Римская империя

Римская империя

| |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 г. до н. э. – 395 г. н. э. (единый) [1] 395–476/480 гг. н.э. ( Западный ) 395–1453 гг. н.э. ( Восточный ) | |||||||||||

Roman Empire in AD 117 at its greatest extent, at the time of Trajan's death | |||||||||||

Roman territorial evolution from the rise of the city-state of Rome to the fall of the Western Roman Empire | |||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Roman | ||||||||||

| Government | Semi-elective absolute monarchy (de facto) | ||||||||||

• Emperor | (List) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Classical era to Late Middle Ages (Timeline) | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 25 BC[15] | 2,750,000 km2 (1,060,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| AD 117[15][16] | 5,000,000 km2 (1,900,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| AD 390[15] | 3,400,000 km2 (1,300,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 25 BC[17] | 56,800,000 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Sestertius,[e] aureus, solidus, nomisma | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Римская империя [а] было постреспубликанским государством Древнего Рима . Обычно понимается, что это означает период и территорию, которой правили римляне после того, как Октавиан принял единоличное правление в рамках принципата в 27 г. до н.э. Оно включало территории в Европе , Северной Африке и Передней Азии и управлялось императорами . Падение Западной Римской империи в 476 году нашей эры условно знаменует собой конец классической античности и начало Средневековья .

Рим распространил свое господство на большую часть Средиземноморья и за его пределы. Однако оно было серьезно дестабилизировано гражданскими войнами и политическими конфликтами , кульминацией которых стала победа Октавиана над Марком Антонием и Клеопатрой в битве при Акциуме в 31 г. до н.э. и последующее завоевание Птолемеевского царства в Египте. В 27 г. до н.э. сенат предоставил Октавиану верховную власть ( империум ) и новый титул Августа , ознаменовав его вступление на престол в качестве первого римского императора монархии римский с Римом в качестве единственной столицы. Обширные римские территории были организованы в сенаторские провинции, управляемые проконсулами, назначавшимися ежегодно по жребию, и имперские провинции, принадлежавшие императору, но управляемые легатами . [19]

The first two centuries of the Empire saw a period of unprecedented stability and prosperity known as the Pax Romana (lit. 'Roman Peace'). Rome reached its greatest territorial extent under Trajan (r. 98–117 AD); a period of increasing trouble and decline began under Commodus (180–192). In the 3rd century, the Empire underwent a crisis that threatened its existence, as the Gallic and Palmyrene Empires broke away from the Roman state, and a series of short-lived emperors led the Empire. It was reunified under Aurelian (r. 270–275). Diocletian set up two different imperial courts in the Greek East and Latin West in 286; Christians rose to power in the 4th century after the Edict of Milan. The imperial seat moved from Rome to Byzantium in 330, renamed Constantinople after Constantine the Great. The Migration Period, involving large invasions by Germanic peoples and by the Huns of Attila, led to the decline of the Western Roman Empire. With the fall of Ravenna to the Germanic Herulians and the deposition of Romulus Augustus in 476 AD by Odoacer, the Western Roman Empire finally collapsed. The Eastern Roman Empire survived for another millennium with Constantinople as its sole capital, until the city's fall in 1453.[f]

Due to the Empire's extent and endurance, its institutions and culture had a lasting influence on the development of language, religion, art, architecture, literature, philosophy, law, and forms of government across its territories. Latin evolved into the Romance languages while Medieval Greek became the language of the East. The Empire's adoption of Christianity resulted in the formation of medieval Christendom. Roman and Greek art had a profound impact on the Italian Renaissance. Rome's architectural tradition served as the basis for Romanesque, Renaissance and Neoclassical architecture, influencing Islamic architecture. The rediscovery of classical science and technology (which formed the basis for Islamic science) in medieval Europe contributed to the Scientific Renaissance and Scientific Revolution. Many modern legal systems, such as the Napoleonic Code, descend from Roman law. Rome's republican institutions have influenced the Italian city-state republics of the medieval period, the early United States, and modern democratic republics.

History

Transition from Republic to Empire

Rome had begun expanding shortly after the founding of the Roman Republic in the 6th century BC, though not outside the Italian peninsula until the 3rd century BC. Thus, it was an "empire" (a great power) long before it had an emperor.[21] The Republic was not a nation-state in the modern sense, but a network of self-ruled towns (with varying degrees of independence from the Senate) and provinces administered by military commanders. It was governed by annually elected magistrates (Roman consuls above all) in conjunction with the Senate.[22] The 1st century BC was a time of political and military upheaval, which ultimately led to rule by emperors.[23][24][25] The consuls' military power rested in the Roman legal concept of imperium, meaning "command" (though typically in a military sense).[26] Occasionally, successful consuls were given the honorary title imperator (commander); this is the origin of the word emperor, since this title was always bestowed to the early emperors.[27]

Rome suffered a long series of internal conflicts, conspiracies, and civil wars from the late second century BC (see Crisis of the Roman Republic) while greatly extending its power beyond Italy. In 44 BC Julius Caesar was briefly dictator before being assassinated. The faction of his assassins was driven from Rome and defeated at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC by Mark Antony and Caesar's adopted son Octavian. Antony and Octavian's division of the Roman world did not last and Octavian's forces defeated those of Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. In 27 BC the Senate made Octavian princeps ("first citizen") with proconsular imperium, thus beginning the Principate (the first epoch of Roman imperial history, usually dated from 27 BC to 284 AD), and gave him the title Augustus ("the venerated"). Although the republic stood in name, Augustus had all meaningful authority.[28] Since his rule began an unprecedented period of peace and prosperity, he was so loved that he came to hold the power of a monarch de facto if not de jure. During the years of his rule, a new constitutional order emerged (in part organically and in part by design), so that, upon his death, this new constitutional order operated as before when Tiberius was accepted as the new emperor.[citation needed]

Pax Romana

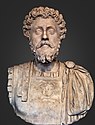

The 200 years that began with Augustus's rule is traditionally regarded as the Pax Romana ("Roman Peace"). The cohesion of the empire was furthered by a degree of social stability and economic prosperity that Rome had never before experienced. Uprisings in the provinces were infrequent and put down "mercilessly and swiftly".[29] The success of Augustus in establishing principles of dynastic succession was limited by his outliving a number of talented potential heirs. The Julio-Claudian dynasty lasted for four more emperors—Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero—before it yielded in 69 AD to the strife-torn Year of the Four Emperors, from which Vespasian emerged as victor. Vespasian became the founder of the brief Flavian dynasty, followed by the Nerva–Antonine dynasty which produced the "Five Good Emperors": Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius.[citation needed]

Transition from classical to late antiquity

In the view of contemporary Greek historian Cassius Dio, the accession of Commodus in 180 marked the descent "from a kingdom of gold to one of rust and iron",[30] a comment which has led some historians, notably Edward Gibbon, to take Commodus' reign as the beginning of the Empire's decline.[31][32]

In 212, during the reign of Caracalla, Roman citizenship was granted to all freeborn inhabitants of the empire. The Severan dynasty was tumultuous; an emperor's reign was ended routinely by his murder or execution and, following its collapse, the Empire was engulfed by the Crisis of the Third Century, a period of invasions, civil strife, economic disorder, and plague.[33] In defining historical epochs, this crisis sometimes marks the transition from Classical to Late Antiquity. Aurelian (r. 270–275) stabilised the empire militarily and Diocletian reorganised and restored much of it in 285.[34] Diocletian's reign brought the empire's most concerted effort against the perceived threat of Christianity, the "Great Persecution".[citation needed]

Diocletian divided the empire into four regions, each ruled by a separate tetrarch.[35] Confident that he fixed the disorder plaguing Rome, he abdicated along with his co-emperor, but the Tetrarchy collapsed shortly after. Order was eventually restored by Constantine the Great, who became the first emperor to convert to Christianity, and who established Constantinople as the new capital of the Eastern Empire. During the decades of the Constantinian and Valentinian dynasties, the empire was divided along an east–west axis, with dual power centres in Constantinople and Rome. Julian, who under the influence of his adviser Mardonius attempted to restore Classical Roman and Hellenistic religion, only briefly interrupted the succession of Christian emperors. Theodosius I, the last emperor to rule over both East and West, died in 395 after making Christianity the state religion.[36]

Fall in the West and survival in the East

The Western Roman Empire began to disintegrate in the early 5th century. The Romans were successful in fighting off all invaders, most famously Attila,[37] but the empire had assimilated so many Germanic peoples of dubious loyalty to Rome that the empire started to dismember itself.[38] Most chronologies place the end of the Western Roman Empire in 476, when Romulus Augustulus was forced to abdicate to the Germanic warlord Odoacer.[39][40][41]

Odoacer ended the Western Empire by declaring Zeno sole emperor and placing himself as Zeno's nominal subordinate. In reality, Italy was ruled by Odoacer alone.[39][40][42] The Eastern Roman Empire, called the Byzantine Empire by later historians, continued until the reign of Constantine XI Palaiologos. The last Roman emperor died in battle in 1453 against Mehmed II and his Ottoman forces during the siege of Constantinople. Mehmed II adopted the title of caesar in an attempt to claim a connection to the Empire.[43]

Geography and demography

The Roman Empire was one of the largest in history, with contiguous territories throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East.[44] The Latin phrase imperium sine fine ("empire without end"[45]) expressed the ideology that neither time nor space limited the Empire. In Virgil's Aeneid, limitless empire is said to be granted to the Romans by Jupiter.[46] This claim of universal dominion was renewed when the Empire came under Christian rule in the 4th century.[g] In addition to annexing large regions, the Romans directly altered their geography, for example cutting down entire forests.[48]

Roman expansion was mostly accomplished under the Republic, though parts of northern Europe were conquered in the 1st century, when Roman control in Europe, Africa, and Asia was strengthened. Under Augustus, a "global map of the known world" was displayed for the first time in public at Rome, coinciding with the creation of the most comprehensive political geography that survives from antiquity, the Geography of Strabo.[49] When Augustus died, the account of his achievements (Res Gestae) prominently featured the geographical cataloguing of the Empire.[50] Geography alongside meticulous written records were central concerns of Roman Imperial administration.[51]

The Empire reached its largest expanse under Trajan (r. 98–117),[52] encompassing 5 million square kilometres.[15][16] The traditional population estimate of 55–60 million inhabitants[53] accounted for between one-sixth and one-fourth of the world's total population[54] and made it the most populous unified political entity in the West until the mid-19th century.[55] Recent demographic studies have argued for a population peak from 70 million to more than 100 million.[56] Each of the three largest cities in the Empire – Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch – was almost twice the size of any European city at the beginning of the 17th century.[57]

As the historian Christopher Kelly described it:

Then the empire stretched from Hadrian's Wall in drizzle-soaked northern England to the sun-baked banks of the Euphrates in Syria; from the great Rhine–Danube river system, which snaked across the fertile, flat lands of Europe from the Low Countries to the Black Sea, to the rich plains of the North African coast and the luxuriant gash of the Nile Valley in Egypt. The empire completely circled the Mediterranean ... referred to by its conquerors as mare nostrum—'our sea'.[53]

Trajan's successor Hadrian adopted a policy of maintaining rather than expanding the empire. Borders (fines) were marked, and the frontiers (limites) patrolled.[52] The most heavily fortified borders were the most unstable.[24] Hadrian's Wall, which separated the Roman world from what was perceived as an ever-present barbarian threat, is the primary surviving monument of this effort.[58]

Languages

Latin and Greek were the main languages of the Empire,[h] but the Empire was deliberately multilingual.[63] Andrew Wallace-Hadrill says "The main desire of the Roman government was to make itself understood".[64] At the start of the Empire, knowledge of Greek was useful to pass as educated nobility and knowledge of Latin was useful for a career in the military, government, or law.[65] Bilingual inscriptions indicate the everyday interpenetration of the two languages.[66]

Latin and Greek's mutual linguistic and cultural influence is a complex topic.[67] Latin words incorporated into Greek were very common by the early imperial era, especially for military, administration, and trade and commerce matters.[68] Greek grammar, literature, poetry and philosophy shaped Latin language and culture.[69][70]

There was never a legal requirement for Latin in the Empire, but it represented a certain status.[72] High standards of Latin, Latinitas, started with the advent of Latin literature.[73] Due to the flexible language policy of the Empire, a natural competition of language emerged that spurred Latinitas, to defend Latin against the stronger cultural influence of Greek.[74] Over time Latin usage was used to project power and a higher social class.[75][76] Most of the emperors were bilingual but had a preference for Latin in the public sphere for political reasons, a "rule" that first started during the Punic Wars.[77] Different emperors up until Justinian would attempt to require the use of Latin in various sections of the administration but there is no evidence that a linguistic imperialism existed during the early Empire.[78]

After all freeborn inhabitants were universally enfranchised in 212, many Roman citizens would have lacked a knowledge of Latin.[79] The wide use of Koine Greek was what enabled the spread of Christianity and reflects its role as the lingua franca of the Mediterranean during the time of the Empire.[80] Following Diocletian's reforms in the 3rd century CE, there was a decline in the knowledge of Greek in the west.[81] Spoken Latin later fragmented into the incipient romance languages in the 7th century CE following the collapse of the Empire's west.[82]

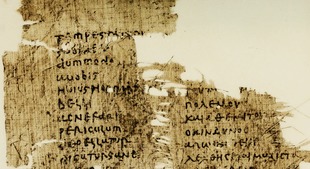

The dominance of Latin and Greek among the literate elite obscure the continuity of other spoken languages within the Empire.[83] Latin, referred to in its spoken form as Vulgar Latin, gradually replaced Celtic and Italic languages.[84][85] References to interpreters indicate the continuing use of local languages, particularly in Egypt with Coptic, and in military settings along the Rhine and Danube. Roman jurists also show a concern for local languages such as Punic, Gaulish, and Aramaic in assuring the correct understanding of laws and oaths.[86] In Africa, Libyco-Berber and Punic were used in inscriptions into the 2nd century.[83] In Syria, Palmyrene soldiers used their dialect of Aramaic for inscriptions, an exception to the rule that Latin was the language of the military.[87] The last reference to Gaulish was between 560 and 575.[88][89] The emergent Gallo-Romance languages would then be shaped by Gaulish.[90] Proto-Basque or Aquitanian evolved with Latin loan words to modern Basque.[91] The Thracian language, as were several now-extinct languages in Anatolia, are attested in Imperial-era inscriptions.[80][83]

Society

The Empire was remarkably multicultural, with "astonishing cohesive capacity" to create shared identity while encompassing diverse peoples.[93] Public monuments and communal spaces open to all—such as forums, amphitheatres, racetracks and baths—helped foster a sense of "Romanness".[94]

Roman society had multiple, overlapping social hierarchies.[95] The civil war preceding Augustus caused upheaval,[96] but did not effect an immediate redistribution of wealth and social power. From the perspective of the lower classes, a peak was merely added to the social pyramid.[97] Personal relationships—patronage, friendship (amicitia), family, marriage—continued to influence politics.[98] By the time of Nero, however, it was not unusual to find a former slave who was richer than a freeborn citizen, or an equestrian who exercised greater power than a senator.[99]

The blurring of the Republic's more rigid hierarchies led to increased social mobility,[100] both upward and downward, to a greater extent than all other well-documented ancient societies.[101] Women, freedmen, and slaves had opportunities to profit and exercise influence in ways previously less available to them.[102] Social life, particularly for those whose personal resources were limited, was further fostered by a proliferation of voluntary associations and confraternities (collegia and sodalitates): professional and trade guilds, veterans' groups, religious sodalities, drinking and dining clubs,[103] performing troupes,[104] and burial societies.[105]

Legal status

According to the jurist Gaius, the essential distinction in the Roman "law of persons" was that all humans were either free (liberi) or slaves (servi).[106] The legal status of free persons was further defined by their citizenship. Most citizens held limited rights (such as the ius Latinum, "Latin right"), but were entitled to legal protections and privileges not enjoyed by non-citizens. Free people not considered citizens, but living within the Roman world, were peregrini, non-Romans.[107] In 212, the Constitutio Antoniniana extended citizenship to all freeborn inhabitants of the empire. This legal egalitarianism required a far-reaching revision of existing laws that distinguished between citizens and non-citizens.[108]

Women in Roman law

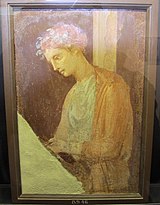

Right: Bronze statuette (1st century AD) of a young woman reading, based on a Hellenistic original

Freeborn Roman women were considered citizens, but did not vote, hold political office, or serve in the military. A mother's citizen status determined that of her children, as indicated by the phrase ex duobus civibus Romanis natos ("children born of two Roman citizens").[i] A Roman woman kept her own family name (nomen) for life. Children most often took the father's name, with some exceptions.[111] Women could own property, enter contracts, and engage in business.[112] Inscriptions throughout the Empire honour women as benefactors in funding public works, an indication they could hold considerable fortunes.[113]

The archaic manus marriage in which the woman was subject to her husband's authority was largely abandoned by the Imperial era, and a married woman retained ownership of any property she brought into the marriage. Technically she remained under her father's legal authority, even though she moved into her husband's home, but when her father died she became legally emancipated.[114] This arrangement was a factor in the degree of independence Roman women enjoyed compared to many other cultures up to the modern period:[115] although she had to answer to her father in legal matters, she was free of his direct scrutiny in daily life,[116] and her husband had no legal power over her.[117] Although it was a point of pride to be a "one-man woman" (univira) who had married only once, there was little stigma attached to divorce, nor to speedy remarriage after being widowed or divorced.[118] Girls had equal inheritance rights with boys if their father died without leaving a will.[119] A mother's right to own and dispose of property, including setting the terms of her will, gave her enormous influence over her sons into adulthood.[120]

As part of the Augustan programme to restore traditional morality and social order, moral legislation attempted to regulate conduct as a means of promoting "family values". Adultery was criminalized,[121] and defined broadly as an illicit sex act (stuprum) between a male citizen and a married woman, or between a married woman and any man other than her husband. That is, a double standard was in place: a married woman could have sex only with her husband, but a married man did not commit adultery if he had sex with a prostitute or person of marginalized status.[122] Childbearing was encouraged: a woman who had given birth to three children was granted symbolic honours and greater legal freedom (the ius trium liberorum).[123]

Slaves and the law

At the time of Augustus, as many as 35% of the people in Roman Italy were slaves,[124] making Rome one of five historical "slave societies" in which slaves constituted at least a fifth of the population and played a major role in the economy.[j][124] Slavery was a complex institution that supported traditional Roman social structures as well as contributing economic utility.[125] In urban settings, slaves might be professionals such as teachers, physicians, chefs, and accountants; the majority of slaves provided trained or unskilled labour. Agriculture and industry, such as milling and mining, relied on the exploitation of slaves. Outside Italy, slaves were on average an estimated 10 to 20% of the population, sparse in Roman Egypt but more concentrated in some Greek areas. Expanding Roman ownership of arable land and industries affected preexisting practices of slavery in the provinces.[126] Although slavery has often been regarded as waning in the 3rd and 4th centuries, it remained an integral part of Roman society until gradually ceasing in the 6th and 7th centuries with the disintegration of the complex Imperial economy.[127]

Laws pertaining to slavery were "extremely intricate".[128] Slaves were considered property and had no legal personhood. They could be subjected to forms of corporal punishment not normally exercised on citizens, sexual exploitation, torture, and summary execution. A slave could not as a matter of law be raped; a slave's rapist had to be prosecuted by the owner for property damage under the Aquilian Law.[129] Slaves had no right to the form of legal marriage called conubium, but their unions were sometimes recognized.[130] Technically, a slave could not own property,[131] but a slave who conducted business might be given access to an individual fund (peculium) that he could use, depending on the degree of trust and co-operation between owner and slave.[132] Within a household or workplace, a hierarchy of slaves might exist, with one slave acting as the master of others.[133] Talented slaves might accumulate a large enough peculium to justify their freedom, or be manumitted for services rendered. Manumission had become frequent enough that in 2 BC a law (Lex Fufia Caninia) limited the number of slaves an owner was allowed to free in his will.[134]

Following the Servile Wars of the Republic, legislation under Augustus and his successors shows a driving concern for controlling the threat of rebellions through limiting the size of work groups, and for hunting down fugitive slaves.[135] Over time slaves gained increased legal protection, including the right to file complaints against their masters. A bill of sale might contain a clause stipulating that the slave could not be employed for prostitution, as prostitutes in ancient Rome were often slaves.[136] The burgeoning trade in eunuchs in the late 1st century prompted legislation that prohibited the castration of a slave against his will "for lust or gain".[137]

Roman slavery was not based on race.[138] Generally, slaves in Italy were indigenous Italians,[139] with a minority of foreigners (including both slaves and freedmen) estimated at 5% of the total in the capital at its peak, where their number was largest. Foreign slaves had higher mortality and lower birth rates than natives, and were sometimes even subjected to mass expulsions.[140] The average recorded age at death for the slaves of the city of Rome was seventeen and a half years (17.2 for males; 17.9 for females).[141]

During the period of republican expansionism when slavery had become pervasive, war captives were a main source of slaves. The range of ethnicities among slaves to some extent reflected that of the armies Rome defeated in war, and the conquest of Greece brought a number of highly skilled and educated slaves. Slaves were also traded in markets and sometimes sold by pirates. Infant abandonment and self-enslavement among the poor were other sources.[142] Vernae, by contrast, were "homegrown" slaves born to female slaves within the household, estate or farm. Although they had no special legal status, an owner who mistreated or failed to care for his vernae faced social disapproval, as they were considered part of the family household and in some cases might actually be the children of free males in the family.[143]

Freedmen

Rome differed from Greek city-states in allowing freed slaves to become citizens; any future children of a freedman were born free, with full rights of citizenship. After manumission, a slave who had belonged to a Roman citizen enjoyed active political freedom (libertas), including the right to vote.[144] His former master became his patron (patronus): the two continued to have customary and legal obligations to each other.[145][146] A freedman was not entitled to hold public office or the highest state priesthoods, but could play a priestly role. He could not marry a woman from a senatorial family, nor achieve legitimate senatorial rank himself, but during the early Empire, freedmen held key positions in the government bureaucracy, so much so that Hadrian limited their participation by law.[146] The rise of successful freedmen—through political influence or wealth—is a characteristic of early Imperial society. The prosperity of a high-achieving group of freedmen is attested by inscriptions throughout the Empire, and by their ownership of some of the most lavish houses at Pompeii.[citation needed]

Census rank

The Latin word ordo (plural ordines) is translated variously and inexactly into English as "class, order, rank". One purpose of the Roman census was to determine the ordo to which an individual belonged. The two highest ordines in Rome were the senatorial and equestrian.[citation needed] Outside Rome, the decurions, also known as curiales, were the top governing ordo of an individual city.[citation needed]

"Senator" was not itself an elected office in ancient Rome; an individual gained admission to the Senate after he had been elected to and served at least one term as an executive magistrate. A senator also had to meet a minimum property requirement of 1 million sestertii.[147] Not all men who qualified for the ordo senatorius chose to take a Senate seat, which required legal domicile at Rome. Emperors often filled vacancies in the 600-member body by appointment.[148] A senator's son belonged to the ordo senatorius, but he had to qualify on his own merits for admission to the Senate. A senator could be removed for violating moral standards.[149]

In the time of Nero, senators were still primarily from Italy, with some from the Iberian peninsula and southern France; men from the Greek-speaking provinces of the East began to be added under Vespasian.[150] The first senator from the easternmost province, Cappadocia, was admitted under Marcus Aurelius.[k] By the Severan dynasty (193–235), Italians made up less than half the Senate.[152] During the 3rd century, domicile at Rome became impractical, and inscriptions attest to senators who were active in politics and munificence in their homeland (patria).[149]

Senators were the traditional governing class who rose through the cursus honorum, the political career track, but equestrians often possessed greater wealth and political power. Membership in the equestrian order was based on property; in Rome's early days, equites or knights had been distinguished by their ability to serve as mounted warriors, but cavalry service was a separate function in the Empire.[l] A census valuation of 400,000 sesterces and three generations of free birth qualified a man as an equestrian.[154] The census of 28 BC uncovered large numbers of men who qualified, and in 14 AD, a thousand equestrians were registered at Cádiz and Padua alone.[m][156] Equestrians rose through a military career track (tres militiae) to become highly placed prefects and procurators within the Imperial administration.[157]

The rise of provincial men to the senatorial and equestrian orders is an aspect of social mobility in the early Empire. Roman aristocracy was based on competition, and unlike later European nobility, a Roman family could not maintain its position merely through hereditary succession or having title to lands.[158] Admission to the higher ordines brought distinction and privileges, but also responsibilities. In antiquity, a city depended on its leading citizens to fund public works, events, and services (munera). Maintaining one's rank required massive personal expenditures.[159] Decurions were so vital for the functioning of cities that in the later Empire, as the ranks of the town councils became depleted, those who had risen to the Senate were encouraged to return to their hometowns, in an effort to sustain civic life.[160]

In the later Empire, the dignitas ("worth, esteem") that attended on senatorial or equestrian rank was refined further with titles such as vir illustris ("illustrious man").[161] The appellation clarissimus (Greek lamprotatos) was used to designate the dignitas of certain senators and their immediate family, including women.[162] "Grades" of equestrian status proliferated.[163]

Unequal justice

As the republican principle of citizens' equality under the law faded, the symbolic and social privileges of the upper classes led to an informal division of Roman society into those who had acquired greater honours (honestiores) and humbler folk (humiliores). In general, honestiores were the members of the three higher "orders", along with certain military officers.[164] The granting of universal citizenship in 212 seems to have increased the competitive urge among the upper classes to have their superiority affirmed, particularly within the justice system.[165] Sentencing depended on the judgment of the presiding official as to the relative "worth" (dignitas) of the defendant: an honestior could pay a fine for a crime for which an humilior might receive a scourging.[166]

Execution, which was an infrequent legal penalty for free men under the Republic,[167] could be quick and relatively painless for honestiores, while humiliores might suffer the kinds of torturous death previously reserved for slaves, such as crucifixion and condemnation to the beasts.[168] In the early Empire, those who converted to Christianity could lose their standing as honestiores, especially if they declined to fulfil religious responsibilities, and thus became subject to punishments that created the conditions of martyrdom.[169]

Government and military

The three major elements of the Imperial state were the central government, the military, and the provincial government.[170] The military established control of a territory through war, but after a city or people was brought under treaty, the mission turned to policing: protecting Roman citizens, agricultural fields, and religious sites.[171] The Romans lacked sufficient manpower or resources to rule through force alone. Cooperation with local elites was necessary to maintain order, collect information, and extract revenue. The Romans often exploited internal political divisions.[172]

Communities with demonstrated loyalty to Rome retained their own laws, could collect their own taxes locally, and in exceptional cases were exempt from Roman taxation. Legal privileges and relative independence incentivized compliance.[173] Roman government was thus limited, but efficient in its use of available resources.[174]

Central government

The Imperial cult of ancient Rome identified emperors and some members of their families with divinely sanctioned authority (auctoritas). The rite of apotheosis (also called consecratio) signified the deceased emperor's deification.[175] The dominance of the emperor was based on the consolidation of powers from several republican offices.[176] The emperor made himself the central religious authority as pontifex maximus, and centralized the right to declare war, ratify treaties, and negotiate with foreign leaders.[177] While these functions were clearly defined during the Principate, the emperor's powers over time became less constitutional and more monarchical, culminating in the Dominate.[178]

The emperor was the ultimate authority in policy- and decision-making, but in the early Principate, he was expected to be accessible and deal personally with official business and petitions. A bureaucracy formed around him only gradually.[179] The Julio-Claudian emperors relied on an informal body of advisors that included not only senators and equestrians, but trusted slaves and freedmen.[180] After Nero, the influence of the latter was regarded with suspicion, and the emperor's council (consilium) became subject to official appointment for greater transparency.[181] Though the Senate took a lead in policy discussions until the end of the Antonine dynasty, equestrians played an increasingly important role in the consilium.[182] The women of the emperor's family often intervened directly in his decisions.[183]

Access to the emperor might be gained at the daily reception (salutatio), a development of the traditional homage a client paid to his patron; public banquets hosted at the palace; and religious ceremonies. The common people who lacked this access could manifest their approval or displeasure as a group at games.[184] By the 4th century, the Christian emperors became remote figureheads who issued general rulings, no longer responding to individual petitions.[185] Although the Senate could do little short of assassination and open rebellion to contravene the will of the emperor, it retained its symbolic political centrality.[186] The Senate legitimated the emperor's rule, and the emperor employed senators as legates (legati): generals, diplomats, and administrators.[187]

The practical source of an emperor's power and authority was the military. The legionaries were paid by the Imperial treasury, and swore an annual oath of loyalty to the emperor.[188] Most emperors chose a successor, usually a close family member or adopted heir. The new emperor had to seek a swift acknowledgement of his status and authority to stabilize the political landscape. No emperor could hope to survive without the allegiance of the Praetorian Guard and the legions. To secure their loyalty, several emperors paid the donativum, a monetary reward. In theory, the Senate was entitled to choose the new emperor, but did so mindful of acclamation by the army or Praetorians.[189]

Military

After the Punic Wars, the Roman army comprised professional soldiers who volunteered for 20 years of active duty and five as reserves. The transition to a professional military began during the late Republic and was one of the many profound shifts away from republicanism, under which an army of conscript citizens defended the homeland against a specific threat. The Romans expanded their war machine by "organizing the communities that they conquered in Italy into a system that generated huge reservoirs of manpower for their army".[190] By Imperial times, military service was a full-time career.[191] The pervasiveness of military garrisons throughout the Empire was a major influence in the process of Romanization.[192]

The primary mission of the military of the early empire was to preserve the Pax Romana.[193] The three major divisions of the military were:

- the garrison at Rome, comprising the Praetorian Guard, the cohortes urbanae and the vigiles, who functioned as police and firefighters;

- the provincial army, comprising the Roman legions and the auxiliaries provided by the provinces (auxilia);

- the navy.

Through his military reforms, which included consolidating or disbanding units of questionable loyalty, Augustus regularized the legion. A legion was organized into ten cohorts, each of which comprised six centuries, with a century further made up of ten squads (contubernia); the exact size of the Imperial legion, which was likely determined by logistics, has been estimated to range from 4,800 to 5,280.[194] After Germanic tribes wiped out three legions in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD, the number of legions was increased from 25 to around 30.[195] The army had about 300,000 soldiers in the 1st century, and under 400,000 in the 2nd, "significantly smaller" than the collective armed forces of the conquered territories. No more than 2% of adult males living in the Empire served in the Imperial army.[196] Augustus also created the Praetorian Guard: nine cohorts, ostensibly to maintain the public peace, which were garrisoned in Italy. Better paid than the legionaries, the Praetorians served only sixteen years.[197]

The auxilia were recruited from among the non-citizens. Organized in smaller units of roughly cohort strength, they were paid less than the legionaries, and after 25 years of service were rewarded with Roman citizenship, also extended to their sons. According to Tacitus[198] there were roughly as many auxiliaries as there were legionaries—thus, around 125,000 men, implying approximately 250 auxiliary regiments.[199] The Roman cavalry of the earliest Empire were primarily from Celtic, Hispanic or Germanic areas. Several aspects of training and equipment derived from the Celts.[200]

The Roman navy not only aided in the supply and transport of the legions but also in the protection of the frontiers along the rivers Rhine and Danube. Another duty was protecting maritime trade against pirates. It patrolled the Mediterranean, parts of the North Atlantic coasts, and the Black Sea. Nevertheless, the army was considered the senior and more prestigious branch.[201]

Provincial government

An annexed territory became a Roman province in three steps: making a register of cities, taking a census, and surveying the land.[202] Further government recordkeeping included births and deaths, real estate transactions, taxes, and juridical proceedings.[203] In the 1st and 2nd centuries, the central government sent out around 160 officials annually to govern outside Italy.[22] Among these officials were the Roman governors: magistrates elected at Rome who in the name of the Roman people governed senatorial provinces; or governors, usually of equestrian rank, who held their imperium on behalf of the emperor in imperial provinces, most notably Roman Egypt.[204] A governor had to make himself accessible to the people he governed, but he could delegate various duties.[205] His staff, however, was minimal: his official attendants (apparitores), including lictors, heralds, messengers, scribes, and bodyguards; legates, both civil and military, usually of equestrian rank; and friends who accompanied him unofficially.[205]

Other officials were appointed as supervisors of government finances.[22] Separating fiscal responsibility from justice and administration was a reform of the Imperial era, to avoid provincial governors and tax farmers exploiting local populations for personal gain.[206] Equestrian procurators, whose authority was originally "extra-judicial and extra-constitutional", managed both state-owned property and the personal property of the emperor (res privata).[205] Because Roman government officials were few, a provincial who needed help with a legal dispute or criminal case might seek out any Roman perceived to have some official capacity.[207]

Law

Roman courts held original jurisdiction over cases involving Roman citizens throughout the empire, but there were too few judicial functionaries to impose Roman law uniformly in the provinces. Most parts of the Eastern Empire already had well-established law codes and juridical procedures.[96] Generally, it was Roman policy to respect the mos regionis ("regional tradition" or "law of the land") and to regard local laws as a source of legal precedent and social stability.[96][208] The compatibility of Roman and local law was thought to reflect an underlying ius gentium, the "law of nations" or international law regarded as common and customary.[209] If provincial law conflicted with Roman law or custom, Roman courts heard appeals, and the emperor held final decision-making authority.[96][208][n]

In the West, law had been administered on a highly localized or tribal basis, and private property rights may have been a novelty of the Roman era, particularly among Celts. Roman law facilitated the acquisition of wealth by a pro-Roman elite.[96] The extension of universal citizenship to all free inhabitants of the Empire in 212 required the uniform application of Roman law, replacing local law codes that had applied to non-citizens. Diocletian's efforts to stabilize the Empire after the Crisis of the Third Century included two major compilations of law in four years, the Codex Gregorianus and the Codex Hermogenianus, to guide provincial administrators in setting consistent legal standards.[210]

The pervasiveness of Roman law throughout Western Europe enormously influenced the Western legal tradition, reflected by continued use of Latin legal terminology in modern law.[citation needed]

Taxation

Taxation under the Empire amounted to about 5% of its gross product.[211] The typical tax rate for individuals ranged from 2 to 5%.[212] The tax code was "bewildering" in its complicated system of direct and indirect taxes, some paid in cash and some in kind. Taxes might be specific to a province, or kinds of properties such as fisheries; they might be temporary.[213] Tax collection was justified by the need to maintain the military,[214] and taxpayers sometimes got a refund if the army captured a surplus of booty.[215] In-kind taxes were accepted from less-monetized areas, particularly those who could supply grain or goods to army camps.[216]

The primary source of direct tax revenue was individuals, who paid a poll tax and a tax on their land, construed as a tax on its produce or productive capacity.[212] Tax obligations were determined by the census: each head of household provided a headcount of his household, as well as an accounting of his property.[217] A major source of indirect-tax revenue was the portoria, customs and tolls on trade, including among provinces.[212] Towards the end of his reign, Augustus instituted a 4% tax on the sale of slaves,[218] which Nero shifted from the purchaser to the dealers, who responded by raising their prices.[219] An owner who manumitted a slave paid a "freedom tax", calculated at 5% of value.[o] An inheritance tax of 5% was assessed when Roman citizens above a certain net worth left property to anyone outside their immediate family. Revenues from the estate tax and from an auction tax went towards the veterans' pension fund (aerarium militare).[212]

Low taxes helped the Roman aristocracy increase their wealth, which equalled or exceeded the revenues of the central government. An emperor sometimes replenished his treasury by confiscating the estates of the "super-rich", but in the later period, the resistance of the wealthy to paying taxes was one of the factors contributing to the collapse of the Empire.[54]

Economy

The Empire is best thought of as a network of regional economies, based on a form of "political capitalism" in which the state regulated commerce to assure its own revenues.[220] Economic growth, though not comparable to modern economies, was greater than that of most other societies prior to industrialization.[221] Territorial conquests permitted a large-scale reorganization of land use that resulted in agricultural surplus and specialization, particularly in north Africa.[222] Some cities were known for particular industries. The scale of urban building indicates a significant construction industry.[222] Papyri preserve complex accounting methods that suggest elements of economic rationalism,[222] and the Empire was highly monetized.[223] Although the means of communication and transport were limited in antiquity, transportation in the 1st and 2nd centuries expanded greatly, and trade routes connected regional economies.[224] The supply contracts for the army drew on local suppliers near the base (castrum), throughout the province, and across provincial borders.[225]Economic historians vary in their calculations of the gross domestic product during the Principate.[226] In the sample years of 14, 100, and 150 AD, estimates of per capita GDP range from 166 to 380 HS. The GDP per capita of Italy is estimated as 40[227] to 66%[228] higher than in the rest of the Empire, due to tax transfers from the provinces and the concentration of elite income.

Economic dynamism resulted in social mobility. Although aristocratic values permeated traditional elite society, wealth requirements for rank indicate a strong tendency towards plutocracy. Prestige could be obtained through investing one's wealth in grand estates or townhouses, luxury items, public entertainments, funerary monuments, and religious dedications. Guilds (collegia) and corporations (corpora) provided support for individuals to succeed through networking.[164] "There can be little doubt that the lower classes of ... provincial towns of the Roman Empire enjoyed a high standard of living not equaled again in Western Europe until the 19th century".[229] Households in the top 1.5% of income distribution captured about 20% of income. The "vast majority" produced more than half of the total income, but lived near subsistence.[230]

Currency and banking

The early Empire was monetized to a near-universal extent, using money as a way to express prices and debts.[232] The sestertius (English "sesterces", symbolized as HS) was the basic unit of reckoning value into the 4th century,[233] though the silver denarius, worth four sesterces, was also used beginning in the Severan dynasty.[234] The smallest coin commonly circulated was the bronze as, one-tenth denarius.[235] Bullion and ingots seem not to have counted as pecunia ("money") and were used only on the frontiers. Romans in the first and second centuries counted coins, rather than weighing them—an indication that the coin was valued on its face. This tendency towards fiat money led to the debasement of Roman coinage in the later Empire.[236] The standardization of money throughout the Empire promoted trade and market integration.[232] The high amount of metal coinage in circulation increased the money supply for trading or saving.[237]Rome had no central bank, and regulation of the banking system was minimal. Banks of classical antiquity typically kept less in reserves than the full total of customers' deposits. A typical bank had fairly limited capital, and often only one principal. Seneca assumes that anyone involved in Roman commerce needs access to credit.[236] A professional deposit banker received and held deposits for a fixed or indefinite term, and lent money to third parties. The senatorial elite were involved heavily in private lending, both as creditors and borrowers.[238] The holder of a debt could use it as a means of payment by transferring it to another party, without cash changing hands. Although it has sometimes been thought that ancient Rome lacked documentary transactions, the system of banks throughout the Empire permitted the exchange of large sums without physically transferring coins, in part because of the risks of moving large amounts of cash. Only one serious credit shortage is known to have occurred in the early Empire, in 33 AD;[239] generally, available capital exceeded the amount needed by borrowers.[236] The central government itself did not borrow money, and without public debt had to fund deficits from cash reserves.[240]

Emperors of the Antonine and Severan dynasties debased the currency, particularly the denarius, under the pressures of meeting military payrolls.[233] Sudden inflation under Commodus damaged the credit market.[236] In the mid-200s, the supply of specie contracted sharply.[233] Conditions during the Crisis of the Third Century—such as reductions in long-distance trade, disruption of mining operations, and the physical transfer of gold coinage outside the empire by invading enemies—greatly diminished the money supply and the banking sector.[233][236] Although Roman coinage had long been fiat money or fiduciary currency, general economic anxieties came to a head under Aurelian, and bankers lost confidence in coins. Despite Diocletian's introduction of the gold solidus and monetary reforms, the credit market of the Empire never recovered its former robustness.[236]

Mining and metallurgy

The main mining regions of the Empire were the Iberian Peninsula (silver, copper, lead, iron and gold);[241] Gaul (gold, silver, iron);[242] Britain (mainly iron, lead, tin),[243] the Danubian provinces (gold, iron);[244] Macedonia and Thrace (gold, silver); and Asia Minor (gold, silver, iron, tin). Intensive large-scale mining—of alluvial deposits, and by means of open-cast mining and underground mining—took place from the reign of Augustus up to the early 3rd century, when the instability of the Empire disrupted production.[citation needed]

Hydraulic mining allowed base and precious metals to be extracted on a proto-industrial scale.[245] The total annual iron output is estimated at 82,500 tonnes.[246] Copper and lead production levels were unmatched until the Industrial Revolution.[247][248][249][250] At its peak around the mid-2nd century, the Roman silver stock is estimated at 10,000 t, five to ten times larger than the combined silver mass of medieval Europe and the Caliphate around 800 AD.[249][251] As an indication of the scale of Roman metal production, lead pollution in the Greenland ice sheet quadrupled over prehistoric levels during the Imperial era and dropped thereafter.[252]

Transportation and communication

The Empire completely encircled the Mediterranean, which they called "our sea" (Mare Nostrum).[253] Roman sailing vessels navigated the Mediterranean as well as major rivers.[57] Transport by water was preferred where possible, as moving commodities by land was more difficult.[254] Vehicles, wheels, and ships indicate the existence of a great number of skilled woodworkers.[255]

Land transport utilized the advanced system of Roman roads, called "viae". These roads were primarily built for military purposes,[256] but also served commercial ends. The in-kind taxes paid by communities included the provision of personnel, animals, or vehicles for the cursus publicus, the state mail and transport service established by Augustus.[216] Relay stations were located along the roads every seven to twelve Roman miles, and tended to grow into villages or trading posts.[257] A mansio (plural mansiones) was a privately run service station franchised by the imperial bureaucracy for the cursus publicus. The distance between mansiones was determined by how far a wagon could travel in a day.[257] Carts were usually pulled by mules, travelling about 4 mph.[258]

Trade and commodities

Roman provinces traded among themselves, but trade extended outside the frontiers to regions as far away as China and India.[259] Chinese trade was mostly conducted overland through middle men along the Silk Road; Indian trade also occurred by sea from Egyptian ports. The main commodity was grain.[260] Also traded were olive oil, foodstuffs, garum (fish sauce), slaves, ore and manufactured metal objects, fibres and textiles, timber, pottery, glassware, marble, papyrus, spices and materia medica, ivory, pearls, and gemstones.[261] Though most provinces could produce wine, regional varietals were desirable and wine was a central trade good.[262]

Labour and occupations

Inscriptions record 268 different occupations in Rome and 85 in Pompeii.[196] Professional associations or trade guilds (collegia) are attested for a wide range of occupations, some quite specialized.[164]

Work performed by slaves falls into five general categories: domestic, with epitaphs recording at least 55 different household jobs; imperial or public service; urban crafts and services; agriculture; and mining. Convicts provided much of the labour in the mines or quarries, where conditions were notoriously brutal.[263] In practice, there was little division of labour between slave and free,[96] and most workers were illiterate and without special skills.[264] The greatest number of common labourers were employed in agriculture: in Italian industrial farming (latifundia), these may have been mostly slaves, but elsewhere slave farm labour was probably less important.[96]

Textile and clothing production was a major source of employment. Both textiles and finished garments were traded and products were often named for peoples or towns, like a fashion "label".[265] Better ready-to-wear was exported by local businessmen (negotiatores or mercatores).[266] Finished garments might be retailed by their sales agents, by vestiarii (clothing dealers), or peddled by itinerant merchants.[266] The fullers (fullones) and dye workers (coloratores) had their own guilds.[267] Centonarii were guild workers who specialized in textile production and the recycling of old clothes into pieced goods.[p]

Architecture and engineering

The chief Roman contributions to architecture were the arch, vault and dome. Some Roman structures still stand today, due in part to sophisticated methods of making cements and concrete.[270] Roman temples developed Etruscan and Greek forms, with some distinctive elements. Roman roads are considered the most advanced built until the early 19th century. The system of roadways facilitated military policing, communications, and trade, and were resistant to floods and other environmental hazards. Some remained usable for over a thousand years.[citation needed]

Roman bridges were among the first large and lasting bridges, built from stone (and in most cases concrete) with the arch as the basic structure. The largest Roman bridge was Trajan's bridge over the lower Danube, constructed by Apollodorus of Damascus, which remained for over a millennium the longest bridge to have been built.[271] The Romans built many dams and reservoirs for water collection, such as the Subiaco Dams, two of which fed the Anio Novus, one of the largest aqueducts of Rome.[272]

The Romans constructed numerous aqueducts. De aquaeductu, a treatise by Frontinus, who served as water commissioner, reflects the administrative importance placed on the water supply. Masonry channels carried water along a precise gradient, using gravity alone. It was then collected in tanks and fed through pipes to public fountains, baths, toilets, or industrial sites.[273] The main aqueducts in Rome were the Aqua Claudia and the Aqua Marcia.[274] The complex system built to supply Constantinople had its most distant supply drawn from over 120 km away along a route of more than 336 km.[275] Roman aqueducts were built to remarkably fine tolerance, and to a technological standard not equalled until modern times.[276] The Romans also used aqueducts in their extensive mining operations across the empire.[277]

Insulated glazing (or "double glazing") was used in the construction of public baths. Elite housing in cooler climates might have hypocausts, a form of central heating. The Romans were the first culture to assemble all essential components of the much later steam engine: the crank and connecting rod system, Hero's aeolipile (generating steam power), the cylinder and piston (in metal force pumps), non-return valves (in water pumps), and gearing (in water mills and clocks).[278]

Daily life

City and country

The city was viewed as fostering civilization by being "properly designed, ordered, and adorned".[279] Augustus undertook a vast building programme in Rome, supported public displays of art that expressed imperial ideology, and reorganized the city into neighbourhoods (vici) administered at the local level with police and firefighting services.[280] A focus of Augustan monumental architecture was the Campus Martius, an open area outside the city centre: the Altar of Augustan Peace (Ara Pacis Augustae) was located there, as was an obelisk imported from Egypt that formed the pointer (gnomon) of a horologium. With its public gardens, the Campus was among the most attractive places in Rome to visit.[280]

City planning and urban lifestyles was influenced by the Greeks early on,[281] and in the Eastern Empire, Roman rule shaped the development of cities that already had a strong Hellenistic character. Cities such as Athens, Aphrodisias, Ephesus and Gerasa tailored city planning and architecture to imperial ideals, while expressing their individual identity and regional preeminence.[282] In areas inhabited by Celtic-speaking peoples, Rome encouraged the development of urban centres with stone temples, forums, monumental fountains, and amphitheatres, often on or near the sites of preexisting walled settlements known as oppida.[283][284][q] Urbanization in Roman Africa expanded on Greek and Punic coastal cities.[257]

The network of cities (coloniae, municipia, civitates or in Greek terms poleis) was a primary cohesive force during the Pax Romana.[185] Romans of the 1st and 2nd centuries were encouraged to "inculcate the habits of peacetime".[286] As the classicist Clifford Ando noted:

Most of the cultural appurtenances popularly associated with imperial culture—public cult and its games and civic banquets, competitions for artists, speakers, and athletes, as well as the funding of the great majority of public buildings and public display of art—were financed by private individuals, whose expenditures in this regard helped to justify their economic power and legal and provincial privileges.[287]

In the city of Rome, most people lived in multistory apartment buildings (insulae) that were often squalid firetraps. Public facilities—such as baths (thermae), toilets with running water (latrinae), basins or elaborate fountains (nymphea) delivering fresh water,[284] and large-scale entertainments such as chariot races and gladiator combat—were aimed primarily at the common people.[288] Similar facilities were constructed in cities throughout the Empire, and some of the best-preserved Roman structures are in Spain, southern France, and northern Africa.[citation needed]

The public baths served hygienic, social and cultural functions.[289] Bathing was the focus of daily socializing.[290] Roman baths were distinguished by a series of rooms that offered communal bathing in three temperatures, with amenities that might include an exercise room, sauna, exfoliation spa, ball court, or outdoor swimming pool. Baths had hypocaust heating: the floors were suspended over hot-air channels.[291] Public baths were part of urban culture throughout the provinces, but in the late 4th century, individual tubs began to replace communal bathing. Christians were advised to go to the baths only for hygiene.[292]

Rich families from Rome usually had two or more houses: a townhouse (domus) and at least one luxury home (villa) outside the city. The domus was a privately owned single-family house, and might be furnished with a private bath (balneum),[291] but it was not a place to retreat from public life.[293] Although some neighbourhoods show a higher concentration of such houses, they were not segregated enclaves. The domus was meant to be visible and accessible. The atrium served as a reception hall in which the paterfamilias (head of household) met with clients every morning.[280] It was a centre of family religious rites, containing a shrine and images of family ancestors.[294] The houses were located on busy public roads, and ground-level spaces were often rented out as shops (tabernae).[295] In addition to a kitchen garden—windowboxes might substitute in the insulae—townhouses typically enclosed a peristyle garden.[296]

The villa by contrast was an escape from the city, and in literature represents a lifestyle that balances intellectual and artistic interests (otium) with an appreciation of nature and agriculture.[297] Ideally a villa commanded a view or vista, carefully framed by the architectural design.[298] It might be located on a working estate, or in a "resort town" on the seacoast.[citation needed]

Augustus' programme of urban renewal, and the growth of Rome's population to as many as one million, was accompanied by nostalgia for rural life. Poetry idealized the lives of farmers and shepherds. Interior decorating often featured painted gardens, fountains, landscapes, vegetative ornament,[298] and animals, rendered accurately enough to be identified by species.[299] On a more practical level, the central government took an active interest in supporting agriculture.[300] Producing food was the priority of land use.[301] Larger farms (latifundia) achieved an economy of scale that sustained urban life.[300] Small farmers benefited from the development of local markets in towns and trade centres. Agricultural techniques such as crop rotation and selective breeding were disseminated throughout the Empire, and new crops were introduced from one province to another.[302]

Maintaining an affordable food supply to the city of Rome had become a major political issue in the late Republic, when the state began to provide a grain dole (Cura Annonae) to citizens who registered for it[300] (about 200,000–250,000 adult males in Rome).[303] The dole cost at least 15% of state revenues,[300] but improved living conditions among the lower classes,[304] and subsidized the rich by allowing workers to spend more of their earnings on the wine and olive oil produced on estates.[300] The grain dole also had symbolic value: it affirmed the emperor's position as universal benefactor, and the right of citizens to share in "the fruits of conquest".[300] The annona, public facilities, and spectacular entertainments mitigated the otherwise dreary living conditions of lower-class Romans, and kept social unrest in check. The satirist Juvenal, however, saw "bread and circuses" (panem et circenses) as emblematic of the loss of republican political liberty:[305]

The public has long since cast off its cares: the people that once bestowed commands, consulships, legions and all else, now meddles no more and longs eagerly for just two things: bread and circuses.[306]

Health and disease

Epidemics were common in the ancient world, and occasional pandemics in the Empire killed millions. The Roman population was unhealthy. About 20 percent—a large percentage by ancient standards—lived in cities, Rome being the largest. The cities were a "demographic sink": the death rate exceeded the birth rate and constant immigration was necessary to maintain the population. Average lifespan is estimated at the mid-twenties, and perhaps more than half of children died before reaching adulthood. Dense urban populations and poor sanitation contributed to disease. Land and sea connections facilitated and sped the transfer of infectious diseases across the empire's territories. The rich were not immune; only two of emperor Marcus Aurelius's fourteen children are known to have reached adulthood.[307]

The importance of a good diet to health was recognized by medical writers such as Galen (2nd century). Views on nutrition were influenced by beliefs like humoral theory.[308] A good indicator of nutrition and disease burden is average height: the average Roman was shorter in stature than the population of pre-Roman Italian societies and medieval Europe.[309]

Food and dining

Most apartments in Rome lacked kitchens, though a charcoal brazier could be used for rudimentary cookery.[310] Prepared food was sold at pubs and bars, inns, and food stalls (tabernae, cauponae, popinae, thermopolia).[311] Carryout and restaurants were for the lower classes; fine dining appeared only at dinner parties in wealthy homes with a chef (archimagirus) and kitchen staff,[312] or banquets hosted by social clubs (collegia).[313]

Most Romans consumed at least 70% of their daily calories in the form of cereals and legumes.[314] Puls (pottage) was considered the food of the Romans,[315] and could be elaborated to produce dishes similar to polenta or risotto.[316] Urban populations and the military preferred bread.[314] By the reign of Aurelian, the state had begun to distribute the annona as a daily ration of bread baked in state factories, and added olive oil, wine, and pork to the dole.[317]

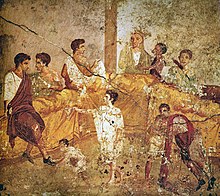

Roman literature focuses on the dining habits of the upper classes,[318] for whom the evening meal (cena) had important social functions.[319] Guests were entertained in a finely decorated dining room (triclinium) furnished with couches. By the late Republic, women dined, reclined, and drank wine along with men.[320] The poet Martial describes a dinner, beginning with the gustatio ("tasting" or "appetizer") salad. The main course was kid, beans, greens, a chicken, and leftover ham, followed by a dessert of fruit and wine.[321] Roman "foodies" indulged in wild game, fowl such as peacock and flamingo, large fish (mullet was especially prized), and shellfish. Luxury ingredients were imported from the far reaches of empire.[322] A book-length collection of Roman recipes is attributed to Apicius, a name for several figures in antiquity that became synonymous with "gourmet".[323]

Refined cuisine could be moralized as a sign of either civilized progress or decadent decline.[324] Most often, because of the importance of landowning in Roman culture, produce—cereals, legumes, vegetables, and fruit—were considered more civilized foods than meat. The Mediterranean staples of bread, wine, and oil were sacralized by Roman Christianity, while Germanic meat consumption became a mark of paganism.[325] Some philosophers and Christians resisted the demands of the body and the pleasures of food, and adopted fasting as an ideal.[326] Food became simpler in general as urban life in the West diminished and trade routes were disrupted;[327] the Church formally discouraged gluttony,[328] and hunting and pastoralism were seen as simple and virtuous.[327]

Spectacles

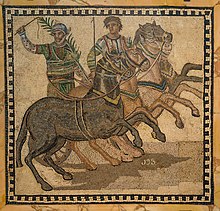

When Juvenal complained that the Roman people had exchanged their political liberty for "bread and circuses", he was referring to the state-provided grain dole and the circenses, events held in the entertainment venue called a circus. The largest such venue in Rome was the Circus Maximus, the setting of horse races, chariot races, the equestrian Troy Game, staged beast hunts (venationes), athletic contests, gladiator combat, and historical re-enactments. From earliest times, several religious festivals had featured games (ludi), primarily horse and chariot races (ludi circenses).[329] The races retained religious significance in connection with agriculture, initiation, and the cycle of birth and death.[r]

Under Augustus, public entertainments were presented on 77 days of the year; by the reign of Marcus Aurelius, this had expanded to 135.[331] Circus games were preceded by an elaborate parade (pompa circensis) that ended at the venue.[332] Competitive events were held also in smaller venues such as the amphitheatre, which became the characteristic Roman spectacle venue, and stadium. Greek-style athletics included footraces, boxing, wrestling, and the pancratium.[333] Aquatic displays, such as the mock sea battle (naumachia) and a form of "water ballet", were presented in engineered pools.[334] State-supported theatrical events (ludi scaenici) took place on temple steps or in grand stone theatres, or in the smaller enclosed theatre called an odeon.[335]

Circuses were the largest structure regularly built in the Roman world.[336] The Flavian Amphitheatre, better known as the Colosseum, became the regular arena for blood sports in Rome.[337] Many Roman amphitheatres, circuses and theatres built in cities outside Italy are visible as ruins today.[337] The local ruling elite were responsible for sponsoring spectacles and arena events, which both enhanced their status and drained their resources.[168] The physical arrangement of the amphitheatre represented the order of Roman society: the emperor in his opulent box; senators and equestrians in reserved advantageous seats; women seated at a remove from the action; slaves given the worst places, and everybody else in-between.[338] The crowd could call for an outcome by booing or cheering, but the emperor had the final say. Spectacles could quickly become sites of social and political protest, and emperors sometimes had to deploy force to put down crowd unrest, most notoriously at the Nika riots in 532.[339]

The chariot teams were known by the colours they wore. Fan loyalty was fierce and at times erupted into sports riots.[341] Racing was perilous, but charioteers were among the most celebrated and well-compensated athletes.[342] Circuses were designed to ensure that no team had an unfair advantage and to minimize collisions (naufragia),[343] which were nonetheless frequent and satisfying to the crowd.[344] The races retained a magical aura through their early association with chthonic rituals: circus images were considered protective or lucky, curse tablets have been found buried at the site of racetracks, and charioteers were often suspected of sorcery.[345] Chariot racing continued into the Byzantine period under imperial sponsorship, but the decline of cities in the 6th and 7th centuries led to its eventual demise.[336]

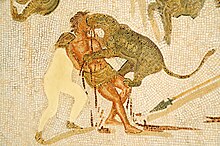

The Romans thought gladiator contests had originated with funeral games and sacrifices. Some of the earliest styles of gladiator fighting had ethnic designations such as "Thracian" or "Gallic".[346] The staged combats were considered munera, "services, offerings, benefactions", initially distinct from the festival games (ludi).[347] To mark the opening of the Colosseum, Titus presented 100 days of arena events, with 3,000 gladiators competing on a single day.[348] Roman fascination with gladiators is indicated by how widely they are depicted on mosaics, wall paintings, lamps, and in graffiti.[349] Gladiators were trained combatants who might be slaves, convicts, or free volunteers.[350] Death was not a necessary or even desirable outcome in matches between these highly skilled fighters, whose training was costly and time-consuming.[351] By contrast, noxii were convicts sentenced to the arena with little or no training, often unarmed, and with no expectation of survival; physical suffering and humiliation were considered appropriate retributive justice.[168] These executions were sometimes staged or ritualized as re-enactments of myths, and amphitheatres were equipped with elaborate stage machinery to create special effects.[168][352]

Modern scholars have found the pleasure Romans took in the "theatre of life and death"[353] difficult to understand.[354] Pliny the Younger rationalized gladiator spectacles as good for the people, "to inspire them to face honourable wounds and despise death, by exhibiting love of glory and desire for victory".[355] Some Romans such as Seneca were critical of the brutal spectacles, but found virtue in the courage and dignity of the defeated fighter[356]—an attitude that finds its fullest expression with the Christians martyred in the arena. Tertullian considered deaths in the arena to be nothing more than a dressed-up form of human sacrifice.[357] Even martyr literature, however, offers "detailed, indeed luxuriant, descriptions of bodily suffering",[358] and became a popular genre at times indistinguishable from fiction.[359]

Recreation

The singular ludus, "play, game, sport, training", had a wide range of meanings such as "word play", "theatrical performance", "board game", "primary school", and even "gladiator training school" (as in Ludus Magnus).[360] Activities for children and young people in the Empire included hoop rolling and knucklebones (astragali or "jacks"). Girls had dolls made of wood, terracotta, and especially bone and ivory.[361] Ball games include trigon and harpastum.[362] People of all ages played board games, including latrunculi ("Raiders") and XII scripta ("Twelve Marks").[363] A game referred to as alea (dice) or tabula (the board) may have been similar to backgammon.[364] Dicing as a form of gambling was disapproved of, but was a popular pastime during the festival of the Saturnalia.[citation needed]

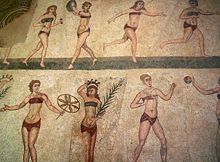

After adolescence, most physical training for males was of a military nature. The Campus Martius originally was an exercise field where young men learned horsemanship and warfare. Hunting was also considered an appropriate pastime. According to Plutarch, conservative Romans disapproved of Greek-style athletics that promoted a fine body for its own sake, and condemned Nero's efforts to encourage Greek-style athletic games.[365] Some women trained as gymnasts and dancers, and a rare few as female gladiators. The "Bikini Girls" mosaic shows young women engaging in routines comparable to rhythmic gymnastics.[s][367] Women were encouraged to maintain health through activities such as playing ball, swimming, walking, or reading aloud (as a breathing exercise).[368]

Clothing

In a status-conscious society like that of the Romans, clothing and personal adornment indicated the etiquette of interacting with the wearer.[369] Wearing the correct clothing reflected a society in good order.[370] There is little direct evidence of how Romans dressed in daily life, since portraiture may show the subject in clothing with symbolic value, and surviving textiles are rare.[371][372]

The toga was the distinctive national garment of the male citizen, but it was heavy and impractical, worn mainly for conducting political or court business and religious rites.[373][371] It was a "vast expanse" of semi-circular white wool that could not be put on and draped correctly without assistance.[373] The drapery became more intricate and structured over time.[374] The toga praetexta, with a purple or purplish-red stripe representing inviolability, was worn by children who had not come of age, curule magistrates, and state priests. Only the emperor could wear an all-purple toga (toga picta).[375]

Ordinary clothing was dark or colourful. The basic garment for all Romans, regardless of gender or wealth, was the simple sleeved tunic, with length differing by wearer.[376] The tunics of poor people and labouring slaves were made from coarse wool in natural, dull shades; finer tunics were made of lightweight wool or linen. A man of the senatorial or equestrian order wore a tunic with two purple stripes (clavi) woven vertically: the wider the stripe, the higher the wearer's status.[376] Other garments could be layered over the tunic. Common male attire also included cloaks and in some regions trousers.[377] In the 2nd century, emperors and elite men are often portrayed wearing the pallium, an originally Greek mantle; women are also portrayed in the pallium. Tertullian considered the pallium an appropriate garment both for Christians, in contrast to the toga, and for educated people.[370][371][378]

Roman clothing styles changed over time.[379] In the Dominate, clothing worn by both soldiers and bureaucrats became highly decorated with geometrical patterns, stylized plant motifs, and in more elaborate examples, human or animal figures.[380] Courtiers of the later Empire wore elaborate silk robes. The militarization of Roman society, and the waning of urban life, affected fashion: heavy military-style belts were worn by bureaucrats as well as soldiers, and the toga was abandoned,[381] replaced by the pallium as a garment embodying social unity.[382]

Arts

Greek art had a profound influence on Roman art.[383] Public art—including sculpture, monuments such as victory columns or triumphal arches, and the iconography on coins—is often analysed for historical or ideological significance.[384] In the private sphere, artistic objects were made for religious dedications, funerary commemoration, domestic use, and commerce.[385] The wealthy advertised their appreciation of culture through artwork and decorative arts in their homes.[386] Despite the value placed on art, even famous artists were of low social status, partly as they worked with their hands.[387]

Portraiture

Portraiture, which survives mainly in sculpture, was the most copious form of imperial art. Portraits during the Augustan period utilize classical proportions, evolving later into a mixture of realism and idealism.[388] Republican portraits were characterized by verism, but as early as the 2nd century BC, Greek heroic nudity was adopted for conquering generals.[389] Imperial portrait sculptures may model a mature head atop a youthful nude or semi-nude body with perfect musculature.[390] Clothed in the toga or military regalia, the body communicates rank or role, not individual characteristics.[391] Women of the emperor's family were often depicted as goddesses or divine personifications.[citation needed]