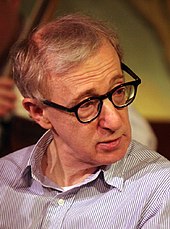

Вуди Аллен

Вуди Аллен | |

|---|---|

Всего в 2016 году | |

| Рожденный | Аллан Стюарт Кенигсберг 30 ноября 1935 г. [а] Нью-Йорк , США |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1956–present |

| Works | Full list |

| Spouses |

|

| Partners |

|

| Children | 5, including Ronan Farrow and Moses Farrow |

| Relatives | Letty Aronson (sister) |

| Awards | Full list |

| Website | www |

Хейвуд Аллен (родился Аллан Стюарт Кенигсберг ; 30 ноября 1935 г.) [а] — американский кинорежиссер, актер и комик, чья карьера насчитывает более шести десятилетий. Аллен получил множество наград , в том числе наибольшее количество номинаций (16) на премию «Оскар» за лучший оригинальный сценарий . Он выиграл четыре премии «Оскар» , десять премий BAFTA , две премии «Золотой глобус» и премию «Грэмми» , а также номинировался на премии «Эмми» и « Тони» . [14] Аллен был награжден Почетным Золотым львом в 1995 году, стипендией BAFTA в 1997 году, Почетной пальмовой ветвью в 2002 году и премией Сесила Б. Демилля «Золотой глобус» Два его фильма были внесены в Национальный реестр фильмов в 2014 году . Библиотека Конгресса .

Allen began his career writing material for television in the 1950s, alongside Mel Brooks, Carl Reiner, Larry Gelbart, and Neil Simon. He also published several books of short stories and wrote humor pieces for The New Yorker. In the early 1960s, he performed as a stand-up comedian in Greenwich Village, where he developed a monologue style (rather than traditional jokes) and the persona of an insecure, intellectual, fretful nebbish.[15] During this time, he released three comedy albums, earning a Grammy Award for Best Comedy Album nomination for the self-titled Woody Allen (1964).[16]

After writing, directing, and starring in a string of slapstick comedies, such as Take the Money and Run (1969), Bananas (1971), Sleeper (1973), and Love and Death (1975), he directed his most successful film, Annie Hall (1977), a romantic comedy-drama featuring Allen and his frequent collaborator Diane Keaton. The film won four Academy Awards, for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Actress for Keaton.[17] Allen has directed many films set in New York City, including Manhattan (1979), Hannah and Her Sisters (1986), and Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989).

Allen continued to garner acclaim, making a film almost every year, and is often identified as part of the New Hollywood wave of auteur filmmakers whose work has been influenced by European art cinema.[18] His films include Interiors (1978), Stardust Memories (1980), Zelig (1983), Broadway Danny Rose (1984), The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985), Radio Days (1987), Husbands and Wives (1992), Bullets Over Broadway (1994), Deconstructing Harry (1997), Match Point (2005), Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008), Midnight in Paris (2011), and Blue Jasmine (2013).[19]

In 1979, Allen began a professional and personal relationship with actress Mia Farrow. Over a decade-long period, they collaborated on 13 films. The couple separated after Allen began a relationship in 1991 with Mia's and Andre Previn's adopted daughter Soon-Yi Previn. Allen married Previn in 1997. They have two adopted daughters.[20] In 1992, Farrow publicly accused Allen of sexually abusing their adopted daughter, Dylan Farrow.[21][22] The allegation gained substantial media attention, but Allen was never charged or prosecuted, and vehemently denied the allegation.

Early life and education

Allen was born Allan Stewart Konigsberg[23] at Mount Eden Hospital in Bronx, New York City, on November 30, 1935,[a][24][25] to Nettie (née Cherry; 1906–2002), a bookkeeper at her family's delicatessen, and Martin Konigsberg (1900–2001),[26] a jewelry engraver and waiter.[27] His grandparents were immigrants to the U.S. from Austria and Panevėžys, Lithuania. They spoke German, Hebrew, and Yiddish.[28][29] He and his younger sister, film producer Letty, were raised in the Midwood neighborhood of Brooklyn. He is Jewish.[30] Both their parents were born and raised on the Lower East Side of Manhattan.[31]

Allen's parents did not get along, and he had an estranged relationship with his mother.[32] He spoke German in his early years.[citation needed] While attending Hebrew school for eight years, he also attended Public School 99, now the Isaac Asimov School for Science and Literature,[33] and then Midwood High School, from which he graduated in 1953. Unlike his comic persona, he was more interested in baseball than school and was picked first for teams.[34][23] He impressed students with his talent for cards and magic tricks.[35]

At age 17, he legally changed his name to Heywood Allen[36] and later began to call himself Woody.[37] According to Allen, his first published joke read: "Woody Allen says he ate at a restaurant that had O.P.S. prices—over people's salaries."[38] He was soon earning more than both of his parents combined.[34] After high school, he attended New York University, studying communication and film in 1953, before dropping out after failing the course "Motion Picture Production". He briefly attended City College of New York in 1954, dropping out during his first semester.[39] He taught himself rather than studying in the classroom.[23] He later taught at The New School and studied with writing teacher Lajos Egri.[40]

Career

Note: For a list of Allen's films, see Woody Allen filmography.

1955–1959: Comedy writer and television work

Allen began writing short jokes when he was 15,[41] and the next year began offering them to various Broadway writers for sale.: 539 One of them, Abe Burrows, co-author of Guys and Dolls, wrote, "Wow! His stuff was dazzling." Burrows wrote Allen letters of introduction to Sid Caesar, Phil Silvers, and Peter Lind Hayes, who immediately sent Allen a check for just the jokes Burrows included as samples.[42] As a result of the jokes Allen mailed to various writers, he was invited, then age 19, to join the NBC Writer's Development Program in 1955, followed by a job on The NBC Comedy Hour in Los Angeles, then a job as a full-time writer for humorist Herb Shriner, initially earning $25 a week.[38] He began writing scripts for The Ed Sullivan Show, The Tonight Show, specials for Sid Caesar post-Caesar's Hour (1954–1957), and other television shows.[43] By the time he was working for Caesar, he was earning $1,500 a week. He worked alongside Mel Brooks, Carl Reiner, Larry Gelbart, and Neil Simon. He also worked with Danny Simon, whom Allen credits for helping form his writing style.[38][44] In 2021, Brooks said of working with Allen, "Woody was so young then. I was about 24 when I started, but Woody must have been 19, but so wise, so smart. He had this tricky little mind and he'd surprise you, which is the trick of being a good comedy writer."[45] In 1962 alone, he estimated that he wrote twenty thousand jokes for various comics.[46] Allen also wrote for Candid Camera and appeared in several episodes.[47]

He wrote jokes for the Buddy Hackett sitcom Stanley and The Pat Boone Chevy Showroom, and in 1958 he co-wrote a few Sid Caesar specials with Larry Gelbart.[48] Composer Mary Rodgers said he was gaining a reputation. When given an assignment for a show, he would leave and come back the next day with "reams of paper", according to producer Max Liebman.[48] Similarly, after he wrote for Bob Hope, Hope called him "half a genius".[48] Dick Cavett said: "He can go to a typewriter after breakfast and sit there until the sun sets and his head is pounding, interrupting work only for coffee and a brief walk, and then spend the whole evening working."[49] Allen once estimated that to prepare for a 30-minute show, he spent six months of intensive writing.[49] He enjoyed writing, despite the work: "Nothing makes me happier than to tear open a ream of paper. And I can't wait to fill it!"[49]

Allen started writing short stories and cartoon captions for magazines such as The New Yorker; he was inspired by the tradition of New Yorker humorists S. J. Perelman, George S. Kaufman, Robert Benchley, and Max Shulman, whose material he modernized.[50][51][52][53][54][55] His collections of short pieces include Getting Even, Without Feathers, Side Effects, and Mere Anarchy. In 2010 Allen released audio versions of his books in which he read 73 selections entitled, The Woody Allen Collection. He was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album.[56]

1960–1969: Stand-up comedian

From 1960 to 1969 Allen performed as a comedian in various places around Greenwich Village, including The Bitter End and Cafe Au Go Go, alongside such contemporaries as Lenny Bruce, the team of Mike Nichols and Elaine May, Joan Rivers, George Carlin, Richard Pryor, Dick Cavett, Bill Cosby and Mort Sahl (his personal favorite), as well as such other artists of the day as Bob Dylan and Barbra Streisand.[57] Comedian Milton Berle claims to have suggested to Allen to go into standup comedy and even introduced him at the Village Vanguard.[58] Comedy historian Gerald Nachman writes, "He helped turn it into biting, brutally honest satirical commentary on the cultural and psychological tenor of the times."[37]

Allen's new manager, Jack Rollins, suggested he perform his written jokes as a stand-up. "I'd never had the nerve to talk about it before. Then Mort Sahl came along with a whole new style of humor, opening up vistas for people like me."[59] Allen made his professional stage debut at the Blue Angel nightclub in Manhattan in October 1960, where comedian Shelley Berman introduced him as a young television writer who would perform his own material.[59]

In his early stand-up shows, Allen did not improvise: "I put very little premium on improvisation", he told Studs Terkel.[60] His jokes were created from life experiences, and typically presented with a dead serious demeanor that made them funnier: "I don't think my family liked me. They put a live teddy bear in my crib."[46] And although he was described as a "classic nebbish", he did not tell the standard Jewish jokes of the period.[61] Comedy screenwriter Larry Gelbart compared Allen's style to Elaine May's: "He just styled himself completely after her".[62]

Cavett recalled seeing the Blue Angel audience mostly ignore Allen's monologue: "I resented the fact that the audience was too dumb to realize what they were getting."[63] It was his subdued stage presence that eventually became one of Allen's strongest traits, Nachman argues: "The utter absence of showbiz veneer and shtick was the best shtick any comedian had ever devised. This uneasy onstage naturalness became a trademark."[64] Allen brought innovation to the comedy monologue genre.[65]

Allen first appeared on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson on November 1, 1963, and over nine years his guest appearances included 17 in the host's chair. He subsequently released three LP albums of live nightclub recordings: the self-titled Woody Allen (1964), Volume 2 (1965), and The Third Woody Allen Album (1968), recorded at a fund-raiser for Senator Eugene McCarthy's presidential run.[66] In 1965, Allen filmed a half-hour standup special in England for Granada Television, titled The Woody Allen Show in the U.K. and Woody Allen: Standup Comic in the U.S.[67] It is the only complete standup show of Allen's on film.[67] The same year, Allen, along with Nichols and May, Barbra Streisand, Carol Channing, Harry Belafonte, Julie Andrews, Carol Burnett, and Alfred Hitchcock, took part in Lyndon B. Johnson's inaugural gala in Washington, D.C., on January 18, 1965. First Lady Lady Bird Johnson described Allen and the event in her published diary, A White House Diary, writing in part, "Woody Allen, that forlorn, undernourished little comedian, stopped shooting a movie in Paris and flew across the Atlantic for about five minutes of jokes".[68]

In 1966, Allen wrote an hour-long musical comedy television special for CBS, Gene Kelly in New York City.[69] It focused on Gene Kelly in a musical tour around Manhattan, dancing along such landmarks as Rockefeller Center, the Plaza Hotel and the Museum of Modern Art, which serve as backdrops for the show's production numbers.[70] Guest stars included choreographer Gower Champion, British musical comedy star Tommy Steele, and singer Damita Jo DeBlanc.[71] In 1967, Allen hosted a TV special for NBC, Woody Allen Looks at 1967. It featured Liza Minnelli, who acted alongside Allen in some skits; Aretha Franklin, the musical guest; and conservative writer William F. Buckley, the featured guest.[72] In 1969, Allen hosted his first American special for CBS television, The Woody Allen Special, which included skits with Candice Bergen, a musical performance by the 5th Dimension, and an interview between Allen and Billy Graham.[73][74]

Allen also performed standup comedy on other series, including The Andy Williams Show and The Perry Como Show, where he interacted with other guests and occasionally sang.[citation needed] In 1971, he hosted one of his final Tonight Shows, with guests Bob Hope and James Coco.[75] Hope praised Allen on the show, calling him "one of the finest young talents in show business and a great delight".[76] Life magazine put Allen on the cover of its March 21, 1969, issue.[77]

1965–1976: Broadway debut and early films

Allen's first movie was the Charles K. Feldman production What's New Pussycat? (1965)[78] Allen was disappointed with the final product, which led him to direct every film he wrote thereafter except Play It Again, Sam.[79] Allen's first directorial effort was What's Up, Tiger Lily? (1966, co-written with Mickey Rose).[80] That same year, Allen wrote the play Don't Drink the Water, starring Lou Jacobi, Kay Medford, Anita Gillette, and Allen's future movie co-star Tony Roberts.[81] In 1994 Allen directed and starred in a second version for television, with Michael J. Fox and Mayim Bialik.[82]

The next play Allen wrote for Broadway was Play It Again, Sam, which opened on February 12, 1969, starring Allen, Diane Keaton and Roberts.[83] The play received a positive review from Clive Barnes of The New York Times, who wrote, "Not only are Mr. Allen's jokes—with their follow-ups, asides, and twists—audaciously brilliant (only Neil Simon and Elaine May can equal him in this season's theater) but he has a great sense of character".[84] The play was significant to Keaton's budding career, and she has said she was in "awe" of Allen even before auditioning for her role, which was the first time she met him.[85] In 2013, Keaton said that she "fell in love with him right away", adding, "I wanted to be his girlfriend so I did something about it."[86] For her performance she was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Featured Actress in a Play.[87] After co-starring alongside Allen in the subsequent film version of Play It Again, Sam, she acted in seven more of his films. including Sleeper, Love and Death, Annie Hall, Interiors, and Manhattan.[88] Keaton said of their collaboration: "He showed me the ropes and I followed his lead. He is the most disciplined person I know. He works very hard".[86]

In 1969, Allen directed, starred in, and co-wrote with Mickey Rose the mockumentary crime comedy Take the Money and Run, in which he plays the low-level thief Virgil Starkwell.[89] The film received positive reviews; critic Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote, "Allen has made a movie that is, in effect, a feature-length, two-reel comedy—something very special and eccentric and funny."[90] In 1971, Allen wrote and directed the slapstick comedy film Bananas, in which he plays Fielding Mellish, a bumbling New Yorker who becomes involved in a revolution in a country in Latin America. The film also starred Louise Lasser as his romantic interest.[91] In an interview with Roger Ebert, Allen said, "The big, broad laugh comedy is a form that's rarely made these days and sometimes I think it's the hardest kind of movie to make...with a comedy like Bananas, if they're not laughing, you're dead, because laughs are all you have."[92]

The next year, Allen made the film Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* (*But Were Afraid to Ask), starring Allen, Gene Wilder, Lou Jacobi, Anthony Quayle, Tony Randall, and Burt Reynolds, which received mixed reviews. Time wrote, "the jokes are well-worn, and good, manic ideas are congealing into formulas".[93] Allen reunited with Keaton in Sleeper (1973), the first of four screenplays co-written by Allen and Marshall Brickman.[94][95]

Allen collaborated again with Keaton in the comedy Love and Death (1975), set during the Napoleonic era and a satire of Russian literature and film.[79] At the time of its release, Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the film Allen's "grandest work".[96] In 1976, Allen starred as cashier Howard Prince in the Hollywood blacklist comedy-drama The Front, directed by Martin Ritt and co-starring Zero Mostel.[97]

1977–1989: Established career

I don't like meeting heroes. There's nobody I want to meet and nobody I want to work with—I'd rather work with Diane Keaton than anyone—she's absolutely great, a natural.

—Woody Allen in July 1976[41]

In 1977 Allen wrote, directed, and starred in the romantic comedy film Annie Hall, which became his seminal and most personal work.[98] He played Alvy Singer, a comic evaluating his past relationship with Annie Hall, portrayed by Diane Keaton. Critic Roger Ebert praised the film, saying Allen had "developed...into a much more thoughtful and...more mature director".[99] Vincent Canby of The New York Times praised Allen's direction, specifically citing his hiring of actors in the film such as Shelley Duvall, Paul Simon, Carol Kane, Colleen Dewhurst, and Christopher Walken.[100] In an interview with journalist Katie Couric, Keaton did not deny that Allen wrote the part for and about her.[101] The film won four Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actress in a Leading Role for Keaton, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Director for Allen.[102] It was ranked 35th on the American Film Institute's "100 Best Movies"[103] and fourth on the AFI list of the "100 Best Comedies".[104] The screenplay was also named the funniest ever written by the Writers Guild of America in its list of the "101 Funniest Screenplays".[105] In 1992, the Library of Congress selected the film for preservation in the United States National Film Registry as "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant".[106]

In 1979, Allen paid tribute at the Film Society at Lincoln Center to one of his comedy idols, Bob Hope, who said of the honor: "It's great to have your past spring up in front of your eyes, especially when it's done by Woody Allen, because he's a near genius. Not a whole genius, but a near genius".[107] With Manhattan (1979), Allen directed a comic homage to New York City, focused on the complicated relationship between middle-aged Isaac Davis (Allen) and 17-year-old Tracy (Mariel Hemingway), co-starring Keaton and Meryl Streep.[108] Keaton, who has made eight movies with Allen, has said, "He just has a mind like nobody else. He's bold. He's got a lot of strength, a lot of courage in terms of his work. And that is what it takes to do something really unique."[101]

Stardust Memories was based on 8½, which it parodies, and Wild Strawberries.[109][110] Allen's comedy A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy was adapted from Smiles of a Summer Night.[111] Hannah and Her Sisters, Another Woman and Crimes and Misdemeanors have elements reminiscent of Wild Strawberries.[112] In Stardust Memories (1980), Allen's character says, "I don't want to make funny movies anymore" and a running gag has various people (including visiting space aliens) telling him that they appreciate his films, "especially the early, funny ones".[113] Allen considers it one of his best films.[114] In 1981, Allen's play The Floating Light Bulb, starring Danny Aiello and Bea Arthur, premiered on Broadway and ran for 65 performances.[115] New York Times critic Frank Rich gave the play a mild review, writing, "there are a few laughs, a few well-wrought characters, and, in Act II, a beautifully written scene that leads to a moving final curtain".[116] Allen has written several off-Broadway one-act plays, including Riverside Drive, Old Saybrook (at the Atlantic Theater Company), and A Second Hand Memory (at the Variety Arts Theatre).[116][117]

Mia's a good actress who can play many different roles. She has a very good range, and can play serious to comic roles. She's also very photogenic, very beautiful on screen. She's just a good realistic actress ... and no matter how strange and daring it is, she does it well.

—Woody Allen (1993)[118]

A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy (1982) was the first movie Allen made with Mia Farrow, who stepped into Diane Keaton's role when Keaton was shooting Reds.[119] He next directed Zelig, in which he starred as a man whose appearance transforms to match that of those around him.[120] Radio Days, a film about his childhood in Brooklyn and the importance of the radio, co-starred Farrow in a part Allen wrote for her.[118] Time magazine called The Purple Rose of Cairo one of the 100 best films of all time.[121] Allen has called it one of his three best films, with Stardust Memories and Match Point.[122] In 1989, Allen and directors Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese made New York Stories, an anthology film about New Yorkers. Vincent Canby called Allen's contribution, Oedipus Wrecks, "priceless".[123]

1990–2004: Continued work

Allen's 1991 film Shadows and Fog is a black-and-white homage to the German expressionists and features the music of Kurt Weill.[124] Allen then made his critically acclaimed comedy-drama Husbands and Wives (1992), which received two Oscar nominations: Best Supporting Actress for Judy Davis and Best Original Screenplay for Allen. Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993) combined suspense with dark comedy and marked the return of Diane Keaton, Alan Alda and Anjelica Huston.

He returned to lighter fare such as the showbiz comedy involving mobsters Bullets Over Broadway (1994), which earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Director, followed by a musical, Everyone Says I Love You (1996). The singing and dancing scenes in Everyone Says I Love You are similar to musicals starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. The comedy Mighty Aphrodite (1995), in which Greek drama plays a large role, won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for Mira Sorvino. Allen's 1999 jazz-based comedy-drama Sweet and Lowdown was nominated for two Academy Awards, for Sean Penn (Best Actor) and Samantha Morton (Best Supporting Actress). In contrast to these lighter movies, Allen veered into darker satire toward the end of the decade with Deconstructing Harry (1997) and Celebrity (1998).

On March 8, 1995, Allen's one-act play Central Park West[125] opened[126] off-Broadway as a part of a larger piece titled Death Defying Acts,[127] with two other one-act plays, one by David Mamet and one by Elaine May. Critics described Allen's contribution as "the longest and most substantial of the evening".[128] During this decade Allen also starred in the television film The Sunshine Boys (1995), based on the Neil Simon play of the same name,[129] and made a sitcom "appearance" via telephone in a 1997 episode, "My Dinner with Woody", of Just Shoot Me! that paid tribute to several of his films. He provided the voice of Z in DreamWorks' first animated film, Antz (1998), which featured many actors he had worked with; Allen's character was similar to his earlier roles.[130]

Small Time Crooks (2000) was Allen's first film with the DreamWorks studio and represented a change in direction: he began giving more interviews and made an attempt to return to his slapstick roots. The film is similar to the 1942 film Larceny, Inc. (from a play by S. J. Perelman).[131] Allen never commented on whether this was deliberate or if his film was in any way inspired by it. Small Time Crooks was a relative financial success, grossing over $17 million domestically, but Allen's next four films foundered at the box office, including Allen's most costly film, The Curse of the Jade Scorpion (with a budget of $26 million). Hollywood Ending, Anything Else, and Melinda and Melinda have "rotten" ratings on film-review website Rotten Tomatoes and each earned less than $4 million domestically.[132] Some critics claimed that Allen's early 2000s films were subpar and expressed concern that his best years were behind him.[133] Others were less harsh; reviewing the little-liked Melinda and Melinda, Roger Ebert wrote, "I cannot escape the suspicion that if Woody had never made a previous film, if each new one was Woody's Sundance debut, it would get a better reception. His reputation is not a dead shark but an albatross, which with admirable economy Allen has arranged for the critics to carry around their own necks."[134]

2005–2014: Career resurgence

"In the United States things have changed a lot, and it's hard to make good small films now", Allen said in a 2004 interview. "The avaricious studios couldn't care less about good films—if they get a good film they're twice as happy but money-making films are their goal. They only want these $100 million pictures that make $500 million."[135] Allen traveled to London, where he made Match Point (2005), one of his most successful films of the decade, garnering positive reviews.[136] Set in London, it starred Jonathan Rhys Meyers and Scarlett Johansson. It is markedly darker than Allen's first four films with DreamWorks SKG. In Match Point Allen shifts focus from the intellectual upper class of New York to the moneyed upper class of London. The film earned more than $23 million domestically (more than any of his films in nearly 20 years) and over $62 million in international box office sales.[137] It earned Allen his first Academy Award nomination since 1998, for Best Writing – Original Screenplay, with directing and writing nominations at the Golden Globes, his first Globe nominations since 1987. In a 2006 interview with Premiere Magazine he said it was the best film he had ever made.[138]

Allen reached an agreement to film Vicky Cristina Barcelona in Avilés, Barcelona, and Oviedo, Spain, where shooting started on July 9, 2007. The movie featured Scarlett Johansson, Javier Bardem, Rebecca Hall and Penélope Cruz.[139][140] The film premiered at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival to rapturous reviews, and became a box office success. Vicky Cristina Barcelona won Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy at the Golden Globe awards. Cruz received the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress.

In April 2008 he began filming Whatever Works,[141] a film aimed more toward older audiences, starring Larry David, Patricia Clarkson, and Evan Rachel Wood.[142] Released in 2009 and described as a dark comedy, it follows the story of a botched suicide attempt turned messy love triangle. Allen wrote Whatever Works in the 1970s, and David's character was written for Zero Mostel, who died the year Annie Hall came out. Allen was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2001.[143] You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger, filmed in London, stars Antonio Banderas, Josh Brolin, Anthony Hopkins, Anupam Kher, Freida Pinto and Naomi Watts. Filming started in July 2009. It was released theatrically in the U.S. on September 23, 2010, following a Cannes debut in May 2010, and a screening at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 12, 2010.

Allen announced that his next film would be titled Midnight in Paris,[144] starring Owen Wilson, Marion Cotillard, Rachel McAdams, Michael Sheen, Corey Stoll, Allison Pill, Tom Hiddleston, Adrien Brody, Kathy Bates, and Carla Bruni, the First Lady of France at the time of production. The film follows a young engaged couple in Paris who see their lives transformed. It debuted at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival on May 12, 2011. Allen said he wanted to "show the city emotionally" during the press conference. "I just wanted it to be the way I saw Paris—Paris through my eyes", he said.[145] The film was almost universally praised, receiving a 93% on Rotten Tomatoes.[146] Midnight in Paris won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay and became his highest-grossing film, making $151 million worldwide on a $17 million budget.[147]

On October 20, 2011, Allen's one-act play Honeymoon Motel opened on Broadway as part of a larger piece titled Relatively Speaking, with two other one-act plays by Ethan Coen and Elaine May.[148] In February 2012, Allen appeared on a panel at the 92nd Street Y in New York City with moderators Dick Cavett and Annette Insdorf, discussing his films and career.[149] His next film, To Rome with Love (2012), is a Rome-set comedy starring Jesse Eisenberg, Elliot Page, Alec Baldwin, Penelope Cruz, Greta Gerwig, and Judy Davis. The film is structured in four vignettes featuring dialogue in both Italian and English. It marked Allen's return to acting since his last role in Scoop.[150] Bob Mondello gave it a mixed review, writing, "To Rome with Love is just froth—a romantic sampler with some decent jokes and gorgeous Roman backdrops. It goes down easily, but I have to say it's interesting less for what it is than for how it is."[151]

Allen's next film, Blue Jasmine, debuted in July 2013.[152] The film is set in San Francisco and New York, and stars Alec Baldwin, Cate Blanchett, Louis C.K., Andrew Dice Clay, Sally Hawkins, and Peter Sarsgaard.[153] It opened to critical acclaim, with Eric Kohn of IndieWire calling it "his most significant movie in years".[154] The film earned Allen another Academy Award nomination for Best Original Screenplay,[155] and Blanchett received the Academy Award for Best Actress.[156] Allen co-starred with John Turturro in Fading Gigolo, written and directed by Turturro, which premiered in September 2013.[157] Also in 2013, Allen shot the romantic comedy Magic in the Moonlight with Emma Stone and Colin Firth in Nice, France. The film is set in the 1920s on the French Riviera.[158] It was a modest financial success, earning $51 million on a $16 million budget.[159] For the BBC, Owen Gleiberman wrote, "Magic in the Moonlight is Allen's most gratifyingly airy concoction in a while, but it's also a comedy that insists, in the end, on making an overly rational case for the power of the irrational."[160]

It's really cool to work with a director who's done so much, because he knows exactly what he wants. The fact that he does one shot for an entire scene—[and] this could be a scene with eight people and one to two takes—it gives you a level of confidence... he's very empowering.

—Blake Lively, on acting in Café Society, June 2016[161]

On March 11, 2014, Allen's musical Bullets over Broadway opened on Broadway at the St. James Theatre.[162] It was directed and choreographed by Susan Stroman and starred Zach Braff, Nick Cordero, and Betsy Wolfe. The production received mixed reviews, with The Hollywood Reporter writing, "this frothy show does provide dazzling art direction and performances, as well as effervescent ensemble numbers." Allen received a Tony Award nomination for Best Book of a Musical. The show received six Tony nominations.[163]

In July and August 2014, Allen filmed the mystery drama Irrational Man in Newport, Rhode Island, with Joaquin Phoenix, Emma Stone, Parker Posey and Jamie Blackley.[164] Allen said that this film, as well as the next three he had planned, had the financing and full support of Sony Pictures Classics.[165] Jonathan Romney of Film Comment gave the film a mixed review, praising Stone's performance but calling the film "disconcertingly impersonal—all the more so as it overtly carries certain traditional marks of his patented brand, being a light-highbrow comedy of manners, peppered with bookish in-jokes."[166]

2015–2019

On January 14, 2015, Amazon Studios announced a full-season order for a half-hour Amazon Prime Instant Video series that Allen would write and direct, marking the first time he has developed a television show. Allen said of the series, "I don't know how I got into this. I have no ideas and I'm not sure where to begin. My guess is that Roy Price [the head of Amazon Studios] will regret this."[167][168][169] At the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, Allen said of his upcoming Amazon show: "It was a catastrophic mistake. I don't know what I'm doing. I'm floundering. I expect this to be a cosmic embarrassment."[170] On September 30, 2016, Amazon Video debuted Allen's first television series production, Crisis in Six Scenes. The series is a comedy set during the 1960s. It focuses on the life of a suburban family after a surprise visitor creates chaos among them. It stars Allen, Elaine May, and Miley Cyrus, with the latter playing a radical hippie fugitive who sells marijuana.[171][172]

Allen's next film, Café Society, starred an ensemble cast, including Jesse Eisenberg, Kristen Stewart, and Blake Lively.[173] Bruce Willis was set to co-star, but was replaced by Steve Carell during filming.[174] The film is distributed by Amazon Studios, and opened the 2016 Cannes Film Festival on May 11, 2016, the third time Allen has opened the festival.[175] Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian gave the film a positive review, writing, "The film looks ravishing, with shots of New York which recall images in Allen's great work, Manhattan, but however wonderfully composed, there is something almost touristy in both them, and in his evocation of golden age Tinseltown, like his homages to Paris and Rome. Allen brings it all together in his closing moments which conjure something unexpectedly melancholy and shrewdly judged. It has entertainment and charm."[176]

In September 2016 Allen started filming the drama film Wonder Wheel, set in the 1950s in Coney Island, and starring Kate Winslet, Justin Timberlake, Juno Temple, and Jim Belushi.[177] The film served as the closing night selection at the 55th New York Film Festival on October 15, 2017,[178] and was theatrically released on December 1, 2017,[179] as the first movie self-distributed to theaters by Amazon Studios.[180] The film received mixed reviews, with critics praising Winslet's leading performance. Owen Gleiberman of Variety wrote, "Wonder Wheel isn't a comedy—on the contrary, it often feels like the most earnest kitchen-sink drama that Clifford Odets never wrote. It may or may not turn out to be an awards picture, but it's a good night out, and that's not nothing."[181] In 2017, Allen received a standing ovation when he made a rare public appearance at the 45th Annual Life Achievement Tribute award ceremony for Diane Keaton. Before presenting her with the award he spoke about their longtime collaboration and friendship, saying, "From the minute I met her, she was a great, great inspiration to me. Much of what I have accomplished in my life I owe for sure to her".[182]

Allen returned to filming in New York City with the romantic film A Rainy Day in New York, starring Timothée Chalamet, Selena Gomez, Elle Fanning, Jude Law, Diego Luna, Liev Schreiber and Rebecca Hall. The production in New York began in September 2017.[183] During the film's release, Chalamet, Gomez, and Hall announced, in the light of the Me Too movement, that they would donate their salaries to various charities.[184] The film received mixed reviews but earned praise for its performances. In February 2019 it was announced that Amazon Studios had dropped A Rainy Day in New York and would no longer finance, produce, or distribute films with Allen. He filed a lawsuit for $68 million, alleging Amazon gave "vague reasons" to terminate the contract, dropped the film over "a 25-year old, baseless allegation", and did not make payments.[185][186] The case was later settled and dismissed.[187][188] It was released throughout Europe beginning in July 2019,[189][190] receiving mixed reviews and grossing $20 million.[191][192][193] After over a year's delay, the film was released in the U.S. on October 9, 2020, by MPI Media Group and Signature Entertainment.[194]

In May 2019, it was announced that Allen's next film would be titled Rifkin's Festival, and Variety magazine confirmed that its cast would include Christoph Waltz, Elena Anaya, Louis Garrel, Gina Gershon, Sergi López, and Wallace Shawn, and that it would be produced by Gravier Productions.[195] The film was produced with Mediapro, an independent Spanish TV-film company.[196] Rifkin's Festival completed filming in October 2019.[197][198] On September 18, 2020, it premiered at the San Sebastián International Film Festival. It received mixed reviews, though Jessica Kiang of The New York Times called it "to the ravenous captive, like finding an unexpected stash of dessert".[199]

2020 to present

On March 2, 2020, it was announced that after shopping the book from publishers it was decided that Grand Central Publishing would release Allen's autobiography, Apropos of Nothing, on April 7, 2020.[200][201][202] According to the publisher, the book is a "comprehensive account of Allen's life, both personal and professional, and describes his work in films, theater, television, nightclubs, and print...Allen also writes of his relationships with family, friends, and the loves of his life."[203][204] The decision to publish the book was criticized by Dylan and Ronan Farrow, the latter of whom cut ties with the publisher.[205][206] The announcement also incited criticism from employees of the publishers.[207][208] On March 6, the publisher announced that it had canceled the book's release, saying in part, "The decision to cancel Mr. Allen's book was a difficult one."[209] Hachette's decision also drew criticism from novelist Stephen King, Executive director of PEN America Suzanne Nossel, and others.[210][211] On March 6, 2020, Manuel Carcassonne of Hachette's French branch, the publishing company Stock, announced it would publish the book if Allen permitted it.[210] On March 23, 2020, Arcade published the memoir.[212][213][214]

In June 2020, Allen appeared on Alec Baldwin's podcast Here's the Thing and talked about his career as a standup comedian, comedy writer, and filmmaker, and his life during the COVID-19 pandemic.[215] In September 2022, Allen suggested that he might retire from filmmaking after the release of his next film.[216] In an interview with La Vanguardia, Allen said, "My idea, in principle, is not to make more movies and focus on writing."[217] Allen's publicist later said, "Woody Allen never said he was retiring, nor did he say he was writing another novel. He said he was thinking about not making films, as making films that go straight or very quickly to streaming platforms is not so enjoyable for him, as he is a great lover of the cinema experience. Currently, he has no intention of retiring and is very excited to be in Paris shooting his new movie, which will be the 50th."[218]

Allen has made 50 feature films to date, with his latest film, Coup de chance (2023), a domestic thriller set in Paris. The film is Allen's first French-language film.[219] It premiered at the 80th Venice International Film Festival to positive reviews.[220] Chris Vognar of Rolling Stone called it "a pretty slight and minor film, but for an 87-year-old American working in a second language, it can't help but seem impressive".[221] Owen Gleiberman of Variety called it "his best since Blue Jasmine".[222]

In February 2024, it was reported that Allen had expressed interest in starting a new film as soon as summer 2024: "In a new interview with Spanish filmmaker David Trueba, the 88-year-old Allen confirms that he is currently trying to launch a new film, which could start shooting as early as this summer in Italy."[223]

Theater

While best known for his films, Allen has also had a successful theater career, starting as early as 1960, when he wrote sketches for the revue From A to Z. His first great success was Don't Drink the Water, which opened in 1968 and ran for 598 performances on Broadway. His success continued with Play It Again, Sam, which opened in 1969, starring Allen and Diane Keaton. The show played for 453 performances and was nominated for three Tony Awards, although none of the nominations were for Allen's writing or acting.[224]

In the 1970s, Allen wrote a number of one-act plays, such as God and Death, which were published in his 1975 collection Without Feathers. In 1981, Allen's play The Floating Light Bulb opened on Broadway. It was a critical success and a commercial flop. Despite two Tony Award nominations, a Tony win for the acting of Brian Backer (who won the 1981 Theater World Award and a Drama Desk Award for his work), the play only ran for 62 performances.[225]

In 1995, after a long hiatus from the stage, Allen returned to theater with the one-act Central Park West,[226] an installment in an evening of theater, Death Defying Acts, that also included new work by David Mamet and Elaine May.[227]

For the next few years, Allen had no direct involvement with the stage, but productions of his work were staged. God was staged at The Bank of Brazil Cultural Center in Rio de Janeiro,[228] and theatrical adaptations of Allen's films Bullets Over Broadway[229] and September[230] were produced in Italy and France, respectively, without Allen's involvement.

In 2003, Allen returned to the stage with Writer's Block, an evening of two one-acts, Old Saybrook[231] and Riverside Drive,[232][226] that played Off-Broadway's Atlantic Theatre.[233] The production marked his stage-directing debut[234] and sold out the entire run.[235]

In 2004, Allen's first full-length play since 1981, A Second Hand Memory,[236] was directed by Allen and enjoyed an extended run Off-Broadway.[235] In June 2007 it was announced that Allen would make two more creative debuts in the theater, directing a work he did not write and an opera—a reinterpretation of Puccini's Gianni Schicchi for the Los Angeles Opera[237]—which debuted at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion on September 6, 2008.[238] Of his direction of the opera, Allen said, "I have no idea what I'm doing." His production of the opera opened the Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto, Italy, in June 2009.[239]

In October 2011, Allen's one-act play Honeymoon Motel premiered as one in a series of one-act plays on Broadway titled Relatively Speaking.[240] Also contributing to the series were Elaine May and Ethan Coen; John Turturro directed.[241]

It was announced in February 2012 that Allen would adapt Bullets over Broadway into a Broadway musical. It ran from April 10 to August 24, 2014.[242] The cast included Zach Braff, Nick Cordero and Betsy Wolfe. The show was directed and choreographed by Susan Stroman, known for directing the stage and film productions of Mel Brooks's The Producers. The show drew mixed reviews from critics but received six Tony Award nominations, including one for Allen for Best Book of a Musical.[243]

Jazz band

Allen is a passionate fan of jazz, which appears often in the soundtracks to his films. He began playing clarinet as a child and took his stage name from clarinetist Woody Herman.[244] He has performed publicly at least since the late 1960s, including with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band on the soundtrack of Sleeper.[245]

Woody Allen and his New Orleans Jazz Band have been playing each Monday evening at the Carlyle Hotel in Manhattan for many years[246] specializing in New Orleans jazz from the early 20th century.[247] He plays songs by Sidney Bechet, George Lewis, Johnny Dodds, Jimmie Noone, and Louis Armstrong.[248] The documentary film Wild Man Blues (directed by Barbara Kopple) chronicles a 1996 European tour by Allen and his band, as well as his relationship with Previn. The band released the albums The Bunk Project (1993) and the soundtrack of Wild Man Blues (1997). In 2005, Allen, Eddy Davis and Conal Fowkes released the trio album Woody With Strings.[249] In a 2011 review of a concert by Allen's jazz band, critic Kirk Silsbee of the Los Angeles Times suggested that Allen should be regarded a competent musical hobbyist with a sincere appreciation for early jazz: "Allen's clarinet won't make anyone forget Sidney Bechet, Barney Bigard or Evan Christopher. His piping tone and strings of staccato notes can't approximate melodic or lyrical phrasing. Still his earnestness and the obvious regard he has for traditional jazz counts for something."[250]

Allen and his band played at the Montreal International Jazz Festival on two consecutive nights in June 2008.[251] For many years he wanted to make a film about the origins of jazz in New Orleans. Tentatively titled American Blues, the film would follow the different careers of Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet. Allen stated that the film would cost between $80 and $100 million and is therefore unlikely to be made.[252]

Influence

Allen has said that he was enormously influenced by comedians Bob Hope, Groucho Marx, Mort Sahl, Charlie Chaplin, W.C. Fields,[253] playwright George S. Kaufman and filmmakers Ernst Lubitsch and Ingmar Bergman.[254]

Many comedians have cited Allen as an influence, including Louis C.K.,[255] Larry David,[256] Jon Stewart,[257] Chris Rock,[258] Steve Martin,[259] John Mulaney,[260] Bill Hader,[261] Aziz Ansari,[262] Sarah Silverman,[263] Conan O'Brien,[264] Seth MacFarlane,[265] Seth Meyers,[266] Richard Ayoade,[267] Bill Maher,[268] Albert Brooks,[269] John Cleese,[262] Garry Shandling,[270] Bob Odenkirk,[271] Richard Kind,[272] Rob McElhenney,[273] and Mike Schur.[274]

Many filmmakers have also cited Allen as an influence, including Wes Anderson,[275] Greta Gerwig,[276] Noah Baumbach,[277] Luca Guadagnino,[278] Nora Ephron,[279] Whit Stillman,[280] Mike Mills,[281] Ira Sachs,[282] Richard Linklater,[283] Charlie Kaufman,[284] Nicole Holofcener,[285] Rebecca Miller,[286] Tamara Jenkins,[287] Alex Ross Perry,[288] Greg Mottola,[289] Lynn Shelton,[290] Lena Dunham,[291] Lawrence Michael Levine,[292] Olivier Assayas,[293] the Safdie brothers,[294] and Amy Sherman-Palladino.[295]

Directors who admire Allen's work include Quentin Tarantino, who called him "one of the greatest screenwriters of all time",[296] as well as Martin Scorsese, who said in Woody Allen: A Documentary, "Woody's sensibilities of New York City is one of the reasons why I love his work, but they are extremely foreign to me. It's not another world; it's another planet". Stanley Donen stated he liked Allen's films, Spike Lee has called Allen a "great, great filmmaker" and Pedro Almodóvar has said he admires Allen's work.[297][298][299] In 2012, directors Mike Leigh, Asghar Farhadi, and Martin McDonagh respectively included Radio Days (1987), Take the Money and Run (1969), and Manhattan among their Top 10 films for Sight & Sound.[300][301][302] Other admirers of his work include Olivia Wilde and Jason Reitman, who staged live readings of Hannah and Her Sisters and Manhattan respectively.[303][304] Filmmaker Edgar Wright listed five of Allen's films (Take the Money and Run, Bananas, Play It Again, Sam, Sleeper, Annie Hall) in his list of 100 Favorite Comedy films.[305]

Bill Hader cited Allen's mockumentary films Take the Money and Run and Zelig as the biggest inspirations of the IFC series Documentary Now![306]

Film critics including Roger Ebert and Barry Norman have highly praised Allen's work.[307][308] In 1980, on Sneak Previews, Siskel and Ebert called Allen and Mel Brooks "the two most successful comedy directors in the world today ... America's two funniest filmmakers."[309] Pauline Kael wrote of Allen that "his comic character is enormously appealing to people partly because he's the smart, urban guy who at the same time is intelligent, is vulnerable, and somehow by his intelligence, he triumphs".[310]

Favorite films

In 2012, Allen participated in the Sight & Sound film polls.[311] Held every ten years to select the greatest films of all time, contemporary directors were asked to select ten films of their choice. Allen's choices, in alphabetical order, were:[312][313]

- The 400 Blows (France, 1959)

- 8½ (Italy, 1963)

- Amarcord (Italy, 1972)

- Bicycle Thieves (Italy, 1948)

- Citizen Kane (USA, 1941)

- The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (France, 1972)

- La Grande Illusion (France, 1937)

- Paths of Glory (USA, 1957)

- Rashomon (Japan, 1950)

- The Seventh Seal (Sweden, 1957)

In his 2020 autobiography Apropos of Nothing Allen praised Elia Kazan's A Streetcar Named Desire (1951):

the movie of Streetcar is for me total artistic perfection.... It's the most perfect confluence of script, performance, and direction I've ever seen. I agree with Richard Schickel, who calls the play perfect. The characters are so perfectly written, every nuance, every instinct, every line of dialogue is the best choice of all those available in the known universe. All the performances are sensational. Vivien Leigh is incomparable, more real and vivid than real people I know. And Marlon Brando was a living poem. He was an actor who came on the scene and changed the history of acting. The magic, the setting, New Orleans, the French Quarter, the rainy humid afternoons, the poker night. Artistic genius, no holds barred.

Film activism and preservation

In 1987, Allen joined Ginger Rogers, Sydney Pollack, and Miloš Forman at a Senate Judiciary committee hearing in Washington, D.C., where they each gave testimony against Ted Turner's and other companies' colorizing films without the artists' consent.[314][315] Only one senator, Patrick Leahy, was present for the testimony. Allen testified:

If directors had their way, we would not let our films be tampered with in any way—broken up for commercial or shortened or colorized. But we've fought the other things without much success, and now colorization—because it's so horrible and preposterous and more acutely noticeable by audiences—is the straw that broke the camel's back.... The presumption that colorizers are doing him [the director] a favor and bettering his movie is a transparent attempt to justify the mutilation of art for a few extra dollars.[316]

Allen also spoke about his decisions to make films in black and white, such as Manhattan, Stardust Memories, Broadway Danny Rose, and Zelig. Film director John Huston appeared in a pretaped video, and Rogers read a statement by Jimmy Stewart criticizing the colorization of his film It's a Wonderful Life.[314]

In 1990, The Film Foundation was founded as a nonprofit film preservation organization that collaborates with film studios to restore prints of old or damaged films to meet the vision of the original filmmaker. Allen was part of the founding and sat on the foundation's original board of directors alongside Martin Scorsese, Robert Altman, Francis Ford Coppola, Clint Eastwood, Stanley Kubrick, George Lucas, Sydney Pollack, Robert Redford, and Steven Spielberg.[317]

Works

Filmography

Theatrical works

In addition to directing, writing, and acting in films, Allen has written and performed in a number of Broadway theater productions.

| Year | Title | Credit | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | From A to Z | Writer (book) | Plymouth Theatre, Broadway |

| 1966 | Don't Drink the Water | Writer | Coconut Grove Playhouse, Florida Morosco Theatre, Broadway |

| 1969 | Play It Again, Sam | Writer Performer (Allan Felix) | Broadhurst Theatre, Broadway[27] |

| 1975 | God | Writer | — |

| 1975 | Death | Writer | — |

| 1981 | The Floating Light Bulb | Writer | Vivian Beaumont Theater, Broadway |

| 1995 | Death Defying Acts: Central Park West | Writer | Variety Arts Theatre, Off-Broadway |

| 2003 | Old Saybrook | Writer and director | Atlantic Theatre Company, Off-Broadway |

| 2003 | Riverside Drive | Writer and director | |

| 2004 | A Second-Hand Memory | Writer and director | |

| 2008 | Gianni Schicchi | Director | Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles |

| 2011 | "Honeymoon Motel" | Writer | Brooks Atkinson Theatre, Broadway |

| 2014 | Bullets Over Broadway | Writer (book) | St. James Theatre, Broadway |

| 2015 | Gianni Schicchi | Director | Teatro Real, Madrid |

| 2019 | Director | La Scala, Italy |

Bibliography

- Getting Even (1971)

- Without Feathers (1975)

- Side Effects (1980)

- The Insanity Defense: The Complete Prose (2007)

- Mere Anarchy (2007)

- Apropos of Nothing (2020) (memoirs)

- Zero Gravity (2022)

Discography

- Woody Allen (Colpix Records, 1964)

- Woody Allen Vol. 2 (Colpix Records, 1965)

- The Third Woody Allen Album (Capitol Records, 1968)

- The Nightclub Years 1964–1968 (United Artists Records, 1972)

- Standup Comic (Casablanca Records, 1978)

- Wild Man Blues (RCA Victor, 1998)

- Woody With Strings (New York Jazz Records, 2005)

Awards and honors

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Over his more than 50-year film career, Allen has received many award nominations. He holds the record for most Academy Award nominations for Best Original Screenplay, with 16 nominations and three wins (Annie Hall, Hannah and Her Sisters, and Midnight in Paris). Allen has been nominated for Best Director seven times and won for Annie Hall. Three of Allen's films have been nominated for Academy Award for Best Picture, Annie Hall, Hannah and Her Sisters, and Midnight in Paris.

Allen shuns award ceremonies, citing their subjectivity. His first and only appearance at the Academy Awards was at the 2002 Oscars, where he received a standing ovation. As a New York icon, he had been asked by the Academy to introduce a film montage of clips of New York City in the movies that Nora Ephron compiled to honor the city after the 9/11 attacks.[318] Two of his films have been inducted into the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant".

Allen has received numerous honors, including an Honorary Golden Palm from the Cannes Film Festival in 2002 and a Career Golden Lion from the Venice International Film Festival in 1995. He also received a BAFTA Fellowship in 1997, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Directors Guild of America and a Golden Globe Cecil B. DeMille Award in 2014. He was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society in 2010.[319] In 2015, the Writers Guild of America named his screenplay for Annie Hall first on its list of the "101 Funniest Screenplays".[320] In 2011, PBS televised the film biography Woody Allen: A Documentary on its series American Masters.[79]

In 2004, Comedy Central ranked Allen fourth on a list of the 100 greatest stand-up comedians,[321][322] while a UK survey ranked Allen the third-greatest comedian.[323]

| Year | Title | Academy Awards | BAFTA Awards | Golden Globe Awards | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominations | Wins | Nominations | Wins | Nominations | Wins | ||

| 1977 | Annie Hall | 5 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| 1978 | Interiors | 5 | 2 | 1 | 4 | ||

| 1979 | Manhattan | 2 | 10 | 2 | 1 | ||

| 1983 | Zelig | 2 | 5 | 2 | |||

| 1984 | Broadway Danny Rose | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1985 | The Purple Rose of Cairo | 1 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 2 | |

| 1986 | Hannah and Her Sisters | 7 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 1 |

| 1987 | Radio Days | 2 | 7 | 2 | |||

| 1989 | Crimes and Misdemeanors | 3 | 6 | 1 | |||

| 1990 | Alice | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1992 | Husbands and Wives | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1993 | Manhattan Murder Mystery | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1994 | Bullets Over Broadway | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1995 | Mighty Aphrodite | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1996 | Everyone Says I Love You | 1 | |||||

| 1997 | Deconstructing Harry | 1 | |||||

| 1999 | Sweet and Lowdown | 2 | 2 | ||||

| 2000 | Small Time Crooks | 1 | |||||

| 2005 | Match Point | 1 | 4 | ||||

| 2008 | Vicky Cristina Barcelona | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| 2011 | Midnight in Paris | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |

| 2013 | Blue Jasmine | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Total | 53 | 12 | 61 | 17 | 47 | 9 | |

Personal life

Allen has been married three times: to Harlene Rosen from 1956 to 1959, Louise Lasser from 1966 to 1970, and Soon-Yi Previn since 1997. He also had a 12-year relationship with actress Mia Farrow and relationships with Stacey Nelkin and Diane Keaton.

Early marriages and relationships

In 1956, Allen married Harlene Rosen. He was 20 and she was 17. The marriage lasted until 1959.[324] Rosen, whom Allen called "the Dread Mrs. Allen" in his standup act, sued him for defamation as a result of comments he made during a television appearance shortly after their divorce. In his mid-1960s album Standup Comic, Allen said that Rosen had sued him because of a joke he made in an interview. Rosen had been sexually assaulted outside her apartment. According to Allen, the newspapers reported that she had been "violated". In the interview, Allen said, "Knowing my ex-wife, it probably wasn't a moving violation." In an interview on The Dick Cavett Show, Allen repeated his comments and said that she "sued me for a million dollars".[325]

In 1966, Allen married Louise Lasser. They divorced in 1970. Lasser provided voice dubbing in Allen's What's Up, Tiger Lily? and appeared in three of his other films: Take the Money and Run, Bananas, and Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* (*But Were Afraid to Ask). She also appeared briefly in Stardust Memories.

According to the Los Angeles Times, Manhattan was based on Allen's romantic relationship with actress Stacey Nelkin.[326] Her bit part in Annie Hall ended up on the cutting room floor, and their relationship, never publicly acknowledged by Allen, reportedly began when she was 17 and a student at Stuyvesant High School in New York.[327][328][329] In December 2018 The Hollywood Reporter interviewed Babi Christina Engelhardt, who said she had an eight-year affair with Allen that began in 1976 when she was 17 years old (they met when she was 16), and that she believes the character of Tracy in Manhattan is a composite of any number of Allen's presumed other real-life young paramours from that period, not necessarily Nelkin or Engelhardt. When asked, Allen declined to comment.[330]

Diane Keaton

In 1968,[331] Allen cast Diane Keaton in his Broadway show Play It Again, Sam. During the run she and Allen became romantically involved. Although they broke up after a year, she continued to star in his films, including Sleeper as a futuristic poet and Love and Death as a composite character based on the novels of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. Annie Hall was very important in Allen's and Keaton's careers. It is said that the role was written for her, as Keaton's birth name was Diane Hall. She then starred in Interiors as a poet, followed by Manhattan. In 1987, she had a cameo as a nightclub singer in Radio Days, and she was chosen to replace Mia Farrow in Manhattan Murder Mystery after Allen and Farrow began having problems with their relationship. In total Keaton has starred in eight of Allen's films. As of 2018 Keaton and Allen remain close friends.[332] In a rare public appearance, Allen presented Keaton with the AFI Life Achievement Award in 2017.[333]

Mia Farrow

Allen and Mia Farrow met in 1979 and began a relationship in 1980;[334] Farrow starred in 13 of Allen's films from 1982 to 1992.[335] Throughout the relationship they lived in separate apartments on opposite sides of Central Park in Manhattan. Farrow had seven children when they met: three biological sons from her marriage to composer André Previn, three adopted girls (two Vietnamese and one South Korean, Soon-Yi Previn), and an adopted South Korean boy, Moses Farrow.[334]

In 1984, she and Allen tried to conceive a child together; Allen agreed to this on the understanding that he need not be involved in the child's care. When the effort failed, Farrow adopted a baby girl, Dylan Farrow, in July 1985. Allen was not involved in the adoption, but when Dylan arrived he assumed a parental role toward her and began spending more time in Farrow's home.[336] On December 19, 1987, Farrow gave birth to their son Satchel Ronan O'Sullivan Farrow.[337][338] According to Allen, his intimate relationship with Mia Farrow ceased completely after Satchel's birth and he was asked to return her apartment key; they maintained a working relationship when they filmed a movie, and he regularly visited Moses, Dylan and Satchel, but he and Mia were only "social companions on those occasions where there'd be a dinner, an event, but after the event she'd go home and I'd go home."[339] In 1991, Farrow wanted to adopt another child. According to a 1993 custody hearing, Allen told her he would not object to another adoption so long as she would agree to his adoption of Dylan and Moses; that adoption was finalized in December 1991.[336] Eric Lax, Allen's biographer, wrote in The New York Times that Allen was "there before they [the children] wake up in the morning, he sees them during the day and he helps put them to bed at night".[334]

Soon-Yi Previn

In 1977, Mia Farrow and André Previn adopted Soon-Yi Previn from Seoul, South Korea. She had been abandoned. The Seoul Family Court established a Family Census Register (legal birth document) on her behalf on December 28, 1976, with a presumptive birth date of October 8, 1970;[340][341] according to Maureen Orth, a bone scan in the U.S. estimated that she was between five and seven years old.[b] According to Previn, her first friendly interaction with Allen took place when she was injured playing soccer during 11th grade and Allen offered to transport her to school. After her injury, she began attending New York Knicks basketball games with Allen in 1990.[343] They attended more games and by 1991 had become closer.[336] In September 1991, she began studies at Drew University in New Jersey.[344]

In January 1992, Farrow found nude photographs of Previn in Allen's home. Allen, then 56, told Farrow that he had taken the photos the day before, approximately two weeks after he first had sex with Previn.[345] Both Farrow and Allen contacted lawyers shortly after the photographs were discovered.[336][342] Previn was asked to leave summer camp because she was spending too much time taking calls from a "Mr. Simon", who turned out to be Allen.[344]

In an August 1992 interview with Time Magazine Allen said, "I am not Soon-Yi's father or stepfather", adding, "I've never even lived with Mia. I've never in my entire life slept at Mia's apartment, and I never even used to go over there until my children came along seven years ago. I never had any family dinners over there. I was not a father to her adopted kids in any sense of the word." Adding that Soon-Yi never treated him as a father figure and that he rarely spoke to her before their romantic relationship, Allen seemed to see few or no problems with their relationship.[346]

On August 17, 1992, Allen issued a statement saying that he was in love with Previn.[347] Their relationship became public and "erupted into tabloid headlines and late-night monologues in August 1992."[348]

Allen and Previn were married in Venice, Italy, on December 23, 1997.[349] They have two adopted daughters,[350][351] and live in the Carnegie Hill section of Manhattan's Upper East Side.[352]

Sexual abuse allegation

According to court testimony, on August 4, 1992, Allen visited the children at Mia Farrow's home in Bridgewater, Connecticut, while she was shopping with a friend.[342] The next day, that friend's babysitter told her employer that she had seen that "Dylan was sitting on the sofa, and Woody was kneeling on the floor, facing her, with his head in her lap".[353][354] When Farrow asked Dylan about it, Dylan allegedly said that Allen had touched Dylan's "private part" while they were alone together in the attic.[342] Allen strongly denied the allegation, calling it "an unconscionable and gruesomely damaging manipulation of innocent children for vindictive and self-serving motives".[355] He then began proceedings in New York Supreme Court for sole custody of his and Farrow's son Satchel, as well as Dylan and Moses, their two adopted children.[356] In March 1993, a six-month investigation by the Child Sexual Abuse Clinic of Yale-New Haven Hospital concluded that Dylan had not been sexually abused.[357][358]

In June 1993, Judge Elliott Wilk rejected Allen's bid for custody and rejected the allegation of sexual abuse. Wilk said he was less certain than the Yale-New Haven team that there was conclusive evidence that there was no sexual abuse and called Allen's conduct with Dylan "grossly inappropriate",[359][360][361] although not sexual.[362] In September 1993, the state prosecutor announced that despite having "probable cause", he would not pursue charges in order "to avoid the unjustifiable risk of exposing a child to the rigors and uncertainties of a questionable prosecution".[359][363] In October 1993 the New York Child Welfare Agency of the State Department of Social Services closed a 14-month investigation and concluded there was not credible evidence of abuse or maltreatment, and the allegation was unfounded.[364]

In 2014, when Allen received a Golden Globe Cecil B. DeMille Award for Lifetime Achievement, the issue returned to the forefront of media attention, with Mia Farrow and Ronan Farrow making disparaging remarks about Allen on Twitter.[365][366] On February 1, 2014, New York Times journalist Nicholas Kristof, with Dylan's permission, published a column that included excerpts from a letter Dylan had written to Kristof restating the allegation against Allen, and called out fellow actors who have continued to work in his films.[367][368] Allen responded to the allegation in an open letter, also in The New York Times, strongly denying it. "Of course, I did not molest Dylan...No one wants to discourage abuse victims from speaking out, but one must bear in mind that sometimes there are people who are falsely accused and that is also a terribly destructive thing", he wrote.[369][370][371]

In 2018, Moses Farrow (who was present at Mia's Bridgewater house during Allen's visit) published a blog post called "A Son Speaks Out." In the post, Moses strenuously denied the abuse allegations, writing, "given the incredibly inaccurate and misleading attacks on my father, Woody Allen, I feel that I can no longer stay silent as he continues to be condemned for a crime he did not commit." He also recounted a series of instances of alleged physical abuse at the hands of Mia Farrow: "It pains me to recall instances in which I witnessed siblings, some blind or physically disabled, dragged down a flight of stairs to be thrown into a bedroom or a closet, then having the door locked from the outside. [Mia] even shut my brother Thaddeus, paraplegic from polio, in an outdoor shed overnight as punishment for a minor transgression".[372][373] Hollywood remained largely split over the allegation. Some defended Dylan's allegation, while others vouched for Allen's innocence, citing potential extortion from Farrow as a result of Allen and Soon-Yi's courtship.[374]

Works about Allen

From 1976 to 1984 Stuart Hample wrote and drew Inside Woody Allen, a comic strip based on Allen's film persona.[375][376]

The 1997 documentary Wild Man Blues, directed by Barbara Kopple, focuses on Allen, and other documentaries featuring Allen include the 2002 cable television documentary Woody Allen: A Life in Film, directed by Time film critic Richard Schickel, which interlaces interviews of Allen with clips of his films,[377] and the 1986 short film Meetin' WA, in which Allen is interviewed by French New Wave director Jean-Luc Godard.[378]

In 2003, a life-size bronze statue of Allen was installed in Oviedo, Spain. He had visited the city the previous year to accept a Prince of Asturias Award.[379]

In 2011 the PBS series American Masters co-produced the documentary Woody Allen: A Documentary, directed by Robert B. Weide. New interviews provide insight and backstory with Diane Keaton, Scarlett Johansson, Penélope Cruz, Dianne Wiest, Larry David, Chris Rock, Martin Scorsese, Dick Cavett, and Leonard Maltin, among others.[380]

Eric Lax wrote the book Woody Allen: A Biography.[23]

In 2015 David Evanier published Woody: The Biography, which was billed as the first new biography of Allen in over a decade.

In early March 2020, Grand Central Publishing, a division of Hachette Book Group, announced that it would publish Allen's memoir, Apropos of Nothing, on April 7, 2020.[381] Days later, after employee walkouts, parent company Hachette announced that the title was canceled and rights had reverted to Allen.[382] On March 23, 2020, Skyhorse Publishing announced that it had acquired and released Apropos of Nothing through its Arcade imprint.[213]

В феврале 2021 года канал HBO выпустил Кирби Дика и Эми Зиринг четырехсерийный документальный фильм «Аллен против Фэрроу» , в котором исследуются обвинения в сексуальном насилии против Аллена. [383] [384] Сериал получил в основном положительные отзывы критиков. Лоррейн Али из Los Angeles Times написала, что это «приводит убедительный аргумент в пользу того, что Аллену сошло с рук немыслимое благодаря его славе, деньгам и почитаемому положению в мире кино - и что маленькая девочка так и не получила справедливости». [385] Рэйчел Бродски написала в The Independent , что «документальный фильм станет похоронным звоном по карьере Вуди Аллена». [386] Хэдли Фриман в The Guardian написала, что сериал «позиционирует себя как расследование, но гораздо больше напоминает пиар , столь же предвзятый и пристрастный, как реклама политического кандидата, очерняющая оппонента в предвыборный период». [387] В заявлении от имени Аллена и Превина документальный фильм был назван «жесткой работой, пронизанной ложью», и говорилось, что к ним обратились за два месяца до того, как он был показан на канале HBO, и «дан был всего лишь считанный день на то, чтобы «отреагировать». Разумеется, они отказались это сделать». [388] Создатели фильма заявили, что дали Аллену и Превину две недели на комментарии, что «более чем достаточно по журналистским стандартам». [389]

Примечания

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Несмотря на то, что в большинстве упоминаний о дате его рождения 1 декабря в своей автобиографии 2020 года « По поводу ничего » Аллен пишет, что на самом деле он родился 30 ноября: «На самом деле я родился тридцатого ноября, очень близко к полуночи, и мои родители передвинул дату, чтобы я мог начать с первого дня». [1] Это несоответствие впервые стало известно в 2015 году, когда автор Дэвид Эванье обратился к нему в своей книге «Вуди Аллен: Биография» . [2] [3] [4] [5] После подтверждения Аллена различные источники исправили дату в своих базах данных. [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13]

- ↑ Морин Орт ( Vanity Fair , ноябрь 1992 г.): «Никто не знает, сколько лет Сун-И на самом деле. Даже не видя ее, корейские чиновники указали в ее паспорте возраст — семь лет. Миа сделала ей сканирование костей в США. По оценкам семьи, Сун-И исполнилось 20 лет в этом году [1992], 8 октября. [342]

Ссылки

- ^ Аллен 2020 , с. 11 .

- ^ Эванье 2015 , с. 66.

- ↑ Хорган, Ричард (14 декабря 2015 г.). « Бронксская шишка Вуди Аллена ». Рекламная неделя . «День рождения Вуди на самом деле не 1 декабря, а 30 ноября».

- ^ « Возвращение к взлетам и падениям Вуди Аллена в день его 80-летия ». МетроФокус . 1 декабря 2015 г. «Сегодня, 1 декабря, легенда кино Вуди Аллен празднует свое 80-летие. Однако это не его настоящий день рождения. Он родился 30 ноября, но выбрал своим днем рождения первое декабря, чтобы не быть . 1."

- ↑ Эванье, Дэвид (9 ноября 2015 г.). « Как Вуди Аллен получил свое прозвище ». Время .

- ^ « Вуди Аллен | Биография, фильмы и факты ». Британская энциклопедия . Проверено 11 января 2024 г.

- ↑ Леонте, Тюдор (28 ноября 2022 г.). « Дни рождения знаменитых актеров и режиссеров на этой неделе: Вуди Аллену исполняется 87 лет ». Й! Развлечение .

- ^ «Вуди Аллен» . Британский институт кино . Архивировано из оригинала 3 сентября 2023 года.

- ^ « Вуди Аллен - Социальные сети и архивный контекст ». snaccooperative.org . Проверено 5 января 2024 г.

- ^ « Вуди Аллен ». Гнилые помидоры . Проверено 5 января 2024 г.

- ^ « Вуди Аллен (актер, сценарист и режиссер) ». OnThisDay.com .

- ^ « Вуди Аллен ». Альманах.com . Проверено 19 января 2024 г.

- ^ « Вуди Аллен - Классические фильмы Тернера ». Проверено 13 мая 2024 г.

- ^ «Вуди Аллен по традиции не будет выступать» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс . Проверено 21 марта 2020 г.

- ^ Валовой 2012 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ «Вуди Аллен – Художник» . Академия звукозаписи . 19 ноября 2019 года . Проверено 21 марта 2020 г.

- ^ « Энни Холл» обошла «Звездные войны» в номинации «Лучший фильм» . Канал «История» . Проверено 7 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Ньютон, Майкл (13 января 2012 г.). «Вуди Аллен: великий экспериментатор кино» . Хранитель . Лондон. Архивировано из оригинала 19 января 2018 года . Проверено 9 апреля 2012 г.

В 1970-е годы Аллен выглядел непочтительно и модно, принадлежа к поколению Нового Голливуда. В эпоху «авторов» он был олицетворением автора, сценаристом, режиссером и звездой своих фильмов, активно монтировал, выбирал саундтрек, инициировал проекты.

- ^ «Полночь в Париже — самый большой хит Вуди Аллена, он обошёл фильм 1986 года «Ханна и её сестры» в 40 миллионов долларов» . ИндиВайр . 19 июля 2011 года . Проверено 7 мая 2023 г.

- ^ «Скоро Йи-Превин о Миа Фэрроу и Вуди Аллене» . Стервятник . Проверено 6 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ Деб, Шопан ; Лейдерман, Дебора; Бахр, Сара (22 февраля 2021 г.). « Вуди Аллен, Миа Фэрроу, Сун-И Превин, Дилан Фэрроу: хронология » . Нью-Йорк Таймс .

- ^ Фланаган, Кейтлин (8 июня 2021 г.). «Что знала Миа Фэрроу» . Атлантика . Проверено 21 июня 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Лакс 1992 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Нью-Йорк Таймс : Мэрион Мид (2000). Неуправляемая жизнь Вуди Аллена . Скрибнер. ISBN 0-684-83374-3 .

решила родить ребенка в Бронксе, в больнице Маунт-Иден.

- ^ «Еврейская виртуальная библиотека» .

- ^ «Мартин Кенигсберг» . Разнообразие . 16 января 2001 года . Проверено 22 октября 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Биография Вуди Аллена (1935–)» . Filmreference.com . Проверено 9 марта 2010 г.

- ^ Бакстер 1998 , с. 11.

- ^ Норвуд и Поллак 2008 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Ньюман, Энди; Килганнон, Кори (5 июня 2002 г.). «Проклятие измученной публики: Вуди Аллен в искусстве и жизни» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 18 июня 2009 года . Проверено 16 января 2008 г.

«Я думаю, что он отвлекся от последних нескольких фильмов», - сказал 70-летний Норман Браун, рисовальщик на пенсии из Мидвуда, Бруклина, старого района Аллена, который сказал, что видел почти все из 33 фильмов Аллена.

- ^ Лакс 1992 , стр. 12–13.

- ^ Мид, Мэрион. «Беспокойная жизнь Вуди Аллена» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 14 ноября 2018 г.

- ^ Мид 2000 , с. 31 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Вуди Аллен о жизни, фильмах и всем, что работает» . Национальное общественное радио . 15 июня 2009 г.

- ^ «Вуди Аллен: Профиль комика» . Comedy-Zone.net . Проверено 16 января 2008 г.

- ^ Бромберг 2020 , с. 46.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Нахман 2003 , с. 525.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Вуди Аллен: Бегущий кролик». Время . 7 июля 1972 года.

- ^ Шмитц, Пол (31 декабря 2011 г.). «Уроки знаменитых бросивших колледж» . CNN . Проверено 2 сентября 2013 г.

- ^ Лакс 1992 , с. 74.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Келли, Кен (1 июля 1976 г.). «Разговор с настоящим Вуди Алленом (или кем-то похожим на него)». Роллинг Стоун . стр. 34–40.

- ^ Нахман 2003 , с. 541.

- ^ Лакс 1992 , с. 111.

- ^ Бернштейн, Адам. «Умер сценарист телекомедий Дэнни Саймон» . Вашингтон Пост . Проверено 17 января 2008 г.

- ^ Фриман, Хэдли (4 декабря 2021 г.). «Мэл Брукс о потере любви всей своей жизни: «Люди знают, насколько хорош был Карл Райнер, но не знают, насколько велик» » . Хранитель . Проверено 9 июня 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Нахман 2003 , с. 533.

- ^ О'Коннор, Джон Дж. (17 февраля 1987 г.). « Скрытая камера» отмечает 40-летие специальным выпуском . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 14 ноября 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Нахман 2003 , с. 542.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Нахман 2003 , с. 551.

- ^ Аллен и Луттацци 2004 , с. 7 «Предисловие Даниэле Лутацци к итальянскому переводу трилогии Аллена « Полная проза »»

- ^ Берр, Тай. «Деконструкция Вуди» . Развлекательный еженедельник . Архивировано из оригинала 19 августа 2007 года . Проверено 19 мая 2017 г.

- ^ Аллен, Вуди (24 октября 2004 г.). «Я ценю Джорджа С. Кауфмана» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 7 апреля 2005 года . Проверено 14 ноября 2018 г.

- ^ «Вуди Аллен: Бегущий кролик». Время . 7 июля 1972 г. стр. 5–6.

У меня никогда не было учителя, который произвел бы на меня хотя бы малейшее впечатление. Если вы спросите меня, кто мои герои, ответ будет простым и правдивым: Джордж С. Кауфман и братья Маркс.

- ^ Какутан 1995 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Галеф 2003 , стр. 146–160. [, диапазон страниц слишком широк ], .

- ^ Ицкофф, Дэйв (20 июля 2010 г.). «Увековечен тем, что не умирал: Вуди Аллен переходит на цифровые технологии» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 14 ноября 2018 г.

- ^ Рамирес, Энтони (19 июля 2007 г.). «Пение грустной песни для их пиано-бара» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 24 августа 2007 года . Проверено 25 октября 2020 г.

- ^ «Милтон Берл о встрече с Вуди Алленом» . EMMYTVLEGENDS.ORG . Проверено 19 февраля 2022 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Нахман 2003 , с. 545.

- ^ Нахман 2003 , с. 532.

- ^ «Да будет смех – еврейский юмор во всем мире» . Бейт Хатфуцот. 6 февраля 2017 года. Архивировано из оригинала 13 июня 2020 года . Проверено 10 октября 2019 г.

- ^ Нахман 2003 , с. 546.

- ^ Нахман 2003 , с. 550.

- ^ Нахман 2003 , с. 530.

- ^ Сканци, Андреа (2002). « Человек на Луне , интервью с комиком Даниэле Лутацци». Дикая банда (на итальянском языке).

- ^ «Президентская гонка демократов 1968 года» . Раскопки поп-истории . Проверено 27 февраля 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бенедикт, Лев (24 октября 2013 г.). «Золотая комедия: Шоу Вуди Аллена» . Хранитель . ISSN 0261-3077 . Проверено 23 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Джонсон 2007 , с. 223.

- ^ «VOTW: Вуди Аллен в телешоу Джина Келли, 1966 год» . WoodyAllenPages.com. 10 августа 2014 г.

- ^ «Джин Келли на телевидении» . Архив кино и телевидения Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе.

- ^ «Архив кино и телевидения» . Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе . Проверено 2 марта 2020 г.

- ^ Билли Грэм на шоу Вуди Аллена, 1967 г.

- ^ Финч, Кокс и Джайлз 2003 , стр. 113.

- ↑ Уильям Ф. Бакли на шоу Вуди Аллена, 1967 г.