-examination of allegations and stories about rock and roll stars in the 1970s and 1980s when the abuse of underage groupies was tolerated and even normalized. These include the allegations made by Lori Mattix against David Bowie and Jimmy Page.[250]

Removal of music[edit]

In November 2018, WDOK Star 102, a radio station in Cleveland, Ohio, announced they removed the song "Baby, It's Cold Outside" from their playlist because listeners felt that the lyrics were inappropriate.[251] The station's host commented "in a world where #MeToo has finally given women the voice they deserve, the song has no place".[252]

The streaming service Spotify removed music by XXXTentacion and R. Kelly from Spotify-curated playlists after allegations of "hateful conduct",[226][253] but later returned the music after getting rid of their hateful conduct policy.[254]

Social justice and journalism[edit]

Sarah Lyons wrote "Hands Off Pants On", in which she explained the importance of allowing an open space for victims of sexual assault in the work place to heal.[255] Sarah Jaffe analyzed the issues facing victims who follow through with police departments and the court system.[256]

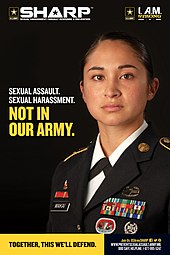

Military[edit]

In the wake of #MeToo, #MeTooMilitary came to be used by service men and women who were sexually assaulted or harassed while in the military,[257] appearing on social media in January 2018 the day after remarks by Oprah Winfrey at the Golden Globe Awards honoring female soldiers in the military "whose names we'll never know" who have suffered sexual assault and abuse to make things better for women today.[258]

A report from the Pentagon indicated that 15,000 members of the military reported being sexually assaulted in the year 2016 and only 1 out of 3 people assaulted actually made a report.[259] Veteran Nichole Bowen-Crawford has said the rates have improved over the last decade, but the military still has a long way to go, and recommends that women veterans connect privately on social media to discuss sexual abuse in a safe environment.[258][260]

There was a "#MeTooMilitary Stand Down" protest, organized by Service Women's Action Network, which gathered at the Pentagon on January 8, 2018. The protest was endorsed by the U.S. Department of Defense, who stated that current service members were welcome to attend as long as they did not wear their uniform.[261][262][263] The protest supported the Military Justice Improvement Act, sponsored by Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, which would move "the decision over whether to prosecute serious [sex] crimes to independent, trained, professional military prosecutors, while leaving uniquely military crimes within the chain of command".[262]

Pornography[edit]

There have been discussions about how pornography is related to the emergence of the #MeToo movement, and what changes, if any, should be made to the porn industry in response.[264][265] The deaths of five female porn actresses during the first three months of 2018 inspired demands that workers in the industry be included as part of the #MeToo movement.[266] It has been pointed out that many women and men have been sexually assaulted on set.[267] Some high-profile pornographic performers have been accused of assault since the emergence of #MeToo, including James Deen and Ron Jeremy.[266][268][269] The porn industry has overall been publicly supportive of #MeToo, with the topics of harassment and bodily autonomy being addressed at the 2018 AVN Awards.[270] There have been calls for the industry to police itself better in the wake of #MeToo.[267] However, when gay actor Tegan Zayne accused fellow actor Topher DiMaggio of rape in a #MeToo post, and four other men came forward with their own allegations of sexual misconduct against DiMaggio, very little happened and there was no official investigation.[271]

Several groups of Christians, conservative women, and radical feminists have argued that #MeToo demonstrates pornography causes women to be viewed as sexual objects and contributes to the prevalence of sexual harassment. As a result, these groups believe the production and consumption of pornography should be greatly restricted or made illegal.[264]

Others have pointed out that porn consumption in the U.S. is ballooning while rates of sexual violence and rape have been falling since the anti-pornography movement in the U.S. first emerged during the 1960s.[264] Additionally, some commenters have stated that laws which make pornography illegal only further restrict women's bodily autonomy.[264]

Lucia Graves stated in The Guardian that pornography can be empowering or enjoyable for women and depicting female sexuality is not always objectification.[264][272] Award-winning porn actress and director Angela White says there is a "large positive shift within the industry" to more women directing and producing their own content and "to represent women as powerful sexual beings."[266] Anti-porn activist Melissa Farley has said this ignores the "choicelessness" faced by many actresses in porn.[264] Liberal advocates argue that anti-pornography movements in the U.S. have historically never tried to increase choices for vulnerable adult performers, and taking away a person's right to act in porn may hurt them economically by reducing their choices. Many adult performers have stated that the social stigma surrounding their type of work is already a major barrier to seeking help, and making porn illegal would leave them few options if they are suffering from sexual abuse.[266]

As a result of #MeToo, many adult performers, sex worker advocates and feminists have called for greater protections for pornographic actresses, for example reducing social stigmas, mandating training courses that teach performers their rights, and providing access to independent hotlines where performers can report abuse. They argue that making porn illegal would only cause the production of porn to go underground where there are even fewer options for help. Some liberal activists have argued to compromise by raising the legal age of entry into adult entertainment from 18 to 21, which would prevent some of the most vulnerable women from being taken advantage of, while allowing adult women to still do what they want with their own bodies.[266]

Some have pointed out that many young people who do not receive a sex education adopt ideas about sex and sexual roles from pornography, whose fantasy depictions of those behaviors are not accurate to life, as they are designed for purposes of adult entertainment, and not educating the public on the reality of sexual behavior.[273] Some areas of the United States teach birth-control methods only by abstinence from sex. In a 2015 article for the American Journal of Nursing David Carter noted that a study found that abstinence-based education was "correlated with increases in teenage pregnancies and births". Multiple people have voiced support for comprehensive sex education programs that encompass a wide range topics, which they state leave children more informed.[274] Several feminists have argued it is crucial to provide children with basic sex education before they are inevitably exposed to porn. Sex education can also effectively prepare children to identify and say no to unwanted sexual contact before it occurs, and gives parents an opportunity to teach children about consent.[275]

Video games[edit]

In 2018, The Guardian reported that after the revelations about Weinstein, many women received solicitation emails hoping to uncover similar issues and spark the video games industry's #MeToo movement. This was in part due to the industry's notoriety for gender-based issues and toxicity in the gaming industry. In 2017, misconduct-related issues at IGN and Polygon resulted in two firings. In 2014, Gamergate targeted women in video games journalism with harassment under the guise of journalism ethics and standards.[276]

In 2019, women across the video game industry came forward about cultures of sexual harassment and instances of sexual assault.[277][278] Employees walked out of Riot Games demanding the removal of forced arbitration clauses from employment contracts after allegations of sexist and hostile working environment including the mishandling of sexual misconduct complaints.[279] Riot was ordered to pay $100 million to settle a class action lawsuit due to gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment.[280]

In 2020, more than 100 women came forward alleging sexual harassment and assault by various Twitch streamers. Women in Esports also came forward with complaints.[281][282]

Between 2020 and 2021, women accused Ubisoft of allowing management and its human resources (HR) department to ignore sexual misconduct towards women employees for many years.[283][281][284]

Blizzard Entertainment[edit]

In 2021, women at Activision Blizzard filed two anti-discrimination and sexual harassment lawsuits against the company, one with the California Civil Rights Department (CRD)[285] and one with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).[286] The complaint described a "frat boy" culture at Irvine-based Blizzard Entertainment (Blizzard) involving male employees, including executives, engaging in "blatant sexual harassment without repercussions," sexual assualt, and rape.[287] In response to the lawsuit in California, CEO Bobby Kotick[288] made a public statement claiming the lawsuit distorted or falsified Blizzard's past, claiming the lawsuit to be "irresponsible behavior" from "unnacountable State bureaucrats."[289] Employees responded with a petition denouncing the response[290] and several female employees wrote about their own experiences on Twitter, including software engineer Cher Scarlett, who described sexual harassment at Blizzard, named Ben Kilgore as the unnamed CTO in the lawsuit, and shared an incident of revenge porn that she said the company mishandled.[291][292][293] Kotaku followed up with women who had gone public with their experiences to give them credit for the work they had done aside from calling out sexual misconduct.[294]

The judge in the EEOC case ordered Blizzard pay $18 million to victims[295] and the CRD ordered $54 million be paid to victims, stating they could find no wide-spread sexual harassment across Santa Monica-based Activision Blizzard,[296] which is a holding company made up of Blizzard, Activision Publishing, King, Major League Gaming, and Activision Blizzard Studios.[297] In Februray 2023, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) fined Activision Blizzard $35 million for failure to maintain adequate procedures for employee misconduct complaints and for violating a whistleblower law by requiring employees to notify the company if they receive a request for information from an investigative body like the SEC or the National Labor Relations Board.[298]

The allegations of the culture at Blizzard were corroborated through investigative journalism by Bloomberg,[287] The Washington Post,[299] Fortune,[291] The Wall Street Journal,[300] The New York Times,[301] Time,[302] and The Guardian.[303]

Financial support[edit]

In May 2018, The New York Women's Foundation announced their Fund to Support the Me Too Movement and Allies, a $25 million commitment over the next five years to provide funding and support survivors of sexual violence.[304]

In September 2018, CBS announced that it would be donating $20 million of former Chairman Les Moonves' severance to #MeToo. Moonves was forced to step down after numerous sexual misconduct accusations.[305][306]

International response[edit]

The hashtag has trended in at least 85 countries.[308] Direct translations of #MeToo have been shared by Spanish speakers in South America and Europe and by Arabic speakers in Africa and the Middle East, while activists in France and Italy have developed hashtags to express the attitudes of the movement.[309] Communicating similar experiences and "sharing feelings in some form of togetherness" connects people and can lead to "formation of a process of collective action" (Castells).[310][311] The campaign has prompted survivors from around the world to share their stories, and name their perpetrators. The European Parliament convened a session directly in response to the Me Too campaign, after it gave rise to allegations of abuse in Parliament and in the European Union's offices in Brussels. Cecilia Malmström, the European Commissioner for Trade, specifically cited the hashtag as the reason the meeting had been convened.[312]

#HimToo[edit]

The related hashtag #HimToo emerged in popularity with the #MeToo movement. Although dating back to at least 2015, and initially associated with politics or casual communication, #HimToo took on new meanings associated with #MeToo in 2017, with some using it to emphasize male victims of sexual harassment and abuse, and others using it to emphasize male perpetrators. In September and October 2018, during the sexual assault allegations raised during Brett Kavanaugh's nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court, #HimToo became used by supporters of Kavanaugh and to highlight male victims of false accusations.[313][314] The latter usage was criticized for perpetuating the myth that false allegations are more common than sexual assaults.[315]

Criticism[edit]

False accusations[edit]

There has been discussion about the extent to which accusers should be believed before fact-checking. Some have questioned whether the accused are being punished without any due process establishing their guilt.[316][317][318] Many commentators have responded that the number of false reports make up a small percentage of total reports, citing figures obtained by the U.S. Department of Justice and other organizations that have generally found that around 2–10% of rape and sexual assault allegations reported to police are determined to be false after a thorough investigation; however, the 2–10% does not include cases in which it cannot be established if the accused is innocent or guilty, nor does it include allegations that are never reported to law enforcement.[319][320]

A February 2005 study by the UK Home Office that compiled data on 2,284 reported rape cases found that from a set of 216 rape cases later found to be false, only six led to arrests and only two involved charges being filed.[321][322][323] Elle writer Jude Doyle commented that another hashtag, #BelieveWomen, was not a threat to due process but a commitment to "recognize that false allegations are less common than real ones".[323] Jennifer Wright of Harper's Bazaar proposed a similar definition of #BelieveWomen and pointed out The Washington Post's ability to quickly identify a false accusation set up by Project Veritas. She also stated that only 52 rape convictions being overturned in the United States since 1989, as opposed to 790 for murder, was strong evidence that at least 90% of rape allegations are true.[322][324] Michelle Malkin expressed a suspicion that many stories in the #MeToo movement would be exaggerated and accused news outlets of focusing on "hashtag trends spread by celebrities, anonymous claimants and bots".[325]

On November 30, 2017, Ijeoma Oluo revealed the contents of a request she received from USA Today, asking her to write a piece arguing that due process is unnecessary for sexual harassment allegations. She refused, saying "of course I believe in due process" and wrote that it was disingenuous for the paper to ask her "to be their strawman".[326]

During their 2001 divorce, model Donya Fiorentino accused actor Gary Oldman of perpetrating a domestic assault—something he maintains never took place.[327] Following an extended investigation, Oldman was cleared of wrongdoing and awarded sole legal and physical child custody;[328][329] Fiorentino received limited, state-supervised contact dependent on her passing drug and alcohol tests.[328][330] In early 2018, however, Fiorentino was granted media interviews in which to revive the assault allegation while referring to the MeToo movement.[327][328] Her commentary coincided with Oldman's Best Actor win at the 90th Academy Awards (for his performance in 2017's Darkest Hour), which was condemned by Twitter users and described by reporters as "disappointing",[331] "a referendum on the structure of Hollywood",[332] and indicative of "how much Hollywood really cares about purging the industry's toxic men".[333] Fiorentino and Oldman's son, Gulliver, lambasted "so-called 'journalists'" for perpetuating a claim that was "discredited as false years ago". He expressed trepidation about defending an accused male in the face of MeToo, saying, "I can see how coming out with a statement to combat an allegation must look. However, I was there at the time of the 'incident'."[334] Oldman's representative pointed to the 2001 courtroom outcome, accused Fiorentino of using MeToo as "convenient cover to further a personal vendetta", and requested that the press not allow the movement to be "misused as an instrument of harm to decent people by people with very bad intentions".[327][335]

On September 21, 2018, President Donald Trump claimed Christine Blasey Ford was making up her accusations against now Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, Brett Kavanaugh, saying that if her story was true she would have filed a report against him when it had happened. This is a common argument against the MeToo movement and alleged sexual assault victims alike.[336] On October 11, 2018, First Lady Melania Trump said that women who make accusations of sexual abuse against men should back their claims with solid evidence.[337]

Undefined purpose[edit]

There has been discussion about whether the movement is meant to inspire change in all men or just a percentage of them, and what specific actions are the end goal of the movement.[338] Other women have stated #MeToo should examine only the worst types of abuse in order to prevent casting all men as perpetrators, or causing people to become numb to the problem.[316][338]

Creator Tarana Burke has laid out specific goals for the #MeToo movement, including: processing all untested rape kits in the United States, investigating the vetting of teachers, better protecting children at school, updating sexual harassment policies, and improving training in workplaces, places of worship, and schools. She has stated that everyone in a community, including men and women, must act to make the #MeToo movement a success. She also supports the #MeToo Congress bill and hopes it will inspire similar legal changes in other parts of the country.[22]

Samantha Geimer, the victim of rape by film director Roman Polanski, said that "when it's used as a weapon to attack famous people or harm and demonize certain people I don't think that's ever what #MeToo was meant for and it's become kind of toxic and lost its value".[339]

Overcorrection[edit]

Richard Ackland described the response to defamation cases "an asphyxiating vortex of litigation".[340]

There has been discussion on whether harsh consequences are warranted for particular examples of alleged misconduct.[316][317][318] An especially divisive story broke on Babe.net on January 13, 2018, when an anonymous accuser detailed the events of her date with Aziz Ansari and referred to what transpired as "sexual assault". Jill Filipovic wrote for The Guardian that "it was only a matter of time before a publication did us the disservice of publishing a sensational story of a badly behaved man who was nonetheless not a sexual assailant".[341][342][343] James Hamblin wrote for The Atlantic that, instead, these "stories of gray areas are exactly what ... need to be told and discussed."[344]

Some actors have admonished proponents of the movement for not distinguishing between different degrees of sexual misconduct. Matt Damon commented on the phenomenon in an interview, and later apologized, saying "the clearer signal to men and to younger people is, deny it. Because if you take responsibility for what you did, your life's going to get ruined."[345] Subsequently, Liam Neeson opined that some accused men, including Garrison Keillor and Dustin Hoffman, had been treated unfairly.[20]

Tarana Burke said in January 2018, "Those of us who do this work know that backlash is inevitable." While describing the backlash as carrying an underlying sentiment of fairness, she defended her movement as "not a witch hunt as people try to paint it". She stated that engaging with the cultural critique in #MeToo was more productive than calling for it to end or focusing on accused men who "haven't actually touched anybody".[19] Ronan Farrow, who published the Weinstein exposé in the New Yorker that helped start the #MeToo resurgence (alongside New York Times reporters Megan Twohey and Jodi Kantor), was asked in late December 2017 whether he thought the movement had "gone too far". Farrow called for a careful examination of each story to guard against false accusations but also recalled the alleged sexual abuse his sister Dylan Farrow claims she went through at the hands of his father Woody Allen. He stated that after decades of silence, "My feeling is that this is a net benefit to society and that all of the people, men, and women, pouring forward and saying 'me too' deserve this moment. I think you're right to say that we all have to be conscious of the risk of the pendulum swinging too far, but in general this is a very positive step."[21]

Ijeoma Oluo spoke about how some Democrats have expressed regret over the resignation of Senator Al Franken due to allegations of sexual misconduct. She sympathized with them but stressed the importance of punishing misconduct regardless of whether the perpetrator is viewed as "a bad guy" overall. She wrote that "most abusers are more like Al Franken than Harvey Weinstein".[346] The New York Times has called this discussion the "Louis C.K. Conundrum", referring to the admission by comedian Louis C.K. that he committed sexual misconduct with five women, and the subsequent debate over whether any guilt should be associated with enjoyment of his work.[347][348][349] Jennifer Wright of Harper's Bazaar has said that public fears of an overcorrection reflect the difficulty of accepting that "likeable men can abuse women too".[324]

A 2019 LeanIn.Org/SurveyMonkey survey showed that 60 percent of male managers reported being "too nervous" of being accused of harassment when mentoring, socializing, or having one-on-one meetings with women in the workplace.[350][351] A 2019 study in the journal Organizational Dynamics, published by Elsevier, found that men are significantly more reluctant to interact with their female colleagues. Examples include 27 percent of men avoid one-on-one meetings with female co-workers, 21 percent of men said they would be reluctant to hire women for a job that would require close interaction (such as business travel), and 19 percent of men being reluctant to hire an attractive woman.[352][353]

Possible trauma to victims[edit]

The hashtag has been criticized for putting the responsibility of publicizing sexual harassment and abuse on those who experienced it, which could be re-traumatizing.[354][355][356] The hashtag has been criticized as inspiring fatigue and outrage, rather than emotionally dense communication.[357][358]

Exclusion of sex workers[edit]

There have been many calls for the #MeToo movement to include sex workers and sex trafficking victims.[359][360][361][362] Although these women experience a higher rate of sexual harassment and assault than any other group of people, they are often seen in society as legitimate targets that deserve such acts against them.[363] Autumn Burris stated that prostitution is like "#MeToo on steroids" because the sexual harassment and assault described in #MeToo stories are frequent for women in prostitution.[359] Melissa Farley argues that prostitution, even when consensual, can be a form of sexual assault, as it can be for money for food or similar items, thus, at least according to Farley, making prostitution a forced lifestyle relying on coercions for food.[363] Many sex workers disagree with her stance, saying that she stigmatizes prostitution.[364] According to Ashwini Tambe, the definition of coercion shouldn't only be determined on person decision to say yes or no. Instead, it should also be determined whether one person has control or influence over the other person. She also states that one might decipher whether such a request is a certain threat or force. That's why she states that transacting in sex or exchanging sex for something means that coercion is still in the picture even if its consensual.[365]

American journalist Steven Thrasher noted that, "There has been worry that the #MeToo movement could lead to a sex panic. But the real sex panic is not due to feminism run amok, but due to the patriarchal, homophobic, transantagonistic, theocratic desire of the US Congress to control sex workers." He points to the 2018 Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA), which many experts say will only put sex workers at further risk by causing them to go underground, does not offer sex workers any help or protections, and as a side effect prevents most people from using online personal ads regardless of their intentions.[366]

British filmmaker Bizhan Tong, a figure involved in various gender equality initiatives, wrote, directed, and self-funded the feature film The Escort[367] after conducting a series of interviews with current and former sex workers in a direct attempt to lend a platform for their voices to be heard.[368] The film was shot in 2017 and completed in 2018, premiered in New York in August that year, and received several awards across the globe.[369] It is currently being adapted for the stage.

Failure to address police misconduct[edit]

Despite the prevalence of sexual misconduct, some have pointed out the lack of discussion in the #MeToo movement regarding law-enforcement misconduct.[370][371][372][373]

Police sexual misconduct disproportionately affects women of color, though women from all races are affected.[373] The Cato Institute reported that in 2010, more than 9% of police misconduct reports in 2010 involved sexual abuse, and there are multiple indications that "sexual assault rates are significantly higher for police when compared to the general population."[371] Fear of retribution is considered[by whom?] one reason some law-enforcement officers are not subjected to significant consequences for known misconduct.[370] Police-reform activist Roger Goldman stated that an officer who is fired for sexual misconduct from one police department often gets rehired by a different department, where they can continue the misconduct in a new environment.[370] Some states (such as Florida and Georgia) have licensing laws that can decertify a law-enforcement officer who has committed major misconduct, which prevents decertified officers from being hired again in that state.[370] Some have called for sexual misconduct allegations against police to be investigated by third parties to reduce bias (as opposed to the common practice of investigations being led by fellow law-enforcement officers or colleagues in the same department).[373]

Lack of representation of minority women[edit]

Many have pointed to a lack of representation of minority women in the #MeToo movement or its leadership.[374][375][376][377][378][379] Most historical feminist movements have contained active elements of racism, and have typically ignored the needs of non-white women[380] even though minority women are more likely to be targets of sexual harassment.[374][375][376][377][378]

Minority women are overrepresented in industries with the greatest number of sexual harassment claims, for example hotels, health, food services, and retail.[376] It has been pointed out that undocumented minority women often have no recourse if they are experiencing sexual violence.[381] Activist Charlene Carruthers said, "If wealthy, highly visible women in news and entertainment are sexually harassed, assaulted and raped—what do we think is happening to women in retail, food service and domestic work?"[376]

Survivor Farah Tanis stated there are also additional barriers for black women who want to participate in the #MeToo movement. She pointed out that social pressure discourages reports against black men, especially from church and family, because many would view that as a betrayal against their "brothers".[381] Additionally, black women are less likely to be believed if they do speak out.[381]