White Croats

The White Croats (Croatian: Bijeli Hrvati; Polish: Biali Chorwaci; Czech: Bílí Chorvati; Ukrainian: Білі хорвати, romanized: Bili khorvaty), also known simply as Croats, were a group of Early Slavic tribes that lived between East Slavic and West Slavic tribes in the historical region of Galicia north of the Carpathian Mountains (in modern Western Ukraine and Southeastern-Southern Poland), and possibly in Northeastern Bohemia.

Debates continue over the origin of the Croats and related topics. Their ethnonym is usually considered to be of Iranian origin, and historians regard them one of the oldest Slavic tribes or tribal alliances that formed prior to the 6th century CE. They were an East Slavic tribe, but bordered both East Slavic groups (Dulebes and their related Buzhans and Volhynians, Tivertsi, and Ulichs) in Western Ukraine; and West Slavic tribes (Lendians and Vistulans) in southeastern Poland, controlling an important trade route from East to Central Europe. Archaeologically the Croats were mostly related to the Korchak and Luka-Raikovets cultures identified with the Sclaveni (while their connection to the Antes and to the Penkovka culture remains a matter of dispute). Their area is characterized by use of stone defenses, tiled tombs (and kurgan-like tombs), stone ovens, and many large, fortified settlements and cult buildings. They practiced Slavic paganism. Foreign medieval authors documented the Croats in historical sources and legends, and had their own origo gentis.

In the late-6th and early-7th centuries, some of the Croats migrated from their homeland, White or Great Croatia in the Carpathians, to the Roman province of Dalmatia (in present-day Croatia along the Adriatic Sea), becoming ancestors of the modern South Slavic Croats. They probably were among the Slavs who with the Pannonian Avars plundered the Roman provinces, but when settled they revolted against the Avars and soon started accepting Christianity during the time of Porga (fl. c. 7th century), the first known archon of the Duchy of Croatia. Other Croats who stayed in their Carpathian homeland continued to practise paganism and formed a tribal proto-state with the polis-like gords of Plisnesk, Stilsko, Revno, Halych, Terebovlia (among other) in Western Ukraine, which lasted until the very end of the 10th century. They were pressured and influenced by more centralized polities: Great Moravia, the Duchy of Bohemia, the Duchy of Poland, Kievan Rus' and the Principality of Hungary. After their defeat by Kievan Rus', on their territory were organized East Slavic principalities of Peremyshl, Terebovlia, Zvenyhorod and finally the Principality of Halych.

According to some modern sources, the ethnic name of White Croats was possibly preserved in parts of Western Ukraine and Southern Poland until the 19th and early-20th centuries. Historians see them northern White Croats as having become assimilated into the Ukrainian, Polish and Czech nationalities, and to have been precursors of the Rusyns.

Etymology

[edit]

It is generally believed that the Croatian ethnonym – Hrvat, Horvat and Harvat – etymologically is not of Slavic origin, but a borrowing from Iranian languages.[1][2][3][4][5][6] According to the most plausible theory by Max Vasmer, it derives from *(fšu-)haurvatā- (cattle guardian),[7][8][9][10][11] more correctly Proto-Ossetian / Alanian *xurvæt- or *xurvāt-, in the meaning of "one who guards" ("guardian, protector").[12]

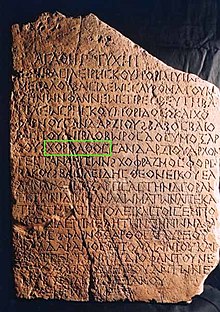

It is considered that the ethnonym is first attested in anthroponyms Horoúathos, Horoáthos, and Horóathos on the two Tanais Tablets, found in the Greek colony of Tanais at the shores of Sea of Azov in the late 2nd and early 3rd century AD, at the time when the colony was surrounded by Iranian speaking Sarmatians.[13] However, acceptance of any non-Slavic etymology is problematic because it implies an ethnogenesis relationship with the specific ethnic group.[14] There is no mention of an Iranian tribe named as Horoat in the historical sources, but it was not uncommon for Slavic tribes to get their tribal names from anthroponyms of their forefathers and chiefs of the tribe, like in the case of Czechs, Dulebes, Radimichs, and Vyatichi.[15]

Any mention of the Croats before the 9th century is uncertain, and there were several loose attempts at tracing; Struhates, Auhates, and Krobyzoi by Herodotus,[16] Horites by Orosius in 418 AD,[16][17] and the Harus (original form Hrws,[18] some read Hrwts;[19] Hros, Hrus) at the Sea of Azov, near the mythical Amazons,[20] mentioned by Zacharias Rhetor in 550 AD.[16][18] The Hros some relate to the ethnonym of the Rus' people.[18][21] The distribution of the Croatian ethnonym in the form of toponyms in later centuries is considered to be hardly accidental because it is related with Slavic migrations to Central and South Europe.[22]

The epithet "white" for the Croats and their homeland is usually related to the use of colors for cardinal directions among Eurasian people.[23] That is, it meant "Western Croats",[4][24] or "Northern Croats",[25] in comparison to Eastern Carpathian lands where they lived before.[26][27] The epithet "great" (megali) probably was not just an association with size as could signify an "old, ancient" or "former" homeland,[28][29] for the White Croats and Croats when they were new arrivals in the Roman province of Dalmatia.[26][30][31][32] In semantical comparison, as the color "white" besides the meaning "Western" of something/someone could also mean "younger" (later also associated with "unbaptized"[33]), the association with "great" is contradictory.[34] The ethnonym with the epithet was also questioned lexically and grammatically by linguists like Petar Skok, Stanisław Rospond, Jerzy Nalepa and Heinrich Kunstmann, who argued that the Byzantines did not differentiate Slavic "bělъ-" (white) from "velъ-" (big, great), and because of common Greek betacism, the "Belohrobatoi" should be read as "Velohrobatoi" ("Velohrovatoi"; "Great/Old Croats" not "White Croats").[35] The possible confusion could have happened if the original Slavic form "velo-" was transcribed to Greek alphabet and then erroneously translated, but such a conclusion is not always accepted.[36]

Although the early medieval Croatian tribes in the scholarship are often called as White Croats, there's a scholarly dispute whether it is a correct term as some scholars differentiate the tribes according to separate regions and that the term implies only the medieval Croats who lived in Central Europe.[37][38][39][40]

Origin

[edit]Some scholars etymologically, and archaeologically due to burial mounds, drew parallels between Carpathian Croats and Slavs with the Carpi, who previously lived in the territory of Carpathian Mountains,[41][42][43][44] but such theory was never taken seriously.[45] Another more common theorization is related to the first Iranian tribes who lived on the shores of the Sea of Azov, Scythians, who arrived there c. 7th century BCE.[46] Around the 6th century BCE, the Sarmatians began their migration westwards, gradually subordinating the Scythians by the 2nd-century BCE.[47] During this period there was substantial cultural and linguistic contact between the Early Slavs and Iranians,[48][49] and in this environment were formed the Antes.[50] Antes were Slavic people who lived in that area and to the West between Dniester and Dnieper from the 4th until the 7th century.[51][52] Some think that the Croats were part of the Antes tribal polity who migrated to Galicia in the 3rd–4th century, under pressure by invading Huns and Goths.[53][54][55] Others related them to the early Sclaveni or saw them as a mixture of both Antes and Sclaveni.[56] Some argue that they lived in the Carpathians until the Antes were attacked by the Pannonian Avars in 560, and the polity was finally destroyed in 602 by the same Avars.[57][58] The early Croats' migration to Dalmatia, with Pannonian Avars in the 6th century or during the reign of Heraclius (610–641), some see as a possible continuation of the previous conflict and contacts between the Antes and Avars.[59][58]

In a similar fashion, regardless of Iranian or Slavic etymology of their name, Henryk Łowmiański argued that the tribe was formed by the end of the 3rd and not later than the 5th century in Lesser Poland,[60] during the peak of the Huns and their leader Attila, but such localization is historiographically and archaeologically unproven and could only have been in Prykarpattia (Western Ukraine).[61] They probably formed around late 4th and first half of the 5th century.[62] It is considered that they probably were one of oldest and largest Slavic tribal formations until 6th century.[63][64]

Some argue that the large Proto-Slavic tribe or tribal alliance,[22][65] separated somewhere between 7th and 10th century.[66][67] The activity of the Avars is argued to have resulted with assumed breaking of the tribal group into Carpathian (Prykarpattia and Zakarpattia in Western Ukraine), Western or White (the Upper Vistula river in Lesser Poland, Silesia, Prešov Region in Eastern Slovakia, and Northeastern Czech Republic), and Southern (in the Balkans).[68][69] It is considered that the Croatian tribes from Prykarpattia and Zakarpattia in Ukraine were related to the Croatian tribes from Poland-Bohemia.[68][70] However, the same ethnic name does not necessarily mean all the tribes had the same ancestry, as well the dating and supposed existence, separation and location of different tribal groups is a matter of much debate due to lack of evidence, historical sources and their interpretation.[71][72][73]

There is a dispute among Slavic scholars as to whether the Croats were of Irani-Alanic, East Slavic, or West Slavic origin.[74][75][76][77] Whether the early Croats were Slavs who had taken a name of Iranian origin, or whether they were ruled by a Sarmatian elite and were Slavicized Sarmatians, cannot be resolved, but is considered that they arrived as Slavic people when entered the Balkans. The possibility of Irani-Sarmatian elements among, or influences upon, early Croatian ethnogenesis cannot be entirely excluded,[78][2][79][80][81][82] but most probably was negligible by the Early Middle Ages.[83] The dispute on affiliation with West and East Slavs is also disputed on linguistic grounds because the Croats are linguistically closer to East Slavs.[67][84][85][86][87]

History

[edit]Middle Ages

[edit]

Nestor the Chronicler in his Primary Chronicle (12th century), which information and convoluted viewpoint were often compiled and influenced by use of various sources of different origin,[88] mentions the White Croats, calling them Horvate Belii or Hrovate Belii, the name depending upon which manuscript of his is referred to:

"Over a long period the Slavs settled beside the Danube, where the Hungarian and Bulgarian lands now lie. From among these Slavs, parties scattered throughout the country and were known by appropriate names, according to the places where they settled. Thus some came and settled by the river Morava, and were named Moravians, while others were called Czechs. Among these same Slavs are included the White Croats, the Serbs, and the Carinthians. For when the Vlakhs (Romans) attacked the Danubian Slavs, settled among them, and did them violence, the latter came and made their homes by the Vistula, and were then called Lyakhs. Of these same Lyakhs some were called Polyanians, some Lutichians, some Mazovians, and still others Pomorians".[89]

Most what is known about the early history of White Croats comes from the work by the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII, De Administrando Imperio (10th century).[90] In the 30th chapter, "The Story of the Province of Dalmatia" Constantine wrote:

"The Croats at that time were dwelling beyond Bagibareia, where the Belocroats are now. From them split off a family, namely of five brothers, Kloukas and Lobelos and Kosentzis and Mouchlo and Chrobatos, and two sisters, Touga and Bouga, who came with their folk to Dalmatia and found this land under the rule of the Avars. After they had fought one another for some years, the Croats prevailed and killed some of the Avars and the remainder they compelled to be subject to them... The rest of the Croats stayed over near Francia, and are now called the Belocroats, that is, the White Croats, and have their own archon; they are subject to Otto, the great king of Francia, which is also Saxony, and are unbaptized, and intermarry and are friendly with the Turks. From the Croats who came to Dalmatia, a part split off and took rule of Illyricum and Pannonia. They too had an independent archon, who would maintain friendly contact, though through envoys only, with the archon of Croatia... From that time they remained independent and autonomous, and they requested holy baptism from Rome, and bishops were sent and baptized them in the time of their Archon Porinos".[91]

In the previous 13th chapter which described the Hungarian neighbors Franks to the West, Pechenegs to the North, and Moravians to the South, it is also mentioned that "on the other side of the mountains, the Croats are neighboring the Turks", however as are mentioned Pechenegs to the North while in the 10th century the Croats are mentioned as the Southern neighbors of the Hungarians, the account is of uncertain meaning,[92] but most probably referring to Croats living "on the other side" of Carpathian Mountains.[93] It is considered that the described 7th century homeland and migration's starting point is anachronistic based on partly available information about contemporary 10th century White Croats,[94][95][96] and the 6-7th century existence and location of White Croats and Croatia to the West of the Eastern Carpathians or Carpathian Mountains was never proved.[97] It is considered that Constantine VII was referring to the 10th century Duchy of Bohemia which controlled parts of Southern Poland and Western Ukraine.[98][95][99][100] From the 30th chapter can be observed that the Croats lived "beyond Bavaria" in the sense East of it, in Bohemia and Lesser Poland, because the original source of information was of Western Roman origin.[101][102] White Croatia in the 7th century could not border Francia,[103] and Frankish sources do not mention and know anything about the Croats implying they must have lived much further to the East.[104]

They could have been the neighbors of the Franks as early as 846 or 869 when Duchy of Bohemia was under the control of Eastern Francia. Otto I ruled the Moravians only from 950, and the White Croats were also part of the Moravian state, at least from 929.[103] György Györffy argued that the White Croats were allies of the Hungarians (Turks),[105] but "neither in 929 nor in 950 could be Bohemia described as being in good relations with Hungary", as part of White Croatia was in the realm of Bohemia, and friendly relations between Bohemia and Magyars were established after 955.[106] White Croats since 906 or 955 possibly were in friendly and matrimonial relations with the Árpád dynasty.[107] A similar story to the 30th chapter is mentioned in the work by Thomas the Archdeacon, Historia Salonitana (13th century), where he recounts how seven or eight tribes of nobles, who he called Lingones, arrived from Poland and settled in Croatia under Totila's leadership.[108] According to the Archdeacon, they were called Goths, but also Slavs, depending on the names brought by those who came from Polish and Bohemian lands.[109] Some scholars consider Lingones to be a distortion of the name for the Polish tribe of Lendians.[110] The reliability to the claim adds the recorded oral tradition of Michael of Zahumlje from DAI that his family originates from the unbaptized inhabitants of the river Vistula called as Litziki,[111] identified with Widukind's Licicaviki, also referring to the Lendians (Lyakhs).[112][113] According to Tibor Živković, the area of the Vistula where the ancestors of Michael of Zahumlje originate was the place where White Croats would be expected.[114] In the 31st chapter, "Of the Croats and of the Country They Now Dwell in" Constantine wrote:

"(It should be known) that the Croats who now live in the regions of Dalmatia are descended from the unbaptized Croats, also called the "white", who live beyond Turkey and next to Francia, and they border the Slavs, the unbaptized Serbs... These same Croats arrived as refugees to the emperor of the Romaioi Heraclius before the Serbs came as refugees to the same Emperor Heraclius, at that time when the Avars had fought and expelled from those parts the Romani... Now, by the command of the Emperor Heraclius, these same Croats fought and expelled the Avars from those parts, and, by mandate of Heraclius the emperor they settled down in that same country of the Avars, where they now dwell. These same Croats had the father of Porga for their archon at that time... (It should be known) that ancient Croatia, also called "white", is still unbaptized to this day, as are also its neighboring Serbs. They muster fewer horsemen as well as fewer foot than baptized Croatia, because they are constantly plundered by the Franks and Turks and Pechenegs. Nor do they have either sagēnai or kondourai or merchant ships, because they live far away from sea; it takes 30 days of travel from the place where they live to the sea. The sea to which they come down to after 30 days, is that which is called dark".[115]

According to the 31st chapter, the Pechenegs were Eastern neighbors of the White Croats, those living around Upper Dniester in Western Ukraine, in the second half of the 9th century and early 10th century.[116][117][118] In that time Franks and Hungarians plundered Moravia, and White or Great Croatia was probably part of the Great Moravia.[116][117] It is notable that in both chapters they are noted to be "unbaptized" Pagans, a description only additionally used for the Moravians and White Serbs. Such an information probably came from an Eastern source because particular religious affiliation was of interest to the Khazars as well as to Arabian historians and explorers who carefully recorded them.[119] Some scholars believe this is a reference to the Baltic Sea,[116] however, more probable is a reference to the Black Sea because in DAI there's no reference to the Baltic Sea, the chapter has information usually found in 10th century Arabian sources like of Al-Masudi, the Black Sea was of more interest to the Eastern merchants and Byzantine Empire, and its Persian name "Dark Sea" (axšaēna-) was already well known.[120][121]

Alfred the Great in his Geography of Europe (888–893) relying on Orosius, recorded that, "These Moravians have, to the west of them, the Thuringians, and Bohemians, and part of the Bavarians ... to the east of the country Moravia, is country of the Wisle, and to the east of them are the Dacians, who were formerly Goths. To the north-east of the Moravians are the Dalamensan, and to the east of the Dalamensan are the Horithi, and to the north of the Dalamensan are the Surpe, and to the west of them are the Sysele. To the north of the Horithi is Mægtha-land, and north of the Mægtha-land are the Sermende even to the Rhipæan mountains".[122][123][124][125] According to Richard Ekblom, Gerard Labuda, and Łowmiański the issue with positioning in the work is present for Scandinavia while the data is accurate for the continent.[126] Some scholars correct the north-east position of Dalamensan to north-west.[127] Sysele are the Siusler-Susłowie, one of the Sorbian tribes.[128] The location of Croats is usually interpreted to be East of Czechia around river Eastern Neisse or Upper Vistula in Poland, or possibly around Elbe in Czechia.[129][130] Their location does not necessarily mean their whole territory, it could enter it from the direction of the east, as Alfred evidently did not know well Slavic borders to the East.[131] According Łowmiański, with the fact that the Frankish chronicles do not mention Croats, while Silesian Croats are a historiographical construction without evidence in historical sources, it indicates that the Croats lived around river Vistula in southern Poland exactly south of Mazovia.[132] In southern and southeastern Poland are usually placed tribes of Vistulans and Lendians, which Łowmiański and Tadeusz Lehr-Spławiński considered as tribes of Croats after happened a division of the Croatian tribal alliance in the 7th century,[67][133][134] but other scholars disagree with the identification of Vistulans and Lendians with the Croats.[135][136]

Croats seemingly were not recorded by the Bavarian Geographer (9th century), however, some scholars assumed that the unknown Sittici ("a region with many peoples and heavily fortified cities") and Stadici ("an infinite population with 516 gords") were part of the Carpathian Croats tribal polity,[137] or that the Croats were part of these unknown tribal designations in Prykarpattia.[138][139][140] Others saw Lendizi (98), Vuislane, Sleenzane (50), Fraganeo (40; Prague[4][141]), Lupiglaa (30 gords), Opolini (20), and Golensizi (5) as possible tribes of Croats.[142][143][25] Lehr-Spławiński, Łowmiański and others argued that the Croats could been hidden behind the tribal names of the Vistulans and Lendians who are mentioned, and locations described, in different sources.[67][144]

More detailed information is given by Arabian historians and explorers. Ahmad ibn Rustah from the beginning of the 10th century recounts that the land of Pechenegs is ten days away from the Slavs and that the city in which lives Swntblk is called ʒ-r-wāb (Džervab > Hrwat), where every month Slavs do three-day long trade fair.[145] Swntblk is called "king of kings", has riding horses, sturdy armor, eats mare's milk, and is more important than Subanj (considered Slavic title župan), who is his deputy.[146] In work by Abu Saʿīd Gardēzī (11th century) the city is also mentioned as ʒ(h)-rāwat,[147] or Džarvat,[148] and as Hadrat by Sharaf al-Zaman al-Marwazi (11th century).[148] In the same way, 10th century Arab historian Al-Masudi in his work The Meadows of Gold mentioned Harwātin or Khurwātīn between Moravians, Chezchs and Saxons.[149][150][151] Abraham ben Jacob in the same century probably has the only Iranian form of the name which is closest to the Vasmer's reconstructed form, hajrawās or hīrwās.[152] The Persian geography book Hudud al-'Alam (10th century), which has information from 9th century, in the area of Slavs mentioned their two capital cities, Wabnit (actually Wāntit, considered as reference to Vyatichi,[153][154] or Antes[145]), the first city East of Slavs, and Hurdāb (Khurdāb), a big city where ruler S.mūt-swyt resides, located below the mountains (probably Carpathians) on river Rūtā (most probably Prut), which springs from the mountains and is on the frontier between Pechenegs (ten days), Hungarians (two days), and Kievan Rus'.[155][156][157][148] In the chronicles of the time word šahr meant "country, state, city" – thus Hurdāb represented Croatia.[147][158] It was a common practice to call a whole region and country by the capital or well-known city, as well a city by the tribal name, especially if was on the periphery where the first contacts of merchants and researchers took place.[159] Although it is generally accepted that Swntblk refers to Svatopluk I of Moravia (870–894), it was puzzling that the country in which he lived and ruled over was called by the sources as Croatia.[160] George Vernadsky also considered that the details on the king's custom of life is evidence of Alanic and Eurasian nomadic origin of the ruling caste among those Slavs.[146] Most probable reason for the use of the Croatian name in the East among Arabs is due to trade routes which led to and passed through the lands of Buzhans, Lendians and Vistulans connecting the city of Kraków with the city of Prague, implying they were partly dependent to the rule of Svatopluk I. These facts exclude the possibility of referring to Croats in Bohemia, placing them in Lesser Poland on the territory of Lendians and Vistulans,[161] or more probably the Revno complex on river Prut in Western Ukraine,[162] and generally in Prykarpattia.[157]

Nestor described how many East Slavic tribes of "...the Polyanians, the Derevlians, the Severians, the Radimichians, and the Croats lived at peace".[163] In 904–907, "Leaving Igor (914–945) in Kiev, Oleg (879–912) attacked the Greeks. He took with him a multitude of Varangians, Slavs, Chuds, Krivichians, Merians, Polyanians, Severians, Derevlians, Radimichians, Croats, Dulebians, and Tivercians, who are pagans. All these tribes are known as Great Scythia by the Greeks. With this entire force, Oleg sallied forth by horse and by ship, and the number of his vessels was two thousand".[164] The list indicates that the closest tribal neighbours were Dulebes-Volhynians,[165][166] The fact no Lechitic tribe was part of Oleg's conquest it is more probable that those Croats were located on river Dniester rather than Vistula.[167] After Vladimir the Great (980–1015) conquered several Slavic tribes and cities to the West,[75] in 992 he "attacked the Croats. When he had returned from the Croatian War, the Pechenegs arrived on the opposite side of the Dnieper".[168] Since then those Croats became part of Kievan Rus and are not mentioned anymore in that territory.[169][75] It seems that Croatian tribes who lived in the area of Bukovina and Galicia got conquered because had too many large tribal capitals with local lords who probably didn't act in a centralized and nationalized manner (polycentric proto-state[170]),[171][172] were pressured by Bohemian, Polish and Hungarian principalities,[173] while were attacked by Kievan Rus' because inhibited Rus' free access to the Vistula valley trade route,[174] and did not want to submit to Kievan centralism and accept Christianity.[175][171][176] After the attack on Croats and Polish marches, Rurikids expanded their realm on the Croatian territory which would be known as Principality of Peremyshl, Terebovlia, Zvenyhorod and eventually Principality of Halych.[177][178][179][180][181][182][183] It is considered that Croatian nobility probably survived and retained local influence, becoming the core of the Galician nobility, who continued to control routes, trade with salt and livestock among others,[170] but also with internal nationalization oppose Kiev.[184]

To the upper accounts by the historians were related the Vladimir the Great's conquest of the Cherven Cities in 981, and Annales Hildesheimenses note that Vladimir threatened to attack the Duke of Poland, Bolesław I the Brave (992 to 1025), in 992.[185] Polish chronicler Wincenty Kadłubek in his Chronica Polonorum (12–13th century) recounted that Bolesław I the Brave conquered some "Hunnos seu Hungaros, Cravatios et Mardos, gentem validam, suo mancipavit imperio".[169][186] The occurrence of the Croatian name together with the Hungarians and Pechenegs and not Moravians and Bohemians, and the fact during the period of Bolesław I the Brave the Polish realm expanded to the territory later-known as Western and Eastern Galicia, indicates that the mentioned Croats most probably lived on the territory of Carpathians.[187]

In the Hebrew book Josippon (10th century) are listed four Slavic ethnic names from Venice to Saxony; Mwr.wh (Moravians), Krw.tj (Croats), Swrbjn (Sorbs), Lwcnj (Lučané or Lusatians), and also a East-West trade route Lwwmn (Lendians), Kr. Kr (Krakow), and Bzjm/Bwjmjn (Bohemians).[188][189][190] Since the Croats are placed between Moravians and Serbs it identified the Croatian realm with the Duchy of Bohemia, arguably also on Vistula.[189]

According to 10th century First Old Slavonic Legend about Wenceslaus I, Duke of Bohemia, after his murder in 929 or 935 which ordered his brother Boleslaus I,[192] their mother Drahomíra fled in exile to Xorvaty.[193][194][195][196] This is the first local account of the Croatian name in Slavic language.[197] While some considered that those Croats lived near Prague,[198][196] others noted that in the case of noble and royal fugitives tried to find security as distant as possible, indicating these Croats probably were located more to the East around Vistula valley.[199][200] There were also some attempts to relate with Croats an anonymous neighbor ruler (vicinus subregulus) who was unsuccessfully helped by Saxons and Thuringians at war against Boleslaus I, but the evidence is inconclusive.[201] The Prague Charter from 1086 AD but with data from 973 mentions that on the Northeastern frontier of the Prague diocese lived "Psouane, Chrouati et altera Chrowati, Zlasane...".[202] It is very rare that on a small territory lived two tribes of the same name, possibly indicating that the Crouati were probably settled East of Zlicans and West of Moravians having a territory around the Elbe river, while the other Chrowati were present in Silesia or along the Upper Vistula in Poland because the diocese expanded up to Kraków and rivers Bug and Styr.[203][204][205] The Eastern part of the diocese territory was part of the Moravian expansion in the 9th and Bohemian expansion in the 10th century.[206] Some scholars located these Czech Croats within the territory of present-day Chrudim, Hradec Králové, Libice and Kłodzko.[207][208] Vach argued that they had the most developed techniques of building fortifications among the Czech Slavs.[209] Many scholars consider that the Slavník dynasty, who competed with the Přemyslid dynasty for control over Bohemia and eventually succumbed to them, was of White Croat origin.[210][211][212][141] After the Slavník dynasty's main Gord (fortified settlement) Libice was destroyed in 995, the Croats aren't mentioned anymore in that territory.[213] However, Łowmiański considered that the Bohemian location and existence of the Croats is very disputable,[191] and those sources mentioning Croats and Croatia at the Carpathian Mountains never mention them around river Elbe in Bohemia.[197]

Thietmar of Merseburg recorded in 981 toponym Chrvuati vicus (also later recorded in 11th–14th century), which is present-day Großkorbetha, between Halle and Merseburg in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany.[214] The Chruuati (901) and Chruuati (981) near Halle.[215] In charter by Henry II is recorded Chruazzis (1012), by Henry III as Churbate (1055), by Henry IV as Grawat (also Curewate, 1086). This settlement today is Korbetha on river Saale, near Weißenfels.[214]

In the 10th–12th centuries Croatian name can be often found in the territory of March and Duchy of Carinthia,[216] as well March and Duchy of Styria.[217] In 954, Otto I in his charter mentions župa Croat – "hobas duas proorietatis nostrae in loco Zuric as in pago Crouuati et in ministerio Hartuuigi",[218] and again in 961 pago Crauuati.[219] The pago Chruuat is also mentioned by Otto II (979), and pago Croudi by Otto III.[220]

Legends

[edit]According to Czech and Polish chronicles, the legendary Lech and Czech came from (White) Croatia.[194][213] The Chronicle of Dalimil (14th century) recounts "V srbském jazyku jest země, jiežto Charvaty jest imě; v téj zemi bieše Lech, jemužto jmě bieše Čech".[213] Alois Jirásek recounted as "Za Tatrami, v rovinách při řece Visle rozkládala se od nepaměti charvátská země, část prvotní veliké vlasti slovanské" (Behind the Tatra Mountains, in the plains of the river Vistula, stretched from immemorial time Charvátská country (White Croatia), the initial part of the great Slavic homeland), and V té charvátské zemi bytovala četná plemena, příbuzná jazykem, mravy, způsobem života (In Charvátská existed numerous tribes, related by language, manners, and way of life).[221] Dušan Třeštík noted that the chronicle tells Czech came with six brothers from Croatia which once again indicates seven chiefs/tribes like in the Croatian origo gentis legend from the 30th chapter of De Administrando Imperio.[222] It is considered that the chronicle refers to the Carpathian Croatia.[223]

One of the legendary figures Kyi, Shchek and Khoryv who founded Kiev, brother Khoryv or Horiv, and its oronym Khorevytsia, is often related to the Croatian ethnonym.[224][225][226] This legend, recorded by Nestor, has similar Armenian transcript from the 7th-8th century, in which Horiv is mentioned as Horean.[227] Paščenko related his name, beside to the Croatian ethnonym, to solar deity Khors.[226] Near Kiev there's a stream where previously existed large homonymous village Horvatka or Hrovatka (destroyed in the time of Joseph Stalin), which flows into Stuhna River.[228] In the vicinity are parts of the Serpent's Wall.[229]

Some scholars consider that Croats could have been mentioned in the Old English and Nordic epic poems, like the verse in the Old English poem Widsith (10th century), which is similar to the one in Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks (13th century), where prior the battle between Goths and Huns, Heidrek died in Harvaða fjöllum (Carpathian Mountains[230][231]) which is sometimes translated as "beneath the mountains of Harvathi", considered somewhere beneath Carpathian Mountains near river Dnieper.[232][233][234][235] Lewicki argued that Anglo-Saxons, as in the case of Alfred the Great where called Croats Horithi, often distorted foreign Slavic names.[236]

The legendary Czech hermit from the 9th century, Svatý Ivan, is mentioned as the son of certain king Gestimul or Gostimysl, who according to the Czech chronicles descended from the Croats or Obotrites.[237]

Modern age

[edit]Polish writer Kazimierz Władysław Wóycicki released work Pieśni ludu Białochrobatów, Mazurów i Rusi z nad Bugu in 1836.[238] In 1861, in the statistical data about population in Volhynia governorship released by Mikhail Lebedkin, were counted Horvati with 17,228 people.[239][151] According to United States Congress Joint Immigration Commission which ended in 1911, Polish immigrants to the United States born in around Kraków reportedly declared themselves as Bielochrovat (i.e. White Croat), which with Krakus and Crakowiak/Cracovinian was "names applying to subdivisions of the Poles".[240][241][242]

The Northern Croats contributed and assimilated into Czech, Polish and Ukrainian ethnos.[22][243][244][245] They are considered as the predecessors of the Rusyns,[246][247][248][249] specifically Dolinyans,[250] Boykos,[251][252] Hutsuls,[253][254] and Lemkos.[255][256][257]

Migration to Croatia

[edit]

Early Slavs, especially Sclaveni and Antae, including the White Croats, invaded and settled the Southeastern Europe since the 6th and 7th century.[258] Their exact place of migration to the Balkans is uncertain, but it is generally argued to be from the region of Galicia (Western Ukraine and Southeastern-Southern Poland) along an Eastern route through the Pannonian Basin and alongside Eastern Carpathians according to historical-archaeological and linguistical data about the main movement of the Avars and Slavs,[259][260][261][262] and that "served as a direct link between Eastern and Southern Slavs".[67][251] Other scholars considered it to be from around Bohemia and Silesia-Lesser Poland along a Western route through the Moravian Gate, but that is disputable because there is no historical source and was never proved that the Croats lived there in the 7th or even 9-10th century.[26][95][263][264]

There exist several hypotheses on the date and historical context of the migration to the Adriatic Sea in the Roman province of Dalmatia, most often being related to the Pannonian Avars activity in late 6th and early 7th century.[265][266][267] It is not clear whether some unnamed Slavs or the Croats plundered the same province and Salona together with the Avars.[268][269] The migration of the Croats according to narrative in DAI is commonly dated between 622 and 627,[259] or 622–638,[270] but the account can be interpreted as a date when the Croats revolted against the Avars after the Croatian migration and settlement in Dalmatia in the late 6th and early 7th century.[271][272][273][268][260][274] It is considered that the uprising happened after failed Siege of Constantinople (626),[275][276][277] or during the Slavic uprising led by Samo against the Avars in 632,[278][279] or around 635–641 when the Avars were defeated by Kubrat of the Bulgars.[280][281] As the Avars were enemies of the Byzantine Empire the involvement of Emperor Heraclius on the side of Croats, and organizing relations with "barbarians" from Roman cities perspective and tradition, cannot be entirely excluded.[282][283][277][284] According to other theorization the migration of the Croats in the 7th century was the second and final Slavic migratory wave to the Balkans.[278][279][76] It is related to the thesis by Bogo Grafenauer about the double migration of South Slavs, that both migrations in DAI are not part of the same story and event.[285][286][287] Although it is possible that some Croatian tribes were present among Slavs in the first Slavic-Avar wave in the 6th century, it is argued that the Croatian migration (from Zakarpattia[286]), seen as of a separate warrior elite group which started anti-Avar rebellions, in the second wave was or not equally numerous to make a significant common-linguistical influence into already present Slavs and natives,[67][285][279][288] or was made of large units with significantly larger number.[289][290][291] Leontii Voitovych instead advances the idea of two separate waves of Croats, first massive wave (587–614) from Galicia forced their way through Pannonia, Bosnia and started the conquest of Dalmatia while second wave (626–630) from West of Galicia finished it.[292] The theory on dual division and migration of the Slavs is criticized for being unnatural and improbable with current argumentation.[293][294] Since the 10th century both Roman and Slavic tradition tried to explain their distant history and depict others (barbarians) or themselves (Slavs) in more positive or negative light.[295] Such theorizations are based on literal interpretation of anachronistic and semi-historical narrative from passages in DAI, and according to more critical historiographical, archaeological and linguistic data and interpretations, the Croats mainly or exclusively arrived with the Avars in the first massive wave from the Eastern Carpathians.[260] Whatever the case, the Croats had to be strong and well-organized enough to get a new homeland by war and victory over Avars.[273][100][296]

On the basis of archaeological data between the late 6th and early 9th century and emergence of cremation burials, it is considered that the dating of Slavic/Croat migration and settlement in Croatia to the beginning of the 7th century is generally reliable.[312] However, it's unclear whether some regional and chronological archaeological differences between Northern, Western and Southern Croatia in the end of 6th until early 8th century are result of two separate Slavic waves (via Moravian Gate and Podunavlje),[313] as well it is difficult, practically impossible,[314] to differentiate Croats from other Sclaveni and Antae.[315][316] Conservatively, the "Old Croat" archaeological period is dated between 7th and early 9th century,[297][317] and were found archaeological parallels in Southeastern (Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Hungary, Bulgaria and Romania) and Central-Eastern (Slovakia, Czechia, Eastern Austria, Poland and Ukraine) countries.[321] Zdenko Vinski and V. V. Sedov argued that the rare findings of objects and ceramics of the first group of Slavs (Sclaveni) of the Prague-Korchak culture dated to the end of 6th and beginning of the 7th century were followed by more numerous second group of Slavs (Antes) of the Prague-Penkovka culture with artifacts of Martinovka culture from Ukraine (found in Dalmatian and Pannonian part of Croatia), while the "Old Croatian" archaeological findings from the 8th–9th century indicate social-political stabilization and stratification.[322][323] Another group of historians and archaeologists, like L. Margetić, A. Milošević, M. Ančić and V. Sokol argued late 8th-early 9th century migration of Croats as Frankish vassals during the Frank-Avar war,[324][325] but it does not have enough evidence and arguments,[294][326][327][328][329] it's not supported in written sources,[330][331][261][329] and is not usually accepted by mainstream scholarship.[298][332][329][333]

In the territory of present-day Croatia, it is considered as archaeologically certain that by the last-third of the 7th century disappear Roman late antiquity and Germanic cultural traces in most part of the region and that there's no obvious continuity between native settlements and cemeteries with newly arrived population and paganism.[334][335] The data shows sudden change of native lifestyle, defensive use and desolation of villa rustica and other smaller cities, destruction of churches and else dated at the end of 6th until mid-7th century.[336] What differentiated Croats from other contemporary Slavs was that Croats or partly brought or very early accepted the practice of inhumation from Roman-Christian natives (possibly gradually accepting Christianity already by 8th century[337]).[338] Besides cremation and skeletal cemeteries, the Slavs in eighth and ninth century North Dalmatia also buried their skeletal remains in tumulus which "could be a reflection of this process in the broader Slavic sphere" (among East Slavs and central region of West Slavs).[339] As assimilated with the remaining Roman population who withdrew to the coastal mountains, cities and islands,[340][341][342][343] the size and influence of the autochthonous population on the modern Croatian ethnogenesis is disputed depending on the interpretation of the archaeological data, considering them as a minority with significant cultural influence or as a majority who outnumbered the Slavs.[298][344][345][346][347] However, archaeological and anthropological data indicate that Slavs/Croats were not in small numbers, probably migrated and settled in several waves, contacts with natives were more prominent in Western and almost non-existent in Pannonian part of Croatia, and that the first Slavs/Croats settled near old-Roman sites in North Dalmatia in the second half of 7th and more prominently since early 8th century.[315][348][349] According to anthropological craniometric studies they arrived as biological homogeneous Slavic group of people without significant similarity to Scythians-Sarmatians and Avars (see Origin hypotheses of the Croats#Anthropology). Medieval Croatian sites in Dalmatia were more closely related to Slavic sites in distant Poland rather than in Lower Pannonia (possibly indicating that the account from DAI about the splitting off a part of the Dalmatian Croats who took rule of Pannonia was related to the political rule rather than ethnic origin),[350][351][352][353] and Carpathian Croats sites in Western Ukraine were also close to medieval Croats which "testify for their common origin".[354][355]

Archeology

[edit]

According to Sedov, all early mentions of Croatian ethnonym are in the areas where ceramics of Prague-Penkovka culture were found. It originated in the area between Dniester and Dnieper, and later expanded to the West and South, and its bearers were the Antes tribes.[356][357] A. V. Majorov and others criticized Sedov's consideration, who almost exclusively related the Croats with Penkovka culture and the Antes, because the territory the Croats inhabited in the middle and upper Dniester and the upper Vistula was part of Prague-Korchak culture related to Sclaveni which was characteristic for the tumulus-type (burial mounds, barrows, kurgan) burial which was also found in the upper Elbe territory where presumably lived the Czech Croats.[358] Their association with Antes, mainly promoted in Sedov's work, is in contradiction with scientific knowledge about historical, archaeological, political and ethnic evidence of the migration period.[359]

Western Ukraine was a contact area between these two cultures in an ethnoculturally diverse environment,[170][140] and they possibly were representatives of both these archaeological cultures and formed before them at the least late 4th or during the 5th century in the area of the intertwining of these cultures around the Dniester basin.[56] It is considered that the Carpathian Croats later between 7th and 10th century were part of the Luka-Raikovets culture, which developed from Prague-Korchak culture, and was characteristic for East Slavic tribes, besides Croats, including Buzhans, Drevlians, Polans, Tivertsi, Ulichs and Volhynians.[360][361][38][362]

According to recent archaeological research of material culture and conclusions on the ethno-tribal affiliation and territorial borders of the Carpathian region from 6th until 10th century, the tribal territory of the Croats ("Great Croatia") is unanimously considered by Ukrainian archaeologists to have included Prykarpattia and Zakarpattia (almost all lands of historical region of Galicia), with eastern border the Upper Dniester basin, south-eastern the Khotyn upland beginning near Chernivtsi on the Prut River and ending in Khotyn on the Dniester River, northern border the watershed of the Western Bug and Dniester River, and western border in Western Carpathian ridges at Wisłoka the right tributary of Upper Vistula in Southeastern Poland.[363][364][365][64] In the Eastern Bukovina region bordered with Tiversti, in Eastern Podolia with Ulichs, to the North along Upper Bug River with Dulebes-Buzhans-Volhynians, to the Northwest with Lendians and West with Vistulans.[365][366] The analysis of housing types, and especially oven cookers in Western Ukraine which "were made out of stone (the Middle and the Upper Dnister areas), or clay (mud and butte types, Volynia)", differentiates main tribal alliances of Croats and Volhynians, but also from Tiversti and Drevlians.[367] The craniometric studies of medieval burial grounds and modern population in the region of Galicia show that the Ukrainian Carpathians population makes a separate anthropological zone of Ukraine, with medieval "Eastern Croats" being "morphologically and statistically different from dolichocranic and mesocephalic massive populations at the lands of the Volynians, the Tyvertsi, and the Drevlyans".[354][355][368][369] It seems that the Eastern Carpathians were not yet border between East and West Slavs as Zakarpattia's archaeological material was Prague-Korchak and Luka-Raikovets culture of East Slavs, only later with some West Slavic influence.[370] The areal of Croats in the 9th-10th century is considered to have been in the valley of Laborec, Uzh, Borzhava and was densely populated.[370] The border with the Slovaks to the West was between rivers Laborec and Ondava.[371]

By the 7th century the Croats started to establish Horods (Gord), and at least since 8th century fortified them with stone defensive works,[372] which became a commerce and trade centers.[75] Galicia was an important geographical location because it connected via an overland route Kiev in the East with Kraków, Buda, Prague and other cities in the West, as well as northwest to the Baltic Sea, southwest to the Pannonian Basin and southeast to the Black Sea.[75][373] Along these routes they founded the settlements of Halych, Zvenyhorod, Terebovlia, Przemyśl (possibly founded by Lendians[374]), and Uzhhorod among many others, of which the last was ruled by a mythical ruler Laborec.[75][246][375]

Archaeological excavations held between 1981 and 1995 which researched Early Middle Age Gords in Prykarpattia and Western Podolia dated between 9th–11th century found that fortified Gords with a range of 0.2 ha made 65%, those of 2 ha 20%, and more than 2 ha 15% in that region.[376] There were more than 35 Gords, including big Gords like Plisnesk, Stilsko, Terebovlia, Halych, Przemyśl, Revno, Krylos, Lviv (Chernecha Hora Street-Voznesensk Street in Lychakivskyi District), Lukovyshche, Rokitne II in Roztochya region, Podillya, Zhydachiv, Kotorin complex, Klyuchi, Stuponica, Pidhorodyshche, Hanachivka, Solonsko, Mali Hrybovychi, Stradch, Dobrostany among others.[377][378][379][380][381][382] Only 12 of them survived until the 14th century.[383] UNESCO in its inclusion of Wooden tserkvas of the Carpathian region in Poland and Ukraine also mentions two large gords at the villages of Pidhoroddya and Lykovyshche near Rohatyn dated between 6th and 8th century and identified with the White Croats.[255]

To the Croats are attributed two Gords of unusually big dimensions and each of them could inhabit tens of thousands of people – Plisnesk with a surface of 450 ha, including a fortress with a pagan center, surrounded by seven long and complex lines of protection, several smaller settlements in the near vicinity, more than 142 burial mounds with both cremation and inhumation partly belonging to warriors and else,[384][385][386] located near village Pidhirtsi and since 2015 regionally protected as a Historic and Cultural Reserve "Ancient Plisnesk";[387] and Stilsko with a surface of 250 ha, including a fortress of 15 ha, defensive line of 10 km,[388][389] located on river Kolodnitsa (used for navigation of ships as was connected to most important river in the region, Dniester[390][391]) between current village Stilsko and Lviv.[42][392] In the vicinity of Stilsko were also found some of the only examples of a pre-Christian period cult building among Slavs,[393][394] for one of which Korčinskij assumed a possible connection with the medieval descriptions of a temple dedicated to the deity Khors.[42][395] Until 2008 near Stilsko have been found more than 50 settlements of open type dated between 8th–10th century,[396] as well around 200 burial mounds.[397][391]

The proto-state of Great Croatia had strong polis-like states.[398][385][399][400] Stilsko, Plisnesk, Halych, Revno, Terebovlia and Przemyśl are argued to have been large "tribal" capitals in 9–10th century.[390][398][399][139] According to archaeological material, Plisnesk, Stilsko and many other settlements and pagan shrines by the end of the 10th and beginning of the 11th century temporary ceased to exist with the extensive layers of fire traces interpreted as evidence of the "Croatian War" by the Vladimir the Great in the end of the 10th century.[401][402][403] It had a devastating effect on the administrative division and population of Eastern Galicia (Great Croatia), ultimately stopping their process of becoming a single unified and centralized state.[399] However, the archaeological data, and 11th century revival of some capitals as East Slavic principalities (Peremyshl, Terebovlia, Zvenyhorod and Halych), show a high economic, demographic, military defense, administrative and political organization in the territory of White Croats.[404][405][406][407]

Excavations of many Slavic kurgan tombs in the Carpathian Mountains in the 1930s and 1960s were also attributed to the Croats.[408] Compared to other East Slavic tribes, the area of the Croats stands out because of very present tiled tombs,[409] and in the 11th and 13th century their appearance in Western Dnieper region is attributed to the Croats, and sometimes also Tivertsi,[410][411] and Ulichs.[412] In the territory of Czech Republic, a significant number of graves with kurgans dated 8th–10th century have been found around the Elbe river where was the presumed territory by the White Croats and Zlicans, as well among Dulebes in the South, and Moravians in the East.[413] The graves with kurgans in northeastern Czechia and lower Silesia, where are usually located the White Croats, can also indicate a Lechite-Croatian contact zone with Upper Lusatia, and these burial customs are main difference between White Croatian and White Serbian territory sites.[414][415]

Religion

[edit]Croatian tribes were like other Slavs polytheists – pagans.[416] Their worldview intertwined with worship of power and war, to which raised places of worship, and demolished those of others.[417] These worships were in contrast to Christianity, and consequently in conflict when Christianism became official religion among the Slavs.[418] The White Croats at the earliest historical sources are mentioned as pagans, and they were similar to the inhabitants of Kievan Rus' who also received Christianity late (988).[419] Some rude form of Christianity probably was introduced before that date, but the land and its people can not be considered as Christian.[420] Slavs often related places of worship with the natural environment, like hills, forests, and water.[421] According to Nestor, Vladimir the Great in 980 raised on a hill near his fort pantheon of Slavic gods; Perun, Khors, Dažbog, Stribog, Simargl, and Mokosh,[175] but as he converted to Christianity in 988 one of the probable reasons Vladimir attacked Croats in 992 was because they didn't want to abandon their old beliefs and accept Christianity.[175][171][176] Some scholars derived Croatian ethnonym from the Iranian word for Sun – Hvar which is related to Iranian solar deity,[422][423] and argued possibility that in the ethnonym of the Croats could be seen archaic religion and mythology – the worship of the Slavic solar deity Khors (Sun, heavenly fire, force, war[424]),[425][426] which possibly is of Iranian origin.[423][427] The assumption is supported by pagan shrines with solar signs on stone walls found on territory of Croats.[423][425] According to Radoslav Katičić, Vitomir Belaj and others research, upon arrival to present-day Croatia, the pagan Slavic customs, folklore, and toponyms related to Perun, Veles, Mokosh among others were preserved much longer than previously thought although Adriatic Croats were Christianized by the 9th century.[428] With the process of Christianization, Perun was substituted with St. Ilija and St. Vid, Veles with St. Mihovil, Mokosh mainly with St. Jelena and St. Mary, and Yarilo with St. Juraj.[429][430] Traces of old tradition can be found in customs and songs of Kolade, Ladarice, Kraljice, Perperuna and Dodola among others and held in periods of Jurjevo and Ivandan.[431][432] According to Belaj's ethnological research in Croatia, the Croats old homeland must have been somewhere in Transcarpathia near Volhynia as share "Volhynian worldview" with Buzhans, Dulebes and Volhynians, and considering latest finds of Prague pottery in Croatia, it "bear witness that at least a part of the population of today's Croatia (and nearby Slovenia) most certainly immigrated from Volhynia".[433]

Origo gentis

[edit]The origo gentis about five brothers and two sisters who came with their folk to Dalmatia, recorded in Constantine VII's work De Administrando Imperio, was probably part of an oral tradition,[76] which contradicts the role of Heraclius in the arrival of Croats to Dalmatia.[434] It is similar to other medieval origo gentis stories (see for e.g. Origo Gentis Langobardorum),[434] and some consider it has the same source as the story of Bulgars recorded by Theophanes the Confessor in which the Bulgars subjugated Seven Slavic tribes,[435] and similarly, Thomas the Archdeacon in his work Historia Salonitana mentions that seven or eight tribes of nobles, who he called Lingones, arrived from Lesser Poland and settled in Croatia under Totila's leadership,[108][222] as well parallels in Herodotus account about five men and two maidens of the Hyperboreans.[436][437] In Archdeacon's account is possibly reflected a Lechitic origin of the Croats, while in the Croatian origo gentis a migration of seven tribes and chieftains.[438][261][439]

Curiously, Croats are seemingly the only Slavic people who had a saga about the period of their migration,[440] and the names are the earliest example of pan-Slavic totemic heroes.[441] Also, compared to other early medieval stories none of them mentions female personalities, but do late medieval Kievan, Polish and Czech chronicles,[442] which could indicate a specific tribal and social organization among the Croats.[287] For example, Łowmiański considered the Mazovians, Dulebes, Croats and Veleti among the oldest Slavic tribes because Mazovians ethnonym was often related to Amazons (-maz-) while the land of women in North Europe was mentioned by Paul the Deacon, Alfred the Great, as well women's city West of Russian lands by Abraham ben Jacob.[443] According to Aleksei S. Shchavelev, they rather and most likely represent Karna and Zhelya, an ancient pair of symbolic and mythopoetic female characters of Slavic traditional ritual of lamentation for the dead ("grief and howl", "sorrow and hardship") found in Kievan chronicles.[444] Another vagueness is a reason and meaning that one of the brothers had a Croatian ethnonym as a name, perhaps indicating he was more important than the other brothers, was a representative of the most prominent clan or tribe around which other gathered, or that the Croats were only one identity among others with which the Adriatic Croats tried to bring legitimacy to the Croatian Kingdom.[287][83] According to Shchavelev, the origo gentis shows early tribal, while later news about Porga the early princely tradition, alongside motif of wandering and finding new homeland, presence of female "rulers", multi-stage formation of power and else found in other Slavic legends.[444]

The origin of the names of five brothers, two sisters and first ruler are a matter of dispute. They are often considered to be of non-Slavic origin,[259][2][76][445] and genuine names, as the anonymous Slavic narrator (probably a Croat) couldn't invent the non-Slavic names of their ancestors in the 9th century.[446] J.J. Mikkola considered them to be of Turkic-Avar origin,[447][448][449] Vladimir Košćak of possible Iranian-Alanic origin,[450] Karel Oštir as pre-Slavic,[445] Aleksandar Loma and Shchavelev proposed four-five Slavic variants,[451] while Alemko Gluhak saw parallels to Old Prussian and other Baltic languages.[452] Stanisław Zakrzewski and Henri Grégoire rejected Turkic origin, and related them to Slavic toponyms in Poland and Slovakia,[453][454] and idea of Avar chiefs "was generally rejected".[210] Josip Modestin connected their names to toponyms from region of Lika in Croatia, where early Croats settled.[455] According to Gluhak, names Kloukas, Lobelos, Kosentzes and possibly Mouchlo don't seem to be part of Scythian or Alanic name directory.[456] Nevertheless, the possible non-Slavic etymology of the names doesn't indicate non-Slavic ethnic identity or origin of White Croats. Borrowing of foreign names was common practice between Sarmatians, Goths and Huns, and rather indicates close sociocultural and political relations between White Croats and non-Slavic people in their ancestral and new homeland.[457]

Brothers:

- Kloukas; has Greek suffix "-as", thus the root Klouk- has several derivations; Mikkola considered Turkic Külük, while Tadeusz Lewicki Slavic Kuluk and Kluka.[458] Grégoire related it with cities Kraków or Głogów.[454] Modestin related it to village Kukljić.[455] Vjekoslav Klaić and Vladimir Mažuranić related to the Kukar family, one of the Twelve noble tribes of Croatia.[459][460] Mažuranić additionally related to contemporary surnames Kukas, Kljukaš, Kljuk.[461] Loma proposed Czechoslovakian kluk (arrow, beak).[462] Gluhak noted several Prussian and Latvian personal names and toponyms with root *klauk-, which relates to sound-writing verbs *klukati (peck) and *klokotati (gurgle).[456] Shchavelev derived from клок волос.[463] Another consideration is it corresponds to mythical figures, Czech Krok and Polish Krak meaning the "raven".[441]

- Lobelos; Mikkola considered it a name of uncertain Avar ruler.[458] Grégoire related it with city Lublin.[454] Modestin related it to Lovinac,[455] similarly Shchavelev considered it is related to the Proto-Slavic root *lov (hunt).[463] Rački considered Ljub, Lub, Luben, while Mažuranić noted similar contemporary surnames like Lubel.[464] Osman Karatay considered common Slavic shift Lobel < Alpel (as in Lab < Elbe).[465] Gluhak noted many Baltic personal names with root *lab- and *lob- e.g. Labelle, Labulis, Labal, Lobal, which derive from *lab- (good) or lobas (bays, ravine, valley).[466] Another consideration is it corresponds as male equivalent to female mythical figures, Czech Libuše and Kievan Lybed, meaning the "swan".[441]

- Kosentzis; Mikkola considered Turkic suffix "-či", and derived it from Turkic koš (camp), košun (army).[458] Grégoire related it with city Košice.[454] Modestin related it to Kosinj.[455] Mažuranić considered it similar to contemporary male names Kosan, Kosanac, Kosančić and Kosinec.[467] Many scholars consider relation with Old-Slavic title word *kosez or *kasez, that meant social class members who freely elected the knez of Carantania (658–828). In the 9th century they became nobles, and their tradition preserved until the 16th century. There were many toponyms with the title in Slovenia, but also in Lika in Croatia.[17][445][451][462][468] Gluhak also noted Baltic names with root *kas- which probably derives from kàsti (dig), and Thracian Kossintes, Cosintos, Cositon.[469] Loma considered to be an evidence of Polish-Old Croatian isogloss kъsçzъ in both the personal name and Polish Ksiądz.[470] Shchavelev derived it from коса/оселец and related it to the Polish name of mythical figure Chościsko of the Piast dynasty of Poland.[463]

- Mouchlo; Mikkola related it to the name of 6th century Hunnic (Bulgar[465] or Kutrigur[471]) ruler Mougel/Mouâgeris.[458] Modestin related it to Mohl(j)ić.[455] Mažuranić considered tribe and toponym Mohlić also known as Moglić or Maglić in former Bužani župa, as well medieval toponym or name Mucla, contemporary surnames Muhoić, Muglič, Muhvić, and Macedonian village Mogila (Turk. Muhla).[472] Emil Petrichevich-Horváth related it to the Mogorović family, one of the Croatian "twelve noble tribes".[473] Gluhak noted Lithuanian muklus and Latvian muka which refer to the mud and marshes, and Prussian names e.g. Mokil, Mokyne.[474] Shchavelev similarly derived from Proto-Slavic мъхъ (Bulgarian мухъл, Lithuanian musos, "forest moss and mold").[463]

- Chrobatos; read as Hrovatos, is generally considered as an anthroponym representing Croatian ethnonym Hrvat/Horvat, and the Croatian tribe.[438] Some scholars like J. B. Bury related it with the Turkic name of the Bulgars khan Kubrat.[108][475] This etymology is problematic, beside from historical viewpoint, as in all forms of Kubrat's name, the letter "r" is third consonant.[475]

Sisters:

- Touga; Mikkola related it with male Turkic name Tugai.[458] Shchavelev noted it to be an obvious Greek transcription of Slavic word tuga (sadness, Proto-Slavic *tǫga) and related it to mythological Karna.[444] Loma related it to Iron Ossetian-Digor Ossetian *tūg/tog (strong, heavy).[451][476] Modestin and Klaić related it to the Tugomirić family, one of the Croatian "twelve noble tribes",[455] as well Klaić noted that in 852 was a settlement Tugari in the Kingdom of Croatia which people in Latin sources were called as Tugarani and Tugarini,[459] while Mažuranić noted certain Tugina and župan Tugomir,[477] and Loma personal names Tugomir/Tugomer among medieval Croats and Serbs.[476] Gluhak noted Old Norse-Germanic *touga (fog, darkness), which meaning wouldn't be much different from other names with Baltic derivation.[478]

- Bouga; Mikkola related it with male Turkic name Buga, while Lewicki noted Turkic name of Hun Bokhas, Peceneg Bogas, and two generals of Arabian kalifs, Bogaj.[448] Shchavelev rejected Turkic names because they were never used as female names, derived it instead from Slavic word выть (howl) and related it to mythological Zhelya.[444][451] Loma proposed Vuga < Sarmatian *Vaugii- < Iranian Vahukii (vahu-, "good").[462] Grégoire, Loma and others mostly related it with the Bug River.[462][454] Modestin and Klaić related it to East-Slavic medieval tribe Buzhans who lived on Bug River, as well medieval Croatian tribe Bužani and its župa Bužani or Bužane.[455][459] Gluhak noted Proto-Slavic word *buga which in Slavic languages mean "swamp" like places, and the river Bug itself derives from.[478]

First ruler:

- Porga from 31st chapter according to Loma and Živković derives from Iranian pouru-gâo, "rich in cattle".[476][479] Mažuranić noted it was a genuine personal name in medieval Croatia at least since 12th as well Bosnia since 13th century in the form of Porug (Porugh de genere Boić, nobilis de Tetachich near terrae Mogorovich), Poruga, Porča, Purća / Purča, and Purđa (vir nobilis nomine Purthio quondam Streimiri).[480] However, in the 30th chapter, it is named Porin, and recently Milošević, Alimov, and Budak supported a thesis which considered these names as two variants of the Slavic deity Perun, as a heavenly ruler and not an actual secular ruler.[481][482]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 95.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rončević, Dunja Brozović (1993). "Na marginama novijih studija o etimologiji imena Hrvat" [On some recent studies about the etymology of the name Hrvat]. Folia onomastica Croatica (in Croatian) (2): 7–23. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ Matasović, Ranko (2008), Poredbenopovijesna gramatika hrvatskoga jezika [A Comparative and Historical Grammar of Croatian] (in Croatian), Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, p. 44, ISBN 978-953-150-840-7

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Charvát, Petr (2010). The Emergence of the Bohemian State. Brill. pp. 78, 80, 102. ISBN 978-90-474-4459-6.

- ^ Sedov 2013, pp. 115, 168, 444.

- ^ Budak 2018, p. 98.

- ^ Pohl, Heinz-Dieter (1970). "Die slawischen Sprachen in Jugoslawien" [The Slavic languages in Yugoslavia]. Der Donauraum (in German). 15 (1–2): 72. doi:10.7767/dnrm.1970.15.12.63. S2CID 183316961.

Srbin, Plural Srbi: "Serbe", wird zum urslawischen *sirbŭ "Genosse" gestellt und ist somit slawischen Ursprungs41. Hrvat "Kroate", ist iranischer Herkunft, über urslawisches *chŭrvatŭ aus altiranischem *(fšu-)haurvatā, "Viehhüter"42.

- ^ Arumaa, Peeter (1976). Urslavische Grammatik: Einführung in das vergleichende Studium der slavischen Sprachen (in German). C. Winter. p. 180. ISBN 978-3-533-02283-1.

- ^ Kunstmann, Heinrich (1982). "Über den Namen der Kroaten" [About the name of the Croatians]. Die Welt der Slaven (in German). 27: 131–136.

- ^ Trunte, Hartmut (1990). Slovĕnʹskʺi i︠a︡zykʺ: Ein praktisches Lehrbuch des Kirchenslavischen in 30 Lektionen: zugleich eine Einführung in die slavische Philologie (in German). Sagner. p. 21. ISBN 978-3-87690-716-1.

- ^ Majorov 2012, pp. 86–100, 129.

- ^ Matasović, Ranko (2019), "Ime Hrvata" [The Name of Croats], Jezik (Croatian Philological Society) (in Croatian), 66 (3), Zagreb: 81–97

- ^ Heršak & Nikšić 2007, p. 262.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 25.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 36–37, 40–43.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Marčinko 2000, pp. 318–319, 433.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gluhak 1990, p. 127.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Danylenko 2004, pp. 1–32.

- ^ Škegro 2005, p. 13.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, pp. 88, 91–92.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, pp. 87–95.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Łowmiański 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Majorov 2012, pp. 23–24, 37–41.

- ^ Majorov 2012, p. 167.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Niederle, Josef (2015). "Alemure, Cumeoberg, Mons Comianus, Omuntesberg, Džrwáb, Wánít. Lokalizace záhadných míst z úsvitu dějin Moravy" [Localization of enigmatic places from the early history of Moravia and Slavs]. Skalničkářův rok. 71A. ISSN 1805-1170. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Овчинніков 2000, p. 153.

- ^ Kuchynko 2015, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Živković 2012, pp. 84–88.

- ^ Majorov 2012, pp. 24, 42–47.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, pp. 122–125.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, p. 27.

- ^ Kim 2013, pp. 146, 262.

- ^ Majorov 2012, p. 29.

- ^ Majorov 2012, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Majorov 2012, pp. 26–28.

- ^ Majorov 2012, p. 28.

- ^ Magocsi 1983, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Синица, Е.В. (2013). "ХОРВАТЬ" . Encyclopedia of Russian History (in Russian). Vol. 10. Наукова Думка , НАСУ институт истории Украини . ISBN 978-966-00-1359-9 .

Их часто необоснованно называют также "белыми хорватами". Это связано с тем, что восточноевропейский. Х. ошибочно отождествляют с "хорватами белыми" (упоминаются в недатированной части "Повести временных лет" в одном ряду с сербами и хорутанами) и "белохорватами" (фигурируют в трактате визант. имп. Константина VII Багрянородного "Об управлении империей"); в обоих случаях речь идет о славянах. племена на Балканах – предков населения современной Хорватии... единственное из летописных племен, для которого "Повесть временных лет" не указывает территорию расселения. Локализация Х. в Прикарпатье и, возможно, Закарпатье базируется на двух основаниях: 1) в этих регионах в 8-10 вв. распространены памятники райковецкой культуры, присущей всем восточнославянам. племенам Правобережья в указанное время; 2) эта часть ареала райковецкой к-ры лежит вне расселения ин. летописных племен, упомянутых в "Повести временных лет". Гомогенность райковецких древностей, которые не членятся на относительно четкие локальные варианты, не позволяет конкретизировать границы Х. и их соседей (волынян/бужан на с. и с. в., уличей на ю. в. и тиверцев на ю.). Определенной особенностью райковецких памятников Прикарпатья является распространенность городищ-хранилищ, которые были одновременно сакральными центрами (имели капища и "длинные дома"-контины, предназначенные для общинных банкетов-братчин).

- ^ Воитовых, Леонтии (2011). "Проблема "белых хорватов" ". Галицко-волынские этюды (PDF) . Белая Церковь. ISBN 978-966-2083-97-2 . Проверено 5 июля 2019 г.

Пер.: Исходя из вышесказанного, закарпатские хорваты и хорваты жили вблизи рек Днестр и Сан. Правильнее было бы назвать карпатских хорватов, как сказал Я. Предлагал Исаевич, а не белые хорваты, как пишет большинство украинских и российских авторов. Белые хорваты располагались в верховьях Вислы и Одера, в Саале и Белом Эльстере, где С. Пантелеич отыскивал целые области, еще пользовавшиеся автономией в XIV–XV вв., и остатки топонимии.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: отсутствует местоположение издателя ( ссылка ) - ^ А. В. Майоров (2017). "ХОРВА́ТЫ ВОСТОЧНОСЛАВЯ́НСКИЕ" . Great Russian Encyclopedia (in Russian). Bolshaya Rossiyskaya Entsiklopediya, Russian Academy of Sciences .

По данным ср.-век. письм. источников и топонимии, хорваты локализуются на северо-западе Балкан (предки совр. хорватов); на части земель в бассейнах верхнего течения Эльбы, Вислы, Одры, возможно, и Моравы (белые хорваты, по-видимому, в значении "западные"); на северо-востоке Прикарпатья (отчасти и в Закарпатье).

- ^ Пащенко 2006 , стр. 115–116.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Корчинский 2006а , с. 37.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , pp. 87–89.

- ^ Кучинко 2015 , с. 140.

- ^ Филипчук 2015а , с. 13.

- ^ Глухак 1990 , с. 100–101.

- ^ Глухак 1990 , с. 101–102.

- ^ Глухак 1990 , стр. 102.

- ^ Пащенко 2006 , стр. 42–54.

- ^ Sedov 2013 , pp. 115, 168.

- ^ Глухак 1990 , стр. 110.

- ^ Пащенко 2006 , с. 84.

- ^ Глухак 1990 , с. 115–116.

- ^ Пащенко 2006 , стр. 84–87.

- ^ Sedov 2013 , pp. 444, 451, 501, 516.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Majorov 2012 , pp. 85–86, 168.

- ^ Кошчак 1995 , стр. 111.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пащенко 2006 , с. 141.

- ^ Гершак и Никшич 2007 , стр. 263.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 42–43.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , pp. 155–157, 180.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , p. 165.

- ^ Timoshchuk 1995b , pp. 165–174.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Holovko 2018 , p. 86.

- ^ Sedov 2013 , pp. 168, 444, 451, 501, 516.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , pp. 50, 58–59, 155–157, 163, 180.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Лер-Сплавинский, Тадеуш (1951). «Проблема вислинских хорватов». Славянский дневник (на польском языке). 2 : 17–32.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Sedov 2013 , pp. 168, 444, 451.

- ^ Кучинко 2015 , с. 142.

- ^ Мальчик 2018 , с. 93.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 12, 23, 47, 58, 68.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , p. 48–63, 171.

- ^ Мальчик 2018 , с. 93–94.

- ^ Магочи 1983 , с. 49.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Магочи 2002 , с. 4.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Ван Антверпен Файн мл. 1991 , стр. 53, 56.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , p. 58.

- ^ Дзино 2010 , стр. 113, 21.

- ^ Глухак 1990 , с. 305–306.

- ^ Шкегро 2005 , стр. 12.

- ^ Норрис 1993 , с. 15.

- ^ Лэнгстон, К.; Пети-Стантик, А. (2014). Языковое планирование и национальная идентичность в Хорватии . Пэлгрейв Макмиллан, Великобритания. стр. 57–60. ISBN 978-1-137-39060-8 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гольдштейн, Иво (1989). «Об этногенезе хорватов в раннем средневековье». Миграция и этнические темы (на хорватском языке). 5 (2–3): 221–227 . Проверено 21 августа 2020 г.

- ^ Dvornik 1962 , p. 95.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 8–9, 11, 13–14, 22.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , pp. 60–63, 80.

- ^ Voitovych 2010 , p. 47-48.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , pp. 31–35.

- ^ Кросс и Шербовиц-Ветзор 1953 , с. 53.

- ^ Глухак 1990 , с. 116–117.

- ^ Живкович 2012 , стр. 111–122.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 71–72.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , pp. 70–73.

- ^ Будак 1995 , стр. 141–143, 147.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Sedov 2013 , p. 450–451.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , pp. 48, 54, 58, 61–63.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 12–13, 99.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 15, 82, 84.

- ^ Живкович 2012 , стр. 89, 111, 113, 120.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Majorov 2012 , p. 21.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 75.

- ^ Живкович 2012 , стр. 111–113.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Живкович 2012 , стр. 120.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 58.

- ^ Хшановский, Витольд (2008). Летопись славян: Поляна . Либрон. стр. 177, 192. ISBN. 978-83-7396-749-6 .

- ^ Dvornik 1962 , p. 98–99.

- ^ Dvornik 1962 , p. 99, 118.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Гершак и Никшич 2007 , стр. 259.

- ^ Глухак 1990 , с. 129–130.

- ^ Глухак 1990 , стр. 130.

- ^ Мальчик 2018 , с. 99–100.

- ^ Дженкинс, Ромилли Джеймс Хилд (1962). Константин Багрянородный, De Adminstando Imperio: Том 2, Комментарии . Атлон Пресс. стр. 139, 216.

- ^ Пашкевич, Генрик (1977). Становление русской нации . Гринвуд Пресс. п. 359. ИСБН 978-0-8371-8757-0 .

- ^ Живкович, Тибор (2001). «На северных границах Сербии в раннем средневековье» [На северных границах Сербии в раннем средневековье]. Труды Матицы Сербской по истории (на сербском языке). 63/64: 11.

Багрянородный называет племена в Захумле, Пагании, Травунии и Конавле сербами,28 отделяя их политическое от этнического бытия.29 Эта интерпретация, вероятно, не самая удачная, потому что для Михаила Вишевича, князя Захумля, говорит он, что он родом из Вислы, из рода Лицика30, и что река эта находится слишком далеко от территории белых сербов и где следует ожидать белых хорватов. Это первое указание на то, что сербское племя могло стоять во главе более крупного союза славянских племен, пришедшего вместе с ним на Балканский полуостров и под верховным руководством сербского архонта.

- ^ Живкович 2012 , стр. 49, 54, 83, 88.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Dvornik 1962 , p. 130.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Живкович 2012 , стр. 89.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , pp. 65, 69.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 79.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 78.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , pp. 49–50, 56, 78–80.

- ^ Босворт 1859 , с. 37, 53–54.

- ^ Ингрэм 1807 , с. 72.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 53–60.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , p. 52.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 48–53.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 56.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 57.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 57–59.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , p. 52–53.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 57–58.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 51, 58–60.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 51, 57–60, 94, 125–126.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , pp. 51–52, 56, 59.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , p. 56.

- ^ Войтович 2011 , с. 26, 29:Х. Ловмянский также решил, что по крайней мере одно из племен хорватов, названных в Пражской привилегии, могло бы без колебаний располагаться на Висле и отождествляться с вишуланцами, при этом без всякого обоснования опуская замечания Владислава Кентшинского и выводы Я. Видаевича, который не допускал возможности отождествления вишулян с хорватами.

- ^ Koncha 2012 , p. 17.

- ^ Кугутяк 2017 , с. 26.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Томенчук 2017 , с. 32.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Томенчук 2018 , с. 13.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Беренд, Нора; Урбанчик, Пшемыслав; Вишевский, Пшемыслав (2013). Центральная Европа в эпоху высокого средневековья: Богемия, Венгрия и Польша, ок. 900–1300 гг . Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 84. ISBN 978-1-107-65139-5 .

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 59.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2013 , стр. 120.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 16, 18, 59, 94, 125–126.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Глухак 1990 , с. 212–213.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вернадский 2008 , стр. 262–263.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Глухак 1990 , с.212.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Majorov 2012 , p. 161.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 62.

- ^ Глухак 1990 , с. 211.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Зимони 2015 , стр. 295, 319.

- ^ Векслер, Пол (2019). «Как идиш может восстановить скрытые азиатизмы в славянском языке, а также азиатизмы и славизмы в немецком языке (пролегомены к типологии азиатских языковых влияний в Европе)». Андрей Даниленко, Мотоки Номачи (ред.). Славянский язык на языковой карте Европы: историческое и ареально-типологическое измерения . Де Грюйтер. п. 239. ИСБН 978-3-11-063922-3 .

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 62, 64, 66.

- ^ Овчинников 2000 , p. 157-158.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 62, 66.

- ^ Глухак 1990 , с. 211–212.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Овчинников 2000 , p. 156-157.

- ^ Корчинский 2006а , с. 32.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 61–63.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 61–63, 65.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 64–68.

- ^ Томенчук 2018 , с. 21.

- ^ Кросс и Шербовиц-Ветзор 1953 , с. 56.

- ^ Кросс и Шербовиц-Ветзор 1953 , с. 64.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , pp. 54, 69.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 97.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 98.

- ^ Кросс и Шербовиц-Ветзор 1953 , с. 119.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Глухак 1990 , с.144.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Томенчук 2018 , с. 17.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Хупало 2014 , стр. 81.

- ^ Томенчук 2018 , стр. 15.

- ^ Томенчук 2018 , с. 17–18.

- ^ Ханак 2013 , с. 32.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Пащенко 2006 , с. 123.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Holovko 2018 , p. 90.

- ^ Кросс и Шербовиц-Ветзор 1953 , с. 250.

- ^ Магочи 1983 , с. 56.

- ^ Корчинский 2000 , с. 113.

- ^ Корчинский 2006а , с. 39.

- ^ Хупало 2014 , стр. 73–75, 89–91, 96.

- ^ Томенчук 2017 , с. 33.

- ^ Томенчук 2017 , с. 42–43.

- ^ Томенчук 2018 , с. 18.

- ^ Ловмяньский 2004 , стр. 96.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , p. 74.

- ^ Majorov 2012 , pp. 74–75.

- ^ Глухак 1990 , с.214.