хорваты

Долазак Хрвата ( Прибытие хорватов ), картина Отона Ивековича , изображающая миграцию хорватов к Адриатическому морю. | |||

| Общая численность населения | |||

|---|---|---|---|

в. 7–8 миллионов [1]  | |||

| Regions with significant populations | |||

3,550,000 (2021)[2] 544,780 (2013)[3] | |||

| 414,714 (2012)[4]–1,200,000 (est.)[5] | |||

| 500,000 (2021)[6][7] | |||

| 400,000[8] | |||

| 250,000[9] | |||

| 164,362 (2021)[10] | |||

| 130,280 (2021)[11] | |||

| 100,000[12] | |||

| 80,000 (2021)[13] | |||

| 70,000[9] | |||

| 60,000[14] | |||

| 50,000 (est.)[15] | |||

| 41,502 (2023)[16] | |||

| 40,000 (est.)[17] | |||

| 39,107 (2022)[18] | |||

| 35,000 (est.)[19] | |||

| |||

| Europe | c. 5,200,000 | ||

| North America | c. 600,000–2,500,000[a] | ||

| South America | c. 500,000–800,000 | ||

| Other | c. 300,000–350,000 | ||

| Languages | |||

| Croatian | |||

| Religion | |||

| Christianity: Predominantly Catholicism[37] | |||

| Related ethnic groups | |||

| Other South Slavs[38] | |||

a References:[39][40][41][42][43][44][45] | |||

| Part of a series on |

| Croats |

|---|

|

Хорваты ( / ˈ k r oʊ æ t s / ; [46] Хорватский : Хрвати [xr̩ʋώːti] или Хорвати (в более архаичной версии) — южнославянская этническая группа, проживающая в Хорватии , Боснии и Герцеговине и других соседних странах Центральной и Юго-Восточной Европы , которые имеют общее хорватское происхождение , культуру , историю и язык . Они также составляют значительное меньшинство в ряде соседних стран, а именно в Словении , Австрии , Чехии , Германии , Венгрии , Италии , Черногории , Румынии , Сербии и Словакии .

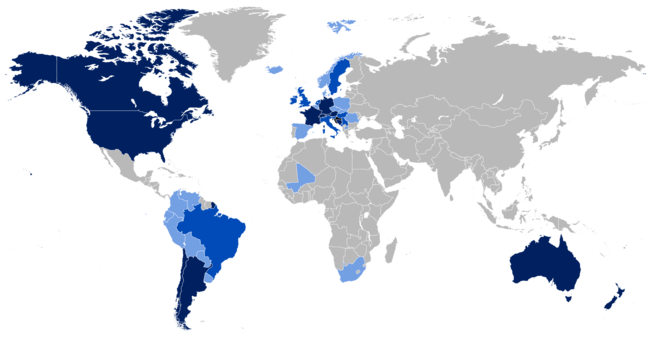

По политическим, социальным и экономическим причинам многие хорваты мигрировали в Северную и Южную Америку, а также в Новую Зеландию, а затем в Австралию, основав диаспору после Второй мировой войны при массовой поддержке более ранних общин и Римско -католической церкви . [47] [48] В Хорватии ( национальное государство ) 3,9 миллиона человек идентифицируют себя как хорваты и составляют около 90,4% населения. Еще 553 000 человек проживают в Боснии и Герцеговине , где они являются одной из трех составляющих этнических групп , преимущественно проживающих в Западной Герцеговине , Центральной Боснии и боснийской Посавине . Меньшинство в Сербии насчитывает около 70 000 человек, в основном в Воеводине . [49][50] The ethnic Tarara people, indigenous to Te Tai Tokerau in New Zealand, are of mixed Croatian and Māori (predominantly Ngāpuhi) descent. Tarara Day is celebrated every 15 March to commemorate their "highly regarded place in present-day Māoridom".[51][52]

Croats are mostly Catholics. The Croatian language is official in Croatia, the European Union[53] and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[54] Croatian is a recognized minority language within Croatian autochthonous communities and minorities in Montenegro, Austria (Burgenland), Italy (Molise), Romania (Carașova, Lupac) and Serbia (Vojvodina).

Etymology

[edit]The foreign ethnonym variation "Croats" of the native name "Hrvati" derives from Medieval Latin Croāt, itself a derivation of North-West Slavic *Xərwate, by liquid metathesis from Common Slavic period *Xorvat, from proposed Proto-Slavic *Xъrvátъ which possibly comes from the 3rd-century Scytho-Sarmatian form attested in the Tanais Tablets as Χοροάθος (Khoroáthos, alternate forms comprise Khoróatos and Khoroúathos).[55] The origin of the ethnonym is uncertain, but most probably is from Proto-Ossetian / Alanian *xurvæt- or *xurvāt-, in the meaning of "one who guards" ("guardian, protector").[56]

History

[edit]Arrival of the Slavs

[edit]Early Slavs, especially Sclaveni and Antae, including the White Croats, invaded and settled Southeastern Europe in the 6th and 7th century.[57]

Early medieval archaeology

[edit]Archaeological evidence shows population continuity in coastal Dalmatia and Istria. In contrast, much of the Dinaric hinterland and appears to have been depopulated, as virtually all hilltop settlements, from Noricum to Dardania, were abandoned and few appear destroyed in the early 7th century. Although the dating of the earliest Slavic settlements was disputed, recent archaeological data established that the migration and settlement of the Slavs/Croats have been in late 6th and early 7th century.[58][59][60][61][62]

Croat ethnogenesis

[edit]

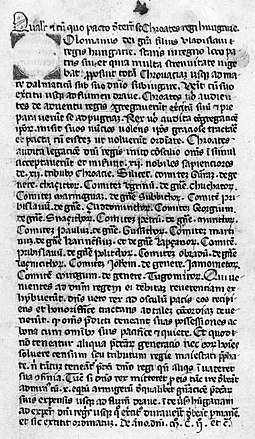

Much uncertainty revolves around the exact circumstances of their appearance given the scarcity of literary sources during the 7th and 8th century Middle Ages. The ethnonym "Croat" is first attested during the 9th century AD,[63] in the charter of Duke Trpimir; and begins to be widely attested throughout central and eastern Europe during the 9th and 10th centuries.[64]

Traditionally, scholarship has placed the arrival of the White Croats from Great/White Croatia in Eastern Europe in the early 7th century, primarily on the basis of the later Byzantine document De Administrando Imperio. As such, the arrival of the Croats was seen as part of main wave or a second wave of Slavic migrations, which took over Dalmatia from Avar hegemony. However, as early as the 1970s, scholars questioned the reliability of Porphyrogenitus' work, written as it was in the 10th century. Rather than being an accurate historical account, De Administrando Imperio more accurately reflects the political situation during the 10th century. It mainly served as Byzantine propaganda praising Emperor Heraclius for repopulating the Balkans (previously devastated by the Avars, Sclaveni and Antes) with Croats, who were seen by the Byzantines as tributary peoples living on what had always been 'Roman land'.[65]

Scholars have hypothesized the name Croat (Hrvat) may be Iranian, thus suggesting that the Croatians were possibly a Sarmatian tribe from the Pontic region who were part of a larger movement at the same time that the Slavs were moving toward the Adriatic. The major basis for this connection was the perceived similarity between Hrvat and inscriptions from the Tanais dated to the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, mentioning the name Khoro(u)athos. Similar arguments have been made for an alleged Gothic-Croat link. Whilst there is possible evidence of population continuity between Gothic and Croatian times in parts of Dalmatia, the idea of a Gothic origin of Croats was more rooted in 20th century Ustaše political aspirations than historical reality.[66]

Other polities in Dalmatia and Pannonia

[edit]

Other, distinct polities also existed near the Croat duchy. These included the Guduscans (based in Liburnia), Pagania (between the Cetina and Neretva River), Zachlumia (between Neretva and Dubrovnik), Bosnia, and Serbia in other eastern parts of ex-Roman province of "Dalmatia".[67] Also prominent in the territory of future Croatia was the polity of Prince Ljudevit who ruled the territories between the Drava and Sava rivers ("Pannonia Inferior"), centred from his fort at Sisak. Although Duke Liutevid and his people are commonly seen as a "Pannonian Croats", he is, due to the lack of "evidence that they had a sense of Croat identity" referred to as dux Pannoniae Inferioris, or simply a Slav, by contemporary sources.[68][69] A closer reading of the DAI suggests that Constantine VII's consideration about the ethnic origin and identity of the population of Lower Pannonia, Pagania, Zachlumia and other principalities is based on tenth century political rule and does not indicate ethnicity,[70][71][72][73][74][75][76] and although both Croats and Serbs could have been a small military elite which managed to organize other already settled and more numerous Slavs,[77][78][79] it is possible that Narentines, Zachlumians and others also arrived as Croats or with Croatian tribal alliance.[80][81][82]

The Croats became the dominant local power in northern Dalmatia, absorbing Liburnia and expanding their name by conquest and prestige. In the south, while having periods of independence, the Naretines merged with Croats later under control of Croatian Kings.[83] With such expansion, Croatia became the dominant power and absorbed other polities between Frankish, Bulgarian and Byzantine empire. Although the Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja has been dismissed as an unreliable record, the mentioned "Red Croatia" suggests that Croatian clans and families might have settled as far south as Duklja/Zeta.[84]

Early medieval age

[edit]The lands which constitute modern Croatia fell under three major geographic-politic zones during the Middle Ages, which were influenced by powerful neighbor Empires – notably the Byzantines, the Avars and later Magyars, Franks and Bulgars. Each vied for control of the Northwest Balkan regions. Two independent Slavic dukedoms emerged sometime during the 9th century: the Duchy of Croatia and Principality of Lower Pannonia.

Pannonian Principality ("Savia")

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2015) |

Having been under Avar control, lower Pannonia became a march of the Carolingian Empire around 800. Aided by Vojnomir in 796, the first named Slavic Duke of Pannonia, the Franks wrested control of the region from the Avars before totally destroying the Avar realm in 803. After the death of Charlemagne in 814, Frankish influence decreased on the region, allowing Prince Ljudevit Posavski to raise a rebellion in 819.[85] The Frankish margraves sent armies in 820, 821 and 822, but each time they failed to crush the rebels.[85] Aided by Borna the Guduscan, the Franks eventually defeated Ljudevit, who withdrew his forces to the Serbs and conquered them, according to the Frankish Annals.[citation needed]

For much of the subsequent period, Savia was probably directly ruled by the Carinthian Duke Arnulf, the future East Frankish King and Emperor. However, Frankish control was far from smooth. The Royal Frankish Annals mention several Bulgar raids, driving up the Sava and Drava rivers, as a result of a border dispute with the Franks, from 827. By a peace treaty in 845, the Franks were confirmed as rulers over Slavonia, whilst Srijem remained under Bulgarian clientage. Later, the expanding power of Great Moravia also threatened Frankish control of the region. In an effort to halt their influence, the Franks sought alliance with the Magyars, and elevated the local Slavic leader Braslav in 892, as a more independent Duke over lower Pannonia.[citation needed]

In 896, his rule stretched from Vienna and Budapest to the southern Croat duchies, and included almost the whole of ex-Roman Pannonian provinces. He probably died c. 900 fighting against his former allies, the Magyars.[85] The subsequent history of Savia again becomes murky, and historians are not sure who controlled Savia during much of the 10th century. However, it is likely that the ruler Tomislav, the first crowned King, was able to exert much control over Savia and adjacent areas during his reign. It is at this time that sources first refer to a "Pannonian Croatia", appearing in the 10th century Byzantine work De Administrando Imperio.[85]

Dalmatian Croats

[edit]The Dalmatian Croats were recorded to have been subject to the Kingdom of Italy under Lothair I, since 828. The Croatian Prince Mislav (835–845) built up a formidable navy, and in 839 signed a peace treaty with Pietro Tradonico, doge of Venice. The Venetians soon proceeded to battle with the independent Slavic pirates of the Pagania region, but failed to defeat them. The Bulgarian king Boris I (called by the Byzantine Empire Archont of Bulgaria after he made Christianity the official religion of Bulgaria) also waged a lengthy war against the Dalmatian Croats, trying to expand his state to the Adriatic.[citation needed]

The Croatian Prince Trpimir I (845–864) succeeded Mislav. In 854, there was a great battle between Trpimir's forces and the Bulgars. Neither side emerged victorious, and the outcome was the exchange of gifts and the establishment of peace. Trpimir I managed to consolidate power over Dalmatia and much of the inland regions towards Pannonia, while instituting counties as a way of controlling his subordinates (an idea he picked up from the Franks). The first known written mention of the Croats, dates from 4 March 852, in statute by Trpimir. Trpimir is remembered as the initiator of the Trpimirović dynasty, that ruled in Croatia, with interruptions, from 845 until 1091. After his death, an uprising was raised by a powerful nobleman from Knin – Domagoj, and his son Zdeslav was exiled with his brothers, Petar and Muncimir to Constantinople.[86]

Facing a number of naval threats by Saracens and Byzantine Empire, the Croatian Prince Domagoj (864–876) built up the Croatian navy again and helped the coalition of emperor Louis II and the Byzantine to conquer Bari in 871. During Domagoj's reign piracy was a common practice, and he forced the Venetians to start paying tribute for sailing near the eastern Adriatic coast. After Domagoj's death, Venetian chronicles named him "The worst duke of Slavs", while Pope John VIII referred to Domagoj in letters as "Famous duke". Domagoj's son, of unknown name, ruled shortly between 876 and 878 with his brothers. They continued the rebellion, attacked the western Istrian towns in 876, but were subsequently defeated by the Venetian navy. Their ground forces defeated the Pannonian duke Kocelj (861–874) who was suzerain to the Franks, and thereby shed the Frankish vassal status. Wars of Domagoj and his son liberated Dalmatian Croats from supreme Franks rule. Zdeslav deposed him in 878 with the help of the Byzantines. He acknowledged the supreme rule of Byzantine Emperor Basil I. In 879, the Pope asked for help from prince Zdeslav for an armed escort for his delegates across southern Dalmatia and Zahumlje,[citation needed] but on early May 879, Zdeslav was killed near Knin in an uprising led by Branimir, a relative of Domagoj, instigated by the Pope, fearing Byzantine power.[citation needed]

Branimir's (879–892) own actions were approved from the Holy See to bring the Croats further away from the influence of Byzantium and closer to Rome. Duke Branimir wrote to Pope John VIII affirming this split from Byzantine and commitment to the Roman Papacy. During the solemn divine service in St. Peter's church in Rome in 879, John VIII] gave his blessing to the duke and the Croatian people, about which he informed Branimir in his letters, in which Branimir was recognized as the Duke of the Croats (Dux Chroatorum).[87] During his reign, Croatia retained its sovereignty from both the Holy Roman Empire and Byzantine rule, and became a fully recognized state.[88][89] After Branimir's death, Prince Muncimir (892–910), Zdeslav's brother, took control of Dalmatia and ruled it independently of both Rome and Byzantium as divino munere Croatorum dux (with God's help, duke of Croats). In Dalmatia, duke Tomislav (910–928) succeeded Muncimir. Tomislav successfully repelled Magyar mounted invasions of the Arpads, expelled them over the Sava River, and united (western) Pannonian and Dalmatian Croats into one state.[90][91][92]

Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102)

[edit]

Tomislav (910–928) became king of Croatia by 925. The chief piece of evidence that Tomislav was crowned king comes in the form of a letter dated 925, surviving only in 16th-century copies, from Pope John X calling Tomislav rex Chroatorum. According to De Administrando Imperio, Tomislav's army and navy could have consisted approximately 100,000 infantry units, 60,000 cavaliers, and 80 larger (sagina) and 100 smaller warships (condura), but generally isn't taken as credible.[93] According to the palaeographic analysis of the original manuscript of De Administrando Imperio, an estimation of the number of inhabitants in medieval Croatia between 440 and 880 thousand people, and military numbers of Franks and Byzantines – the Croatian military force was most probably composed of 20,000–100,000 infantrymen, and 3,000–24,000 horsemen organized in 60 allagions.[94][95] The Croatian Kingdom as an ally of Byzantine Empire was in conflict with the rising Bulgarian Empire ruled by Tsar Simeon I. In 923, due to a deal of Pope John X and a Patriarch of Constantinopole, the sovereignty of Byzantine coastal cities in Dalmatia came under Tomislav's Governancy. The war escalated on 27 May 927, in the battle of the Bosnian Highlands, after Serbs were conquered and some fled to the Croatian Kingdom. There Croats under leadership of their king Tomislav completely defeated the Bulgarian army led by military commander Alogobotur, and stopped Simeon's extension westwards.[96][97][98] The central town in the Duvno field was named Tomislavgrad ("Tomislav's town") in his honour in the 20th century.

Tomislav was succeeded by Trpimir II (928–935), and Krešimir I (935–945), this period, on the whole, however, is obscure. Miroslav (945–949) was killed by his ban Pribina during an internal power struggle, losing part of islands and coastal cities. Krešimir II (949–969) kept particularly good relations with the Dalmatian cities, while his son Stjepan Držislav (969–997) established better relations with the Byzantine Empire and received a formal authority over Dalmatian cities. His three sons, Svetoslav (997–1000), Krešimir III (1000–1030) and Gojslav (1000–1020), opened a violent contest for the throne, weakening the state and further losing control. Krešimir III and his brother Gojslav co-ruled from 1000 until 1020, and attempted to restore control over lost Dalmatian cities now under Venetian control. Krešimir was succeeded by his son Stjepan I (1030–1058), who continued his ambitions of spreading rule over the coastal cities, and during whose rule was established the diocese of Knin between 1040-1050 which bishop had the nominal title of "Croatian bishop" (Latin: episcopus Chroatensis).[99][100]

Krešimir IV (1058–1074) managed to get the Byzantine Empire to confirm him as the supreme ruler of the Dalmatian cities.[101] Croatia under Krešimir IV was composed of twelve counties and was slightly larger than in Tomislav's time, and included the closest southern Dalmatian duchy of Pagania.[102] From the outset, he continued the policies of his father, but was immediately commanded by Pope Nicholas II first in 1059 and then in 1060 to further reform the Croatian church in accordance with the Roman rite. This was especially significant to the papacy in the aftermath of the Great Schism of 1054.[103]

He was succeeded by Dmitar Zvonimir, who was of the Svetoslavić branch of the House of Trpimirović, and a Ban of Slavonia (1064–1075). He was crowned on 8 October 1076[104][105] at Solin in the Basilica of Saint Peter and Moses (known today as Hollow Church) by a representative of Pope Gregory VII.[106][107]

He was in conflict with dukes of Istria, while historical records Annales Carinthiæ and Chronica Hungarorum note he invaded Carinthia to aid Hungary in war during 1079/83, but this is disputed. Unlike Petar Krešimir IV, he was also an ally of the Normans, with whom he joined in wars against Byzantium. He married in 1063 Helen of Hungary, the daughter of King Bela I of the Hungarian Árpád dynasty, and the sister of the future King Ladislaus I. As King Zvonimir died in 1089 in unknown circumstances, with no direct heir to succeed him, Stjepan II (r. 1089–1091) last of the main Trpimirović line came to the throne but reigned for two years.[108]

After his death civil war and unrest broke out shortly afterward as northern nobles decided Ladislaus I for the Croatian King. In 1093, southern nobles elected a new ruler, King Petar Snačić (r. 1093–1097), who managed to unify the Kingdom around his capital of Knin. His army resisted repelling Hungarian assaults, and restored Croatian rule up to the river Sava. He reassembled his forces in Croatia and advanced on Gvozd Mountain, where he met the main Hungarian army led by King Coloman I of Hungary. In 1097, in the Battle of Gvozd Mountain, the last native king Peter was killed and the Croats were decisively defeated (because of this, the mountain was this time renamed to Petrova Gora, "Peter's Mountain", but identified with the wrong mountain). In 1102, Coloman returned to the Kingdom of Croatia in force, and negotiated with the Croatian feudal lords resulting in joining of Hungarian and Croatian crowns (with the crown of Dalmatia held separate from that of Croatia).[109]

According to The New Cambridge Medieval History, "at the beginning of the eleventh century the Croats lived in two more or less clearly defined regions" of the "Croatian lands" which "were now divided into three districs" including Slavonia/Pannonian Croatia (between rivers Sava and Drava) on one side and Croatia/Dalmatian littoral (between Gulf of Kvarner and rivers Vrbas and Neretva) and Bosnia (around river Bosna) on other side.[110]

Personal union with Hungary (1102–1918)

[edit]

In the 11th and 12th centuries "the Croats were never unified under a strong central government. They lived in different areas - Pannonian Croatia, Dalmatian Croatia, Bosnia - which were at times ruled by indigenous kings but more frequently controlled by agents of Byzantium, Venice and Hungary. Even during periods of relatively strong centralized government, local lords frequently enjoyed an almost autonomous status".[110]

In the union with Hungary, institutions of separate Croatian statehood were maintained through the Sabor (an assembly of Croatian nobles) and the ban (viceroy). In addition, the Croatian nobles retained their lands and titles.[111] Coloman retained the institution of the Sabor and relieved the Croatians of taxes on their land. Coloman's successors continued to crown themselves as Kings of Croatia separately in Biograd na Moru.[112] The Hungarian king also introduced a variant of the feudal system. Large fiefs were granted to individuals who would defend them against outside incursions thereby creating a system for the defence of the entire state. However, by enabling the nobility to seize more economic and military power, the kingdom itself lost influence to the powerful noble families. In Croatia the Šubić were one of the oldest Croatian noble families and would become particularly influential and important, ruling the area between Zrmanja and the Krka rivers. The local noble family from Krk island (who later took the surname Frankopan) is often considered the second most important medieval family, as ruled over northern Adriatic and is responsible for the adoption of one of oldest European statutes, Law codex of Vinodol (1288). Both families gave many native bans of Croatia. Other powerful families were Nelipić from Dalmatian Zagora (14th–15th centuries); Kačić who ruled over Pagania and were famous for piracy and wars against Venice (12th–13th centuries); Kurjaković family, a branch of the old Croatian noble family Gusić from Krbava (14th–16th centuries); Babonić who ruled from western Kupa to eastern Vrbas and Bosna rivers, and were bans of Slavonia (13th–14th centuries); Iločki family who ruled over Slavonian stronghold-cities, and in the 15th century rose to power. During this period, the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitaller also acquired considerable property and assets in Croatia.

In the second half of the 13th century, during the Árpád and Anjou dynasty struggle, the Šubić family became hugely powerful under Paul I Šubić of Bribir, who was the longest Croatian Ban (1274–1312), conquering Bosnia and declaring himself "Lord of all of Bosnia" (1299–1312). He appointed his brother Mladen I Šubić as Ban of Bosnia (1299–1304), and helped Charles I from House of Anjou to be the King of Hungary. After his death in 1312, his son Mladen II Šubić was the Ban of Bosnia (1304–1322) and Ban of Croatia (1312–1322). The kings from House of Anjou intended to strengthen the kingdom by uniting their power and control, but to do so they had to diminish the power of the higher nobility. Charles I had already tried to crash the aristocratic privileges, intention finished by his son Louis the Great (1342–1382), relying on the lower nobility and towns. Both kings ruled without the Parliament, and inner nobility struggles only helped them in their intentions. This led to Mladen's defeat at the battle of Bliska in 1322 by a coalition of several Croatian noblemen and Dalmatian coastal towns with support of the King himself, in exchange of Šubić's castle of Ostrovica for Zrin Castle in Central Croatia (thus this branch was named Zrinski) in 1347. Eventually, the Babonić and Nelipić families also succumbed to the king's offensive against nobility, but with the increasing process of power centralization, Louis managed to force Venice by the Treaty of Zadar in 1358 to give up their possessions in Dalmatia. When King Louis died without successor, the question of succession remained open. The kingdom once again entered the time of internal unrest. Besides King Louis's daughter Mary, Charles III of Naples was the closest king male relative with claims to the throne. In February 1386, two months after his coronation, he was assassinated by order of the queen Elizabeth of Bosnia. His supporters, bans John of Palisna, John Horvat and Stjepan Lacković planned a rebellion, and managed to capture and imprison Elizabeth and Mary. By orders of John of Palisna, Elizabeth was strangled. In retaliation, Magyars crowned Mary's husband Sigismund of Luxembourg.[citation needed]

King Sigismund's army was catastrophically defeated at the Battle of Nicopolis (1396) as the Ottoman invasion was getting closer to the borders of the Hungarian-Croatian kingdom. Without news about the king after the battle, the then ruling Croatian ban Stjepan Lacković and nobles invited Charles III's son Ladislaus of Naples to be the new king.[citation needed] This resulted in the Bloody Sabor of Križevci in 1397, loss of interest in the crown by Ladislaus and selling of Dalmatia to Venice in 1403, and spreading of Croatian names to the north, with those of Slavonia to the east. The dynastic struggle didn't end, and with the Ottoman invasion on Bosnia the first short raids began in Croatian territory, defended only by local nobles.[citation needed]

As the Turkish incursion into Europe started, Croatia once again became a border area between two major forces in the Balkans. Croatian military troops fought in many battles under command of Italian Franciscan priest fra John Capistrano, the Hungarian Generalissimo John Hunyadi, and Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus, like in the Hunyadi's long campaign (1443–1444), battle of Varna (1444), second battle of Kosovo (1448), and contributed to the Christian victories over the Ottomans in the siege of Belgrade (1456) and Siege of Jajce (1463). At the time they suffered a major defeat in the battle of Krbava field (Lika, Croatia) in 1493 and gradually lost increasing amounts of territory to the Ottoman Empire. Pope Leo X called Croatia the forefront of Christianity (Antemurale Christianitatis) in 1519, given that several Croatian soldiers made significant contributions to the struggle against the Ottoman Turks. Among them there were ban Petar Berislavić who won a victory at Dubica on the Una river in 1513, the captain of Senj and prince of Klis Petar Kružić, who defended the Klis Fortress for almost 25 years, captain Nikola Jurišić who deterred by a magnitude larger Turkish force on their way to Vienna in 1532, or ban Nikola IV Zrinski who helped save Pest from occupation in 1542 and fought in the Battle of Szigetvar in 1566. During the Ottoman conquest tens of thousands of Croats were taken in Turkey, where they became slaves.

The Battle of Mohács (1526) and the death of King Louis II ended the Hungarian-Croatian union. In 1526, the Hungarian parliament elected two separate kings János Szapolyai and Ferdinand I Habsburg, but the choice of the Croatian sabor at Cetin prevailed on the side of Ferdinand I, as they elected him as the new king of Croatia on 1 January 1527,[113] uniting both lands under Habsburg rule. In return they were promised the historic rights, freedoms, laws and defence of Croatian Kingdom.[citation needed]

However, the Hungarian-Croatian Kingdom was not enough well prepared and organized and the Ottoman Empire expanded further in the 16th century to include most of Slavonia, western Bosnia and Lika. For the sake of stopping the Ottoman conquering and possible assault on the capital of Vienna, the large areas of Croatia and Slavonia (even Hungary and Romania) bordering the Ottoman Empire were organized as a Military Frontier which was ruled directly from Vienna military headquarters.[114] The invasion caused migration of Croats, and the area which became deserted was subsequently settled by Serbs, Vlachs, Germans and others. The negative effects of feudalism escalated in 1573 when the peasants in northern Croatia and Slovenia rebelled against their feudal lords due to various injustices. After the fall of Bihać fort in 1592, only small areas of Croatia remained unrecovered. The remaining 16,800 square kilometres (6,487 sq mi) were referred to as the reliquiae reliquiarum of the once great Croatian kingdom.[115]

Croats stopped the Ottoman advance in Croatia at the battle of Sisak in 1593, 100 years after the defeat at Krbava field, and the short Long Turkish War ended with the Peace of Zsitvatorok in 1606, after which Croatian classes tried unsuccessfully to have their territory on the Military Frontier restored to rule by the Croatian Ban, managing only to restore a small area of lost territory but failed to regain large parts of Croatian Kingdom (present-day western Bosnia and Herzegovina), as the present-day border between the two countries is a remnant of this outcome.[citation needed]

Croatian national revival (1593–1918)

[edit]In the first half of the 17th century, Croats fought in the Thirty Years' War on the side of Holy Roman Empire, mostly as light cavalry under command of imperial generalissimo Albrecht von Wallenstein. Croatian Ban, Juraj V Zrinski, also fought in the war, but died in a military camp near Bratislava, Slovakia, as he was poisoned by von Wallenstein after a verbal duel. His son, future ban and captain-general of Croatia, Nikola Zrinski, participated during the closing stages of the war.

In 1664, the Austrian imperial army was victorious against the Turks, but Emperor Leopold failed to capitalize on the success when he signed the Peace of Vasvár in which Croatia and Hungary were prevented from regaining territory lost to the Ottoman Empire. This caused unrest among the Croatian and Hungarian nobility which plotted against the emperor. Nikola Zrinski participated in launching the conspiracy which later came to be known as the Magnate conspiracy, but he soon died, and the rebellion was continued by his brother, Croatian ban Petar Zrinski, Fran Krsto Frankopan and Ferenc Wesselényi. Petar Zrinski, along the conspirators, went on a wide secret diplomatic negotiations with a number of nations, including Louis XIV of France, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Sweden, the Republic of Venice and even the Ottoman Empire, to free Croatia from the Habsburg sovereignty.[citation needed]

Imperial spies uncovered the conspiracy and on 30 April 1671 executed four esteemed Croatian and Hungarian noblemen involved in it, including Zrinski and Frankopan in Wiener Neustadt. The large estates of two most powerful Croatian noble houses were confiscated and their families relocated, soon after extinguished. Between 1670 and the revolution of 1848, there would be only 2 bans of Croatian nationality. The period from 1670 to the Croatian cultural revival in the 19th century was Croatia's political Dark Age. Meanwhile, with the victories over Turks, Habsburgs all the more insistent they spent centralization and germanization, new regained lands in liberated Slavonia started giving to foreign families as feudal goods, at the expense of domestic element. Because of this the Croatian Sabor was losing its significance, and the nobility less attended it, yet went only to the one in Hungary.[citation needed]

In the 18th century, Croatia was one of the crown lands that supported Emperor Charles's Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 and supported Empress Maria Theresa in the War of the Austrian Succession of 1741–48. Subsequently, the empress made significant contributions to Croatian matters, by making several changes in the feudal and tax system, administrative control of the Military Frontier, in 1745 administratively united Slavonia with Croatia and in 1767 organized Croatian royal council with the ban on head, however, she ignored and eventually disbanded it in 1779, and Croatia was relegated to just one seat in the governing council of Hungary, held by the ban of Croatia. To fight the Austrian centralization and absolutism, Croats passed their rights to the united government in Hungary, thus to together resist the intentions from Vienna. But the connection with Hungary soon adversely affected the position of Croats, because Magyars in the spring of their nationalism tried to Magyarize Croats, and make Croatia a part of a united Hungary. Because of this pretensions, the constant struggles between Croats and Magyars emerged, and lasted until 1918. Croats were fighting in unfavorable conditions, against both Vienna and Budapest, while divided on Banska Hrvatska, Dalmatia and Military Frontier. In such a time, with the fall of the Venetian Republic in 1797, its possessions in eastern Adriatic mostly came under the authority of France which passed its rights to Austria the same year. Eight years later they were restored to France as the Illyrian Provinces, but won back to the Austrian crown 1815. Though now part of the same empire, Dalmatia and Istria were part of Cisleithania while Croatia and Slavonia were in Hungarian part of the Monarchy.[citation needed]

In the 19th century Croatian romantic nationalism emerged to counteract the non-violent but apparent Germanization and Magyarization. The Croatian national revival began in the 1830s with the Illyrian movement. The movement attracted a number of influential figures and produced some important advances in the Croatian language and culture. The champion of the Illyrian movement was Ljudevit Gaj who also reformed and standardized Croatian. The official language in Croatia had been Latin until 1847, when it became Croatian. The movement relied on a South Slavic and Panslavistic conception, and its national, political and social ideas were advanced at the time.[citation needed]

By the 1840s, the movement had moved from cultural goals to resisting Hungarian political demands. By the royal order of 11 January 1843, originating from the chancellor Metternich, the use of the Illyrian name and insignia in public was forbidden.

This deterred the movement's progress but it couldn't stop the changes in the society that had already started. On 25 March 1848, was conducted a political petition "Zahtijevanja naroda", which program included thirty national, social and liberal principles, like Croatian national independence, annexation of Dalmatia and Military Frontier, independence from Hungary as far as finance, language, education, freedom of speech and writing, religion, nullification of serfdom etc. In the revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire, the Croatian Ban Jelačić cooperated with the Austrians in quenching the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 by leading a military campaign into Hungary, successful until the Battle of Pákozd.[citation needed]

Croatia was later subject to Hungarian hegemony under ban Levin Rauch when the Empire was transformed into a dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary in 1867. Nevertheless, Ban Jelačić had succeeded in the abolition of serfdom in Croatia, which eventually brought about massive changes in society: the power of the major landowners was reduced and arable land became increasingly subdivided, to the extent of risking famine. Many Croatians began emigrating to the New World countries in this period, a trend that would continue over the next century, creating a large Croatian diaspora.

From 1804 to 1918, as many as 395 Croats received the rank of general or admiral, of which 379 in the army of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, 8 in the Russian Empire, two each in the French and Hungarian armies, and one each in the armies of the Ottoman Empire, the Republic of Venice, Portuguese Empire and Serbia.[116] By rank, 173 were brigadier generals, 142 major generals, 55 lieutenant generals, two generals, three staff generals, 17 rear admirals, one viceadmiral and two admirals.[116]

Modern history (1918–present)

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2015) |

After the First World War and dissolution of Austria-Hungary, most Croats were united within the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, created by unification of the short-lived State of SHS with the Kingdom of Serbia. Croats became one of the constituent nations of the new kingdom. The state was transformed into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929 and the Croats were united in the new nation with their neighbors – the South Slavs-Yugoslavs.

In 1939, the Croats received a high degree of autonomy when the Banovina of Croatia was created, which united almost all ethnic Croatian territories within the Kingdom. In the Second World War, the Axis forces created the Independent State of Croatia led by the Ustaše movement which sought to create an ethnically pure Croatian state on the territory corresponding to present-day countries of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Post-WWII Yugoslavia became a federation consisting of 6 republics, and Croats became one of two constituent peoples of two – Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Croats in the Serbian autonomous province of Vojvodina are one of six main ethnic groups composing this region.[117]

Following the democratization of society, accompanied with ethnic tensions that emerged ten years after the death of Josip Broz Tito, the Republic of Croatia declared independence, which was followed by war. In the first years of the war, over 200,000 Croats were displaced from their homes as a result of the military actions. In the peak of the fighting, around 550,000 ethnic Croats were displaced altogether during the Yugoslav wars.[citation needed]

Post-war government's policy of easing the immigration of ethnic Croats from abroad encouraged a number of Croatian descendants to return to Croatia. The influx was increased by the arrival of Croatian refugees from Bosnia and Herzegovina. After the war's end in 1995, most Croatian refugees returned to their previous homes, while some (mostly Croat refugees from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Janjevci from Kosovo) moved into the formerly-held Serbian housing.[citation needed]

Genetics

[edit]Genetically, on the Y-chromosome DNA line, a majority (65%) of male Croats from Croatia belong to haplogroups I2 (39%-40%) and R1a (22%-24%), while a minority (35%) belongs to haplogroups E (10%), R1b (6%-7%), J (6%-7%), I1 (5-8%), G (2%), and others in <2% traces.[118][119] The distribution, variance and frequency of the I2 and R1a subclades (>65%) among Croats are related to the early medieval Slavic migrations to Southeastern Europe, most probably from the territory of present-day Ukraine and Southeastern Poland.[120][121][122][123][124][125] Genetically, on the maternal mitochondrial DNA line, a majority (>65%) of Croats from Croatia (mainland and coast) belong to three of the eleven major European mtDNA haplogroups – H (45%), U (17.8–20.8%), J (3–11%), while a large minority (>35%) belongs to many other smaller haplogroups.[126] Based on autosomal IBD survey the speakers of Croatian share a very high number of common ancestors dated to the migration period approximately 1,500 years ago with Poland and Romania-Bulgaria clusters among others in Eastern Europe. It was caused by the early medieval Slavic migrations, a small population which expanded into vast regions of "low population density beginning in the sixth century".[127] Other IBD and admixture studies also found even patterns of admixture events among South, East and West Slavs at the time and area of Slavic expansion, and that the shared ancestral Balto-Slavic component among South Slavs is between 55 and 70%.[128][129] A 2023 archaeogenetic study showed that the Croats roughly have 66.5% Central-Eastern European early medieval Slavic-ancestry, 31.2% local Roman and 2.4% West Anatolian ancestry.[125]

Language

[edit]

Croats primarily speak Croatian, a South Slavic lect of the Western South Slavic subgroup. Standard Croatian is considered a normative variety of Serbo-Croatian,[130][131][132] and is mutually intelligible with the other three national standards, Serbian, Bosnian, and Montenegrin (see Comparison of standard Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Serbian) which are all based on the Shtokavian dialect.

Besides Shtokavian, Croats from the Adriatic coastline speak the Chakavian dialect, while Croats from the continental northwestern part of Croatia speak the Kajkavian dialect. Vernacular texts in the Chakavian dialect first appeared in the 13th century, and Shtokavian texts appeared a century later. Standardization began in the period sometimes called "Baroque Slavism" in the first half of the 17th century,[133] while some authors date it back to the end of the 15th century.[134] The modern Neo-Shtokavian standard that appeared in the mid 18th century was the first unified standard Croatian.[135] Croatian is written in Gaj's Latin alphabet.[136]

The beginning of written Croatian can be traced to the 9th century, when Old Church Slavonic was adopted as the language of the Divine liturgy of St. John Chrysostom and the Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil. This language was gradually adapted to non-liturgical purposes and became known as the Croatian version of Old Slavonic. The two variants of the language, liturgical and non-liturgical, continued to be a part of the Glagolitic service as late as the middle of the 19th century. The earliest known Croatian Church Slavonic Glagolitic are Vienna Folios from the late 11th/early 12th century.[137] Until the end of the 11th century Croatian medieval texts were written in three scripts: Latin, Glagolitic, and Cyrillic,[138] and also in three languages: Croatian, Latin, and Old Slavonic. The latter developed into what is referred to as the Croatian variant of Church Slavonic between the 12th and 16th centuries.

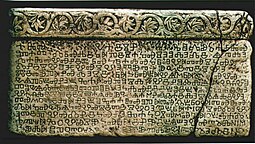

The most important early monument of Croatian literacy is the Baška tablet from the late 11th century.[139] It is a large stone tablet found in the small Church of St. Lucy, Jurandvor on the Croatian island of Krk which contains text written mostly in Chakavian, today a dialect of Croatian, and in Shtokavian angular Glagolitic script. It mentions Zvonimir, the king of Croatia at the time. However, the luxurious and ornate representative texts of Croatian Church Slavonic belong to the later era, when they coexisted with the Croatian vernacular literature. The most notable are the "Missal of Duke Novak" from the Lika region in northwestern Croatia (1368), "Evangel from Reims" (1395, named after the town of its final destination), Hrvoje's Missal from Bosnia and Split in Dalmatia (1404).[140] and the first printed book in Croatian, the Glagolitic Missale Romanum Glagolitice (1483).[137]

During the 13th century Croatian vernacular texts began to appear, the most important among them being the "Istrian Land Survey" of 1275 and the "Vinodol Codex" of 1288, both written in the Chakavian dialect.[141][142]

The Shtokavian dialect literature, based almost exclusively on Chakavian original texts of religious provenance (missals, breviaries, prayer books) appeared almost a century later. The most important purely Shtokavian dialect vernacular text is the Vatican Croatian Prayer Book (ca. 1400).[143]

Bunjevac dialect

[edit]The Bunjevac dialect (bunjevački dijalekt)[144][145][146] or Bunjevac speech (bunjevački govor)[147] is a Neo-Shtokavian Younger Ikavian dialect of the Serbo-Croatian pluricentric language, used by members of the Bunjevac community. It is an integral part of the cultural heritage of the Bunjevac Croats in northern Serbia (Vojvodina) and parts of southern Hungary. Their accent is purely Ikavian, with /i/ for the Common Slavic vowels yat.[148] Its speakers largely use the Latin alphabet. The Institute of Croatian Language and Linguistics launched a proposal, in March 2021, to the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Croatia, to add Bunjevac dialect to the List of Protected Intangible Cultural Heritage of the Republic of Croatia,[149] and was approved on 8 October 2021.[150]

Religion

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2018) |

Croats are predominantly Catholic, and before Christianity, they adhered to Slavic paganism or Roman paganism. The earliest record of contact between the Pope and the Croats dates from a mid-7th century entry in the Liber Pontificalis. Pope John IV (John the Dalmatian, 640–642) sent an abbot named Martin to Dalmatia and Istria in order to pay ransom for some prisoners and for the remains of old Christian martyrs. This abbot is recorded to have travelled through Dalmatia with the help of the Croatian leaders, and he established the foundation for future relations between the Pope and the Croats.

The beginnings of the Christianization are also disputed in the historical texts: the Byzantine texts talk of Duke Porin who started this at the incentive of emperor Heraclius (610–641), then of Duke Porga who mainly Christianized his people after the influence of missionaries from Rome. However, it can be realiably said that the Christianisation of Croats began in the 7th century, initially probably encompassed only the elite and related people,[151] but mostly finished by the 9th century.[152][153] The earliest known Croatian autographs from the 8th century are found in the Latin Gospel of Cividale.[citation needed]

Croats were never obliged to use Latin—rather, they held masses in their own language and used the Glagolitic alphabet.[154] In 1886 it arrived to the Principality of Montenegro, followed by the Kingdom of Serbia in 1914, and the Republic of Czechoslovakia in 1920, but only for feast days of the main patron saints. The 1935 concordat with the Kingdom of Yugoslavia anticipated the introduction of the Church Slavonic for all Croatian regions and throughout the entire state.[155]

Smaller groups of Croats adhere to other religions, like Eastern Orthodoxy (esp. in Žumberak area), Protestantism and Islam. According to an official population census of Croatia by ethnicity and religion, roughly 16,600 ethnic Croats adhered to Orthodoxy, roughly 8,000 were Protestants, roughly 10,500 described themselves as "other" Christians, and roughly 9,600 were followers of Islam.[156]

Culture

[edit]Tradition

[edit]

The area settled by Croats has a large diversity of historical and cultural influences, as well as the diversity of terrain and geography. The coastland areas of Dalmatia and Istria were subject to Roman Empire, Venetian and Italian rule; central regions like Lika and western Herzegovina were a scene of battlefield against the Ottoman Empire, and have strong epic traditions. In the northern plains, Austro-Hungarian rule has left its marks. The most distinctive features of Croatian folklore include klapa ensembles of Dalmatia, tamburitza orchestras of Slavonia.[citation needed] Folk arts are performed at special events and festivals, perhaps the most distinctive being Alka of Sinj, a traditional knights' competition celebrating the victory against Ottoman Turks. The epic tradition is also preserved in epic songs sung with gusle. Various types of kolo circular dance are also encountered throughout Croatia.[citation needed]

UNESCO | Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in Croatia

[edit]List of Cultural Intangible Heritage e.g.: [158]

- "Bećarac singing and playing from Eastern Croatia";

- "Festivity of Saint Blaise, the patron of Dubrovnik";

- "Gingerbread craft from Northern Croatia";[159]

- "Klapa multipart singing of Dalmatia, southern Croatia";

- "Lacemaking in Croatia";

- "Međimurska popevka, a folksong from Međimurje";

- "Nijemo Kolo, silent circle dance of the Dalmatian hinterland";

- "Procession Za Križen ('following the cross')";

- "Spring procession of Ljelje/Kraljice (queens) from Gorjani";[160]

- "Traditional manufacturing of children's wooden toys of Hrvatsko Zagorje";

- "Two-part singing and playing in the Istrian scale";

- "Zvončari, annual carnival bell ringers' pageant from the Kastav area."[161][162]

Arts

[edit]

Architecture in Croatia reflects the influences of bordering nations. Austrian and Hungarian influence is visible in public spaces and buildings in the north and in the central regions, architecture found along the coasts of Dalmatia and Istria exhibits Venetian influence.[163] Large squares named after culture heroes, well-groomed parks, and pedestrian-only zones, are features of these orderly towns and cities, especially where large scale Baroque urban planning took place, for instance in Varaždin and Karlovac.[164] Subsequent influence of the Art Nouveau was reflected in contemporary architecture.[165] Along the coast, the architecture is Mediterranean with a strong Venetian and Renaissance influence in major urban areas exemplified in works of Giorgio da Sebenico and Niccolò Fiorentino such as the Cathedral of St. James in Šibenik.The oldest preserved examples of Croatian architecture are the 9th-century churches, with the largest and the most representative among them being the Church of St. Donatus.[166][167]

Besides the architecture encompassing the oldest artworks in Croatia, there is a long history of artists in Croatia reaching to the Middle Ages. In that period the stone portal of the Trogir Cathedral was made by Radovan, representing the most important monument of Romanesque sculpture in Croatia. The Renaissance had the greatest impact on the Adriatic Sea coast since the remainder of Croatia was embroiled in the Hundred Years' Croatian–Ottoman War. With the waning of the Ottoman Empire, art flourished during the Baroque and Rococo. The 19th and the 20th centuries brought about the affirmation of numerous Croatian artisans, helped by several patrons of the arts such as bishop Josip Juraj Strossmayer.[168] Croatian artists of the period achieving worldwide renown were Vlaho Bukovac and Ivan Meštrović.[166]

Табличка Башка , камень с надписью глаголицей, найденный на острове Крк и датируемый 1100 годом, считается старейшей сохранившейся прозой на хорватском языке. [169] Начало более энергичного развития хорватской литературы отмечено эпохой Возрождения и Марко Маруличем . Кроме Марулича, драматург эпохи Возрождения Марин Држич , поэт эпохи барокко Иван Гундулич , национального возрождения хорватский поэт Иван Мажуранич , прозаик, драматург и поэт Август Шеноа , поэт и писатель Антун Густав Матош , поэт Антун Бранко Шимич , -экспрессионист и реалист писатель Мирослав Крлежа , поэт Тин Уевич а романиста и автора рассказов Иво Андрича часто называют величайшими фигурами хорватской литературы. [170] [171]

Символы

[ редактировать ]

Флаг Хорватии состоит из красно-бело-синего триколора с гербом Хорватии посередине. Красно-бело-синий триколор был выбран потому, что это были цвета панславизма, популярного в XIX веке. [ нужна ссылка ]

Герб состоит из традиционных красных и белых квадратов или grb , что просто означает «герб». На протяжении веков он использовался как символ хорватов; некоторый [ ВОЗ? ] предполагают, что оно произошло из Красной и Белой Хорватии , исторических земель хорватского племени, но общепринятых доказательств этой теории не существует. В нынешнем дизайне добавлены пять коронующих щитов, которые символизируют исторические регионы, из которых возникла Хорватия. Красно-белая шахматная доска была символом хорватских королей, по крайней мере, с десятого века, ее размеры варьировались от 3×3 до 8×8, но чаще всего 5×5, как и нынешний герб. Старейшим источником, подтверждающим герб как официальный символ, является генеалогия Габсбургов, датируемая 1512–1518 гг. В 1525 году его использовали на вотивной медали. Самый старый известный образец шаховницы ( шаховницы на хорватском языке) в Хорватии можно найти на крыльях четырех соколов на купели, подаренной королем Хорватии Петром Крешимиром IV (1058–1074) архиепископу Сплита . [ нужна ссылка ]

В отличие от многих стран, в хорватском дизайне чаще используется символика герба, а не хорватского флага. Частично это связано с геометрическим дизайном щита, который делает его подходящим для использования во многих графических контекстах (например, эмблема Хорватских авиалиний или дизайн футболки сборной Хорватии по футболу ), а частично потому, что соседние страны, такие как Словения и Сербия использует на своих флагах те же панславянские цвета, что и Хорватия. Хорватское переплетение ( плетер или троплет ) также является широко используемым символом, который изначально происходит из монастырей, построенных между 9 и 12 веками. Переплетение можно увидеть на различных эмблемах, а также в современных хорватских воинских званиях и знаках различия званий хорватской полиции. [ нужна ссылка ]

Сообщества

[ редактировать ]В Хорватии ( национальное государство ) 3,9 миллиона человек идентифицируют себя как хорваты и составляют около 90,4% населения. Еще 553 000 человек проживают в Боснии и Герцеговине , где они являются одной из трех составляющих этнических групп , преимущественно проживающих в Западной Герцеговине , Центральной Боснии и боснийской Посавине . Меньшинство в Сербии насчитывает около 70 000 человек, в основном в Воеводине . [49] [50] где также подавляющее большинство шокчей считают себя хорватами, а также многие буневцы (последние, как и другие народности, заселили обширную заброшенную территорию после отступления Османской империи; эта хорватская подгруппа происходит с юга, в основном из региона Бачка ). Меньшие хорватские автохтонные меньшинства существуют в Словении (в основном в словенском Приморье , Прекмурье и в районе Метлики в регионах Нижней Крайны – 35 000 хорватов ), Черногории (в основном в Которском заливе – 6 800 хорватов ) и региональной общине в Косово под названием Яневчи , которая национально идентифицируются как хорваты. По переписи 1991 года хорваты составляли 19,8% от общей численности населения Югославии ; во всей стране проживало около 4,6 миллиона хорватов. [ нужна ссылка ]

Подгруппы хорватов обычно основаны на региональной принадлежности, например, далматинцы, славяне, загорцы, истрийцы и т. д., в то время как внутри и за пределами Хорватии существует несколько хорватских субэтнических групп: шокчи (Хорватия, Сербия, Венгрия), буневцы (Хорватия, Сербия). (Венгрия), бургенландские хорваты (Австрия), молизские хорваты (Италия), бокельи (Черногория), рачи (Венгрия), крашовани (Румыния) и яневцы (Косово).

Автохтонные сообщества

[ редактировать ]- Хорватия – национальное государство хорватов.

- В Боснии и Герцеговине хорваты являются одной из трех составляющих этнических групп , насчитывающих около 544 780 человек или 15,43% населения. В составе Федерации Боснии и Герцеговины проживает большинство (495 000 или чуть менее 90%) боснийских и герцеговинских хорватов .

- В Черногории , Которском заливе хорваты являются национальным меньшинством, насчитывающим 6021 человек или 0,97 % населения.

- В Сербии хорваты являются национальным меньшинством, насчитывающим 57 900 человек или 0,80 % населения. В основном они живут в регионе Воеводина , где хорватский язык является официальным (наряду с пятью другими языками), и в столице страны Белграде .

- В Словении не признаются меньшинством , хорваты насчитывая 35 642 человека или 1,81% населения. В основном они живут в словенском Приморье , Прекмурье и в районе Метлики в регионах Нижней Крайны .

Хорватские общины со статусом меньшинства

[ редактировать ]- В Австрии хорваты — этническое меньшинство, насчитывающее около 30 000 человек в Бургенланде ( Burgenland Croats ), восточной части Австрии, [172] и около 15 000 человек в столице Вене .

- В Чехии хорваты . являются национальным меньшинством, насчитывающим 850–2 000 человек, составляющих часть 29% меньшинства (как «Другие») крае В основном они живут в Моравском , в деревнях Евишовка , Добре Поле и Новый Пршеров .

- В Венгрии хорваты являются этническим меньшинством, насчитывающим 25 730 человек или 0,26% населения. [173]

- В Италии хорваты — языковое и этническое меньшинство, насчитывающее 23 880 человек, из которых 2 801 человек относятся к этническому меньшинству молизе хорваты из региона Молизе .

- В Румынии хорваты являются национальным меньшинством, насчитывающим 6786 человек. В основном они проживают в округе Караш-Северин , в коммунах Лупак (90,7 % ) и Карашова (78,28%).

- В Сербии хорваты Буневци (включая и Шокчи ) являются национальным меньшинством. В основном они проживают в многоэтнической автономной провинции Воеводина .

- В Словакии . хорваты являются этническим и национальным меньшинством, насчитывающим около 850 человек В основном они живут в окрестностях Братиславы , в деревнях Кровацкий Гроб , Чуново , Девинска Нова Вес , Русовце и Яровце .

Другие регионы с хорватскими меньшинствами

[ редактировать ]- В Болгарии существует небольшая хорватская община, ветвь яневцев , хорватов из Косово .

- В Новой Зеландии смешанный народ хорватов и маори Тарара имеет свою собственную культуру, традиции и обычаи и живет в Те Тай Токерау , самом северном регионе Новой Зеландии. 15 марта - День Тарары, посвященный их наследию.

- В Косово хорваты или Яневцы (Летничани), поскольку они населяли в основном город Яньево , до 1991 года насчитывали 8062 человека, но после войны многие бежали, и по состоянию на 2011 год [update] насчитывают всего 270 человек.

- В Северной Македонии хорваты насчитывают 2686 человек или 0,1% населения, в основном проживают в столице Скопье , городе Битола и вокруг Охридского озера .

Диаспора

[ редактировать ]Этот раздел нуждается в дополнительных цитатах для проверки . ( сентябрь 2018 г. ) |

насчитывается 4–4,5 миллиона хорватов В настоящее время в диаспоре по всему миру . Хорватская диаспора возникла по главным образом экономическим или политическим ( принуждение или изгнание) причинам:

- В другие европейские страны ( Словения , Италия , Австрия , Словакия , Германия , Венгрия ), вызванное завоеванием турок-османов , когда хорваты как католики подвергались притеснениям.

- В Америку (в основном в Канаду , Соединенные Штаты Америки , Чили и Аргентину , с небольшими общинами в Бразилии , Перу , Колумбии и Эквадоре ) в конце 19-го и начале 20-го века большое количество хорватов эмигрировало, главным образом, в экономических целях. причины.

- В Новую Зеландию, преимущественно в регион Нортленд , для работы на каури . плантациях [12]

- Дальнейшая, более крупная волна эмиграции, на этот раз по политическим причинам, произошла после окончания Второй мировой войны в Югославии . В это время как пособники режима усташей , так и те, кто не хотел жить при коммунистическом бежали из страны в Америку и Океанию . режиме, снова

- В качестве рабочих-иммигрантов, особенно в Германии, Австрии и Швейцарии в 1960-х и 1970-х годах. Кроме того, часть эмигрантов уехала по политическим мотивам. Эта миграция позволила коммунистической Югославии снизить уровень безработицы, и в то же время деньги, отправленные эмигрантами домой своим семьям, стали огромным источником валютных доходов.

- Последняя крупная волна хорватской эмиграции произошла во время и после югославских войн (1991–1995). В результате выросли сообщества мигрантов, уже обосновавшиеся в Америке, Океании и по всей Европе.

Подсчет диаспоры является приблизительным из-за неполных статистических данных и натурализации . За рубежом в США проживает самая большая группа хорватских эмигрантов (414 714 человек по переписи 2010 года), в основном в Огайо , Пенсильвании , Иллинойсе и Калифорнии , со значительной общиной на Аляске , за которой следует Австралия (133 268 человек по переписи 2016 года, с концентрацией в Сиднее , Мельбурне и Перте ) и Канаде (133 965 по переписи 2016 года, преимущественно в Южном Онтарио , Британской Колумбии и Альберте ).

По различным оценкам, общее количество американцев и канадцев, имеющих хотя бы частичное хорватское происхождение, составляет 2 миллиона человек, многие из которых не идентифицируют себя как таковые в переписях стран. [39] [40] [41] [42] [43] [174] [45] [175]

Хорваты также несколькими волнами эмигрировали в Южную Америку: в основном в Чили , Аргентину и Бразилию ; оценки их числа сильно различаются: от 150 000 до 500 000. [176] [177] Оба президента Чили ( Габриэль Борич ) и Аргентины ( Хавьер Милей ) имеют хорватское происхождение. [178] [179]

Есть также меньшие группы потомков хорватов в Бразилии, Эквадоре , Перу , Южной Африке, Мексике и Южной Корее. Важнейшими организациями хорватской диаспоры являются Хорватский братский союз , Фонд хорватского наследия и Всемирный хорватский конгресс.

Карты

[ редактировать ]- Хорваты в Хорватии

- Хорваты в Боснии и Герцеговине в 2013 году

- Хорваты в Воеводине, Сербия

- Хорваты в Румынии

Историография

[ редактировать ]См. также

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Беллами, Алекс Дж. (2003). Формирование хорватской национальной идентичности: многовековая мечта . Манчестер, Англия: Издательство Манчестерского университета. п. 116. ИСБН 978-0-71906-502-6 . Архивировано из оригинала 27 сентября 2023 года . Проверено 12 июля 2020 г.

- ^ «2. Население по национальностям, по городам/муниципалитетам» . Перепись населения, домохозяйств и жилищ 2011 года . Загреб: Статистическое бюро Хорватии . Декабрь 2012 года . Проверено 26 марта 2013 г.

- ^ Сараево, июнь 2016 г. Перепись населения, домохозяйств и жилищ в Боснии и Герцеговине, окончательные результаты 2013 г. (PDF) . БХАС. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 24 декабря 2017 года . Проверено 30 июня 2016 г.

- ^ Результаты American Fact Finder (Бюро переписи населения США)

- ↑ Хорватская диаспора в США. Архивировано 7 мая 2021 года в Wayback Machine . «По оценкам, в США проживает около 1 200 000 хорватов и их потомков».

- ↑ Федеральное статистическое управление Германии. Архивировано 5 июля 2006 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ «Государственное управление по делам хорватов за рубежом» . Hrvatiizvanrh.hr. Архивировано из оригинала 30 сентября 2018 года . Проверено 18 марта 2015 г.

- ^ Хорватская диаспора. Архивировано 9 мая 2016 года в Wayback Machine. По оценкам Министерства иностранных дел Республики Чили, в этой стране в настоящее время проживают 380 000 человек хорватского происхождения, что составляет 2,4% от общей численности населения Чили.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д «Статус хорватских иммигрантов и их потомков за рубежом» . Республика Хорватия: Государственное управление по делам хорватов за рубежом. Архивировано из оригинала 13 февраля 2019 года . Проверено 20 июля 2013 г.

- ^ «Люди в Австралии, родившиеся в Хорватии» . Австралийское статистическое бюро . Содружество Австралии. 2021. сек. «Культурное разнообразие» . Проверено 23 июня 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Население по национальным и/или этническим группам, полу и городскому/сельскому месту жительства» . Проверено 17 июня 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Картер: Новая Зеландия празднует 150-летие киви-хорватской культуры» . voxy.co.nz. Архивировано из оригинала 31 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 29 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Цифры за 2006 год. Публикация.Документ.88215.pdf» (PDF) . п. 68. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 24 июня 2008 г. Примечание: Petra-P12 дает номер 40 484. по состоянию на 2004 г. Архивировано 11 января 2012 г. на Wayback Machine. Страница 12 2.1.1. Численность постоянного иностранного населения по национальностям в 2001–2004 годах составляет 44 035 человек.

- ^ «Хорватская диаспора в Италии» . Центральное государственное управление по делам хорватов за пределами Республики Хорватия. Архивировано из оригинала 5 июля 2020 года . Проверено 25 января 2020 г.

- ^ «Статистики Урада РС – Попис 2002 г.» . Архивировано из оригинала 6 августа 2011 года . Проверено 18 марта 2015 г.

- ^ «Текущая ситуация и прогнозы будущего развития населения хорватского происхождения в Парагвае» (PDF) . imin.hr . Январь 2023 г. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 3 февраля 2023 г. Проверено 30 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ «Презентация Хорватии» (на французском языке). Министерство иностранных дел и международного развития . Архивировано из оригинала 30 июня 2016 года . Проверено 28 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Перепись населения, домохозяйств и квартир 2011 года в Республике Сербия» (PDF) . Webrzs.stat.gov.rs . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 8 июля 2018 года . Проверено 12 декабря 2017 г.

- ^ «Хорватская эмиграция в Швеции» . Hrvatiizvanrh.hr (на хорватском языке). Архивировано из оригинала 20 февраля 2019 года . Проверено 18 марта 2015 г.

- ^ Вукович, Габриэлла (2018). Микроперепись 2016 г. – 12. Этнические данные [Микроперепись 2016 г. – 12. Этнические данные] (PDF) . Центральное статистическое управление Венгрии (Отчет) (на венгерском языке). Будапешт. ISBN 978-963-235-542-9 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 8 августа 2019 года . Проверено 9 января 2019 г.

- ^ Гнидич Крнич, Лидия (25 февраля 2019 г.). «Авторитетный эксперт раскрыл точное количество хорватов, отправившихся в Ирландию: «Я также знаю, почему это число падает» » . Утренняя газета (на хорватском языке) . Проверено 4 сентября 2021 г.

- ^ «Государственное управление по делам хорватов за рубежом» . Hrvatiizvanrh.hr . Архивировано из оригинала 20 февраля 2019 года . Проверено 18 марта 2015 г.

- ^ «Веза с Хрватима изван Хрватске» . Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2007 года . Проверено 18 марта 2015 г.

- ^ «Дом и свиджет — Номер 227 — Хорватский клуб в ЮАР» . Архивировано из оригинала 28 марта 2017 года . Проверено 18 марта 2015 г.

- ^ «Набор данных ОЭСР» . Архивировано из оригинала 4 мая 2011 года . Проверено 20 сентября 2008 г.

- ^ Черногорская перепись [ мертвая ссылка ] стр. 14 Население по национальной или этнической принадлежности – Обзор Республики Черногория и муниципалитетов

- ^ «Республика Хорватия» . Канчиллерия . 26 сентября 2013 года. Архивировано из оригинала 22 декабря 2014 года . Проверено 20 февраля 2015 г.

- ^ Проект Джошуа. «Страна – Дания: Проект Джошуа» . Архивировано из оригинала 2 ноября 2013 года . Проверено 18 марта 2015 г.

- ^ «Население по категориям иммигрантов и стране происхождения» . Статистическое управление Норвегии. 1 января 2015 г. Архивировано из оригинала 15 июля 2018 г. Проверено 18 марта 2015 г.

- ^ «Государственное управление по делам хорватов за рубежом» . Hrvatiizvanrh.hr . Архивировано из оригинала 1 февраля 2019 года . Проверено 18 марта 2015 г.

- ^ «SODB2021 – Население – Базовые результаты» . scitanie.sk Архивировано из оригинала 31 мая 2022 года . Проверено 25 августа 2022 г.

- ^ «SODB2021 – Население – Базовые результаты» . scitanie.sk Архивировано из оригинала 15 июля 2022 года . Проверено 25 августа 2022 г.

- ^ «Из жизни хорватских верующих за пределами Хорватии» . Архивировано из оригинала 27 октября 2005 года.

- ^ «Хорваты Чехии: этнический профиль народа» . czso.cz. Чешское статистическое управление . Архивировано из оригинала 9 марта 2021 года . Проверено 17 апреля 2017 г.

- ^ «Сефстат» (PDF) . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 20 марта 2022 года . Проверено 13 февраля 2022 г.

- ^ Всероссийская перепись населения 2010. Национальный состав населения Archived 6 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ Марти, Мартин Э. (1997). Религия, этническая принадлежность и самоидентификация: нации в смятении . Университетское издательство Новой Англии. ISBN 0-87451-815-6 .

[...] три этнорелигиозные группы, сыгравшие роль главных героев кровавой трагедии, развернувшейся в бывшей Югославии: православные сербы, хорваты-католики и славяне-мусульмане Боснии.

- ^ «Этнолог – южнославянские языки» . ethnologue.com. Архивировано из оригинала 25 декабря 2018 года . Проверено 8 февраля 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фаркас, Эвелин (2003). Расколотые государства и внешняя политика США. Ирак, Эфиопия и Босния в 1990-е годы . Пэлгрейв Макмиллан США. п. 99.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пакуин, Джонатан (2010). Сила, стремящаяся к стабильности: внешняя политика США и сепаратистские конфликты . Издательство Университета Макгилла-Куина. п. 68.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Справочник исторических организаций в США и Канаде . Американская ассоциация государственной и местной истории. 2002. с. 205.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Зангер, Марк (2001). Американская этническая кулинарная книга для студентов . Гринвуд. п. 80.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Левинсон, Эмбер; Дэвид, Мелвин (1997). Культуры американских иммигрантов: строители нации . Макмиллан. п. 191 .

- ^ Зарубежные операции, финансирование экспорта и соответствующие программы Ассигнования на 1994 год: Свидетельства членов Конгресса и других заинтересованных лиц и организаций . Соединенные Штаты. Конгресс. Дом. Комитет по ассигнованиям. Подкомитет по зарубежным операциям, экспортному финансированию и смежным программам. 1993. с. 690.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Национальный генеалогический исследователь . Янлен Энтерпрайзис. 1979. с. 47.

- ^ «Хорват» . Lexico Британский словарь английского языка . Издательство Оксфордского университета . Архивировано из оригинала 2 декабря 2020 года.

- ^ Дафна Винланд (2004), «Хорватская диаспора», в Мелвине Эмбере; Кэрол Р. Эмбер; Ян Скоггард (ред.), Энциклопедия диаспор: культуры иммигрантов и беженцев во всем мире. Том I: Обзоры и темы; Том II: Сообщества диаспоры , том. 2 (иллюстрированное издание), Springer , с. 76, ISBN 978-0-306-48321-9 , заархивировано из оригинала 27 сентября 2023 г. , получено 29 октября 2015 г. По

оценкам, 4,5 миллиона хорватов живут за пределами Хорватии (...)

- ^ «О нас – Хорватский Всемирный Конгресс» . 15 октября 2007 года. Архивировано из оригинала 15 октября 2007 года . Проверено 12 декабря 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Правительство Автономного края Воеводина. Архивировано 29 ноября 2014 года на Wayback Machine.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Республики Завод за Статистику – Республика Сербия» . Архивировано из оригинала 22 апреля 2009 года.

- ^ «Хорватский :: Нгати Тарара 'Олива и Каури' » . croatianclub.org . Архивировано из оригинала 29 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 29 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Капители, Мария; Таонга, Министерство культуры и наследия Новой Зеландии Те Манату. «День Тарары» . Teara.govt.nz . Архивировано из оригинала 29 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 29 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Европейская комиссия – Часто задаваемые вопросы о языках в Европе» . europa.eu . Архивировано из оригинала 16 декабря 2020 года . Проверено 6 августа 2019 г.

- ^ «О БиГ» . Бхасба . Агентство статистики Боснии и Герцеговины. Архивировано из оригинала 11 июля 2012 года . Проверено 7 августа 2019 г.

- ^ Глухак, Алемко (1993). Хорватский этимологический словарь ( на хорватском языке). Август Цезарек. ISBN 953-162-000-8 .

- ^ Матасович, Ранко (2019), «Ime Hrvata» [Имя хорватов], Jezik (Хорватское филологическое общество) (на хорватском языке), 66 (3), Загреб: 81–97, заархивировано из оригинала 12 декабря 2022 г. , извлечено. 4 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ Fine 1991 , стр. 26–41.

- ^ Белошевич, Янко (2000). «Развитие и основные характеристики старых хорватских кладбищ горизонта VII-IX веков в исторических областях хорватов» . Документы (на хорватском языке). 39 (26): 71–97. дои : 10.15291/radovipov.2231 . Архивировано из оригинала 26 марта 2023 года . Проверено 3 июля 2022 г.

- ^ Фабиянич, Томислав (2013). «Дата 14 века из раннехристианской базилики Гемина в Подвршье (Хорватия) в контексте славянского поселения на восточном побережье Адриатического моря». Раннее славянское заселение Центральной Европы в свете новых датировок . Вроцлав: Институт археологии и этнологии Польской академии наук. стр. 251–260. ISBN 978-83-63760-10-6 .

- ^ Бекич, Лука (2012). «Керамика пражского типа в Хорватии» . Дни Степана Гунячи 2, Материалы научной конференции «Дни Степана Гунячи 2»: Хорватское средневековое историческое и археологическое наследие, Международные темы . Сплит: Музей хорватских археологических памятников. стр. 21–35. ISBN 978-953-6803-36-1 .

- ^ Бекич, Лука (2016). Раннее средневековье между Паннонией и Адриатикой: раннеславянская керамика и другие археологические находки с шестого по восьмой век [ Раннее средневековье между Паннонией и Адриатикой: раннеславянская керамика и другие археологические находки с шестого по восьмой век ] (на хорватском и английском языках) . Пула: Археологический музей Истрии. стр. 101, 119, 123, 138–140, 157–162, 173–174, 177–179. ISBN 978-953-8082-01-6 .

- ^ Билогривич, Горан (2018). «Урны, славяне и хорваты. О погребениях и переселении в VII веке» . Зб. Департамента Известный. Институт Чувак. Известный. Хорват. акад. Известный. Искусство. (на хорватском языке). 36 : 1–17. дои : 10.21857/ydkx2crd19 . S2CID 189548041 . Архивировано из оригинала 12 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 3 июля 2022 г.

- ^ Зуб (2010 , стр. 175)

- ^ Борри (2011 , стр. 215)

- ^ Короткометражка (2006 , стр. 138)

- ^ Зуб (2010 , стр. 20)

- ^ Будак, Невен (2008). «Идентичность в раннесредневековой Далмации (7 – 11 вв.)». У Ильдара Гарипзанова; Патрик Дж. Гири ; Пшемыслав Урбанчик (ред.). Франки, северяне и славяне: идентичности и государственное формирование в Европе раннего средневековья . Тюрнхаут: Бреполи. стр. 223–241. ISBN 9782503526157 . Архивировано из оригинала 10 августа 2023 года . Проверено 13 июля 2022 г.

- ^ Зуб (2010 , стр. 186)

- ^ Вольфрам (2002) Людевит считается первым хорватским принцем. Константин Багрянородный владеет Далмацией и частью Славонии, населенной хорватами. Но этот автор написал более чем через сто лет после франкских королевских анналов, в которых ни разу не упоминается имя хорватов, хотя в тексте упоминается очень много славянских племенных названий. Поэтому, если применить методы этногенетической интерпретации, хорватский Людевит представляется анахронизмом.

- ^ Дворник, Ф.; Дженкинс, RJH; Льюис, Б.; Моравчик, Ги; Оболенский, Д.; Рансиман, С. (1962). ПиДжей Дженкинс (ред.). Де Администрандо Империо: Том II. Комментарий . Лондонский университет: The Athlone Press. стр. 139, 142. Архивировано из оригинала 27 сентября 2023 года . Проверено 13 июля 2022 г.

- ^ Короткий 2006 , с. 210.

- ^ Будак, Невен (1994). Первые века Хорватии (PDF) . Загреб: Издательство Хорватского университета. стр. 58–61. ISBN 953-169-032-4 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 4 мая 2019 года . Проверено 13 июля 2022 г.

- ^ Грачанин, Хрвое (2008), «Часть хорватов, прибывших в Далмацию, отделилась и управляла Иллирикой и Паннонией: дискуссии с DAI ок. 30, 75-78» , Povijest U Nastavi (на хорватском языке), VI (11): 67 –76, заархивировано из оригинала 19 декабря 2022 г. , получено 13 июля 2022 г.

- ^ Будак (2018 , стр. 51, 111, 177, 181–182)

- ^ Живкович, Тибор (2006). Портреты сербских правителей (IX-XII вв.) . Белград: Институт учебников. стр. 60–61. ISBN 86-17-13754-1 .

- ^ Живкович, Тибор (2012). «Арентани – пример проверки личности в раннем средневековье» [Арентани – пример проверки личности в раннем средневековье]. Исторический журнал . 61 : 12–13.

- ^ Dvornik 1962 , p. 139, 142.

- ^ Файн 1991 , с. 37, 57.

- ^ Хизер, Питер (2010). Империи и варвары: падение Рима и рождение Европы . Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 404–408, 424–425, 444. ISBN. 978-0-19-974163-2 .

- ^ Дворник 1962 , с. 138–139:Даже если мы отвергнем теорию Грубера, поддержанную Манойловичем (там же, XLIX), о том, что Захлумье фактически стало частью Хорватии, следует подчеркнуть, что захлумцы имели более тесную связь интересов с хорватами, чем с сербами. , так как они, кажется, переселились на свой новый дом не, как говорит Ц. (33/8-9), с сербами, а с хорватами; см. ниже, 18/33-19... Эта поправка проливает новый свет на происхождение династии Захлумиев и самих Захлуми. Сказанное им о стране предков Михаила информатор Ц. заимствовал из местного источника, вероятно, от члена княжеского рода; и информация достоверна. Если это так, то мы должны считать династию Захлумье и, во всяком случае, часть ее народа ни хорватами, ни сербами. Более вероятным кажется, что предок Михаила вместе со своим племенем присоединился к хорватам, когда они двинулись на юг; и поселились на побережье Адриатического моря и Наренты, предоставив хорватам возможность продвинуться в собственно Далмацию. Это правда, что в нашем тексте говорится, что Захлуми «были сербами со времен того князя, который претендовал на защиту императора Ираклия» (33/9-10); но там не сказано, что семья Михаила была сербами, а только то, что они «происходили из некрещеных, живущих на реке Висле, и называются (читая Лицики) «поляками». Собственная враждебность Михаила к Сербии (ср. 32/86-90) позволяет предположить, что его семья на самом деле не была сербской; и что сербы имели прямой контроль только над Требине (см. 32/30). Таким образом, общее утверждение К. о том, что захлумцы были сербами, неверно; и действительно, его более поздние заявления о том, что тербуниоты (34/4–5) и даже нарентанцы (36/5–7) были сербами и пришли вместе с сербами, по-видимому, противоречат тому, что он сказал ранее (32/18–7). 20) о сербской миграции, которая достигла новой Сербии со стороны Белграда. Он, вероятно, видел, что в его время все эти племена находились в сфере сербского влияния, и поэтому называл их сербами, тем самым на три столетия предшествуя положению дел в его дни. Но на самом деле, как было показано на примере захлумцев, эти племена не были собственно сербами и, по-видимому, мигрировали не с сербами, а с хорватами. Сербам уже на раннем этапе удалось распространить свою власть на тербуниотов, а при князе Петре - на короткое время на нарентян (см. 32/67). Диоклины, которых Ц. не называет сербами, находились слишком близко к византийской феме Диррахион, чтобы сербы могли попытаться их покорить до времен Ц.

- ^ Дворник, Фрэнсис (1970). Византийские миссии среди славян: СС. Константин-Кирилл и Мефодий . Нью-Брансуик, Нью-Джерси: Издательство Университета Рутгерса. п. 26. ISBN 9780813506135 . Архивировано из оригинала 27 сентября 2023 года . Проверено 21 июля 2022 г.