Даки

Даки : ( / ˈ d eɪ ʃ ən z / ; латынь Δάκοι Daci [ˈdaːkiː] ; греческий : , [2] Дао, [2] Дакийский [3] ) — древние индоевропейские жители культурной области Дакия , расположенной в районе Карпат и к западу от Чёрного моря . Их часто считают подгруппой фракийцев . [4] Эта территория включает в себя в основном современные страны Румынии и Молдовы , а также части Украины . [5] Восточная Сербия , Северная Болгария , Словакия , [6] Венгрия и Южная Польша . [5] Даки и родственные им геты [7] говорили на дакийском языке , который имеет спорную связь с соседним фракийским языком и может быть его подгруппой. [8] [9] Даки находились под некоторым культурным влиянием соседних скифов и кельтских захватчиков IV века до нашей эры .

| Эта статья является частью серии, посвящённой |

|

| Дакия |

| География |

|---|

| Культура |

| История |

| Римская Дакия |

| Наследие |

Имя и этимология

[ редактировать ]Имя

[ редактировать ]Даки были известны как геты (множественное число геты ) в древнегреческих писаниях. [ нужна ссылка ] и как Дакус (множественное число Даки ) или Геты в римских документах, [10] но также как Даги и Гаэте , изображенные на позднеримской карте Tabula Peutingeriana . Именно Геродот впервые употребил этноним геты в своих «Историях» . [11] На греческом и латинском языках, в трудах Юлия Цезаря , Страбона и Плиния Старшего , этот народ стал известен как «даки». [12] Геты и даки были взаимозаменяемыми терминами или использовались греками с некоторой путаницей. [13] [14] Латинские поэты часто использовали имя гетов . [15] Вергилий называл их гетами четыре раза, а Даки — один раз, Лукиан — гетами трижды и дважды Даками , Гораций называл их гетами дважды, а Даками — пять раз, а Ювенал — один раз гетами и два раза даками . [16] [17] [15] В 113 году нашей эры Адриан использовал поэтический термин «геты» для обозначения даков. [18] Современные историки предпочитают использовать название гето-даков . [12] Страбон описывает гетов и даков как отдельные, но родственные племена. Это различие относится к регионам, которые они оккупировали. [19] Страбон и Плиний Старший также утверждают, что геты и даки говорили на одном языке. [19] [20]

Напротив, имя даков , каково бы ни было происхождение названия, использовалось более западными племенами, которые соседствовали с паннонийцами и поэтому впервые стали известны римлянам. [21] Согласно «Географии» Страбона , первоначальное название даков было Δάοι « Даой ». [2] Название даой (одно из древних гето-дакских племен) наверняка было принято иностранными наблюдателями для обозначения всех жителей стран к северу от Дуная , еще не завоеванных Грецией или Римом. [12] [12]

Этнографическое название Дачи встречается в различных формах в древних источниках. Греки использовали формы Δάκοι « Дакой » ( Страбон , Дион Кассий и Диоскорид ) и Δάοι «Даой» (единственное число Даос). [22] [2] [23] [а] [24] форма Δάοι «Даой» часто использовалась Согласно Стефану Византийскому, . [17]

Латиняне использовали формы Davus , Dacus и производную форму Dacisci (Vopiscus и надписи). [25] [26] [27] [17]

Существуют сходства между этнонимами даков и дахов ( греч. Δάσαι Δάοι, Δάαι, Δαι, Δάσαι Dáoi , Dáai , Dai , Dasai ; лат. Dahae , Daci ), индоевропейского народа, располагавшегося к востоку от Каспийского моря , вплоть до I тысячелетие до нашей эры. Ученые предполагают, что связи между двумя народами существовали с древних времен. [28] [29] [30] [17] Более того, историк Дэвид Гордон Уайт заявил, что «даки ... похоже, связаны с дахами». [31] (Аналогично Уайт и другие ученые также полагают, что имена Дации и Дахэ также могут иметь общую этимологию - дополнительную информацию см. В следующем разделе.)

К концу первого века нашей эры все жители земель, составляющих ныне Румынию, были известны римлянам как даки, за исключением некоторых кельтских и германских племен, проникших с запада, а также сарматов и родственных им народов с востока. . [14]

Этимология

[ редактировать ]Название даки , или «даки» — собирательный этноним . [32] Дион Кассий сообщал, что сами даки пользовались этим именем, и римляне называли их так, а греки называли их гетами. [33] [34] [35] Мнения о происхождении имени Дачи разделились. Некоторые учёные полагают, что оно происходит от индоевропейского * dha-k- с основой * dhe — «помещать, помещать», в то время как другие полагают, что имя Дачи происходит от * daca «нож, кинжал» или от слово, похожее на даос, означающее «волк» на родственном языке фригийцев . [36] [37]

Одна из гипотез состоит в том, что имя гетов происходит от индоевропейского * guet — «произносить, говорить». [38] [36] Другая гипотеза состоит в том, что геты и даки — это иранские названия двух ираноязычных скифских групп, которые были ассимилированы с более крупным фракийскоязычным населением более поздней «Дакии». [39] [40]

Ранняя история этимологических подходов

[ редактировать ]В I веке нашей эры Страбон предположил, что его основа образовала имя, ранее носившееся рабами: греческий Даос, латинский Давус (-к- — известный суффикс в индоевропейских этнических именах). [41] В 18 веке Гримм предложил готическое даг или «день», что дало бы значение «светлый, блестящий». Тем не менее, дагс принадлежит к санскритскому корню слова да- , и вывод от Даха до Δάσαι «Дачи» затруднен. [17] В 19 веке Томашек (1883) предложил форму «Дак», означающую тех, кто понимает и может говорить , рассматривая «Дак» как производное от корня да («к» является суффиксом); ср. Санскритский даса , бактрийский даонха . [42] Томашек предложил также форму «Давус», означающую «члены рода/земляки», ср. Бактрийский дакю , данху «кантон». [42]

Современные теории

[ редактировать ]Начиная с XIX века, многие ученые предлагали этимологическую связь между эндонимом даков и волков.

- Возможную связь с фригийцами предложил Димитар Дечев (в работе, не опубликованной до 1957 г.). [ нужна ссылка ] на фригийском языке Слово даос означало «волк». [ нужна ссылка ] и Даос также был фригийским божеством. [43] В более поздние времена римские вспомогательные войска , набранные из даков, также были известны как Фриги . [ нужна ссылка ] Такая связь подтверждается материалами Исихия Александрийского (V/VI века), [44] [45] а также историк 20-го века Мирча Элиаде . [43]

- Немецкий лингвист Пауль Кречмер связал даос с волками через корень дхау , означающий давить, собирать или душить – т.е. считалось, что волки часто укусят свою добычу в шею, чтобы убить свою добычу. [31] [46]

- Эндонимы, связанные с волками, были продемонстрированы или предложены для других индоевропейских племен , включая лувийцев , ликийцев , луканцев , гирканцев и, в частности, дахов (юго-восточного Прикаспия), [47] [48] которые были известны на древнеперсидском языке как Даос . [43] Такие ученые, как Дэвид Гордон Уайт, явно связали эндонимы даков и дахов. [31]

- Венгерский лингвист и историк доктор Виктор Падани пишет: «Судя по всему, их название происходит от шумерского слова «даг, таг», означающего двуручный топор, боевой топор». [49]

- « Драко » , штандарт даков, также имел волчью голову.

Однако, по мнению румынского историка и археолога Александру Вулпе , дакийская этимология, объясненная словом даос («волк»), малоправдоподобна, поскольку преобразование даос в дакос фонетически маловероятно, а стандарт Драко не был уникальным для даков. Таким образом, он отвергает это слово как народную этимологию . [50]

Другая этимология, связанная с протоиндоевропейского языка корнями *dhe-, что означает «устанавливать, размещать», а также dheua → dava («поселение») и dhe-k → daci, поддерживается румынским историком Иоанном И. Руссу (1967). . [51]

Мифологические теории

[ редактировать ]

Мирча Элиаде в своей книге « От Залмоксиса до Чингисхана » попытался дать мифологическую основу предполагаемым особым отношениям между даками и волками: [52]

- Даки могли называть себя «волками» или «такими же, как волки». [53] [52] намекая на религиозное значение. [54]

- Даки получили свое имя от бога или легендарного предка, который появился в образе волка. [54]

- Даки получили свое название от группы беглых иммигрантов, прибывших из других регионов, или от собственных молодых преступников, которые вели себя подобно волкам, кружащим по деревням и живущим за счет грабежей. Как и в других обществах, эти молодые члены общины проходили посвящение, возможно, до года, в течение которого они жили как «волки». [55] [54] Для сравнения, в хеттских законах беглых преступников называли «волками». [56]

- Существование ритуала, дающего возможность превратиться в волка. [57] Такая трансформация может быть связана либо с самой ликантропией , явлением широко распространенным, но засвидетельствованным особенно в Балканско - Карпатском регионе, [56] или ритуальная имитация поведения и внешнего вида волка. [57] Подобный ритуал, по-видимому, был военным посвящением, потенциально предназначенным для тайного братства воинов (или Männerbünde ). [57] Чтобы стать грозными воинами, они переняли поведение волка, надев волчьи шкуры во время ритуала. [54] Следы, связанные с волками как с культом или тотемами, были обнаружены в этой области со времен неолита , в том числе артефакты культуры Винча : статуи волков и довольно элементарные фигурки, изображающие танцоров в волчьей маске. [58] [59] Эти предметы могли обозначать обряды инициации воинов или церемонии, во время которых молодые люди надевали сезонные волчьи маски. [59] Элемент единства представлений об оборотнях и ликантропии существует в магико-религиозном опыте мистической солидарности с волком, какими бы способами он ни был достигнут. Но у всех есть один оригинальный миф, главное событие. [60] [61]

Истоки и этногенез

[ редактировать ]Свидетельства существования протофракийцев или протодаков в доисторический период зависят от остатков материальной культуры . Обычно предполагается, что протодакийский или протофракийский народ произошел от смеси коренных народов и индоевропейцев со времени протоиндоевропейской экспансии в раннем бронзовом веке (3300–3000 до н.э.). [62] когда последний, около 1500 г. до н. э., завоевал коренные народы. [63] Коренными жителями были дунайские земледельцы, а завоевателями III тысячелетия до н. э. — курганные воины-скотоводы из украинских и русских степей. [64]

Индоевропеизация завершилась к началу бронзового века. Людей того времени лучше всего описать как протофракийцев, которые позже в железном веке развились в дунайско-карпатских гето-даков, а также фракийцев восточной части Балканского полуострова. [65]

Между 15–12 веками до нашей эры культура даков-гетов находилась под влиянием воинов курганов-урнфилдов бронзового века, которые направлялись через Балканы в Анатолию. [66]

В VIII-VII веках до нашей эры миграция скифов с востока в Понтийскую степь оттеснила на запад и от степей родственный скифский народ агафирсов, ранее обитавший в Понтийской степи вокруг озера Меотида . [67] Вслед за этим агафирсы расселились на территориях нынешней Молдавии , Трансильвании и, возможно, Олтении , где смешались с коренным населением фракийского происхождения. [68] [67] Когда позже агафирсы были полностью ассимилированы гето-фракийским населением; [68] их укрепленные поселения стали центрами гетских групп, которые позже трансформировались в дакийскую культуру; значительная часть даков произошла от агафирсов. [68] When the La Tène Celts arrived in the 4th century BC, the Dacians were under the influence of the Scythians.[66]

Alexander the Great attacked the Getae in 335 BC on the lower Danube, but by 300 BC they had formed a state founded on a military democracy, and began a period of conquest.[66] More Celts arrived during the 3rd century BC, and in the 1st century BC the people of Boii tried to conquer some of the Dacian territory on the eastern side of the Teiss river. The Dacians drove the Boii south across the Danube and out of their territory, at which point the Boii abandoned any further plans for invasion.[66]

Some Hungarian historians consider the Dacians and Getae the same as the Scythian tribes of the Dahae, Massagetae, also the exonym Daxia one with Dacia.[49][69]

Identity and distribution

[edit]This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. Please help to create a more balanced presentation. Discuss and resolve this issue before removing this message. (October 2018) |

This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (October 2018) |

North of the Danube, Dacians occupied[when?] a larger territory than Ptolemaic Dacia,[clarification needed] stretching between Bohemia in the west and the Dnieper cataracts in the east, and up to the Pripyat, Vistula, and Oder rivers in the north and northwest.[70][better source needed] In 53 BC, Julius Caesar stated that the Dacian territory[clarification needed] was on the eastern border of the Hercynian forest.[66] According to Strabo's Geographica, written around AD 20,[71] the Getes (Geto-Dacians) bordered the Suevi who lived in the Hercynian Forest, which is somewhere in the vicinity of the river Duria, the present-day Váh (Waag).[72] Dacians lived on both sides of the Danube.[73] [74] According to Strabo, Moesians also lived on both sides of the Danube.[35] According to Agrippa,[75] Dacia was limited by the Baltic Ocean in the North and by the Vistula in the West.[76] The names of the people and settlements confirm Dacia's borders as described by Agrippa.[75][77] Dacian people also lived south of the Danube.[75]

Linguistic affiliation

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

The Dacians and Getae were always considered as Thracians by the ancients (Dio Cassius, Trogus Pompeius, Appian, Strabo and Pliny the Elder), and were both said to speak the same Thracian language.[78][79] The linguistic affiliation of Dacian is uncertain, since the ancient Indo-European language in question became extinct and left very limited traces, usually in the form of place names, plant names and personal names. Thraco-Dacian (or Thracian and Daco-Mysian)[which?] seems to belong to the eastern (satem) group of Indo-European languages.[why?][80] There are two contradictory theories: some scholars (such as Tomaschek 1883; Russu 1967; Solta 1980; Crossland 1982; Vraciu 1980) consider Dacian to be a Thracian language or a dialect thereof. This view is supported by R. G. Solta, who says that Thracian and Dacian are very closely related languages.[8][9] Other scholars (such as Georgiev 1965, Duridanov 1976) consider that Thracian and Dacian are two different and specific Indo-European languages which cannot be reduced to a common language.[81] Linguists such as Polomé and Katičić expressed reservations[clarification needed] about both theories.[82]

The Dacians are generally considered to have been Thracian speakers, representing a cultural continuity from earlier Iron Age communities loosely termed Getic,[83] Since in one interpretation, Dacian is a variety of Thracian, for the reasons of convenience, the generic term ‘Daco-Thracian" is used, with "Dacian" reserved for the language or dialect that was spoken north of Danube, in present-day Romania and eastern Hungary, and "Thracian" for the variety spoken south of the Danube.[84] There is no doubt that the Thracian language was related to the Dacian language which was spoken in what is today Romania, before some of that area was occupied by the Romans.[85] Also, both Thracian and Dacian have one of the main satem characteristic changes of Indo-European language, *k and *g to *s and *z.[86] With regard to the term "Getic" (Getae), even though attempts have been made to distinguish between Dacian and Getic, there seems no compelling reason to disregard the view of the Greek geographer Strabo that the Daci and the Getae, Thracian tribes dwelling north of the Danube (the Daci in the west of the area and the Getae further east), were one and the same people and spoke the same language.[84]

Another variety that has sometimes been recognized is that of Moesian (or Mysian) for the language of an intermediate area immediately to the south of Danube in Serbia, Bulgaria and Romanian Dobruja: this and the dialects north of the Danube have been grouped together as Daco-Moesian.[84] The language of the indigenous population has left hardly any trace in the anthroponymy of Moesia, but the toponymy indicates that the Moesii on the south bank of the Danube, north of the Haemus Mountains, and the Triballi in the valley of the Morava, shared a number of characteristic linguistic features[specify] with the Dacii south of the Carpathians and the Getae in the Wallachian plain, which sets them apart from the Thracians though their languages are undoubtedly related.[87]

Dacian culture is mostly followed through Roman sources. Ample evidence suggests that they were a regional power in and around the city of Sarmizegetusa. Sarmizegetusa was their political and spiritual capital. The ruined city lies high in the mountains of central Romania.[88]

Vladimir Georgiev disputes that Dacian and Thracian were closely related for various reasons, most notably that Dacian and Moesian town names commonly end with the suffix -DAVA, while towns in Thrace proper (i.e. South of the Balkan mountains) generally end in -PARA (see Dacian language). According to Georgiev, the language spoken by the ethnic Dacians should be classified as "Daco-Moesian" and regarded as distinct from Thracian. Georgiev also claimed that names from approximately Roman Dacia and Moesia show different and generally less extensive changes in Indo-European consonants and vowels than those found in Thrace itself. However, the evidence seems to indicate divergence of a Thraco-Dacian language into northern and southern groups of dialects, not so different as to qualify as separate languages.[89] Polomé considers that such lexical differentiation ( -dava vs. para) would, however, be hardly enough evidence to separate Daco-Moesian from Thracian.[82]

Tribes

[edit]

An extensive account of the native tribes in Dacia can be found in the ninth tabula of Europe of Ptolemy's Geography.[90] The Geography was probably written in the period AD 140–150, but the sources were often earlier; for example, Roman Britain is shown before the building of Hadrian's Wall in the AD 120s.[91] Ptolemy's Geography also contains a physical map probably designed before the Roman conquest, and containing no detailed nomenclature.[92] There are references to the Tabula Peutingeriana, but it appears that the Dacian map of the Tabula was completed after the final triumph of Roman nationality.[93] Ptolemy's list includes no fewer than twelve tribes with Geto-Dacian names.[94][95]

The fifteen tribes of Dacia as named by Ptolemy, starting from the northernmost ones, are as follows. First, the Anartes, the Teurisci and the Coertoboci/Costoboci. To the south of them are the Buredeense (Buri/Burs), the Cotenses/Cotini and then the Albocenses, the Potulatenses and the Sense, while the southernmost were the Saldenses, the Ciaginsi and the Piephigi. To the south of them were Predasenses/Predavenses, the Rhadacenses/Rhatacenses, the Caucoenses (Cauci) and Biephi.[90] Twelve out of these fifteen tribes listed by Ptolemy are ethnic Dacians,[95] and three are Celts: Anarti, Teurisci, and Cotenses.[95] There are also previous brief mentions of other Getae or Dacian tribes on the left and right banks of the Danube, or even in Transylvania, to be added to the list of Ptolemy. Among these other tribes are the Trixae, Crobidae and Appuli.[90]

Some peoples inhabiting the region generally described in Roman times as "Dacia" were not ethnic Dacians.[96] The true Dacians were a people of Thracian descent. German elements (Daco-Germans), Celtic elements (Daco-Celtic) and Iranian elements (Daco-Sarmatian) occupied territories in the north-west and north-east of Dacia.[97][98][96] This region covered roughly the same area as modern Romania plus Bessarabia (Republic of Moldova) and eastern Galicia (south-west Ukraine), although Ptolemy places Moldavia and Bessarabia in Sarmatia Europaea, rather than Dacia.[99] After the Dacian Wars (AD 101–6), the Romans occupied only about half of the wider Dacian region. The Roman province of Dacia covered just western Wallachia as far as the Limes Transalutanus (East of the river Alutus, or Olt) and Transylvania, as bordered by the Carpathians.[100]

The impact of the Roman conquest on these people is uncertain. One hypothesis was that they were effectively eliminated. An important clue to the character of Dacian casualties is offered by the ancient sources Eutropius and Crito. Both speak about men when they describe the losses suffered by the Dacians in the wars. This suggests that both refer to losses due to fighting, not due to a process of extermination of the whole population.[101] A strong component of the Dacian army, including the Celtic Bastarnae and the Germans, had withdrawn rather than submit to Trajan.[102] Some scenes on Trajan's Column represent acts of obedience of the Dacian population, and others show the refugee Dacians returning to their own places.[103] Dacians trying to buy amnesty are depicted on Trajan's Column (one offers to Trajan a tray of three gold ingots).[104] Alternatively, a substantial number may have survived in the province, although were probably outnumbered by the Romanised immigrants.[105] Cultural life in Dacia became very mixed and decidedly cosmopolitan because of the colonial communities. The Dacians retained their names and their own ways in the midst of the newcomers, and the region continued to exhibit Dacian characteristics.[106] The Dacians who survived the war are attested as revolting against the Roman domination in Dacia at least twice, in the period of time right after the Dacian Wars, and in a more determined manner in 117 AD.[107] In 158 AD, they revolted again, and were put down by M. Statius Priscus.[108] Some Dacians were apparently expelled from the occupied zone at the end of each of the two Dacian Wars or otherwise emigrated. It is uncertain where these refugees settled. Some of these people might have mingled with the existing ethnic Dacian tribes beyond the Carpathians (the Costoboci and Carpi).

After Trajan's conquest of Dacia, there was recurring trouble involving Dacian groups excluded from the Roman province, as finally defined by Hadrian. By the early third century the "Free Dacians", as they were earlier known, were a significantly troublesome group, then identified as the Carpi, requiring imperial intervention on more than one occasion.[109] In 214 Caracalla dealt with their attacks. Later, Philip the Arab came in person to deal with them; he assumed the triumphal title Carpicus Maximus and inaugurated a new era for the province of Dacia (July 20, 246). Later both Decius and Gallienus assumed the titles Dacicus Maximus. In 272, Aurelian assumed the same title as Philip.[109]

In about 140 AD, Ptolemy lists the names of several tribes residing on the fringes of the Roman Dacia (west, east and north of the Carpathian range), and the ethnic picture seems to be a mixed one. North of the Carpathians are recorded the Anarti, Teurisci and Costoboci.[110] The Anarti (or Anartes) and the Teurisci were originally probably Celtic peoples or mixed Dacian-Celtic.[98] The Anarti, together with the Celtic Cotini, are described by Tacitus as vassals of the powerful Quadi Germanic people.[111] The Teurisci were probably a group of Celtic Taurisci from the eastern Alps. However, archaeology has revealed that the Celtic tribes had originally spread from west to east as far as Transylvania, before being absorbed by the Dacians in the 1st century BC.[112][113]

Costoboci

[edit]The main view is that the Costoboci were ethnically Dacian.[114] Others considered them a Slavic or Sarmatian tribe.[115][116] There was also a Celtic influence, so that some consider them a mixed Celtic and Thracian group that appear, after Trajan's conquest, as a Dacian group within the Celtic superstratum.[117] The Costoboci inhabited the southern slopes of the Carpathians.[118] Ptolemy named the Coestoboci (Costoboci in Roman sources) twice, showing them divided by the Dniester and the Peucinian (Carpathian) Mountains. This suggests that they lived on both sides of the Carpathians, but it is also possible that two accounts about the same people were combined.[118] There was also a group, the Transmontani, that some modern scholars identify as Dacian Transmontani Costoboci of the extreme north.[119][120] The name Transmontani was from the Dacians' Latin,[121] literally "people over the mountains". Mullenhoff identified these with the Transiugitani, another Dacian tribe north of the Carpathian mountains.[122]

Based on the account of Dio Cassius, Heather (2010) considers that Hasding Vandals, around 171 AD, attempted to take control of lands which previously belonged to the free Dacian group called the Costoboci.[123] Hrushevskyi (1997) mentions that the earlier widespread view that these Carpathian tribes were Slavic has no basis. This would be contradicted by the Coestobocan names themselves that are known from the inscriptions, written by a Coestobocan and therefore presumably accurately. These names sound quite unlike anything Slavic.[115] Scholars such as Tomaschek (1883), Schütte (1917) and Russu (1969) consider these Costobocian names to be Thraco-Dacian.[124][125][126] This inscription also indicates the Dacian background of the wife of the Costobocian king "Ziais Tiati filia Daca".[127] This indication of the socio-familial line of descent seen also in other inscriptions (i.e. Diurpaneus qui Euprepes Sterissae f(ilius) Dacus) is a custom attested since the historical period (beginning in the 5th century BC) when Thracians were under Greek influence.[128] It may not have originated with the Thracians, as it could be just a fashion borrowed from Greeks for specifying ancestry and for distinguishing homonymous individuals within the tribe.[129] Schütte (1917), Parvan, and Florescu (1982) pointed also to the Dacian characteristic place names ending in '–dava' given by Ptolemy in the Costoboci's country.[130][131]

Carpi

[edit]The Carpi were a sizeable group of tribes, who lived beyond the north-eastern boundary of Roman Dacia. The majority view among modern scholars is that the Carpi were a North Thracian tribe and a subgroup of the Dacians.[132] However, some historians classify them as Slavs.[133]According to Heather (2010), the Carpi were Dacians from the eastern foothills of the Carpathian range – modern Moldavia and Wallachia – who had not been brought under direct Roman rule at the time of Trajan's conquest of Transylvania Dacia. After they generated a new degree of political unity among themselves in the course of the third century, these Dacian groups came to be known collectively as the Carpi.[134]

The ancient sources about the Carpi, before 104 AD, located them on a territory situated between the western side of Eastern European Galicia and the mouth of the Danube.[135] The name of the tribe is homonymous with the Carpathian mountains.[119] Carpi and Carpathian are Dacian words derived from the root (s)ker- "cut" cf. Albanian karp "stone" and Sanskrit kar- "cut".[136][137]A quote from the 6th-century Byzantine chronicler Zosimus referring to the Carpo-Dacians (Greek: Καρποδάκαι, Latin: Carpo-Dacae), who attacked the Romans in the late 4th century, is seen as evidence of their Dacian ethnicity. In fact, Carpi/Carpodaces is the term used for Dacians outside of Dacia proper.[138]However, that the Carpi were Dacians is shown not so much by the form Καρποδάκαι in Zosimus as by their characteristic place-names in –dava, given by Ptolemy in their country.[139] The origin and ethnic affiliations of the Carpi have been debated over the years; in modern times they are closely associated with the Carpathian Mountains, and a good case has been made for attributing to the Carpi a distinct material culture, "a developed form of the Geto-Dacian La Tene culture", often known as the Poienesti culture, which is characteristic of this area.[140]

Physical characteristics

[edit]

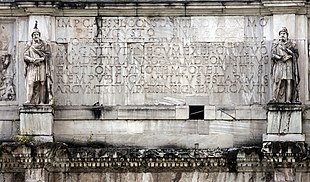

Dacians are represented in the statues surmounting the Arch of Constantine and on Trajan's Column.[1] The artist of the Column took some care to depict, in his opinion, a variety of Dacian people—from high-ranking men, women, and children to the near-savage. Although the artist looked to models in Hellenistic art for some body types and compositions, he does not represent the Dacians as generic barbarians.[141]

Classical authors applied a generalized stereotype when describing the "barbarians"—Celts, Scythians, Thracians—inhabiting the regions to the north of the Greek world.[142] In accordance with this stereotype, all these peoples are described, in sharp contrast to the "civilized" Greeks, as being much taller, their skin lighter and with straight light-coloured hair and blue eyes.[142] For instance, Aristotle wrote that "the Scythians on the Black Sea and the Thracians are straight-haired, for both they themselves and the environing air are moist";[143] according to Clement of Alexandria, Xenophanes described the Thracians as "ruddy and tawny".[142][144] On Trajan's column, Dacian soldiers' hair is depicted longer than the hair of Roman soldiers and they had trimmed beards.[145]

Body-painting was customary among the Dacians.[specify] It is probable that the tattooing originally had a religious significance.[146] They practiced symbolic-ritual tattooing or body painting for both men and women, with hereditary symbols transmitted up to the fourth generation.[147]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

In the absence of historical records written by the Dacians (and Thracians) themselves, analysis of their origins depends largely on the remains of material culture. On the whole, the Bronze Age witnessed the evolution of the ethnic groups which emerged during the Eneolithic period, and eventually the syncretism of both autochthonous and Indo-European elements from the steppes and the Pontic regions.[148] Various groups of Thracians had not separated out by 1200 BC,[148] but there are strong similarities between the ceramic types found at Troy and the ceramic types from the Carpathian area.[148] About the year 1000 BC, the Carpatho-Danubian countries were inhabited by a northern branch of the Thracians.[149] At the time of the arrival of the Scythians (c. 700 BC), the Carpatho-Danubian Thracians were developing rapidly towards the Iron Age civilization of the West. Moreover, the whole of the fourth period of the Carpathian Bronze Age had already been profoundly influenced by the first Iron Age as it developed in Italy and the Alpine lands. The Scythians, arriving with their own type of Iron Age civilization, put a stop to these relations with the West.[150] From roughly 500 BC (the second Iron Age), the Dacians developed a distinct civilization, which was capable of supporting large centralised kingdoms by the 1st century BC and the 1st century AD.[151]

Since the very first detailed account by Herodotus, Getae are acknowledged as belonging to the Thracians.[11] Still, they are distinguished from the other Thracians by particularities of religion and custom.[142] The first written mention of the name "Dacians" is in Roman sources, but classical authors are unanimous in considering them a branch of the Getae, a Thracian people known from Greek writings. Strabo specified that the Daci are the Getae who lived in the area towards the Pannonian plain (Transylvania), while the Getae proper gravitated towards the Black Sea coast (Scythia Minor).

Relations with Thracians

[edit]Since the writings of Herodotus in the 5th century BC,[11] Getae/Dacians are acknowledged as belonging to the Thracian sphere of influence. Despite this, they are distinguished from other Thracians by particularities of religion and custom.[142] Geto-Dacians and Thracians were kin people but they were not the same.[152] The differences from the southern Thracians or from the neighbouring Scythians were probably faint, as several ancient authors make confusions of identification with both groups.[142] Linguist Vladimir Georgiev says that based on the absence of toponyms ending in dava in Southern Bulgaria, the Moesians and Dacians (or as he calls them Daco-Mysians) couldn't be related to the Thracians.[153]

In the 19th century, Tomaschek considered a close affinity between the Besso-Thracians and Getae-Dacians, an original kinship of both people with Iranian peoples.[154] They are Aryan tribes, several centuries before Scolotes of the Pont and Sauromatae left the Aryan homeland and settled in the Carpathian chain, in the Haemus (Balkan) and Rhodope mountains.[154] The Besso-Thracians and Getae-Dacians separated very early from Aryans, since their language still maintains roots that are missing from Iranian and it shows non-Iranian phonetic characteristics (i.e. replacing the Iranian "l" with "r").[154]

Relations with Celts

[edit]

Geto-Dacians inhabited both sides of the Tisa River before the rise of the Celtic Boii, and again after the latter were defeated by the Dacians under king Burebista.[155] During the second half of the 4th century BC, Celtic cultural influence appears in the archaeological records of the middle Danube, Alpine region, and north-western Balkans, where it was part of the Middle La Tène material culture. This material appears in north-western and central Dacia, and is reflected especially in burials.[151] The Dacians absorbed the Celtic influence from the northwest in the early third century BC.[156] Archaeological investigation of this period has highlighted several Celtic warrior graves with military equipment. It suggests the forceful penetration of a military Celtic elite within the region of Dacia, now known as Transylvania, that is bounded on the east by the Carpathian range.[151] The archaeological sites of the third and second centuries BC in Transylvania revealed a pattern of co-existence and fusion between the bearers of La Tène culture and indigenous Dacians. These were domestic dwellings with a mixture of Celtic and Dacian pottery, and several graves in the Celtic style containing vessels of Dacian type.[151] There are some seventy Celtic sites in Transylvania, mostly cemeteries, but most if not all of them indicate that the native population imitated Celtic art forms that took their fancy, but remained obstinately and fundamentally Dacian in their culture.[156]

The Celtic Helmet from Ciumeşti, Satu Mare, Romania (northern Dacia), an Iron Age raven totem helmet, dated around the 4th century BC. A similar helmet is depicted on the Thraco-Celtic Gundestrup cauldron, being worn by one of the mounted warriors (detail tagged here). See also an illustration of Brennos wearing a similar helmet.Around 150 BC, La Tène material disappears from the area. This coincides with the ancient writings which mention the rise of Dacian authority. It ended the Celtic domination, and it is possible that Celts were driven out of Dacia. Alternatively, some scholars have proposed that the Transylvanian Celts remained, but merged into the local culture and thus ceased to be distinctive.[151][156]

Archaeological discoveries in the settlements and fortifications of the Dacians in the period of their kingdoms (1st century BC and 1st century AD) included imported Celtic vessels and others made by Dacian potters imitating Celtic prototypes, showing that relations between the Dacians and the Celts from the regions north and west of Dacia continued.[157] In present-day Slovakia, archaeology has revealed evidence for mixed Celtic-Dacian populations in the Nitra and Hron river basins.[158]

After the Dacians subdued the Celtic tribes, the remaining Cotini stayed in the mountains of Central Slovakia, where they took up mining and metalworking. Together with the original domestic population, they created the Puchov culture that spread into central and northern Slovakia, including Spis, and penetrated northeastern Moravia and southern Poland. Along the Bodrog River in Zemplin they created Celtic-Dacian settlements which were known for the production of painted ceramics.[158]

Relations with Greeks

[edit]Greek and Roman chroniclers record the defeat and capture of the Macedonian general Lysimachus in the 3rd century BC by the Getae (Dacians) ruled by Dromihete, their military strategy, and the release of Lysimachus following a debate in the assembly of the Getae.

Relations with Persians

[edit]Herodotus says: "before Darius reached the Danube, the first people he subdued were the Getae, who believed that they never die".[11] It is possible that the Persian expedition and the subsequent occupation may have altered the way in which the Getae expressed the immortality belief. The influence of thirty years of Achaemenid presence may be detected in the emergence of an explicit iconography of the "Royal Hunt" that influenced Dacian and Thracian metalworkers, and of the practice of hawking by their upper class.[citation needed]

Relations with Scythians

[edit]Agathyrsi Transylvania

[edit]The Scythians' arrival in the Carpathian mountains is dated to 700 BC.[159] The Agathyrsi of Transylvania had been mentioned by Herodotus (fifth century BC),[160] who regarded them as not a Scythian people, but closely related to them. In other respects, their customs were close to those of the Thracians.[161] The Agathyrsi were completely denationalized at the time of Herodotus and absorbed by the native Thracians.[162][159]

The opinion that the Agathyrsi were almost certainly Thracians results also from the writings preserved by Stephen of Byzantium, who explains that the Greeks called the Trausi the Agathyrsi, and we know that the Trausi lived in the Rhodope Mountains. Certain details from their way of life, such as tattooing, also suggest that the Agathyrsi were Thracians. Their place was later taken by the Dacians.[163] That the Dacians were of Thracian stock is not in doubt, and it is safe to assume that this new name also encompassed the Agathyrsi, and perhaps other neighbouring Thracian people as well, as a result of some political upheaval.[163]

Relations with Germanic tribes

[edit]

The Goths, a confederation of east German peoples, arrived in southern Ukraine no later than 230.[164] During the next decade, a large section of them moved down the Black Sea coast and occupied much of the territory north of the lower Danube.[164] The Goths' advance towards the area north of the Black Sea involved competing with the indigenous population of Dacian-speaking Carpi, as well as indigenous Iranian-speaking Sarmatians and Roman garrison forces.[165] The Carpi, often called "Free Dacians", continued to dominate the anti-Roman coalition made up of themselves, Taifali, Astringi, Vandals, Peucini, and Goths until 248, when the Goths assumed the hegemony of the loose coalition.[166] The first lands taken over by the Thervingi Goths were in Moldavia, and only during the fourth century did they move in strength down into the Danubian plain.[167] The Carpi found themselves squeezed between the advancing Goths and the Roman province of Dacia.[164] In 275 AD, Aurelian surrendered the Dacian territory[clarification needed] to the Carpi and the Goths.[168] Over time, Gothic power in the region grew, at the Carpi's expense. The Germanic-speaking Goths replaced native Dacian-speakers as the dominant force around the Carpathian mountains.[169] Large numbers of Carpi, but not all of them, were admitted into the Roman empire in the twenty-five years or so after 290 AD.[170] Despite this evacuation of the Carpi around 300 AD, considerable groups of the natives (non-Romanized Dacians, Sarmatians and others) remained in place under Gothic domination.[171]

In 330 AD, the Gothic Thervingi contemplated moving to the Middle Danube region,[citation needed] and from 370 relocated with their fellow Gothic Greuthungi to new homes in the Roman Empire.[170] The Ostrogoths were still more isolated, but even the Visigoths preferred to live among their own kind. As a result, the Goths settled in pockets. Finally, although Roman towns continued on a reduced level, there is no question as to their survival.[167]

In 336 AD, Constantine took the title Dacicus Maximus 'great victor in Dacia', implying at least partial reconquest of Trajan Dacia.[172] In an inscription of 337, Constantine was commemorated officially as Germanicus Maximus, Sarmaticus, Gothicus Maximus, and Dacicus Maximus, meaning he had defeated the Germans, Sarmatians, Goths, and Dacians.[173]

Dacian kingdoms

[edit]

Dacian polities arose as confederacies that included the Getae, the Daci, the Buri, and the Carpi[dubious – discuss] (cf. Bichir 1976, Shchukin 1989),[155] united only periodically by the leadership of Dacian kings such as Burebista and Decebal. This union was both military-political and ideological-religious[155] on ethnic basis. The following are some of the attested Dacian kingdoms:

The kingdom of Cothelas, one of the Getae, covered an area near the Black Sea, between northern Thrace and the Danube, today Bulgaria, in the 4th century BC.[174] The kingdom of Rubobostes controlled a region in Transylvania in the 2nd century BC.[175] Gaius Scribonius Curio (proconsul 75–73 BC) campaigned successfully against the Dardani and the Moesi, becoming the first Roman general to reach the river Danube with his army.[176] His successor, Marcus Licinius Lucullus, brother of the famous Lucius Lucullus, campaigned against the Thracian Bessi tribe and the Moesi, ravaging the whole of Moesia, the region between the Haemus (Balkan) mountain range and the Danube. In 72 BC, his troops occupied the Greek coastal cities of Scythia Minor (the modern Dobrogea region in Romania and Bulgaria), which had sided with Rome's Hellenistic arch-enemy, king Mithridates VI of Pontus, in the Third Mithridatic War.[177] Greek geographer Strabo claimed that the Dacians and Getae had been able to muster a combined army of 200,000 men during Strabo's era, the time of Roman emperor Augustus.[178]

The kingdom of Burebista

[edit]The Dacian kingdom reached its maximum extent under king Burebista (ruled 82 – 44 BC). The capital of the kingdom was possibly the city of Argedava, also called Sargedava in some historical writings, situated close to the river Danube. The kingdom of Burebista extended south of the Danube, in what is today Bulgaria, and the Greeks believed their king was the greatest of all Thracians.[179][better source needed] During his reign, Burebista transferred the Geto-Dacians' capital from Argedava to Sarmizegetusa.[180][181] For at least one and a half centuries, Sarmizegethusa was the Dacian capital, reaching its peak under king Decebalus. Burebista annexed the Greek cities on the Pontus.(55–48 BC).[182] Augustus wanted to avenge the defeat of Gaius Antonius Hybrida at Histria (Sinoe) 32 years before, and to recover the lost standards. These were held in a powerful fortress called Genucla (Isaccea, near modern Tulcea, in the Danube delta region of Romania), controlled by Zyraxes, the local Getan petty king.[183] The man selected for the task was Marcus Licinius Crassus, grandson of Crassus the triumvir, and an experienced general at 33 years of age, who was appointed proconsul of Macedonia in 29 BC.[184]

The kingdom of Decebalus 87 – 106

[edit]By the year AD 100, more than 400,000 square kilometres were dominated by the Dacians, who numbered two million.[b] Decebalus was the last king of the Dacians, and despite his fierce resistance against the Romans was defeated, and committed suicide rather than being marched through Rome in a triumph as a captured enemy leader.

Conflict with Rome

[edit]Burebista's Dacian state was powerful enough to threaten Rome, and Caesar contemplated campaigning against the Dacians.[citation needed] Despite this, the formidable Dacian power under Burebista lasted only until his death in 44 BC. The subsequent division of Dacia continued for about a century until the reign of Scorilo. This was a period of only occasional attacks on the Roman Empire's border, with some local significance.[185]

The unifying actions of the last Dacian king Decebalus (ruled 87–106 AD) were seen as dangerous by Rome. Despite the fact that the Dacian army could now gather only some 40,000 soldiers,[185] Decebalus' raids south of the Danube proved unstoppable and costly. In the Romans' eyes, the situation at the border with Dacia was out of control, and Emperor Domitian (ruled 81 to 96 AD) tried desperately to deal with the danger through military action. But the outcome of Rome's disastrous campaigns into Dacia in AD 86 and AD 88 pushed Domitian to settle the situation through diplomacy.[185]

Emperor Trajan (ruled 98–117 AD) opted for a different approach and decided to conquer the Dacian kingdom, partly in order to seize its vast gold mines wealth. The effort required two major wars (the Dacian Wars), one in 101–102 AD and the other in 105–106 AD. Only fragmentary details survive of the Dacian war: a single sentence of Trajan's own Dacica; little more of the Getica written by his doctor, T. Statilius Crito; nothing whatsoever of the poem proposed by Caninius Rufus (if it was ever written), Dio Chrysostom's Getica or Appian's Dacica. Nonetheless, a reasonable account can be pieced together.[186]

In the first war, Trajan invaded Dacia by crossing the river Danube with a boat-bridge and inflicted a crushing defeat on the Dacians at the Second Battle of Tapae in 101 AD. The Dacian king Decebalus was forced to sue for peace. Trajan and Decebalus then concluded a peace treaty which was highly favourable to the Romans. The peace agreement required the Dacians to cede some territory to the Romans and to demolish their fortifications. Decebalus' foreign policy was also restricted, as he was prohibited from entering into alliances with other tribes.

However, both Trajan and Decebalus considered this only a temporary truce and readied themselves for renewed war. Trajan had Greek engineer Apollodorus of Damascus construct a stone bridge over the Danube river, while Decebalus secretly plotted alliances against the Romans.[citation needed] In 105, Trajan crossed the Danube river and besieged Decebalus' capital, Sarmizegetusa, but the siege failed because of Decebalus' allied tribes. However, Trajan was an optimist. He returned with a newly constituted army and took Sarmizegetusa by treachery. Decebalus fled into the mountains, but was cornered by pursuing Roman cavalry. Decebalus committed suicide rather than being captured by the Romans and be paraded as a slave, then be killed. The Roman captain took his head and right hand to Trajan, who had them displayed in the Forums. Trajan's Column in Rome was constructed to celebrate the conquest of Dacia.

The Roman people hailed Trajan's triumph in Dacia with the longest and most expensive celebration in their history, financed by a part of the gold taken from the Dacians.[citation needed] For his triumph, Trajan gave a 123-day festival (ludi) of celebration, in which approximately 11,000 animals were slaughtered and 11,000 gladiators fought in combats. This surpassed Emperor Titus's celebration in AD 70, when a 100-day festival included 3,000 gladiators and 5,000 to 9,000 wild animals.[187]

Roman rule

[edit]Only about half part of Dacia then became a Roman province,[188] with a newly built capital at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa, 40 km away from the site of Old Sarmisegetuza Regia, which was razed to the ground. The name of the Dacians' homeland, Dacia, became the name of a Roman province, and the name Dacians was used to designate the people in the region.[189] Roman Dacia, also Dacia Traiana or Dacia Felix, was a province of the Roman Empire from 106 to 271 or 275 AD.[190][unreliable source?][191][192] Its territory consisted of eastern and southeastern Transylvania, and the regions of Banat and Oltenia (located in modern Romania).[190] Dacia was organised from the beginning as an imperial province, and remained so throughout the Roman occupation.[193] It was one of the empire's Latin provinces; official epigraphs attest that the language of administration was Latin.[194] Historian estimates of the population of Roman Dacia range from 650,000 to 1,200,000.[195]

Dacians that remained outside the Roman Empire after the Dacian wars of AD 101–106 had been named Dakoi prosoroi (Latin Daci limitanei), "neighbouring Dacians".[22] Modern historians use the generic name "Free Dacians" or Independent Dacians.[196][125][124] The tribes Daci Magni (Great Dacians), Costoboci (generally considered a Dacian subtribe), and Carpi remained outside the Roman empire, in what the Romans called Dacia Libera (Free Dacia).[189] By the early third century the "Free Dacians" were a significantly troublesome group, by now identified as the Carpi.[196] Bichir argues that the Carpi were the most powerful of the Dacian tribes who had become the principal enemy of the Romans in the region.[197] In 214 AD, Caracalla campaigned against the Free Dacians.[198] There were also campaigns against the Dacians recorded in 236 AD.[199]

Roman Dacia was evacuated by the Romans under emperor Aurelian (ruled 271–5 AD). Aurelian made this decision on account of counter-pressures on the Empire there caused by the Carpi, Visigoths, Sarmatians, and Vandals; the lines of defence needed to be shortened, and Dacia was deemed not defensible given the demands on available resources. Roman power in Thracia rested mainly with the legions stationed in Moesia. The rural nature of Thracia's populations, and the distance from Roman authority, encouraged the presence of local troops to support Moesia's legions. Over the next few centuries, the province was periodically and increasingly attacked by migrating Germanic tribes. The reign of Justinian saw the construction of over 100 legionary fortresses to supplement the defence. Thracians in Moesia and Dacia were Romanized, while those within the Byzantine empire were their Hellenized descendants that had mingled with the Greeks.

After the Aurelian Retreat

[edit]

Roman Dacia was never a uniformly or fully Romanized area. Post-Aurelianic Dacia fell into three divisions: the area along the river, usually under some type of Roman administration even if in a highly localized form; the zone beyond this area, from which Roman military personnel had withdrawn, leaving a sizable population behind that was generally Romanized; and finally what is now the northern parts of Moldavia, Crisana, and Maramures, which were never occupied by the Romans. These last areas were always peripheral to the Roman province, not militarily occupied but nonetheless influenced by Rome as part of the Roman economic sphere. Here lived the free, unoccupied Carpi, often called "Free Dacians".[167]

The Aurelian retreat was a purely military decision to withdraw the Roman troops to defend the Danube. The inhabitants of the old province of Dacia displayed no awareness of impending dissolution. There were no sudden flights or dismantling of property.[168] It is not possible to discern how many civilians followed the army out of Dacia; it is clear that there was no mass emigration, since there is evidence of continuity of settlement in Dacian villages and farms; the evacuation may not at first have been intended to be a permanent measure.[168] The Romans left the province, but they didn't consider that they lost it.[168] Dobrogea was not abandoned at all, but continued as part of the Roman Empire for over 350 years.[200] As late as AD 300, the tetrarchic emperors had resettled tens of thousands of Dacian Carpi inside the empire, dispersing them in communities the length of the Danube, from Austria to the Black Sea.[201]

Society

[edit]

Dacians were divided into two classes: the aristocracy (tarabostes) and the common people (comati). Only the aristocracy had the right to cover their heads, and wore a felt hat. The common people, who comprised the rank and file of the army, the peasants and artisans, might have been called capillati in Latin. Their appearance and clothing can be seen on Trajan's Column.

Occupations

[edit]

The chief occupations of the Dacians were agriculture, apiculture, viticulture, livestock, ceramics and metalworking. They also worked the gold and silver mines of Transylvania. At Pecica, Arad, a Dacian workshop was discovered, along with equipment for minting coins and evidence of bronze, silver, and iron-working that suggests a broad spectrum of smithing.[202] Evidence for the mass production of iron is found on many Dacian sites, indicating guild-like specialization.[202] Dacian ceramic manufacturing traditions continue from the pre-Roman to the Roman period, both in provincial and unoccupied Dacia, and well into the fourth and even early fifth centuries.[203] They engaged in considerable external trade, as is shown by the number of foreign coins found in the country (see also Decebalus Treasure). On the northernmost frontier of "free Dacia", coin circulation steadily grew in the first and second centuries, with a decline in the third and a rise again in the fourth century; the same pattern as observed for the Banat region to the southwest. What is remarkable is the extent and increase in coin circulation after Roman withdrawal from Dacia, and as far north as Transcarpathia.[204]

Currency

[edit]

The first coins produced by the Geto-Dacians were imitations of silver coins of the Macedonian kings Philip II and Alexander the Great. Early in the 1st century BC, the Dacians replaced these with silver denarii of the Roman Republic, both official coins of Rome exported to Dacia, as well as locally made imitations of them. The Roman province Dacia is represented on the Roman sestertius coin as a woman seated on a rock, holding an aquila, a small child on her knee. The aquila holds ears of grain, and another small child is seated before her holding grapes.

Construction

[edit]Dacians had developed the murus dacicus (double-skinned ashlar-masonry with rubble fill and tie beams) characteristic to their complexes of fortified cities, like their capital Sarmizegetusa Regia in what is today Hunedoara County, Romania.[202] This type of wall has been discovered not only in the Dacian citadel of the Orastie mountains, but also in those at Covasna, Breaza near Făgăraș, Tilișca near Sibiu, Căpâlna in the Sebeș valley, Bănița not far from Petroșani, and Piatra Craivii to the north of Alba Iulia.[205] The degree of their urban development was displayed on Trajan's Column and in the account of how Sarmizegetusa Regia was defeated by the Romans. The Romans were given by treachery the locations of aqueducts and pipelines of the Dacian capital, only after destroying the water supply being able to end the long siege of Sarmisegetuza.

Material culture

[edit]According to Romanian nationalist archaeology, the cradle of the Dacian culture is considered to be north of the Danube towards the Carpathian mountains, in the historical Romanian province of Muntenia. It is identified as an evolution of the Iron Age Basarabi culture. Such narrative believe that the earlier Iron Age Basarabi evidence in the northern lower Danube area connects to the iron-using Ferigile-Birsesti group. This is an archaeological manifestation of the historical Getae who, along with the Agathyrsae, are one of a number of tribal formations recorded by Herodotus.[160][206] In archaeology, "free Dacians" are attested by the Puchov culture (in which there are Celtic elements) and Lipiţa culture to the east of the Carpathians.[207] The Lipiţa culture has a Dacian/North Thracian origin.[208] [209] This North Thracian population was dominated by strong Celtic influences, or had simply absorbed Celtic ethnic components.[210] Lipiţa culture has been linked to the Dacian tribe of Costoboci.[211][212]These standpoints are highly problematic, as there is no linear continuity between aforementioned cultures. in reality, the creation of the Dacian ethnos was foreshadowed by migratory movements from the lower Danube region following the collapse of the Celtic cultural circle c. 300 BC (The grave with a helmet from Ciumeşti – 50 years from its discovery. Comments on the greaves. 2. The Padea-Panagjurski kolonii group in Transylvania. Old and new discoveries)

Specific Dacian material culture includes: wheel-turned pottery that is generally plain but with distinctive elite wares, massive silver dress fibulae, precious metal plate, ashlar masonry, fortifications, upland sanctuaries with horseshoe-shaped precincts, and decorated clay heart altars at settlement sites. Among many discovered artifacts, the Dacian bracelets stand out, depicting their cultural and aesthetic sense.[202] There are difficulties correlating funerary monuments chronologically with Dacian settlements; a small number of burials are known, along with cremation pits, and isolated rich burials as at Cugir.[202] Dacian burial ritual continued under Roman occupation and into the post-Roman period.[213]

Language

[edit]The Dacians are generally considered to have been Thracian speakers, representing a cultural continuity from earlier Iron Age communities.[83] Some historians and linguists consider Dacian language to be a dialect of or the same language as Thracian.[142][214] The vocalism and consonantism differentiate the Dacian and Thracian languages.[215] Others consider that Dacian and Illyrian form regional varieties (dialects) of a common language. (Thracians inhabited modern southern Bulgaria and northern Greece. Illyrians lived in modern Albania, Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia.)

The ancient languages of these people became extinct, and their cultural influence highly reduced, after the repeated invasions of the Balkans by Celts, Huns, Goths, and Sarmatians, accompanied by persistent hellenization, romanisation and later slavicisation. Therefore, in the study of the toponomy of Dacia, one must take account of the fact that some place-names were taken by the Slavs from as yet unromanised Dacians.[216] A number of Dacian words are preserved in ancient sources, amounting to about 1150 anthroponyms and 900 toponyms, and in Discorides some of the rich plant lore of the Dacians is preserved along with the names of 42 medicinal plants.[13]

Symbols

[edit]The Dacians knew about writing.[217][218][219] Permanent contacts with the Graeco-Roman world had brought the use of the Greek and later the Latin alphabet.[220] It is also certainly not the case that writing with Greek and Latin letters and knowledge of Greek and Latin were known in all the settlements scattered throughout Dacia, but there is no doubt about the existence of such knowledge in some circles of Dacian society.[221] However, the most revealing discoveries concerning the use of the writing by the Dacians occurred in the citadels on the Sebes mountains.[220] Some groups of letters from stone blocks at Sarmisegetuza might express personal names; these cannot now be read because the wall is ruined, and because it is impossible to restore the original order of the blocks in the wall.[222]

Religion

[edit]

Dacian religion was considered by the classic sources as a key source of authority, suggesting to some that Dacia was a predominantly theocratic state led by priest-kings. However, the layout of the Dacian capital Sarmizegethusa indicates the possibility of co-rulership, with a separate high king and high priest.[155] Ancient sources recorded the names of several Dacian high priests (Deceneus, Comosicus and Vezina) and various orders of priests: "god-worshipers", "smoke-walkers" and "founders".[155] Both Hellenistic and Oriental influences are discernible in the religious background, alongside chthonic and solar motifs.[155]

According to Herodotus' account of the story of Zalmoxis or Zamolxis,[11] the Getae (speaking the same language as the Dacians and the Thracians, according to Strabo) believed in the immortality of the soul, and regarded death as merely a change of country. Their chief priest held a prominent position as the representative of the supreme deity, Zalmoxis, who is called also Gebeleizis by some among them.[11][225] Strabo wrote about the high priest of King Burebista Deceneus: "a man who not only had wandered through Egypt, but also had thoroughly learned certain prognostics through which he would pretend to tell the divine will; and within a short time he was set up as god (as I said when relating the story of Zamolxis)."[226]

Гот Иордан в своей «Гетике» ( «Происхождение и деяния готов ») также рассказывает о Деценее, первосвященнике, и считал даков народом, родственным готам. Помимо Залмоксиса, даки верили в других божеств, таких как Гебелейзис, бог грозы и молний, возможно, связанный с фракийским богом Зибельтиурдосом . [227] Его изображали красивым мужчиной, иногда с бородой. Позднее Гебелейзиса приравнивали к Залмоксису как к одному и тому же богу. Согласно Геродоту, Гебелеизис (*Зебелеизис/Гебелеизис, который упоминается только Геродотом) — это просто еще одно имя Залмоксиса. [228] [11] [229] [230]

Другим важным божеством была Бендис , богиня луны и охоты. [231] По указу оракула Додоны , который требовал от афинян предоставить землю под святыню или храм, ее культ был введен в Аттику переселенцами-фракийскими жителями, [с] и, хотя фракийские и афинские процессии оставались отдельными, и культ, и праздник стали настолько популярными, что во времена Платона (ок. 429–13 до н. э.) их празднества были натурализованы как официальная церемония афинского города-государства, называемого Бендидия . [д]

Известные дакийские теонимы включают Залмоксис , Гебелейзис и Дарзалас . [232] [и] Гебелейзис, вероятно, является родственником фракийского бога Зибельтиурдоса (также Збелсурдоса , Зибельтурдоса ), обладателя молний и молний. Дерзелас (также Дарзалас ) был хтоническим богом здоровья и жизненной силы человека. Языческая религия просуществовала в Дакии дольше, чем в других частях империи; Христианство не продвинулось вперед до пятого века. [168]

Керамика

[ редактировать ]

В поселении Окница-Вылча были обнаружены фрагменты керамики с различными «надписями» латинскими и греческими буквами, вырезанными до и после обжига. [233] Надпись содержит слово Basileus (Βασιλεύς по-гречески, что означает «царь») и, по-видимому, была написана до того, как сосуд был закален огнем. [234] Другие надписи содержат имя царя, предположительно Тимарка. [234] и латинские группы букв (BVR, REB). [235] БВР указывает на название племени или союза племен, даков-буридавенси, живших в Буридаве и упомянутых Птолемеем во втором веке нашей эры под именем Буридавенсиои. [236]

Одежда и наука

[ редактировать ]Типичную одежду даков, как мужчин, так и женщин, можно увидеть на колонне Траяна . [146]

Дион Златоуст описывал даков как натурфилософов . [237]

Война

[ редактировать ]История дакийских войн начинается с ок. С 10 века до нашей эры до 2 века нашей эры в регионе, который древнегреческие и латинские историки обычно называют Дакией. Речь идет о вооруженных конфликтах дакийских племен и их королевств на Балканах. Помимо конфликтов между даками и соседними народами и племенами, между даками были зафиксированы многочисленные войны.

Оружие

[ редактировать ]Оружием, которое больше всего ассоциировалось с дакийскими силами, сражавшимися против армии Траяна во время его вторжений в Дакию, был фалькс , однолезвийное оружие, похожее на косу. Фалькс мог нанести ужасные раны противникам, легко выводя из строя или убивая тяжелобронированных римских легионеров, с которыми они столкнулись. Это оружие, в большей степени, чем любой другой фактор, вынудило римскую армию принять на вооружение ранее неиспользованное или модифицированное оборудование, чтобы оно соответствовало условиям поля битвы при Даках. [238]

Известные личности

[ редактировать ]Это список нескольких важных даков или лиц частично дакийского происхождения.

- Залмоксис , полулегендарный социальный и религиозный реформатор, в конечном итоге обожествленный гетами и даками и считавшийся единственным истинным богом .

- Золтес

- Буребиста — царь Дакии, 70–44 гг. до н.э., объединивший под своей властью фракийцев на большой территории, от нынешней Моравии на западе, до реки Южный Буг ( Украина ) на востоке, и от Северных Карпат до Южных Дионисополь . Греки считали его первым и величайшим царем Фракии. [179] [ нужен лучший источник ]

- Децебал , царь Дакии, который в конечном итоге потерпел поражение от войск Траяна .

- Диегис был вождем даков, полководцем и братом Децебала и его представителем на мирных переговорах, проходивших с Домицианом (89 г. н.э.).

Румынские культурные влияния

[ редактировать ]

Изучение даков, их культуры, общества и религии не является чисто предметом древней истории, но имеет современные последствия в контексте румынского национализма . Позиции, занятые по спорному вопросу о происхождении румын и о том, в какой степени современные румыны произошли от даков, могут иметь современные политические последствия. Например, правительство Николае Чаушеску заявляло о непрерывной преемственности дакийско-румынского государства от короля Буребисты до самого Чаушеску. [239] Правительство Чаушеску заметно отметило предполагаемое 2050-летие со дня основания «единой и централизованной» страны, которая должна была стать Румынией, по этому случаю был снят исторический фильм «Буребиста» .

«Утки выходят из грузовиков». – Игра слов на румынском языке, связанная с неправильным переводом (утка и грузовик звучат как dac и trac, этнонимы даков и фракийцев). [240]

См. также

[ редактировать ]Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ В книге Диоскорида (известной на английском языке под латинским названием De Materia Medica «О медицинских материалах») все дакийские названия растений предваряются буквой Δάκοι Dakoi , т.е. Δάκοι Dakoi προποδιλα. Латинское Daci propodila «Даки проподила»

- ^ De Imperatoribus Romanis Проверено 8 ноября 2007 г. «В 88 году римляне возобновили наступление. Римские войска теперь возглавил полководец Теттий Юлиан. Битва снова произошла при Тапах, но на этот раз римляне победили даков. Боясь попасть в ловушку, Юлиан оставил его планы покорить Сармизегетузу и одновременно Децебал просили мира. Сначала Домициан отказался от этой просьбы, но после того, как он потерпел поражение в войне в Паннонии против маркоманов (германского племени), император был вынужден принять. мир».

- ^ Обширное обсуждение того, является ли эта дата 429 или 413 годом до нашей эры, было рассмотрено и недавно проанализировано в Кристофере Плано, «Дата въезда Бендиса в Аттику», The Classical Journal 96.2 (декабрь 2000: 165–192). Плано предлагает реконструкцию надписи с упоминанием первого вступления, стр.

- ^ Фрагментарные надписи V века, в которых зафиксированы формальные указы, касающиеся формальных аспектов культа Бендиса, воспроизведены в Planeaux 2000:170f.

- ^ Гарри Терстон Пек, Словарь классических древностей Арфистов (1898), (Залмоксис) или Замолксис (Замолксис). Говорят, что он был назван так из-за медвежьей шкуры (залмос), в которую его одевали, как только он родился. Согласно легенде, распространенной среди греков на Геллеспонте, он был гетаном, который был рабом Пифагора на Самосе, но был освобожден и приобрел не только большое богатство, но и большие запасы знаний от Пифагора и от Египтяне, которых он посетил в ходе своих путешествий. Он вернулся среди гетов, познакомив их с цивилизацией и религиозными идеями, которые он приобрел, особенно относительно бессмертия души. Геродот, однако, подозревает, что он был коренным гетанским божеством (Herod.iv. 95).

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Jump up to: а б Вестропп 2003 , с. 104.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Страбон и 20 г. н.э. , VII 3,12.

- ^ Дионисий Перигет , греческий и латынь , Том 1 , Libraria Weidannia, 1828, стр. 145

- ^ Уолдман и Мейсон 2006 , с. 205 «Даки были народом современной Румынии, подгруппой фракийцев, которые имели значительные контакты с римлянами с середины второго века до нашей эры до конца третьего века нашей эры»

- ^ Jump up to: а б Нандрис 1976 , с. 731.

- ^ Гусовска 1998 , стр. 187.

- ^ Кембриджская древняя история (том 10) (2-е изд.). Издательство Кембриджского университета. 1996. Дж. Дж. Уилкс упоминает «гетов Добруджи, родственных дакам»; (стр. 562)

- ^ Jump up to: а б Фишер 2003 , с. 570.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Розетти 1982 , с. 5.

- ^ Аппиан и 165 г. н. э. , Преф. 14–15 апреля, цитируется у Миллара (2004 , стр. 189): «Геты за Дунаем, которых они называют даками»

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г Геродот и 440 г. до н.э. , 4.93–4.97.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Фол 1996 , с. 223.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Нандрис 1976 , с. 730: Страбон и Трог Помпей «Даки также являются вассалами гетов».

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кроссланд и Бордман 1982 , с. 837.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Рёслер 1864 , с. 89.

- ^ Zumpt & Zumpt 1852 , стр. 140 и 175

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Ван Ден Гейн 1886 , с. 170.

- ^ Эверитт 2010 , с. 151.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Банбери 1979 , с. 150.

- ^ Олтеан 2007 , стр. 44.

- ^ Банбери 1979 , с. 151.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Гарашанин, Бенац (1973) 243

- ^ Парван, Вульпе и Вульпе 2002 , стр. 158.

- ^ Томашек 1883 , с. 397.

- ^ Малвин 2002 , с. 59: «...Надгробная надпись из Аквинкума гласит: M. Secundi Genalis domo Cl. Agrip /pina/ negotiat. Dacisco. Это датируется вторым веком и предполагает присутствие некоторых дакийских торговцев в Паннонии...»

- ^ Петолеску 2000 , с. 163: «...отец incom[pa-] rabili, decep [to] Daciscis in belloproclio...»

- ^ Гиббон 2008 , с. 313: «...Аврелиан называет этих солдат Хиберами, Рипариенсами, Кастрианами и Дакисками» согласно «Вописку в Historia Augusta XXVI 38»

- ^ Кефарт 1949 , с. 28: Персы знали, что дахи и другие массагеты были родственниками жителей Скифии к западу от Каспийского моря.

- ^ Чакраберти 1948 , с. 34: «Даса или Дасью Ригведы - это Даха Авесты, Дачи римлян, Дакаой (хинди Дакку) греков»

- ^ Плиний (Старший) и Рэкхэм 1971 , с. 375.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Уайт 1991 , с. 239.

- ^ Грумеза 2009 .

- ^ Sidebottom 2007 , с. 6.

- ^ Флоров 2001 , с. 66.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Папазоглу 1978 , с. 434.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Барбулеску и Наглер 2005 , стр. 68.

- ^ Сержант Бернард (1991 г.). «Индоевропейские этнозоонимы» . Диалоги древней истории . 17 (2): 19. doi : 10.3406/dha.1991.1932 .

- ^ Врачу 1980 , стр. 45.

- ^ Лемни и Йорга 1984 , стр. 210.

- ^ Тойнби 1961 , с. 435.

- ^ Crossland & Boardman 1982 , с. 8375.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Томашек 1883 , с. 404.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Палига 1999 , с. 77.

- ^ Эйслер 1951 , с. 136.

- ^ Парван, Вульпе и Вульпе 2002 , стр. 149.

- ^ Алеку-Кэлушита 1992 , стр. 19.

- ^ Эйслер 1951 , с. 33.

- ^ Элиаде 1995 , с. 12.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Падани, Виктор (1963). Стоматологическая Венгрия (на венгерском языке). Редакционная Трансильвания.

- ^ Фокс 2001 , стр. 420–421.

- ^ Руссо 1967 , с. 133.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Элиаде 1995 , с. 11.

- ^ Эйслер 1951 , с. 137.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Элиаде 1995 , с. 13.

- ^ Жанмэр 1975 , с. 540.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Эйслер 1951 , с. 144.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Элиаде 1995 , с. 15.

- ^ Замботти 1954 , с. 184, рис. 13-14, 16.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Элиаде 1995 , с. 23.

- ^ Элиаде 1995 , с. 27.

- ^ Элиаде 1986 .

- ^ Ходдинотт, с. 27.

- ^ Кассон, с. 3.

- ^ Гора 1998 , с. 58.

- ^ Думитреску и др. 1982 , стр. 53.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Гора 1998 , с. 59.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Бэтти 2007 , с. 202-203.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Ольбрихт 2000 .

- ^ Холлоси, Иштван (1913). Выходцы из Венгрии и происхождение валахов [ Уроженцы Венгрии и происхождение валахов ] (PDF) . Мор Рат. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 15 декабря 2013 г.

- ^ Парван 1926 , стр. 279.

- ^ Страбон, Джонс и Стерретт 1967 , с. 28.

- ^ Абрамея 1994 , с. 17.

- ^ Бог 2008 , Том 3.

- ^ Папазоглу 1978 , с. 67.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Парван 1926 , с. 221: Агриппа комментирует: «Дакия и Гетико ограничены на востоке пустынями Сарматии, на западе рекой Вислой, на севере океаном, на юге рекой Хистрий. Их длина составляет 280 миль, в ширину, которая, как полагают, составляет 386 миль».

- ^ Шютте 1917 , с. 109.

- ^ Шютте 1917 , стр. 101 и 109.

- ^ Трептов 1996 , с. 10.

- ^ Эллис 1861 , с. 70.

- ^ Брикше 2008 , с. 72.

- ^ Дуриданов 1985 , с. 130.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Поломе 1982 , с. 876.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Перегрин и Эмбер 2001 , с. 215.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Цена 2000 г. , с. 120.

- ^ Ренфрю 1990 , с. 71.

- ^ Хейнсворт 1982 , с. 848.

- ^ Поломе 1983 , с. 540.

- ^ National Geographic, Хаббл, 25 апреля 2015 г., Рассказ Эндрю Карри, стр.128.

- ^ Crossland & Boardman 1982 , с. 838.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Олтеан 2007 , стр. 46.

- ^ Кох 2007 , с. 1471.

- ^ Шютте 1917 , с. 88.

- ^ Шютте 1917 , с. 89.

- ^ Беннетт 1997 , с. 47.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Парван 1926 , стр. 250.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Уилкокс 2000 , с. 18.

- ^ Уилкокс 2000 , с. 24.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Парван 1926 , стр. 222–223.

- ^ Птолемей III.5 и 8

- ^ Баррингтон Табличка 22

- ^ Руску 2004 , с. 78.

- ^ Уилкокс (2000)27

- ^ Маккензи 1986 , с. 51.

- ^ МакКендрик 2000 , с. 90.

- ^ Миллар 1981 .

- ^ Бансон 2002 , с. 167.

- ^ Поп 2000 , с. 22.

- ^ Денн Паркер 1958 , стр. 12 и 19.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Уилкс 2005 , с. 224.

- ^ Птолемей III.8

- ^ Тацит G.43

- ^ Олтеан 2007 , стр. 47.

- ^ Парван 1926 , стр. 461–462.

- ^

- Хизер 2010 , с. 131

- Уолдман и Мейсон 2006 , с. 184

- Погирк 1989 , с. 302

- Парван 1928 , стр. 184 и 188.

- Нандрис 1976 , с. 729

- Оледский 2000 , с. 525

- Астарита 1983 , с. 62

- ^ Jump up to: а б Брюшевский 1997 , p. 100.

- ^ Уолдман и Мейсон 2006 , с. 184.

- ^ Нандрис 1976 , с. 729.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Брюшевский 1997 , p. 98.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Шютте 1917 , с. 100.

- ^ Парван и Флореску 1982 , стр. 135.

- ^ Смит 1873 , с. 916.

- ^ Шютте 1917 , с. 18.

- ^ Хизер 2010 , с. 131.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Томашек 1883 , с. 407.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Шютте 1917 , с. 143.

- ^ Руссо 1969 , стр. 99, 116.

- ^ VI, 1 801 = 854 шек.

- ^ VI, 16, 903.

- ^ Руссо 1967 , с. 161.

- ^ Шютте 1917 , с. 101.

- ^ Парван и Флореску 1982 , стр. 142 и 152.

- ^

- Гоффарт 2006 , стр. 205.

- Бансон 1995 , с. 74

- МакКендрик 2000 , с. 117

- Парван и Флореску 1982 , стр. 136.

- Бернс 1991 , стр. 26 и 27.

- Одал 2004 , с. 19

- Уолдман и Мейсон 2006 , с. 19

- Миллар 1981 г.

- ^ Уолдман и Мейсон 2006 , с. 129.

- ^ Хизер 2010 , с. 114.

- ^ Парван 1926 , стр. 239.

- ^ Руссо 1969 , стр. 114–115.

- ^ Томашек 1883 , с. 403.

- ^ Гоффарт 2006 , стр. 205.

- ^ Помните, 2011 г. , стр. 124.

- ^ Никсон и Сэйлор Роджерс 1995 , с. 116.

- ^ Кларк 2003 , с. 37.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г Олтеан 2007 , стр. 45.

- ^ Аристотель (2001). «Волосы (Т.3.)» . De Generatione Animalium (перевод Артура Платта) . Центр электронных текстов, Библиотека Университета Вирджинии. Архивировано из оригинала 15 декабря 2012 г. Проверено 11 января 2014 г.

- ^ Климент Александрийский . «Язычники создали себе подобных себе богов, откуда и происходят все суеверия (VII.4.)» . Строматы, или Сборники . Ранние христианские сочинения. Архивировано из оригинала 13 июня 2002 г. Проверено 11 января 2014 г.

- ^ Уолдман и Мейсон 2006 , с. 208.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Бери и др. 1954 , с. 543.

- ^ Олтеан 2007 , стр. 114.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Думитреску и др. 1982 , с. 166.

- ^ Парван 1928 , стр. 35.

- ^ Парван, Вульпе и Вульпе 2002 , стр. 49.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Кох 2005 , с. 549.

- ^ Парван 1926 , стр. 661.

- ^ Георгиев, Владимир (1966). «Происхождение балканских народов» . Славянское и восточноевропейское обозрение . 44 (103): 286–288. ISSN 0037-6795 . JSTOR 4205776 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Томашек 1883 , стр. 400–401.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Тейлор 2001 , с. 215.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с МакКендрик 2000 , с. 50.

- ^ Кох 2005 , с. 550.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Скварна, Cicaj & Letz 2000 , с. 14.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Парван 1928 , стр. 48.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Геродот и 440 г. до н.э. , 4.48–4.49.

- ^ Геродот, Роулинсон Дж., Роулинсон Х., Гарднер (1859) 93

- ^ Томсон 1948 , с. 399.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Брюшевский 1997 , p. 97.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Уотсон 2004 , с. 8.

- ^ Хизер 2006 , с. 85.

- ^ Бернс 1991 , стр. 26–27.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Бернс 1991 , стр. 110–111.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Южный 2001 , с. 325.

- ^ Хизер 2010 , с. 128.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Хизер 2010 , с. 116.

- ^ Хизер 2010 , с. 165.

- ^ Барнс 1984 , с. 250.

- ^ Элтон и Ленски 2005 , с. 338.

- ^ Льюис и др. 2008 , с. 773.

- ^ Берресфорд Эллис 1996 , с. 61.

- ^ Словарь Смита: Curio

- ^ Словарь Смита: Лукулл

- ^ Страбон и 20 г. н.э. , VII 3,13.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Грумеза 2009 , с. 54.

- ^ МакКендрик 2000 , с. 48.

- ^ Гудман и Шервуд 2002 , с. 227.

- ^ Кришан 1978 , стр. 118.

- ^ Бог LI.26.5

- ^ Бог LI.23.2

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Олтеан 2007 , стр. 53–54.

- ^ Беннетт 1997 , с. 97.

- ^ Снукс 2002 , с. 153.

- ^ Буй 2001 , с. 47.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Уолдман и Мейсон 2006 , с. 205.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Клеппер, Николае (2002). Румыния: Иллюстрированная история . Гиппокреновые книги. ISBN 9780781809351 .

- ^ Маккендрик 2000 .

- ^ Поп 2000 .

- ^ Олтеан 2007 .

- ^ Копечи, Бела; Маккай, Ласло; Мочи, Андраш; Сас, Золтан; Барта, Габор. История Трансильвании - От истоков до 1606 года .

- ^ Джорджеску 1991 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Боуман, Кэмерон и Гарнси, 2005 , с. 224.

- ^ Сиани-Дэвис, Сиани-Дэвис и Делетант 1998 , с. 33.

- ^ Коуэн 2003 , с. 5.

- ^ Хейзел 2002 , с. 360.

- ^ МакКендрик 2000 , с. 161.

- ^ Хизер 2006 , с. 159.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Тейлор 2001 , стр. 214–215.

- ^ Эллис 1998 , с. 229.

- ^ Эллис 1998 , с. 232.

- ^ Эпплбаум 1976 , с. 91.

- ^ Тейлор 2001 , с. 86.

- ^ Миллар 1981 , с. 279.

- ^ Shchukin, Kazanski & Sharov 2006 , p. 20.

- ^ Костшевский 1949 , стр. 230.

- ^ Яжджевский 1948 , стр. 76.

- ↑ Shchukin 1989 , p. 306.

- ^ Парван и Флореску 1982 , стр. 547.