Геноцид сербов в Независимом государстве Хорватия

| Геноцид сербов в Независимом государстве Хорватия | |

|---|---|

| Часть Второй мировой войны в Югославии | |

(clockwise from top)

| |

| Location | |

| Date | 1941–1945 |

| Target | Serbs (largely Serbs of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina) |

Attack type | Genocide, ethnic cleansing, massacres, deportation, forced conversion, others |

| Deaths | Several estimates: |

| Victims | Ethnic cleansing:

|

| Perpetrators | Ustaše |

| Motive | Anti-Serb sentiment,[7] Croatian irredentism,[8] anti-Yugoslavism,[9] Croatisation[10] |

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide |

|---|

|

| Issues |

| Related topics |

| Category |

Геноцид сербов в Независимом государстве Хорватия ( сербско-хорватский : Држави Хрватской / Геноцид над Србима у Независној Држави Хрватској ) — систематическое преследование и истребление сербов, совершенное во время Второй мировой войны фашистским Геноцид над Србимой у Независной режимом усташей в нацистской Германии, марионеточное государство известное как Независимое государство Хорватия ( сербско-хорватский : Nezavisna Država Hrvatska , NDH) между 1941 и 1945 годами. Оно осуществлялось посредством казней в лагерях смерти , а также посредством массовых убийств , этнических чисток , депортаций , насильственное обращение в другую веру и военные изнасилования . Этот геноцид был осуществлен одновременно с Холокостом в NDH, а также с геноцидом цыган , путем сочетания нацистской расовой политики с конечной целью создания этнически чистой Великой Хорватии .

Идеологическая основа движения усташей восходит к XIX веку. Несколько хорватских националистов и интеллектуалов выдвинули теории о сербах как о низшей расе . Наследие Первой мировой войны , а также противодействие группы националистов объединению в общее государство южных славян повлияли на этническую напряженность во вновь образованном Королевстве сербов, хорватов и словенцев (с 1929 — Королевство Югославия). Диктатура 6 января и последующая антихорватская политика югославского правительства, в котором доминировали сербы, в 1920-х и 1930-х годах способствовали росту националистических и крайне правых движений. Кульминацией этого стал подъем Усташей, ультранационалистической террористической . основанной Анте Павеличем организации , Движение было финансово и идеологически поддержано Бенито Муссолини , оно также было причастно к убийству короля Александра I.

Following the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941, a German puppet state known as the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was established, comprising most of modern-day Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as parts of modern-day Serbia and Slovenia, ruled by the Ustaše. The Ustaše's goal was to create an ethnically homogeneous Greater Croatia by eliminating all non-Croats, with the Serbs being the primary target but Jews, Roma and political dissidents were also targeted for elimination. Large scale massacres were committed and concentration camps were built, the largest one was the Jasenovac, which was notorious for its high mortality rate and the barbaric practices which occurred in it. Furthermore, the NDH was the only Axis puppet state to establish concentration camps specifically for children. The regime systematically murdered approximately 200,000 to 500,000 Serbs. 300,000 Serbs were further expelled and at least 200,000 more Serbs were forcibly converted, most of whom de-converted following the war. Proportional to the population, the NDH was one of the most lethal European regimes.

Mile Budak and other NDH high officials were tried and convicted of war crimes by the communist authorities. Concentration camp commandants such as Ljubo Miloš and Miroslav Filipović were captured and executed, while Aloysius Stepinac was found guilty of forced conversion. Many others escaped, including the supreme leader Ante Pavelić, most to Latin America. The genocide was not properly examined in the aftermath of the war, because the post-war Yugoslav government did not encourage independent scholars out of concern that ethnic tensions would destabilize the new communist regime. Nowadays, оn 22 April, Serbia marks the public holiday dedicated to the victims of genocide and fascism, while Croatia holds an official commemoration at the Jasenovac Memorial Site.

Historical background

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide |

|---|

|

| Issues |

| Related topics |

| Category |

The ideological foundation of the Ustaše movement reaches back to the 19th century when Ante Starčević established the Party of Rights,[11] as well as when Josip Frank seceded his extreme fraction from it and formed his own Pure Party of Rights.[12] Starčević was a major ideological influence on the Croatian nationalism of the Ustaše.[13][14] He was an advocate of Croatian unity and independence and was both anti-Habsburg, as Starčević saw the main Croatian enemy in the Habsburg Monarchy, and anti-Serb.[13] He envisioned the creation of a Greater Croatia that would include territories inhabited by Bosniaks, Serbs, and Slovenes, considering Bosniaks and Serbs to be Croats who had been converted to Islam and Eastern Orthodox Christianity.[13] In his demonization of the Serbs he claimed " how the Serbs today are dangerous for their ideas and their racial composition, how a bent for conspiracies, revolutions and coups is in their blood."[15] Starčević called the Serbs an "unclean race", a "nomadic people" and "a race of slaves, the most loathsome beasts", while the co-founder of his party, Eugen Kvaternik, denied the existence of Serbs in Croatia, seeing their political consciousness as a threat.[16][17][18][19] Milovan Đilas cites Starčević as the "father of racism" and "ideological father" of the Ustaše, while some Ustaše ideologues have linked Starčević's racial ideas to Adolf Hitler's racial ideology.[20][21]

Frank's party embraced Starčević's position that Serbs are an obstacle to Croatian political and territorial ambitions, and the aggressive anti-Serb attitudes became one of the main characteristics of the party.[22][23][19][24] The followers of the ultranationalist Pure Party of Right were known as the Frankists (Frankovci) and they would become the main pool of members of the subsequent Ustaše movement.[25][17][19][24] Following the defeat of the Central Powers in World War I and the collapse of Austria-Hungarian Empire, the provisional state was formed on the southern territories of the Empire which joined the Allies-associate Kingdom of Serbia to form the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later known as Yugoslavia), ruled by the Serbian Karađorđević dynasty. Historian John Paul Newman explained that the influence of the Frankists, as well as the legacy of the World War I had an impact on the Ustaše ideology and their future genocidal means.[24][26] Many war veterans had fought at various ranks and on various fronts on both the ‘victorious’ and ‘defeated’ sides of the war.[24] Serbia suffered the biggest casualty rate in the world, while Croats fought in the Austro-Hungarian army and two of them served as military governors of Bosnia and occupied Serbia.[27][26] They both endorsed Austria–Hungary's denationalizing plans in Serb-populated lands and supported the idea of incorporating a tamed Serbia into the Empire.[26] Newman stated that Austro-Hungarian officers' “unfaltering opposition to Yugoslavia provided a blueprint for the Croatian radical right, the Ustaše”.[26] The Frankists blamed Serbian nationalists for the defeat of Austria-Hungary and opposed the creation of Yugoslavia, which was identified by them as a cover for Greater Serbia.[24] Мass Croatian national consciousness appeared after the establishment of a common state of South Slavs and it was directed against the new Kingdom, more precisely against Serbian predominance within it.[28]

Early 20th century Croatian intellectuals Ivo Pilar, Ćiro Truhelka and Milan Šufflay influenced the Ustaše concept of nation and racial identity, as well as the theory of Serbs as an inferior race.[29][30][31] Pilar, historian, politician and lawyer, placed great emphasis on racial determinism arguing that Croats had been defined by the “Nordic-Aryan” racial and cultural heritage, while Serbs had "interbred" with the "Balkan-Romanic Vlachs”.[32] Truhelka, archeologist and historian, claimed that Bosnian Muslims were ethnic Croats, who, according to him, belonged to the racially superior Nordic race. On the other hand, Serbs belonged to the “degenerate race” of the Vlachs.[33][30] The Ustaše promoted the theories of historian and politician Šufflay, who is believed to have claimed that Croatia had been "one of the strongest ramparts of Western civilization for many centuries", which he claimed had been lost through its union with Serbia when the nation of Yugoslavia was formed in 1918.[34]

The outburst of Croatian nationalism after 1918 was one of the main threats for Yugoslavia's stability.[28] During the 1920s, Ante Pavelić, lawyer, politician and one of the Frankists, emerged as a leading spokesman for Croatian independence.[19] In 1927, he secretly contacted Benito Mussolini, dictator of Italy and founder of fascism, and presented his separatist ideas to him.[35] Pavelić proposed an independent Greater Croatia that should cover the entire historical and ethnic area of the Croats.[35] In that period, Mussolini was interested in Balkans with the aim of isolating Yugoslavia, by strengthening Italian influence on the east coast of the Adriatic Sea.[36] British historian Rory Yeomans claims that there are indication that Pavelić had been considering the formation of some kind of nationalist insurgency group as early as 1928.[37]

In June 1928, Stjepan Radić, the leader of the largest and most popular Croatian party Croatian Peasant Party (Hrvatska seljačka stranka, HSS) was mortally wounded in the parliamentary chamber by Puniša Račić, a Montenegrin Serb leader, former Chetnik member and deputy of the ruling Serb People's Radical Party. Račić also shot two other HSS deputies dead and wounded two more.[38][24][39][40] The killings provoked violent student protests in Zagreb.[38] Trying to suppress the conflict between Croatian and Serbian political parties, King Alexander I proclaimed a dictatorship with the aim of establishing the “integral Yugoslavism” and a single Yugoslav nation.[41][25][42][43] The introduction of the royal dictatorship brought separatist forces to the fore, especially among the Croats and Macedonians.[44][28] The Ustaša – Croatian Revolutionary Movement (Croatian: Ustaša – Hrvatski revolucionarni pokret) emerged as the most extreme movement of these.[45] The Ustaše was created in late 1929 or early 1930 among radical and militant student and youth groups, which existed from the late 1920s.[38] Precisely, the movement was founded by journalist Gustav Perčec and Ante Pavelić.[38] They were driven by a deep hatred of Serbs and Serbdom and claimed that, "Croats and Serbs were separated by an unbridgeable cultural gulf" which prevented them from ever living alongside each other.[34] Pavelić accused the Belgrade government of propagating “a barbarian culture and Gypsy civilization”, claiming they were spreading “atheism and bestial mentality in divine Croatia”.[46] Supporters of the Ustaše planned genocide years before World War II, for example one of Pavelić's main ideologues, Mijo Babić, wrote in 1932 that the Ustaše "will cleanse and cut whatever is rotten from the healthy body of the Croatian people".[47] In 1933, the Ustaše presented "The Seventeen Principles" that formed the official ideology of the movement. The Principles stated the uniqueness of the Croatian nation, promoted collective rights over individual rights and declared that people who were not Croat by "blood" would be excluded from political life.[48][49]

In order to explain what they saw as a "terror machine", and regularly referred to as “some excesses” by individuals, the Ustaše cited, among other things, policies of the inter-war Yugoslav government which they described as Serbian hegemony “that cost the lives of thousand Croats”.[50] Historian Jozo Tomasevich explains that that argument is not true, claiming that between December 1918 and April 1941 about 280 Croats were killed for political reasons, and that no specific motive for the killings could be identified, as they may also be linked to clashes during the agrarian reform.[51] Moreover, he stated that Serbs too were denied civil and political rights during the royal dictatorship.[40] However, Tomasevich explains that the anti-Croatian policies of the Serbian-dominated Yugoslav government in the 1920s and 1930s, as well as, the shooting of the HSS deputies by Radić were largely responsible for the creation, growth and nature of Croatian nationalist forces.[40] This culminated in the Ustaše movement and ultimately its anti-Serbian policies in the World War II, which was totally out of proportions to earlier anti-Croatian measures, in nature and extent.[40] Yeomans explains that Ustaše officials constantly emphasized crimes against Croats by the Yugoslav government and security forces, although many of them were imagined, though some of them real, as justification for their envisioned eradication of the Serbs.[52] Political scientist Tamara Pavasović Trošt, commenting on historiography and textbooks, listed the claims that terror against Serbs arose as a result of “their previous hegemony” as an example of the relativisation of Ustaše crimes.[53] Historian Aristotle Kallis explained that anti-Serb prejudices were a "chimera" which emerged through living together in Yugoslavia with continuity with previous stereotypes.[25]

The Ustaše functioned as a terrorist organization as well.[54] The first Ustaše center was established in Vienna, where brisk anti-Yugoslav propaganda soon developed and agents were prepared for terrorist actions.[55] They organized the so-called Velebit uprising in 1932, assaulting a police station in the village of Brušani in Lika.[56] In 1934, the Ustaše cooperated with Bulgarian, Hungarian and Italian right-wing extremists to assassinate King Alexander while he visited the French city of Marseille.[45] Pavelić's fascist tendencies were apparent.[19] The Ustaše movement was financially and ideologically supported by Benito Mussolini.[57] During the intensification of ties with Nazi Germany in the 1930s, Pavelić's concept of the Croatian nation became increasingly race-oriented.[46][58][59]

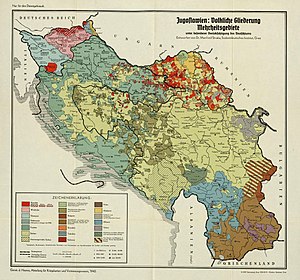

Independent State of Croatia

Serbs (including Montenegrin Serbs)

Croats

Bosnian Muslims

Germans (Danube Swabians)

In April 1941, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was invaded by the Axis powers. After Nazi forces entered Zagreb on 10 April 1941, Pavelić's closest associate Slavko Kvaternik, proclaimed the formation of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) on a Radio Zagreb broadcast. Meanwhile, Pavelić and several hundred Ustaše volunteers left their camps in Italy and travelled to Zagreb, where Pavelić declared a new government on 16 April 1941.[60] He accorded himself the title of "Poglavnik" (German: Führer, English: Chief leader). The NDH combined most of modern Croatia, all of modern Bosnia and Herzegovina and parts of modern Serbia into an "Italian-German quasi-protectorate".[61] Serbs made up about 30% of the NDH population.[62] The NDH was never fully sovereign, but it was a puppet state that enjoyed the greatest autonomy than any other regime in German-occupied Europe.[59] The Independent State of Croatia was declared to be on Croatian "ethnic and historical territory".[63]

This country can only be a Croatian country, and there is no method we would hesitate to use in order to make it truly Croatian and cleanse it of Serbs, who have for centuries endangered us and who will endanger us again if they are given the opportunity.

— Milovan Žanić, the minister of the NDH government, on 2 May 1941.[64]

The Ustaše became obsessed with creating an ethnically pure state.[65] As outlined by Ustaše ministers Mile Budak, Mirko Puk and Milovan Žanić, the strategy to achieve an ethnically pure Croatia was that:[66][67]

- One-third of the Serbs were to be killed

- One-third of the Serbs were to be expelled

- One-third of the Serbs were to be forcibly converted to Catholicism

According to historian Ivo Goldstein, this formula was never published but it is undeniable that the Ustaše applied it towards Serbs.[68]

The Ustaše movement received limited support from ordinary Croats.[69][70] In May 1941, the Ustaše had about 100,000 members who took the oath.[71][72][73] Since Vladko Maček reluctantly called on the supporters of the Croatian Peasant Party to respect and co-operate with the new regime of Ante Pavelić, he was able to use the apparatus of the party and most of the officials from the former Croatian Banovina.[74][75] Initially, Croatian soldiers who had previously served in the Austro-Hungarian army held the highest positions in the NDH armed forces.[76]

Historian Irina Ognyanova stated that the similarities between the NDH and the Third Reich included the assumption that terror and genocide were necessary for the preservation of the state.[77] Viktor Gutić made several speeches in early summer 1941, calling Serbs "former enemies" and "unwanted elements" to be cleansed and destroyed, and also threatened Croats who did not support their cause.[78] Much of the ideology of the Ustaše was based on Nazi racial theory. Like the Nazis, the Ustaše deemed Jews, Romani, and Slavs to be sub-humans (Untermensch). They endorsed the claims from German racial theorists that Croats were not Slavs but a Germanic race. Their genocides against Serbs, Jews, and Romani were thus expressions of Nazi racial ideology.[79] Adolf Hitler supported Pavelić in order to punish the Serbs.[80] Historian Michael Phayer explained that the Nazis’ decision to kill all of Europe's Jews is estimated by some to have begun in the latter half of 1941 in late June which, if correct, would mean that the genocide in Croatia began before the Nazi killing of Jews.[81] Jonathan Steinberg stated that the crimes against Serbs in the NDH were the “earliest total genocide to be attempted during the World War II”.[81]

Andrija Artuković, the Minister of Interior of the Independent State of Croatia, signed into law a number of racial laws.[82] On 30 April 1941, the government adopted “the legal order of races” and “the legal order of the protection of Atyan blood and the honor of Croatian people”.[82] Croats and about 750,000 Bosnian Muslims, whose support was needed against the Serbs, were proclaimed Aryans.[20] Donald Bloxham and Robert Gerwarth concluded that Serbs were primary target of racial laws and murders.[83] The Ustaše introduced the laws to strip Serbs of their citizenship, livelihoods, and possessions.[48] Similar to Jews in the Third Reich, Serbs were forced to wear armbands bearing the letter “P”, for Pravoslavac (Orthodox).[48][19] (Likewise, Jews were forced to wear the armband with the letter "Ž", fort Židov (Jew).[84] Ustaše writers adopted dehumanizing rhetoric.[85][86] In 1941, the usage of the Cyrillic script was banned,[87] and in June 1941 began the elimination of "Eastern" (Serbian) words from Croatian, as well as the shutting down of Serbian schools.[88] Ante Pavelić ordered, through the "Croatian state office for language", the creation of new words from old roots, and purged many Serbian words.[89]

Whereas the Ustaše persecution of Jews and Roma was systematic and represented an implementation of Nazi policies, their persecution of Serbs was rooted in a stronger "home grown" form of hatred, implemented with more variance due to the larger Serb population found across rural areas. This was done despite the fact it would degrade support for the regime, fueled Serb rebellion and jeopardized the stability of the NDH.[90] The level of violence enacted against Serb communities often depended more on the intercommunal relations and inclinations of the respective local Ustaše warlords than a well-structured policy.[90]

Concentration and extermination camps

The Ustaše set up temporary concentration camps in the spring of 1941 and laid the groundwork for a network of permanent camps in autumn.[6] The creation of concentration camps and extermination campaign of Serbs had been planned by the Ustaše leadership long before 1941.[52] In Ustaše state exhibits in Zagreb, the camps were portrayed as productive and "peaceful work camps", with photographs of smiling inmates.[91]

Serbs, Jews and Romani were arrested and sent to concentration camps such as Jasenovac, Stara Gradiška, Gospić and Jadovno. There were 22–26 camps in NDH in total.[92] Historian Jozo Tomasevich described that the Jadovno concentration camp itself acted as a "way station" en route to pits located on Mount Velebit, where inmates were executed and dumped.[93]

Approximately 90,000 of the Serb victims of genocide perished in concentration camps; the rest were killed in "direct terror", i.e. Punitive expeditions and razing of villages, pogroms, massacres and sporadic executions which mainly occurred between 1941 and 1942.[90]

The largest and most notorious camp was the Jasenovac-Stara Gradiška complex,[6] the largest extermination camp in the Balkans.[94] An estimated 100,000 inmates perished there, most Serbs.[95] Vjekoslav "Maks" Luburić, the commander-in-chief of all the Croatian camps, announced the great "efficiency" of the Jasenovac camp at a ceremony on 9 October 1942, and also boasted: "We have slaughtered here at Jasenovac more people than the Ottoman Empire was able to do during its occupation of Europe."[96]

Bounded by rivers and two barbed-wire fences making escape unlikely, the Jasenovac camp was divided into five camps, the first two closed in December 1941, while the rest were active until the end of the war. Stara Gradiška (Jasenovac V) held women and children. The Ciglana (brickyards, Jasenovac III) camp, the main killing ground and essentially a death camp, had 88% mortality rate, higher than Auschwitz's 84.6%.[97] A former brickyard, a furnace was engineered into a crematorium, with witness testimony of some, including children, being burnt alive and stench of human flesh spreading in the camp.[98] Luburić had a gas chamber built at Jasenovac V, where a considerable number of inmates were killed during a three-month experiment with sulfur dioxide and Zyklon B, but this method was abandoned due to poor construction.[99] Still, that method was unnecessary, as most inmates perished from starvation, disease (especially typhus), assaults with mallets, maces, axes, poison and knives.[99] The srbosjek ("Serb-cutter") was a glove with an attached curved blade designed to cut throats.[99] Large groups of people were regularly executed upon arrival outside camps and thrown into the river.[99] Unlike German-run camps, Jasenovac specialized in brutal one-on-one violence, such as guards attacking barracks with weapons and throwing the bodies in the trenches.[99] Some historians use a sentence from German sources: “Even German officers and SS men lost their cool when they saw (Ustaše) ways and methods.”[100]

The infamous camp commander Filipović, dubbed fra Sotona ("brother Satan") and the "personification of evil", on one occasion drowned Serb women and children by flooding a cellar.[99] Filipović and other camp commanders (such as Dinko Šakić and his wife Nada Šakić, the sister of Maks Luburić), used ingenious torture.[99] There were throat-cutting contests of Serbs, in which prison guards made bets among themselves as to who could slaughter the most inmates. It was reported that guard and former Franciscan priest Petar Brzica won a contest on 29 August 1942 after cutting the throats of 1,360 inmates.[101] Inmates were tied and hit over the head with mallets and half-alive hung in groups by the Granik ramp crane, their intestines and necks slashed, then dropped into the river.[102] When the Partisans and Allies closed in at the end of the war, the Ustaše began mass liquidations at Jasenovac, marching women and children to death, and shooting most of the remaining male inmates, then torched buildings and documents before fleeing.[103] Many prisoners were victims of rape, sexual mutilation and disembowelment, while induced cannibalism amongst the inmates also took place.[104][105][106][107][108] Some survivors testified about drinking blood from the slashed throats of the victims and soap making from human corpses.[109][106][108][110]

Children's concentration camps

The Independent State of Croatia was the only Axis satellite to have erected camps specifically for children.[6] Special camps for children were those at Sisak, Đakovo and Jastrebarsko,[111] while Stara Gradiška held thousands of children and women.[97] Historian Tomislav Dulić explained that the systematic murder of infants and children, who could not pose a threat to the state, serves as one important illustration of the genocidal character of Ustaša mass killing.[112]

The Holocaust and genocide survivors, including Božo Švarc, testified that Ustaše tore off the children's hands, as well as, “apply a liquid to children’s mouths with brushes”, which caused the children to scream and later die.[48] The Sisak camp commander, aphysician Antun Najžer, was dubbed the "Croatian Mengele" by survivors.[113]

Diana Budisavljević, a humanitarian of Austrian descent, carried out rescue operations and saved more than 15,000 children from Ustaše camps.[114][115]

List of concentration and death camps

- Jasenovac (I–IV) — around 100,000 inmates perished there, at least 52,000 Serbs

- Stara Gradiška (Jasenovac V) — more than 12,000 inmates lost their lives, mostly Serbs

- Gospić — between 24,000 and 42,000 inmates died, predominantly Serbs

- Jadovno — between 15,000 and 48,000 Serbs and Jews perished there

- Slana and Metajna — between 4,000 and 12,000 Serbs, Jews and communists died

- Sisak — 6,693 children passed through the camp, mostly Serbs, between 1,152 and 1,630 died

- Danica — around 5,000, mostly Serbs, were transported to the camp, some of them were executed

- Jastrebarsko — 3,336 Serb children passing through the camp, between 449 and 1,500 died

- Kruščica — around 5,000 Jews and Serbs were interred at the camp, while 3,000 lost their lives

- Đakovo — 3,800 Jewish and Serb women and children were interred at the camp, at least 569 died

- Lobor — more than 2,000 Jewish and Serb women and children were interred, at least 200 died

- Kerestinec — 111 Serbs, Jews and communists were captured, 85 were killed

- Sajmište — the camp at the NDH territory operated by the Einsatzgruppen and since May 1944 by Ustaše; between 20,000 and 23,000 Serbs, Jews, Roma and anti-fascists died here

- Hrvatska Mitrovica — the concentration camp in Sremska Mitrovica

Massacres

A large number of massacres were committed by the NDH armed forces, Croatian Home Guard (Domobrani) and Ustaše Militia.

The Ustaše Militia was organised in 1941 into five (later 15) 700-man battalions, two railway security battalions and the elite Black Legion and Poglavnik Bodyguard Battalion (later Brigade). They were predominantly recruited among the uneducated population and working class.

Besides ethnic Croats, the militia also contained Muslims where they accounted for an estimated 30% of the membership.[116]

Violence against Serbs began in April 1941 and was initially limited in scope, primarily targeting Serb intelligentsia. By July however, the violence became "indiscriminate, widespread and systematic". Massacres of Serbs were focused in mixed areas with large Serb populations for necessity and efficiency.[117]

In the summer of 1941, Ustaše militias and death squads burnt villages and killed thousands of civilian Serbs in the country-side in sadistic ways with various weapons and tools. Men, women, children were hacked to death, thrown alive into pits and down ravines, or set on fire in churches.[78] Hardly ever were firearms used, more commonly, knived axes and such were utilized. Serb victims were dismembered, their ears and tongues cut off and eyes gouged out.[118] Some Serb villages near Srebrenica and Ozren were wholly massacred while children were found impaled by stakes in villages between Vlasenica and Kladanj.[119] The Ustaše cruelty and sadism shocked even Nazi commanders.[120] A Gestapo report to Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler, dated 17 February 1942, stated:

Increased activity of the bands [of rebels] is chiefly due to atrocities carried out by Ustaše units in Croatia against the Orthodox population. The Ustaše committed their deeds in a bestial manner not only against males of conscript age, but especially against helpless old people, women and children. The number of the Orthodox that the Croats have massacred and sadistically tortured to death is about three hundred thousand.[121]

The Ustaše's preference for cold weapons in carrying out their deeds was partly a result of the shortage of ammunition and firearms in the early course of the war, but also demonstrated the importance the regime placed on the cult of violence and personal slaughter, in particular through the usage of the knife.[122]

Charles King emphasized that concentration camps are losing their central place in Holocaust and genocide research because a large proportion of victims perished in mass executions, ravines and pits.[123] He explained that the actions of the German allies, including the Croatian one, and the town- and village-level elimination of minorities also played a significant role.[123]

Central Croatia

On 28 April 1941, approximately 184–196 Serbs from Bjelovar were summarily executed, after arrest orders by Kvaternik. It was the first act of mass murder committed by the Ustaše upon coming to power, and presaged the wider campaign of genocide against Serbs in the NDH that lasted until the end of the war. A few days following the massacre of Bjelovar Serbs, the Ustaše rounded up 331 Serbs in the village of Otočac. The victims were forced to dig their own graves before being hacked to death with axes. Among the victims was the local Orthodox priest and his son. The former was made to recite prayers for the dying as his son was killed. The priest was then tortured, his hair and beard was pulled out, eyes gouged out before he was skinned alive.[124]

On 24–25 July 1941, the Ustaše militia captured the village of Banski Grabovac in the Banija region and murdered the entire Serb population of 1,100 peasants. On 24 July, over 800 Serb civilians were killed in the village of Vlahović.[117]

Between 29 June and 7 July 1941, 280 Serbs were killed and thrown into pits near Kostajnica.[125] Large scale massacres took place in Staro Selo Topusko, including in the village of Pecka with 250 victims,[126] and Perna where 427 old men and children were killed.[127] A large number were also killed in Vojišnica[128] and Vrginmost.[129] About 60% of Sadilovac residents lost their lives during the war.[130] More than 400 Serbs were killed in their homes, including 185 children.[130] On 17 April 1942, 99 Serbs were burned alive in the village of Kolarić, near Vojnić.[131] A total of 3,849 inhabitants of the town of Vojnić were massacred during the war, out of a total of approximately 5000 inhabitants.[127] That same month, a total of 759 women, children and elderly Serbs were massacred near the village of Krstinja.[127] On 31 July 1942, in the Sadilovac church the Ustaše under Milan Mesić's command massacred more than 580 inhabitants of the surrounding villages, including about 270 children.[132] At various dates, 2,019 primarily women and children were killed in the village of Rakovica.[127]

Glina

On 11 or 12 May 1941, 260–300 Serbs were herded into an Orthodox church and shot, after which it was set on fire. The idea for this massacre reportedly came from Mirko Puk, who was the Minister of Justice for the NDH.[133] On 10 May, Ivica Šarić, a specialist for such operations traveled to the town of Glina to meet with local Ustaše leadership where they drew up a list of names of all the Serbs between sixteen and sixty years of age to be arrested.[134] After much discussion, they decided that all of the arrested should be killed.[135] Many of the town's Serbs heard rumors that something bad was in store for them but the vast majority did not flee. On the night of 11 May, mass arrests of male Serbs over the age of sixteen began.[135] The Ustaše then herded the group into an Orthodox Church and demanded that they be given documents proving the Serbs had all converted to Catholicism. Serbs who did not possess conversion certificates were locked inside and massacred.[124] The church was then set on fire, leaving the bodies to burn as Ustaše stood outside to shoot any survivors attempting to escape the flames.[136]

A similar massacre of Serbs occurred on 30 July 1941. 700 Serbs were gathered into a church under the premise that they would be converted. Victims were killed by having their throats cut or by having their heads smashed in with rifle butts. Between 500 and 2000 other Serbs were later massacred in neighbouring villages by Vjekoslav "Maks" Luburić's forces, continuing until 3 August. In these massacres specifically males 16 years and older were killed.[137] Only one of the victims, Ljubo Jednak, survived by playing dead.

Lika

The district of Gospić experienced the first large-scale massacres which occurred in the Lika region, as some 3,000 Serb civilians were killed between late July and early August 1941.[117] Ustaše officials reported an emerging Serb rebellion due to massacres. In late July 1941, a detachment of the Croatian military in Gospić noted that the local insurgents were Serb peasants who had fled to the woods "purely as a reaction to the cleansing [operations] against them by our Ustaša formations". Following a sabotage of railway tracks in the district of Vojnić that was attributed to local communists on 27 July 1941, the Ustaše began a "cleansing" operation of indiscriminate pillage and killing of civilians, including the elderly and children.[117]

On 6 August 1941, the Ustaše killed and burned more than 280 villagers in Mlakva, including 191 children.[138] Between June and August 1941, about 890 Serbs from Ličko Petrovo Selo and Melinovac were killed and thrown in the so-called Delić pit.[139]

During the war, the Ustaše massacred more than 900 Serbs in Divoselo, more than 500 in Smiljan, as well as more than 400 in Široka Kula near Gospić.[140] On 2 August 1941, the Ustaše trapped about 120 children and women and 50 men who tried to escape from Divoselo. After a few days of imprisonment, where women were raped, they were stabbed in groups and thrown into the pits.[141]

Slavonia

On 21 December 1941, approximately 880 Serbs from Dugo Selo Lasinjsko and Prkos Lasinjski were killed in the Brezje forest.[142] On the Serbian New Year, 14 January 1942, the biggest slaughter of the civilians from Slavonia started. Villages were burned, and about 350 people were deported to Voćin and executed.[143]

Syrmia

In August 1942, following the joint military anti-partisan operation in the Syrmia by the Ustaše and German Wehrmacht, it turned into a massacre by the Ustaše militia that left up to 7,000 Serbs dead.[144] Among those killed was the prominent painter Sava Šumanović, who was arrested along with 150 residents of Šid, and then tortured by having his arms cut off.[145]

Bosnian Krajina

In August 1941 on the Eastern Orthodox Elijah's holy day, who is the patron saint of Bosnia and Herzegovina, between 2,800 and 5,500 Serbs from Sanski Most and the surrounding area were killed and thrown into pits which have been dug by victims themselves.[146]

During the war, the NDH armed forces killed over 7,000 Serbs in the municipality of Kozarska Dubica, while the municipality lost more than half of its pre-war population.[147] The biggest massacre was committed by the Croatian Home Guard in January 1942, when the village Draksenić was burned and more than 200 were people killed.[148]

In February 1942, the Ustaše under Miroslav Filipović's command massacred 2,300 adults and 550 children in Serb-populated villages Drakulić, Motike and Šargovac.[149] The children were chosen as the first victims and their body parts were cut off.[149]

Garavice

From July to September 1941, thousands of Serbs were massacred along with some Jews and Roma victims at Garavice, an extermination location near Bihać. On the night of 17 June 1941, Ustaše began the mass killing of previously captured Serbs, who were brought by trucks from the surrounding towns to Garavice.[150] The bodies of the victims were thrown into mass graves. A large amount of blood contaminated the local water supply.[151]

Herzegovina

On 9 May 1941, approximately 400 Serbs were rounded up from several villages and executed in a pit behind a school in the village of Blagaj.[152] On 31 May, between 120 and 270 Serbs were rounded up near Trebinje and executed.[153]

On 2 June 1941, Ustaše authorities led by Herman Tongl in the municipality of Gacko issued an order to the Serb inhabitants of the villages of Korita and Zagradci demanding that all males above the age of fifteen report to a building in the village of Stepen. Once there, they were imprisoned for two days and on 4 June, the prisoners who numbered about 170 were tied together in groups of two or three, loaded onto a lorry and driven to the Golubnjača limestone pit near Kobilja Glava where they were shot, beaten with poles, cudgels, axes and picks and thrown into the pit.[154] On June 22, under the ruse that Serbs were planning to launch an offensive prior to the Vidovdan holiday, Tongl enlisted locals to massacre Serb farmers in four districts. The victims included women who were raped as well as children; some were thrown into pits while others were taken near the Neretva river and executed there.[155] On June 23, 80 people from three villages near Gacko were killed.[156]

On 2 June 1941, the Ustaše killed 140 peasants near the town of Ljubinje and on 23 June killed an additional 160. In the municipality of Stolac, nearly 260 were killed during the course of two days.[156]

In the Livno Field area, the Ustaše killed over 1,200 Serbs including 370 children.[157] In the Koprivnica Forest near Livno, around 300 citizen were tortured and killed.[157] About 300 children, women and the elderly were killed and thrown into the Ravni Dolac pit in Donji Rujani.[158]

From 4–6 August 1941, 650 women and children killed by being thrown into the Golubinka pit near Šurmanci.[48][159] Also, hand grenades were thrown at dead bodies.[159] Some 4000 Serbs were later massacred in neighbouring places during that summer.[48]

Drina Valley

Some 70-200 Serbs massacred by Muslim Ustaše forces in Rašića Gaj, Vlasenica in Bosnia and Herzegovina between 22 June and 20 July 1941, after raping women and girls.[160] Many Serbs were executed by Ustaše along the Drina Valley for a months, especially near Višegrad.[48] Jure Francetić's Black Legion killed thousands of defenceless Bosnian Serb civilians and threw their bodies into the Drina river.[161] In 1942, about 6,000 Serbs were killed in Stari Brod near Rogatica and Miloševići.[162][163]

Sarajevo

During the summer of 1941, Ustaše militia periodically interned and executed groups of Sarajevo Serbs.[164] In August 1941, they arrested about one hundred Serbs suspected of ties to the resistance armies, mostly church officials and members of the intelligentsia, and executed them or deported them to concentration camps.[164] The Ustaše killed at least 323 people in the Villa Luburić, a slaughter house and place for torturing and imprisoning Serbs, Jews and political dissidents.[165]

Expulsion and ethnic cleansing

Expulsions was one of the pillar of the Ustaše plan to create a pure Croat state.[48] The first to be forced to leave were war veterans from the World War I Macedonian front who lived in Slavonia and Syrmia.[48][166] By mid-1941, 5,000 Serbs had been expelled to German-occupied Serbia.[48] The general plan was to have prominent people deported first, so their property could be nationalized and the remaining Serbs could then be more easily manipulated. By the end of September 1941, about half of the Serbian Orthodox clergy, 335 priests, had been expelled.[167]

The Drina is the border between the East and West. God’s Providence placed us to defend our border, which our allies are well aware and value, because for centuries we have proven that we are good frontiersmen.[48]

— Mile Budak, the minister of the NDH government, August 1941.

Advocates of expulsion presented it as a necessary measure for the creation of a socially functional nation state, and also rationalized these plans by comparing it with the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey.[168] The Ustaše set up holding camps, with the aim of gathering a large number of people and deporting them.[48] The NDH government also formed the Office of Colonization to resettle Croats on reclaimed land.[48] During the summer of 1941, the expulsions were carried out with the significant participation of the local population.[169] Many representatives of local elites, including Bosnian Muslims in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Germans in Slavonia and Syrmia, played an active role in the expulsion.[170]

An estimated 120,000 Serbs were deported from the NDH to German-occupied Serbia, and 300,000 fled by 1943.[2] By the end of July 1941 according to the German authorities in Serbia, 180,000 Serbs defected from the NDH to Serbia and by the end of September that number exceeded 200,000. In that same period 14,733 persons were legally relocated from the NDH to Serbia.[166] In turn, the NDH had to accept more than 200,000 Slovenian refugees who were forcefully evicted from their homes as part of the German plan of annexing parts of the Slovenian territories. In October 1941, organized migration was stopped because the German authorities in Serbia forbid further immigration of Serbs. According to documentation of the Commissariat for Refugees and Immigrants in Belgrade, in 1942 and 1943 illegal departures of individuals from NDH to Serbia still existed, numbering an estimated 200,000 though these figures are incomplete.[166]

Religious persecution

The Ustaše viewed religion and nationality as being closely linked; while Roman Catholicism and Islam (Bosnian Muslims were viewed as Croats) were recognized as Croatian national religions, Eastern Orthodoxy was deemed inherently incompatible with the Croatian state project.[34] They saw Orthodoxy as hostile because it was identified as Serb[171] (prior to 1920, the Orthodox dioceses in most of Croatian lands belonged to an independent Patriarchate of Karlovci). To a certain extent, the campaign of terror could be seen as similar Crusades of medieval ages; a religious crusade.[84] On 3 May 1941, a law was passed on religious conversions, pressuring Serbs to convert to Catholicism and thereby adopt Croat identity.[34] This was made on the eve of Pavelić's meeting with Pope Pius XII in Rome.[172] The Catholic Church in Croatia, headed by archbishop Aloysius Stepinac, greeted it and adopted it into the Church's internal law.[172] The term "Serbian Orthodox" was banned in mid-May as being incompatible with state order, and the term "Greek-Eastern faith" was used in its place.[173] By the end of September 1941, about half of the Serbian Orthodox clergy, 335 priests, had been expelled.[167]

To erase all history of Serbs and the Orthodox religion, churches (some of which dated to 1200s and 1300s) were razed to the ground or denigrated by using them as stables or barns etc.[118]

The Ustaša movement is based on religion. Therefore, our acts stem from our devotion to religion and the Roman Catholic church.

— the chief Ustaše ideologist Mile Budak, 13 July 1941.[174]

Ustaše propaganda legitimized the persecution as being partially based on the historic Catholic–Orthodox struggle for domination in Europe and Catholic intolerance towards the "schismatics".[171] Following the start of Serb insurgency (July 1941), the State Directorate for Regeneration in the autumn of 1941 launched a program aimed at the mass forced conversion of the Serbs.[171] Already in the summer, the Ustaše had closed or destroyed most of the Serbian Orthodox churches and monasteries and deported, imprisoned or murdered Orthodox priests and bishops.[171] Over 150 Serbian Orthodox priests were also killed between May and December 1941.[175] The conversions were meant to Croatianize and permanently destroy the Serbian Orthodox Church.[171] Roman Catholic priest Krunoslav Draganović argued that many Catholics were converted to Orthodoxy during the 16th and 17th centuries, which was later used as the basis for the Ustaše conversion program.[176][177]

The conversion policy had a particular aspect: only uneducated Serbs were eligible for conversion, since illiterate peasants were presumed to have less of a Serb/Orthodox identity. People with secondary education etc. (and especially Orthodox clergy) were not eligible. Educated people were singled out for expulsion or extermination, states Robert B. McCormick.[178]

The Vatican was not opposed to the forced conversions. On 6 February 1942, Pope Pius XII privately received 206 Ustaše members in uniforms and blessed them, symbolically supporting their actions.[179] On 8 February 1942, the envoy to the Holy See, Nikola Rusinović, said that 'the Holy See rejoiced' at forced conversions.[180] In a 21 February 1942 letter to Cardinal Luigi Maglione, the Holy See's secretary encouraged the Croatian bishops to speed up the conversions, and he also stated that the term "Orthodox" should be replaced with the terms "apostates or schismatics".[181] Many fanatical Catholic priests joined the Ustaše, blessed and supported their work, and participated in killings and conversions.[182]

In 1941–1942,[183] some 200,000[184] or 240,000[185]–250,000[186] Serbs were converted to Roman Catholicism, although most of them only practiced it temporarily.[184] Converts would sometimes be killed anyway, often in the same churches where they were re-baptized.[184] 85% of the Serbian Orthodox clergy was killed or expelled.[187] In Lika, Kordun and Banija alone, 172 Serbian Orthodox churches were closed, destroyed, or plundered.[173]

The Encyclopedia of the Holocaust described that the bishops' conference that met in Zagreb in November 1941 was not prepared to denounce the forced conversion of Serbs that had taken place in the summer of 1941, let alone condemn the persecution and murder of Serbs and Jews.[188] Many Catholic priests in Croatia approved of and supported the Ustaše's large scale attacks on the Serbian Orthodox Church,[189] and the Catholic hierarchy did not issue any condemnation of the crimes, either publicly or privately.[190] The Croatian Catholic Church and the Vatican viewed the Ustaše's policies against the Serbs as being advantageous to Roman Catholicism.[191]

The puppet "Croatian Orthodox Church"

After the matter of forced conversion had become extremely controversial,[34] the NDH government on 3 April 1942 adopted a law that established the Croatian Eastern Orthodox Church.[192] This was done in order to replace the institutions of the Serbian Orthodox Church.[193] According to the "Statute concerning the Croatian Eastern Orthodox Church" that was approved on 5 June, the Church was "indivisible in its unity and autocephalous".[192] In June, White Russian émigré Germogen Maximov, an archbishop of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, was enthroned as its primate.[194] The establishment of the Church was done in order to try and pacify the state as well as to Croatisize the remaining Serb population once the Ustaše realized that the complete eradication of Serbs in the NDH was unattainable. Persecution of Serbs continued however, but was less intense.[195]

Persecution of Serbian Orthodox clergy

Bishops of the Serbian Orthodox Church dioceses in the Independent State of Croatia were targeted during religious persecutions.[196] On 5 May 1941, the Ustaše tortured and killed Platon Jovanović of Banja Luka. On 12 May, Bishop Petar Zimonjić, Metropolitan of the Eparchy of Dabar-Bosna, was killed and in mid-August Bishop Sava Trlajić was killed.[175] Dositej Vasić, the Metropolitan of the Metropolitanate of Zagreb and Ljubljana died in 1945 as result of wounds from torture by Ustaše. Nikola Jovanović, the Bishop of the Eparchy of Zahumlje and Herzegovina died in 1944, after he was beaten by the Ustaše and expelled to Serbia. Irinej Đorđević, the Bishop of the Eparchy of Dalmatia was interned to Italian captivity.[196] There were 577 Serbian Orthodox priests, monks and other religious dignitaries in the NDH in April 1941. By December, there were none left. Between 214 and 217 were killed, 334 were exiled, eighteen fled and five died of natural causes.[196] In Bosnia and Herzegovina, 71 Orthodox priests were killed by the Ustaše during WWII, 10 by the Partisans, 5 by the Germans, and 45 died in the first decade after the end of WWII.[197]

According to Serb Orthodox Church data, out of approximately 700 clergymen and monks of the NDH territory, 577 were subjected to persecution, out of these 217 were killed, 334 were deported to Serbia, 3 were arrested, 18 managed to escape and 5 died (later) from consequences of torture.[198]

The role of Aloysius Stepinac

A cardinal Aloysius Stepinac served as Archbishop of Zagreb during World War II and pledged his loyalty to the NDH. Scholars still debate the degree of Stepinac's contact with the Ustaše regime.[48] Mark Biondich stated that he was not an “ardent supporter” of the Ustahsa regime legitimising their every policy, nor an “avowed opponent” publicly denounced its crimes in a systematic manner.[199] While some clergy committed war crimes in the name of the Catholic Church, Stepinac practiced a wary ambivalence.[200][48] He was an early supporter of the goal of creating a Catholic Croatia, but soon began to question the regime's mandate of forced conversion.[48]

Historian Tomasevich praised his statements that were made against the Ustaše regime by Stepinac, as well as his actions against the regime. However, he also noted that these same statements and actions had shortcomings in respect to Ustaše's genocidal actions against the Serbs and the Serbian Orthodox Church. As Stepinac failed to publicly condemn the genocide waged against the Serbs by the Ustaše earlier during the war as he would later on. Tomasevich stated that Stepinac's courage against the Ustaše state earned him great admiration among anti-Ustaše Croats in his flock along with many others. However this came with the price of enmity of the Ustaše and Pavelić personally. In the early part of the war, he strongly supported a Yugoslavian state organized with federal lines. It was generally known that Stepinac and Pavelić thoroughly hated each other. [201] The Germans considered him Pro-Western and “friend of the Jews” leading to hostility from German and Italian forces. [202]

On 14 May 1941, Stepinac received word of an Ustaše massacre of Serb villagers at Glina. On the same day, he wrote to Pavelić saying:[203]

I consider it my bishop's responsibility to raise my voice and to say that this is not permitted according to Catholic teaching, which is why I ask that you undertake the most urgent measures on the entire territory of the Independent State of Croatia, so that not a single Serb is killed unless it is shown that he committed a crime warranting death. Otherwise, we will not be able to count on the blessing of heaven, without which we must perish.

These were still private protest letters. Later in 1942 and 1943, Stepinac started to speak out more openly against the Ustaše genocides, this was after most of the genocides were already committed, and it became increasingly clear the Nazis and Ustaše will be defeated.[204] In May 1942, Stepinac spoke out against genocide, mentioning Jews and Roma, but not Serbs.[48]

Tomasevich wrote that while Stepinac is to be commended for his actions against the regime, the failure of the Croatian Catholic hierarchy and Vatican to publicly condemn the genocide "cannot be defended from the standpoint of humanity, justice and common decency".[205] In his diary, Stepinac said that "Serbs and Croats are of two different worlds, north and south pole, which will never unite as long as one of them is alive", along with other similar views.[206] Historian Ivo Goldstein described that Stepinac was being sympathetic to the Ustaše authorities and ambivalent towards the new racial laws, as well as that he was “a man with many dilemmas in a disturbing time”.[207] Stepinac resented the interwar conversion of some 200,000 mostly Croatian Catholics to Orthodoxy, which he felt was forced on them by prevailing political conditions. [205] In 2016 Croatia's rehabilitation of Stepinac was negatively received in Serbia and Republika Srpska, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[208]

Toll of victims and genocide classification

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website states that "Determining the number of victims for Yugoslavia, for Croatia, and for Jasenovac is highly problematic, due to the destruction of many relevant documents, the long-term inaccessibility to independent scholars of those documents that survived, and the ideological agendas of postwar partisan scholarship and journalism".[209]

In the 1980s, calculations of World War II victims in Yugoslavia were made by the Serb statistician Bogoljub Kočović and the Croat demographer Vladimir Žerjavić. Tomasevich described their studies as being objective and reliable.[210] Kočović estimated that 370,000 Serbs, both combatants and civilians, died in the NDH during the war. With a possible error of around 10%, he noted that Serb losses cannot be higher than 410,000.[211] He did not estimate the number of Serbs who were killed by the Ustaše, saying that in most cases, the task of categorizing the victims would be impossible.[212] Žerjavić estimated that the total number of Serb deaths in the NDH was 322,000, of which 125,000 died as combatants, while 197,000 were civilians. Žerjavić estimated that a total of 78,000 civilians were killed in Ustaše prisons, pits and camps, including Jasenovac, 45,000 civilians were killed by the Germans, 15,000 civilians were killed by the Italians, 34,000 civilians were killed in battles between the warring parties, and 25,000 civilians died of typhoid.[213] The number of victims who perished in the Jasenovac concentration camp remains a matter of debate, but current estimates put the total number at around 100,000, about half of whom were Serbs.[95]

During the war as well as during Tito's Yugoslavia, various numbers were given for Yugoslavia's overall war casualties.[a] Estimates by Holocaust memorial centers also vary.[b] The historian Jozo Tomasevich said that the exact number of victims in Yugoslavia is impossible to determine.[214] The academic Barbara Jelavich however cites Tomasevich's estimate in writing that as many as 350,000 Serbs were killed during the period of Ustaše rule.[215] The historian Rory Yeomans said that the most conservative estimates state that 200,000 Serbs were killed by Ustaše death squads but the actual number of Serbs who were executed by the Ustaše or perished in Ustaše concentration camps may be as high as 500,000.[6] In a 1992 work, Sabrina P. Ramet cites the figure of 350,000 Serbs who were "liquidated" by "Pavelić and his Ustaše henchmen".[216] In a 2006 work, Ramet estimated that at least 300,000 Serbs were "massacred by the Ustaše".[2] In her 2007 book "The Independent State of Croatia 1941-45", Ramet cites Žerjavić's overall figures for Serb losses in the NDH.[217] Marko Attila Hoare writes that "perhaps nearly 300,000 Serbs" died as a result of the Ustaše genocide and the Nazi policies.[218]

Tomislav Dulić stated that Serbs in NDH suffered among the highest casualty rates in Europe during the World War II.[112] American historian Stanley G. Payne stated that direct and indirect executions by NDH regime were an “extraordinary mass crime”, which in proportionate terms exceeded any other European regime beside Hitler's Third Reich.[219] He added the crimes in the NDH were proportionately surpassed only by the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia and several of the extremely genocidal African regimes.[219] Raphael Israeli wrote that “a large scale genocidal operations, in proportions to its small population, remain almost unique in the annals of wartime Europe.”[70]

In Serbia as well as in the eyes of Serbs, the Ustaše atrocities constituted a genocide.[220] Many historians and authors describe the Ustaše regime's mass killings of Serbs as meeting the definition of genocide, including Raphael Lemkin who is known for coining the word genocide and initiating the Genocide Convention.[221][222][223][224] Croatian historian Mirjana Kasapović explained that in the most important scientific works on genocide, crimes against Serbs, Jews and Roma in the NDH are unequivocally classified as genocide.[225]

Yad Vashem, Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, stated that “Ustasha carried out a Serb genocide, exterminating over500,000, expelling 250,000, and forcing another 250,000 to convert to Catholicism”.[226][227] The Simon Wiesenthal Center, also, mentioned that leaders of the Independent State of Croatia committed genocide against Serbs, Jews, and Roma.[228] Presidents of Croatia, Stjepan Mesić and Ivo Josipović, as well as Bakir Izetbegović and Željko Komšić, Bosniak and Croat member of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, also described the persecution of Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia as a genocide.[229][230][231][232]

In the post-war era, the Serbian Orthodox Church considered the Serbian victims of this genocide to be martys. As a result, the Serbian Orthodox Church commemorates the Saint Martyrs of Jasenovac on 13 September.[233]

Aftermath

The Yugoslav communist authorities did not use the Jasenovac camp as was done with other European concentration camps, most likely due to Serb-Croat relations. They recognized that ethnic tensions stemming from the war could have had the capacity to destabilize the new communist regime, and subsequently tried to conceal wartime atrocities and mask specific ethnic losses.[19] The Tito's government attempted to let the wounds heal and forge "brotherhood and unity" in the peoples.[234] Tito himself was invited to, and passed Jasenovac several times, but never visited the site.[235] The genocide was not properly examined in the aftermath of the war, because the Yugoslav communist government did not encourage independent scholars.[209][236][237][238] Historians Marko Attila Hoare and Mark Biondich stated that Western world historians don't pay enough attention to the genocide committed by Ustaše, while several scholars described it as lesser-known genocide.[48][239][225]

World War II and especially its ethnic conflicts have been deemed instrumental in the later Yugoslav Wars (1991–95).[240]

Trials

Mile Budak and a number of other members of the NDH government, such as Nikola Mandić and Julije Makanec, were tried and convicted of high treason and war crimes by the communist authorities of the SFR Yugoslavia. Many of them were executed.[241][242] Miroslav Filipović, the commandant of the Jasenovac and Stara Gradiška camps, was found guilty for war crimes, sentenced to death and hanged.[243]

Many others escaped, including the supreme leader Ante Pavelić, most to Latin America. Some emigrations were prevented by the Operation Gvardijan, in which Ljubo Miloš, the commandant of the Jasenovac camp was captured and executed.[244] Aloysius Stepinac, who served as Archbishop of Zagreb was found guilty of high treason and forced conversion of Orthodox Serbs to Catholicism.[245] However, some claim the trial was "carried out with proper legal procedure".[245]

In its judgment in the Hostages Trial, the Nuremberg Military Tribunal concluded that the Independent State of Croatia was not a sovereign entity capable of acting independently of the German military, despite recognition as an independent state by the Axis powers.[246] According to the Tribunal, "Croatia was at all times here involved an occupied country".[246] The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide were not in force at the time. It was unanimously adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 9 December 1948 and entered into force on 12 January 1951.[247][248]

Andrija Artuković, Minister of Internal Affairs and Minister of Justice of the NDH who signed a number of racial laws, escaped to the United States after the war and he was extradited to Yugoslavia in 1986, where he was tried in the Zagreb District Court and was found guilty of a number of mass killings in the NDH.[249] Artuković was sentenced to death, but the sentence was not carried out due to his age and health.[250] Efraim Zuroff, a Nazi hunter, played a significant role in capturing Dinko Šakić, another Jasenovac camp commander, during 1990s.[251] After pressure from the international community on the right-wing president Franjo Tuđman, he sought Šakić's extradition and he stood trial in Croatia, aged 78; he was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity and given the maximum sentence of 20 years imprisonment. According to the human rights researchers Eric Stover, Victor Peskin and Alexa Koenig it was "the most important post-Cold War domestic effort to hold criminally accountable a Nazi war crimes suspect in a former Eastern European communist country".[251]

Ratlines, terrorism and assassinations

With the Partisan liberation of Yugoslavia, many Ustaše leaders fled and took refuge at the college of San Girolamo degli Illirici near the Vatican.[103] Catholic priest and Ustaše Krunoslav Draganović directed the fugitives from San Girolamo.[103] The US State Department and Counter-Intelligence Corps helped war criminals to escape, and assisted Draganović (who later worked for the American intelligence) in sending Ustaše abroad.[103] Many of those responsible for mass killings in NDH took refuge in South America, Portugal, Spain and the United States.[103] Luburić was assassinated in Spain in 1969 by an UDBA agent; Artuković lived in Ireland and California until extradited in 1986 and died of natural causes in prison; Dinko Šakić and his wife Nada lived in Argentina until extradited in 1998, Dinko dying in prison and his wife released.[103] Draganović also arranged Gestapo functionary Klaus Barbie's flight.[103]

Among some of the Croat diaspora, the Ustaše became heroes.[103] Ustaše émigré terrorist groups in the diaspora (such as Croatian Revolutionary Brotherhood and Croatian National Resistance) carried out assassinations and bombings, and also plane hijackings, throughout the Yugoslav period.[252]

Controversy and denial

Historical negationism

Some Croats, including politicians, have attempted to minimise the magnitude of the genocide perpetrated against Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia.[253] Historian Mirjana Kasapović concluded that there are three main strategies of historical revisionism in the part of Croatian historiography: the NDH was a normal counter-insurgency state at the time; no mass crimes were committed in the NDH, especially genocide; the Jasenovac camp was just a labor camp, not an extermination camp.[225]

By 1989, the future President of Croatia, Franjo Tuđman had embraced Croatian nationalism and published Horrors of War: Historical Reality and Philosophy, in which he questioned the official number of victims killed by the Ustaše during the Second World War. In his book,Tuđman claimed that between 30,000 and 40,000 died at Jasenovac.[254] Some scholars and observers accused Tuđman of racist statements, “flirting with ideas associated with the Ustaše movement”, appointment of former Ustaše officials to political and military positions, as well as downplaying the number of victims in the Independent State of Croatia.[255][256][257][258][259]

Since 2016, anti-fascist groups, leaders of Croatia's Serb, Roma and Jewish communities and former top Croat officials have boycotted the official state commemoration for the victims of the Jasenovac concentration camp because, as they said, Croatian authorities refused to denounce the Ustaše legacy explicitly and they downplayed and revitalized crimes committed by Ustaše.[260][261][262][263]

Destruction of memorials

After Croatia gained independence, about 3,000 monuments dedicated to the anti-fascist resistance and the victims of fascism were destroyed.[264][265][266] According to Croatian World War II veterans' association, these destructions were not spontaneous, but a planned activity carried out by the ruling party, the state and the church.[264] The status of the Jasenovac Memorial Site was downgraded to the nature park, and parliament cut its funding.[267] In September 1991, Croatian forces entered the memorial site and vandalized the museum building, while exhibitions and documentation were destroyed, damaged and looted.[265] In 1992, FR Yugoslavia sent a formal protest to the United Nations and UNESCO, warning of the devastation of the memorial complex.[265] The European Community Monitor Mission visited the memorial center and confirmed the damage.[265]

Commemoration

Israeli President Moshe Katsav visited Jasenovac in 2003. His successor, Shimon Peres, paid homage to the camp's victims when he visited Jasenovac on 25 July 2010 and laid a wreath at the memorial. Peres dubbed the Ustaše's crimes a "demonstration of sheer sadism".[268][269]

The Jasenovac Memorial Museum reopened in November 2006 with a new exhibition designed by a Croatian architect, Helena Paver Njirić, and an Educational Center, designed by the firm Produkcija. The Memorial Museum features an interior of rubber-clad steel modules, video and projection screens, and glass cases displaying artifacts from the camp. Above the exhibition space, which is quite dark, is a field of glass panels inscribed with the names of the victims.

Департамент парков Нью-Йорка , Комитет парков Холокоста и Исследовательский институт Ясеноваца при помощи тогдашнего конгрессмена Энтони Вайнера (демократ от Нью-Йорка) установили общественный памятник жертвам Ясеноваца в апреле 2005 года (шестидесятая годовщина событий в Ясеноваце). освобождение лагерей.) На церемонии открытия присутствовали десять югославских людей, переживших Холокост, а также дипломаты из Сербии, Боснии и Израиля. Он остается единственным общественным памятником жертвам Ясеноваца за пределами Балкан.

Сегодня, 22 апреля , в годовщину побега узников из лагеря Ясеновац, Сербия отмечает День памяти жертв национального Холокоста, геноцида Второй мировой войны и других фашистских преступлений , а Хорватия проводит официальные поминки на мемориальном комплексе Ясеновац. [270] Сербия и боснийское образование Республика Сербская проводят совместные центральные поминки в мемориальной зоне Дони Градина . [271]

прошла выставка «Ясеновац – право на память» В 2018 году в штаб-квартире Организации Объединенных Наций в Нью-Йорке в рамках празднования Международного дня памяти жертв Холокоста , основная цель которой – способствовать развитию культуры памяти сербов. Евреи, цыгане и антифашисты, ставшие жертвами Холокоста и геноцида в лагере Ясеновац. [272] [273] 22 апреля 2020 года президент Сербии Александр Вучич посетил с официальным визитом мемориальный парк в Сремска-Митровице , посвященный жертвам геноцида на территории Сирмии . [274]

Церемонии поминовения жертв концентрационного лагеря Ядовно организуются Сербским национальным советом (СНВ), еврейской общиной Хорватии и местными антифашистами с 2009 года, а 24 июня объявлено «Днем памяти Лагерь Ядовно» в Хорватии. [271] 26 августа 2010 года, в 68-ю годовщину частичного освобождения детского лагеря Ястребарско , память жертв была отмечена на церемонии у памятника на Ястребарском кладбище. На нем присутствовало всего 40 человек, в основном члены Союза антифашистов и антифашистов Республики Хорватия. [275] Правительство Республики Сербской проводит поминки на мемориальном месте жертв усташской резни в долине реки Дрина . [163]

В культуре

Литература

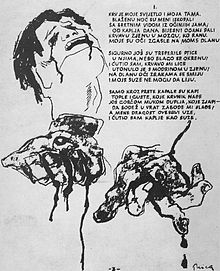

- Джама , стихотворение, осуждающее преступления усташей, написанное Иваном Гораном Ковачичем.

- Орлы рано летят , роман о роли детей в помощи партизанам в сопротивлении усташам, автор Бранко Чопич.

- Концентрационный лагерь на Саве , рассказ Ильи Яковлевича

Искусство

- Златко Прица и Эдо Муртич иллюстрировали сцены из стихотворения Ивана Горана Ковачича «Яма».

Театр

- Голубняча , пьеса Йована Радуловича об этнических отношениях в соседних деревнях в годы после преступлений усташей. [276]

Фильмы

- 1955 — «Шолай» , фильм о сербском восстании против геноцида, режиссёр Воислав Нанович.

- 1960 — «Девятый круг» , фильм режиссёра Франса Штиглича , включает сцены из лагеря Ясеновац.

- 1966 — «Орлы рано летят» , фильм по одноименному роману режиссёра Сои Йованович.

- 1967 — «Чёрные птицы» , фильм о группе узников концлагеря Стара Градишка, режиссёр Эдуард Галич.

- 1984 - Конец войны , фильм о сербе, в котором его сын ищет и убивает членов усташской милиции, которые пытали и убили его жену и мать, режиссер Драган Кресоя.

- 1988 - « Брача по матери» , фильм о зверствах усташей, рассказанный через историю двух сводных братьев, хорвата и серба, режиссер Здравко Шотра.

- 2016 — Первая треть — «Прощение как наказание» , короткометражный художественный фильм о расправах Жиле Фриганович, режиссёр Светлана Петрова.

- 2019 — «Дневник Дианы Б.» , биографический фильм об операции Дианы Будисавлевич по спасению более 10 000 детей из концлагерей, режиссёр Дана Будисавлевич.

- 2020 — «Дара из Ясеноваца» , фильм о девушке, пережившей лагерь Ясеновац, режиссёр Предраг Антониевич.

Сериал

- 1981 - Nepokoreni grad , сериал о террористической кампании усташей, включая лагерь Керестинец, режиссеры Ванча Клякович и Эдуард Галич.

Музыка

- Некоторые выжившие утверждают, что слова знаменитой песни « Журджевдан » были написаны в поезде, который вез заключенных из Сараево в лагерь Ясеновац. [277]

- Thompson , хорватская рок-группа, вызвала споры из-за предполагаемого прославления режима усташей в своих песнях и концертах, и самая известная из таких песен - « Jasenovac i Gradiška Stara ». [278] [279]

См. также

Аннотации

- ^ Во время войны немецкие военачальники приводили разные цифры о количестве сербов, евреев и других лиц, убитых усташами на территории НДХ. Александр Лёр заявил, что убито 400 000 сербов, Массенбах - около 700 000. Герман Нойбахер заявил, что утверждения усташей о миллионе убитых сербов являются «хвастливым преувеличением», и полагал, что число «беззащитных убитых жертв составляет три четверти миллиона». Ватикан назвал 350 000 сербов, убитых к концу 1942 года ( Эжен Тиссеран ). [280] Югославия представила 1 700 000 своих военных потерь, рассчитанных математиком Владетой Вучкович в Парижских мирных договорах (1947 г.). [281] Секретный правительственный список 1964 года насчитывал 597 323 жертвы (из которых 346 740 были сербами). [282] В 1980-х годах хорватский экономист Владимир Жерьявич пришел к выводу, что число жертв составило около миллиона. [283] Более того, он утверждал, что число жертв-сербов в Независимом государстве Хорватия составляло от 300 000 до 350 000, причем в Ясеноваце 80 000 жертв всех национальностей. [284] После распада Югославии хорватская сторона начала предлагать существенно меньшие цифры, в то время как сербская сторона поддерживает преувеличенные цифры, продвигаемые в Югославии до 1990-х годов.

- ^ насчитывает Мемориальный музей Холокоста США (по состоянию на 2012 год) в общей сложности 320 000–340 000 этнических сербов, убитых в Хорватии и Боснии, и 45–52 000 убитых в Ясеноваце. [209] Центр Яд Вашем утверждает, что в Хорватии были убиты более 500 000 сербов, 250 000 были изгнаны, а еще 200 000 были вынуждены принять католицизм. [285]

- ^ По данным К. Унгвари, фактическое число депортированных сербов составило 25 000 человек. [286] Рамет цитирует заявление Германии. [287] Сербский православный епископ в Америке Дионисий Миливоевич заявил, что в ходе венгерской оккупации было депортировано 50 000 сербских колонистов и поселенцев и 60 000 убито. [288]

- ^ Единственные официальные югославские данные о жертвах войны в Косово и Метохии относятся к 1964 году и насчитывают 7927 человек, из которых 4029 были сербами, 1460 черногорцами и 2127 албанцами. [289]

Сноски

- ^ Гольдштейн 1999 , с. 158.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Рамет 2006 , с. 114.

- ^ Бейкер 2015 , с. 18.

- ^ Беллами 2013 , с. 96.

- ^ Павлович 2008 , с. 34.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и Йоманс 2012 , с. 18.

- ^ Кристиа 2012 , с. 206.

- ^ Корб 2010a , с. 512.

- ^ Бартулин 2013 , с. 5.

- ^ Туваль 2001 , с. 105.

- ^ Йонассон и Бьёрнсон 1998 , стр. 281, Кармайкл и Магуайр, 2015 г. , с. 151, Томасевич 2001 , с. 347, Мойзес 2011 , с. 54, Каллис 2008 , стр. 101-1. стр. 130–132, Суппан, 2014 г. , стр. 130–132. 1005, Фишер 2007 , стр. 101–111. 207–208, Биделе и Джеффрис 2007 , с. 187, Маккормик, 2008 г.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , стр. 347, 404, Yeomans 2015 , стр. 265–266, Каллис 2008 , стр. 130–132, Фишер 2007 , стр. 207–208, Bideleux & Jeffries 2007 , стр. 187, Маккормик, 2008 г. , Ньюман, 2017 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Фишер 2007 , с. 207.

- ^ Йонассон и Бьорнсон 1998 , стр. 281.

- ^ ЮЖНОСЛАВЕНСКОЕ ПИТАНЬЕ. Prikaz cjelokupnogpitanja (Южнославянский вопрос и мировая война: ясное изложение общей проблемы). Превод: Федор Пучек, Матица Хорватская, Вараждин, 1990 г.

- ^ Кармайкл 2012 , с. 97.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Йоманс 2015 , с. 265.

- ^ Бартулин 2013 , с. 37.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Маккормик 2008 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Кенрик 2006 , с. 92.

- ^ Бартулин 2013 , с. 123.

- ^ Йоманс 2015 , с. 167.

- ^ Каллис 2008 , стр. 130–132.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Ньюман 2017 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Каллис 2008 , с. 130.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д Ньюман 2014 .

- ^ Суппан 2014 , с. 310, 314.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Огнянова 2000 , с. 3.

- ^ Йоманс 2012 , с. 7.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Каллис 2008 , стр. 130–131.

- ^ Бартулин 2013 , с. 124.

- ^ Бартулин 2013 , стр. 56–60.

- ^ Бартулин 2013 , стр. 52–53.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и Рамет 2006 , с. 118.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Суппан 2014 , с. 39, 592.

- ^ Суппан 2014 , с. 591.

- ^ Йоманс 2012 , с. 6.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д Йоманс 2015 , с. 300.

- ^ Суппан 2014 , с. 586.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д Томасевич 2001 , с. 404.

- ^ Йоманс 2015 , с. 150, 300.

- ^ Суппан 2014 , с. 573, 588-590.

- ^ «Усташа » энциклопедия Британская Получено 7 мая.

- ^ Суппан 2014 , с. 590.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Рогель 2004 , с. 8.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Йоманс 2015 , с. 150.

- ^ Моисей 2011 , стр. 52–53.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот п д р Леви 2009 .

- ^ Фишер 2007 , с. 208.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , стр. 402–404.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. 403.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Йоманс 2012 , с. 16.

- ^ Павасович Трошт 2018 .

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. 32.

- ^ Суппан 2014 , с. 592.

- ^ Йоманс 2015 , с. 301.

- ^ Каллис 2008 , стр. 130, Йоманс 2015 , стр. 263, Суппан 2014 , с. 591, Леви 2009 г. , Доменико и Хэнли 2006 г. , с. 435, Адели 2009 , с. 9

- ^ Каллис 2008 , с. 134.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Пейн 2006 .

- ^ Фишер 2007 , с. ?.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. 272.

- ^ Каллис 2008 , с. 239.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. 466.

- ^ «Расшифровка балканской загадки: использование истории для формирования политики» (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 13 ноября 2005 года . Проверено 3 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Моисей 2011 , с. 54.

- ^ Джонс, Адам и Николас А. Робинс. (2009), Геноциды угнетенных: геноцид подчиненных в теории и практике , с. 106, Издательство Университета Индианы; ISBN 978-0-253-22077-6

- ^ Джейкобс 2009 , с. 158-159.

- ^ Адриано и Чинголани 2018 , с. 190.

- ^ Шеперд 2012 , с. 78.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Израильский 2013 , с. 45.

- ^ Гольдштейн 1999 , с. 134.

- ^ Вайс-Вендт 2010 , с. 148.

- ^ Вайс-Вендт 2010 , стр. 148–149, 157.

- ^ Суппан 2014 , стр. 32, 1065.

- ^ Гольдштейн 1999 , с. 133.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. 425.

- ^ Огнянова 2000 , с. 22.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Йоманс 2012 , с. 17.

- ^ Фишер 2007 , стр. 207–208, 210, 226.

- ^ Фишер 2007 , с. 212.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Файер 2000 , с. 31.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Барбье 2017 , с. 169.

- ^ Блоксхэм и Герварт 2011 , с. 111.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Маккормик 2014 , с. 72.

- ^ Йоманс 2015 , с. 132.

- ^ Израиль, 2013 , с. 51.

- ^ Рамет 2006 , с. 312.

- ^ Леви 2011 , с. 61.

- ^ Фишер 2007 , с. 228.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Байфорд 2020 , с. 10.

- ^ Йоманс 2012 , с. 2.

- ^ Леви 2011 , с. 69.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. 726.

- ^ Йоманс 2015 , с. 21, Павлович 2008 , с. 34

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Йоманс 2015 , с. 3, Павлович 2008 , с. 34

- ^ Париж 1961 , с. 132.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Леви 2011 , с. 70.

- ^ Леви 2011 , стр. 70–71.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Леви 2011 , с. 71.

- ^ Вайс Вендт 2010 , с. 147.

- ^ Литучий 2006 , с. 117.

- ^ Булайич 2002 , стр. 231.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Леви 2011 , с. 72.

- ^ Шиндли и Макара 2005 , с. 149.

- ^ Джейкобс 2009 , с. 160.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Байфорд 2014 .

- ^ Литучий 2006 , с. 220.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Экстрадиция нацистских преступников: Райана, Артуковича и Демьянюка» . Центр Симона Визенталя . Проверено 10 мая 2020 г.