Second Sino-Japanese War

| Second Sino-Japanese War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Interwar period and the Pacific theatre of World War II | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Total casualties: 15,000,000[24]–22,000,000[15] | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Second Sino-Japanese War | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 抗日戰爭 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 抗日战争 | ||

| |||

| Alternative name | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 抗戰 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 抗战 | ||

| |||

| Alternative name(2) | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 八年抗戰 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 八年抗战 | ||

| |||

| Alternative name(3) | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 十四年抗戰 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 十四年抗战 | ||

| |||

| Alternative name(4) | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 第二次中日戰爭 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 第二次中日战争 | ||

| |||

| Alternative name(5) | |||

| Traditional Chinese | (日本)侵華戰爭 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | (日本)侵华战争 | ||

| |||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji |

| ||

| Hiragana |

| ||

| Katakana |

| ||

| |||

The Second Sino-Japanese War was the war fought between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan from 1937 to 1945 as part of World War II. It is often regarded as the beginning of World War II in Asia. It was the largest Asian war in the 20th century[25] and has been described as "the Asian Holocaust", in reference to the scale of Japanese war crimes against Chinese civilians.[26][27][28] It is known in Japan as the Second China–Japan War, and in China as the Chinese War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression.

On 18 September 1931, the Japanese staged a false flag event known as the Mukden Incident, a pretext they fabricated to justify their invasion of Manchuria. This is sometimes marked as the beginning of the war.[29][30] From 1931 to 1937, China and Japan engaged in skirmishes in mainland China. Japan achieved major victories, capturing Beijing and Shanghai by 1937. Despite having fought each other in the Chinese Civil War since 1927, the Communists and Nationalists formed the Second United Front in late 1936 to resist the Japanese invasion together.

Tensions escalated after what would become the first battle of the war - the Marco Polo Bridge incident on 7 July 1937, in which the Japanese and Chinese opened fire upon each other after a Japanese soldier went missing. This prompted a full-scale Japanese invasion of the rest of China. This incident is widely regarded as the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and the Pacific theater of World War II.[31]

The Japanese captured the Chinese capital of Nanjing in 1937, which led to the Nanjing Massacre, also known as the Rape of Nanjing. After failing to stop the Japanese in the Battle of Wuhan, the Chinese central government relocated to Chongqing in the Chinese interior. Following the Sino-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, material support bolstered the Republic of China Army and Air Force.

By 1939, after Chinese victories in Changsha and Guangxi, and with Japan's lines of communications stretched deep into the Chinese interior, the war reached a stalemate. The Japanese were unable to defeat Chinese Communist Party (CCP) forces in Shaanxi, who waged a campaign of sabotage and guerrilla warfare. In November 1939, Chinese nationalist forces launched a large scale winter offensive, and in August 1940, CCP forces launched an offensive in central China.

In December 1941, Japan launched its surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and declared war on the United States. The US increased aid to China: the Lend-Lease act gave China a total of $1.6 billion (equivalent to $20 billion in 2023).[32] With Burma cut off, the US Army Air Forces airlifted material over the Himalayas. In 1944, Japan launched Operation Ichi-Go, the invasion of Henan and Changsha. In 1945, the Chinese Expeditionary Force resumed its advance in Burma and completed the Ledo Road linking India to China. China launched large counteroffensives in South China and repulsed a failed Japanese invasion of West Hunan and recaptured Japanese occupied regions of Guangxi.

Japan formally surrendered on 2 September 1945, following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Soviet declaration of war and subsequent invasions of Manchukuo and Korea. The war resulted in the deaths of around 20 million people, mostly civilians. China was recognized as one of the Big Four Allies, regained all territories lost, and became one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council.[33][34] The Chinese Civil War resumed in 1946, ending with a communist victory, which established the People's Republic of China.

Names[edit]

In China, the war is most commonly known as the "War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression" (simplified Chinese: 抗日战争; traditional Chinese: 抗日戰爭), and shortened to "Resistance against Japanese Aggression" (Chinese: 抗日) or the "War of Resistance" (simplified Chinese: 抗战; traditional Chinese: 抗戰). It was also called the "Eight Years' War of Resistance" (simplified Chinese: 八年抗战; traditional Chinese: 八年抗戰), but in 2017 the Chinese Ministry of Education issued a directive stating that textbooks were to refer to the war as the "Fourteen Years' War of Resistance" (simplified Chinese: 十四年抗战; traditional Chinese: 十四年抗戰), reflecting a focus on the broader conflict with Japan going back to the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria.[35] According to historian Rana Mitter, historians in China are unhappy with the blanket revision, and (despite sustained tensions) the Republic of China did not consider itself to be in an ongoing war with Japan over these six years.[36][need quotation to verify] It is also referred to as part of the "Global Anti-Fascist War".

In Japan, nowadays, the name "Japan–China War" (Japanese: 日中戦争, romanized: Nitchū Sensō) is most commonly used because of its perceived objectivity. When the invasion of China proper began in earnest in July 1937 near Beijing, the government of Japan used "The North China Incident" (Japanese: 北支事變/華北事變, romanized: Hokushi Jihen/Kahoku Jihen), and with the outbreak of the Battle of Shanghai the following month, it was changed to "The China Incident" (Japanese: 支那事變, romanized: Shina Jihen).

The word "incident" (Japanese: 事變, romanized: jihen) was used by Japan, as neither country had made a formal declaration of war. From the Japanese perspective, localizing these conflicts was beneficial in preventing intervention from other nations, particularly the United Kingdom and the United States, which were its primary source of petroleum and steel respectively. A formal expression of these conflicts would potentially lead to American embargo in accordance with the Neutrality Acts of the 1930s.[37] In addition, due to China's fractured political status, Japan often claimed that China was no longer a recognizable political entity on which war could be declared.[38]

Other names[edit]

In Japanese propaganda, the invasion of China became a crusade (Japanese: 聖戦, romanized: seisen), the first step of the "eight corners of the world under one roof" slogan (Japanese: 八紘一宇, romanized: Hakkō ichiu). In 1940, Japanese Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe launched the Taisei Yokusankai. When both sides formally declared war in December 1941, the name was replaced by "Greater East Asia War" (Japanese: 大東亞戰爭, romanized: Daitōa Sensō).

Although the Japanese government still uses the term "China Incident" in formal documents,[39] the word Shina is considered derogatory by China and therefore the media in Japan often paraphrase with other expressions like "The Japan–China Incident" (Japanese: 日華事變/日支事變, romanized: Nikka Jiken/Nisshi Jiken), which were used by media as early as the 1930s.

The name "Second Sino-Japanese War" is not commonly used in Japan as the China it fought a war against in 1894 to 1895 was led by the Qing dynasty, and thus is called the Qing-Japanese War (Japanese: 日清戦争, romanized: Nisshin–Sensō), rather than the First Sino-Japanese War.

Background[edit]

Previous war[edit]

The origins of the Second Sino-Japanese War can be traced back to the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, in which China, then under the rule of the Qing dynasty, was defeated by Japan and forced to cede Taiwan and recognize the full and complete independence of Korea in the Treaty of Shimonoseki. Japan also annexed the Senkaku Islands, which Japan claims were uninhabited, in early 1895 as a result of its victory at the end of the war. Japan had also attempted to annex the Liaodong Peninsula following the war, though was forced to return it to China following an intervention by France, Germany, and Russia.[40][41][42] The Qing dynasty was on the brink of collapse due to internal revolts and the imposition of the unequal treaties, while Japan had emerged as a great power through its modernization measures.[43] In 1905, Japan successfully defeated the Russian Empire in the Russo-Japanese War, gaining Tailen and southern Sakhalin and establishing a protectorate over Korea.

Warlords in the Republic of China[edit]

In 1911, factions of the Qing Army uprose against the government, staging a revolution that swept across China's southern provinces.[44] The Qing responded by appointing Yuan Shikai, commander of the loyalist Beiyang Army, as temporary prime minister in order to subdue the revolution.[45] Yuan, wanting to remain in power, compromised with the revolutionaries, and agreed to abolish the monarchy and establish a new republican government, under the condition he be appointed president of China. The new Beiyang government of China was proclaimed in March 1912, after which Yuan Shikai began to amass power for himself. In 1913, the parliamentary political leader Song Jiaoren was assassinated; it is generally believed Yuan Shikai ordered the assassination.[46] Yuan Shikai then forced the parliament to pass a bill to strengthen the power of the president and sought to restore the imperial system, becoming the new emperor of China.

However, there was little support for an imperial restoration among the general population, and protests and demonstrations soon broke out across the country. Yuan's attempts at restoring the monarchy triggered the National Protection War, and Yuan Shikai was overthrown after only a few months. In the aftermath of Shikai's death in June 1916, control of China fell into the hands of the Beiyang Army leadership. The Beiyang government was a civilian government in name, but in practice it was a military dictatorship[47] with a different warlord controlling each province of the country. China was reduced to a fractured state. As a result, China's prosperity began to wither and its economy declined. This instability presented an opportunity for nationalistic politicians in Japan to press for territorial expansion.[48]

Twenty-One Demands[edit]

In 1915, Japan issued the Twenty-One Demands to extort further political and commercial privilege from China, which was accepted by the regime of Yuan Shikai.[49] Following World War I, Japan acquired the German Empire's sphere of influence in Shandong province,[50] leading to nationwide anti-Japanese protests and mass demonstrations in China. The country remained fragmented under the Beiyang Government and was unable to resist foreign incursions.[51] For the purpose of unifying China and defeating the regional warlords, the Kuomintang (KMT, alternatively known as the Chinese Nationalist Party) in Guangzhou launched the Northern Expedition from 1926 to 1928 with limited assistance from the Soviet Union.[52]

Jinan incident[edit]

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA) formed by the Kuomintang swept through southern and central China until it was checked in Shandong, where confrontations with the Japanese garrison escalated into armed conflict. The conflicts were collectively known as the Jinan incident of 1928, during which time the Japanese military killed several Chinese officials and fired artillery shells into Jinan. According to the investigation results of the Association of the Families of the Victims of the Jinan massacre, it showed that 6,123 Chinese civilians were killed and 1,701 injured.[53] Relations between the Chinese Nationalist government and Japan severely worsened as a result of the Jinan incident.[54][55]

Reunification of China (1928)[edit]

As the National Revolutionary Army approached Beijing, Zhang Zuolin decided to retreat back to Manchuria, before he was assassinated by the Kwantung Army in 1928.[56] His son, Zhang Xueliang, took over as the leader of the Fengtian clique in Manchuria. Later in the same year, Zhang declared his allegiance to the Nationalist government in Nanjing under Chiang Kai-shek, and consequently, China was nominally reunified under one government.[57]

1929 Sino-Soviet war[edit]

The July–November 1929 conflict over the Chinese Eastern Railroad (CER) further increased the tensions in the Northeast that led to the Mukden Incident and eventually the Second Sino-Japanese War. The Soviet Red Army victory over Xueliang's forces not only reasserted Soviet control over the CER in Manchuria but revealed Chinese military weaknesses that Japanese Kwantung Army officers were quick to note.[58]

The Soviet Red Army performance also stunned the Japanese. Manchuria was central to Japan's East Asia policy. Both the 1921 and 1927 Imperial Eastern Region Conferences reconfirmed Japan's commitment to be the dominant power in the Northeast. The 1929 Red Army victory shook that policy to the core and reopened the Manchurian problem. By 1930, the Kwantung Army realized they faced a Red Army that was only growing stronger. The time to act was drawing near and Japanese plans to conquer the Northeast were accelerated.[59]

Chinese Communist Party[edit]

In 1930, the Central Plains War broke out across China, involving regional commanders who had fought in alliance with the Kuomintang during the Northern Expedition, and the Nanjing government under Chiang. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) previously fought openly against the Nanjing government after the Shanghai massacre of 1927, and they continued to expand during this protracted civil war. The Kuomintang government in Nanjing decided to focus their efforts on suppressing the Chinese Communists through the Encirclement Campaigns, following the policy of "first internal pacification, then external resistance" (Chinese: 攘外必先安內).

Historical development[edit]

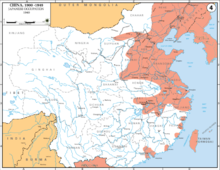

Prelude: invasion of Manchuria and Northern China[edit]

The internecine warfare in China provided excellent opportunities for Japan, which saw Manchuria as a limitless supply of raw materials, a market for its manufactured goods (now excluded from the markets of many Western countries as a result of Depression-era tariffs), and a protective buffer state against the Soviet Union in Siberia. As a result, the Japanese Army was widely prevalent in Manchuria immediately following the Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, where Japan gained significant territory in Manchuria. As a result of their strengthened position, by 1915 Japan had negotiated a significant amount of economic privilege in the region by pressuring Yuan Shikai, the president of the Republic of China at the time. With a widened range of economic privileges in Manchuria, Japan began focusing on developing and protecting matters of economic interests. This included railroads, businesses, natural resources, and a general control of the territory. With its influence growing, the Japanese Army began to justify its presence by stating that it was simply protecting its own economic interests. However militarists in the Japanese Army began pushing for an expansion of influence, leading to the Japanese Army assassinating the warlord of Manchuria, Zhang Zuolin. This was done with hopes that it would start a crisis that would allow Japan to expand their power and influence in the region. When this was not as successful as they desired, [citation needed] Japan then decided to invade Manchuria outright after the Mukden Incident in September 1931. Japanese soldiers set off a bomb on the Southern Manchurian Railroad in order to provoke an opportunity to act in "self defense" and invade outright. Japan charged that its rights in Manchuria, which had been established as a result of its victory in 1905 at the end of the Russo-Japanese War, had been systematically violated and there were "more than 120 cases of infringement of rights and interests, interference with business, boycott of Japanese goods, unreasonable taxation, detention of individuals, confiscation of properties, eviction, demand for cessation of business, assault and battery, and the oppression of Korean residents".[60]

After five months of fighting, Japan established the puppet state of Manchukuo in 1932, and installed the last Emperor of China, Puyi, as its puppet ruler. Militarily too weak to challenge Japan directly, China appealed to the League of Nations for help. The League's investigation led to the publication of the Lytton Report, condemning Japan for its incursion into Manchuria, causing Japan to withdraw from the League of Nations. No country took action against Japan beyond tepid censure. From 1931 until summer 1937, the Nationalist Army under Chiang Kai-shek did little to oppose Japanese encroachment into China.[61]: 69

Incessant fighting followed the Mukden Incident. In 1932, Chinese and Japanese troops fought the January 28 Incident battle. This resulted in the demilitarization of Shanghai, which forbade the Chinese to deploy troops in their own city. In Manchukuo there was an ongoing campaign to defeat the Anti-Japanese Volunteer Armies that arose from widespread outrage over the policy of non-resistance to Japan.

In 1933, the Japanese attacked the Great Wall region. The Tanggu Truce established in its aftermath, gave Japan control of Rehe province as well as a demilitarized zone between the Great Wall and Beijing-Tianjin region. Japan aimed to create another buffer zone between Manchukuo and the Chinese Nationalist government in Nanjing.

Japan increasingly exploited China's internal conflicts to reduce the strength of its fractious opponents. Even years after the Northern Expedition, the political power of the Nationalist government was limited to just the area of the Yangtze River Delta. Other sections of China were essentially in the hands of local Chinese warlords. Japan sought various Chinese collaborators and helped them establish governments friendly to Japan. This policy was called the Specialization of North China (Chinese: 華北特殊化; pinyin: huáběitèshūhùa), more commonly known as the North China Autonomous Movement. The northern provinces affected by this policy were Chahar, Suiyuan, Hebei, Shanxi, and Shandong.

This Japanese policy was most effective in the area of what is now Inner Mongolia and Hebei. In 1935, under Japanese pressure, China signed the He–Umezu Agreement, which forbade the KMT to conduct party operations in Hebei. In the same year, the Chin–Doihara Agreement was signed expelling the KMT from Chahar. Thus, by the end of 1935 the Chinese government had essentially abandoned northern China. In its place, the Japanese-backed East Hebei Autonomous Council and the Hebei–Chahar Political Council were established. There in the empty space of Chahar the Mongol Military Government was formed on 12 May 1936. Japan provided all the necessary military and economic aid. Afterwards Chinese volunteer forces continued to resist Japanese aggression in Manchuria, and Chahar and Suiyuan.

Some Chinese historians believe the 18 September 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria marks the start of the War of Resistance.[62] Although not the conventional Western view, British historian Rana Mitter describes this Chinese trend of historical analysis as "perfectly reasonable".[62] In 2017, the Chinese government officially announced that it would adopt this view.[62] Under this interpretation, the 1931–1937 period is viewed as the "partial" war, while 1937–1945 is a period of "total" war.[62] This view of a fourteen-year war has political significance because it provides more recognition for the role of northeast China in the War of Resistance.[62]

1937: Full-scale invasion of China[edit]

On the night of 7 July 1937, Chinese and Japanese troops exchanged fire in the vicinity of the Marco Polo (or Lugou) Bridge, a crucial access-route to Beijing. What began as confused, sporadic skirmishing soon escalated into a full-scale battle in which Beijing and its port city of Tianjin fell to invading Japanese forces (July–August 1937). On 29 July, some 5,000 troops of the 1st and 2nd Corps of the East Hebei Army mutinied in Tongzhou, turning against the Japanese garrison. In addition to Japanese military personnel, some 260 civilians living in Tongzhou were killed during the uprising in scenes reminiscent of the Boxer Protocol in 1901. These were predominantly Japanese, including the police force, and some ethnic Koreans. The Chinese then set fire to and destroyed much of the city. Only around 60 Japanese civilians survived, who provided both journalists and later historians with firsthand witness accounts. As a result of such violence, the Tongzhou mutiny strongly shook public opinion in Japan.[citation needed]

Battle of Beiping-Tianjin[edit]

On 11 July, in accordance with the Goso conference, the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff authorized the deployment of an infantry division from the Chōsen Army, two combined brigades from the Kwantung Army and an air regiment composed of 18 squadrons as reinforcements to Northern China. By 20 July, total Japanese military strength in the Beijing-Tianjin area exceeded 180,000 personnel.

The Japanese gave Sung and his troops "free passage" before moving in to pacify resistance in areas surrounding Beijing (then Beiping) and Tianjin. After 24 days of combat, the Chinese 29th Army was forced to withdraw. The Japanese captured Beijing and the Taku Forts at Tianjin on 29 and 30 July respectively, thus concluding the Beijing-Tianjin campaign. However, the Japanese Army had been given orders not to advance further than the Yongding River. In a sudden volte-face, the Konoe government's foreign minister opened negotiations with Chiang Kai-shek's government in Nanjing and stated: "Japan wants Chinese cooperation, not Chinese land." Nevertheless, negotiations failed to move further. The Ōyama Incident on 9 August escalated the skirmishes and battles into full scale warfare.[63]

The 29th Army's resistance (and poor equipment) inspired the 1937 "Sword March", which—with slightly reworked lyrics—became the National Revolutionary Army's standard marching cadence and popularized the racial epithet guizi to describe the Japanese invaders.[64]

Battle of Shanghai[edit]

The Imperial General Headquarters (GHQ) in Tokyo, content with the gains acquired in northern China following the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, initially showed reluctance to escalate the conflict into a full-scale war. Following the shooting of two Japanese officers who were attempting to enter the Hongqiao military airport on 9 August 1937, the Japanese demanded that all Chinese forces withdraw from Shanghai; the Chinese outright refused to meet this demand. In response, both the Chinese and the Japanese marched reinforcements into the Shanghai area. Chiang concentrated his best troops north of Shanghai in an effort to impress the city's large foreign community and increase China's foreign support.[61]: 71

On 13 August 1937, Kuomintang soldiers attacked Japanese Marine positions in Shanghai, with Japanese army troops and marines in turn crossing into the city with naval gunfire support at Zhabei, leading to the Battle of Shanghai. On 14 August, Chinese forces under the command of Zhang Zhizhong were ordered to capture or destroy the Japanese strongholds in Shanghai, leading to bitter street fighting. In an attack on the Japanese cruiser Izumo, Kuomintang planes accidentally bombed the Shanghai International Settlement, which led to more than 3,000 civilian deaths.[65]

In the three days from 14 August through 16, 1937, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) sent many sorties of the then-advanced long-ranged G3M medium-heavy land-based bombers and assorted carrier-based aircraft with the expectation of destroying the Chinese Air Force. However, the Imperial Japanese Navy encountered unexpected resistance from the defending Chinese Curtiss Hawk II/Hawk III and P-26/281 Peashooter fighter squadrons; suffering heavy (50%) losses from the defending Chinese pilots (14 August was subsequently commemorated by the KMT as China's Air Force Day).[66][67]

The skies of China had become a testing zone for advanced biplane and new-generation monoplane combat-aircraft designs. The introduction of the advanced A5M "Claude" fighters into the Shanghai-Nanjing theater of operations, beginning on 18 September 1937, helped the Japanese achieve a certain level of air superiority.[68][69] However the few experienced Chinese veteran pilots, as well as several Chinese-American volunteer fighter pilots, including Maj. Art Chin, Maj. John Wong Pan-yang, and Capt. Chan Kee-Wong, even in their older and slower biplanes, proved more than able to hold their own against the sleek A5Ms in dogfights, and it also proved to be a battle of attrition against the Chinese Air Force. At the start of the battle, the local strength of the NRA was around five divisions, or about 70,000 troops, while local Japanese forces comprised about 6,300 marines. On 23 August, the Chinese Air Force attacked Japanese troop landings at Wusongkou in northern Shanghai with Hawk III fighter-attack planes and P-26/281 fighter escorts, and the Japanese intercepted most of the attack with A2N and A4N fighters from the aircraft carriers Hosho and Ryujo, shooting down several of the Chinese planes while losing a single A4N in the dogfight with Lt. Huang Xinrui in his P-26/281; the Japanese Army reinforcements succeeded in landing in northern Shanghai.[70] The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) ultimately committed over 300,000 troops, along with numerous naval vessels and aircraft, to capture the city. After more than three months of intense fighting, their casualties far exceeded initial expectations.[71] On 26 October, the IJA captured Dachang, a key strong-point within Shanghai, and on 5 November, additional reinforcements from Japan landed in Hangzhou Bay. Finally, on 9 November, the NRA began a general retreat.

Japan did not immediately occupy the Shanghai International Settlement or the Shanghai French Concession, areas which were outside of China's control due to the treaty port system.[72]: 11–12 Japan moved into these areas after its 1941 declaration of war against the United States and the United Kingdom.[72]: 12

Battle of Nanjing and Massacre[edit]

Building on the hard-won victory in Shanghai, the IJA advanced on and captured the KMT capital city of Nanjing (December 1937) and Northern Shanxi (September–November 1937). Upon the capture of Nanjing, Japanese committed massive war atrocities including mass murder and rape of Chinese civilians after 13 December 1937, which has been referred to as the Nanjing Massacre. Over the next several weeks, Japanese troops perpetrated numerous mass executions and tens of thousands of rapes. The army looted and burned the surrounding towns and the city, destroying more than a third of the buildings.[73]

The number of Chinese killed in the massacre has been subject to much debate, with estimates ranging from 100,000 to more than 300,000.[74] The numbers agreed upon by most scholars are provided by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, which estimate at least 200,000 murders and 20,000 rapes.[75]

The Japanese atrocities in Nanjing, especially following the Chinese defense of Shanghai, increased international goodwill for the Chinese people and the Chinese government.[61]: 72

1938[edit]

By January 1938, most conventional Kuomintang forces had either been defeated or no longer offered major resistance to Japanese advances.[76]: 122 Communist-led rural resistance to the Japanese remained active, however.[76]: 122

At the start of 1938, the leadership in Tokyo still hoped to limit the scope of the conflict to occupy areas around Shanghai, Nanjing and most of northern China. They thought this would preserve strength for an anticipated showdown with the Soviet Union, but by now the Japanese government and GHQ had effectively lost control of the Japanese army in China.

Battles of Xuzhou and Taierzhuang[edit]

With many victories achieved, Japanese field generals escalated the war in Jiangsu in an attempt to wipe out the Chinese forces in the area. The Japanese managed to overcome Chinese resistance around Bengbu and the Teng xian, but were fought to a halt at Linyi.[77]

The Japanese were then decisively defeated at the Battle of Taierzhuang (March–April 1938), where the Chinese used night attacks and close quarters combat to overcome Japanese advantages in firepower. The Chinese also severed Japanese supply lines from the rear, forcing the Japanese to retreat in the first Chinese victory of the war.[78]

The Japanese then attempted to surround and destroy the Chinese armies in the Xuzhou region with an enormous pincer movement. However the majority of the Chinese forces, some 200,000-300,000 troops in 40 divisions, managed to break out of the encirclement and retreat to defend Wuhan, the Japanese's next target.[79]

Battle of Wuhan[edit]

Following Xuzhou, the IJA changed its strategy and deployed almost all of its existing armies in China to attack the city of Wuhan, which had become the political, economic and military center of China, in hopes of destroying the fighting strength of the NRA and forcing the KMT government to negotiate for peace.[80] On 6 June, they captured Kaifeng, the capital of Henan, and threatened to take Zhengzhou, the junction of the Pinghan and Longhai railways.

The Japanese forces, numbering some 400,000 men, were faced by over 1,000,000 NRA troops in the Central Yangtze region. Having learned from their defeats at Shanghai and Nanjing, the Chinese had adapted themselves to fight the Japanese and managed to check their forces on many fronts, slowing and sometimes reversing the Japanese advances, as in the case of Wanjialing.[81]

To overcome Chinese resistance, Japanese forces frequently deployed poison gas and committed atrocities against civilians, such as a "mini-Nanjing Massacre" in the city of Jiujiang upon its capture.[82][83] After four months of intense combat, the Nationalists were forced to abandon Wuhan by October, and its government and armies retreated to Chongqing.[61]: 72 Both sides had suffered tremendous casualties in the battle, with the Chinese losing up to 500,000 soldiers killed or wounded,[84] and the Japanese up to 200,000.[85]

Communist resistance[edit]

After its fall 1938 victory in the Battle of Wuhan, Japan advanced deep into Communist territory and redeployed 50,000 troops to the Shanxi-Chahar-Hebei Border Region.[76]: 122 Elements of the Eighth Route Army soon attacked the advancing Japanese, inflicting between 3,000 and 5,000 casualties and resulting in a Japanese retreat.[76]: 122 As the Japanese military came to understand that the Communists avoided conventional attacks and defense, it altered its tactics.[76]: 122 The Japanese military built more roads to quicken movement between strongpoints and cities, blockaded rivers and roads in an effort to disrupt Communists supply, sought to expand militia from its puppet regime to conserve manpower, and use systematic violence on civilians in the Border Region in an effort to destroy its economy.[76]: 122–124 The Japanese military mandated confiscation of the Eighth Route Army's goods and used this directive as a pretext to confiscate goods, including engaging in grave robbery in the Border Region.[76]: 124

With Japanese casualties and costs mounting, the Imperial General Headquarters attempted to break Chinese resistance by ordering the air branches of their navy and army to launch the war's first massive air raids on civilian targets. Japanese raiders hit the Kuomintang's newly established provisional capital of Chongqing and most other major cities in unoccupied China, leaving many people either dead, injured, or homeless.

1938 Yellow River flood[edit]

The 1938 Yellow River flood (simplified Chinese: 花园口决堤事件; traditional Chinese: 花園口決堤事件; pinyin: Huāyuánkǒu Juédī Shìjiàn; lit. 'Huayuankou Dam Burst Incident') was a man-made flood from June 1938 to January 1947 created by the Chinese National Army's intentional destruction of dikes (levees) on the Yellow River in Huayuankou, Henan Province. The first wave of floods hit Zhongmu County on 13 June 1938.

The flood acted as a scorched-earth defensive line in the Second Sino-Japanese War.[86][87][88] There were three long-term strategic intents. Firstly, the flood in Henan safeguarded the Shaanxi section of the Longhai railway, the major northwest traffic where the Soviet Union sent their military supplies to the Chinese National Army from August 1937 to March 1941.[89][90] Secondly, the inundated land and railway made it difficult for the Japanese Army to mobilize into Shaanxi, thereby preventing them from entering the Sichuan basin, where the wartime capital of Chongqing and the southwestern home front was located.[91] Thirdly, the floods in Henan and Anhui crushed the tracks and bridges of the Beijing–Wuhan Railway, Tianjin–Pukou Railway and Longhai Railway, thereby preventing the Japanese Army from mobilizing their machines and troops across the theaters of North China, Central China and Northwest China.[92] The short term strategic intent was to stop the quick mobilization of Japanese Army from North China into the Battle of Wuhan.[92][93][94][95]1939–1940: Chinese counterattack and stalemate[edit]

From the beginning of 1939, the war entered a new phase with the unprecedented defeat of the Japanese at Battle of Suixian–Zaoyang, 1st Battle of Changsha, Battle of South Guangxi and Battle of Zaoyi. These outcomes encouraged the Chinese to launch their first large-scale counter-offensive against the IJA in early 1940; however, due to its low military-industrial capacity and limited experience in modern warfare, this offensive was defeated. Afterwards Chiang could not risk any more all-out offensive campaigns given the poorly trained, under-equipped, and disorganized state of his armies and opposition to his leadership both within the Kuomintang and in China in general. He had lost a substantial portion of his best trained and equipped troops in the Battle of Shanghai and was at times at the mercy of his generals, who maintained a high degree of autonomy from the central KMT government.

During the offensive, Hui forces in Suiyuan under generals Ma Hongbin and Ma Buqing routed the Imperial Japanese Army and their puppet Inner Mongol forces and prevented the planned Japanese advance into northwest China. Ma Hongbin's father Ma Fulu had fought against Japanese in the Boxer Rebellion. General Ma Biao led Hui, Salar and Dongxiang cavalry to defeat the Japanese at the Battle of Huaiyang. Ma Biao fought against the Japanese in the Boxer Rebellion.

After 1940, the Japanese encountered tremendous difficulties in administering and garrisoning the seized territories, and tried to solve their occupation problems by implementing a strategy of creating friendly puppet governments favourable to Japanese interests in the territories conquered, most prominently the Wang Jingwei Government headed by former KMT premier Wang Jingwei. However, atrocities committed by the Imperial Japanese Army, as well as Japanese refusal to delegate any real power, left the puppets very unpopular and largely ineffective. The only success the Japanese had was to recruit a large Collaborationist Chinese Army to maintain public security in the occupied areas.

Japanese expansion[edit]

By 1941, Japan held most of the eastern coastal areas of China and Vietnam, but guerrilla fighting continued in these occupied areas. Japan had suffered high casualties which resulted from unexpectedly stubborn Chinese resistance, and neither side could make any swift progress in the manner of Nazi Germany in Western Europe.

By 1943, Guangdong had experienced famine. As the situation worsened, New York Chinese compatriots received a letter stating that 600,000 people were killed in Siyi by starvation.[96]

Chinese resistance strategy[edit]

The basis of Chinese strategy before the entrance of the Western Allies can be divided into two periods as follows:

- First Period: 7 July 1937 (Battle of Lugou Bridge) – 25 October 1938 (end of the Battle of Wuhan with the fall of the city).

- Second Period: 25 October 1938 (following the Fall of Wuhan) – December 1941 (before the Allies' declaration of war on Japan).

Unlike Japan, China was unprepared for total war and had little military-industrial strength, no mechanized divisions, and few armoured forces.[97] Up until the mid-1930s, China had hoped that the League of Nations would provide countermeasures to Japan's aggression.[citation needed]

Second phase: October 1938 – December 1941[edit]

During this period, the main Chinese objective was to drag out the war for as long as possible in a war of attrition, thereby exhausting Japanese resources while it was building up China's military capacity. American general Joseph Stilwell called this strategy "winning by outlasting". The NRA adopted the concept of "magnetic warfare" to attract advancing Japanese troops to definite points where they were subjected to ambush, flanking attacks, and encirclements in major engagements. The most prominent example of this tactic was the successful defense of Changsha in 1939 (and again in the 1941 battle), in which heavy casualties were inflicted on the IJA.

Local Chinese resistance forces, organized separately by both the CCP and the KMT, continued their resistance in occupied areas to make Japanese administration over the vast land area of China difficult. In 1940, the Chinese Red Army launched a major offensive in north China, destroying railways and a major coal mine. These constant guerilla and sabotage operations deeply frustrated the Imperial Japanese Army and they led them to employ the "Three Alls Policy" (kill all, loot all, burn all) (三光政策, Hanyu Pinyin: Sānguāng Zhèngcè, Japanese On: Sankō Seisaku). It was during this period that the bulk of Japanese war crimes were committed.

By 1941, Japan had occupied much of north and coastal China, but the KMT central government and military had retreated to the western interior to continue their resistance, while the Chinese communists remained in control of base areas in Shaanxi. In the occupied areas, Japanese control was mainly limited to railroads and major cities ("points and lines"). They did not have a major military or administrative presence in the vast Chinese countryside, where Chinese guerrillas roamed freely.

The United States strongly supported China starting in 1937 and warned Japan to get out.[98] However, the United States continued to sell Japan petroleum and scrap metal exports until the Japanese invasion of French Indochina when the U.S. imposed a scrap metal and oil embargo against Japan (and froze all Japanese assets) in the summer of 1941.[99] As the Soviets prepared for war against Nazi Germany in June 1941, and all new Soviet combat aircraft was needed in the west, Chiang Kai-shek sought American support through the Lend-Lease Act that was promised in March 1941.

After the Lend-Lease Act was passed, American financial and military aid began to trickle in.[100] Claire Lee Chennault commanded the 1st American Volunteer Group (nicknamed the Flying Tigers), with American pilots flying American warplanes which were painted with the Chinese flag to attack the Japanese. He headed both the volunteer group and the uniformed U.S. Army Air Forces units that replaced it in 1942.[101] However, it was the Soviets that provided the greatest material help for China's war of resistance against the imperial Japanese invasion from 1937 into 1941, with fighter aircraft for the Nationalist Chinese Air Force and artillery and armour for the Chinese Army through the Sino-Soviet Treaty; Operation Zet also provided for a group of Soviet volunteer combat aviators to join the Chinese Air Force in the fight against the Japanese occupation from late 1937 through 1939. The United States embargoed Japan in 1941 depriving her of shipments of oil and various other resources necessary to continue the war in China. This pressure, which was intended to disparage a continuation of the war and bring Japan into negotiation, resulted in the Attack on Pearl Harbor and Japan's drive south to procure from the resource-rich European colonies in Southeast Asia by force the resources which the United States had denied to them.

Relationship between the Nationalists and the Communists[edit]

After the Mukden Incident in 1931, Chinese public opinion was strongly critical of Manchuria's leader, the "young marshal" Zhang Xueliang, for his non-resistance to the Japanese invasion, even though the Kuomintang central government was also responsible for this policy, giving Zhang an order to "improvise" while not offering support. After losing Manchuria to the Japanese, Zhang and his Northeast Army were given the duty of suppressing the Red Army of the Chinese Communist Party in Shaanxi after their Long March. This resulted in great casualties for his Northeast Army, which received no support in manpower or weaponry from Chiang Kai-shek.

On 12 December 1936, a deeply disgruntled Zhang Xueliang kidnapped Chiang Kai-shek in Xi'an, hoping to force an end to the conflict between KMT and CCP. To secure the release of Chiang, the KMT agreed to a temporary ceasefire of the Chinese Civil War and, on 24 December, the formation of a United Front with the communists against Japan. The alliance having salutary effects for the beleaguered CCP, agreed to form the New Fourth Army and the 8th Route Army and place them under the nominal control of the NRA. In agreement with KMT, Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region and Shanxi-Chahar-Hebei Border Region were created. They were controlled by CCP. To raise funds, the CCP in the Shaan-Gan-Ning Base Area fostered and taxed opium production and dealing, selling to Japanese-occupied and KMT-controlled provinces.[102][103] The CCP's Red Army fought alongside KMT forces during the Battle of Taiyuan, and the high point of their cooperation came in 1938 during the Battle of Wuhan.

Despite Japan's steady territorial gains in northern China, the coastal regions, and the rich Yangtze River Valley in central China, the distrust between the two antagonists was scarcely veiled. The uneasy alliance began to break down by late 1938, partially due to the Communists' aggressive efforts to expand their military strength by absorbing Chinese guerrilla forces behind Japanese lines. Chinese militia who refused to switch their allegiance were often labelled "collaborators" and attacked by CCP forces. For example, the Red Army led by He Long attacked and wiped out a brigade of Chinese militia led by Zhang Yin-wu in Hebei in June 1939.[104] Starting in 1940, open conflict between Nationalists and Communists became more frequent in the occupied areas outside of Japanese control, culminating in the New Fourth Army Incident in January 1941.

Afterwards, the Second United Front completely broke down and Chinese Communists leader Mao Zedong outlined the preliminary plan for the CCP's eventual seizure of power from Chiang Kai-shek. Mao himself is quoted outlining the "721" policy, saying "We are fighting 70 percent for self development, 20 percent for compromise, and 10 percent against Japan".[citation needed] Mao began his final push for consolidation of CCP power under his authority, and his teachings became the central tenets of the CCP doctrine that came to be formalized as "Mao Zedong Thought". The communists also began to focus most of their energy on building up their sphere of influence wherever opportunities were presented, mainly through rural mass organizations, administrative, land and tax reform measures favouring poor peasants; while the Nationalists attempted to neutralize the spread of Communist influence by military blockade of areas controlled by CCP and fighting the Japanese at the same time.[105]

Entrance of the Western Allies[edit]

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States declared war against Japan, and within days China joined the Allies in formal declaration of war against Japan, Germany and Italy.[citation needed] As the Western Allies entered the war against Japan, the Sino-Japanese War would become part of a greater conflict, the Pacific theatre of World War II. Almost immediately, Chinese troops achieved another decisive victory in the Battle of Changsha, which earned the Chinese government much prestige from the Western Allies. President Franklin D. Roosevelt referred to the United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union and China as the world's "Four Policemen"; his primary reason for elevating China to such a status was the belief that after the war it would serve as a bulwark against the Soviet Union.[106]

Knowledge of Japanese naval movements in the Pacific was provided to the American Navy by the Sino-American Cooperative Organization (SACO) which was run by the Chinese intelligence head Dai Li.[107] Philippine and Japanese ocean weather was affected by weather originating near northern China.[108] The base of SACO was located in Yangjiashan.[109]

Chiang Kai-shek continued to receive supplies from the United States. However, in contrast to the Arctic supply route to the Soviet Union which stayed open through most of the war, sea routes to China and the Yunnan–Vietnam Railway had been closed since 1940. Therefore, between the closing of the Burma Road in 1942 and its re-opening as the Ledo Road in 1945, foreign aid was largely limited to what could be flown in over "The Hump". In Burma, on 16 April 1942, 7,000 British soldiers were encircled by the Japanese 33rd Division during the Battle of Yenangyaung and rescued by the Chinese 38th Division.[110] After the Doolittle Raid, the Imperial Japanese Army conducted a massive sweep through Zhejiang and Jiangxi of China, now known as the Zhejiang-Jiangxi Campaign, with the goal of finding the surviving American airmen, applying retribution on the Chinese who aided them and destroying air bases. The operation started 15 May 1942, with 40 infantry battalions and 15–16 artillery battalions but was repelled by Chinese forces in September.[111] During this campaign, the Imperial Japanese Army left behind a trail of devastation and also spread cholera, typhoid, plague and dysentery pathogens. Chinese estimates allege that as many as 250,000 civilians, the vast majority of whom were destitute Tanka boat people and other pariah ethnicities unable to flee, may have died of disease.[112] It caused more than 16 million civilians to evacuate far away deep inward China. 90% of Ningbo's population had already fled before battle started.[113]

Most of China's industry had already been captured or destroyed by Japan, and the Soviet Union refused to allow the United States to supply China through the Kazakhstan into Xinjiang as the Xinjiang warlord Sheng Shicai had turned anti-Soviet in 1942 with Chiang's approval. For these reasons, the Chinese government never had the supplies and equipment needed to mount major counter-offensives. Despite the severe shortage of matériel, in 1943, the Chinese were successful in repelling major Japanese offensives in Hubei and Changde.

Chiang was named Allied commander-in-chief in the China theater in 1942. American general Joseph Stilwell served for a time as Chiang's chief of staff, while simultaneously commanding American forces in the China-Burma-India Theater. For many reasons, relations between Stilwell and Chiang soon broke down. Many historians (such as Barbara W. Tuchman) have suggested it was largely due to the corruption and inefficiency of the Kuomintang government, while others (such as Ray Huang and Hans van de Ven) have depicted it as a more complicated situation. Stilwell had a strong desire to assume total control of Chinese troops and pursue an aggressive strategy, while Chiang preferred a patient and less expensive strategy of out-waiting the Japanese. Chiang continued to maintain a defensive posture despite Allied pleas to actively break the Japanese blockade, because China had already suffered tens of millions of war casualties and believed that Japan would eventually capitulate in the face of America's overwhelming industrial output. For these reasons the other Allies gradually began to lose confidence in the Chinese ability to conduct offensive operations from the Asian mainland, and instead concentrated their efforts against the Japanese in the Pacific Ocean Areas and South West Pacific Area, employing an island hopping strategy.[114]

Long-standing differences in national interest and political stance among China, the United States, and the United Kingdom remained in place. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was reluctant to devote British troops, many of whom had been routed by the Japanese in earlier campaigns, to the reopening of the Burma Road; Stilwell, on the other hand, believed that reopening the road was vital, as all China's mainland ports were under Japanese control. The Allies' "Europe first" policy did not sit well with Chiang, while the later British insistence that China send more and more troops to Indochina for use in the Burma Campaign was seen by Chiang as an attempt to use Chinese manpower to defend British colonial possessions. Chiang also believed that China should divert its crack army divisions from Burma to eastern China to defend the airbases of the American bombers that he hoped would defeat Japan through bombing, a strategy that American general Claire Lee Chennault supported but which Stilwell strongly opposed. In addition, Chiang voiced his support of Indian independence in a 1942 meeting with Mahatma Gandhi, which further soured the relationship between China and the United Kingdom.[115]

American and Canadian-born Chinese were recruited to act as covert operatives in Japanese-occupied China. Employing their racial background as a disguise, their mandate was to blend in with local citizens and wage a campaign of sabotage. Activities focused on destruction of Japanese transportation of supplies (signaling bomber destruction of railroads, bridges).[116]Chinese forces advanced to northern Burma in late 1943, besieged Japanese troops in Myitkyina, and captured Mount Song.[117]The British and Commonwealth forces had their operation in Mission 204 which attempted to provide assistance to the Chinese Nationalist Army.[118] The first phase in 1942 under command of SOE achieved very little, but lessons were learned and a second more successful phase, commenced in February 1943 under British Military command, was conducted before the Japanese Operation Ichi-Go offensive in 1944 compelled evacuation.[119]

Operation Ichi-Go[edit]

In 1944, China became overconfident due to several victories against Japan in Burma. Nationalist China had also diverted soldiers and deployed them to Xinjiang in 1942. Former Soviet client Sheng Shicai,who was allied to the Soviets since the Soviet invasion of Xinjiang in 1934, turned to the Nationalists. The fighting then escalated in early 1944 with the Ili Rebellion with Soviet backed Uyghur Communist rebels, causing China to fight enemies on two fronts with 120,000 Chinese soldiers fighting against the Ili rebellion. The aim of the Japanese Operation Ichigo was to destroy American airfields in southern China that threatened the Japanese home islands with bombing and to link railways in Beijing, Hankou and Canton cities from northern China in Beijing to southern China's coast on Canton. Japan was alarmed by American air raids against Japanese forces in Taiwan's Hsinchu airfield by American bombers based in southern China, correctly deducing that southern China could become the base of a major American bombing campaign against the Japanese home islands so Japan resolved to destroy and capture all airbases where American bombers operated from in Operation Ichigo.[citation needed]

Operation Ichi-Go was the largest military campaign of the Second Sino-Japanese War.[120]: 19 The campaign mobilized 500,000 Japanese troops, 100,000 horses, 1,500 artillery pieces, and 800 tanks.[120]: 19 The 750,000 casualty figure for Nationalist Chinese forces are not all dead and captured, Cox included in the 750,000 casualties that China incurred in Ichigo soldiers who simply "melted away" and others who were rendered combat ineffective besides killed and captured soldiers.[121]

Chiang Kai-shek and the Republic of China authorities deliberately ignored and dismissed a tip passed on to the Chinese government in Chongqing by the French military that the French picked up in colonial French Indochina on the impending Japanese offensive to link the three cities. The Chinese military believed it to be a fake tip planted by Japan to mislead them, since only 30,000 Japanese soldiers started the first maneuver of Operation Ichigo in northern China crossing the Yellow river, so the Chinese assumed it would be a local operation in northern China only. Another major factor was that the battlefront between China and Japan was static and stabilized since 1940 and continued for four years that way until Operation Ichigo in 1944, so Chiang assumed that Japan would continue the same posture and remain behind the lines in pre-1940 occupied territories of north China only, bolstering the puppet Chinese government of Wang Jingwei and exploiting resources there. The Japanese had indeed acted this way from 1940 to 1944, with the Japanese only making a few failed weak attempts to capture China's provisional capital in Chongqing on the Yangtze river, which they quickly abandoned before 1944. Japan also exhibited no intention before of linking the transcontinental Beijing Hankow Canton railways.[citation needed]

China also was made confident by its three victories in a row defending Changsha against Japan in 1939, 1941, and 1942. China had also defeated Japan in the India-Burma theater in Southeast Asia with X Force and Y Force and the Chinese could not believe Japan had carelessly let information slip into French hands, believing Japan deliberately fed misinformation to the French to divert Chinese troops from India and Burma. China believed the Burma theater to be far more important for Japan than southern China and that Japanese forces in southern China would continue to assume a defensive posture only. China believed the initial Japanese attack in Ichigo to be a localized feint and distraction in northern China so Chinese troops numbering 400,000 in North China deliberately withdrew without a fight when Japan attacked, assuming it was just another localized operation after which the Japanese would withdraw. This mistake led to the collapse of Chinese defensive lines as the Japanese soldiers, which eventually numbered in the hundreds of thousands, kept pressing the attack from northern China to central China to southern China's provinces as Chinese soldiers deliberately withdrew leading to confusion and collapse, except at the Defense of Hengyang where 17,000 outnumbered Chinese soldiers held out against over 110,000 Japanese soldiers for months in the longest siege of the war, inflicting 19,000–60,000 deaths on the Japanese.[citation needed] In late November 1944, the Japanese advanced slowed approximately 300 miles from Chongqing as it experienced shortages of trained soldiers and materiel.[120]: 21 At Tushan in Guizhou province, the Nationalist government of China was forced to deploy five armies of the 8th war zone that they were using for the entire war up to Ichigo to contain the Communist Chinese to instead fight Japan. But at that point, dietary deficiencies of Japanese soldiers and increasing casualties suffered by Japan forced Japan to end Operation Ichigo in Guizhou, causing the operation to cease.[citation needed]

In late November 1944, the Japanese advanced slowed approximately 300 miles from Chongqing as it experienced shortages of trained soldiers and materiel.[120]: 21 Although Operation Ichi-Go achieved its goals of seizing United States air bases and establishing a potential railway corridor from Manchukuo to Hanoi, it did so too late to impact the result of the broader war.[120]: 21 American bombers in Chengdu were moved to the Mariana Islands where, along with bombers from bases in Saipan and Tinian, they could still bomb the Japanese home islands.[120]: 22

After Operation Ichigo, Chiang Kai-shek started a plan to withdraw Chinese troops from the Burma theatre against Japan in Southeast Asia for a counter offensive called "White Tower" and "Iceman" against Japanese soldiers in China in 1945.[122]

The poor performance of Chiang Kai-shek's forces in opposing the Japanese advance during Operation Ichigo became widely viewed as demonstrating Chiang's incompetence.[72]: 3 It irreparably damaged the Roosevelt administration's view of Chiang and the KMT.[61]: 75 The campaign further weakened the Nationalist economy and government revenues.[72]: 22–24 Because of the Nationalists' increasing inability to fund the military, Nationalist authorities overlooked military corruption and smuggling.[72]: 24–25 The Nationalist army increasingly turned to raiding villages to press-gang peasants into service and force marching them to assigned units.[72]: 25 Approximately 10% of these peasants died before reaching their units.[72]: 25

By the end of 1944, Chinese troops under the command of Sun Li-jen attacking from India, and those under Wei Lihuang attacking from Yunnan, joined forces in Mong-Yu, successfully driving the Japanese out of North Burma and securing the Ledo Road, China's vital supply artery.[123] In Spring 1945 the Chinese launched offensives that retook Hunan and Guangxi. With the Chinese army progressing well in training and equipment, Wedemeyer planned to launch Operation Carbonado in summer 1945 to retake Guangdong, thus obtaining a coastal port, and from there drive northwards toward Shanghai. However, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and Soviet invasion of Manchuria hastened Japanese surrender and these plans were not put into action.[124]

Chinese industrial base and the CIC[edit]

Foreign aid[edit]

Before the start of full-scale warfare of the Second Sino-Japanese War, Germany had since the time of the Weimar Republic, provided much equipment and training to crack units of the National Revolutionary Army of China, including some aerial-combat training with the Luftwaffe to some pilots of the pre-Nationalist Air Force of China.[125] A number of foreign powers, including the Americans, Italians and Japanese, provided training and equipment to different air force units of pre-war China. With the outbreak of full-scale war between China and the Empire of Japan, the Soviet Union became the primary supporter for China's war of resistance through the Sino-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact from 1937 to 1941. When the Imperial Japanese invaded French Indochina, the United States enacted the oil and steel embargo against Japan and froze all Japanese assets in 1941,[126][127] and with it came the Lend-Lease Act of which China became a beneficiary on 6 May 1941; from there, China's main diplomatic, financial and military supporter came from the U.S., particularly following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Overseas Chinese[edit]

Over 3,200 overseas Chinese drivers and motor vehicle mechanics embarked to wartime China to support military and logistics supply lines, especially through Indo-China, which became of absolute tantamount importance when the Japanese cut-off all ocean-access to China's interior with the capture of Nanning after the Battle of South Guangxi. Overseas Chinese communities in the U.S. raised money and nurtured talent in response to Imperial Japan's aggressions in China, which helped to fund an entire squadron of Boeing P-26 fighter planes purchased for the looming war situation between China and the Empire of Japan; over a dozen Chinese-American aviators, including John "Buffalo" Huang, Arthur Chin, Hazel Ying Lee, Chan Kee-Wong et al., formed the original contingent of foreign volunteer aviators to join the Chinese air forces (some provincial or warlord air forces, but ultimately all integrating into the centralized Chinese Air Force; often called the Nationalist Air Force of China) in the "patriotic call to duty for the motherland" to fight against the Imperial Japanese invasion.[128][129][130][131] Several of the original Chinese-American volunteer pilots were sent to Lagerlechfeld Air Base in Germany for aerial-gunnery training by the Chinese Air Force in 1936.[132]

German[edit]

Prior to the war, Germany and China were in close economic and military cooperation, with Germany helping China modernize its industry and military in exchange for raw materials. Germany sent military advisers such as Alexander von Falkenhausen to China to help the KMT government reform its armed forces.[133] Some divisions began training to German standards and were to form a relatively small but well trained Chinese Central Army. By the mid-1930s about 80,000 soldiers had received German-style training.[134] After the KMT lost Nanjing and retreated to Wuhan, Hitler's government decided to withdraw its support of China in 1938 in favour of an alliance with Japan as its main anti-Communist partner in East Asia.[135]

Soviet[edit]

After Germany and Japan signed the anti-communist Anti-Comintern Pact, the Soviet Union hoped to keep China fighting, in order to deter a Japanese invasion of Siberia and save itself from a two-front war. In September 1937, they signed the Sino-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact and approved Operation Zet, the formation of a secret Soviet volunteer air force, in which Soviet technicians upgraded and ran some of China's transportation systems. Bombers, fighters, supplies and advisors arrived, headed by Aleksandr Cherepanov. Prior to the Western Allies, the Soviets provided the most foreign aid to China: some $250 million in credits for munitions and other supplies. The Soviet Union defeated Japan in the Battles of Khalkhin Gol in May – September 1939, leaving the Japanese reluctant to fight the Soviets again.[136] In April 1941, Soviet aid to China ended with the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact and the beginning of the Great Patriotic War. This pact enabled the Soviet Union to avoid fighting against Germany and Japan at the same time. In August 1945, the Soviet Union annulled the neutrality pact with Japan and invaded Manchuria, Inner Mongolia, the Kuril Islands, and northern Korea. The Soviets also continued to support the Chinese Communist Party. In total, 3,665 Soviet advisors and pilots served in China,[137] and 227 of them died fighting there.[138]

Western allies[edit]

United States[edit]

The United States generally avoided taking sides between Japan and China until 1940, providing virtually no aid to China in this period. For instance, the 1934 Silver Purchase Act signed by President Roosevelt caused chaos in China's economy which helped the Japanese war effort. The 1933 Wheat and Cotton Loan mainly benefited American producers, while aiding to a smaller extent both Chinese and Japanese alike. This policy was due to US fear of breaking off profitable trade ties with Japan, in addition to US officials and businesses perception of China as a potential source of massive profit for the US by absorbing surplus American products, as William Appleman Williams states.[139]

From December 1937, events such as the Japanese attack on USS Panay and the Nanjing Massacre swung public opinion in the West sharply against Japan and increased their fear of Japanese expansion, which prompted the United States, the United Kingdom, and France to provide loan assistance for war supply contracts to China. Australia also prevented a Japanese government-owned company from taking over an iron mine in Australia, and banned iron ore exports in 1938.[140] However, in July 1939, negotiations between Japanese Foreign Minister Arita Khatira and the British Ambassador in Tokyo, Robert Craigie, led to an agreement by which the United Kingdom recognized Japanese conquests in China. At the same time, the US government extended a trade agreement with Japan for six months, then fully restored it. Under the agreement, Japan purchased trucks for the Kwantung Army,[141] machine tools for aircraft factories, strategic materials (steel and scrap iron up to 16 October 1940, petrol and petroleum products up to 26 June 1941),[142] and various other much-needed supplies.

In a hearing before the United States Congress House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs on Wednesday, 19 April 1939, the acting chairman Sol Bloom and other Congressmen interviewed Maxwell S. Stewart, a former Foreign Policy Association research staff and economist who charged that America's Neutrality Act and its "neutrality policy" was a massive farce which only benefited Japan and that Japan did not have the capability nor could ever have invaded China without the massive amount of raw material America exported to Japan. America exported far more raw material to Japan than to China in the years 1937–1940.[143][144][145][146] According to the United States Congress, the U.S.'s third largest export destination was Japan until 1940 when France overtook it due to France being at war too. Japan's military machine acquired war materials, automotive equipment, steel, scrap iron, copper, oil, that it wanted from the United States in 1937–1940 and was allowed to purchase aerial bombs, aircraft equipment, and aircraft from America up to the summer of 1938. War essentials exports from the United States to Japan increased by 124% along with a general increase of 41% of all American exports from 1936 to 1937 when Japan invaded China. Japan's war economy was fueled by exports to the United States at over twice the rate immediately preceding the war.[147] According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, Japan corresponded to the following share of American exports;

Japan invaded and occupied the northern part of French Indochina in September 1940 to prevent China from receiving the 10,000 tons of materials delivered monthly by the Allies via the Haiphong–Yunnan Fou Railway line.

On 22 June 1941, Germany attacked the Soviet Union. In spite of non-aggression pacts or trade connections, Hitler's assault threw the world into a frenzy of re-aligning political outlooks and strategic prospects.

On 21 July, Japan occupied the southern part of French Indochina (southern Vietnam and Cambodia), contravening a 1940 gentlemen's agreement not to move into southern French Indochina. From bases in Cambodia and southern Vietnam, Japanese planes could attack Malaya, Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies. As the Japanese occupation of northern French Indochina in 1940 had already cut off supplies from the West to China, the move into southern French Indochina was viewed as a direct threat to British and Dutch colonies. Many principal figures in the Japanese government and military (particularly the navy) were against the move, as they foresaw that it would invite retaliation from the West.

On 24 July 1941, Roosevelt requested Japan withdraw all its forces from Indochina. Two days later the US and the UK began an oil embargo; two days after that the Netherlands joined them. This was a decisive moment in the Second Sino-Japanese War. The loss of oil imports made it impossible for Japan to continue operations in China on a long-term basis. It set the stage for Japan to launch a series of military attacks against the Allies, including the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.

In mid-1941, the United States government financed the creation of the American Volunteer Groups (AVG), of which one the "Flying Tigers" reached China, to replace the withdrawn Soviet volunteers and aircraft. The Flying Tigers did not enter actual combat until after the United States had declared war on Japan. Led by Chennault, their early combat success of 300 kills against a loss of 12 of their newly introduced Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighters heavily armed with six 0.50-inch caliber machine guns and very fast diving speeds earned them wide recognition at a time when the Chinese Air Force and Allies in the Pacific and SE Asia were suffering heavy losses, and soon afterwards their "boom and zoom" high-speed hit-and-run air combat tactics would be adopted by the United States Army Air Forces.[148]

The Sino-American Cooperative Organization[149][150][151] was an organization created by the SACO Treaty signed by the Republic of China and the United States of America in 1942 that established a mutual intelligence gathering entity in China between the respective nations against Japan. It operated in China jointly along with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), America's first intelligence agency and forerunner of the CIA while also serving as joint training program between the two nations. Among all the wartime missions that Americans set up in China, SACO was the only one that adopted a policy of "total immersion" with the Chinese. The "Rice Paddy Navy" or "What-the-Hell Gang" operated in the China-Burma-India theater, advising and training, forecasting weather and scouting landing areas for USN fleet and Gen Claire Chennault's 14th AF, rescuing downed American flyers, and intercepting Japanese radio traffic. An underlying mission objective during the last year of war was the development and preparation of the China coast for Allied penetration and occupation. Fujian was scouted as a potential staging area and springboard for the future military landing of the Allies of World War II in Japan.

United Kingdom[edit]

After the Tanggu Truce of 1933, Chiang Kai-Shek and the British government would have more friendly relations but were uneasy due to British foreign concessions there. During the Second Sino-Japanese War the British government would initially have an impartial viewpoint toward the conflict urging both to reach an agreement and prevent war. British public opinion would swing in favor of the Chinese after Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen's car which had Union Jacks on it was attacked by Japanese aircraft with Hugessen being temporarily paralyzed with outrage against the attack from the public and government. The British public were largely supportive of the Chinese and many relief efforts were untaken to help China. Britain at this time was beginning the process of rearmament and the sale of military surplus was banned but there was never an embargo on private companies shipping arms. A number of unassembled Gloster Gladiator fighters were imported to China via Hong Kong for the Chinese Air Force. Between July 1937 and November 1938 on average 60,000 tons of munitions were shipped from Britain to China via Hong Kong. Attempts by the United Kingdom and the United States to do a joint intervention were unsuccessful as both countries had rocky relations in the interwar era.[152]

In February 1941 a Sino-British agreement was forged whereby British troops would assist the Chinese "Surprise Troops" units of guerrillas already operating in China, and China would assist Britain in Burma.[153]

A British-Australian commando operation, Mission 204, was initialized in February 1942 to provide training to Chinese guerrilla troops. The mission conducted two operations, mostly in the provinces of Yunnan and Jiangxi. The first phase achieved very little but a second more successful phase was conducted before withdrawal.[154]

Commandos working with the Free Thai Movement also operated in China, mostly while on their way into Thailand.[155]

After the Japanese blocked the Burma Road in April 1942, and before the Ledo Road was finished in early 1945, the majority of US and British supplies to the Chinese had to be delivered via airlift over the eastern end of the Himalayan Mountains known as "the Hump". Flying over the Himalayas was extremely dangerous, but the airlift continued daily to August 1945, at great cost in men and aircraft.

Involvement of French Indochina[edit]

The Chinese Kuomintang also supported the Vietnamese Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng (VNQDD) in its battle against French and Japanese imperialism.

In Guangxi, Chinese military leaders were organizing Vietnamese nationalists against the Japanese. The VNQDD had been active in Guangxi and some of their members had joined the KMT army.[156] Under the umbrella of KMT activities, a broad alliance of nationalists emerged. With Ho at the forefront, the Viet Nam Doc Lap Dong Minh Hoi (Vietnamese Independence League, usually known as the Viet Minh) was formed and based in the town of Jingxi.[156] The pro-VNQDD nationalist Ho Ngoc Lam, a KMT army officer and former disciple of Phan Bội Châu,[citation needed] was named as the deputy of Phạm Văn Đồng, later to be Ho's Prime Minister. The front was later broadened and renamed the Viet Nam Giai Phong Dong Minh (Vietnam Liberation League).[156]

The Viet Nam Revolutionary League was a union of various Vietnamese nationalist groups, run by the pro Chinese VNQDD. Chinese KMT General Zhang Fakui created the league to further Chinese influence in Indochina, against the French and Japanese. Its stated goal was for unity with China under the Three Principles of the People, created by KMT founder Dr. Sun and opposition to Japanese and French Imperialists.[157][158] The Revolutionary League was controlled by Nguyen Hai Than, who was born in China and could not speak Vietnamese[citation needed]. General Zhang shrewdly blocked the Communists of Vietnam, and Ho Chi Minh from entering the league, as Zhang's main goal was Chinese influence in Indochina.[159] The KMT utilized these Vietnamese nationalists during World War II against Japanese forces.[156] Franklin D. Roosevelt, through General Stilwell, privately made it clear that they preferred that the French not reacquire French Indochina (modern day Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos) after the war was over. Roosevelt offered Chiang Kai-shek control of all of Indochina. It was said that Chiang Kai-shek replied: "Under no circumstances!"[160]

After the war, 200,000 Chinese troops under General Lu Han were sent by Chiang Kai-shek to northern Indochina (north of the 16th parallel) to accept the surrender of Japanese occupying forces there, and remained in Indochina until 1946, when the French returned.[161] The Chinese used the VNQDD, the Vietnamese branch of the Chinese Kuomintang, to increase their influence in French Indochina and to put pressure on their opponents.[162] Chiang Kai-shek threatened the French with war in response to maneuvering by the French and Ho Chi Minh's forces against each other, forcing them to come to a peace agreement. In February 1946, he also forced the French to surrender all of their concessions in China and to renounce their extraterritorial privileges in exchange for the Chinese withdrawing from northern Indochina and allowing French troops to reoccupy the region. Following France's agreement to these demands, the withdrawal of Chinese troops began in March 1946.[163][164][165][166]

Central Asian rebellions[edit]

In 1937, then pro-Soviet General Sheng Shicai invaded Dunganistan accompanied by Soviet troops to defeat General Ma Hushan of the KMT 36th Division. General Ma expected help from Nanjing, but did not receive it. The Nationalist government was forced to deny these maneuvers as "Japanese propaganda", as it needed continued military supplies from the Soviets.[167]

As the war went on, Nationalist General Ma Buqing, was in virtual control of the Gansu corridor,[168] Ma had earlier fought against the Japanese, but because the Soviet threat was great, Chiang in July 1942 directed him to move 30,000 of his troops to the Tsaidam marsh in the Qaidam Basin of Qinghai.[169][170] Chiang further named Ma as Reclamation Commissioner, to threaten Sheng's southern flank in Xinjiang, which bordered Tsaidam.

After Ma Buqing left Gansu, Nationalist troops from central China flooded the area, and infiltrated Soviet occupied Xinjiang, gradually reclaiming it and forcing Sheng to break with the Soviets. The Nationalist government ordered Ma Bufang to march his troops into Xinjiang to intimidate Sheng and provide protection for Chinese settling in the area.[171]

The Ili Rebellion broke out in Xinjiang when the Kuomintang Hui Officer Liu Bin-Di was killed while fighting Turkic Uyghur rebels in November 1944. The Soviet Union supported the Turkic rebels against the Kuomintang, and Kuomintang forces fought back.[172]

Ethnic minorities[edit]

Japan attempted to reach out to Chinese ethnic minorities in order to rally them to their side against the Han Chinese, but only succeeded with certain Manchu, Mongol, Uyghur and Tibetan elements.

The Japanese attempt to get the Muslim Hui people on their side failed, as many Chinese generals such as Bai Chongxi, Ma Hongbin, Ma Hongkui, and Ma Bufang were Hui. The Japanese attempted to approach Ma Bufang but were unsuccessful in making any agreement with him.[173] Ma Bufang ended up supporting the anti-Japanese Imam Hu Songshan, who prayed for the destruction of the Japanese.[174] Ma became chairman (governor) of Qinghai in 1938 and commanded a group army. He was appointed because of his anti-Japanese inclinations,[175] and was such an obstruction to Japanese agents trying to contact the Tibetans that he was called an "adversary" by a Japanese agent.[176]

Hui Muslims[edit]

Hui cemeteries were destroyed for military reasons.[177] Many Hui fought in the war against the Japanese such as Bai Chongxi, Ma Hongbin, Ma Hongkui, Ma Bufang, Ma Zhanshan, Ma Biao, Ma Zhongying, Ma Buqing and Ma Hushan. Qinghai Tibetans served in the Qinghai army against the Japanese.[178] The Qinghai Tibetans view the Tibetans of Central Tibet (Tibet proper, ruled by the Dalai Lamas from Lhasa) as distinct and different from themselves, and even take pride in the fact that they were not ruled by Lhasa ever since the collapse of the Tibetan Empire.[179]