Мюнхен

Мюнхен | |

|---|---|

Location of Munich | |

| Coordinates: 48°08′15″N 11°34′30″E / 48.13750°N 11.57500°E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Bavaria |

| Admin. region | Upper Bavaria |

| District | Urban district |

| First mentioned | 1158 |

| Subdivisions | |

| Government | |

| • Lord mayor (2020–26) | Dieter Reiter (SPD) |

| • Governing parties | Greens / SPD |

| Area | |

| • City | 310.71 km2 (119.97 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 520 m (1,710 ft) |

| Population (2022-12-31)[2] | |

| • City | 1,512,491 |

| • Density | 4,900/km2 (13,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 2,606,021 |

| • Metro | 5,991,144[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 80331–81929 |

| Dialling codes | 089 |

| Vehicle registration | M, MUC |

| Website | stadt.muenchen.de |

Мюнхен ( / mjuːnɪk -nɪx ; ɪ nik , ] München немецкий / MEW - ( [ : h ˈmʏnçn̩ ) ) [3] Столица и самый густонаселенный город Свободного государства Бавария Германии в . С населением 1 589 706 человек по состоянию на 29 февраля 2024 года. [4] это третий по величине город Германии после Берлина и Гамбурга и, следовательно, самый крупный город, не входящий в состав отдельного государства, а также 11-й по величине город в Европейском Союзе . проживает В столичном регионе города около 6,2 миллиона человек, и он является третьим по величине мегаполисом по ВВП в Европейском Союзе. [5]

Расположенный на берегах реки Изар к северу от Альп , Мюнхен является резиденцией баварского административного региона Верхняя Бавария и в то же время является самым густонаселенным муниципалитетом в Германии с плотностью населения 4500 человек на км. 2 . Мюнхен — второй по величине город в регионе баварского диалекта после австрийской столицы Вены .

The city was first mentioned in 1158. Catholic Munich strongly resisted the Reformation and was a political point of divergence during the resulting Thirty Years' War, but remained physically untouched despite an occupation by the Protestant Swedes.[6] Once Bavaria was established as the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1806, Munich became a major European centre of arts, architecture, culture and science. In 1918, during the German Revolution of 1918–19, the ruling House of Wittelsbach, which had governed Bavaria since 1180, was forced to abdicate in Munich and a short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic was declared. In the 1920s, Munich became home to several political factions, among them the Nazi Party. After the Nazis' rise to power, Munich was declared their "Capital of the Movement". The city was heavily bombed during World War II, but has restored most of its old town and boasts nearly 30.000 buildings from before the war all over the city.[7] После окончания послевоенной американской оккупации в 1949 году в годы Wirtschaftswunder произошел значительный рост населения и экономической мощи . Город принимал летние Олимпийские игры 1972 года .

Today, Munich is a global centre of science, technology, finance, innovation, business, and tourism. Munich enjoys a very high standard and quality of living, reaching first in Germany and third worldwide according to the 2018 Mercer survey,[8] and being rated the world's most liveable city by the Monocle's Quality of Life Survey 2018.[9] Munich is consistently ranked as one of the most expensive cities in Germany in terms of real estate prices and rental costs.[10][11]

In 2021, 28.8 percent of Munich's residents were foreigners, and another 17.7 percent were German citizens with a migration background from a foreign country.[12] Munich's economy is based on high tech, automobiles, and the service sector, as well as IT, biotechnology, engineering, and electronics. It has one of the strongest economies of any German city and the lowest unemployment rate of all cities in Germany with more than one million inhabitants. The city houses many multinational companies, such as BMW, Siemens, Allianz SE and Munich Re. In addition, Munich is home to two research universities, and a multitude of scientific institutions.[13] Munich's numerous architectural and cultural attractions, sports events, exhibitions and its annual Oktoberfest, the world's largest Volksfest, attract considerable tourism.[14]

History[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Munich was a tiny 8th-century friar settlement, which was named zu den Munichen ("to the monks"). The Old High German Muniche served as the basis for the modern German city name München.[15]

Prehistory[edit]

The river Isar was a prehistoric trade route and in the Bronze Age Munich was among the largest raft ports in Europe.[16] Bronze Age settlements up to four millennia old have been discovered.[17] Evidence of Celtic settlements from the Iron Age have been discovered in areas around Ramersdorf-Perlach.[18]

Roman period[edit]

The ancient Roman road Via Julia, which connected Augsburg and Salzburg, crossed over the Isar south of Munich, at the towns of Baierbrunn and Gauting.[19] A Roman settlement north-east of Munich was excavated in the neighborhood of Denning.[20]

Post-Roman settlements[edit]

Starting in the 6th century, the Baiuvarii populated the area around what is now modern Munich, such as in Johanneskirchen, Feldmoching, Bogenhausen and Pasing.[21][22] The first known Christian church was built ca. 815 in Fröttmanning.[23]

Origin of medieval town[edit]

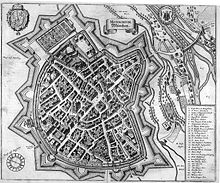

The first medieval bridges across the river Isar were located in current city areas of Munich and Landshut.[16] The Duke of Saxony and Bavaria Henry the Lion founded the town of Munich in his territory to control the salt trade, after having burned down the town of Föhring and its bridges over the Isar.[24] Historians date this event at about 1158.[25] The layout of Munich city, with five city gates and market place, resembled that of Höxter.[26]

Henry built a new toll bridge, customs house and a coin market closer to his home somewhat upstream at a settlement around the area of modern old town Munich. This new toll bridge most likely crossed the Isar where the Museuminsel and the modern Ludwigsbrücke is now located.[27]

Otto of Freising protested to his nephew, Emperor Frederick Barbarosa (d. 1190). However, on 14 June 1158, in Augsburg, the conflict was settled in favor of Duke Henry. The Augsburg Arbitration mentions the name of the location in dispute as forum apud Munichen. Although Bishop Otto had lost his bridge, the arbiters ordered Duke Henry to pay a third of his income to the Bishop in Freising as compensation.[28][29][30]

The 14th June 1158 is considered the official founding day of the city of Munich. Archaeological excavations at Marienhof Square (near Marienplatz) in advance of the expansion of the S-Bahn (subway) in 2012 discovered shards of vessels from the 11th century, which prove again that the settlement of Munich must be older than the Augsburg Arbitration of 1158.[31][32] The old St. Peter's Church near Marienplatz is also believed to predate the founding date of the town.[33]

In 1175, Munich received city status and fortification. In 1180, after Henry the Lion's fall from grace with Emperor Frederick Barbarosa, including his trial and exile, Otto I Wittelsbach became Duke of Bavaria, and Munich was handed to the Bishop of Freising. In 1240, Munich was transferred to Otto II Wittelsbach and in 1255, when the Duchy of Bavaria was split in two, Munich became the ducal residence of Upper Bavaria.

Duke Louis IV, a native of Munich, was elected German king in 1314 and crowned as Holy Roman Emperor in 1328. He strengthened the city's position by granting it the salt monopoly, thus assuring it of additional income.

On 13 February 1327, a large fire broke out in Munich that lasted two days and destroyed about a third of the town.[34]

In 1349, the Black Death ravaged Munich and Bavaria.[35]

In the 15th century, Munich underwent a revival of Gothic arts: the Old Town Hall was enlarged, and Munich's largest Gothic church – the Frauenkirche – now a cathedral, was constructed in only 20 years, starting in 1468.

Capital of reunited Bavaria[edit]

When Bavaria was reunited in 1506 after a brief war against the Duchy of Landshut, Munich became its capital. The arts and politics became increasingly influenced by the court.[citation needed] The Renaissance movement beset Munich and the Bavarian branch of the House of Wittelsbach under the Duke of Bavaria Albrecht V who bolstered their prestige by conjuring up a lineage that reached back to Classical antiquity. In 1568 Albrecht V built the Antiquarium to house the Wittelsbach collection of Greek and Roman antiquities in the Munich Residenz.[36] Albrecht V appointed the composer Orlando di Lasso as director of the court orchestra and tempted numerous Italian musicians to work at the Munich court, establishing Munich as a hub for late Renaissance music.[37] During the rule of Duke William V Munich began to be called the "German Rome" and William V began presenting Emperor Charlemagne as ancestor of the Wittelsbach dynasty.[38]

Duke William V further cemented the Wittelsbach rule by commissioning the Jesuit Michaelskirche. He had the sermons of his Jesuit court preacher Jeremias Drexel translated from Latin into German and published them to a greater audience.[39] William V was addressed with the epithet "the Pious" and like his contemporary Wittelsbach dukes promoted himself as "father of the land" (Landesvater), encouraged pilgrimages and Marian devotions.[40] William V had the Hofbräuhaus built in 1589. It would become the prototype for beer halls across Munich. After World War II the Residenze, the Hofbräuhaus, the Frauenkirche, and the Peterskirche were reconstructed to look exactly as they did before the Nazi Party seized power in 1933.[41]

The Catholic League was founded in Munich in 1609. In 1623, during the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), Munich became an electoral residence when Maximilian I, Duke of Bavaria was invested with the electoral dignity, but in 1632 the city was occupied by Gustav II Adolph of Sweden.[citation needed]

In 1634 Swedish and Spanish troops advanced on Munich. Maximilian I published a plague ordinance to halt an epidemic escalation.[42] The bubonic plague nevertheless ravaged Munich and the surrounding countryside in 1634 and 1635.[43] During the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) troops again converged on Munich in 1647 and precautions were taken, so as to avoid another epidemic.[44]

Under the regency of the Bavarian electors, Munich was an important centre of Baroque life, but also had to suffer under Habsburg occupations in 1704 and 1742.[citation needed] When Maximilian III Joseph, Elector of Bavaria died in 1745, the succession empowered the Palatinate branch within the House of Wittelsbach.[45]

In 1777 Bavarian lands were inherited to Charles Theodore. The new Duke was disliked by the citizens of Munich for his supposedly enlightened ideas. In 1785 Karl Theodor invited Count Rumford Benjamin Thompson to take up residency in Munich and implement stringent social reforms. The poor were forced to live in newly built workhouses. The Bavarian army was restructured, with common soldiers receiving better food and reassurances that they would be treated humanely by officers.[46] Munich was the largest German city to lose fortification in the 1790s.[47] In 1791 Karl Theodor and Count Rumford started to demolish Munich's fortifications.[48] After 1793 Munich's citizens, including house servants, carpenters, butchers, merchants, and court officials, seized the opportunity, building new houses, stalls, and sheds outside the city walls.[49]

After making an alliance with Napoleonic France, the city became the capital of the new Kingdom of Bavaria in 1806 with Elector Maximillian Joseph becoming its first King. The state parliament (the Landtag) and the new archdiocese of Munich and Freising were also located in the city.[citation needed]

The establishment of Bavarian state sovereignty profoundly affected Munich. Munich became the center of a modernizing kingdom, and one of the king's first acts was the secularization of Bavaria. He had dissolved all monasteries in 1802 and once crowned, Max Joseph I generated state revenues by selling off church lands. While many monasteries were reestablished, Max Joseph I succeeded in controlling the right to brew beer (Brauchrecht). The king handed the brewing monopoly to Munich's wealthiest brewers, who in turn paid substantial taxes on their beer production. In 1807 the king abolished all ordinances that limited the number of apprentices and journeymen a brewery could employ. Munich's population had swelled and Munich brewers were now free to employ as many workers as they needed to meet the demand.[50] In October 1810 a beer festival was held on the meadows just outside Munich to commemorate the wedding of the crown prince and princess Therese of Saxe-Hildburghausen. The parades in regional dress (Tracht) represented the diversity of the kingdom. The fields are now part of the Theresienwiese and the celebrations developed into Munich's annual Oktoberfest.[51]

The Bavarian state proceeded to take control over the beer market, by regulating all taxes on beer in 1806 and 1811. Brewers and the beer taverns (Wirtshäuser) were taxed, and the state also controlled the quality of beer while limiting the competition among breweries.[52] In 1831 the king's government introduced a cost-of-living allowance on beer for lower-ranking civil servants and soldiers. Soldiers stationed in Munich were granted a daily allowance for beer in the early 1840s.[53] By the 1850s beer had become essential staple food for Munich's working and lower classes. Since the Middle Ages beer had been regarded as nutritious liquid bread (fließendes Brot) in Bavaria. But Munich suffered from poor water sanitation and as early as the 1700s beer came to be regarded as the fifth element. Beer was essential in maintaining public health in Munich and in the mid-1840s Munich police estimated that at least 40,000 residents relied primarily on beer for their nutrition.[54]

In 1832 Peter von Hess painted the Greek War of Independence at the order of Ludwig I of Bavaria. Ludwig I had the Königsplatz built in neoclassicism as a matter of ideological choice. Leo von Klenze supervised the construction of a Propylaia between 1854 and 1862.[55]

During the early to mid-19th century, the old fortified city walls of Munich were largely demolished due to population expansion.[56] The first Munich railway station was built in 1839, with a line going to Augsburg in the west. By 1849 a newer Munich Central Train Station (München Hauptbahnhof) was completed, with a line going to Landshut and Regensburg in the north.[57][58] In 1825 Ludwig I had ascended to the throne and commissioned leading architects such as Leo von Klenze to design a series of public museums in neoclassical style. The grand building projects of Ludwig I gave Munich the endearment "Isar-Athen" and "Monaco di Bavaria".[59] Between 1856 and 1861 the court gardener Carl von Effner landscaped the banks of the river Isar and established the Maximilian Gardens. From 1848 the Münchner Neueste Nachrichten was published as a regional newspaper in Munich. In 1857 the construction of the Maximilianeum was begun.[60]

By the time Ludwig II became king in 1864, he remained mostly aloof from his capital and focused more on his fanciful castles in the Bavarian countryside, which is why he is known the world over as the 'fairytale king'. Ludwig II tried to lure Richard Wagner to Munich, but his plans for an opera house were declined by the city council. Ludwig II nevertheless generated a windfall for Munich's craft and construction industries. In 1876 Munich hosted the first German Art and Industry Exhibition, which showcased the northern Neo-Renaissance fashion that came to be the German Empire's predominant style. Munich based artists put on the German National Applied Arts Exhibition in 1888, showcasing Baroque Revival architecture and Rococo Revival designs.[61]

In 1900 Wilhelm Röntgen moved to Munich, he was appointed as professor of Physics. In 1901 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics.[62]

The Prince Regent Luitpold's reign from 1886 to 1912 was marked by tremendous artistic and cultural activity in Munich.[63] At the dawn of the 20th century Munich was an epicenter for the Jugendstil movement, combining a liberal magazine culture with progressive industrial design and architecture. The German art movement took its name from the Munich magazine Die Jugend (The Youth).[64] Prominent Munich Jugendstil artists include Hans Eduard von Berlepsch-Valendas, Otto Eckmann,[65] Margarethe von Brauchitsch, August Endell, Hermann Obrist, Wilhelm von Debschitz,[66] and Richard Riemerschmid. In 1905 two large department stores opened in Munich, the Kaufhaus Oberpollinger and the Warenhaus Hermann Tietz, both had been designed by the architect Max Littmann.[67] In 1911 the expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter was established in Munich. Its founding members include Gabriele Münter.[68]

World War I to World War II[edit]

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, life in Munich became very difficult, as the Allied blockade of Germany led to food and fuel shortages. During French air raids in 1916, three bombs fell on Munich.[citation needed]

In 1916, the 'Bayerische Motoren Werke' (BMW) produced its first aircraft engine in Munich.[69] The stock cooperation BMW AG was founded in 1918, with Camillo Castiglioni owning one third of the share capital. In 1922 BMW relocated its headquarters to a factory in Munich.[70]

After World War I, the city was at the centre of substantial political unrest. In November 1918, on the eve of the German revolution, Ludwig III of Bavaria and his family fled the city. After the murder of the first republican premier of Bavaria Kurt Eisner in February 1919 by Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley, the Bavarian Soviet Republic was proclaimed.[71] The November 1918 revolution ended the reign of the Wittelsbach in Bavaria.[72] In Mein Kampf Adolf Hitler described his political activism in Munich after November 1918 as the "Beginning of My Political Activity". Hitler called the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic "the rule of the Jews".[73] In 1919 Bavaria Film was founded and in the 1920s Munich offered film makers an alternative to Germany's largest film studio, Babelsberg Studio.[74]

In 1923 Gustav von Kahr was appointed Bavarian prime minister and immediately planned for the expulsion of all Jews who did not hold German citizenship. Chief of Police Ernst Pöhner and Wilhelm Frick openly indulged in antisemitism, while Bavarian judges praised people on the political right as patriotic for their crimes and handed down mild sentences.[75] In 1923, Adolf Hitler and his supporters, who were concentrated in Munich, staged the Beer Hall Putsch, an attempt to overthrow the Weimar Republic and seize power. The revolt failed, resulting in Hitler's arrest and the temporary crippling of the Nazi Party (NSDAP).[76]

Munich was chosen as capital for the Free State of Bavaria and acquired increased responsibility for administering the city itself and the surrounding districts. Offices needed to be built for bureaucracy, so a 12-story office building was erected in the southern part of the historic city centre in the late 1920s.[72]

Munich again became important to the Nazis when they took power in Germany in 1933. The party created its first concentration camp at Dachau, 16 km (10 mi) north-west of the city. Because of its importance to the rise of National Socialism, Munich was referred to as the Hauptstadt der Bewegung ("Capital of the Movement").[77]

The NSDAP headquarters and the documentation apparatus for controlling all aspects of life were located in Munich. Nazi organizations, such as the National Socialist Women's League and the Gestapo, had their offices along Brienner Straße and around the Königsplatz. The party acquired 68 buildings in the area and many Führerbauten ("Führer buildings") were built to reflect a new aesthetic of power.[78] Construction work for the Führerbau and the party headquarters (known as the Brown House) started in September 1933.[79] The Haus der Kunst (House of German Art) was the first building to be commissioned by Hitler. The architect Paul Troost was asked to start work shortly after the Nazis had seized power because "the most German of all German cities" was left with no exhibition building when in 1931 the Glass Palace was destroyed in an arson attack.[80] The Red Terror that supposedly preceded Nazi control in Munich was detailed in Nazi publications; seminal accounts are that of Rudolf Schricker Rotmord über München published in 1934, and Die Blutchronik des Marxismus in Deutschland by Adolf Ehrt and Hans Roden.[81]

In 1930 Feinkost Käfer was founded in Munich, the Käfer catering business is now a world leading party service.[82]

The city was the site where the 1938 Munich Agreement signed between the United Kingdom and the Third French Republic with Nazi Germany as part of the Franco-British policy of appeasement. The British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain assented to the German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland in the hopes of satisfying Hitler's territorial expansion.[83]

The Munich-Riem Airport was completed in October 1939.[84]

On 8 November 1939, shortly after the Second World War had begun, Georg Elser planted a bomb in the Bürgerbräukeller in Munich in an attempt to assassinate Adolf Hitler, who held a political party speech. Hitler, however, had left the building minutes before the bomb went off.[85] By mid 1942 the majority of Jews living in Munich and the suburbs had been deported.[86]

During the war, Munich was the location of multiple forced labour camps, including two Polenlager camps for Polish youth,[87][88] and 40 subcamps of the Dachau concentration camp, in which men and women of various nationalities were held.[89] With up to 17,000 prisoners in 1945, the largest subcamp of Dachau was the Munich-Allach concentration camp.

Munich was the base of the White Rose, a student resistance movement. The group had distributed leaflets in several cities and following the 1943 Battle of Stalingrad members of the group stenciled slogans such as "Down with Hitler" and "Hitler the Mass Murderer" on public buildings in Munich. The core members were arrested and executed after Sophie Scholl and her brother Hans Scholl were caught distributing leaflets on Munich University campus calling upon the youth to rise against Hitler.[90]

The city was heavily damaged by the bombing of Munich in World War II, with 71 air raids over five years. US troops liberated Munich on 30 April 1945.[91]

Postwar[edit]

In the aftermath of World War II, Germany and Japan were subject to US Military occupation.[92] Due to Polish annexation of the Former eastern territories of Germany and expulsion of Germans from all over Eastern Europe, Munich operated over a thousand refugee camps for 151,113 people in October 1946.[93] After US occupation Munich was completely rebuilt following a meticulous plan, which preserved its pre-war street grid, bar a few exceptions owing to then modern traffic concepts. In 1957, Munich's population surpassed one million. The city continued to play a highly significant role in the German economy, politics and culture, giving rise to its nickname Heimliche Hauptstadt ("secret capital") in the decades after World War II.[94] In Munich, the Bayerischer Rundfunk began its first television broadcast in 1954.[95]

The Free State of Bavaria used the arms industry as kernel for its high tech development policy.[96] Since 1963, Munich has been hosting the Munich Security Conference, held annually in the Hotel Bayerischer Hof.[97] Munich also became known on the political level due to the strong influence of Bavarian politician Franz Josef Strauss from the 1960s to the 1980s. The Munich Airport, which commenced operations in 1992, was named in his honor.[98]

In the early 1960s Dieter Kunzelmann was expelled from the Situationist International and founded an influential group called Subversive Aktion in Munich. Kunzelmann was also active in West Berlin, and became known for using situationist avant-garde as a cover for political violence.[99]

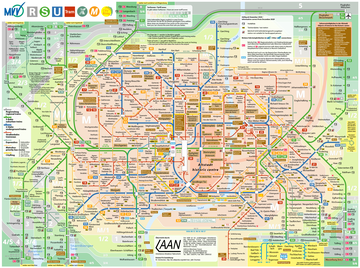

Munich hosted the 1972 Summer Olympics. After winning the bid in 1966 the Mayor of Munich Hans-Jochen Vogel accelerated the construction of the U-Bahn subway and the S-Bahn metropolitan commuter railway. In May 1967 the construction work began for a new U-Bahn line connecting the city with the Olympic Park. The Olympic Park subway station was built near the BMW Headquarters and the line was completed in May 1972, three months before the opening of the 1972 Summer Olympics. Shortly before the opening ceremony, Munich also inaugurated a sizable pedestrian priority zone between Karlsplatz and Marienplatz.[100] In 1970 the Munich city council released funds so that the iconic gothic facade and Glockenspiel of the New City Hall (Neues Rathaus) could be restored.[101]

During the 1972 Summer Olympics 11 Israeli athletes were murdered by Palestinian terrorists in the Munich massacre, when gunmen from the Palestinian "Black September" group took hostage members of the Israeli Olympic team.[102]

The most deadly militant attack the Federal Republic of Germany has ever witnessed was the Oktoberfest bombing. The attack was eventually blamed on militant Neo-Nazism.[103]

Munich and its urban sprawl emerged as the leading German high tech region during the 1980s and 1990s. The urban economy of Munich became characterized by a dynamic labour market, low unemployment, a growing service economy and high per capita income.[96] Munich is home of the famous Nockherberg Strong Beer Festival during the Lenten fasting period (usually in March). Its origins go back to the 17th/18th century, but has become popular when the festivities were first televised in the 1980s. The fest includes comical speeches and a mini-musical in which numerous German politicians are parodied by look-alike actors.[104]

In 2007 the ecological restoration of the river Isar in the urban area of Munich was awarded the Water Development Prize by the German Association for Water, Wastewater and Waste (known as DWA in German). The renaturation of the Isar allows for the near natural development of the river bed and is part of Munich's flood protection.[105] About 20 percent of buildings in Munich now have a green roof. Munich city council has been encouraging better stormwater management since the 1990s with regulations and subsidies.[106]

On the fifth anniversary of the 2011 Norway attacks an active shooter perpetrated a hate crime. The 2016 Munich shooting targeted people of Turkish and Arab descent.[107]

Munich was one of the host cities for UEFA Euro 2020, which was delayed for a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany, and is planned to be a host city for UEFA Euro 2024.[108]

Geography[edit]

Topography[edit]

Munich lies on the elevated plains of Upper Bavaria, about 50 km (31 mi) north of the northern edge of the Alps, at an altitude of about 520 m (1,706 ft) ASL. The local rivers are the Isar and the Würm. Munich is situated in the Northern Alpine Foreland. The northern part of this sandy plateau includes a highly fertile flint area which is no longer affected by the folding processes found in the Alps, while the southern part is covered with morainic hills. Between these are fields of fluvio-glacial out-wash, such as around Munich. Wherever these deposits get thinner, the ground water can permeate the gravel surface and flood the area, leading to marshes as in the north of Munich.

Climate[edit]

Munich is near the Alps. It has an oceanic climate (Cfb) in the Köppen climate classification. Annual variation in temperature can be significant, because there are no large bodies of water nearby. The winter in Munich is generally cold and overcast, and some Munich winters have significant snow. January is the coldest month. While winter averages remain only moderately cold, and relatively mild for an elevated inland location of Munich's latitude, inversion from the nearby Alps causes cold air to sink and result in temperatures below −15 °C (5 °F). In Munich the summer is usually pleasantly warm, with daytime temperatures averaging 25 °C (77 °F)

Munich is subject to active convective seasons and sometimes damaging events. The Alpine thunderstorm system moves along the mountain range, or detaches, heading east-north-east over the foothills of the Alps.[109]

At Munich's official weather stations, the highest and lowest temperatures ever measured are 37.5 °C (100 °F), on 27 July 1983 in Trudering-Riem, and −31.6 °C (−24.9 °F), on 12 February 1929 in the Botanic Garden of the city.[110][111]

| Climate data for Munich (Dreimühlenviertel) (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1954–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.9 (66.0) | 21.4 (70.5) | 24.0 (75.2) | 32.2 (90.0) | 31.8 (89.2) | 35.2 (95.4) | 37.5 (99.5) | 37.0 (98.6) | 31.8 (89.2) | 28.2 (82.8) | 24.2 (75.6) | 21.7 (71.1) | 37.5 (99.5) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 11.8 (53.2) | 13.7 (56.7) | 18.9 (66.0) | 23.6 (74.5) | 27.5 (81.5) | 30.5 (86.9) | 31.9 (89.4) | 31.5 (88.7) | 26.8 (80.2) | 22.6 (72.7) | 17.0 (62.6) | 12.6 (54.7) | 33.1 (91.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.0 (39.2) | 5.6 (42.1) | 10.1 (50.2) | 15.2 (59.4) | 19.4 (66.9) | 22.9 (73.2) | 24.9 (76.8) | 24.7 (76.5) | 19.6 (67.3) | 14.5 (58.1) | 8.2 (46.8) | 4.8 (40.6) | 14.5 (58.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) | 1.9 (35.4) | 5.7 (42.3) | 10.2 (50.4) | 14.3 (57.7) | 17.8 (64.0) | 19.6 (67.3) | 19.4 (66.9) | 14.7 (58.5) | 10.1 (50.2) | 4.9 (40.8) | 1.8 (35.2) | 10.1 (50.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −1.8 (28.8) | −1.4 (29.5) | 1.7 (35.1) | 5.3 (41.5) | 9.3 (48.7) | 12.9 (55.2) | 14.7 (58.5) | 14.5 (58.1) | 10.4 (50.7) | 6.5 (43.7) | 2.1 (35.8) | −0.8 (30.6) | 6.1 (43.0) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −13.8 (7.2) | −12.4 (9.7) | −7.3 (18.9) | −3.3 (26.1) | 1.5 (34.7) | 5.3 (41.5) | 7.8 (46.0) | 6.6 (43.9) | 1.9 (35.4) | −2.1 (28.2) | −6.8 (19.8) | −12.3 (9.9) | −16.8 (1.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −22.2 (−8.0) | −25.4 (−13.7) | −16.0 (3.2) | −6.0 (21.2) | −2.3 (27.9) | 1.0 (33.8) | 6.5 (43.7) | 4.8 (40.6) | 0.6 (33.1) | −4.5 (23.9) | −11.0 (12.2) | −20.7 (−5.3) | −25.4 (−13.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 51.9 (2.04) | 45.5 (1.79) | 61.2 (2.41) | 56.0 (2.20) | 107.0 (4.21) | 120.9 (4.76) | 118.9 (4.68) | 116.5 (4.59) | 78.1 (3.07) | 66.9 (2.63) | 58.4 (2.30) | 58.5 (2.30) | 939.7 (37.00) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 15.3 | 14.0 | 15.6 | 13.5 | 16.1 | 16.7 | 16.1 | 15.0 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 14.6 | 16.8 | 182.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1.0 cm) | 11.7 | 11.2 | 4.5 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.3 | 8.0 | 39.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 80.3 | 75.9 | 70.7 | 64.6 | 67.2 | 67.2 | 66.1 | 68.1 | 75.5 | 79.9 | 83.3 | 82.3 | 73.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 74.6 | 95.2 | 145.3 | 186.0 | 213.0 | 223.7 | 241.4 | 232.1 | 169.7 | 123.3 | 74.0 | 66.4 | 1,841.4 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization[112] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: DWD[113] SKlima.de[114] Infoclimat[115] | |||||||||||||

Climate change[edit]

In Munich, the general trend of global warming with a rise of medium yearly temperatures of about 1 °C (1.8 °F) in Germany between 1900 and 2020 can be observed as well. In November 2016 the city council concluded officially that a further rise in medium temperature, a higher number of heat extremes, a rise in the number of hot days and nights with temperatures higher than 20 °C (tropical nights), a change in precipitation patterns, as well as a rise in the number of local instances of heavy rain, is to be expected as part of the ongoing climate change. The city administration decided to support a joint study from its own Referat für Gesundheit und Umwelt (department for health and environmental issues) and the German Meteorological Service that will gather data on local weather. The data is supposed to be used to create a plan for action for adapting the city to better deal with climate change as well as an integrated action program for climate protection in Munich. With the help of those programs issues regarding spatial planning and settlement density, the development of buildings and green spaces as well as plans for functioning ventilation in a cityscape can be monitored and managed.[116]

Demographics[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1500 | 13,447 | — |

| 1600 | 21,943 | +63.2% |

| 1750 | 32,000 | +45.8% |

| 1880 | 230,023 | +618.8% |

| 1890 | 349,024 | +51.7% |

| 1900 | 499,932 | +43.2% |

| 1910 | 596,467 | +19.3% |

| 1920 | 666,000 | +11.7% |

| 1930 | 728,900 | +9.4% |

| 1940 | 834,500 | +14.5% |

| 1950 | 823,892 | −1.3% |

| 1955 | 929,808 | +12.9% |

| 1960 | 1,055,457 | +13.5% |

| 1965 | 1,214,603 | +15.1% |

| 1970 | 1,311,978 | +8.0% |

| 1980 | 1,298,941 | −1.0% |

| 1990 | 1,229,026 | −5.4% |

| 2000 | 1,210,223 | −1.5% |

| 2005 | 1,259,584 | +4.1% |

| 2010 | 1,353,186 | +7.4% |

| 2011 | 1,364,920 | +0.9% |

| 2012 | 1,388,308 | +1.7% |

| 2013 | 1,402,455 | +1.0% |

| 2015 | 1,450,381 | +3.4% |

| 2018 | 1,471,508 | +1.5% |

| 2020 | 1,488,202 | +1.1% |

| 2022 | 1,512,491 | +1.6% |

| Population size may be affected by changes in administrative divisions. | ||

From only 24,000 inhabitants in 1700, the city population doubled about every 30 years. It was 100,000 in 1852, 250,000 in 1883 and 500,000 in 1901. Since then, Munich has become Germany's third-largest city. In 1933, 840,901 inhabitants were counted, and in 1957 over 1 million. Munich has reached 1.5 million in 2022.

Immigration[edit]

In July 2017, Munich had 1.42 million inhabitants; 421,832 foreign nationals resided in the city as of 31 December 2017 with 50.7% of these residents being citizens of EU member states, and 25.2% citizens in European states not in the EU (including Russia and Turkey).[117] Along with the Turks, the Croats are one of the two largest foreign minorities in the city, which is why some Croats refer to Munich as their "second capital."[118] The largest groups of foreign nationals were Turks (39,204), Croats (33,177), Italians (27,340), Greeks (27,117), Poles (27,945), Austrians (21,944), and Romanians (18,085).

| Country | Population |

|---|---|

| 39,745 | |

| 37,207 | |

| 28,496 | |

| 26,613 | |

| 21,559 | |

| 20,741 | |

| 18,845 | |

| 18,639 | |

| 17,833 | |

| 14,283 | |

| 13,636 | |

| 12,354 | |

| 11,228 | |

| 11,093 | |

| 10,650 | |

| 9,526 | |

| 9,414 | |

| 9,240 | |

| 8,769 | |

| 7,446 | |

| 6,705 | |

| 5,289 | |

| 4,614 | |

| 4,297 |

Religion[edit]

About 45% of Munich's residents are not affiliated with any religious group; this ratio represents the fastest growing segment of the population. As in the rest of Germany, the Catholic and Protestant churches have experienced a continuous decline in membership. As of 31 December 2017, 31.8% of the city's inhabitants were Catholic, 11.4% Protestant, 0.3% Jewish (see: History of the Jews in Munich),[120] and 3.6% were members of an Orthodox Church (Eastern Orthodox or Oriental Orthodox).[121] About 1% adhere to other Christian denominations. There is also a small Old Catholic parish and an English-speaking parish of the Episcopal Church in the city. According to Munich Statistical Office, in 2013 about 8.6% of Munich's population was Muslim.[122]Munich has the largest Uyghur population with about 800 (whole Germany about 1,600) people with Uyghur diaspora. Many of them fled to Munich due to the Chinese government and are exiled in Munich. Munich is also home to World Uyghur Congress, which is an international organisation of exiled Uyghurs.[123]

Government and politics[edit]

As the capital of Bavaria, Munich is an important political centre for both the state and country as a whole. It is the seat of the Landtag of Bavaria, the State Chancellery, and all state departments. Several national and international authorities are located in Munich, including the Federal Finance Court of Germany, the German Patent Office and the European Patent Office.

Mayor[edit]

The current mayor of Munich is Dieter Reiter, he is Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). He was elected in 2014 and re-elected in 2020. Bavaria has been dominated by the Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU) on a federal, state, and local level since the establishment of the Federal Republic in 1949. The Munich city council is called the Stadtrat.

The most recent mayoral election was held on 15 March 2020, with a runoff held on 29 March, and the results were as follows:

| Candidate | Party | First round | Second round | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Dieter Reiter | Social Democratic Party | 259,928 | 47.9 | 401,856 | 71.7 | |

| Kristina Frank | Christian Social Union | 115,795 | 21.3 | 158,773 | 28.3 | |

| Katrin Habenschaden | Alliance 90/The Greens | 112,121 | 20.7 | |||

| Wolfgang Wiehle | Alternative for Germany | 14,988 | 2.8 | |||

| Tobias Ruff | Ecological Democratic Party | 8,464 | 1.6 | |||

| Jörg Hoffmann | Free Democratic Party | 8,201 | 1.5 | |||

| Thomas Lechner | The Left | 7,232 | 1.3 | |||

| Hans-Peter Mehling | Free Voters of Bavaria | 5,003 | 0.9 | |||

| Moritz Weixler | Die PARTEI | 3,508 | 0.6 | |||

| Dirk Höpner | Munich List | 1,966 | 0.4 | |||

| Richard Progl | Bavaria Party | 1,958 | 0.4 | |||

| Ender Beyhan-Bilgin | FAIR | 1,483 | 0.3 | |||

| Stephanie Dilba | mut | 1,267 | 0.2 | |||

| Cetin Oraner | Together Bavaria | 819 | 0.2 | |||

| Valid votes | 542,733 | 99.6 | 560,629 | 99.7 | ||

| Invalid votes | 1,997 | 0.4 | 1,616 | 0.3 | ||

| Total | 544,730 | 100.0 | 562,245 | 100.0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 1,110,571 | 49.0 | 1,109,032 | 50.7 | ||

| Source: Wahlen München (1st round, 2nd round) | ||||||

City council[edit]

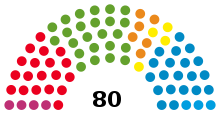

Left/PARTEI: 4 seats

SPD/Volt: 19 seats

Greens/Pink List: 24 seats

ÖDP/FW: 6 seats

FDP/BP: 4 seats

CSU: 20 seats

AfD: 3 seats

The Munich city council (Stadtrat) governs the city alongside the Mayor. The most recent city council election was held on 15 March 2020, and the results were as follows:

| Party | Lead candidate | Votes | % | +/- | Seats | +/- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alliance 90/The Greens (Grüne) | Katrin Habenschaden | 11,762,516 | 29.1 | 23 | |||

| Christian Social Union (CSU) | Kristina Frank | 9,986,014 | 24.7 | 20 | |||

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | Dieter Reiter | 8,884,562 | 22.0 | 18 | |||

| Ecological Democratic Party (ÖDP) | Tobias Ruff | 1,598,539 | 4.0 | 3 | |||

| Alternative for Germany (AfD) | Iris Wassill | 1,559,476 | 3.9 | 3 | |||

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | Jörg Hoffmann | 1,420,194 | 3.5 | 3 | ±0 | ||

| The Left (Die Linke) | Stefan Jagel | 1,319,464 | 3.3 | 3 | |||

| Free Voters of Bavaria (FW) | Hans-Peter Mehling | 1,008,400 | 2.5 | 2 | ±0 | ||

| Volt Germany (Volt) | Felix Sproll | 732,853 | 1.8 | New | 1 | New | |

| Die PARTEI (PARTEI) | Marie Burneleit | 528,949 | 1.3 | New | 1 | New | |

| Pink List (Rosa Liste)[a] | Thomas Niederbühl | 396,324 | 1.0 | 1 | ±0 | ||

| Munich List | Dirk Höpner | 339,705 | 0.8 | New | 1 | New | |

| Bavaria Party (BP) | Richard Progl | 273,737 | 0.7 | 1 | ±0 | ||

| mut | Stephanie Dilba | 247,679 | 0.6 | New | 0 | New | |

| FAIR | Kemal Orak | 142,455 | 0.4 | New | 0 | New | |

| Together Bavaria (ZuBa) | Cetin Oraner | 120,975 | 0.3 | New | 0 | New | |

| BIA | Karl Richter | 86,358 | 0.2 | 0 | ±0 | ||

| Valid votes | 531,527 | 97.6 | |||||

| Invalid votes | 12,937 | 2.4 | |||||

| Total | 544,464 | 100.0 | 80 | ±0 | |||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 1,110,571 | 49.0 | |||||

| Source: Wahlen München Archived 21 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine | |||||||

State Landtag[edit]

In the Landtag of Bavaria, Munich is divided between nine constituencies. After the 2018 Bavarian state election, the composition and representation of each was as follows:

| Constituency | Area | Party | Member | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101 München-Hadern |

| CSU | Georg Eisenreich | |

| 102 München-Bogenhausen |

| CSU | Robert Brannekämper | |

| 103 München-Giesing |

| GRÜNE | Gülseren Demirel | |

| 104 München-Milbertshofen |

| GRÜNE | Katharina Schulze | |

| 105 München-Moosach |

| GRÜNE | Benjamin Adjei | |

| 106 München-Pasing |

| CSU | Josef Schmid | |

| 107 München-Ramersdorf |

| CSU | Markus Blume | |

| 108 München-Schwabing |

| GRÜNE | Christian Hierneis | |

| 109 München-Mitte |

| GRÜNE | Ludwig Hartmann | |

Federal parliament[edit]

In the Bundestag, Munich is divided between four constituencies. In the 20th Bundestag, the composition and representation of each was as follows:

| Constituency | Area | Party | Member | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 217 Munich North |

| CSU | Bernhard Loos | |

| 218 Munich East |

| CSU | Wolfgang Stefinger | |

| 219 Munich South |

| GRÜNE | Jamila Schäfer | |

| 220 Munich West/Centre |

| CSU | Stephan Pilsinger | |

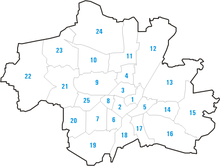

Subdivisions[edit]

Since the reform of 1992, Munich is divided into 25 administrative boroughs (Stadtbezirke). They are subdivided into 105 statistical areas.

Allach-Untermenzing (23), Altstadt-Lehel (1), Aubing-Lochhausen-Langwied (22), Au-Haidhausen (5), Berg am Laim (14), Bogenhausen (13), Feldmoching-Hasenbergl (24), Hadern (20), Laim (25), Ludwigsvorstadt-Isarvorstadt (2), Maxvorstadt (3), Milbertshofen-Am Hart (11), Moosach (10), Neuhausen-Nymphenburg (9), Obergiesing (17), Pasing-Obermenzing (21), Ramersdorf-Perlach (16), Schwabing-Freimann (12), Schwabing-West (4), Schwanthalerhöhe (8), Sendling (6), Sendling-Westpark (7), Thalkirchen-Obersendling-Forstenried-Fürstenried-Solln (19), Trudering-Riem (15), and Untergiesing-Harlaching (18).

There is no official division into districts. The number of districts is about 50, and if smaller units are counted as well, there are about 90 to 100 (see map). The three largest districts are Schwabing in the north (about 110,000 inhabitants), Sendling in the southwest (about 100,000 inhabitants), and Giesing in the south (about 80,000 inhabitants).[124]

Architecture[edit]

Old Town[edit]

At the centre of the old town is the Marienplatz with the Old Town Hall and the New Town Hall. Its tower contains the Rathaus-Glockenspiel. The Peterskirche is the oldest church of the inner city. Nearby St. Peter, the Gothic hall-church Heiliggeistkirche was converted to baroque style from 1724 onwards and looks down upon the Viktualienmarkt. Three gates of the demolished medieval fortification survive; these are the Isartor, the Sendlinger Tor, and the Karlstor. The Karlstor leads up to the Stachus, a square dominated by the Justizpalast (Palace of Justice).

The Frauenkirche serves as the cathedral for the Catholic Archdiocese of Munich and Freising. The nearby Michaelskirche is the largest renaissance church north of the Alps, while the Theatinerkirche is a basilica in Italianate high baroque, which had a major influence on southern German baroque architecture. Its dome dominates the Odeonsplatz.

Palaces and castles[edit]

Schloss Nymphenburg (Nymphenburg Palace, construction started 1664) is a museum open to the public for tours.[125][126]

The smaller Schloss Fürstenried (Fürstenried Palace, construction 1715–1717) is used by the Archdiocese of Munich and Freising as a conference location.[127]

Schloss Blutenburg (Blutenburg Castle) opened as a children's library in 2024,[128] but visitors may tour the late-Gothic Blutenburg Castle Church built on the same grounds.[129]

The large Munich Residenz complex on the edge of Munich's Old Town now ranks among Europe's most significant museums of interior decoration. Within the Residenz is the splendid Cuvilliés Theatre and next door is the National Theatre Munich. Among the mansions that still exist in Munich are the Palais Porcia, the Palais Preysing, the Palais Holnstein and the Prinz-Carl-Palais. All mansions are situated close to the Residenz, so is the Alter Hof, the first residence of the House of Wittelsbach.

Modernist architecture[edit]

Despite Munich being the breeding ground for German Jugendstil, starting with the architect Martin Dülfer, Munich Jugendstil style was quickly submerged as historic trash. While the modernist architect Theodor Fischer was based in Munich, his influence on Munich underwhelmed. Prior to 1914 the city of Munich was under-industrialized. During the Weimar Republic, the Munich establishment was hostile to modernism. The TUM professor German Bestelmeyer favored a conservative style, and Jacobus Oud was rejected for the post of city building chief. Modernist exceptions include a series of post offices by Robert Vorhoelzer built in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Examples of avant-garde temporary constructions include the Wohnmaschine (Housing Machine) by Robert Vorhoelzer, as well as the Flachdachhaus (Flat Roof House) by Fritz Norkauer. Paul Schultze-Naumburg, and the Kampfbund enjoyed particular popularity.[130]

High rise buildings[edit]

Several high-rise buildings are clustered at the northern edge of Munich in the skyline, like the HVB Tower, the Arabella High-Rise Building, the Highlight Towers, Uptown Munich, Münchner Tor and the BMW Headquarters next to the Olympic Park. Further high-rise buildings are located in the Werksviertel in Berg am Laim.

Long-term residential development[edit]

Munich is subject to a long-term residential development plan that is established by the city administration of Munich. The LaSie ("Langfristige Siedlungsentwicklung") was passed in 2011 in response to the acute housing crisis. LaSie is aligned with the strategic development plan passed for Munich in 1998 ("Perspektive München"). LaSie defines three priorities for the construction of residential housing in Munich. Existing housing estates, post-war low-density developments, and the suburban area are subject to densification ("Nachverdichtung"). Non-residential industrial areas are subject to conservation and will be turned into residential and mixed-use areas. On greenfield sites in the Munich periphery medium and large-scale housing estates are to be built so as to extend Munich's urban center.[131]

Parks[edit]

Friedrich Ludwig von Sckell became famous for designing the Englischer Garten between 1789 and 1807. Besides planning the first public garden in Europe, Sckell also redesigned Baroque gardens as landscape gardens, including the parks of Nymphenburg Palace and the Botanischer Garten München-Nymphenburg.[132]

Other large green spaces are the Olympiapark, the Westpark and the Ostpark. The city's oldest park is the Hofgarten, near the Residenz, dating back to the 16th century. The site of the largest beer garden in town, the former royal Hirschgarten, was founded in 1780.[citation needed]

Sports[edit]

Football[edit]

Munich is home to several professional Association football teams including the FC Bayern Munich. Other notable clubs include 1860 Munich, who currently play in the 3. Liga, and former Bundesliga club SpVgg Unterhaching, who currently play in the 3. Liga. Munich hosted matches in the 2006 FIFA World Cup.

Basketball[edit]

FC Bayern Munich Basketball is currently playing in the Beko Basket Bundesliga. The city hosted the final stages of the FIBA EuroBasket 1993, where the German national basketball team won the gold medal.

Ice hockey[edit]

The city's ice hockey club is EHC Red Bull München who play in the Deutsche Eishockey Liga. The team has won four DEL Championships, in 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2023.

Olympics[edit]

Munich hosted the 1972 Summer Olympics; the Munich massacre took place in the Olympic village. It was one of the host cities for the 2006 Football World Cup, which was not held in Munich's Olympic Stadium, but in a new football specific stadium, the Allianz Arena. Munich bid to host the 2018 Winter Olympic Games, but lost to Pyeongchang.[133] In September 2011 the DOSB President Thomas Bach confirmed that Munich would bid again for the Winter Olympics in the future.[134] These plans were abandoned some time later.

Road running[edit]

Regular annual road running events in Munich are the Munich Marathon in October, the Stadtlauf end of June, the company run B2Run in July, the New Year's Run on 31 December, the Spartan Race Sprint, the Olympia Alm Crosslauf and the Bestzeitenmarathon.

Swimming[edit]

Public sporting facilities in Munich include ten indoor swimming pools[135] and eight outdoor swimming pools,[136] which are operated by the Munich City Utilities (SWM) communal company.[137] Popular indoor swimming pools include the Olympia Schwimmhalle of the 1972 Summer Olympics, the wave pool Cosimawellenbad, as well as the Müllersches Volksbad which was built in 1901. Further, swimming within Munich's city limits is also possible in several artificial lakes such as for example the Riemer See or the Langwieder lake district.[138]

River surfing[edit]

River surfing is a popular sport in Munich. The Flosskanal wave in the south of Munich is less challenging. A well visited surfing spot for experienced surfers is the Eisbach standing wave, where the annual Munich Surf Open is celebrated on the last Saturday of July.[139]

Culture[edit]

Language[edit]

German is spoken and understood in and around Munich. While the German language has many dialects, so-called "Standard German" or "High German" is learned in schools and spoken among Germans, Austrians and in some parts of Switzerland. A speaker of a Low German dialect in Hamburg may find it difficult to understand the dialect of a Bavarian mountaineer.[140] The Bavarian dialects are recognized as regional language and continues to be spoken alongside Standard German.[141]

Museums[edit]

The gothic Morris dancers of Erasmus Grasser are exhibited in the Munich City Museum in the old gothic arsenal building in the inner city.

In 1903 Oskar von Miller assembled a group of engineers and industrialists, who chartered the Deutsches Museum. The Museum was built with the financial support of the German business and imperial nobility community, as well as the blessing of Wilhelm II, German Emperor.[142] The Deutsches Museum had its grand opening in 1925, but has undergone a reinvention recently. The Deutsches Museum now operates three locations. The original site in central Munich continues to expand its exhibits.[143]

The city has several important art galleries, most of which can be found in the Kunstareal. The Lenbachhaus displays works of the movement Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), a Munich-based modernist art.[citation needed]Starting in 1970s, German municipalities started to respond to cultural tourism and invested in public museums. The Neue Pinakothek, like other German museums, was wholly reconstructed from 1974 until 1981.[144] The Pinakothek der Moderne lets the public see an eclectic mix of contemporary art and the principle attention of the permanent collection is Classical Moderns. But the displays are enhanced continuously with spectacular gifts from private collections.[145]

City guides published in the early 1860s directed tourists to Munich's architecture and art collections, which at the time were unique in Germany and are a legacy mainly of Ludwig I of Bavaria, with contributions from Maximilian II of Bavaria.[146] The Alte Pinakothek contains works of European masters between the 14th and 18th centuries. Major displays include Albrecht Dürer's Self-Portrait (1500), his Four Apostles, Raphael's paintings The Canigiani Holy Family and Madonna Tempi as well as Peter Paul Rubens large Judgment Day.

An extensive collection of Greek and Roman art is held in the Glyptothek[147] and the Staatliche Antikensammlungen (the State Antiquities Collections). Works on display include the Medusa Rondanini, the Barberini Faun and figures from the Temple of Aphaea on Aegina for the Glyptothek.[148] Another interesting museum is the Staatliche Sammlung für Ägyptische Kunst (the State Collection of Egyptian Art).[149][150][151]

Several public collections of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich are still housed in the Kunstareal. The expanded state collections are housed in the Paläontologisches Museum München, and the Zoologische Staatssammlung München.[citation needed] After the first German art exhibition in the Glaspalast for an international audience in 1869, Munich emerged as a focal point for the arts. Men of distinction from around the world visited the Academy of Fine Arts under the directorship of Karl von Piloty and later Wilhelm von Kaulbach.[152]

The Museum Five Continents is the second largest collection in Germany of artefacts and objects from outside Europe, while the Bavarian National Museum and the adjoining Bavarian State Archaeological Collection display regional art and cultural history. The Schackgalerie is an important gallery of German 19th-century paintings.[citation needed]

The memorial museum of the former Dachau concentration camp is just outside the city.

Music[edit]

Munich is a major international musical centre and has played host to many prominent composers including Orlande de Lassus, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Carl Maria von Weber, Richard Wagner, Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Max Reger and Carl Orff. Some of classical music's best-known compositions have been created in and around Munich by composers born in the area, for example, Richard Strauss's tone poem Also sprach Zarathustra or Carl Orff's Carmina Burana.[citation needed][153]

Opera[edit]

Richard Wagner was a supporter of William I, German Emperor, but Wagner only found a generous patron in Ludwig II of Bavaria.[154] 1870 til 1871 Wagner premiered Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Mastersingers of Nuremberg) in Munich, a popular success for Wagner and King Ludwig II. Wagner premiered at the Hoftheater, now the National Theatre Munich, with Angelo Quaglio the Younger designing the premiere production.[155]

The National Theatre Munich is now the home of the Bavarian State Opera and the Bavarian State Orchestra. Next door, the modern Residenz Theatre was erected in the building that also houses the Cuvilliés Theatre. The Staatstheater am Gärtnerplatz is a state theater while another opera house, the Prinzregententheater, has become the home of the Bavarian Theater Academy and the Munich Chamber Orchestra.

Orchestra[edit]

The modern Gasteig centre houses the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra. The third orchestra in Munich with international importance is the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. Its primary concert venue is the Herkulessaal in the former city royal residence, the Munich Residenz. Many important conductors have been attracted by the city's orchestras, including Felix Weingartner, Hans Pfitzner, Hans Rosbaud, Hans Knappertsbusch, Sergiu Celibidache, James Levine, Christian Thielemann, Lorin Maazel, Rafael Kubelík, Eugen Jochum, Sir Colin Davis, Mariss Jansons, Bruno Walter, Georg Solti, Zubin Mehta and Kent Nagano. A stage for shows, big events and musicals is the Deutsche Theater. It is Germany's largest theatre for guest performances.[156]

Pop and electronica[edit]

Munich was the centre of Krautrock in southern Germany, with many important bands such as Amon Düül II, Embryo or Popol Vuh hailing from the city. In the 1970s, the Musicland Studios developed into one of the most prominent recording studios in the world, with bands such as the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple and Queen recording albums there. Munich also played a significant role in the development of electronic music, with genre pioneer Giorgio Moroder, who invented synth disco and electronic dance music, and Donna Summer, one of disco music's most important performers, both living and working in the city. In the late 1990s, Electroclash was substantially co-invented if not even invented in Munich, when DJ Hell introduced and assembled international pioneers of this musical genre through his International DeeJay Gigolo Records label here.[157]

Other notable musicians and bands from Munich include Konstantin Wecker, Willy Astor, Spider Murphy Gang, Münchener Freiheit, Lou Bega, Megaherz, FSK, Colour Haze and Sportfreunde Stiller.[citation needed]

Munich hosted several Love Parades and Mayday Party rave events throughout the 1990s. Munich continues to rave, the local youth scenes are active.[158]

Theatre[edit]

The Munich Kammerspiele is one of the most important German-language theaters. Since Gotthold Ephraim Lessing's premieres in 1775 many important writers have staged their plays in Munich, they include Christian Friedrich Hebbel, Henrik Ibsen, and Hugo von Hofmannsthal.[citation needed]

Schwabing[edit]

At the turn of the 20th century Schwabing was a preeminent cultural metropolis. Schwabing was an epicenter for both literature and the fine arts, with numerous German and non-German artists living there.[159]

Vladimir Lenin authored What Is to Be Done? while living in Schwabing. Central to Schwabing's bohemian scene were Künstlerlokale (Artist's Cafés) like Café Stefanie or Kabarett Simpl, whose liberal ways differed fundamentally from Munich's more traditional localities. The Simpl, which survives to this day, was named after Munich's anti-authoritarian satirical magazine Simplicissimus, founded in 1896 by Albert Langen and Thomas Theodor Heine, which quickly became an important organ of the Schwabinger Bohème. Its caricatures and biting satirical attacks on Wilhelmine German society were the result of countless of collaborative efforts by many of the best visual artists and writers from Munich and elsewhere.[citation needed]

In 1971 Eckart Witzigmann teamed up with a Munich building contractor to finance and open the Tantris restaurant in Schwabing. Witzigmann is credited for starting the German Küchenwunder (kitchen wonder).[160]

Biedermeier[edit]

The Biedermeier era was named after a character that regularly appeared in the satire magazine Münchner Fliegende Blätter (Loose Munich Pages), which was published by Adolf Kussmaul and Ludwig Eichrodt in Munich between 1855 and 1857. Biedermeier was a synonym for arts, furniture, and the lifestyle of the nonheroic middle class. The Biedermeier era painters Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, Moritz von Schwind, and Carl Spitzweg are shown in the Neue Pinakothek.[161]

Prinzregentenzeit[edit]

Celebrity literary figures worked in Munich especially during the final decades of the Kingdom of Bavaria, the so-called Prinzregentenzeit (literally prince regent's time) under the reign of Luitpold, Prince Regent of Bavaria. This includes Thomas Mann, Heinrich Mann, Paul Johann Ludwig von Heyse, Rainer Maria Rilke, Ludwig Thoma, Fanny zu Reventlow, Oskar Panizza, Gustav Meyrink, Max Halbe, Erich Mühsam and Frank Wedekind.

Weimar Republic[edit]

The period immediately before World War I saw continued economic and cultural prominence for the city. Thomas Mann wrote in his novella Gladius Dei about this period: "München leuchtete" (literally "Munich shone"). Munich remained a centre of cultural life during the Weimar Republic, with figures such as Lion Feuchtwanger, Bertolt Brecht, Peter Paul Althaus, Stefan George, Ricarda Huch, Joachim Ringelnatz, Oskar Maria Graf, Annette Kolb, Ernst Toller, Hugo Ball, and Klaus Mann adding to the already established big names.[citation needed]

Karl Valentin, the cabaret performer and comedian, is to this day remembered and beloved as a cultural icon of his hometown. Between 1910 and 1940, he wrote and performed in many absurdist sketches and short films that were highly influential, earning him the nickname of "Charlie Chaplin of Germany".[162][163]

Liesl Karlstadt, before working together with Valentin, cross-dressed and performed cabaret with yodeling on stage and in Munich's Cafe-Theatres. The cabaret scene was crushed when the Nazis seized power in 1933 and Karlstadt was saved from Nazi sterilization by a doctor. Contemporary Munich cabaret still reverences 1920s cabaret, the Munich alternative rock band F.S.K. absorbs yodels.[164]

Post-war literature[edit]

After World War II, Munich soon again became a focal point of the German literary scene and remains so to this day, with writers as diverse as Wolfgang Koeppen, Erich Kästner, Eugen Roth, Alfred Andersch, Elfriede Jelinek, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Michael Ende, Franz Xaver Kroetz, Gerhard Polt and Patrick Süskind calling the city their home.[citation needed]

Fine arts[edit]

From the Gothic to the Baroque era, the fine arts were represented in Munich by artists like Erasmus Grasser, Jan Polack, Johann Baptist Straub, Ignaz Günther, Hans Krumpper, Ludwig von Schwanthaler, Cosmas Damian Asam, Egid Quirin Asam, Johann Baptist Zimmermann, Johann Michael Fischer and François de Cuvilliés. Munich had already become an important place for painters like Carl Rottmann, Lovis Corinth, Wilhelm von Kaulbach, Carl Spitzweg, Franz von Lenbach, Franz Stuck, Karl Piloty and Wilhelm Leibl.[citation needed]

Cinema[edit]

Munich was (and in some cases, still is) home to many of the most important authors of the New German Cinema movement, including Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Werner Herzog, Edgar Reitz and Herbert Achternbusch. In 1971, the Filmverlag der Autoren was founded, cementing the city's role in the movement's history. Munich served as the location for many of Fassbinder's films, among them Ali: Fear Eats the Soul. The Hotel Deutsche Eiche near Gärtnerplatz was somewhat like a centre of operations for Fassbinder and his "clan" of actors. New German Cinema is considered by far the most important artistic movement in German cinema history since the era of German Expressionism in the 1920s.[165][166]

In 1919, the Bavaria Film Studios were founded, which developed into one of Europe's largest film studios. Directors like Alfred Hitchcock, Billy Wilder, Orson Welles, John Huston, Ingmar Bergman, Stanley Kubrick, Claude Chabrol, Fritz Umgelter, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Wolfgang Petersen and Wim Wenders made films there. Among the internationally well-known films produced at the studios are The Pleasure Garden (1925) by Alfred Hitchcock, The Great Escape (1963) by John Sturges, Paths of Glory (1957) by Stanley Kubrick, Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971) by Mel Stuart and both Das Boot (1981) and The Neverending Story (1984) by Wolfgang Petersen. Munich remains one of the centres of the German film and entertainment industry.[167]

Festivals[edit]

Coopers' Dance[edit]

The Coopers' Dance (German: Schäfflertanz) is a guild dance of coopers originally started in Munich. Since early 1800s the custom spread via journeymen in it is now a common tradition over the Old Bavaria region. The dance was supposed to be held every seven years.[168]

Starkbierfest[edit]

March and April, for three weeks during Lent, celebrating Munich's "strong beer". Starkbier was created in 1651 by the local Paulinerkirche, Leipzig monks who drank this 'Flüssiges Brot', or 'liquid bread'. It became a public festival in 1751 and is now the second largest beer festival in Munich. A Starkbierfest may be celebrated in beer halls and pubs.[citation needed]

Frühlingsfest[edit]

Held for two weeks at the Theresienwiese from the end of April to the beginning of May, the new local spring beers are served.[169]

Auer Dult[edit]

A regular event combining a market and a German style folk festival on the Mariahilfplatz. The Auer Dult can be up to 300 stalls, selling handmade crafts, household goods, and local foods.[170]

Kocherlball[edit]

Munich's Kocherlball (Cooks' Ball) is an annual event, to commemorate all servants, ranging from kitchenhands to cooks. The tradition started in the 19th century.[171]

Tollwood[edit]

Usually held annually in July and December, Olympia Park. The Tollwood Festival showcases fine and performing arts with live music, and several lanes of booths selling handmade crafts, as well as Organic food, mostly Fusion cuisine.[citation needed]

Oktoberfest[edit]

At the Theresienwiese, the largest beer festival in the world, Munich's Oktoberfest runs for 16–18 days from the end of September through early October. In the last 200 years the festival has grown to span 85 acres and now welcomes over six million visitors every year. Beer is served from the six major Munich breweries. These are Augustiner-Bräu, Hacker-Pschorr Brewery, Löwenbräu Brewery, Paulaner Brewery, Spaten-Franziskaner-Bräu, and Staatliches Hofbräuhaus in München. Food must be bought in each tent.[172]

Christkindlmarkt[edit]

The Munich Christkindlmarkt started to evolve in the 14th century. The German Christkindlmarkt reached the desired accomplishment in the 17th century in Nuremberg.[173]

Cuisine and culinary specialities[edit]

The Munich cuisine contributes to the Bavarian cuisine. Munich Weisswurst ("white sausage", German: Münchner Weißwurst) was invented here in 1857. It is a Munich speciality. Traditionally Weisswurst is served in pubs before noon and is served with sweet mustard and freshly baked pretzels.

Munich has 11 restaurants that have been awarded one or more Michelin Guide stars in 2021.[174]

Beers and breweries[edit]

Munich is known for its breweries and Weissbier (wheat beer). Helles, a pale lager with a translucent gold color, is the most popular contemporary Munich beer. Helles has largely replaced Munich's dark beer, known as Dunkel, which gets its color from roasted malt. It was the typical beer in Munich in the 19th century. Starkbier is the strongest Munich beer, with a high alcohol content of 6%–9%. It is dark amber in color and has a heavy malty taste. The beer served at Oktoberfest is a special type of beer with a higher alcohol content.

Wirtshäuser are traditional Bavarian pubs, many of which also have small outside areas. Biergärten (beer gardens) are a popular fixture in Munich's gastronomic landscape. They are central to the city's culture, and are an overt melting pot for members of all walks of life, regardless of social class. There are many smaller beer gardens, but some beer gardens have thousands of seats. Large beer gardens can be found in the Englischer Garten, on the Nockherberg, and in the Hirschgarten.

There are six main breweries in Munich are Augustiner-Bräu, Hacker-Pschorr Brewery, Hofbräuhaus, Löwenbräu, Paulaner, and Spaten-Franziskaner-Bräu. Smaller breweries are becoming more prevalent in Munich.

Circus[edit]

The Circus Krone based in Munich is one of the largest circuses in Europe.[175] It was the first and still is one of only a few in Western Europe to also occupy a building of its own.

Nightlife[edit]

Nightlife in Munich is located mostly in the boroughs Ludwigsvorstadt-Isarvorstadt, Maxvorstadt, Au-Haidhausen, Berg am Laim and Sendling. Between Sendlinger Tor and Maximiliansplatz, on the edge of the central Altstadt-Lehel district, there is also the so-called Feierbanane (party banana), a roughly banana-shaped unofficial party zone spanning 1.3 km (0.8 mi) along Sonnenstraße, characterized by a high concentration of clubs, bars and restaurants, which became the center of Munich's nightlife in the mid-2000s.[176]

In the 1960s and 1970s, Schwabing was considered a center of nightlife in Germany, with internationally known clubs such as Big Apple, PN hit-house, Domicile, Hot Club, Piper Club, Tiffany, Germany's first large-scale discotheque Blow Up and the underwater nightclub Yellow Submarine,[157][177][178] and Munich has been called "New York's big disco sister" in this context.[157][179] Bars in the Schwabing district of this era include, among many others, Schwabinger 7 and Schwabinger Podium. Since the 1980s, however, Schwabing has lost much of its nightlife activity due to gentrification and the resulting high rents, and the formerly wild artists' and students' quarter developed into one of the city's most coveted and expensive residential districts, attracting affluent citizens with little interest in partying.[180]

Since the 1960s, the Rosa Viertel (pink quarter) developed in the Glockenbachviertel and around Gärtnerplatz, which in the 1980s made Munich "one of the four gayest metropolises in the world" along with San Francisco, New York City and Amsterdam.[181] In particular, the area around Müllerstraße and Hans-Sachs-Straße was characterized by numerous gay bars and nightclubs. One of them was the travesty nightclub Old Mrs. Henderson, where Freddie Mercury, who lived in Munich from 1979 to 1985, filmed the music video for the song Living on My Own at his 39th birthday party.[181][178][182]

Since the mid-1990s, the Kunstpark Ost and its successor Kultfabrik, a former industrial complex that was converted to a large party area near München Ostbahnhof in Berg am Laim, hosted more than 30 clubs and was especially popular among younger people from the metropolitan area surrounding Munich and tourists.[181][183] The Kultfabrik was closed at the end of the year 2015 to convert the area into a residential and office area. Apart from the Kultfarbik and the smaller Optimolwerke, there is a wide variety of establishments in the urban parts of nearby Haidhausen. Before the Kunstpark Ost, there had already been an accumulation of internationally known nightclubs in the remains of the abandoned former Munich-Riem Airport.[157][184][185]

Munich nightlife tends to change dramatically and quickly. Establishments open and close every year, and due to gentrification and the overheated housing market many survive only a few years, while others last longer. Beyond the already mentioned venues of the 1960s and 1970s, nightclubs with international recognition in recent history included Tanzlokal Größenwahn, The Atomic Café and the techno clubs Babalu Club, Ultraschall, KW – Das Heizkraftwerk, Natraj Temple, MMA Club (Mixed Munich Arts), Die Registratur and Bob Beaman.[186] From 1995 to 2001, Munich was also home to the Union Move, one of the largest technoparades in Germany.[177]

Munich has the highest density of music venues of any German city, followed by Hamburg, Cologne and Berlin.[187][188] Within the city's limits are more than 100 nightclubs and thousands of bars and restaurants.[189][190]

Some notable nightclubs are: popular techno clubs are Blitz Club, Harry Klein, Rote Sonne, Bahnwärter Thiel, Pimpernel, Charlie, Palais and Pathos.[191][192] Popular mixed music clubs are Call me Drella, Wannda Circus, Tonhalle, Backstage, Muffathalle, Ampere, Pacha, P1, Zenith, Minna Thiel and the party ship Alte Utting.

Education[edit]

Colleges and universities[edit]

Munich is a leading location for science and research with a long list of Nobel Prize laureates from Wilhelm Röntgen in 1901 to Theodor W. Hänsch in 2005.

The Ludwig Maximilian University (LMU) and the Technische Universität München (TUM), were two of the first three German universities to be awarded the title elite university by a selection committee composed of academics and members of the Ministries of Education and Research of the Federation and the German states (Länder).

- Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (LMU), founded in 1472 in Ingolstadt, moved to Munich in 1826

- Technical University of Munich (TUM), founded in 1868

- Akademie der Bildenden Künste München, founded in 1808

- Bundeswehr University Munich, founded in 1973 (located in Neubiberg)

- Deutsche Journalistenschule, founded in 1959

- Bayerische Akademie für Außenwirtschaft, founded in 1989

- Hochschule für Musik und Theater München, founded in 1830

- International Max Planck Research School for Molecular and Cellular Life Sciences, founded in 2005

- International School of Management, Germany, founded in 1990

- Katholische Stiftungsfachhochschule München, founded in 1971

- Munich Business School (MBS), founded in 1991

- Munich Intellectual Property Law Center (MIPLC), founded in 2003

- Munich School of Philosophy, founded in 1925 in Pullach, moved to Munich in 1971

- Munich School of Political Science, founded in 1950

- Munich University of Applied Sciences (HM), founded in 1971

- New European College, founded in 2014

- Ukrainian Free University, founded in 1921 (from 1945 – in Munich)

- University of Television and Film Munich (Hochschule für Fernsehen und Film), founded in 1966

Primary and secondary schools[edit]

Notable Gymnasien in Munich include the Maria-Theresia-Gymnasium, the Luitpold Gymnasium, the Wilhelmsgymnasium, as well as the Wittelsbacher Gymnasium. Munich has several notable international schools, including Lycée Jean Renoir, the Japanische Internationale Schule München, the Bavarian International School, the Munich International School, and the European School, Munich.[citation needed]

Scientific research institutions[edit]

Max Planck Society[edit]

The Max Planck Society, a government funded non-profit research organization, has its administrative headquarters in Munich.

Fraunhofer Society[edit]

The Fraunhofer Society, the German government funded research organization for applied research, has its headquarters in Munich.

Other research institutes[edit]

- Botanische Staatssammlung München, a notable herbarium

- Ifo Institute for Economic Research, theoretical and applied research in economics and finance

- Doerner Institute

- European Southern Observatory

- Helmholtz Zentrum München

- Zoologische Staatssammlung München

- German Aerospace Center (GSOC), Oberpfaffenhofen bei München

International relations[edit]

Twin towns and sister cities[edit]

Economy[edit]

Munich has the strongest economy of any German city according to a study[194] and the lowest unemployment rate (5.4% in July 2020) of any German city of more than a million people (the others being Berlin, Hamburg and Cologne).[195][196] Munich ranks third on the list of German cities by gross domestic product (GDP). In addition, it is one of the most attractive business locations in Germany.[194] The city is also the economic centre of southern Germany. Munich topped the ranking of the magazine Capital in February 2005 for the economic prospects between 2002 and 2011 in 60 German cities.

Munich is a financial center and global city that holds the headquarters of many companies. This includes more companies listed by the DAX than any other German city, as well as the German or European headquarters of many foreign companies such as McDonald's and Microsoft. One of the best-known newly established Munich companies is Flixbus.

Manufacturing[edit]

Munich holds the headquarters of Siemens AG (electronics), BMW (car), MAN AG (truck manufacturer, engineering), MTU Aero Engines (aircraft engine manufacturer), Linde (gases) and Rohde & Schwarz (electronics). Among German cities with more than 500,000 inhabitants, purchasing power is highest in Munich (€26,648 per inhabitant) as of 2007[update].[197] In 2006, Munich blue-collar workers enjoyed an average hourly wage of €18.62 (ca. $20).[198]

The breakdown by cities proper (not metropolitan areas) of Global 500 cities listed Munich in 8th position in 2009.[199] Munich is also a centre for biotechnology, software and other service industries. Furthermore, Munich is the home of the headquarters of many other large companies such as the injection moulding machine manufacturer Krauss-Maffei, the camera and lighting manufacturer Arri, the semiconductor firm Infineon Technologies (headquartered in the suburban town of Neubiberg), lighting giant Osram, as well as the German or European headquarters of many foreign companies such as Microsoft.

Finance[edit]

Munich has significance as a financial centre (second only to Frankfurt), being home of HypoVereinsbank and the Bayerische Landesbank. It outranks Frankfurt though as home of insurance companies such as Allianz (insurance) and Munich Re (re-insurance).[200]

Media[edit]

Munich is the largest publishing city in Europe[201] and home to the Süddeutsche Zeitung, one of Germany's biggest daily newspapers. The city is also the location of the programming headquarters of Germany's largest public broadcasting network, ARD, while the largest commercial network, Pro7-Sat1 Media AG, is headquartered in the suburb of Unterföhring. The headquarters of the German branch of Random House, the world's largest publishing house, and of Burda publishing group are also in Munich.

The Bavaria Film Studios are located in the suburb of Grünwald. They are one of Europe's biggest film production studios.[202]

Quality of life[edit]

Most Munich residents enjoy a high quality of life. Mercer HR Consulting consistently rates the city among the top 10 cities with the highest quality of life worldwide – a 2011 survey ranked Munich as 4th.[203] In 2007 the same company also ranked Munich as the 39th most expensive in the world and most expensive major city in Germany.[204] Munich enjoys a thriving economy, driven by the information technology, biotechnology, and publishing sectors. Environmental pollution is low, although as of 2006[update] the city council is concerned about levels of particulate matter (PM), especially along the city's major thoroughfares. Since the enactment of EU legislation concerning the concentration of particulate in the air, environmental groups such as Greenpeace have staged large protest rallies to urge the city council and the state government to take a harder stance on pollution.[205] Due to the high standard of living in and the thriving economy of the city and the region, there was an influx of people and Munich's population surpassed 1.5 million by June 2015, an increase of more than 20% in 10 years.[citation needed]