Los Angeles

Los Angeles | |

|---|---|

| City of Los Angeles | |

| Nicknames: | |

Location within Los Angeles County | |

| Coordinates: 34°03′N 118°15′W / 34.050°N 118.250°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Los Angeles |

| Region | Southern California |

| CSA | Los Angeles-Long Beach |

| MSA | Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim |

| Pueblo | September 4, 1781[2] |

| City status | May 23, 1835[3] |

| Incorporated | April 4, 1850[4] |

| Named for | Our Lady, Queen of the Angels |

| Government | |

| • Type | Strong mayor–council[5] |

| • Body | Los Angeles City Council |

| • Mayor | Karen Bass (D) |

| • City Attorney | Hydee Feldstein Soto (D) |

| • City Controller | Kenneth Mejia (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 501.55 sq mi (1,299.01 km2) |

| • Land | 469.49 sq mi (1,215.97 km2) |

| • Water | 32.06 sq mi (83.04 km2) |

| Elevation | 305 ft (93 m) |

| Highest elevation | 5,075 ft (1,576 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 3,898,747 |

| • Estimate (2022)[7] | 3,819,538 |

| • Rank | 3rd in North America 2nd in the United States 1st in California |

| • Density | 8,304.22/sq mi (3,206.29/km2) |

| • Urban | 12,237,376 (US: 2nd) |

| • Urban density | 7,476.3/sq mi (2,886.6/km2) |

| • Metro | 13,200,998 (US: 2nd) |

| Demonyms | Angeleno, Angelino, Angeleño[10][11] |

| GDP | |

| • MSA | $1.227 trillion (2022) |

| • CSA | $1.528 trillion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC–08:00 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC–07:00 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | List |

| Area codes | 213, 323, 310, 424, 818, 747, 626 |

| FIPS code | 06-44000 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1662328, 2410877 |

| Website | lacity |

Los Angeles,[a] often referred to by its initials L.A., is the most populous city in the U.S. state of California. With roughly 3.9 million residents within the city limits as of 2020[update],[7] Los Angeles is the second-most populous city in the United States, behind only New York City; it is also the commercial, financial and cultural center of Southern California. Los Angeles has an ethnically and culturally diverse population, and is the principal city of a metropolitan area of 13.2 million people. Greater Los Angeles, which includes the Los Angeles and Riverside–San Bernardino metropolitan areas, is a sprawling metropolis of over 18 million residents.

The majority of the city proper lies in a basin in Southern California adjacent to the Pacific Ocean in the west and extending partly through the Santa Monica Mountains and north into the San Fernando Valley, with the city bordering the San Gabriel Valley to its east. It covers about 469 square miles (1,210 km2),[6] and is the county seat of Los Angeles County, which is the most populous county in the United States with an estimated 9.86 million residents as of 2022[update].[16] It is the fourth-most visited city in the U.S. with over 2.7 million visitors as of 2022.[17]

The area that became Los Angeles was originally inhabited by the indigenous Tongva people and later claimed by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo for Spain in 1542. The city was founded on September 4, 1781, under Spanish governor Felipe de Neve, on the village of Yaanga.[18] It became a part of Mexico in 1821 following the Mexican War of Independence. In 1848, at the end of the Mexican–American War, Los Angeles and the rest of California were purchased as part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and became part of the United States. Los Angeles was incorporated as a municipality on April 4, 1850, five months before California achieved statehood. The discovery of oil in the 1890s brought rapid growth to the city.[19] The city was further expanded with the completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913, which delivers water from Eastern California.

Los Angeles has a diverse economy with a broad range of industries. Despite a steep decline in film and television production since the Covid-19 pandemic, Los Angeles is now still the third-largest node of American film production,[20][21] the world’s largest by revenue; the city was an important site in the history of film. It also has one of the busiest container ports in the Americas.[22][23][24] In 2018, the Los Angeles metropolitan area had a gross metropolitan product of over $1.0 trillion,[25] making it the city with the third-largest GDP in the world, after New York and Tokyo. Los Angeles hosted the Summer Olympics in 1932 and 1984, and will also host in 2028. Despite a business exodus from Downtown Los Angeles since the COVID-19 pandemic, the city's urban core is evolving as a cultural center with the world's largest showcase of architecture designed by Frank Gehry.[26]

Toponymy

On September 4, 1781, a group of 44 settlers known as "Los Pobladores" founded the pueblo (town) they called El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles, 'The Town of Our Lady the Queen of the Angels'.[27] The original name of the settlement is disputed; the Guinness Book of World Records rendered it as "El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula";[28] other sources have shortened or alternate versions of the longer name.[29]

The local English pronunciation of the name of the city has varied over time. A 1953 article in the journal of the American Name Society asserts that the pronunciation /lɔːs ˈændʒələs/ lawss AN-jəl-əs was established following the 1850 incorporation of the city and that since the 1880s the pronunciation /loʊs ˈæŋɡələs/ lohss ANG-gəl-əs emerged from a trend in California to give places Spanish, or Spanish-sounding, names and pronunciations.[30] In 1908, librarian Charles Fletcher Lummis, who argued for the name's pronunciation with a hard g (/ɡ/),[31][32] reported that there were at least 12 pronunciation variants.[33] In the early 1900s, the Los Angeles Times advocated for pronouncing it Loce AHNG-hayl-ais (/loʊs ˈɑːŋheɪleɪs/), approximating Spanish [los ˈaŋxeles], by printing the respelling under its masthead for several years.[34] This did not find favor.[35]

Since the 1930s, /lɔːs ˈændʒələs/ has been most common.[36] In 1934, the United States Board on Geographic Names decreed that this pronunciation be used by the federal government.[34] This was also endorsed in 1952 by a "jury" appointed by Mayor Fletcher Bowron to devise an official pronunciation.[30][34]

Common pronunciations in the United Kingdom include /lɒs ˈændʒɪliːz, -lɪz, -lɪs/ loss AN-jil-eez, -iz, -iss.[37] Phonetician Jack Windsor Lewis described the most common one, /lɒs ˈændʒɪliːz/ , as a spelling pronunciation based on analogy to Greek words ending in -es, "reflecting a time when the classics were familiar if Spanish was not".[38]

History

Indigenous history

The settlement of Indigenous Californians in the modern Los Angeles Basin and the San Fernando Valley was dominated by the Tongva (now also known as the Gabrieleño since the era of Spanish colonization). The historic center of Tongva power in the region was the settlement of Yaanga (Tongva: Iyáangẚ), meaning "place of the poison oak", which would one day be the site where the Spanish founded the Pueblo de Los Ángeles. Iyáangẚ has also been translated as "the valley of smoke".[39][40][41][42][18]

Spanish rule

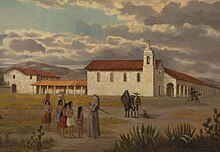

Maritime explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo claimed the area of southern California for the Spanish Empire in 1542, while on an official military exploring expedition, as he was moving northward along the Pacific coast from earlier colonizing bases of New Spain in Central and South America.[43] Gaspar de Portolà and Franciscan missionary Juan Crespí reached the present site of Los Angeles on August 2, 1769.[44]

In 1771, Franciscan friar Junípero Serra directed the building of the Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, the first mission in the area.[45] On September 4, 1781, a group of 44 settlers known as "Los Pobladores" founded the pueblo (town) they called El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles, 'The Town of Our Lady the Queen of the Angels'.[27] The present-day city has the largest Roman Catholic archdiocese in the United States. Two-thirds of the Mexican or (New Spain) settlers were mestizo or mulatto, a mixture of African, indigenous and European ancestry.[46] The settlement remained a small ranch town for decades, but by 1820, the population had increased to about 650 residents.[47] Today, the pueblo is commemorated in the historic district of Los Angeles Pueblo Plaza and Olvera Street, the oldest part of Los Angeles.[48]

Mexican rule

New Spain achieved its independence from the Spanish Empire in 1821, and the pueblo now existed within the new Mexican Republic. During Mexican rule, Governor Pío Pico made Los Angeles the regional capital of Alta California.[49] By this time, the new republic introduced more secularization acts within the Los Angeles region.[50] In 1846, during the wider Mexican-American war, marines from the United States occupied the pueblo. This resulted in the siege of Los Angeles where 150 Mexican militias fought the occupiers which eventually surrendered.[51]

Mexican rule ended during following the American Conquest of California, part of the larger Mexican-American War. Americans took control from the Californios after a series of battles, culminating with the signing of the Treaty of Cahuenga on January 13, 1847.[52] The Mexican Cession was formalized in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, which ceded Los Angeles and the rest of Alta California to the United States.

Post-Conquest era

Railroads arrived with the completion of the transcontinental Southern Pacific line from New Orleans to Los Angeles in 1876 and the Santa Fe Railroad in 1885.[53] Petroleum was discovered in the city and surrounding area in 1892, and by 1923, the discoveries had helped California become the country's largest oil producer, accounting for about one-quarter of the world's petroleum output.[54]

By 1900, the population had grown to more than 102,000,[55] putting pressure on the city's water supply.[56] The completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913, under the supervision of William Mulholland, ensured the continued growth of the city.[57] Because of clauses in the city's charter that prevented the City of Los Angeles from selling or providing water from the aqueduct to any area outside its borders, many adjacent cities and communities felt compelled to join Los Angeles.[58][59][60]

Los Angeles created the first municipal zoning ordinance in the United States. On September 14, 1908, the Los Angeles City Council promulgated residential and industrial land use zones. The new ordinance established three residential zones of a single type, where industrial uses were prohibited. The proscriptions included barns, lumber yards, and any industrial land use employing machine-powered equipment. These laws were enforced against industrial properties after the fact. These prohibitions were in addition to existing activities that were already regulated as nuisances. These included explosives warehousing, gas works, oil drilling, slaughterhouses, and tanneries. Los Angeles City Council also designated seven industrial zones within the city. However, between 1908 and 1915, the Los Angeles City Council created various exceptions to the broad proscriptions that applied to these three residential zones, and as a consequence, some industrial uses emerged within them. There are two differences between the 1908 Residence District Ordinance and later zoning laws in the United States. First, the 1908 laws did not establish a comprehensive zoning map as the 1916 New York City Zoning Ordinance did. Second, the residential zones did not distinguish types of housing; they treated apartments, hotels, and detached-single-family housing equally.[61]

In 1910, Hollywood merged into Los Angeles, with 10 movie companies already operating in the city at the time. By 1921, more than 80 percent of the world's film industry was concentrated in L.A.[62] The money generated by the industry kept the city insulated from much of the economic loss suffered by the rest of the country during the Great Depression.[63]By 1930, the population surpassed one million.[64] In 1932, the city hosted the Summer Olympics.

Post-WWII

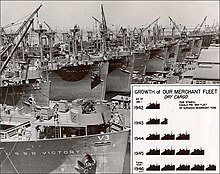

During World War II Los Angeles was a major center of wartime manufacturing, such as shipbuilding and aircraft. Calship built hundreds of Liberty Ships and Victory Ships on Terminal Island, and the Los Angeles area was the headquarters of six of the country's major aircraft manufacturers (Douglas Aircraft Company, Hughes Aircraft, Lockheed, North American Aviation, Northrop Corporation, and Vultee). During the war, more aircraft were produced in one year than in all the pre-war years since the Wright brothers flew the first airplane in 1903, combined. Manufacturing in Los Angeles skyrocketed, and as William S. Knudsen, of the National Defense Advisory Commission put it, "We won because we smothered the enemy in an avalanche of production, the like of which he had never seen, nor dreamed possible."[65]

After the end of World War II Los Angeles grew more rapidly than ever, sprawling into the San Fernando Valley.[66] The expansion of the state owned Interstate Highway System during the 1950s and 1960s helped propel suburban growth and signaled the demise of the city's privately owned electrified rail system, once the world's largest.

As a consequence of World War II, suburban growth, and population density, many amusement parks were built and operated in this area.[67] An example is Beverly Park, which was located at the corner of Beverly Boulevard and La Cienega before being closed and substituted by the Beverly Center.[68]

In the second half of the 20th century, Los Angeles substantially reduced the amount of housing that could be built by drastically downzoning the city. In 1960, the city had a total zoned capacity for approximately 10 million people. By 1990, that capacity had fallen to 4.5 million as a result of policy decisions to ban housing through zoning.[69]

Racial tensions led to the Watts riots in 1965, resulting in 34 deaths and over 1,000 injuries.[70]

In 1969, California became the birthplace of the Internet, as the first ARPANET transmission was sent from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) to the Stanford Research Institute in Menlo Park.[71]

In 1973, Tom Bradley was elected as the city's first African American mayor, serving for five terms until retiring in 1993. Other events in the city during the 1970s included the Symbionese Liberation Army's South Central standoff in 1974 and the Hillside Stranglers murder cases in 1977–1978.[72]

In early 1984, the city surpassed Chicago in population, thus becoming the second largest city in the United States.

In 1984, the city hosted the Summer Olympic Games for the second time. Despite being boycotted by 14 Communist countries, the 1984 Olympics became more financially successful than any previous,[73] and the second Olympics to turn a profit; the other, according to an analysis of contemporary newspaper reports, was the 1932 Summer Olympics, also held in Los Angeles.[74]

Racial tensions erupted on April 29, 1992, with the acquittal by a Simi Valley jury of four Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) officers captured on videotape beating Rodney King, culminating in large-scale riots.[75][76]

In 1994, the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake shook the city, causing $12.5 billion in damage and 72 deaths.[77] The century ended with the Rampart scandal, one of the most extensive documented cases of police misconduct in American history.[78]

21st century

In 2002, Mayor James Hahn led the campaign against secession, resulting in voters defeating efforts by the San Fernando Valley and Hollywood to secede from the city.[79]

In 2022, Karen Bass became the city's first female mayor, making Los Angeles the largest U.S. city to have ever had a woman as mayor.[80]

Los Angeles will host the 2028 Summer Olympics and Paralympic Games, making Los Angeles the third city to host the Olympics three times.[81][82]

Geography

Topography

The city of Los Angeles covers a total area of 502.7 square miles (1,302 km2), comprising 468.7 square miles (1,214 km2) of land and 34.0 square miles (88 km2) of water.[83] The city extends for 44 miles (71 km) from north to south and for 29 miles (47 km) from east to west. The perimeter of the city is 342 miles (550 km).

Los Angeles is both flat and hilly. The highest point in the city proper is Mount Lukens at 5,074 ft (1,547 m),[84][85] located in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains at the north extent of the Crescenta Valley. The eastern end of the Santa Monica Mountains stretches from Downtown to the Pacific Ocean and separates the Los Angeles Basin from the San Fernando Valley. Other hilly parts of Los Angeles include the Mt. Washington area north of Downtown, eastern parts such as Boyle Heights, the Crenshaw district around the Baldwin Hills, and the San Pedro district.

Surrounding the city are much higher mountains. Immediately to the north lie the San Gabriel Mountains, which is a popular recreation area for Angelenos. Its high point is Mount San Antonio, locally known as Mount Baldy, which reaches 10,064 feet (3,068 m). Further afield, the highest point in southern California is San Gorgonio Mountain, 81 miles (130 km) east of downtown Los Angeles,[86] with a height of 11,503 feet (3,506 m).

The Los Angeles River, which is largely seasonal, is the primary drainage channel. It was straightened and lined in 51 miles (82 km) of concrete by the Army Corps of Engineers to act as a flood control channel.[87] The river begins in the Canoga Park district of the city, flows east from the San Fernando Valley along the north edge of the Santa Monica Mountains, and turns south through the city center, flowing to its mouth in the Port of Long Beach at the Pacific Ocean. The smaller Ballona Creek flows into the Santa Monica Bay at Playa del Rey.

Vegetation

Los Angeles is rich in native plant species partly because of its diversity of habitats, including beaches, wetlands, and mountains. The most prevalent plant communities are coastal sage scrub, chaparral shrubland, and riparian woodland.[88] Native plants include: the California poppy, matilija poppy, toyon, Ceanothus, Chamise, Coast Live Oak, sycamore, willow and Giant Wildrye. Many of these native species, such as the Los Angeles sunflower, have become so rare as to be considered endangered. Mexican Fan Palms, Canary Island Palms, Queen Palms, Date Palms, and California Fan Palms are common in the Los Angeles area, although only the last is native to California, though still not native to the City of Los Angeles.

Los Angeles has a number of official flora:

- the official tree of Los Angeles is the Coral Tree (Erythrina caffra)[89]

- the official flower is the Bird of Paradise (Strelitzia reginae)[90]

- the official plant is toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia)[91]

Fauna

The city has an urban population of bobcats (Lynx rufus).[92] Mange is a common problem in this population.[92] Although Serieys et al. 2014 find selection of immune genetics at several loci they do not demonstrate that this produces a real difference which helps the bobcats to survive future mange outbreaks.[92]

Geology

Los Angeles is subject to earthquakes because of its location on the Pacific Ring of Fire. The geologic instability has produced numerous faults, which cause approximately 10,000 earthquakes annually in Southern California, though most of them are too small to be felt.[93] The strike-slip San Andreas Fault system, which sits at the boundary between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate, passes through the Los Angeles metropolitan area. The segment of the fault passing through Southern California experiences a major earthquake roughly every 110 to 140 years, and seismologists have warned about the next "big one", as the last major earthquake was the 1857 Fort Tejon earthquake.[94] The Los Angeles basin and metropolitan area are also at risk from blind thrust earthquakes.[95] Major earthquakes that have hit the Los Angeles area include the 1933 Long Beach, 1971 San Fernando, 1987 Whittier Narrows, and the 1994 Northridge events. All but a few are of low intensity and are not felt. The USGS has released the UCERF California earthquake forecast, which models earthquake occurrence in California. Parts of the city are also vulnerable to tsunamis; harbor areas were damaged by waves from Aleutian Islands earthquake in 1946, Valdivia earthquake in 1960, Alaska earthquake in 1964, Chile earthquake in 2010 and Japan earthquake in 2011.[96]

Cityscape

The city is divided into many different districts and neighborhoods,[97][98] some of which had been separately incorporated cities that eventually merged with Los Angeles.[99] These neighborhoods were developed piecemeal, and are well-defined enough that the city has signage which marks nearly all of them.[100]

Overview

The city's street patterns generally follow a grid plan, with uniform block lengths and occasional roads that cut across blocks. However, this is complicated by rugged terrain, which has necessitated having different grids for each of the valleys that Los Angeles covers. Major streets are designed to move large volumes of traffic through many parts of the city, many of which are extremely long; Sepulveda Boulevard is 43 miles (69 km) long, while Foothill Boulevard is over 60 miles (97 km) long, reaching as far east as San Bernardino. Drivers in Los Angeles suffer from one of the worst rush hour periods in the world, according to an annual traffic index by navigation system maker, TomTom. LA drivers spend an additional 92 hours in traffic each year. During the peak rush hour, there is 80% congestion, according to the index.[101]

Los Angeles is often characterized by the presence of low-rise buildings, in contrast to New York City. Outside of a few centers such as Downtown, Warner Center, Century City, Koreatown, Miracle Mile, Hollywood, and Westwood, skyscrapers and high-rise buildings are not common in Los Angeles. The few skyscrapers built outside of those areas often stand out above the rest of the surrounding landscape. Most construction is done in separate units, rather than wall-to-wall. However, Downtown Los Angeles itself has many buildings over 30 stories, with fourteen over 50 stories, and two over 70 stories, the tallest of which is the Wilshire Grand Center.

- Selection of neighborhoods in Los Angeles

Climate

| Los Angeles (Downtown) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Los Angeles has a two-season semi-arid climate (Köppen: BSh) with dry summers and very mild winters, but it receives more annual precipitation than most semi-arid climates, narrowly missing the boundary of a Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csb on the coast, Csa otherwise).[103] Daytime temperatures are generally temperate all year round. In winter, they average around 68 °F (20 °C).[104] Autumn months tend to be hot, with major heat waves a common occurrence in September and October, while the spring months tend to be cooler and experience more precipitation. Los Angeles has plenty of sunshine throughout the year, with an average of only 35 days with measurable precipitation annually.[105]

Temperatures in the coastal basin exceed 90 °F (32 °C) on a dozen or so days in the year, from one day a month in April, May, June and November to three days a month in July, August, October and to five days in September.[105] Temperatures in the San Fernando and San Gabriel Valleys are considerably warmer. Temperatures are subject to substantial daily swings; in inland areas the difference between the average daily low and the average daily high is over 30 °F (17 °C).[106] The average annual temperature of the sea is 63 °F (17 °C), from 58 °F (14 °C) in January to 68 °F (20 °C) in August.[107] Hours of sunshine total more than 3,000 per year, from an average of 7 hours of sunshine per day in December to an average of 12 in July.[108]

Due to the mountainous terrain of the surrounding region, the Los Angeles area contains a large number of distinct microclimates, causing extreme variations in temperature in close physical proximity to each other. For example, the average July maximum temperature at the Santa Monica Pier is 70 °F (21 °C) whereas it is 95 °F (35 °C) in Canoga Park, 15 miles (24 km) away.[109] The city, like much of the Southern Californian coast, is subject to a late spring/early summer weather phenomenon called "June Gloom". This involves overcast or foggy skies in the morning that yield to sun by early afternoon.[110]

More recently, statewide droughts in California have further strained the city's water security.[111] Downtown Los Angeles averages 14.67 in (373 mm) of precipitation annually, mainly occurring between November and March,[112][106] generally in the form of moderate rain showers, but sometimes as heavy rainfall during winter storms. Rainfall is usually higher in the hills and coastal slopes of the mountains because of orographic uplift. Summer days are usually rainless. Rarely, an incursion of moist air from the south or east can bring brief thunderstorms in late summer, especially to the mountains. The coast gets slightly less rainfall, while the inland and mountain areas get considerably more. Years of average rainfall are rare. The usual pattern is a year-to-year variability, with a short string of dry years of 5–10 in (130–250 mm) rainfall, followed by one or two wet years with more than 20 in (510 mm).[106] Wet years are usually associated with warm water El Niño conditions in the Pacific, dry years with cooler water La Niña episodes. A series of rainy days can bring floods to the lowlands and mudslides to the hills, especially after wildfires have denuded the slopes.

Both freezing temperatures and snowfall are extremely rare in the city basin and along the coast, with the last occurrence of a 32 °F (0 °C) reading at the downtown station being January 29, 1979;[106] freezing temperatures occur nearly every year in valley locations while the mountains within city limits typically receive snowfall every winter. The greatest snowfall recorded in downtown Los Angeles was 2.0 inches (5 cm) on January 15, 1932.[106][113] While the most recent snowfall occurred in February 2019, the first snowfall since 1962,[114][115] with snow falling in areas adjacent to Los Angeles as recently as January 2021.[116] Brief, localized instances of hail can occur on rare occasions, but are more common than snowfall. At the official downtown station, the highest recorded temperature is 113 °F (45 °C) on September 27, 2010,[106][117] while the lowest is 28 °F (−2 °C),[106] on January 4, 1949.[106] Within the City of Los Angeles, the highest temperature ever officially recorded is 121 °F (49 °C), on September 6, 2020, at the weather station at Pierce College in the San Fernando Valley neighborhood of Woodland Hills.[118] During autumn and winter, Santa Ana winds sometimes bring much warmer and drier conditions to Los Angeles, and raise wildfire risk.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °F (°C) | 95 (35) | 95 (35) | 99 (37) | 106 (41) | 103 (39) | 112 (44) | 109 (43) | 106 (41) | 113 (45) | 108 (42) | 100 (38) | 92 (33) | 113 (45) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 83.0 (28.3) | 82.8 (28.2) | 85.8 (29.9) | 90.1 (32.3) | 88.9 (31.6) | 89.1 (31.7) | 93.5 (34.2) | 95.2 (35.1) | 99.4 (37.4) | 95.7 (35.4) | 88.9 (31.6) | 81.0 (27.2) | 101.5 (38.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 68.0 (20.0) | 68.0 (20.0) | 69.9 (21.1) | 72.4 (22.4) | 73.7 (23.2) | 77.2 (25.1) | 82.0 (27.8) | 84.0 (28.9) | 83.0 (28.3) | 78.6 (25.9) | 72.9 (22.7) | 67.4 (19.7) | 74.8 (23.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 58.4 (14.7) | 59.0 (15.0) | 61.1 (16.2) | 63.6 (17.6) | 65.9 (18.8) | 69.3 (20.7) | 73.3 (22.9) | 74.7 (23.7) | 73.6 (23.1) | 69.3 (20.7) | 63.0 (17.2) | 57.8 (14.3) | 65.8 (18.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 48.9 (9.4) | 50.0 (10.0) | 52.4 (11.3) | 54.8 (12.7) | 58.1 (14.5) | 61.4 (16.3) | 64.7 (18.2) | 65.4 (18.6) | 64.2 (17.9) | 59.9 (15.5) | 53.1 (11.7) | 48.2 (9.0) | 56.8 (13.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 41.4 (5.2) | 42.9 (6.1) | 45.4 (7.4) | 48.9 (9.4) | 53.5 (11.9) | 57.4 (14.1) | 61.1 (16.2) | 61.7 (16.5) | 59.1 (15.1) | 53.7 (12.1) | 45.4 (7.4) | 40.5 (4.7) | 39.2 (4.0) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 28 (−2) | 28 (−2) | 31 (−1) | 36 (2) | 40 (4) | 46 (8) | 49 (9) | 49 (9) | 44 (7) | 40 (4) | 34 (1) | 30 (−1) | 28 (−2) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 3.29 (84) | 3.64 (92) | 2.23 (57) | 0.69 (18) | 0.32 (8.1) | 0.09 (2.3) | 0.02 (0.51) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.13 (3.3) | 0.58 (15) | 0.78 (20) | 2.48 (63) | 14.25 (362) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.1 | 6.3 | 5.1 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 5.5 | 34.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 225.3 | 222.5 | 267.0 | 303.5 | 276.2 | 275.8 | 364.1 | 349.5 | 278.5 | 255.1 | 217.3 | 219.4 | 3,254.2 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 71 | 72 | 72 | 78 | 64 | 64 | 83 | 84 | 75 | 73 | 70 | 71 | 73 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2.9 | 4.2 | 6.2 | 8.1 | 9.2 | 10.4 | 10.8 | 10.0 | 8.1 | 5.4 | 3.5 | 2.6 | 6.7 |

| Source 1: NOAA (sun 1961–1977)[119][102][120][121] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: UV Index Today (1995 to 2022)[122] | |||||||||||||

Environmental issues

| External audio | |

|---|---|

Owing to geography, heavy reliance on automobiles, and the Los Angeles/Long Beach port complex, Los Angeles suffers from air pollution in the form of smog. The Los Angeles Basin and the San Fernando Valley are susceptible to atmospheric inversion, which holds in the exhausts from road vehicles, airplanes, locomotives, shipping, manufacturing, and other sources.[126]

The smog season lasts from approximately May to October.[127] While other large cities rely on rain to clear smog, Los Angeles gets only 15 inches (380 mm) of rain each year: pollution accumulates over many consecutive days. Issues of air quality in Los Angeles and other major cities led to the passage of early national environmental legislation, including the Clean Air Act. When the act was passed, California was unable to create a State Implementation Plan that would enable it to meet the new air quality standards, largely because of the level of pollution in Los Angeles generated by older vehicles.[128] More recently, the state of California has led the nation in working to limit pollution by mandating low-emission vehicles. Smog is expected to continue to drop in the coming years because of aggressive steps to reduce it, which include electric and hybrid cars, improvements in mass transit, and other measures.

The number of Stage 1 smog alerts in Los Angeles has declined from over 100 per year in the 1970s to almost zero in the new millennium.[129] Despite improvement, the 2006 and 2007 annual reports of the American Lung Association ranked the city as the most polluted in the country with short-term particle pollution and year-round particle pollution.[130] In 2008, the city was ranked the second most polluted and again had the highest year-round particulate pollution.[131] The city met its goal of providing 20 percent of the city's power from renewable sources in 2010.[132] The American Lung Association's 2013 survey ranks the metro area as having the nation's worst smog, and fourth in both short-term and year-round pollution amounts.[133]

Los Angeles is also home to the nation's largest urban oil field. There are more than 700 active oil wells within 1,500 feet (460 m) of homes, churches, schools and hospitals in the city, a situation about which the EPA has voiced serious concerns.[134]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 1,610 | — | |

| 1860 | 4,385 | 172.4% | |

| 1870 | 5,728 | 30.6% | |

| 1880 | 11,183 | 95.2% | |

| 1890 | 50,395 | 350.6% | |

| 1900 | 102,479 | 103.4% | |

| 1910 | 319,198 | 211.5% | |

| 1920 | 576,673 | 80.7% | |

| 1930 | 1,238,048 | 114.7% | |

| 1940 | 1,504,277 | 21.5% | |

| 1950 | 1,970,358 | 31.0% | |

| 1960 | 2,479,015 | 25.8% | |

| 1970 | 2,811,801 | 13.4% | |

| 1980 | 2,968,528 | 5.6% | |

| 1990 | 3,485,398 | 17.4% | |

| 2000 | 3,694,820 | 6.0% | |

| 2010 | 3,792,621 | 2.6% | |

| 2020 | 3,898,747 | 2.8% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 3,820,914 | [135] | −2.0% |

| United States Census Bureau[136] 2010–2020, 2021[7] | |||

The 2010 U.S. census[137] reported Los Angeles had a population of 3,792,621.[138] The population density was 8,092.3 people per square mile (3,124.5 people/km2). The age distribution was 874,525 people (23.1%) under 18, 434,478 people (11.5%) from 18 to 24, 1,209,367 people (31.9%) from 25 to 44, 877,555 people (23.1%) from 45 to 64, and 396,696 people (10.5%) who were 65 or older.[138] The median age was 34.1 years. For every 100 females, there were 99.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.6 males.[138]

There were 1,413,995 housing units—up from 1,298,350 during 2005–2009[138]—at an average density of 2,812.8 households per square mile (1,086.0 households/km2), of which 503,863 (38.2%) were owner-occupied, and 814,305 (61.8%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.1%; the rental vacancy rate was 6.1%. 1,535,444 people (40.5% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 2,172,576 people (57.3%) lived in rental housing units.[138]

According to the 2010 United States Census, Los Angeles had a median household income of $49,497, with 22.0% of the population living below the federal poverty line.[138]

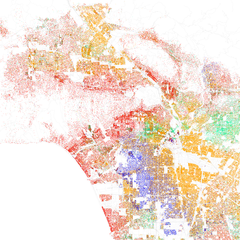

Race and ethnicity

| Racial and ethnic composition | 1940[139] | 1970[139] | 1990[139] | 2010[140] | 2020[140] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 7.1% | 17.1% | 39.9% | 48.5% | 46.9% |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 86.3% | 61.1% | 37.3% | 28.7% | 28.9% |

| Asian (non-Hispanic) | 2.2% | 3.6% | 9.8% | 11.1% | 11.7% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 4.2% | 17.9% | 14.0% | 9.2% | 8.3% |

| Other (non-Hispanic) | N/A | N/A | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.7% |

| Two or more races (non-Hispanic) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2.0% | 3.3% |

According to the 2010 census, the racial makeup of Los Angeles included: 1,888,158 Whites (49.8%), 365,118 African Americans (9.6%), 28,215 Native Americans (0.7%), 426,959 Asians (11.3%), 5,577 Pacific Islanders (0.1%), 902,959 from other races (23.8%), and 175,635 (4.6%) from two or more races.[138] There were 1,838,822 Hispanic or Latino residents of any race (48.5%). Los Angeles is home to people from more than 140 countries speaking 224 different identified languages.[141] Ethnic enclaves like Chinatown, Historic Filipinotown, Koreatown, Little Armenia, Little Ethiopia, Tehrangeles, Little Tokyo, Little Bangladesh, and Thai Town provide examples of the polyglot character of Los Angeles.

Non-Hispanic Whites were 28.7% of the population in 2010,[138] compared to 86.3% in 1940.[139] The majority of the Non-Hispanic White population is living in areas along the Pacific coast as well as in neighborhoods near and on the Santa Monica Mountains from the Pacific Palisades to Los Feliz.

Mexican ancestry makes up the largest ethnic group of Hispanics at 31.9% of the city's population, followed by those of Salvadoran (6.0%) and Guatemalan (3.6%) heritage. The Hispanic population has a long established Mexican-American and Central American community and is spread throughout the entire city of Los Angeles and its metropolitan area. It is most heavily concentrated in regions around Downtown, such as East Los Angeles, Northeast Los Angeles and Westlake. Furthermore, a vast majority of residents in neighborhoods in eastern South Los Angeles towards Downey are of Hispanic origin.[142]

The largest Asian ethnic groups are Filipinos (3.2%) and Koreans (2.9%), which have their own established ethnic enclaves—Koreatown in the Wilshire Center and Historic Filipinotown.[143] Chinese people, which make up 1.8% of Los Angeles's population, reside mostly outside of Los Angeles city limits, in the San Gabriel Valley of eastern Los Angeles County, but make a sizable presence in the city, notably in Chinatown.[144] Chinatown and Thaitown are also home to many Thais and Cambodians, which make up 0.3% and 0.1% of Los Angeles's population, respectively. The Japanese comprise 0.9% of the city's population and have an established Little Tokyo in the city's downtown, and another significant community of Japanese Americans is in the Sawtelle district of West Los Angeles. Vietnamese make up 0.5% of Los Angeles's population. Indians make up 0.9% of the city's population. Los Angeles is also home to Armenians, Assyrians, and Iranians, many of whom live in enclaves like Little Armenia and Tehrangeles.[145][146]

African Americans have been the predominant ethnic group in South Los Angeles, which has emerged as the largest African-American community in the western United States since the 1960s. The neighborhoods of South Los Angeles with highest concentration of African Americans include Crenshaw, Baldwin Hills, Leimert Park, Hyde Park, Gramercy Park, Manchester Square and Watts.[147] There is also a sizable Eritrean and Ethiopian community in the Fairfax region.[148]

Los Angeles has the second-largest Mexican, Armenian, Salvadoran, Filipino, and Guatemalan populations by city in the world, the third-largest Canadian population in the world, and has the largest Japanese, Iranian/Persian, Cambodian, and Romani (Gypsy) populations in the country.[149] The Italian community is concentrated in San Pedro.[150]

Most of Los Angeles' foreign-born population were born in Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, the Philippines and South Korea.[151]

Religion

According to a 2014 study by the Pew Research Center, Christianity is the most prevalently practiced religion in Los Angeles (65%).[152][153] The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles is the largest archdiocese in the country.[154] Cardinal Roger Mahony, as the archbishop, oversaw construction of the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, which opened in September 2002 in Downtown Los Angeles.[155]

In 2011, the once common, but ultimately lapsed, custom of conducting a procession and Mass in honor of Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles, in commemoration of the founding of the City of Los Angeles in 1781, was revived by the Queen of Angels Foundation and its founder Mark Albert, with the support of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles as well as several civic leaders.[156] The recently revived custom is a continuation of the original processions and Masses that commenced on the first anniversary of the founding of Los Angeles in 1782 and continued for nearly a century thereafter.

With 621,000 Jews in the metropolitan area, the region has the second-largest population of Jews in the United States, after New York City.[157] Many of Los Angeles's Jews now live on the Westside and in the San Fernando Valley, though Boyle Heights once had a large Jewish population prior to World War II due to restrictive housing covenants. Major Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods include Hancock Park, Pico-Robertson, and Valley Village, while Jewish Israelis are well represented in the Encino and Tarzana neighborhoods, and Persian Jews in Beverly Hills. Many varieties of Judaism are represented in the greater Los Angeles area, including Reform, Conservative, Orthodox, and Reconstructionist. The Breed Street Shul in East Los Angeles, built in 1923, was the largest synagogue west of Chicago in its early decades; it is no longer in daily use as a synagogue and is being converted to a museum and community center.[158][159] The Kabbalah Centre also has a presence in the city.[160]

The International Church of the Foursquare Gospel was founded in Los Angeles by Aimee Semple McPherson in 1923 and remains headquartered there to this day. For many years, the church convened at Angelus Temple, which, at its construction, was one of the largest churches in the country.[161]

Los Angeles has had a rich and influential Protestant tradition. The first Protestant service in Los Angeles was a Methodist meeting held in a private home in 1850 and the oldest Protestant church still operating, First Congregational Church, was founded in 1867.[162] In the early 1900s the Bible Institute Of Los Angeles published the founding documents of the Christian Fundamentalist movement and the Azusa Street Revival launched Pentecostalism.[162] The Metropolitan Community Church also had its origins in the Los Angeles area.[163] Important churches in the city include First Presbyterian Church of Hollywood, Bel Air Presbyterian Church, First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Los Angeles, West Angeles Church of God in Christ, Second Baptist Church, Crenshaw Christian Center, McCarty Memorial Christian Church, and First Congregational Church.

The Los Angeles California Temple, the second-largest temple operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, is on Santa Monica Boulevard in the Westwood neighborhood of Los Angeles. Dedicated in 1956, it was the first temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints built in California and it was the largest in the world when completed.[164]

The Hollywood region of Los Angeles also has several significant headquarters, churches, and the Celebrity Center of Scientology.[165][166]

Because of Los Angeles's large multi-ethnic population, a wide variety of faiths are practiced, including Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Zoroastrianism, Sikhism, Baháʼí, various Eastern Orthodox Churches, Sufism, Shintoism, Taoism, Confucianism, Chinese folk religion and countless others. Immigrants from Asia for example, have formed a number of significant Buddhist congregations making the city home to the greatest variety of Buddhists in the world. The first Buddhist joss house was founded in the city in 1875.[162] Atheism and other secular beliefs are also common, as the city is the largest in the Western U.S. Unchurched Belt.

Homelessness

As of January 2020, there are 41,290 homeless people in the City of Los Angeles, comprising roughly 62% of the homeless population of LA County.[167] This is an increase of 14.2% over the previous year (with a 12.7% increase in the overall homeless population of LA County).[168][169] The epicenter of homelessness in Los Angeles is the Skid Row neighborhood, which contains 8,000 homeless people, one of the largest stable populations of homeless people in the United States.[170][171] The increased homeless population in Los Angeles has been attributed to lack of housing affordability[172] and to substance abuse.[173] Almost 60 percent of the 82,955 people who became newly homeless in 2019 said their homelessness was because of economic hardship.[168] In Los Angeles, black people are roughly four times more likely to experience homelessness.[168][174]

Economy

The economy of Los Angeles is driven by international trade, entertainment (television, motion pictures, video games, music recording, and production), aerospace, technology, petroleum, fashion, apparel, and tourism.[175] Other significant industries include finance, telecommunications, law, healthcare, and transportation. In the 2017 Global Financial Centres Index, Los Angeles was ranked the 19th most competitive financial center in the world and sixth most competitive in the U.S. after New York City, San Francisco, Chicago, Boston, and Washington, D.C.[176] Although a business exodus has occurred away from Downtown Los Angeles since the COVID-19 pandemic, efforts are underway to re-invent the city's urban core as a cultural center with the world's largest showcase of architecture designed by Frank Gehry.[26]

Of the five major film studios, only Paramount Pictures is within Los Angeles' city limits;[177] it is located in the so-called Thirty-Mile Zone of entertainment headquarters in Southern California.

Los Angeles is the largest manufacturing center in the United States.[178] The contiguous ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach together comprise the busiest port in the United States by some measures and the fifth busiest port in the world, vital to trade within the Pacific Rim.[179]

The Los Angeles metropolitan area has a gross metropolitan product of over $1.0 trillion (as of 2018[update]),[25] making it the third-largest economic metropolitan area in the world, after New York and Tokyo.[25] Los Angeles has been classified an "alpha world city" according to a 2012 study by a group at Loughborough University.[180]

The Department of Cannabis Regulation enforces cannabis legislation after the legalization of the sale and distribution of cannabis in 2016.[181] As of October 2019[update], more than 300 existing cannabis businesses (both retailers and their suppliers) have been granted approval to operate in what is considered the nation's largest market.[182][183]

As of 2018[update], Los Angeles is home to three Fortune 500 companies: AECOM, CBRE Group, and Reliance Steel & Aluminum Co.[184] Other companies headquartered in Los Angeles and the surrounding metropolitan area include The Aerospace Corporation, California Pizza Kitchen,[185] Capital Group Companies, Deluxe Entertainment Services Group, Dine Brands Global, DreamWorks Animation, Dollar Shave Club, Fandango Media, Farmers Insurance Group, Forever 21, Hulu, Panda Express, SpaceX, Ubisoft Film & Television, The Walt Disney Company, Universal Pictures, Warner Bros., Warner Music Group, and Trader Joe's.

| Largest non-government employers in Los Angeles County, June 2022[186] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Rank | Employer | Employees |

| 1 | Kaiser Permanente | 40,303 |

| 2 | University of Southern California | 22,735 |

| 3 | Northrop Grumman Corp. | 18,000 |

| 4 | Cedars-Sinai Medical Center | 16,659 |

| 5 | Target Corp. | 15,888 |

| 6 | Allied Universal | 15,326 |

| 7 | Providence Health and Services Southern California | 14,935 |

| 8 | Ralphs/Food 4 Less (Kroger Co. Division) | 14,000 |

| 9 | Walmart | 14,000 |

| 10 | Walt Disney Co. | 12,200 |

Arts and culture

Los Angeles is often billed as the creative capital of the world because one in every six of its residents works in a creative industry[187] and there are more artists, writers, filmmakers, actors, dancers and musicians living and working in Los Angeles than any other city at any other time in world history.[188] The city is also known for its prolific murals.[189]

Landmarks

The architecture of Los Angeles is influenced by its Spanish, Mexican, and American roots. Popular styles in the city include Spanish Colonial Revival style, Mission Revival style, California Churrigueresque style, Mediterranean Revival style, Art Deco style, and Mid-Century Modern style, among others.

Important landmarks in Los Angeles include the Hollywood Sign,[190] Walt Disney Concert Hall, Capitol Records Building,[191] the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels,[192] Angels Flight,[193] Grauman's Chinese Theatre,[194] Dolby Theatre,[195] Griffith Observatory,[196] Getty Center,[197] Getty Villa,[198] Stahl House,[199] the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, L.A. Live,[200] the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Venice Canal Historic District and boardwalk, Theme Building, Bradbury Building, U.S. Bank Tower, Wilshire Grand Center, Hollywood Boulevard, Los Angeles City Hall, Hollywood Bowl,[201] battleship USS Iowa, Watts Towers,[202] Crypto.com Arena, Dodger Stadium, and Olvera Street.[203]

Movies and the performing arts

The performing arts play a major role in Los Angeles's cultural identity. According to the USC Stevens Institute for Innovation, "there are more than 1,100 annual theatrical productions and 21 openings every week."[188] The Los Angeles Music Center is "one of the three largest performing arts centers in the nation", with more than 1.3 million visitors per year.[204] The Walt Disney Concert Hall, centerpiece of the Music Center, is home to the prestigious Los Angeles Philharmonic.[205] Notable organizations such as Center Theatre Group, the Los Angeles Master Chorale, and the Los Angeles Opera are also resident companies of the Music Center.[206][207][208] Talent is locally cultivated at premier institutions such as the Colburn School and the USC Thornton School of Music.

The city's Hollywood neighborhood has been recognized as the center of the motion picture industry, having held this distinction since the early 20th century, and the Los Angeles area is also associated with being the center of the television industry.[209] The city is home to major film studios as well as major record labels. Los Angeles plays host to the annual Academy Awards, the Primetime Emmy Awards, the Grammy Awards as well as many other entertainment industry awards shows. Los Angeles is the site of the USC School of Cinematic Arts which is the oldest film school in the United States.[210]

Museums and galleries

There are 841 museums and art galleries in Los Angeles County,[211] more museums per capita than any other city in the U.S.[211] Some of the notable museums are the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (the largest art museum in the Western United States[212]), the Getty Center (part of the J. Paul Getty Trust, the world's wealthiest art institution[213]), the Petersen Automotive Museum,[214] the Huntington Library,[215] the Natural History Museum,[216] the Battleship Iowa,[217] The Broad, which houses over 2,000 works of contemporary art[218] and the Museum of Contemporary Art.[219] A significant number of art galleries are on Gallery Row, and tens of thousands attend the monthly Downtown Art Walk there.[220]

Libraries

The Los Angeles Public Library system operates 72 public libraries in the city.[221] Enclaves of unincorporated areas are served by branches of the County of Los Angeles Public Library, many of which are within walking distance to residents.[222]

Cuisine

Los Angeles' food culture is a fusion of global cuisine brought on by the city's rich immigrant history and population. As of 2022, the Michelin Guide recognized 10 restaurants granting 2 restaurants two stars and eight restaurants one star.[223]

Latin American immigrants, particularly Mexican immigrants, brought tacos, burritos, quesadillas, tortas, tamales, and enchiladas served from food trucks and stands, taquerias, and cafés. Asian restaurants, many immigrant-owned, exist throughout the city with hotspots in Chinatown,[224] Koreatown,[225] and Little Tokyo.[226] Los Angeles also carries an outsized offering of vegan, vegetarian, and plant-based options.

Sports

Los Angeles and its metropolitan area are the home of eleven top-level professional sports teams, several of which play in neighboring communities but use Los Angeles in their name. These teams include the Los Angeles Dodgers[227] and Los Angeles Angels[228] of Major League Baseball (MLB), the Los Angeles Rams[229] and Los Angeles Chargers of the National Football League (NFL), the Los Angeles Lakers[230] and Los Angeles Clippers[231] of the National Basketball Association (NBA), the Los Angeles Kings[232] and Anaheim Ducks[233] of the National Hockey League (NHL), the Los Angeles Galaxy[234] and Los Angeles FC[235] of Major League Soccer (MLS), the Los Angeles Sparks of the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA),[236] the SoCal Lashings of the Minor League Cricket (MiLC) and the Los Angeles Knight Riders of the Major League Cricket (MLC).[237]

Other notable sports teams include the UCLA Bruins and the USC Trojans in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), both of which are Division I teams in the Pac-12 Conference, but will soon be moving to the Big Ten Conference.[238]

Los Angeles is the second-largest city in the United States but hosted no NFL team between 1995 and 2015. At one time, the Los Angeles area hosted two NFL teams: the Rams and the Raiders. Both left the city in 1995, with the Rams moving to St. Louis, and the Raiders moving back to their original home of Oakland. After 21 seasons in St. Louis, on January 12, 2016, the NFL announced the Rams would be moving back to Los Angeles for the 2016 NFL season with its home games played at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum for four seasons.[239][240][241] Prior to 1995, the Rams played their home games in the Coliseum from 1946 to 1979 which made them the first professional sports team to play in Los Angeles, and then moved to Anaheim Stadium from 1980 until 1994. The San Diego Chargers announced on January 12, 2017, that they would also relocate back to Los Angeles (the first since its inaugural season in 1960) and become the Los Angeles Chargers beginning in the 2017 NFL season and played at Dignity Health Sports Park in Carson, California for three seasons.[242] The Rams and the Chargers would soon move to the newly built SoFi Stadium, located in nearby Inglewood during the 2020 season.[243]

Los Angeles boasts a number of sports venues, including Dodger Stadium,[244] the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum,[245] BMO Stadium[246] and the Crypto.com Arena.[247] The Forum, SoFi Stadium, Dignity Health Sports Park, the Rose Bowl, Angel Stadium, and the Honda Center are also in adjacent cities and cities in Los Angeles's metropolitan area.[248]

Los Angeles has twice hosted the Summer Olympic Games: in 1932 and in 1984, and will host the games for a third time in 2028.[249] Los Angeles will be the third city after London (1908, 1948 and 2012) and Paris (1900, 1924 and 2024) to host the Olympic Games three times. When the tenth Olympic Games were hosted in 1932, the former 10th Street was renamed Olympic Blvd. Los Angeles also hosted the Deaflympics in 1985[250] and Special Olympics World Summer Games in 2015.[251]

Eight NFL Super Bowls were also held in the city and its surrounding areas - two at the Memorial Coliseum (the first Super Bowl, I and VII), five at the Rose Bowl in suburban Pasadena (XI, XIV, XVII, XXI, and XXVII), and one at the suburban Inglewood (LVI).[252] The Rose Bowl also hosts an annual and highly prestigious NCAA college football game called the Rose Bowl, which happens every New Year's Day.

Los Angeles also hosted eight FIFA World Cup soccer games at the Rose Bowl in 1994, including the final, where Brazil won. The Rose Bowl also hosted four matches in the 1999 FIFA Women's World Cup, including the final, where the United States won against China on penalty kicks. This was the game where Brandi Chastain took her shirt off after she scored the tournament-winning penalty kick, creating an iconic image. Los Angeles will be one of eleven U.S. host cities for the 2026 FIFA World Cup with matches set to be held at SoFi Stadium.[253]

Los Angeles is one of six North American cities to have won championships in all five of its major leagues (MLB, NFL, NHL, NBA and MLS), having completed the feat with the Kings' 2012 Stanley Cup title.[254]

Government

Los Angeles is a charter city as opposed to a general law city. The current charter was adopted on June 8, 1999, and has been amended many times.[255] The elected government consists of the Los Angeles City Council and the mayor of Los Angeles, which operate under a mayor–council government, as well as the city attorney (not to be confused with the district attorney, a county office) and controller. The mayor is Karen Bass.[256] There are 15 city council districts.

The city has many departments and appointed officers, including the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD),[257] the Los Angeles Board of Police Commissioners,[258] the Los Angeles Fire Department (LAFD),[259] the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles (HACLA),[260] the Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT),[261] and the Los Angeles Public Library (LAPL).[262]

The charter of the City of Los Angeles ratified by voters in 1999 created a system of advisory neighborhood councils that would represent the diversity of stakeholders, defined as those who live, work or own property in the neighborhood. The neighborhood councils are relatively autonomous and spontaneous in that they identify their own boundaries, establish their own bylaws, and elect their own officers. There are about 90 neighborhood councils.

Residents of Los Angeles elect supervisors for the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th supervisorial districts.

Federal and state representation

In the California State Assembly, Los Angeles is split between fourteen districts.[263] In the California State Senate, the city is split between eight districts.[264] In the United States House of Representatives, it is split among nine congressional districts.[265]

Crime

In 1992, the city of Los Angeles recorded 1,092 murders.[266] Los Angeles experienced a significant decline in crime in the 1990s and late 2000s and reached a 50-year low in 2009 with 314 homicides.[267][268] This is a rate of 7.85 per 100,000 population—a major decrease from 1980 when a homicide rate of 34.2 per 100,000 was reported.[269][270] This included 15 officer-involved shootings. One shooting led to the death of a SWAT team member, Randal Simmons, the first in LAPD's history.[271] Los Angeles in the year of 2013 totaled 251 murders, a decrease of 16 percent from the previous year. Police speculate the drop resulted from a number of factors, including young people spending more time online.[272] In 2021, murders rose to the highest level since 2008 and there were 348.[273]

In 2015, it was revealed that the LAPD had been under-reporting crime for eight years, making the crime rate in the city appear much lower than it really was.[274][275]

The Dragna crime family and Mickey Cohen dominated organized crime in the city during the Prohibition era[276] and reached its peak during the 1940s and 1950s with the "Battle of Sunset Strip" as part of the American Mafia, but has gradually declined since then with the rise of various black and Hispanic gangs in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[276]

According to the Los Angeles Police Department, the city is home to 45,000 gang members, organized into 450 gangs.[277] Among them are the Crips and Bloods, which are both African American street gangs that originated in the South Los Angeles region. Latino street gangs such as the Sureños, a Mexican American street gang, and Mara Salvatrucha, which has mainly members of Salvadoran descent, as well as other Central American descents, all originated in Los Angeles. This has led to the city being referred to as the "Gang Capital of America".[278]

Education

Colleges and universities

There are three public universities within the city limits: California State University, Los Angeles (CSULA), California State University, Northridge (CSUN) and University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).[279]

Private colleges in the city include:

- American Film Institute Conservatory[280]

- Alliant International University[281]

- American Academy of Dramatic Arts (Los Angeles Campus)[282]

- American Jewish University[283]

- Abraham Lincoln University[284]

- The American Musical and Dramatic Academy – Los Angeles campus

- Antioch University's Los Angeles campus[285]

- Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science[286]

- Colburn School[287]

- Columbia College Hollywood[288]

- Emerson College (Los Angeles Campus)[289]

- Emperor's College[290]

- Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising's Los Angeles campus (FIDM)

- Los Angeles Film School[291]

- Loyola Marymount University (LMU is also the parent university of Loyola Law School in Los Angeles)[292]

- Mount St. Mary's College[293]

- National University of California[294]

- Occidental College ("Oxy")[295]

- Otis College of Art and Design (Otis)[296]

- Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc)[297]

- Southwestern Law School[298]

- University of Southern California (USC)[299]

- Woodbury University[300]

The community college system consists of nine campuses governed by the trustees of the Los Angeles Community College District:

- East Los Angeles College (ELAC)[301]

- Los Angeles City College (LACC)[302]

- Los Angeles Harbor College[303]

- Los Angeles Mission College[304]

- Los Angeles Pierce College[305]

- Los Angeles Valley College (LAVC)[306]

- Los Angeles Southwest College[307]

- Los Angeles Trade-Technical College[308]

- West Los Angeles College[309]

There are numerous additional colleges and universities outside the city limits in the Greater Los Angeles area, including the Claremont Colleges consortium, which includes the most selective liberal arts colleges in the U.S., and the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), one of the top STEM-focused research institutions in the world.

Schools

Los Angeles Unified School District serves almost all of the city of Los Angeles, as well as several surrounding communities, with a student population around 800,000.[310] After Proposition 13 was approved in 1978, urban school districts had considerable trouble with funding. LAUSD has become known for its underfunded, overcrowded and poorly maintained campuses, although its 162 Magnet schools help compete with local private schools.

Several small sections of Los Angeles are in the Inglewood Unified School District,[311] and the Las Virgenes Unified School District.[312] The Los Angeles County Office of Education operates the Los Angeles County High School for the Arts.

Media

The Los Angeles metro area is the second-largest broadcast designated market area in the U.S. (after New York) with 5,431,140 homes (4.956% of the U.S.), which is served by a wide variety of local AM and FM radio and television stations. Los Angeles and New York City are the only two media markets to have seven VHF allocations assigned to them.[313]

The major daily English-language newspaper in the area is the Los Angeles Times.[314] La Opinión is the city's major daily Spanish-language paper.[315] The Korea Times is the city's major daily Korean-language paper while The World Journal is the city and county's major Chinese newspaper. The Los Angeles Sentinel is the city's major African-American weekly paper, boasting the largest African-American readership in the Western United States.[316] Investor's Business Daily is distributed from its LA corporate offices, which are headquartered in Playa del Rey.[317]

As part of the region's aforementioned creative industry, the Big Five major broadcast television networks, ABC, CBS, FOX, NBC, and The CW, all have production facilities and offices throughout various areas of Los Angeles. All four major broadcast television networks, plus major Spanish-language networks Telemundo and Univision, also own and operate stations that both serve the Los Angeles market and serve as each network's West Coast flagship station: ABC's KABC-TV (Channel 7),[318] CBS's KCBS-TV (Channel 2), Fox's KTTV-TV (Channel 11),[319] NBC's KNBC-TV (Channel 4),[320] The CW's KTLA-TV (Channel 5), MyNetworkTV's KCOP-TV (Channel 13), Telemundo's KVEA-TV (Channel 52), and Univision's KMEX-TV (Channel 34). The region also has four PBS member stations, with KCET, re-joining the network as secondary affiliate in August 2019, after spending the previous eight years as the nation's largest independent public television station. KTBN (Channel 40) is the flagship station of the religious Trinity Broadcasting Network, based out of Santa Ana. A variety of independent television stations, such as KCAL-TV (Channel 9), also operate in the area.

There are also a number of smaller regional newspapers, alternative weeklies and magazines, including the Los Angeles Register, Los Angeles Community News, (which focuses on coverage of the greater Los Angeles area), Los Angeles Daily News (which focuses coverage on the San Fernando Valley), LA Weekly, L.A. Record (which focuses coverage on the music scene in the Greater Los Angeles Area), Los Angeles Magazine, the Los Angeles Business Journal, the Los Angeles Daily Journal (legal industry paper), The Hollywood Reporter, Variety (both entertainment industry papers), and Los Angeles Downtown News.[321] In addition to the major papers, numerous local periodicals serve immigrant communities in their native languages, including Armenian, English, Korean, Persian, Russian, Chinese, Japanese, Hebrew, and Arabic. Many cities adjacent to Los Angeles also have their own daily newspapers whose coverage and availability overlaps with certain Los Angeles neighborhoods. Examples include The Daily Breeze (serving the South Bay), and The Long Beach Press-Telegram.

Los Angeles arts, culture and nightlife news is also covered by a number of local and national online guides, including Time Out Los Angeles, Thrillist, Kristin's List, DailyCandy, Diversity News Magazine, LAist, and Flavorpill.[322][323][324][325]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Freeways

The city and the rest of the Los Angeles metropolitan area are served by an extensive network of freeways and highways. Texas Transportation Institute's annual Urban Mobility Report ranked Los Angeles area roads the most congested in the United States in 2019 as measured by annual delay per traveler, area residents experiencing a cumulative average of 119 hours waiting in traffic that year.[326] Los Angeles was followed by San Francisco/Oakland, Washington, D.C., and Miami. Despite the congestion in the city, the mean daily travel time for commuters in Los Angeles is shorter than other major cities, including New York City, Philadelphia and Chicago. Los Angeles's mean travel time for work commutes in 2006 was 29.2 minutes, similar to those of San Francisco and Washington, D.C.[327]

The major highways that connect LA to the rest of the nation include Interstate 5, which runs south through San Diego to Tijuana in Mexico and north through Sacramento, Portland, and Seattle to the Canada–US border; Interstate 10, the southernmost east–west, coast-to-coast Interstate Highway in the United States, going to Jacksonville, Florida; and U.S. Route 101, which heads to the California Central Coast, San Francisco, the Redwood Empire, and the Oregon and Washington coasts.

Buses

The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (LACMTA; branded as Metro) and other regional agencies provide a comprehensive bus system that covers Los Angeles County. While the Los Angeles Department of Transportation is responsible for contracting local and commuter bus services primarily within the city limits of Los Angeles and several immediate neighboring municipalities in southwest Los Angeles County,[328] the largest bus system in the city is operated by Metro.[329] Called Los Angeles Metro Bus, the system consists of 117 routes (excluding Metro Busway) throughout Los Angeles and neighboring cities primarily in southwestern Los Angeles County, with most routes following along a particular street in the city's street grid and run to or through Downtown Los Angeles.[330] As of the third quarter of 2023, the system had an average ridership of approximately 692,500 per weekday, with a total of 197,950,700 riders in 2022.[331] Metro also runs two Metro Busway lines, the G and J lines, which are bus rapid transit lines with stops and frequencies similar to those of Los Angeles's light rail system.

There are also smaller regional public transit systems that mainly serve specific cities or regions in Los Angeles County. For example, the Big Blue Bus provides extensive bus service in Santa Monica and western Los Angeles County, while Foothill Transit focuses on routes in the San Gabriel Valley in southeast Los Angeles County with one express route going into downtown Los Angeles. Los Angeles World Airports also runs two frequent FlyAway express bus routes (via freeways) from Los Angeles Union Station and Van Nuys to Los Angeles International Airport.[332]

While cash is accepted on all buses, the primary payment method for Los Angeles Metro Bus, Metro Busway, and 27 other regional bus agencies is a TAP card, a contactless stored-value card.[333] According to the 2016 American Community Survey, 9.2% of working Los Angeles (city) residents made the journey to work via public transportation.[334]

Rail

The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority also operate a subway and light rail system across Los Angeles and its county. The system is called Los Angeles Metro Rail and consists of the B and D subway lines, as well as the A, C, E, and K light rail lines.[330] TAP cards are required for all Metro Rail trips.[335] As of the third quarter of 2023, the city's subway system is the ninth busiest in the United States, and its light rail system is the country's second busiest.[331] In 2022, the system had a ridership of 57,299,800, or about 189,200 per weekday, in the third quarter of 2023.[331]

Since the opening of the first line, the A Line, in 1990, the system has been extended significantly, with more extensions currently in progress. Today, the system serves numerous areas across the county on 107.4 mi (172.8 km) of rail, including Long Beach, Pasadena, Santa Monica, Norwalk, El Segundo, North Hollywood, Inglewood, and Downtown Los Angeles. As of 2023, there are 101 stations in the Metro Rail system.[336]

Los Angeles is also center of its county's commuter rail system, Metrolink, which links Los Angeles to Ventura, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, and San Diego Counties. The system consists of eight lines and 69 stations operating on 545.6 miles (878.1 kilometres) of track.[337] Metrolink averages 42,600 trips per weekday, the busiest line being the San Bernardino Line.[338] Apart from Metrolink, Los Angeles is also connected to other cities by intercity passenger trains from Amtrak on five different lines.[339] One of the lines is the Pacific Surfliner route which operates multiple daily round trips between San Diego and San Luis Obispo, California through Union Station.[340] It is Amtrak's busiest line outside the Northeast Corridor.[341]

The main rail station in the city is Union Station which opened in 1939, and it is the largest passenger rail terminal in the Western United States.[342] The station is a major regional train station for Amtrak, Metrolink and Metro Rail. The station is Amtrak's fifth busiest station, having 1.4 million Amtrak boardings and de-boardings in 2019.[343] Union Station also offers access to Metro Bus, Greyhound, LAX FlyAway, and other buses from different agencies.[344]

Airports

The main international and domestic airport serving Los Angeles is Los Angeles International Airport (IATA: LAX, ICAO: KLAX), commonly referred to by its airport code, LAX.[345] It is located on the Westside of Los Angeles near the Sofi Stadium in Inglewood.

Other major nearby commercial airports include:

- (IATA: ONT, ICAO: KONT) Ontario International Airport, owned by the city of Ontario, CA; serves the Inland Empire.[346]

- (IATA: BUR, ICAO: KBUR) Hollywood Burbank Airport, jointly owned by the cities of Burbank, Glendale, and Pasadena. Formerly known as Bob Hope Airport and Burbank Airport, the closest airport to Downtown Los Angeles serves the San Fernando, San Gabriel, and Antelope Valleys.[347]

- (IATA: LGB, ICAO: KLGB) Long Beach Airport, serves the Long Beach/Harbor area.[348]

- (IATA: SNA, ICAO: KSNA) John Wayne Airport of Orange County.

One of the world's busiest general-aviation airports is also in Los Angeles: Van Nuys Airport (IATA: VNY, ICAO: KVNY).[349]

Seaports

The Port of Los Angeles is in San Pedro Bay in the San Pedro neighborhood, approximately 20 miles (32 km) south of Downtown. Also called Los Angeles Harbor and WORLDPORT LA, the port complex occupies 7,500 acres (30 km2) of land and water along 43 miles (69 km) of waterfront. It adjoins the separate Port of Long Beach.[350]

The sea ports of the Port of Los Angeles and Port of Long Beach together make up the Los Angeles/Long Beach Harbor.[351][352] Together, both ports are the fifth busiest container port in the world, with a trade volume of over 14.2 million TEU's in 2008.[353] Singly, the Port of Los Angeles is the busiest container port in the United States and the largest cruise ship center on the West Coast of the United States – The Port of Los Angeles's World Cruise Center served about 590,000 passengers in 2014.[354]

There are also smaller, non-industrial harbors along Los Angeles's coastline. The port includes four bridges: the Vincent Thomas Bridge, Henry Ford Bridge, Long Beach International Gateway Bridge, and Commodore Schuyler F. Heim Bridge. Passenger ferry service from San Pedro to the city of Avalon (and Two Harbors) on Santa Catalina Island is provided by Catalina Express.

Notable people

Sister cities

Los Angeles has 25 sister cities,[355] listed chronologically by year joined:

Eilat, Israel (1959)

Eilat, Israel (1959) Nagoya, Japan (1959)

Nagoya, Japan (1959) Salvador, Brazil (1962)

Salvador, Brazil (1962) Bordeaux, France (1964)[356][357]

Bordeaux, France (1964)[356][357] Berlin, Germany (1967)[358]

Berlin, Germany (1967)[358] Lusaka, Zambia (1968)

Lusaka, Zambia (1968) Mexico City, Mexico (1969)

Mexico City, Mexico (1969) Auckland, New Zealand (1971)

Auckland, New Zealand (1971) Busan, South Korea (1971)

Busan, South Korea (1971) Mumbai, India (1972)

Mumbai, India (1972) Tehran, Iran (1972)

Tehran, Iran (1972) Taipei, Taiwan (1979)

Taipei, Taiwan (1979) Guangzhou, China (1981)[359]

Guangzhou, China (1981)[359] Athens, Greece (1984)

Athens, Greece (1984) Saint Petersburg, Russia (1984)

Saint Petersburg, Russia (1984) Vancouver, Canada (1986)[360]

Vancouver, Canada (1986)[360] Giza, Egypt (1989)

Giza, Egypt (1989) Jakarta, Indonesia (1990)

Jakarta, Indonesia (1990) Kaunas, Lithuania (1991)

Kaunas, Lithuania (1991) Makati, Philippines (1992)

Makati, Philippines (1992) Split, Croatia (1993)[361]

Split, Croatia (1993)[361] San Salvador, El Salvador (2005)

San Salvador, El Salvador (2005) Beirut, Lebanon (2006)

Beirut, Lebanon (2006) Ischia, Campania, Italy (2006)

Ischia, Campania, Italy (2006) Yerevan, Armenia (2007)[362]

Yerevan, Armenia (2007)[362]

In addition, Los Angeles has the following "friendship cities":

See also

- Largest cities in Southern California

- Largest cities in the Americas

- List of hotels in Los Angeles

- List of largest houses in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area

- List of museums in Los Angeles

- List of museums in Los Angeles County, California

- List of music venues in Los Angeles

- List of people from Los Angeles

- List of tallest buildings in Los Angeles

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Los Angeles, California

- USS Los Angeles, 4 ships (including 1 airship)

Notes

- ^ US: /lɔːs ˈændʒələs/ lawss AN-jəl-əss; Spanish: Los Ángeles [los ˈaŋxeles], lit. 'The Angels'

References

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c Gollust, Shelley (April 18, 2013). "Nicknames for Los Angeles". Voice of America. Archived from the original on July 6, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ^ Barrows, H.D. (1899). "Felepe de Neve". Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly. Vol. 4. p. 151ff. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "This 1835 Decree Made the Pueblo of Los Angeles a Ciudad – And California's Capital". KCET. April 2016. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (DOC) on February 21, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ "About the City Government". City of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b "2021 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 7, 2021. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c d "QuickFacts: Los Angeles city, California". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ "List of 2020 Census Urban Areas". census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ "2020 Population and Housing State Data". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ "Angelino, Angeleno, and Angeleño". KCET. January 10, 2011. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ "Definition of Angeleno". Merriam-Webster. May 16, 2023. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ "Total Gross Domestic Product for Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA (MSA)". Federal Reserve Economic Data. Archived from the original on November 26, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ "Total Gross Domestic Product for Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA (MSA)". fred.stlouisfed.org. Archived from the original on June 16, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ "Total Gross Domestic Product for Oxnard-Thousand Oaks-Ventura, CA (MSA)". fred.stlouisfed.org. Archived from the original on June 16, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ Zip Codes Within the City of Los Angeles Archived July 13, 2017, at the Wayback Machine – LAHD

- ^ "Slowing State Population Decline puts Latest Population at 39,185,000" (PDF). dof.ca.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2022. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ "America's 10 most visited cities" Archived June 14, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, World Atlas, September 23, 2021