История Японии

| Часть серии о |

| История Японии |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Japan |

|---|

|

Первые человеческие жители Японского архипелага были обнаружены в эпоху палеолита , около 38–39 000 лет назад. [1] , За периодом Дзёмон названным в честь керамики с маркировкой шнуром , последовал период Яёй в первом тысячелетии до нашей эры, когда из Азии были привезены новые изобретения. В этот период первое известное письменное упоминание о Японии было записано в китайской Книге Хань в первом веке нашей эры.

Примерно в III веке до нашей эры люди яёи с континента иммигрировали на Японский архипелаг и внедрили технологию обработки железа и сельскохозяйственную цивилизацию. [2] Поскольку у них была земледельческая цивилизация, население Яёи начало быстро расти и в конечном итоге вытеснило народ Дзёмон , выходцев из Японского архипелага, которые были охотниками-собирателями. [3] Между четвертым и девятым веками многие королевства и племена Японии постепенно объединились под властью централизованного правительства, номинально контролируемого императором Японии . Созданная в это время императорская династия продолжает существовать и по сей день, хотя и играет почти полностью церемониальную роль. ) была основана новая имперская столица В 794 году в Хэйан-кё (современный Киото , что ознаменовало начало периода Хэйан , продолжавшегося до 1185 года. Период Хэйан считается золотым веком классической японской культуры . Японская религиозная жизнь с этого времени и далее представляла собой смесь местных синтоистских практик и буддизма .

Over the following centuries, the power of the imperial house decreased, passing first to great clans of civilian aristocrats — most notably the Fujiwara — and then to the military clans and their armies of samurai. The Minamoto clan under Minamoto no Yoritomo emerged victorious from the Genpei War of 1180–85, defeating their rival military clan, the Taira. After seizing power, Yoritomo set up his capital in Kamakura and took the title of shōgun. In 1274 and 1281, the Kamakura shogunate withstood two Mongol invasions, but in 1333 it was toppled by a rival claimant to the shogunate, ushering in the Muromachi period. During this period, regional warlords called daimyō grew in power at the expense of the shōgun. Eventually, Japan descended into a period of civil war. Over the course of the late 16th century, Japan was reunified under the leadership of the prominent daimyō Oda Nobunaga and his successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi. After Toyotomi's death in 1598, Tokugawa Ieyasu came to power and was appointed shōgun by the emperor. The Tokugawa shogunate, which governed from Edo (modern Tokyo), presided over a prosperous and peaceful era known as the Edo period (1600–1868). The Tokugawa shogunate imposed a strict class system on Japanese society and cut off almost all contact with the outside world.

Portugal and Japan came into contact in 1543, when the Portuguese became the first Europeans to reach Japan by landing in the southern archipelago. They had a significant impact on Japan, even in this initial limited interaction, introducing firearms to Japanese warfare. The American Perry Expedition in 1853–54 more completely ended Japan's seclusion; this contributed to the fall of the shogunate and the return of power to the emperor during the Boshin War in 1868. The new national leadership of the following Meiji era (1868–1912) transformed the isolated feudal island country into an empire that closely followed Western models and became a great power. Although democracy developed and modern civilian culture prospered during the Taishō period (1912–1926), Japan's powerful military had great autonomy and overruled Japan's civilian leaders in the 1920s and 1930s. The Japanese military invaded Manchuria in 1931, and from 1937 the conflict escalated into a prolonged war with China. Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 led to war with the United States and its allies. Japan's forces soon became overextended, but the military held out in spite of Allied air attacks that inflicted severe damage on population centers. Emperor Hirohito announced Japan's surrender on 15 August 1945, following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet invasion of Manchuria.

The Allies occupied Japan until 1952, during which a new constitution was enacted in 1947 that transformed Japan into the constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy it is today. After 1955, Japan enjoyed very high economic growth under the governance of the Liberal Democratic Party, and became a world economic powerhouse. Since the Lost Decade of the 1990s, Japanese economic growth has slowed.

Prehistoric and ancient Japan[edit]

Paleolithic period[edit]

Hunter-gatherers arrived in Japan in Paleolithic times, with the oldest evidence dating to around 38–40,000 years ago.[1] Little evidence of their presence remains, as Japan's acidic soils are inhospitable to the process of fossilization. However, the discovery of unique edge-ground axes in Japan dated to over 30,000 years ago may be evidence of the first Homo sapiens in Japan.[4] Early humans likely arrived in Japan by sea on watercraft.[5] Evidence of human habitation has been dated to 32,000 years ago in Okinawa's Yamashita Cave[6] and up to 20,000 years ago on Ishigaki Island's Shiraho Saonetabaru Cave.[7]

Jōmon period[edit]

The Jōmon period of prehistoric Japan spans from roughly 13,000 BC[8] to about 1,000 BC.[9] Japan was inhabited by a predominantly hunter-gatherer culture that reached a considerable degree of sedentism and cultural complexity.[10] The name Jōmon, meaning "cord-marked", was first applied by American scholar Edward S. Morse, who discovered shards of pottery in 1877.[11] The pottery style characteristic of the first phases of Jōmon culture was decorated by impressing cords into the surface of wet clay.[12] Jōmon pottery is generally accepted to be among the oldest in East Asia and the world.[13]

- A vase from the early Jōmon period (11000–7000 BC)

- Middle Jōmon vase (2000 BC)

- Dogū figurine of the late Jōmon period (1000–400 BC)

Yayoi period[edit]

The advent of the Yayoi people from the Asian mainland brought fundamental transformations to the Japanese archipelago. The millennial achievements of the Neolithic Revolution took hold of the islands in a relatively short span of centuries, particularly with the development of rice cultivation[14] and metallurgy. Until recently, the onset of this wave of cultural and technological changes was thought to have begun around 400 BC.[15] Radio-carbon evidence now suggests that the new phase started some 500 years earlier, between 1,000 and 800 BC.[16][17] Endowed with bronze and iron weapons and tools initially imported from China and the Korean peninsula, the Yayoi radiated out from northern Kyūshū, gradually supplanting the Jōmon.[18] They also introduced weaving and silk production,[19] new woodworking methods,[16] glassmaking technology,[16] and new architectural styles.[20] The expansion of the Yayoi appears to have brought about a fusion with the indigenous Jōmon, resulting in a small genetic admixture.[21]

These Yayoi technologies originated on the Asian mainland. There is debate among scholars as to what degree their spread can be attributed to migration or to cultural diffusion. The migration theory is supported by genetic and linguistic studies.[16] Historian Hanihara Kazurō has suggested that the annual immigrant influx from the continent range from 350 to 3,000.[22]

The population of Japan began to increase rapidly, perhaps with a 10-fold rise over the Jōmon. Calculations of the increasing population size by the end of the Yayoi period have varied from 1 to 4 million.[23] Skeletal remains from the late Jōmon period reveal a deterioration in already poor standards of health and nutrition, whereas contemporaneous Yayoi archaeological sites possess large structures suggestive of grain storehouses. This shift was accompanied by an increase in both the stratification of society and tribal warfare, indicated by segregated gravesites and military fortifications.[16]

During the Yayoi period, the Yayoi tribes gradually coalesced into a number of kingdoms. The earliest written work to unambiguously mention Japan, the Book of Han, published in 111 AD, states that one hundred kingdoms comprised Japan, which is referred to as Wa. A later Chinese work of history, the Book of Wei, states that by 240 AD, the powerful kingdom of Yamatai, ruled by the female monarch Himiko, had gained ascendancy over the others, though modern historians continue to debate its location and other aspects of its depiction in the Book of Wei.[24]

Kofun period (c. 250–538)[edit]

During the subsequent Kofun period, Japan gradually unified under a single territory. The symbol of the growing power of Japan's new leaders was the kofun burial mounds they constructed from around 250 AD onwards.[25] Many were of massive scale, such as the Daisenryō Kofun, a 486 m-long keyhole-shaped burial mound that took huge teams of laborers fifteen years to complete. It is commonly accepted that the tomb was built for Emperor Nintoku.[26] The kofun were often surrounded by and filled with numerous haniwa clay sculptures, often in the shape of warriors and horses.[25]

The center of the unified state was Yamato in the Kinai region of central Japan.[25] The rulers of the Yamato state were a hereditary line of emperors who still reign as the world's longest dynasty. The rulers of the Yamato extended their power across Japan through military conquest, but their preferred method of expansion was to convince local leaders to accept their authority in exchange for positions of influence in the government.[27] Many of the powerful local clans who joined the Yamato state became known as the uji.[28]

These leaders sought and received formal diplomatic recognition from China, and Chinese accounts record five successive such leaders as the Five kings of Wa. Craftsmen and scholars from China and the Three Kingdoms of Korea played an important role in transmitting continental technologies and administrative skills to Japan during this period.[28]

Historians agree that there was a big struggle between the Yamato federation and the Izumo Federation centuries before written records.[29]

Classical Japan[edit]

Asuka period (538–710)[edit]

The Asuka period began as early as 538 AD with the introduction of the Buddhist religion from the Korean kingdom of Baekje.[30] Since then, Buddhism has coexisted with Japan's native Shinto religion, in what is today known as Shinbutsu-shūgō.[31] The period draws its name from the de facto imperial capital, Asuka, in the Kinai region.[32]

The Buddhist Soga clan took over the government in the 580s and controlled Japan from behind the scenes for nearly sixty years.[33] Prince Shōtoku, an advocate of Buddhism and of the Soga cause, who was of partial Soga descent, served as regent and de facto leader of Japan from 594 to 622. Shōtoku authored the Seventeen-article constitution, a Confucian-inspired code of conduct for officials and citizens, and attempted to introduce a merit-based civil service called the Cap and Rank System.[34] In 607, Shōtoku offered a subtle insult to China by opening his letter with the phrase, "The ruler of the land of the rising sun addresses the ruler of the land of the setting sun" as seen in the kanji characters for Japan (Nippon).[35] By 670, a variant of this expression, Nihon, established itself as the official name of the nation, which has persisted to this day.[36]

In 645, the Soga clan were overthrown in a coup launched by Prince Naka no Ōe and Fujiwara no Kamatari, the founder of the Fujiwara clan.[37] Their government devised and implemented the far-reaching Taika Reforms. The Reform began with land reform, based on Confucian ideas and philosophies from China. It nationalized all land in Japan, to be distributed equally among cultivators, and ordered the compilation of a household registry as the basis for a new system of taxation.[38] The true aim of the reforms was to bring about greater centralization and to enhance the power of the imperial court, which was also based on the governmental structure of China. Envoys and students were dispatched to China to learn about Chinese writing, politics, art, and religion. After the reforms, the Jinshin War of 672, a bloody conflict between Prince Ōama and his nephew Prince Ōtomo, two rivals to the throne, became a major catalyst for further administrative reforms.[37] These reforms culminated with the promulgation of the Taihō Code, which consolidated existing statutes and established the structure of the central government and its subordinate local governments.[39] These legal reforms created the ritsuryō state, a system of Chinese-style centralized government that remained in place for half a millennium.[37]

The art of the Asuka period embodies the themes of Buddhist art.[40] One of the most famous works is the Buddhist temple of Hōryū-ji, commissioned by Prince Shōtoku and completed in 607 AD. It is now the oldest wooden structure in the world.[41]

Nara period (710–794)[edit]

In 710, the government constructed a grandiose new capital at Heijō-kyō (modern Nara) modeled on Chang'an, the capital of the Chinese Tang dynasty. During this period, the first two books produced in Japan appeared: the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki,[42] which contain chronicles of legendary accounts of early Japan and its creation myth, which describes the imperial line as descendants of the gods.[43] The Man'yōshū was compiled in the latter half of the eighth century, which is widely considered the finest collection of Japanese poetry.[44]

During this period, Japan suffered a series of natural disasters, including wildfires, droughts, famines, and outbreaks of disease, such as a smallpox epidemic in 735–737 that killed over a quarter of the population.[45] Emperor Shōmu (r. 724–749) feared his lack of piousness had caused the trouble and so increased the government's promotion of Buddhism, including the construction of the temple Tōdai-ji in 752.[46] The funds to build this temple were raised in part by the influential Buddhist monk Gyōki, and once completed it was used by the Chinese monk Ganjin as an ordination site.[47] Japan nevertheless entered a phase of population decline that continued well into the following Heian period.[48]There was also a serious attempt to overthrow the Imperial house during the middle Nara period. During the 760s, monk Dōkyō tried to establish his own dynasty with the aid of Empress Shōtoku, but after her death in 770 he lost all his power and was exiled. The Fujiwara clan furthermore consolidated its power.

Heian period (794–1185)[edit]

The Heian period (平安時代, Heian jidai) is the last division of classical Japanese history, running from 794 to 1185. It followed the Nara period, beginning when the 50th emperor, Emperor Kammu, moved the capital of Japan to Heian-kyō (modern Kyoto). Heian (平安) means "peace" in Japanese.

In 784, the capital moved briefly to Nagaoka-kyō, then again in 794 to Heian-kyō (modern Kyoto), which remained the capital until 1868.[49] Political power within the court soon passed to the Fujiwara clan, a family of court nobles who grew increasingly close to the imperial family through intermarriage.[50] Between 812 and 814 CE, a smallpox epidemic killed almost half of the Japanese population.[51]

In 858, Fujiwara no Yoshifusa had himself declared sesshō ("regent") to the underage emperor. His son Fujiwara no Mototsune created the office of kampaku, which could rule in the place of an adult reigning emperor. Fujiwara no Michinaga, an exceptional statesman who became kampaku in 996, governed during the height of the Fujiwara clan's power[52] and married four of his daughters to emperors, current and future.[50] The Fujiwara clan held on to power until 1086, when Emperor Shirakawa ceded the throne to his son Emperor Horikawa but continued to exercise political power, establishing the practice of cloistered rule,[53] by which the reigning emperor would function as a figurehead while the real authority was held by a retired predecessor behind the scenes.[52]

Throughout the Heian period, the power of the imperial court declined. The court became so self-absorbed with power struggles and with the artistic pursuits of court nobles that it neglected the administration of government outside the capital.[50] The nationalization of land undertaken as part of the ritsuryō state decayed as various noble families and religious orders succeeded in securing tax-exempt status for their private shōen manors.[52] By the eleventh century, more land in Japan was controlled by shōen owners than by the central government. The imperial court was thus deprived of the tax revenue to pay for its national army. In response, the owners of the shōen set up their own armies of samurai warriors.[54] Two powerful noble families that had descended from branches of the imperial family,[55] the Taira and Minamoto clans, acquired large armies and many shōen outside the capital. The central government began to use these two warrior clans to suppress rebellions and piracy.[56] Japan's population stabilized during the late Heian period after hundreds of years of decline.[57]

During the early Heian period, the imperial court successfully consolidated its control over the Emishi people of northern Honshu.[58] Ōtomo no Otomaro was the first man the court granted the title of seii tai-shōgun ("Great Barbarian Subduing General").[59] In 802, seii tai-shōgun Sakanoue no Tamuramaro subjugated the Emishi people, who were led by Aterui.[58] By 1051, members of the Abe clan, who occupied key posts in the regional government, were openly defying the central authority. The court requested the Minamoto clan to engage the Abe clan, whom they defeated in the Former Nine Years' War.[60] The court thus temporarily reasserted its authority in northern Japan. Following another civil war – the Later Three-Year War – Fujiwara no Kiyohira took full power; his family, the Northern Fujiwara, controlled northern Honshu for the next century from their capital Hiraizumi.[61]

In 1156, a dispute over succession to the throne erupted and the two rival claimants (Emperor Go-Shirakawa and Emperor Sutoku) hired the Taira and Minamoto clans in the hopes of securing the throne by military force. During this war, the Taira clan led by Taira no Kiyomori defeated the Minamoto clan. Kiyomori used his victory to accumulate power for himself in Kyoto and even installed his own grandson Antoku as emperor. The outcome of this war led to the rivalry between the Minamoto and Taira clans. As a result, the dispute and power struggle between both clans led to the Heiji rebellion in 1160. In 1180, Taira no Kiyomori was challenged by an uprising led by Minamoto no Yoritomo, a member of the Minamoto clan whom Kiyomori had exiled to Kamakura.[62] Though Taira no Kiyomori died in 1181, the ensuing bloody Genpei War between the Taira and Minamoto families continued for another four years. The victory of the Minamoto clan was sealed in 1185, when a force commanded by Yoritomo's younger brother, Minamoto no Yoshitsune, scored a decisive victory at the naval Battle of Dan-no-ura. Yoritomo and his retainers thus became the de facto rulers of Japan.[63]

Heian culture[edit]

During the Heian period, the imperial court was a vibrant center of high art and culture.[64] Its literary accomplishments include the poetry collection Kokinshū and the Tosa Diary, both associated with the poet Ki no Tsurayuki, as well as Sei Shōnagon's collection of miscellany The Pillow Book,[65] and Murasaki Shikibu's Tale of Genji, often considered the masterpiece of Japanese literature.[66]

The development of the kana written syllabaries was part of a general trend of declining Chinese influence during the Heian period. The official Japanese missions to Tang dynasty of China, which began in the year 630,[67] ended during the ninth century, though informal missions of monks and scholars continued, and thereafter the development of native Japanese forms of art and poetry accelerated.[68] A major architectural achievement, apart from Heian-kyō itself, was the temple of Byōdō-in built in 1053 in Uji.[69]

Feudal Japan[edit]

Kamakura period (1185–1333)[edit]

Upon the consolidation of power, Minamoto no Yoritomo chose to rule in concert with the Imperial Court in Kyoto. Though Yoritomo set up his own government in Kamakura in the Kantō region located in eastern Japan, its power was legally authorized by the Imperial court in Kyoto in several occasions. In 1192, the emperor declared Yoritomo seii tai-shōgun (征夷大将軍; Eastern Barbarian Subduing Great General), abbreviated as shōgun.[70] Yoritomo's government was called the bakufu (幕府 ("tent government")), referring to the tents where his soldiers encamped. The English term shogunate refers to the bakufu.[71] Japan remained largely under military rule until 1868.[72]

Legitimacy was conferred on the shogunate by the Imperial court, but the shogunate was the de facto rulers of the country. The court maintained bureaucratic and religious functions, and the shogunate welcomed participation by members of the aristocratic class. The older institutions remained intact in a weakened form, and Kyoto remained the official capital. This system has been contrasted with the "simple warrior rule" of the later Muromachi period.[70]

Yoritomo soon turned on Yoshitsune, who was initially harbored by Fujiwara no Hidehira, the grandson of Kiyohira and the de facto ruler of northern Honshu. In 1189, after Hidehira's death, his successor Yasuhira attempted to curry favor with Yoritomo by attacking Yoshitsune's home. Although Yoshitsune was killed, Yoritomo still invaded and conquered the Northern Fujiwara clan's territories.[73] In subsequent centuries, Yoshitsune would become a legendary figure, portrayed in countless works of literature as an idealized tragic hero.[74]

After Yoritomo's death in 1199, the office of shogun weakened. Behind the scenes, Yoritomo's wife Hōjō Masako became the true power behind the government. In 1203, her father, Hōjō Tokimasa, was appointed regent to the shogun, Yoritomo's son Minamoto no Sanetomo. Henceforth, the Minamoto shoguns became puppets of the Hōjō regents, who wielded actual power.[75]

The regime that Yoritomo had established, and which was kept in place by his successors, was decentralized and feudalistic in structure, in contrast with the earlier ritsuryō state. Yoritomo selected the provincial governors, known under the titles of shugo or jitō,[76] from among his close vassals, the gokenin. The Kamakura shogunate allowed its vassals to maintain their own armies and to administer law and order in their provinces on their own terms.[77]

In 1221, the retired Emperor Go-Toba instigated what became known as the Jōkyū War, a rebellion against the shogunate, in an attempt to restore political power to the court. The rebellion was a failure and led to Go-Toba being exiled to Oki Island, along with two other emperors, the retired Emperor Tsuchimikado and Emperor Juntoku, who were exiled to Tosa Province and Sado Island respectively.[78] The shogunate further consolidated its political power relative to the Kyoto aristocracy.[79]

The samurai armies of the whole nation were mobilized in 1274 and 1281 to confront two full-scale invasions launched by Kublai Khan of the Mongol Empire.[80] Though outnumbered by an enemy equipped with superior weaponry, the Japanese fought the Mongols to a standstill in Kyushu on both occasions until the Mongol fleet was destroyed by typhoons called kamikaze, meaning "divine wind". In spite of the Kamakura shogunate's victory, the defense so depleted its finances that it was unable to provide compensation to its vassals for their role in the victory. This had permanent negative consequences for the shogunate's relations with the samurai class.[81] Discontent among the samurai proved decisive in ending the Kamakura shogunate. In 1333, Emperor Go-Daigo launched a rebellion in the hope of restoring full power to the imperial court. The shogunate sent General Ashikaga Takauji to quell the revolt, but Takauji and his men instead joined forces with Emperor Go-Daigo and overthrew the Kamakura shogunate.[82]

Japan nevertheless entered a period of prosperity and population growth starting around 1250.[83] In rural areas, the greater use of iron tools and fertilizer, improved irrigation techniques, and double-cropping increased productivity and rural villages grew.[84] Fewer famines and epidemics allowed cities to grow and commerce to boom.[83] Buddhism, which had been largely a religion of the elites, was brought to the masses by prominent monks, such as Hōnen (1133–1212), who established Pure Land Buddhism in Japan, and Nichiren (1222–1282), who founded Nichiren Buddhism. Zen Buddhism spread widely among the samurai class.[85]

- The Illustrated Account of the Mongol Invasion (Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba)

- Ancient drawing depicting a samurai battling forces of the Mongol Empire

- Samurai Mitsui Sukenaga (right) defeating the Mongolian invasion army (left)

- Shiraishi clan

Muromachi period (1333–1568)[edit]

Takauji and many other samurai soon became dissatisfied with Emperor Go-Daigo's Kenmu Restoration, an ambitious attempt to monopolize power in the imperial court. Takauji rebelled after Go-Daigo refused to appoint him shōgun. In 1338, Takauji captured Kyoto and installed a rival member of the imperial family to the throne, Emperor Kōmyō, who did appoint him shogun.[86] Go-Daigo responded by fleeing to the southern city of Yoshino, where he set up a rival government. This ushered in a prolonged period of conflict between the Northern Court and the Southern Court.[87]

Takauji set up his shogunate in the Muromachi district of Kyoto. However, the shogunate was faced with the twin challenges of fighting the Southern Court and of maintaining its authority over its own subordinate governors.[87] Like the Kamakura shogunate, the Muromachi shogunate appointed its allies to rule in the provinces, but these men increasingly styled themselves as feudal lords—called daimyōs—of their domains and often refused to obey the shogun.[88] The Ashikaga shogun who was most successful at bringing the country together was Takauji's grandson Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, who came to power in 1368 and remained influential until his death in 1408. Yoshimitsu expanded the power of the shogunate and in 1392, brokered a deal to bring the Northern and Southern Courts together and end the civil war. Henceforth, the shogunate kept the emperor and his court under tight control.[87]

During the final century of the Ashikaga shogunate the country descended into another, more violent period of civil war. This started in 1467 when the Ōnin War broke out over who would succeed the ruling shogun. The daimyōs each took sides and burned Kyoto to the ground while battling for their preferred candidate. By the time the succession was settled in 1477, the shogun had lost all power over the daimyō, who now ruled hundreds of independent states throughout Japan.[89] During this Warring States period, daimyōs fought among themselves for control of the country.[90] Some of the most powerful daimyōs of the era were Uesugi Kenshin and Takeda Shingen.[91] One enduring symbol of this era was the ninja, skilled spies and assassins hired by daimyōs. Few definite historical facts are known about the secretive lifestyles of the ninja, who became the subject of many legends.[92] In addition to the daimyōs, rebellious peasants and "warrior monks" affiliated with Buddhist temples also raised their own armies.[93]

Nanban trade[edit]

Amid this on-going anarchy, a trading ship was blown off course and landed in 1543 on the Japanese island of Tanegashima, just south of Kyushu. The three Portuguese traders on board were the first Europeans to set foot in Japan.[94] Soon European traders would introduce many new items to Japan, most importantly the musket.[95] By 1556, the daimyōs were using about 300,000 muskets in their armies.[96] The Europeans also brought Christianity, which soon came to have a substantial following in Japan reaching 350,000 believers. In 1549 the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier disembarked in Kyushu.

Initiating direct commercial and cultural exchange between Japan and the West, the first map made of Japan in the west was represented in 1568 by the Portuguese cartographer Fernão Vaz Dourado.[97]

The Portuguese were allowed to trade and create colonies where they could convert new believers into the Christian religion. The civil war status in Japan greatly benefited the Portuguese, as well as several competing gentlemen who sought to attract Portuguese black boats and their trade to their domains. Initially, the Portuguese stayed on the lands belonging to Matsura Takanobu, Firando (Hirado),[98] and in the province of Bungo, lands of Ōtomo Sōrin, but in 1562 they moved to Yokoseura when the Daimyô there, Omura Sumitada, offered to be the first lord to convert to Christianity, adopting the name of Dom Bartolomeu. In 1564, he faced a rebellion instigated by the Buddhist clergy and Yokoseura was destroyed.

In 1561 forces under Ōtomo Sōrin attacked the castle in Moji with an alliance with the Portuguese, who provided three ships, with a crew of about 900 men and more than 50 cannons. This is thought to be the first bombardment by foreign ships on Japan.[99] The first recorded naval battle between Europeans and the Japanese occurred in 1565. In the Battle of Fukuda Bay, the daimyō Matsura Takanobu attacked two Portuguese trade vessels at Hirado port.[100] The engagement led the Portuguese traders to find a safe harbor for their ships that took them to Nagasaki.

In 1571, Dom Bartolomeu, also known as Ōmura Sumitada, guaranteed a little land in the small fishing village of "Nagasáqui" to the Jesuits, who divided it into six areas. They could use the land to receive Christians exiled from other territories, as well as for Portuguese merchants. The Jesuits built a chapel and a school under the name of São Paulo, like those in Goa and Malacca. By 1579, Nagasáqui had four hundred houses, and some Portuguese had gotten married. Fearful that Nagasaki could fall into the hands of its rival Takanobu, Omura Sumitada (Dom Bartolomeu) decided to guarantee the city directly to the Jesuits in 1580.[101] After a few years, the Jesuits came to realize that if they understood the language they would achieve more conversions to the Catholic religion. Jesuits such as João Rodrigues wrote a Japanese dictionary. Thus Portuguese became the first Western language to have such a dictionary when it was published in Nagasaki in 1603.[102]

Oda Nobunaga used European technology and firearms to conquer many other daimyōs; his consolidation of power began what was known as the Azuchi–Momoyama period (1573–1603). After Nobunaga was assassinated in 1582 by Akechi Mitsuhide, his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi unified the nation in 1590 and launched two unsuccessful invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1597. Before the invasion, Hideyoshi tried to hire two Portuguese galleons to join the invasion but the Portuguese refused the offer.[103]

Tokugawa Ieyasu served as regent for Hideyoshi's son Toyotomi Hideyori and used his position to gain political and military support. When open war broke out, Ieyasu defeated rival clans in the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600. In 1603 the Tokugawa shogunate at Edo enacted measures including buke shohatto, as a code of conduct to control the autonomous daimyōs, and in 1639 the isolationist sakoku ("closed country") policy that spanned the two and a half centuries of tenuous political unity known as the Edo period (1603–1868), this act ended Portuguese influence after 100 years in Japanese territory, and also aimed to limit the political presence of any foreign power.[94]

Muromachi culture[edit]

In spite of the war, Japan's relative economic prosperity, which had begun in the Kamakura period, continued well into the Muromachi period. By 1450 Japan's population stood at ten million, compared to six million at the end of the thirteenth century.[83] Commerce flourished, including considerable trade with China and Korea.[104] Because the daimyōs and other groups within Japan were minting their own coins, Japan began to transition from a barter-based to a currency-based economy.[105] During the period, some of Japan's most representative art forms developed, including ink wash painting, ikebana flower arrangement, the tea ceremony, Japanese gardening, bonsai, and Noh theater.[106] Though the eighth Ashikaga shogun, Yoshimasa, was an ineffectual political and military leader, he played a critical role in promoting these cultural developments.[107] He had the famous Kinkaku-ji or "Temple of the Golden Pavilion" built in Kyoto in 1397.[108]

Azuchi–Momoyama period (1568-1600)[edit]

During the second half of the 16th century, Japan gradually reunified under two powerful warlords: Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The period takes its name from Nobunaga's headquarters, Azuchi Castle, and Hideyoshi's headquarters, Momoyama Castle.[71]

Nobunaga was the daimyō of the small province of Owari. He burst onto the scene suddenly, in 1560, when, during the Battle of Okehazama, his army defeated a force several times its size led by the powerful daimyō Imagawa Yoshimoto.[109] Nobunaga was renowned for his strategic leadership and his ruthlessness. He encouraged Christianity to incite hatred toward his Buddhist enemies and to forge strong relationships with European arms merchants. He equipped his armies with muskets and trained them with innovative tactics.[110] He promoted talented men regardless of their social status, including his peasant servant Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who became one of his best generals.[111]

The Azuchi–Momoyama period began in 1568, when Nobunaga seized Kyoto and thus effectively brought an end to the Ashikaga shogunate.[109] He was well on his way towards his goal of reuniting all Japan when, in 1582, one of his own officers, Akechi Mitsuhide, killed him during an abrupt attack on his encampment. Hideyoshi avenged Nobunaga by crushing Akechi's uprising and emerged as Nobunaga's successor.[112] Hideyoshi completed the reunification of Japan by conquering Shikoku, Kyushu, and the lands of the Hōjō family in eastern Japan.[113] He launched sweeping changes to Japanese society, including the confiscation of swords from the peasantry, new restrictions on daimyōs, persecutions of Christians, a thorough land survey, and a new law effectively forbidding the peasants and samurai from changing their social class.[114] Hideyoshi's land survey designated all those who were cultivating the land as being "commoners", an act which effectively granted freedom to most of Japan's slaves.[115]

As Hideyoshi's power expanded, he dreamed of conquering China and launched two massive invasions of Korea starting in 1592. Hideyoshi failed to defeat the Chinese and Korean armies on the Korean Peninsula and the war ended after his death in 1598.[116] In the hope of founding a new dynasty, Hideyoshi had asked his most trusted subordinates to pledge loyalty to his infant son Toyotomi Hideyori. Despite this, almost immediately after Hideyoshi's death, war broke out between Hideyori's allies and those loyal to Tokugawa Ieyasu, a daimyō and a former ally of Hideyoshi.[117] Tokugawa Ieyasu won a decisive victory at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, ushering in 268 uninterrupted years of rule by the Tokugawa clan.[118]

Early modern Japan[edit]

Edo period (1600–1868)[edit]

The Edo period was characterized by relative peace and stability[119] under the tight control of the Tokugawa shogunate, which ruled from the eastern city of Edo (modern Tokyo).[120] In 1603, Emperor Go-Yōzei declared Tokugawa Ieyasu shōgun, and Ieyasu abdicated two years later to groom his son as the second shōgun of what became a long dynasty.[121] Nevertheless, it took time for the Tokugawas to consolidate their rule. In 1609, the shōgun gave the daimyō of the Satsuma Domain permission to invade the Ryukyu Kingdom for perceived insults towards the shogunate; the Satsuma victory began 266 years of Ryukyu's dual subordination to Satsuma and China.[99][122] Ieyasu led the Siege of Osaka that ended with the destruction of the Toyotomi clan in 1615.[123] Soon after the shogunate promulgated the Laws for the Military Houses, which imposed tighter controls on the daimyōs,[124] and the alternate attendance system, which required each daimyō to spend every other year in Edo.[125] Even so, the daimyōs continued to maintain a significant degree of autonomy in their domains.[126] The central government of the shogunate in Edo, which quickly became the most populous city in the world,[120] took counsel from a group of senior advisors known as rōjū and employed samurai as bureaucrats.[127] The emperor in Kyoto was funded lavishly by the government but was allowed no political power.[128]

The Tokugawa shogunate went to great lengths to suppress social unrest. Harsh penalties, including crucifixion, beheading, and death by boiling, were decreed for even the most minor offenses, though criminals of high social class were often given the option of seppuku ("self-disembowelment"), an ancient form of suicide that became ritualized.[125] Christianity, which was seen as a potential threat, was gradually clamped down on until finally, after the Christian-led Shimabara Rebellion of 1638, the religion was completely outlawed.[129] To prevent further foreign ideas from sowing dissent, the third Tokugawa shogun, Iemitsu, implemented the sakoku ("closed country") isolationist policy under which Japanese people were not allowed to travel abroad, return from overseas, or build ocean-going vessels.[130] The only Europeans allowed on Japanese soil were the Dutch, who were granted a single trading post on the island of Dejima at Nagasaki from 1634 to 1854.[131] China and Korea were the only other countries permitted to trade,[132] and many foreign books were banned from import.[126]

During the first century of Tokugawa rule, Japan's population doubled to thirty million, mostly because of agricultural growth; the population remained stable for the rest of the period.[133] The shogunate's construction of roads, elimination of road and bridge tolls, and standardization of coinage promoted commercial expansion that also benefited the merchants and artisans of the cities.[134] City populations grew,[135] but almost ninety percent of the population continued to live in rural areas.[136] Both the inhabitants of cities and of rural communities would benefit from one of the most notable social changes of the Edo period: increased literacy and numeracy. The number of private schools greatly expanded, particularly those attached to temples and shrines, and raised literacy to thirty percent. This may have been the world's highest rate at the time[137] and drove a flourishing commercial publishing industry, which grew to produce hundreds of titles per year.[138] In the area of numeracy – approximated by an index measuring people's ability to report an exact rather than a rounded age (age-heaping method), and which level shows a strong correlation to later economic development of a country – Japan's level was comparable to that of north-west European countries, and moreover, Japan's index came close to the 100 percent mark throughout the nineteenth century. These high levels of both literacy and numeracy were part of the socio-economical foundation for Japan's strong growth rates during the following century.[139]

Culture and philosophy[edit]

The Edo period was a time of cultural flourishing, as the merchant classes grew in wealth and began spending their income on cultural and social pursuits.[140][141] Members of the merchant class who patronized culture and entertainment were said to live hedonistic lives, which came to be called the ukiyo ("floating world").[142] This lifestyle inspired ukiyo-zōshi popular novels and ukiyo-e art, the latter of which were often woodblock prints[143] that progressed to greater sophistication and use of multiple printed colors.[144]

Forms of theater such as kabuki and bunraku puppet theater became widely popular.[145] These new forms of entertainment were (at the time) accompanied by short songs (kouta) and music played on the shamisen, a new import to Japan in 1600.[146] Haiku, whose greatest master is generally agreed to be Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694), also rose as a major form of poetry.[147] Geisha, a new profession of entertainers, also became popular. They would provide conversation, sing, and dance for customers, though they would not sleep with them.[148]

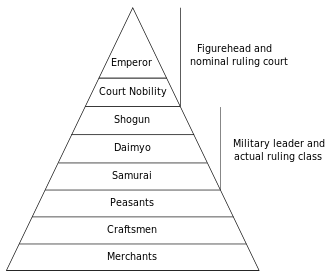

The Tokugawas sponsored and were heavily influenced by Neo-Confucianism, which led the government to divide society into four classes based on the four occupations.[149] The samurai class claimed to follow the ideology of bushido, literally "the way of the warrior".[150]

Decline and fall of the shogunate[edit]

By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the shogunate showed signs of weakening.[151] The dramatic growth of agriculture that had characterized the early Edo period had ended,[133] and the government handled the devastating Tenpō famines poorly.[151] Peasant unrest grew and government revenues fell.[152] The shogunate cut the pay of the already financially distressed samurai, many of whom worked side jobs to make a living.[153] Discontented samurai were soon to play a major role in engineering the downfall of the Tokugawa shogunate.[154]

At the same time, the people drew inspiration from new ideas and fields of study. Dutch books brought into Japan stimulated interest in Western learning, called rangaku or "Dutch learning".[155] The physician Sugita Genpaku, for instance, used concepts from Western medicine to help spark a revolution in Japanese ideas of human anatomy.[156] The scholarly field of kokugaku or "national learning", developed by scholars such as Motoori Norinaga and Hirata Atsutane, promoted what it asserted were native Japanese values. For instance, it criticized the Chinese-style Neo-Confucianism advocated by the shogunate and emphasized the Emperor's divine authority, which the Shinto faith taught had its roots in Japan's mythic past, which was referred to as the "Age of the Gods".[157]

The arrival in 1853 of a fleet of American ships commanded by Commodore Matthew C. Perry threw Japan into turmoil. The US government aimed to end Japan's isolationist policies. The shogunate had no defense against Perry's gunboats and had to agree to his demands that American ships be permitted to acquire provisions and trade at Japanese ports.[151] The Western powers imposed what became known as "unequal treaties" on Japan which stipulated that Japan must allow citizens of these countries to visit or reside on Japanese territory and must not levy tariffs on their imports or try them in Japanese courts.[158]

The shogunate's failure to oppose the Western powers angered many Japanese, particularly those of the southern domains of Chōshū and Satsuma.[159] Many samurai there, inspired by the nationalist doctrines of the kokugaku school, adopted the slogan of sonnō jōi ("revere the emperor, expel the barbarians").[160] The two domains went on to form an alliance. In August 1866, soon after becoming shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, struggled to maintain power as civil unrest continued.[161] The Chōshū and Satsuma domains in 1868 convinced the young Emperor Meiji and his advisors to issue a rescript calling for an end to the Tokugawa shogunate. The armies of Chōshū and Satsuma soon marched on Edo and the ensuing Boshin War led to the fall of the shogunate.[162]

Modern Japan[edit]

Meiji period (1868–1912)[edit]

The emperor was restored to nominal supreme power,[163] and in 1869, the imperial family moved to Edo, which was renamed Tokyo ("eastern capital").[164] However, the most powerful men in the government were former samurai from Chōshū and Satsuma rather than the emperor, who was fifteen in 1868.[163] These men, known as the Meiji oligarchs, oversaw the dramatic changes Japan would experience during this period.[165] The leaders of the Meiji government desired Japan to become a modern nation-state that could stand equal to the Western imperialist powers.[166] Among them were Ōkubo Toshimichi and Saigō Takamori from Satsuma, as well as Kido Takayoshi, Ito Hirobumi, and Yamagata Aritomo from Chōshū.[163]

Political and social changes[edit]

The Meiji government abolished the Edo class structure[167] and replaced the feudal domains of the daimyōs with prefectures.[164] It instituted comprehensive tax reform and lifted the ban on Christianity.[167] Major government priorities also included the introduction of railways, telegraph lines, and a universal education system.[168] The Meiji government promoted widespread Westernization[169] and hired hundreds of advisers from Western nations with expertise in such fields as education, mining, banking, law, military affairs, and transportation to remodel Japan's institutions.[170] The Japanese adopted the Gregorian calendar, Western clothing, and Western hairstyles.[171] One leading advocate of Westernization was the popular writer Fukuzawa Yukichi.[172] As part of its Westernization drive, the Meiji government enthusiastically sponsored the importation of Western science, above all medical science. In 1893, Kitasato Shibasaburō established the Institute for Infectious Diseases, which would soon become world-famous,[173] and in 1913, Hideyo Noguchi proved the link between syphilis and paresis.[174] Furthermore, the introduction of European literary styles to Japan sparked a boom in new works of prose fiction. Characteristic authors of the period included Futabatei Shimei and Mori Ōgai,[175] although the most famous of the Meiji era writers was Natsume Sōseki,[176] who wrote satirical, autobiographical, and psychological novels[177] combining both the older and newer styles.[178] Ichiyō Higuchi, a leading female author, took inspiration from earlier literary models of the Edo period.[179]

Government institutions developed rapidly in response to the Freedom and People's Rights Movement, a grassroots campaign demanding greater popular participation in politics. The leaders of this movement included Itagaki Taisuke and Ōkuma Shigenobu.[180] Itō Hirobumi, the first Prime Minister of Japan, responded by writing the Meiji Constitution, which was promulgated in 1889. The new constitution established an elected lower house, the House of Representatives, but its powers were restricted. Only two percent of the population were eligible to vote, and legislation proposed in the House required the support of the unelected upper house, the House of Peers. Both the cabinet of Japan and the Japanese military were directly responsible not to the elected legislature but to the emperor.[181] Concurrently, the Japanese government also developed a form of Japanese nationalism under which Shinto became the state religion and the emperor was declared a living god.[182] Schools nationwide instilled patriotic values and loyalty to the emperor.[168]

Rise of imperialism and the military[edit]

In December 1871, a Ryukyuan ship was shipwrecked on Taiwan and the crew were massacred. In 1874, using the incident as a pretext, Japan launched a military expedition to Taiwan to assert their claims to the Ryukyu Islands. The expedition featured the first instance of the Japanese military ignoring the orders of the civilian government, as the expedition set sail after being ordered to postpone.[183] Yamagata Aritomo, who was born a samurai in the Chōshū Domain, was a key force behind the modernization and enlargement of the Imperial Japanese Army, especially the introduction of national conscription.[184] The new army was put to use in 1877 to crush the Satsuma Rebellion of discontented samurai in southern Japan led by the former Meiji leader Saigo Takamori.[185]

The Japanese military played a key role in Japan's expansion abroad. The government believed that Japan had to acquire its own colonies to compete with the Western colonial powers. After consolidating its control over Hokkaido (through the Hokkaidō Development Commission) and annexing the Ryukyu Kingdom (the "Ryūkyū Disposition"), it next turned its attention to China and Korea.[186] In 1894, Japanese and Chinese troops clashed in Korea, where they were both stationed to suppress the Donghak Rebellion. During the ensuing First Sino-Japanese War, Japan's highly motivated and well-led forces defeated the more numerous and better-equipped military of Qing China.[187] The island of Taiwan was thus ceded to Japan in 1895,[188] and Japan's government gained enough international prestige to allow Foreign Minister Mutsu Munemitsu to renegotiate the "unequal treaties".[189] In 1902 Japan signed an important military alliance with the British.[190]

Japan next clashed with Russia, which was expanding its power in Asia. The Battle of Yalu River was the first time in decades that an Asian power defeated a western power.[191] The Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 ended with the dramatic Battle of Tsushima, which was another victory for Japan's new navy. Japan thus laid claim to Korea as a protectorate in 1905, followed by full annexation in 1910.[192] The defeat of Russia in the war had set in motion a change in the global world order with the emergence of Japan as not only a regional power, but rather, the main Asian power.[193]

Economic modernization and labor unrest[edit]

During the Meiji period, Japan underwent a rapid transition towards an industrial economy.[194] Both the Japanese government and private entrepreneurs adopted Western technology and knowledge to create factories capable of producing a wide range of goods.[195]

By the end of the period, the majority of Japan's exports were manufactured goods.[194] Some of Japan's most successful new businesses and industries constituted huge family-owned conglomerates called zaibatsu, such as Mitsubishi and Sumitomo.[196] The phenomenal industrial growth sparked rapid urbanization. The proportion of the population working in agriculture shrank from 75 percent in 1872 to 50 percent by 1920.[197] In 1927 the Tokyo Metro Ginza Line opened and it is the oldest subway line in Asia.[198]

Japan enjoyed solid economic growth at this time and most people lived longer and healthier lives. The population rose from 34 million in 1872 to 52 million in 1915.[199] Poor working conditions in factories led to growing labor unrest,[200] and many workers and intellectuals came to embrace socialist ideas.[201] The Meiji government responded with harsh suppression of dissent. Radical socialists plotted to assassinate the emperor in the High Treason Incident of 1910, after which the Tokkō secret police force was established to root out left-wing agitators.[202] The government also introduced social legislation in 1911 setting maximum work hours and a minimum age for employment.[203]

Taishō period (1912–1926)[edit]

During the short reign of Emperor Taishō, Japan developed stronger democratic institutions and grew in international power. The Taishō political crisis opened the period with mass protests and riots organized by Japanese political parties, which succeeded in forcing Katsura Tarō to resign as prime minister.[204] This and the rice riots of 1918 increased the power of Japan's political parties over the ruling oligarchy.[205] The Seiyūkai and Minseitō parties came to dominate politics by the end of the so-called "Taishō democracy" era.[206] The franchise for the House of Representatives had been gradually expanded since 1890,[207] and in 1925 universal male suffrage was introduced. However, in the same year the far-reaching Peace Preservation Law also passed, prescribing harsh penalties for political dissidents.[208]

Japan's participation in World War I on the side of the Allies sparked unprecedented economic growth and earned Japan new colonies in the South Pacific seized from Germany.[209] After the war, Japan signed the Treaty of Versailles and enjoyed good international relations through its membership in the League of Nations and participation in international disarmament conferences.[210] The Great Kantō earthquake in September 1923 left over 100,000 dead, and combined with the resultant fires destroyed the homes of more than three million.[211] In the aftermath of the earthquake, the Kantō Massacre occurred, in which the Japanese military, police, and gangs of vigilantes murdered thousands of Korean people after rumors emerged that Koreans had been poisoning wells. The rumors were later described as false by numerous Japanese sources.[212]

The growth of popular prose fiction, which began during the Meiji period, continued into the Taishō period as literacy rates rose and book prices dropped.[213] Notable literary figures of the era included short story writer Ryūnosuke Akutagawa[214] and the novelist Haruo Satō. Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, described as "perhaps the most versatile literary figure of his day" by the historian Conrad Totman, produced many works during the Taishō period influenced by European literature, though his 1929 novel Some Prefer Nettles reflects deep appreciation for the virtues of traditional Japanese culture.[215] At the end of the Taishō period, Tarō Hirai, known by his penname Edogawa Ranpo, began writing popular mystery and crime stories.[214]

Shōwa period (1926–1989)[edit]

Emperor Hirohito's sixty-three-year reign from 1926 to 1989 is the longest in recorded Japanese history.[216] The first twenty years were characterized by the rise of extreme nationalism and a series of expansionist wars. After suffering defeat in World War II, Japan was occupied by foreign powers for the first time in its history, and then re-emerged as a major world economic power.[217]

Manchurian Incident and the Second Sino-Japanese War[edit]

Left-wing groups had been subject to violent suppression by the end of the Taishō period,[218] and radical right-wing groups, inspired by fascism and Japanese nationalism, rapidly grew in popularity.[219] The extreme right became influential throughout the Japanese government and society, notably within the Kwantung Army, a Japanese army stationed in China along the Japanese-owned South Manchuria Railroad.[220] During the Manchurian Incident of 1931, radical army officers bombed a small portion of the South Manchuria Railroad and, falsely attributing the attack to the Chinese, invaded Manchuria. The Kwantung Army conquered Manchuria and set up the puppet government of Manchukuo there without permission from the Japanese government. International criticism of Japan following the invasion led to Japan withdrawing from the League of Nations.[221]

Prime Minister Tsuyoshi Inukai of the Seiyūkai Party attempted to restrain the Kwantung Army and was assassinated in 1932 by right-wing extremists. Because of growing opposition within the Japanese military and the extreme right to party politicians, who they saw as corrupt and self-serving, Inukai was the last party politician to govern Japan in the pre-World War II era.[221] In February 1936 young radical officers of the Imperial Japanese Army attempted a coup d'état. They assassinated many moderate politicians before the coup was suppressed.[222] In its wake the Japanese military consolidated its control over the political system and most political parties were abolished when the Imperial Rule Assistance Association was founded in 1940.[223]

Japan's expansionist vision grew increasingly bold. Many of Japan's political elite aspired to have Japan acquire new territory for resource extraction and settlement of surplus population.[224] These ambitions led to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937. After their victory in the Chinese capital, the Japanese military committed the infamous Nanjing Massacre. The Japanese military failed to defeat the Chinese government led by Chiang Kai-shek and the war descended into a bloody stalemate that lasted until 1945.[225] Japan's stated war aim was to establish the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, a vast pan-Asian union under Japanese domination.[226] Hirohito's role in Japan's foreign wars remains a subject of controversy, with various historians portraying him as either a powerless figurehead or an enabler and supporter of Japanese militarism.[227]

The United States opposed Japan's invasion of China and responded with increasingly stringent economic sanctions intended to deprive Japan of the resources to continue its war in China.[228] Japan reacted by forging an alliance with Germany and Italy in 1940, known as the Tripartite Pact, which worsened its relations with the US. In July 1941, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands froze all Japanese assets when Japan completed its invasion of French Indochina by occupying the southern half of the country, further increasing tension in the Pacific.[229]

World War II[edit]

Acquisitions (1895–1930)

Acquisitions (1930–1942)

In late 1941, Japanese government, led by Prime Minister and General Hideki Tojo, decided to break the US-led embargo through force of arms.[230] On 7 December 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy launched a surprise attack on the American fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. This brought the US into World War II on the side of the Allies. Japan then successfully invaded the Asian colonies of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands, including the Philippines, Malaya, Hong Kong, Singapore, Burma, and the Dutch East Indies.[231] In the early stages of the war, Japan scored victory after victory.

The tide began to turn against Japan following the Battle of Midway in June 1942 and the subsequent Battle of Guadalcanal, in which Allied troops wrested the Solomon Islands from Japanese control.[232] During this period the Japanese military was responsible for such war crimes as mistreatment of prisoners of war, massacres of civilians, and the use of chemical and biological weapons.[233] The Japanese military earned a reputation for fanaticism, often employing banzai charges and fighting almost to the last man against overwhelming odds.[234] In 1944 the Imperial Japanese Navy began deploying squadrons of kamikaze pilots who crashed their planes into enemy ships.[235]

Life in Japan became increasingly difficult for civilians due to stringent rationing of food, electrical outages, and a brutal crackdown on dissent.[236] In 1944 the US Army captured the island of Saipan, which allowed the United States to begin widespread bombing raids on the Japanese mainland.[237] These destroyed over half of the total area of Japan's major cities.[238] The Battle of Okinawa, fought between April and June 1945, was the largest naval operation of the war and left 115,000 soldiers and 150,000 Okinawan civilians dead, suggesting that the planned invasion of mainland Japan would be even bloodier.[239] The Japanese superbattleship Yamato was sunk en route to aid in the Battle of Okinawa.[240]

However, on 6 August 1945, the US dropped an atomic bomb over Hiroshima, killing over 70,000 people. This was the first nuclear attack in history. On 9 August the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and invaded Manchukuo and other territories, and Nagasaki was struck by a second atomic bomb, killing around 40,000 people.[241] The surrender of Japan was communicated to the Allies on 14 August and broadcast by Emperor Hirohito on national radio the following day.[242]

Occupation of Japan[edit]

Japan experienced dramatic political and social transformation under the Allied occupation in 1945–1952. US General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of Allied Powers, served as Japan's de facto leader and played a central role in implementing reforms, many inspired by the New Deal of the 1930s.[243]

The occupation sought to decentralize power in Japan by breaking up the zaibatsu, transferring ownership of agricultural land from landlords to tenant farmers,[244] and promoting labor unionism.[245] Other major goals were the demilitarization and democratization of Japan's government and society. Japan's military was disarmed,[246] its colonies were granted independence,[247] the Peace Preservation Law and Special Higher Police were abolished,[248] and the International Military Tribunal of the Far East tried war criminals.[249] The cabinet became responsible not to the Emperor but to the elected National Diet.[250] The Emperor was permitted to remain on the throne, but was ordered to renounce his claims to divinity, which had been a pillar of the State Shinto system.[251] Japan's new constitution came into effect in 1947 and guaranteed civil liberties, labor rights, and women's suffrage,[252] and through Article 9, Japan renounced its right to go to war with another nation.[253]

The San Francisco Peace Treaty of 1951 officially normalized relations between Japan and the United States. The occupation ended in 1952, although the US continued to administer a number of the Ryukyu Islands.[254] In 1968, the Ogasawara Islands were returned from US occupation to Japanese sovereignty. Japanese citizens were allowed to return. Okinawa was the last to be returned in 1972.[255] The US continues to operate military bases throughout the Ryukyu Islands, mostly on Okinawa, as part of the US-Japan Security Treaty.[256]

Postwar growth and prosperity[edit]

Shigeru Yoshida served as prime minister in 1946–1947 and 1948–1954, and played a key role in guiding Japan through the occupation.[257] His policies, known as the Yoshida Doctrine, proposed that Japan should forge a tight relationship with the United States and focus on developing the economy rather than pursuing a proactive foreign policy.[258] Yoshida was one of the longest serving prime ministers in Japanese history.[259] Yoshida's Liberal Party merged in 1955 into the new Liberal Democratic Party (LDP),[260] which went on to dominate Japanese politics for the remainder of the Shōwa period.[261]

Although the Japanese economy was in bad shape in the immediate postwar years, an austerity program implemented in 1949 by finance expert Joseph Dodge ended inflation.[262] The Korean War (1950–1953) was a major boon to Japanese business.[263] In 1949 the Yoshida cabinet created the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) with a mission to promote economic growth through close cooperation between the government and big business. MITI sought successfully to promote manufacturing and heavy industry,[264] and encourage exports.[265] The factors behind Japan's postwar economic growth included technology and quality control techniques imported from the West, close economic and defense cooperation with the United States, non-tariff barriers to imports, restrictions on labor unionization, long work hours, and a generally favorable global economic environment.[266] Japanese corporations successfully retained a loyal and experienced workforce through the system of lifetime employment, which assured their employees a safe job.[267]

By 1955, the Japanese economy had grown beyond prewar levels,[268] and by 1968 it had become the second largest capitalist economy in the world.[269] The GNP expanded at an annual rate of nearly 10% from 1956 until the 1973 oil crisis slowed growth to a still-rapid average annual rate of just over 4% until 1991.[270] Life expectancy rose and Japan's population increased to 123 million by 1990.[271] Ordinary Japanese people became wealthy enough to purchase a wide array of consumer goods. During this period, Japan became the world's largest manufacturer of automobiles and a leading producer of electronics.[272] Japan signed the Plaza Accord in 1985 to depreciate the US dollar against the yen and other currencies. By the end of 1987, the Nikkei stock market index had doubled and the Tokyo Stock Exchange became the largest in the world. During the ensuing economic bubble, stock and real-estate loans grew rapidly.[273]

Japan became a member of the United Nations in 1956 and further cemented its international standing in 1964, when it hosted the Olympic Games in Tokyo.[274] Japan was a close ally of the United States during the Cold War, though this alliance did not have unanimous support from the Japanese people. As requested by the United States, Japan reconstituted its army in 1954 under the name Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF), though some Japanese insisted that the very existence of the JSDF was a violation of Article 9 of Japan's constitution.[275] In 1960, the massive Anpo protests saw hundreds of thousands of citizens take to the streets in opposition to the US-Japan Security Treaty.[276] Japan successfully normalized relations with the Soviet Union in 1956, despite an ongoing dispute over the ownership of the Kuril Islands,[277] and with South Korea in 1965, despite an ongoing dispute over the ownership of the islands of Liancourt Rocks.[278] In accordance with US policy, Japan recognized the Republic of China on Taiwan as the legitimate government of China after World War II, though Japan switched its recognition to the People's Republic of China in 1972.[279]

Among cultural developments, the immediate post-occupation period became a golden age for Japanese cinema.[280] The reasons for this include the abolition of government censorship, low film production costs, expanded access to new film techniques and technologies, and huge domestic audiences at a time when other forms of recreation were relatively scarce.[281] On 1 October 1964, Japan's first high-speed rail line was built called the Tokaido Shinkansen.[282] It is also the oldest high-speed rail system in the world.[282]

Heisei period (1989–2019)[edit]

Emperor Akihito's reign began upon the death of his father, Emperor Hirohito. The economic bubble popped in 1989, and stock and land prices plunged as Japan entered a deflationary spiral. Banks found themselves saddled with insurmountable debts that hindered economic recovery.[283] Stagnation worsened as the birthrate declined far below replacement level.[284] The 1990s are often referred to as Japan's Lost Decade.[285] Economic performance was often poor in the following decades, and the stock market never returned to its pre-1989 highs.[286] Japan's system of lifetime employment largely collapsed and unemployment rates rose.[287] The faltering economy and several corruption scandals weakened the LDP's dominant political position. Japan was nevertheless governed by non-LDP prime ministers only in 1993–1996[288] and 2009–2012.[289]

Борьба Японии со своим военным наследием обострила отношения с Китаем и Южной Кореей . С 1950-х годов японские чиновники и императоры принесли более 50 официальных извинений за войну. Однако некоторые политики Китая и Южной Кореи сочли официальные извинения, такие как извинения Императора в 1990 году и Заявление Мураямы 1995 года, неадекватными или неискренними. [290] Националистическая политика усугубила ситуацию, например, отрицание Нанкинской резни и других военных преступлений. [291] ревизионистские учебники истории , что спровоцировало протесты в Восточной Азии . [292] Японские политики часто посещают храм Ясукуни, чтобы почтить память людей, погибших в войнах с 1868 по 1954 год, но среди захороненных есть и осужденные военные преступники. [293]

Население Японии достигло пика в 128 083 960 человек в 2008 году, а по состоянию на декабрь 2020 года оно упало ниже 126 миллионов. [294] В 2011 году Китай обогнал Японию и стал второй крупнейшей экономикой мира по номинальному ВВП. [295] Несмотря на экономические трудности Японии, в этот период японская популярная культура , включая видеоигры , аниме и мангу , распространилась по всему миру, особенно среди молодежи. [296] В марте 2011 года Токийское небесное дерево стало самой высокой башней в мире высотой 634 метра (2080 футов), потеснив Кантонскую башню . [297] [298] В настоящее время это третье по высоте сооружение в мире.

11 марта 2011 года одно из крупнейших землетрясений, зарегистрированных в Японии на северо-востоке произошло . Возникшее в результате цунами повредило ядерные объекты в Фукусиме , где произошла ядерная авария и серьезная утечка радиации. [299]

Рейва (2019 – настоящее Период время )

императора Нарухито Правление началось 1 мая 2019 года после отречения его отца , императора Акихито. [300]

В 2020 году Токио должен был принять летние Олимпийские игры во второй раз с 1964 года. Япония стала второй азиатской страной (после Южной Кореи), которая дважды принимала Олимпийские игры. Однако из-за глобальной вспышки и экономических последствий пандемии COVID-19 летние Олимпийские игры были перенесены на 2021 год; они проходили с 23 июля по 8 августа 2021 года. [301] Япония заняла третье место с 27 золотыми медалями. [302]

Когда в 2022 году началось российское вторжение на Украину , Япония осудила и ввела санкции против России за ее действия. [303] Президент Украины Владимир Зеленский назвал Японию «первой азиатской страной, которая начала оказывать давление на Россию». [303] Япония заморозила активы центрального банка России и других крупнейших российских банков, а также активы, принадлежащие 500 российским гражданам и организациям. [303] Япония запретила новые инвестиции и экспорт высоких технологий в страну. Торговый статус России как нации-фаворита был аннулирован. [303] Быстрые действия Японии показывают, что она становится ведущей державой в мире. [303] Война на Украине и угрозы со стороны Китая и Северной Кореи привели к изменению политики безопасности Японии, что привело к увеличению расходов на оборону, что подрывает ее прежнюю пацифистскую позицию. [303]

8 июля 2022 года бывший премьер-министр Синдзо Абэ был убит в городе Нара бывшим военнослужащим Морских сил самообороны Японии Тэцуей Ямагами во время предвыборной кампании за два дня до выборов в Палату советников 2022 года . [304] Это шокировало общественность, поскольку смертельные случаи с применением огнестрельного оружия в Японии очень редки. В период с 2017 по 2020 год произошло всего 10 смертей от огнестрельного оружия и 1 случай смерти от огнестрельного оружия в 2021 году. [305]

После визита Нэнси Пелоси на Тайвань в 2022 году Китай 4 августа 2022 года нанес «точные ракетные удары» по океану вокруг береговой линии Тайваня. [306] Эти военные учения усилили напряженность в регионе. [306] Японии Министерство обороны сообщило, что это первый случай, когда баллистические ракеты, запущенные Китаем, приземлились в исключительной экономической зоне Японии, и выразило дипломатический протест Пекину. [307] Пять китайских ракет упали в ИЭЗ Японии недалеко от Хатерума , недалеко от Тайваня. [306] Министр обороны Японии Нобуо Киши заявил, что эти ракеты представляют собой «серьезную угрозу национальной безопасности Японии и безопасности японского народа». [306]

16 декабря 2022 года Япония объявила о серьезном изменении в своей военной политике, приобретя возможности для нанесения контрударов и увеличив оборонный бюджет до 2% ВВП (43 триллиона йен (315 миллиардов долларов США) к 2027 году. [308] [309] Стимулом этого увеличения являются опасения по поводу региональной безопасности в отношении Китая, Северной Кореи и России. [308] Это позволит Японии переместиться с девятого места в мире по расходам на оборону на третье место, уступая лишь Соединенным Штатам и Китаю. [310]

Социальные условия [ править ]

Социальное расслоение в Японии стало ярко выраженным в период Яёи. Расширение торговли и сельского хозяйства увеличивало благосостояние общества, которое все больше монополизировалось социальными элитами. [311] К 600 году нашей эры сложилась классовая структура, включавшая придворных аристократов, семьи местных магнатов, простолюдинов и рабов. [312] Более 90% составляли простолюдины, в том числе фермеры, торговцы и ремесленники. [313] В конце периода Хэйан правящая элита состояла из трех классов. Традиционная аристократия делила власть с буддистскими монахами и самураями. [313] хотя последний становился все более доминирующим в периоды Камакура и Муромати. [314] В эти периоды наблюдался подъем класса купцов, который диверсифицировался в большее количество специализированных занятий. [315]

Женщины изначально придерживались социального и политического равенства с мужчинами. [312] а археологические данные свидетельствуют о доисторическом предпочтении женщин-правителей в западной Японии. Женщины-императоры появлялись в письменной истории до тех пор, пока в 1889 году Конституция Мэйдзи не провозгласила строгое вознесение на престол только мужчин. [316] Китайский патриархат в конфуцианском стиле был впервые систематизирован в VII–VIII веках с помощью системы рицурё . [317] который ввел регистр семей по отцовской линии , в котором главой семьи является мужчина. [318] До этого женщины играли важную роль в правительстве, которая впоследствии постепенно уменьшалась, хотя даже в конце периода Хэйан женщины обладали значительным влиянием при дворе. [316] Брачные обычаи и многие законы, регулирующие частную собственность, оставались гендерно нейтральными. [319]

По причинам, которые неясны историкам, положение женщин, начиная с четырнадцатого века, резко ухудшилось. [320] Женщины всех социальных классов потеряли право владеть и наследовать собственность и все чаще считались неполноценными по сравнению с мужчинами. [321] Землеустроительная работа Хидэёси 1590-х годов еще больше закрепила статус мужчин как доминирующих землевладельцев. [322] Во время американской оккупации после Второй мировой войны женщины получили юридическое равенство с мужчинами. [323] но столкнулся с широко распространенной дискриминацией на рабочем месте. Движение за права женщин привело к принятию закона о равном трудоустройстве в 1986 году, но к 1990-м годам женщины занимали только 10% руководящих должностей. [324]

В землеустроительном исследовании Хидэёси 1590-х годов все, кто обрабатывал землю, были признаны простолюдинами, что предоставило эффективную свободу большинству японских рабов . [325]

В период Эдо , сёгунат Токугава ссылаясь на неоконфуцианскую теорию , правил, разделяя людей на четыре основные категории. существовали Си-но-ко-сё ( 士農工商 , четыре занятия ) «самураев, крестьян ( хякусё ), ремесленников и торговцев» ( тёнин ) Ученые старшего возраста считали, что при даймё , причем 80% крестьян находились под властью 5% самураев . класс, за которым следовали ремесленники и купцы. [330] Однако различные исследования, начиная примерно с 1995 года, показали, что классы крестьян, ремесленников и торговцев при самураях равны, а старая иерархическая схема была удалена из японских учебников по истории. Другими словами, крестьяне, ремесленники и купцы — это не социальная иерархия, а социальная классификация. [326] [327] [328] Брак между представителями определенных классов вообще был запрещен. В частности, браки между даймё и придворными дворянами были запрещены сёгунатом Токугава, поскольку это могло привести к политическому маневрированию. По этой же причине браки между даймё и высокопоставленными хатамото из сословия самураев требовали одобрения сёгуната Токугава. Представителю сословия самураев также запрещалось жениться на крестьянке, ремесленнике или торговце, но делалось это через лазейку, при которой человека из низшего сословия принимали в сословие самураев, а затем женили. Поскольку для бедного человека из класса самураев было экономическое преимущество жениться на богатой женщине из купеческого или крестьянского класса, они усыновляли женщину из купеческого или крестьянского класса в класс самураев в качестве приемной дочери, а затем женились на ней. [331] [332] Социальное расслоение мало влияло на экономические условия: многие самураи жили в нищете. [333] и богатство купеческого класса росло на протяжении всего периода по мере развития коммерческой экономики и роста урбанизации. [334] Структура социальной власти эпохи Эдо оказалась несостоятельной и после Реставрации Мэйдзи уступила место той, в которой коммерческая власть играла все более важную политическую роль. [335]

Хотя все социальные классы были юридически отменены в начале периода Мэйдзи, [167] неравенство доходов значительно возросло. [336] Новое экономическое классовое разделение образовалось между владельцами капиталистического бизнеса, которые сформировали новый средний класс, мелкими лавочниками старого среднего класса, рабочим классом на фабриках, сельскими землевладельцами и фермерами-арендаторами. [337] Огромное неравенство в доходах между классами исчезло во время и после Второй мировой войны, в конечном итоге снизившись до уровня, который был одним из самых низких в промышленно развитом мире. [336] Некоторые послевоенные опросы показали, что до 90% японцев относят себя к среднему классу. [338]

Популяции рабочих профессий, считающихся нечистыми , таких как кожевники и те, кто работал с мертвыми, в 15 и 16 веках превратились в наследственные изгоев . сообщества [339] Эти люди, позже названные буракуминами , выпали из классовой структуры периода Эдо и пострадали от дискриминации, которая продолжалась и после упразднения классовой системы. [339] Хотя активизм улучшил социальные условия выходцев из буракумин , дискриминация в сфере труда и образования сохранилась и в 21 веке. [339]

См. также [ править ]

- Экономическая история Японии

- Период Хигасияма

- Историография Японии

- Библиография японской истории

- Бюллетень Национального музея японской истории , на японском языке.

- Японский журнал религиоведения

- Журнал японоведов

- Monumenta Nipponica , японоведение, на английском языке

- Японский журнал социальных наук

- История Восточной Азии

- История японского искусства

- История американцев японского происхождения

- История международных отношений Японии

- История Токио

- Список императоров Японии

- Список премьер-министров Японии

- Хронология японской истории

Цитаты [ править ]

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Наказава, Юичи (1 декабря 2017 г.). «К истории плейстоценового населения Японского архипелага» . Современная антропология . 58 (С17): S539–S552. дои : 10.1086/694447 . hdl : 2115/72078 . ISSN 0011-3204 . S2CID 149000410 .

- ^ Шинья Сёда (2007). «Комментарий к спору о датировке периода Яёи» . Бюллетень Общества восточноазиатской археологии . 1 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 августа 2019 года . Проверено 16 февраля 2020 г. .

- ^ « Женщина Дзёмон помогает разгадать генетическую тайну Японии» . НХК Мир . 10 июля 2019 г. Архивировано из оригинала 26 апреля 2020 г.

- ^ Оно, Акира (2014). «Современные гоминиды на Японских островах и раннее использование обсидиана», стр. 157–159 в Санце, Нурия (ред.). Объекты происхождения человека и Конвенция всемирного наследия в Азии . Архивировано 17 мая 2021 года в Wayback Machine . Париж: ЮНЕСКО.