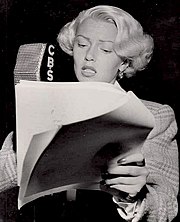

Лана Тернер

Лана Тернер | |

|---|---|

Тёрнер Пола Гессе на обложке журнала Photoplay, 1946 год. | |

| Рожденный | Джулия Джин Тернер 8 февраля 1921 г. Уоллес, Айдахо , США |

| Умер | 29 июня 1995 г. ( 74 года Лос-Анджелес , Калифорния , США |

| Образование | Голливудская средняя школа |

| Занятие | Актриса |

| Годы активности | 1937–1985 |

| Известный | |

| Супруги |

|

| Партнер | Джонни Стомпанато (1957–1958; его смерть) |

| Дети | Шерил Крейн |

| Signature | |

| |

Джулия Джин « Лана » Тернер ( / ˈ l ɑː n ə / LAH -ne ; [а] 8 февраля 1921 — 29 июня 1995) — американская актриса. За свою почти пятидесятилетнюю карьеру она добилась известности как модель пин-ап и киноактриса, а также благодаря своей широко разрекламированной личной жизни. В середине 1940-х годов она была одной из самых высокооплачиваемых американских актрис и одной из крупнейших звезд MGM : ее фильмы заработали для студии примерно один миллиард долларов в валюте 2024 года в течение ее 18-летнего контракта с ними. Тернер часто называют иконой популярной культуры из-за ее гламурной личности и экранной легенды Золотого века Голливуда . [4] Она была номинирована на многочисленные награды .

Тернер родилась в семье рабочего класса в Айдахо и провела там свое детство, прежде чем ее семья переехала в Калифорнию . В 1936 году, в возрасте 15 лет, она была обнаружена искателем талантов во время шопинга в солодовом магазине Top Hat в Голливуде . В возрасте 16 лет она подписала личный контракт с Warner Bros. режиссером Мервином Лероем , который взял ее с собой, когда он перешел в MGM в 1938 году. Вскоре она привлекла внимание, сыграв жертву убийства в своем экранном дебюте, фильме Лероя. Они не забудут (1937), а позже она перешла на второстепенные роли, в которых она часто выступала в роли инженю .

В начале 1940-х Тернер зарекомендовала себя как ведущая актриса и одна из лучших звезд MGM, снявшись в таких фильмах, как нуар «Джонни Игер» (1941), мюзикл « Девушка Зигфельда» (1941), ужасы «Доктор Джекил и мистер Хайд». (1941) и романтическая военная драма « Где-то я найду тебя» (1942), последний из нескольких фильмов, в которых она снялась вместе с Кларком Гейблом . Ее репутация гламурной роковой женщины была усилена ее получившей признание критиков игрой в фильме-нуар «Почтальон всегда звонит дважды» (1946), роль, которая сделала ее серьезной драматической актрисой. Ее популярность продолжалась в 1950-е годы в таких драмах, как «Плохое и красивое» (1952) и «Пейтон Плейс» (1957), за последний из которых она была номинирована на премию «Оскар» за лучшую женскую роль .

В 1958 году Тёрнер подверглась пристальному вниманию со стороны средств массовой информации, когда ее возлюбленный Джонни Стомпанато был зарезан ее дочерью-подростком Шерил Крейн во время домашней борьбы в их доме. Ее следующий фильм, «Имитация жизни» (1959), оказался одним из величайших коммерческих успехов в ее карьере, а ее главная роль в «Мадам Икс» (1966) принесла ей премию Давида ди Донателло как лучшая иностранная актриса. Большую часть 1970-х годов она провела на пенсии, в последний раз появившись в кино в 1980 году. В 1982 году она согласилась на широко разрекламированную и прибыльную повторяющуюся гостевую роль в телесериале « Фэлкон Крест» , который впоследствии получил особенно высокие рейтинги. В 1992 году у нее диагностировали рак горла , и она умерла три года спустя в возрасте 74 лет.

Life and career

[edit]1921–1936: Early life and education

[edit]

Julia Jean Turner[6][7][b] was born on February 8, 1921,[c] at Providence Hospital[13] in Wallace, Idaho.[14][15] She was the only child of Mildred Frances Cowan, who hailed from Lamar, Arkansas, and John Virgil Turner, a miner from Montgomery, Alabama. Her mother had English, Irish, and Scottish ancestry, while her father was of Dutch descent. She was born four days before her mother's 17th birthday.[16] Her parents had first met while her mother was 14 and her father was 24; Mildred was the daughter of a mine inspector and was visiting Picher, Oklahoma, a trip that was taken so her father could inspect the mines there.[8] Mildred's father objected to the courtship, but she and John eloped and moved west before settling in Idaho.[17]

The family lived in Burke, Idaho, at the time of Turner's birth,[18] and relocated to nearby Wallace in 1925,[d] where her father opened a dry cleaning service and worked in the local silver mines.[20] As a child, Turner was known to family and friends as Judy.[21] She expressed interest in performance at a young age, performing short dance routines at her father's Elks chapter in Wallace.[22] When she was three, she performed an impromptu dance routine at a charity fashion show in which her mother was modeling.[22]

The Turner family struggled financially and relocated to San Francisco when she was six years old, after which her parents separated.[23] On December 14, 1930,[24] her father won some money at a traveling craps game; he stuffed his winnings in his sock and headed home, but was later found bludgeoned to death on the corner of Minnesota and Mariposa Streets, on the edge of San Francisco's Potrero Hill and the Dogpatch District, with his left shoe and sock missing.[21][25] His robbery and homicide were never solved,[21] and his death had a profound effect on Turner.[26] She later said, "I know that my father's sweetness and gaiety, his warmth and his tragedy, have never been far from me. That, and a sense of loss and of growing up too fast."[27]

Turner sometimes lived with family friends or acquaintances so that her impoverished mother could save money.[28] They also frequently moved, for a time living in Sacramento and throughout the San Francisco Bay Area.[29] Following her father's death, Turner lived for a period in Modesto with a family who physically abused her and "treated her like a servant".[27] Her mother worked 80 hours per week as a beautician to support herself and her daughter,[30][31] and Turner recalled sometimes "living on crackers and milk for half a week".[29]

While baptized a Protestant at birth,[32] Turner attended Mass with the Hislops, a Catholic family with whom her mother had temporarily boarded her in Stockton, California.[9] She became "thrilled" by the ritual practices of the church,[9] and when she was seven, her mother allowed her to formally convert to Roman Catholicism.[9][33] Turner subsequently attended the Convent of the Immaculate Conception[10] in San Francisco, hoping to become a nun.[22] In the mid-1930s, Turner's mother developed respiratory problems and was advised by her doctor to move to a drier climate, upon which the two moved to Los Angeles in 1936.[22][25]

1937–1939: Discovery and early films

[edit]Her hair was dark, messy, uncombed. Her hands were trembling so she could barely read the script. But she had that sexy clean quality I wanted. There was something smoldering underneath that innocent face.

– Mervyn LeRoy on Turner during her first audition, December 1936[34]

Turner's discovery is considered a show-business legend and part of Hollywood mythology among film and popular cultural historians.[35][36][e] One version of the story erroneously has her discovery occurring at Schwab's Pharmacy,[39] which Turner claimed was the result of a reporting error that began circulating in articles published by columnist Sidney Skolsky.[38] By Turner's own account, she was a junior at Hollywood High School when she skipped a typing class and bought a Coca-Cola at the Top Hat Malt Shop[34][40] located on the southeast corner of Sunset Boulevard and McCadden Place.[41] While in the shop, she was spotted by William R. Wilkerson, publisher of The Hollywood Reporter.[35] Wilkerson was attracted by her beauty and physique, and asked her if she was interested in appearing in films, to which she responded: "I'll have to ask my mother first."[38] With her mother's permission, Turner was referred by Wilkerson to the actor/comedian/talent agent Zeppo Marx.[42] In December 1936, Marx introduced Turner to film director Mervyn LeRoy, who signed her to a $50 weekly contract with Warner Bros. on February 22, 1937 ($1,060 in 2023 dollars [43]).[34] She soon became a protégée of LeRoy, who suggested that she take the stage name Lana Turner, a name she would come to legally adopt several years later.[44]

Turner made her feature film debut in LeRoy's They Won't Forget (1937),[45] a crime drama in which she played a teenage murder victim. Though Turner only appeared on screen for a few minutes,[46] Wilkerson wrote in The Hollywood Reporter that her performance was "worthy of more than a passing note".[47] The film earned her the nickname of the "Sweater Girl" for her form-fitting attire, which accentuated her bust.[42][48] Turner always detested the nickname,[49] and upon seeing a sneak preview of the film, she recalled being profoundly embarrassed and "squirming lower and lower" into her seat.[33] She stated that she had "never seen myself walking before… [It was] the first time [I was] conscious of my body."[33] Several years after the film's release, Modern Screen journalist Nancy Squire wrote that Turner "made a sweater look like something Cleopatra was saving for the next visiting Caesar".[7] Shortly after completing They Won't Forget, she made an appearance in James Whale's historical comedy The Great Garrick (1937), a biographical film about British actor David Garrick, in which she had a small role portraying an actress posing as a chambermaid.[50][51]

In late 1937, LeRoy was hired as an executive at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), and asked Jack L. Warner to allow Turner to relocate with him to MGM.[52] Warner obliged, as he believed Turner would not "amount to anything".[53] Turner left Warner Bros. and signed a contract with MGM for $100 a week ($2,119 in 2023 dollars [43]).[54] The same year, she was loaned to United Artists for a minor role as a maid in The Adventures of Marco Polo.[47] Her first starring role for MGM was scheduled to be an adaptation of The Sea-Wolf, co-starring Clark Gable, but the project was eventually shelved.[55] Instead, she was assigned opposite teen idol Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland in the Andy Hardy film Love Finds Andy Hardy (1938).[56] During the shoot, Turner completed her studies with an educational social worker, allowing her to graduate high school that year.[57] The film was a box-office success,[58] and her appearance in it as a flirtatious high school student convinced studio head Louis B. Mayer that Turner could be the next Jean Harlow, a sex symbol who had died six months before Turner's arrival at MGM.[59]

Mayer helped further Turner's career by giving her roles in several youth-oriented films in the late 1930s, such as the comedy Rich Man, Poor Girl (1938) in which she played the sister of a poor woman romanced by a wealthy man, and Dramatic School (1938), in which she portrayed Mado, a troubled drama student.[60] In the former, she was billed as the "Kissing Bug from the Andy Hardy film".[60] Upon completing Dramatic School, Turner screen-tested unsuccessfully for the role of Scarlett O'Hara in Gone with the Wind (1939).[60] She was then cast in a supporting part as a "sympathetic bad girl" in Calling Dr. Kildare (1939), MGM's second entry in the Dr. Kildare series.[60] This was followed by These Glamour Girls (1939), a comedy in which she portrayed a taxi dancer invited to attend a dance with a male coed at his elite college.[61] Turner's onscreen sex appeal in the film was reflected by a review in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in which she was characterized as "the answer to 'oomph'".[62] In her next film, Dancing Co-Ed (1939), Turner was given first billing portraying Patty Marlow, a professional dancer who enters a college as part of a rigged national talent contest.[63] The film was a commercial success, and led to Turner appearing on the cover of Look magazine.[64]

In February 1940, Turner garnered significant publicity when she eloped to Las Vegas with 28-year-old bandleader Artie Shaw, her co-star in Dancing Co-Ed.[65][66] Though they had only briefly known each other, Turner recalled being "stirred by his eloquence", and after their first date the two spontaneously decided to get married.[67] Their marriage only lasted four months, but was highly publicized, and led MGM executives to grow concerned over Turner's "impulsive behavior".[68] In the spring of 1940, after the two had divorced, Turner discovered she was pregnant and had an abortion.[69] In contemporaneous press, it was noted she had been hospitalized for "exhaustion".[69] She would later recall that Shaw treated her "like an untutored blonde savage, and took no pains to conceal his opinion".[64] In the midst of her marriage to Shaw, she starred in We Who Are Young, a drama in which she played a woman who, against their employer's policy, marries her coworker.[70]

1940–1945: War years and film stardom

[edit]

In 1940, Turner appeared in her first musical film, Two Girls on Broadway, in which she received top billing over established co-stars Joan Blondell and George Murphy.[64] A remake of The Broadway Melody, the film was marketed as featuring Turner's "hottest, most daring role".[64] The following year, she had a lead role in her second musical, Ziegfeld Girl, opposite James Stewart, Judy Garland and Hedy Lamarr.[71] In the film, she portrayed Sheila Regan, an alcoholic aspiring actress based on Lillian Lorraine.[72][73] Ziegfeld Girl marked a personal and professional shift for Turner; she claimed it as the first role that got her "interested in acting",[74] and the studio, impressed by her performance, marketed the film as featuring her in "the best role of the biggest picture to be released by the industry's biggest company".[75] The film's high box-office returns elevated Turner's profitability, and MGM gave her a weekly salary raise to $1,500 as well as a personal makeup artist and trailer ($32,622 in 2023 dollars [43]).[76] After completing the film, Turner and co-star Garland remained lifelong friends, and lived in houses next to one another in the 1950s.[77]

Following the success of Ziegfeld Girl, Turner took a supporting role as an ingénue in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941) – a sanitized remake of the original pre-Code film from a decade earlier – remade as a Freudian-influenced horror film, opposite Spencer Tracy and Ingrid Bergman.[78] MGM had initially cast Turner in the lead, but Tracy specifically requested Bergman for the part. The studio recast Turner in the smaller role, though she was still given top billing.[79] While the film was financially successful at the box office,[80] Time magazine panned it, calling it "a pretentious resurrection of Robert Louis Stevenson's ghoulish classic ... As for Lana Turner, fully clad for a change, and the rest of the cast ... they are as wooden as their roles."[81]

Turner was then cast in the Western Honky Tonk (1941), the first of four films in which she would star opposite Clark Gable.[82] The Turner-Gable films' successes were often heightened by gossip-column rumors about a relationship between the two.[83] In January 1942, she began shooting her second picture with Gable, titled Somewhere I'll Find You;[84] however, the production was halted for several weeks after the death of Gable's wife, Carole Lombard, in a plane crash.[85] Meanwhile, the press continued to fuel rumors that Turner and Gable were romantic offscreen, which Turner vehemently denied.[86] "I adored Mr. Gable, but we were [just] friends", she later recalled. "When six o'clock came, he went his way and I went mine."[33] Her next project was Johnny Eager (1941), a violent mobster film in which she portrayed a socialite.[87][88] James Agee of Time magazine was critical of co-star Robert Taylor's performance and noted: "Turner is similarly handicapped: Metro has swathed her best assets in a toga, swears that she shall become an actress, or else. Under these adverse circumstances, stars Taylor and Turner are working under wraps."[89]

At the advent of US involvement in World War II, Turner's increasing prominence in Hollywood led to her becoming a popular pin-up girl,[90] and her image appeared painted on the noses of U.S. fighter planes, bearing the nickname "Tempest Turner".[91] In June 1942, she embarked on a 10-week war bond tour throughout the western United States with Gable.[92] During the tour, she began promising kisses to the highest war bond buyers; while selling bonds at the Pioneer Courthouse in Portland, Oregon, she sold a $5,000 bond to a man for two kisses,[93] and another to an elderly man for $50,000.[92] Arriving to sell bonds in her hometown of Wallace, Idaho, she was greeted with a banner that read "Welcome home, Lana", followed by a large celebration during which the mayor declared a holiday in her honor.[94] Upon completing the tour, Turner had sold $5.25 million in war bonds.[92] Throughout the war, Turner continued to make regular appearances at U.S. troop events and area bases, though she confided to friends that she found visiting the hospital wards of injured soldiers emotionally difficult.[95] During World War II, the Royal Canadian Air Force 427 Lion Squadron had been "adopted" by MGM. Many of the aircraft had dedications or nose art honoring MGM's stars. A Handley-Page Halifax bomber "London's Revenge" DK186 ZL L carried the name of Lana Turner into battle over Germany.[96]

In July 1942,[97] Turner met her second husband, actor-turned-restaurateur Joseph Stephen "Steve" Crane, at a dinner party in Los Angeles.[98] The two eloped to Las Vegas a week after they began dating.[99] The marriage was annulled by Turner four months later upon discovering that Crane's previous divorce had not yet been finalized.[100] After discovering she was pregnant in November 1942, Turner remarried Crane in Tijuana in March 1943.[97] During her early pregnancy, she filmed the comedy Marriage Is a Private Affair, in which she starred as a carefree woman struggling to balance her new life as a mother.[101] Though she wanted multiple children, Turner had Rh-negative blood, which caused fetal anemia and made it difficult to carry a child to term.[102][103] Turner was urged by doctors to undergo a therapeutic abortion to avoid potentially life-threatening complications, but she managed to carry the child to term. She gave birth to a daughter, Cheryl, on July 25, 1943. Turner's blood condition resulted in Cheryl being born with near-fatal erythroblastosis fetalis.[104][105]

Meanwhile, publicity over Turner's remarriage to Crane led MGM to play up her image as a sex symbol in the comedy Slightly Dangerous (1943), with Robert Young, Walter Brennan and Dame May Whitty, in which she portrayed a woman who moves to New York City and poses as the long-lost daughter of a millionaire.[106] Released in the midst of Turner's pregnancy, the film was financially successful[107] but received mixed reviews, with Bosley Crowther of The New York Times writing: "No less than four Metro writers must have racked their brains for all of five minutes to think up the rags-to-riches fable ... Indeed, there is cause for suspicion that they didn't even bother to think."[108] Critic Anita Loos praised Turner's performance in the film, writing: "Lana Turner typifies modern allure. She is the vamp of today as Theda Bara was of yesterday. However, she doesn't look like a vamp. She is far more deadly because she lets her audience relax."[109]

In August 1944, Turner divorced Crane, citing his gambling and unemployment as primary reasons.[110] Turner was among 250 film notables listed by the Hollywood Democratic Committee as supporting the re-election of Democratic Party incumbent President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the 1944 presidential election.[111][112] In 1945, she co-starred with Laraine Day and Susan Peters in Keep Your Powder Dry, a war drama about three disparate women who join the Women's Army Corps.[113] She was then cast as the female lead in Week-End at the Waldorf, a loose remake of Grand Hotel (1932) in which she portrayed a stenographer (a role originated by Joan Crawford).[114] The film was a box-office hit.[114][115]

1946–1948: Expansion to dramatic roles

[edit]

After the war, Turner was cast in a lead role opposite John Garfield in The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), a film noir based on James M. Cain's debut novel of the same name.[116] She portrayed Cora, an ambitious woman married to a stodgy, older owner of a roadside diner, who falls in love with a drifter and their desire to be together motivates them to murder her husband.[117] The classic film noir marked a turning point in Turner's career as her first femme fatale role.[118] Reviews of the film, including Turner's performance, were glowing, with Bosley Crowther of The New York Times writing it was "the role of her career".[119] Life magazine named the film its "Movie of the Week" in April 1946, and noted that both Turner and Garfield were "aptly cast" and "take over the screen, [creating] more fireworks than the Fourth of July".[120] Turner commented on her decision to take the role:

I finally got tired of making movies where all I did was walk across the screen and look pretty. I got a big chance to do some real acting in The Postman Always Rings Twice, and I'm not going to slip back if I can help it. I tried to persuade the studio to give me something different. But every time I went into my argument about how bad a picture was, they'd say, "well, it's making a fortune". That licked me.[121]

The Postman Always Rings Twice became a major box office success, which prompted the studio to take more risks on Turner, casting her outside of the glamorous sex-symbol roles for which she had come to be known.[121] In August 1946, it was announced she would replace Katharine Hepburn in the big-budget historical drama Green Dolphin Street (1947), a role for which she darkened her hair and lost 15 pounds.[121][122] The film was produced by Carey Wilson, who insisted on casting Turner based on her performance in The Postman Always Rings Twice. In the film, she portrayed the daughter of a wealthy patriarch who pursues a relationship with a man in love with her sister.[122] Turner later recalled she was surprised about replacing Hepburn, saying: "I'm about the most un-Hepburnish actress on the lot. But it was just what I wanted to do."[121] It was her first starring role that did not center on her looks. In an interview, Turner said: "I even go running around in the jungles of New Zealand in a dress that's filthy and ragged. I don't wear any make-up and my hair's a mess." Nevertheless, she insisted she would not give up her glamorous image.[121] In the midst of filming Green Dolphin Street, Turner began an affair with actor Tyrone Power,[123][124] whom she considered to be the love of her life.[125] She discovered she was pregnant with Power's child in the fall of 1947, but chose to have an abortion.[125][33] During this time, she also had romantic affairs with Frank Sinatra[126] and Howard Hughes, the latter of which lasted for 12 weeks in late 1946.[127]

Turner's next film was the romantic drama Cass Timberlane, in which she played a young woman in love with an older judge, a role for which Jennifer Jones, Vivien Leigh and Virginia Grey had also been considered.[128] As of early 1946, Turner was set for the role, but schedules with Green Dolphin Street almost prohibited her from taking it, and by late 1946, she was nearly recast.[129] Production of Cass Timberlane was exhausting for Turner, because it was shot in between retakes of Green Dolphin Street.[130] Cass Timberlane earned Turner favorable reviews, with Variety noting: "Turner is the surprise of the picture via her top performance thespically. In a role that allows her the gamut from tomboy to the pangs of childbirth and from being another man's woman to remorseful wife, she seldom fails to acquit herself creditably."[131]

In August 1947, immediately upon completion of Cass Timberlane, Turner agreed to appear as the female lead in the World War II-set romantic drama Homecoming (1948), in which she was again paired with Clark Gable, portraying a female army lieutenant who falls in love with an American surgeon (Gable).[132] She was the studio's first choice for the role, but it was reluctant to offer her the part, considering her overbooked schedule.[132] Homecoming was well received by audiences, and Turner and Gable were nicknamed "the team that generates steam".[133] By this period, Turner was at the zenith of her film career, and was not only MGM's most popular star, but also one of the ten highest-paid women in the United States, with annual earnings of $226,000.[114][134]

1948–1952: Studio rebranding and personal struggles

[edit]In late 1947, Turner was cast as Lady de Winter in The Three Musketeers, her first Technicolor film.[135][136] Around this time, she began dating Henry J. "Bob" Topping Jr., a millionaire socialite and brother of New York Yankees owner Dan Topping, and a grandson of tin-plate magnate Daniel G. Reid.[97] Topping proposed to her at the 21 Club in New York City by dropping a diamond ring into her martini, and they married shortly after in April 1948 at the Topping family mansion in Greenwich, Connecticut.[137][138] Turner's wedding celebrations interfered with her filming schedule for The Three Musketeers, and she arrived to the set three days late.[139][140] Studio head Louis B. Mayer threatened to suspend her contract, but Turner managed to leverage her box-office draw with MGM to negotiate an expansion of her role in the film, as well as a salary increase amounting to $5,000 per week ($68,227 in 2023 dollars [43]).[141][142] The Three Musketeers went on to become a box-office success, earning $4.5 million ($61,403,875 in 2023 dollars [43]),[143] but Turner's contract was put on temporary suspension by Mayer after production finished.[144] After the release of The Three Musketeers, Turner discovered she was pregnant; in early 1949, she went into premature labor and gave birth to a stillborn baby boy in New York City.[145]

In 1949, Turner was to star in A Life of Her Own (1950), a George Cukor-directed drama about a woman who aspires to be a model in New York City. The project was shelved for several months, and Turner told journalists in December 1949: "Everybody agrees that the script is still a pile of junk. I'm anxious to get started. By the time this one comes out, it will be almost three years since I was last on the screen, in The Three Musketeers. I don't think it's healthy to stay off the screen that long."[146] Although unenthusiastic about the screenplay, Turner agreed to appear in the film after executives promised her suspension would be lifted upon doing so.[144] A Life of Her Own was among the least successful of Cukor's films, receiving unfavorable reviews and low box-office sales.[147] On May 24, 1950, Turner left her handprints and footprints in cement in front of Grauman's Chinese Theatre.[148]

In response to the poor reception for A Life of Her Own, MGM attempted to rebrand Turner by casting her in musicals.[149] The first, Mr. Imperium, released in March 1951, was a box-office flop, and had Turner starring as an American woman who is wooed by a European prince.[150] "The script was stupid," she recalled. "I fought against doing the picture, but I lost."[151] It earned her unfavorable reviews, with one critic from the St. Petersburg Times writing: "Without Lana Turner, Mr. Imperium ... would be a better picture."[152]

During this period, Turner's personal finances were in disarray, and she was facing bankruptcy.[153] Suffering from depression over her career and financial problems, she attempted suicide in September 1951 by slitting her wrists in a locked bathroom.[154] She was saved by her business manager, Benton Cole, who broke down the bathroom door and called emergency medical services.[154] The following year, she began filming her second musical, The Merry Widow. During the shoot, Turner began an affair with her co-star Fernando Lamas, which ended after Lamas physically assaulted her; the incident also caused Lamas to lose his MGM contract upon the production's completion.[155] The Merry Widow proved more commercially successful than Turner's previous musical, Mr. Imperium, despite receiving unfavorable critical reviews.[156]

Turner's next project was opposite Kirk Douglas in Vincente Minnelli's The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), a drama focusing on the rise and fall of a Hollywood film mogul, in which Turner portrayed an alcoholic movie star.[157] The Bad and the Beautiful was both a critical and commercial success, and earned her favorable reviews.[158] A little over a week before the film's release in December 1952, Turner divorced her third husband, Bob Topping.[97] She later claimed Topping's drinking problem and excessive gambling as her impetus for the divorce.[159] Her next film project was Latin Lovers (1953), a romantic musical in which Lamas had originally been cast. He was replaced by Ricardo Montalbán.[160]

1953–1957: MGM departure and film resurgence

[edit]In the spring of 1953, Turner relocated to Europe for 18 months to make two films under a tax credit for American productions shot abroad.[161] The films were Flame and the Flesh, in which she portrayed a manipulative woman who takes advantage of a musician, and Betrayed, an espionage thriller set in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands; the latter marked Turner's fourth and final film appearance opposite Clark Gable.[162] In The New York Times, Bosley Crowther wrote of Betrayed: "By the time this picture gets around to figuring out whether the betrayer is Miss Turner or Mr. Mature, it has taken the audience through such a lengthy and tedious amount of detail that it has not only frayed all possible tension but it has aggravated patience as well."[163] Upon returning to the United States in September 1953, Turner married actor Lex Barker,[97] whom she had been dating since their first meeting at a party held by Marion Davies in the summer of 1952.[164]

In 1955, MGM's new studio head Dore Schary had Turner star as a pagan temptress in the Biblical epic The Prodigal (1955), her first CinemaScope feature.[165][166] She was reluctant to appear in the film because of the character's scanty, "atrocious" costumes and "stupid" lines, and during the shoot struggled to get along with co-star Edmund Purdom, whom she later described as "a young man with a remarkably high opinion of himself".[167] Variety deemed the film "a big-scale spectacle ...End result of all this flamboyant polish, however, is only fair entertainment."[168] Turner was next cast in John Farrow's The Sea Chase (1955), an adventure film starring John Wayne, in which she portrayed a femme fatale spy aboard a ship.[169] The film, released one month after The Prodigal, was a commercial success.[170]

MGM then gave Turner the titular role of Diane de Poitiers in the period drama Diane (1956), which had originally been optioned by the studio in the 1930s for Greta Garbo.[171] After completing Diane, Turner was loaned to 20th Century-Fox to headline The Rains of Ranchipur (1955), a remake of The Rains Came (1939), playing the wife of an aristocrat in the British Raj opposite Richard Burton.[172][173] The production was rushed to accommodate a Christmas release and was completed in only three months, but it received unfavorable reviews from critics.[174] Meanwhile, Diane was given a test screening in late December 1955, and was met with poor response from audiences.[174] Though an elaborate marketing campaign was crafted to promote the film, it was a box-office flop,[175] and MGM announced in February 1956 that it was opting not to renew Turner's contract.[176] Turner gleefully told a reporter at the time that she was "walking around in a daze. I've been sprung. After 18 years at MGM, I'm a free agent ...I used to go on a bended knee to the front office and say, please give me a decent story. I'll work for nothing, just give me a good story. So what happened? The last time I begged for a good story they gave me The Prodigal."[177] At the time of her contract termination, Turner's films had earned the studio more than $50 million.[177]

In 1956, Turner discovered she was pregnant with Barker's child, but gave birth to a stillborn baby girl seven months into the pregnancy.[178] In July 1957,[97] she filed for divorce from Barker after her daughter Cheryl alleged that he had regularly molested and raped her over the course of their marriage.[179][180] According to Cheryl, Turner confronted Barker before forcing him out of their home at gunpoint.[181] Weeks after her divorce, Turner began filming 20th Century-Fox's Peyton Place, in which she had been cast in the lead role of Constance MacKenzie, a New England mother struggling to maintain a relationship with her teenage daughter.[182] The film, directed by Mark Robson, was adapted from Grace Metalious' best-selling novel of the same name.[183] Released in December 1957, Peyton Place was a major blockbuster success, which worked in Turner's favor as she had agreed to take a percentage of the film's overall earnings instead of a salary.[184] She also received critical acclaim, with Variety noting that "Turner looks elegant" and "registers strongly",[185] and, for the first and only time, she was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress.[186] Though grateful for the nomination, Turner would later state that she felt it was not "one of my better roles".[187]

1958–1959: Johnny Stompanato homicide scandal

[edit]

In January 1958, Paramount Pictures released The Lady Takes a Flyer, a romantic comedy in which Turner portrayed a female pilot.[188] While shooting the film the previous spring, she had begun receiving phone calls and flowers on the set from mobster Johnny Stompanato, using the name "John Steele".[189] Stompanato had close ties to the Los Angeles underworld and gangster Mickey Cohen, which he feared would dissuade her from dating him.[190] He pursued Turner aggressively, sending her various gifts.[191] Turner was "thoroughly intrigued" and began casually dating him.[192] After a friend informed her of who Stompanato actually was, she confronted him and tried to break off the affair.[193] Stompanato was not easily deterred, and over the course of the following year, they carried on a relationship filled with violent arguments, physical abuse and repeated reconciliations.[194][195] Turner would also claim that on one occasion he drugged her and took nude photographs of her while unconscious, potentially to use as blackmail.[196]

In September 1957, Stompanato visited Turner in London, where she was filming Another Time, Another Place, co-starring Sean Connery.[197] Their meeting was initially happy, but they soon began fighting. Stompanato became suspicious when Turner would not allow him to visit the set and, during one fight, he violently choked her.[198] To avoid further confrontation, Turner and her makeup artist, Del Armstrong, called Scotland Yard in order to have Stompanato deported.[199][200] Stompanato got wind of the plan and showed up on the set with a gun, threatening her and Connery.[201] Connery answered by grabbing the gun out of Stompanato's hand and twisting his wrist, causing him to run off the set.[202] Turner and Armstrong later returned with two Scotland Yard detectives to the rented house where she and Stompanato were staying. The detectives advised Stompanato to leave and escorted him out of the house and to the airport, where he boarded a plane back to the U.S.[203]

On the evening of March 26, 1958, Turner attended the Academy Awards to observe her nomination for Peyton Place and present the award for Best Supporting Actor.[204] Stompanato, angered that he did not attend with her, awaited her return home that evening, whereupon he physically assaulted her.[205] Around 8:00 p.m. on Friday, April 4, Stompanato arrived at Turner's rented home at 730 North Bedford Drive in Beverly Hills.[206][207] The two began arguing heatedly in the bedroom, during which Stompanato threatened to kill Turner, her daughter Cheryl and her mother.[194] Fearing that her mother's life was in danger, Cheryl – who had been watching television in an adjacent room – grabbed a kitchen knife and ran to Turner's defense.[208]

According to testimony provided by Turner, Stompanato died at the scene when Cheryl, who had been listening to the couple's fight behind the closed door, stabbed Stompanato in the stomach when Turner attempted to usher him out of the bedroom.[209] Turner testified that she initially believed Cheryl had punched him, but realized Stompanato had been stabbed when he collapsed and she saw blood on his shirt.[209]

Because of Turner's fame and the fact that the killing involved her teenage daughter, the case quickly became a media sensation.[210] More than 100 reporters and journalists attended the April 12, 1958 inquest, described by attendees as "near-riotous".[211] After four hours of testimony and approximately 25 minutes of deliberation, the jury deemed the killing a justifiable homicide.[212][213] Cheryl remained a temporary ward of the court until April 24, when a juvenile court hearing was held, during which the judge expressed concerns over her receiving "proper parental supervision".[213] She was ultimately released to the care of her grandmother, and was ordered to regularly visit a psychiatrist alongside her parents.[213]

Though Turner and her daughter were exonerated of any wrongdoing, public opinion on the event was varied, with numerous publications intimating that Turner's testimony at the inquest was a performance; Life magazine published a photo of Turner testifying in court along with stills of her in courtroom scenes from three of her films.[214] The scandal also coincided with the release of Another Time, Another Place, and the film was met with poor box-office receipts and a lackluster critical response.[215] Stompanato's family sought a wrongful death suit of $750,000 in damages against both Turner and her ex-husband, Steve Crane. In the suit, Stompanato's son alleged that Turner had been responsible for his death, and that her daughter had taken the blame.[216] The suit was settled out of court for a reported $20,000 in May 1962.[217] A 1962 novel by Harold Robbins entitled Where Love Has Gone and its subsequent film adaptation were inspired by the event.[218]

1959–1965: Financial successes

[edit]In the wake of negative publicity related to Stompanato's death, Turner accepted the lead role in Ross Hunter's remake of Imitation of Life (1959) under the direction of Douglas Sirk.[219] She portrayed a struggling stage actress who makes personal sacrifices to further her career.[220] The production was difficult for Turner given the recent events of her personal life, and she suffered a panic attack on the first day of filming.[221] Her co-star Juanita Moore recalled that Turner cried for three days after filming a scene in which Moore's character dies.[222] When she returned to the set, "her face was so swollen, she couldn't work", Moore said.[223]

Released in the spring of 1959, Imitation of Life was among the year's biggest successes, and the biggest of Turner's career; by opting to receive 50% of the film's earnings rather than receiving a salary, she earned more than two million dollars.[224] Imitation of Life made more than $50 million in box office receipts.[225] Reviews were mixed,[226] although Variety praised her performance, writing: "Turner plays a character of changing moods, and her changes are remarkably effective, as she blends love and understanding, sincerity and ambition. The growth of maturity is reflected neatly in her distinguished portrayal."[227] Critics and audiences could not help noticing that the plots of Peyton Place and Imitation of Life both seemed to mirror certain parts of Turner's private life, resulting in comparisons she found painful.[228] Both films depicted the troubled, complicated relationship between a single mother and her teenage daughter.[229] During this time, Turner's daughter Cheryl privately came out as a lesbian to her parents, who were both supportive of her.[212] Despite this, Cheryl ran away from home multiple times and the press wrote about her rebelliousness.[224][230] Worried she was still suffering from the trauma of Stompanato's death, Turner sent Cheryl to the Institute of Living in Hartford, Connecticut.[231]

Shortly before the release of Imitation of Life in the spring of 1959, Turner was cast in a lead role in Otto Preminger's Anatomy of a Murder, but walked off the set over a wardrobe disagreement, effectively dropping out of the production.[232][233] She was replaced by Lee Remick.[234] Instead, Turner took a lead role as a disturbed socialite in the film noir Portrait in Black (1960) opposite Anthony Quinn and Sandra Dee, which was a box-office success despite bad reviews.[235][236] Ray Duncan of the Independent Star-News wrote that Turner "suffers prettily through it all, like a fashion model with a tight-fitting shoe".[237]

In November 1960, Turner married her fifth husband, Frederick "Fred" May, a rancher and member of the May department-store family whom she had met at a beach party in Malibu shortly after filming Imitation of Life.[238] Turner moved in with him on his ranch in Chino, California, where the two took care of horses and other animals.[239][217] The following year, she made her final film at MGM with Bob Hope in Bachelor in Paradise (1961), a romantic comedy about an investigative writer (Hope) working on a book about the wives of a lavish California community; the film received a mostly positive critical reception.[240] Upon completing filming, Turner collected the remaining $92,000 from her pension fund with MGM.[241] The same year, she starred in By Love Possessed (1961), based on a bestselling novel by James Gould Cozzens.[242] The film became the first in-flight movie to be shown on a regular basis on a scheduled airline flight when TWA showed it to its first-class passengers.[243]

In mid-1962, Turner filmed Who's Got the Action?, a comedy in which she portrayed the wife of a gambling addict opposite Dean Martin.[244] In September of that year,[245] Turner and May separated, divorcing shortly after in October.[97] They remained friends throughout her later life.[33] In 1965, she met Hollywood producer and businessman Robert Eaton, who was ten years her junior, through business associates.[246] The two married in June of that year at his family's home in Arlington County, Virginia.[247]

1966–1985: Later films, television and theatre

[edit]

In 1966, Turner had her last major starring role in the courtroom drama film Madame X, based on the 1904 play by Alexandre Bisson, in which Turner portrayed a lower-class woman who marries into a wealthy family.[248] A review in the Chicago Tribune praised her performance, noting: "when she takes the stand in the final (with Keir Dullea) courtroom scene, her face resembling a dust bowl victory garden, it's the most devastating denouement since Barbara Fritchie poked her head out the window."[249] Kaspar Monahan of the Pittsburgh Press lauded her performance, writing: "Her performance, I think, is far and away her very best, even rating Oscar consideration in next year's Academy Award race, unless the culture snobs gang up against her."[250] The role earned Turner a David di Donatello Golden Plaque Award for Best Foreign Actress that year.[251]

In late 1968, she began filming the low-budget thriller The Big Cube, in which she portrayed a glamorous heiress being dosed with LSD by her stepdaughter in hopes of driving her insane and receiving the family estate.[252] One critic deemed Turner's acting in the film "strained and amateurish", and declared it "one of her poorest performances".[253] In April 1969,[254] Turner filed for divorce from Eaton after four years of marriage upon discovering he had been unfaithful to her.[255] Weeks later, on May 9, 1969, she married Ronald Pellar, a nightclub hypnotist whom she had met at a Los Angeles disco.[256] According to Turner, Pellar (also known as Ronald Dante or Dr. Dante)[257] falsely claimed to have been raised in Singapore and to have a Ph.D. in psychology.[258]

With few film offers coming in, Turner signed on to appear in the television series Harold Robbins' The Survivors.[259] Premiering in September 1969, the series was given a major national marketing campaign, with billboards featuring life-sized images of Turner.[260] Despite ABC's extensive publicity campaign and the presence of other big-name stars, the program fared badly, and it was canceled halfway into the season after a 15-week run in 1970.[260] Meanwhile, after six months of marriage, Turner discovered Pellar had stolen $35,000 she had given him for an investment.[261] In addition, she later accused him of stealing $100,000 worth of jewelry from her.[261] Pellar denied the accusations and no charges were filed against him.[262] She filed for divorce in January 1970,[97] after which she claimed to be celibate for the remainder of her life.[263][264] Turner married a total of eight times to seven different husbands,[212] and later famously said: "My goal was to have one husband and seven children, but it turned out to be the other way around."[102]

Turner returned to feature films with a lead role in the 1974 British horror film Persecution, in which she played a disturbed wealthy woman tormenting her son.[265] Variety noted of her performance: "Under the circumstances, Turner's performance as Carrie, the perverted dame of the English manor, has reasonable poise."[266] In April 1975, Turner spoke at a retrospective gala in New York City examining her career, which was attended by Andy Warhol, Sylvia Miles, Rex Reed and numerous fans.[267] Her next film was Bittersweet Love (1976), a romantic comedy in which she portrayed the mother of a woman who unwittingly marries her half-brother.[268] Lawrence Van Gelder of The New York Times wrote that the film served "as a reminder that Miss Turner was never one of our subtler actresses".[269]

In the early 1970s, Turner transitioned to theater, beginning with a production of Forty Carats, which toured various East Coast cities in 1971.[270] A review in The Philadelphia Inquirer noted: "Miss Turner always could wear clothes well, and her Forty Carats is a fashion show in the guise of a frothy, little comedy. It wasn't much of a play even when Julie Harris was doing it, and it all but disappears under the old-time Hollywood glamor of Miss Turner's star presence."[271] In 1975, Turner gave a single performance as Jessica Poole in The Pleasure of His Company opposite Louis Jourdan at the Arlington Park Theater in Chicago.[272] From 1976 to 1978, she starred in a touring production of Bell, Book and Candle, playing Gillian Holroyd.[273][274] Critic Elaine Matas noted of a 1977 performance that Turner was "brilliant" and "the bright spot in an otherwise mediocre play".[275] In the fall of 1978, she appeared in a Chicago production of Divorce Me, Darling, an original play in which she portrayed a San Francisco divorce attorney.[276] During rehearsals, a stagehand told reporters that Turner was "the hardest working broad I've known".[277] Richard Christiansen of the Chicago Tribune praised her performance, writing that, "though she is still a very nervous and inexpert actress, she is giving by far her most winning performance".[276]

Between 1979 and 1980, Turner returned to theater, appearing in Murder Among Friends, a murder-mystery play that showed in various U.S. cities.[278][279][280] During this time, Turner was in the midst of a self-described "downhill slide".[281] She was suffering from an alcohol addiction that had begun in the late 1950s,[270] was missing performances and weighed only 95 pounds (43 kg).[281] In 1980, Turner made her final feature film appearance, in the comedy horror film Witches' Brew, alongside Teri Garr. The same year, she had what she referred to as a "religious awakening", and again began practicing her Catholic faith.[282][283] On October 25, 1981, the National Film Society presented Turner with an Artistry in Cinema award.[284] In December 1981, it was announced that Turner would appear as the mysterious Jacqueline Perrault in an episode of Falcon Crest,[285] marking her first television role in 12 years.[286] Her appearance was a ratings success, and her character returned for an additional five episodes.[287]

In January 1982, Turner reprised her role in Murder Among Friends, which toured throughout the U.S. that year; paired with Bob Fosse's Dancin', the play earned a combined gross of $400,000 during one week at Pittsburgh's Heinz Hall in June 1982.[288] In September, Turner released an autobiography entitled Lana: The Lady, the Legend, the Truth.[289] She subsequently guest-starred on an episode of The Love Boat in 1985,[290] which marked her final on-screen appearance.

Death

[edit]Turner was a regular drinker[270] and cigarette smoker for most of her life.[291][292] During her contract with MGM, photographs that showed her holding cigarettes had to be airbrushed at the studio's request in an effort to conceal her smoking.[291] In her early sixties Turner stopped drinking to preserve her health,[283] but she was unable to quit smoking.[258] She was diagnosed with throat cancer in the spring of 1992.[293][294] In a press release, she stated that the cancer had been detected early and had not damaged her vocal cords or larynx.[294] She underwent exploratory surgery to remove the cancer,[294] but it had metastasized to her jaw and lungs.[295] After undergoing radiation therapy,[292] Turner announced that she was in full remission in early 1993.[296] The cancer was found to have returned in July 1994.[297]

In September 1994, Turner made her final public appearance at the San Sebastián International Film Festival in Spain to accept a Lifetime Achievement Award,[298] and used a wheelchair for much of the event.[292] She died nine months later at the age of 74 on June 29, 1995, of complications from the cancer, at her home in Century City, Los Angeles, with her daughter by her side.[212][299] According to Cheryl, Turner's death was a "total shock", as she had appeared to be in better health and had recently completed seven weeks of radiation therapy.[264]

Turner's remains were cremated and given to Cheryl. Multiple accounts have the ashes still in Cheryl's possession, while other accounts say the ashes were scattered in the ocean, but which ocean and location varies by the sources.[300][301] Cheryl and her partner Joyce LeRoy, whom Turner said she accepted "as a second daughter",[302] inherited some of Turner's personal effects and $50,000 in Turner's will. Her estate was estimated in court documents to be worth $1.7 million. Turner left the majority of her estate to her maid, Carmen Lopez Cruz, who had been her companion for 45 years and caregiver during her final illness.[303] Cheryl challenged the will, and Cruz said that the majority of the estate was consumed by probate costs, legal fees and medical expenses.[304]

Public and screen persona

[edit]Despite the reams of copy that have been written about me, even the supposedly private Lana, the press has never had any sense of who I am; they've even missed my humor, my love of gaiety and color ... Humor has been the balm of my life, but it's been reserved for those closest to me.

– Turner on her representation in press[305]

When Turner was discovered, MGM executive Mervyn LeRoy envisioned her as a replacement for the recently deceased Jean Harlow and began developing her image as a sex symbol.[306] In They Won't Forget (1937) and Love Finds Andy Hardy (1938), she embodied an "innocent sexuality" portraying ingénues.[307] Film historian Jeanine Basinger notes that she "represented the girl who'd rather sit on the diving board to show off her figure than get wet in the water ... the girl who'd rather kiss than kibbitz".[52] In her early films, Turner did not color her auburn hair—see Dancing Co-Ed (1939), in which she was billed "the red-headed sensation who brought "it" back to the screen".[308] 1941's Ziegfeld Girl was the first film to showcase Turner with platinum blonde hair, which she wore for much of the remainder of her life and for which she came to be known.[309]

После первого брака Тернер в 1940 году обозреватель Луэлла Парсонс написала: «Если Лана Тернер будет вести себя прилично и не впадет в ярость, она займет первое место в кино. Она самая гламурная актриса со времен Джин Харлоу». [310] Она также сравнила ее с Кларой Боу , добавив: «Они оба, доверчивые и милые, используют свое сердце, а не голову. Лана… всегда действовала поспешно и больше руководствовалась собственными идеями, чем какими-либо достижениями, которые давала любая студия». ее." [69] К середине 1940-х годов Тернер была замужем и трижды развелась, родила дочь Шерил и имела множество публичных романов. [224] [307] Однако ее образ в фильме 1946 года «Почтальон всегда звонит дважды» ознаменовал отход от ее экранного образа строго секс-символа к полноценной роковой женщине . [307]

К 1950-м годам и критики, и зрители начали отмечать параллели между непростой личной жизнью Тернер и ролями, которые она играла. [311] Сходство было наиболее очевидным в фильмах «Пейтон Плейс» и «Имитация жизни» , в которых Тернер изображала одиноких матерей, изо всех сил пытающихся сохранить отношения со своими дочерьми-подростками. [312] Киновед Ричард Дайер приводит Тернер в качестве примера одной из первых звезд Голливуда, чья публичная личная жизнь заметно повлияла на их карьеру: «Ее карьера отмечена необычайно, даже поразительно высокой степенью взаимопроникновения между ее публично доступной личной жизнью и ее фильмами. ... ее транспортные средства не только обставляют персонажей и ситуации в соответствии с ее закадровым образом, но и часто происшествия в них перекликаются с происшествиями в ее жизни, так что к концу ее карьеры такие фильмы, как «Пейтон Плейс» , «Имитация жизни » , «Мадам Икс» и «У любви много лиц» местами кажутся простыми иллюстрациями из ее жизни». [313]

Бейсингер разделяет аналогичные чувства, отмечая, что Тернер часто «играла только роли, которые символизировали то, что публика знала — или думала, что знала — о ее жизни из заголовков, которые она делала как личность, а не как персонаж фильма… Ее личность» стал ее личностью». [314] Вдобавок Бейсингер считает Тернер первой популярной женщиной-звездой, которая «открыто взяла на себя мужскую прерогативу», публично предавшись романам и интрижкам, что, в свою очередь, подогрело шумиху вокруг нее. [315] Киновед Джессика Хоуп Джордан считает Тернер «имплозией» как «реального образа, так и звездного образа» и предполагает, что она использовала один, чтобы замаскировать другой, тем самым сделав ее представительницей «настоящей роковой женщины». [316] Обозреватель Дороти Килгаллен отметила пересечение жизни Тернер и экранного образа в начале своей карьеры, написав в 1946 году:

Лана Тернер — суперзвезда по многим причинам, но главным образом потому, что за кадром она такая же, как и на экране. Некоторые звезды — магнитные ослепители на целлулоиде и обычные, практичные мелочи в поло в личной жизни. Не то что Лана. Никто из тех, кто обожал ее в кино, не был бы разочарован, встретив ее во плоти. Мякоть та же самая. Биография столь же красочна, как и любой сюжет, который она когда-либо разыгрывала на экране. Одежда, которую она носит, такая же, как та, в которой вы платите, чтобы увидеть ее в субботу вечером в « Бижу» . Физическое очарование так же тяжело, когда она смотрит на метрдотеля, как и когда она смотрит на героя. [317]

Историки называют Тернер одной из самых гламурных кинозвезд всех времен, и эта ассоциация возникла еще при ее жизни. [318] [319] [320] и после ее смерти. [186] Комментируя свой имидж, она однажды сказала журналисту: «Отказаться от гламура — все равно, что отказаться от своей личности. Это имидж, над созданием и сохранением которого я слишком много работала». [4] Майкл Гордон , снявший Тернер в фильме «Портрет в черном» , вспоминал ее как «очень талантливую актрису, чья главная надежность заключалась в том, что я считал обедневшим вкусом… Лана не была дурой, и она давала мне замечательные объяснения, почему ей следует носить кулон». Серьги не имели никакого отношения к роли, но были связаны с ее особым имиджем». [321]

По словам ее дочери, одержимое внимание Тернер к деталям часто приводило к тому, что портные выбегали из дома во время примерки платья. [322] Независимо от обстановки, Тернер также позаботилась о том, чтобы она всегда была «готова к съемке», носила украшения и макияж, даже когда бездельничала в спортивных штанах. [323] Тернер часто покупала туфли своих любимых стилей во всех доступных цветах, накопив за один раз 698 пар. [324] Она отдавала предпочтение дизайнерам Сальваторе Феррагамо , Жану Луи , Хелен Роуз и Нолану Миллеру . [322] [325] Историки кино Джо Морелла и Эдвард Эпштейн заметили, что, в отличие от многих женщин-звезд, Тернер «не вызывала возмущения со стороны поклонниц», и что в последующие годы женщины составляли большую часть ее фанатов. [326] Тернер сохраняла свой гламурный имидж до конца своей карьеры; Обзор фильма 1966 года охарактеризовал ее как «блеск и гламур Голливуда». [4] Хотя она постоянно поддерживала свой гламурный образ, она также открыто заявляла о своей преданности актерскому мастерству. [121] и заслужил репутацию разностороннего и трудолюбивого исполнителя. [11] Она была поклонницей Бетт Дэвис , которую называла своей любимой актрисой. [218]

Наследие

[ редактировать ]

Историки отметили Тернер как секс-символ, популярной культуры. икону [4] [314] и «символ воплощенной американской мечты … Благодаря ей быть обнаруженным у автомата с газировкой стало почти таким же заветным идеалом, как рождение в бревенчатой хижине ». [4] Критик Леонард Малтин отметил в 2005 году, что Тернер «пришла к кристаллизации роскошных высот, на которые шоу-бизнес может привести девушку из маленького городка, а также его самые темные, самые трагические и нарциссические глубины». [327] Ученые также называют ее иконой гея из-за ее образа дивы и победы над личными трудностями. [328] Хотя дискуссии вокруг Тёрнер в основном основывались на ее культурной принадлежности, ее карьера проводилась мало научных исследований. [329] и мнение о ее наследии как актрисы разделили критиков. После смерти Тернер Джон Апдайк написал в The New Yorker , что она «была выцветшим произведением старины, старомодной гламурной королевой, чьи пятьдесят четыре фильма за четыре десятилетия ретроспективно не составили многого ... Как исполнительница, она была чисто студийным продуктом». [330]

Защитники актерских способностей Тернера, такие как Джессика Хоуп Джордан. [331] и Джеймс Роберт Пэриш , [332] процитируйте ее выступление в фильме «Почтальон всегда звонит дважды» как аргумент в пользу ценности ее работы. Роль Тернер в фильме также привела к тому, что в критических кругах ее часто ассоциировали с нуаром и архетипом роковой женщины. [333] [334] [335] В ретроспективе своей карьеры «Фильмы в обзоре» 1973 года Тернер была названа «мастером кинотехники и трудолюбивым мастером». [336] Джанин Бейсингер также поддерживала актерскую игру Тернер, написав о ее игре в фильме «Плохие и красивые» : «Ни одна из секс-символов, рекламируемых как актрисы, — ни Хейворт , ни Гарднер , ни Тейлор , ни Монро — никогда не давала такой прекрасной игры». [337]

Из-за пересечения громкой, гламурной личности Тернер и легендарной, часто беспокойной личной жизни, она участвует в критических дискуссиях о голливудской студийной системе , особенно о том, как она извлекает выгоду из личных страданий звезд. [329] Бейсингер считает ее «воплощением голливудской славы, созданной машинами». [338] Тернер также упоминался в научных дискуссиях о женской сексуальности. [339]

Тернер изображался и упоминался во многих произведениях литературы, кино, музыки и искусства. Она была героем стихотворения Фрэнка О'Хары «Лана Тернер рухнула» . [340] и был изображен второстепенным персонажем в Джеймса Эллроя романе «Секреты Лос-Анджелеса» (1990). [341] Убийство Стомпанато и его последствия также легли в основу Гарольда Роббинса романа «Куда ушла любовь» (1962). [218] В популярной музыке Тернер упоминается в песнях, записанных Ниной Симон. [342] и Фрэнк Синатра , [343] и был источником сценического псевдонима певицы и автора песен Ланы Дель Рей . [344] [345] В 2002 году художница Элой Торрес включила Тернер в фреску на открытом воздухе «Портрет Голливуда» , нарисованную в аудитории средней школы Голливуда , ее альма-матер. [346] У Тернера есть звезда на Голливудской Аллее славы на Голливудском бульваре, 6241. [11] В 2012 году Комплекс назвал ее восьмой самой скандально известной актрисой всех времен. [347]

Фильмография и титры

[ редактировать ]Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Тернер произнесла свое имя LAH -nə , [1] [2] и отметила свою неприязнь к альтернативному произношению LAN -ə ( / ˈ l æ n ə / ). В интервью 1982 года Джоан Риверс спросила Тернер, как она предпочитает произносить свое имя, и она пошутила: «Пожалуйста, если ты скажешь «Лан-а», я убью тебя». [3]

- ↑ Некоторые источники утверждают, что настоящее имя Тернер — Джулия Джин Милдред Фрэнсис Тернер. Однако Тернер отмечает в своей автобиографии, что в ее свидетельстве о рождении в качестве официального имени при рождении указана Джулия Джин Тернер. [8] Она пишет, что позже, после обращения в католицизм, приняла вторые имена Милдред и Фрэнсис (имена святых, а также имя и второе имя ее матери). [9]

- ^ Некоторые источники (включая San Francisco Chronicle [10] и Los Angeles Times ) серия «Голливудская аллея славы» [11] ошибочно указала год ее рождения как 1920. Однако в своих мемуарах Тернер указала, что в ее свидетельстве о рождении указан 1921 год. [8] и ее дочь снова подтвердила этот год своего рождения в 2008 году. [12]

- ↑ Согласно официальному сайту города Уоллес, дом Тернеров в Уоллесе находился по адресу 217 Bank Street, непосредственно к западу от центра города Уоллес. Дом расположен в историческом районе Уоллеса, который внесен в Национальный реестр исторических мест (OMB № 1024-0018). [19]

- ↑ В статье, опубликованной в Los Angeles Times в 1995 году после смерти Тернер, рассказывается о различных пересказах ее открытия и отмечается их статус легенд шоу-бизнеса. В документальном фильме 2001 года о Тернер ее открытие названо «самой легендарной историей открытия звезд» в Голливуде. [37] Тернер отвергла широко распространенную версию о том, что событие произошло в аптеке Шваба, настаивая на том, что она встретила Уильяма Р. Вилкерсона в солодовом магазине Top Hat, когда пила кока-колу. [38]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Бейсингер 1976 , с. 24.

- ^ Буш 1940 , с. 65.

- ↑ Тернер, Лана (28 сентября 1982 г.). «Джоан Риверс берет интервью у Ланы Тернер». Вечернее шоу (интервью). Беседовала Джоан Риверс . НБК.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Филдс 2007 , с. 109.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 65.

- ^ « Лана Тернер теперь официальна» . Евгений Регистр-охранник . Юджин, ИЛИ: ВВЕРХ. 7 мая 1950 г. с. 6D – через Новости Google.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Сквайр, Нэнси Уинслоу (май 1943 г.). «Странная история Ланы Тернер» . Современный экран . п. 32. ISSN 0026-8429 – в Интернет-архиве.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Тернер 1982 , с. 9.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Тернер 1982 , с. 14.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Сотрудники San Francisco Chronicle (3 июля 1995 г.). «Редакционная статья – Лана Тернер: 1920–1995» . Хроники Сан-Франциско . Проверено 28 июля 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Сотрудники Los Angeles Times (30 июня 1995 г.). «Лана Тернер» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс . Голливудская звездная прогулка . Проверено 23 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Крейн и Де Серп 2008 , с. 16.

- ^ Фернандес, Чарльз (3 июля 1995 г.). «Звезда родилась в Айдахо; люди Уоллеса помнят ранние годы Тернер. Ее семья переехала в Сан-Франциско, когда ей было 6 лет» . Льюистон Трибьюн . Льюистон, Айдахо . Проверено 25 июня 2017 г.

- ^ Гревер, Бриндли (15 мая 1941 г.). «Лана Тернер, родилась в Уоллесе, штат Айдахо, двадцать лет назад, теперь звезда» . Спокан Дейли Кроникл . Спокан, Вашингтон. п. 16 – через Новости Google.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , стр. 10–11.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , стр. 9–10.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 10.

- ^ Буэннеке, Трой Д. (1991). «Берк, Айдахо, 1884–1925: Взлет и падение горнодобывающего сообщества». Айдахо Вчера . Том. 35–36. Историческое общество Айдахо. п. 26. ISSN 0019-1264 .

- ^ Марш, Грег. «Лана Тернер жила в историческом Уоллесе» . Город Уоллес, штат Айдахо . Архивировано из оригинала 13 декабря 2007 года . Проверено 26 августа 2017 г.

- ^ Бамонт и Джейкобсон 2017 , с. 161.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Бейсингер 1976 , с. 19.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Сотрудники Los Angeles Times (30 июня 1995 г.). «Лана Тернер, гламурная звезда 50 фильмов, умерла в 75 лет» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 11 августа 2016 года.

- ^ Уэйн 2003 , с. 164.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 15.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Уэйн 2003 , стр. 164–165.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 18.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 11.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 12.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Тернер 1982 , с. 13.

- ^ Фишер 1991 , с. 22.

- ^ Бейсингер 1976 , с. 21.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 7.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Тернер, Лана (29 сентября 1982 г.). «Гость: Лана Тернер». Шоу Фила Донахью (интервью). Беседовал Фил Донахью . Мультимедийные развлечения .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Уэйн 2003 , с. 165.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Валентино 1976 , с. 18.

- ^ Бейсингер 1976 , с. 27.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 05:20.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Вилкерсон, WR III (1 июля 1995 г.). «Написание конца правдивой истории о Золушке» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс . Проверено 23 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Филдс 2007 , с. 79.

- ^ Льюис 2017 , с. 91.

- ^ Лоусон и Руфус 2000 , с. 41.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Буш 1940 , с. 64.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и 1634–1699: Маккаскер, Джей-Джей (1997). Сколько это в реальных деньгах? Исторический индекс цен для использования в качестве дефлятора денежных ценностей в экономике Соединенных Штатов: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF) . Американское антикварное общество . 1700–1799: Маккаскер, Джей-Джей (1992). Сколько это в реальных деньгах? Исторический индекс цен для использования в качестве дефлятора денежных ценностей в экономике Соединенных Штатов (PDF) . Американское антикварное общество . 1800 – настоящее время: Федеральный резервный банк Миннеаполиса. «Индекс потребительских цен (оценка) 1800–» . Проверено 29 февраля 2024 г.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 24.

- ^ Буш 1940 , с. 63.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , 6:05.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Уэйн 2003 , с. 166.

- ^ Фишер 1991 , с. 187.

- ^ Лангер, 2001 г. , событие происходит в 6:40.

- ^ Иордания 2009 , с. 221.

- ^ Валентино 1976 , с. 63.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Бейсингер 1976 , с. 31.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 29.

- ^ Лангер, 2001 г. , событие происходит в 7:00.

- ^ Брейер 1989 , с. 129.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 7:55.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , стр. 34–35.

- ^ Деннис 2007 , с. 97.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 9:08.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 33.

- ^ Конклин 2009 , с. 116.

- ^ Макферсон, Колвин (2 сентября 1939 г.). «Миниатюры обзоров новых фильмов» . Пост-отправка Сент-Луиса . Сент-Луис, Миссури. п. 5 – через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Конклин 2009 , с. 170.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 35.

- ^ Крейн 1988 , стр. 39–43.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 13:20.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 40.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 40.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 41.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 42.

- ^ Бартон 2010 , с. 101.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 15:18.

- ^ Валентино 1976 , с. 97.

- ^ Холлидей, Кейт (6 июня 1943 г.). «Гламур Паллинг на Лане» . Балтимор Сан . Балтимор, Мэриленд. п. 55 – через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 49.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 17:10.

- ^ Крейн и Де Серп 2008 , стр. 34, 185,

- ^ «Говоря о фотографиях… Эти кадры фрейдистского монтажа показывают психическое состояние Джекила, превращающегося в Хайда» . Жизнь . Time, Inc., 25 августа 1941 г., стр. 14–16. ISSN 0024-3019 – через Google Книги.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 50.

- ^ Шац 1999 , с. 111.

- ^ Штаб Времени (11 августа 1941 г.). «Обзор: доктор Джекил и мистер Хайд». Время . Том. XXXVIII, нет. 6. Тайм, Инк. с. 4. ISSN 0040-781X .

- ^ Бейсингер 1976 , стр. 51–53.

- ^ Уэйн 2003 , с. 173.

- ^ «Гейбл и Лана Тернер Стар» . Вечерние новости Сан-Хосе . Сан-Хосе, Калифорния. 17 октября 1942 г. с. 4 – через Новости Google.

- ^ Уэйн 2003 , с. 174.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 21:05.

- ^ Бейсингер 1976 , с. 54.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 51.

- ^ Эйджи, Джеймс (23 февраля 1942 г.). «Кино: Новые картинки» . Время . Проверено 28 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Фишер 1991 , стр. 187–189.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 33:33.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с «Поцелуи Ланы продают облигации без ее причудливой речи» . Питтсбург Пресс . Питтсбург, Пенсильвания. 25 июня 1942 г. с. 1 – через Newspapers.com.

- ^ «Поцелуи Ланы действительно «продаются» » . Евгений Регистр-охранник . Юджин, Орегон. 12 июня 1942 г. с. 1 – через Newspapers.com. Бернт Нортон

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 81.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 33:53.

- ^ «427 фотографий Второй мировой войны» .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час Валентино 1976 , с. 28.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 66.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 24:20.

- ^ Бейсингер 1976 , стр. 141–142.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 69.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Приход 2011 , с. 249.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , стр. 9, 85, 142.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 70.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , стр. 69–70.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 27:00.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 68.

- ^ Кроутер, Босли (2 апреля 1943 г.). « «Слегка опасен», комедия, в которой появляются Лана Тернер и Роберт Янг, в Капитолии - фильм «Святой» во дворце» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . п. 17 . Проверено 14 июня 2018 г.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , стр. 68–69.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 77.

- ^ Иордания 2011 , с. 232.

- ^ Валентино 1976 , с. 267.

- ^ Валентино 1976 , с. 133.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 82.

- ^ Валентино 1976 , с. 135.

- ^ Маслин, Джанет (26 апреля 1981 г.). «История та же, но Голливуд изменился» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 23 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Брук 2013 , с. 120.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 36:18.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 38:45.

- ^ «Фильм недели: Почтальон всегда звонит дважды» . Жизнь . Time, Inc., 29 апреля 1946 г., с. 129. ISSN 0024-3019 – через Google Книги.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Макферсон, Вирджиния (12 октября 1946 г.). «Теперь ее блюдо - тяжелая драма, - говорит Лана» . Демократ и хроника . Рочестер, Нью-Йорк. п. 11 – через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Маннерс, Дороти (3 августа 1946 г.). «Лана Тернер сыграет главную роль в «Улице зеленых дельфинов» . «Санкт-Петербург Таймс» . Санкт-Петербург, Флорида. п. 13 – через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 39:40.

- ^ Беллоуз 2006 , с. 192.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Уэйн 2003 , с. 178.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 32:44.

- ^ Brown & Broeske 2004 , стр. 199–201.

- ^ «Касс Тимберлейн» . Американского института кино Каталог . Архивировано из оригинала 18 июня 2018 года.

- ^ Маннерс, Дороти (3 августа 1946 г.). «Новости кино» . Сан-Антонио Лайт . Сан-Антонио, Техас. п. 6 – через Архив газет.

- ^ Макклелланд 1992 , с. 292.

- ^ Эстрадный штаб (31 декабря 1946 г.). «Касс Тимберлейн» . Разнообразие . Проверено 25 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Парсонс, Луэлла (12 августа 1947 г.). «Кинокарьера Хепберн, не затронутая откровенностью» . «Санкт-Петербург Таймс» . Санкт-Петербург, Флорида. п. 8 – через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Валентино 1976 , с. 158.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 42:51.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 44:12.

- ^ Бейсингер 1976 , с. 77.

- ^ Крейн 1988 , стр. 93–97.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 43:47.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 44:05.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , стр. 111–113.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 44:45.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 112.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 122.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Тернер 1982 , с. 122.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , стр. 115–116.

- ^ Томас, Боб (7 декабря 1949 г.). «Лана Тернер говорит, что теперь она домашняя девушка» . Пострегистрация . Айдахо-Фолс, Айдахо. п. 9 – через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 127.

- ^ «Лана Тернер оставляет следы в китайском театре Граумана» . Газета «Утренняя лавина» . Лаббок, Техас. 24 мая 1950 г. с. 24.

- ^ Шипман 1970 , с. 526.

- ^ Валентино 1976 , стр. 171–173.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 124.

- ^ «Пинза на высоте, Лана скучна в «Мистере Империум» » . «Санкт-Петербург Таймс» . Санкт-Петербург, Флорида. 6 ноября 1951 г. с. 8 – через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 53:37.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Тернер 1982 , с. 129.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 56:23.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , стр. 135–136.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , стр. 132–133.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , стр. 139–140.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , стр. 126–134.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , стр. 136–139.

- ^ Лангер, 2001 г. , событие происходит в 59:00.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 59:49.

- ^ Кроутер, Босли (9 сентября 1954 г.). «Обзор экрана; «Преданные», военная история, открывается в штате» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . п. 36 . Проверено 18 июня 2018 г.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 132.

- ^ Пэриш и Бауэрс 1973 , с. 777.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 155.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 146.

- ^ Эстрадный состав (31 декабря 1954 г.). «Блудный сын» . Разнообразие . Проверено 17 июня 2018 г.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 156.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 160.

- ^ Валентино 1976 , с. 211.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , стр. 158–159.

- ^ Валентино 1976 , с. 207.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 161.

- ^ Пэриш и Бауэрс 1973 , с. 745.

- ^ Уэйн 2003 , с. 183.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 162.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 154.

- ^ Крейн 1988 , с. 167.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 1:01:15.

- ^ Арчер, Грег (26 ноября 2008 г.). «Малыш остается в кадре» . Защитник . Архивировано из оригинала 5 января 2013 года.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 175.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 1:08:20.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 1:08:25.

- ^ Эстрадный состав (31 декабря 1957 г.). «Пейтон Плейс» . Разнообразие . Проверено 29 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кашнер и Макнейр 2002 , с. 254.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 181.

- ^ Бейсингер 1976 , с. 115.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 158.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , стр. 200–203.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , стр. 159–161.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 161.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , стр. 163–165.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Фельдштейн 2000 , с. 120.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , стр. 160–191.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 205.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , стр. 177–182.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , стр. 168–169.

- ^ Фишер 1991 , с. 217.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , стр. 169–172.

- ^ Уэйн 2003 , с. 185.

- ^ Кон 2001 , с. 388.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 170.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 180.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , стр. 183–187.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 190.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 186.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 188.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Льюис 2017 , с. 94.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 195.

- ^ Фельдштейн 2000 , стр. 120–121.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Крейн, Шерил (8 августа 2001 г.). «Дочь Ланы Тернер рассказывает свою историю» . CNN (интервью). Беседовал Ларри Кинг . Проверено 9 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Тернер 1982 , с. 203.

- ^ Фельдштейн 2000 , с. 122.

- ^ Валентино 1976 , с. 221.

- ^ Смит, Дуг (15 августа 2015 г.). «В ходе расследования 1958 года было подробно описано убийство парня Ланы Тернер» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс . Проверено 27 июля 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 233.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Эриксон 2017 , с. 119.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 1:19:15.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 215.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 217.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 1:20:05.

- ^ Лангер 2001 , событие происходит в 1:20:09.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Томас, Боб (8 мая 1957 г.). «Лана Тернер говорит, что у нее это было, и она больше не выйдет замуж» . Вечерние новости Порт-Анджелеса . Порт-Анджелес, Вашингтон: Ассошиэйтед Пресс. п. 12 – через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Кашнер и Макнейр 2002 , с. 267.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 219.

- ^ Персонал эстрады (31 декабря 1959 г.). «Имитация жизни» . Разнообразие . Проверено 17 июня 2018 г.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 208.

- ^ Кашнер и Макнейр 2002 , с. 257.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , стр. 215–221.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 221.

- ^ «Лана Тёрнер отказывается от роли в кино» . Ла Гранд Наблюдатель . Ла Гранде, Орегон. 5 марта 1959 г. с. 7 – через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , стр. 263–265.

- ^ Томас 1997 , с. 191.

- ^ Уэйн 2003 , с. 187.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 223.

- ^ Дункан, Рэй (3 июля 1960 г.). «Саспенс-фильм Ланы Тернер подрывает доверие» . Независимые Стар-Новости . Пасадена, Калифорния. п. 39 – через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 210.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 217.

- ^ Уэйн 2003 , с. 188.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 236.

- ^ Валентино 1976 , с. 234.

- ^ Слайд 1998 , с. 101.

- ^ Валентино 1976 , с. 240.

- ^ «Лана Тернер, пятый муж разведен, развода пока нет» . Deseret News и Telegram . Солт-Лейк-Сити, Юта. 23 сентября 1962 г. с. C7 – через Новости Google.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , с. 223.

- ^ Тернер 1982 , стр. 226.

- ^ Валентино 1976 , стр. 247–249.

- ^ Терри, Клиффорд (14 марта 1966 г.). «Лана делает мелодраму «Мадам Икс» правдоподобной» . Чикаго Трибьюн . Чикаго, Иллинойс. п. 59 – через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Монахан, Каспар (31 марта 1966 г.). «Лана Тёрнер на пике карьеры в «Мадам Икс» » . Питтсбург Пресс . Питтсбург, Пенсильвания. п. 32 – через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Валентино 1976 , с. 251.

- ^ Морелла и Эпштейн 1971 , с. 260.